↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

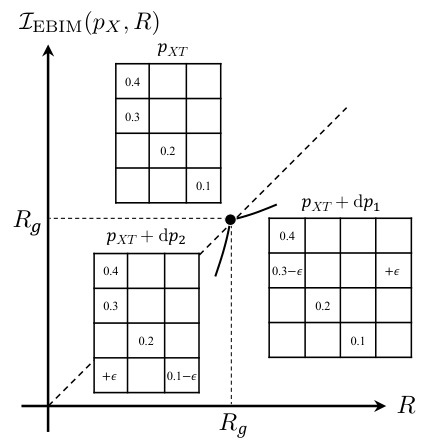

Traditional lossy compression methods often struggle when the reconstructed data distribution differs significantly from the original. This paper tackles this challenge by introducing a new framework: Minimum Entropy Coupling with Bottleneck (MEC-B). MEC-B incorporates a bottleneck to manage the stochasticity during compression, making it particularly useful for applications requiring joint compression and retrieval, or those affected by data processing.

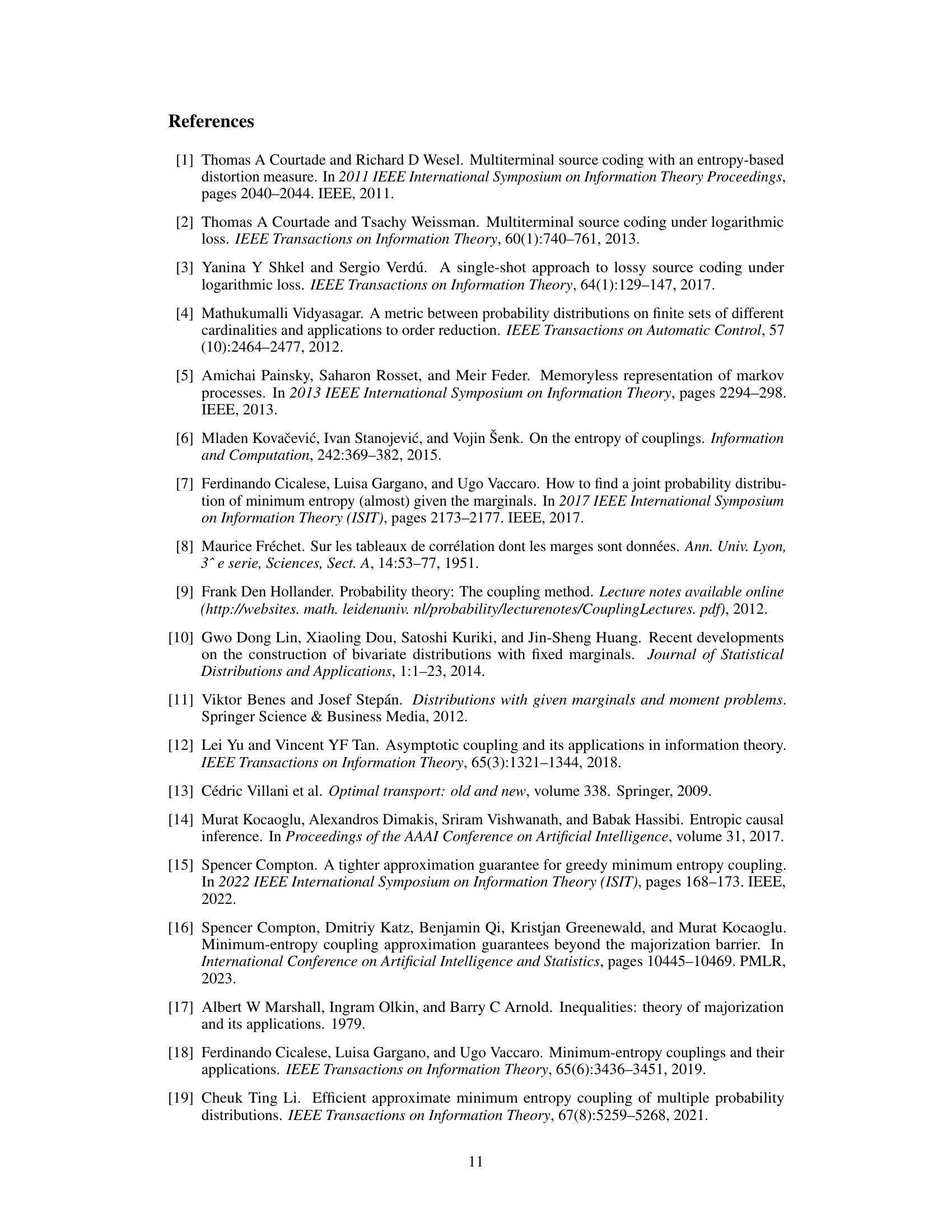

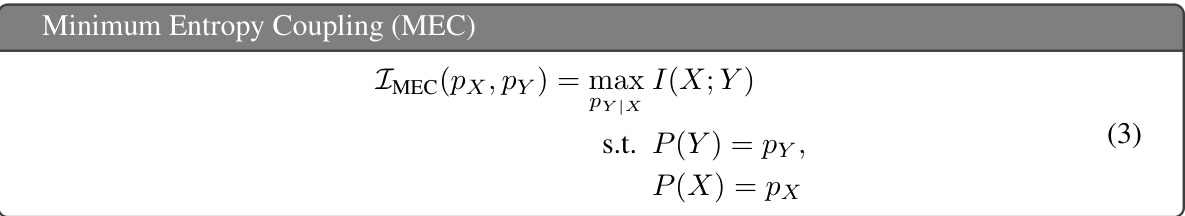

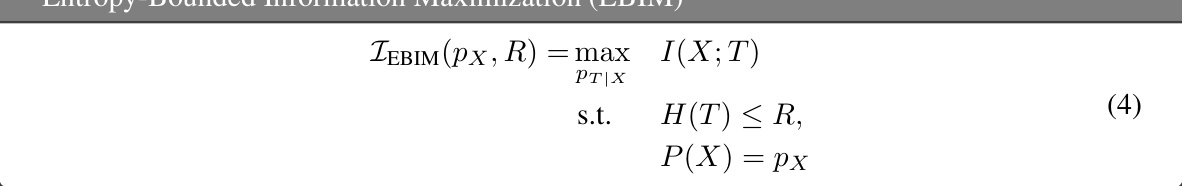

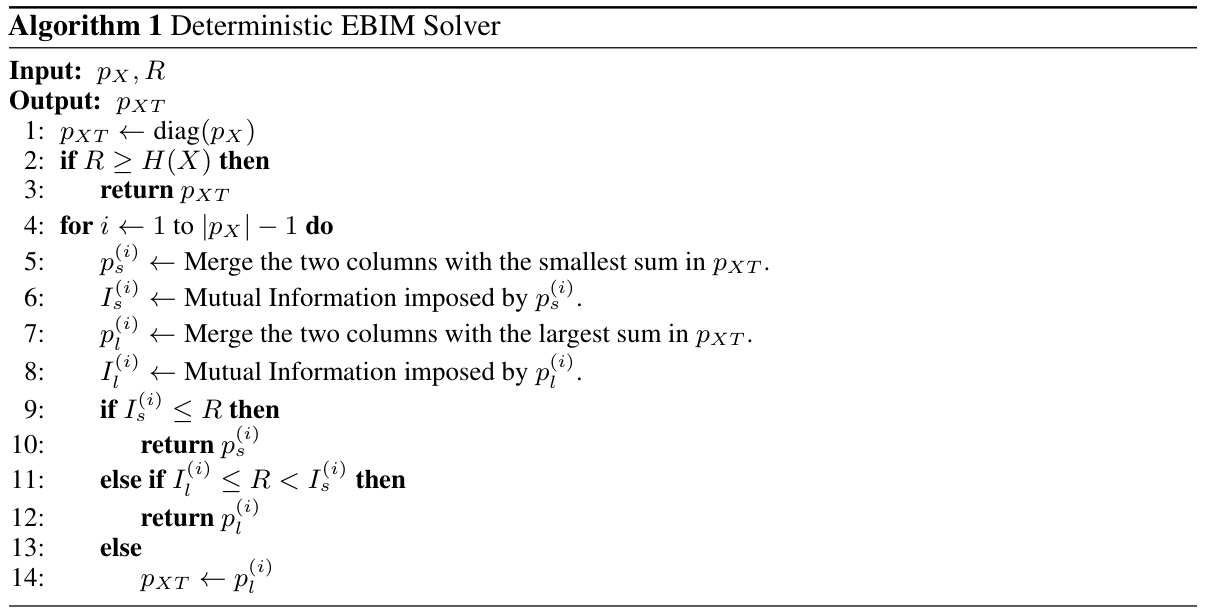

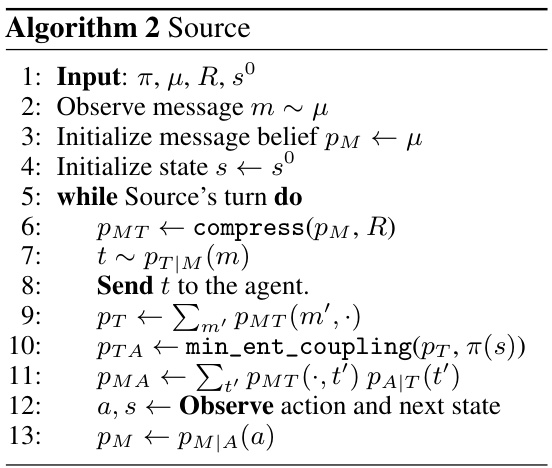

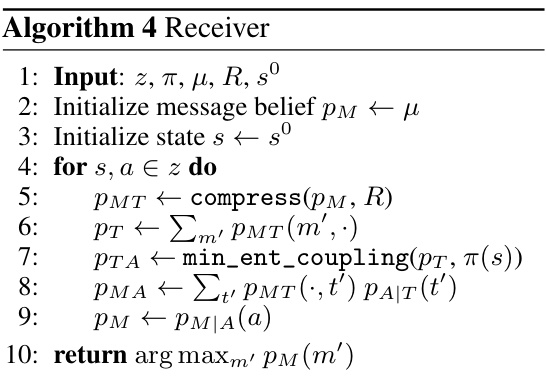

The core of the paper lies in decomposing MEC-B into two distinct optimization problems: Entropy-Bounded Information Maximization (EBIM) for the encoder and Minimum Entropy Coupling (MEC) for the decoder. It proposes a greedy algorithm for EBIM, which is proven to perform well. The authors provide a thorough theoretical analysis, giving valuable insights into the nature of this challenging problem and highlight trade-offs between MDP rewards and receiver accuracy in experiments using Markov Coding Games.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in lossy compression and related fields because it introduces a novel framework that handles scenarios where the reconstructed distribution diverges from the source. This is relevant for applications like joint compression and retrieval. The greedy algorithm for EBIM offers a practical solution, while the theoretical analysis provides deeper insights into the problem’s structure. The work also opens new avenues for applying the framework in various applications, such as Markov coding games, showcasing its practical efficacy.

