↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) is a crucial technique in aligning AI with human values, but existing methods for aggregating human preferences to construct a reward function have significant limitations. These methods often rely on maximum likelihood estimation of random utility models such as the Bradley-Terry-Luce model, which fail to satisfy fundamental axioms from social choice theory, such as Pareto optimality and pairwise majority consistency. This lack of axiomatic guarantees raises serious concerns about the fairness, efficiency, and overall reliability of AI systems trained using RLHF.

This research introduces a novel approach called “linear social choice” to address the challenges highlighted above. By leveraging the linear structure inherent in reward function learning, it develops novel aggregation methods that satisfy key social choice axioms. These methods provide a more rigorous and principled way of learning reward functions, offering stronger guarantees for the fairness, efficiency, and alignment of AI systems with human values. The results challenge prevailing RLHF practices and suggest a new paradigm for ensuring ethical and robust AI development.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for AI researchers as it bridges the gap between AI alignment and social choice theory. By applying well-established axiomatic standards from social choice theory to evaluate reward function learning methods in Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), it reveals critical flaws in current practices and proposes novel, axiomatically sound alternatives. This work significantly impacts the reliability and ethical implications of RLHF, opening new research avenues and informing the design of fairer, more robust AI systems. Its rigorous approach to evaluating preference aggregation methods in RLHF enhances the trustworthiness and societal benefit of AI alignment methods.

