↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Deep neural network (DNN) training dynamics are complex and varied, hindering our understanding of DNN generalization and efficiency. Current methods for comparing DNN training dynamics rely on coarse-grained metrics like loss, which are insufficient to capture the nuances of DNN behavior. Identifying equivalent dynamics across different architectures is challenging due to the lack of precise mathematical definitions and computational tools.

This research introduces a novel framework that addresses these limitations by utilizing Koopman operator theory. This framework enables the identification of topological conjugacies between DNN training dynamics, offering a precise definition of dynamical equivalence. The researchers validated this framework by correctly identifying known equivalences, and they used it to uncover both conjugate and non-conjugate dynamics across various architectures, including fully connected networks, convolutional networks, and transformers. The findings highlight the potential of this framework to improve our understanding of DNN training and to inspire the development of more efficient and robust training algorithms.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in deep learning and dynamical systems. It offers a novel framework for comparing the training dynamics of different neural networks, a long-standing challenge. This opens new avenues for understanding generalization, improving training efficiency, and designing more robust architectures. The Koopman operator theory-based approach is flexible and applicable to various neural network architectures. This work directly addresses a critical gap in the field by moving beyond qualitative observations to provide quantitative measures of equivalence.

Visual Insights#

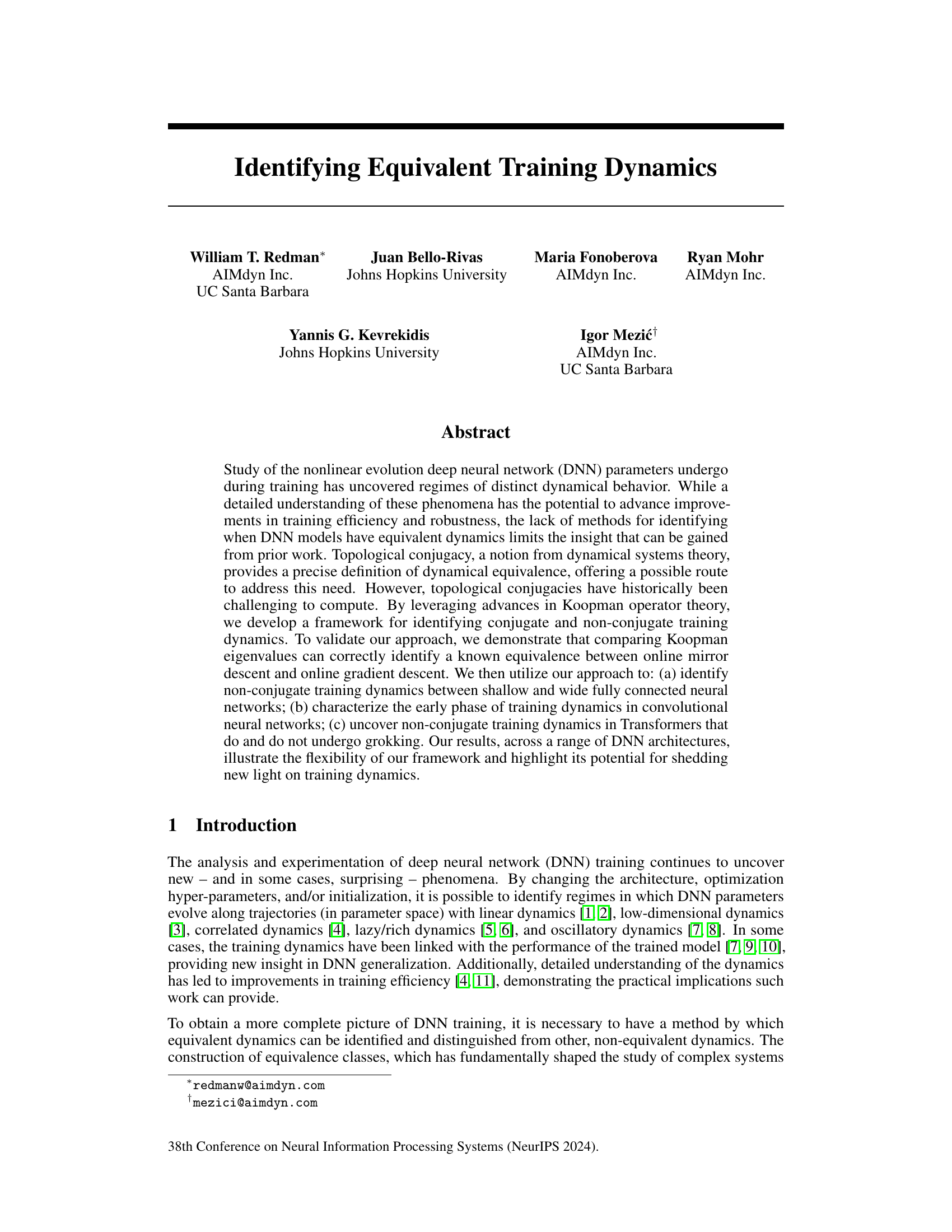

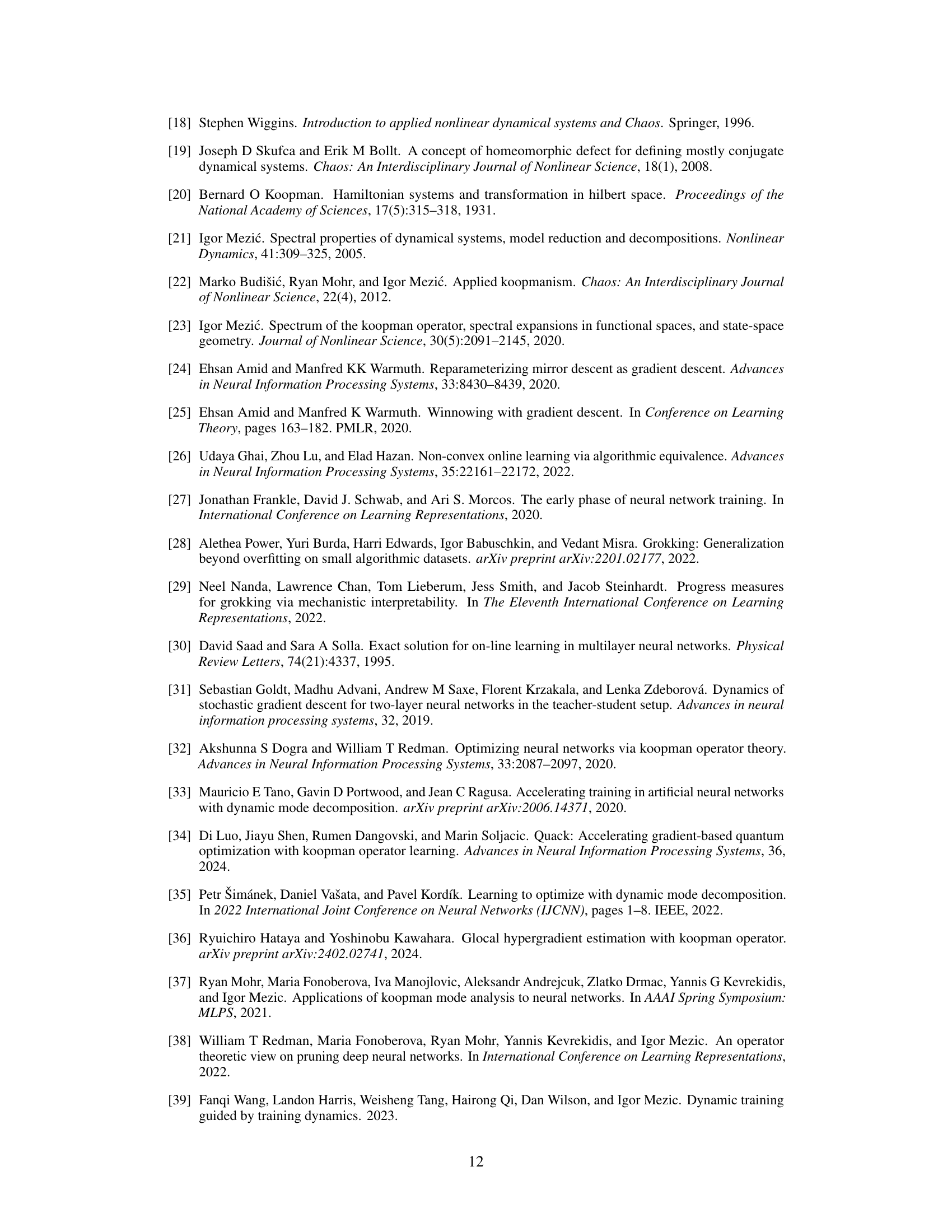

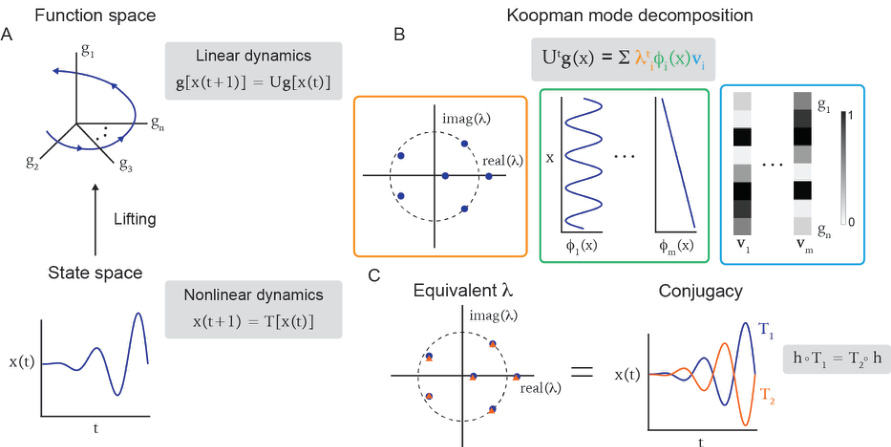

This figure schematically illustrates the Koopman operator theory and its application to identifying conjugate dynamical systems. Panel A shows how nonlinear dynamics in a finite-dimensional state space can be lifted to a linear representation in an infinite-dimensional function space using the Koopman operator. Panel B illustrates the Koopman mode decomposition, which breaks down the lifted dynamics into a sum of Koopman modes, each characterized by its eigenvalue, eigenfunction, and mode. Finally, panel C demonstrates that two dynamical systems are topologically conjugate if they have the same Koopman eigenvalues.