Visual Insights#

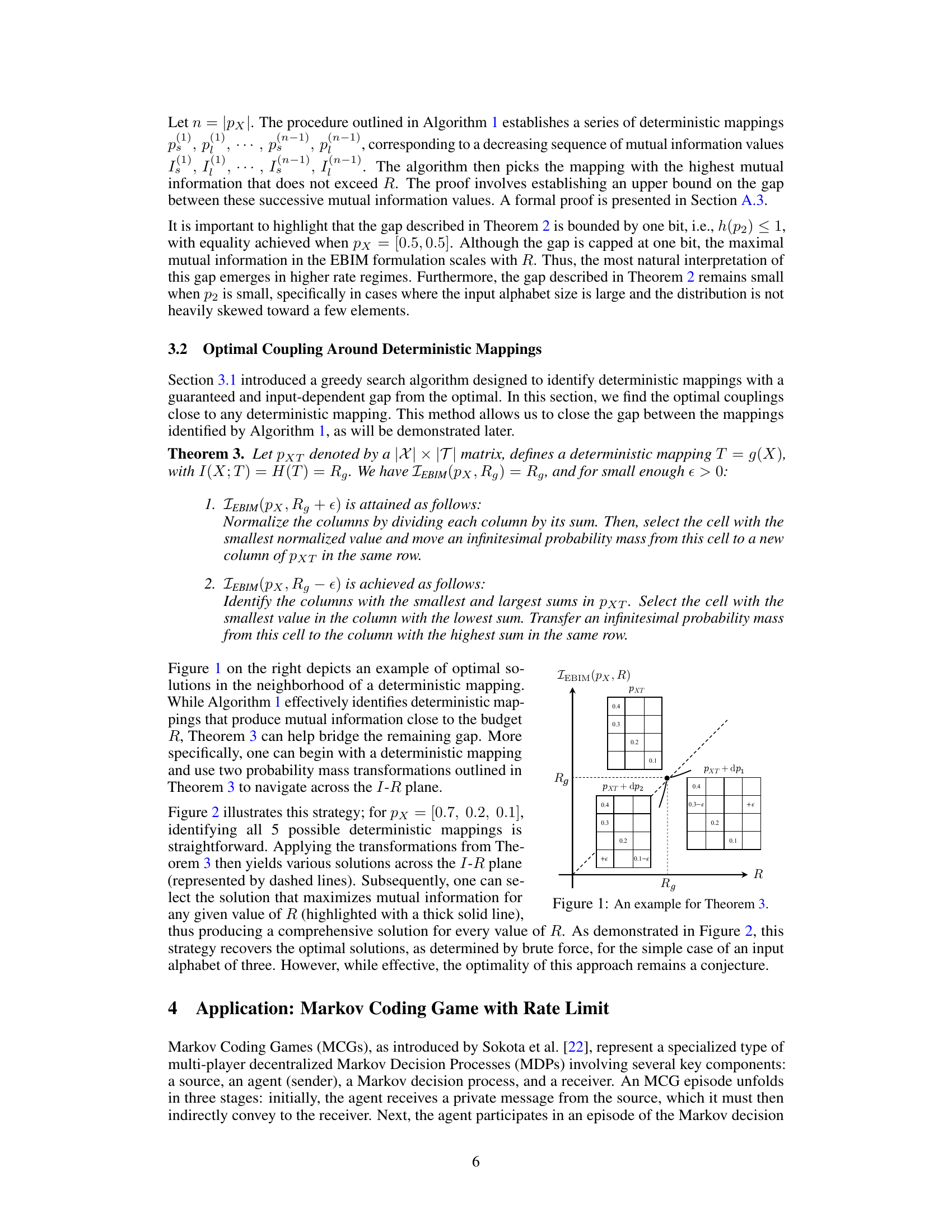

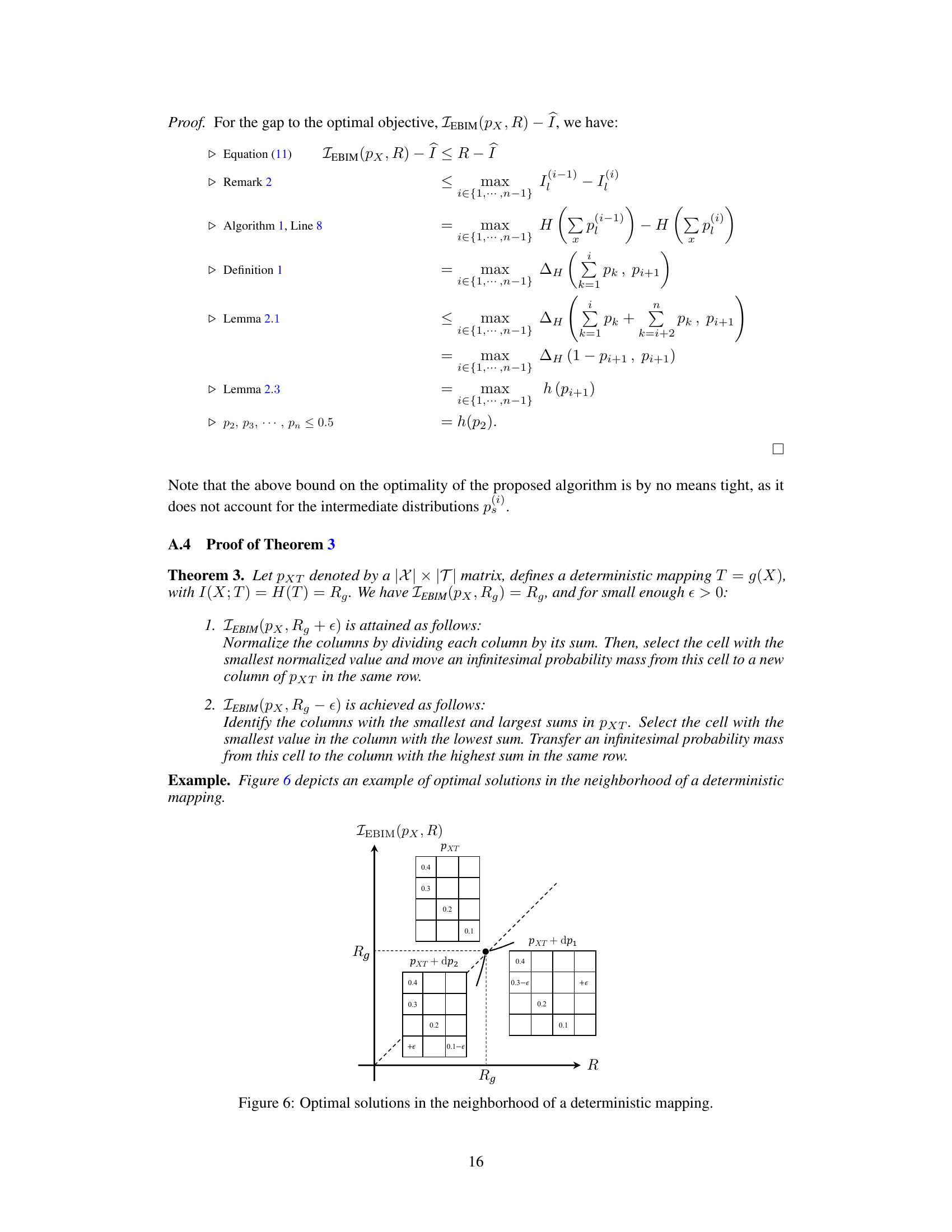

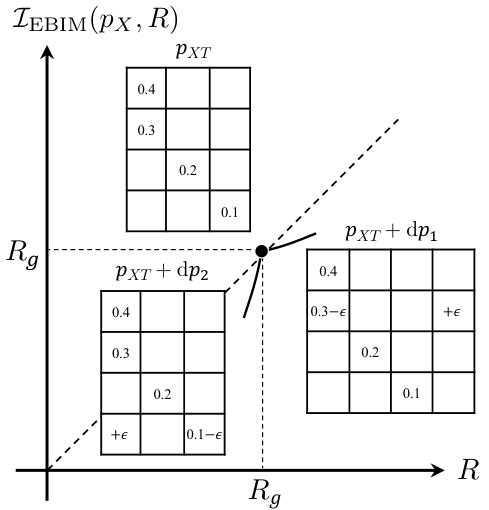

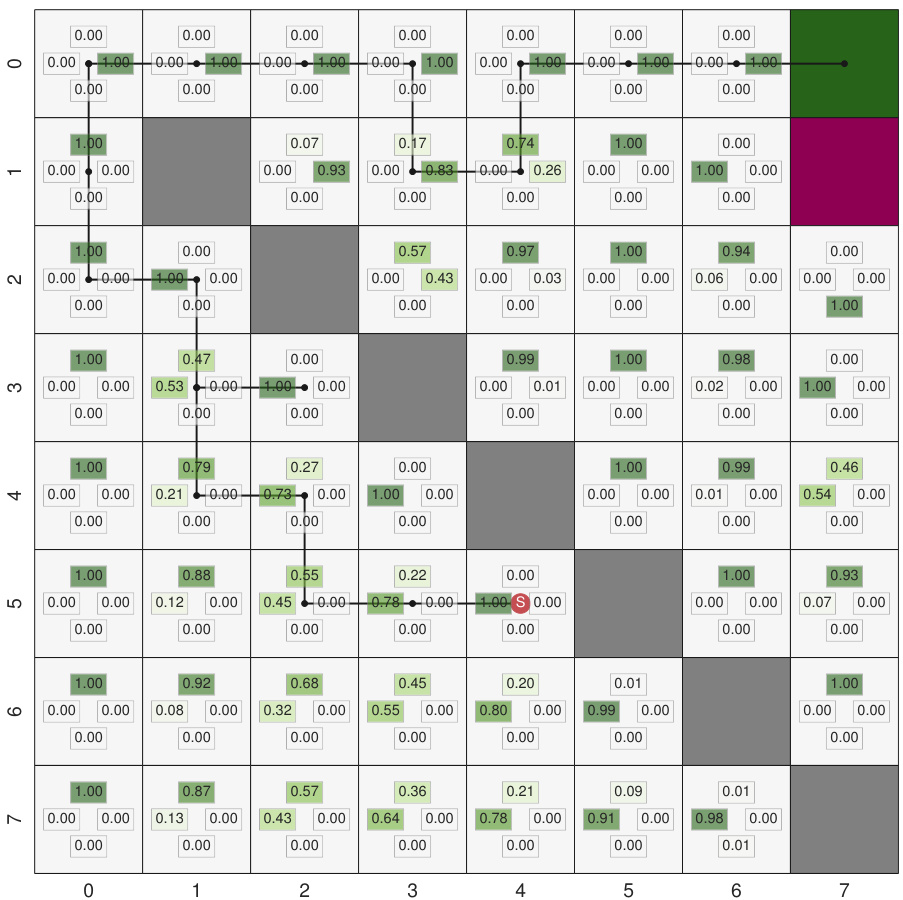

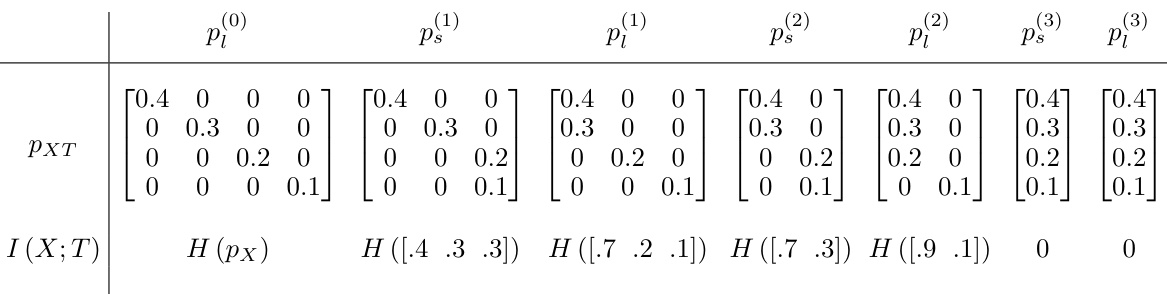

This figure illustrates Theorem 3, which describes how to find optimal couplings in the neighborhood of a deterministic mapping. Specifically, it shows how to find optimal solutions for entropy values slightly above and below the entropy (Rg) of the deterministic mapping. It highlights that moving an infinitesimal probability mass from a cell with the smallest normalized value to a new column in the same row (for slightly higher entropy) or from the smallest value cell of the lowest sum column to the highest sum column (for slightly lower entropy) will find the optimal coupling.

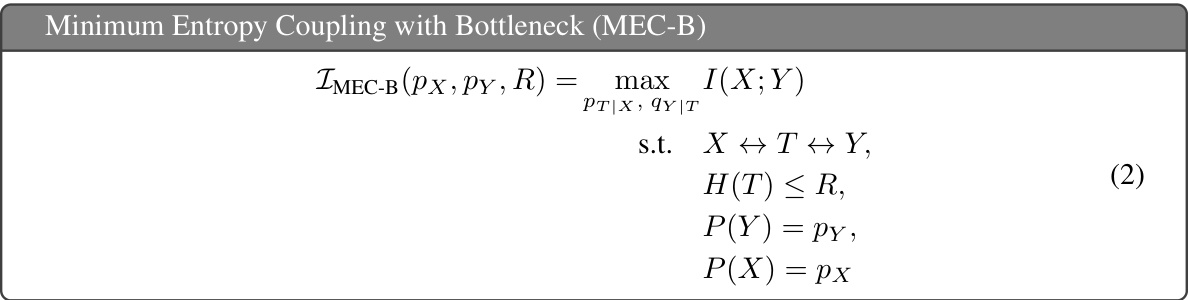

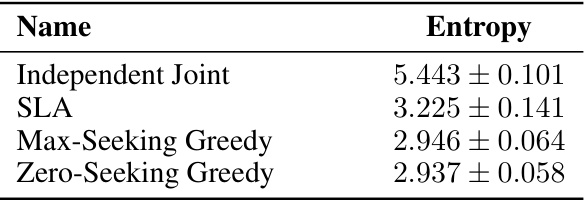

This table presents the results of 100 simulations comparing three different methods for computing the minimum entropy coupling: Independent Joint (a naive baseline that ignores the marginal constraints), Successive Linearization Algorithm (SLA) and two proposed greedy methods (Max-Seeking and Zero-Seeking). The results show that the proposed greedy algorithms significantly outperform SLA, achieving lower average entropy values.

In-depth insights#

Bottleneck Coupling#

Bottleneck coupling presents a novel approach to lossy compression by introducing a controlled level of stochasticity. This differs from traditional methods by allowing the reconstruction distribution to diverge from the source, offering advantages in scenarios with distributional shifts, like those found in joint compression and retrieval tasks. The core idea involves a bottleneck that limits the information flow, adding a degree of uncertainty or randomness to the compression process. This controlled stochasticity enables a trade-off between compression rate and reconstruction accuracy. The method extends the classical minimum entropy coupling framework by integrating this bottleneck constraint, leading to a more robust and flexible compression technique. The framework is further enhanced by decomposing the optimization problem into two distinct parts, allowing for separate optimization of the encoder and decoder. This decomposition simplifies the problem, leading to efficient algorithms with guaranteed performance. The application of this concept in Markov coding games illustrates the trade-offs between compression and other performance metrics. Overall, bottleneck coupling offers a powerful and versatile approach to lossy compression in a broader range of applications than traditional methods.

EBIM Algorithm#

The Entropy-Bounded Information Maximization (EBIM) algorithm, a core component of the Minimum Entropy Coupling with Bottleneck (MEC-B) framework, tackles the challenge of maximizing mutual information I(X;T) between input X and code T subject to an entropy constraint on T. Its significance lies in enabling controlled stochasticity in the encoding process, offering a crucial extension to classical minimum entropy coupling which lacks this feature. The paper proposes a greedy search algorithm for EBIM with a guaranteed performance bound, highlighting its practical applicability. This greedy algorithm intelligently navigates the space of deterministic mappings, aiming to achieve entropy close to the constraint while maximizing mutual information. Furthermore, the algorithm’s efficiency is a key advantage, scaling with O(n log n) complexity, making it suitable for practical implementation. Near-optimal solutions are further explored, demonstrating a strategy to bridge the gap between deterministic mappings and the true optimal solution in the EBIM problem. This comprehensive investigation of EBIM’s theoretical properties and practical algorithm enhances our understanding of lossy compression with distributional divergence and provides a powerful tool for applications requiring joint compression and retrieval.

