↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Fine-tuning large language models (LLMs) is computationally expensive. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods like LoRA aim to reduce this cost, but often suffer from slow convergence. This is because LoRA initializes adapter matrices randomly, leading to inefficient early training.

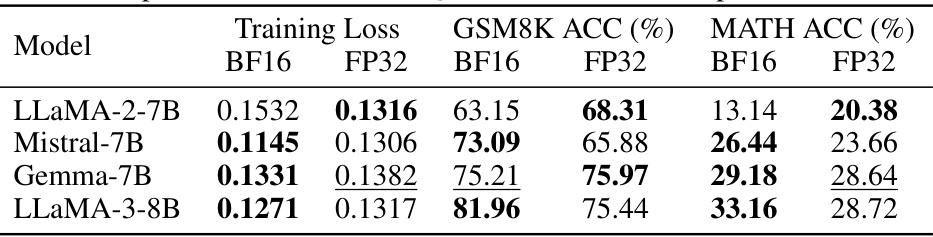

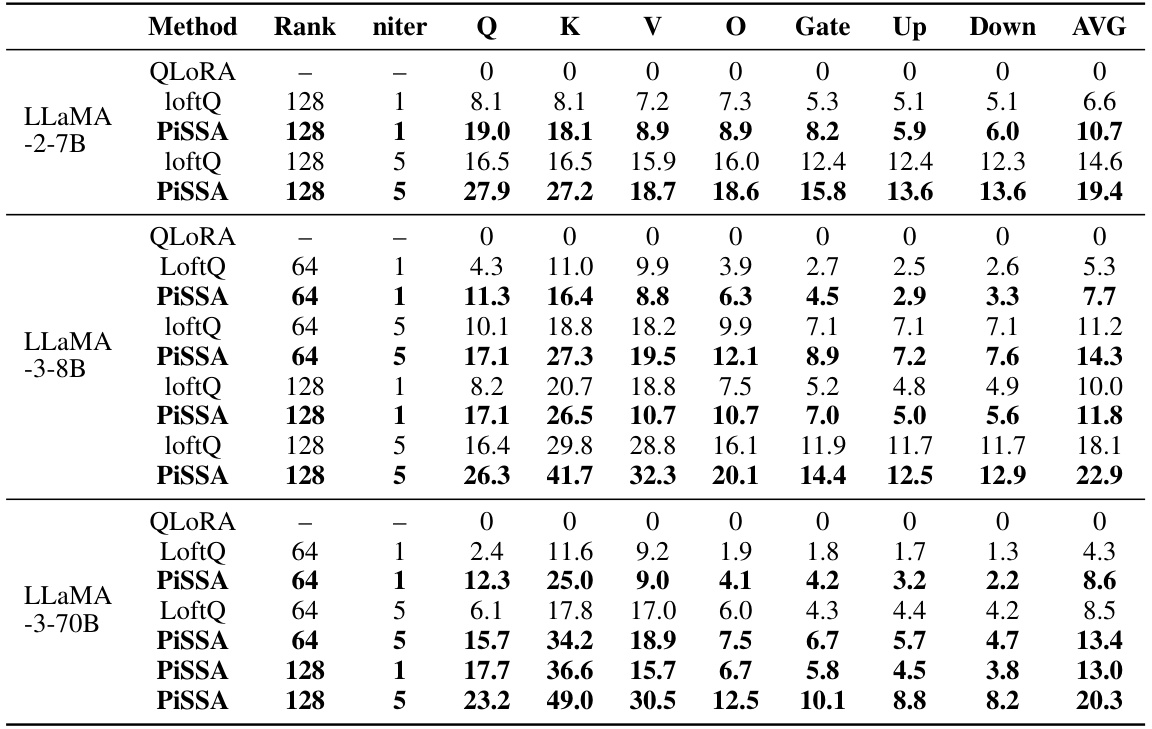

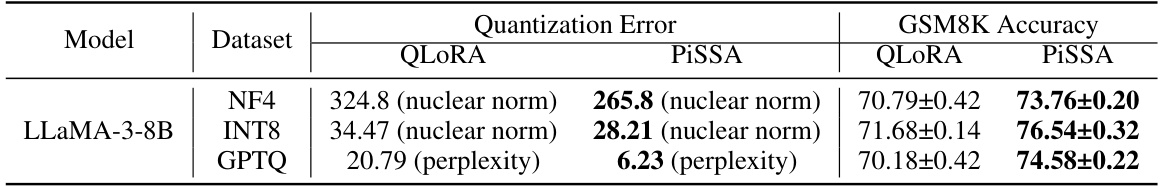

PiSSA addresses this by initializing adapter matrices using the principal components obtained through singular value decomposition (SVD) of the original model weights. By updating principal components while freezing residual parts, PiSSA achieves significantly faster convergence and better performance compared to LoRA across various models and tasks. PiSSA also demonstrates reduced quantization error when combined with quantization techniques.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in large language model (LLM) optimization because it introduces PiSSA, a novel parameter-efficient fine-tuning method that significantly outperforms existing techniques like LoRA. Its compatibility with quantization further enhances its practicality, addressing current challenges in memory and computational costs. The findings open avenues for exploring faster convergence strategies and improved LLM adaptability.

