↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many concerns exist regarding the potential harm of highly agentic AI systems. A key aspect of agency is goal-directed behavior, which is currently difficult to quantify effectively. Existing methods for measuring goal-directedness have limitations, such as reliance on specific assumptions or inability to handle arbitrary utility functions.

This paper introduces a novel formal measure called Maximum Entropy Goal-Directedness (MEG) to address these issues. MEG quantifies goal-directedness based on how well a system’s behavior can be predicted by the assumption that it is optimizing a given utility function. The authors provide algorithms to compute MEG under various settings, including those with or without a known utility function. Experimental evaluations validate the effectiveness of the proposed method.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for AI safety researchers as it provides a formal framework for measuring goal-directedness in AI systems. This addresses a critical gap in current research, enabling more robust evaluation of AI agents and a better understanding of potential risks. It also opens new avenues for research in inverse reinforcement learning and the development of safer AI systems.

Visual Insights#

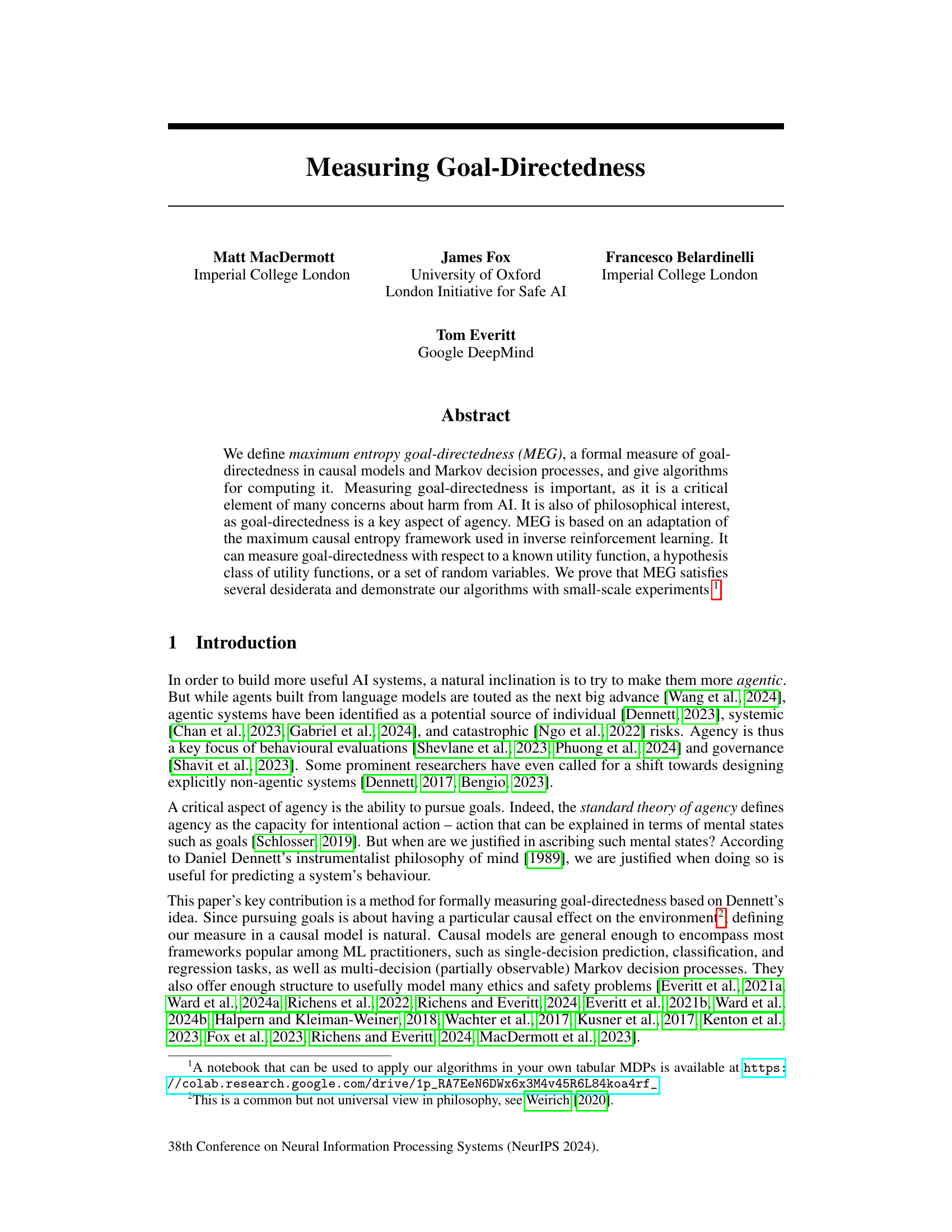

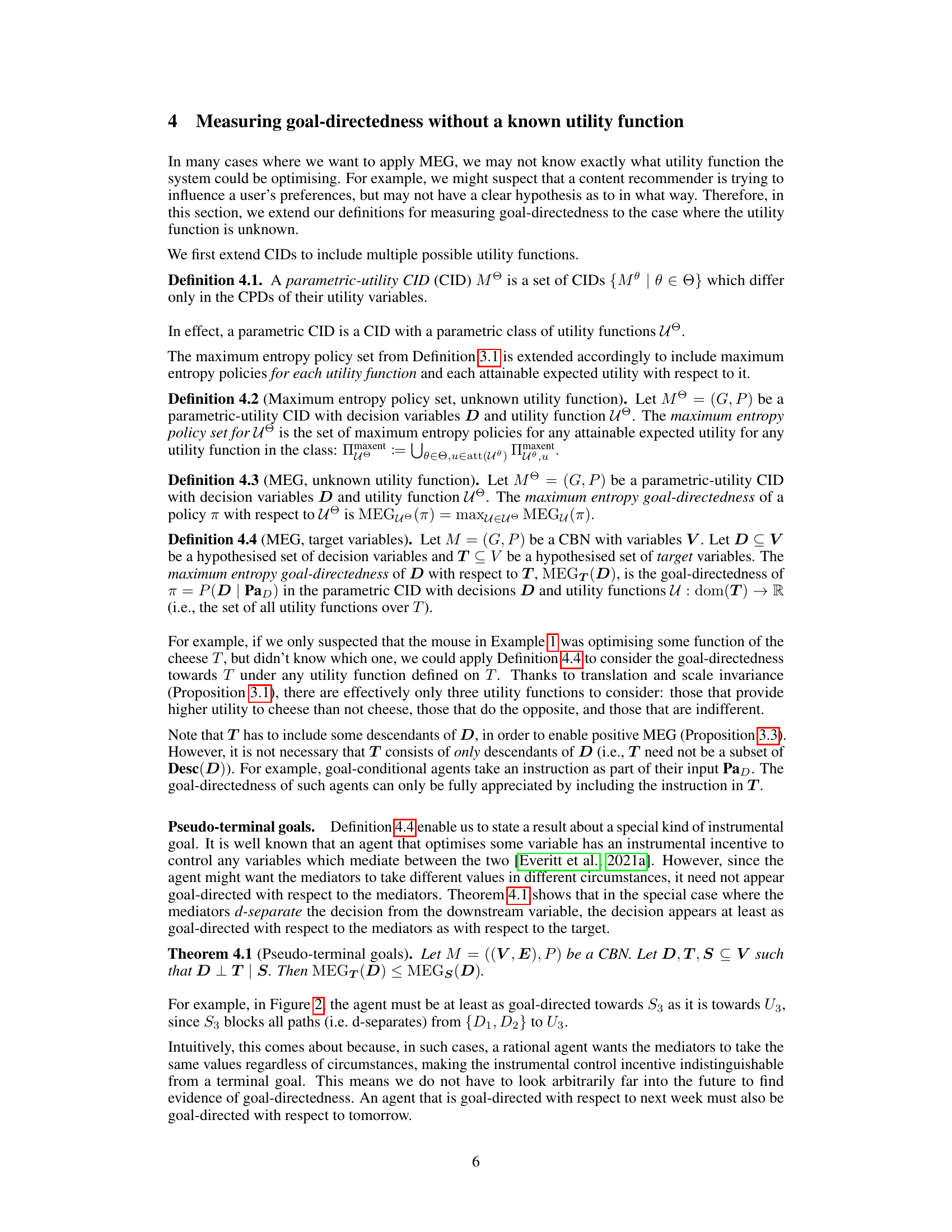

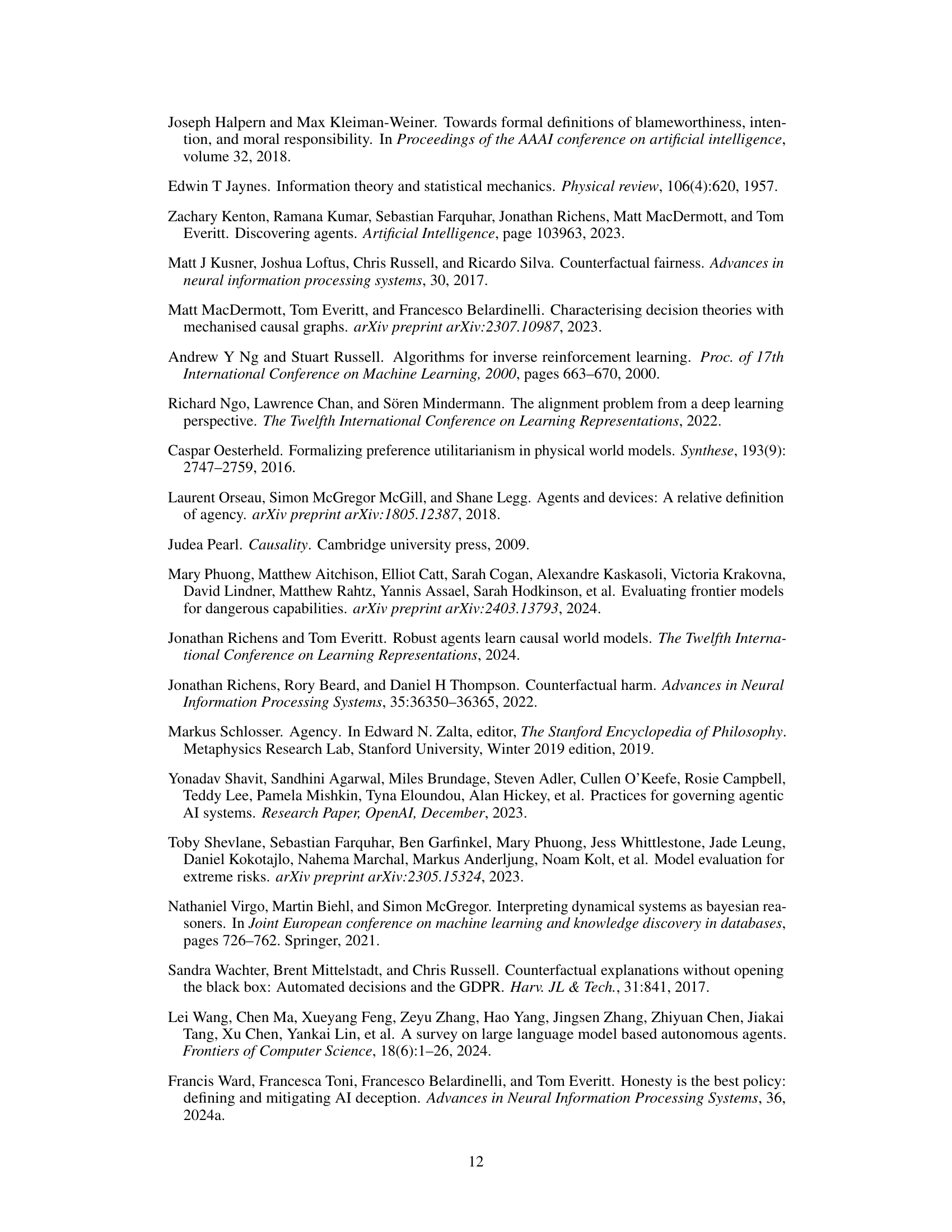

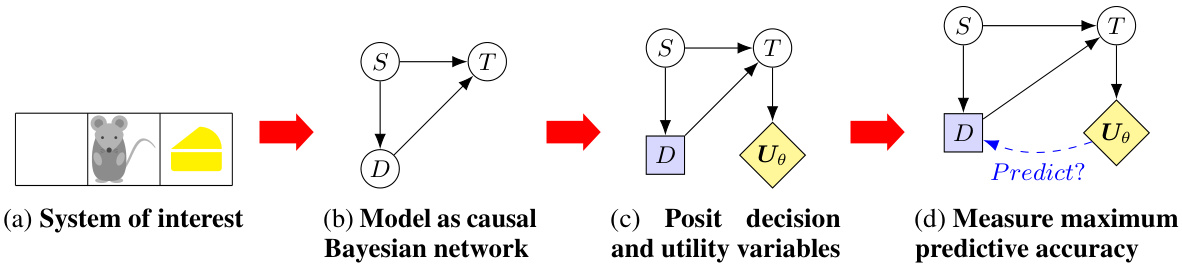

This figure illustrates the four steps involved in computing the maximum entropy goal-directedness (MEG). (a) shows a system of interest. (b) models the system as a causal Bayesian network. (c) posits decision and utility variables. (d) measures maximum predictive accuracy to quantify goal-directedness. The example depicts a mouse choosing between two directions, one with cheese and one without. The MEG calculation assesses how well the mouse’s choices are predicted by assuming it’s acting to maximize utility (obtaining cheese).