Visual Insights#

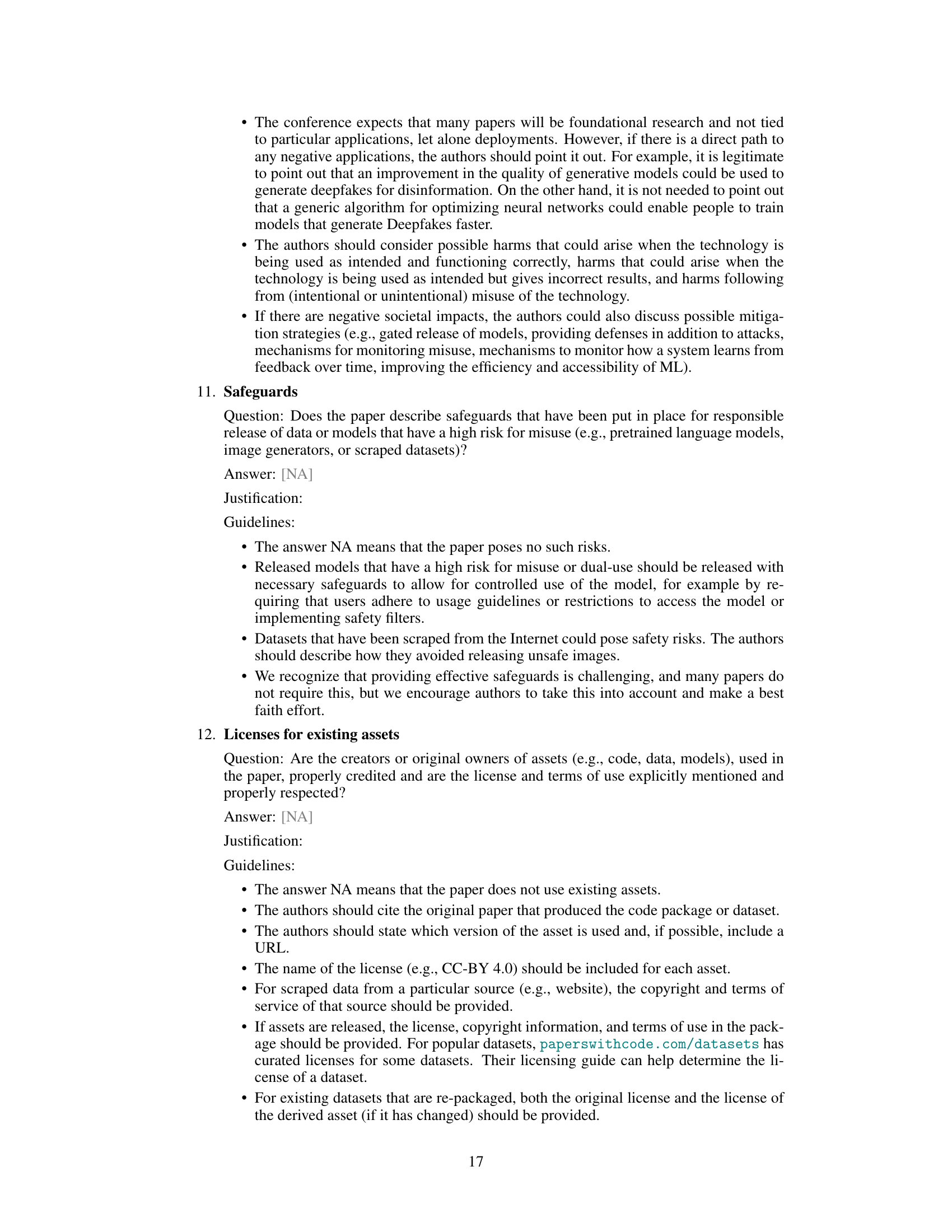

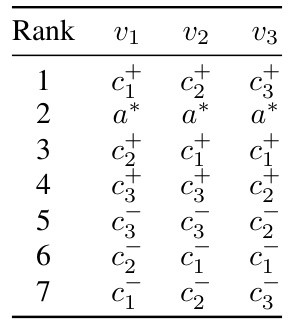

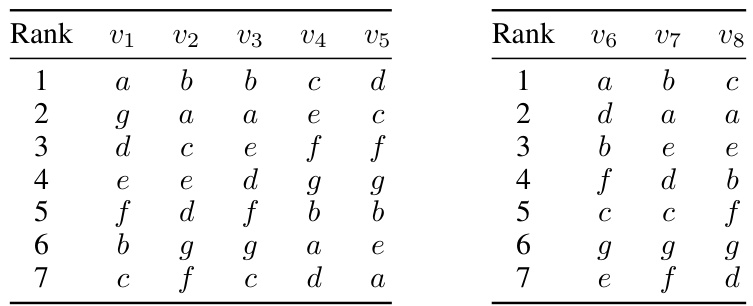

This figure shows the pairwise majority relationships between 9 candidates (c*, four c+, and four c−). Solid lines show the majority preference between pairs of candidates. In particular, c* beats all other candidates in pairwise comparisons, and each c+ candidate beats each c− candidate. The structure within the c+ and c− candidates is cyclical. This graph is used to illustrate a scenario demonstrating that even with a clear majority preference structure, it is not always possible to find a linear reward function that reflects this structure while also satisfying the Pareto Optimality criterion.