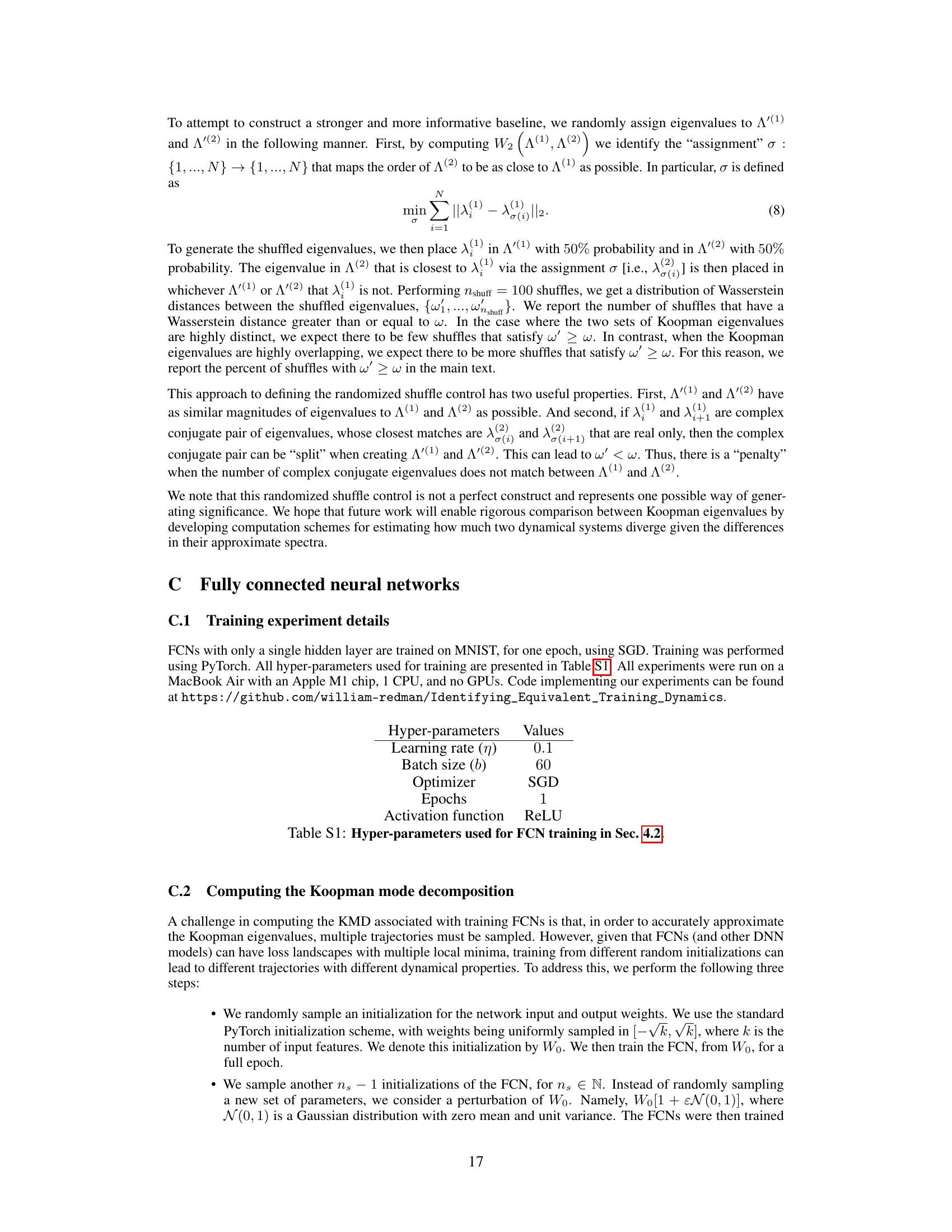

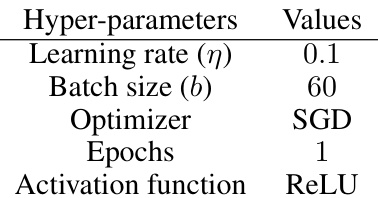

This table presents the hyperparameters used for training fully connected neural networks (FCNs) in section 4.2 of the paper. It shows the values used for the learning rate, batch size, optimizer, number of epochs, and activation function.

In-depth insights#

Equiv Dynamics ID#

Identifying equivalent training dynamics in deep neural networks (DNNs) is crucial for understanding their behavior and improving training efficiency. Topological conjugacy, a concept from dynamical systems theory, provides a rigorous definition of dynamical equivalence, allowing researchers to identify when different DNN models exhibit similar training trajectories despite varying architectures or hyperparameters. This method goes beyond simple loss comparisons, which can be misleading due to factors like initialization or architectural differences. The challenge lies in computing topological conjugacies, which are traditionally difficult for complex nonlinear systems like DNNs. The authors leverage advances in Koopman operator theory to develop a framework for identifying such equivalences. This is a significant methodological advancement because it enables the identification of dynamically equivalent DNNs from data, without requiring explicit knowledge of the governing equations, which are generally unknown for modern DNN architectures. The framework’s utility is demonstrated through validation against known equivalences and identification of novel conjugate and non-conjugate training dynamics across several architectures and training regimes.

Koopman Spectrum#

The Koopman spectrum, derived from Koopman operator theory, offers a powerful lens for analyzing dynamical systems. It represents the eigenvalues of the Koopman operator, which governs the evolution of observables over time. Crucially, the Koopman spectrum is invariant to coordinate transformations, making it an ideal tool for comparing the dynamics of different systems, even when their underlying equations differ. In the context of deep neural network (DNN) training, where the parameter space is high-dimensional and non-linear, the Koopman spectrum provides a robust and computationally efficient way to quantify and compare training dynamics. By analyzing the distribution and properties of the eigenvalues, one can reveal rich information about the nature of the training process. For instance, similar Koopman spectra can indicate that DNNs exhibit equivalent training dynamics, suggesting that differences in architecture or hyperparameters may not necessarily lead to significantly different learning behaviors. Conversely, distinct Koopman spectra highlight fundamental differences in the training dynamics, revealing crucial insights into the impact of architectural or hyperparameter choices on DNN learning.

DNN Training#

Deep neural network (DNN) training is a complex process involving the optimization of a vast number of parameters to minimize a loss function. The paper explores the nonlinear dynamics of this process, revealing regimes of distinct dynamical behavior and demonstrating how topological conjugacy, a concept from dynamical systems theory, can be used to identify equivalent training dynamics. The authors leverage advances in Koopman operator theory to develop a framework capable of distinguishing between conjugate and non-conjugate dynamics across various architectures, including fully connected networks, convolutional neural networks, and transformers. Key findings highlight the impact of network width on training dynamics, reveal dynamical transitions during the early phase of convolutional network training, and uncover distinct dynamics in transformers exhibiting grokking versus those that do not. This work provides a novel framework to understand training, allowing for more precise comparisons and the potential for optimization improvements.

Grokking Dynamics#

The phenomenon of “grokking” in deep learning, where models suddenly achieve high accuracy after a prolonged period of seemingly poor performance, presents a fascinating area of study. Analyzing “grokking dynamics” requires investigating the underlying changes in the model’s parameter space and activation patterns. Koopman operator theory offers a powerful tool for this analysis, as it provides a linear representation of nonlinear dynamical systems. By applying KMD to the model’s weight trajectories during training, we can identify the critical transitions associated with the onset of grokking. This might reveal characteristic patterns in Koopman eigenvalues and eigenfunctions, signifying the shift from a less successful, potentially chaotic, regime to a highly performant one. Comparing the dynamics of models that exhibit grokking with those that do not allows for distinguishing crucial features associated with successful generalization. Furthermore, the analysis can uncover the role of factors like network architecture, optimization algorithm, and data characteristics in shaping grokking dynamics. Ultimately, a deeper understanding of these dynamics could lead to improved training strategies that reliably induce such rapid leaps in performance and facilitate a more robust and efficient training process.

Future Works#

Future research directions stemming from this work on identifying equivalent training dynamics in Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) are rich and multifaceted. Extending the Koopman operator framework to handle chaotic dynamics is crucial, as this would unlock its application to a broader range of DNN training scenarios. Investigating the relationship between Koopman spectrum characteristics and generalization ability would yield valuable insights for model design and optimization. Applying this framework to more complex architectures like transformers and recurrent neural networks to fully explore the range of its applicability and to further investigate the dynamical transitions during training is needed. Developing a more robust metric for comparing Koopman spectra that accounts for noise and finite sampling effects would enhance the reliability of topological conjugacy identification. Finally, integrating this dynamical systems perspective with existing DNN theoretical frameworks to potentially refine existing theories of generalization and optimization algorithms may lead to a more complete understanding of DNN training.

