↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional neural network approaches to solving propositional satisfiability (SAT) problems face significant hurdles: they demand enormous amounts of training data and often require computationally expensive verification methods to confirm accuracy. This necessitates the development of more efficient and accurate SAT solvers. This is a challenge given the inherent complexity of SAT, which is a quintessential NP-complete problem.

To overcome these limitations, this paper introduces NeuRes, a novel neuro-symbolic approach. NeuRes leverages propositional resolution, a well-established proof system, to generate certificates of unsatisfiability and accelerate the process of finding satisfying truth assignments. It combines certificate-driven training with expert iteration and an attention-based architecture, demonstrating superior performance compared to existing neural network based SAT solvers. This innovative technique drastically reduces the need for large datasets while significantly improving accuracy. The self-improving nature of NeuRes’s workflow shows its adaptability and potential for broader application in other complex fields.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it presents a novel neuro-symbolic approach to solving the NP-complete problem of propositional satisfiability (SAT). It directly addresses the challenges of requiring massive training data and computationally expensive verification for neural network-based SAT solvers. By improving data efficiency and accuracy, this research opens new avenues for neuro-symbolic AI and offers a potentially impactful methodology for other complex problems.

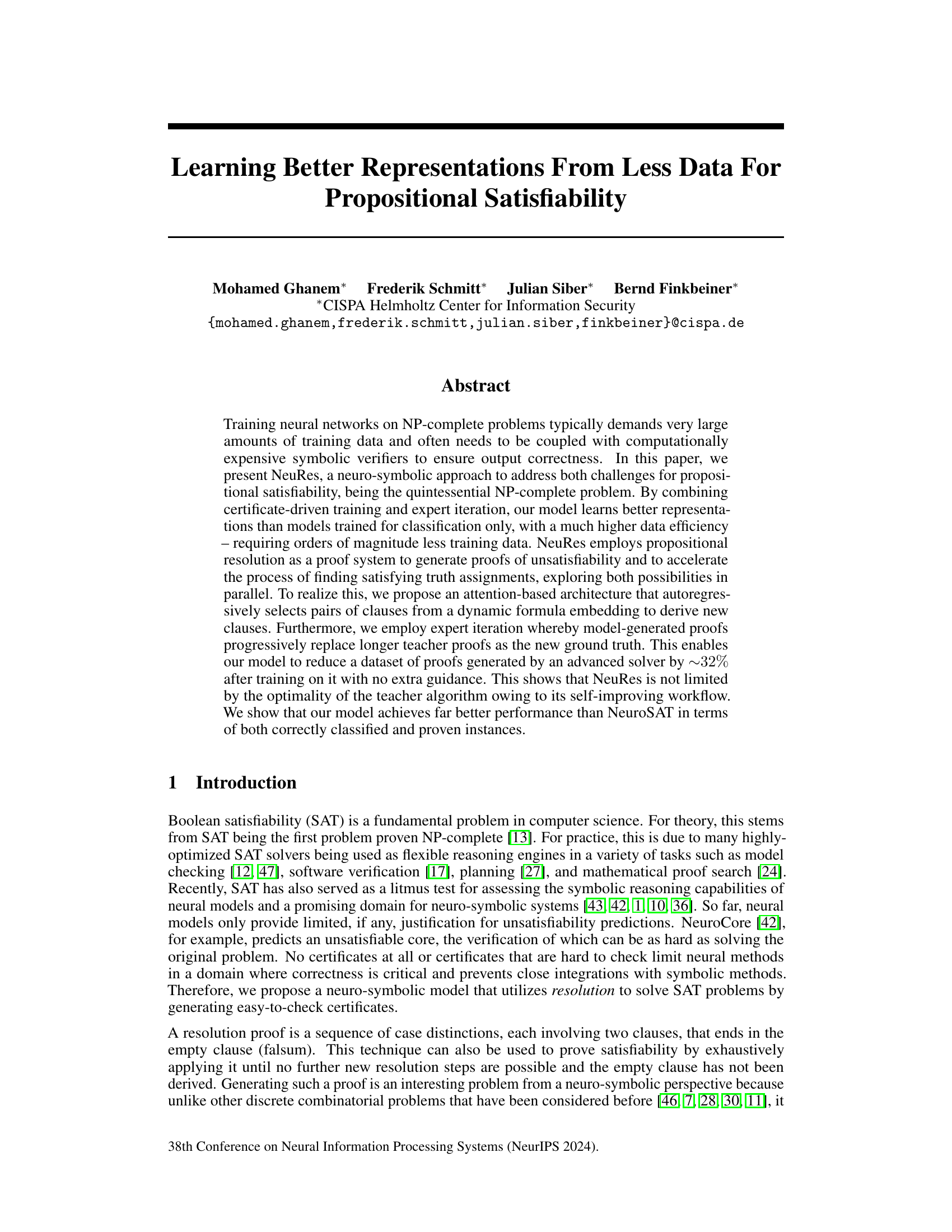

Visual Insights#

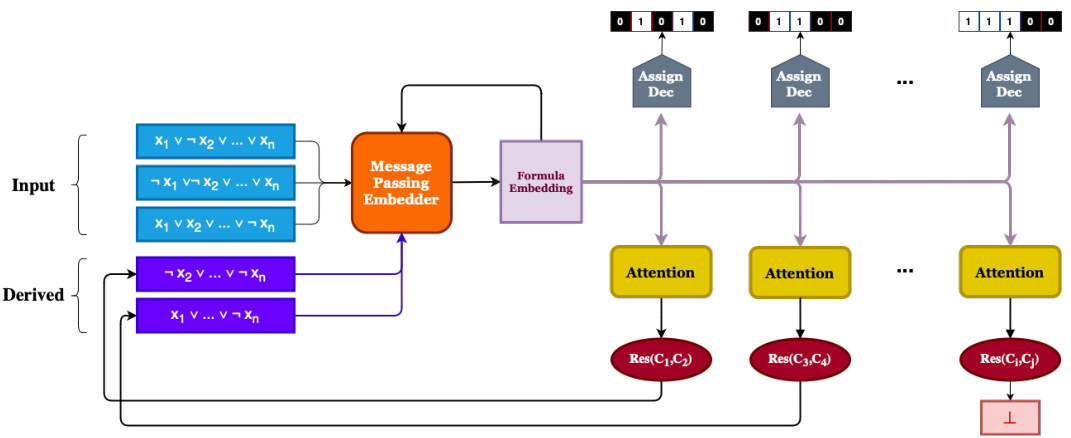

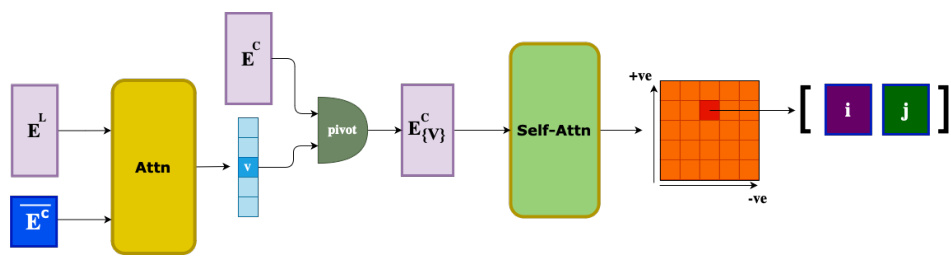

The figure shows the overall architecture of the NeuRes model. The input is a CNF formula. The formula is first processed by a Message-Passing Embedder, which generates embeddings for the clauses and literals. These embeddings are then fed into two parallel tracks: an attention network that selects clause pairs for resolution and an assignment decoder that attempts to find a satisfying assignment. The attention network iteratively selects clause pairs and generates new clauses through resolution. Both tracks operate on the shared formula embedding, and NeuRes outputs either a satisfying assignment or a resolution proof of unsatisfiability.

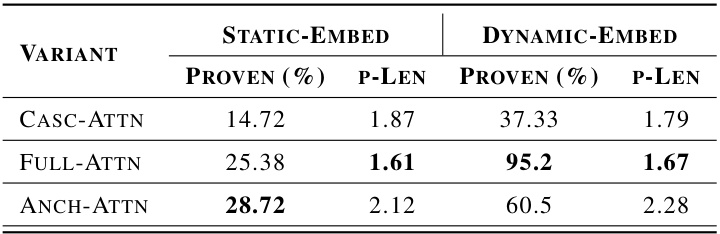

This table presents the performance comparison of three different attention mechanisms (Casc-Attn, Full-Attn, Anch-Attn) used in the NeuRes model for solving unsatisfiable propositional logic problems. The performance is evaluated using two embedding strategies: static and dynamic. The ‘Proven (%)’ column indicates the percentage of problems solved correctly, while the ‘P-LEN’ column shows the average length of the generated resolution proofs relative to the teacher’s proofs. The results show that the dynamic embedding strategy significantly improves the performance of all three attention mechanisms.

