↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Overparametrized neural networks (NNs) often exhibit surprising generalization abilities, especially when leveraging underlying symmetries in the data. This paper addresses the challenge of understanding learning dynamics in such complex systems, particularly when employing symmetry-leveraging (SL) techniques like data augmentation, feature averaging, and equivariant architectures. Existing methods struggle to provide a unified framework or to fully capture the behavior in the large-N limit.

The research utilizes mean-field (MF) theory to analyze the learning dynamics of generalized shallow neural networks in the large-N limit. A novel MF analysis is presented that introduces ‘weakly invariant’ and ‘strongly invariant’ laws on the parameter space, offering a unified interpretation of DA, FA, and EA. This approach reveals that, under specific conditions, DA, FA, and freely-trained models exhibit identical MF dynamics and converge to the same optimum. Crucially, even when freely training, the space of strongly invariant laws is preserved by MF dynamics, a result not observed in finite-N settings.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with overparametrized neural networks and distributional symmetries. It provides a novel mean-field analysis that offers a unified perspective on popular symmetry-leveraging techniques, enhancing our understanding of generalization and optimization in these complex systems. The findings offer valuable insights for designing efficient and effective equivariant architectures and encourage further investigation of MF dynamics under various settings.

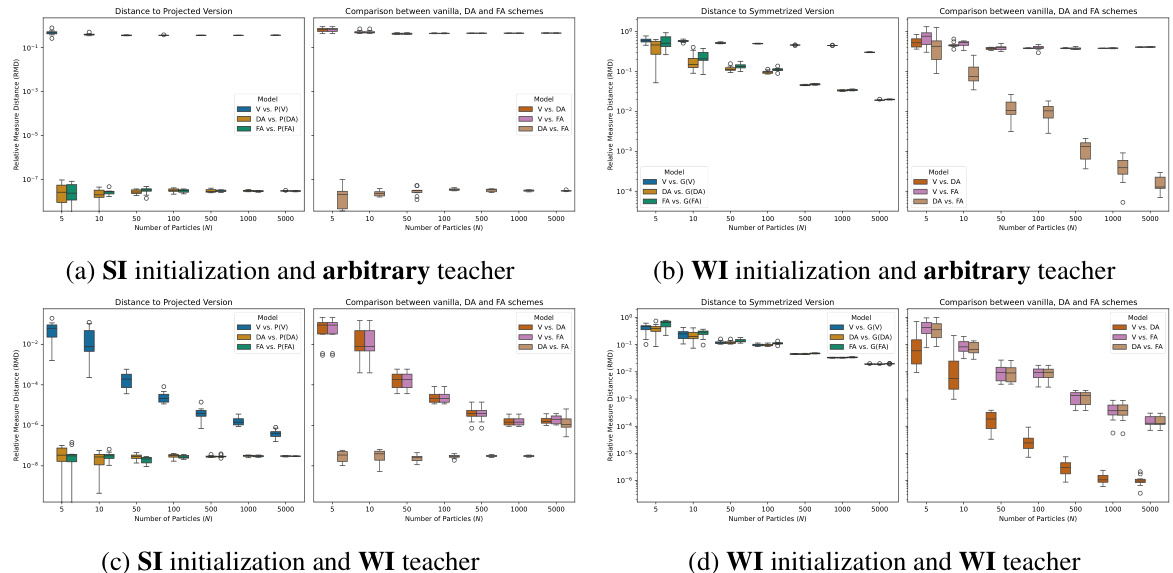

Visual Insights#

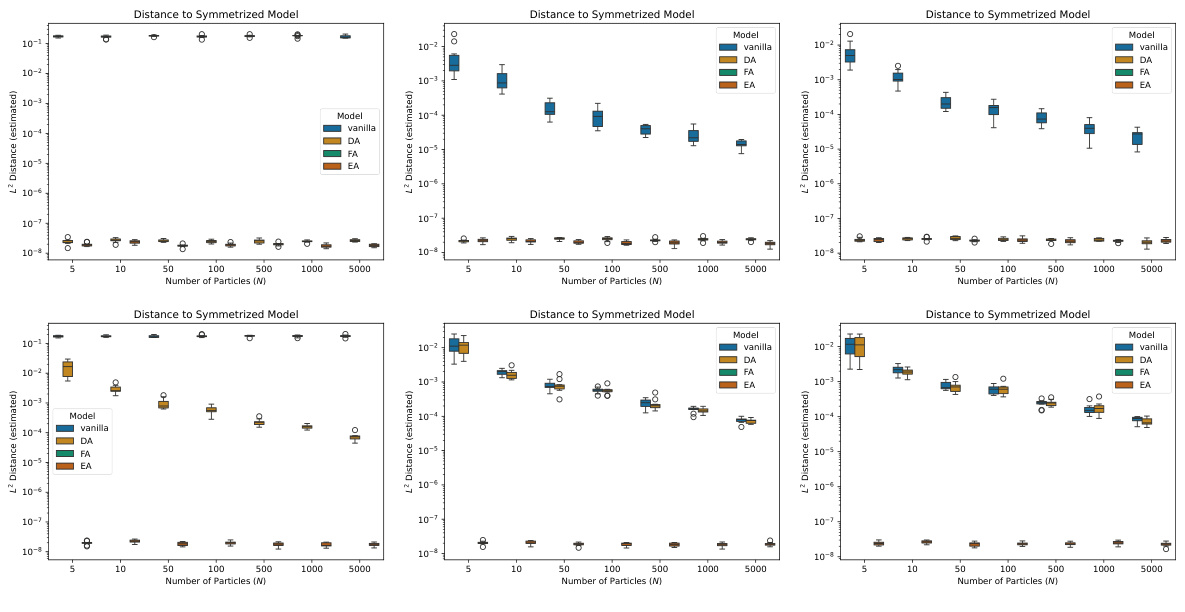

This figure compares the performance of different training schemes (vanilla, data augmentation (DA), feature averaging (FA), and equivariant architectures (EA)) on a shallow neural network model. The training is initialized with strongly invariant (SI) distributions, and three different types of teachers (arbitrary, weakly invariant (WI), and SI) are used. The figure presents the relative measure distance (RMD) between the resulting particle distributions and their symmetrized or projected versions for different numbers of particles (N). It aims to show the effect of symmetry-leveraging techniques in preserving the symmetry of the parameter distribution during training.

