↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Estimating mutual information (MI) between high-dimensional variables is computationally expensive, limiting its application in complex systems. Current techniques struggle with dimensionality, often requiring unrealistic sample sizes for accurate estimates, especially when dealing with data above tens of dimensions. This issue is widespread across various scientific fields, hindering our ability to understand complex dependencies.

This paper introduces Latent MI (LMI) approximation. LMI cleverly leverages low-dimensional representations of high-dimensional variables to accurately estimate MI, even in scenarios with over 1000 dimensions. The proposed method successfully tackled two biological problems: quantifying protein interaction information using protein language models and studying cell fate information from scRNA-seq data. LMI’s superior performance over existing MI estimators demonstrates its potential to significantly impact fields like genomics, neuroscience, and ecology.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with high-dimensional data, offering a novel, efficient method for approximating mutual information. It addresses a significant challenge in many fields, enabling deeper insights into complex systems and advancing research on protein interactions and cellular dynamics. The LMI approximation, introduced here, opens new avenues for research by allowing the analysis of high-dimensional relationships previously inaccessible due to computational constraints.

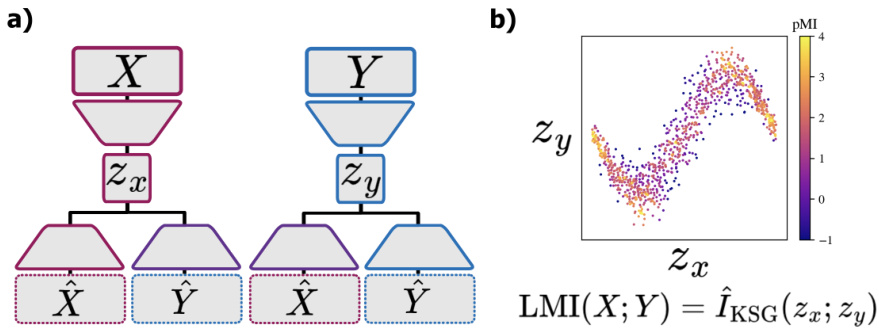

Visual Insights#

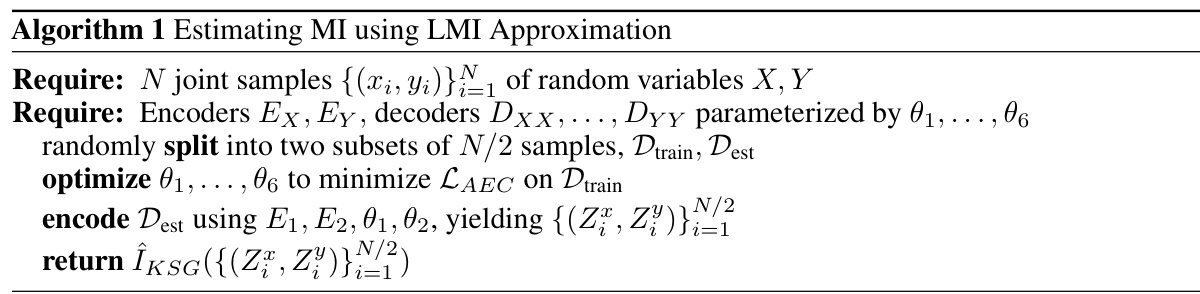

This figure illustrates the two-step process of the Latent Mutual Information (LMI) approximation method. (a) shows how high-dimensional data points X and Y are first mapped to lower-dimensional representations Zx and Zy using a neural network-based embedding. This embedding aims to preserve the mutual information between X and Y in the lower-dimensional space. (b) shows that, once the data is in low-dimensional space, a non-parametric MI estimator (KSG) is applied to estimate the mutual information between Zx and Zy. The KSG estimator achieves this by averaging over the pointwise mutual information (PMI) contributions from all pairs of points.