In-depth insights#

Neuro-Symbolic SAT#

Neuro-symbolic approaches to Satisfiability (SAT) problems aim to leverage the strengths of both neural networks and symbolic reasoning methods. Neural networks excel at learning complex patterns from data, while symbolic methods offer explainability and the ability to generate verifiable proofs. A neuro-symbolic SAT solver might use a neural network to learn efficient heuristics for guiding a symbolic SAT solver, such as a resolution prover. This could involve the neural network predicting which clauses are most likely to lead to a quick resolution refutation, dramatically improving the efficiency of the symbolic solver. Alternatively, the neural network could learn to generate the resolution proof itself, making the process more efficient. A key advantage is the potential for improved data efficiency. Traditional neural approaches to SAT often require massive datasets, while a neuro-symbolic model could potentially learn from smaller, higher-quality datasets by leveraging the constraints imposed by symbolic reasoning. Explainability and proof generation are further benefits since symbolic methods can provide human-understandable justifications for the SAT solver’s output. The major challenge lies in effectively integrating neural and symbolic components, potentially requiring innovative architectures that seamlessly bridge the two paradigms. The ultimate goal is to create a powerful and efficient SAT solver that combines the learning capabilities of neural networks with the reliability and transparency of symbolic methods.

Cert.-Driven Training#

Certificate-driven training, a core concept in the paper, revolutionizes the training of neural networks for NP-complete problems like SAT solving. Instead of relying solely on classification accuracy, it leverages the correctness of generated certificates (resolution proofs or satisfying assignments) as the primary feedback signal. This shifts the focus from merely predicting satisfiability to actually proving it, leading to more robust and insightful learning. The method demonstrably improves data efficiency, requiring orders of magnitude less training data compared to traditional classification-based approaches. Furthermore, the use of certificates allows for rigorous verification of the network’s output, significantly enhancing trustworthiness, a critical aspect often lacking in purely neural SAT solvers. The integration of expert iteration, where model-generated proofs progressively replace teacher proofs, further enhances the learning process and leads to shorter, more efficient certificates. This self-improving aspect is a powerful innovation that goes beyond relying on the optimality of a pre-defined teacher algorithm.