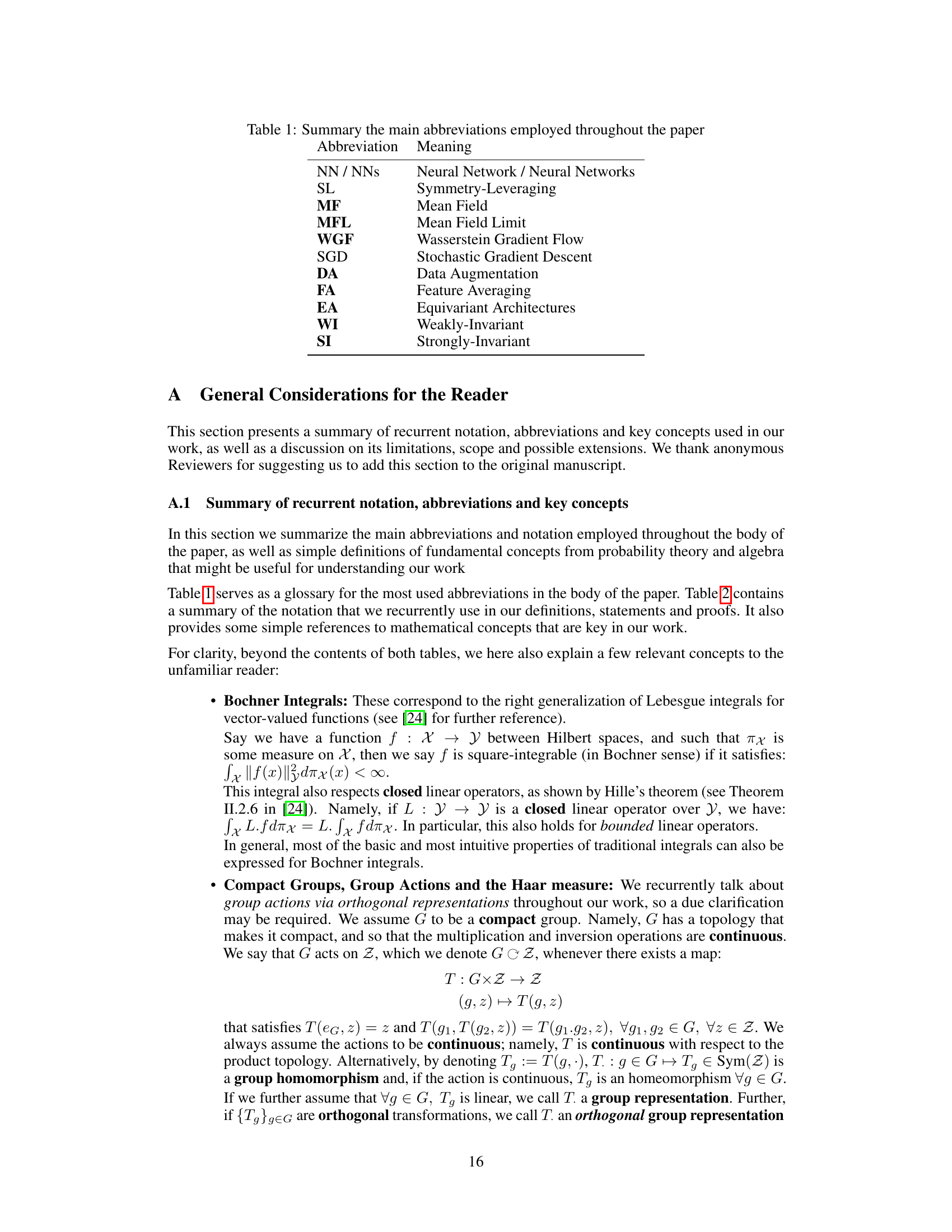

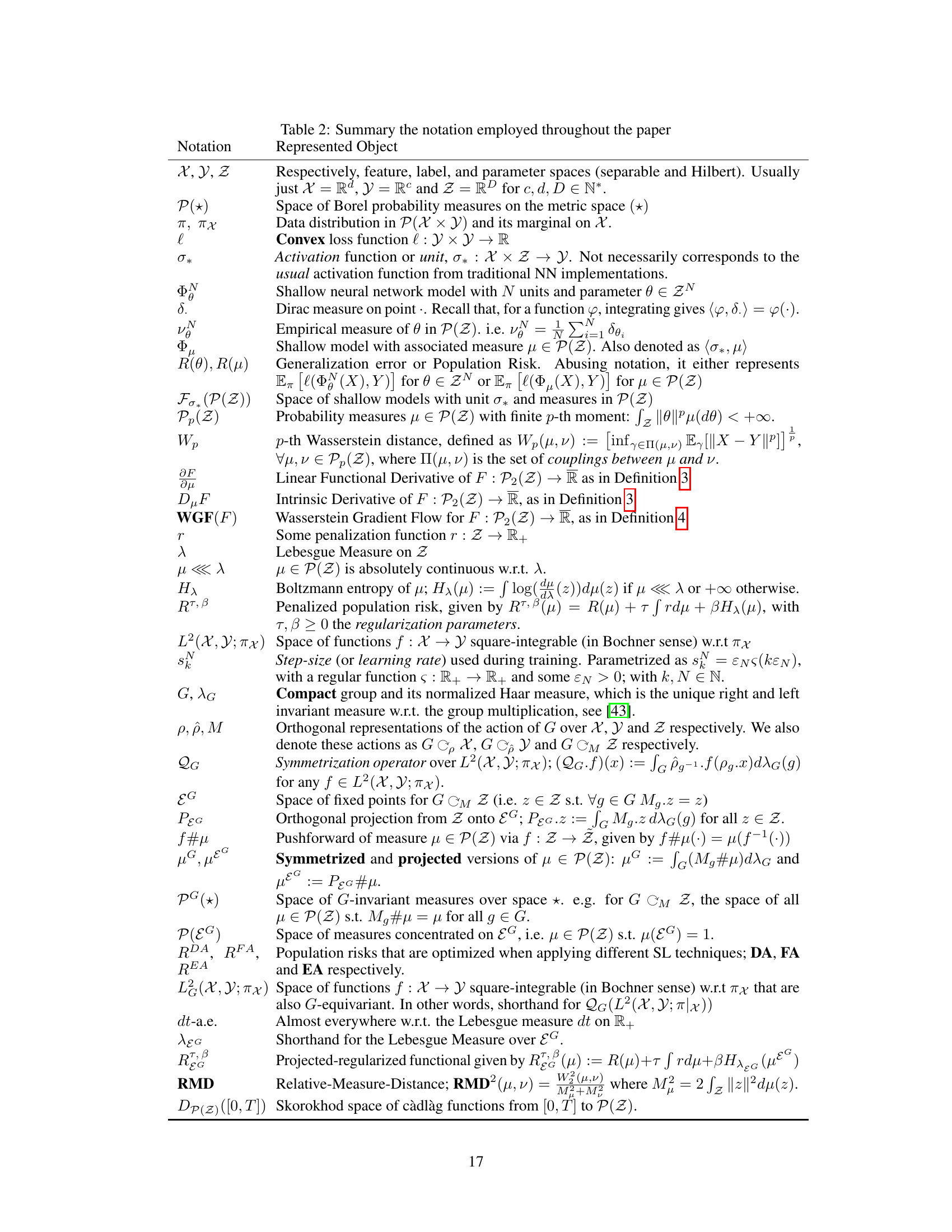

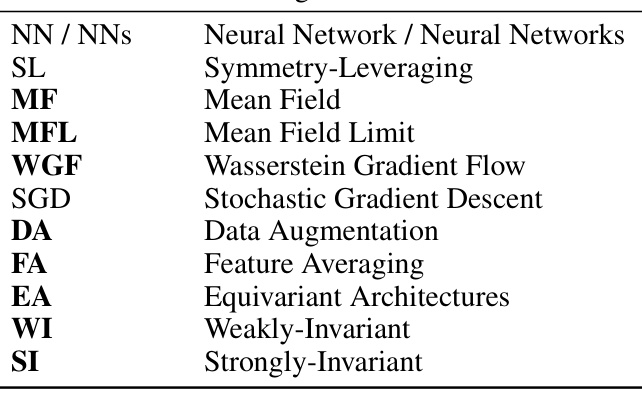

This table lists the abbreviations used throughout the paper and their corresponding meanings. It provides a quick reference for readers unfamiliar with the terminology used in the field of artificial neural networks and machine learning, including terms like Mean Field, Wasserstein Gradient Flow, Stochastic Gradient Descent, Data Augmentation, Feature Averaging, and Equivariant Architectures.

In-depth insights#

MF NN Dynamics#

The heading ‘MF NN Dynamics’ likely refers to the mean-field analysis of neural network training dynamics. This approach simplifies the study of large networks by approximating the behavior of individual neurons using a probability distribution. Key insights gained from this analysis include revealing connections between SGD and Wasserstein gradient flows. The mean-field limit provides theoretical guarantees on convergence and generalizability, often in the context of overparametrized networks, revealing how overparameterization and training dynamics enable generalization. Furthermore, the analysis often explores the effects of data symmetries on the dynamics. Invariance under such symmetries is usually demonstrated via gradient flow evolution. Studying these dynamics allows researchers to understand how learning progresses within the network, offering insights into the effects of different training techniques like Data Augmentation and Equivariant Architectures on model behavior. The analysis can uncover why these techniques prove successful and provides data-driven heuristics for designing more efficient and effective models. Overall, ‘MF NN Dynamics’ likely provides a powerful mathematical framework for understanding and improving neural network training.

Symmetry in MFL#

The mean-field limit (MFL) analysis reveals how distributional symmetries in data impact the learning dynamics of overparameterized neural networks. Symmetric data distributions, relative to a compact group’s action, lead to significant simplifications in the asymptotic dynamics. The study introduces the concepts of weakly invariant (WI) and strongly invariant (SI) laws, representing different levels of symmetry encoding within parameter distributions. WI laws represent G-invariant distributions, while SI laws restrict distributions to lie on the parameters fixed by the group action, representing equivariant architectures. The core finding is that under suitable assumptions (such as using symmetry-leveraging techniques and a convex loss function), the MFL dynamics under data augmentation (DA), feature averaging (FA), and even unconstrained training, all preserve WI laws. Remarkably, even unconstrained training preserves SI laws, contrasting with finite-N settings where equivariance is typically not preserved. This MFL offers a clear mathematical viewpoint on symmetry-leveraging in overparameterized neural networks, providing insights into the effectiveness of various training strategies.

SL Technique Effects#