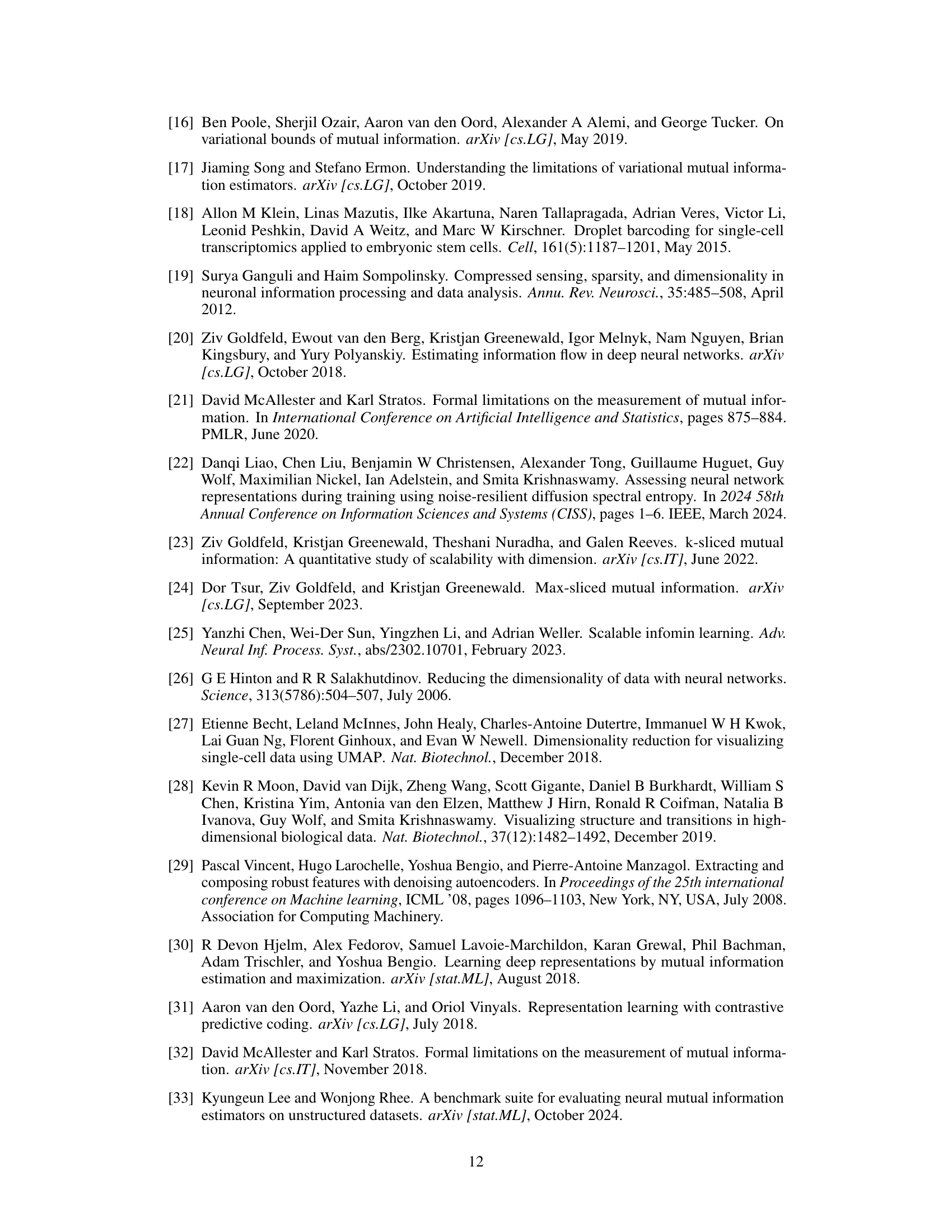

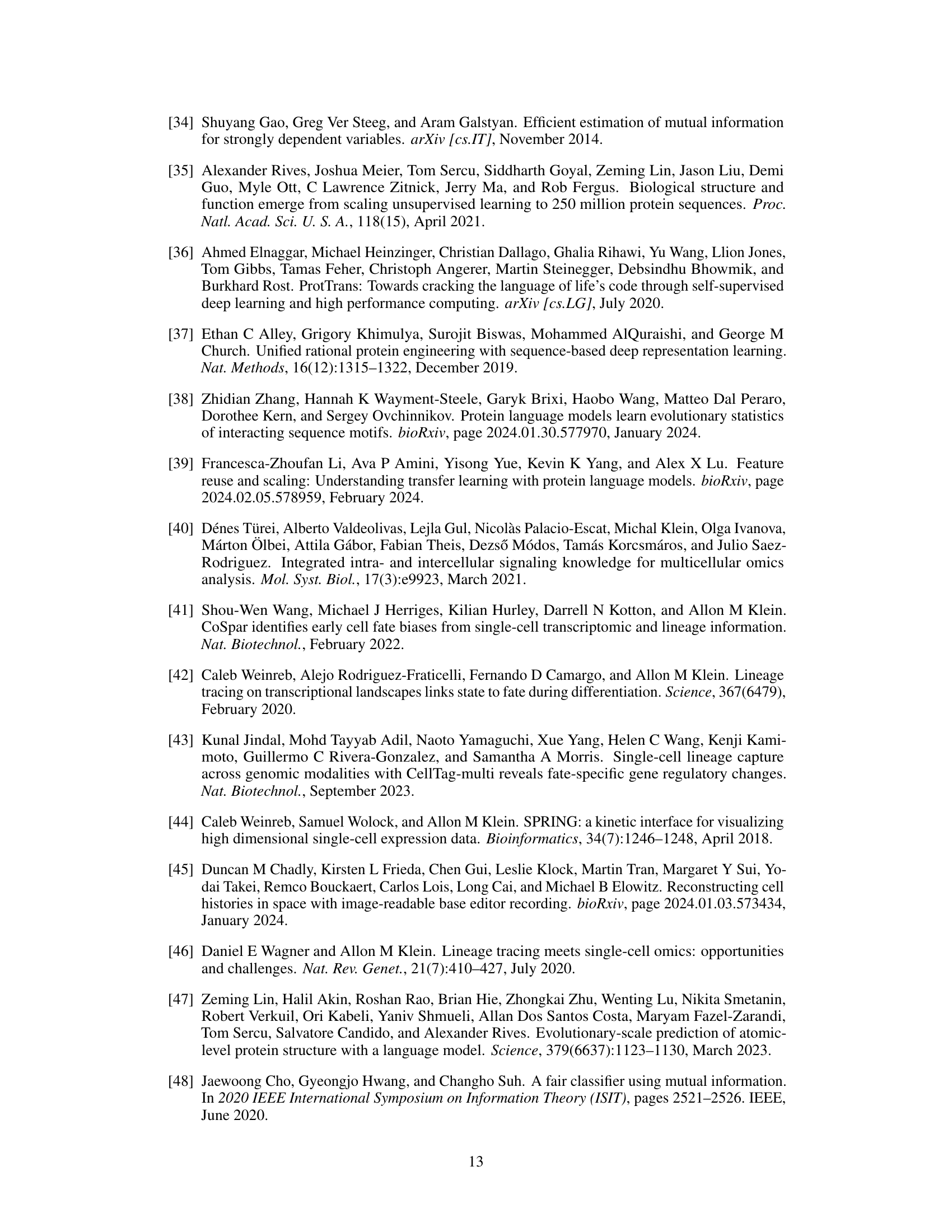

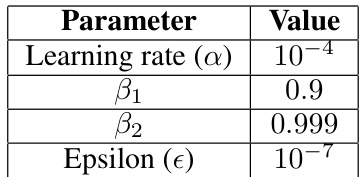

This table lists the hyperparameters used for the Adam optimizer in the Latent Mutual Information (LMI) approximation method. It shows the values used for the learning rate, beta1, beta2, and epsilon.

In-depth insights#

High-dim MI Estimation#

Estimating mutual information (MI) for high-dimensional variables presents a significant challenge due to the curse of dimensionality, where the number of samples needed for accurate estimation grows exponentially with the number of dimensions. Existing non-parametric methods struggle beyond tens of dimensions, making them impractical for many real-world applications involving high-dimensional data like genomics or image analysis. This necessitates the development of novel techniques capable of reliably estimating MI in such high-dimensional scenarios. Dimensionality reduction is key to solving this problem, and approaches which skillfully embed high-dimensional data in a lower-dimensional space while preserving the essential dependence structure, show promise. Variational methods also provide a route, offering tractable ways to approximate MI via bounds on the Kullback-Leibler divergence. However, challenges remain around the accuracy and reliability of these approximations, particularly when dealing with complex, non-Gaussian distributions. Thus, research continues to explore improved dimensionality reduction techniques, tighter variational bounds, and new estimator designs optimized for high-dimensional data.

Latent MI (LMI) Method#

The Latent Mutual Information (LMI) method offers a novel approach to estimating mutual information (MI) in high-dimensional data by leveraging low-dimensional representations. Its core innovation lies in using a neural network architecture to learn compressed representations of the high-dimensional variables, effectively reducing the dimensionality of the MI estimation problem. This strategy mitigates the computational challenges associated with directly estimating MI in high dimensions, which often suffers from the “curse of dimensionality.” The method’s effectiveness relies on the assumption that the underlying dependencies between the high-dimensional variables can be captured by their low-dimensional counterparts. This makes LMI particularly suitable for data exhibiting low-dimensional structure, where a significant portion of the information is encoded within a smaller subspace. LMI utilizes a non-parametric MI estimator on these learned representations, ensuring robustness and avoiding the restrictive assumptions of parametric methods. Furthermore, the method’s simplicity and parameter efficiency make it readily applicable across various domains, promising scalable MI estimation even with limited data samples. However, its success hinges on the accuracy of the learned low-dimensional representations, making it crucial to carefully assess the effectiveness of dimensionality reduction techniques in any given application.

Biological Applications#

The heading ‘Biological Applications’ suggests a section focusing on the practical uses of the research within a biological context. This could involve the application of novel algorithms or techniques developed in the paper to solve problems in various biological domains. High-dimensional data analysis, a common theme in modern biology (e.g., genomics, proteomics, imaging), is likely to be leveraged in these applications. Potential applications might include inferring gene regulatory networks from single-cell RNA sequencing data or predicting protein-protein interactions using protein language models. The success of these applications would depend heavily on the ability of the methods to handle high-dimensionality and capture complex relationships, making the results particularly relevant to fields struggling with the ‘curse of dimensionality’. The discussion could also highlight limitations in applying the methods to biological data and address the need for further validation in real-world biological systems. Emphasis on the interpretability of the results is vital in biological research; therefore, the section might also discuss how the approach helps to gain biological insights, beyond the quantitative measurements.

LMI Limitations#

The LMI (latent mutual information) method, while offering a novel approach to high-dimensional MI estimation, has inherent limitations. Its accuracy heavily relies on the assumption of low-dimensional underlying structure within the high-dimensional data. If this assumption is violated, and the true dependence structure is inherently high-dimensional, LMI’s performance suffers significantly. The method also inherits limitations from the KSG estimator it utilizes, notably its instability with strongly dependent variables. The choice of latent space dimensionality is crucial but lacks a definitive, theoretically-grounded optimal selection method. While heuristics are suggested, finding the ideal dimensionality requires experimentation, impacting efficiency. Furthermore, the cross-prediction loss used for regularization may not be universally effective, potentially failing to accurately capture dependencies in data with specific symmetries or distributions. Therefore, while promising, the applicability of LMI needs careful consideration of the data characteristics and potential limitations.

Future of LMI#

The future of Latent Mutual Information (LMI) approximation hinges on addressing its current limitations and capitalizing on its strengths. Improving the stability and accuracy of LMI, especially when dealing with high-dimensional data exhibiting complex, non-low-dimensional structures, is crucial. This might involve exploring alternative neural network architectures, loss functions, and regularization techniques beyond the cross-prediction approach. Developing theoretical guarantees for LMI’s performance under various data distributions and dependence structures will enhance its reliability and broaden its applicability. Benchmarking against more diverse datasets is key for assessing its generalizability and uncovering potential failure modes, particularly in non-Gaussian settings. Future research should focus on incorporating domain knowledge to further improve LMI’s accuracy and interpretability in specific application areas. Expanding the range of problems LMI can address could also lead to development of new algorithms and theoretical insights. Finally, developing user-friendly tools and software packages will make LMI more accessible to a wider scientific community. By improving robustness, and expanding its theoretical grounding, LMI could transform the landscape of high-dimensional dependence analysis and information theory.

