↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world problems involve finding the optimal solution under certain constraints, a field known as combinatorial optimization. These problems are often computationally hard, particularly those belonging to the NP-hard complexity class. Traditional approaches struggle with either computational speed or solution accuracy. Machine learning, specifically neural networks, offers a potential solution but often lacks the guarantees of optimality found in classic algorithms.

This paper introduces OptGNN, a novel graph neural network (GNN) architecture that addresses these challenges. OptGNN is designed to learn powerful approximation algorithms derived from semidefinite programming (SDP), a technique that provides strong theoretical guarantees for the quality of solutions. The researchers demonstrate OptGNN’s effectiveness on several benchmark problems, showing that it achieves high-quality approximate solutions with strong empirical results compared to other methods. Furthermore, they show OptGNN can produce bounds on the optimal solution, bridging the gap between machine learning and traditional optimization approaches.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in combinatorial optimization and machine learning as it bridges the gap between theoretical optimality and practical efficiency. It introduces a novel approach by leveraging semidefinite programming (SDP) within a graph neural network architecture. This opens new avenues for designing efficient and effective neural network algorithms for solving various NP-hard problems. Its findings provide insights into neural network capabilities and have the potential to impact diverse fields like operations research, computer science and AI.

Visual Insights#

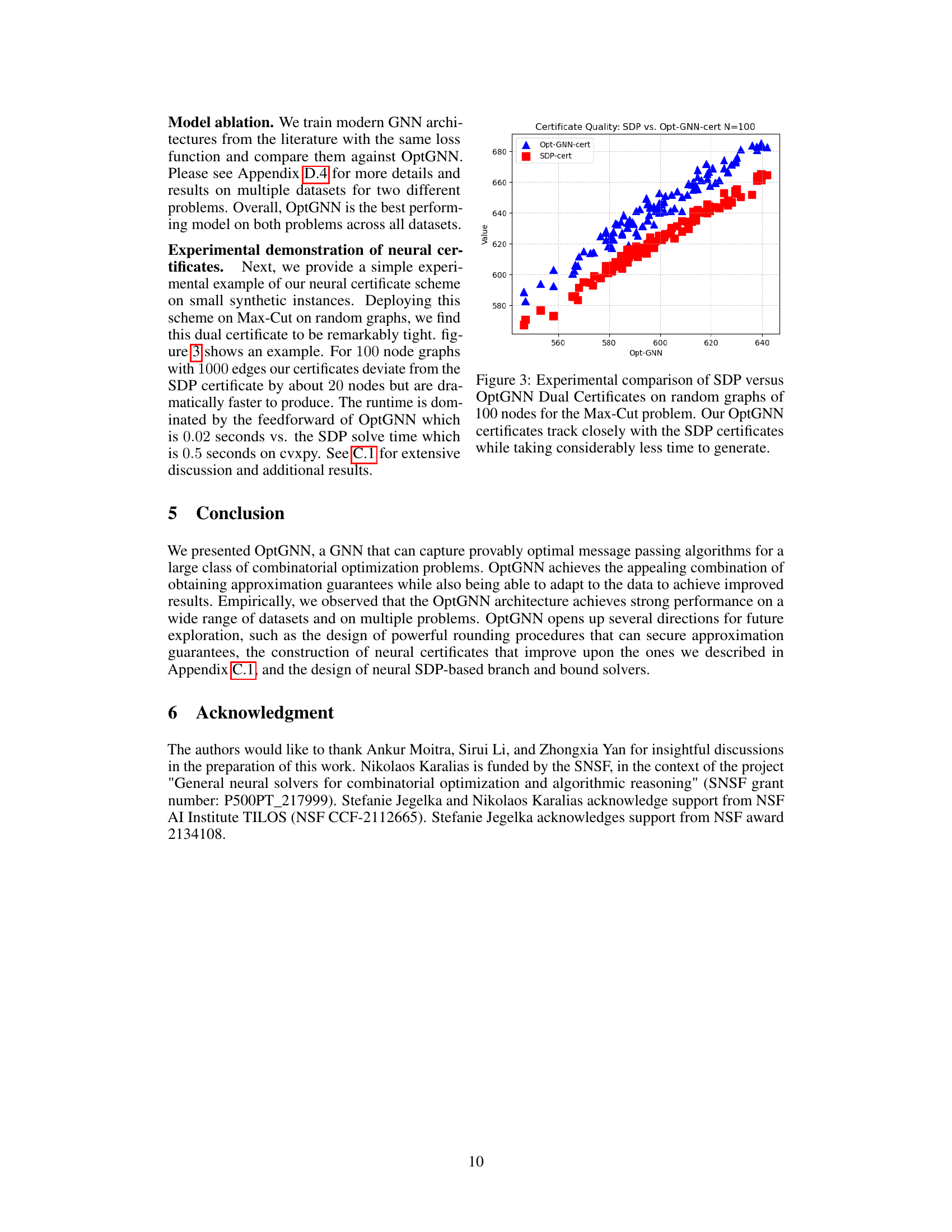

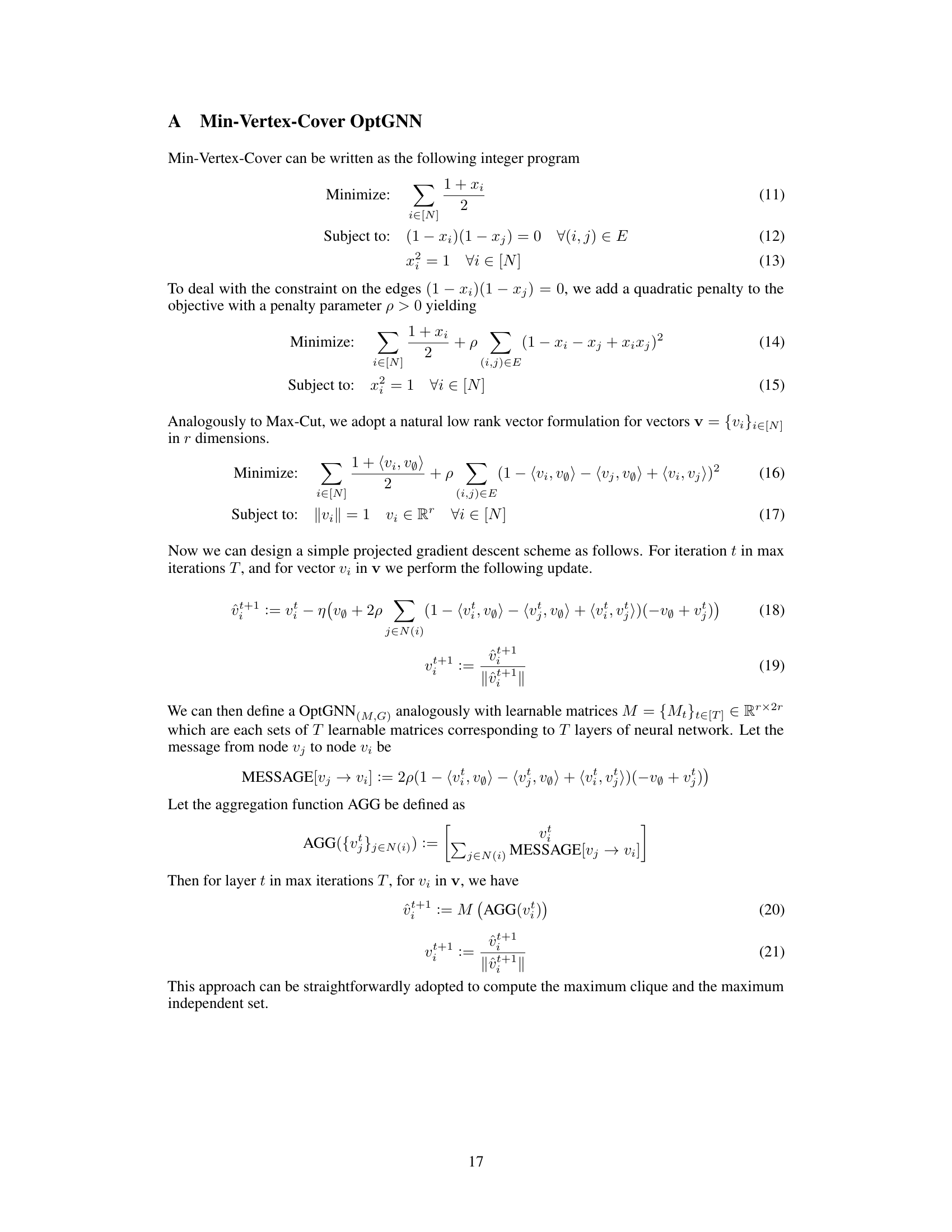

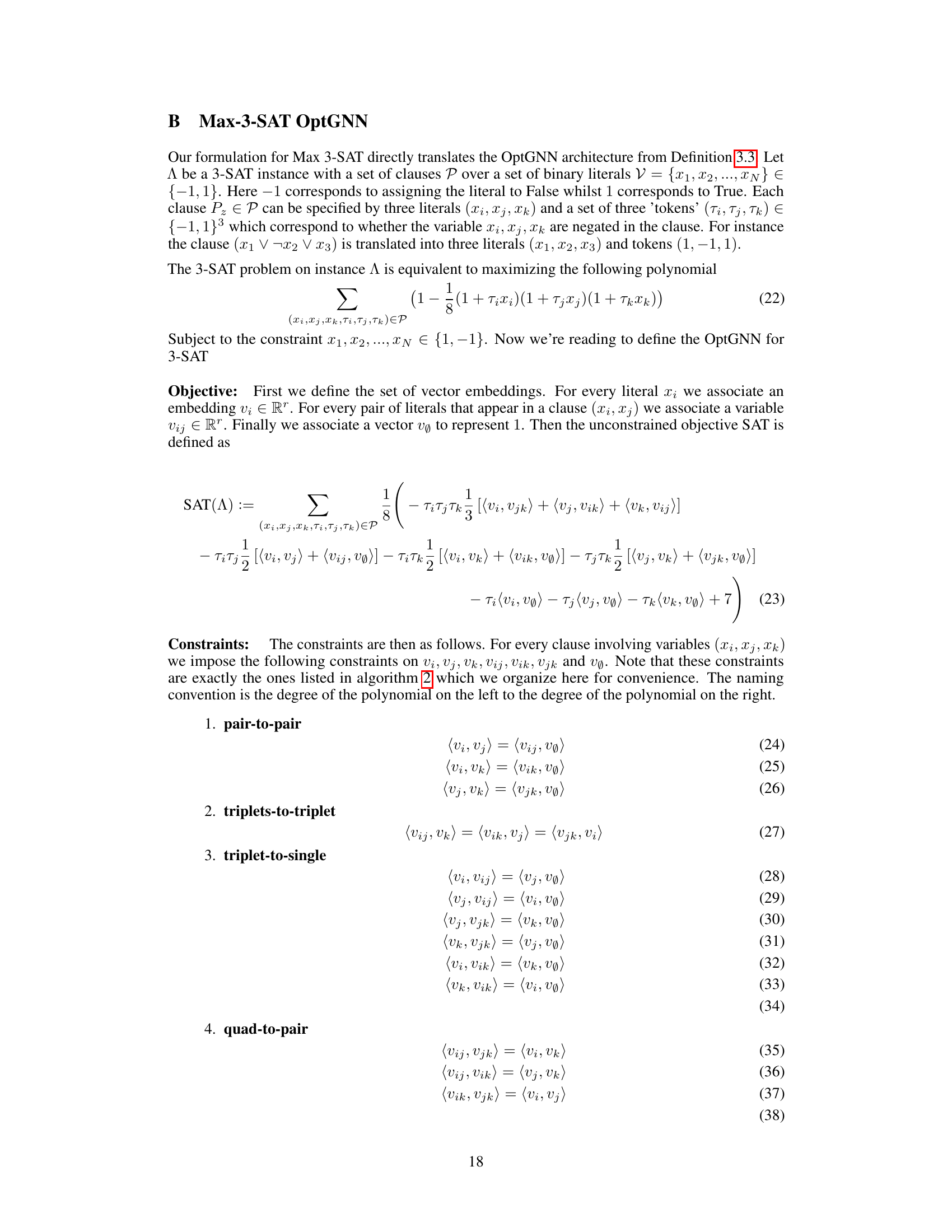

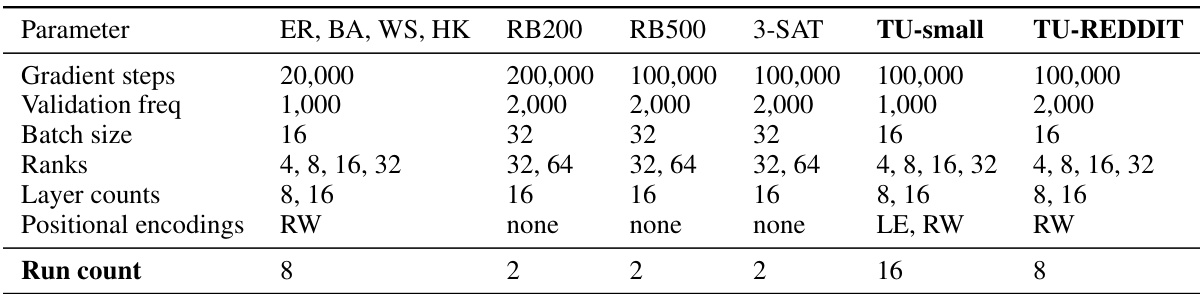

This figure illustrates the OptGNN architecture. The training phase shows message-passing updates on the graph to produce node embeddings which are then used to minimize a penalized loss function. The inference phase shows that these embeddings are then rounded via a randomized method to yield a final solution.