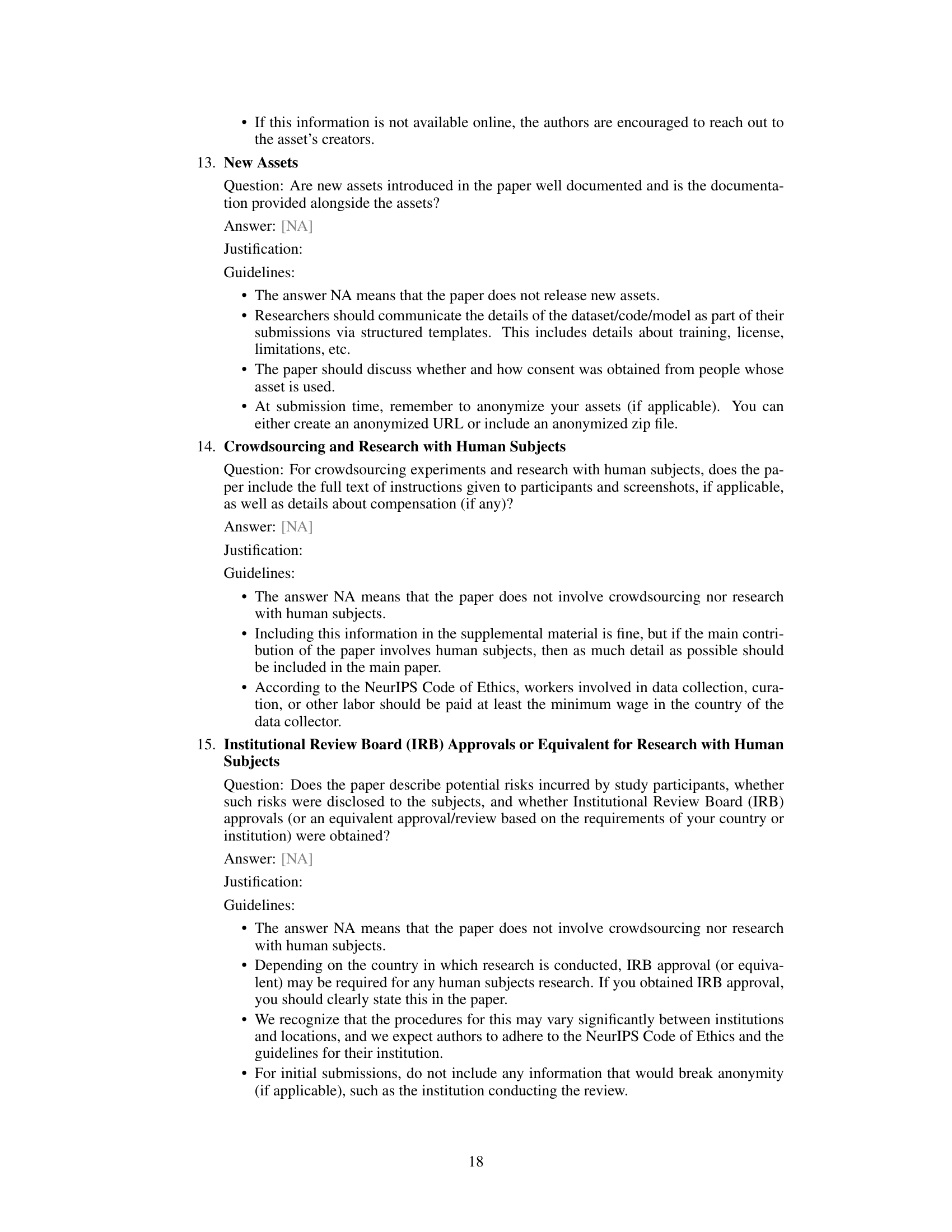

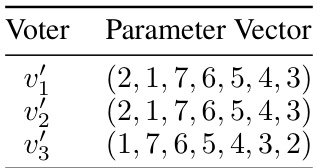

This table shows five different profiles of voter preferences that are consistent with the pairwise majority graph described in Figure 1. Each profile shows which candidate is Pareto dominated by c*, demonstrating a violation of Pareto optimality in linear rank aggregation rules. The notation 1:(2,1,3,4) indicates that one voter has a ranking conforming to the pattern described in equation (4), with the specific order of candidates 2, 1, 3, 4.

In-depth insights#

RLHF Axiomatic#

The heading ‘RLHF Axiomatic’ suggests an exploration of Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) through the lens of axiomatic analysis. This approach is insightful because it moves beyond empirical evaluations to examine the fundamental properties and principles underlying RLHF reward model aggregation. Axiomatic analysis provides a rigorous framework for evaluating the fairness, efficiency, and consistency of various aggregation methods. The core idea is to identify desirable properties (axioms) for RLHF reward functions and then assess if existing methods and algorithms satisfy them. This critical analysis helps expose potential shortcomings and biases in existing RLHF approaches, such as those based on maximum likelihood estimation of random utility models. Identifying axioms that are not met highlights opportunities for designing improved RLHF algorithms that better align with human values. The exploration likely involves evaluating the performance of common methods against established axioms from social choice theory, revealing the limitations of using existing methods without a deeper understanding of their axiomatic properties. This research promises to establish a novel theoretical foundation for RLHF, leading to the development of more robust, principled, and ethically sound reward learning methods.