More visual insights#

More on figures

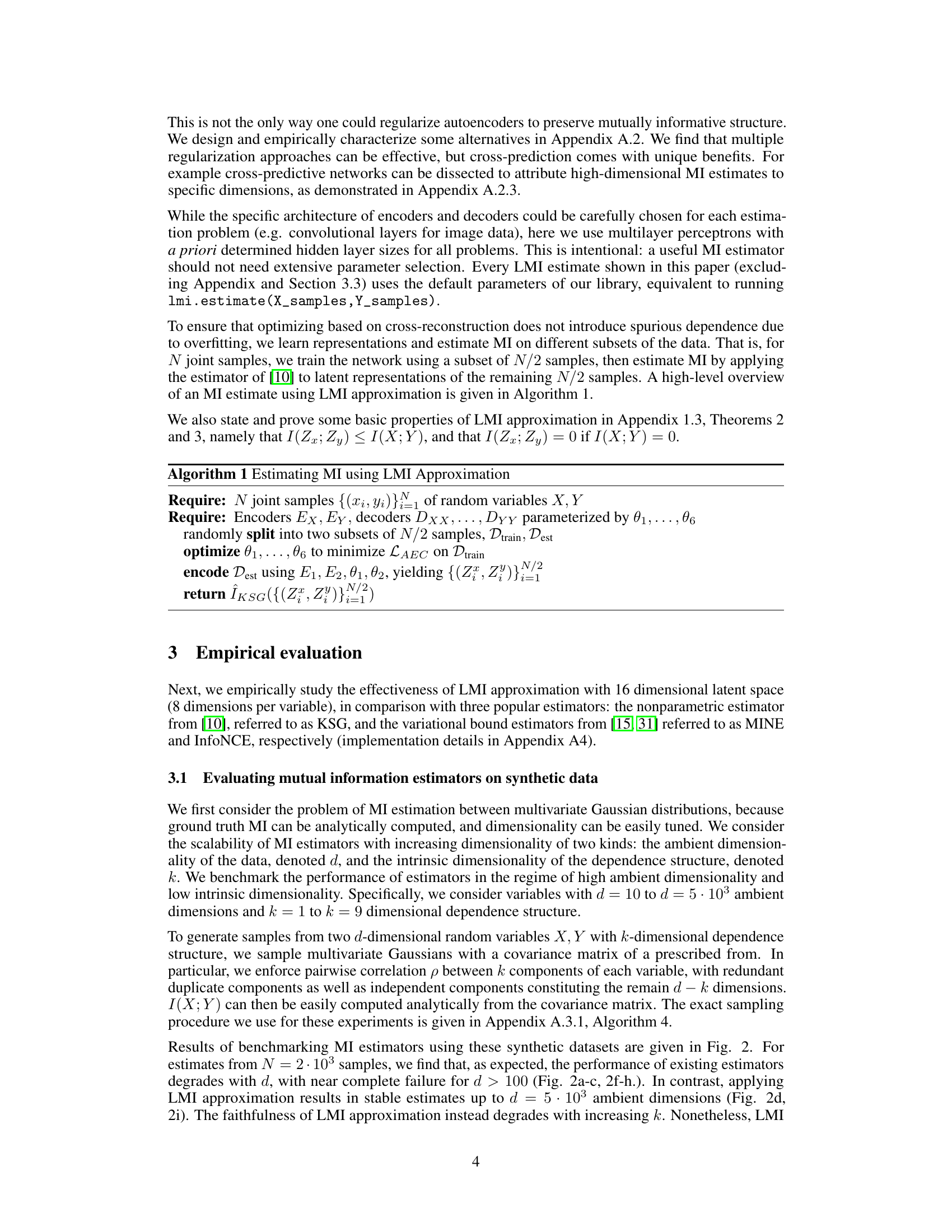

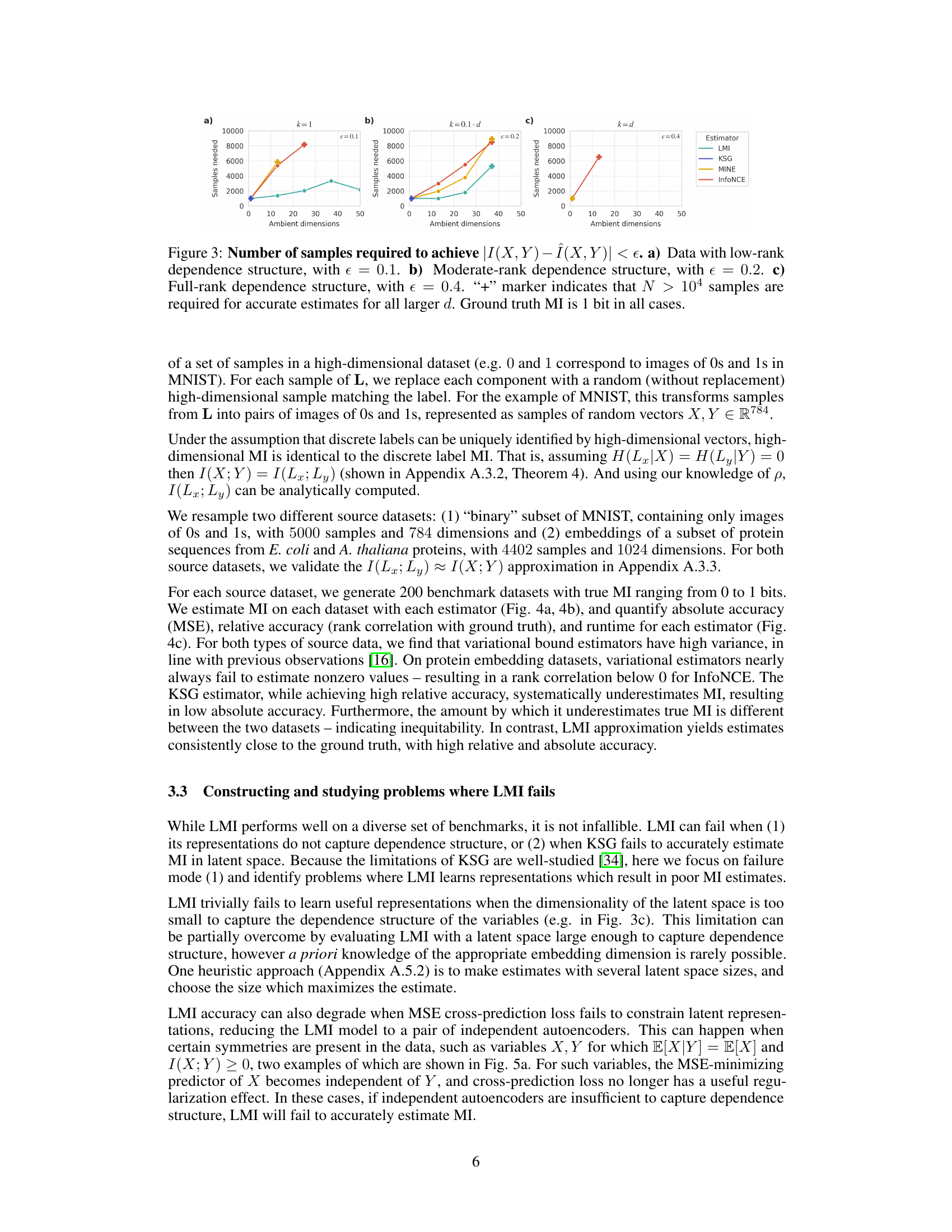

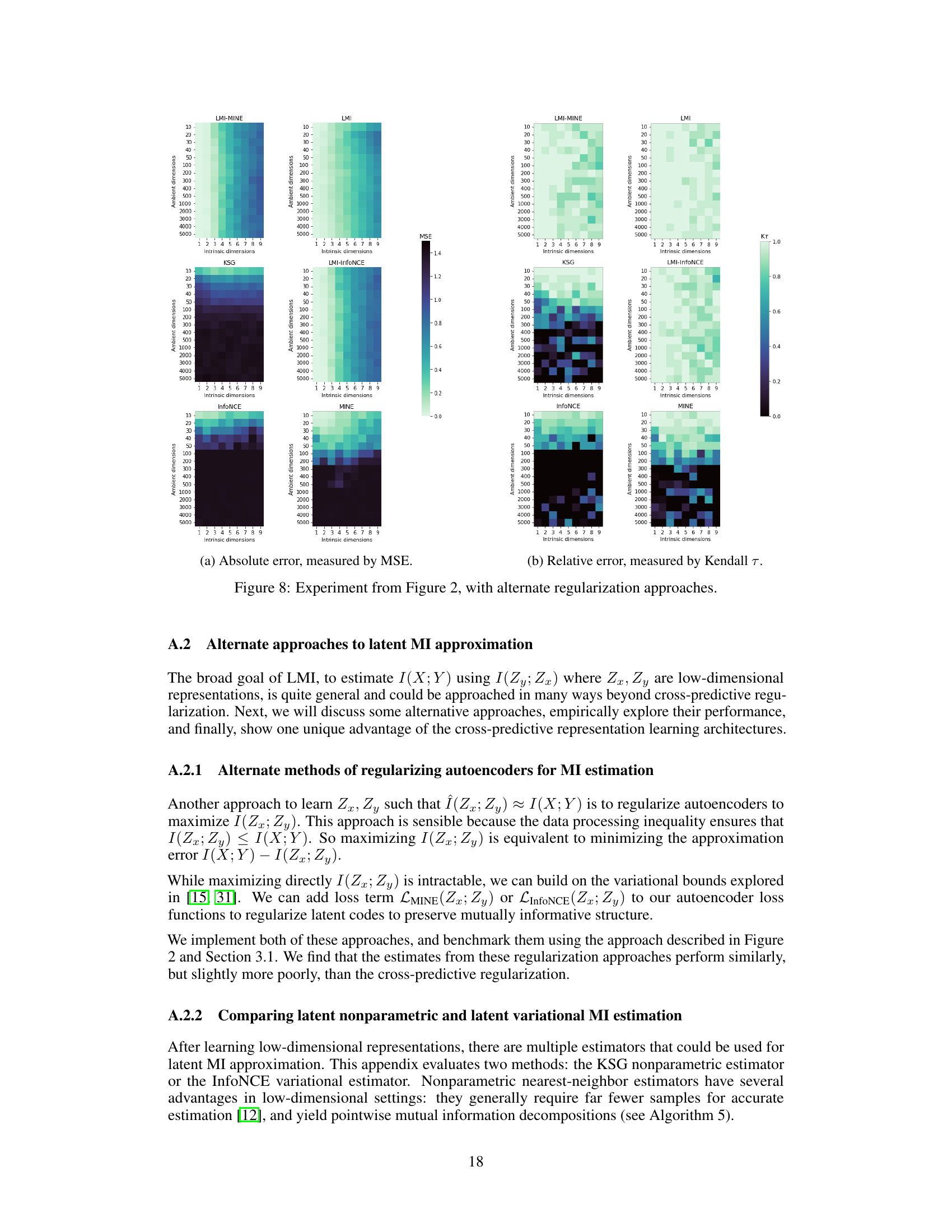

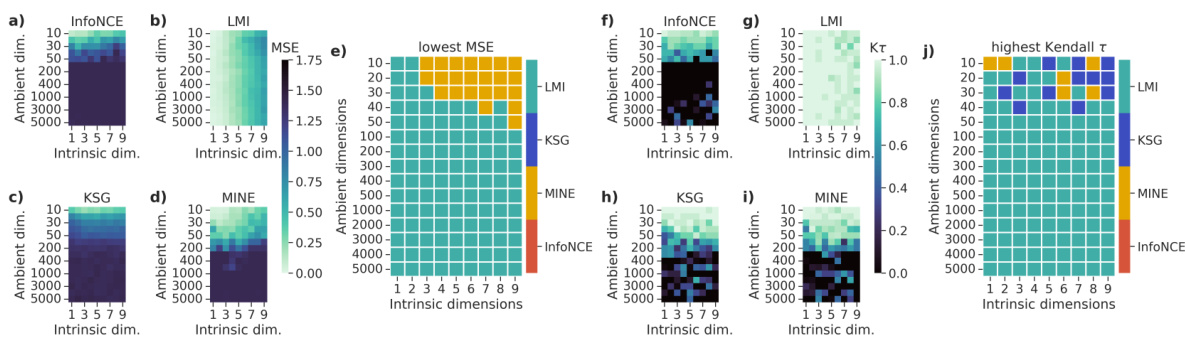

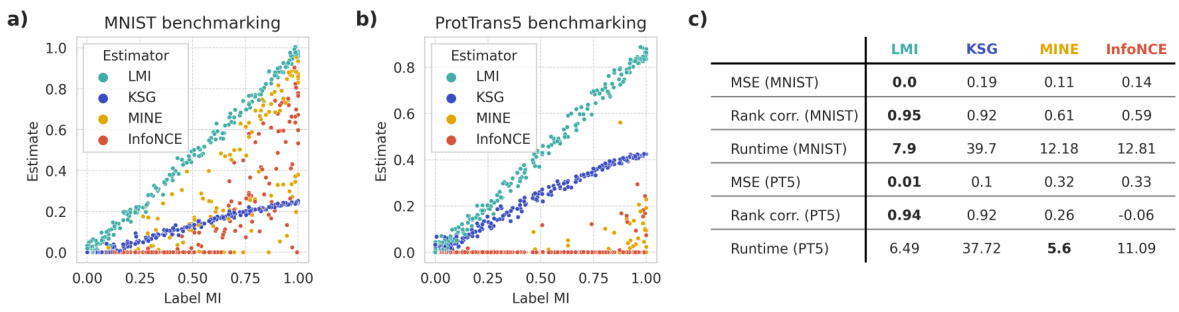

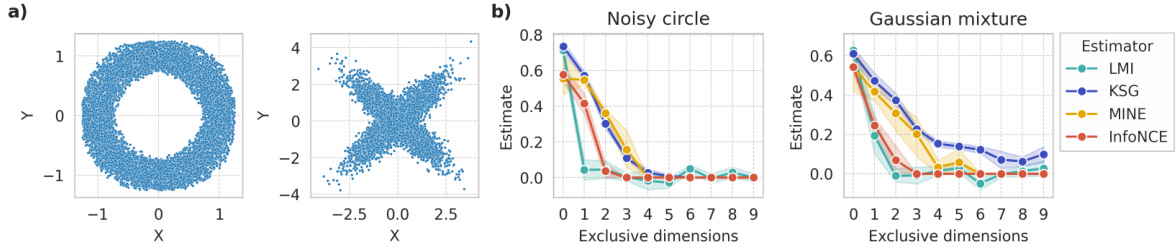

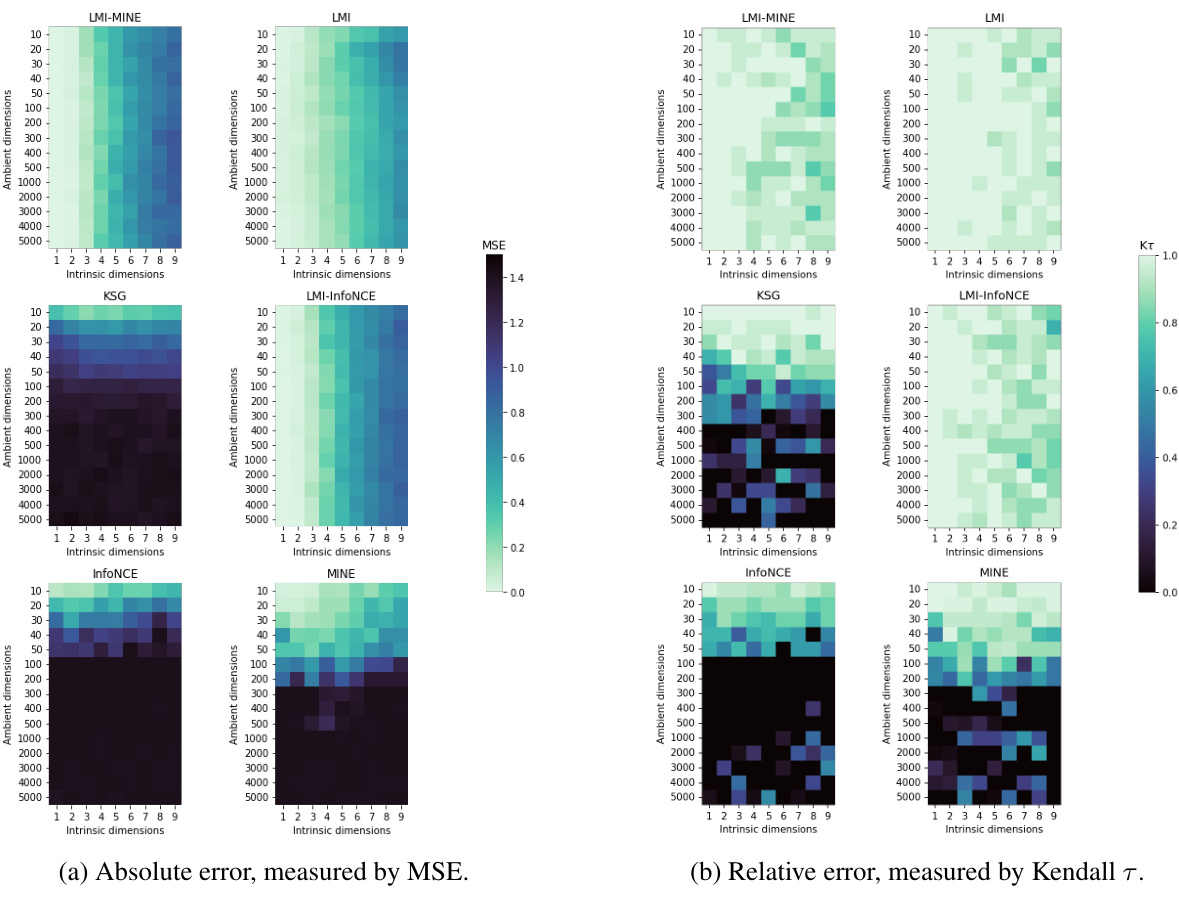

This figure compares the performance of four mutual information (MI) estimators (InfoNCE, MINE, KSG, and LMI) across different dimensionalities and intrinsic dimensions of the data. It shows that LMI outperforms the other three estimators, especially in high-dimensional settings with low intrinsic dimensionality. The performance is evaluated using both absolute accuracy (MSE) and relative accuracy (Kendall τ).