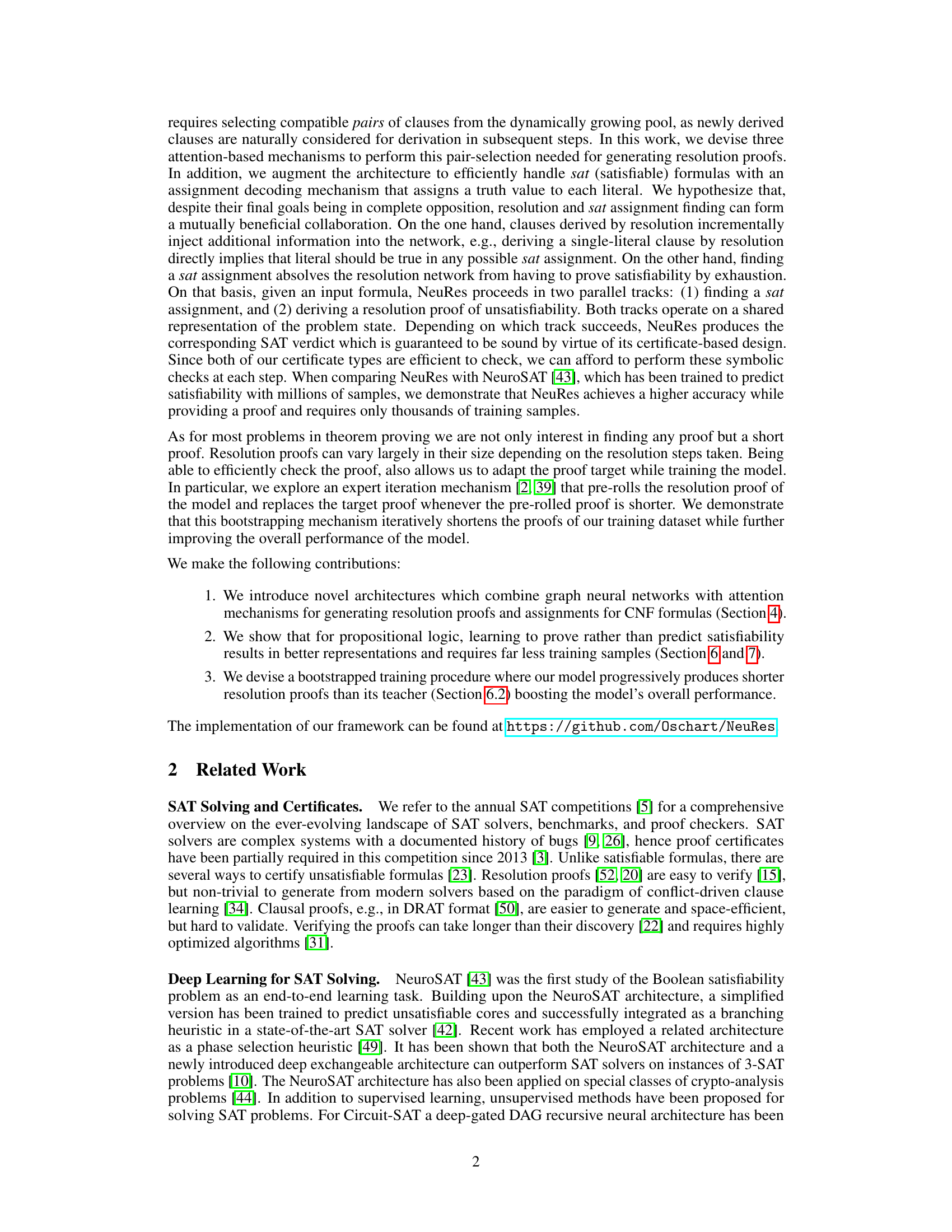

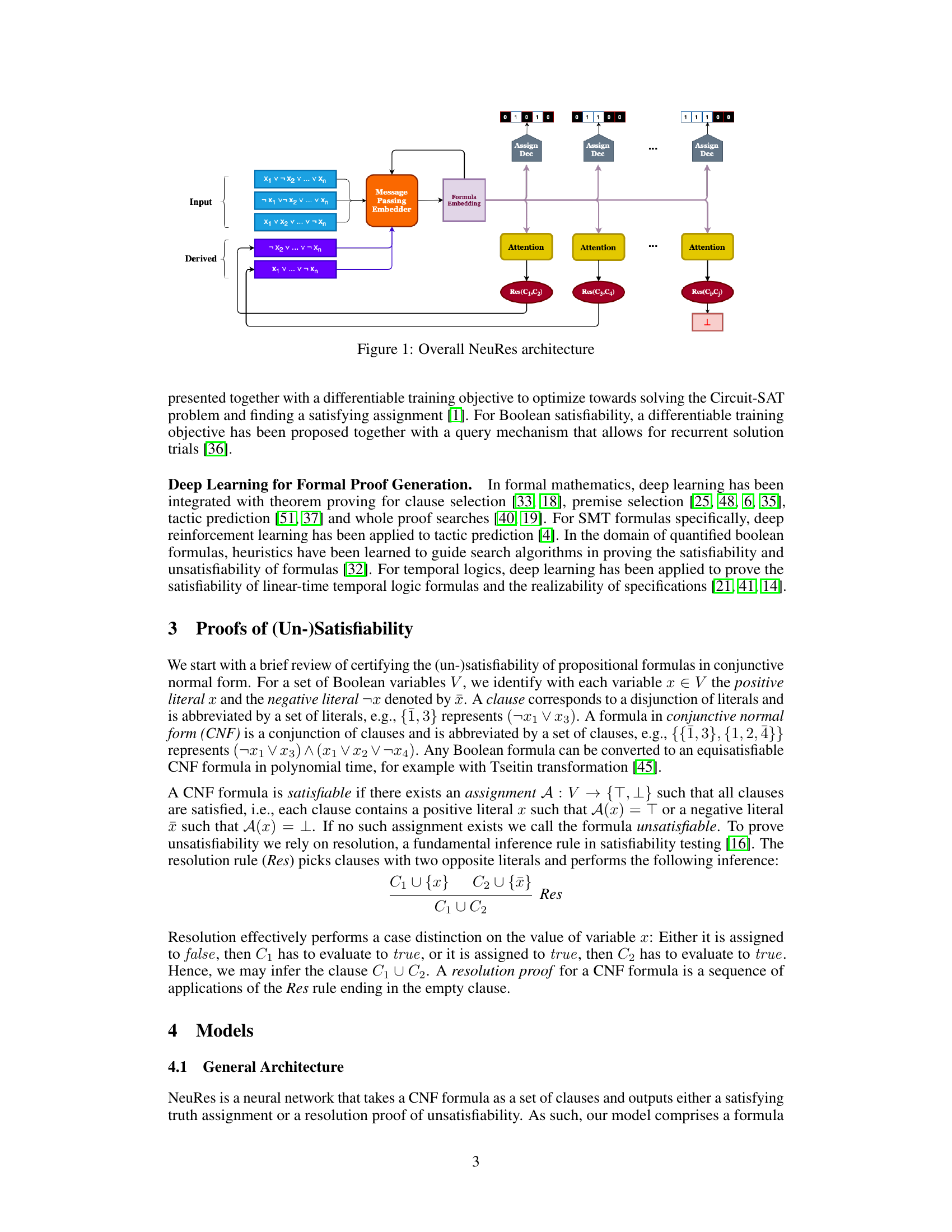

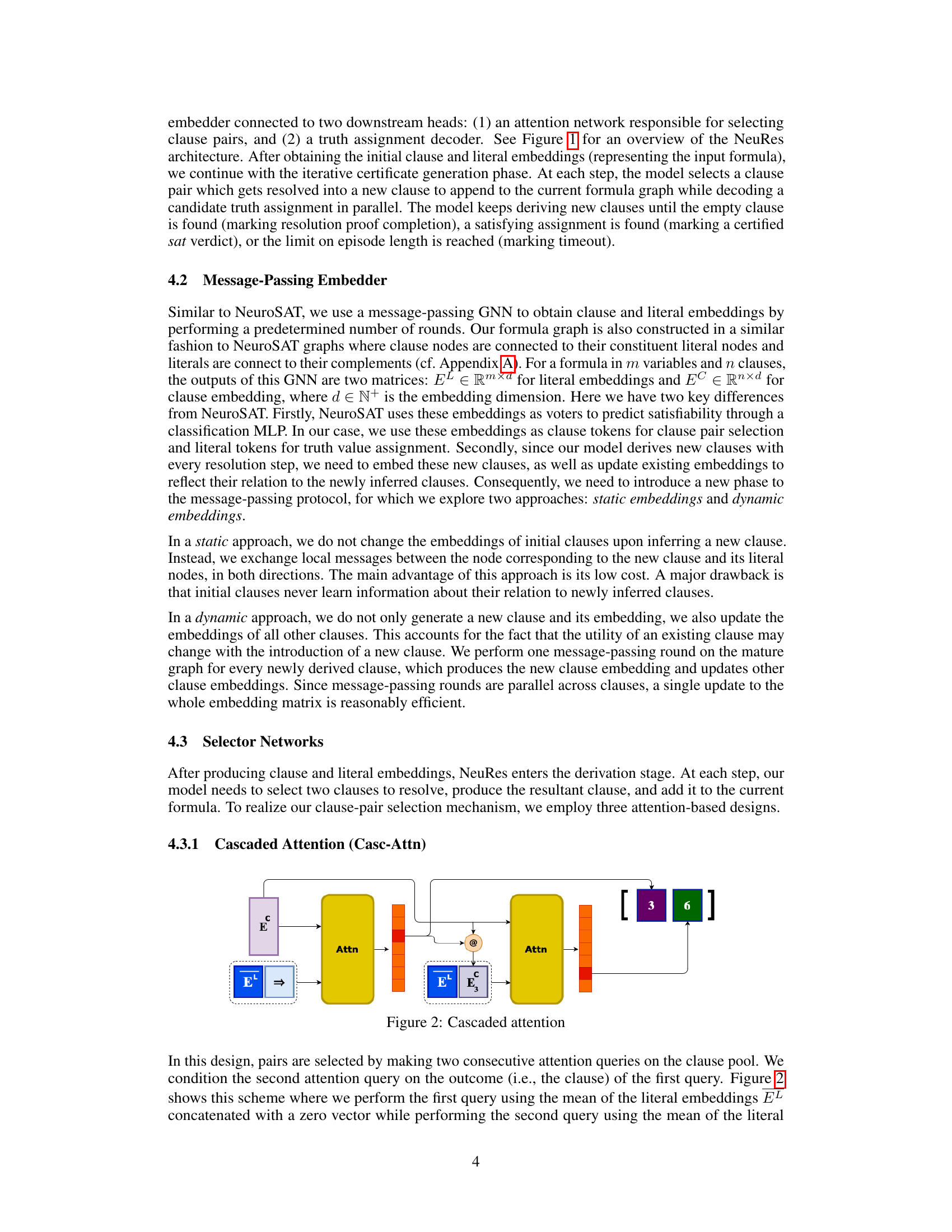

Attention Mechanisms#

The paper explores various attention mechanisms for efficient clause pair selection in generating resolution proofs for propositional satisfiability problems. Three main attention mechanisms are proposed: cascaded attention (Casc-Attn), which performs sequential attention queries; full self-attention (Full-Attn), applying self-attention across all clauses; and anchored self-attention (Anch-Attn), focusing attention on clauses containing specific anchor variables. Casc-Attn offers simplicity but lacks the simultaneous consideration of clause pairs inherent in resolution, while Full-Attn offers comprehensive consideration but suffers from quadratic complexity. Anch-Attn provides a balance, limiting complexity by focusing on relevant clauses. The choice of attention mechanism significantly impacts the efficiency and performance of the system, with dynamic embeddings generally improving results over static embeddings. The paper’s experimental results highlight the need for careful consideration of computational costs and the nuanced relationships between attention mechanisms and the overall neuro-symbolic architecture.

Proof Bootstrapping#

Proof bootstrapping, as presented in the context of the research paper, is a powerful technique for enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of neuro-symbolic models. By iteratively replacing longer teacher proofs with shorter, model-generated proofs, the method effectively boostraps the model’s learning, leading to improved representations. This self-improving workflow not only results in higher data efficiency but also overcomes limitations imposed by the optimality of the teacher algorithm. The process leverages the ability to check the validity of proofs efficiently, allowing the model to learn from progressively improved examples and refine its proof generation capabilities. Reduced proof lengths translate to both reduced computational costs and improved generalization, as the model learns to find more concise and elegant solutions. The iterative nature of the approach is key, as the model’s understanding evolves with each cycle, showcasing the synergistic potential of combining neural networks with symbolic reasoning. Ultimately, proof bootstrapping demonstrates the power of active learning and self-correction in neuro-symbolic systems, leading to significantly enhanced performance with less training data.

Scalability & Limits#

A crucial aspect of evaluating any novel approach to solving NP-complete problems like SAT is assessing its scalability. The paper’s approach, while showing promise with smaller problem instances, needs further investigation into its ability to handle significantly larger inputs. Extrapolating the performance observed on smaller datasets to larger ones is risky, as computational cost and memory requirements can grow exponentially. The authors acknowledge this limitation, and it is important to investigate the impact of various architectural choices (e.g., attention mechanism selection, dynamic vs. static embeddings) on scalability. Furthermore, the effectiveness of the bootstrapping technique in shortening proof lengths, while effective in initial experiments, requires thorough analysis regarding its scalability. Does this technique eventually reach a point of diminishing returns? Do the resulting shorter proofs translate to significantly improved performance in truly large-scale problem instances? Finally, understanding the limits of the approach in terms of problem characteristics (e.g., clause density, variable distribution) is vital to provide a complete picture of the method’s practical applicability and identify situations where it might struggle or fail.