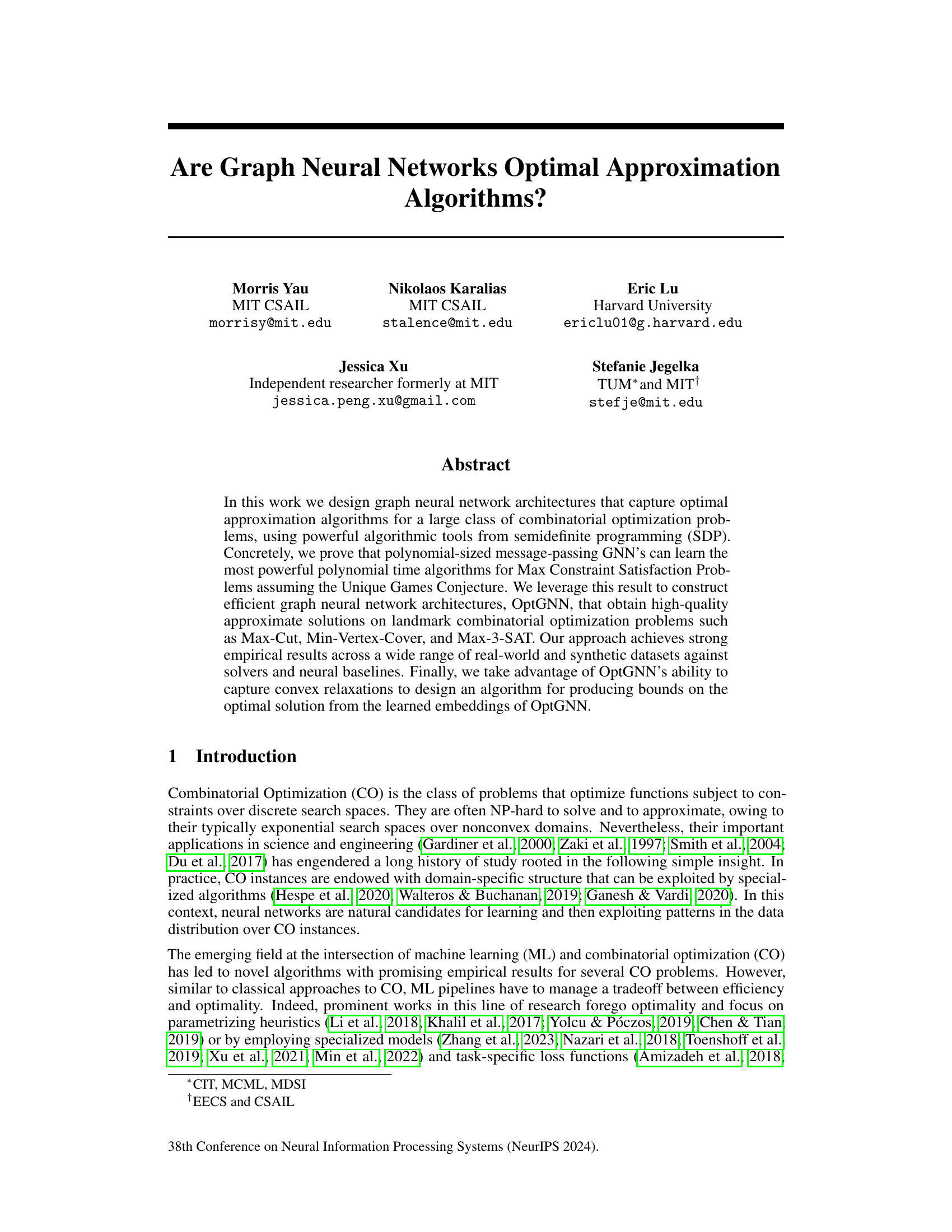

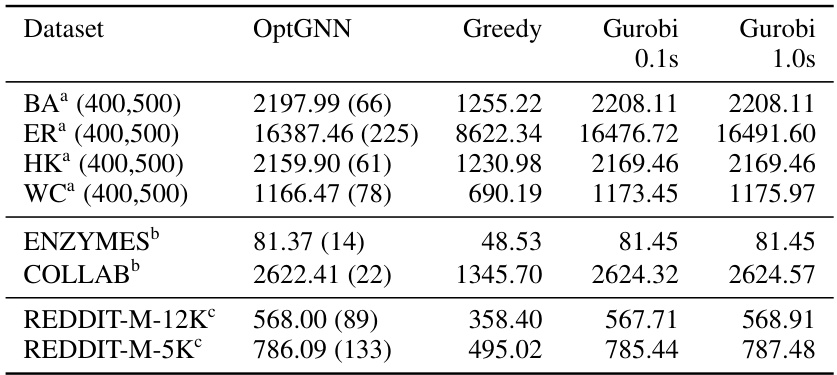

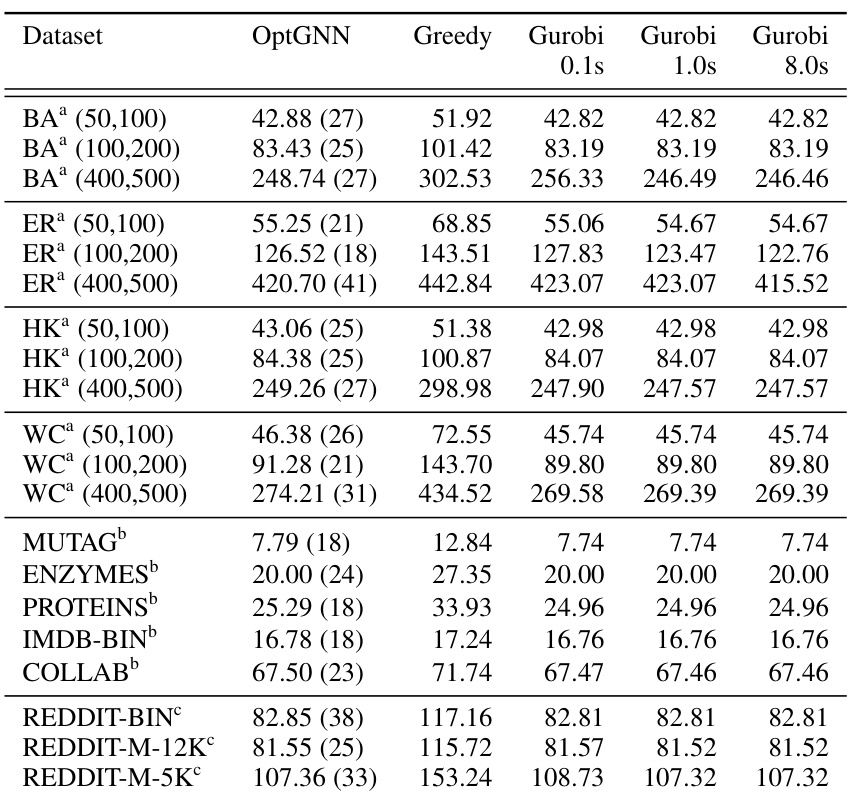

This table compares the performance of three different algorithms (OptGNN, Greedy, and Gurobi) on the Maximum Cut problem across various datasets. OptGNN’s runtime is also provided in milliseconds. Higher scores indicate better performance.

In-depth insights#

OptGNN Architecture#

The OptGNN architecture is a novel approach to solving combinatorial optimization problems using graph neural networks (GNNs). It leverages the power of semidefinite programming (SDP) relaxations, which are known to provide strong approximation guarantees for many NP-hard problems, but are often computationally expensive. OptGNN cleverly embeds a polynomial-time message-passing algorithm, inspired by SDP solvers, into a GNN architecture. This allows OptGNN to learn efficient approximations to optimal SDP solutions. The architecture employs learnable parameters to fine-tune its message-passing mechanisms, adapting to the specific structure and characteristics of different combinatorial problems and datasets. This makes it highly adaptable to various scenarios. Importantly, the learned embeddings produced by OptGNN can be used to generate certificates that bound the optimal solution, adding a degree of theoretical grounding and trustworthiness to the results. The authors demonstrate empirically the architecture’s effectiveness compared to existing GNN-based approaches and traditional heuristics, highlighting its promising potential as a general-purpose and efficient tool for combinatorial optimization.

SDP Relaxation#

SDP relaxation is a crucial technique in combinatorial optimization for tackling NP-hard problems. It involves reformulating a discrete optimization problem as a semidefinite program (SDP), which is a type of convex optimization problem that can be solved efficiently. The SDP relaxation relaxes the integrality constraints of the original problem, allowing for the identification of an upper bound (for maximization problems) or lower bound (for minimization problems) on the optimal solution. While the SDP solution itself might not be integral, it provides a valuable approximation that can be rounded to obtain a feasible solution for the original problem. The quality of the approximation depends on the integrality gap of the SDP relaxation, which measures the difference between the optimal SDP solution and the optimal integral solution. Techniques like randomized rounding are often used to convert the relaxed SDP solution into an approximate solution for the original discrete problem. Understanding the integrality gap is vital in assessing the effectiveness of SDP relaxation for specific problem instances, and various methods exist to improve this gap. Ultimately, the use of SDP relaxation represents a powerful tool in the approximation algorithms arsenal, enabling the development of high-quality approximate solutions for numerous computationally intractable problems.

Empirical Results#

An ‘Empirical Results’ section in a research paper would ideally present a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed approach. It should begin with a clear description of the datasets used, highlighting their characteristics and suitability for evaluating the specific claims of the research. Then, the results should be presented clearly, using appropriate visualization techniques such as tables and graphs. It’s crucial to include relevant metrics to demonstrate performance in a quantifiable manner and compare against strong baselines. The discussion should go beyond simply stating the results; it needs to analyze and interpret them. Statistical significance should be addressed, along with a discussion of potential sources of error and limitations. Finally, ablation studies and out-of-distribution testing would provide crucial insights on the robustness and generalizability of the method. The overall goal is to present a convincing and rigorous evaluation that convincingly supports the paper’s claims.

Neural Certificates#

The concept of “Neural Certificates” in the context of a research paper focusing on graph neural networks (GNNs) for combinatorial optimization problems is intriguing. It suggests a novel approach to verifying the quality of solutions obtained by GNNs, moving beyond simple empirical evaluations. The core idea is to leverage the learned representations within the GNN to produce a certificate, a mathematical proof or a strong bound on the optimality of the solution. This certificate, unlike traditional methods, would be generated directly from the neural network’s output, thereby integrating the verification process into the model itself. This approach is particularly valuable when dealing with NP-hard problems where finding the absolute optimal solution is computationally intractable. A key benefit is the potential for faster verification compared to existing methods, especially when dealing with large instances, as the GNN-based certificate could be computationally cheaper to generate than solving the problem from scratch. The effectiveness of neural certificates depends on the GNN’s ability to accurately learn the problem structure and its optimal approximation algorithm. This is where rigorous theoretical analysis is crucial, requiring proof of the certificate’s validity. A limitation might be the tightness of the bound, as the certificate may not always provide the exact optimal solution but rather a near-optimal range. The computational cost of producing these certificates should be investigated thoroughly, balancing the speed improvements against potential limitations in the tightness of the guarantee. Overall, “Neural Certificates” represents a promising direction for research at the intersection of GNNs and combinatorial optimization, bridging the gap between efficiency and verification.