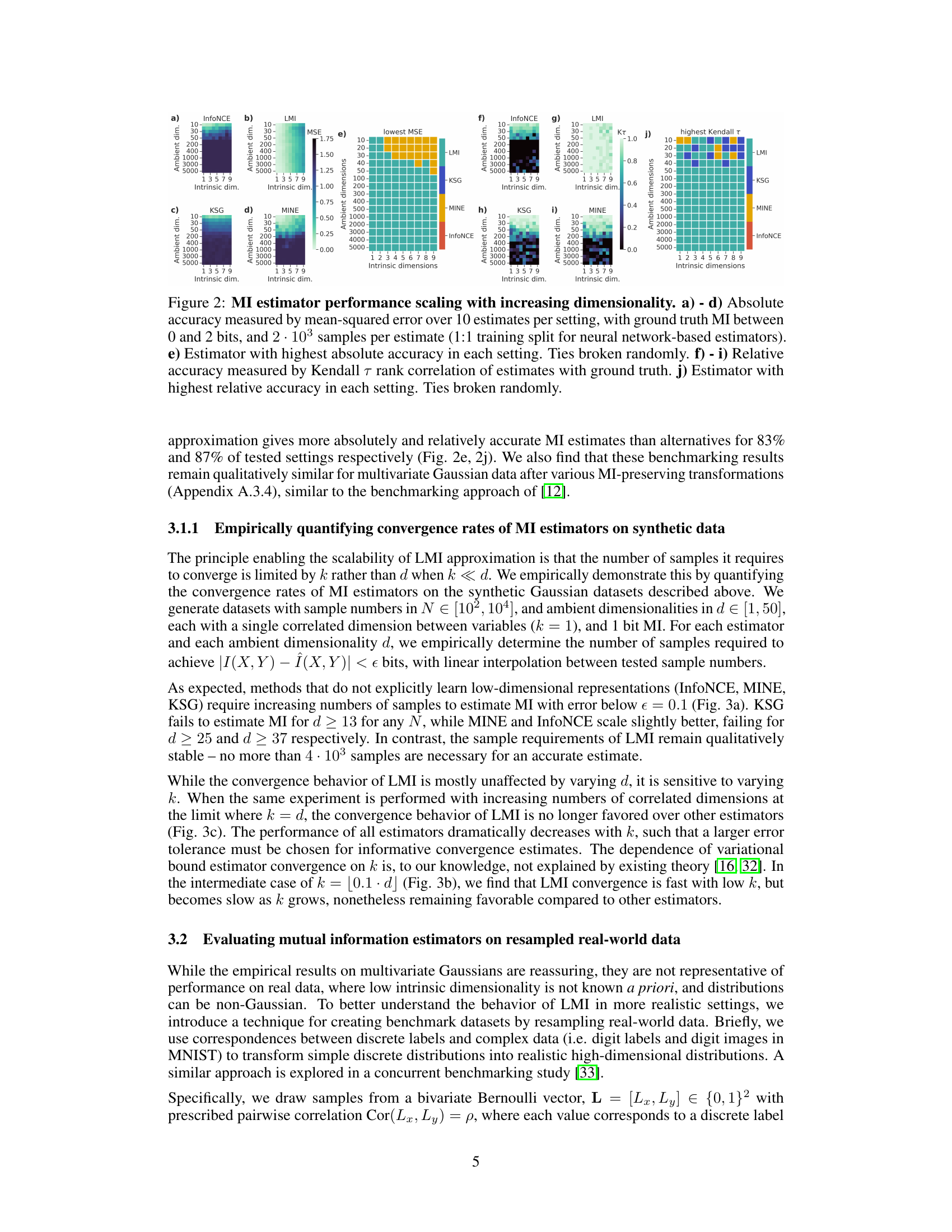

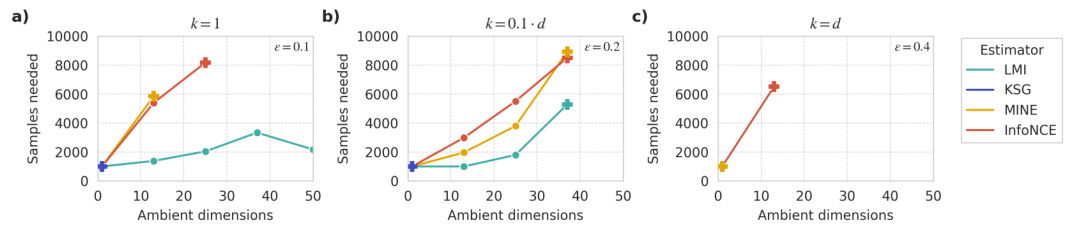

This figure shows the number of samples required by different mutual information estimators to achieve a specific estimation error (€) under various ambient and intrinsic dimensionalities. It demonstrates the scalability of LMI approximation compared to KSG, MINE, and InfoNCE. The plots show that while other methods struggle to converge as dimensionality increases, LMI maintains stable performance provided the dependence structure has low intrinsic dimensionality (k). As k approaches d (full-rank dependence), all methods struggle.

This figure compares the performance of four different mutual information (MI) estimators across various dimensionalities and dependence structures. The performance is evaluated using both absolute accuracy (MSE) and relative accuracy (Kendall’s tau). LMI consistently outperforms other methods, especially in high dimensions, demonstrating its effectiveness in approximating MI for high-dimensional data with low-dimensional dependence structures.