More visual insights#

More on figures

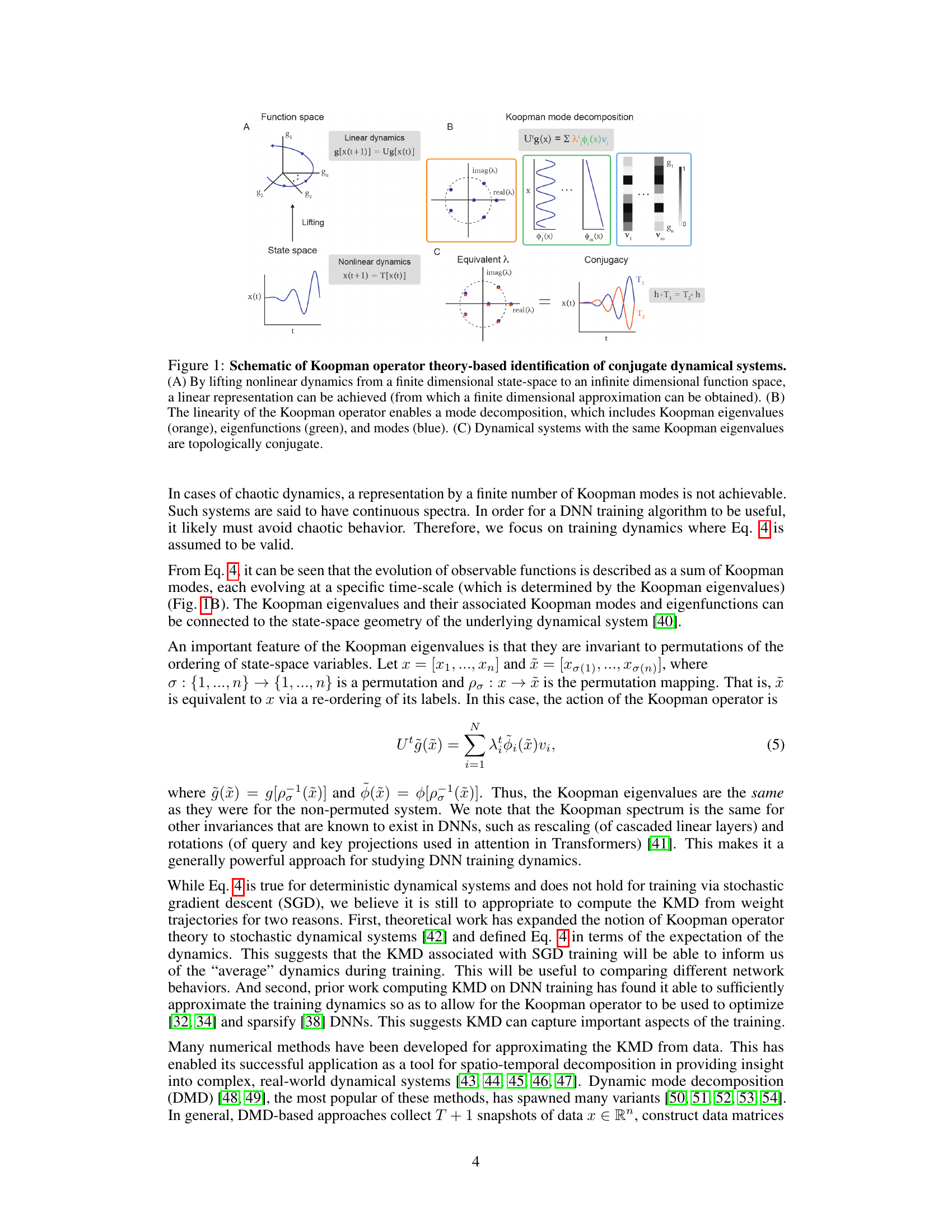

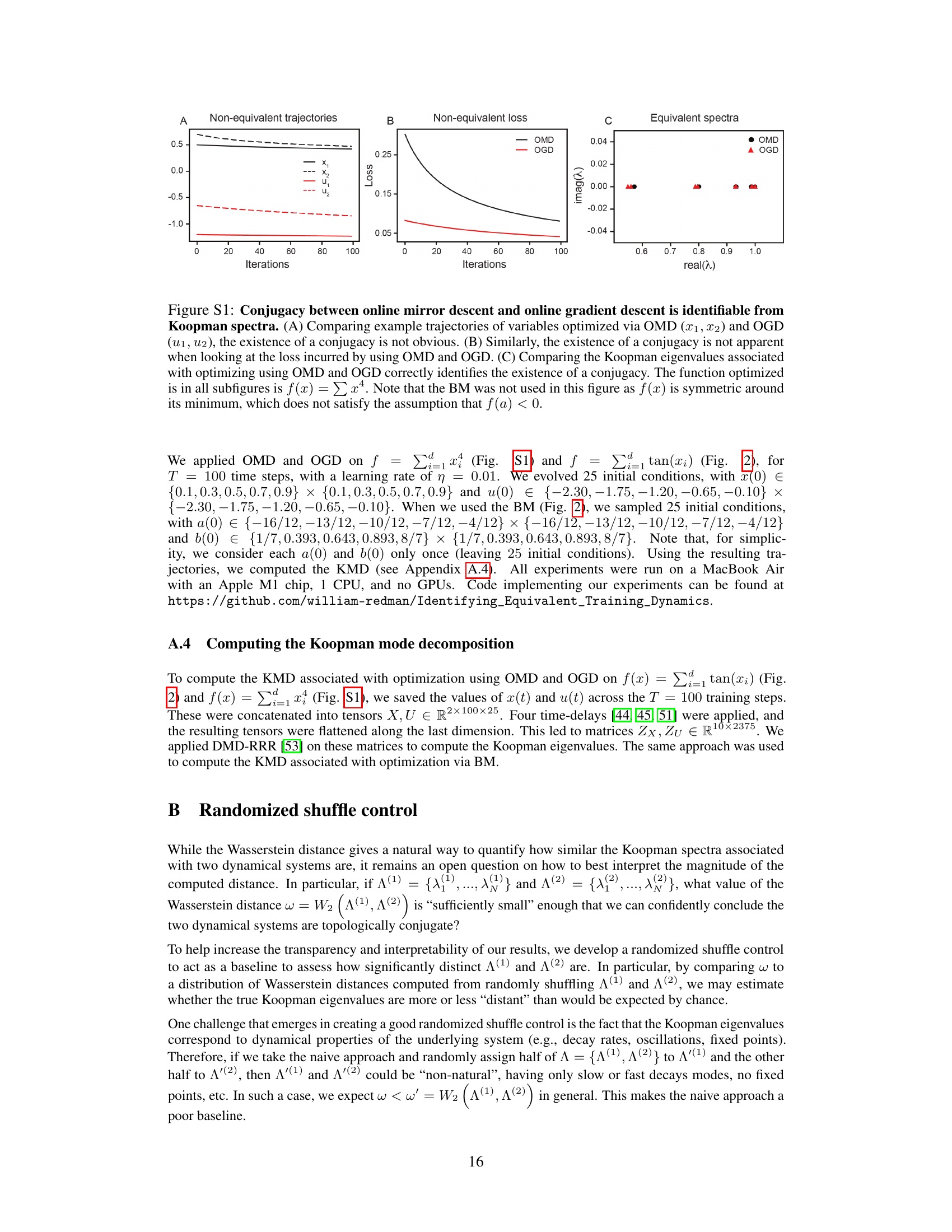

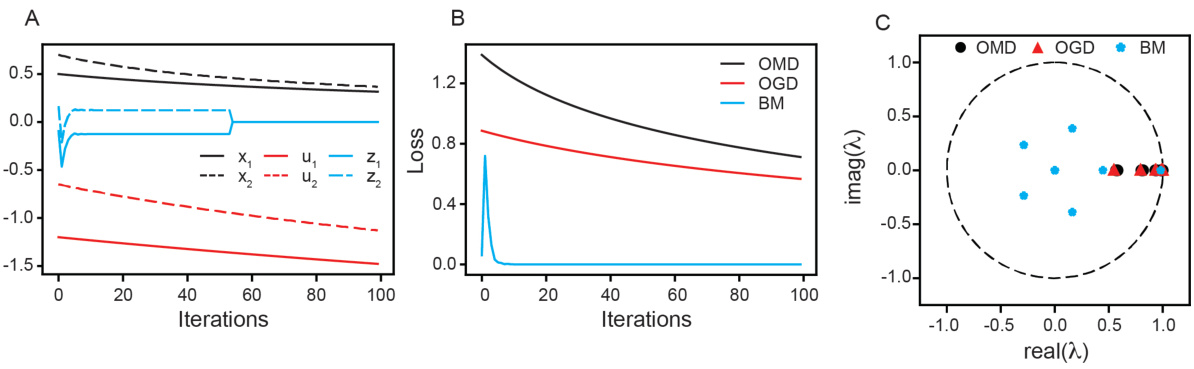

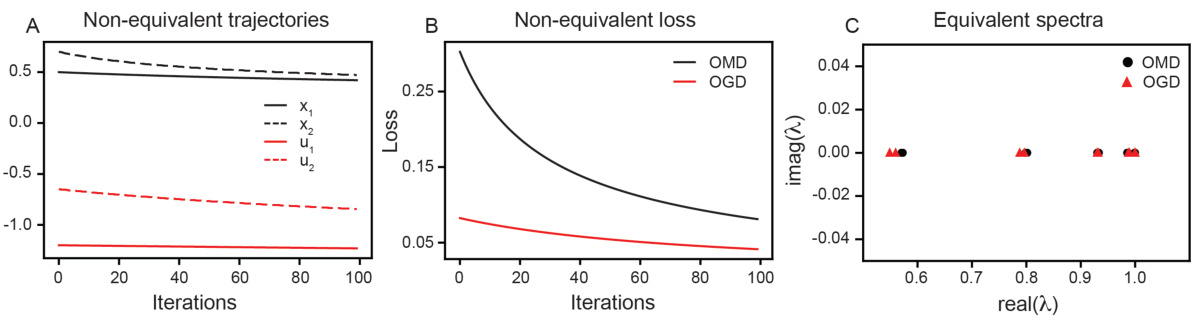

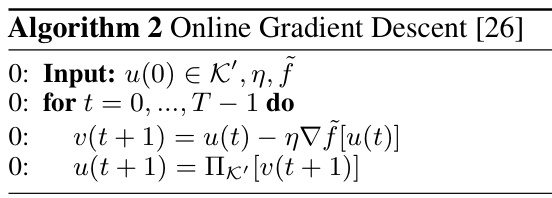

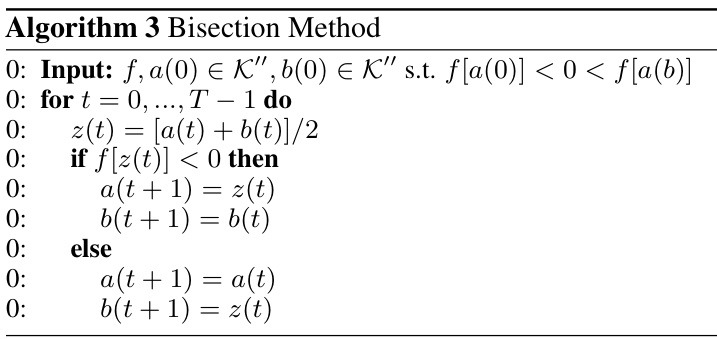

This figure demonstrates that the Koopman spectra can identify the conjugacy between Online Mirror Descent (OMD) and Online Gradient Descent (OGD) which is not obvious from the trajectories or loss functions. Panel A shows example trajectories of the variables optimized by OMD, OGD, and Bisection Method (BM). Panel B shows loss curves for each method. Panel C shows the Koopman eigenvalues associated with each method; OMD and OGD have very similar eigenvalues while the BM eigenvalues are clearly distinct.

