↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Training large language models (LLMs) is computationally expensive and time-consuming. Existing online data selection methods for LLMs are either inefficient or rely on simplistic heuristics that don’t effectively capture data informativeness. This paper addresses these limitations.

The paper proposes GREedy Approximation Taylor Selection (GREATS), a novel online data selection method using a greedy algorithm to optimize batch quality, approximated through Taylor expansion. GREATS leverages a ‘ghost inner-product’ technique for efficient computation. Experiments show GREATS significantly improves training speed and model performance compared to other methods and is computationally comparable to regular training.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel and efficient online batch selection method (GREATS) for training large language models. This addresses a critical challenge in LLM training—the vast amounts of time and resources required—by intelligently selecting high-value training data at each iteration. The method is computationally efficient, scalable, and demonstrates significant improvements in convergence speed and generalization performance. It opens avenues for optimizing LLM training, resource management, and improving model quality.

Visual Insights#

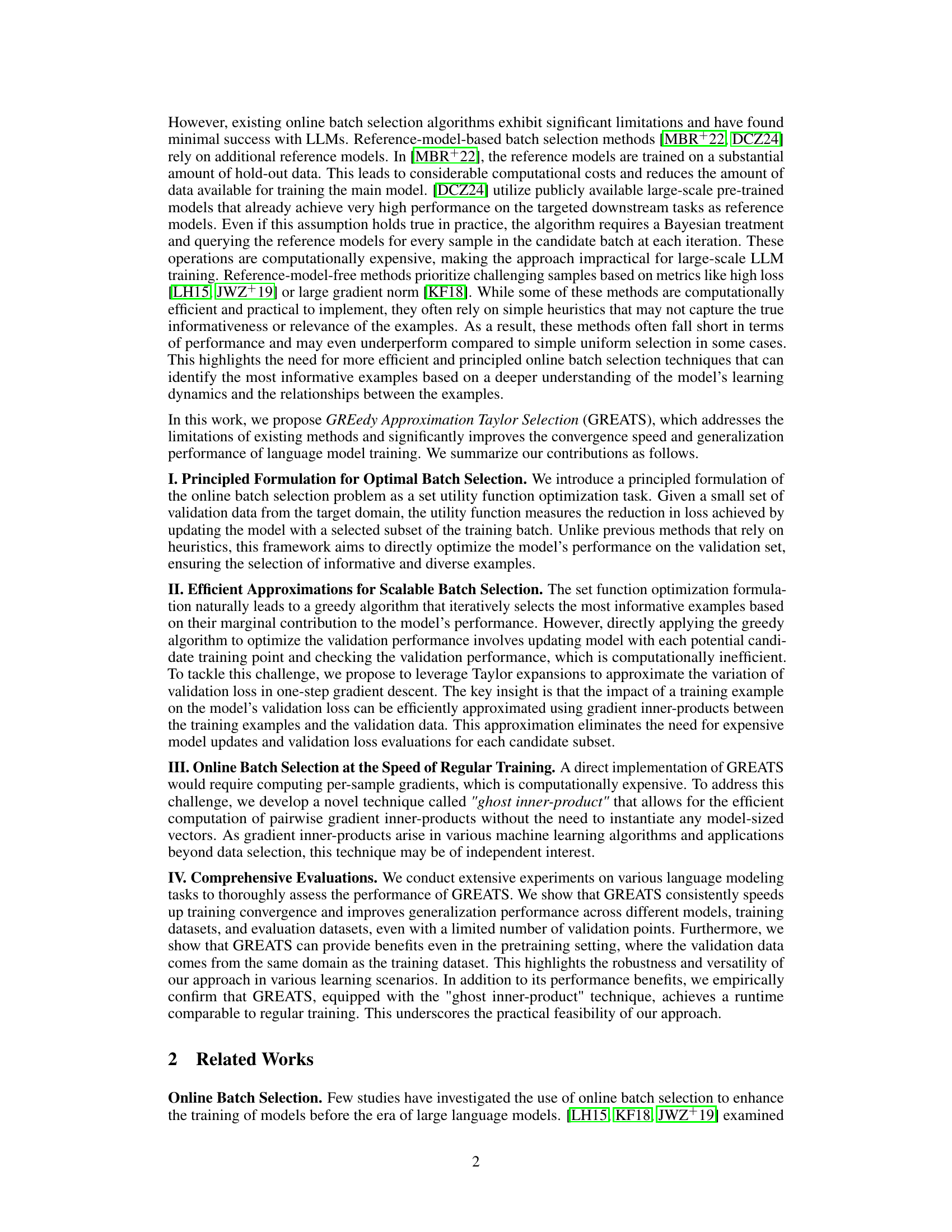

This figure shows the correlation between the actual and predicted validation loss changes. Panel (a) uses only the first-order Taylor expansion, while panel (b) includes both the first-order and Hessian interaction terms. The higher correlation in (b) demonstrates the improved accuracy of the approximation when considering the Hessian interaction.

