↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Prior research struggled to produce non-vacuous generalization bounds for large language models due to limitations in using document-level compression techniques, and the bounds were vacuous for large models. Existing bounds often relied on restrictive compression, resulting in low-quality text generation. This paper tackles these challenges by focusing on tokens, the fundamental building blocks of text, and proposes a novel theoretical framework.

This work introduces a token-level generalization bound using martingale properties, which overcomes the limitations of document-level approaches. The new method utilizes diverse and less restrictive compression techniques, enabling the calculation of non-vacuous bounds for large, deployed LLMs while maintaining high-quality text generation. The results highlight a strong correlation between the theoretical bounds and actual downstream performance, advancing our theoretical understanding of LLMs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it offers the first non-vacuous generalization bounds for large language models (LLMs) used in practice, overcoming limitations of previous work. This opens new avenues for understanding LLM generalization, a critical area of current research, and offers insights into LLM training and compression strategies. The results are highly relevant to researchers developing and deploying LLMs.

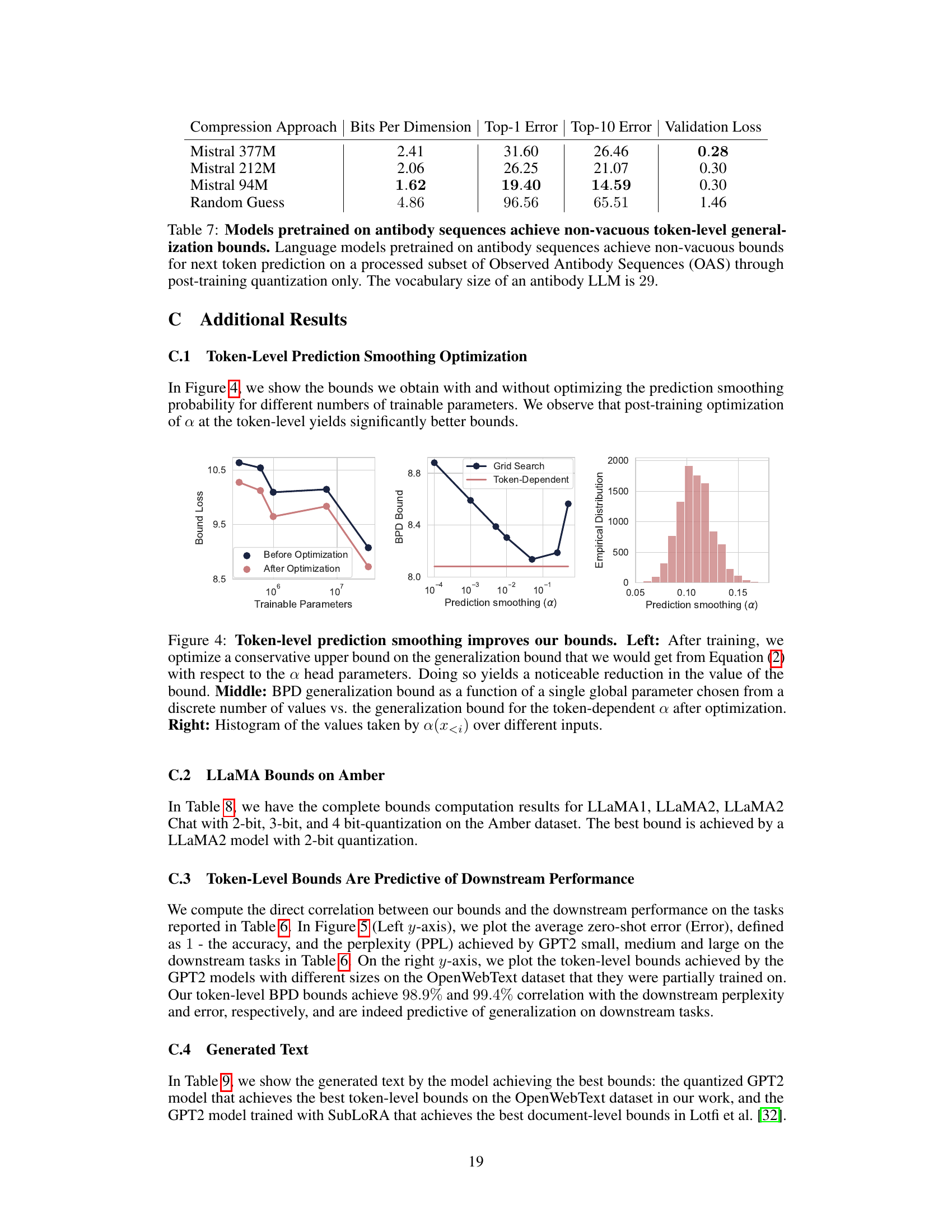

Visual Insights#

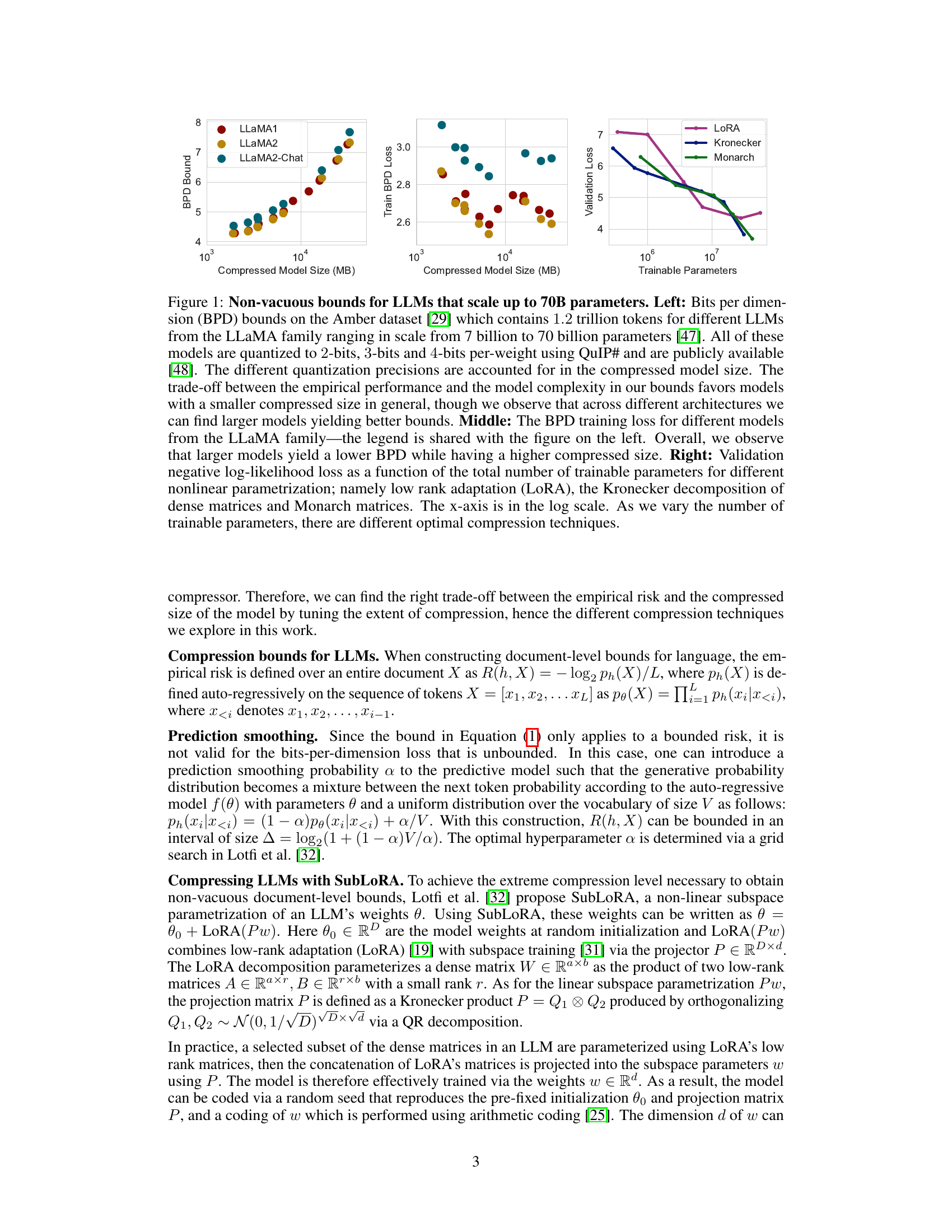

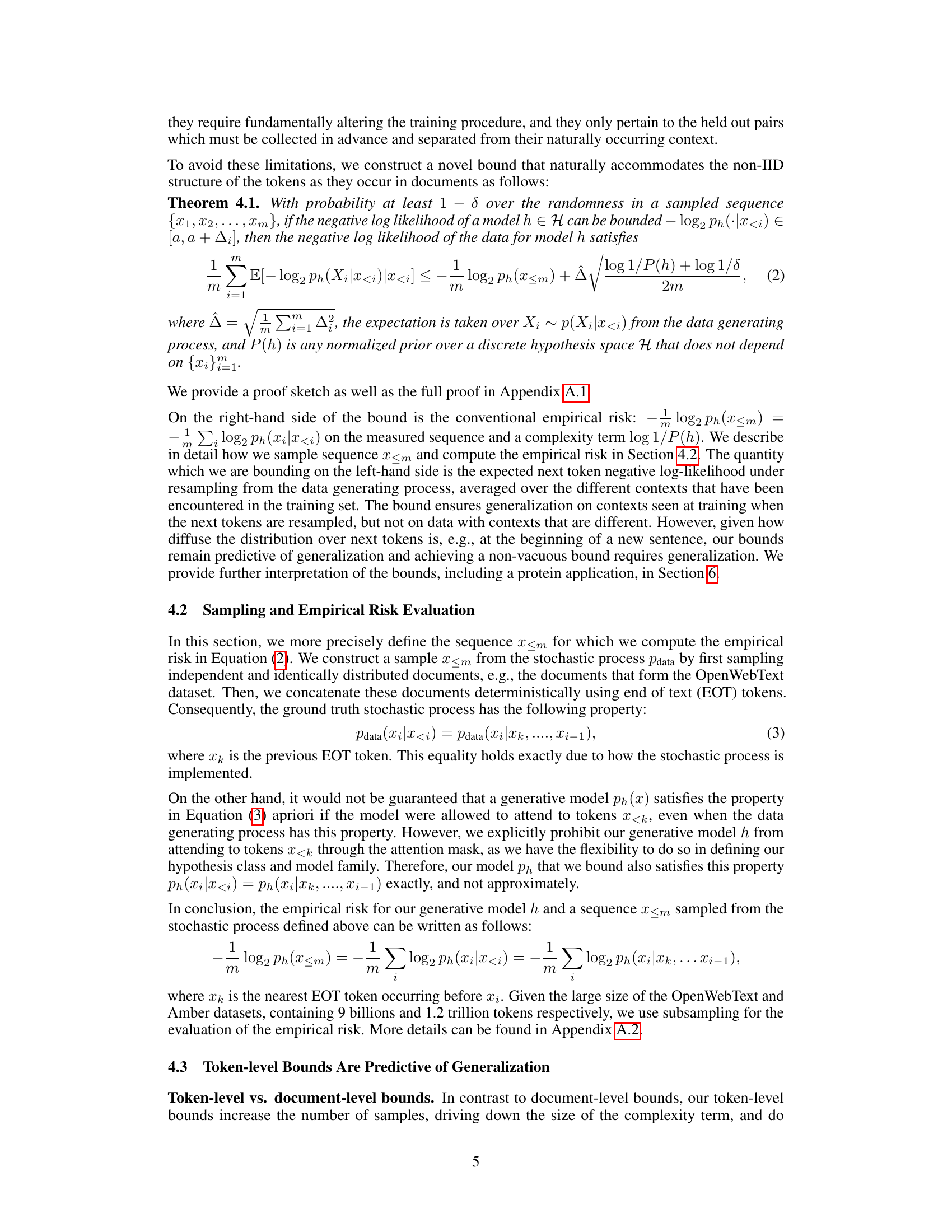

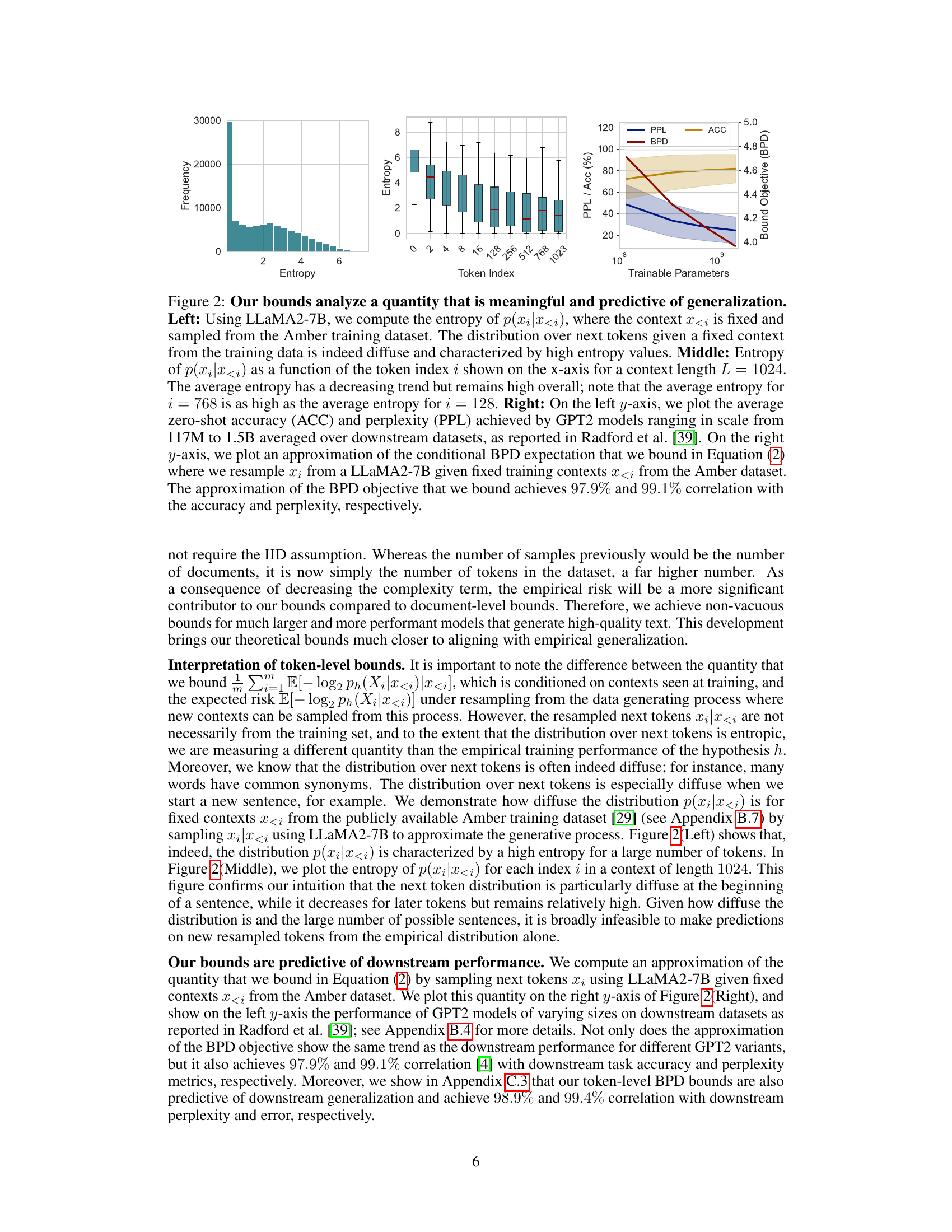

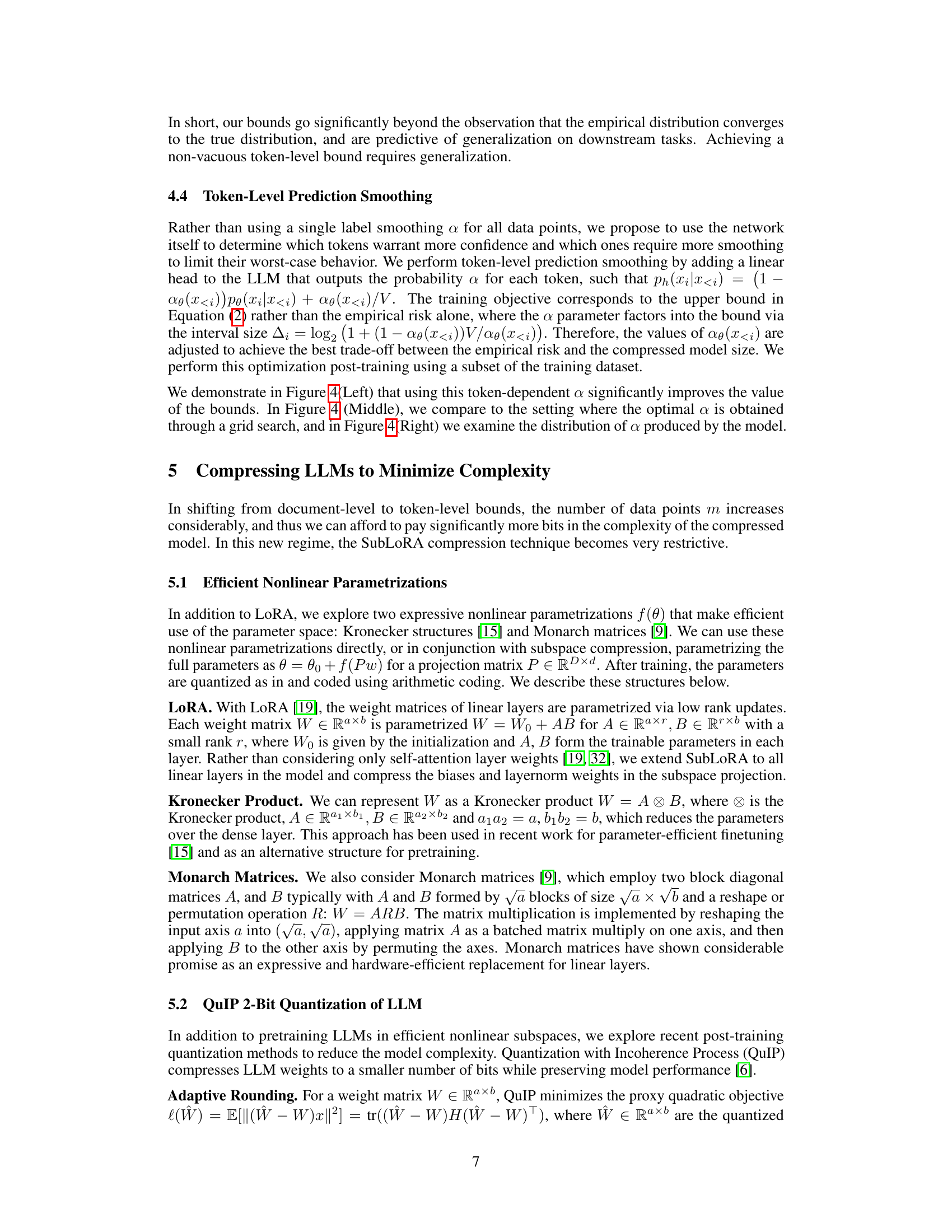