More visual insights#

More on figures

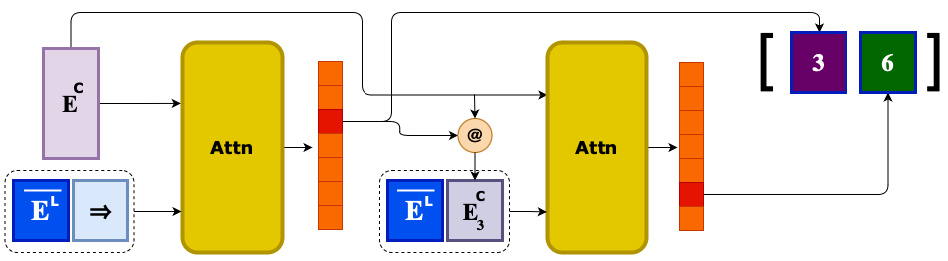

This figure illustrates the mechanism of cascaded attention used in the NeuRes model for clause pair selection. It involves two consecutive attention queries on the clause pool. The first query uses the mean of the literal embeddings concatenated with a zero vector to select a clause. The second query, conditioned on the outcome (selected clause) of the first query, uses the mean of the literal embeddings concatenated with the embedding vector of the clause selected in the first query to select a second clause. The selected pair of clauses is then used for resolution.

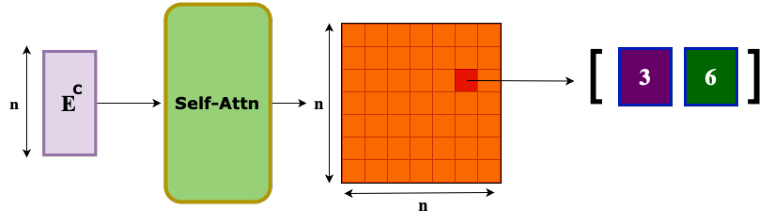

This figure illustrates the mechanism of Full Self-Attention. Clause embeddings are input to a self-attention layer, producing an attention matrix. The entry with the maximum attention score determines the clause pair selected for resolution. The figure highlights the selected pair (3, 6) along with the attention matrix.

This figure illustrates the Anchored Self-Attention mechanism used in the NeuRes model for clause pair selection. It shows how an attention mechanism first selects an anchor variable (v) and then uses a self-attention mechanism on clauses containing either the positive (v) or negative (-v) literal of that variable. The result is a reduced attention grid, improving efficiency by focusing only on relevant clause pairs for resolution.

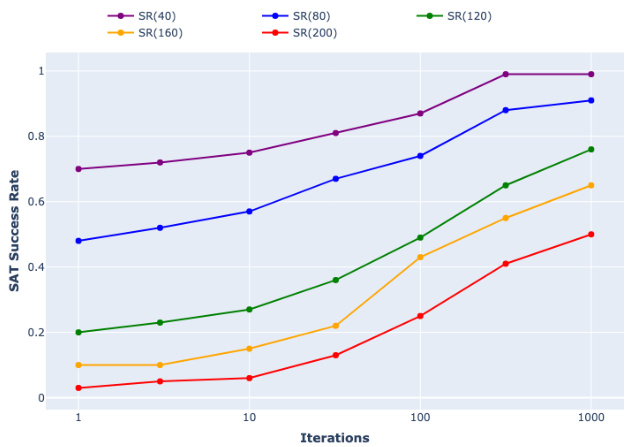

This figure shows the SAT success rate over various iterations for different problem sizes (SR(40), SR(80), SR(120), SR(160), SR(200)). The x-axis represents the number of iterations, and the y-axis shows the success rate (percentage of problems solved successfully). It demonstrates the model’s scalability and performance on larger problems. The success rate generally increases as the number of iterations increases, indicating the effectiveness of the learning process.