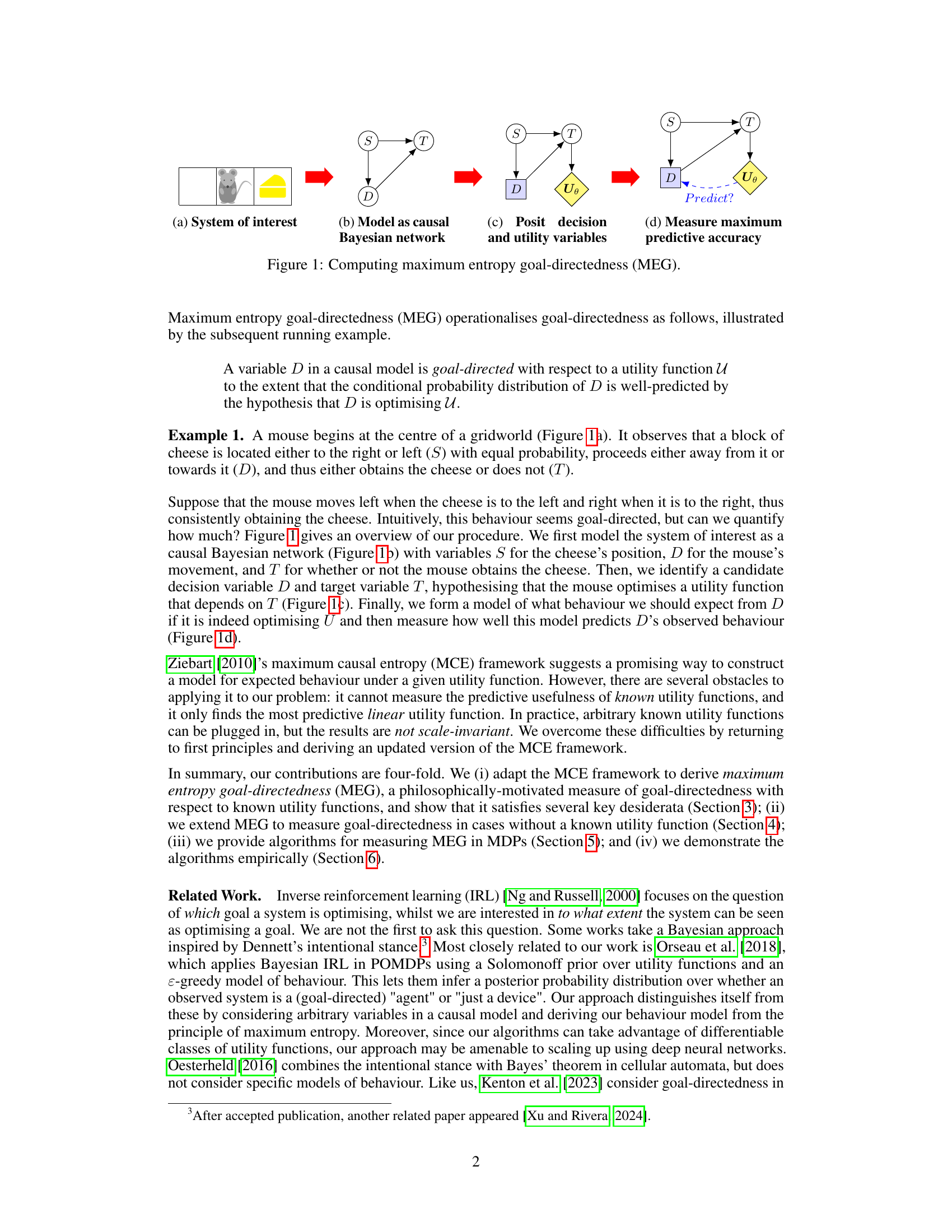

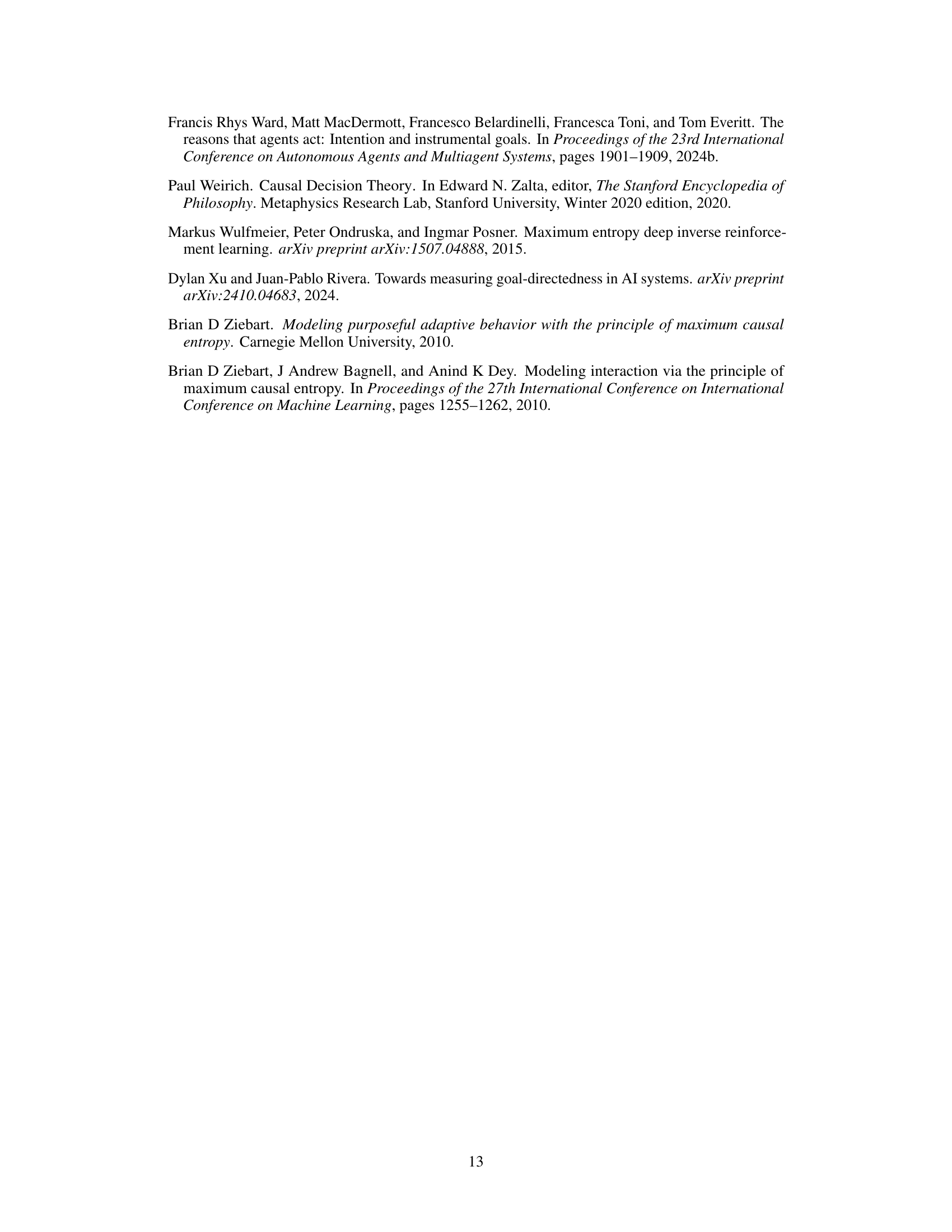

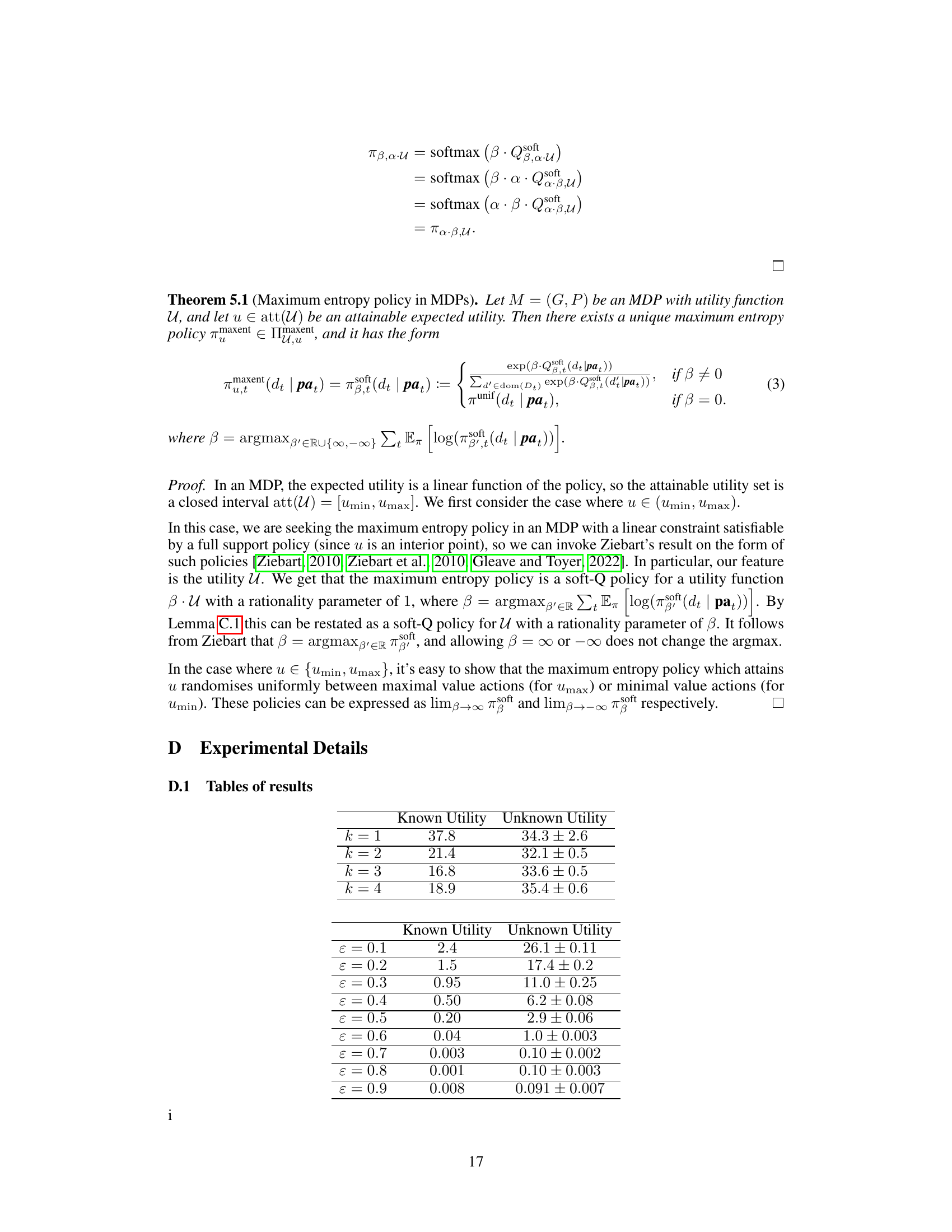

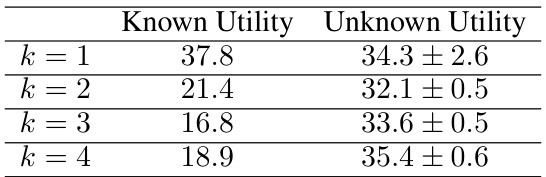

This table presents the results of two experiments conducted to measure known-utility MEG (maximum entropy goal-directedness) with respect to the environment reward function and unknown-utility MEG with respect to a hypothesis class of utility functions. The experiments involved the CliffWorld environment, where the agent aims to reach the top right while avoiding a cliff along the top row. The first experiment varied the level of randomness in the agent’s policy (ε-greedy) and measured MEG for different levels of randomness. The second experiment kept the agent’s policy optimal but changed the difficulty of the task by altering the length of the goal region (k). For each condition, the table reports the average known-utility MEG (single value), and the average unknown-utility MEG (with standard deviation) across multiple runs.

In-depth insights#

Goal-Directedness Metric#

A crucial aspect of assessing the safety and capabilities of artificial intelligence is the capacity to measure its goal-directedness. A robust “Goal-Directedness Metric” should move beyond simple binary classifications of agentic vs. non-agentic systems. Instead, it needs to offer a continuous, nuanced measure that captures the degree to which an AI system’s behavior aligns with a hypothesized utility function. This means considering factors like the predictive accuracy of attributing goals to the AI, the variety of possible utility functions, and the causal relationships between actions and outcomes. A strong metric should also be invariant to certain transformations of the utility function (e.g., scaling or shifting) and account for the complexity of the AI’s decision-making process. Furthermore, a useful metric would need to be practically applicable across diverse AI architectures and readily computable, avoiding limitations that hinder widespread adoption and real-world impact. Finally, philosophical considerations regarding the nature of agency should underpin the development of such a metric, ensuring alignment with our broader understanding of goal-oriented behavior.