Future Directions#

The research paper explores the use of graph neural networks (GNNs) to approximate optimal solutions for combinatorial optimization problems. Future directions could involve improving the rounding procedures to provide stronger approximation guarantees, perhaps by incorporating techniques from the field of approximation algorithms or by learning more sophisticated rounding schemes within the GNN framework. The development of neural certificates that offer tighter bounds on the optimal solution is another promising area. This could involve exploring tighter convex relaxations or developing novel methods for deriving bounds directly from the learned GNN embeddings. Further research might investigate more efficient training techniques. The paper could be improved by studying the impact of hyperparameters and architectural choices on the model’s generalization ability and exploring alternative training strategies, including self-supervised methods or reinforcement learning. Finally, the authors could explore the application of the OptGNN approach to additional combinatorial optimization problems or extend their analysis to different types of graph structures or data distributions. Addressing the limitations of the current OptGNN, such as handling graphs with varying degrees or noise in the data, would be a significant step forward. The theoretical analysis could be deepened by relaxing the Unique Games Conjecture or exploring broader theoretical frameworks for understanding the approximation capabilities of GNNs. In summary, the potential future of this work is very rich indeed.

More visual insights#

More on figures

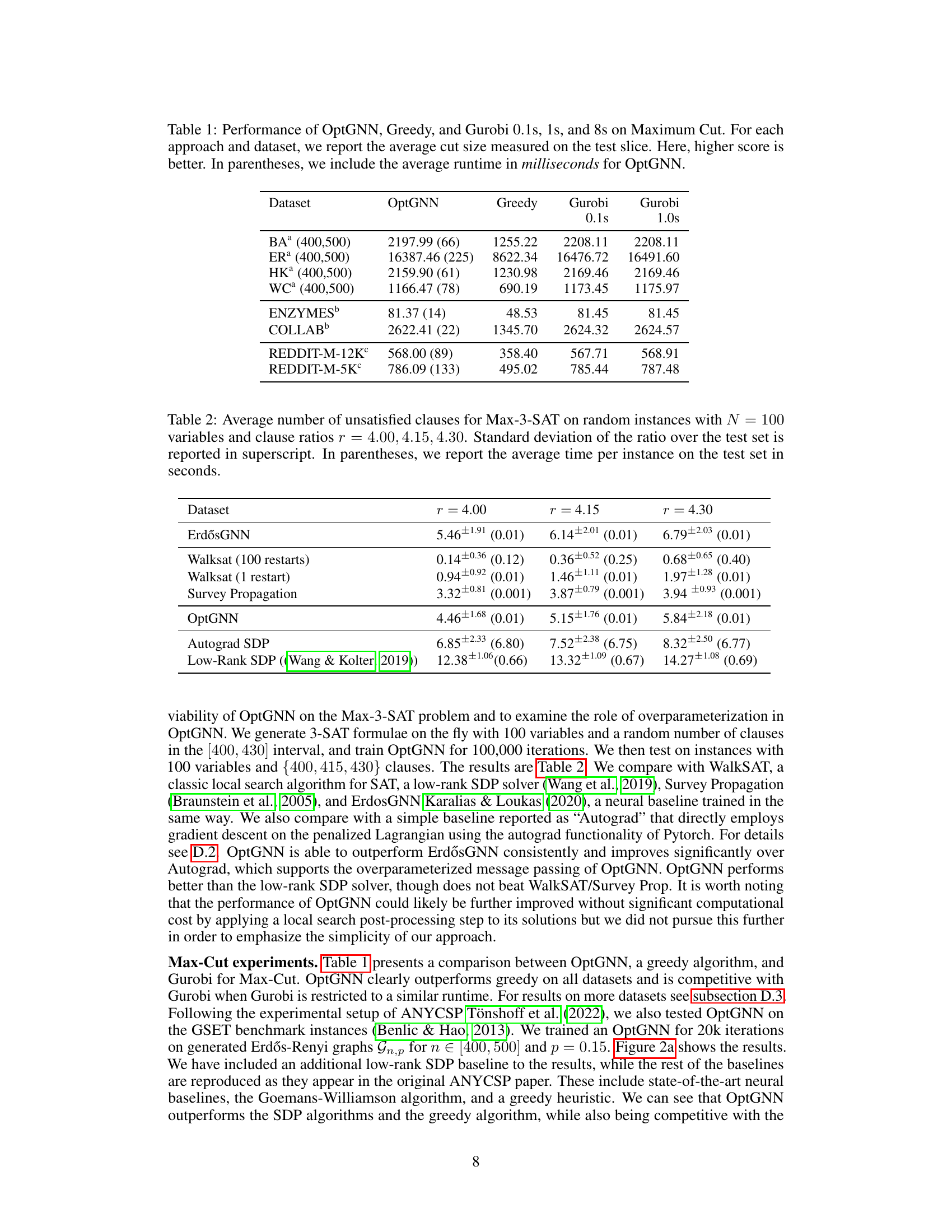

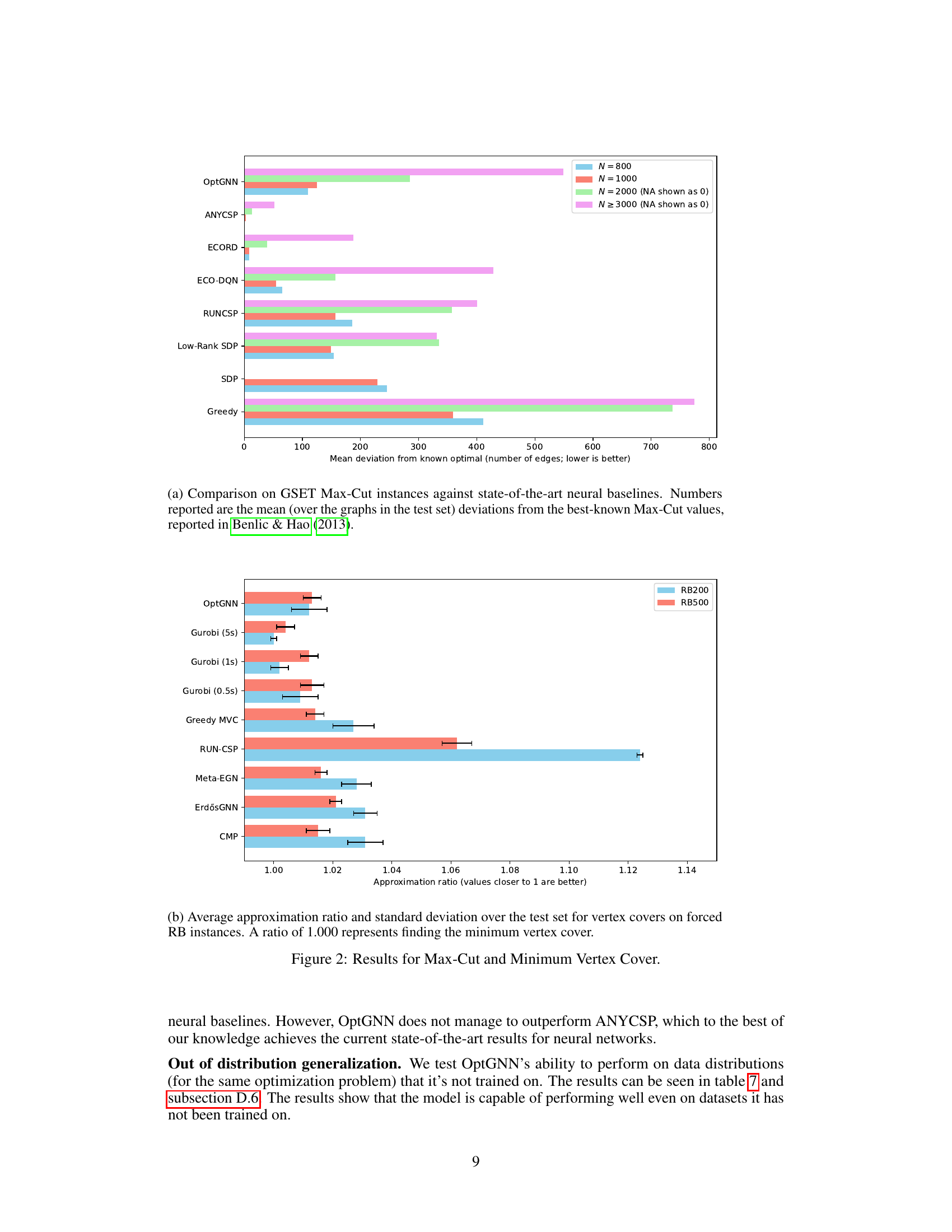

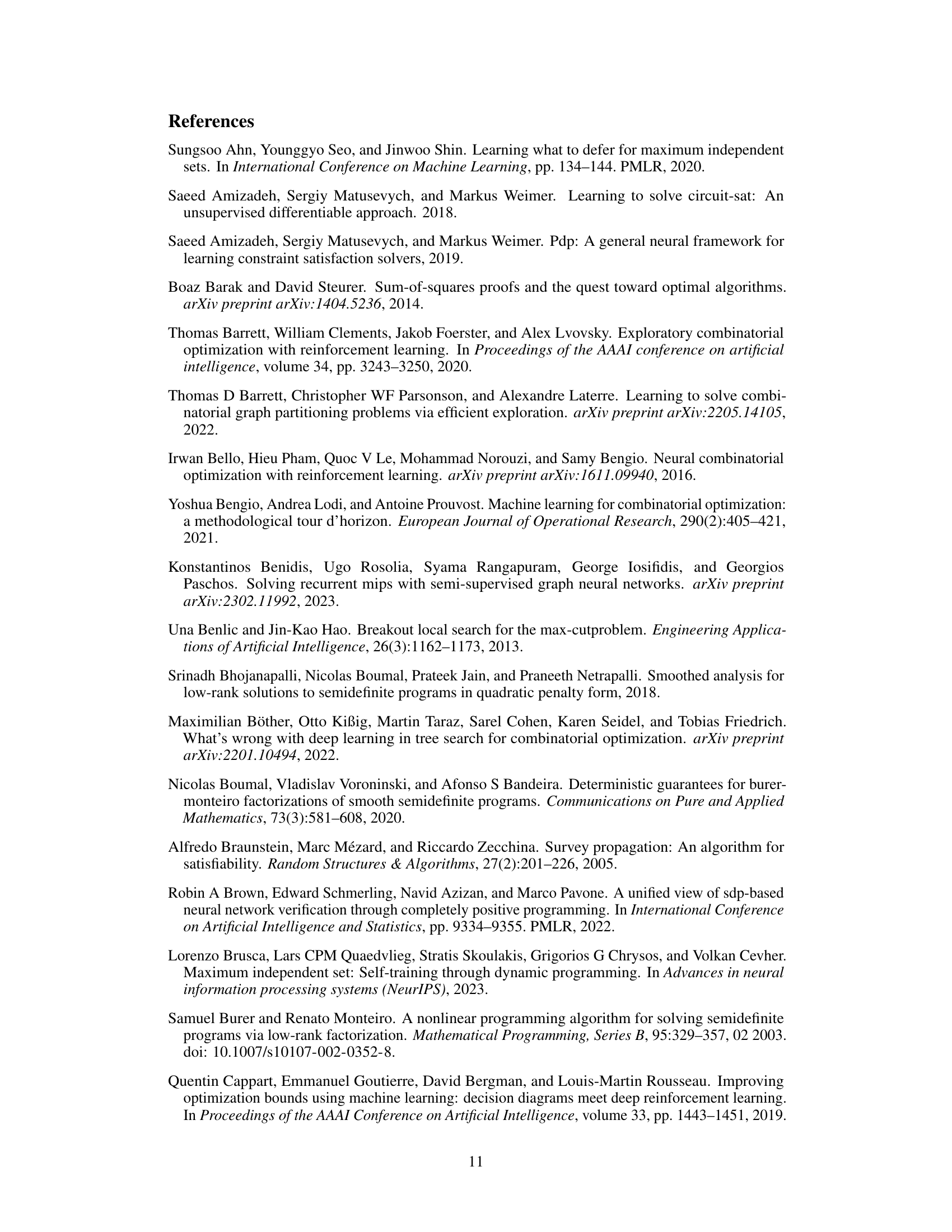

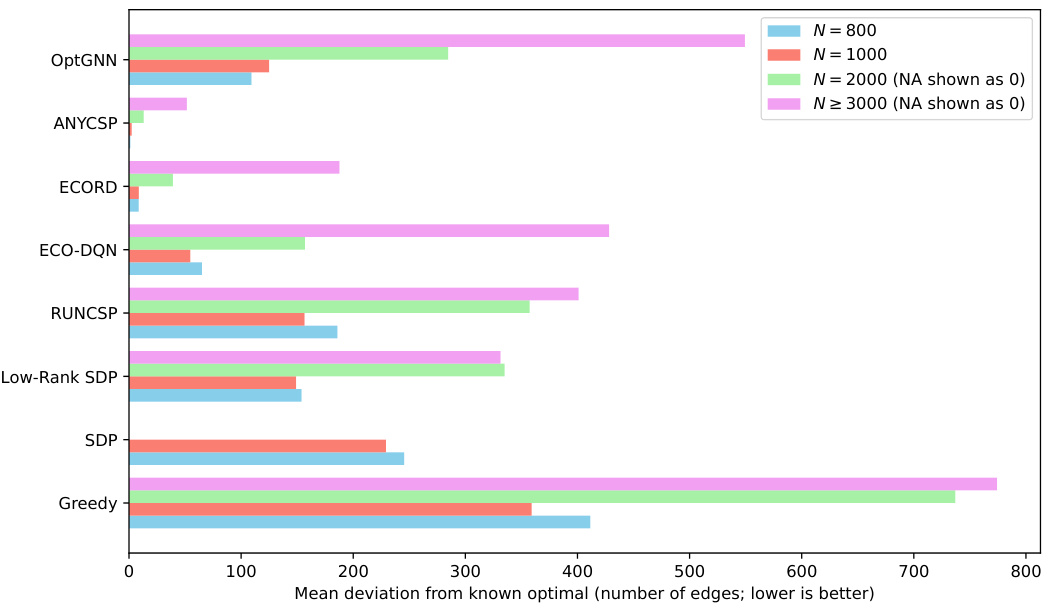

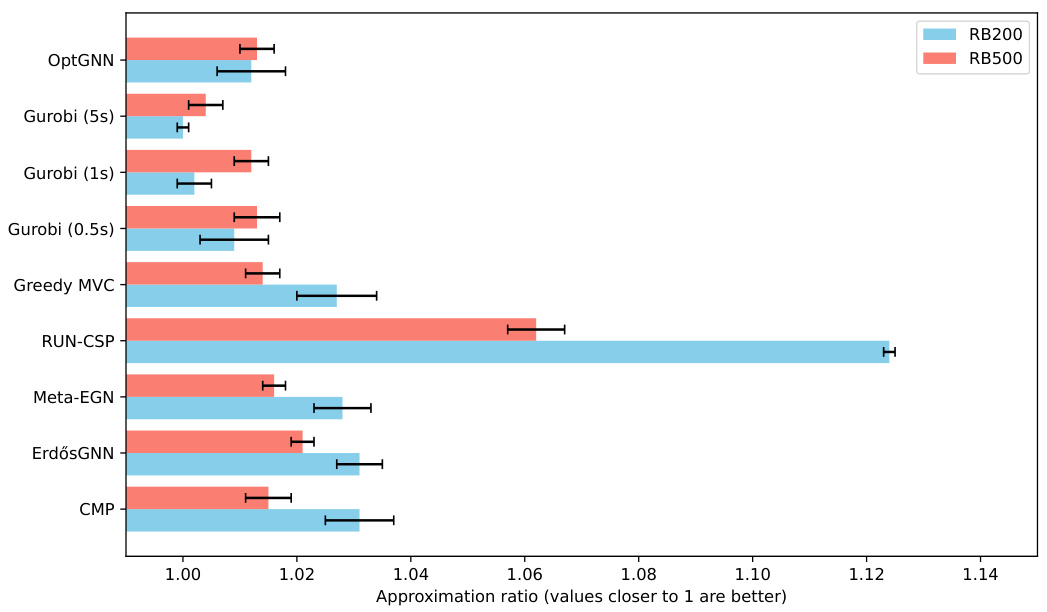

Figure 2(a) shows the comparison on GSET Max-Cut instances against state-of-the-art neural baselines. The numbers reported are the mean (over the graphs in the test set) deviations from the best-known Max-Cut values, reported in Benlic & Hao (2013). Figure 2(b) shows the average approximation ratio and standard deviation over the test set for vertex covers on forced RB instances. A ratio of 1.000 represents finding the minimum vertex cover.

