↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many machine learning applications involve minimizing functionals over probability distributions, a complex problem due to the infinite-dimensional nature of the space. Existing methods often lack efficiency or rigorous convergence guarantees, particularly when dealing with ill-conditioned problems or alternative geometries. This necessitates a new approach that considers geometric properties for better optimization.

This research tackles this challenge by adapting mirror descent and preconditioned gradient descent to the Wasserstein space. The authors provide convergence guarantees under relative smoothness and convexity conditions, carefully selecting curves along which these properties hold. Experiments on various tasks, including single-cell data alignment, showcase the algorithms’ superior performance over existing methods, highlighting the benefits of adapting the geometry induced by the regularizer.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in machine learning and optimization because it bridges the gap between theoretical optimization methods and their practical applications in the challenging landscape of probability distributions. It introduces novel algorithms that improve efficiency and provide convergence guarantees for tasks where traditional methods struggle. This opens exciting avenues for various applications, including generative modeling and computational biology.

Visual Insights#

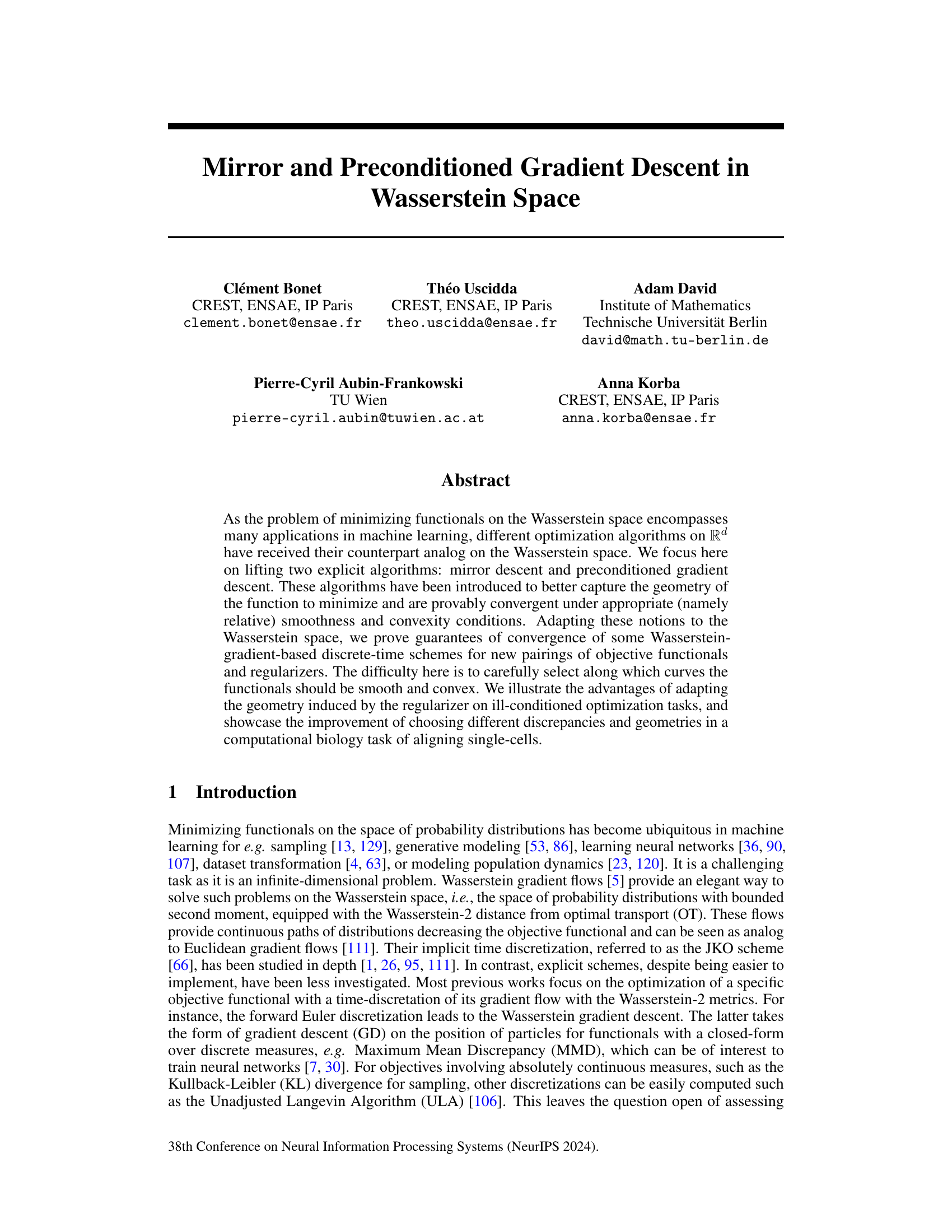

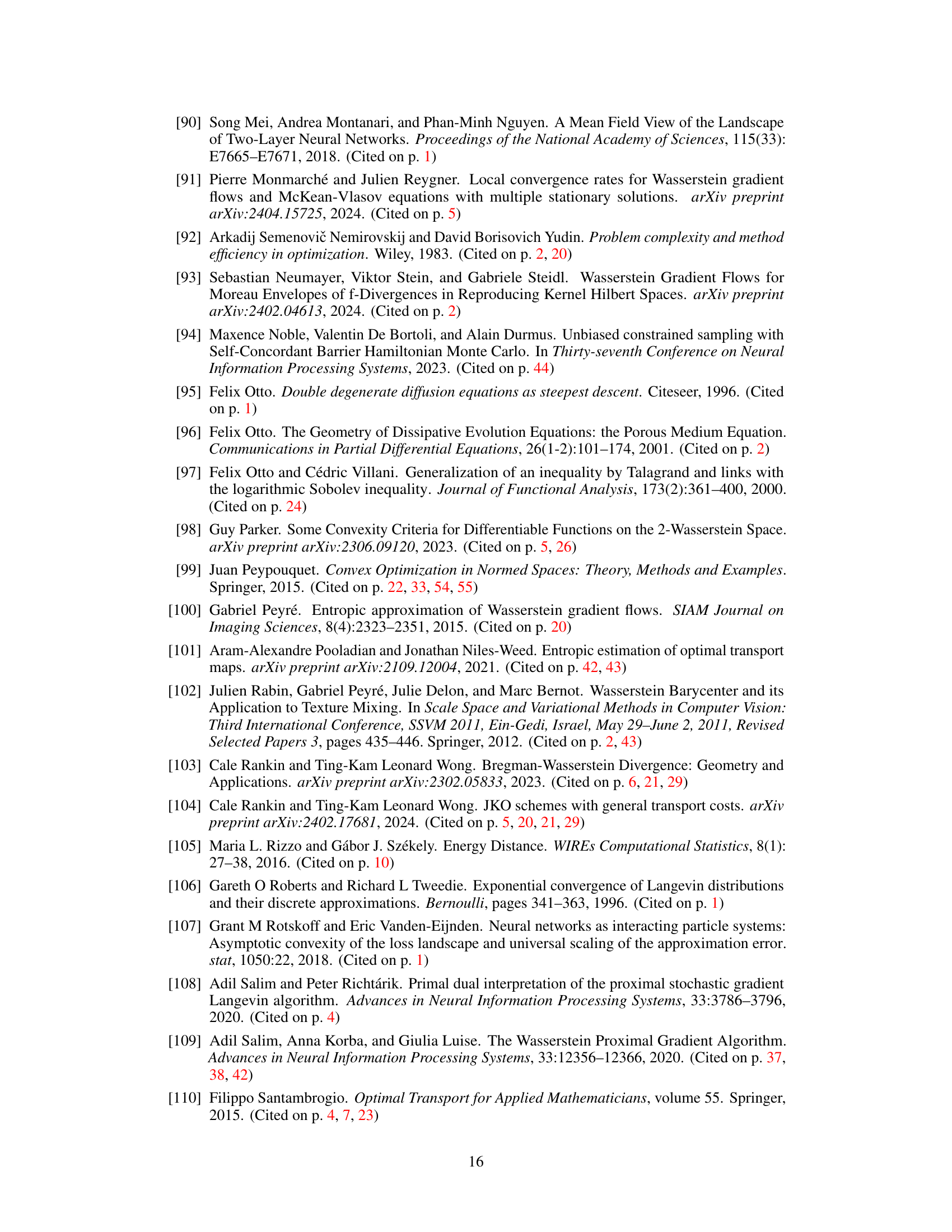

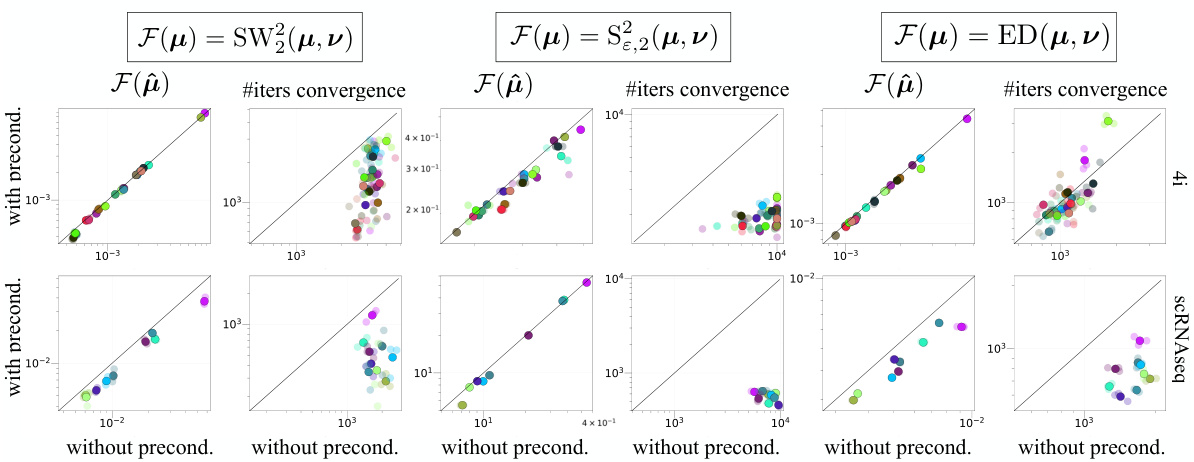

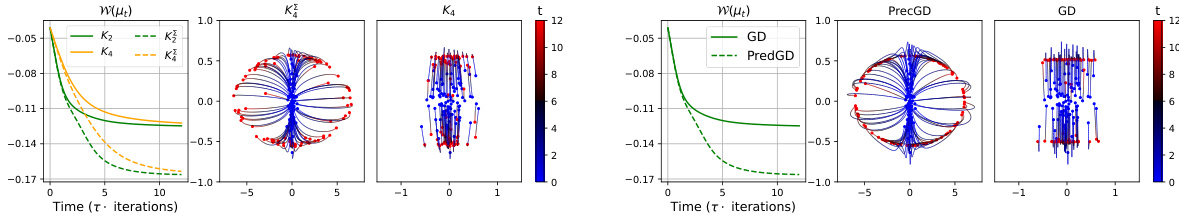

This figure presents the results of minimizing the Wasserstein distance between two probability distributions using mirror descent with different interaction Bregman potentials. The left panel shows the value of the Wasserstein distance (W) over time (number of iterations) for two different potentials. The middle and right panels display the trajectories of particles during the optimization process for the two potentials, visualizing how the particles move to minimize W. The results highlight the different dynamics of the optimization depending on the choice of potential.

In-depth insights#

Wasserstein Geometry#

Wasserstein geometry, a branch of optimal transport theory, provides a powerful framework for analyzing probability distributions. It leverages the Wasserstein distance, measuring the minimum effort to transform one distribution into another, to define a geometric structure on the space of probability measures. This geometry is particularly useful when dealing with distributions that are not easily represented in Euclidean space, such as those encountered in machine learning applications involving