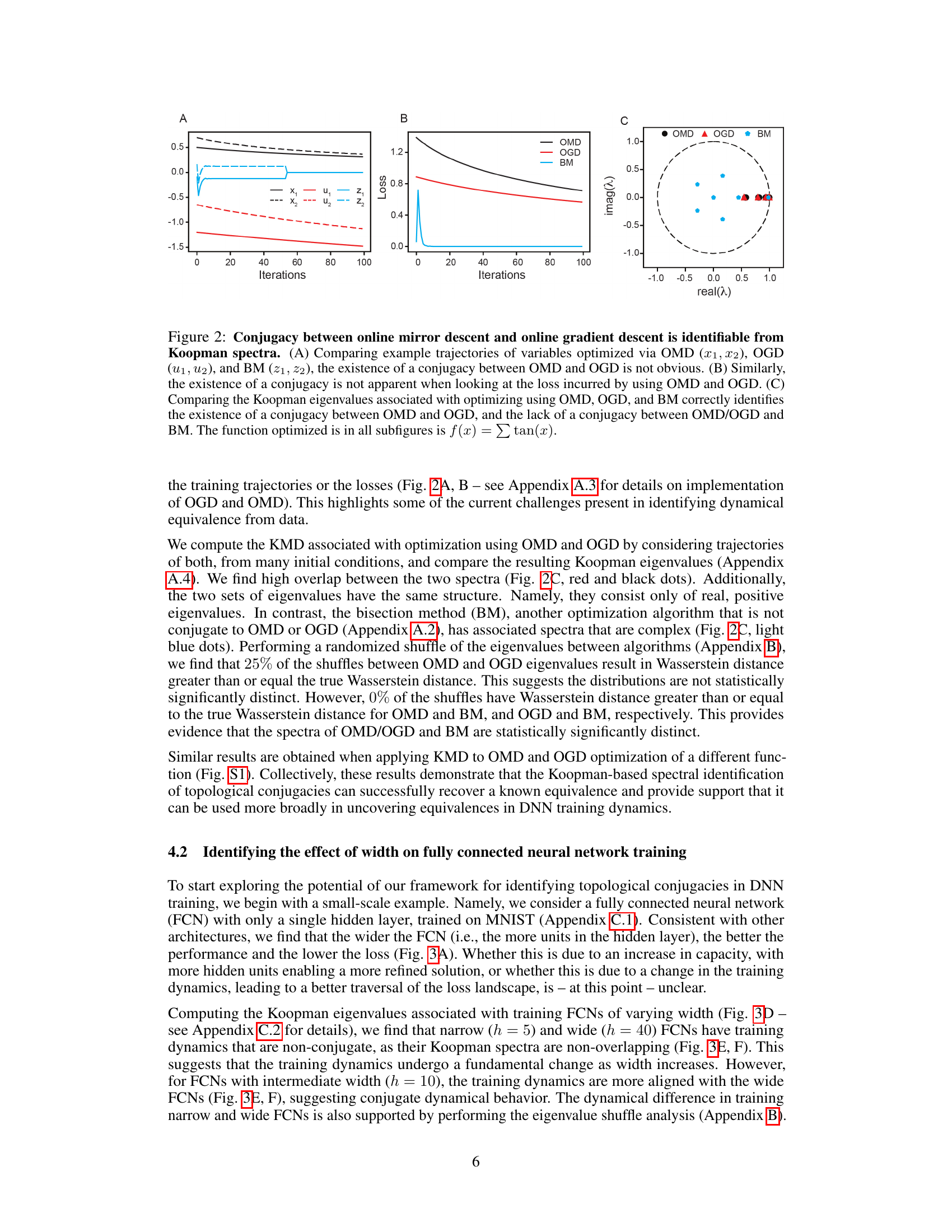

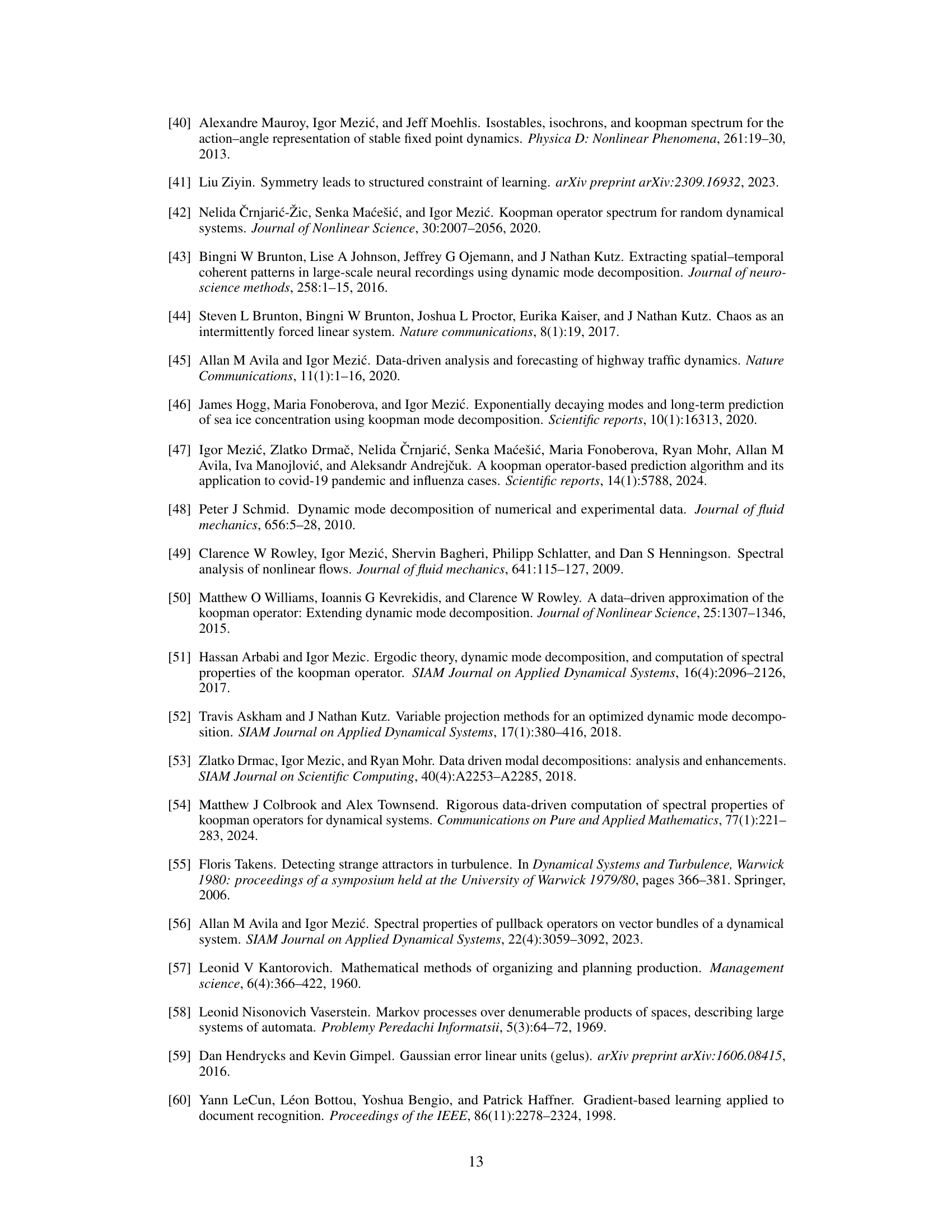

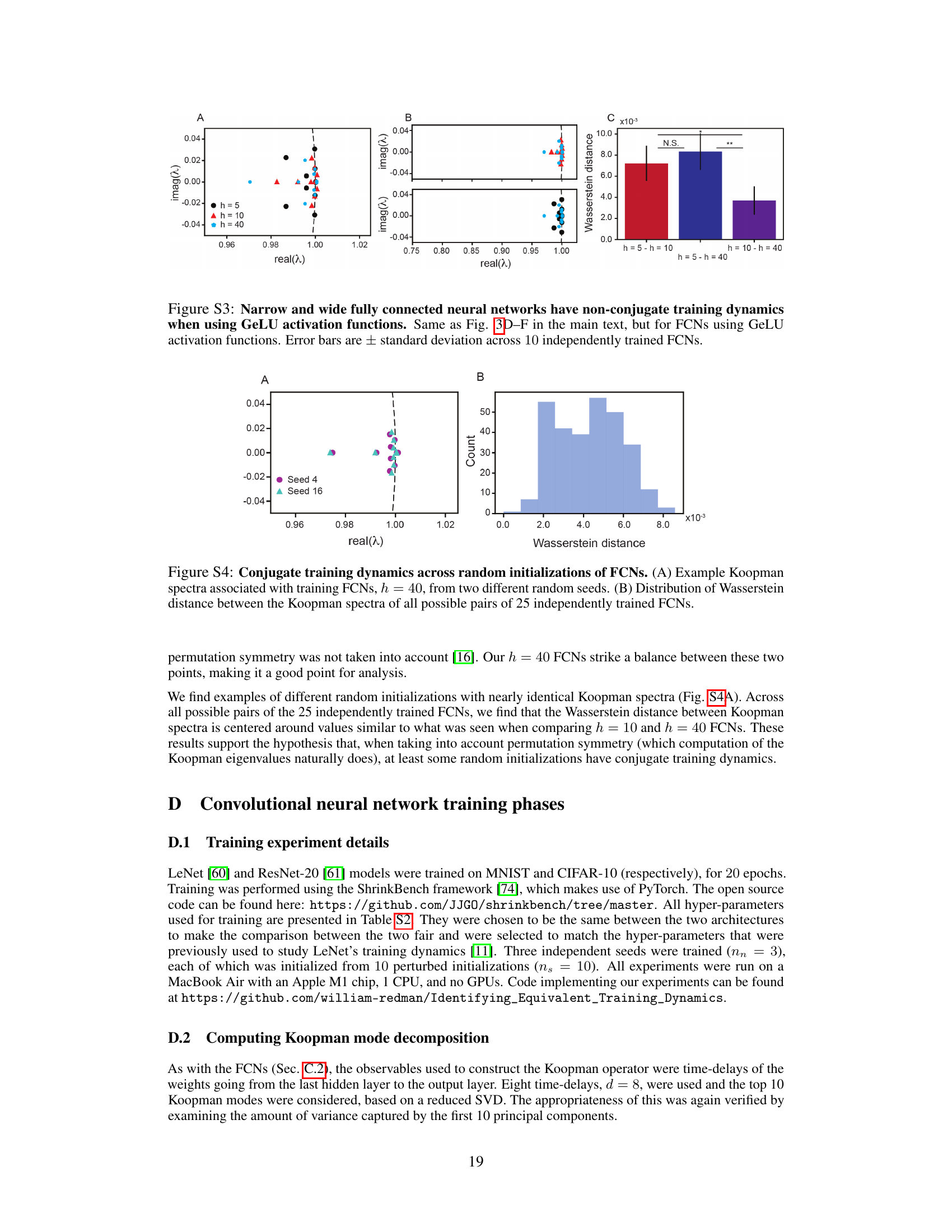

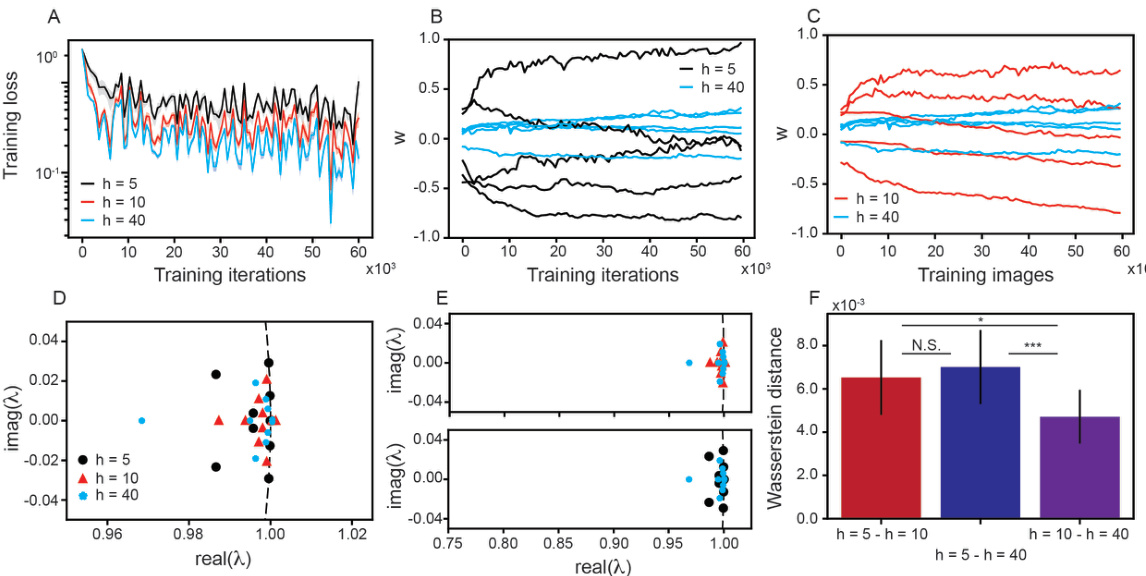

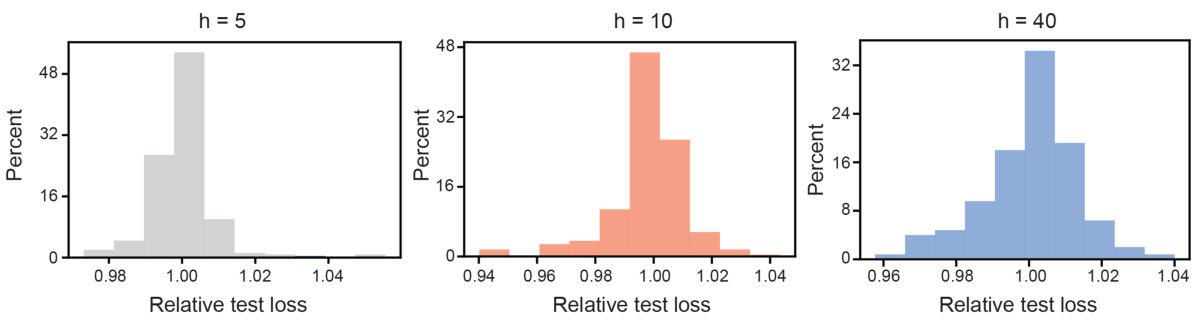

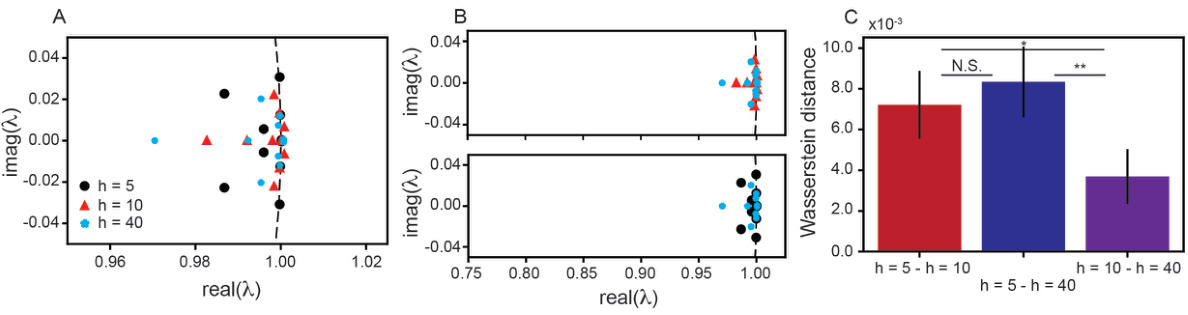

This figure shows the results of comparing the training dynamics of narrow, intermediate, and wide fully connected neural networks (FCNs). It demonstrates that narrow and wide networks exhibit non-conjugate training dynamics, meaning their dynamics are not equivalent, while intermediate-width networks show more similarity to the wide networks. This is assessed by analyzing training loss, weight trajectories, Koopman eigenvalues (which indicate the timescales of the system), and the Wasserstein distance between the Koopman eigenvalues.