This figure presents a comparison of the performance of OptGNN against other state-of-the-art methods for Max-Cut and Minimum Vertex Cover problems. Subfigure (a) shows results on Max-Cut problems using the GSET benchmark instances, comparing OptGNN against several neural network baselines as well as classical methods like Goemans-Williamson and a greedy heuristic. Subfigure (b) displays the approximation ratio achieved by OptGNN and other baselines on Minimum Vertex Cover problems, focusing on two specific distributions of forced RB instances (RB200 and RB500). The approximation ratio indicates how close the obtained solutions are to the optimal solutions, with values closer to 1 representing better performance.

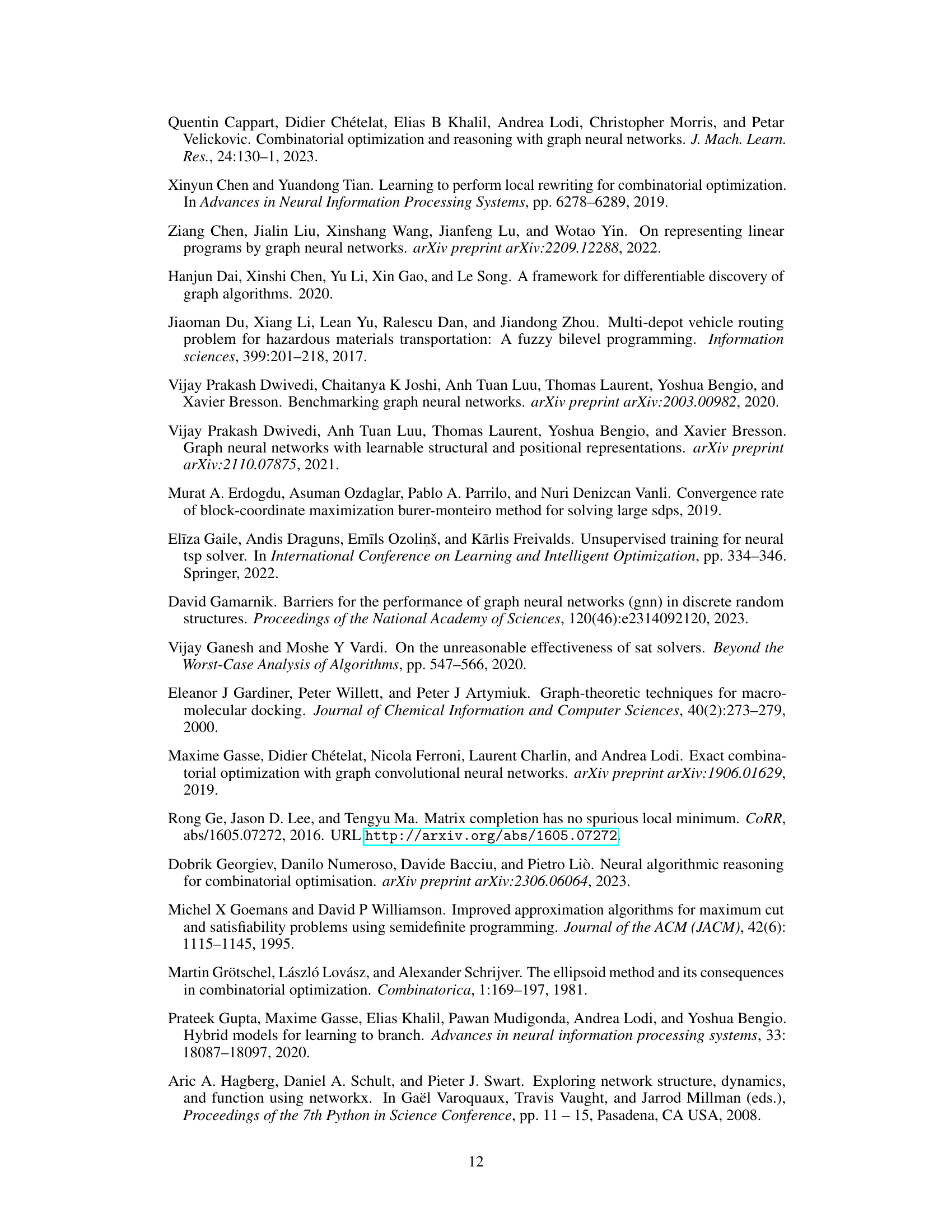

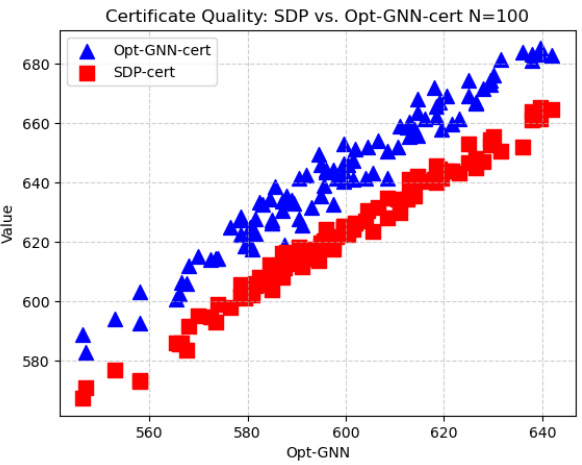

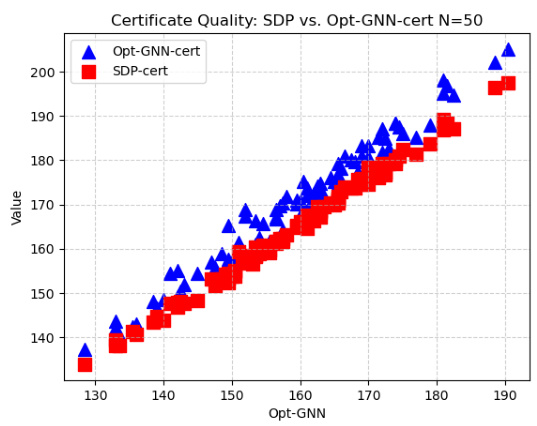

This figure compares the SDP certificates and OptGNN dual certificates on random graphs with 100 nodes for the Max-Cut problem. The plot shows that the OptGNN certificates closely track the SDP certificates, indicating good agreement in terms of solution quality. The key advantage of the OptGNN certificates is that they require significantly less computation time.

This figure compares the quality of SDP certificates versus OptGNN certificates for the Max-Cut problem on random graphs with 100 nodes. The x-axis represents the value obtained by the OptGNN method. The y-axis represents the value of the corresponding dual certificates. Both SDP and OptGNN dual certificates are plotted for comparison. The plot shows that OptGNN certificates closely track SDP certificates, indicating their high quality. The key takeaway is that OptGNN certificates achieve comparable accuracy to SDP certificates but with significantly faster computation times, which is a major advantage.

This figure shows the results of experiments comparing OptGNN’s performance against other methods for Max-Cut and Minimum Vertex Cover problems. Subfigure (a) displays the average approximation ratio for Max-Cut on GSET instances, comparing OptGNN against state-of-the-art neural baselines. Lower values indicate better performance. Subfigure (b) illustrates the average approximation ratio for Minimum Vertex Cover on forced RB instances, comparing OptGNN to classical and neural baselines. A ratio closer to 1 indicates better performance.

This figure contains two subfigures. Figure 2(a) shows the comparison of OptGNN against other state-of-the-art neural baselines and classical algorithms on Max-Cut instances from the GSET benchmark. Figure 2(b) shows the comparison of OptGNN against other neural and classical baselines on Minimum Vertex Cover instances from forced RB instances. Both subfigures show that OptGNN achieves competitive performance, often outperforming other approaches.