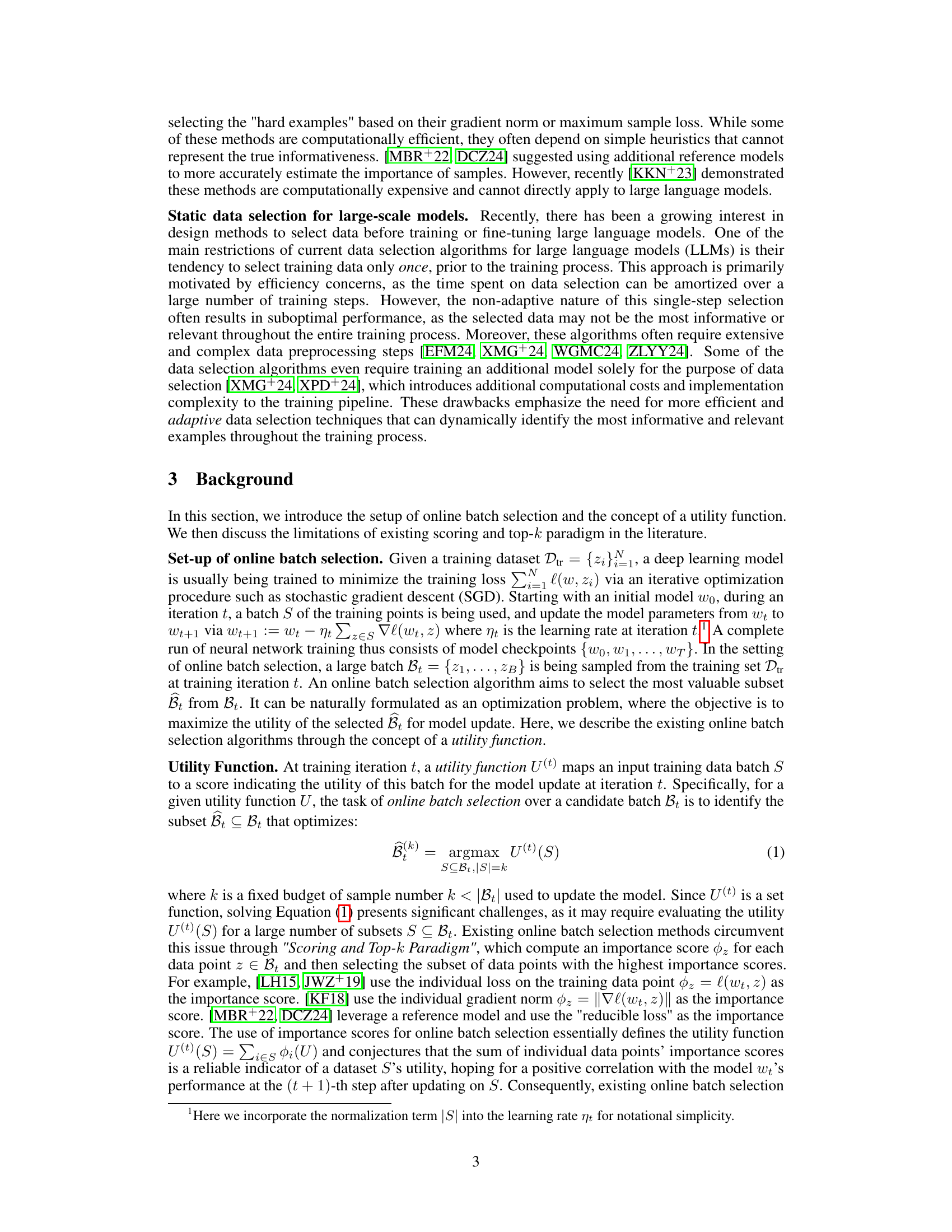

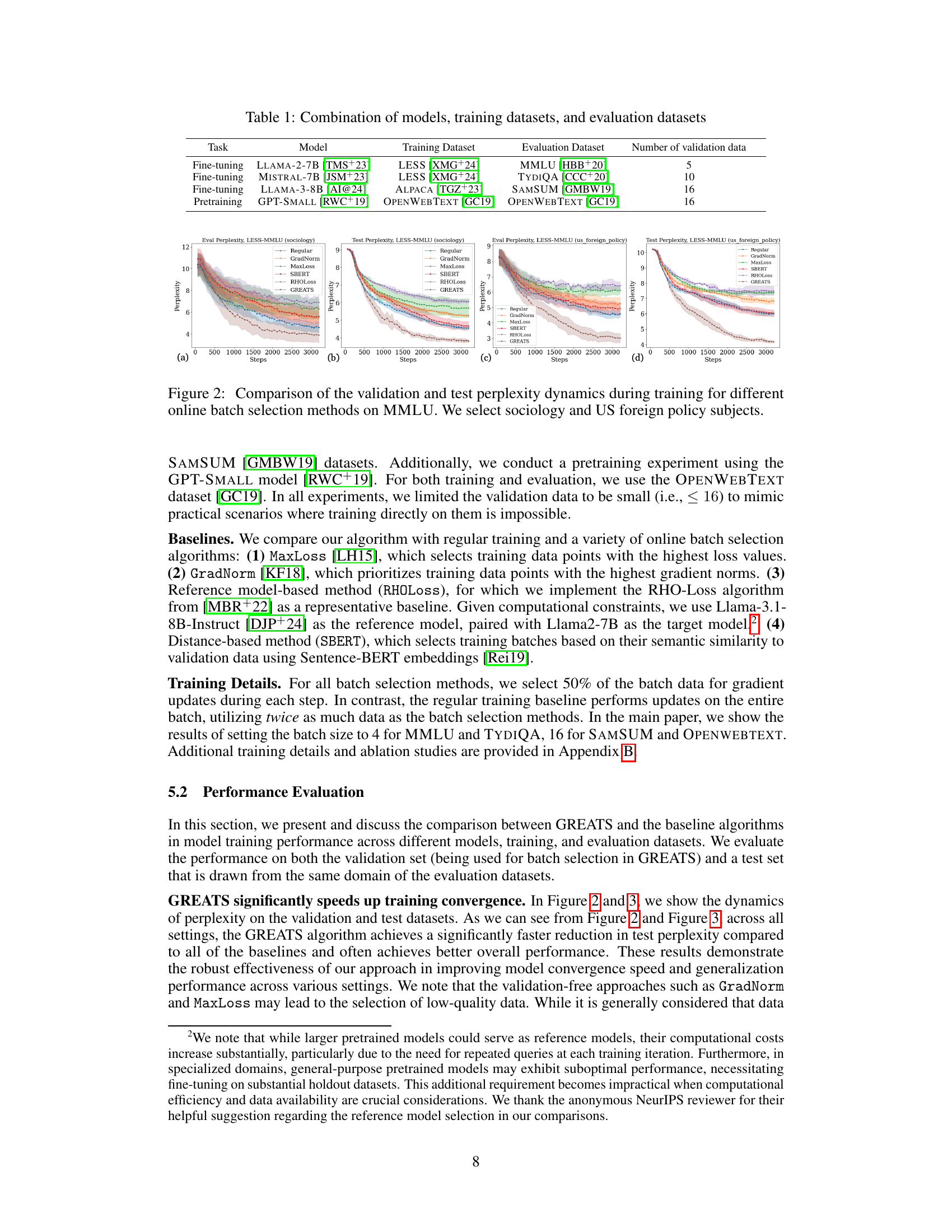

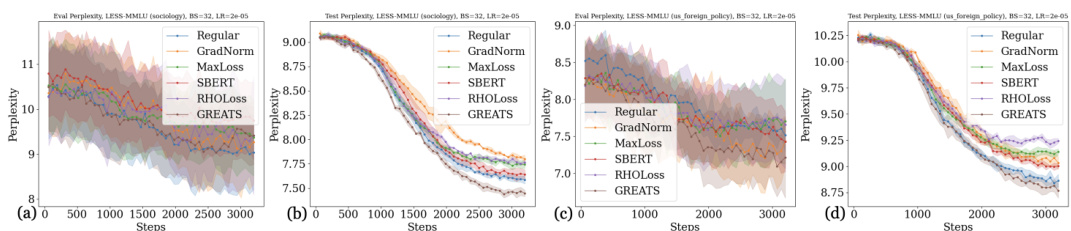

This table shows the different model-training-evaluation dataset combinations used in the experiments of the paper. It lists the language models used (MISTRAL-7B, LLAMA-2-7B, LLAMA-3-8B, and GPT-SMALL), the training datasets used for fine-tuning (LESS and ALPACA) and pretraining (OPEN WEBTEXT), and the evaluation datasets (MMLU, TYDIQA, and SAMSUM). The number of validation data points used is also specified for each combination.

