↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Causal discovery from observational count data is crucial across many fields but challenging due to inherent complexities, especially branching structures often ignored by existing methods like Bayesian Networks. Previous attempts, such as cumulant-based methods, struggled to fully identify causal directions in these complex scenarios, leading to a gap in identifiability.

This research tackles the identifiability gap by leveraging Probability Generating Functions (PGFs). The authors derive a closed-form solution for PGFs in Poisson Branching Structural Causal Models (PB-SCMs), demonstrating that each component uniquely encodes a local structure. A practical algorithm is proposed for learning causal skeletons and directions, showcasing effectiveness through experiments on synthetic and real datasets. This PGF-based approach offers a more accurate, efficient, and comprehensive solution to causal discovery in PB-SCMs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with count data and causal inference. It addresses limitations of existing methods by proposing a novel approach based on Probability Generating Functions (PGFs), offering a more accurate and efficient way to discover causal structures in complex systems. This work opens new avenues for research into causal discovery in areas like biology, economics, and network analysis where count data is prevalent.

Visual Insights#

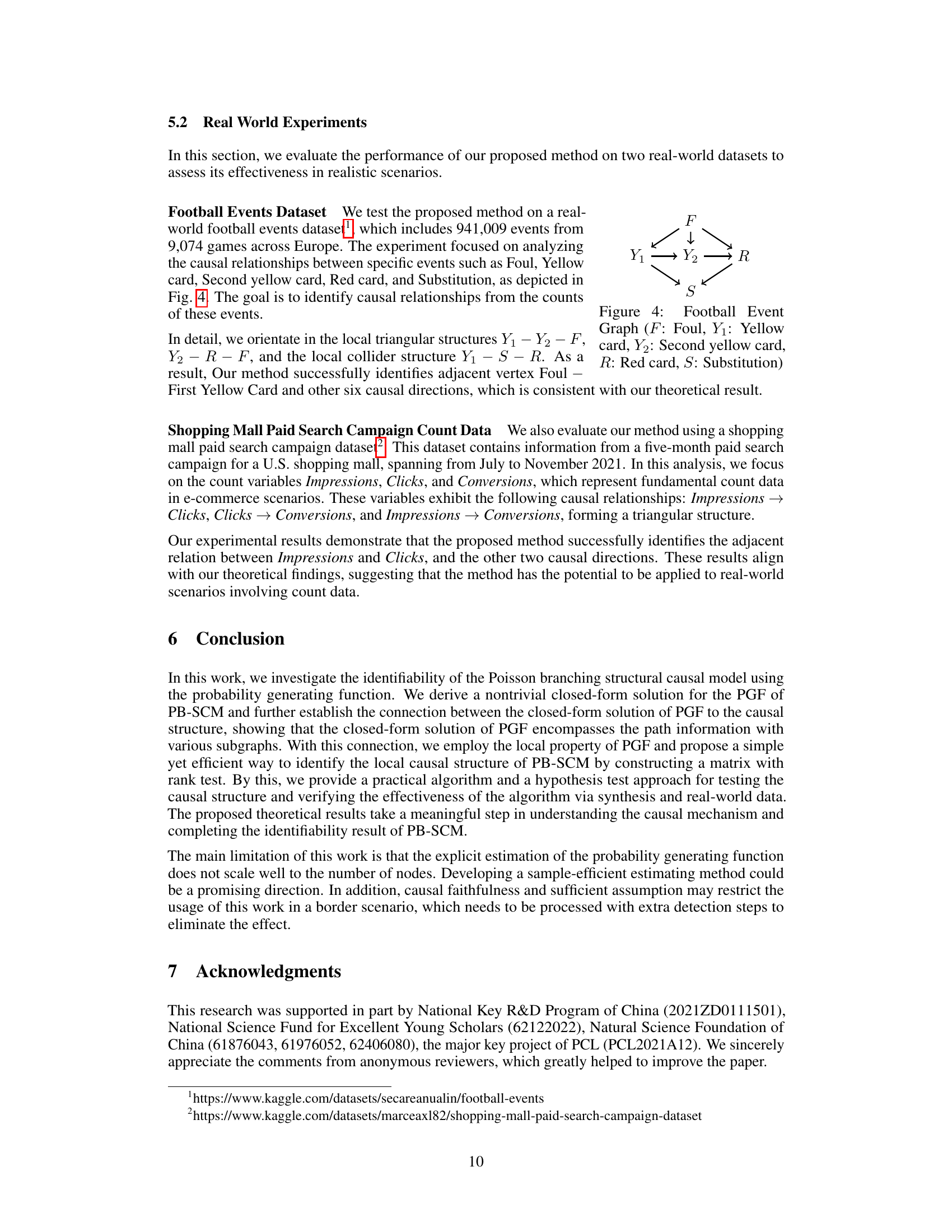

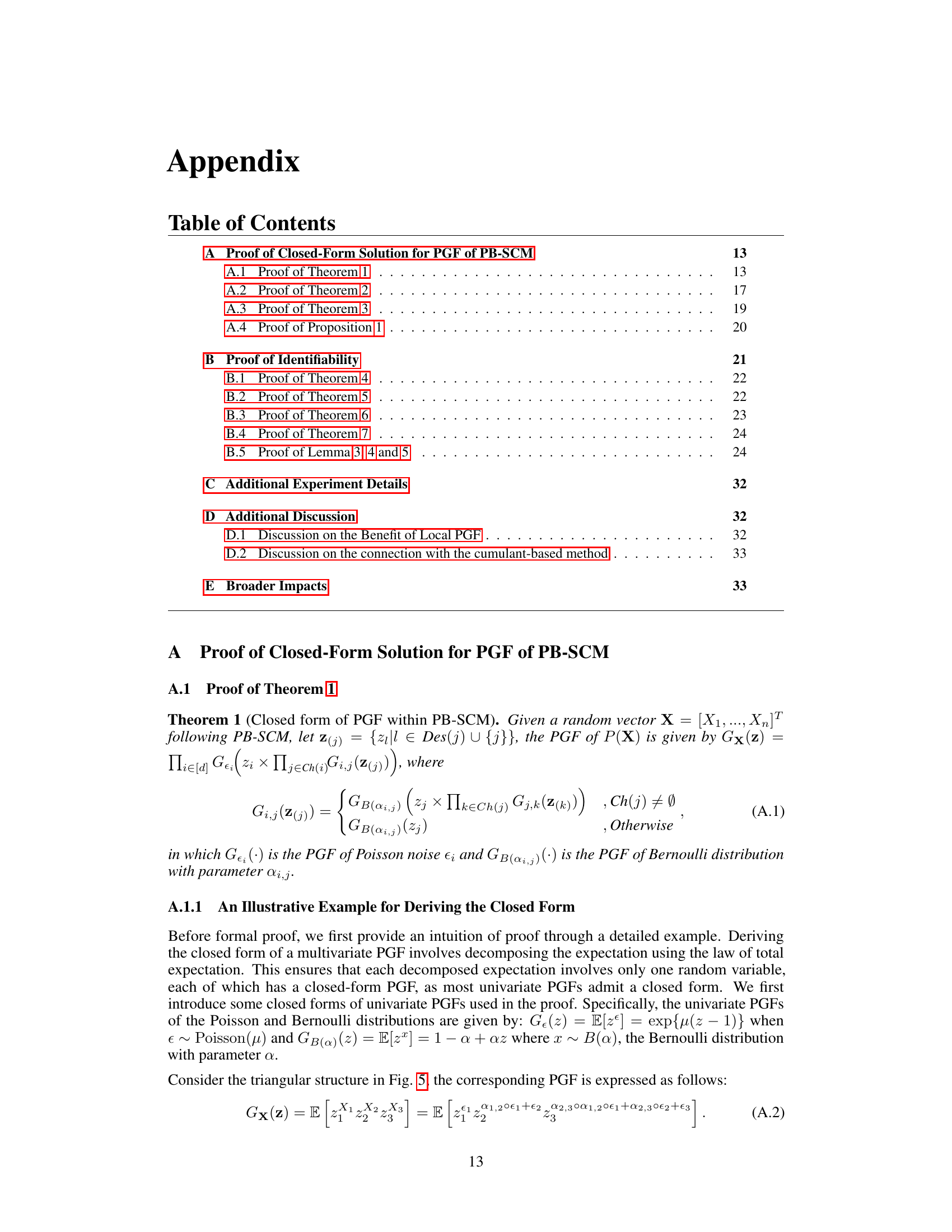

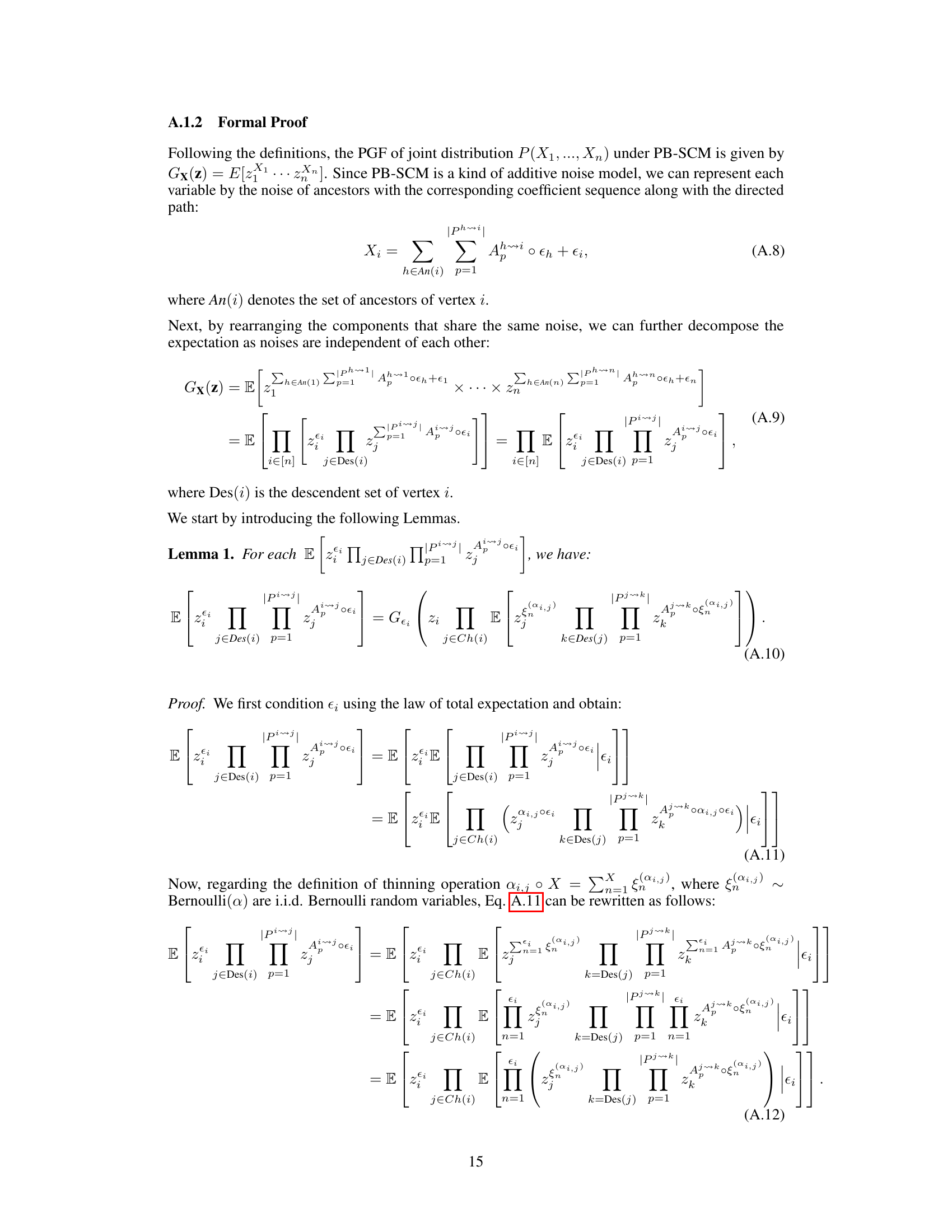

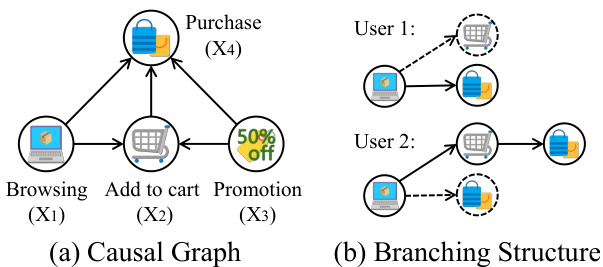

This figure illustrates an example of how count data can be represented using a causal graph and a branching structure. The causal graph (a) shows the relationships between different events in an online shopping scenario: browsing (X1), adding to cart (X2), promotion (X3), and purchasing (X4). The branching structure (b) highlights the inherent branching nature of these events. For example, a browsing event (X1) might lead directly to a purchase or indirectly through an ‘add to cart’ event (X2). The figure demonstrates that a single browsing event can trigger multiple subsequent events, which are then summarized as counts. This branching nature is important to consider when modeling and analyzing count data.