images, text, or other high-dimensional data. The Wasserstein metric accounts for the underlying structure of the data, unlike Euclidean metrics which can be misleading in these scenarios. Key concepts like Wasserstein gradient flows and their discretizations (e.g., JKO scheme) provide powerful tools for optimization and sampling in this non-Euclidean setting. The choice of a specific Wasserstein metric (e.g., W1, W2) influences the geometric properties and the computational cost of algorithms. Moreover, recent advances focus on the use of Bregman divergences to define more general geometries within the Wasserstein space, enabling efficient optimization algorithms even for non-smooth objective functions. Understanding and exploiting Wasserstein geometry is therefore critical for tackling various problems in machine learning and related fields where dealing with probability distributions is central.

Mirror Descent MD#

Mirror Descent (MD) is a powerful optimization algorithm particularly well-suited for minimizing functionals over probability distributions. Its core strength lies in its ability to leverage Bregman divergences, which provide a flexible way to adapt the algorithm’s geometry to the specific characteristics of the problem. Unlike standard gradient descent, MD doesn’t rely on Euclidean smoothness; instead, it uses relative smoothness and convexity defined with respect to the Bregman divergence. This makes it particularly effective in handling objective functions with non-Lipschitz gradients or complex geometries. When adapted to Wasserstein space, MD offers a principled method to perform optimization over probability distributions. The Wasserstein gradient, combined with the Bregman divergence based update step, ensures convergence under specific smoothness and convexity conditions. The choice of the Bregman divergence itself becomes a crucial parameter, offering the potential to improve the algorithm’s performance by adapting the geometry to the problem at hand. This is illustrated by the paper’s application to biological problems, where the choice of divergence is shown to significantly affect results, highlighting the flexibility and potential of MD in Wasserstein space for complex applications.

Precond. Gradient#

The heading ‘Precond. Gradient’ likely refers to a section detailing preconditioned gradient descent within the context of Wasserstein space. This optimization method likely addresses the challenges of minimizing functionals over probability distributions by incorporating a preconditioner. This matrix transforms the gradient, potentially improving convergence speed and efficiency, especially for ill-conditioned problems where standard gradient descent struggles. The method likely involves adapting the preconditioner