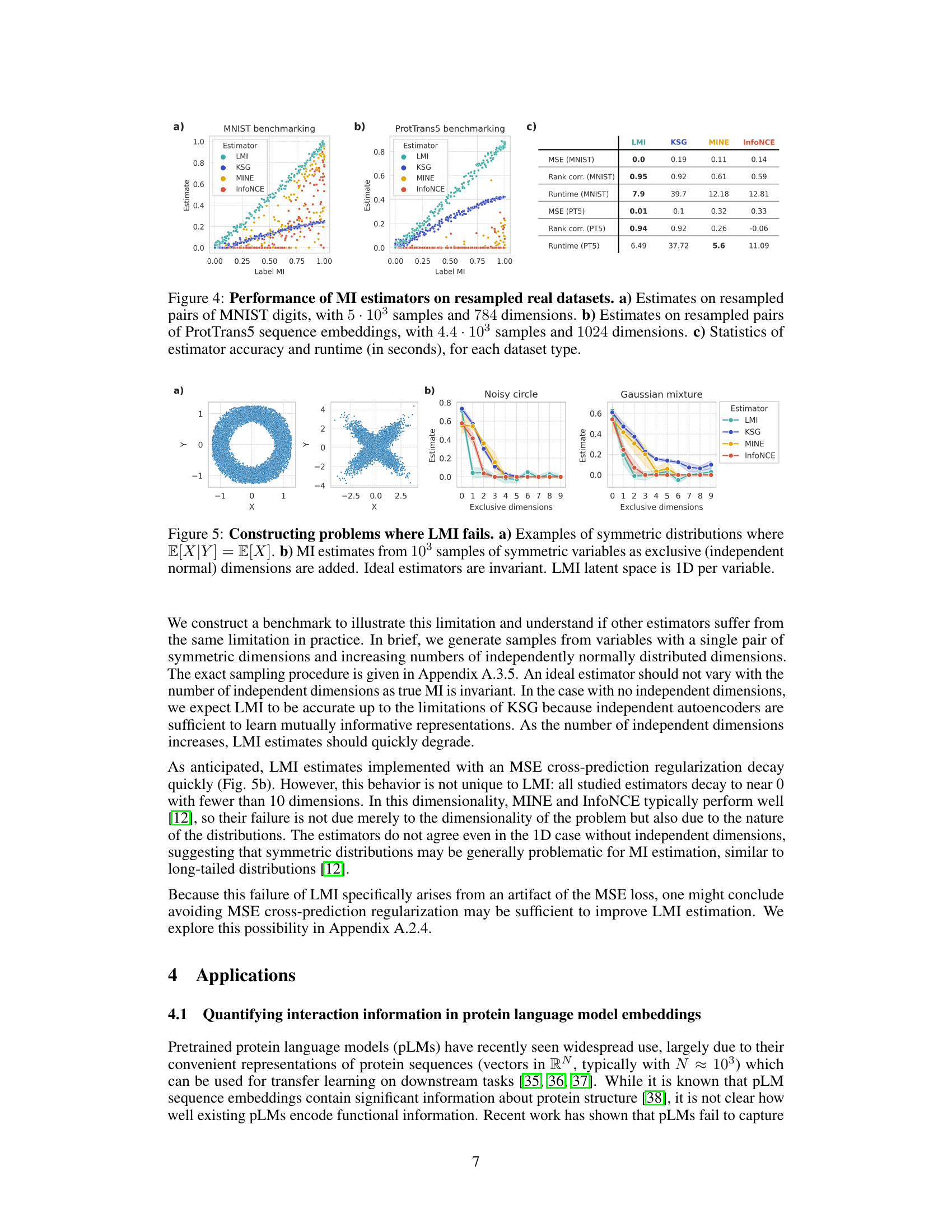

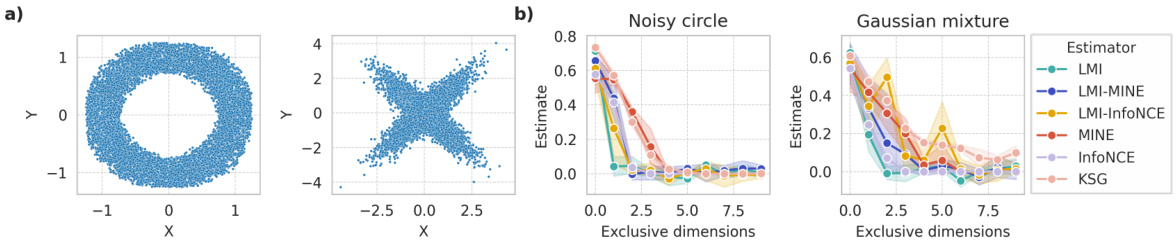

This figure demonstrates a scenario where the LMI (Latent Mutual Information) approximation method fails. Panel (a) shows examples of symmetric distributions where the conditional expectation of X given Y is equal to the expectation of X. Panel (b) shows how MI estimates from various methods change as independent dimensions are added to these symmetric distributions. In an ideal case, the MI estimates shouldn’t vary as these independent dimensions don’t affect the MI between X and Y. The experiment highlights a limitation of LMI in handling symmetric data.

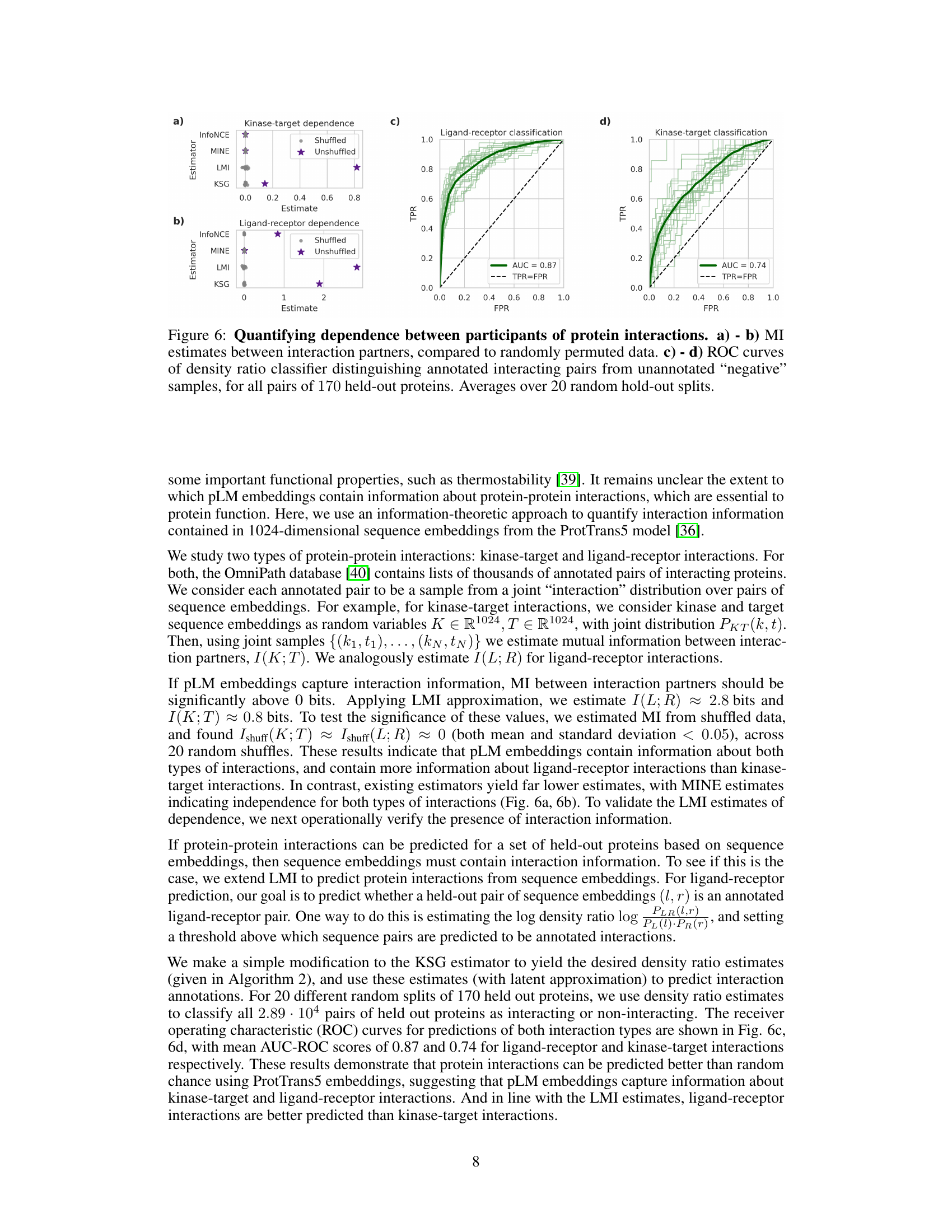

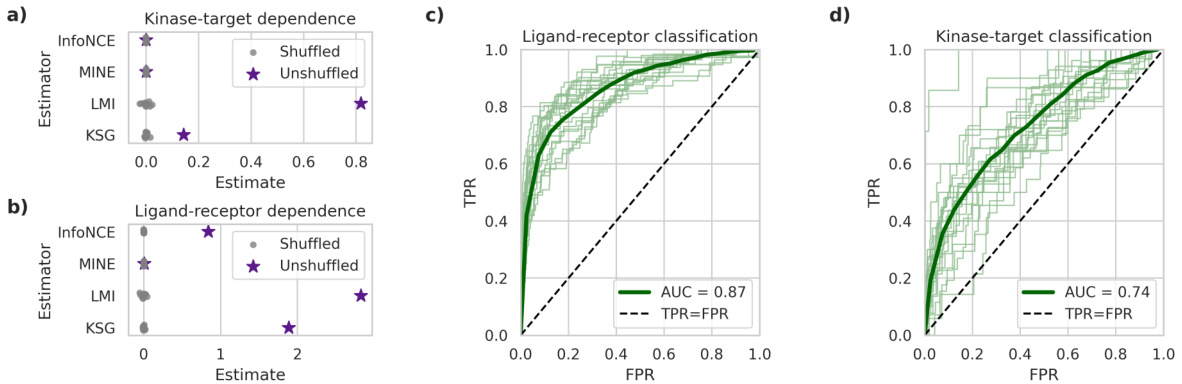

This figure presents the results of applying the latent mutual information (LMI) approximation method to quantify the statistical dependence between interacting protein pairs (kinase-target and ligand-receptor interactions). Panels (a) and (b) show MI estimates from the LMI method, and other methods, comparing estimates from real data to those obtained from shuffled (randomized) data which serves as a negative control. Panels (c) and (d) display ROC curves for a classification model designed to distinguish between true interacting protein pairs and non-interacting pairs. The ROC curves further validate the information captured by the LMI method and protein language model embeddings.