Markov Game#

The concept of Markov Games, within the context of the research paper, appears to involve a multi-agent decision-making process under uncertainty. The agents interact strategically, their actions impacting both individual rewards and the overall system state, which evolves probabilistically according to Markov dynamics. The introduction of a communication bottleneck, limiting the information flow between agents, introduces a unique challenge, potentially necessitating sophisticated encoding and decoding strategies. The goal, likely, is to find optimal agent strategies that maximize cumulative rewards or other objectives, given the rate constraint on the communication channel. This makes the problem computationally complex, requiring careful consideration of both information theory and dynamic programming techniques. The paper’s results likely showcase the impact of this communication bottleneck on the achievable rewards and the equilibrium strategies, comparing against baselines to highlight the efficacy of the proposed methods. The problem’s connection to game theory is significant, as it’s not merely a sequence of individual optimization problems but a strategic interaction between agents who must anticipate the actions of others.

Rate-Distortion#

Rate-distortion theory is a cornerstone of data compression, quantifying the fundamental trade-off between the rate (amount of data used for compression) and the distortion (loss of information during compression). A lower rate implies more aggressive compression, leading to higher distortion, while a higher rate permits a more faithful reconstruction, resulting in lower distortion. The optimal rate-distortion function describes the minimum distortion achievable for a given rate, offering a theoretical limit for lossy compression techniques. Practical coding schemes aim to approach this limit, but often fall short due to computational complexity or other constraints. The choice of distortion measure significantly impacts the shape of the rate-distortion function, as different measures prioritize different types of errors. For example, logarithmic loss is common in machine learning applications due to its analytical properties, whereas mean squared error (MSE) is commonly used in image and audio processing. Advances in rate-distortion theory have led to the development of sophisticated compression algorithms that better approximate the optimal performance for various data types and applications. Further research continues to explore tighter bounds and more efficient algorithms for specific distortion metrics and data characteristics.

Future Research#

The paper’s conclusion suggests several promising avenues for future research. Quantifying the gap between separately optimizing the encoder and decoder versus a joint optimization of the Minimum Entropy Coupling with Bottleneck (MEC-B) framework is crucial for understanding its true efficiency. Exploring methods for fine-grained entropy control within the coupling could significantly enhance the framework’s flexibility and performance in various applications. The applicability of the Entropy-Bounded Information Maximization (EBIM) framework to continuous variables and its integration into neural network architectures for tasks like unpaired image translation and joint compression-upscaling require further investigation. Finally, examining the broader impacts and potential challenges related to fairness, privacy, and security concerns when applying this approach to real-world applications merits careful consideration.