Causal Model Approach#

A causal model approach offers a powerful framework for analyzing complex systems by explicitly representing cause-and-effect relationships. This approach is particularly valuable when dealing with interventions and counterfactuals, allowing researchers to understand how changes in one variable might affect others. By using causal models, we can move beyond simple correlations to establish true causal relationships, improving the accuracy and reliability of our inferences. Furthermore, causal models facilitate a deeper understanding of mechanisms, going beyond simple associations by explaining why certain effects occur. This mechanistic insight is crucial for designing effective interventions and predicting the outcomes of complex scenarios, making causal modeling a valuable tool for various domains such as healthcare, economics and policy making. However, building accurate causal models can be challenging, especially when dealing with hidden confounders and complex feedback loops. Careful consideration of model assumptions and limitations is therefore critical for reliable results. The choice of appropriate causal discovery methods and the validation of resulting models are key steps to ensure both robustness and scientific rigor.

MEG Algorithmics#

The heading ‘MEG Algorithmics’ suggests a section detailing the computational methods behind maximum entropy goal-directedness (MEG). This would likely involve a discussion of the algorithms used to calculate MEG, including considerations for both known and unknown utility functions. Key algorithmic aspects might include the adaptation of maximum causal entropy (MCE) frameworks, potentially involving modifications to address limitations of existing MCE approaches. The section could also cover specific implementations, such as applying the algorithms to Markov Decision Processes (MDPs), and would probably include a discussion of the computational complexity and scalability of these methods. Furthermore, details on the use of techniques like soft value iteration or other optimization strategies for finding maximum entropy policies, as well as considerations for approximating or estimating MEG when the utility function is unknown, would be expected. Finally, a discussion of the specific implementation choices, the rationale behind them, and a demonstration of the algorithms’ efficacy, potentially with small-scale experiments, are necessary for a comprehensive treatment of MEG algorithmics.

Empirical Validation#

An empirical validation section in a research paper would rigorously test the proposed methodology, likely Maximum Entropy Goal-Directedness (MEG). This would involve designing experiments to assess MEG’s ability to accurately measure goal-directedness in various scenarios. Key aspects would include the selection of appropriate benchmarks, careful consideration of relevant metrics, and the use of statistically sound methods for evaluating the results. The choice of experimental setups (e.g., simple gridworlds or complex simulations) would be crucial. The results section should clearly demonstrate MEG’s performance compared to existing methods or alternative approaches. A robust empirical validation would bolster the paper’s claims by providing strong quantitative evidence of the method’s reliability, accuracy, and practical usefulness. Limitations of the empirical evaluation would also need to be acknowledged, such as the choice of specific tasks or the scaling behavior of the methodology.

Future Work#

The paper’s discussion of future work is quite promising, focusing on several key areas. Extending MEG to interventional distributions is crucial for improving the measure’s robustness to distributional shifts. This is a significant limitation of the current framework, and addressing it would considerably enhance the measure’s practical applicability. The authors also correctly identify the need for further exploration into mechanistic approaches to assess goal-directedness, suggesting that combining insights from MEG with detailed analyses of system architectures could lead to a more comprehensive understanding of agency. Another important area is scaling MEG to more complex and high-dimensional systems. The computational cost of current algorithms limits their application to relatively simple scenarios. Finally, they suggest integrating MEG with neural network interpretability techniques, measuring goal-directedness with respect to hypotheses about a network’s internal representations. This innovative approach could provide powerful tools for analyzing and understanding the behavior of complex AI agents.

