↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current climate model validation methods, like RMSE, often fail to capture the complexities of spatial climate data. They primarily focus on comparing long-term averages, overlooking important regional variations and distributional differences. This can lead to inaccurate assessments of model performance and hinder our ability to understand climate dynamics accurately. The limitations of existing methods necessitate the development of more sophisticated techniques for climate model validation.

This paper proposes a new method called Spherical Convolutional Wasserstein Distance (SCWD) to address these limitations. SCWD leverages the power of convolutional projections to account for spatial variability and the Wasserstein distance to compare probability distributions, providing a more comprehensive assessment of model accuracy. The study applies SCWD to CMIP5 and CMIP6 model outputs and finds that CMIP6 models show some improvement in reproducing realistic climatologies. The spatial breakdown of SCWD further reveals geographical regions where models significantly differ from observational data.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel method for evaluating climate models, which is crucial for improving the accuracy of climate predictions. SCWD offers a more comprehensive evaluation than existing methods by accounting for spatial variability and local distributional differences. This research opens new avenues for improving climate models and enhancing our understanding of the Earth’s climate system.

Visual Insights#

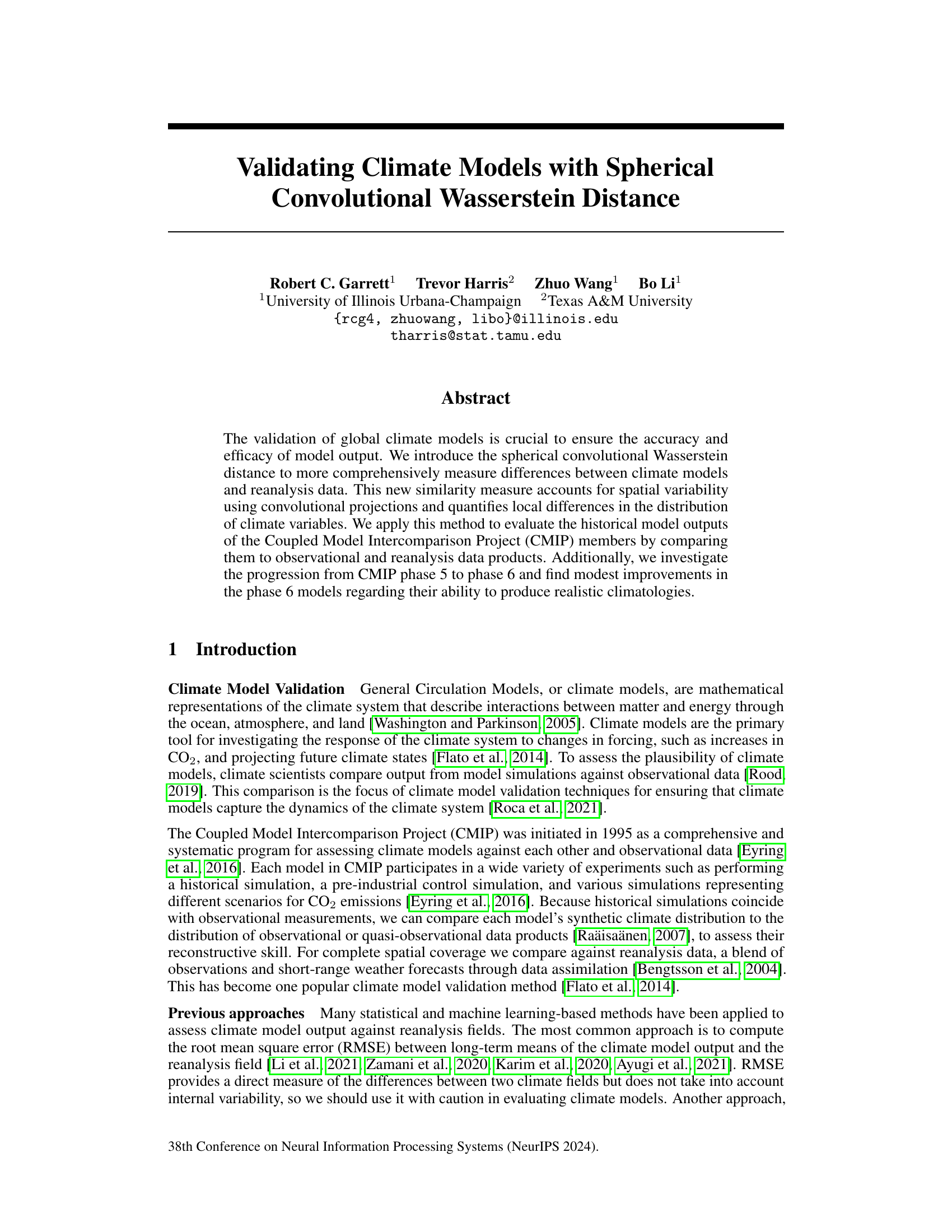

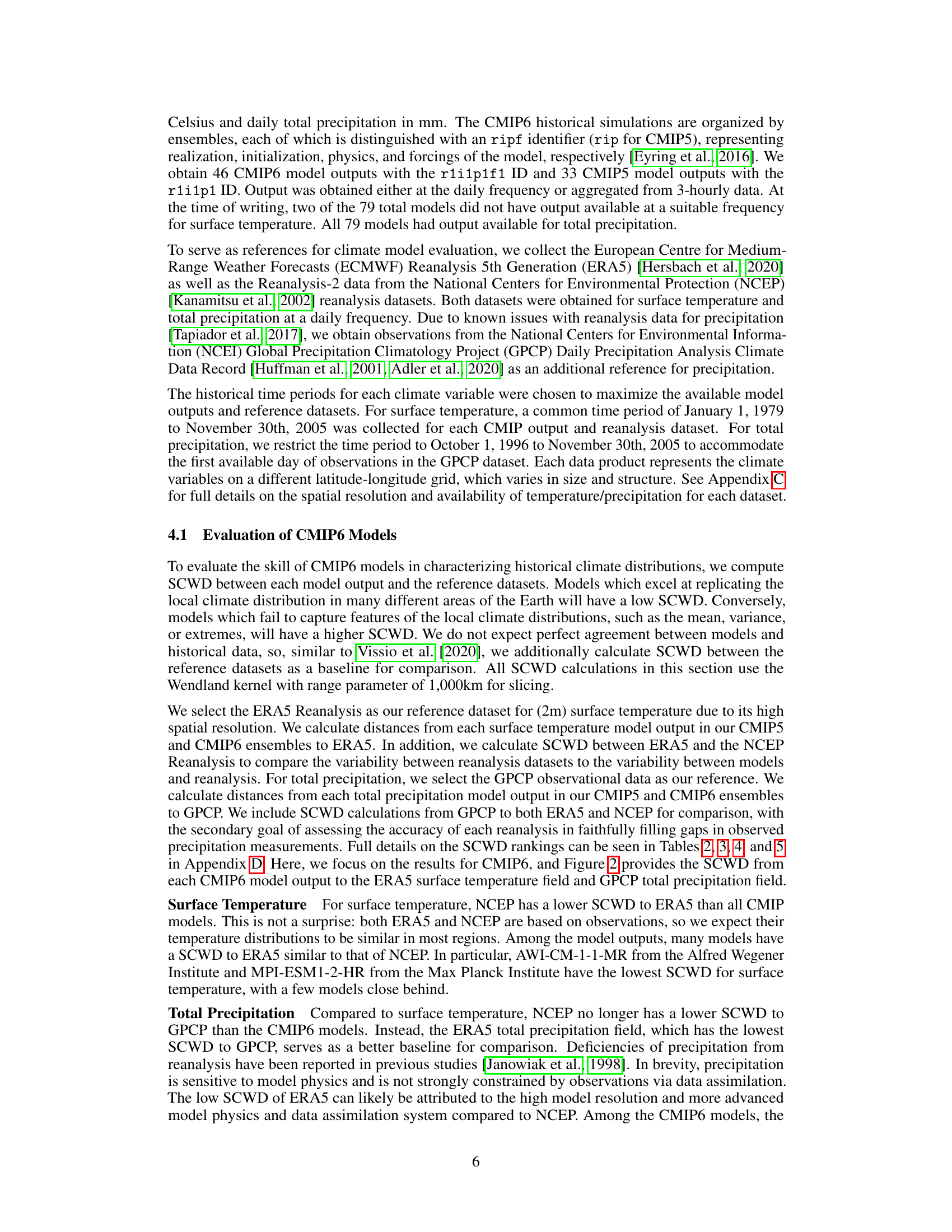

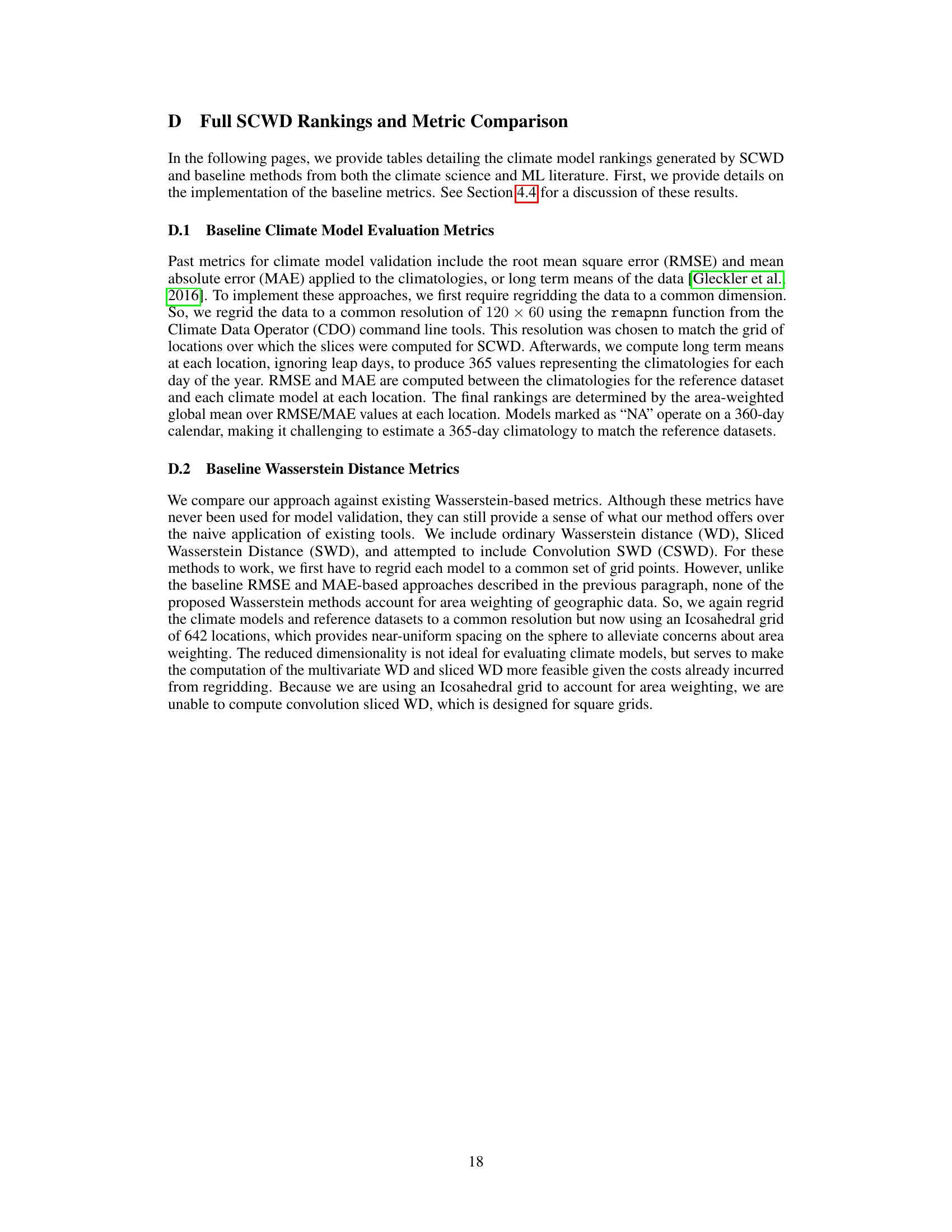

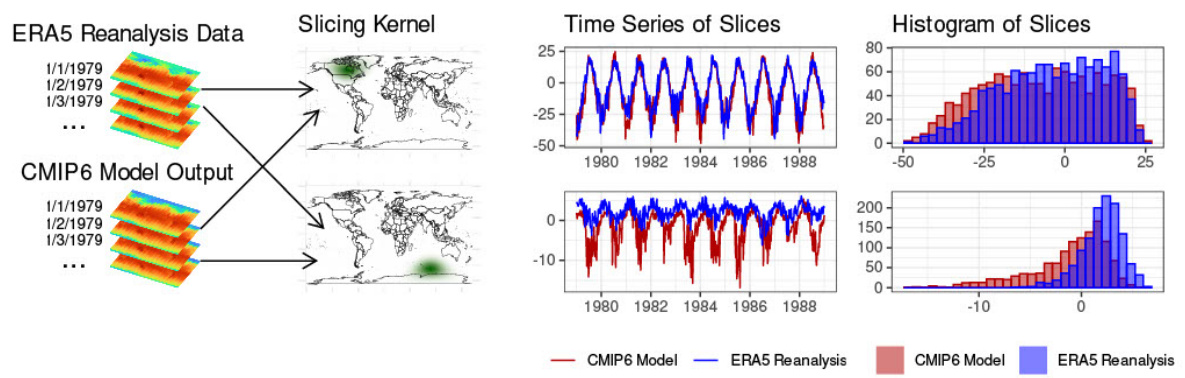

This figure illustrates the computation of the Spherical Convolutional Wasserstein Distance (SCWD) between ERA5 reanalysis data and CMIP6 model output for daily mean surface temperature. It shows how kernel convolutions create ‘slices’ of the data at specific locations, summarizing local climate conditions. Histograms of these slices show the marginal distributions at those locations. Finally, the SCWD is calculated as the global average of the 1-dimensional Wasserstein distances between corresponding slices.