In-depth insights#

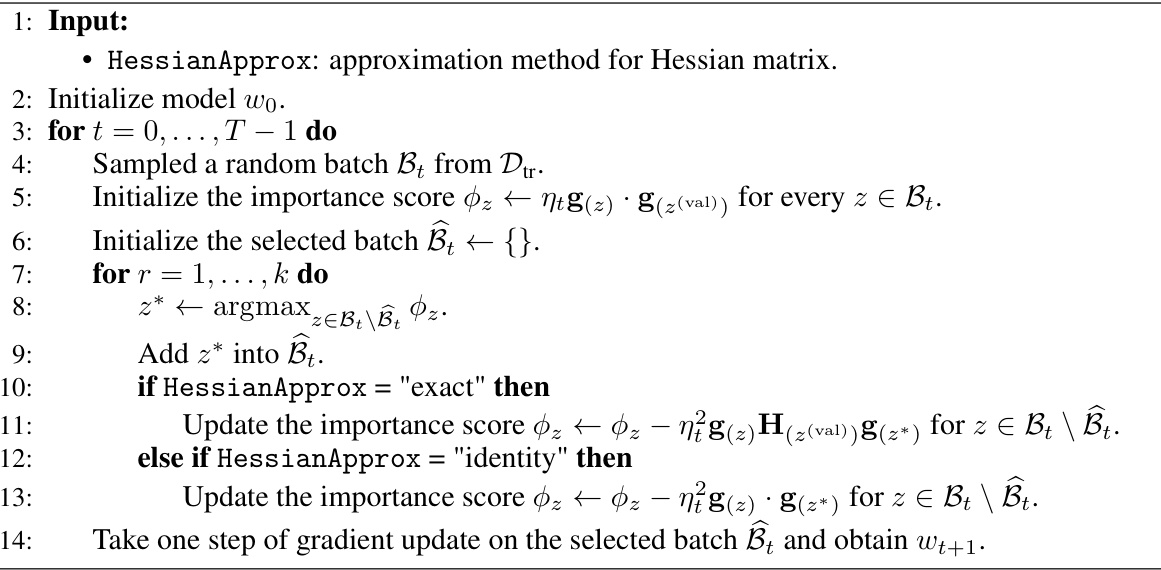

GREATS Algorithm#

The GREATS algorithm presents a novel approach to online data selection for large language model (LLM) training. Its core innovation lies in using a greedy approach combined with Taylor expansion to efficiently approximate the utility of adding a data point to a training batch, thus avoiding computationally expensive reference models or heuristic methods. This approximation, further enhanced by a novel “ghost inner-product” technique, enables GREATS to achieve the speed of regular training while improving convergence speed and generalization performance. GREATS’ principled formulation, focusing on validation loss reduction, and its scalability are key strengths. However, the algorithm’s reliance on a limited number of validation points and the potential limitations of Taylor approximation warrant further investigation. The use of SGD, rather than Adam, is another aspect that requires consideration for wider applicability. Despite these limitations, GREATS’ efficiency and performance gains demonstrated in experiments suggest that it offers a significant advancement in online data selection for LLMs.

Taylor Approximation#

The core idea revolves around approximating a complex function, the validation loss, using a Taylor expansion. This simplifies the calculation of how adding a data point to a batch affects the validation loss without needing a full model update, a computationally expensive operation. The approximation leverages gradient inner products, providing a computationally efficient estimate of the impact of individual data points on the validation performance. This is crucial for scaling online batch selection to large language models (LLMs) which are notoriously resource-intensive to train. The accuracy of the Taylor approximation is validated empirically, demonstrating its efficacy despite being a lower-order approximation. The trade-off is between approximation accuracy and computational cost, but the results suggest that the improved efficiency outweighs the minor loss of accuracy, enabling significant speedups in LLM training.

Ghost Inner Product#

The concept of “Ghost Inner Product” presented in the paper is a computationally efficient technique for approximating gradient inner products without explicitly calculating the full gradient vectors. This approach is crucial for scaling online batch selection methods to large language models, which typically involve massive datasets and model sizes. The core idea lies in leveraging the chain rule of calculus and the structure of backpropagation to cleverly decompose the gradient computations, enabling efficient computation of pairwise inner products. The “ghost” aspect refers to avoiding the explicit formation of model-sized gradient vectors, instead using readily available gradients during backpropagation. This significantly reduces memory footprint and computational cost, making the overall algorithm more practical for real-world applications. The technique’s efficacy relies on the approximation of marginal gain achieved by including a training example in the update step. Although this approximation introduces some error, the paper demonstrates its effectiveness through experiments showing improved performance compared to alternative approaches. It is highly innovative and contributes significantly to the efficiency of LLM training by overcoming the computational bottleneck posed by traditional gradient computations in online batch selection scenarios. Its adaptability to various layer types and potential applicability beyond online batch selection, as suggested in the paper, further enhances its practical importance. The “ghost inner product” is a significant contribution to efficient deep learning, promising potential benefits for diverse machine learning tasks.

Experimental Results#

The section on Experimental Results should meticulously detail the methodology and findings. It needs to clearly present the models used, datasets employed (including their sizes and characteristics), and evaluation metrics. The choice of metrics is crucial and should be justified. Quantitative results should be reported with appropriate precision and error bars to indicate statistical significance, ideally using statistical tests. For reproducibility, it should describe the experimental setup, including hardware and software versions. Visualizations such as graphs and tables must be clear and well-labeled to quickly convey key trends. A comparison against baselines or state-of-the-art methods is essential. The discussion should go beyond simply presenting numbers; it should analyze the results, explaining unexpected findings and correlating them with the model’s behavior or design choices. Ablation studies investigating the impact of different components or hyperparameters are valuable for demonstrating the robustness and effectiveness of the proposed approach. Finally, this section should directly address the claims made in the introduction, showing how the experimental results support those claims.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section presents exciting avenues for extending GREATS. Addressing the reliance on validation data is paramount; a validation-free method would significantly enhance practicality. Exploring compatibility with optimizers beyond SGD, such as Adam, is crucial for broader applicability. Investigating the impact of varying batch sizes and learning rates on GREATS’ performance across diverse model architectures will provide a more complete picture of its robustness. Finally, deeper analysis of GREATS’ performance on downstream tasks, moving beyond perplexity to assess impact on specific applications, and a more thorough examination of potential biases and fairness implications in selected datasets are needed.