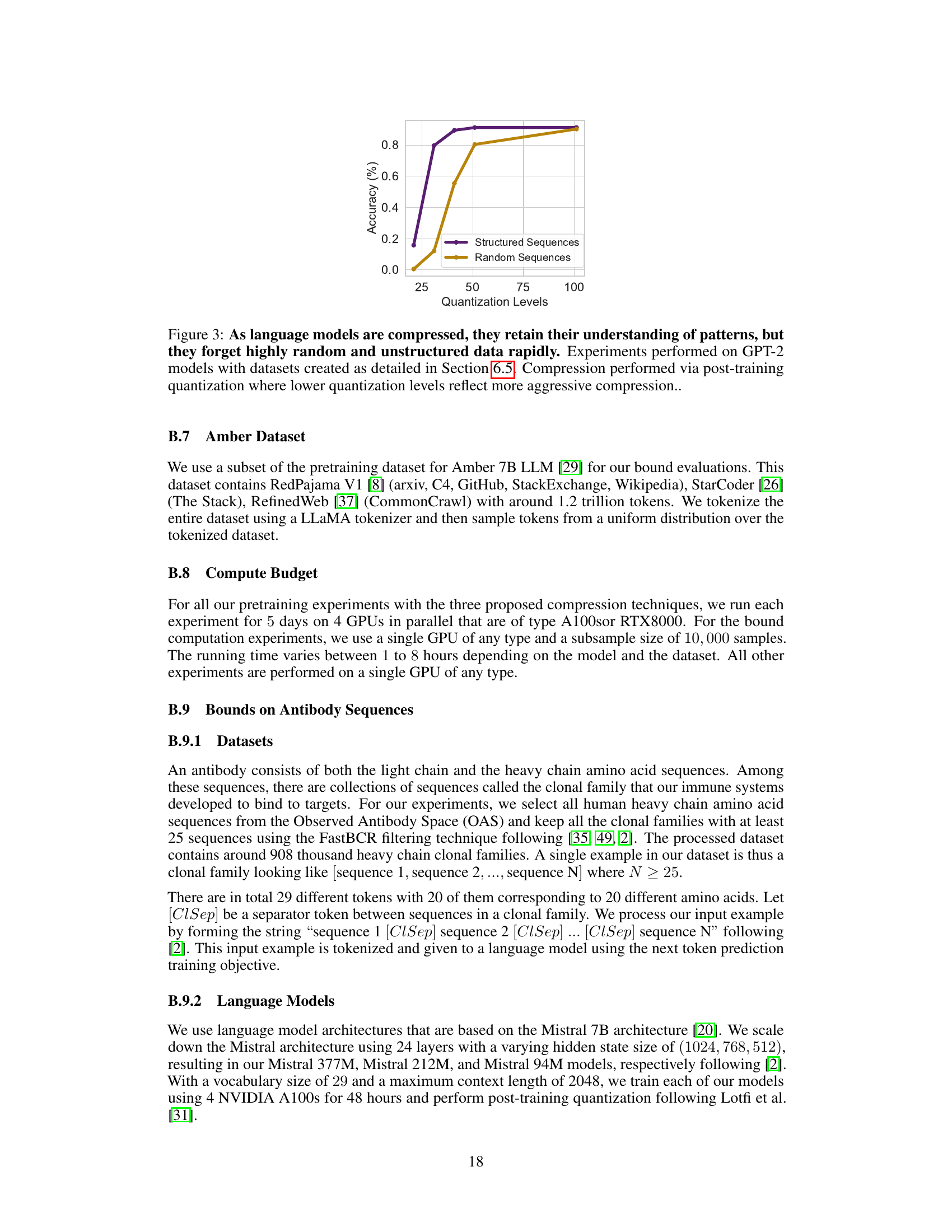

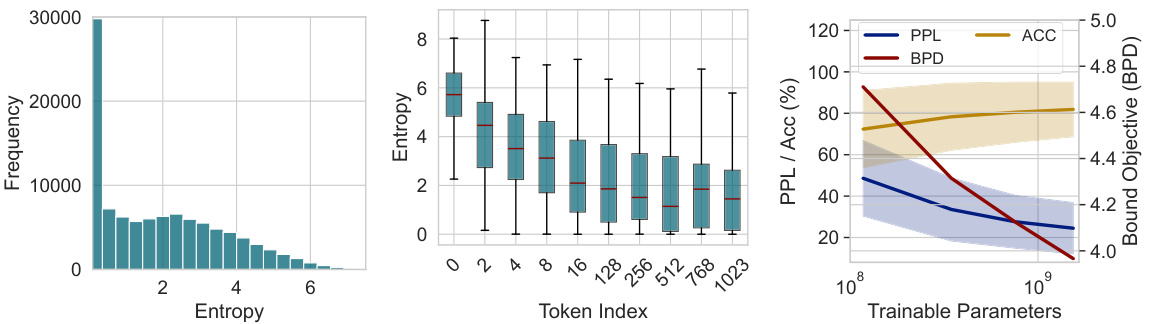

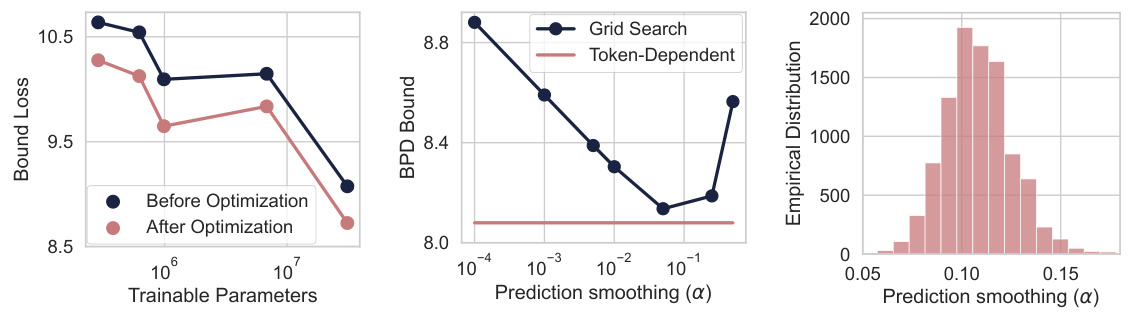

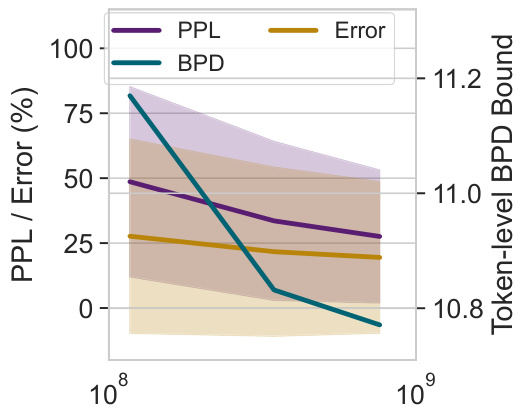

This figure displays the results of applying different compression techniques to large language models (LLMs). The left panel shows the bits-per-dimension (BPD) generalization bounds for several LLMs of varying sizes, demonstrating that the proposed method yields non-vacuous bounds for large models. The middle panel compares the training BPD loss against the model size, showing a trade-off between performance and size. The right panel shows the validation loss for different LLMs compressed with different methods (LoRA, Kronecker, Monarch), indicating that the optimal compression method varies with the number of trainable parameters.