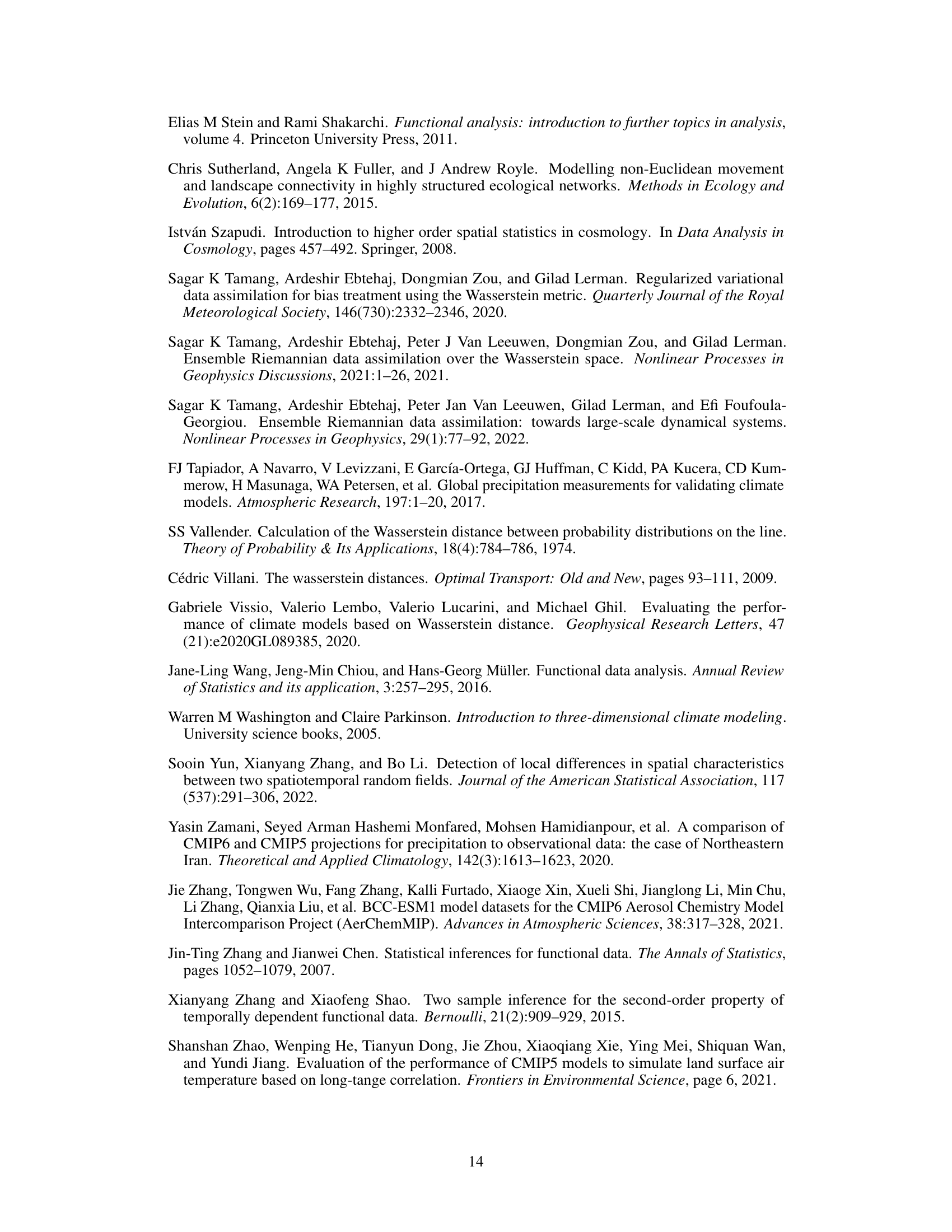

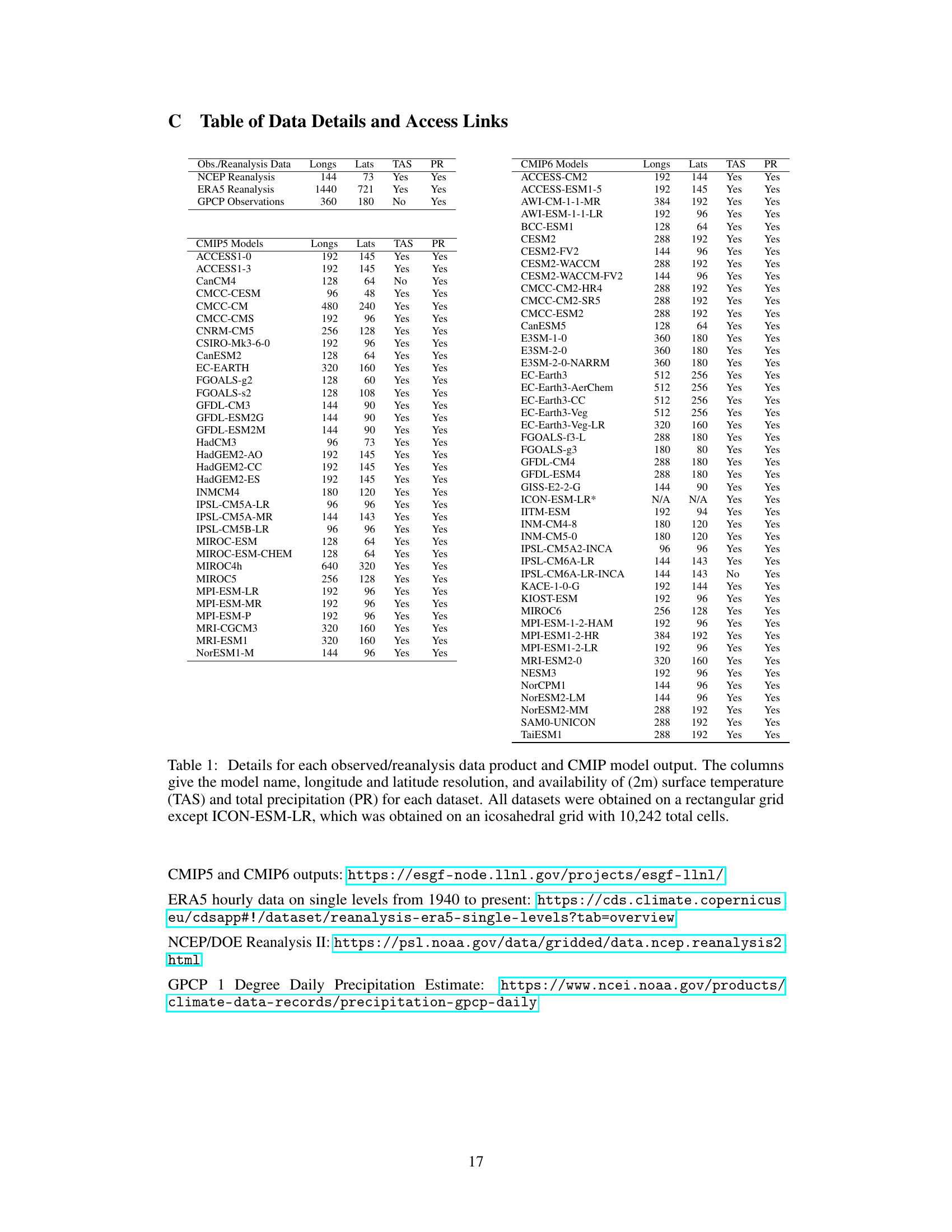

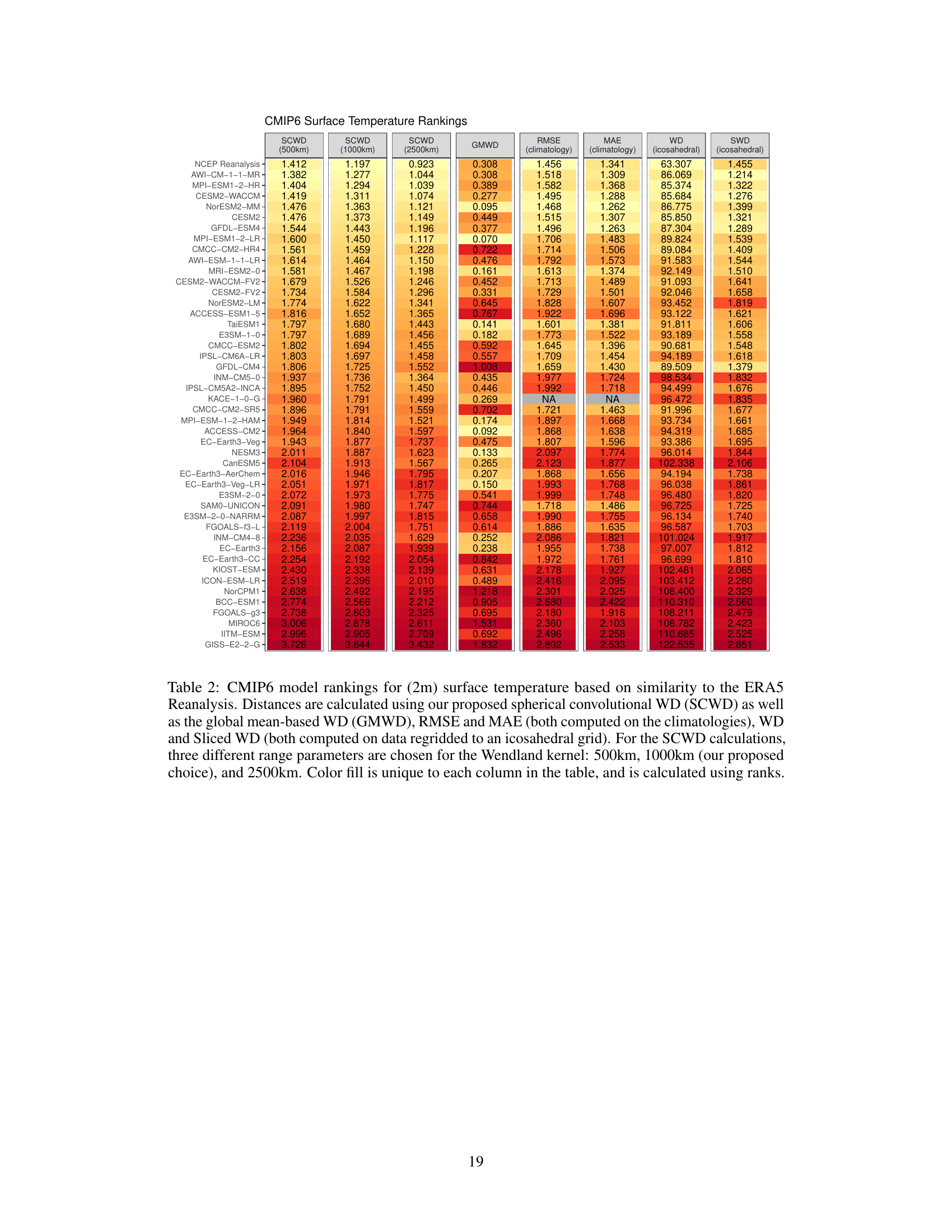

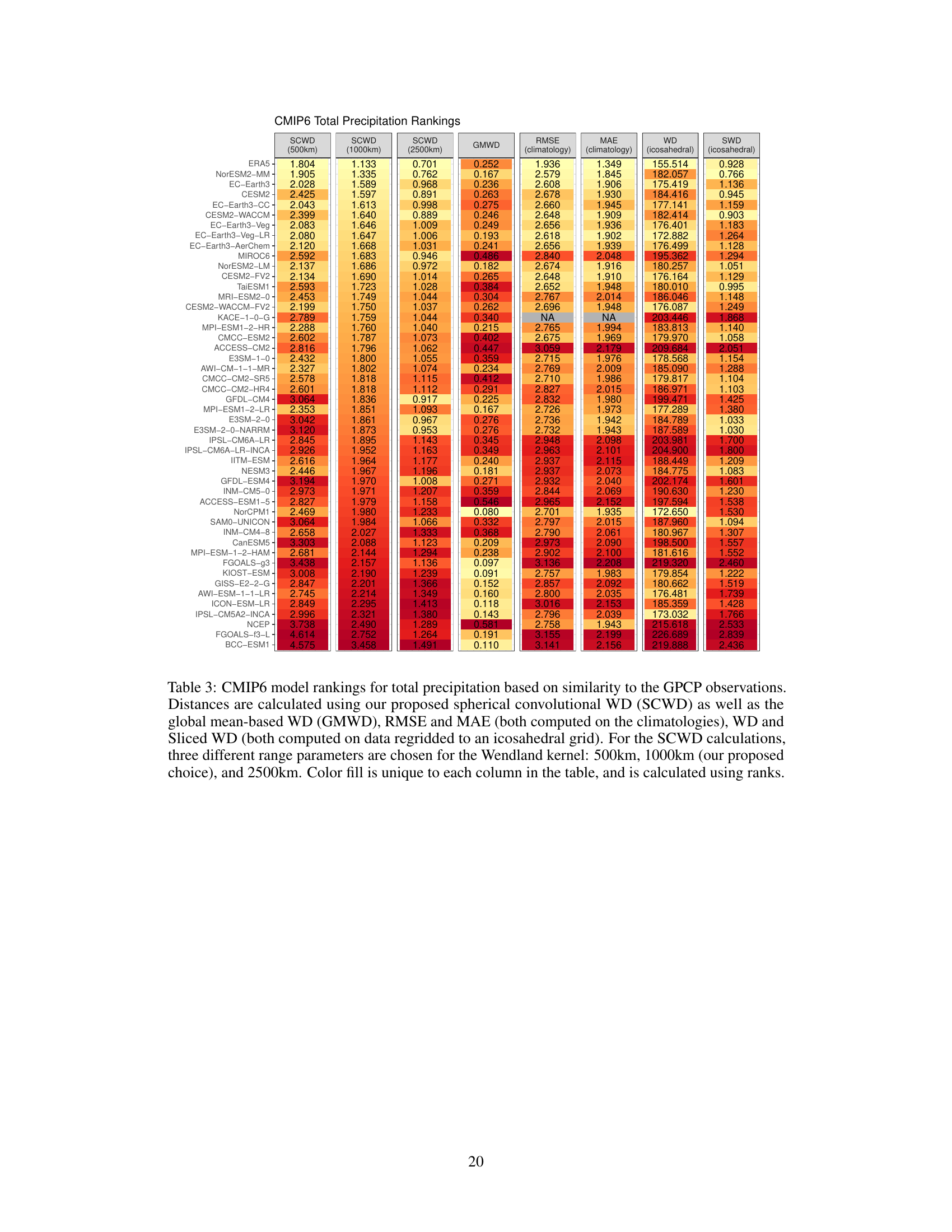

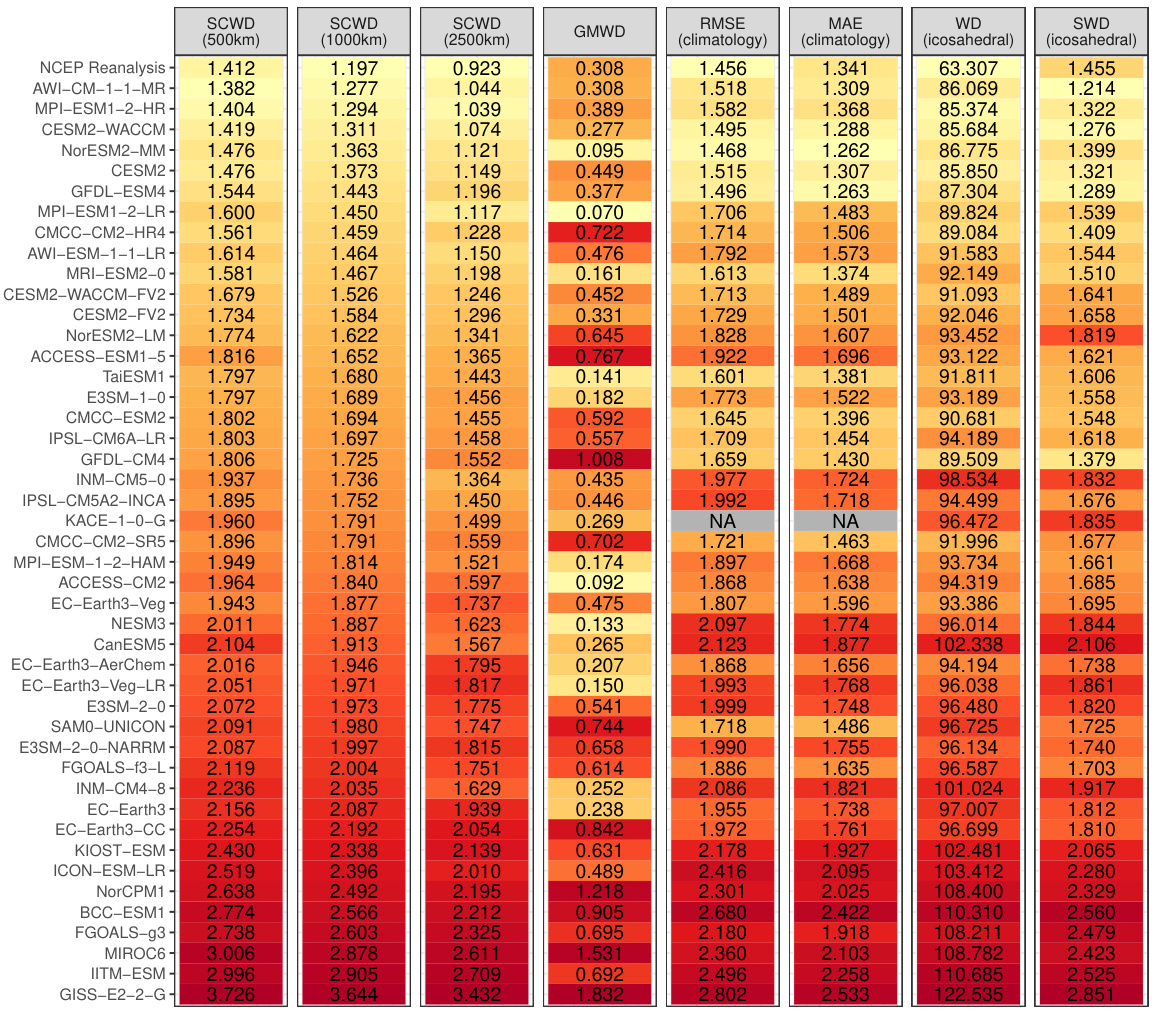

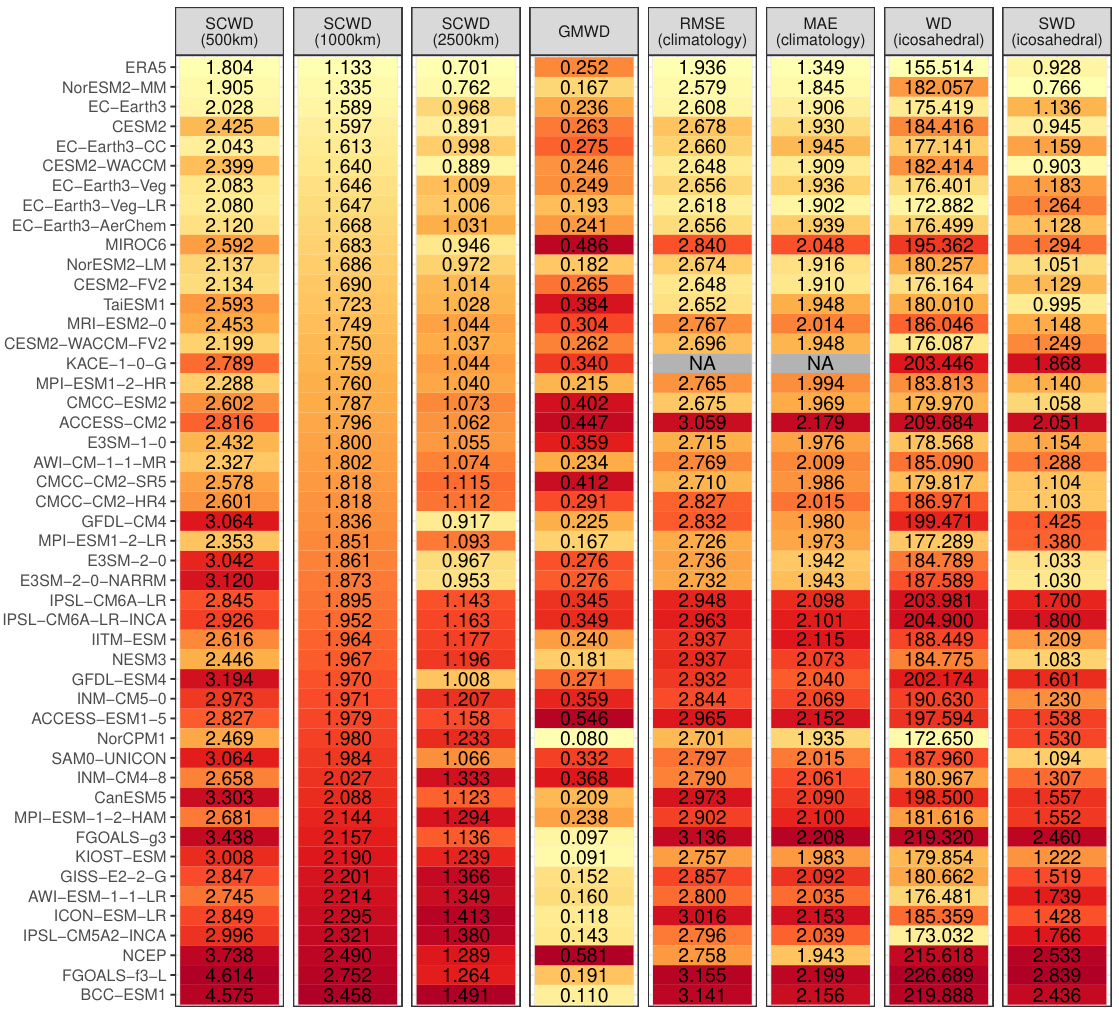

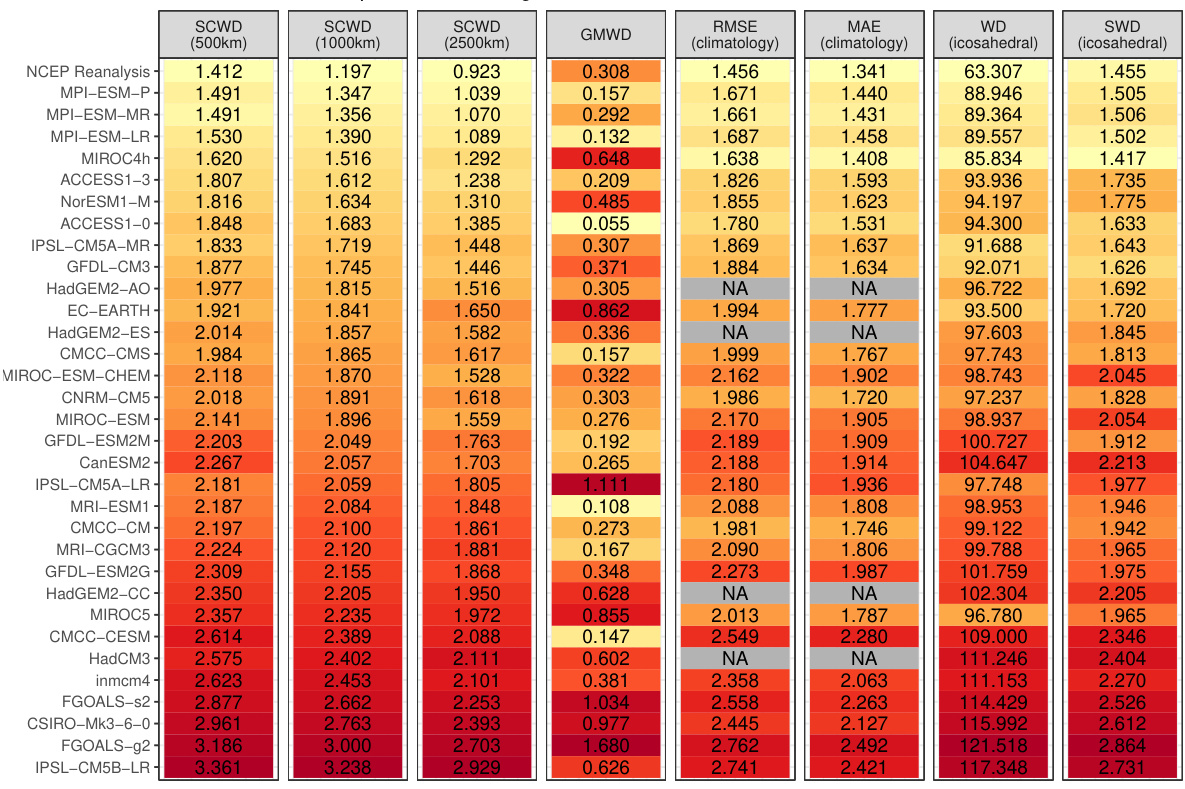