to the specific geometry of the Wasserstein space, making it suitable for optimal transport problems and applications in machine learning that involve probability distributions. The discussion probably includes theoretical analysis proving convergence guarantees under specific conditions related to the smoothness and convexity of the functional and the preconditioner. Furthermore, the section likely features empirical results demonstrating the effectiveness of the preconditioned gradient descent in solving challenging optimization tasks, potentially showcasing improvements in convergence speed or solution quality compared to standard gradient descent in a computational biology task of aligning single cells.

Single-Cell Results#

The single-cell analysis section would ideally delve into the application of the proposed mirror and preconditioned gradient descent methods to real-world single-cell data. It should showcase how these methods, with their tailored geometries and preconditioning strategies, improve the accuracy and efficiency of aligning single-cell datasets compared to traditional methods. Key results should include visualizations demonstrating improved alignment, metrics comparing the performance of the novel methods against standard techniques (e.g., Wasserstein gradient descent), and a discussion on the choice of regularizers and their impact on performance. An important aspect would be the handling of noisy and incomplete data common in single-cell experiments, and how the methods’ robustness addresses such challenges. Finally, the biological insights gleaned from the improved alignment (e.g., identification of cell trajectories, understanding of cell differentiation) should be highlighted. The discussion should also address the computational cost and scalability of the proposed methods, comparing favorably to existing state-of-the-art alternatives.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Extending the theoretical framework to encompass more general geometries and cost functions beyond the Wasserstein-2 distance would enhance the applicability and flexibility of mirror and preconditioned gradient descent methods. Investigating the impact of different Bregman divergences and preconditioners on the convergence rate and computational efficiency is crucial for practical implementation. Furthermore, developing efficient algorithms to compute Wasserstein gradients for complex functionals would significantly improve the scalability of the proposed methods. Finally, empirical evaluations on a broader range of real-world applications, including tasks with high-dimensional data or complex functional forms, are needed to validate the effectiveness and practicality of these optimization algorithms in diverse scenarios.

