↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many cutting-edge neural network training methods depend on readily available gradients from activation functions. However, several network types, such as those used in neuromorphic computing (e.g., binary and spiking neural networks), have activation functions without useful derivatives. This necessitates the use of surrogate gradient learning (SGL), which substitutes the derivative with a surrogate. While SGL is effective, its theoretical foundations have remained elusive.

This paper tackles this issue head-on. The researchers introduce a novel framework, a generalization of the neural tangent kernel (NTK) called the surrogate gradient NTK (SG-NTK). They rigorously define this new kernel and extend existing theorems to encompass SGL, clarifying its behavior. The findings are supported by numerical experiments showing the SG-NTK closely matches SGL’s behavior in networks with sign activation functions.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with neural networks that utilize activation functions lacking standard derivatives, such as binary or spiking neural networks. It provides a theoretical foundation for surrogate gradient learning, a widely used but poorly understood technique. The generalized neural tangent kernel provides a new tool for analyzing these networks, opening avenues for more sophisticated training methods and a deeper understanding of their behavior.

Visual Insights#

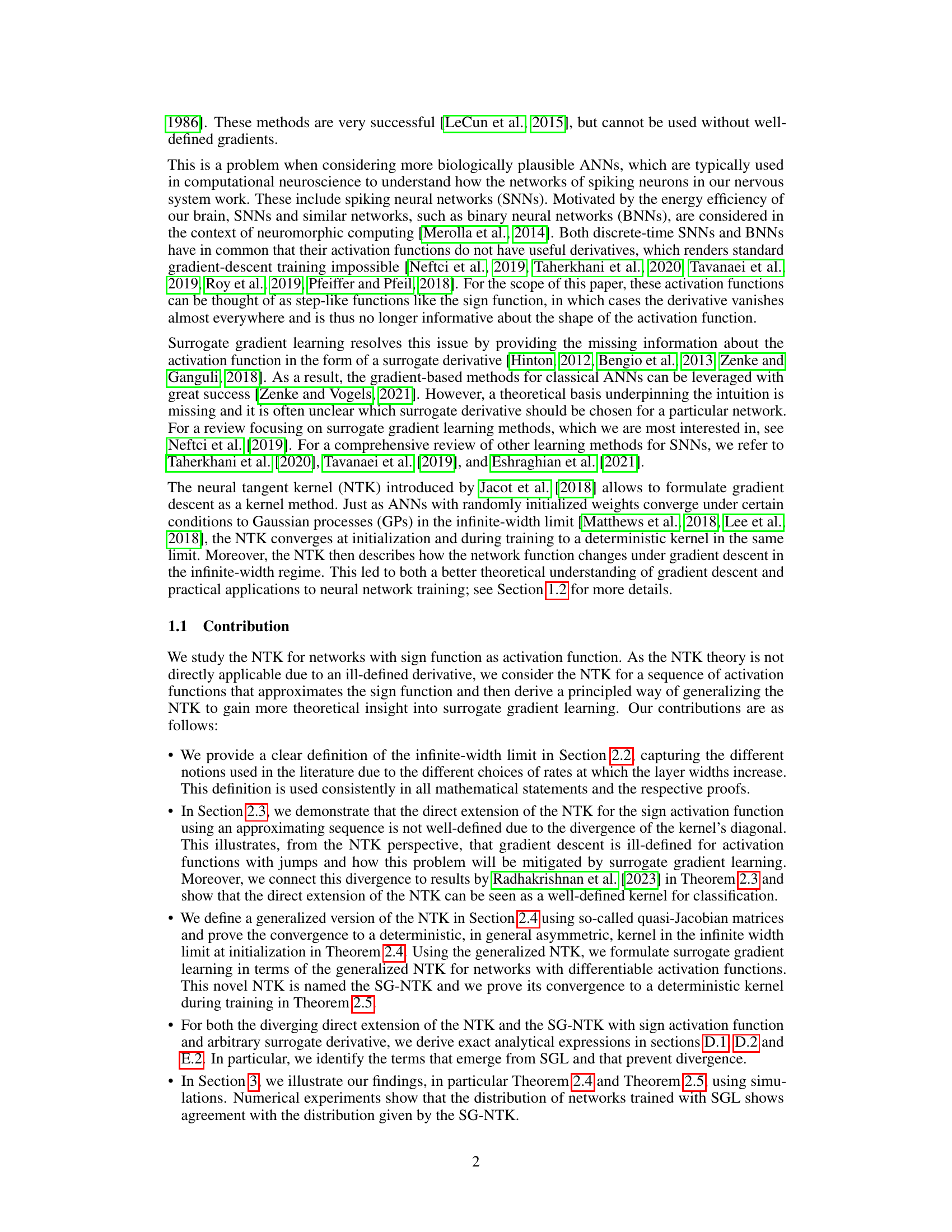

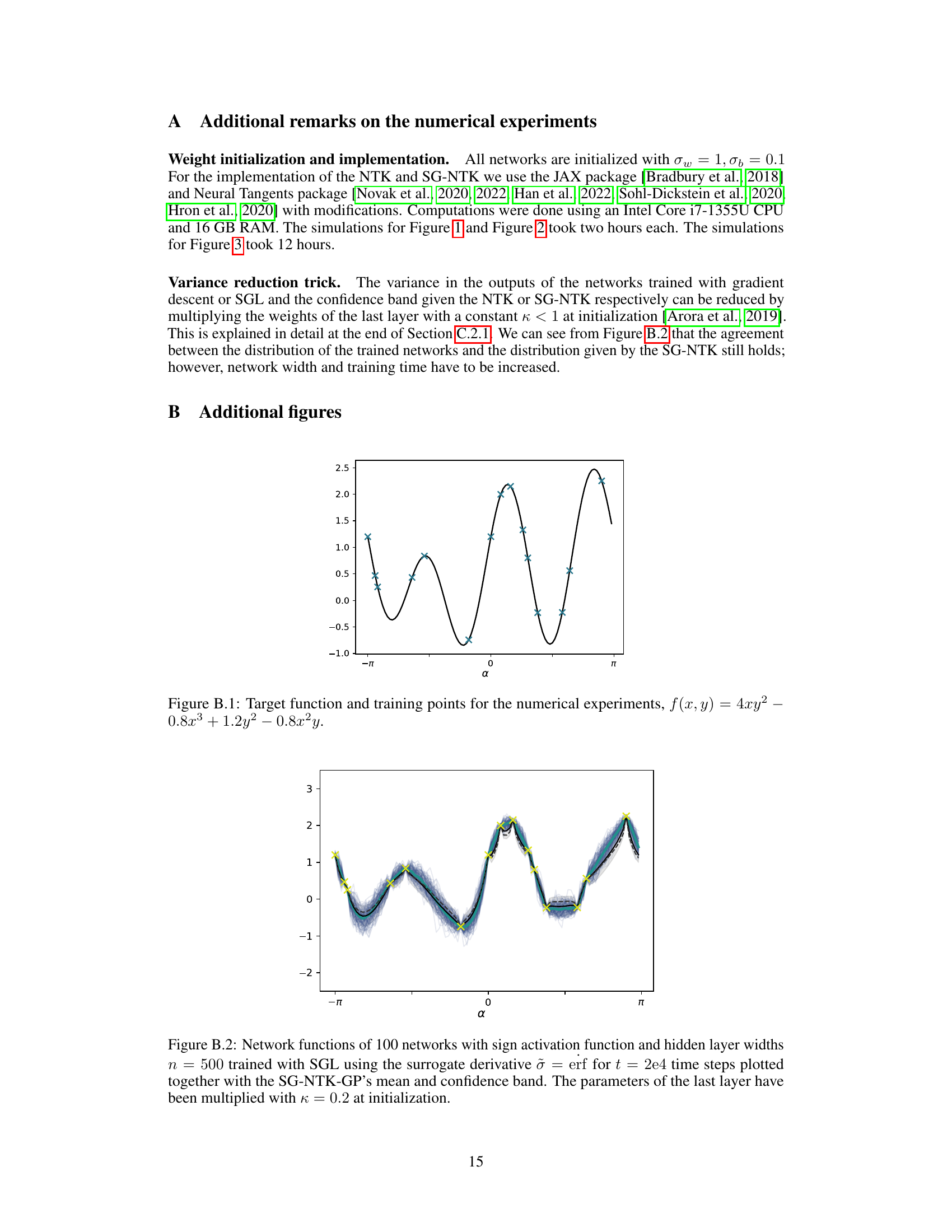

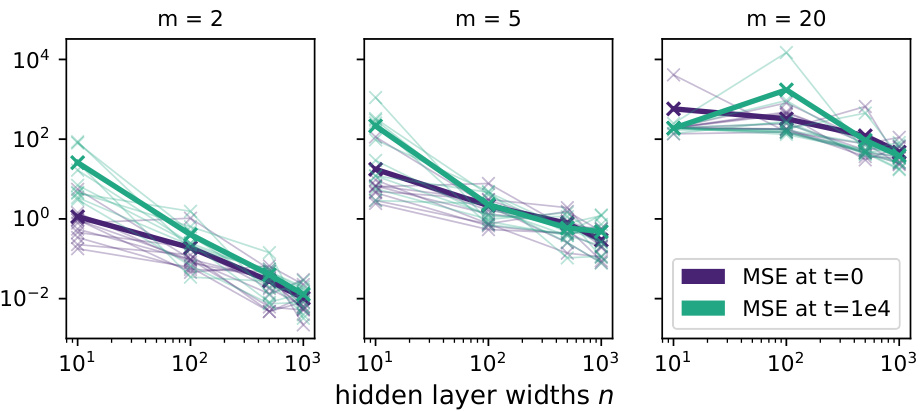

This figure shows the convergence of empirical NTKs to their analytic counterparts for various network widths (n) and activation functions (erfm with different m values). The plots are shown for both network initialization (t=0) and after training for 10000 time steps. The y-axis uses the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation to better visualize the convergence.