The effects of symmetry-leveraging (SL) techniques on the learning dynamics of overparametrized neural networks are multifaceted and depend heavily on the interplay between data symmetries, network architecture, and the specific SL method employed. Data Augmentation (DA) increases sample diversity but doesn’t guarantee equivariance, while Feature Averaging (FA) enforces equivariance at the cost of computational efficiency. Equivariant Architectures (EAs) inherently encode symmetries within their structure, offering a more elegant approach but potentially limiting expressiveness. The mean-field analysis reveals that, surprisingly, freely-trained models under symmetric data distributions exhibit behavior remarkably similar to DA and FA in the infinite-width limit. This suggests that implicit symmetries are often captured during training, even without explicit SL techniques. However, the attainability of optimal solutions over the space of strongly invariant laws remains a significant open question, with limitations highlighted in counterexamples. While EAs offer a direct path to achieving equivariance, their constrained parameter space might hinder optimization.

Data-Driven Heuristic#

The proposed data-driven heuristic offers a novel approach to discovering optimal equivariant architectures by iteratively refining a parameter subspace. It leverages the observation that, in the mean-field limit of overparametrized neural networks, freely trained models surprisingly preserve the space of strongly invariant laws under symmetric data distributions. This suggests an iterative process: starting with a trivial subspace, train a model, assess the resulting parameter distribution, and expand the subspace based on where the distribution concentrates. The heuristic’s strength lies in its ability to bypass the computational complexity associated with directly computing the invariant subspace. The method is data-driven, using the training dynamics to guide the subspace expansion. The experimental results demonstrate its effectiveness in discovering larger subspaces, revealing its potential for designing more expressive equivariant architectures with minimal generalization errors. However, further theoretical analysis and broader empirical validation are needed to fully assess its capabilities and limitations across various problems and symmetry groups.

Future Research#

The authors suggest several promising avenues for future research. Extending the mean-field (MF) analysis to deeper, more complex neural network architectures is a crucial next step, as the current work focuses on generalized shallow networks. Relaxing restrictive assumptions, such as the boundedness of the activation function, would broaden the applicability of the theoretical results. Investigating the convergence rates of different training methods (DA, FA, vanilla) to the MF limit, as N grows, is vital for practical applications. Furthermore, a comprehensive empirical evaluation on larger and more complex real-world datasets is needed to further validate the heuristic algorithm proposed for discovering effective equivariant architectures. Finally, exploring the interplay of symmetries and non-Euclidean geometries promises to enrich this work.