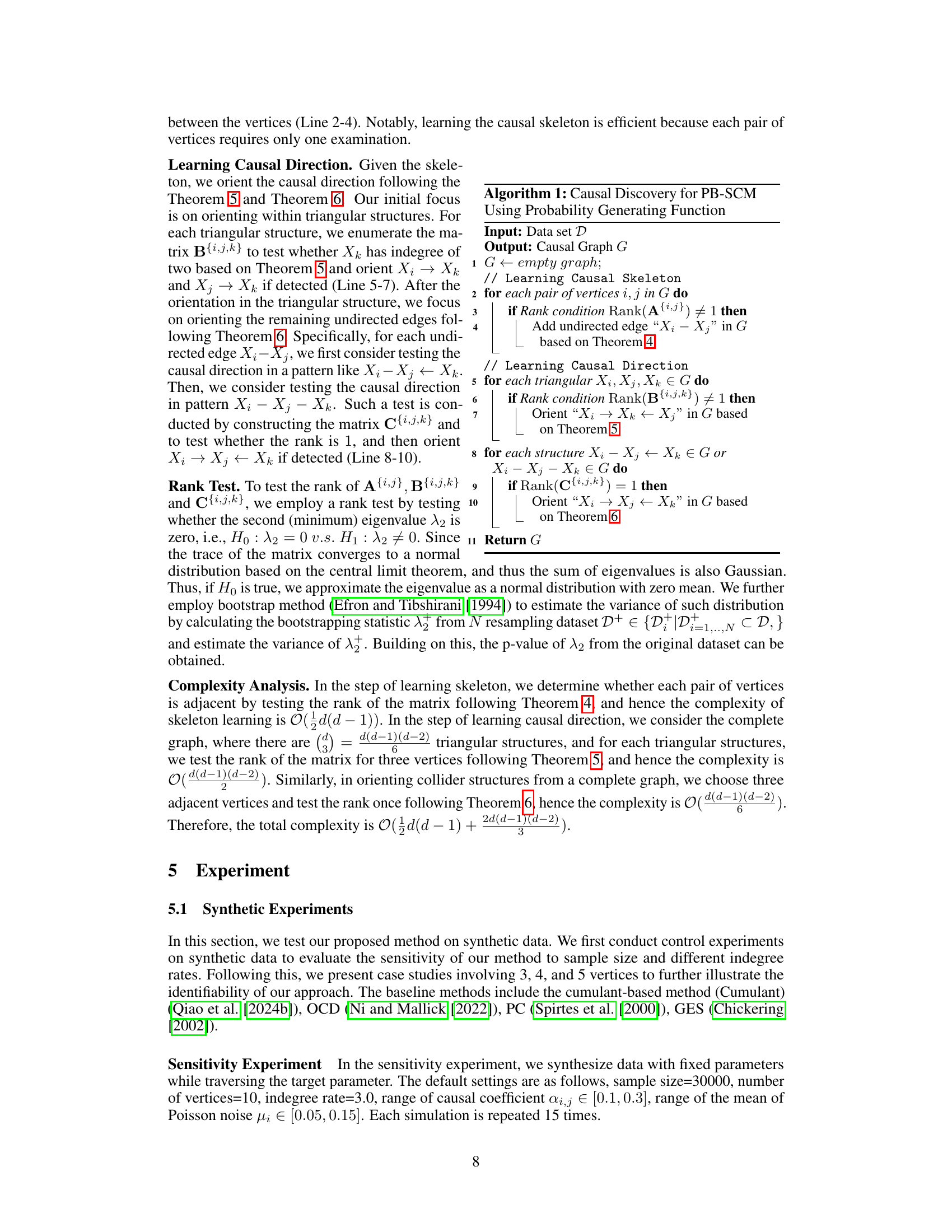

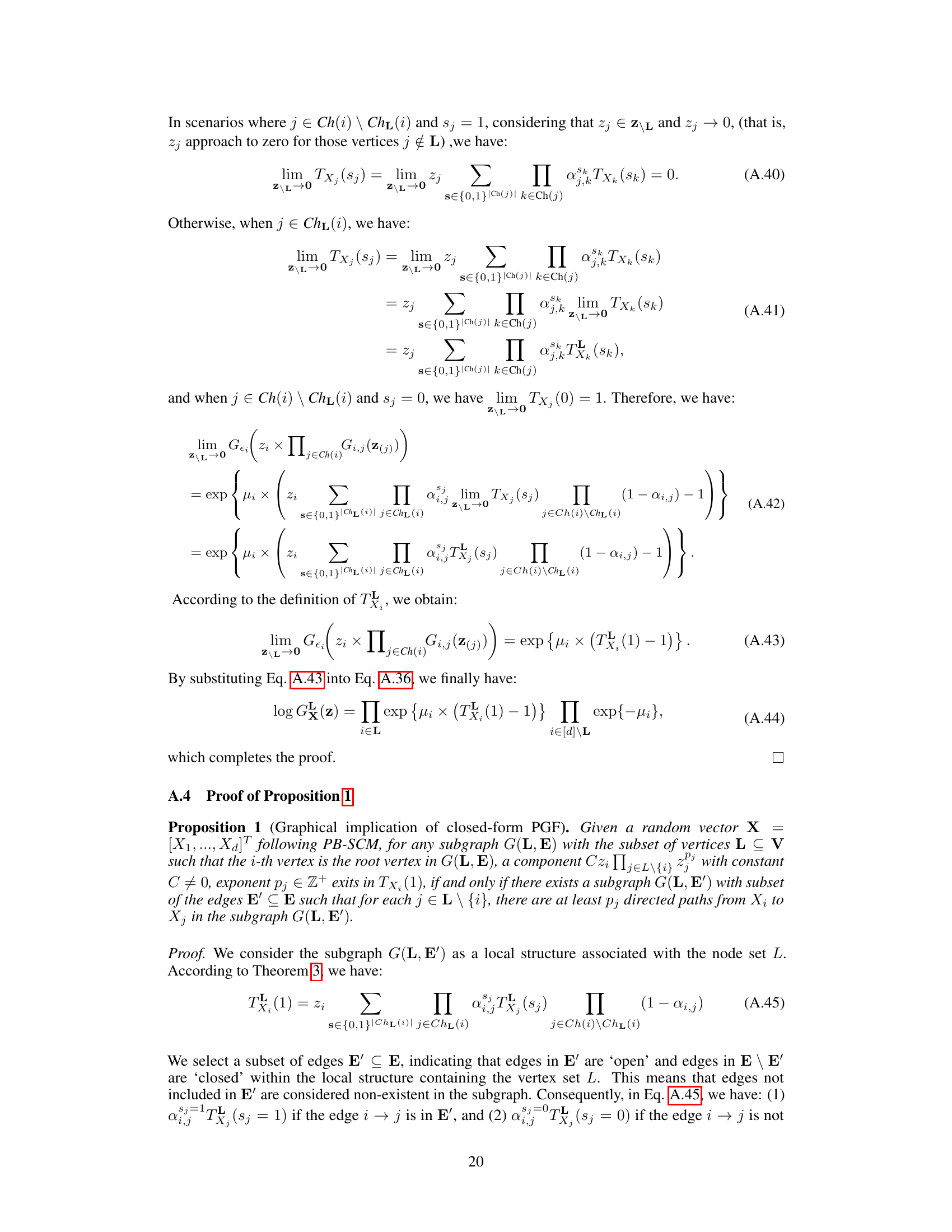

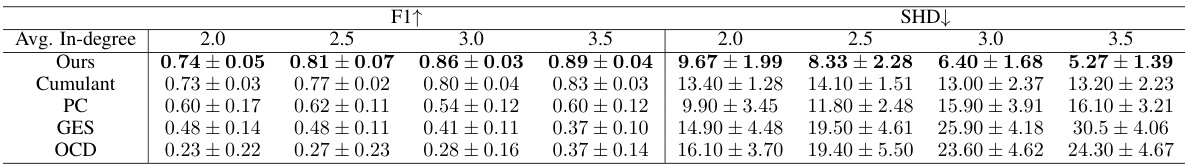

This table presents the performance of different causal discovery methods under varying average in-degree rates. The average in-degree controls the sparsity of the causal structure; higher rates lead to denser structures. The table shows F1-score and Structural Hamming Distance (SHD) for each method, across different in-degree rates (2.0, 2.5, 3.0, 3.5). Lower SHD and higher F1-score indicate better performance.

In-depth insights#

PB-SCM Identifiability#

The identifiability of Poisson Branching Structural Causal Models (PB-SCMs) is a crucial aspect of causal discovery from count data. Existing methods, while providing some identifiability results, often fall short, failing to identify certain causal directions. This paper delves into this challenge by proposing a novel approach leveraging the probability generating function (PGF). The core idea is that the PGF of a PB-SCM uniquely encodes the causal structure. By developing a closed-form solution for the PGF, the authors demonstrate how specific components of this solution directly correspond to local causal structures within the model. This unique encoding allows for the identification of not only the causal skeleton but also the directionality of causal relationships, addressing the limitations of previous methods. The method’s effectiveness is demonstrated through experiments on both synthetic and real datasets, showcasing its ability to handle scenarios where existing techniques fail. The use of PGF provides a compact and mathematically rigorous framework for tackling this complex problem, offering a significant advancement in causal inference for count data.

PGF for Causal Discovery#

The application of Probability Generating Functions (PGFs) to causal discovery presents a novel approach with intriguing potential. PGFs offer a unique way to characterize the probability distributions of discrete random variables, which are frequently encountered in various fields like biology, economics, and network analysis. By leveraging the closed-form solution of the PGF for a specific causal model, such as the Poisson Branching Structural Causal Model (PB-SCM), we can gain detailed insights into the underlying causal relationships. The compact representation of the PGF allows for efficient analysis of local structures within the graph, potentially mitigating computational limitations associated with analyzing the full global structure directly. Moreover, identifiability results derived from the PGF can fill gaps in existing methods, enabling the identification of causal structures that previously remained elusive. This ability to exploit the PGF’s closed form and analyze local structures within the graph represents a significant advantage, potentially leading to more robust and efficient algorithms for causal discovery in scenarios involving complex systems and large datasets. However, it is important to note the reliance of PGF-based methods on the precise specification of the causal model and the availability of an efficient closed-form solution of the PGF. Further research could explore generalizability and the adaptation of these techniques to more complex causal models.

Local PGF Analysis#

Local PGF analysis offers a powerful technique for dissecting complex causal structures in Poisson Branching Structural Causal Models (PB-SCMs). By strategically setting some variables’ values to zero, it isolates and analyzes specific subgraphs, significantly reducing computational complexity compared to analyzing the entire global PGF. This localized approach allows for efficient identification of adjacency relations, enabling the construction of causal skeletons. Further, local PGF analysis provides identifiability results for key local structures, such as triangular and collider configurations, that are crucial for orienting edges in the causal graph and determining causal direction. The method’s effectiveness stems from its ability to analyze local asymmetries without needing high-order derivatives or complex calculations. This focus on localized analyses makes it both more computationally feasible and interpretable, leading to a more practical and efficient causal discovery algorithm for PB-SCMs.