More visual insights#

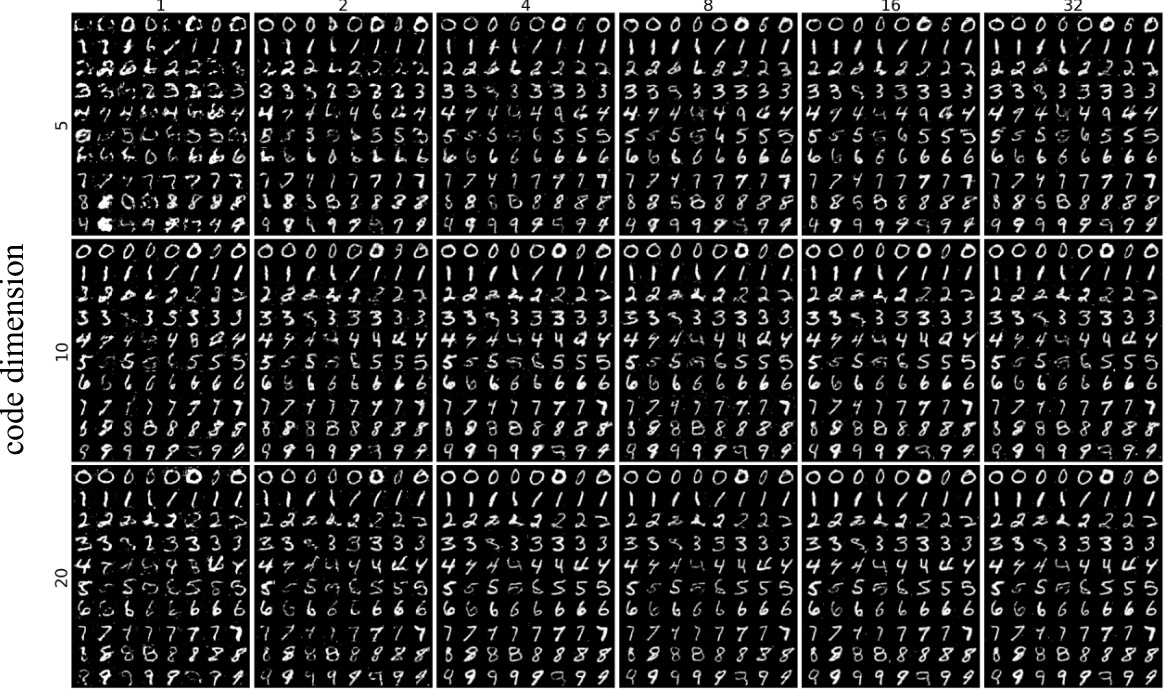

More on figures

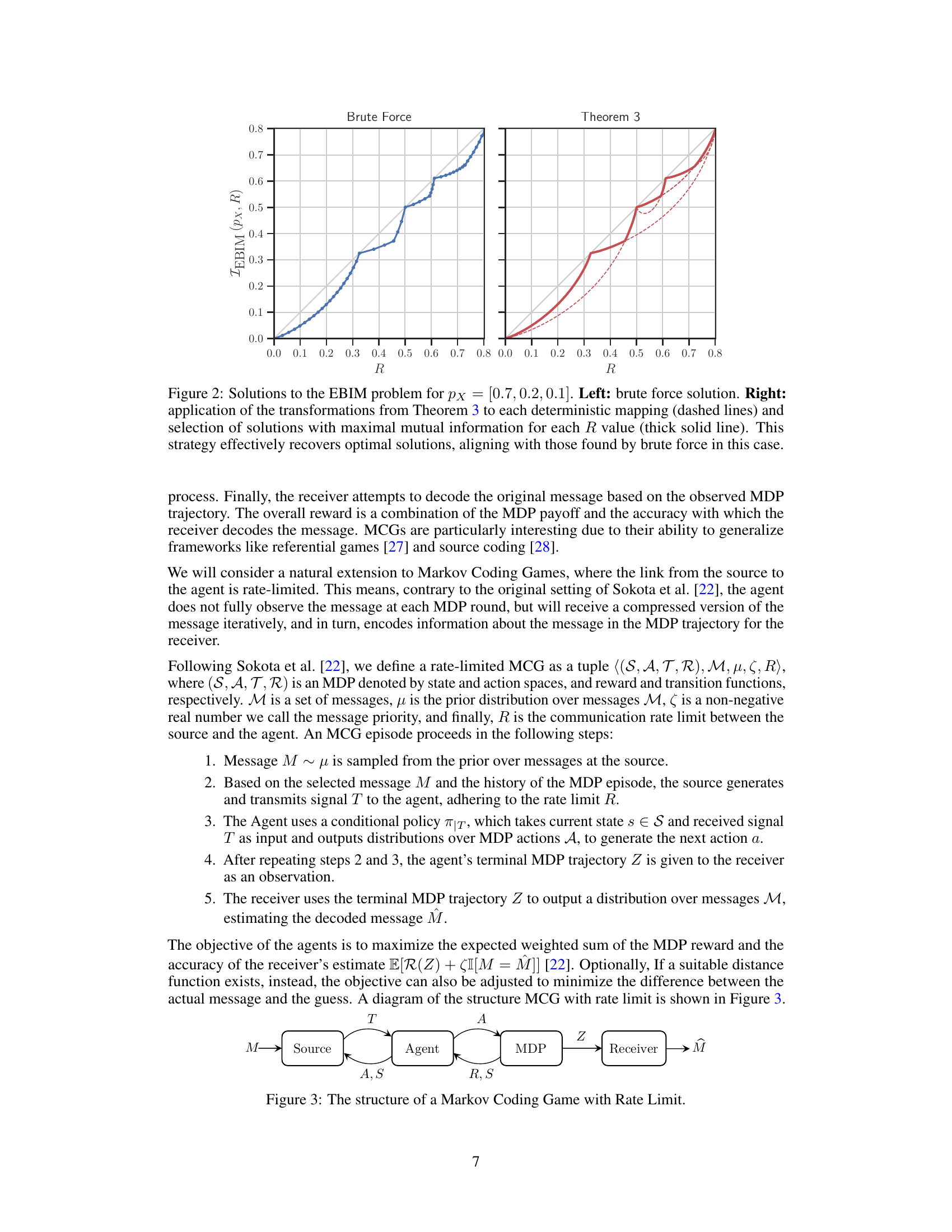

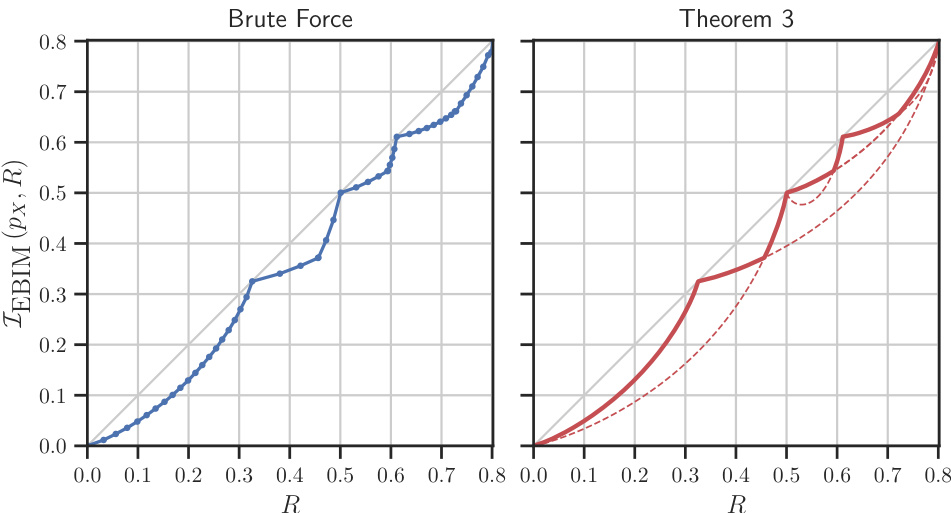

This figure compares two approaches for solving the Entropy-Bounded Information Maximization (EBIM) problem for a specific probability distribution (px = [0.7, 0.2, 0.1]). The left panel shows the optimal solutions obtained via an exhaustive brute-force search. The right panel demonstrates an alternative method based on Theorem 3, where the solutions are obtained by starting with a deterministic mapping and then applying transformations to close the gap to the optimal solution. The figure highlights that the method based on Theorem 3 effectively recovers the optimal solutions obtained by brute force, illustrating the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