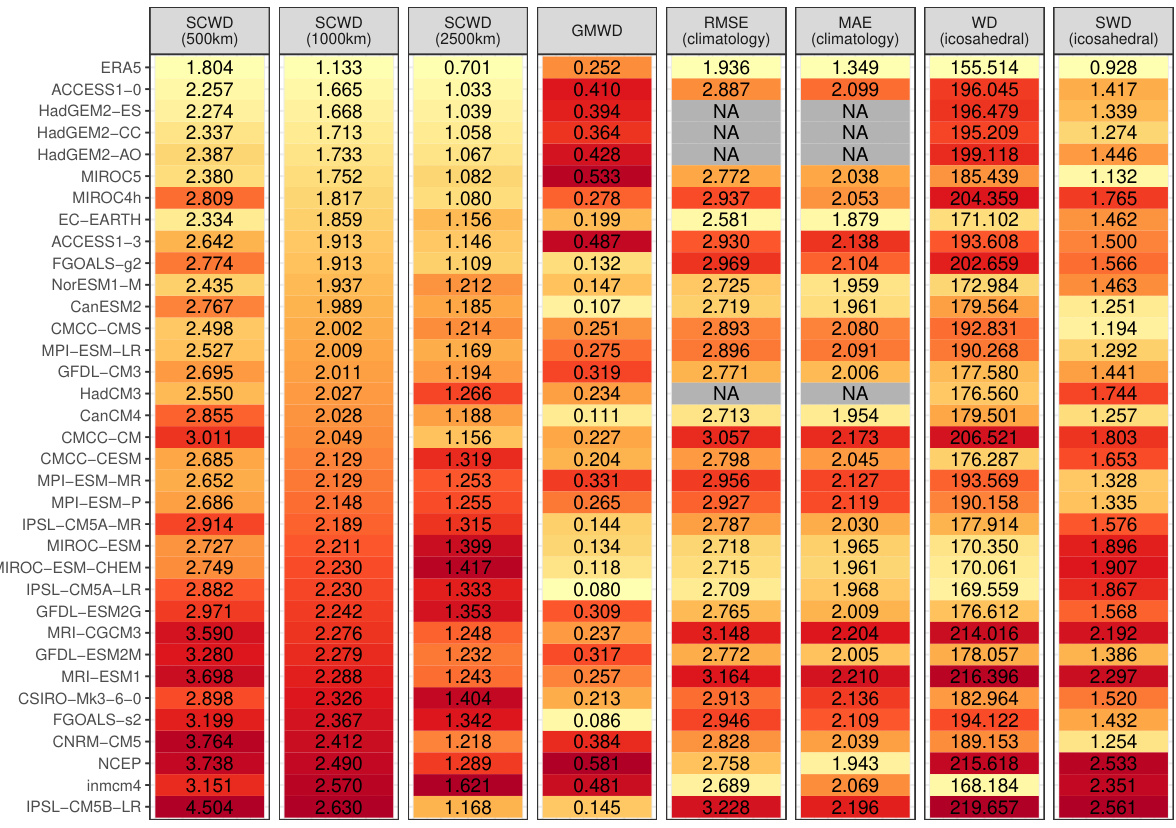

This table presents the rankings of CMIP6 climate models based on their similarity to ERA5 reanalysis data for 2-meter surface temperature. Multiple distance metrics are used for comparison, including the novel SCWD (Spherical Convolutional Wasserstein Distance) and several established methods like RMSE, MAE, WD, and sliced WD. The SCWD results are shown for three different kernel range parameters (500km, 1000km, 2500km) to assess sensitivity. Color coding helps visualize the rankings.