More visual insights#

More on figures

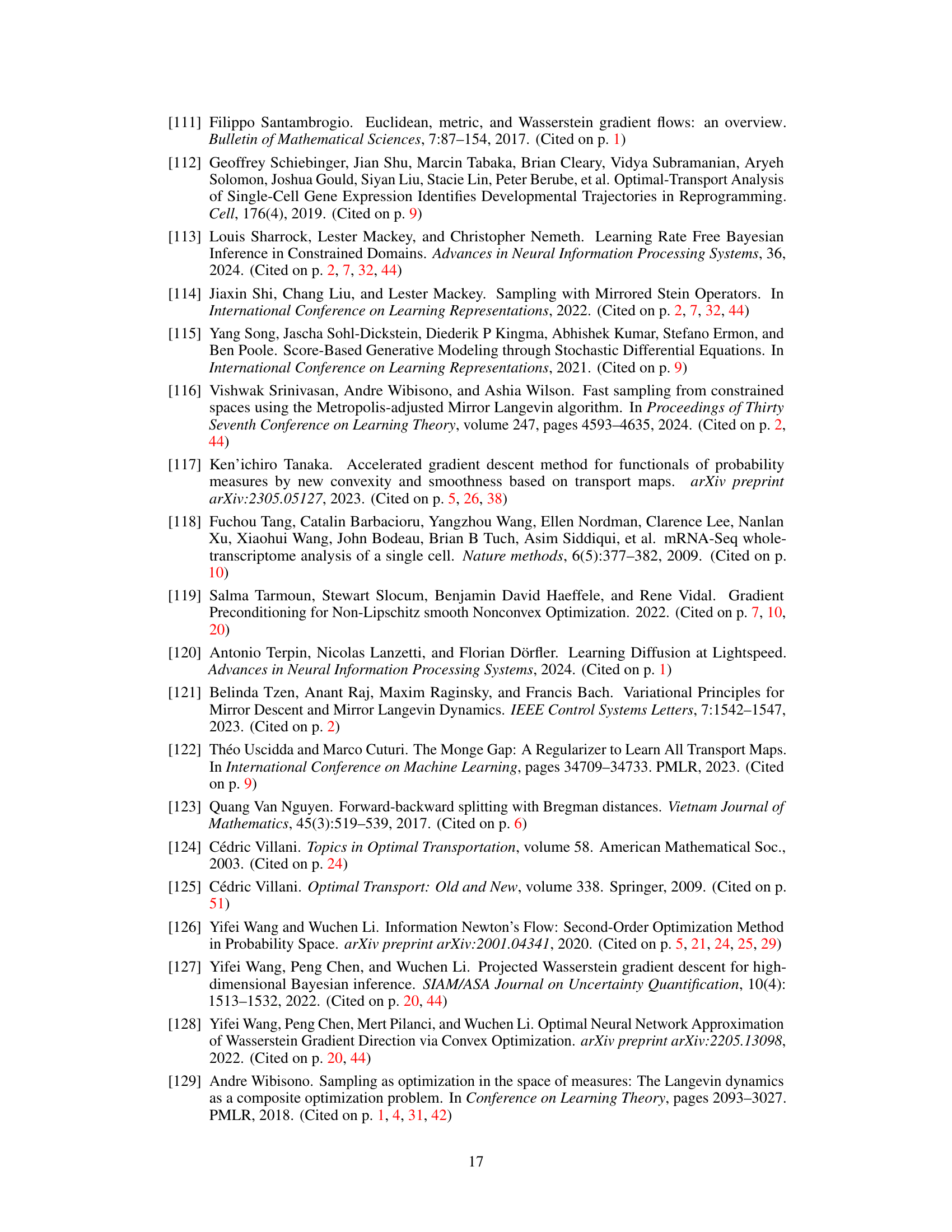

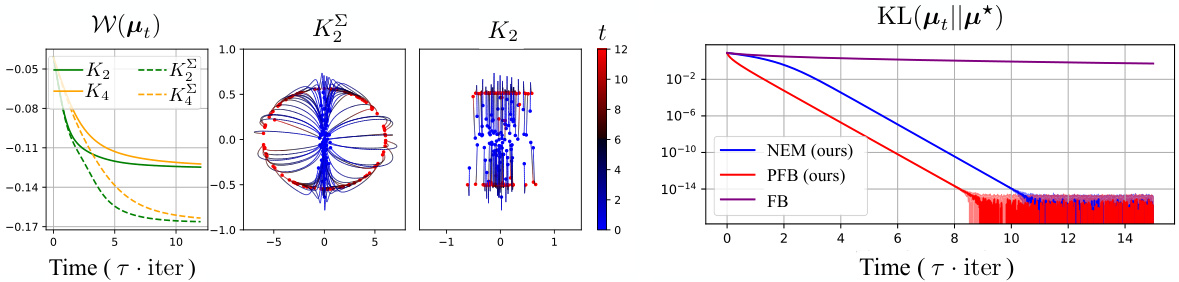

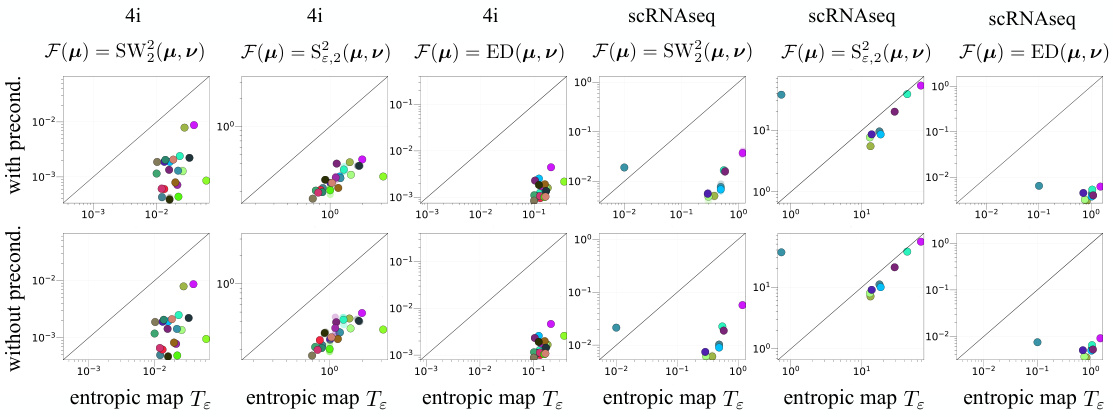

This figure compares the performance of preconditioned gradient descent (PrecGD) and vanilla gradient descent (GD) in predicting cellular responses to cancer treatments using two different datasets (4i and scRNAseq). For each treatment, the algorithms minimize a distance function (D) between the untreated (μ₁) and treated (vi) cell populations. The figure presents scatter plots showing the minimum attained by each method (y-axis) against the number of iterations to convergence (x-axis). The plots are separated by datasets and metrics. Points below the diagonal indicate superior performance of PrecGD, showcasing its improvement in finding better minima and converging faster.

This figure shows the results of minimizing the Wasserstein distance between two probability distributions using mirror descent with two different interaction Bregman potentials. The left panel shows the evolution of the Wasserstein distance (W) over time for the two potentials. The middle and right panels show the trajectories of particles during the optimization process for each potential. The trajectories illustrate how the particles move to minimize the Wasserstein distance between the two distributions. The different potentials lead to different optimization paths and convergence rates.