More visual insights#

More on figures

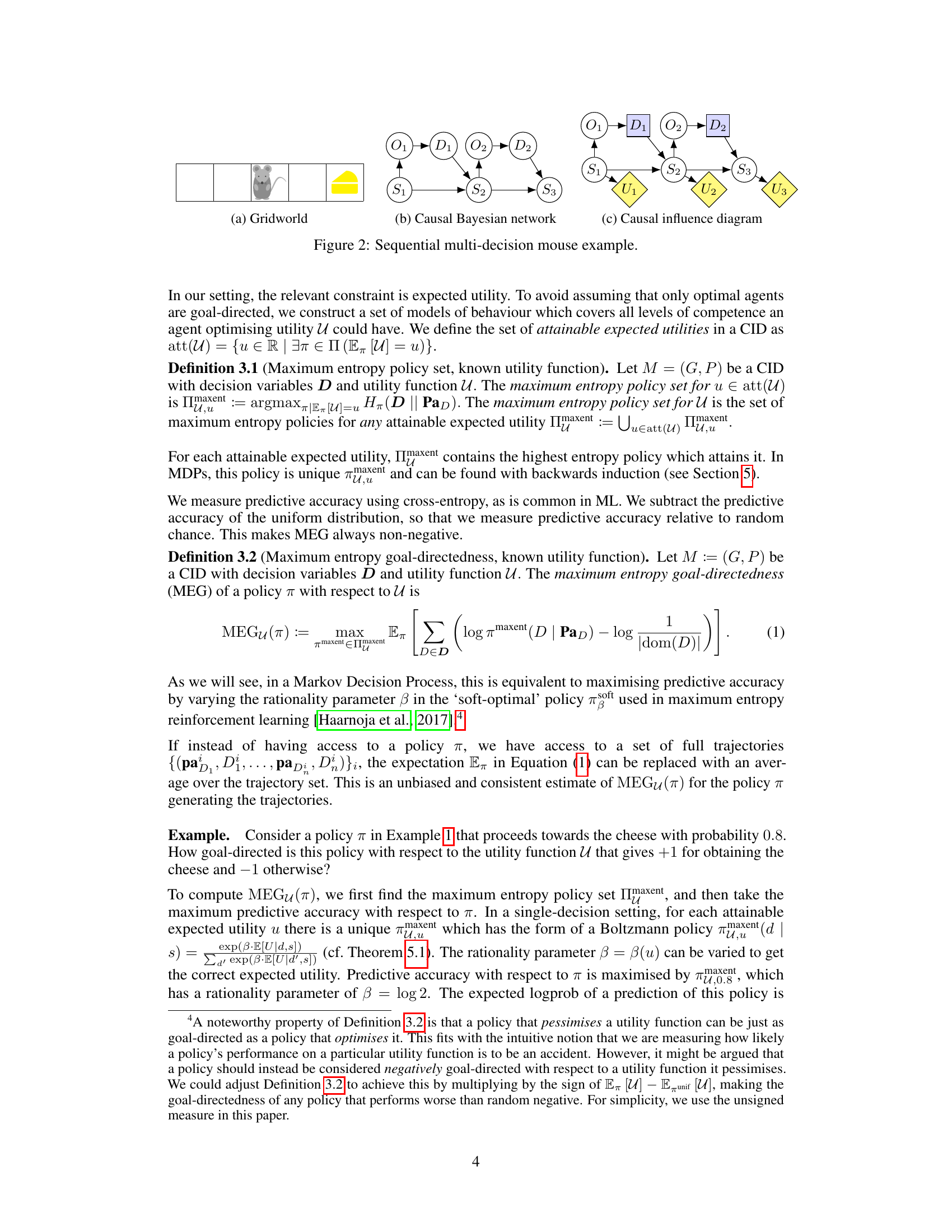

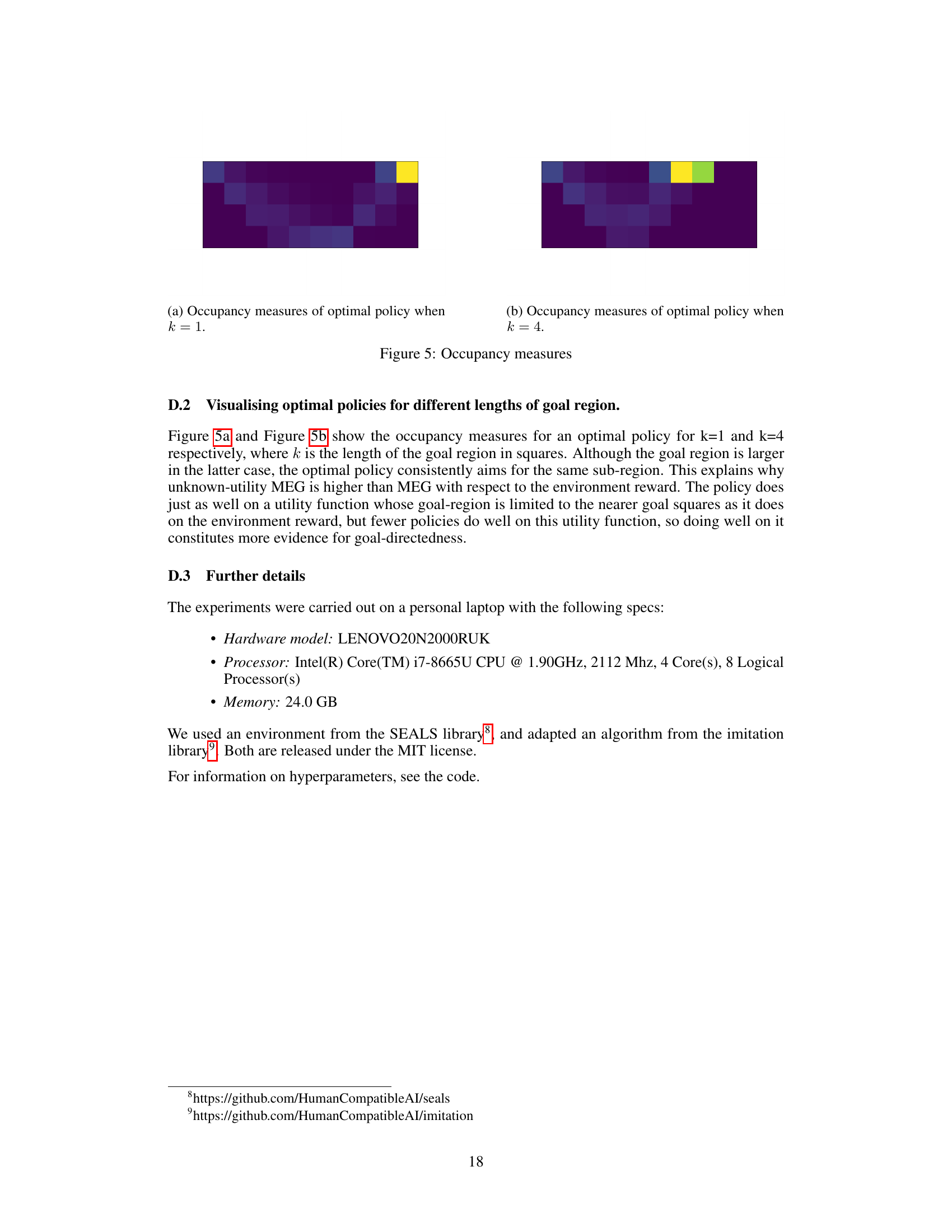

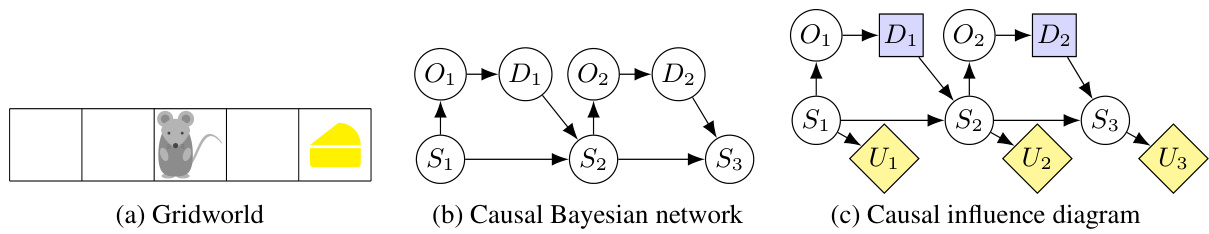

This figure illustrates an example of a sequential multi-decision problem. (a) shows the gridworld environment. The mouse starts in the center and must decide whether to move left or right at each time step. (b) depicts this as a causal Bayesian network, with nodes representing the cheese’s location, the mouse’s observations and decision, and whether the mouse obtained the cheese. (c) shows this as a causal influence diagram, with utility nodes added to represent the utility of each outcome.