In-depth insights#

Surrogate Gradient NTK#

The concept of a “Surrogate Gradient NTK” (Neural Tangent Kernel) presents a compelling approach to address limitations in training neural networks with non-differentiable activation functions. The core idea is to replace the problematic derivative of the activation function with a surrogate derivative, enabling the application of gradient-based optimization methods. This approach, while effective in practice, often lacks a firm theoretical foundation. The proposed Surrogate Gradient NTK aims to provide this crucial theoretical underpinning by extending the existing NTK framework. The resulting kernel, instead of relying on true gradients, leverages surrogate gradients, allowing for the rigorous analysis of surrogate gradient learning. This analytical framework potentially offers valuable insights into why surrogate gradient learning works well in practice and guidance on selecting appropriate surrogate derivatives. Furthermore, this extension is mathematically rigorous, providing a solid theoretical basis, which enhances the credibility and understanding of the surrogate gradient method. Numerical experiments may demonstrate that the Surrogate Gradient NTK accurately captures the learning dynamics of neural networks trained with surrogate gradients, validating the framework’s practical applicability and theoretical accuracy.

Infinite-width Limit#

The concept of the ‘infinite-width limit’ is crucial in the paper’s analysis of neural networks. It provides a theoretical framework to understand the behavior of networks as the number of neurons in each layer approaches infinity. This simplifies analysis by transforming the complex, finite-dimensional dynamics of the network into a more tractable infinite-dimensional setting. Key results, such as the convergence of the