More visual insights#

More on figures

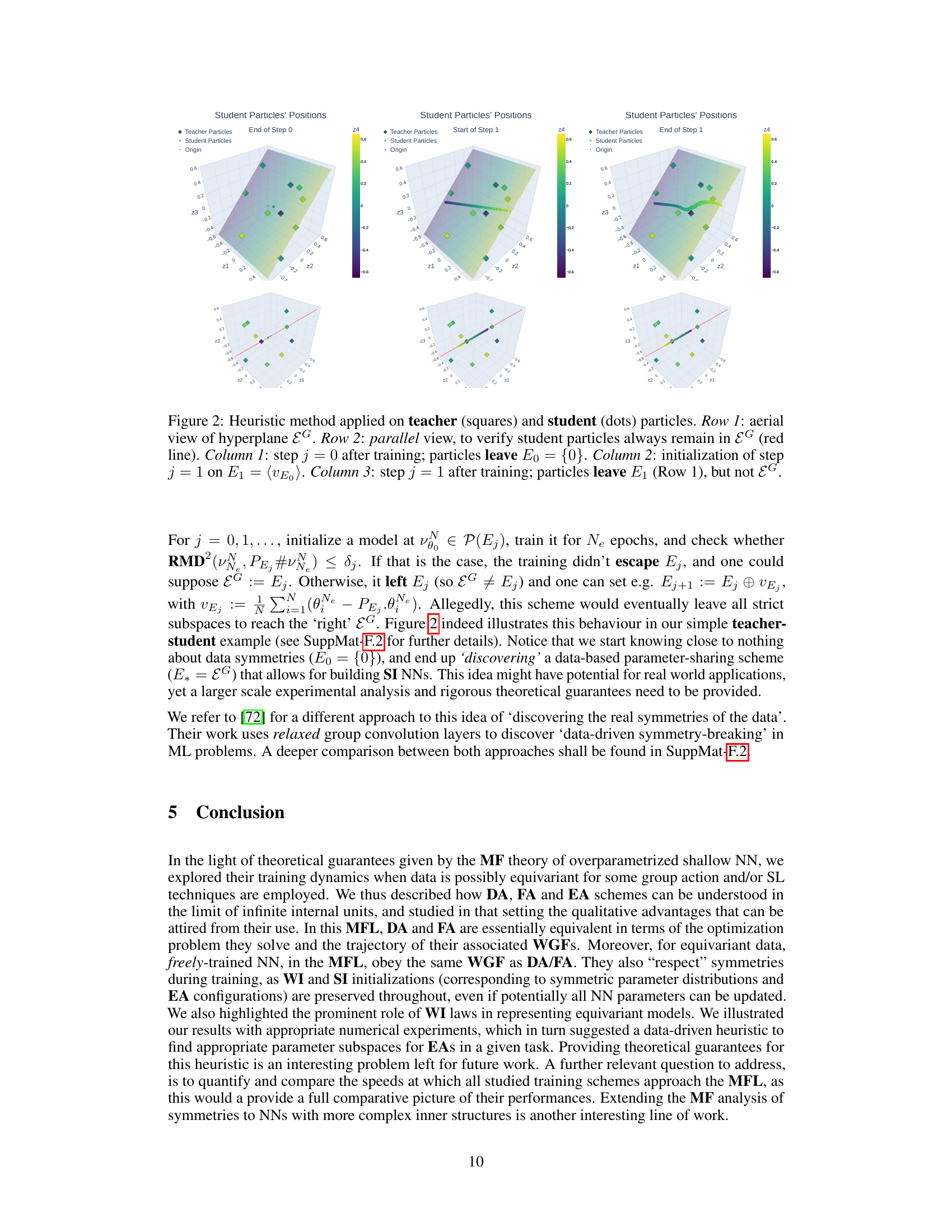

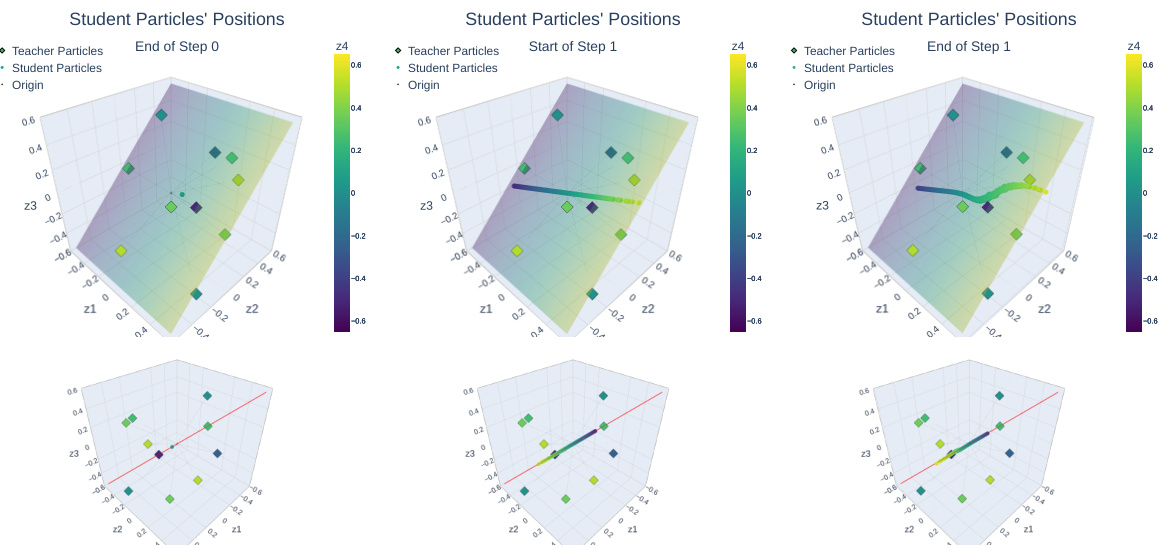

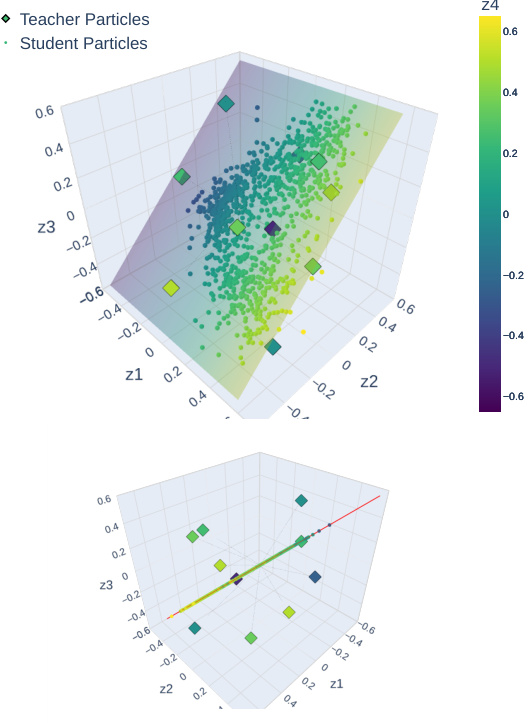

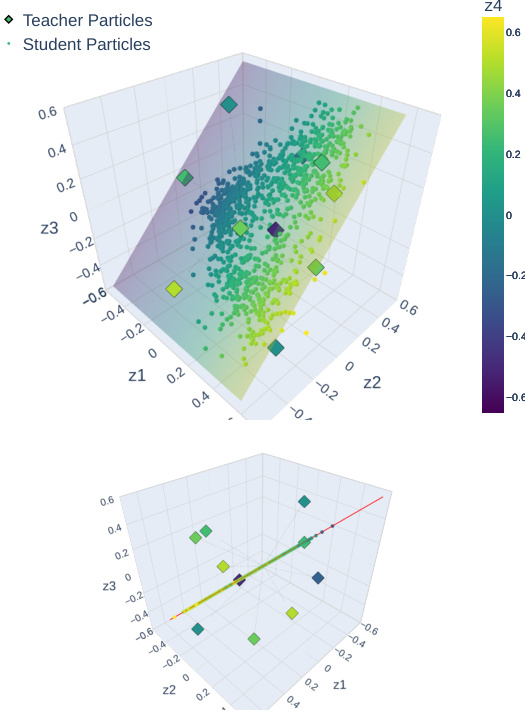

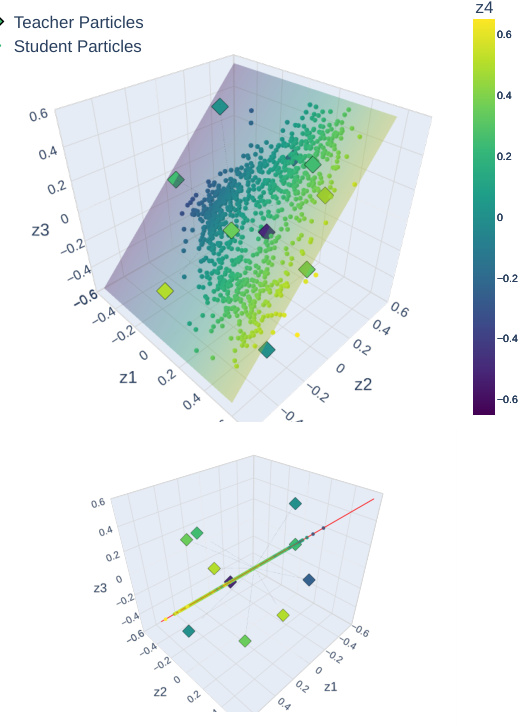

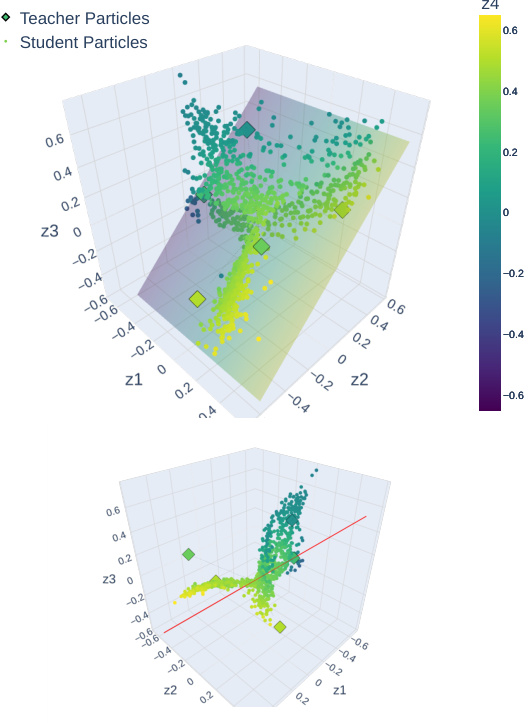

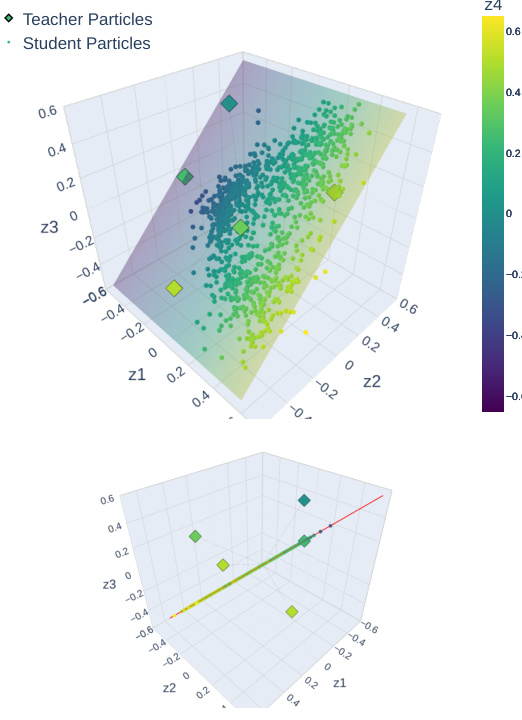

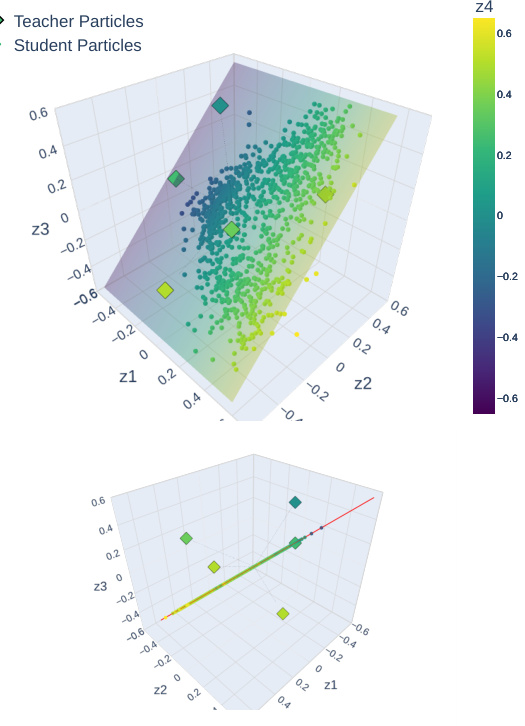