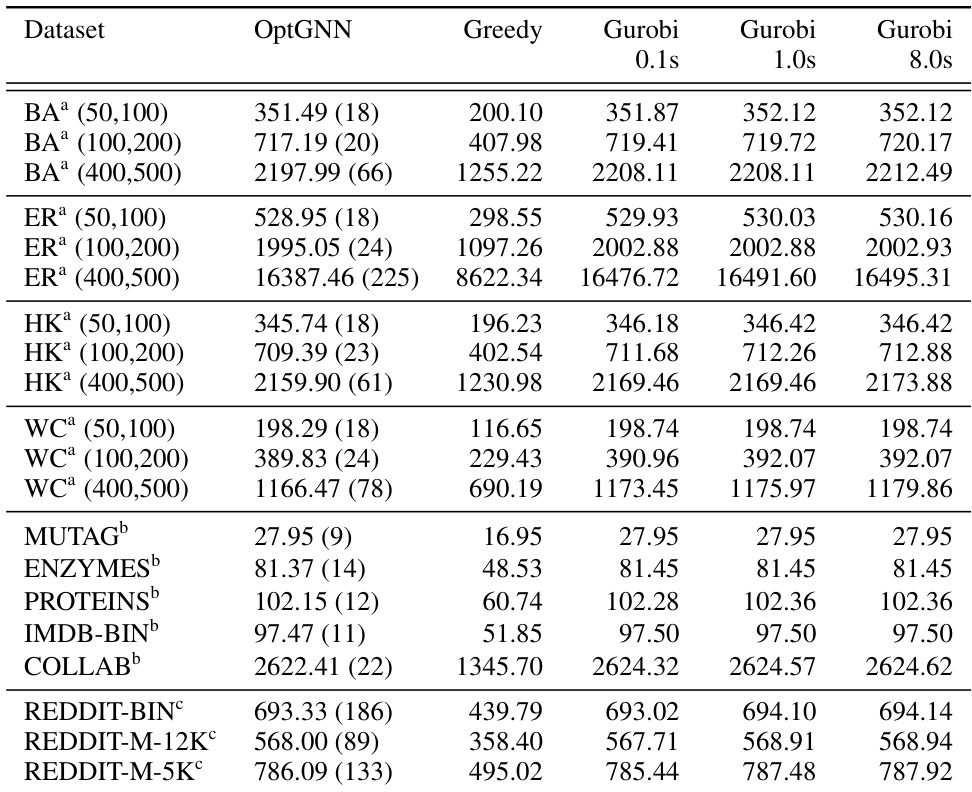

More on tables

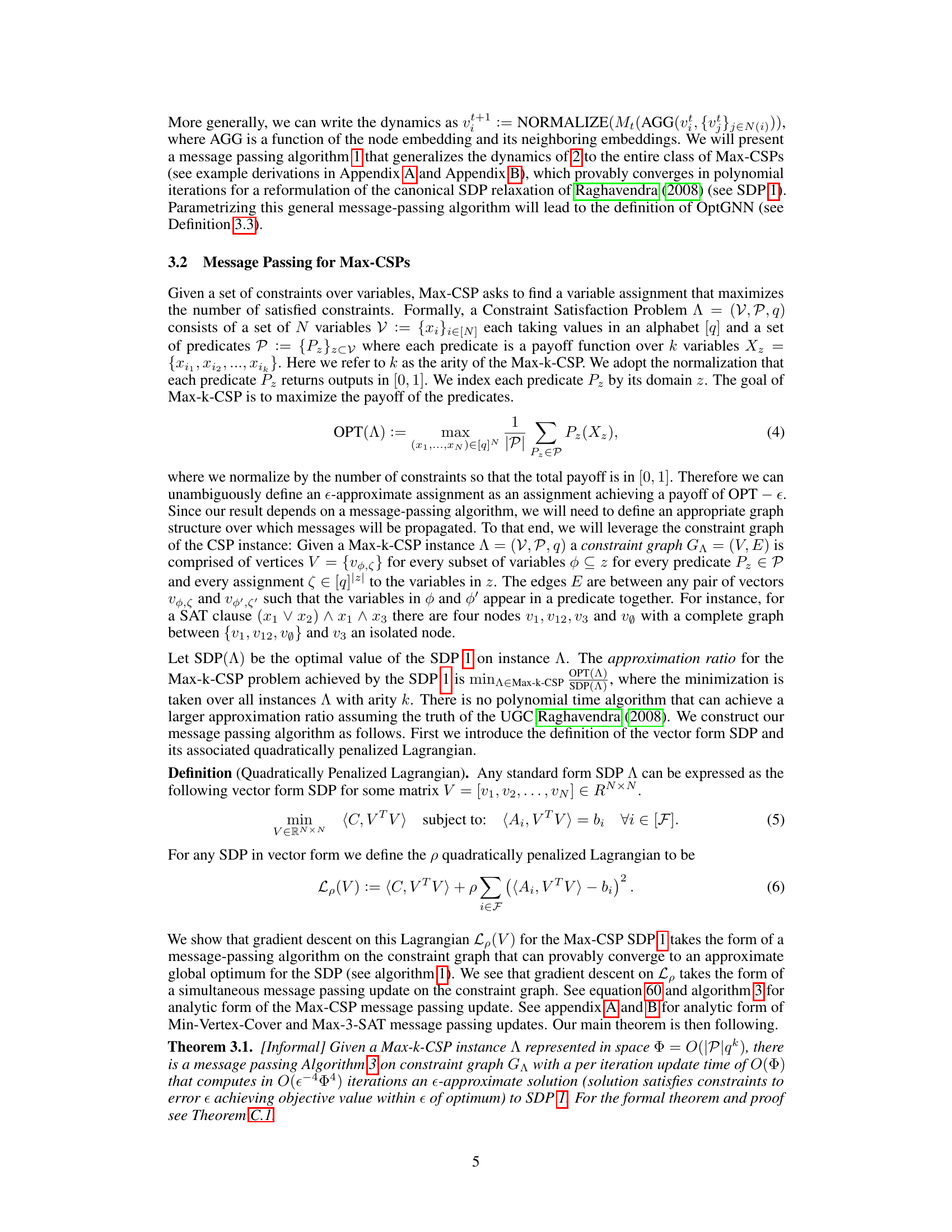

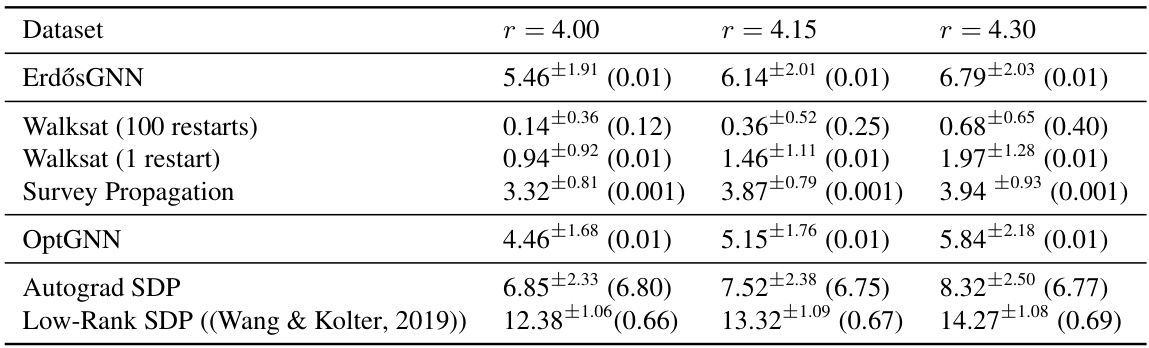

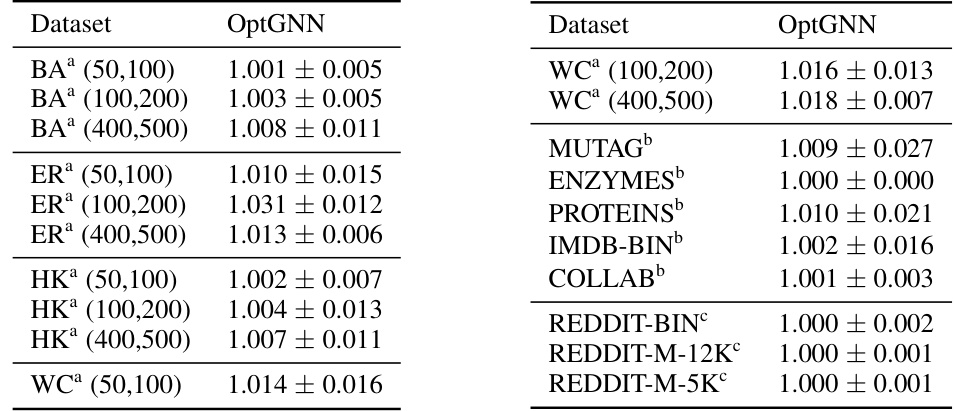

This table shows the average number of unsatisfied clauses for the Max-3-SAT problem, using different algorithms and different clause ratios. The standard deviation and average runtime for each method are also given. The results are presented for random instances with 100 variables and three different clause ratios. The algorithms compared include ErdosGNN, Walksat (with 1 and 100 restarts), Survey Propagation, OptGNN, Autograd SDP, and Low-Rank SDP. OptGNN outperforms most of the other methods, especially when compared to the Autograd SDP and Low-Rank SDP methods.