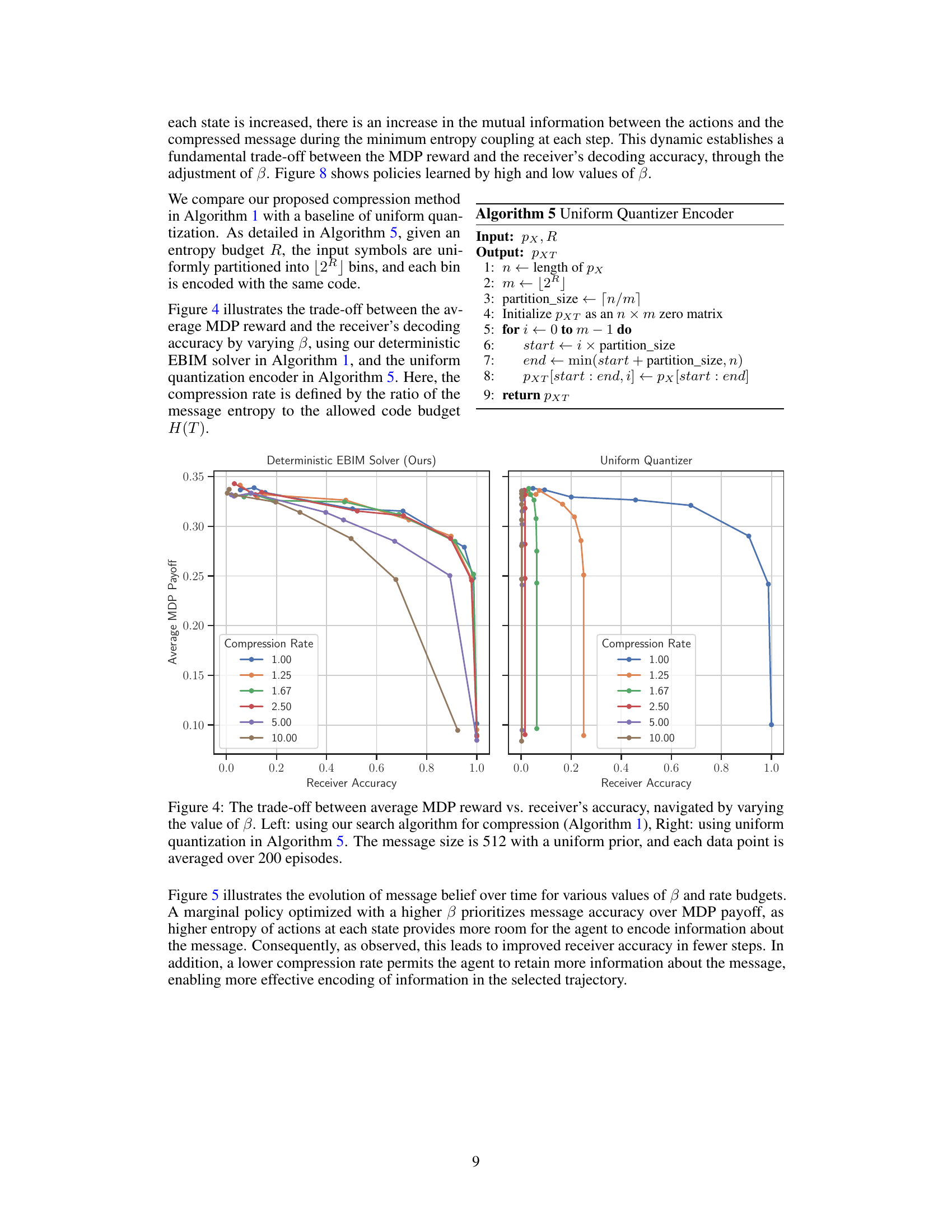

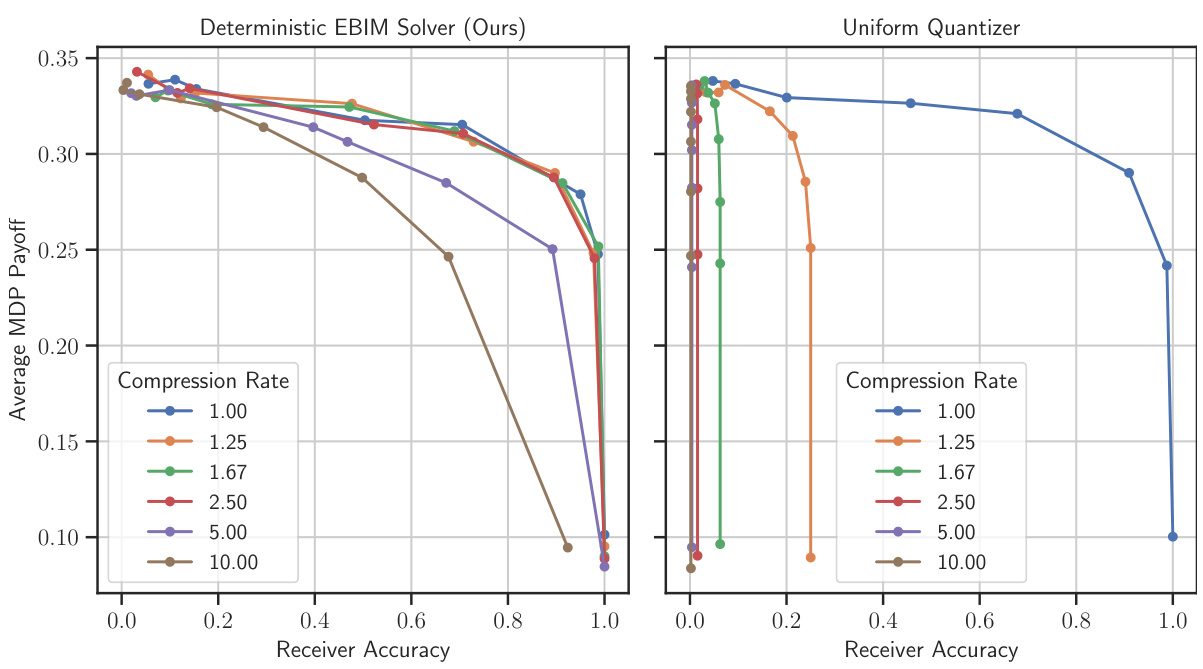

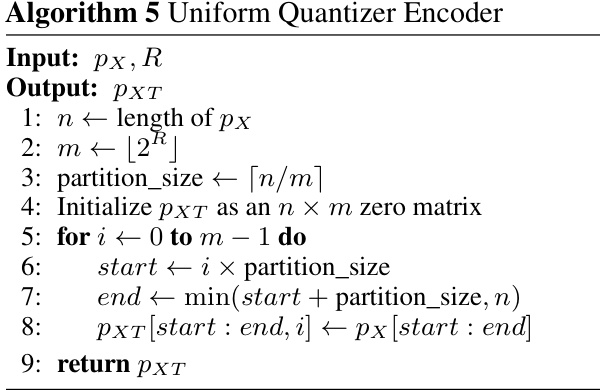

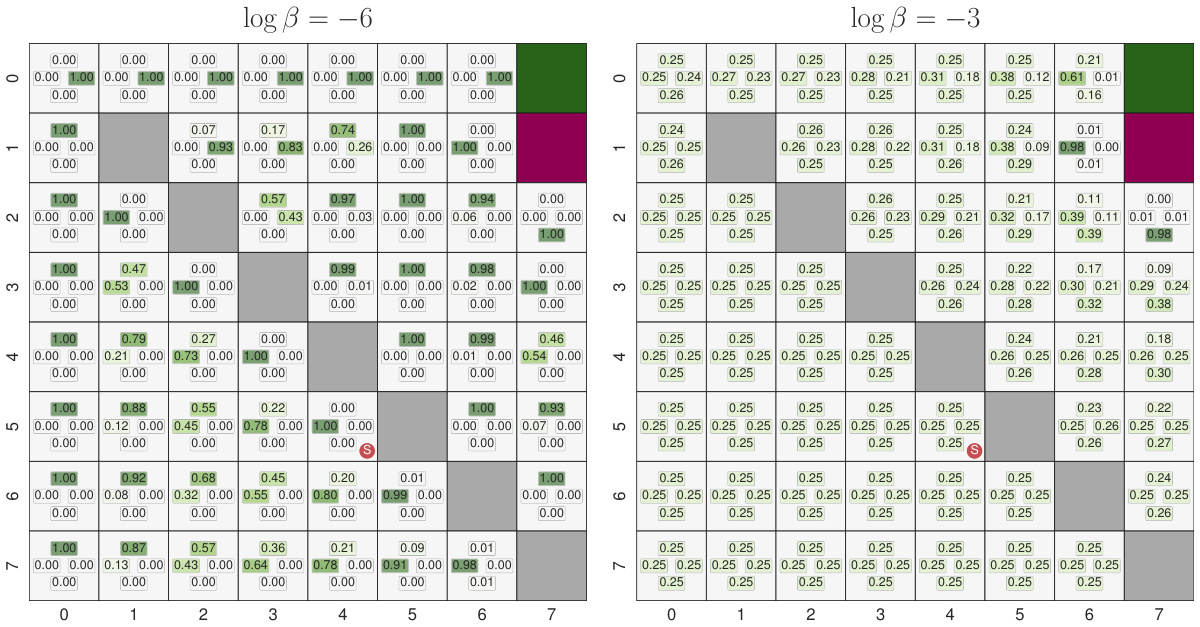

This figure shows the trade-off between the average MDP reward and the receiver’s decoding accuracy by varying the parameter β using two different compression methods: the proposed deterministic EBIM solver and a uniform quantizer. The left panel displays results from the deterministic EBIM solver (Algorithm 1), while the right panel shows results from the uniform quantizer (Algorithm 5). Each data point represents the average over 200 episodes, with message size of 512 and a uniform prior.