Visual Insights#

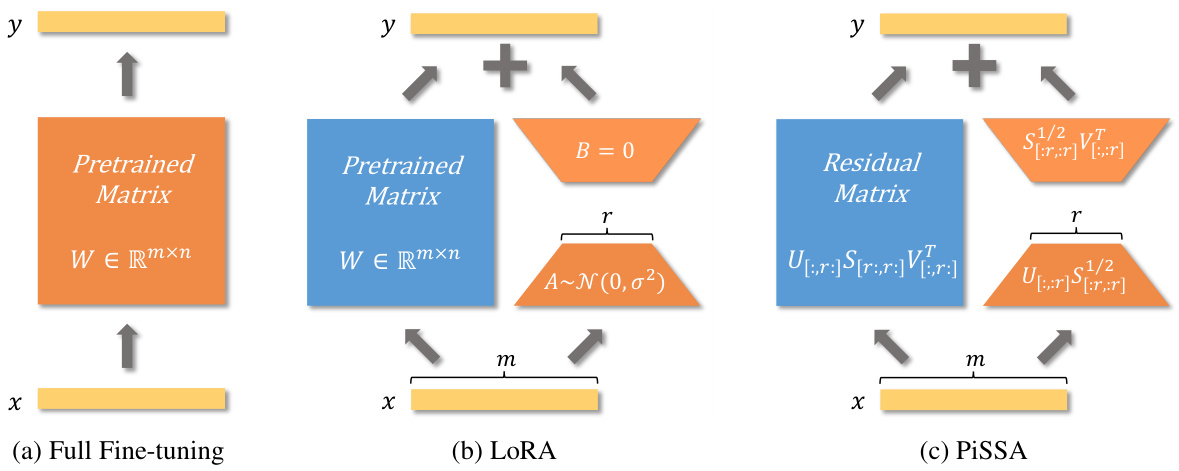

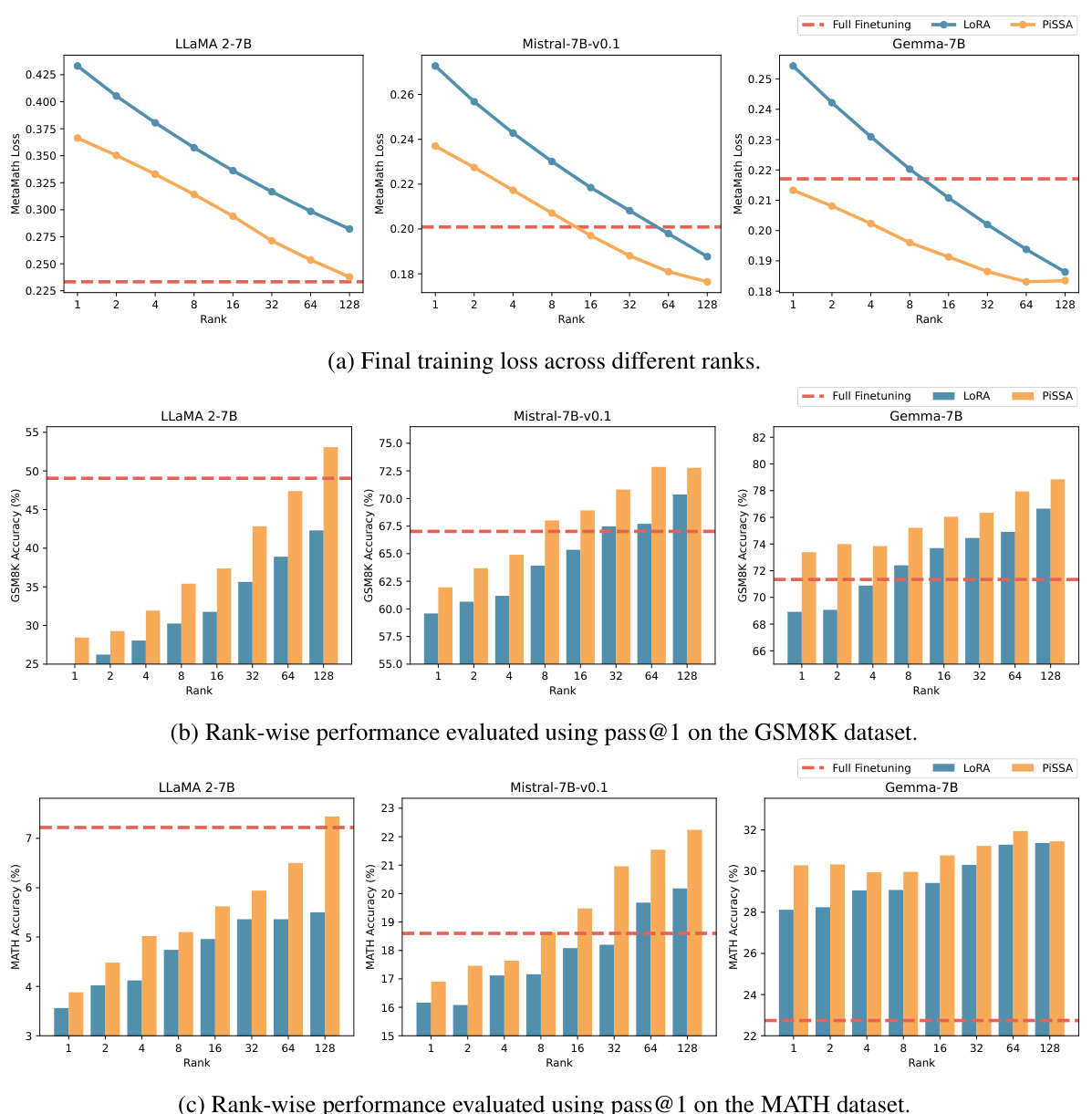

This figure compares three different fine-tuning methods for large language models: full fine-tuning, LoRA, and PiSSA. Full fine-tuning updates all model parameters. LoRA updates a low-rank approximation of the weight changes, freezing the original weights. PiSSA, similar in architecture to LoRA, initializes its update matrices with the principal components of the original weight matrix and freezes the residual components. The figure visually represents the different parameter update schemes, highlighting the frozen and updated parts of the model in each method. It also shows how quantization affects LoRA and PiSSA (QLoRA and QPiSSA).