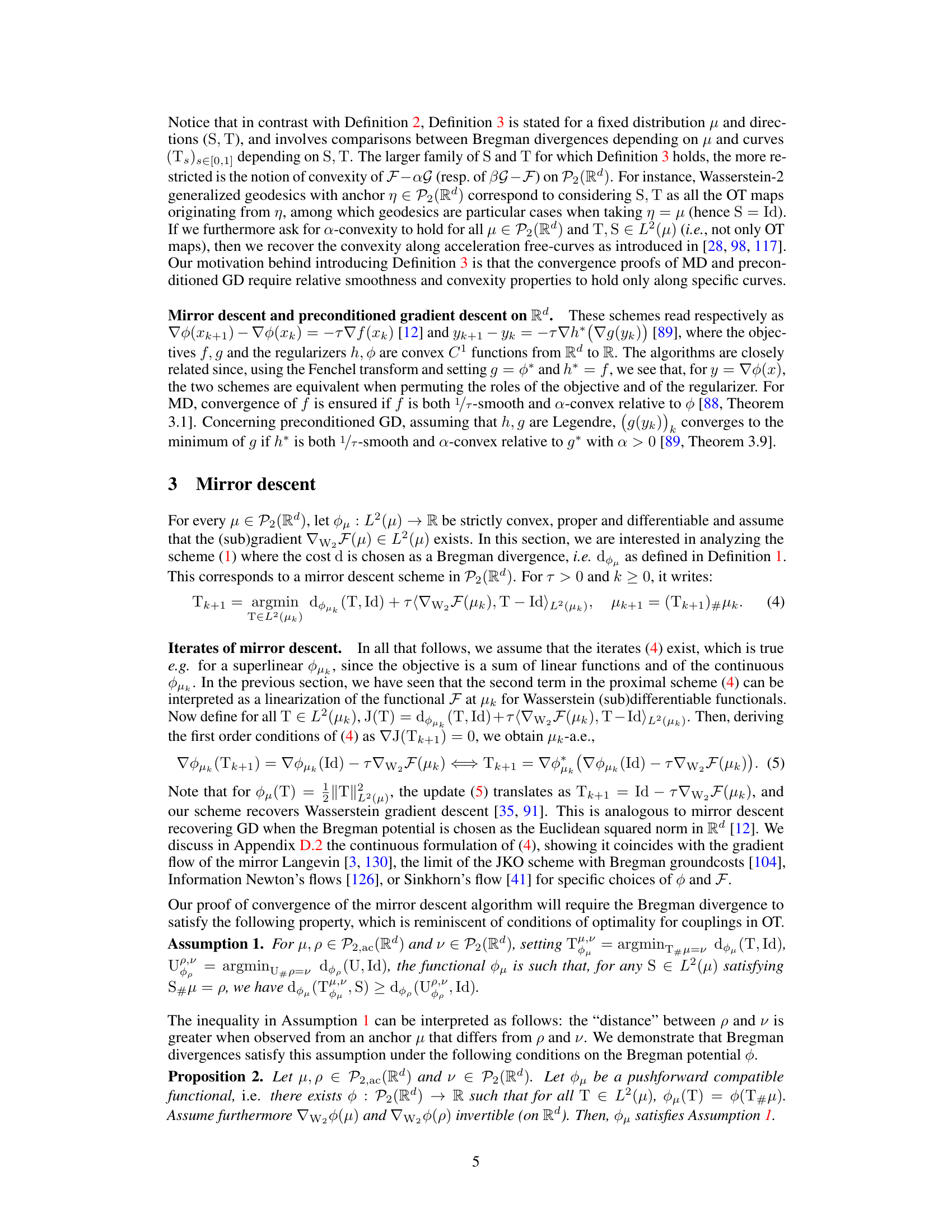

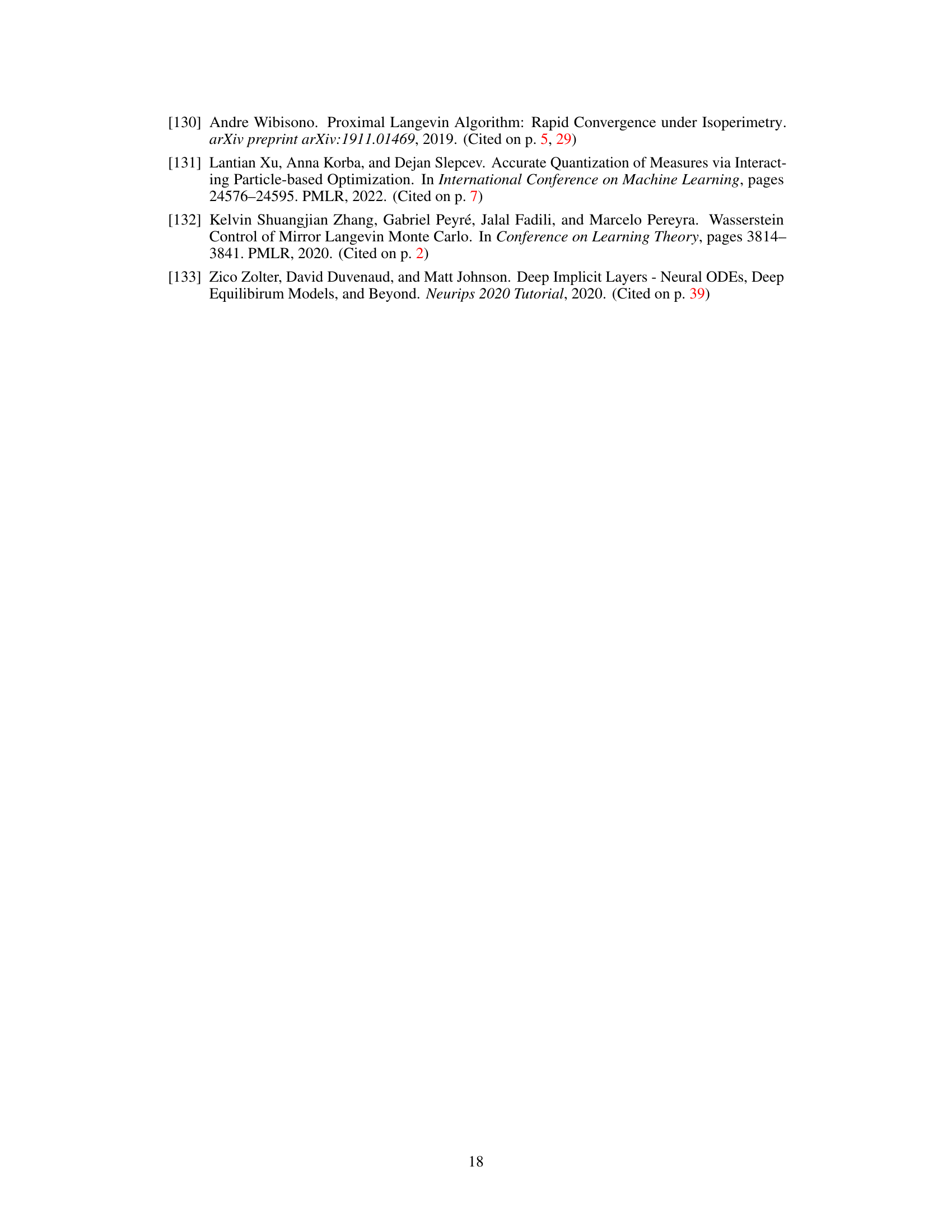

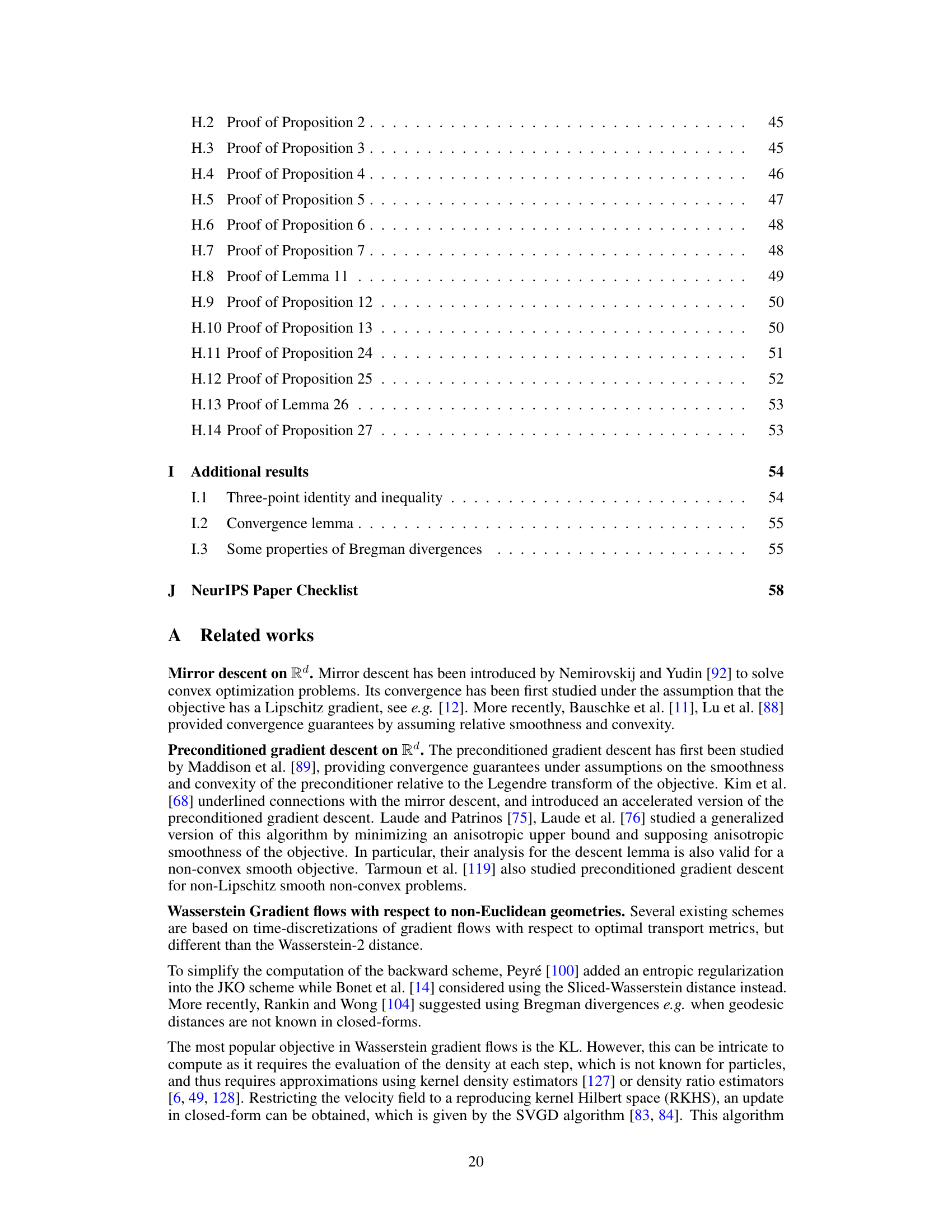

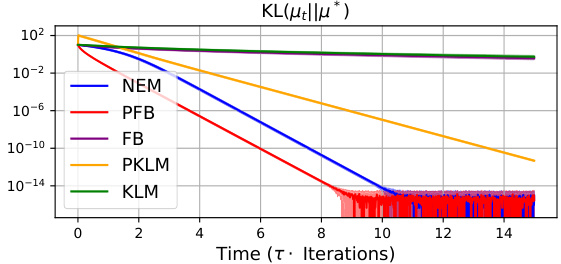

This figure shows the convergence of different optimization methods towards a Gaussian distribution. The x-axis represents time (in iterations), and the y-axis shows the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence between the current distribution and the target Gaussian distribution. Multiple methods (NEM, PFB, FB, PKLM, KLM) are compared, illustrating their relative convergence speeds. The target Gaussian distributions are generated with varying covariances to test the robustness of the methods.

This figure shows the results of minimizing the Wasserstein distance between two probability distributions using different interaction Bregman potentials. The left panel displays the value of the Wasserstein distance (W) over time, demonstrating the convergence of the optimization process. The middle and right panels visualize the trajectories of particles during the optimization, illustrating how the particles move to minimize the Wasserstein distance. Different colors represent different Bregman potentials, showing the impact of the choice of potential on the optimization process.

This figure compares the performance of preconditioned gradient descent (PrecGD) and vanilla gradient descent (GD) against the entropic map (Te) in predicting cell population responses to cancer treatments. Two datasets, 4i and scRNAseq, are used, each with multiple treatments. For each treatment, the methods aim to minimize a distance function D(μ, ν) between the untreated (μi) and treated (νi) cell distributions. Lower values indicate better predictions. PrecGD consistently outperforms GD and Te across both datasets and different distance metrics. This highlights the effectiveness of PrecGD in this biological application.