More visual insights#

More on figures

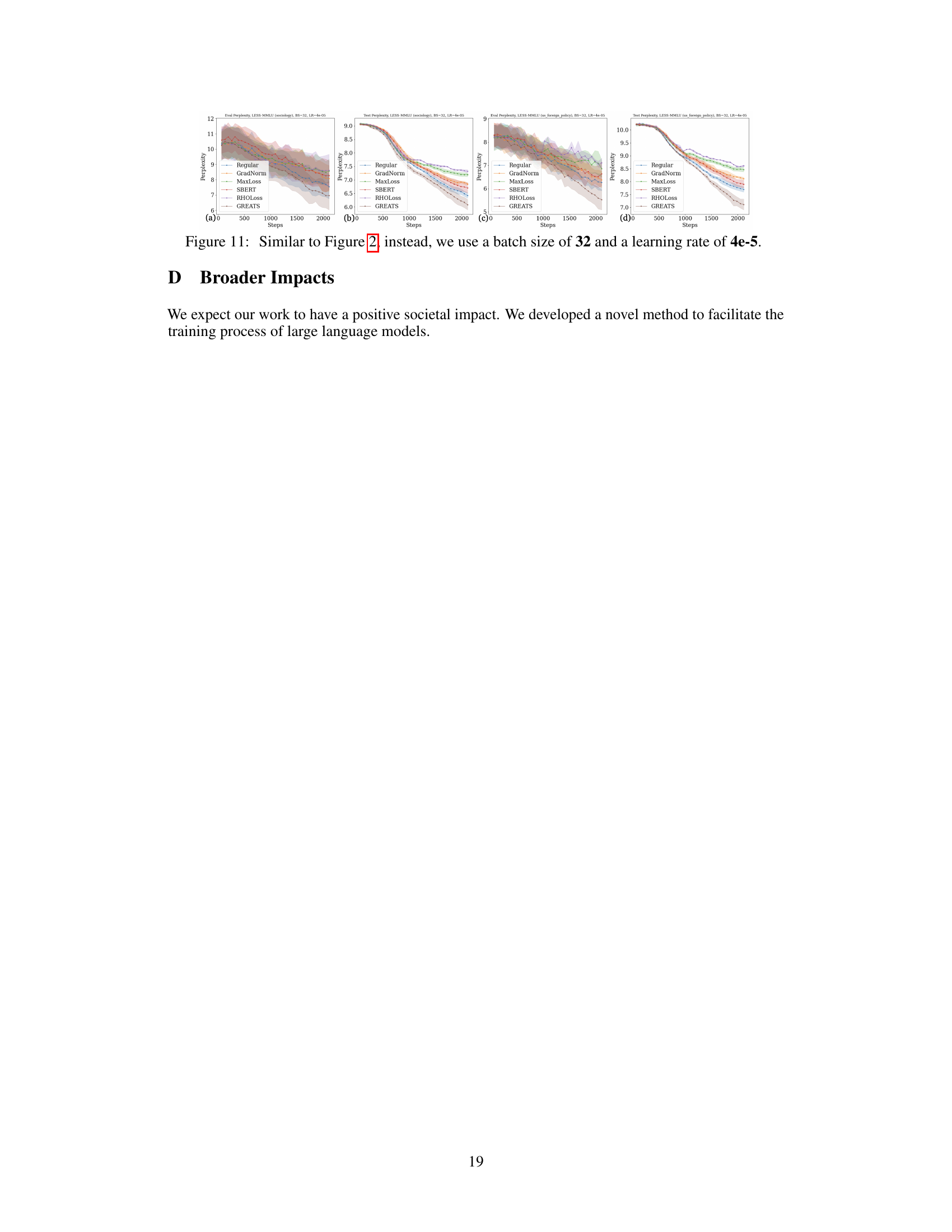

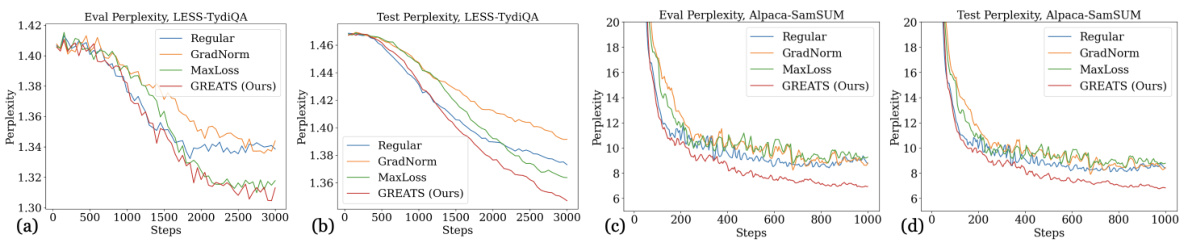

This figure displays the validation and test perplexity curves for several online batch selection methods across various settings. The x-axis represents training steps, and the y-axis represents perplexity. Each subplot shows results for a different model, task, or validation data size. The figure highlights the faster convergence and better generalization performance of GREATS (the proposed method) compared to other methods, particularly for smaller validation set sizes. The exclusion of SBERT and RHOLoss is noted due to high computational cost.

This figure shows the effect of the number of validation data points on GREATS’ performance in both fine-tuning and pre-training settings. Subfigures (a) and (b) demonstrate that even with a small number of validation points (2 or 3), GREATS still significantly improves the validation and test perplexity compared to regular training during the fine-tuning process. Subfigures (c) and (d) illustrate GREATS’ effectiveness in pre-training a GPT-2 model, showing that even in this setting, it offers better performance than regular training.