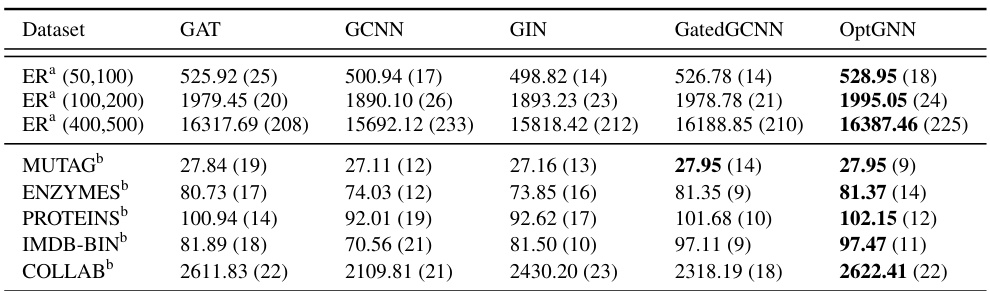

This table compares the performance of several Graph Neural Network (GNN) architectures against OptGNN, on Maximum Cut problem. It shows that OptGNN outperforms other GNN architectures for this problem, although some other models achieve similar performance in several cases.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of three algorithms (OptGNN, Greedy, and Gurobi) on the Maximum Cut problem across various datasets. OptGNN’s runtime is also provided in milliseconds. Higher scores indicate better performance. The table allows for a comparison of OptGNN’s speed and accuracy relative to the established Greedy and Gurobi methods.

This table presents the performance comparison of three different algorithms (OptGNN, Greedy, and Gurobi) on Maximum Cut problem using several datasets. The average cut size is reported for each algorithm and dataset on the test set. OptGNN’s average runtime in milliseconds is also provided in parentheses. A higher cut size indicates better performance.

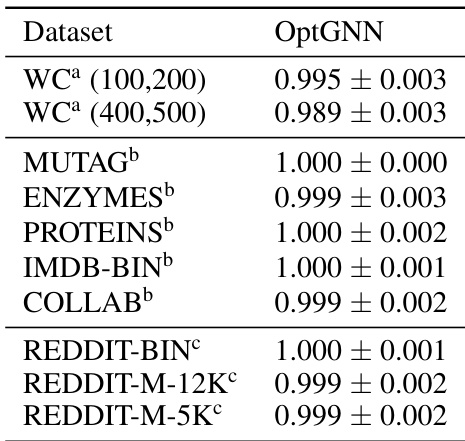

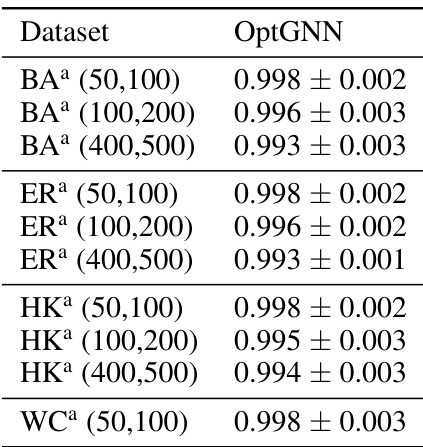

This table presents the performance of the OptGNN model on the Max-Cut problem, comparing its results to those obtained using the Gurobi solver with an 8-second time limit. The performance is expressed as a ratio, showing how close OptGNN gets to the optimal solution found by Gurobi. The average ratio and standard deviation are reported for each dataset, indicating both the typical performance and the variability of the results. The caption highlights that OptGNN achieves results very close to Gurobi’s, with a maximum difference of only 1.1%.

This table shows the performance of OptGNN on Max-Cut compared to Gurobi (with an 8-second time limit). The performance is expressed as a ratio of OptGNN’s result to Gurobi’s result for each graph in the test set. The average and standard deviation of these ratios are given. OptGNN performs very well, on average achieving 98.9% of Gurobi’s performance.

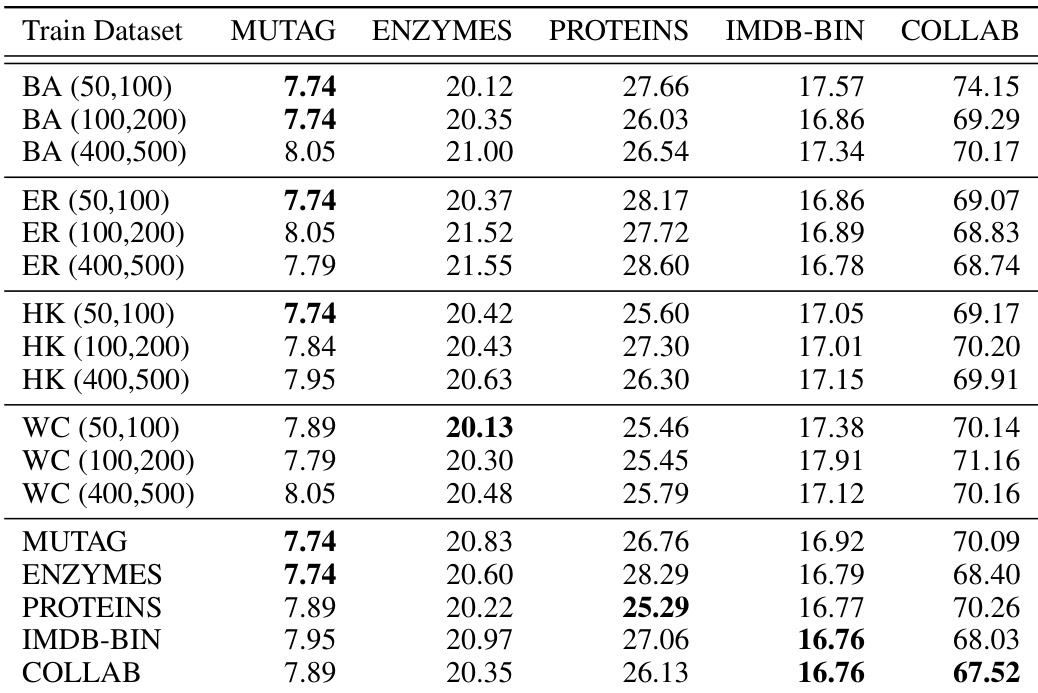

This table shows the generalization performance of OptGNN trained on different datasets when tested on other TU datasets. Each row represents a model trained on a specific dataset (shown in the first column), and the columns show its performance on different test datasets. The results show that the model generalizes well to datasets it has not been trained on, suggesting that OptGNN captures generalizable aspects of the problem rather than merely overfitting the training data.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of OptGNN, a greedy algorithm, and Gurobi on various Max-Cut datasets. The average cut size achieved by each method on the test set is reported, with higher scores indicating better performance. For OptGNN, average runtime in milliseconds is also provided in parentheses. The table allows for an evaluation of OptGNN against classical and more sophisticated solvers.

This table compares the performance of OptGNN against other state-of-the-art Graph Neural Network architectures on the Max-Cut problem. It shows the average cut size achieved by each model on several datasets, demonstrating that OptGNN generally achieves competitive or better results.

This table shows the generalization performance of OptGNN models trained on different datasets when tested on a subset of the TU datasets. The results indicate that the model generalizes well to different datasets, suggesting that it captures a general process instead of overfitting to the training data.

Full paper#