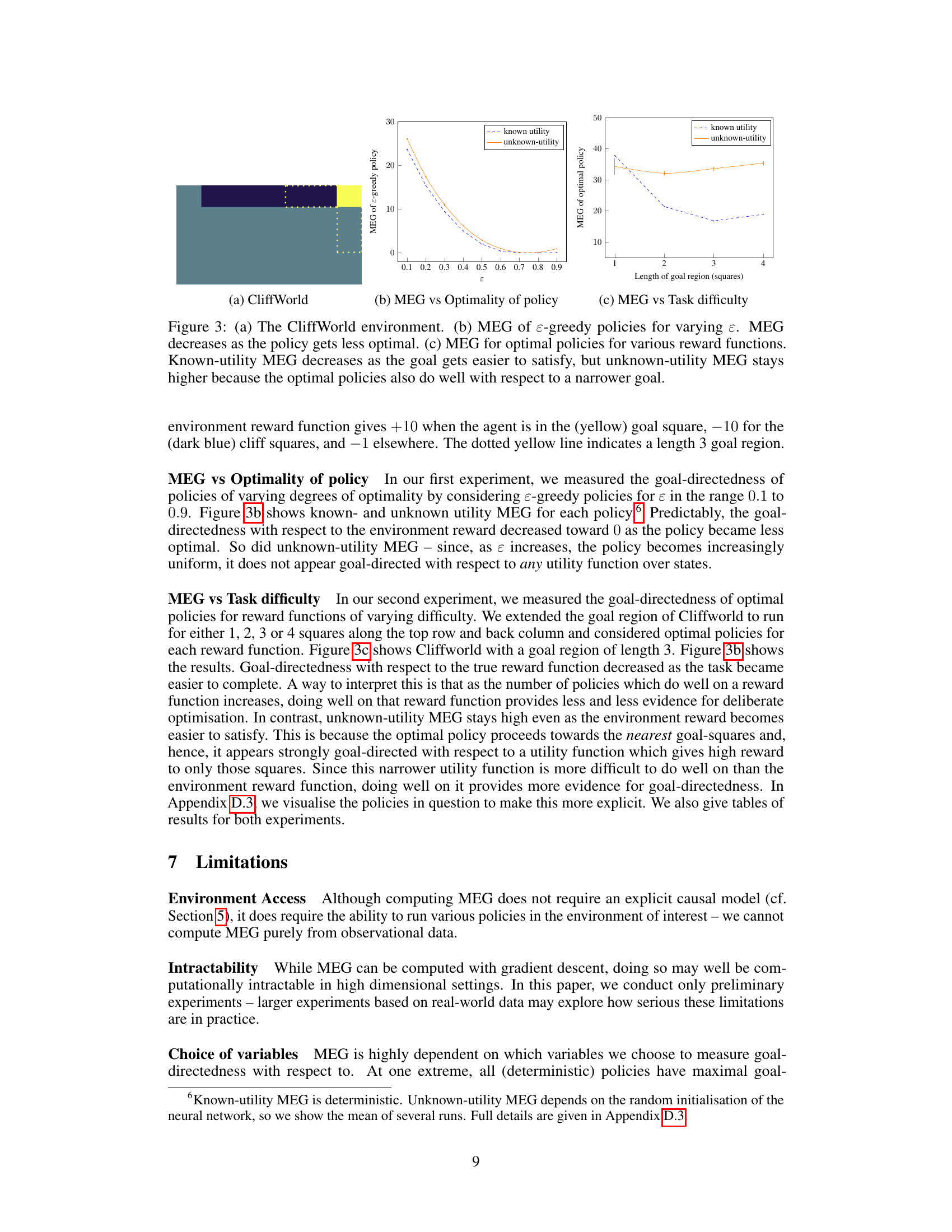

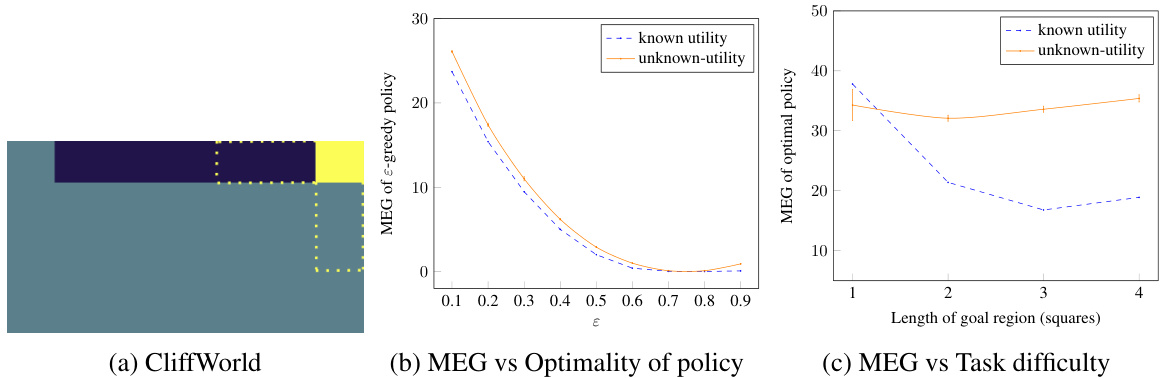

This figure presents results from two experiments conducted using the CliffWorld environment. The first experiment (b) shows how the maximum entropy goal-directedness (MEG) changes for ε-greedy policies with varying ε values (exploration-exploitation trade-off). As expected, MEG decreases as the policy becomes less optimal (more random). The second experiment (c) examines how MEG varies for optimal policies under different reward functions, each representing a task of varying difficulty. It shows that known-utility MEG (MEG with respect to a known reward function) decreases as the task gets easier (the goal region becomes larger), while the unknown-utility MEG (MEG considering a family of utility functions) remains relatively higher. This is because optimal policies that perform well on the easier task also perform well on more specific, narrower utility functions, thereby maintaining a higher MEG in the unknown utility case.