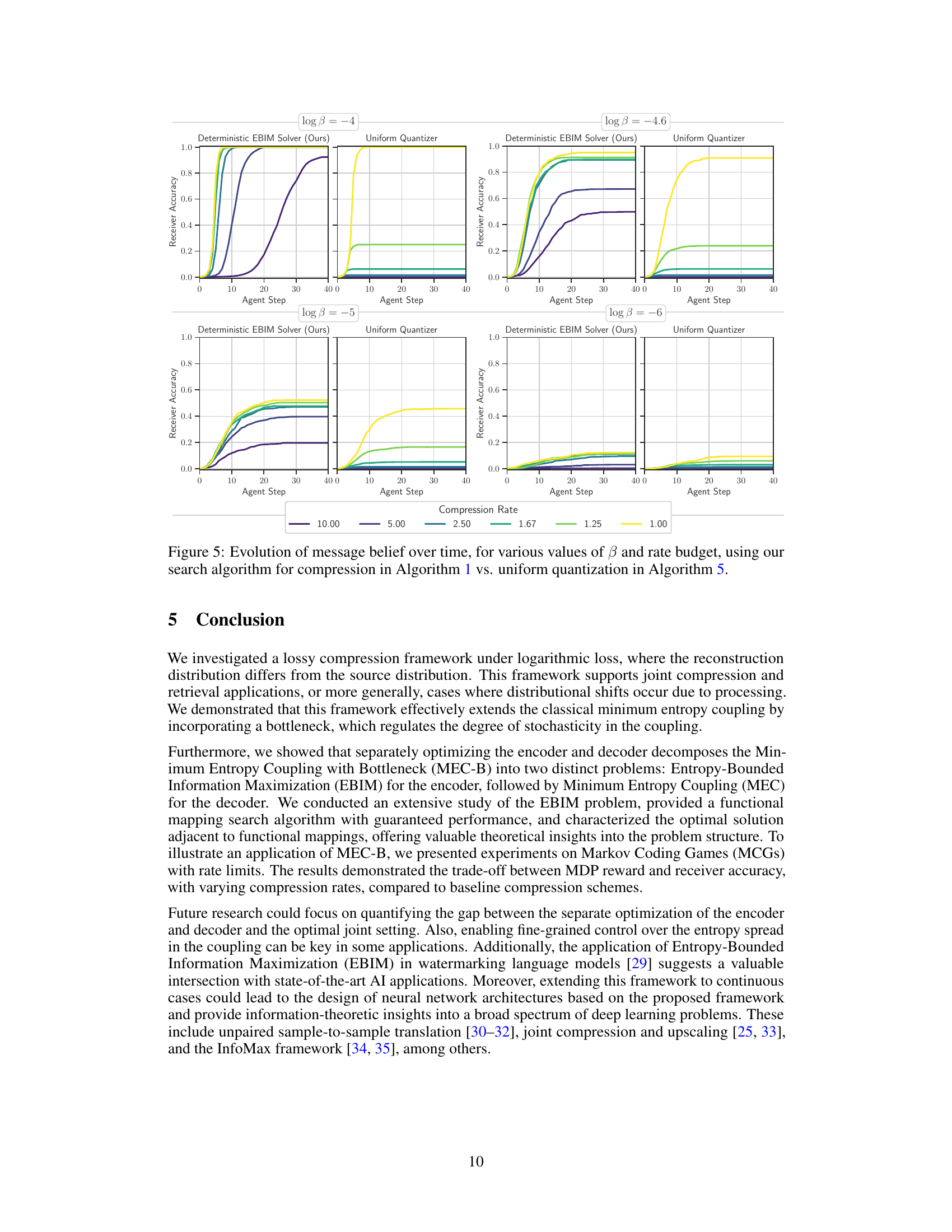

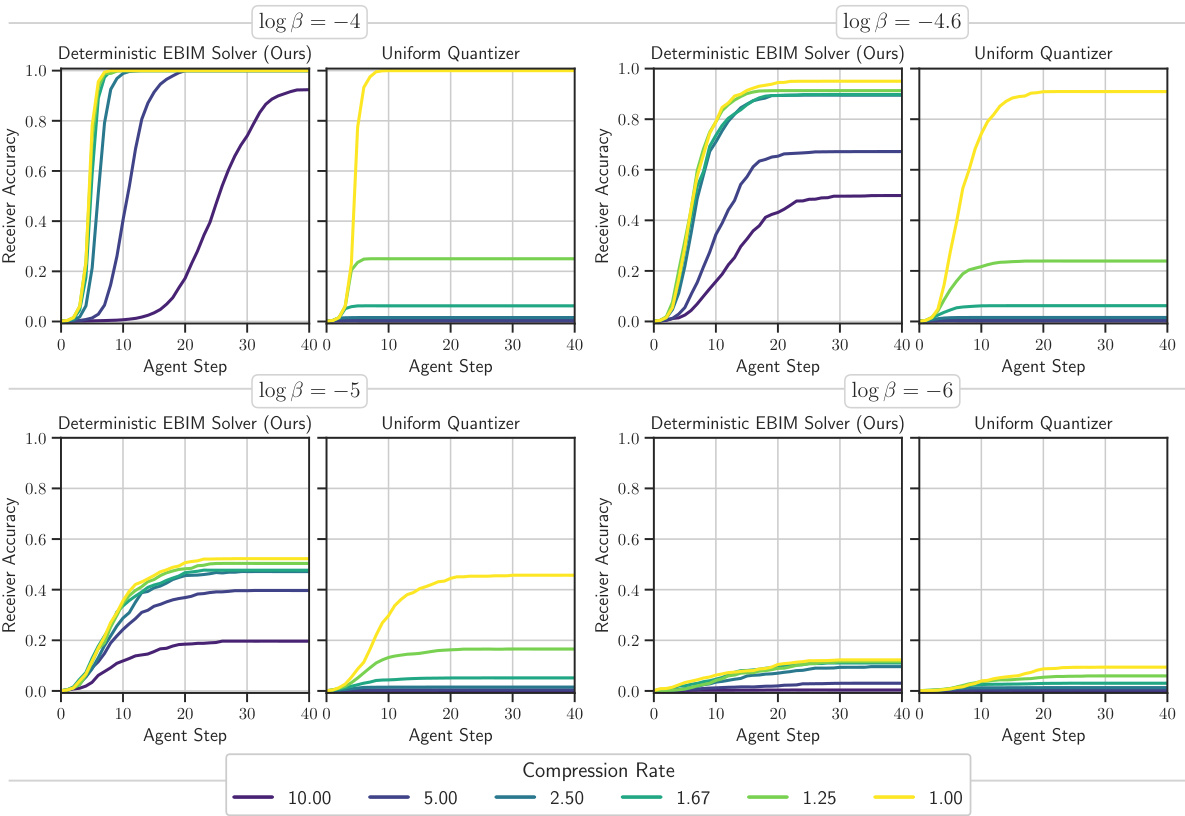

This figure shows how the receiver’s belief about the message evolves over time for different compression rates and values of β (beta). β controls the stochasticity of the agent’s actions in the Markov Decision Process (MDP). The plots compare the performance of the proposed deterministic EBIM solver (Algorithm 1) with a baseline uniform quantizer (Algorithm 5). Different colors represent various compression rates, demonstrating the trade-off between compression efficiency and the speed of convergence to the correct message.