network function to a Gaussian process and the convergence of the neural tangent kernel (NTK) to a deterministic kernel, are only proven rigorously in this limit. The authors acknowledge that this is a theoretical abstraction; real-world networks have finite width. However, the insights gained from the infinite-width analysis inform our understanding of how finite-width networks behave, particularly in the over-parameterized regime. The paper carefully defines the infinite-width limit, addressing multiple definitions found in the literature to ensure mathematical rigor and consistency. This detailed approach to the limit’s definition is a significant contribution, allowing for more precise theoretical statements about network behavior.

SGL’s Convergence#

The convergence analysis of Surrogate Gradient Learning (SGL) is a crucial aspect of the research paper. The authors likely demonstrate that under specific conditions, SGL converges to a solution. This would involve showing that the surrogate gradient, used to approximate the true gradient in cases where the activation function isn’t differentiable, still guides the network’s weights towards a minimum of the loss function. The analysis probably includes discussions of the choice of surrogate gradient, as well as the effects of network architecture and width on convergence speed and stability. A key aspect might be demonstrating that the convergence rate of SGL is comparable to or only slightly slower than standard gradient descent methods in the infinite-width limit. The authors may support their claims with rigorous mathematical proofs and numerical experiments that compare SGL’s performance with that of standard gradient descent and kernel regression methods. They also likely investigate the properties of the resulting networks trained with SGL, for example addressing how well the networks trained using SGL generalize to unseen data.