Algorithm & Experiments#

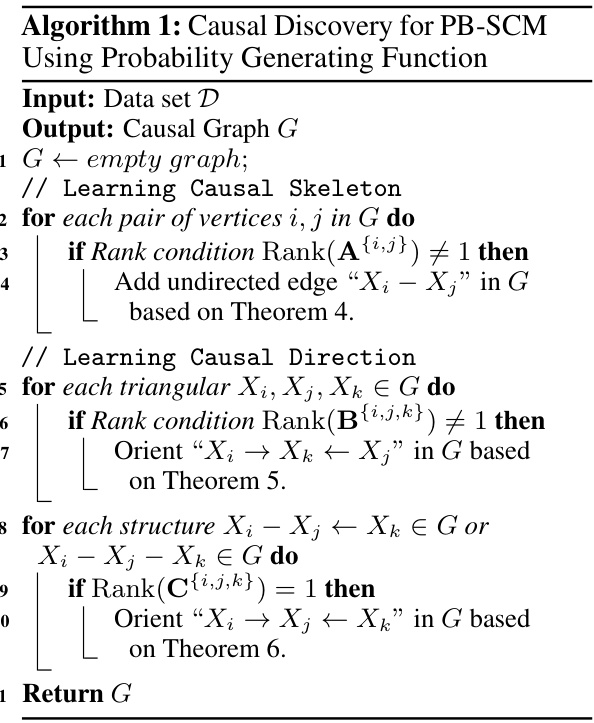

An effective algorithm and convincing experiments are crucial for validating a research paper’s claims. The “Algorithm & Experiments” section should meticulously detail the proposed algorithm’s steps, including data structures, computational complexity analysis, and any algorithmic optimizations employed. Pseudocode or a flowchart can significantly improve clarity. The experimental setup must be rigorously described, specifying datasets (including their source and characteristics), evaluation metrics, and baselines for comparison. Results should be presented clearly, using tables, figures, and statistical significance tests to support claims of improvements over existing approaches. A thorough discussion of both positive and negative results is vital, acknowledging limitations and potential sources of error. Robustness testing across different parameters or datasets strengthens the findings. Reproducibility is paramount; the section should provide sufficient detail to allow others to replicate the experiments independently. The experiments should be designed to directly address the key research questions and demonstrate the algorithm’s practical effectiveness.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on Poisson Branching Structural Causal Models (PB-SCMs) could explore several promising avenues. Extending the method to handle more complex data types, such as mixed count and continuous data, would enhance its applicability in real-world scenarios. Investigating the impact of violations of the faithfulness assumption on the algorithm’s performance and identifying strategies to mitigate these effects is crucial. Developing more efficient algorithms to reduce computational complexity for large-scale datasets would improve scalability. Further research could focus on handling latent confounders, enabling the identification of causal structures in more complex settings. Finally, developing methods for causal inference in dynamic systems with evolving branching structures is a worthwhile challenge for future research. This would enable analyzing PB-SCMs where causal relationships change over time, making the model even more versatile.