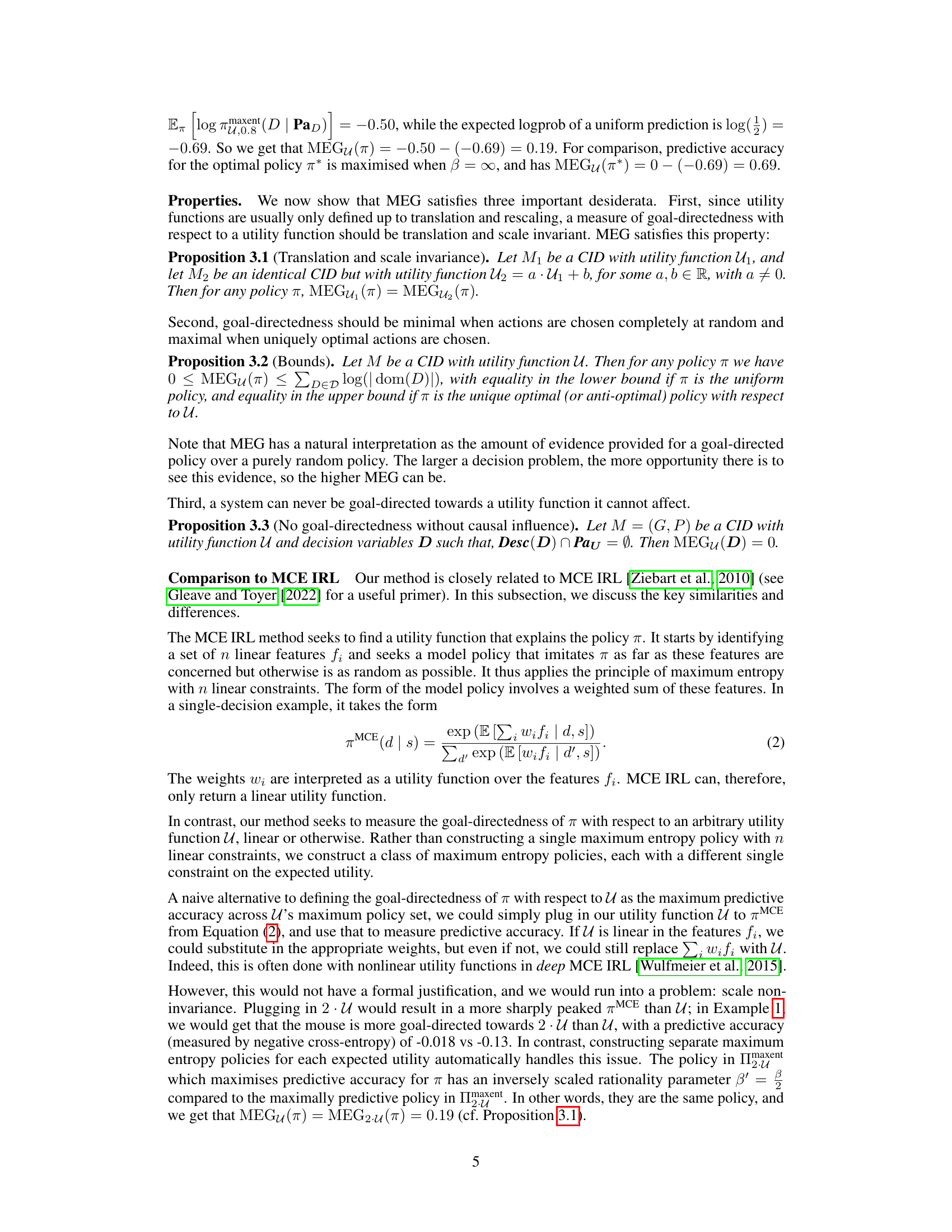

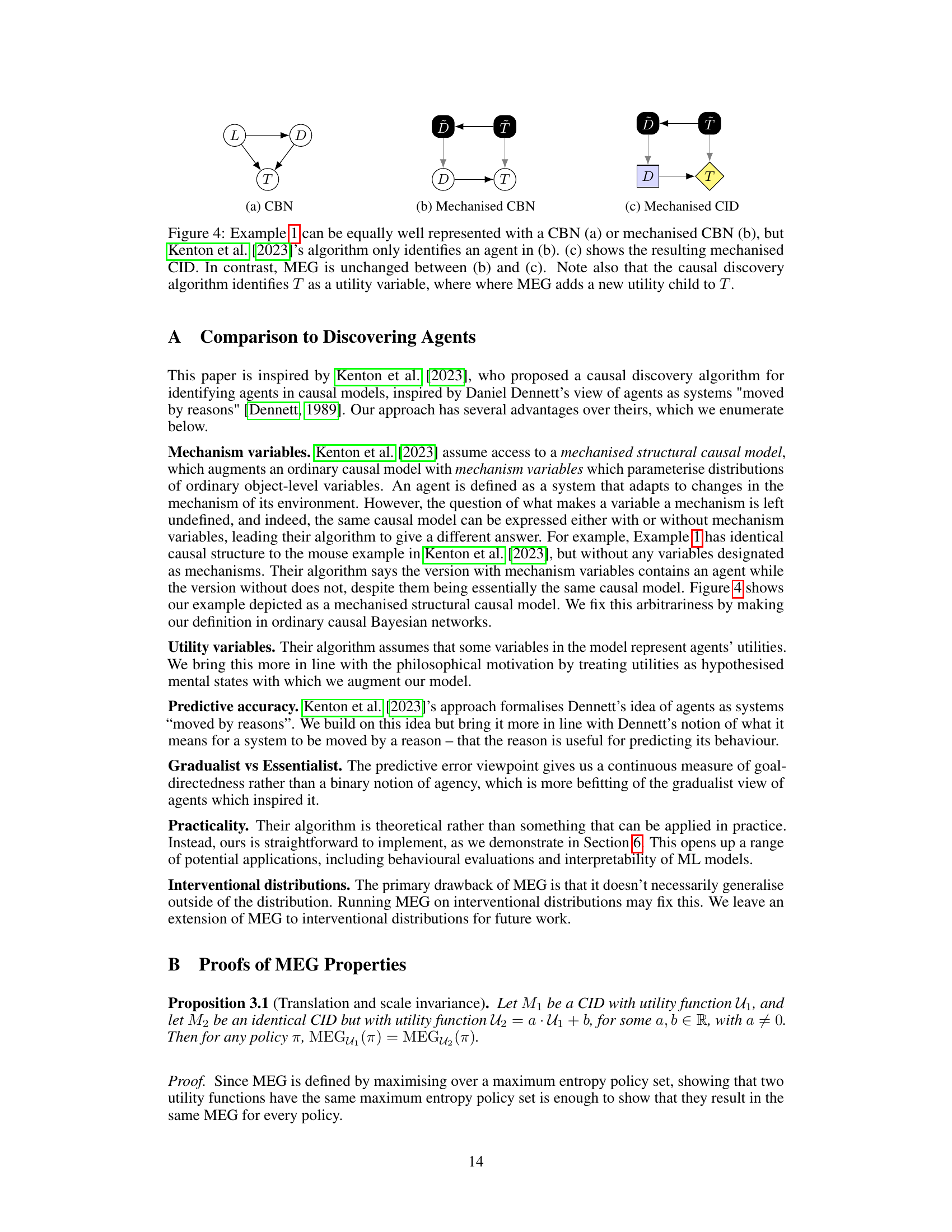

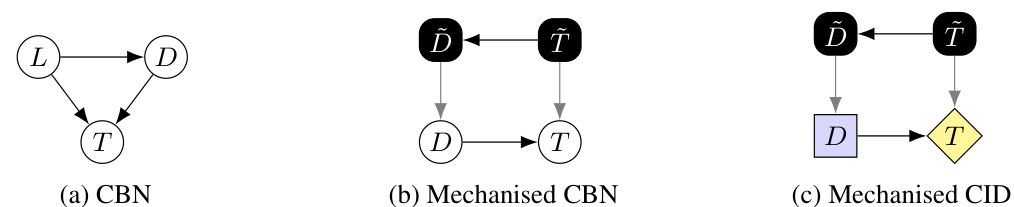

This figure compares three different graphical model representations of Example 1 from the paper. Panel (a) shows a standard causal Bayesian network (CBN). Panel (b) demonstrates a ‘mechanised’ CBN, which adds additional variables representing mechanisms. Kenton et al.’s method would only identify an agent in the mechanised version. Panel (c) presents a ‘mechanised’ causal influence diagram (CID) that includes utility variables. The paper highlights that MEG (Maximum Entropy Goal-Directedness), unlike Kenton et al.’s method, remains consistent across these different representations.

This figure shows three subplots related to the CliffWorld environment experiments. (a) shows the environment setup. (b) shows how MEG (maximum entropy goal-directedness) values decrease as the policies become less optimal (using epsilon-greedy policies with varying epsilon values). (c) demonstrates the relationship between MEG and task difficulty (different reward functions with varying lengths of goal regions). This subplot highlights that known-utility MEG decreases as the task becomes easier, but unknown-utility MEG remains higher because optimal policies perform well even with narrower goal definitions.

Full paper#