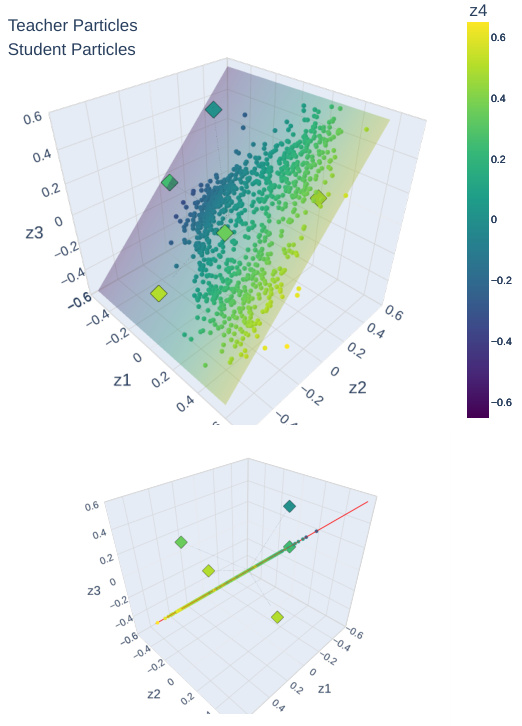

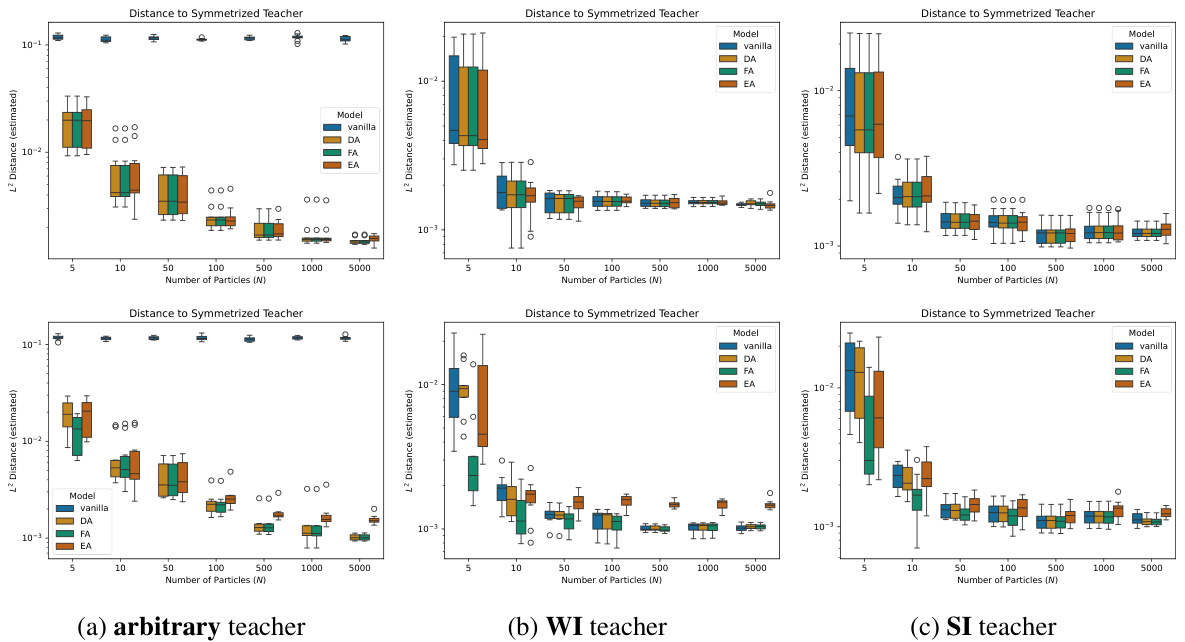

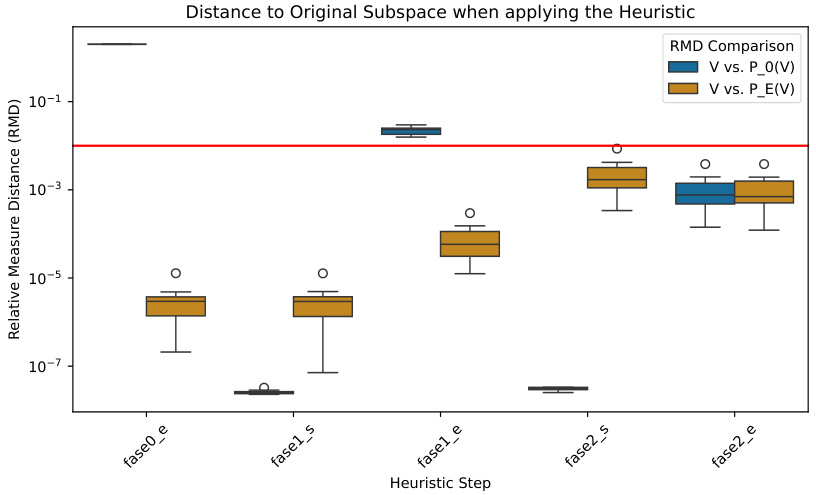

This figure shows the application of the heuristic algorithm to discover the largest subspace of parameters supporting SI distributions. The algorithm iteratively trains a student neural network with parameters initialized in a subspace, and checks if the parameters remain within the subspace after training. If they do, the subspace is considered a potential EA parameter space. The figure shows the results for three iterations of the algorithm. The first column shows that the parameters escape from the trivial subspace. The second column shows the next iteration, and the third shows that the parameters do not escape the final subspace, which could be the best one.