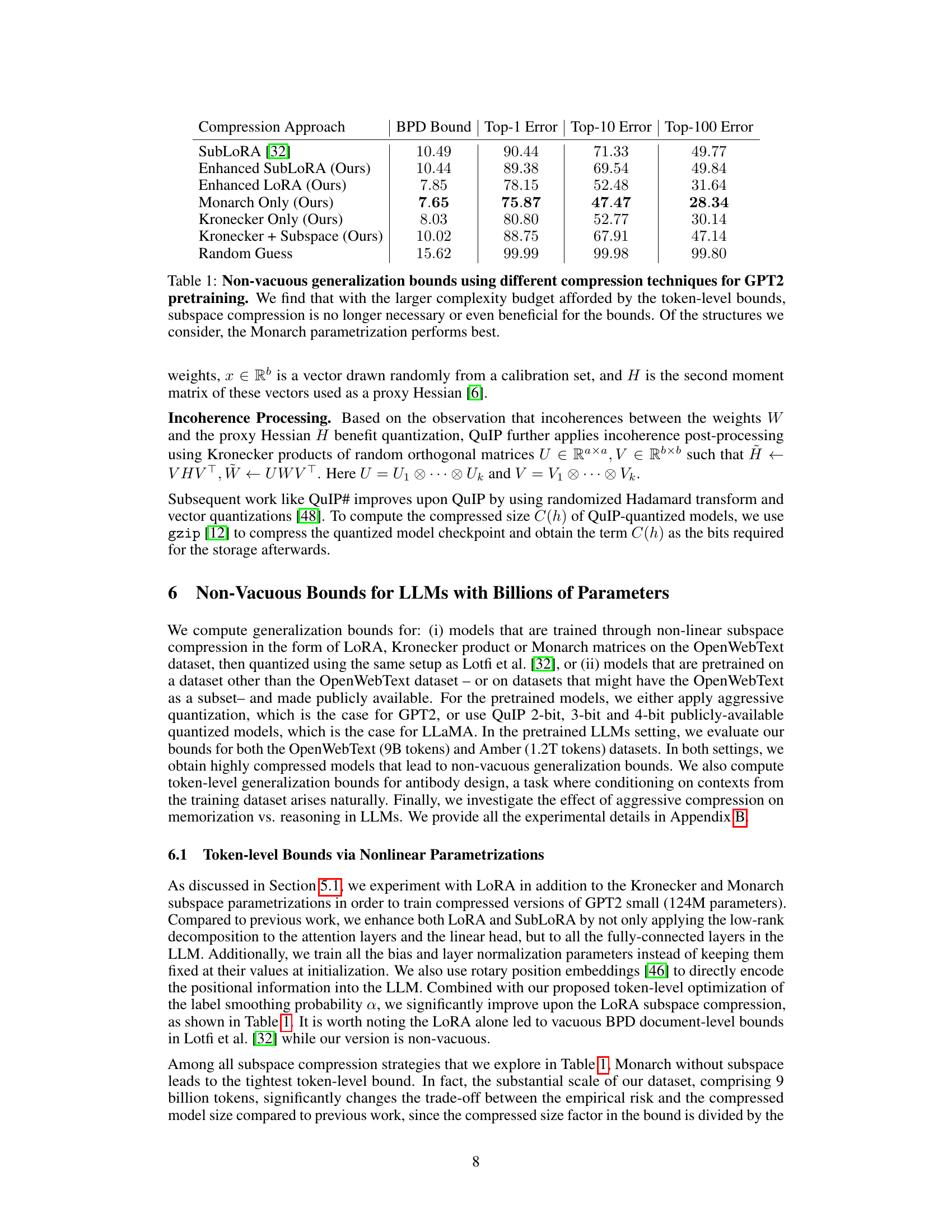

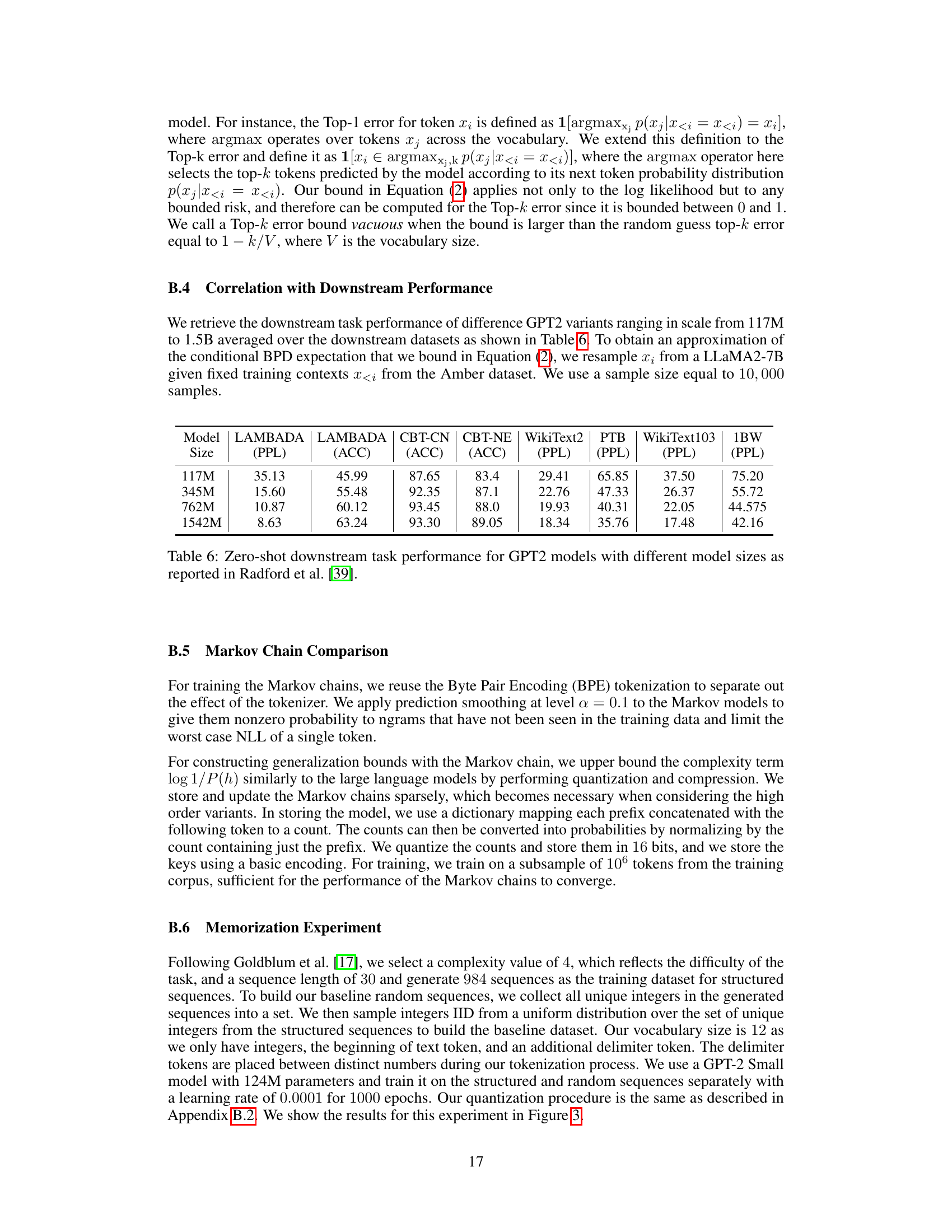

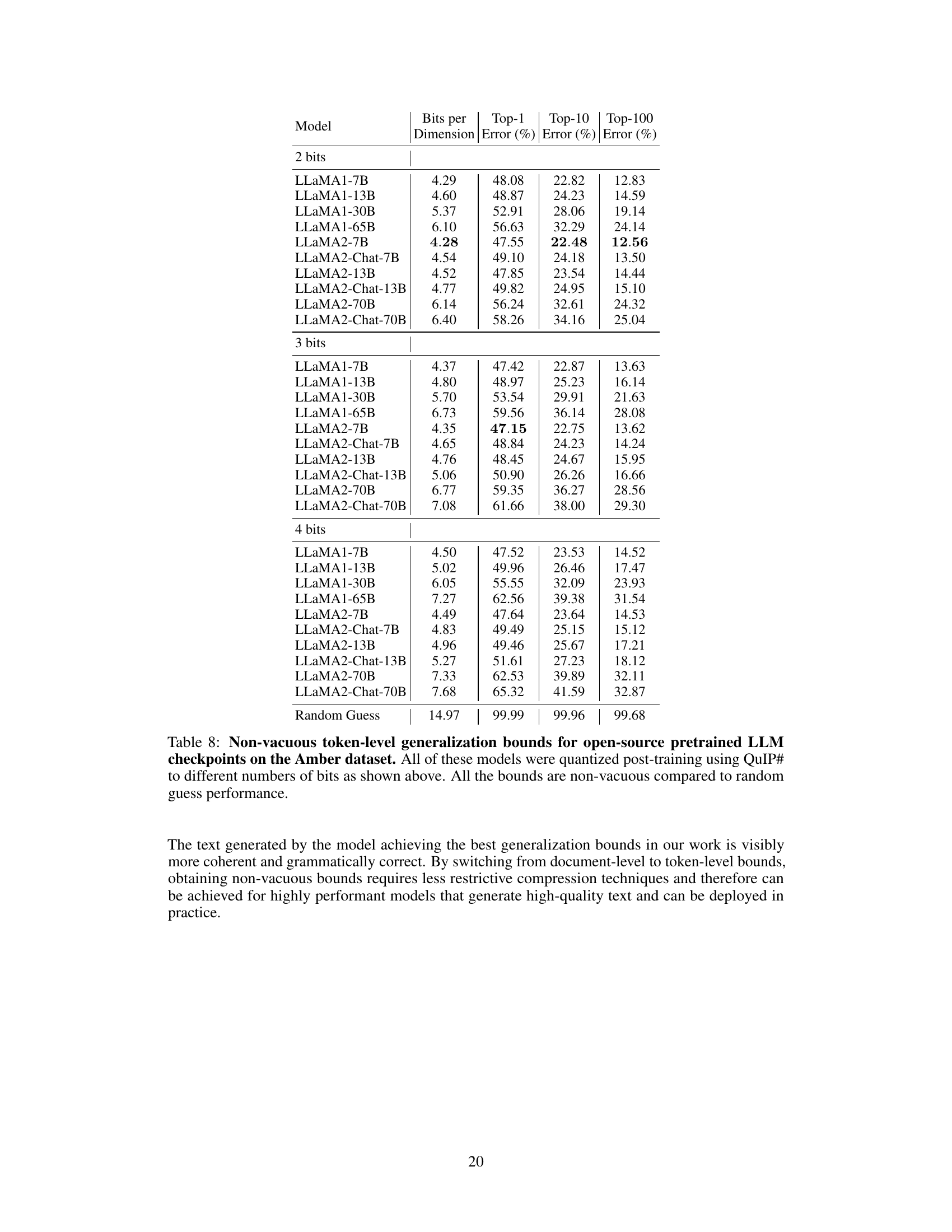

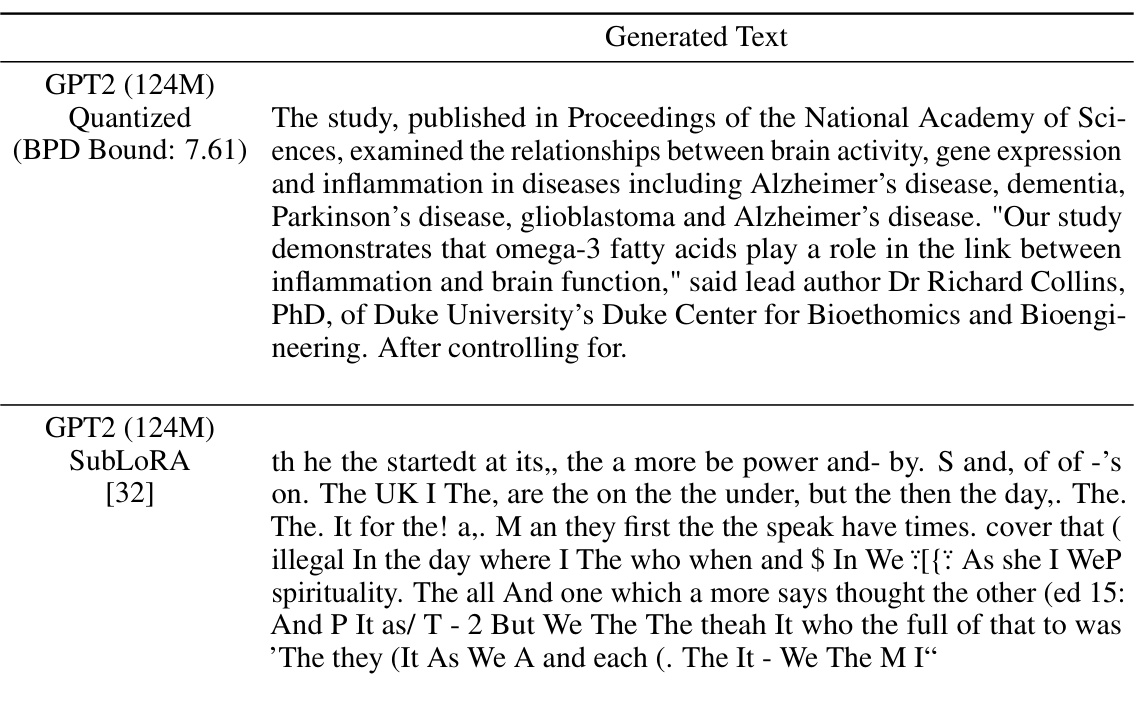

This table presents the results of non-vacuous generalization bounds for GPT2 models trained using different compression techniques: SubLoRA, Enhanced SubLoRA, Enhanced LoRA, Monarch Only, Kronecker Only, Kronecker + Subspace. The token-level bounds allow for less restrictive compression strategies compared to previous document-level approaches. The table shows that Monarch parametrization achieves the best results in terms of generalization bounds (BPD), with significantly lower error rates compared to random guessing and other techniques.

In-depth insights#

Token-Level Bounds#

The section on “Token-Level Generalization Bounds” presents a significant advancement in understanding large language model (LLM) generalization. Instead of treating documents as independent data points, the authors cleverly focus on individual tokens, leveraging the massive number of tokens in LLM training data. This shift allows for the derivation of tighter bounds that are not vacuous even for extremely large models. The use of martingale properties is key to handling the inherent non-IID nature of sequential data like text. This innovative approach enables the evaluation of generalization bounds on high-performing LLMs without requiring restrictive compression techniques that compromise text quality. Ultimately, this work provides a more nuanced and practical way to assess generalization in LLMs, moving beyond document-level analyses to a more granular, token-level perspective. The results are shown to be predictive of downstream performance, highlighting the real-world applicability of the novel bounds.

LLM Compression#

LLM compression techniques are crucial for deploying large language models (LLMs) efficiently and cost-effectively. Reducing model size lowers computational demands, making inference faster and cheaper. This is especially important for edge devices with limited resources. Different compression methods exist, such as pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation. Pruning removes less important connections, quantization reduces the precision of weights and activations, and distillation trains a smaller student model to mimic a larger teacher model. The trade-off between compression rate and performance is a major consideration. Aggressive compression can significantly reduce model size but may hurt accuracy. The choice of compression method depends on factors like hardware constraints, desired accuracy, and the nature of the LLM architecture. Post-training quantization is a popular method, as it doesn’t require retraining the model. Research into novel compression techniques is ongoing, aiming for better performance-efficiency trade-offs. Evaluating the impact of compression on various downstream tasks and generalization capabilities is also vital.

Martingale Approach#