More visual insights#

More on figures

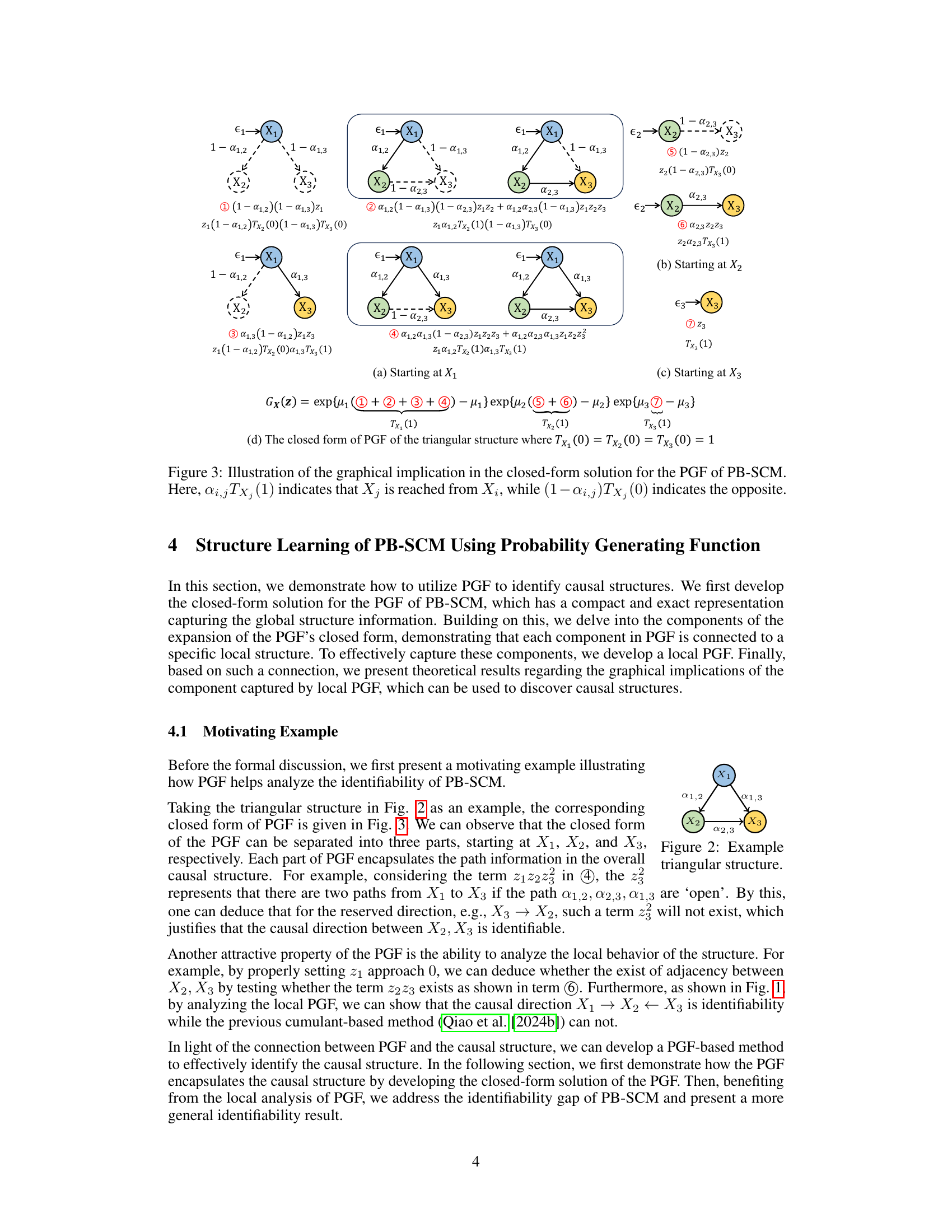

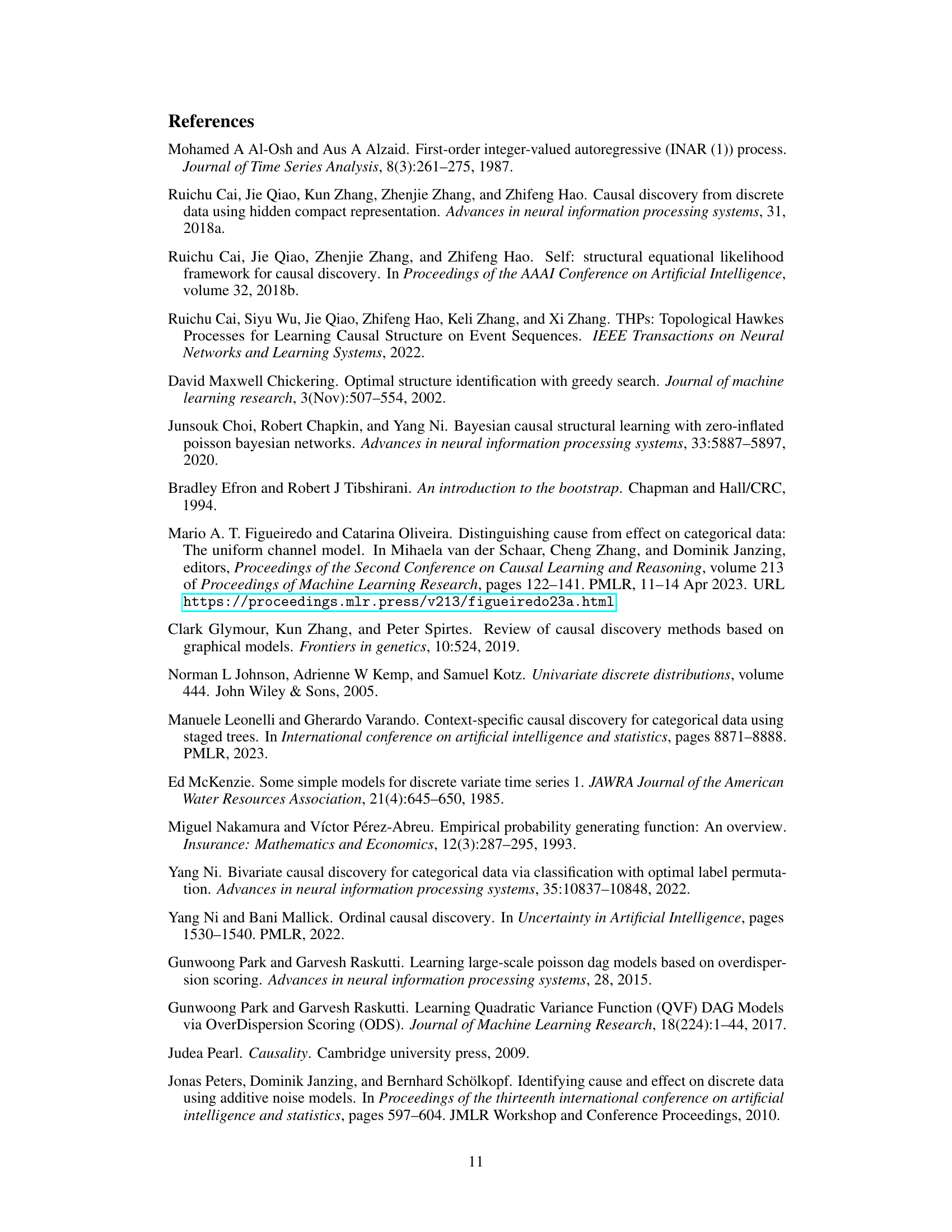

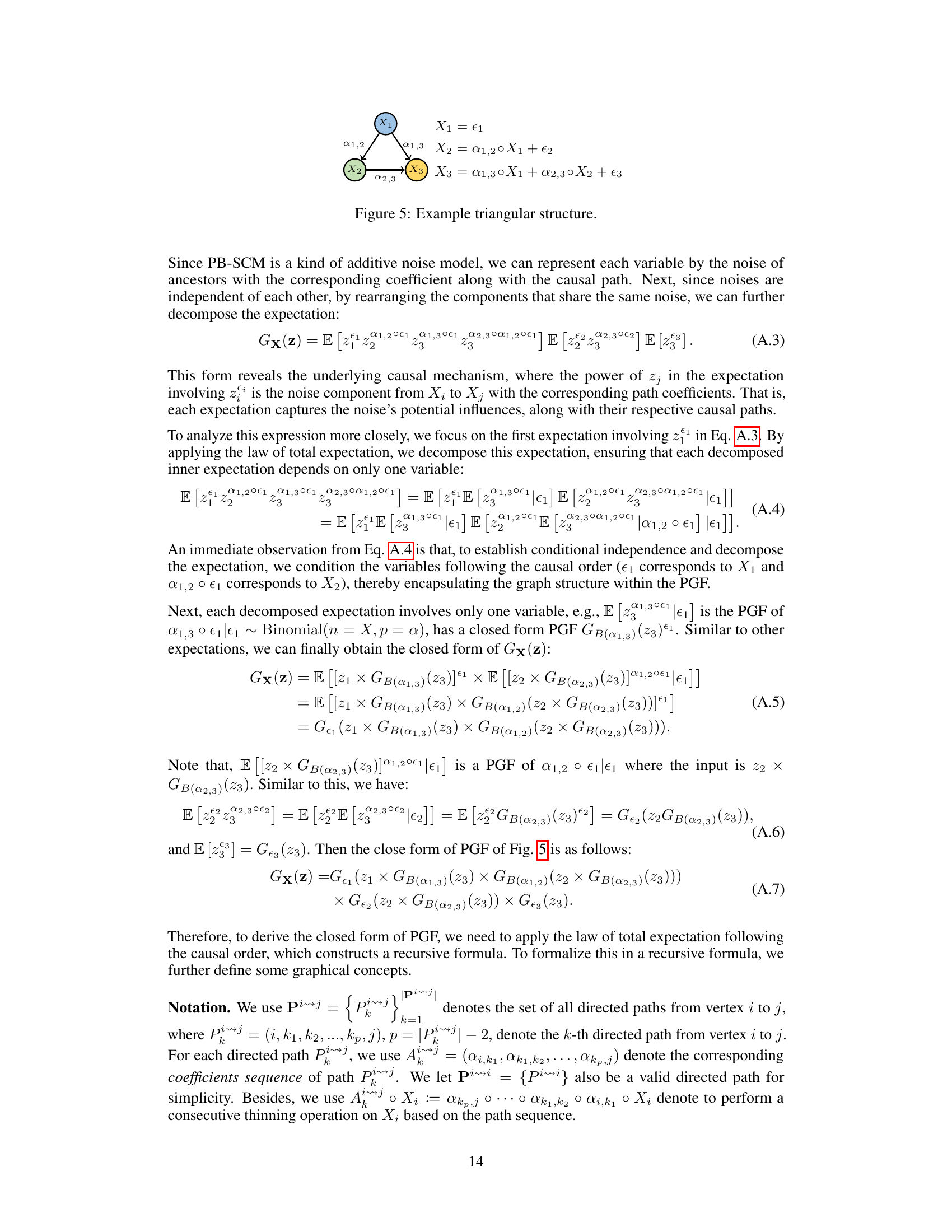

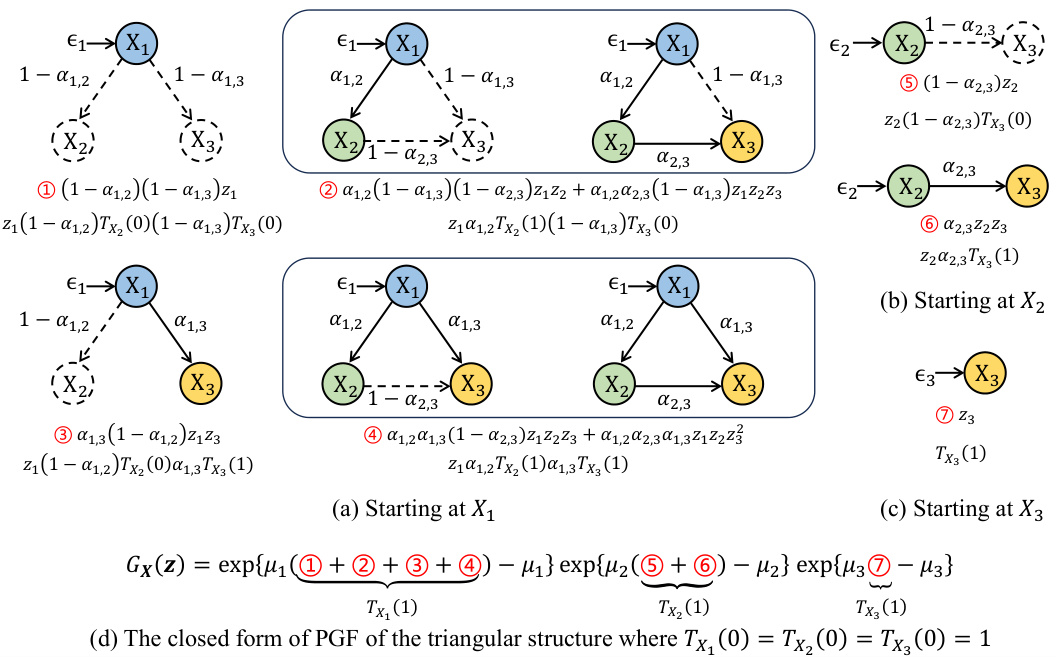

This figure illustrates how the closed-form solution of the probability generating function (PGF) for the Poisson Branching Structural Causal Model (PB-SCM) reflects the underlying causal structure. Each term in the closed-form solution uniquely encodes a specific local structure within the PB-SCM. The figure shows four different starting points (X1, X2, X3) in the triangular graph to illustrate how each path is encoded within each component. For example, α₁,₂(1-α₁,₃)(1-α₂,₃)z₁z₂ represents a path from X₁ to X₂ and X₃, without involving X₃ directly. The final closed-form solution (d) is a combination of these components, showcasing that the entire PGF compactly represents the causal graph.