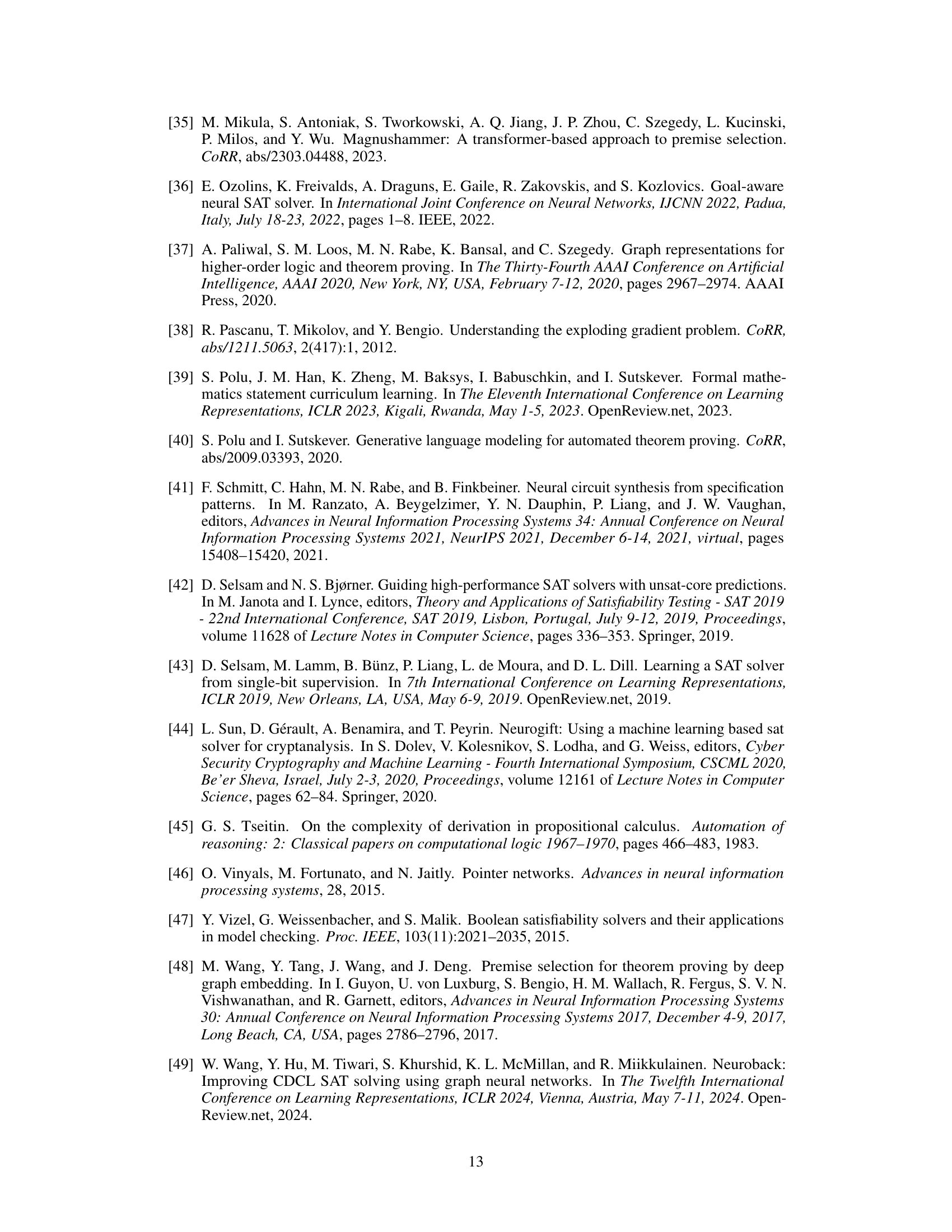

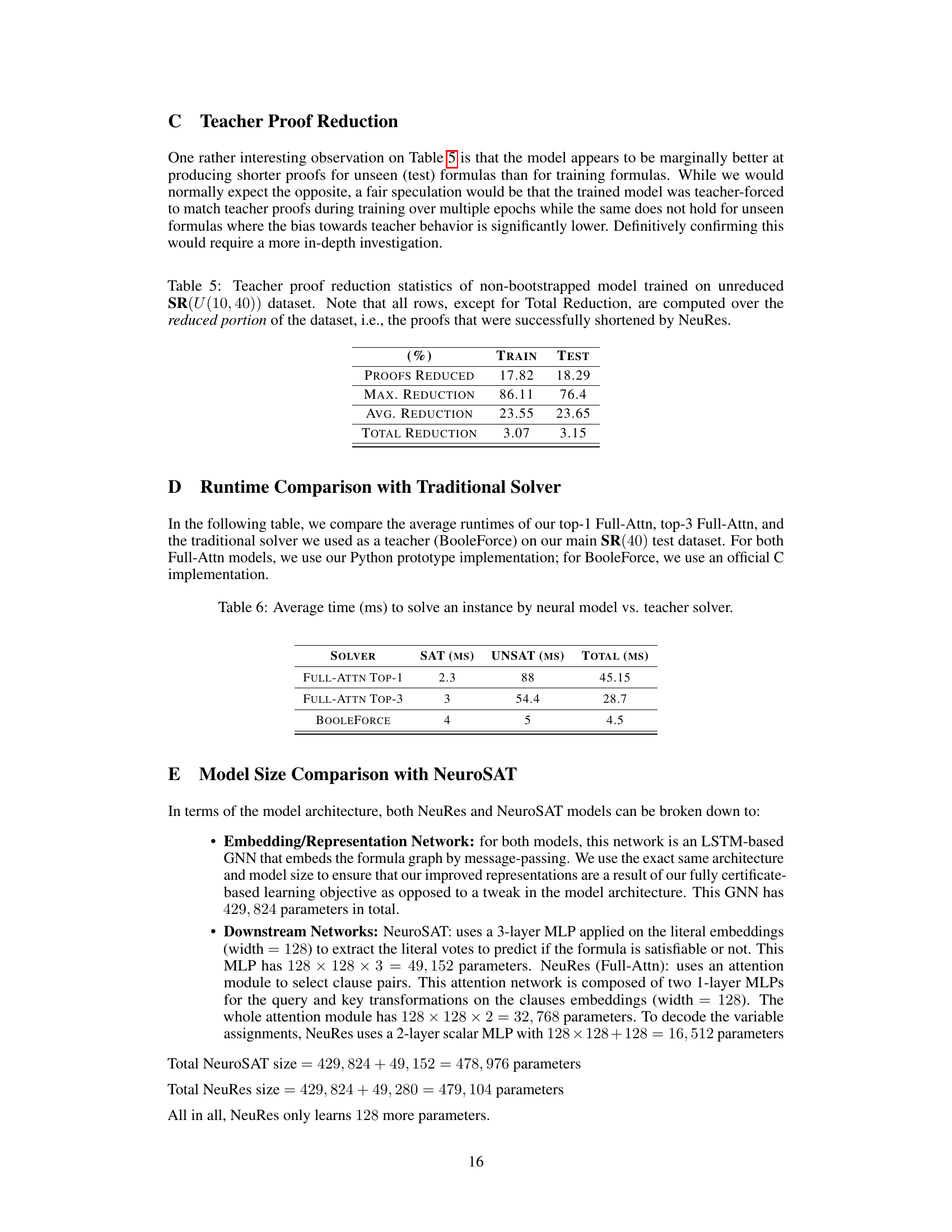

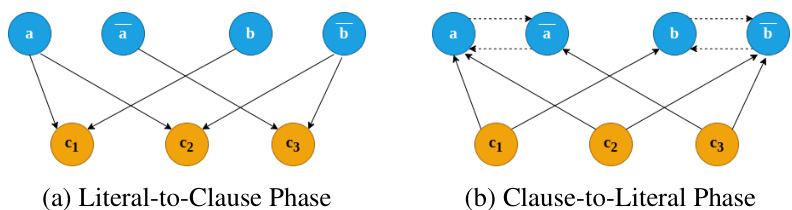

NeuroSAT-style formula graphs have two designated node types: clause nodes connected to the literal nodes corresponding to their constituent literals. Each message-passing round involves two exchange phases: (1) Literal-to-Clause, and (2) Clause-to-Literal. This construction is particularly efficient as it allows the message-passing protocol to cover the entire graph connectivity in at most |V| + 1 rounds where V is the set of variables in the formula.