In-depth insights#

Spherical SCWD#

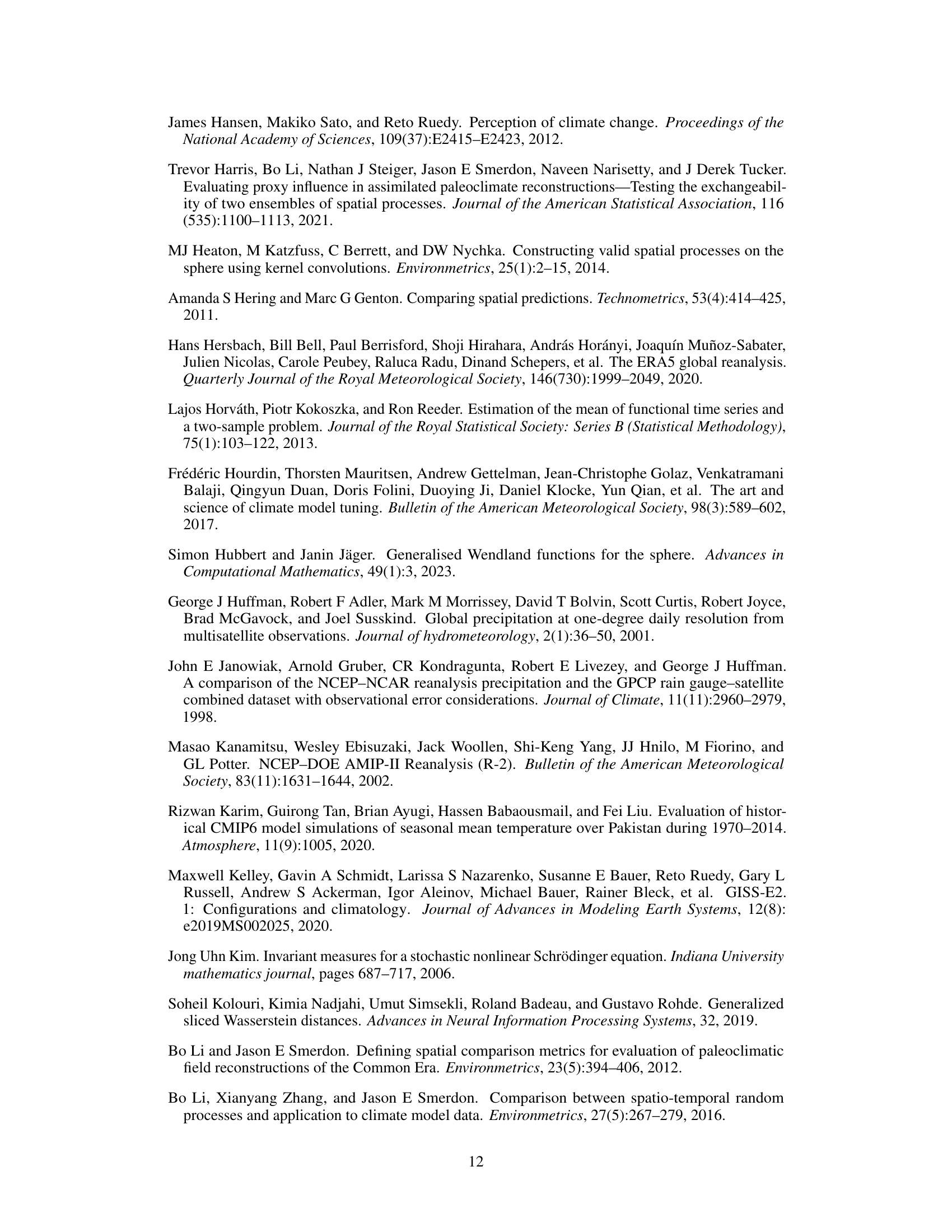

The concept of “Spherical SCWD” (Spherical Convolutional Wasserstein Distance) presents a novel approach to comparing climate model outputs with observational data. It directly addresses the limitations of previous methods by incorporating the spherical nature of the Earth’s surface and accounting for spatial variability using kernel convolutions. This is crucial because climate data isn’t uniformly distributed across the globe. The method’s strength lies in its ability to quantify local distributional differences, capturing variations not only in the mean but also in the higher-order moments (variance, etc.) of climate variables. This allows for a more nuanced and comprehensive evaluation of climate models than existing methods which often rely on simplistic global metrics like RMSE. The use of functional data analysis techniques enhances the method’s ability to handle the complex nature of climate data. The integration of the Wendland kernel facilitates efficient computation. The resulting SCWD values provide insights into both the overall agreement and local discrepancies between the model and observation, enabling a more fine-grained evaluation of climate models’ accuracy and skill. Overall, Spherical SCWD offers a powerful new tool for climate model validation, capable of yielding valuable insights into model performance and advancing our understanding of the Earth’s climate system.

CMIP Model Rank#

Analyzing CMIP model rankings involves a multi-faceted approach. The choice of evaluation metric significantly impacts the ranking, with different metrics highlighting various aspects of model performance. For example, metrics focusing on long-term means may not capture crucial regional or temporal variability, while metrics like the proposed Spherical Convolutional Wasserstein Distance (SCWD) aim to address these limitations. SCWD’s strength lies in considering spatial variability, offering a more comprehensive evaluation. However, the computational cost of SCWD should be considered, especially when dealing with large datasets. Comparing rankings across different metrics helps reveal model strengths and weaknesses across diverse aspects of climate simulation, offering a more nuanced understanding of model capabilities. Understanding the strengths and weaknesses of individual models is crucial for improving future climate models, and carefully chosen metrics provide valuable guidance. Ultimately, combining multiple metrics and focusing on regional details can lead to more robust and insightful CMIP model rankings.

Climate Metrics#

A thoughtful analysis of “Climate Metrics” would explore various methods for quantifying and comparing climate model performance against observational data. This involves examining metrics beyond simple measures like RMSE, considering the spatial distribution of errors using techniques like Wasserstein distance or convolutional neural networks. The choice of metric significantly impacts the interpretation of model skill, highlighting the need for methods that are robust to spatial biases and account for the complexity of climate systems. A robust “Climate Metrics” section would also delve into the challenges of comparing different climate models and datasets, such as variations in spatial resolution and temporal coverage. Intercomparison projects (like CMIP) provide invaluable data for benchmarking, but a comprehensive evaluation requires careful consideration of limitations and potential biases in both models and observational data. Ideally, the analysis would extend to discussions on the ongoing development of new metrics tailored to specific climate variables and the ongoing need for standardized and transparent evaluation frameworks to ensure accurate assessments and facilitate effective climate policy decisions.

Spatial Variability#

Spatial variability, in the context of climate modeling, refers to the differences in climate variables across geographical locations. Understanding and accurately representing this variability is crucial because climate models are used to predict future climate states at specific locations, not just global averages. Ignoring spatial variability can lead to inaccurate predictions and flawed assessments of regional climate impacts. The paper’s focus on spherical convolutional Wasserstein distance (SCWD) is particularly relevant here, as it aims to capture local differences in climate variable distributions, offering a more nuanced evaluation of model performance compared to methods relying only on global averages or simple metrics like RMSE. This localized approach allows for identifying regions where models exhibit stronger or weaker agreement with observational data, providing insights into the model’s strengths and weaknesses at specific locations. The spatial aspect of SCWD makes it suitable for evaluating climate models, which produce outputs on spherical coordinates, thus offering significant improvement over existing methods struggling to handle such data properly.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on spherical convolutional Wasserstein distance (SCWD) for climate model validation are plentiful. Extending SCWD to handle spatiotemporal data is crucial for capturing climate dynamics fully. Investigating the impact of kernel choice and range parameter on SCWD’s performance, and exploring adaptive or learned kernel functions to enhance sensitivity to specific climate features, warrant further investigation. The application of SCWD to other climate variables, and more sophisticated evaluation metrics beyond simple ranking, should be explored. Assessing the robustness of SCWD under different climate scenarios and model resolutions is vital to gauge its general applicability. Finally, the development of computationally efficient algorithms to scale SCWD to even larger datasets, perhaps through dimensionality reduction techniques, remains a priority.