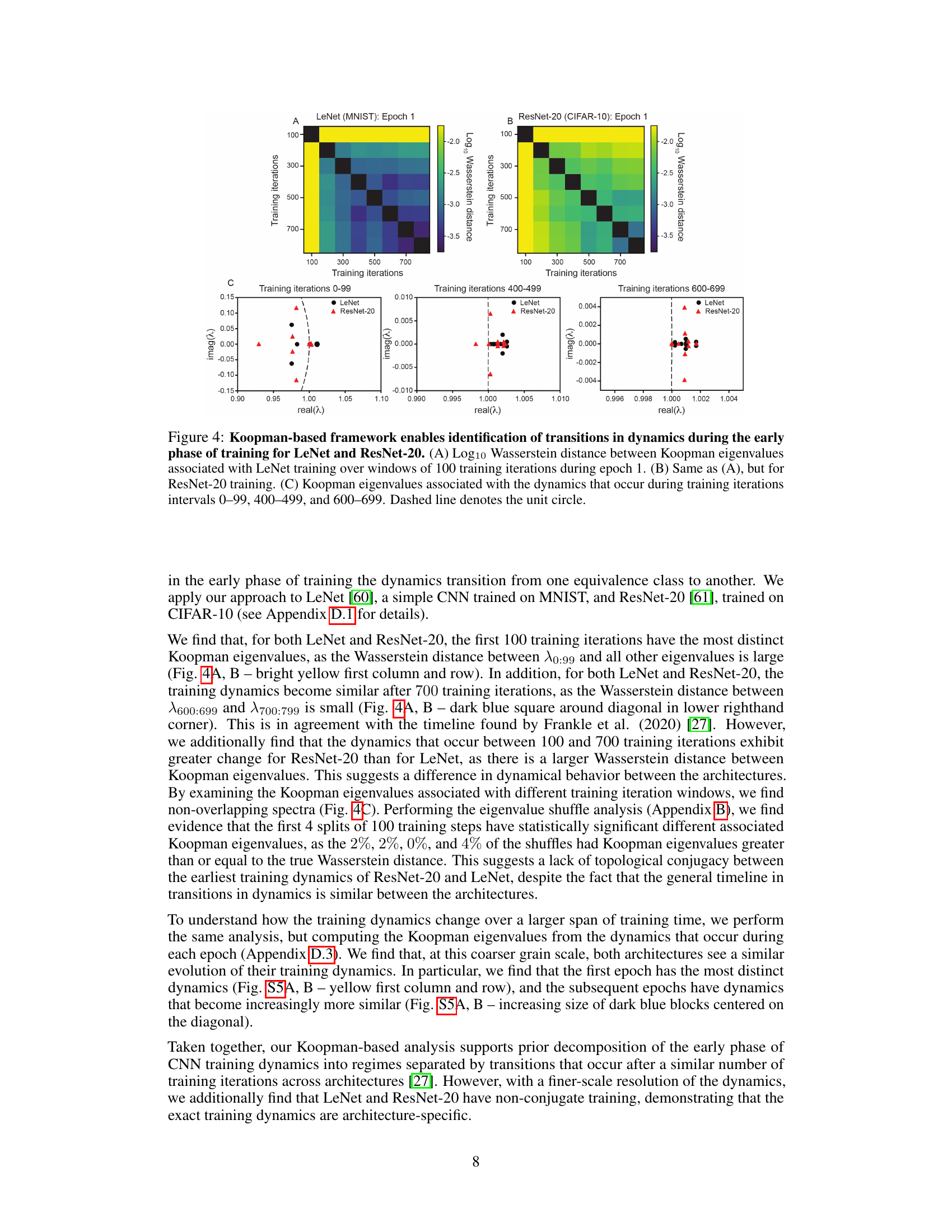

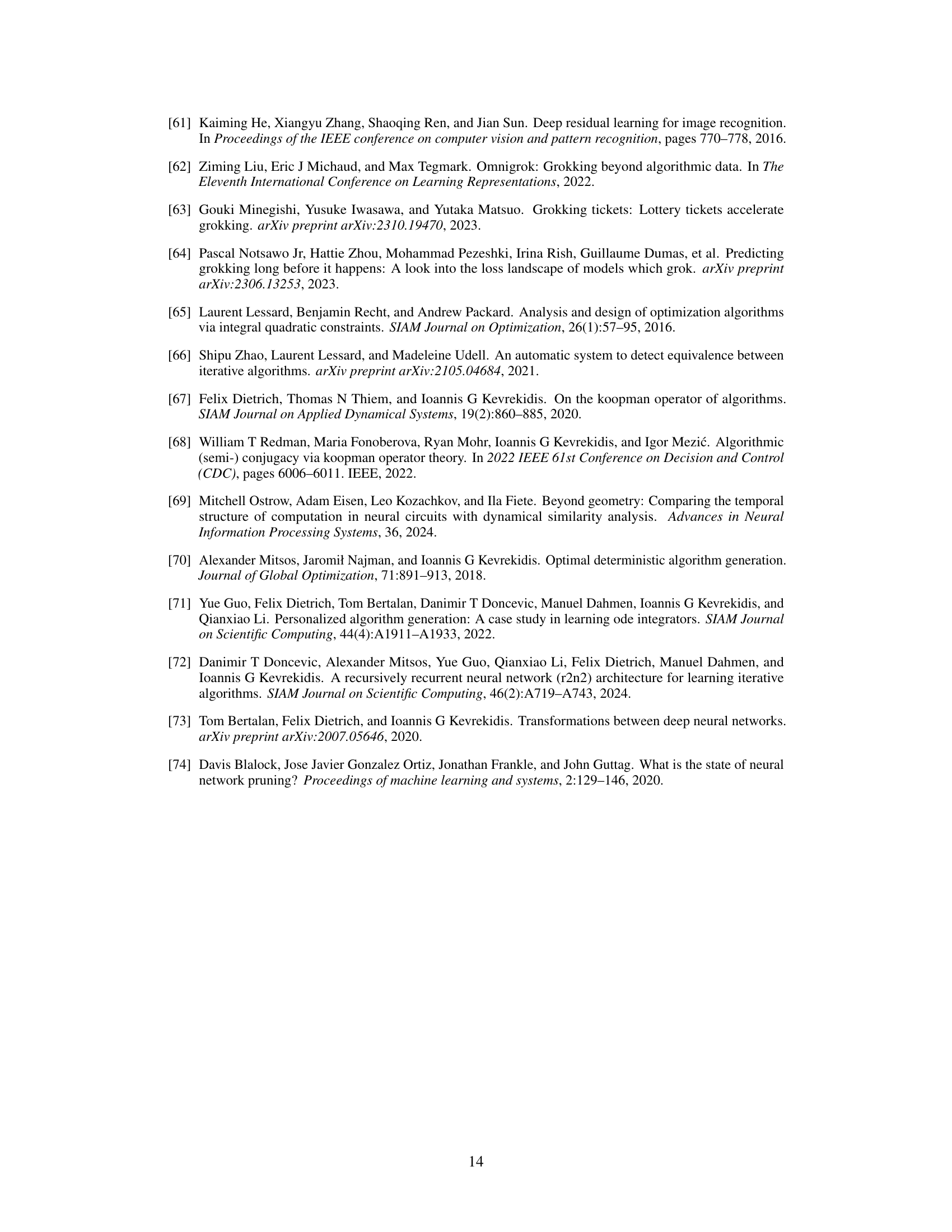

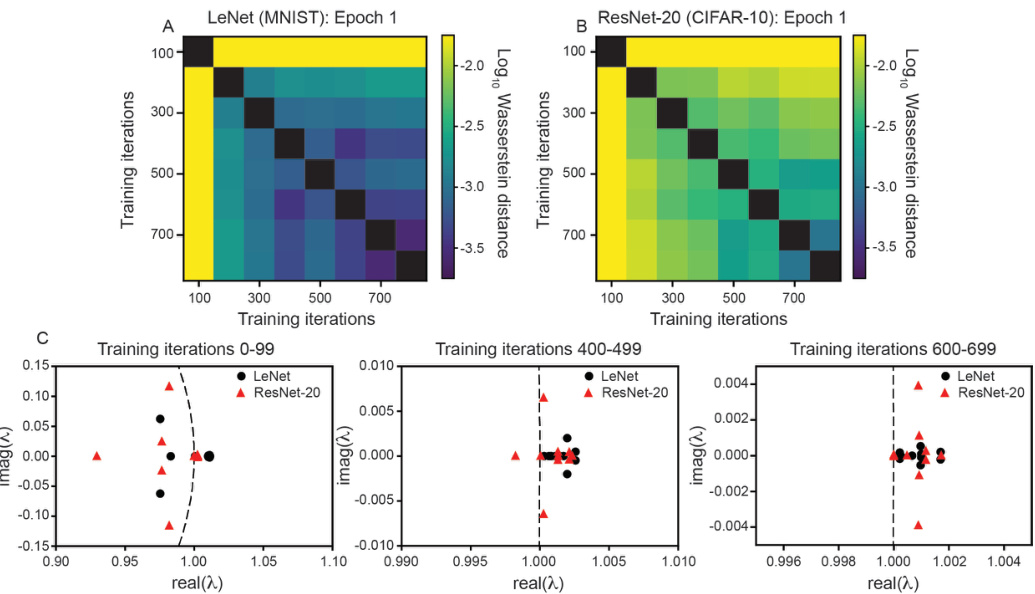

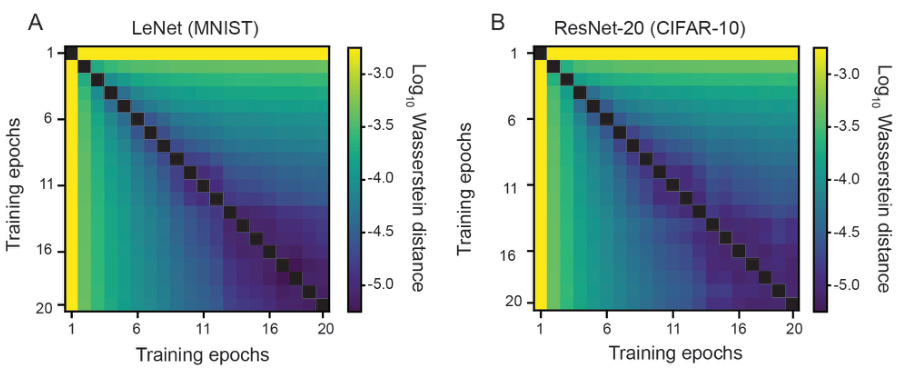

This figure demonstrates the application of the Koopman operator framework to analyze the early training dynamics of two different Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): LeNet (trained on MNIST) and ResNet-20 (trained on CIFAR-10). The figure shows how the Wasserstein distance between Koopman eigenvalues changes over the course of training. The results suggest that CNN training dynamics undergo transitions, with similar patterns observed for both LeNet and ResNet-20, although the specific dynamics are architecture-specific.