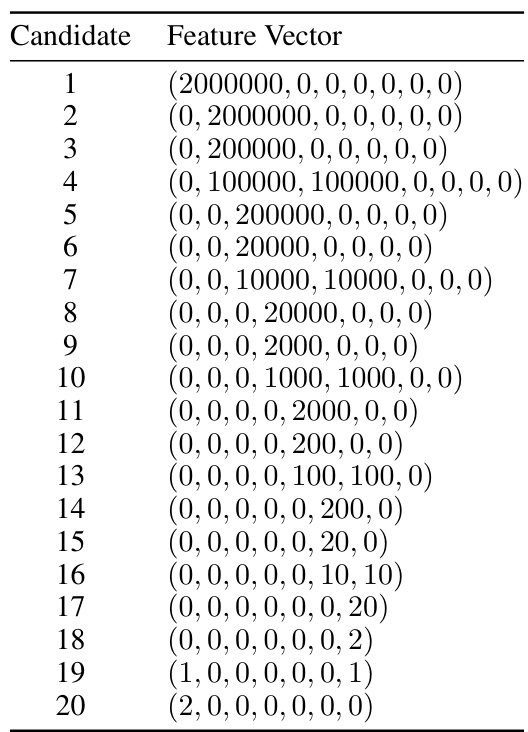

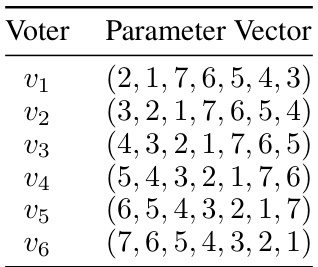

Linear Social Choice#

The concept of “Linear Social Choice” introduces a novel paradigm in social choice theory, specifically tailored for AI alignment problems. It leverages the linear structure inherent in many reward models used in reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF), significantly restricting the space of feasible aggregation rules. This linearity allows for a more constrained and potentially more tractable analysis of various aggregation methods compared to traditional social choice. The key innovation lies in its focus on aggregating linear functions that map candidate features to rewards, instead of solely focusing on preference rankings. This shift in perspective facilitates the design of rank aggregation rules with strong axiomatic guarantees, like Pareto optimality and pairwise majority consistency. Linear social choice offers a more practical and theoretically grounded approach for handling preference aggregation in contexts like RLHF, where complex preference aggregation is paramount and the reward function’s design is directly tied to AI alignment.

Loss-Based Rules#

The section on Loss-Based Rules delves into a common approach in Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), where a reward function is learned by minimizing a loss function that quantifies the disagreement between predicted rewards and human preferences. The authors critically analyze this approach through the lens of social choice theory, demonstrating that popular methods like the Bradley-Terry-Luce (BTL) model, often employed in RLHF, fail to satisfy fundamental axioms such as Pareto Optimality and Pairwise Majority Consistency. This failure highlights a critical flaw in the current RLHF practice. The analysis reveals that using a convex and nondecreasing loss function leads to the violation of basic axioms, suggesting a need for more principled reward aggregation methods. This section serves as a crucial foundation for the paper’s subsequent exploration of axiomatically sound alternatives for reward learning within RLHF. The analysis showcases the power of social choice theory to expose theoretical limitations of existing methods, paving the way for proposing innovative rules that offer strong axiomatic guarantees. By leveraging the linear structure of the reward model, the authors lay the groundwork for their new paradigm, ’linear social choice.’

Leximax Copeland#

The proposed “Leximax Copeland” method offers a novel approach to address the limitations of existing reward function aggregation methods in reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF). It cleverly integrates the axiomatically desirable properties of the Copeland voting rule – specifically, Pareto optimality and pairwise majority consistency – within the constraints of linear social choice, a paradigm where only linearly-induced rankings are feasible. The leximax strategy ensures a feasible ranking is always produced, even when the traditional Copeland ranking is infeasible. This is crucial in the RLHF setting, as the reward function must be representable in a linear form for practical use. However, this method is not without potential downsides. The computational complexity of finding the leximax Copeland ranking might be significant, especially for a large number of candidates (i.e., potential actions or responses). Also, the additional constraint introduced to ensure feasibility might lead to a sacrifice in the accuracy of the resultant ranking, potentially affecting the downstream performance of the RLHF system. Overall, Leximax Copeland represents a thoughtful blend of theoretical rigor and practical applicability, addressing the critical need for fair and consistent reward function aggregation in RLHF. Further research is needed to fully analyze the tradeoffs involved and optimize its computational efficiency.