More visual insights#

More on figures

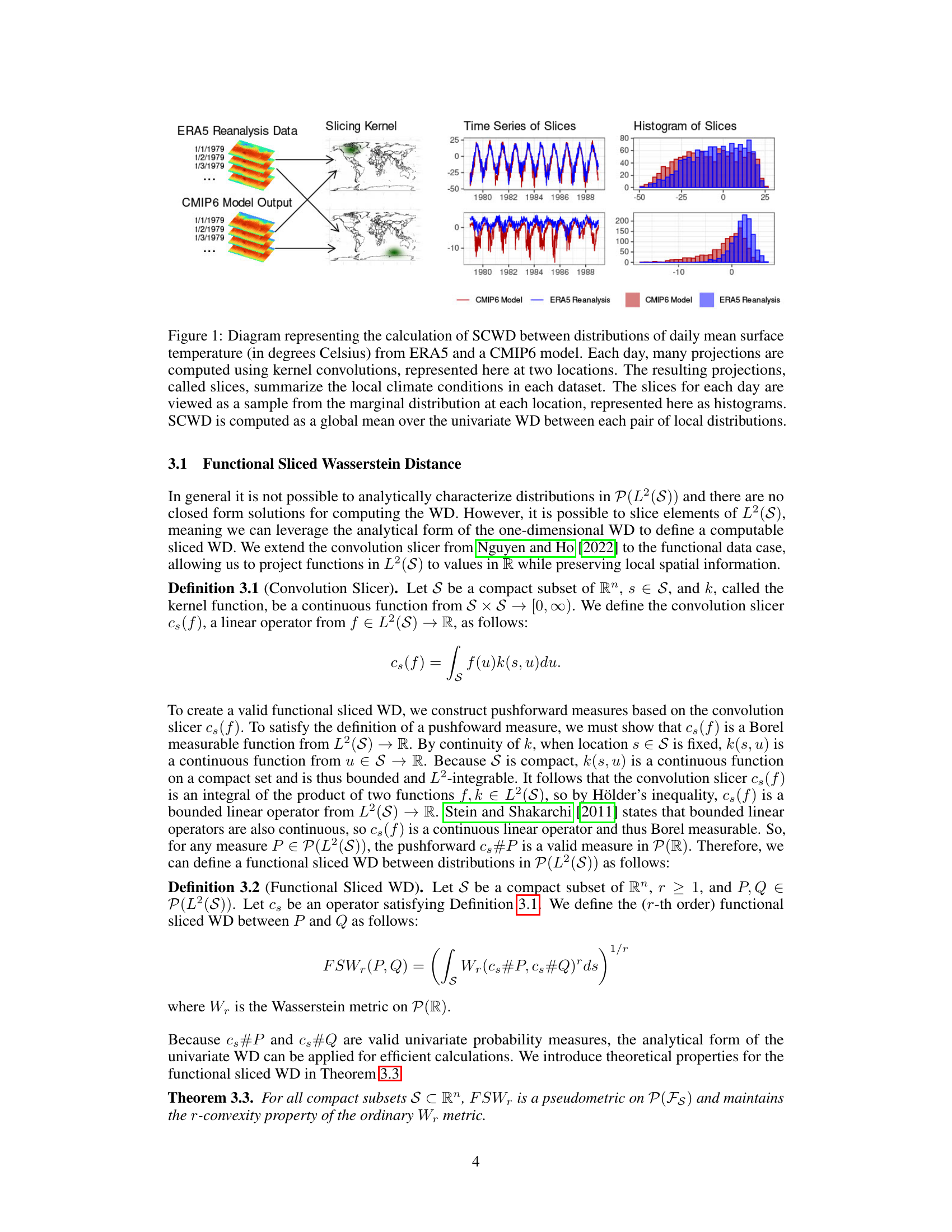

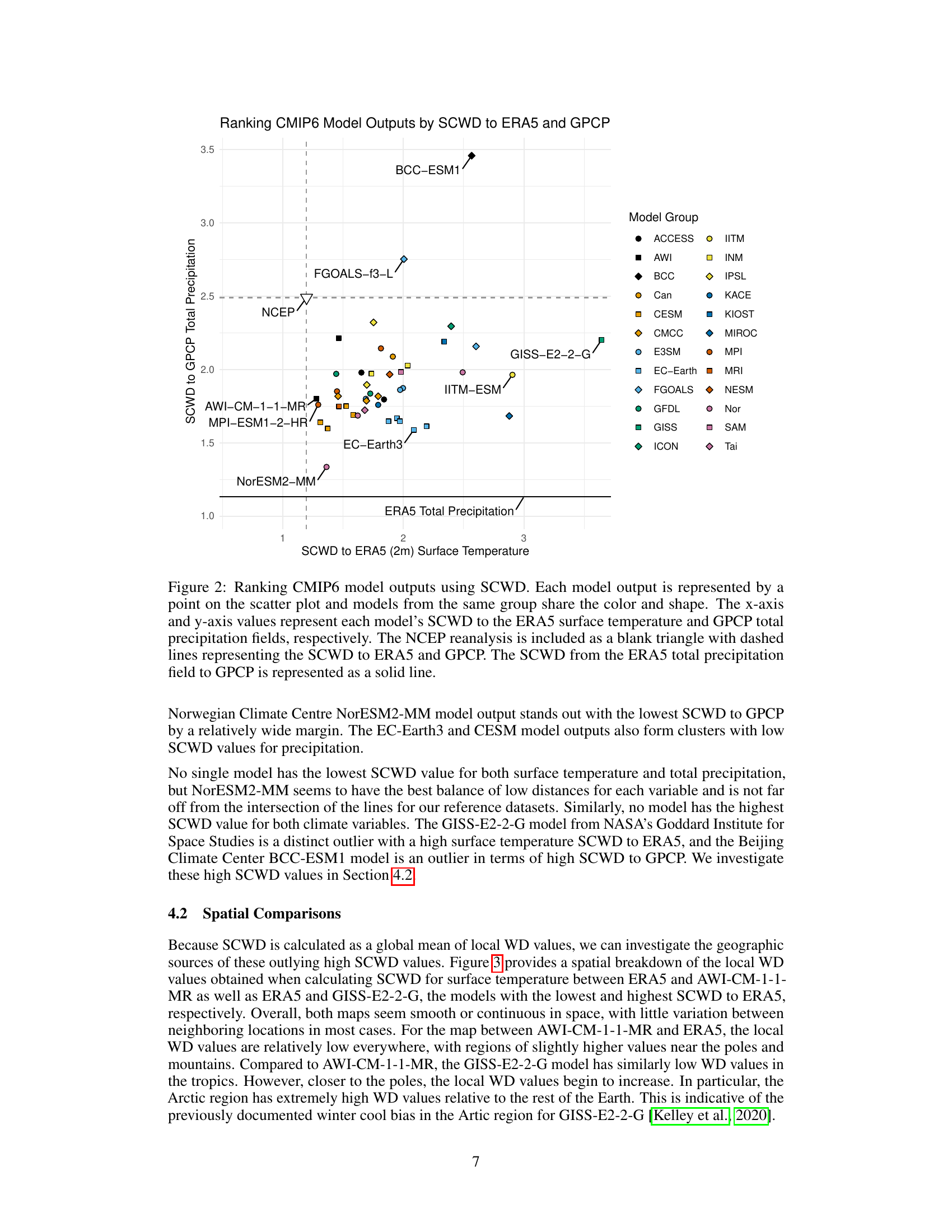

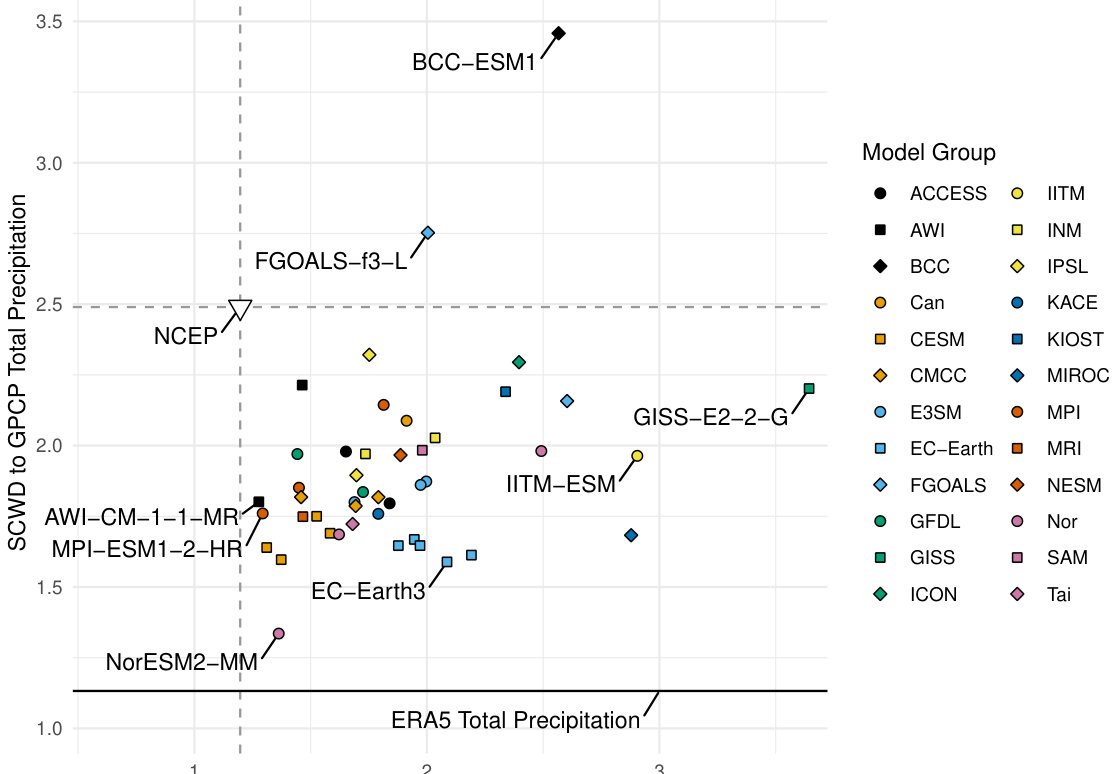

This figure shows a scatter plot ranking CMIP6 climate models based on their similarity to ERA5 (for temperature) and GPCP (for precipitation) using the Spherical Convolutional Wasserstein Distance (SCWD). Each point represents a model, colored and shaped to indicate its modeling group. The x-axis shows the SCWD to ERA5 temperature, and the y-axis shows the SCWD to GPCP precipitation. NCEP reanalysis data is included for comparison. Models closer to the lower left corner show better agreement with the observational data.