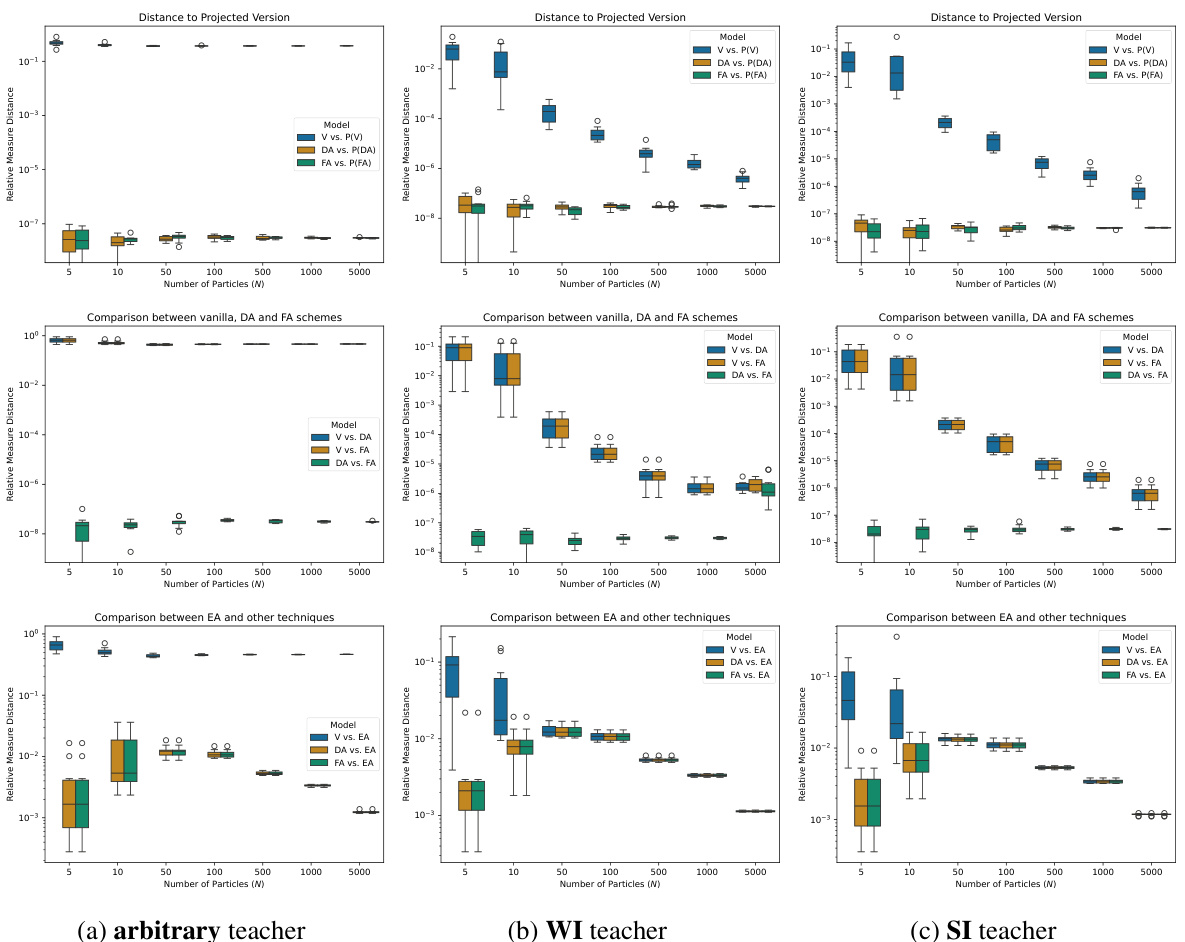

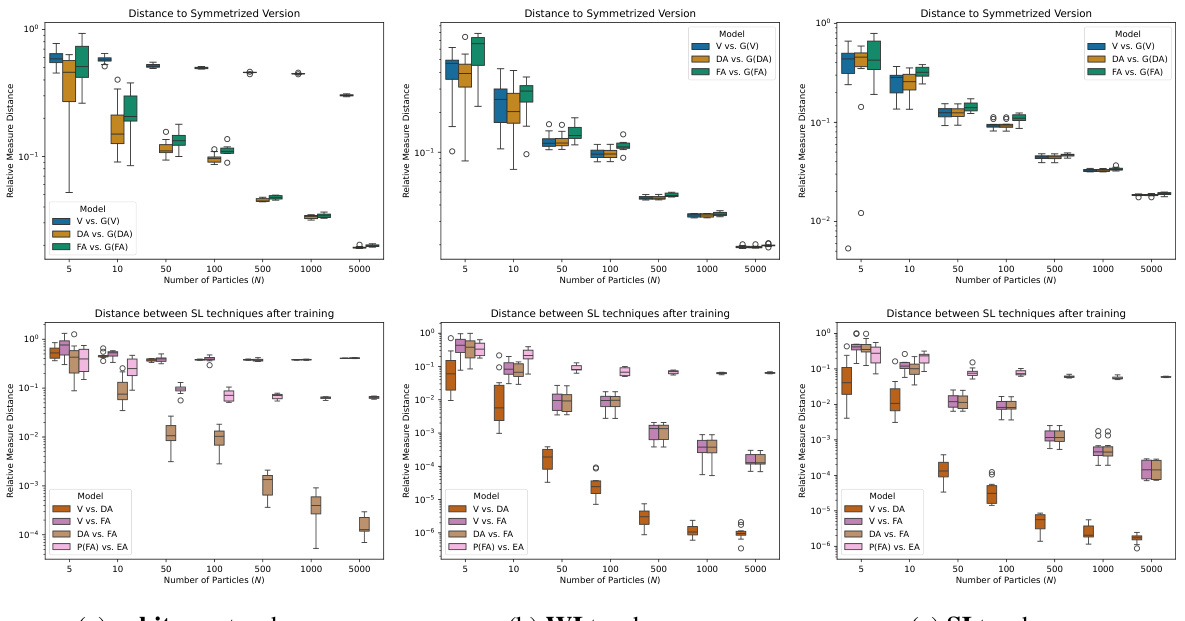

This figure shows the results of multiple experiments with different numbers of particles (N) and training schemes (vanilla, DA, FA, EA). The goal is to assess the impact of each training method on the distribution of learned parameters, particularly whether the distribution remains within the equivariant subspace EG. The figure displays the Relative Measure Distance (RMD) between the final distributions obtained by each method, helping to quantify their similarity. The different columns represent different teacher models (arbitrary, WI, SI).

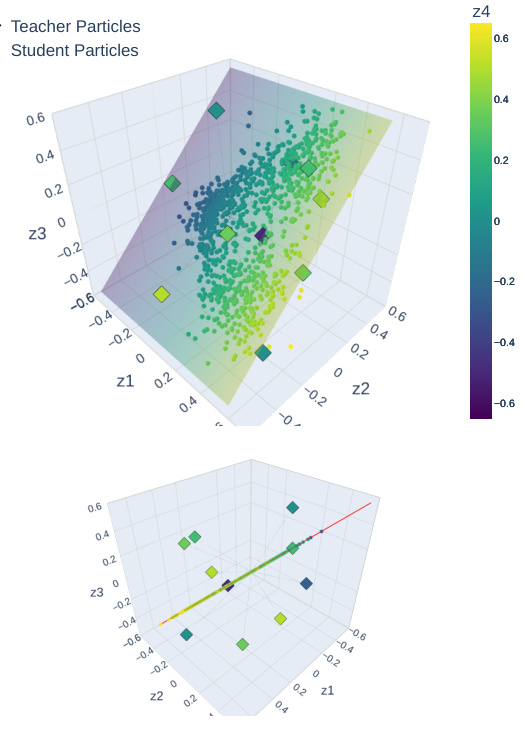

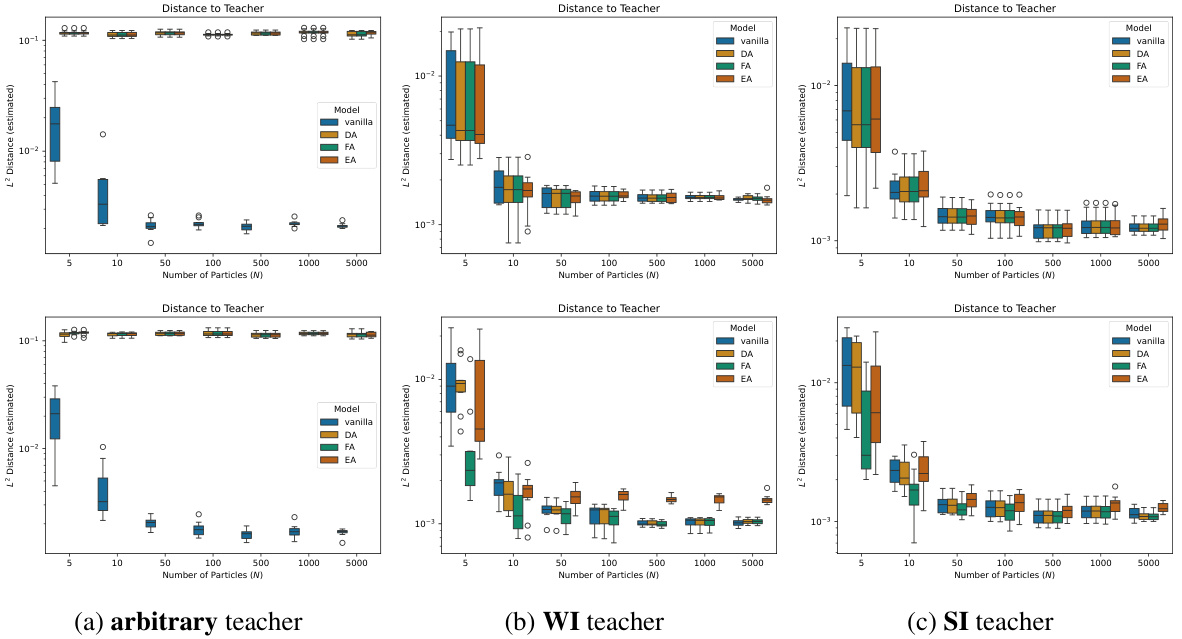

This figure visualizes the final positions of student NN particles after training with different symmetry-leveraging (SL) techniques: vanilla, data augmentation (DA), feature averaging (FA), and equivariant architectures (EA). The teacher particles are WI (weakly invariant). The student particles are initialized to be SI (strongly invariant) and the hyperplane represents EG (subspace of invariant parameters). The figure shows that the SI-initialized training with vanilla scheme stays within EG, while DA, FA, and EA schemes also stay within EG and converge toward teacher particles as the number of particles N increases.