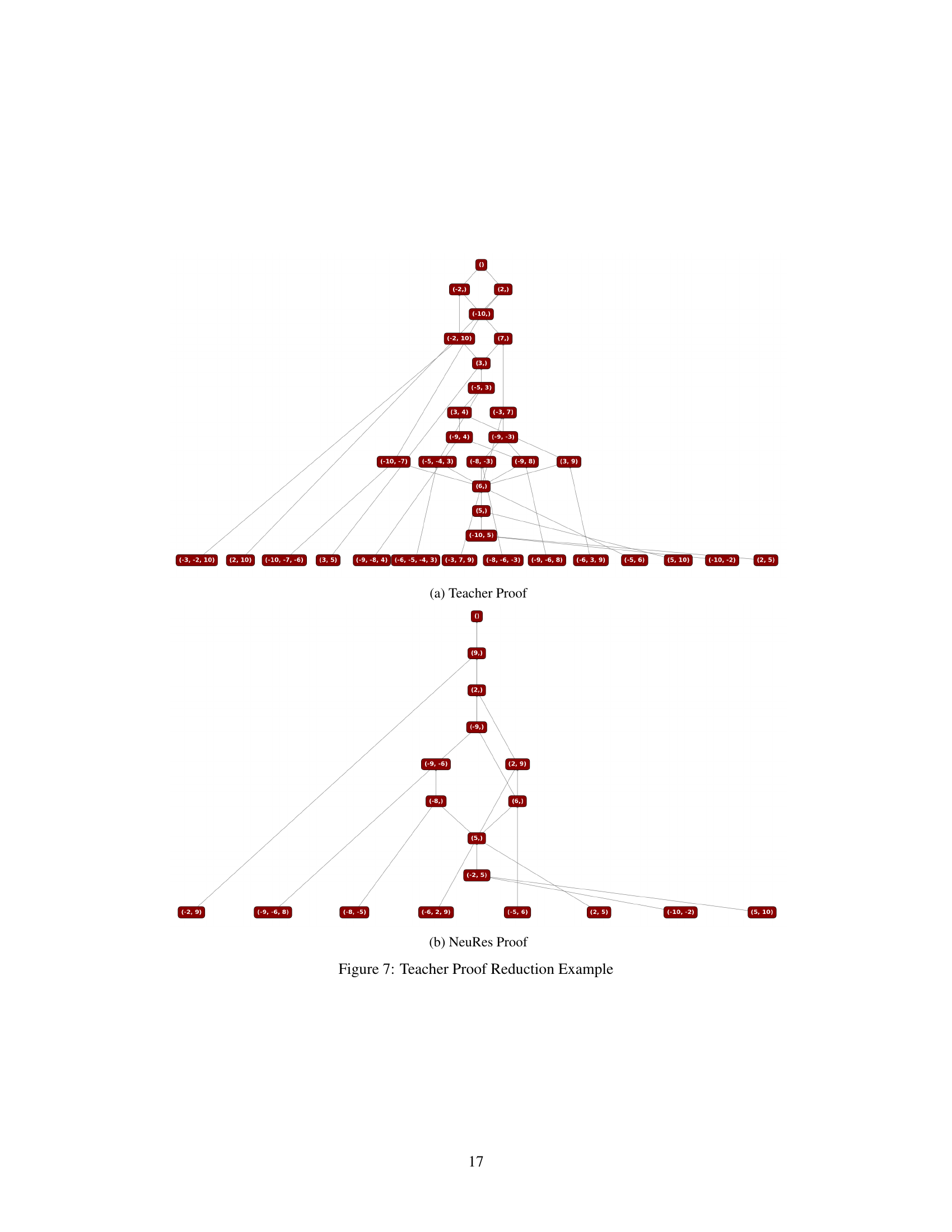

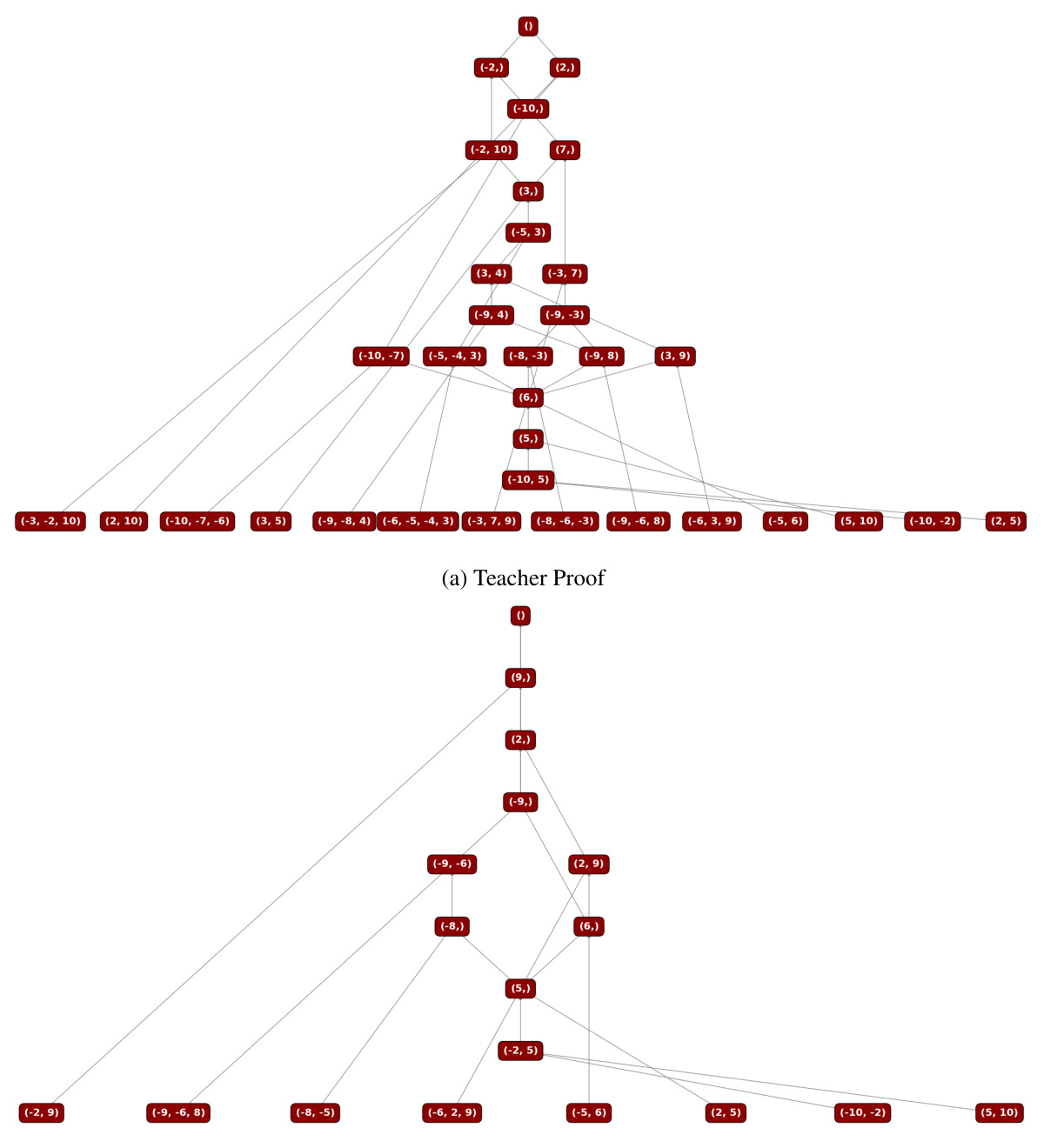

This figure shows an example of how NeuRes, through its bootstrapping mechanism, reduces the length of a resolution proof. The figure displays two resolution proofs: (a) the original, longer teacher proof generated by a traditional SAT solver; and (b) the shorter proof produced by NeuRes after training with the bootstrapping technique. The reduction in proof length highlights NeuRes’s ability to learn and improve upon the teacher algorithm’s output, contributing to improved performance and data efficiency.

More on tables

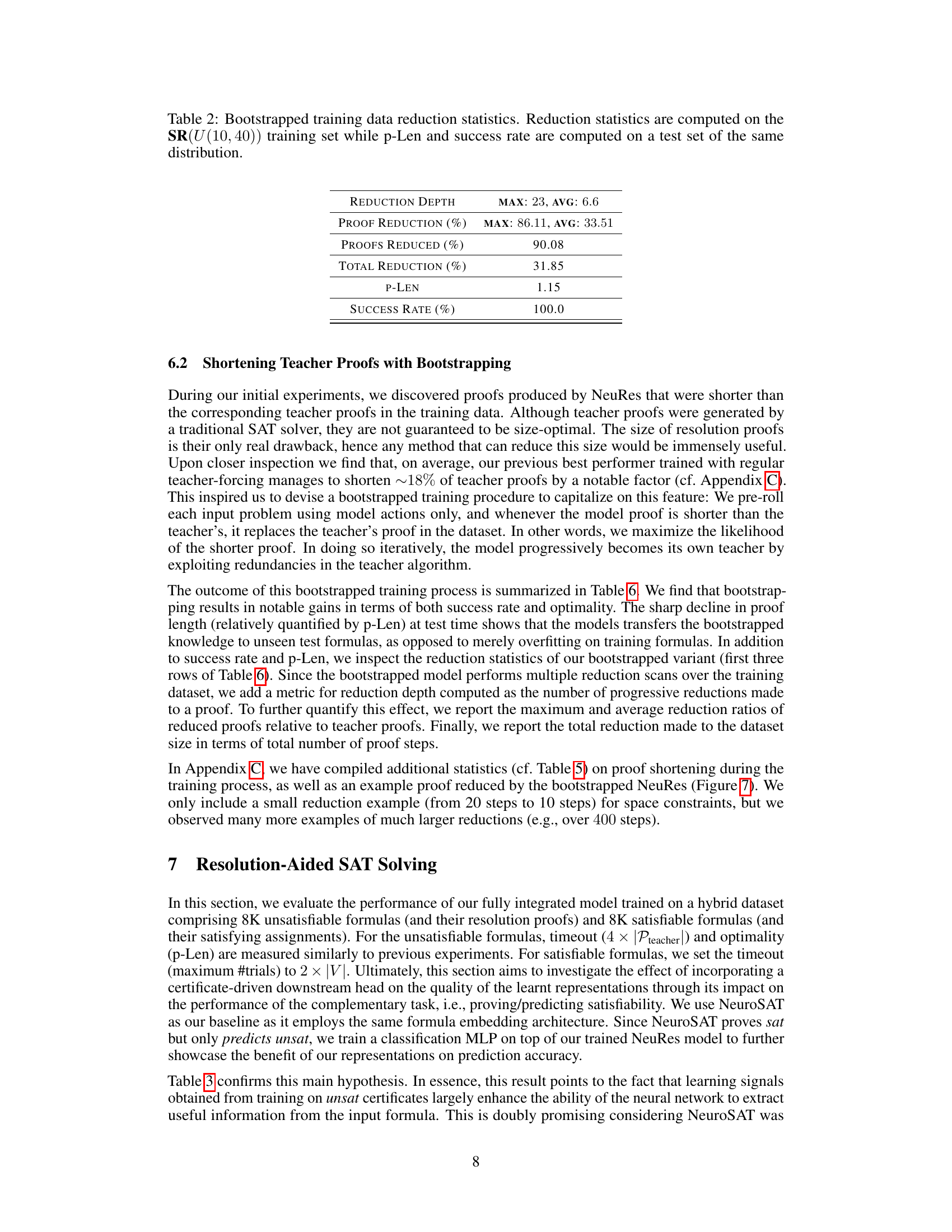

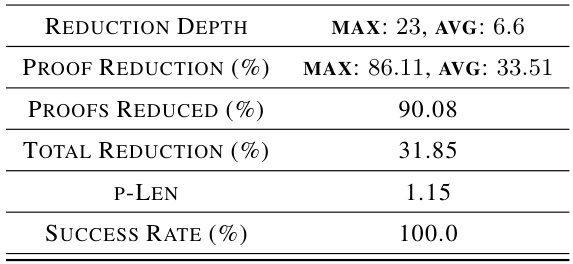

This table presents the results of applying a bootstrapped training approach to reduce the size of resolution proofs generated by the model. The table shows various statistics, including the reduction depth (the number of times proofs were iteratively shortened), the percentage of proofs reduced, and the average reduction in proof length. The p-Len metric shows the average length of the model-generated proofs relative to the teacher proofs. The success rate indicates the percentage of problems solved within the time limit. All these statistics are reported for both training and test sets of Boolean formulas. This demonstrates the impact of iterative proof shortening during training on the model’s performance on unseen test problems.