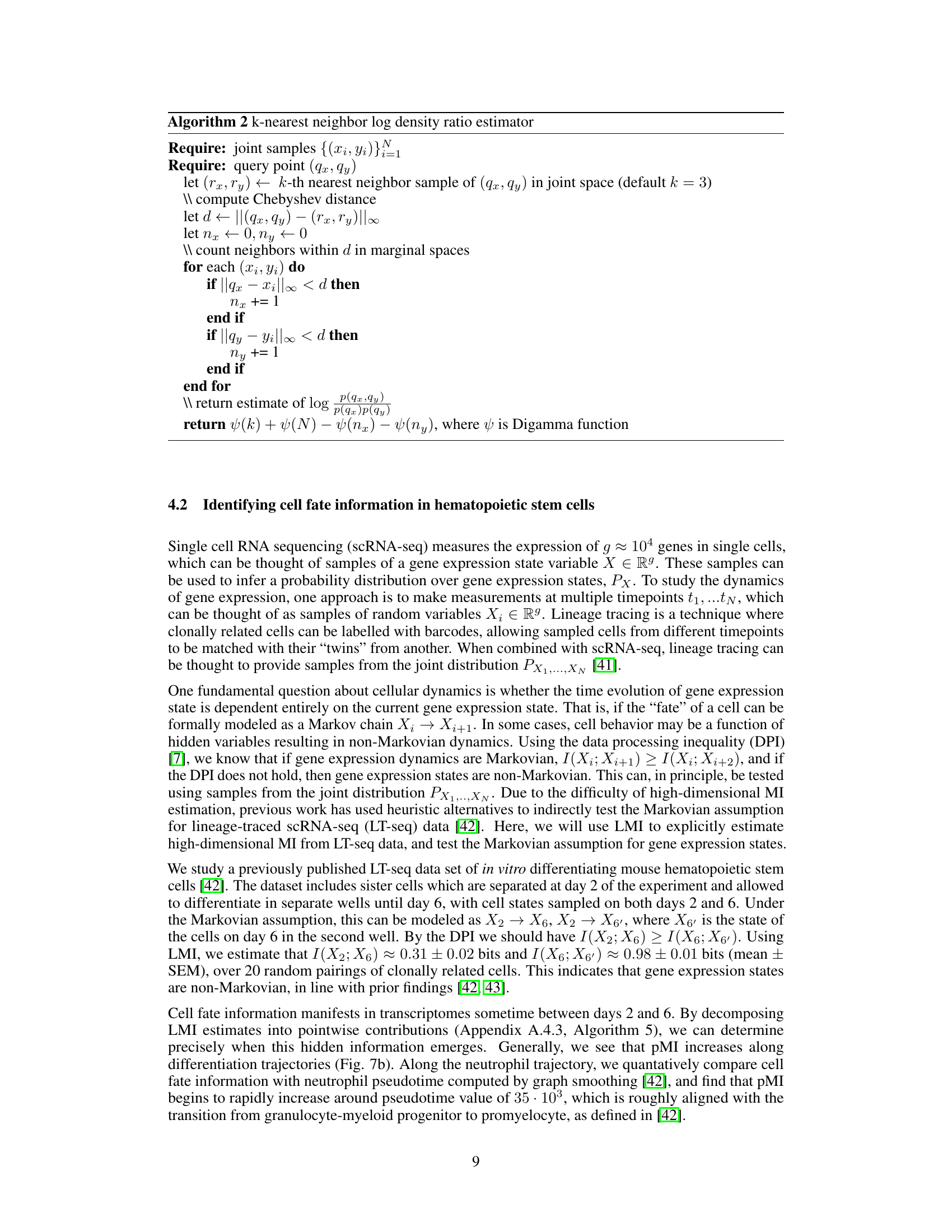

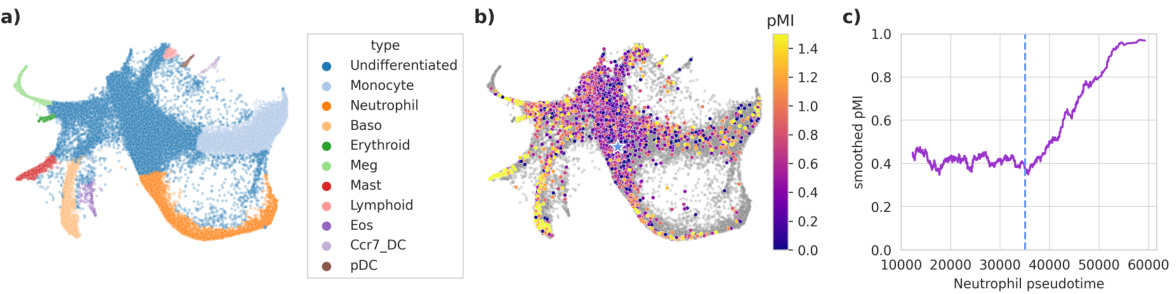

This figure shows the results of applying the latent mutual information (LMI) method to single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data from a study of hematopoietic stem cells. Panel (a) shows a 2D representation of the scRNA-seq data, colored by cell type. Panel (b) shows a heatmap of pointwise mutual information (pMI) between pairs of sister cells, calculated using LMI. Panel (c) shows a smoothed version of the pMI along the neutrophil differentiation trajectory, highlighting a sharp increase in pMI around a specific pseudotime value.

This figure shows the performance of different mutual information (MI) estimators as the dimensionality of the data increases. The plots compare the absolute and relative accuracy of four estimators: LMI, KSG, MINE, and InfoNCE. The results demonstrate that LMI outperforms the other estimators, particularly when the intrinsic dimensionality of the data is low compared to the ambient dimensionality. The accuracy is measured using mean-squared error (MSE) and Kendall’s tau correlation.

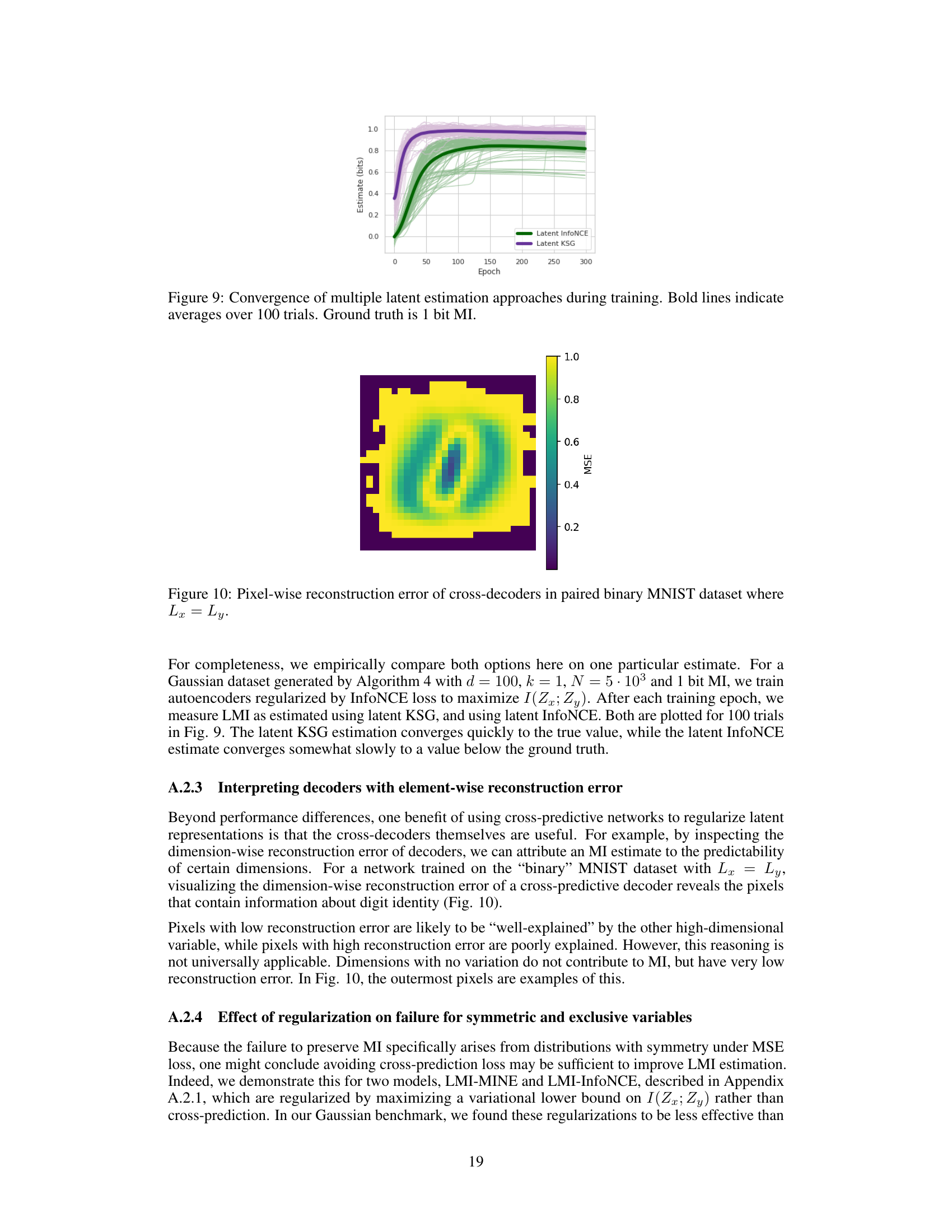

This figure shows the convergence of latent InfoNCE and latent KSG estimators during the training process. Multiple trials (100) were run, and the average performance is highlighted in bold. The ground truth mutual information (MI) value is 1 bit. The plot demonstrates how the estimations approach the true value over training epochs, illustrating the convergence behavior of the two methods.