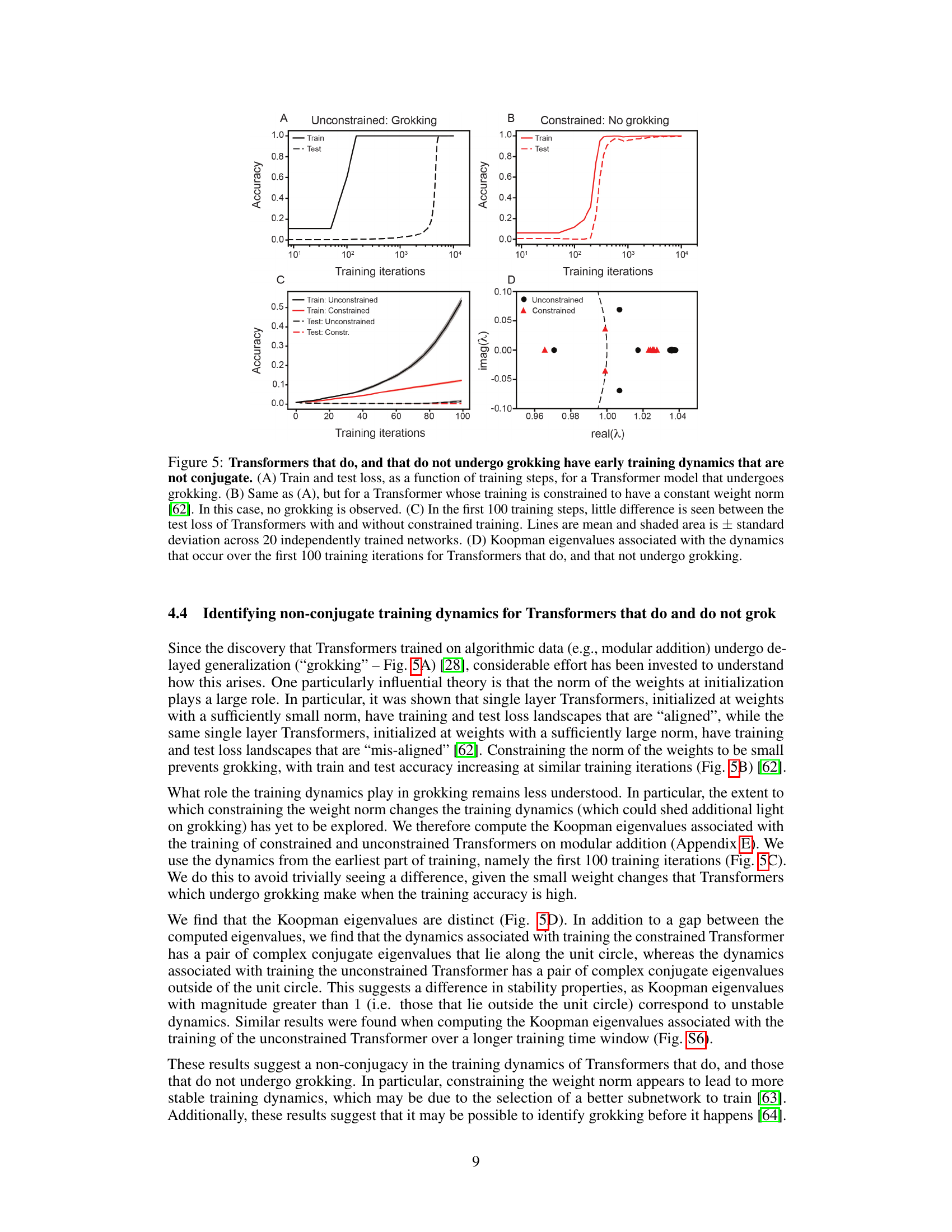

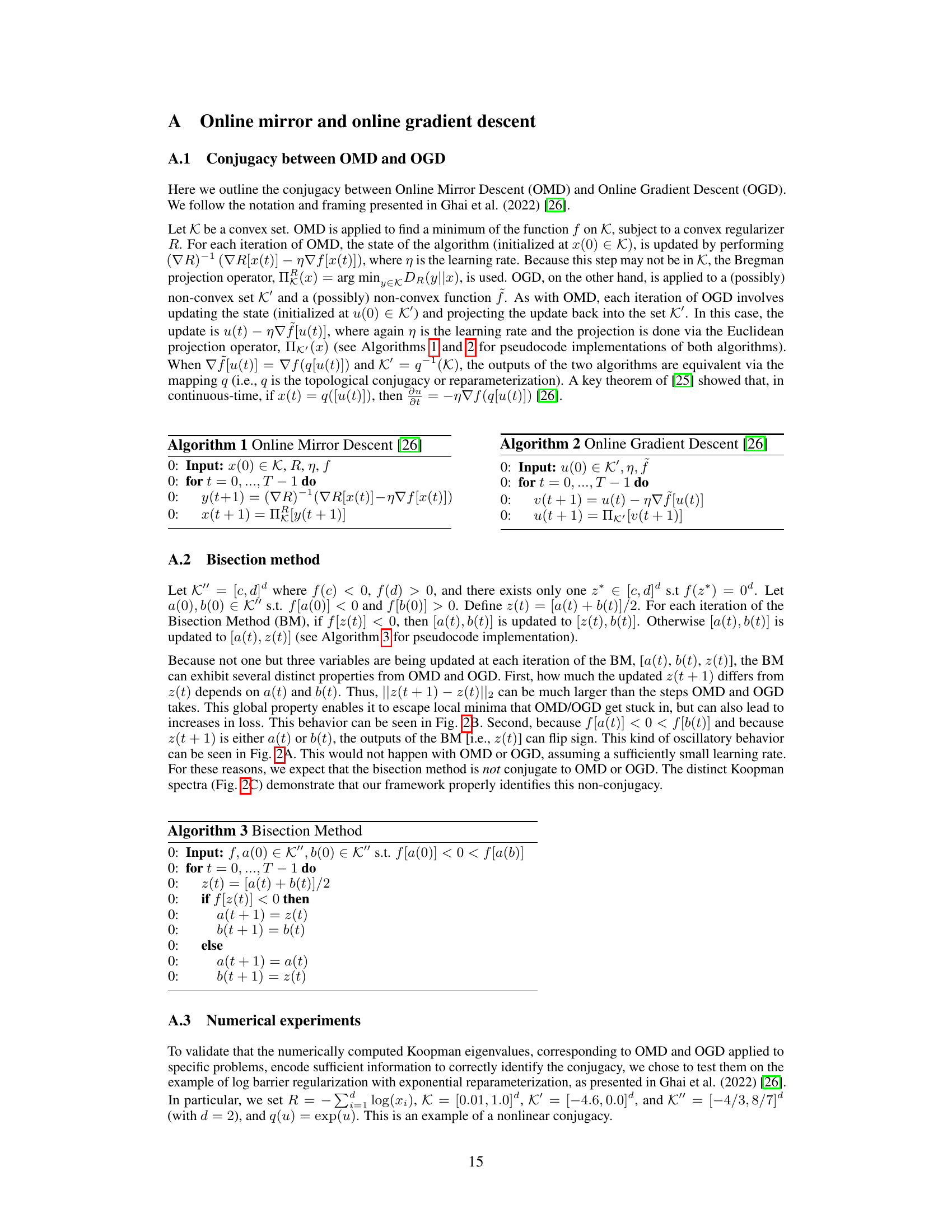

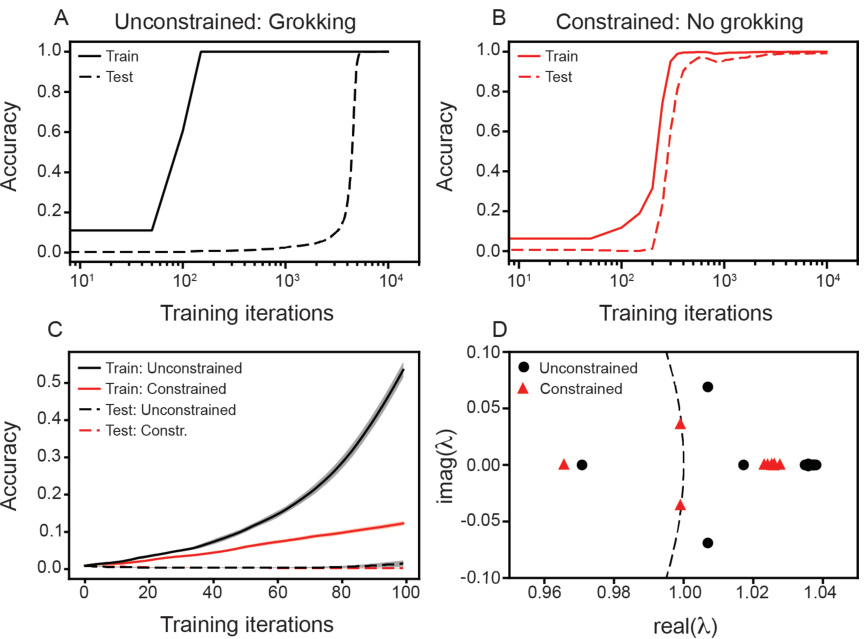

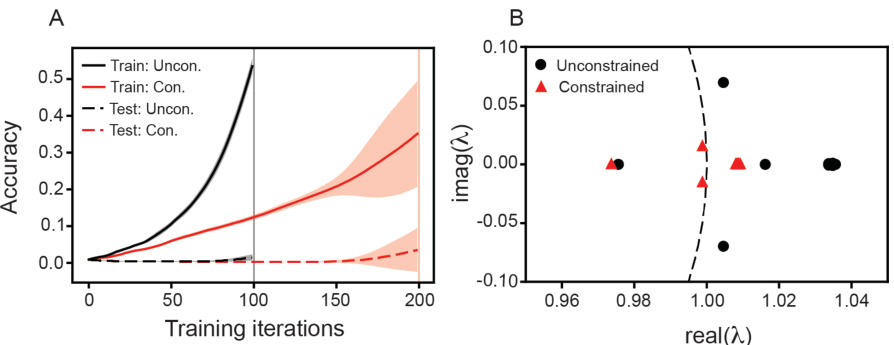

This figure shows the comparison of training dynamics between transformers with and without grokking. The top panels show the training and testing accuracy curves for both models, where the constrained model (no grokking) shows a steady increase in accuracy, while the unconstrained model (grokking) exhibits a sharp increase in accuracy after a certain number of iterations. The bottom left panel shows the train and test accuracy for the first 100 training iterations of both models, revealing subtle differences in the learning behavior in early training. The bottom right panel presents a comparison of Koopman eigenvalues, highlighting the distinct spectral properties that indicate non-conjugate training dynamics between the two models.

This figure demonstrates that the topological conjugacy between Online Mirror Descent (OMD) and Online Gradient Descent (OGD) can be identified using Koopman spectra, despite not being obvious from comparing trajectories or loss alone. The non-conjugacy between OMD/OGD and the Bisection Method (BM) is also shown. The figure uses the function f(x) = tan(x) for all subfigures.

This figure demonstrates that narrow and wide fully connected neural networks exhibit different training dynamics, which are non-conjugate. The analysis uses Koopman eigenvalues to compare the dynamics across varying network widths (h=5, 10, 40). The figure shows training loss curves, example weight trajectories, Koopman eigenvalue plots, and Wasserstein distances between eigenvalues, highlighting the non-conjugate nature of the training dynamics for narrow vs. wide networks.

This figure shows that narrow and wide fully connected neural networks (FCNs) exhibit non-conjugate training dynamics. The training loss, weight trajectories, Koopman eigenvalues, and Wasserstein distances between Koopman eigenvalues are compared across FCNs with different widths (h = 5, 10, and 40). The results demonstrate that the training dynamics change fundamentally as the width increases, highlighting a non-conjugate relationship between narrow and wide FCNs.

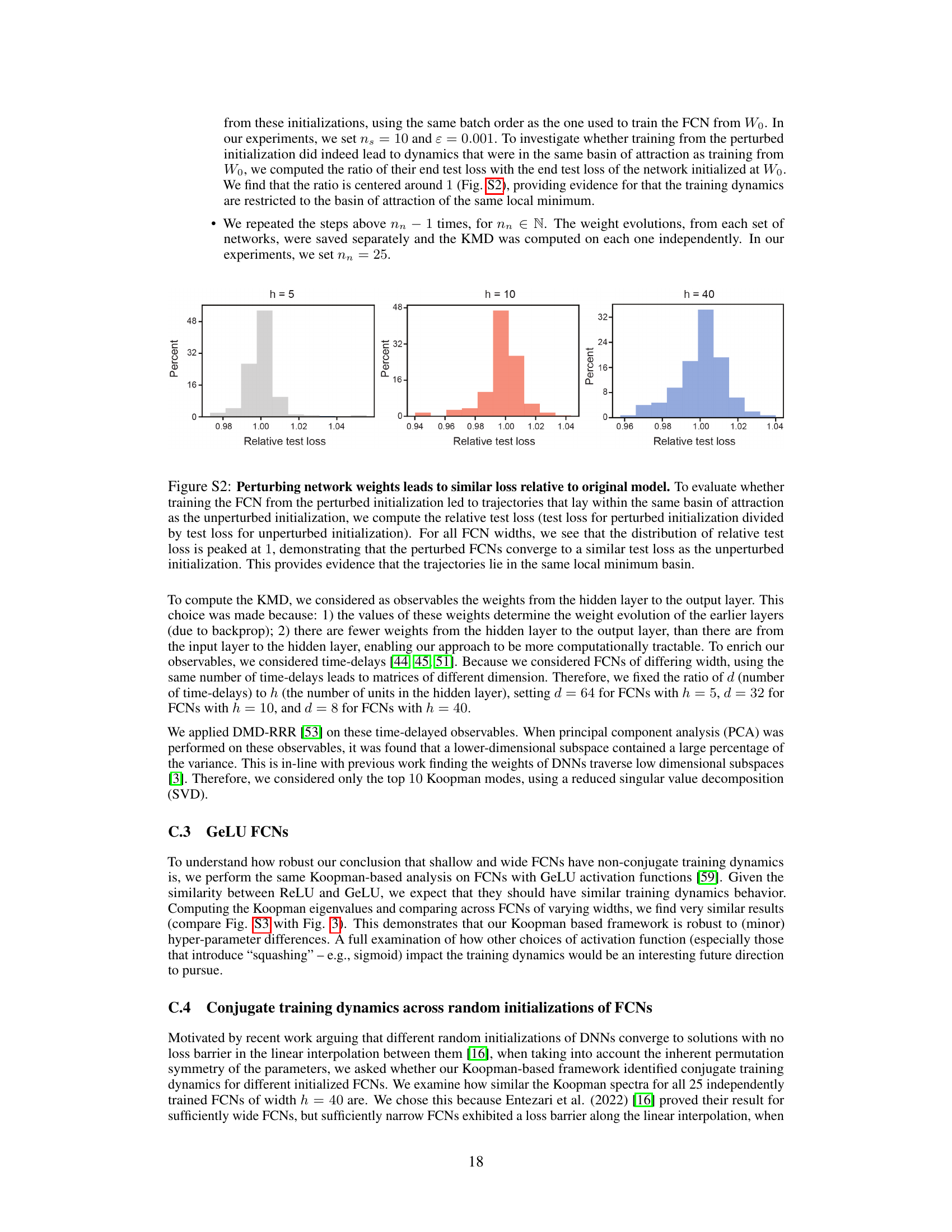

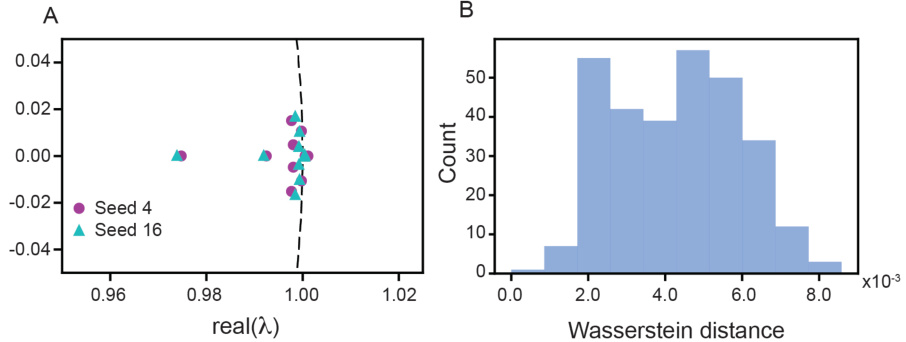