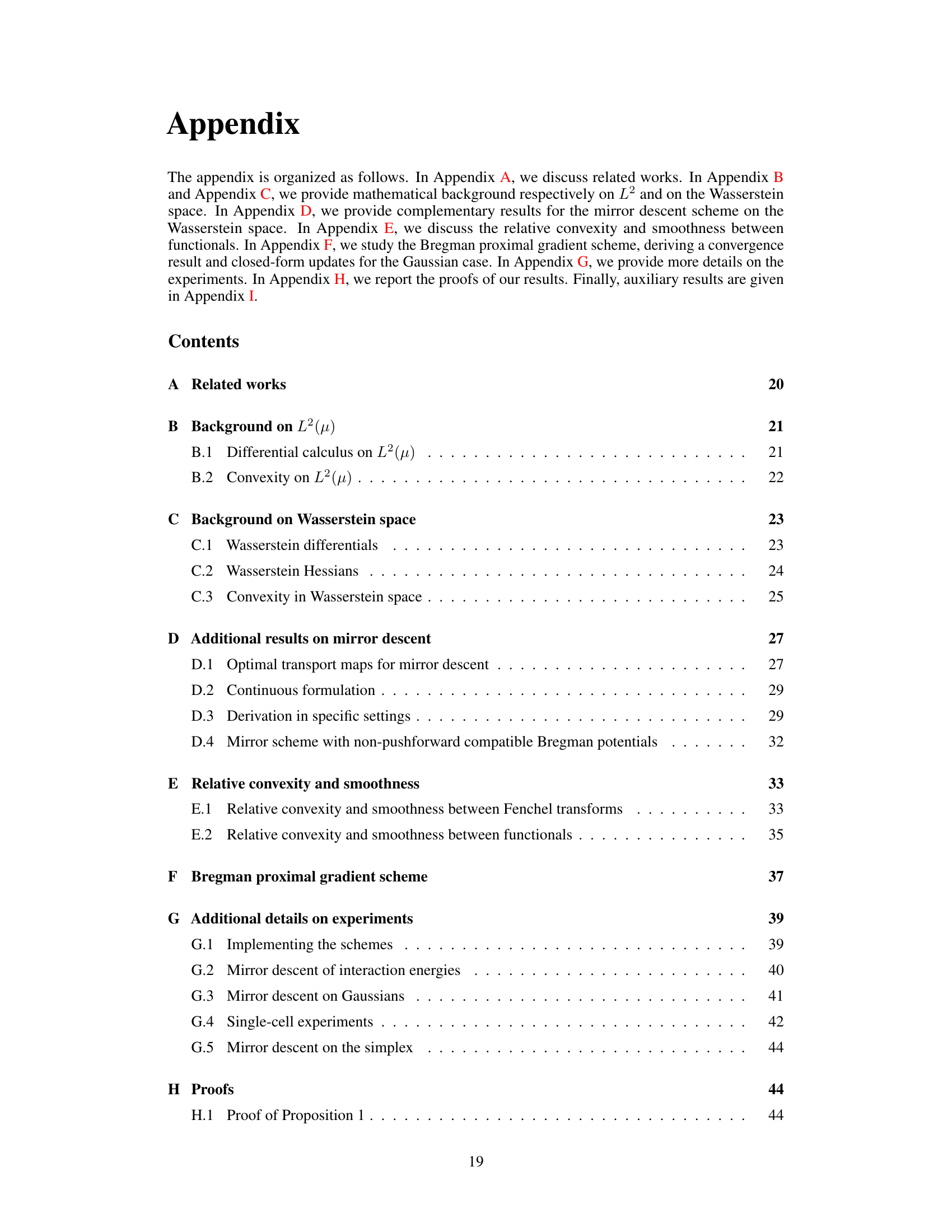

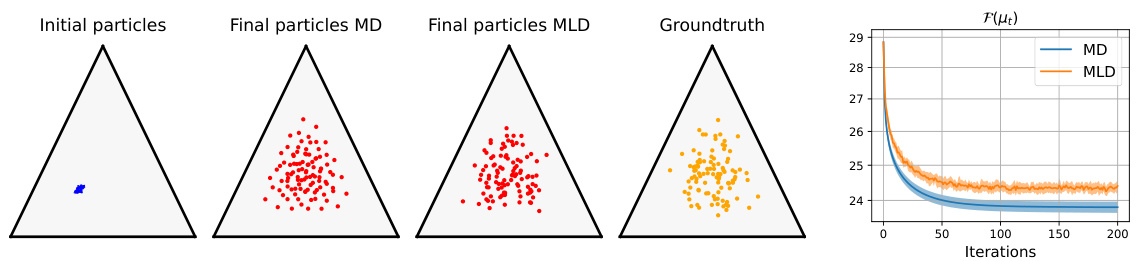

This figure shows the results of sampling from a Dirichlet distribution using two different methods: Mirror Descent (MD) and Mirror Langevin (MLD). The left panel displays the initial particle distribution (blue), the final particle distribution after MD (red), and the final particle distribution after MLD (red). The right panel shows the evolution of the objective function (KL divergence) over 200 iterations for both methods. MLD shows better convergence towards the true distribution than MD.

Full paper#