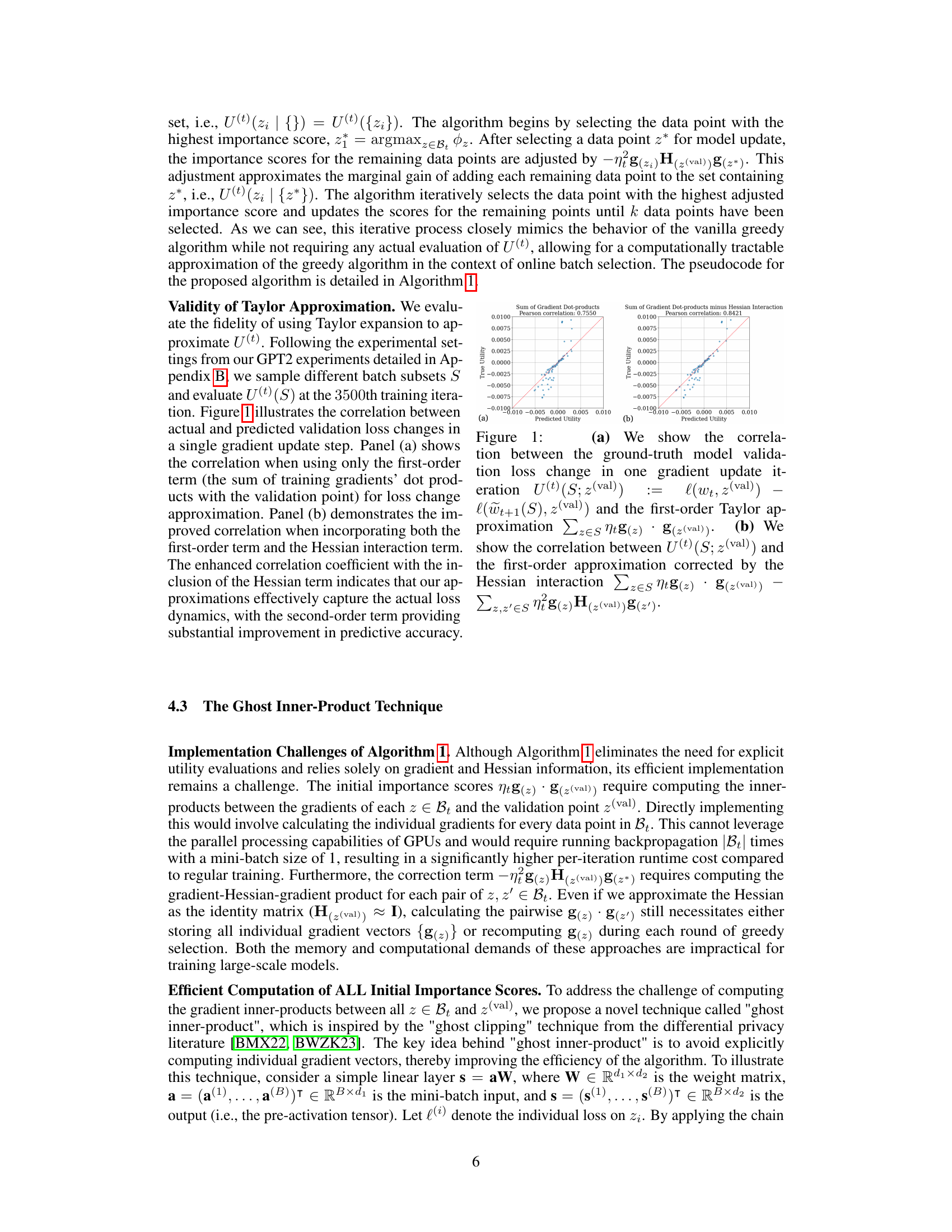

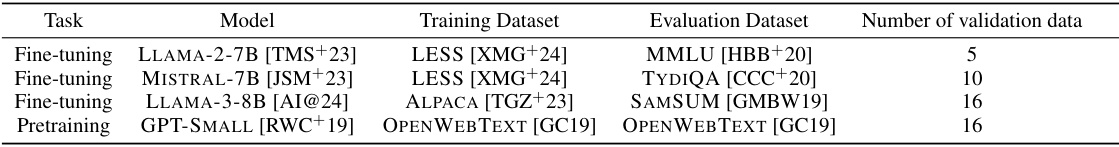

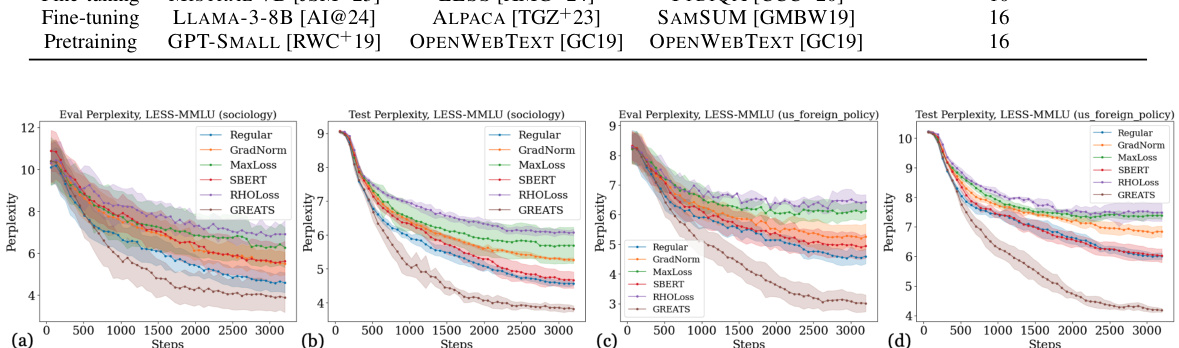

This figure displays the validation and test perplexity over training steps for different online batch selection methods applied to the MMLU benchmark. Two specific subjects within MMLU are examined: sociology and US foreign policy. The purpose is to demonstrate how GREATS compares to alternative online batch selection methods (Regular, GradNorm, MaxLoss, SBERT, RHOLoss) in terms of convergence speed and generalization performance. The results show that GREATS converges more quickly and achieves lower perplexity than other methods.