This figure shows the results of an experiment designed to test whether the training dynamics of fully connected neural networks (FCNs) are conjugate across different random initializations. Panel A displays example Koopman spectra for two different random initializations of an FCN with 40 hidden units. Panel B shows a histogram of the Wasserstein distances between all pairs of Koopman spectra from 25 independently trained FCNs. The results suggest that the training dynamics are conjugate across different random initializations, at least for sufficiently wide FCNs.

This figure shows the log10 Wasserstein distance between Koopman eigenvalues associated with training LeNet and ResNet-20 across individual epochs. It extends Figure 4 by looking at the dynamics over larger time windows (entire epochs) rather than smaller intervals, offering a coarser-grained perspective on dynamical transitions during training. The heatmaps visualize the distance between the Koopman eigenvalues of different epochs, revealing similarities and differences in the dynamics over time for both architectures.

This figure demonstrates that the early training dynamics of Transformers that do and do not undergo grokking are non-conjugate. Panel A shows the training and testing loss curves for a Transformer that exhibits grokking (sudden improvement in test accuracy after a period of seemingly poor generalization), and panel B shows the same for a Transformer with a constrained weight norm (preventing grokking). Panel C compares the test loss curves for both types of Transformers in the first 100 training steps, showing little difference. Finally, Panel D displays the Koopman eigenvalues for both types of Transformers, which show distinct non-overlapping spectra, supporting the conclusion of non-conjugate dynamics.

More on tables

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training fully connected neural networks (FCNs) in Section 4.2 of the paper. It shows the values used for the learning rate, batch size, optimizer, number of epochs, and activation function.

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training fully connected neural networks (FCNs) in Section 4.2 of the paper. It includes the learning rate, batch size, optimizer used (SGD), number of epochs, and activation function (ReLU). These settings are crucial for reproducing the results of the experiments.

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training fully connected neural networks (FCNs) in Section 4.2 of the paper. It shows the values used for the learning rate, batch size, optimizer (SGD), number of epochs, and activation function (ReLU).

Full paper#