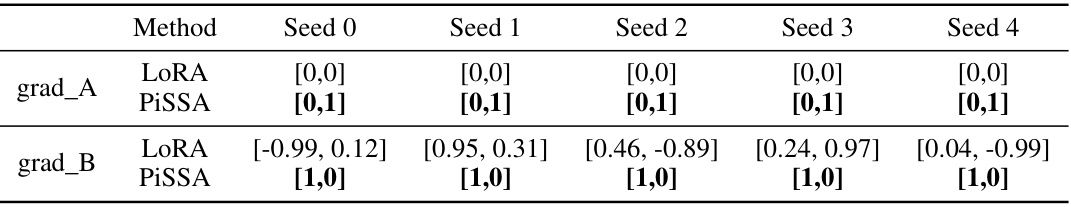

This table compares and contrasts the forward pass, initialization, gradient calculation, and overall comparison of PiSSA and LoRA. It highlights key differences in how each method handles weight updates and initialization, showing that PiSSA updates principal components while freezing residual components, leading to faster convergence and potentially better performance compared to LoRA.

In-depth insights#

PiSSA: Core Idea#

PiSSA’s core idea centers on improving the parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) of large language models (LLMs) by leveraging singular value decomposition (SVD). Unlike LoRA which initializes adapter matrices randomly, PiSSA cleverly uses the principal singular values and vectors of the original weight matrix W to initialize these adapters, while freezing the residual components. This initialization provides a significantly better starting point for optimization, leading to faster convergence and improved performance. The key advantage lies in directly tuning the most crucial aspects of the model, which correspond to the largest singular values, enabling more effective learning. This is opposed to LoRA’s method of only approximating changes to the model, which can lead to slow and inefficient training. By freezing the residual, less informative components PiSSA avoids the issues of slow convergence and suboptimal solutions often observed in LoRA. The speed and effectiveness of PiSSA is further enhanced by employing fast SVD techniques, minimizing the computational overhead of this crucial initialization step.