Future of RLHF#

The future of RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback) is ripe with exciting possibilities and significant challenges. Improved scalability will be crucial, as current RLHF methods are computationally expensive and struggle to handle large datasets or complex tasks. Addressing this limitation might involve exploring more efficient algorithms, leveraging parallelism, or incorporating techniques like transfer learning. Addressing bias and safety concerns is paramount. Current RLHF systems can perpetuate existing societal biases present in training data, leading to unfair or harmful outcomes. Furthermore, ensuring the safety and robustness of RLHF-trained AI agents remains a challenge. New methods for human feedback collection are needed. Current practices for gathering human preferences are often tedious and costly, hindering widespread adoption. This requires innovative ways to collect more informative, reliable, and efficient human feedback, perhaps incorporating techniques from active learning or preference elicitation. Finally, a deeper theoretical understanding is essential to push the field forward. We need a stronger understanding of the properties of different RLHF methods, their limitations, and their ability to learn human values effectively. This could involve bridging the gap between RLHF and social choice theory, creating formal guarantees for the properties of RLHF, and developing better methods for evaluating RLHF-trained systems.

More visual insights#

More on tables

This table presents five different voter profiles, each consistent with the pairwise majority graph described in the paper. Each profile demonstrates a situation where a particular candidate (other than c*) is ranked above c*, but where the ranking violates Pareto optimality because c* Pareto dominates that candidate. The notation ‘1: (2,1,3,4)’ indicates a single voter with a ranking following a specific pattern described in equation (4) of the paper. The patterns ensure that all pairwise relationships (voter preferences) are satisfied, illustrating the failure of Pareto optimality despite the pairwise majority relationships.

This table presents different voter profiles (rankings) that maintain consistency with the pairwise majority graph. Each row corresponds to a set of voter preferences, where a number indicates a voter, and the values following the colon specify the ranking positions for the candidates (excluding c*). These profiles are constructed to demonstrate that if the Linear Kemeny rule outputs a ranking where a specific candidate (not c*) is ranked above c*, there exists a set of voter preferences that satisfies the pairwise majority condition but also violates Pareto Optimality (PO) because c* Pareto dominates that candidate.

This table presents five different voter profiles consistent with the pairwise majority graph shown in Figure 1. Each profile demonstrates a scenario where a specific candidate (other than c*) is ranked above c*, despite c* Pareto-dominating that candidate. The notation 1:(2,1,3,4) indicates a voter profile, where the ranking follows the pattern described in Equation (4) of the paper, with the indices (i, j, k, l) set to (2, 1, 3, 4). This table supports the proof of Theorem 3.7 by demonstrating PO violations despite the use of a pairwise majority graph to select the ranking.

This table presents example profiles that demonstrate the Pareto optimality violation of the Linear Kemeny rule. Each row corresponds to a distinct voter profile which is consistent with the pairwise majority graph (shown in Figure 1). The notation used is as follows: 1:(2,1,3,4) means one voter has a ranking in the form described in equation (4) with (i,j,k,l) = (2,1,3,4). For each candidate (except c*), the table provides profiles in which the candidate is Pareto-dominated by c*. In other words, for each of these candidates, there exists a profile that is consistent with the pairwise majority relationship such that the ranking generated violates Pareto optimality.

This table presents five voter profiles consistent with the pairwise majority graph described in Figure 1. Each profile demonstrates a scenario where a specific candidate (other than c*) is ranked above c*, but is Pareto dominated by c*. The profiles are designed to illustrate the failure of Pareto Optimality in linear rank aggregation rules.

Full paper#