A martingale approach leverages the properties of martingales, particularly their predictable nature, to derive generalization bounds for language models. This approach is especially valuable because the data points (tokens) in an LLM’s training set are not independently and identically distributed (non-IID), unlike the assumption in many classical generalization bounds. By viewing the sequence of tokens as a martingale, where the expected value of the next token is conditioned on the preceding tokens, one can obtain tighter generalization bounds. This avoids the limitations of document-level approaches, which group tokens into documents (often an arbitrary grouping) losing the rich token-level dependencies. The martingale approach is particularly effective for LLMs trained on massive datasets where the sheer number of tokens outweighs document counts, allowing more precise statistical estimates and therefore stronger bounds. The crucial aspect is that it exploits the inherent sequential structure of language rather than ignoring it, leading to a more realistic and informative evaluation of generalization capability.

Empirical Validation#

An Empirical Validation section in a research paper would rigorously test the claims and hypotheses presented. This would involve designing experiments to measure key variables, using appropriate statistical methods to analyze the collected data, and presenting the findings clearly and transparently. The strength of the validation lies in its replicability and generalizability. Ideally, the study would include sufficient details for others to reproduce the experiments and confirm the results. Any limitations in the methodology or data should also be acknowledged. A successful empirical validation would not only support the study’s claims but also provide insights into the robustness and boundary conditions of the model or theory. It is crucial to evaluate the extent to which the experimental setup and data accurately reflect the real-world scenarios for which the findings are intended. The results should be interpreted cautiously, taking into account the limitations of the study design and potential biases. The interpretation should avoid overgeneralization and should be accompanied by error analysis and discussion of potential confounding factors. The presentation should feature both quantitative and qualitative analysis to deliver a complete understanding.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore refined token-level generalization bounds that leverage document-level dependencies for improved accuracy. Investigating the interplay between model compression techniques and the inherent compressibility of tasks is crucial. Extending the theoretical framework to other modalities (e.g., images, audio) and evaluating the performance of these bounds on diverse downstream tasks would provide broader insights. Finally, exploring the connection between model compression, generalization, and emergent abilities in LLMs warrants further investigation, especially concerning whether the relationship between compression and generalization is fundamentally altered when considering emergent behaviors.

More visual insights#

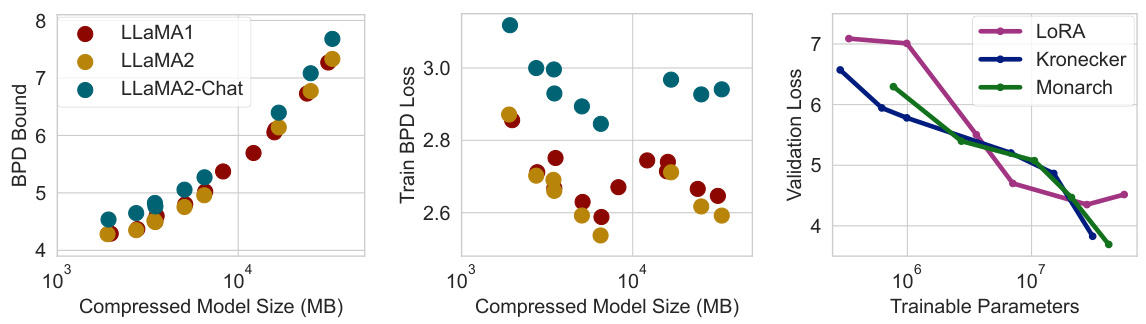

More on figures

This figure demonstrates the non-vacuous generalization bounds achieved for various LLMs (LLaMA family) with up to 70 billion parameters. The left panel shows the bits-per-dimension (BPD) bounds against compressed model size, highlighting the trade-off between compression and model performance. The middle panel compares training loss (BPD) across different LLaMA models, showcasing the relationship between model size and training loss. The right panel illustrates the validation loss against different compression techniques (LoRA, Kronecker, Monarch) across varying numbers of trainable parameters, revealing the optimal compression technique based on model size.