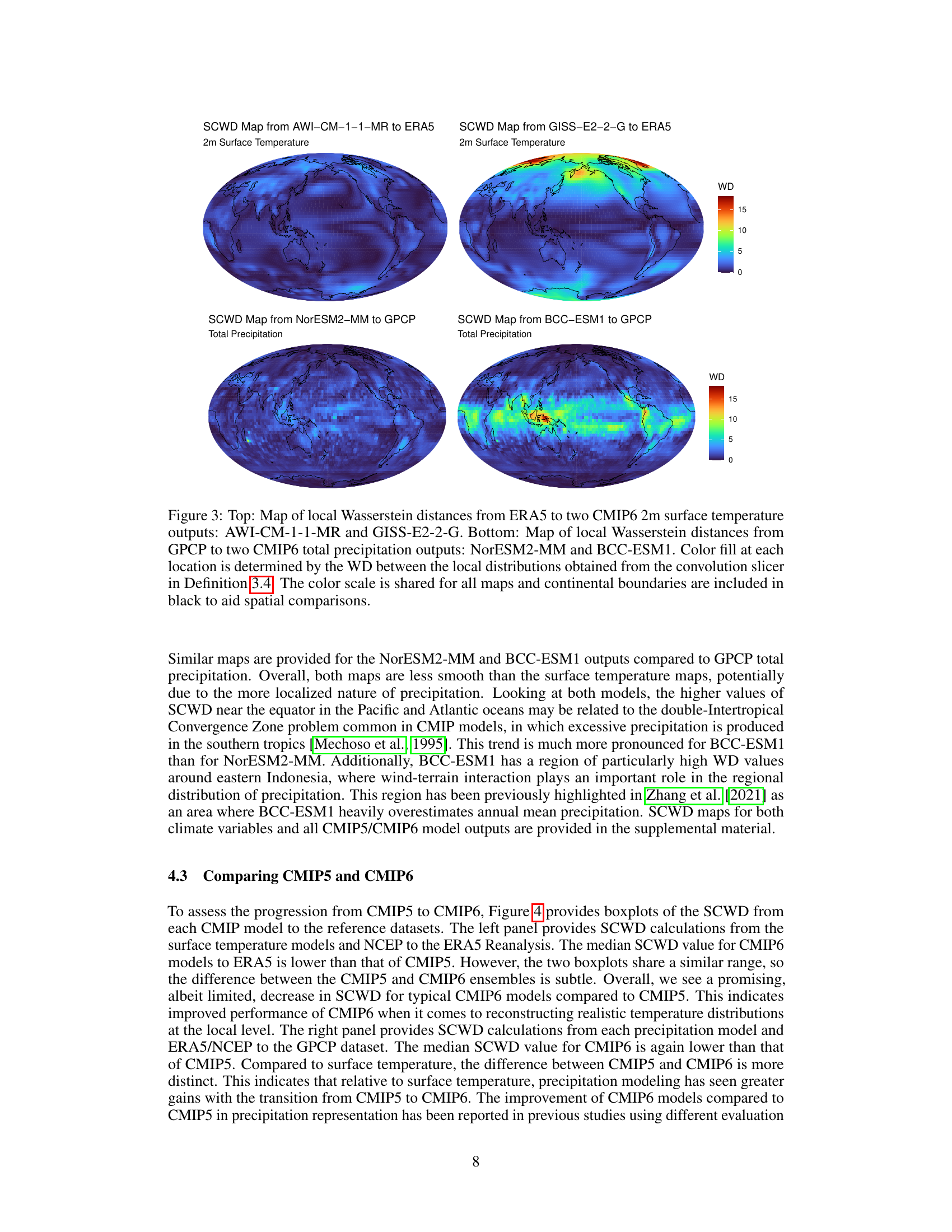

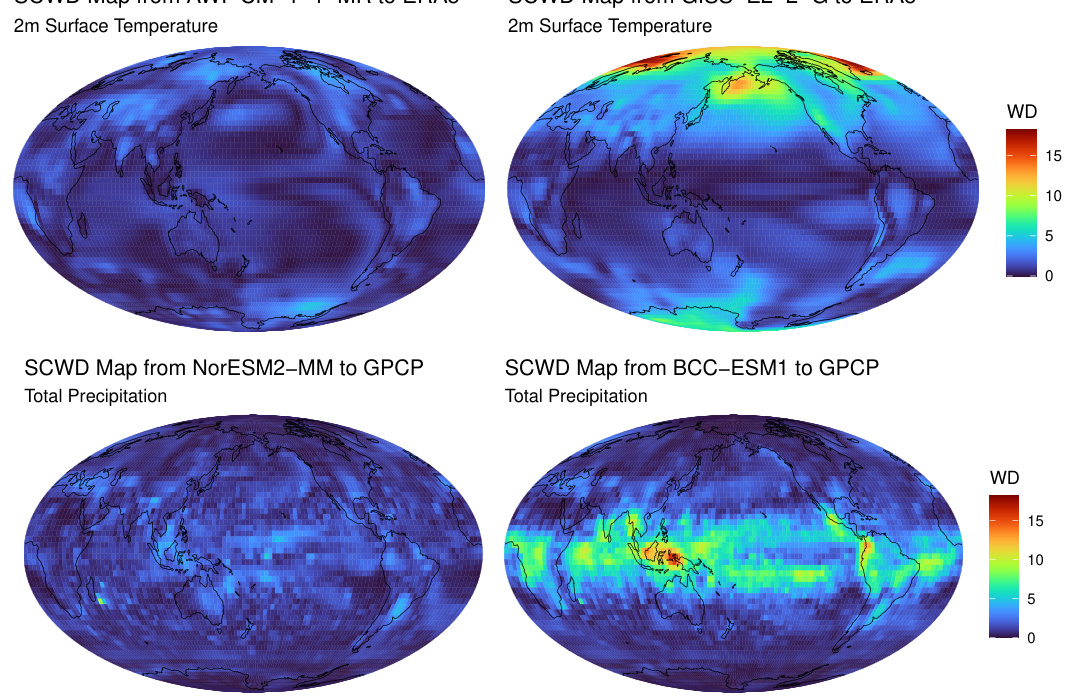

This figure shows maps of local Wasserstein distances, calculated using the spherical convolutional Wasserstein distance (SCWD) method, comparing climate model outputs from CMIP6 against ERA5 reanalysis data (for 2m surface temperature) and GPCP data (for total precipitation). The maps visualize regional differences in climate variable distributions between the models and reference datasets, highlighting areas of high discrepancies. The top panels display results for temperature, and the bottom panels display results for precipitation. AWI-CM-1-1-MR and NorESM2-MM show relatively low overall distances, while GISS-E2-2-G and BCC-ESM1 exhibit notable regional discrepancies.

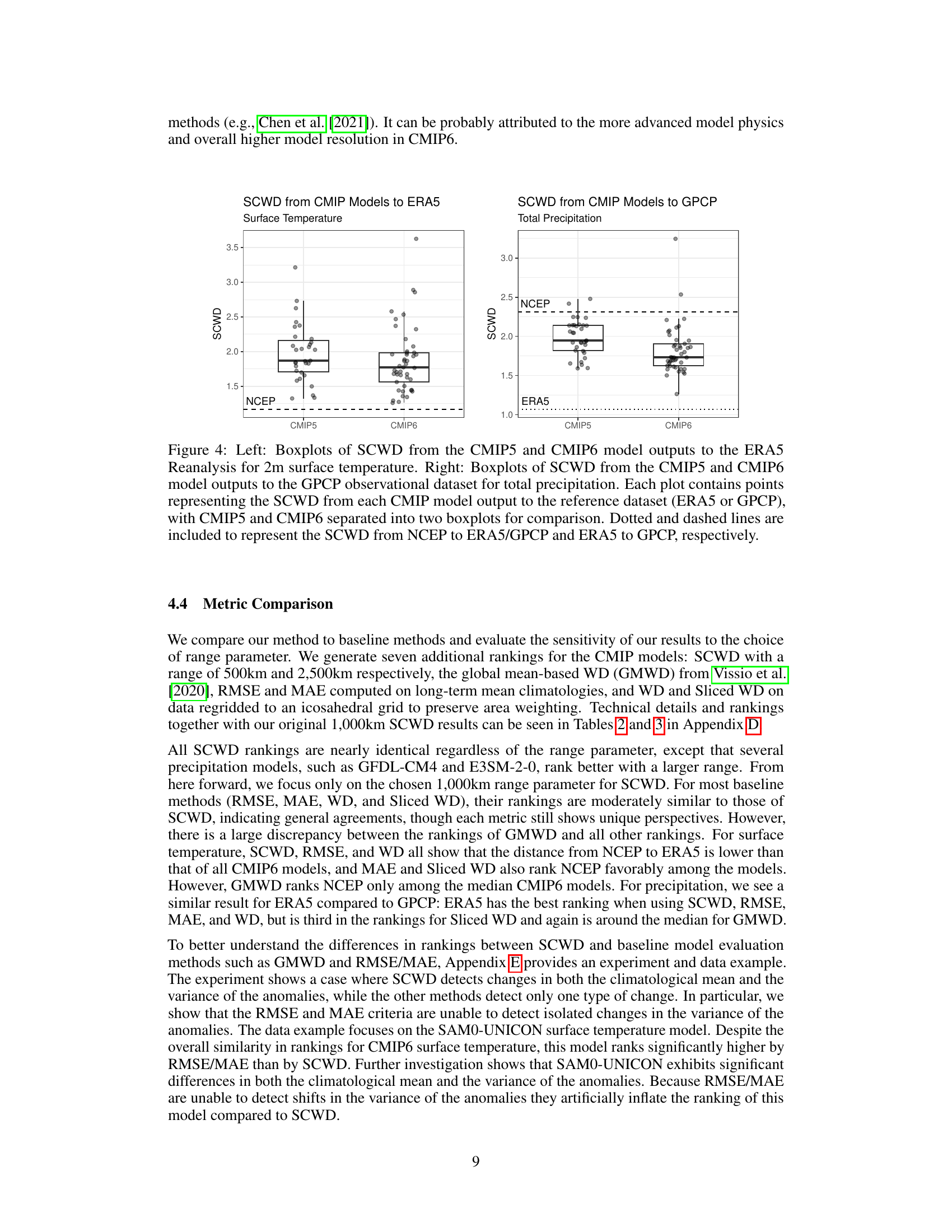

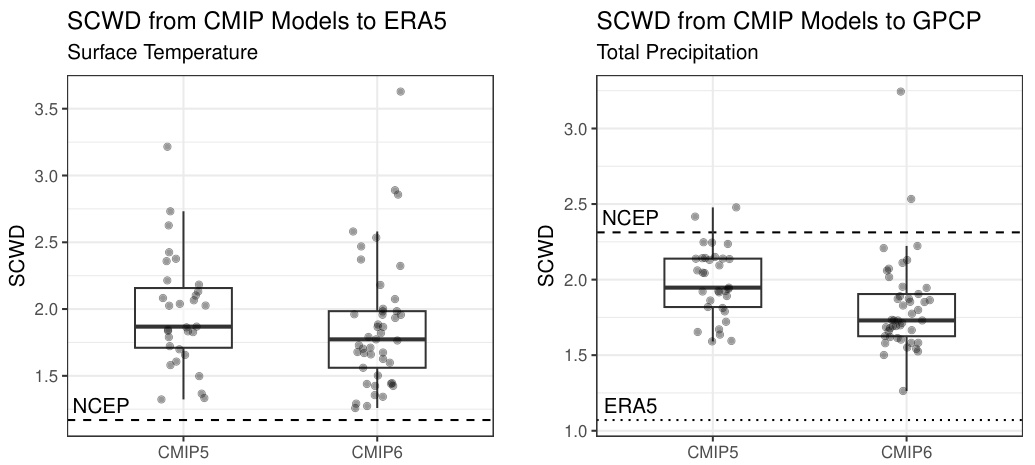

This figure compares the performance of CMIP5 and CMIP6 climate models in reproducing surface temperature and total precipitation using the Spherical Convolutional Wasserstein Distance (SCWD). The left panel shows boxplots of SCWD values for surface temperature, comparing each model’s output against ERA5 reanalysis data. The right panel presents similar boxplots for total precipitation, comparing model outputs against GPCP observational data. NCEP reanalysis data is also included for comparison in both panels. Dotted and dashed lines represent the distances between reference datasets (ERA5 and NCEP for temperature, GPCP and ERA5 for precipitation). The figure illustrates the relative improvement (or lack thereof) in the accuracy of CMIP6 models compared to CMIP5 models for both climate variables.

This figure shows a scatter plot ranking CMIP6 climate models based on their SCWD scores against ERA5 (for temperature) and GPCP (for precipitation). The x-axis represents the SCWD score for temperature, and the y-axis represents the SCWD score for precipitation. Each model is represented by a point, with color and shape indicating model group. The plot helps visualize which models perform well in both temperature and precipitation simulations, and which show discrepancies.

This figure displays the ranking of CMIP6 model outputs based on their similarity to ERA5 surface temperature and GPCP total precipitation data using the Spherical Convolutional Wasserstein Distance (SCWD). Each model is represented as a point on a scatter plot, with color and shape indicating model groups. The x-axis shows SCWD to ERA5 temperature and the y-axis shows SCWD to GPCP precipitation. NCEP reanalysis data is included for comparison. The figure helps visualize the performance of different climate models in reproducing observed climate data.

This figure shows a scatter plot ranking CMIP6 climate models based on their SCWD scores against ERA5 surface temperature and GPCP total precipitation. Lower SCWD scores indicate better agreement with observational data. Model groups are color-coded for easier comparison. The plot also includes the SCWD scores between ERA5 and NCEP and between ERA5 and GPCP, serving as benchmarks.

This figure shows a scatter plot ranking CMIP6 climate models based on their SCWD scores against ERA5 (surface temperature) and GPCP (total precipitation). Each point represents a model, colored and shaped according to its modeling group. The x-axis shows SCWD scores for temperature, and the y-axis shows SCWD scores for precipitation. Lower scores indicate better agreement with observations. NCEP reanalysis data is included for comparison, along with the SCWD between ERA5 and GPCP. This visualization allows for a comparison of model performance across both variables.

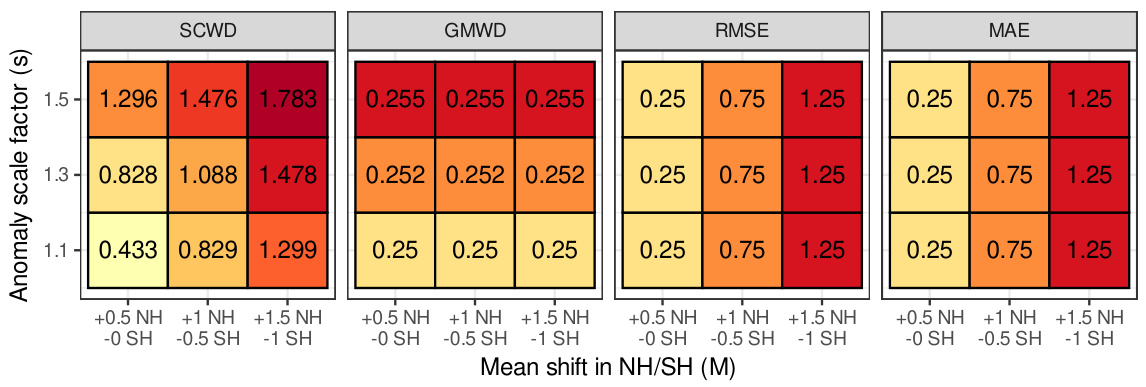

This figure presents the results of a synthetic experiment designed to evaluate the ability of different distance metrics (SCWD, GMWD, RMSE, and MAE) to detect changes in both the mean and variance of temperature anomalies simultaneously. The experiment manipulates the ERA5 reanalysis dataset by applying various mean shifts (M) across the northern and southern hemispheres, and scaling the variance of the anomalies (s). The heatmaps show the resulting rankings of these modified datasets relative to the original ERA5 data for each metric, with color intensity reflecting the distance (ranking). The results highlight the unique sensitivity of SCWD to both mean and variance changes, unlike the other metrics.