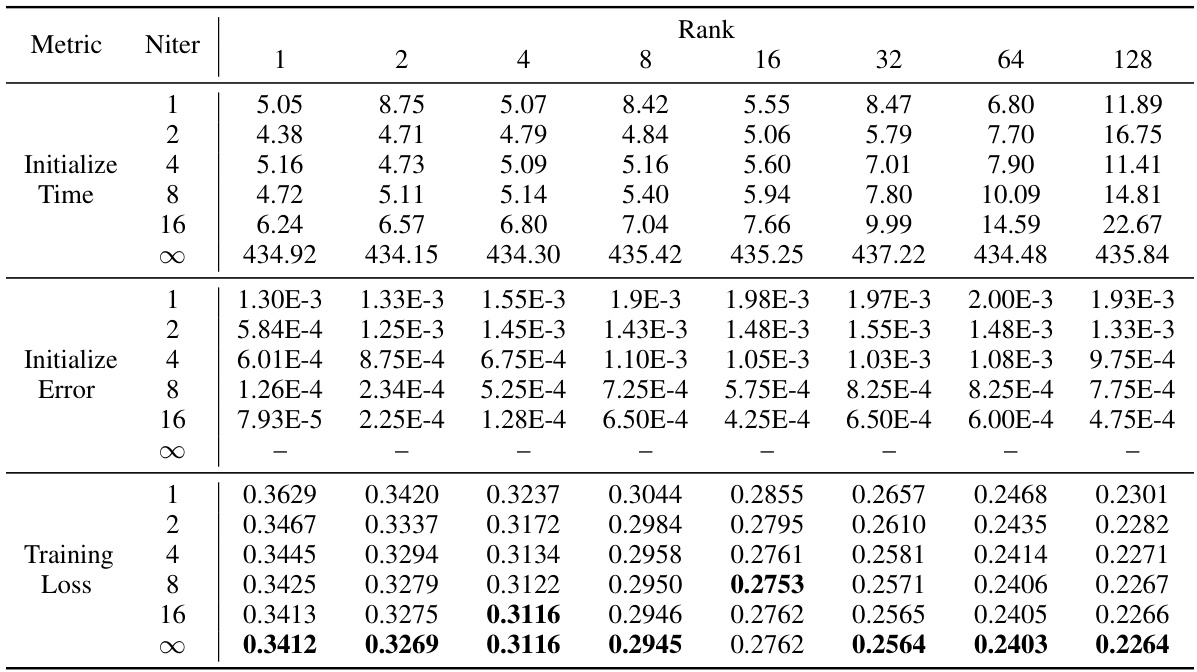

SVD-Based Init#

The heading ‘SVD-Based Init’ strongly suggests a method utilizing Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) for initializing model parameters, particularly within the context of large language models (LLMs). SVD’s role is likely to reduce the dimensionality of the parameter space, making the optimization problem more tractable and potentially accelerating convergence during fine-tuning. The approach likely involves decomposing the original weight matrices into principal components using SVD. The principal components, capturing most of the variance, would be used to initialize the trainable parameters of an adapter or low-rank approximation. This initialization strategy contrasts with random initialization which might lead to slower convergence and suboptimal solutions. By leveraging SVD, the method aims for a more informed starting point, facilitating faster training, better performance, and potentially reducing computational costs. The effectiveness likely depends on several factors: the rank of the approximation, the choice of singular values to include, and the specific architecture of the model being adapted. Further, the computational cost of the SVD itself must be considered. The key benefit lies in a theoretically principled approach to initialization, offering an advantage over purely random methods.

Quantization#

The concept of quantization in the context of large language models (LLMs) is crucial for efficient fine-tuning and deployment. Quantization reduces the memory footprint of LLMs by representing weights and activations using fewer bits, leading to significant computational savings. However, quantization introduces errors that can degrade model performance. The research explores strategies to mitigate these errors, such as carefully selecting which parts of the model to quantize, focusing on less critical components to minimize impact on accuracy. A key innovation is the combination of quantization with low-rank adaptation (LoRA) techniques. By quantizing only the residual components left after low-rank approximation, the approach minimizes quantization errors while preserving essential model information. The resulting hybrid approach offers the advantage of both computational efficiency and high accuracy, making LLMs more practical for deployment on resource-constrained devices. The analysis of quantization error is a core aspect, with methods proposed to reduce error and maintain performance. Comparing the quantization error reduction ratio across different methods reveals the effectiveness of the proposed approach and its superiority over existing methods. Ultimately, research in this area aims to find the optimal balance between model accuracy and computational cost, making LLMs more accessible and widely deployable.

Experiment#

The experiments section of a research paper is crucial for validating the claims and demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed methods. A well-structured experiments section should clearly define the research questions, methodologies, datasets used, and evaluation metrics. It’s important to highlight the experimental design, including data splits (train/validation/test), hyperparameter settings, and any randomization techniques. Replicability is key, so sufficient details are vital. The analysis should go beyond raw results, including error bars, statistical significance tests (e.g., p-values) to gauge the reliability of findings. Comparing against strong baselines is important to demonstrate the advantage of the new approach. The discussion of the results should be objective, analyzing both the successes and limitations, and acknowledging any unexpected outcomes. Furthermore, a thorough discussion of limitations and potential biases helps build the paper’s credibility, demonstrating a thoughtful understanding of the work’s scope and impact. A well-written experiment section, therefore, contributes significantly to a research paper’s overall impact and acceptance.

Future Work#

The ‘Future Work’ section of this research paper could explore several promising avenues. Extending PiSSA’s applicability beyond language models to convolutional neural networks and other architectures for vision tasks would significantly broaden its impact. Investigating the theoretical underpinnings of PiSSA’s success, perhaps by analyzing its optimization landscape, could yield valuable insights and potentially lead to further improvements. Adaptive rank adjustments, inspired by AdaLoRA’s dynamic rank selection, could optimize PiSSA’s performance by automatically tailoring the rank to different layers or tasks. Finally, a thorough investigation into the interaction between PiSSA and other parameter-efficient fine-tuning techniques is warranted. Combining PiSSA with quantization techniques or other adaptation methods could result in even more efficient and effective fine-tuning strategies.