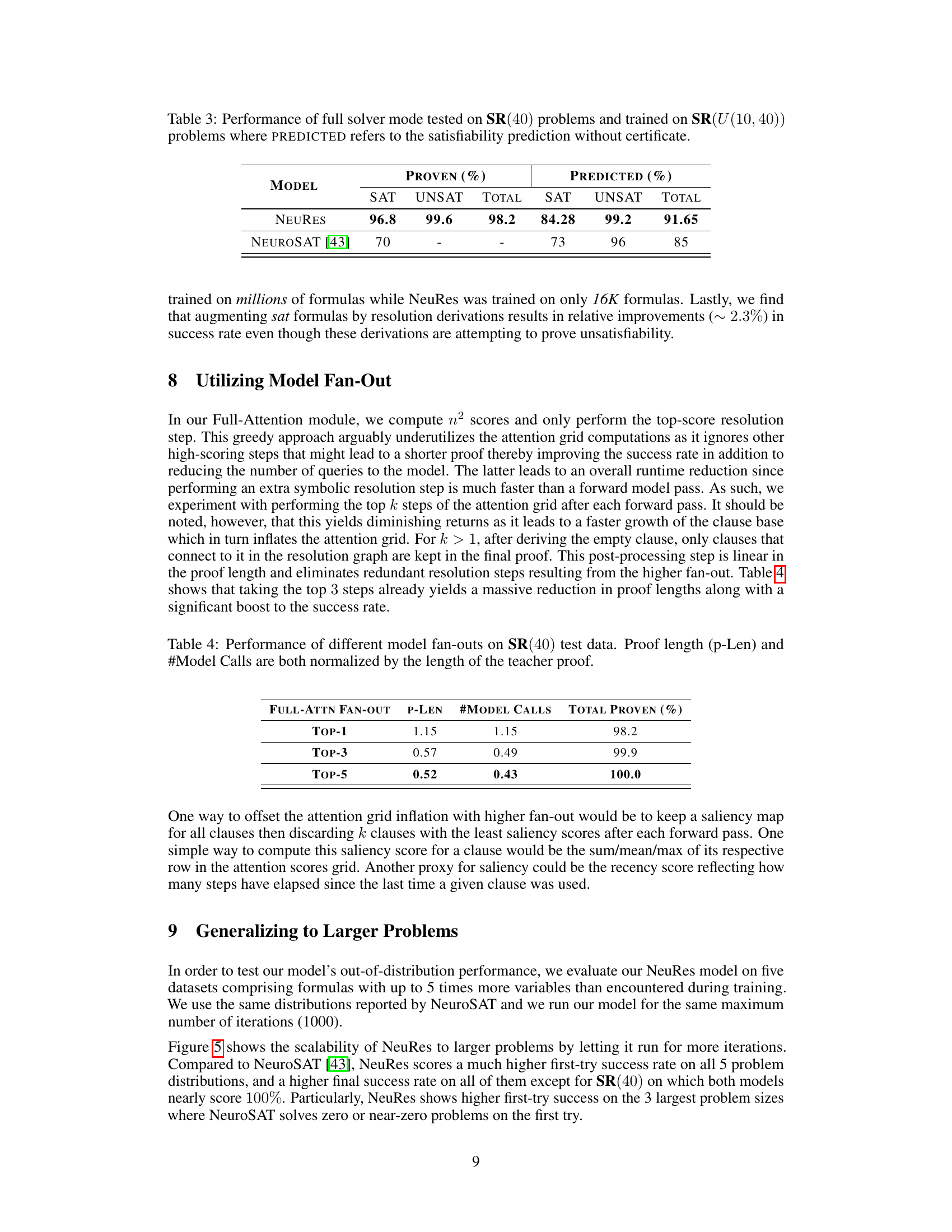

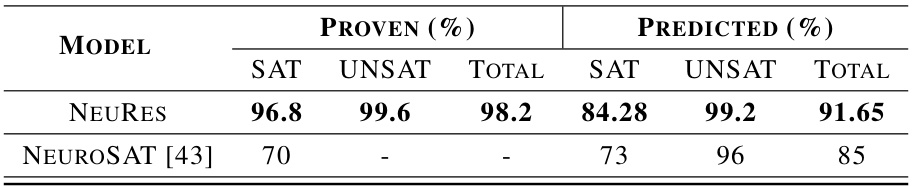

This table compares the performance of NeuRes and NeuroSAT on SR(40) problems. NeuRes was trained on SR(U(10, 40)) data. The table shows the percentage of problems solved (PROVEN) and the accuracy of satisfiability prediction (PREDICTED) for both SAT and UNSAT instances. The ‘PROVEN’ column indicates the success rate for finding satisfying assignments or resolution proofs, while the ‘PREDICTED’ column demonstrates the model’s accuracy when directly predicting satisfiability without generating a certificate.

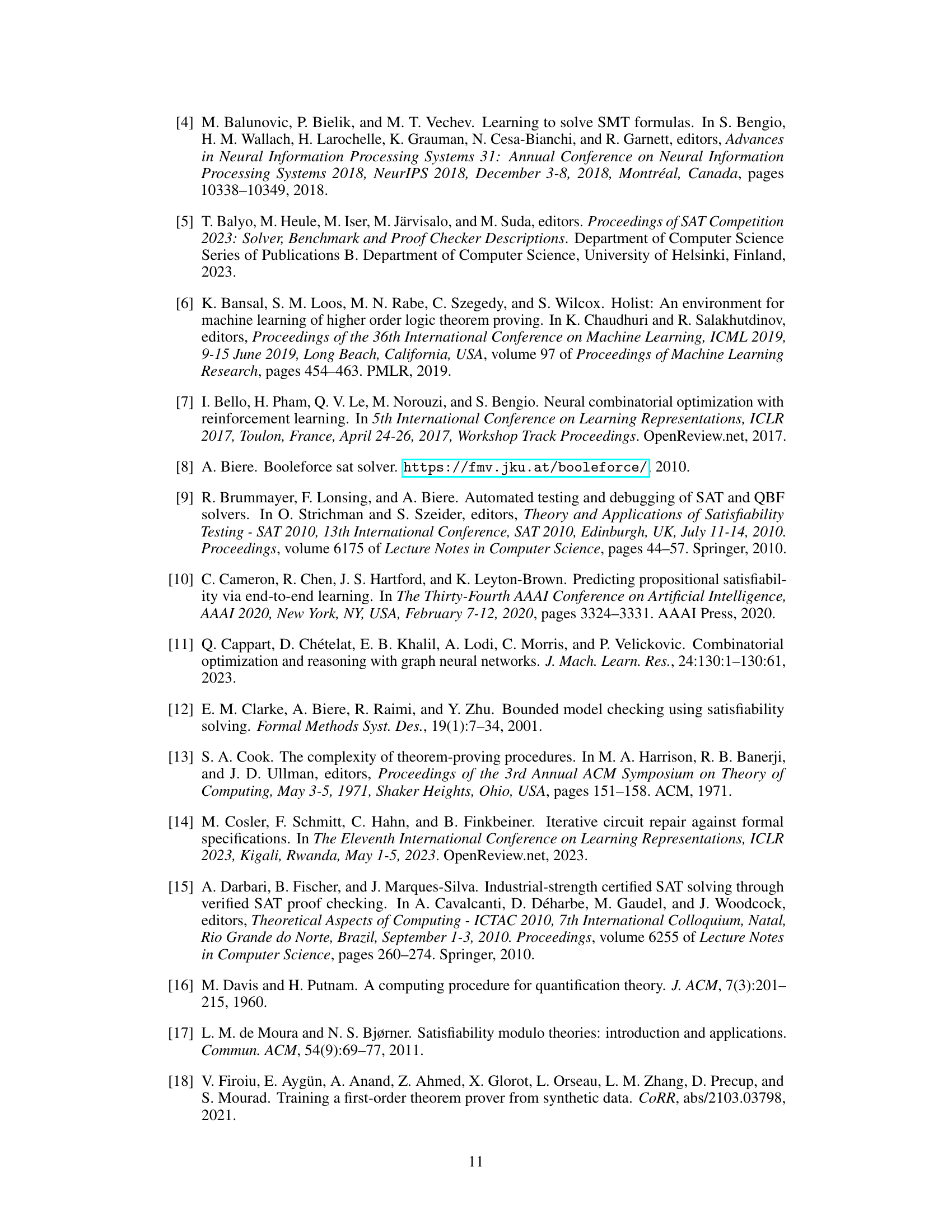

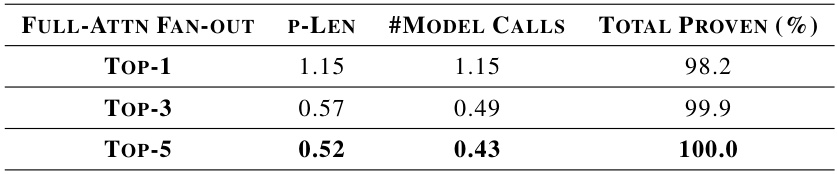

This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating the impact of different model fan-out strategies on the performance of the Full-Attention model. The experiment was conducted on SR(40) test problems. The table shows the average proof length (p-Len), the number of model calls, and the total percentage of problems successfully solved for three different fan-out settings: TOP-1 (selecting only the top-scoring resolution step), TOP-3 (selecting the top three), and TOP-5 (selecting the top five). The results demonstrate that increasing the fan-out can lead to shorter proofs and higher success rates but also increases model calls.