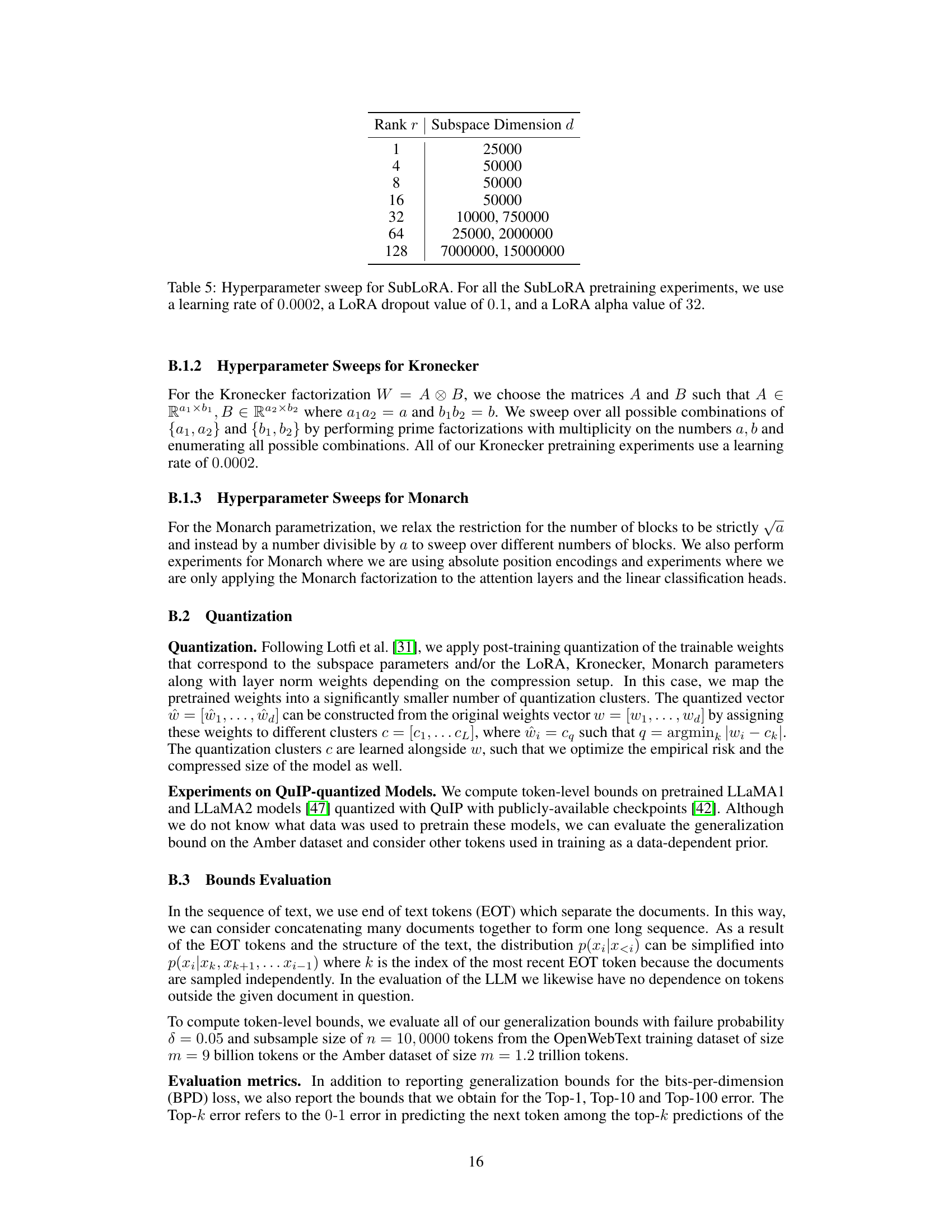

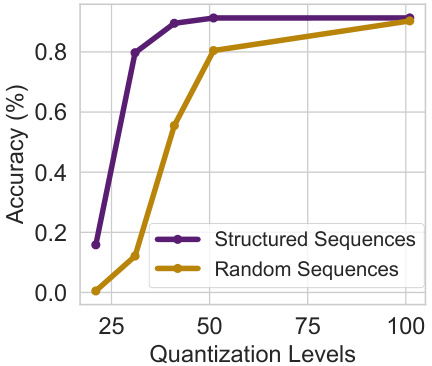

This figure shows the result of an experiment designed to differentiate between a model’s ability to memorize facts and its ability to recognize patterns. Two types of sequences were generated: structured (highly compressible) and random (incompressible). A GPT-2 model was trained on these sequences and then compressed using post-training quantization with varying levels of aggressiveness (quantization levels). The plot shows the accuracy of integer prediction for both types of sequences at different compression levels. The results indicate that as the model is compressed more aggressively, the ability to recall unstructured sequences deteriorates much faster than the ability to recognize structured patterns, highlighting the difference between memorization and pattern recognition in LLMs.

This figure shows the results of applying different compression techniques to several LLMs (LLaMA family) and evaluating their generalization bounds using three different metrics. The left panel shows bits per dimension (BPD) bounds versus compressed model size for various LLMs and quantization levels. The middle panel displays training BPD loss versus compressed size for the LLMs. The right panel compares validation loss for various compression methods (LoRA, Kronecker, Monarch) at different numbers of trainable parameters. It demonstrates the achieved non-vacuous generalization bounds for large models and the trade-off between compression and performance.

This figure presents a comprehensive analysis of non-vacuous generalization bounds for large language models (LLMs), specifically focusing on the LLaMA family. It shows the relationship between model size, compression techniques, and generalization performance using three key metrics: BPD (bits per dimension) bounds, training loss, and validation loss. The left panel demonstrates that even with models up to 70B parameters, non-vacuous bounds can be achieved. The middle panel reveals the relationship between training loss and model size, and the right panel shows how the choice of compression technique (LoRA, Kronecker, Monarch) influences validation loss at different parameter scales.