This figure illustrates Theorem 3, which describes how to find optimal couplings close to any deterministic mapping. It shows how to find the optimal couplings in the neighborhood of a deterministic mapping by moving infinitesimal probability mass from one cell to another. The figure visualizes the changes in mutual information (I(X;T)) and entropy (H(T)) as a result of these small probability mass changes. The lines show different solutions which maximize mutual information for a given entropy value.

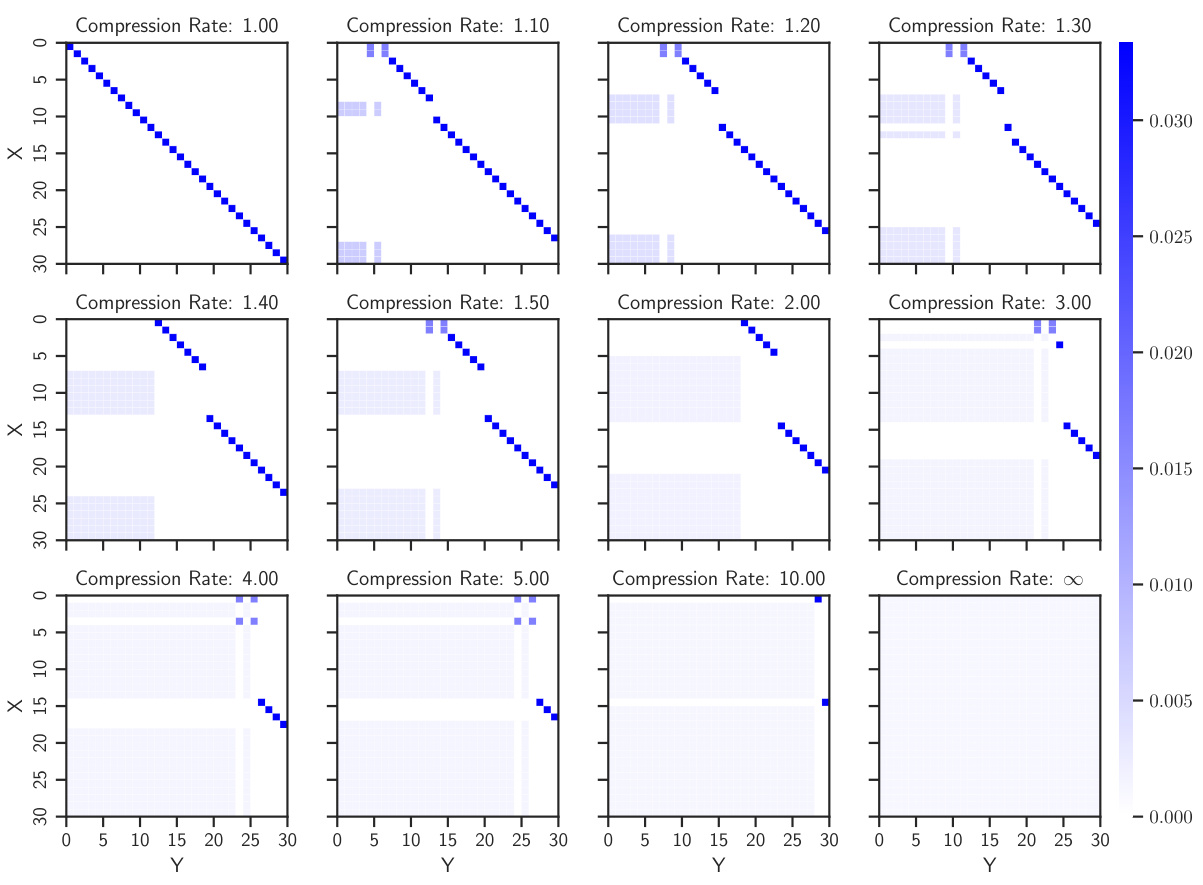

This figure shows the generated couplings for different compression rates in the MEC-B framework using uniform input and output distributions. The compression rate is defined as the ratio of the input entropy to the allowed code budget. As the compression rate increases (meaning less information is allowed to be transmitted), the couplings become more stochastic and their entropy increases.

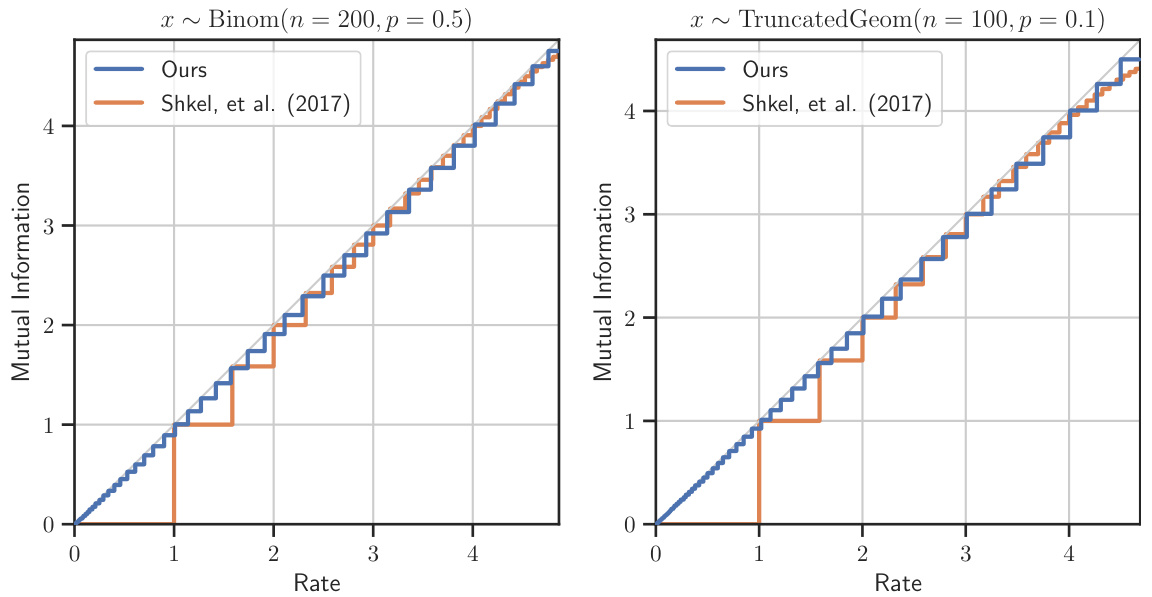

This figure compares the mutual information achieved by the proposed deterministic EBIM solver and the method from Shkel et al. (2017) for two different input distributions: Binomial and Truncated Geometric. The x-axis represents the maximum allowed entropy H(T) (rate), and the y-axis represents the mutual information I(X;T) achieved. The plot shows that both methods perform similarly in the high-rate regime, but in the low-rate regime, the proposed method identifies more mappings and outperforms the Shkel et al. (2017) method.

This figure visualizes the couplings generated by the Minimum Entropy Coupling with Bottleneck (MEC-B) framework for different compression rates. The input and output distributions are uniform. Each subplot shows a coupling matrix at a specific compression rate (H(X)/R). As the compression rate increases (meaning the code budget R decreases relative to the input entropy H(X)), the couplings transition from deterministic (mostly diagonal) to increasingly stochastic (more spread out). The color intensity represents the coupling probability. Darker blue indicates higher probability.