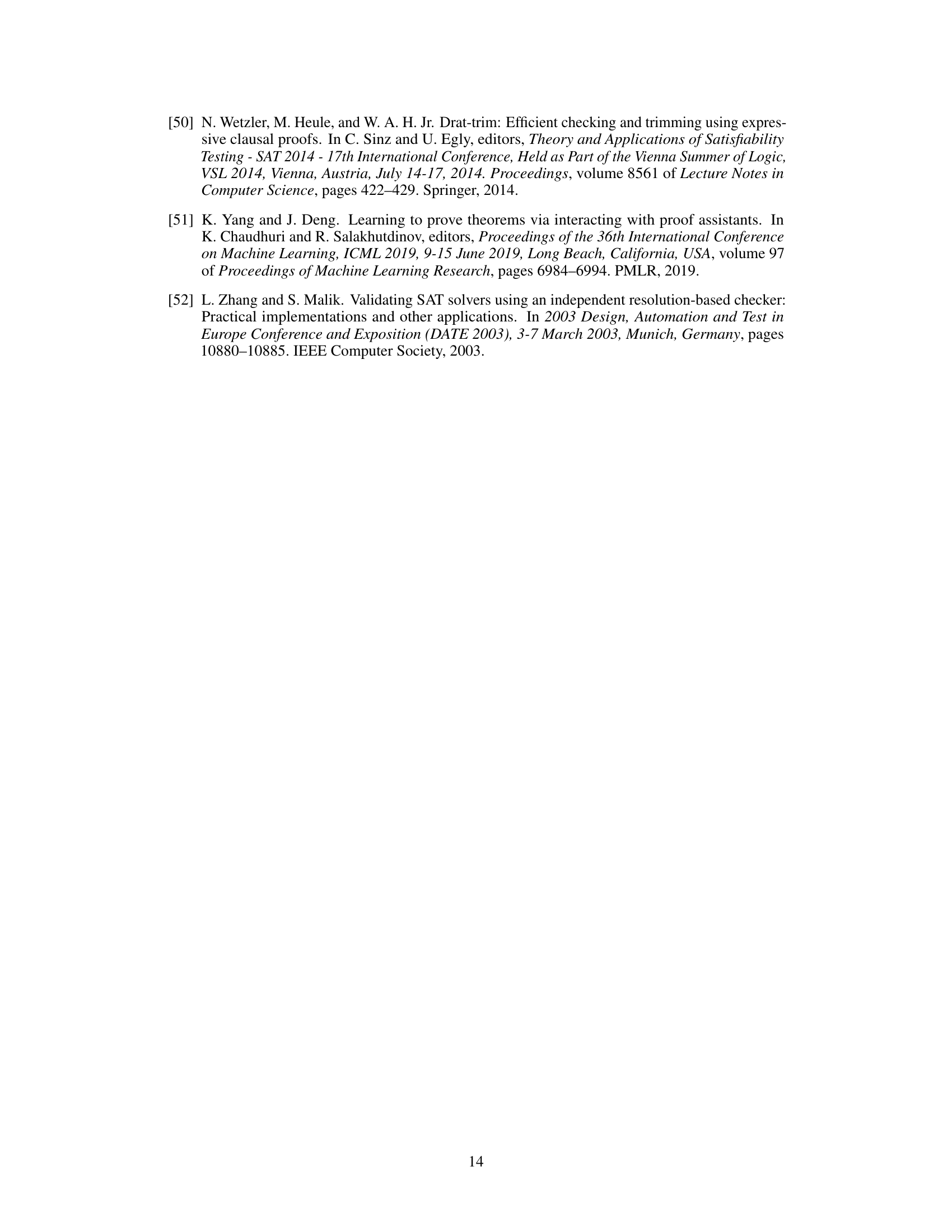

This table presents the results of a non-bootstrapped model’s ability to shorten teacher proofs. It shows the percentage of proofs shortened, the maximum and average percentage reduction achieved, and the overall reduction in the total number of proof steps. The data is separated into training and testing sets, highlighting the model’s generalization capabilities.

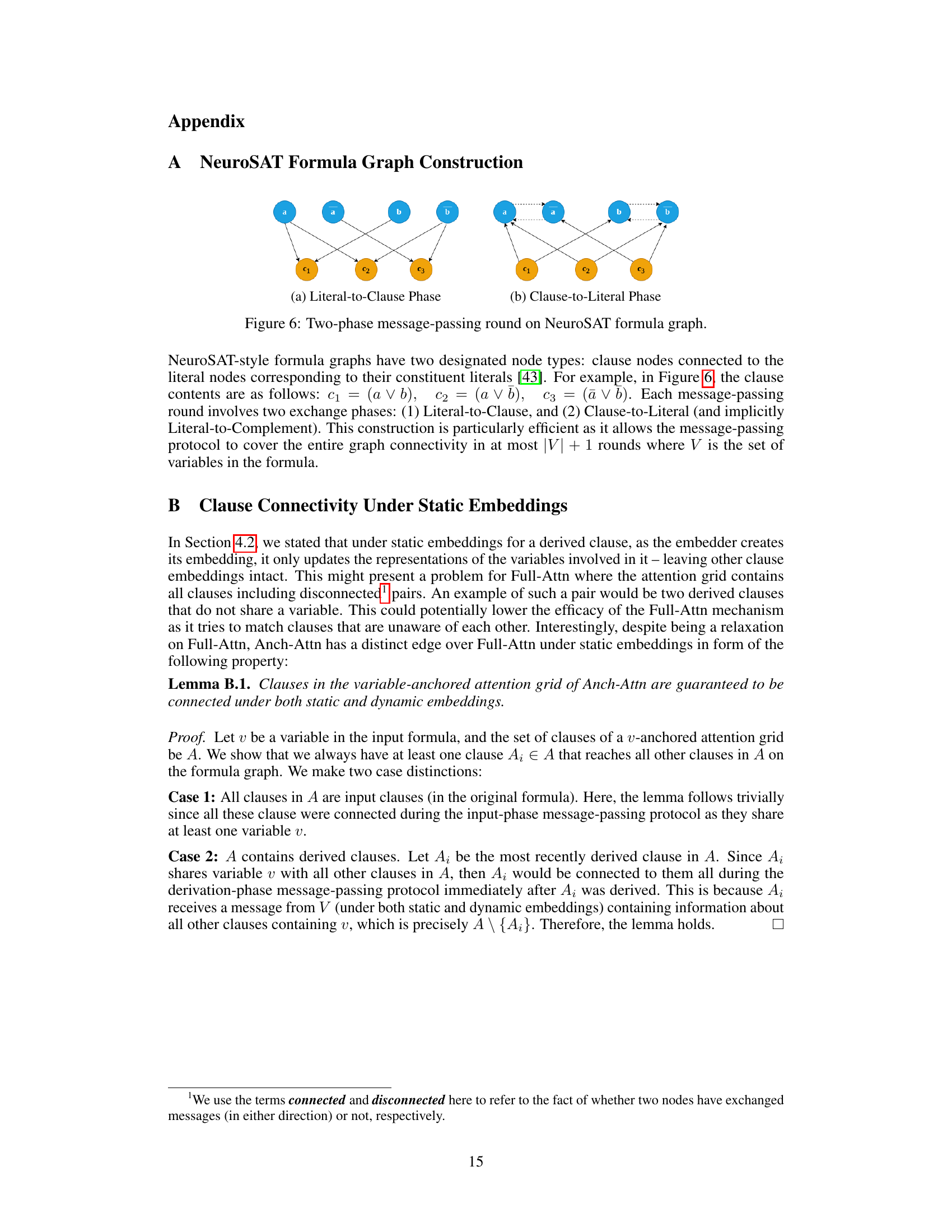

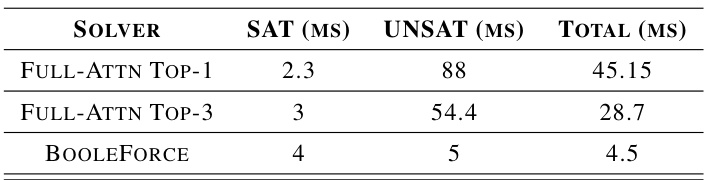

This table compares the average time in milliseconds taken by three different methods to solve a single instance of a problem. The methods compared are: the top-1 Full-Attention model (selecting the single best resolution step), the top-3 Full-Attention model (selecting the top three resolution steps), and Booleforce, a traditional SAT solver. The time is broken down for satisfiable (SAT) and unsatisfiable (UNSAT) instances and the total time across all instance types is reported.

Full paper#