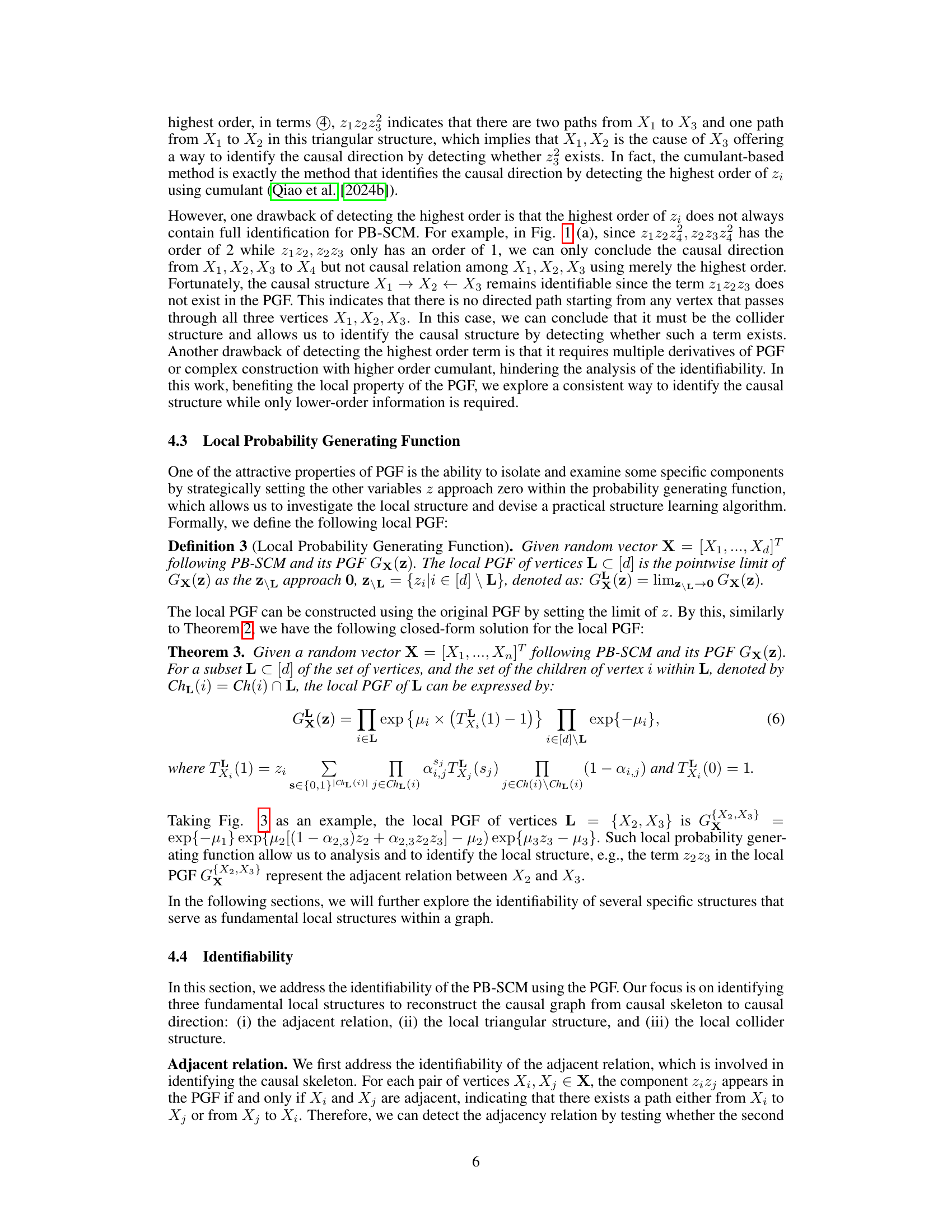

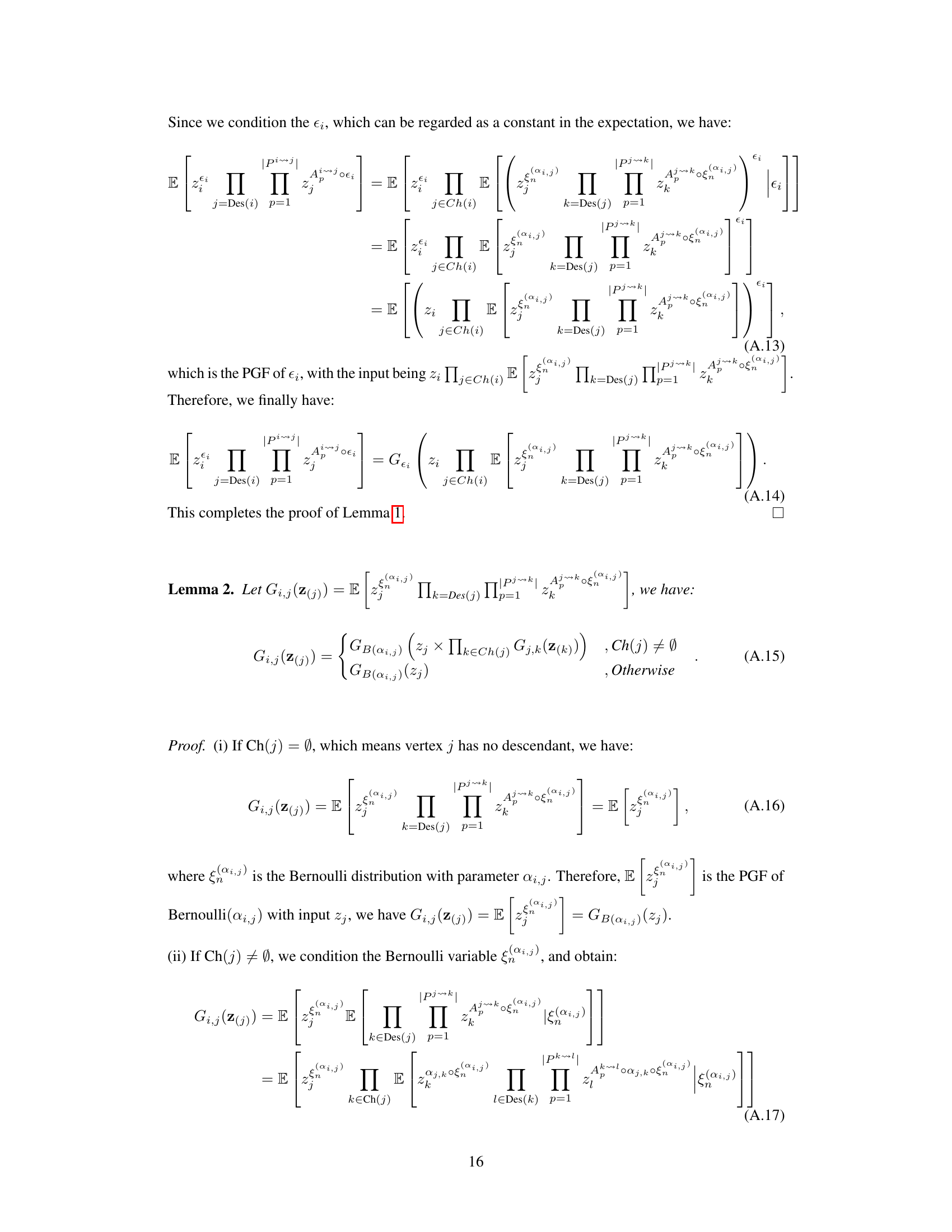

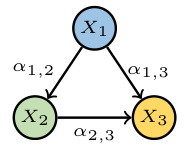

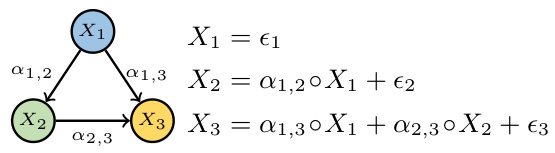

This figure shows a simple causal graph with three nodes (X1, X2, X3) and directed edges representing causal relationships. The arrows indicate the direction of causality: X1 influences both X2 and X3, and X2 influences X3. Each edge is labeled with a parameter (αi,j) representing the probability that a value of Xi is passed to Xj, and it implies a causal effect of Xi on Xj. This structure is a fundamental building block in the Poisson Branching Structural Causal Model discussed in the paper.