Sign Activation#

The concept of ‘sign activation’ in neural networks presents a unique challenge and opportunity. Sign activation, where the output is simply the sign (+1 or -1) of the input, introduces non-differentiability, hindering the use of standard gradient-based training methods. This necessitates the exploration of surrogate gradient learning (SGL) techniques, which approximate the gradient using alternative methods. The paper investigates the theoretical implications of SGL with sign activation using a generalized neural tangent kernel (NTK), demonstrating that a naive extension of the NTK is ill-posed. The authors propose a rigorous generalization of the NTK for SGL, providing a framework for analysis. Numerical results confirm the convergence of SGL with sign activation and finite network widths towards a deterministic kernel, validating the theoretical findings. The exploration of the infinite width limit, through the NTK and SG-NTK, helps understand the inherent challenges and behavior of networks with non-differentiable activation functions. Despite the limitations of SGL, its theoretical grounding offers valuable insights into training biologically inspired neural networks, opening paths for further research and development of robust training algorithms for non-differentiable activation functions.

Future Research#

The paper’s “Future Research” section would ideally delve into several crucial areas. First, a rigorous theoretical analysis of the surrogate gradient neural tangent kernel (SG-NTK) for activation functions with jumps is needed. The current analysis relies on approximation, so extending it to handle the discontinuities directly would strengthen the theoretical foundation. Second, investigating the impact of different surrogate derivatives on the SG-NTK’s properties is important. A systematic exploration of how the choice of surrogate derivative affects the model’s learning dynamics and generalizability is crucial. Third, applying the SG-NTK framework to analyze practical scenarios with real-world datasets would broaden its applicability and provide empirical validation of its analytical predictions. Finally, extending the work beyond the infinite-width limit to finite-width networks is crucial for practical implementation. Bridging the theoretical results from the infinite-width regime to realistic scenarios with limited neurons would significantly enhance the relevance of the SG-NTK for guiding the development of new algorithms for training spiking neural networks. Overall, future research needs to connect theory with practical implementation to demonstrate the SG-NTK’s potential for advancing the field.