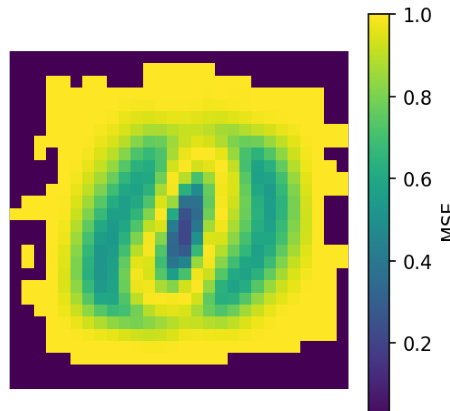

This figure shows the pixel-wise reconstruction error from the cross-decoders in a paired binary MNIST dataset where Lx=Ly. It demonstrates that the cross-predictive regularization used helps identify which pixels are most important in determining the mutual information between the variables. Pixels with low reconstruction error are better predicted by the other variable, while those with high error are not. This visualization is useful for interpreting the results of the LMI approximation.

This figure demonstrates a scenario where the Latent Mutual Information (LMI) approximation method may fail. Part (a) shows examples of symmetric distributions where the conditional expectation E[X|Y] equals the expectation of X, indicating a lack of information about X given Y. Part (b) shows how MI estimates change as independent dimensions are added to symmetric variables. In theory, an ideal MI estimator would remain invariant to the addition of these independent dimensions; however, the figure shows that multiple MI estimators, including LMI, exhibit performance degradation. This illustrates a limitation of LMI and highlights the impact of dataset characteristics on estimation accuracy.

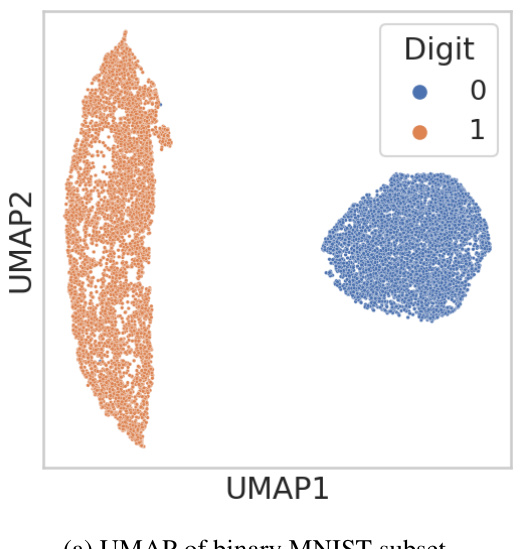

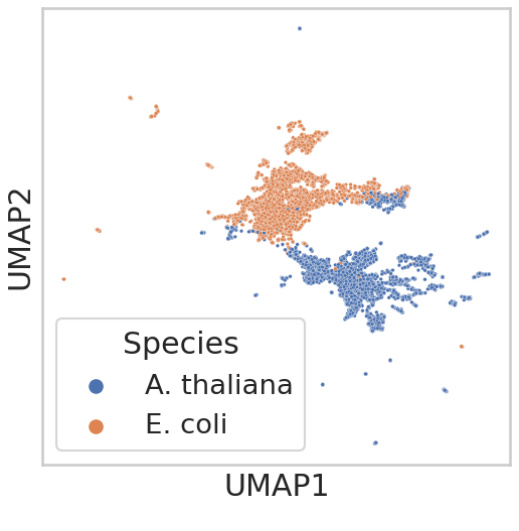

This figure shows UMAP visualizations of two datasets used for benchmarking in the paper: (a) a subset of MNIST data containing only images of 0 and 1, and (b) protein embeddings from E. coli and A. thaliana. UMAP is a dimensionality reduction technique used to visualize high-dimensional data. The clear separation of the clusters in both (a) and (b) suggests that the samples are well-separated and clustered according to their labels, providing evidence to support the assumption that the discrete labels can be uniquely identified by high-dimensional vectors. This is a key assumption for a benchmarking method used in the paper.

This figure validates the assumptions made for the cluster-based benchmarking approach used in Section 3.2 of the paper. Two UMAP plots are shown. The first (a) visualizes the separation of clusters for a binary subset of MNIST (Modified National Institute of Standards and Technology) digits, where 0 and 1 represent images of zeros and ones respectively. The second (b) shows the separation of clusters for protein sequence embeddings from Arabidopsis thaliana and Escherichia coli. The clear separation in both plots supports the assumption that the labels (digits and species) can be reliably determined from their high-dimensional vector representations, a key assumption for the cluster-based benchmarking method’s validity.

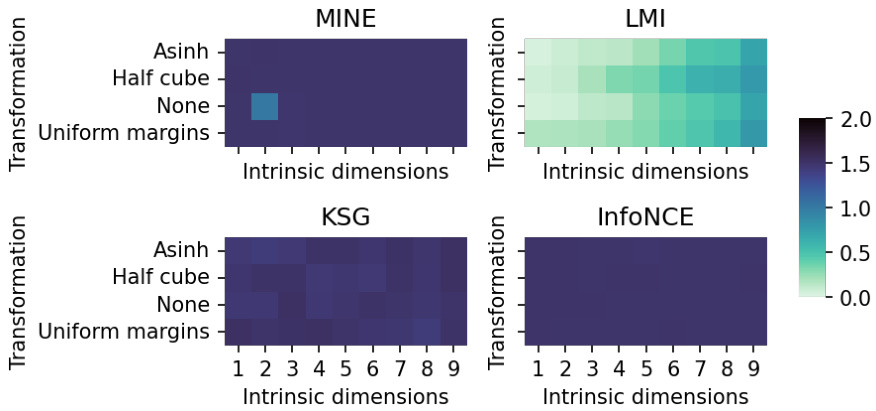

This figure shows the mean squared error (MSE) of four different mutual information (MI) estimation methods (MINE, LMI, KSG, InfoNCE) on a subset of the multivariate Gaussian benchmark dataset from [12]. The dataset consists of high-dimensional (1000 dimensions) variables with varying intrinsic dimensionality (1-9 dimensions) and different non-linear transformations (Asinh, Half cube, None, Uniform margins) applied to the data. The heatmaps show the performance of each method as a function of intrinsic dimensionality and transformation type. LMI shows consistently better performance than other methods in most cases.

The figure compares the performance of several mutual information (MI) estimators as the dimensionality of the data increases. It shows that the proposed Latent MI (LMI) method outperforms existing methods in terms of both absolute and relative accuracy, especially when the data has high ambient dimensionality but low intrinsic dimensionality. The results are presented using mean squared error (MSE) and Kendall’s tau correlation as metrics.

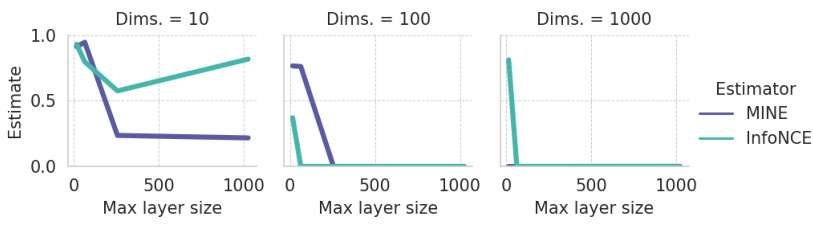

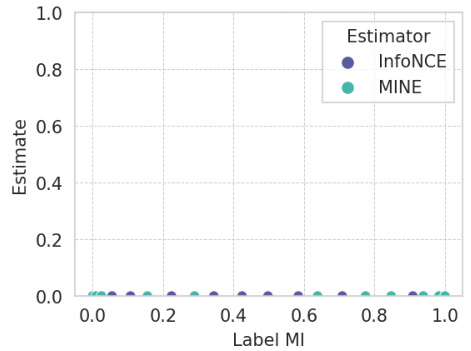

This figure presents the results of a benchmarking study comparing the performance of different mutual information (MI) estimators on the MNIST dataset. The key takeaway is that even with critic complexity equivalent to the LMI encoders (meaning neural network components designed to estimate MI), the MINE and InfoNCE estimators show poor performance when compared to the Latent Mutual Information (LMI) approach. This highlights the relative accuracy and robustness of the LMI method, particularly in scenarios with a limited number of samples and high dimensionality.

More on tables

This table lists the hyperparameters used for the Adam optimizer in the Latent Mutual Information (LMI) approximation method. It shows the values used for the learning rate (alpha), beta1, beta2, and epsilon.

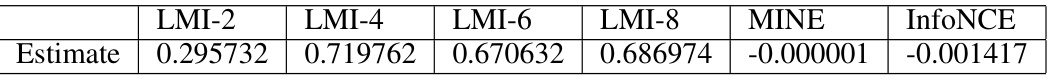

This table presents the LMI estimates obtained using different latent space sizes (2, 4, 6, and 8 dimensions) for a multivariate Gaussian dataset. The dataset is generated with 1000 ambient dimensions, 4 intrinsic dimensions, and a ground truth mutual information (MI) of 1 bit, using the method described in Figure 2 of the paper. The results are compared with MINE and InfoNCE estimates for the same dataset, showcasing how the LMI approximation’s accuracy varies with latent space size.

Full paper#