This figure shows a simple causal graph with three nodes (X1, X2, X3) and their corresponding equations in a Poisson Branching Structural Causal Model (PB-SCM). X1 is a source node with only a noise term (€1). X2 is a child of X1, receiving a thinned contribution (α1,2 ○ X1) from X1 plus its own noise (€2). X3 is a child of both X1 and X2, receiving thinned contributions (α1,3 ○ X1 and α2,3 ○ X2) from its parents plus its own noise (€3). The α terms represent the binomial thinning parameters, showing the probabilistic nature of the influence from parent to child. This simple model is used to illustrate how the Probability Generating Function (PGF) can be used to derive identifiability results for the PB-SCM.

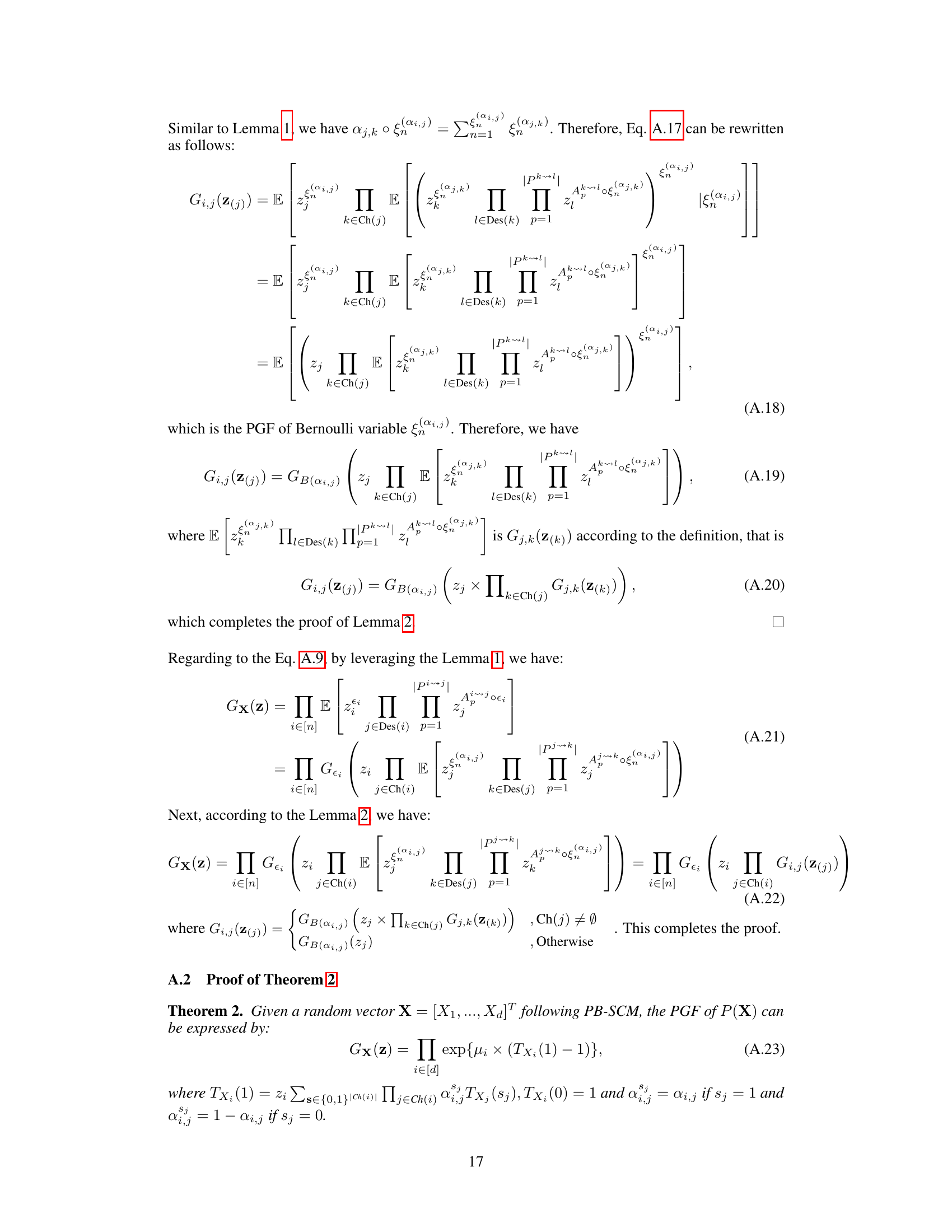

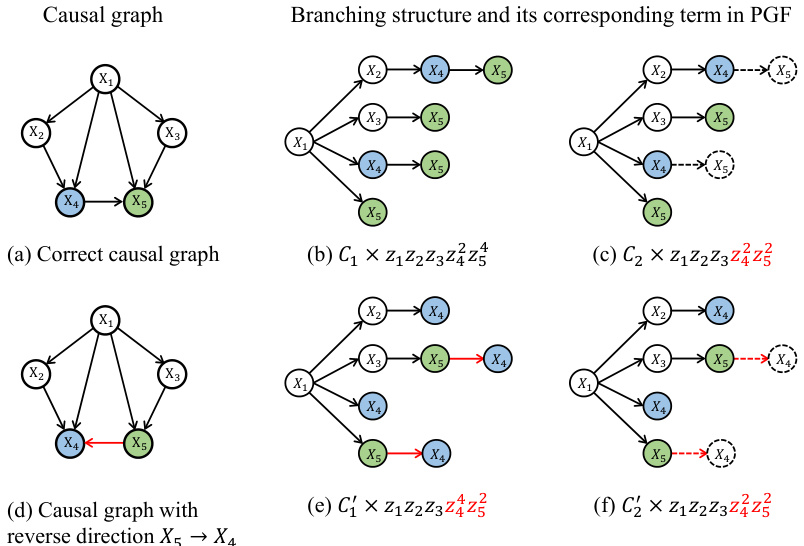

This figure illustrates how different branching structures in a causal graph affect the terms appearing in the Probability Generating Function (PGF). It shows two scenarios: one where X4 causes X5, and another where X5 causes X4. For each scenario, it presents the correct causal graph and two variations of branching structures, one that includes all possible paths and one that excludes a specific path (either X4 to X5 or X5 to X4). The corresponding PGF terms are shown for each structure, highlighting how the presence or absence of certain paths leads to different terms in the PGF, impacting the identifiability of the causal direction.

More on tables

This table presents the performance of different causal discovery methods under varying average in-degree rates. The average in-degree controls the sparsity of the causal graph; higher rates lead to denser graphs. The table shows F1 scores (higher is better), indicating the accuracy of causal structure learning, and Structural Hamming Distance (SHD) scores (lower is better), measuring the difference between the learned and true causal structures. The results demonstrate how different methods perform across various levels of graph density.