The figure shows the performance of different online batch selection methods (GREATS, Regular, GradNorm, MaxLoss) on various tasks (MMLU, TYDIQA, SAMSUM). It compares the validation and test perplexity over training steps, highlighting GREATS’s faster convergence and improved generalization.

More on tables

This table presents the experimental setup used in the paper, including the language models, training datasets, evaluation datasets, and the number of validation data points used for each experiment. The table shows four different model-training-evaluation setups used to evaluate the proposed GREATS algorithm. The models evaluated include LLAMA-2-7B, MISTRAL-7B, LLAMA-3-8B, and GPT-SMALL. The training datasets used are LESS and ALPACA. The evaluation datasets include MMLU, TYDIQA, SAMSUM, and OPENWEBTEXT. The number of validation data points used varies from 5 to 16 depending on the specific experiment. This information is crucial for understanding the scope and reproducibility of the experimental results presented in the paper.

This table shows different model-training-evaluation dataset combinations used in the paper’s experiments. It lists the specific large language models (LLMs) used (Llama-2-7B, Mistral-7B, Llama-3-8B), the training datasets employed (LESS, Alpaca), the evaluation datasets used (MMLU, TYDIQA, SAMSUM), and the number of validation data points for each combination. These combinations are used to comprehensively evaluate the GREATS algorithm’s performance across various language modeling tasks and conditions.