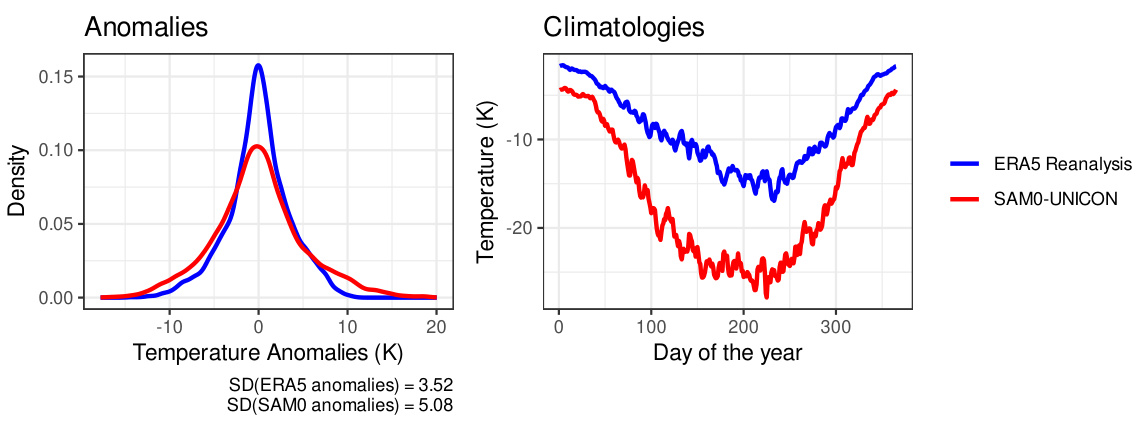

This figure compares the distribution of temperature anomalies and the climatology between ERA5 reanalysis data and SAM0-UNICON climate model output for a specific region where the local Wasserstein distance is high. The left panel displays density plots of the temperature anomalies, highlighting the difference in their distributions. The right panel presents time series of daily average temperatures over a year, illustrating the differences in climatological patterns. This visual comparison helps to understand why the SAM0-UNICON model receives different rankings based on different evaluation methods. The different standard deviations of anomalies in ERA5 and SAM0-UNICON are also explicitly shown in the figure.

More on tables

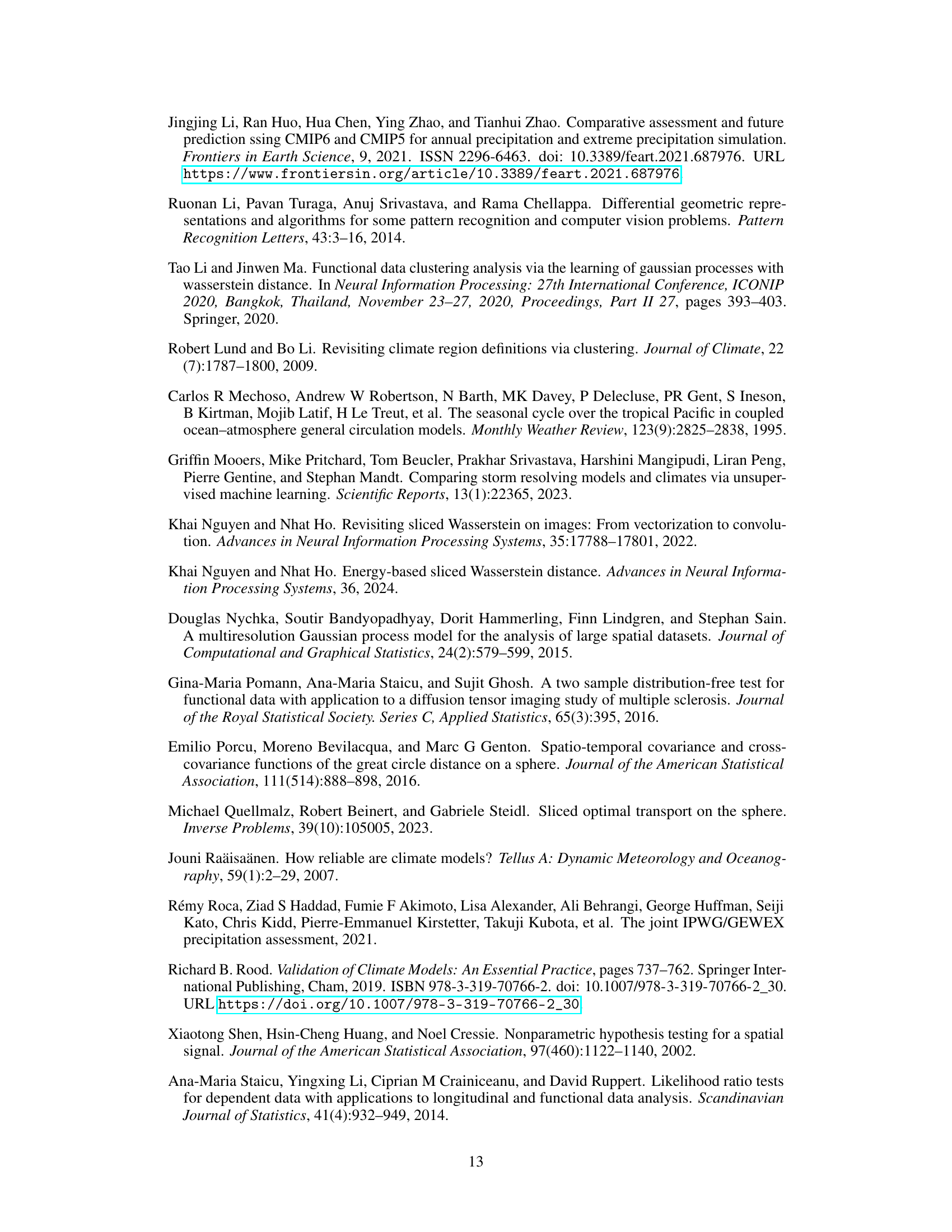

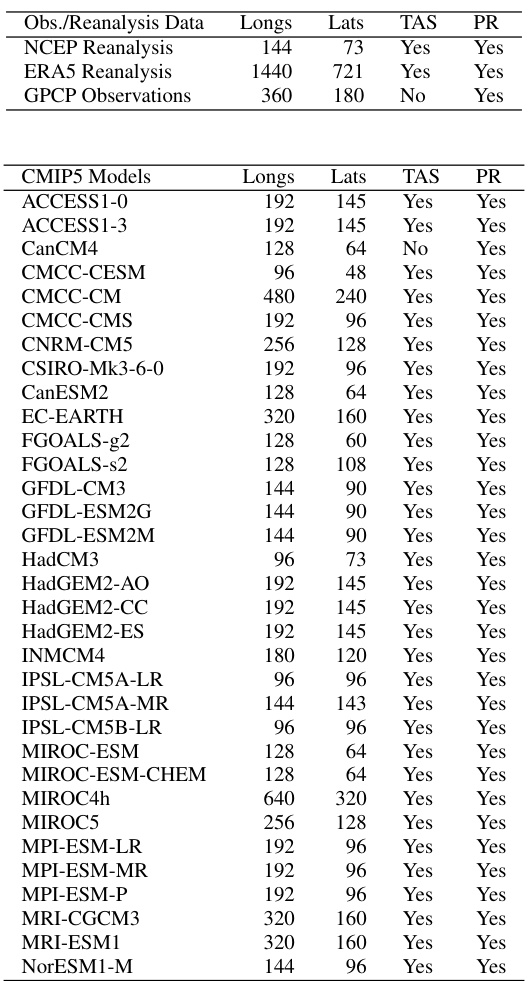

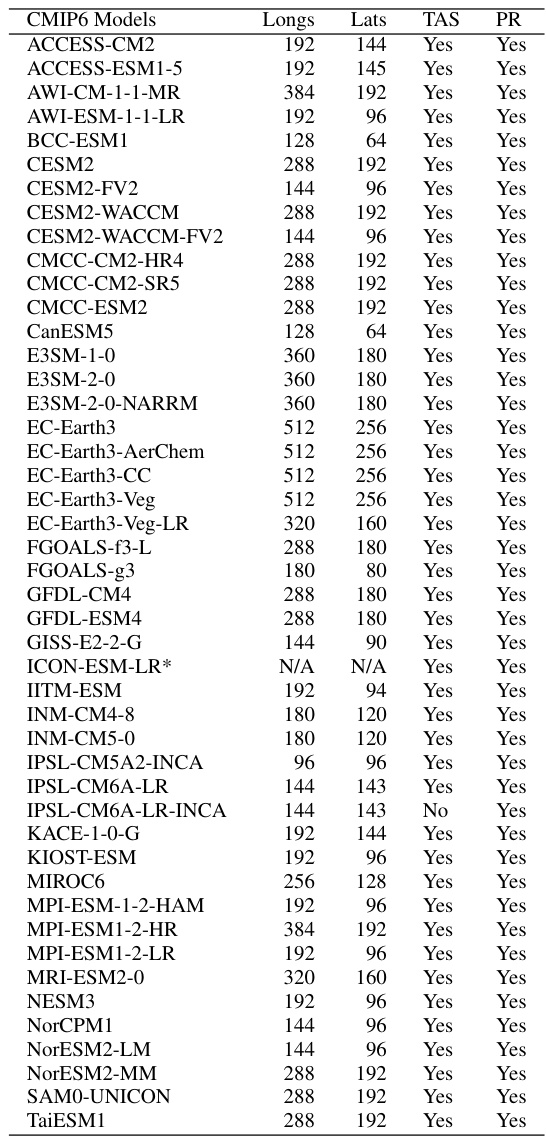

This table lists the details of the datasets used in the paper’s analysis, including observational data (NCEP Reanalysis, ERA5 Reanalysis, GPCP Observations), CMIP5 model outputs, and CMIP6 model outputs. For each dataset, it specifies the longitude and latitude resolution of the grid and whether surface temperature and total precipitation data are available.

This table presents the rankings of CMIP6 climate models based on their similarity to ERA5 reanalysis data for 2-meter surface temperature. Several distance metrics are used for comparison, including the proposed Spherical Convolutional Wasserstein Distance (SCWD) and several baseline methods (global mean-based WD, RMSE, MAE, WD, and Sliced WD). The table also shows the sensitivity of the SCWD rankings to the choice of kernel range parameter.

Full paper#