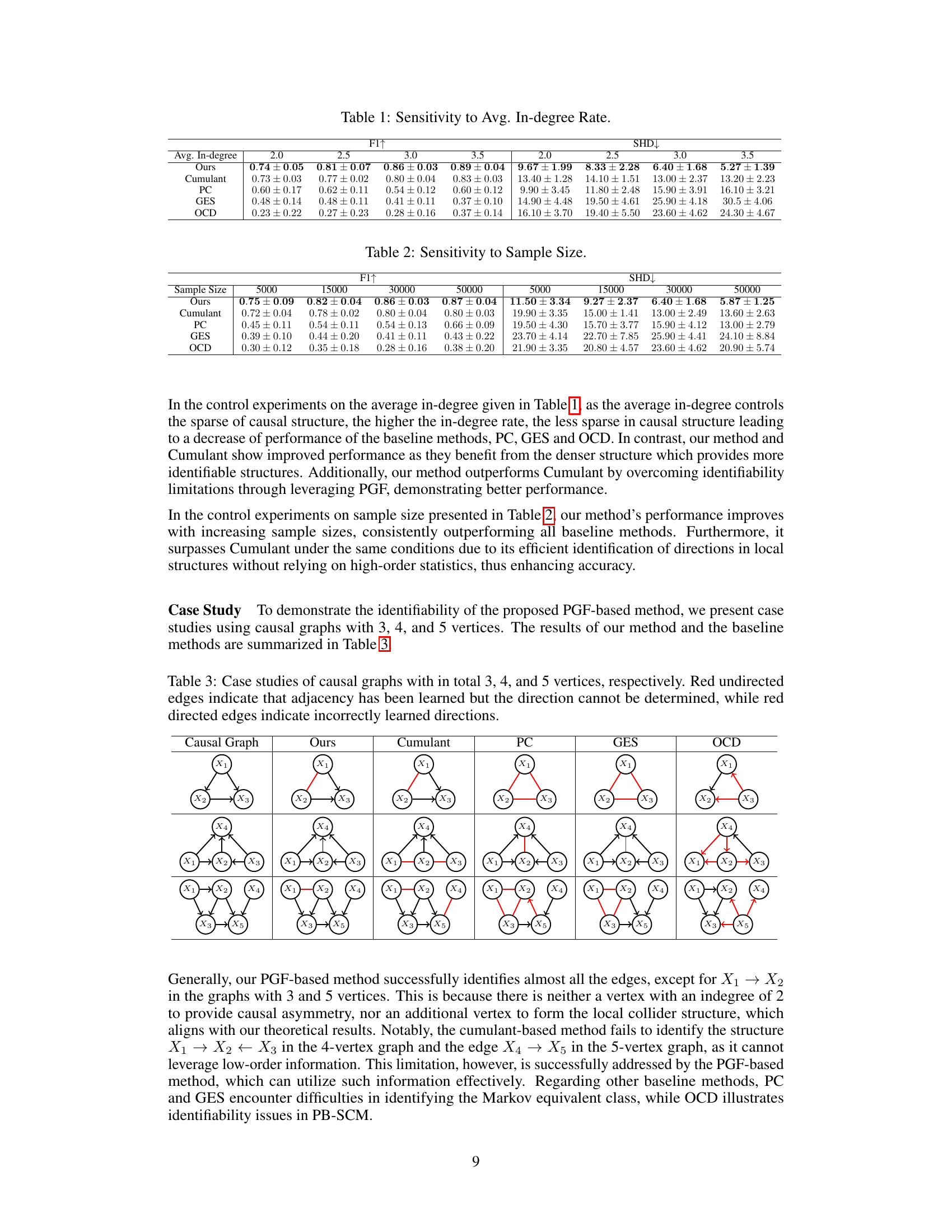

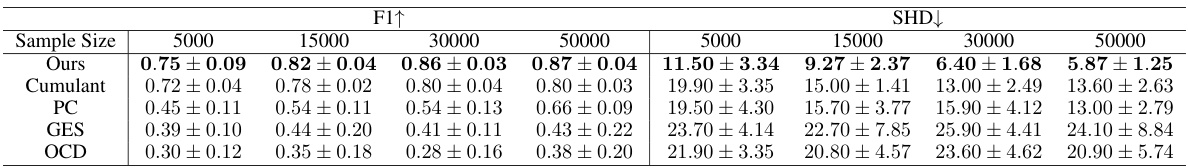

This table shows the impact of varying sample sizes (5000, 15000, 30000, 50000) on the performance of the proposed PGF-based method and several baseline methods for causal structure learning. The metrics used to evaluate performance are F1-score (higher is better) and Structural Hamming Distance (SHD) (lower is better). The results demonstrate the improved performance of the PGF-based method and its increased accuracy with larger sample sizes.

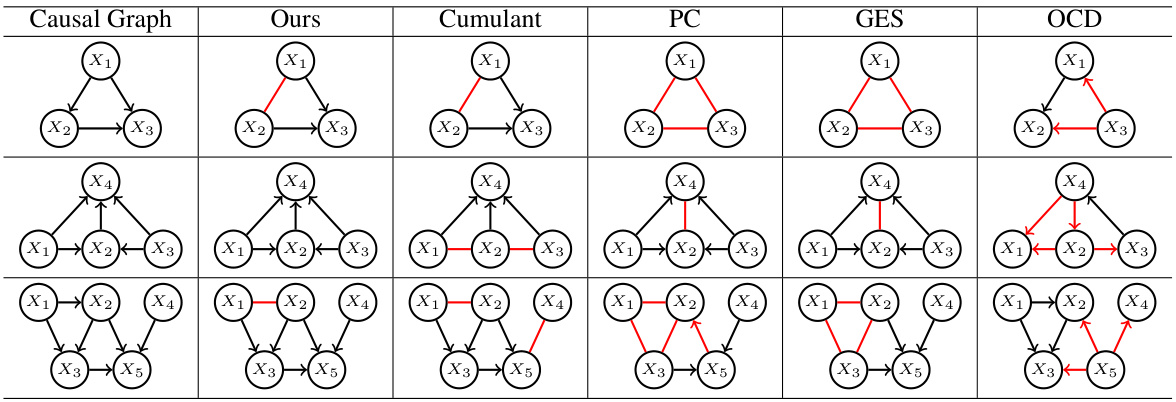

This table presents a case study comparing the performance of different causal discovery methods on three different causal graphs with 3, 4, and 5 vertices. The results illustrate which methods correctly identified the causal relationships between variables, and highlight cases where methods failed or produced incorrect directions. Red undirected edges represent correct adjacency but undetermined direction, while red directed edges represent incorrect causal direction.

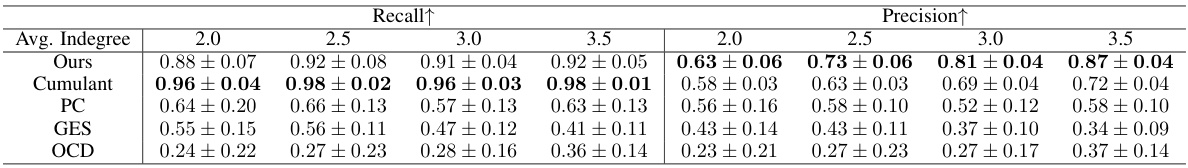

This table presents the performance of different causal discovery methods under various average in-degree rates. The metrics shown (Recall, Precision) assess the accuracy of the methods in identifying causal relationships. The average in-degree controls the sparsity of the causal structure; higher rates lead to denser structures. The results show the impact of varying graph density on the different approaches.

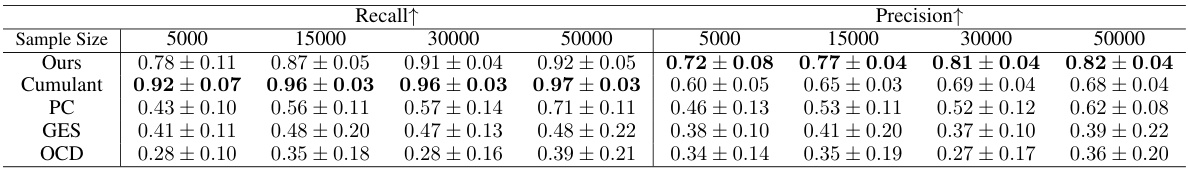

This table shows the results of a sensitivity analysis on the sample size used in the synthetic experiments. It demonstrates how the performance of the proposed PGF-based method, along with other baseline methods (Cumulant, PC, GES, and OCD), changes with varying sample sizes (5000, 15000, 30000, 50000). The metrics used for evaluation are F1 score (F1↑, higher is better) and Structural Hamming Distance (SHD↓, lower is better). The results highlight the robustness and improved accuracy of the PGF-based method compared to other approaches, particularly at larger sample sizes.

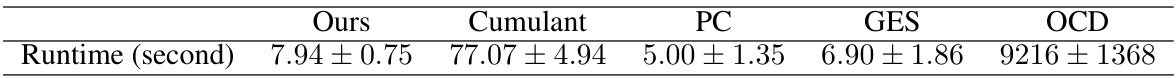

This table shows the runtime of different causal discovery methods under the default setting used in the paper’s experiments. The methods compared include the authors’ proposed method, Cumulant, PC, GES, and OCD. The runtime is measured in seconds and presented as the mean ± standard deviation. This allows for a comparison of the computational efficiency of each approach.

Full paper#