More on tables

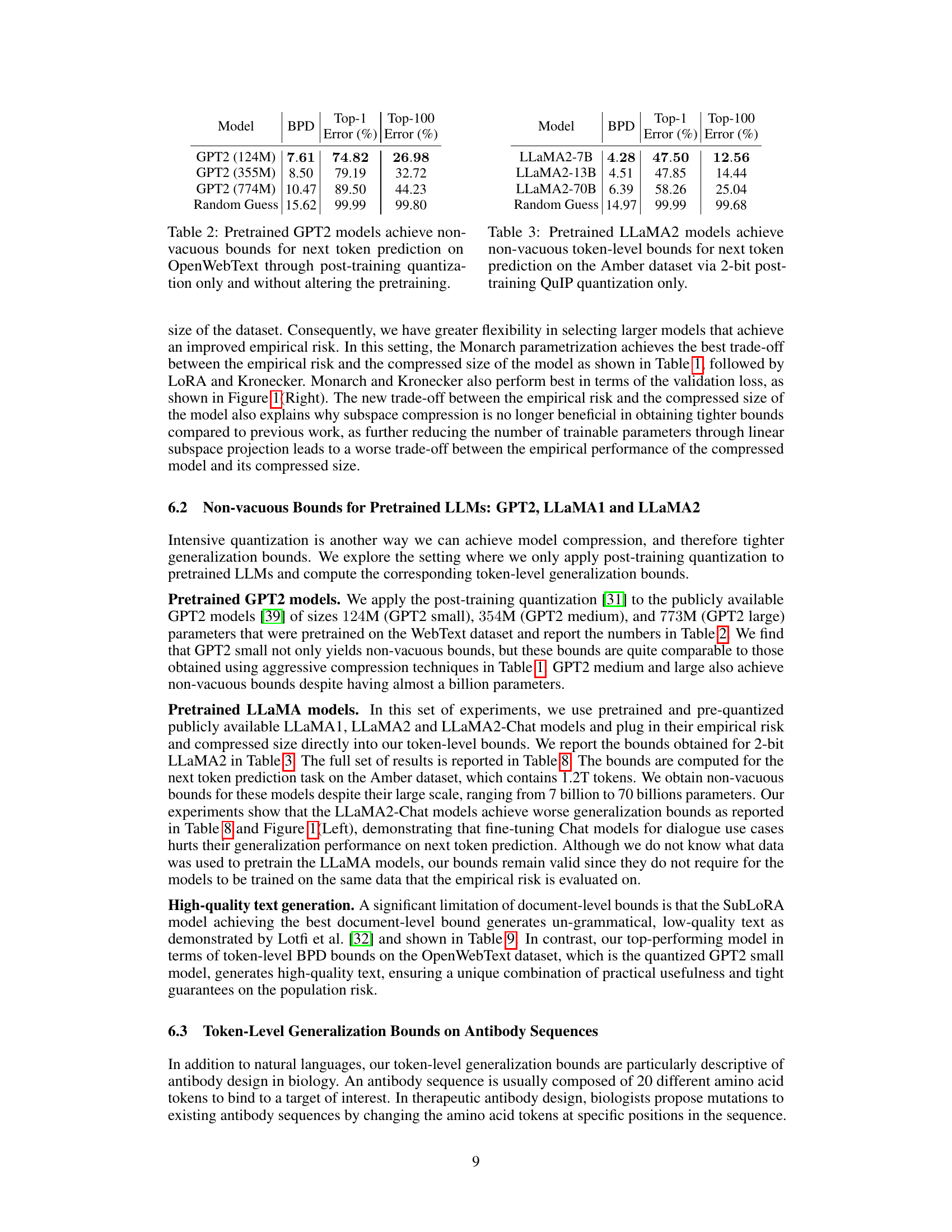

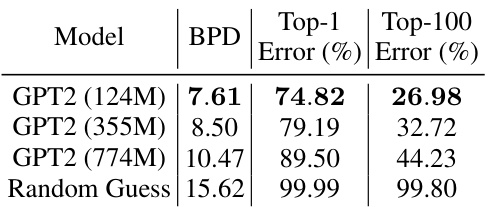

This table presents the results of applying post-training quantization to pretrained GPT2 models of varying sizes (124M, 355M, and 774M parameters). The table shows the achieved BPD (bits per dimension) bound, along with the Top-1 and Top-100 error rates. The key finding is that even with relatively large models, non-vacuous generalization bounds are achieved using only post-training quantization without modifying the original pretraining process.

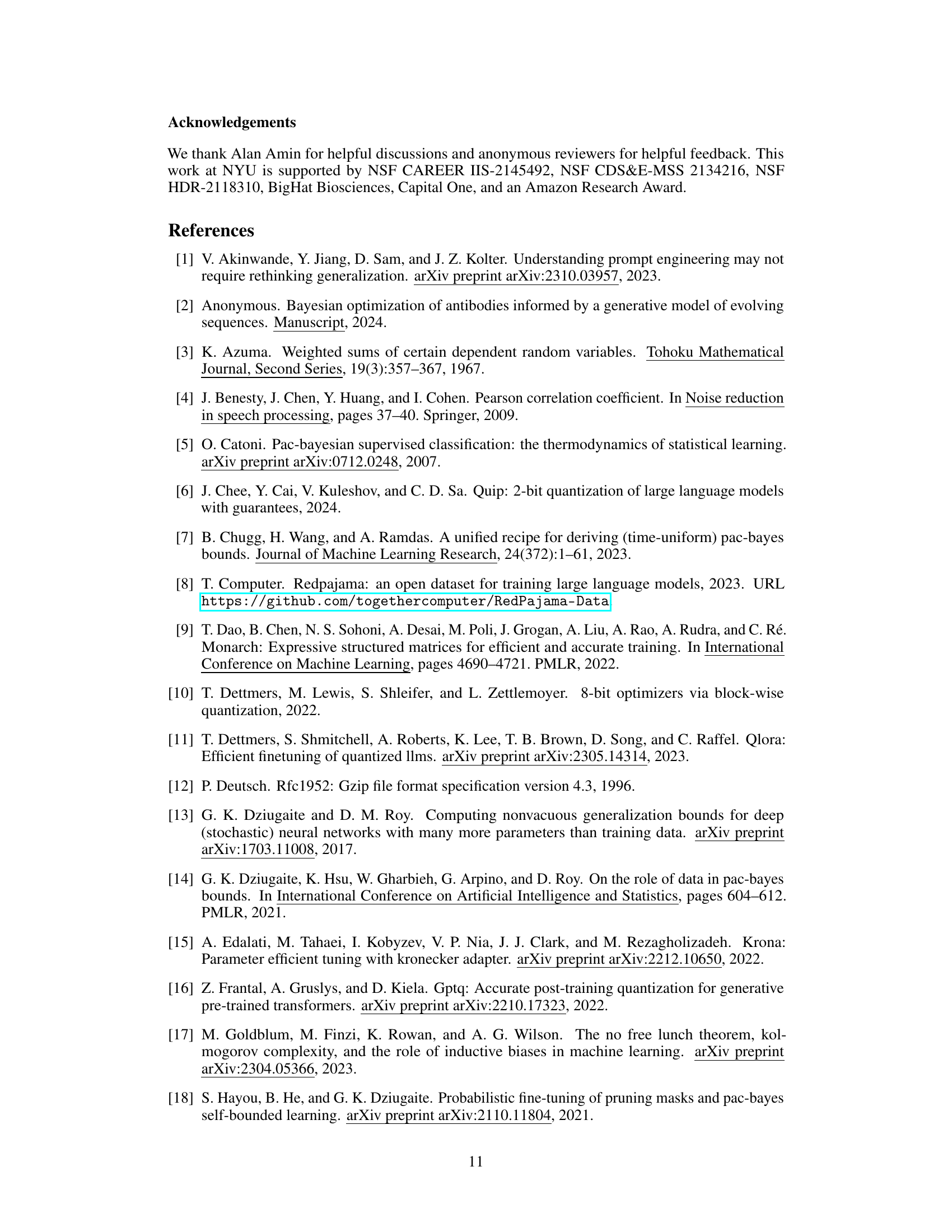

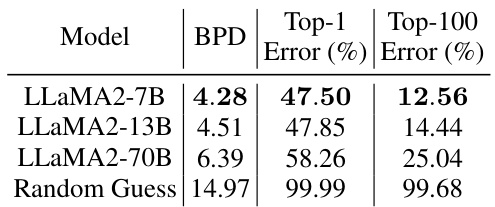

This table presents the results of applying post-training quantization to pretrained LLAMA2 models of varying sizes (7B, 13B, and 70B parameters). It shows the achieved non-vacuous generalization bounds (bits per dimension (BPD), Top-1 error, and Top-100 error) for the next-token prediction task on the Amber dataset. The results demonstrate that even very large language models can achieve non-vacuous generalization bounds with appropriate compression techniques (in this case, 2-bit quantization). A random guess baseline is also included for comparison.

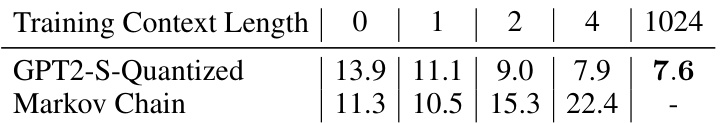

This table compares the bits-per-dimension (BPD) achieved by a quantized GPT2 small model and k-th order Markov chains on the OpenWebText dataset. The results show that the GPT2 model achieves significantly better bounds than the Markov chains, even for relatively high values of k (context length). This demonstrates that the model’s ability to predict the next token goes beyond simply memorizing short sequences of tokens (n-grams) and captures much longer-range correlations within the text.

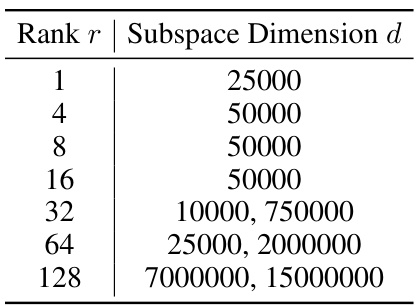

This table shows the results of applying various compression techniques (SubLoRA, enhanced SubLoRA, enhanced LoRA, Monarch Only, Kronecker Only, Kronecker + Subspace) to the GPT2 model for pretraining. The token-level bounds allow for less restrictive compression compared to document-level approaches. The table presents the BPD bound, Top-1, Top-10, and Top-100 errors for each compression technique, showing that Monarch parametrization gives the best results in terms of generalization bounds.