More visual insights#

More on figures

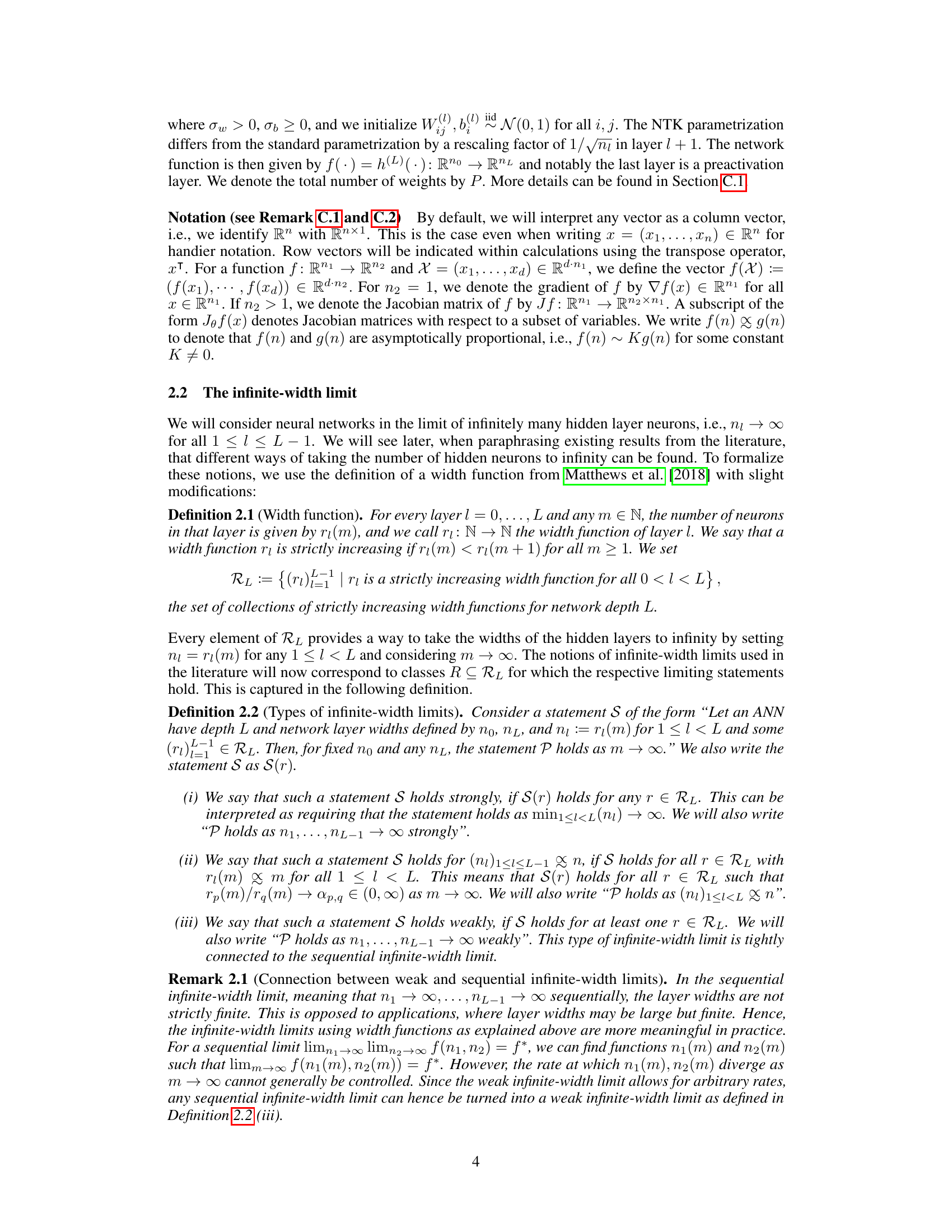

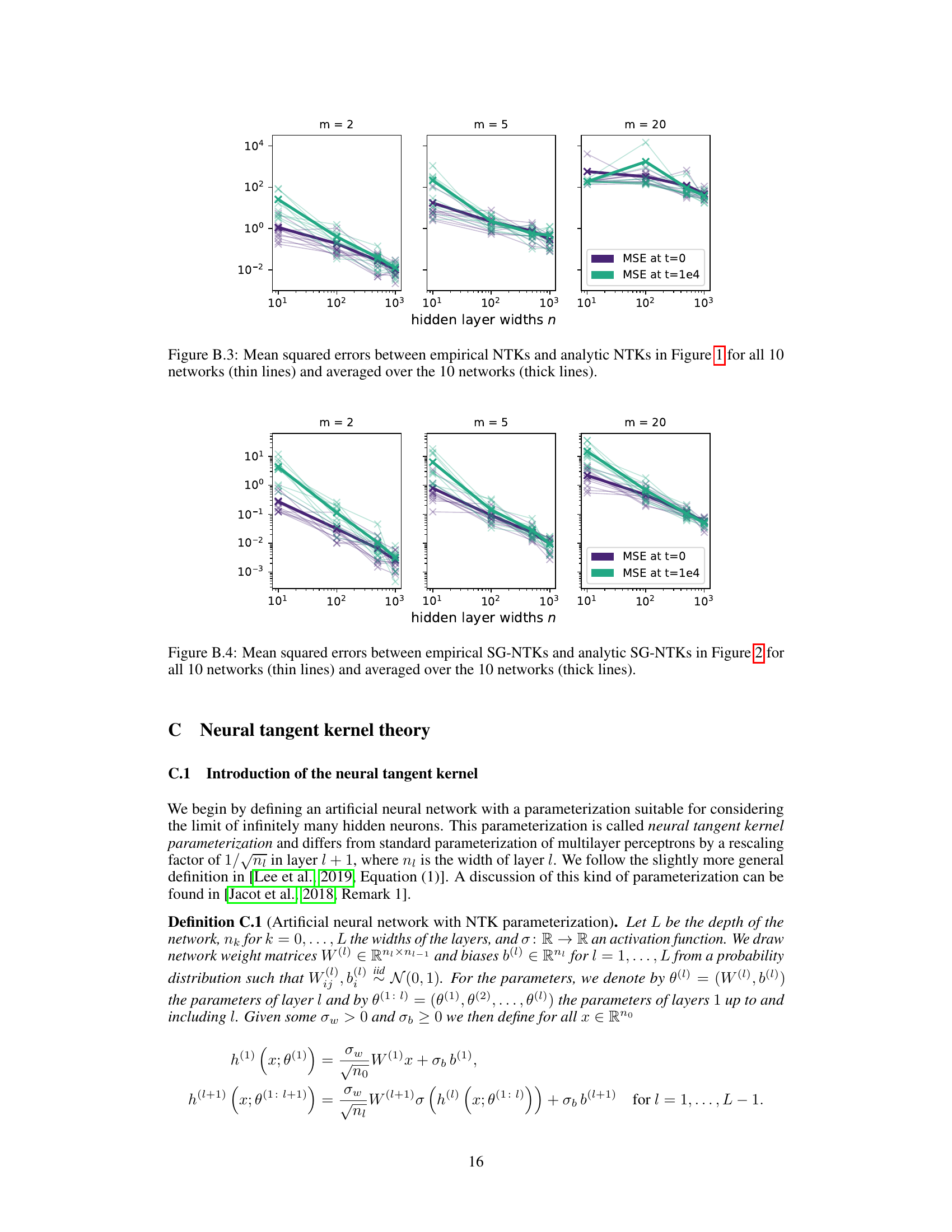

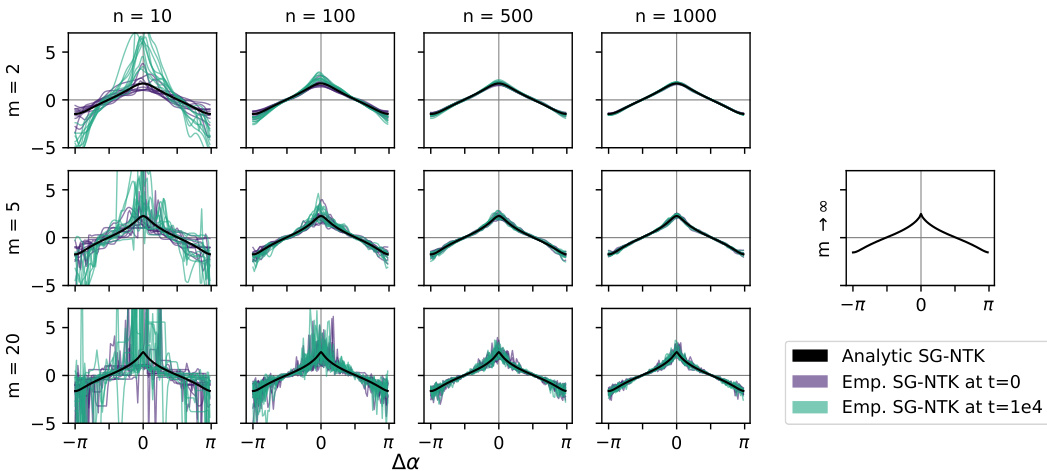

This figure shows the convergence of empirical and analytical surrogate gradient Neural Tangent Kernels (SG-NTKs) in the infinite-width limit. The plots compare empirical SG-NTKs from ten networks with different hidden layer widths (n = 10, 100, 500, 1000) and activation functions erfm (m = 2, 5, 20) to the analytical SG-NTKs at initialization and after gradient-descent training. The y-axis is scaled using the inverse hyperbolic sine function (asinh) for better visualization of the convergence behavior. The results demonstrate that the empirical SG-NTKs converge to the analytical ones as the network width increases, supporting the theoretical findings about the SG-NTK’s convergence.