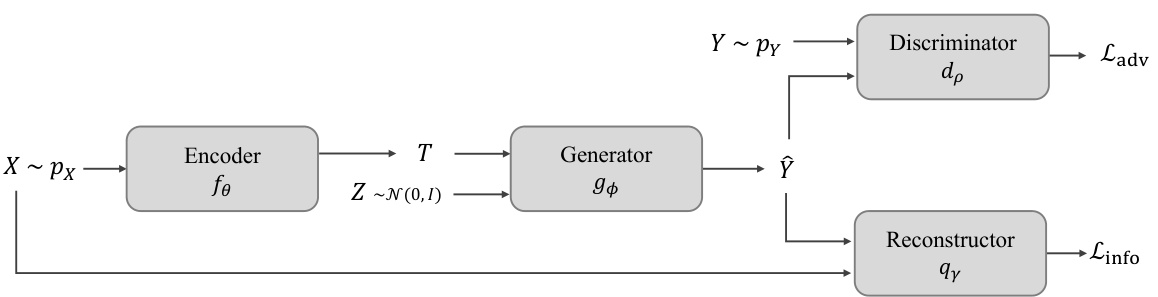

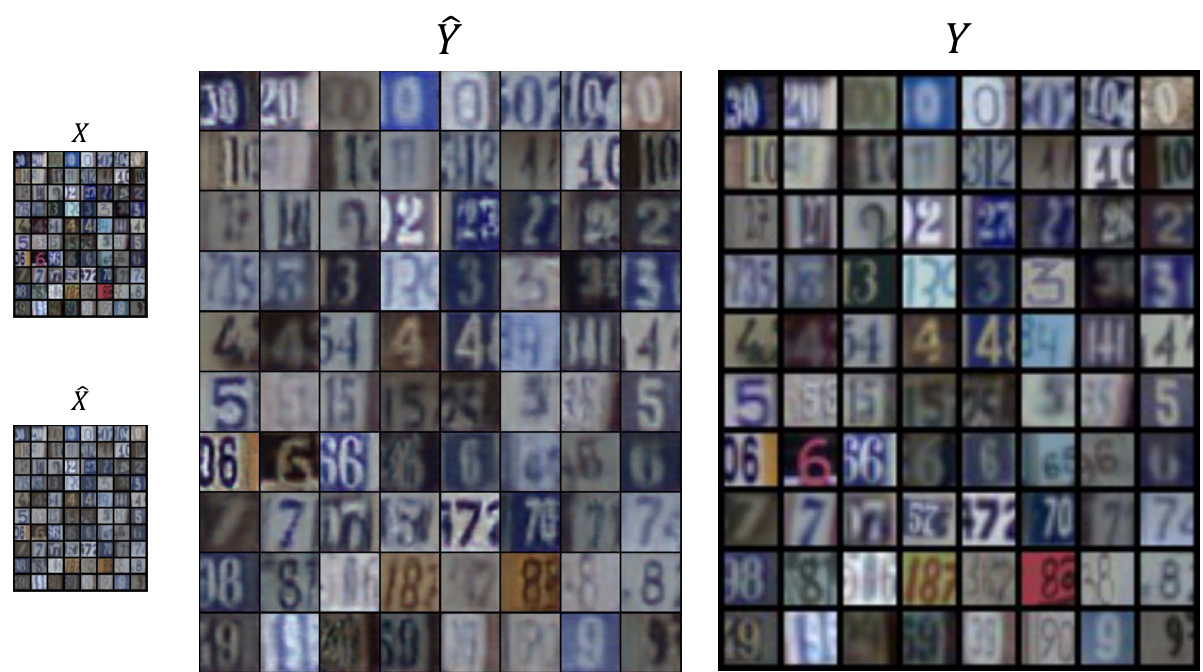

This figure shows a block diagram of the unsupervised image restoration framework proposed in the paper. The framework consists of an encoder, generator, reconstructor, and discriminator. The encoder takes a low-resolution image X as input and outputs a compressed representation T. The generator takes T and a noise vector Z as input and outputs a high-resolution image Y. The reconstructor takes Y as input and outputs a reconstructed low-resolution image X’. The discriminator takes Y and X’ as input and outputs an adversarial loss Ladv. The total loss is the sum of the adversarial loss and an information loss Linfo, which encourages the generated image Y to be similar to the original image X.

This figure visualizes the couplings generated using the Minimum Entropy Coupling with Bottleneck (MEC-B) framework. It shows how the joint distribution between the input (X) and output (Y) changes as the compression rate varies. The compression rate is the ratio of the input entropy to the allowed code budget, H(X)/R. Higher compression rates mean less information is preserved. As the compression rate increases (moving from left to right and top to bottom), the coupling becomes more stochastic, as evidenced by increased entropy and less deterministic mappings between X and Y. This illustrates the trade-off between compression and the resulting entropy.

This figure shows example inputs (low-resolution images) and their corresponding outputs (high-resolution images upscaled by a factor of 4) from the Street View House Numbers (SVHN) dataset. The figure illustrates the performance of the unsupervised image restoration framework proposed in the paper. Note that some color discrepancies may be observed between original and upscaled images, as pointed out in the paper, reflecting the invariance of mutual information to invertible transformations (e.g., color permutations).

More on tables

This table compares the average achieved joint entropy from 100 simulations of different methods for solving the minimum entropy coupling problem. The methods compared are: independently generated joint distributions, Successive Linearization Algorithm (SLA), a max-seeking greedy algorithm, and a zero-seeking greedy algorithm. The results show that the greedy algorithms achieve significantly lower joint entropy than the other methods.

This table compares the average joint entropy achieved by three different methods for minimum entropy coupling: Independent Joint, Successive Linearization Algorithm (SLA), Max-Seeking Greedy, and Zero-Seeking Greedy. The results are based on 100 simulations, with each simulation using randomly generated marginal distributions. The table demonstrates the performance difference between the methods, highlighting the effectiveness of the greedy algorithms in finding near-optimal solutions.

This table compares the average joint entropy achieved by three different methods for minimum entropy coupling: Independent Joint, Successive Linearization Algorithm (SLA), Max-Seeking Greedy, and Zero-Seeking Greedy. The results are based on 100 simulations with various marginal distributions, and show that the greedy algorithms significantly outperform the SLA and Independent Joint methods.

This table presents a comparison of the average achieved joint entropy for three different methods used to solve the Minimum Entropy Coupling problem. The methods compared are Independent Joint, Successive Linearization Algorithm (SLA), Max-Seeking Greedy, and Zero-Seeking Greedy. For each method, the average joint entropy and its standard deviation across 100 simulations are reported. The results show that the greedy methods (Max-Seeking and Zero-Seeking) achieve significantly lower joint entropy compared to the other methods.

This table compares the average achieved joint entropy from three different methods for calculating the minimum entropy coupling given 100 simulations of marginal distributions. The methods compared are: calculating the joint entropy independently, using successive linearization algorithm (SLA), and using two greedy algorithms (max-seeking and zero-seeking greedy). The results show that the two greedy algorithms achieve significantly lower average joint entropy than the other methods, demonstrating their efficiency for approximating minimum entropy coupling.

This table presents a comparison of the average joint entropy achieved by three different methods for minimum entropy coupling across 100 simulations. The methods compared are Independent Joint (a baseline where the joint distribution is simply the product of the marginals), Successive Linearization Algorithm (SLA), Max-Seeking Greedy, and Zero-Seeking Greedy. The Max-Seeking and Zero-Seeking Greedy methods are the two approximate greedy algorithms proposed in the paper. The table shows that the proposed greedy algorithms achieve significantly lower joint entropy compared to the baseline and SLA.

This table presents a comparison of the average achieved joint entropy for three different methods used to solve the minimum entropy coupling problem. The methods compared are: Independent Joint (a baseline where marginals are independent), Successive Linearization Algorithm (SLA) (a general concave minimization method), Max-Seeking Greedy, and Zero-Seeking Greedy (two new proposed linear-time approximate greedy algorithms). The results show that the new proposed greedy algorithms significantly outperform the other methods, achieving substantially lower average joint entropy.

This table presents the average achieved joint entropy from 100 simulations using three different methods: Independent Joint distribution, Successive Linearization Algorithm (SLA), Max-Seeking Greedy, and Zero-Seeking Greedy. The table compares the performance of these algorithms in finding a joint distribution with minimal entropy given the marginal distributions. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the greedy algorithms (Max-Seeking and Zero-Seeking) compared to a standard method (SLA) and a naive approach (Independent Joint).

This table presents the average achieved joint entropy from 100 simulations of marginal distributions using four different methods: Independent Joint, SLA, Max-Seeking Greedy, and Zero-Seeking Greedy. The results show that the greedy methods (Max-Seeking and Zero-Seeking) significantly outperform the other two, achieving lower joint entropies.

This table compares the average achieved joint entropy from 100 simulations using three different methods for calculating minimum entropy coupling: Independent Joint, Successive Linearization Algorithm (SLA), Max-Seeking Greedy, and Zero-Seeking Greedy. The results show that the greedy algorithms achieve significantly lower entropy than the independent joint distribution and SLA.

This table presents the average joint entropy achieved by three different methods for computing minimum entropy coupling across 100 simulations. The methods compared are: Independent Joint (a baseline where the joint distribution is simply the product of the marginals); Successive Linearization Algorithm (SLA), a general concave minimization method; Max-Seeking Greedy and Zero-Seeking Greedy, the two greedy algorithms proposed in the paper. The results demonstrate that the greedy algorithms significantly outperform the other methods in terms of minimizing entropy.

Full paper#