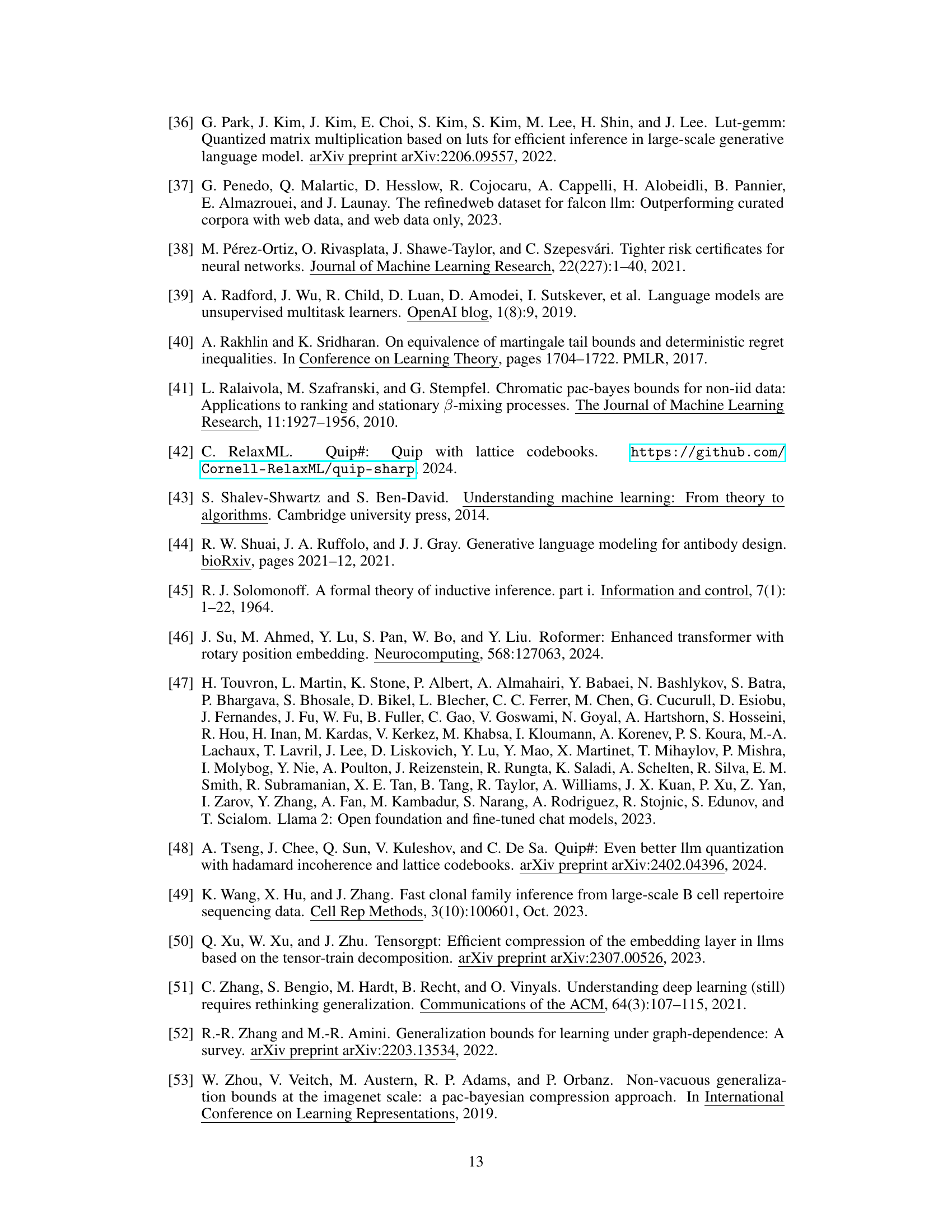

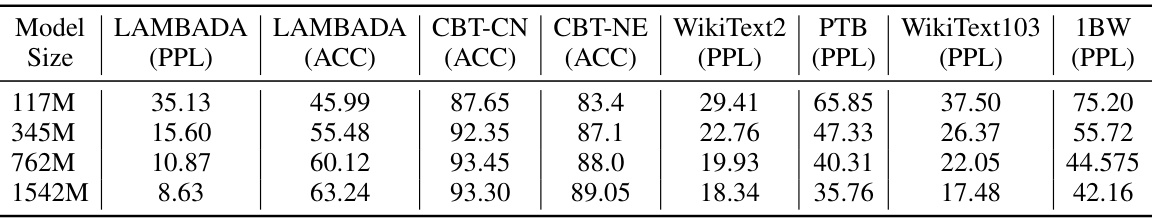

This table presents the zero-shot performance of GPT-2 models of varying sizes (117M, 345M, 762M, and 1542M parameters) on several downstream tasks. The tasks include LAMBADA (perplexity and accuracy), CBT-CN (accuracy), CBT-NE (accuracy), WikiText2 (perplexity), PTB (perplexity), WikiText103 (perplexity), and 1BW (perplexity). The results are adapted from Radford et al. [39] and showcase how model size affects zero-shot performance across diverse language modeling tasks.

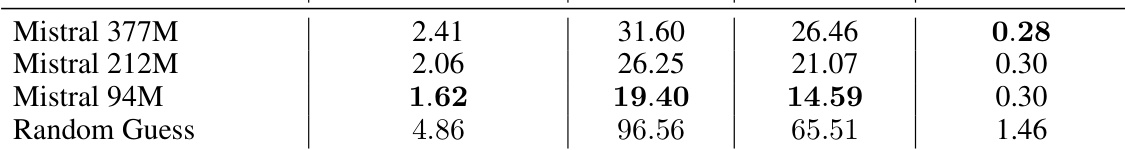

This table shows the results of applying the proposed token-level generalization bounds to language models pretrained on antibody sequences. The models used were Mistral 377M, 212M, and 94M, each with post-training quantization applied. The table shows the bits per dimension (BPD) bound achieved, along with the Top-1, Top-10, and Top-100 error rates. It highlights that even small models achieve non-vacuous generalization bounds on this specific dataset.

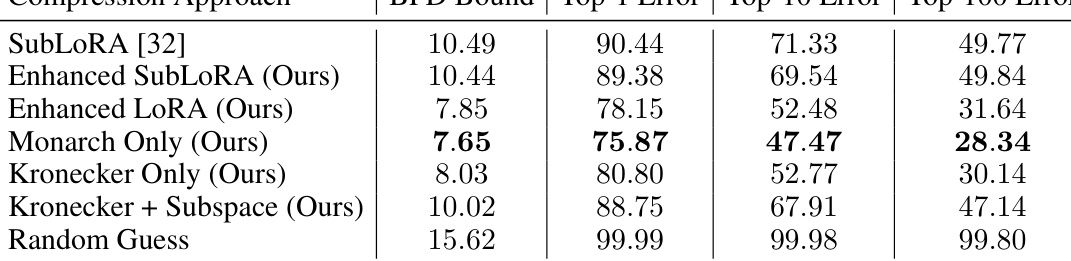

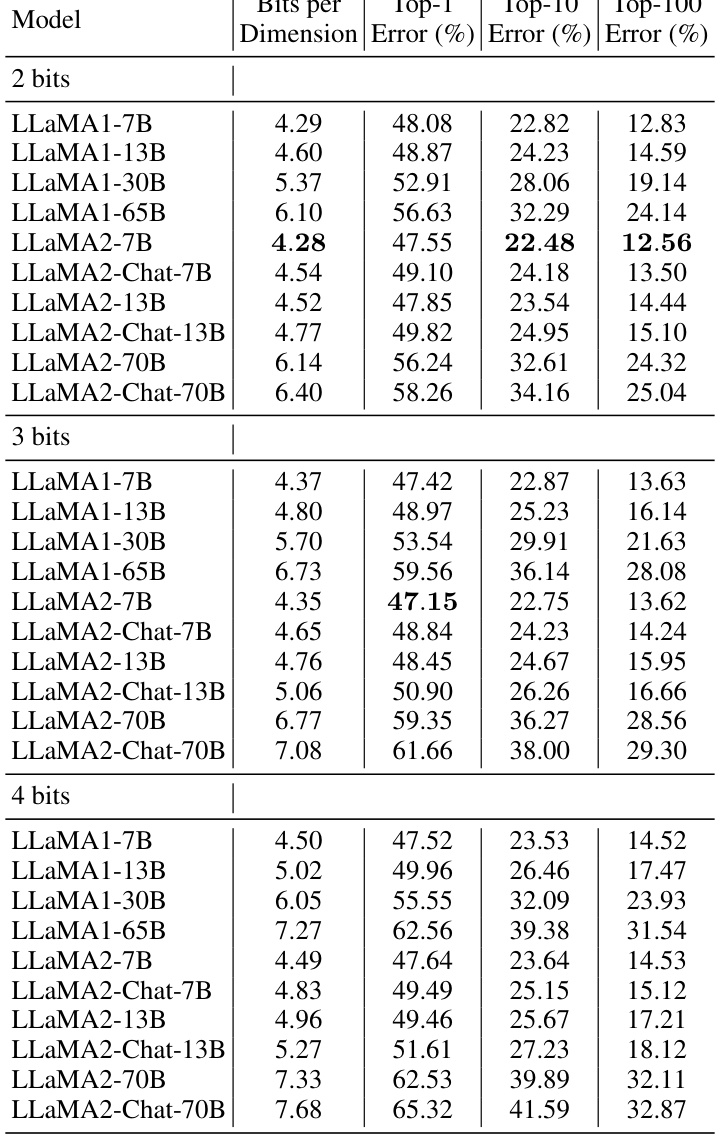

This table presents non-vacuous token-level generalization bounds for various open-source pretrained LLMs (LLaMA1 and LLaMA2, including chat versions) after post-training quantization using QuIP#. The bounds are calculated for different bit precisions (2, 3, and 4 bits) and model sizes, showing the bits per dimension (BPD), Top-1, Top-10, and Top-100 errors. The results demonstrate that even large language models with billions of parameters can achieve non-vacuous bounds using this method. The comparison with a random guess baseline highlights the significance of the obtained bounds.

This table presents the non-vacuous generalization bounds achieved using different compression techniques for GPT2 pretraining. The results show the impact of different compression methods (SubLoRA, enhanced SubLoRA, enhanced LoRA, Monarch only, Kronecker only, Kronecker + Subspace) on the BPD bound and Top-k errors. The token-level bounds allow for less restrictive compression, demonstrating that the Monarch parametrization yields the best results.

Full paper#