This figure visualizes the heuristic algorithm proposed in the paper for discovering the largest subspace of parameters that support strongly invariant distributions. The algorithm iteratively trains a neural network, starting from a subspace (E0) and checking if the training remains within that subspace or escapes. If it escapes, a new subspace (Ej+1) is constructed, extending the previous subspace until a subspace is found (EG) within which training consistently remains after the training iterations, despite its not being enforced explicitly. The figure shows this progression over three steps (j=0,1,2). The teacher particles (squares) are fixed, and the goal is to discover the parameters supporting SI distributions.

This figure visualizes the heuristic algorithm proposed in the paper for discovering the largest subspace of parameters supporting strongly invariant (SI) distributions. It shows the evolution of student particles during training (dots), compared to teacher particles (squares), across three steps (columns). Each step involves training on a larger subspace, iteratively building towards the target subspace EG. The top row provides an aerial view, while the bottom row offers a side view to emphasize that student particles remain within the subspace EG (red line), even after leaving the initial subspaces.

This figure visualizes the positions of the neural network (NN) particles after training using four different methods: vanilla, data augmentation (DA), feature averaging (FA), and equivariant architectures (EA). The teacher particles, represented as squares, have a weakly invariant (WI) distribution. Student particles, shown as dots, were initialized with a strongly invariant (SI) distribution. The plots illustrate the particle distributions for each training method, showing both an aerial view and a side view parallel to the EG hyperplane. The side views provide a clearer illustration of how close the particle distributions are to EG.

This figure visualizes the positions of student and teacher particles in a 4D parameter space after training with four different methods: vanilla, DA, FA, and EA. The training used an SI initialization and a WI teacher. The top row shows a 3D projection of the 4D parameter space and the bottom row shows a 2D projection emphasizing the hyperplane representing the SI parameter subspace. The figure demonstrates how the different methods result in different particle distributions, with the vanilla method resulting in particles spread out more than the other methods which leverage symmetry.

This figure visualizes the heuristic algorithm for discovering the largest subspace of parameters supporting SI distributions. It shows the positions of teacher and student particles during the algorithm’s iterations. The red line indicates when the student particles escape the subspace. The results suggest that the algorithm can successfully discover the largest subspace.

This figure visualizes the heuristic algorithm for discovering EA parameter spaces. It shows the positions of teacher and student particles in a 3D parameter space (Z) during an iterative process. The algorithm aims to find the largest subspace (EG) of Z that supports strongly-invariant (SI) distributions. The figure shows three steps (columns) of the process. In each step, the student particles are trained (using a specific technique) and their positions are plotted. The red line in the bottom row indicates the subspace (EG) being sought. The figure demonstrates that the algorithm successfully discovers EG, even though the student particles initially move outside of the desired subspace during training.

This figure shows the visualization of the particle distribution of student networks trained using different methods (vanilla, DA, FA, EA). The teacher network has WI particles. The student networks were initialized with SI particles and trained using equation (5), applying the corresponding SL techniques. The figure shows both an aerial view of the particle distribution and a side view showing the projection onto the EG hyperplane. This visualization helps to understand how the different methods affect the learning process and how they approximate the teacher particle distribution.

This figure shows the results of comparing different training methods (vanilla, DA, FA, EA) for different numbers of particles (N) in a teacher-student setting, where the student is initialized with strongly invariant (SI) particles. The three columns represent different teacher models: arbitrary, weakly invariant (WI), and strongly invariant (SI). Row 1 shows how close the final student particle distribution remains to the subspace EG (the subspace of parameters defining equivariant architectures) for each training method. Rows 2 and 3 show pairwise comparisons of the relative measure distances (RMD) between training methods.

This figure displays the results of several experiments that compare different training schemes for neural networks. The training schemes used are vanilla (no symmetry-leveraging), data augmentation (DA), feature averaging (FA), and equivariant architectures (EA). The experiments are run with different numbers of particles (N) and three types of teacher models (arbitrary, weakly invariant (WI), and strongly invariant (SI)). The figure shows three key metrics: the relative measure distance (RMD) to the projected version of the distribution, the RMD between the different training schemes, and the RMD of each scheme versus the EA scheme. The purpose is to evaluate the behavior of different symmetry-leveraging techniques under various conditions and assess their impact on the resulting model.

This figure shows the comparison of the performance of different training methods (vanilla, DA, FA, and EA) on the task of learning a teacher model under varying conditions (arbitrary, WI, and SI teacher models). The results are presented in terms of RMD which measures the distance between the learned model’s parameters and their projected/symmetrized versions in the parameter space EG (i.e. how close the model’s parameters are to exhibiting the desired symmetries). The top row shows the RMD between the learned model and its projected version, indicating how well the model learned to respect the symmetry. The bottom two rows compares RMD between different training techniques, showing how different methods evolve the model towards satisfying the symmetries of the teacher model.

This figure displays the results of several experiments that compare different training schemes of a shallow neural network. The goal is to compare vanilla training, with data augmentation (DA), feature averaging (FA), and equivariant architectures (EA). Three different teacher models are used: an arbitrary teacher, a weakly invariant (WI) teacher, and a strongly invariant (SI) teacher. The training starts from a strongly invariant initialization. The figure shows the relative measure distance (RMD) between the final student distribution and its projected version, which indicates how well the training remained within the invariant subspace EG. It also shows the RMD between the different training schemes and against EA. The experiments are performed for various numbers of particles N (5, 10, 50, 100, 500, 1000, 5000).

This figure shows the results of applying the proposed heuristic algorithm for discovering EA parameter spaces. It compares the relative measure distance (RMD) between the empirical distribution of student particles (v) and its projection onto the subspace Ej (PEj#v), as well as its symmetrized version ((v)G). The red line represents a threshold (dj) for deciding if the training remained in Ej. The figure shows that for the first two steps of the heuristic, the distribution left the original subspace, while for the third step it remained within the subspace. This supports the heuristic’s ability to discover EA parameter spaces.

Full paper#