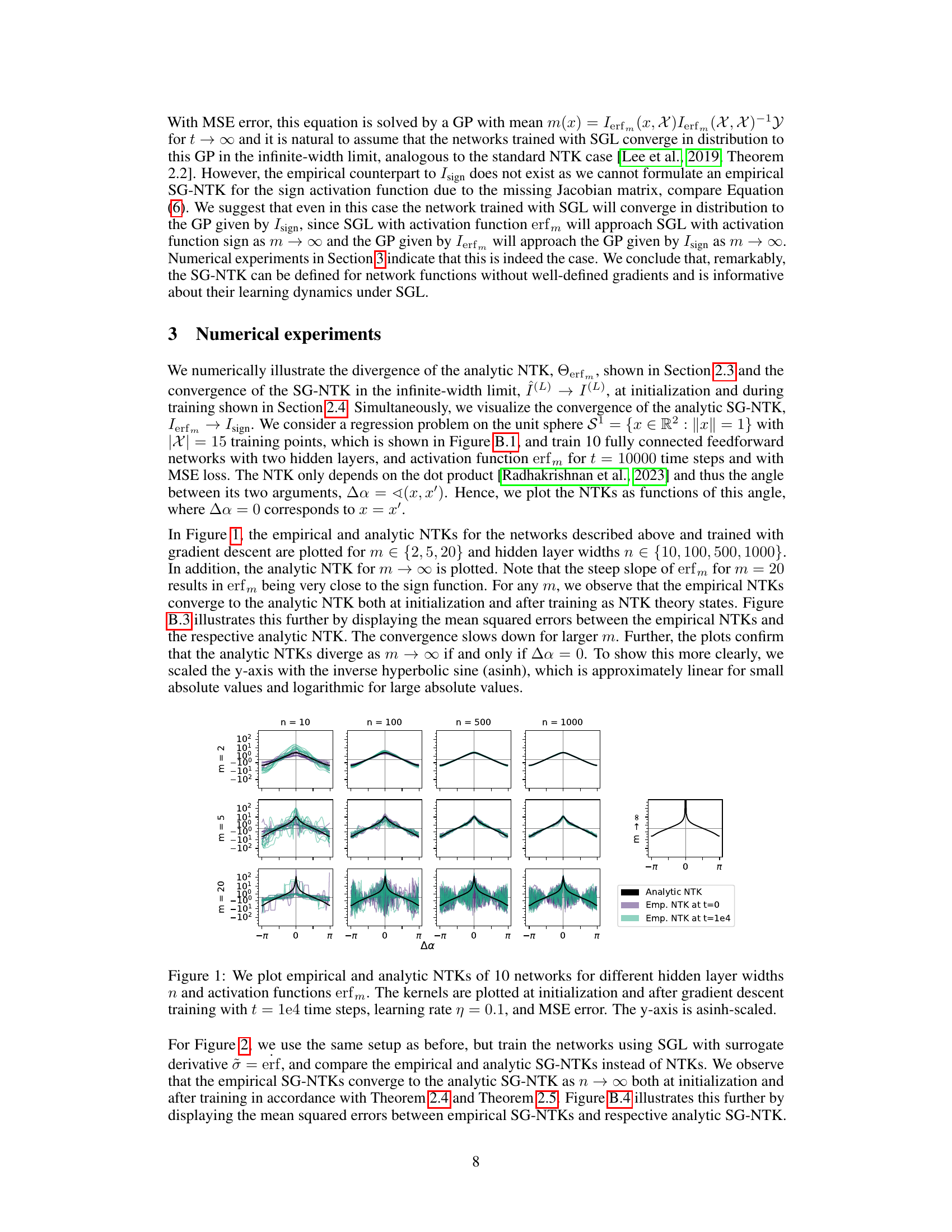

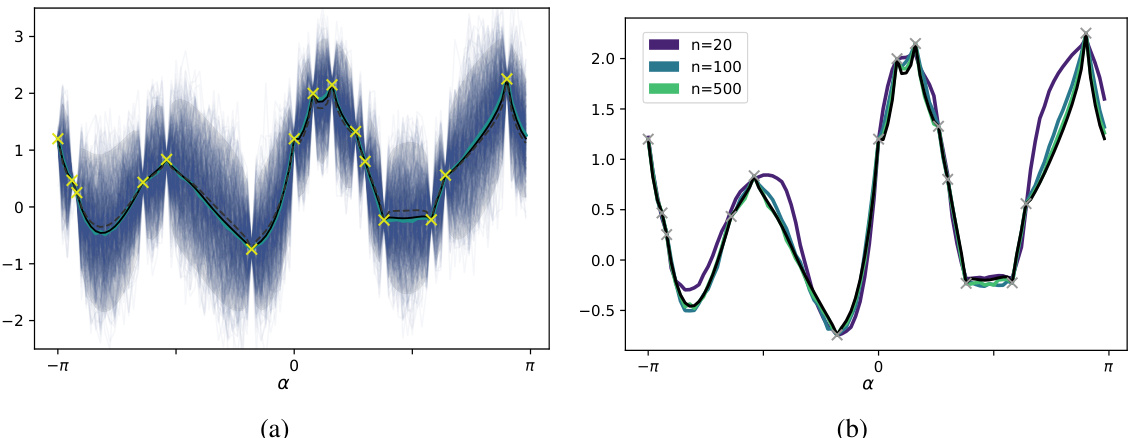

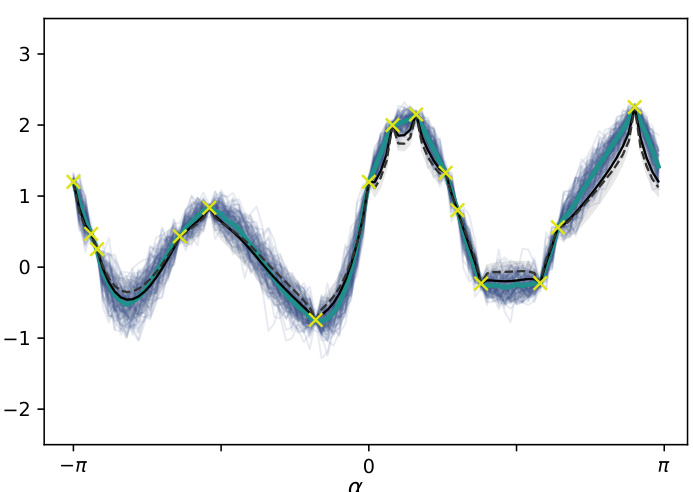

This figure compares the results of surrogate gradient learning (SGL) with the surrogate gradient neural tangent kernel (SG-NTK). Panel (a) shows the results for networks with hidden layer width of 500, comparing the mean network prediction (blue) with the mean and confidence bounds of the Gaussian process prediction (black line and grey area). The mean network predictions using SGL agrees well with the SG-NTK prediction. Panel (b) demonstrates that the agreement between the SG-NTK and the SGL mean prediction is even better with increasing network width (100 and 20).