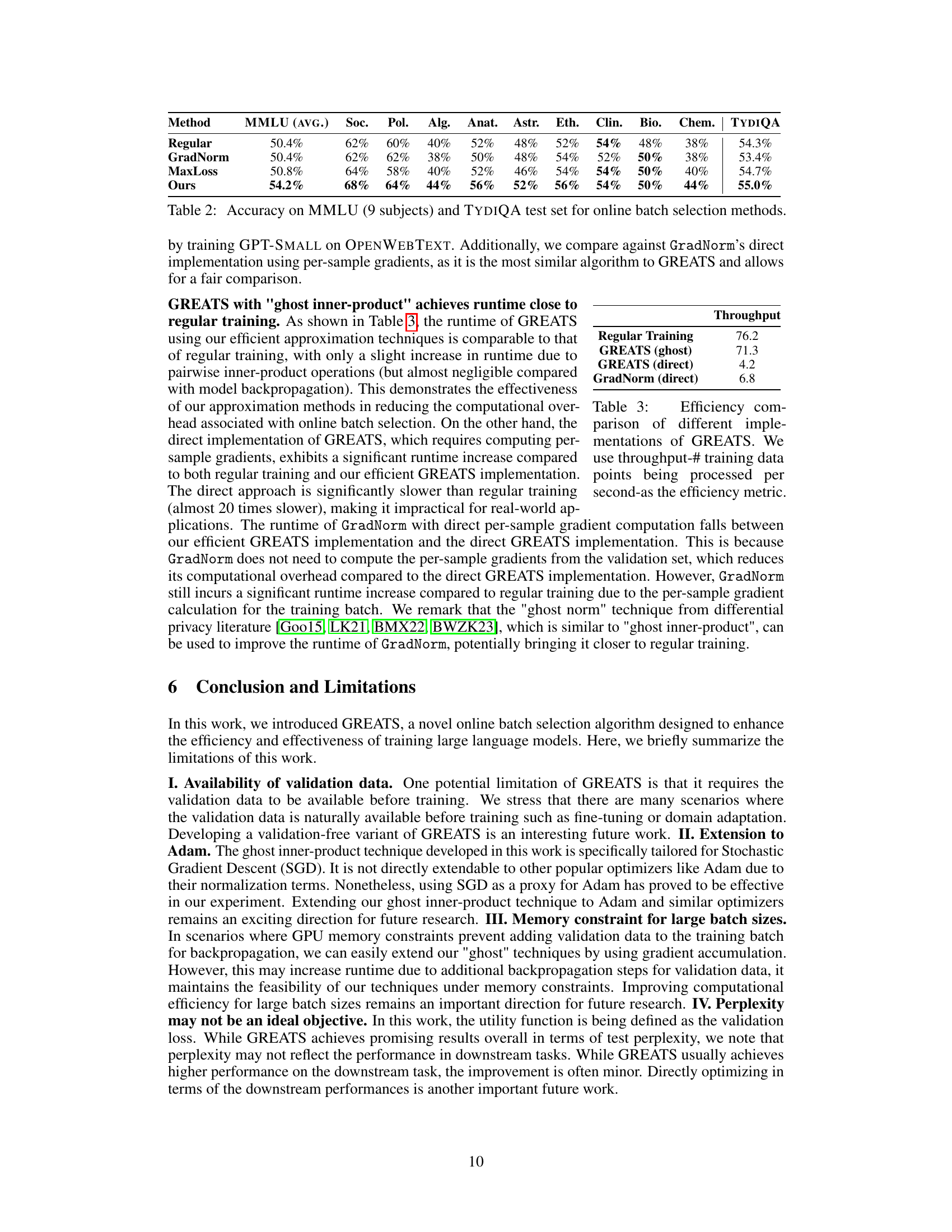

This table presents the accuracy results of different online batch selection methods on two benchmark datasets: MMLU (Multitask Language Understanding) and TYDIQA (Typologically Diverse Information-Seeking Question Answering). The MMLU results show the average accuracy across 9 randomly selected subjects, while TYDIQA provides a single accuracy score. The table allows comparison of the performance of GREATS against baseline methods such as Regular training, GradNorm, and MaxLoss, highlighting the improvement in accuracy achieved by GREATS.

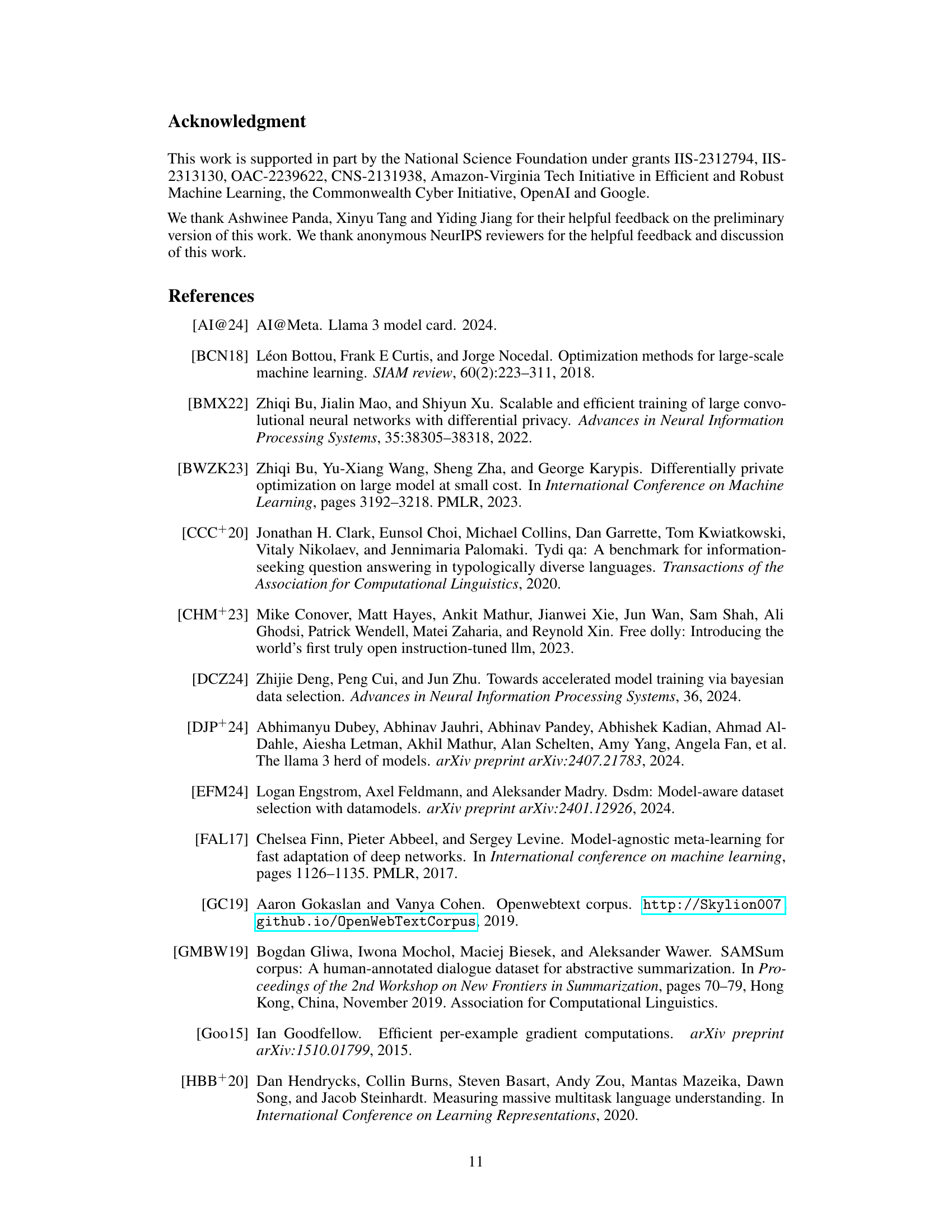

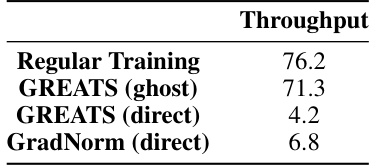

This table compares the efficiency of different implementations of the GREATS algorithm in terms of throughput (training data points processed per second). It contrasts the performance of GREATS using the ‘ghost inner-product’ technique, a direct implementation of GREATS, and a direct implementation of GradNorm. The ‘ghost inner-product’ method is shown to be significantly faster, nearly matching the speed of regular training. The direct implementations are considerably slower due to the computation of per-sample gradients.

Full paper#