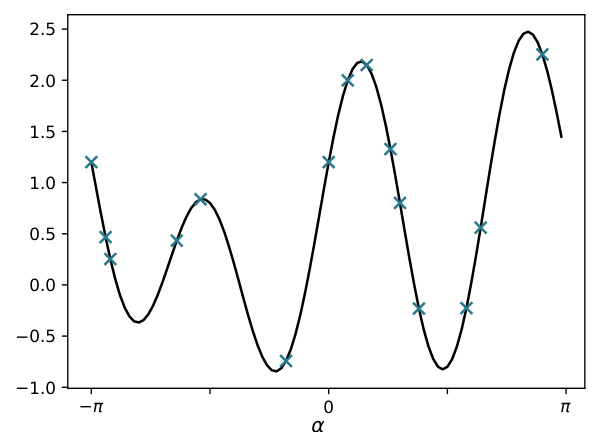

This figure shows the target function used in the numerical experiments of the paper, along with the training data points. The function is a 2D surface plotted against angle α, showing its oscillating, non-linear nature. The training points are superimposed on the curve, illustrating the data points used to train and validate the models.

This figure compares the results of surrogate gradient learning (SGL) with the predictions of the surrogate gradient neural tangent kernel (SG-NTK). Panel (a) shows the distribution of 500 networks trained using SGL, their mean, the SG-NTK Gaussian process (GP) mean and confidence intervals, and the Esign kernel regression. Panel (b) shows the same but for different network widths. The agreement between SGL and SG-NTK indicates that SG-NTK provides a good characterization of SGL.

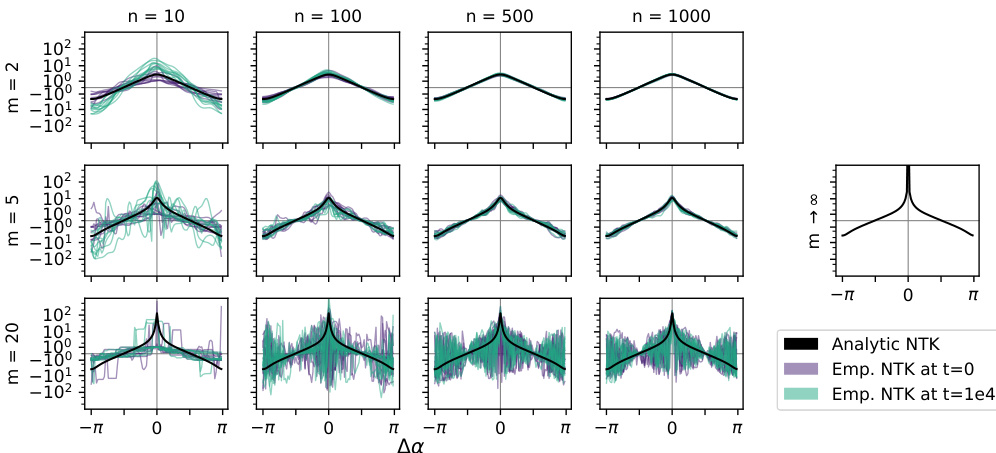

This figure shows the mean squared errors between the empirical and analytical NTKs from Figure 1. The thin lines represent the MSE for each of the 10 individual networks, while the thicker lines show the average MSE across all 10 networks. The plot illustrates the convergence of the empirical NTKs to their analytical counterparts as the hidden layer width (n) increases, for different values of the parameter m (which controls the sharpness of the activation function approximation).

This figure shows the mean squared error between the empirical and analytical NTKs plotted in Figure 1. The thin lines represent the MSE for each of the ten individual networks, while the thick line shows the average MSE across all ten networks. The plot is broken down by the parameter ’m’ (which determines the steepness of the approximation to the sign function) and the hidden layer width ’n’. This visualization helps to demonstrate the convergence of empirical NTKs to their analytical counterparts as the network width increases.

Full paper#