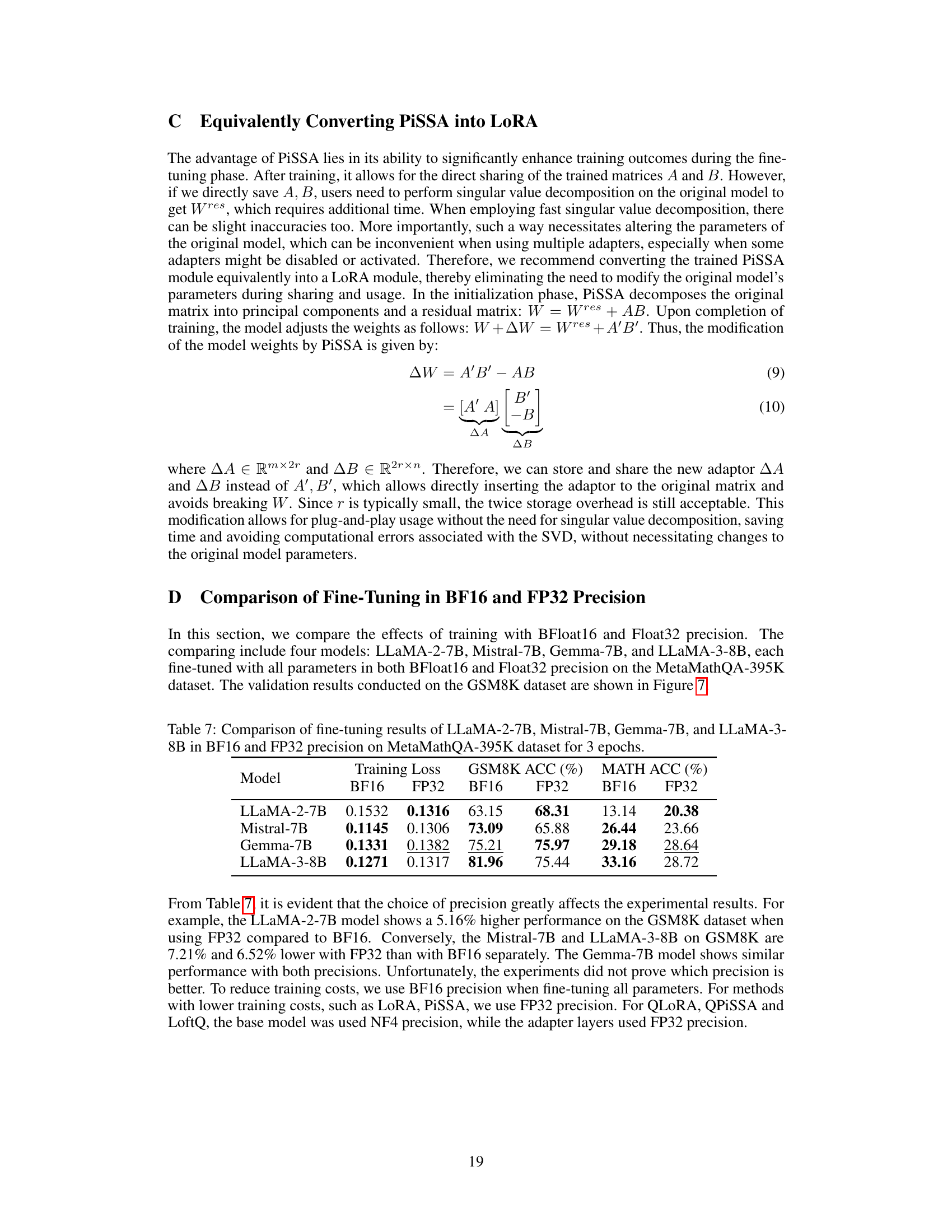

More visual insights#

More on figures

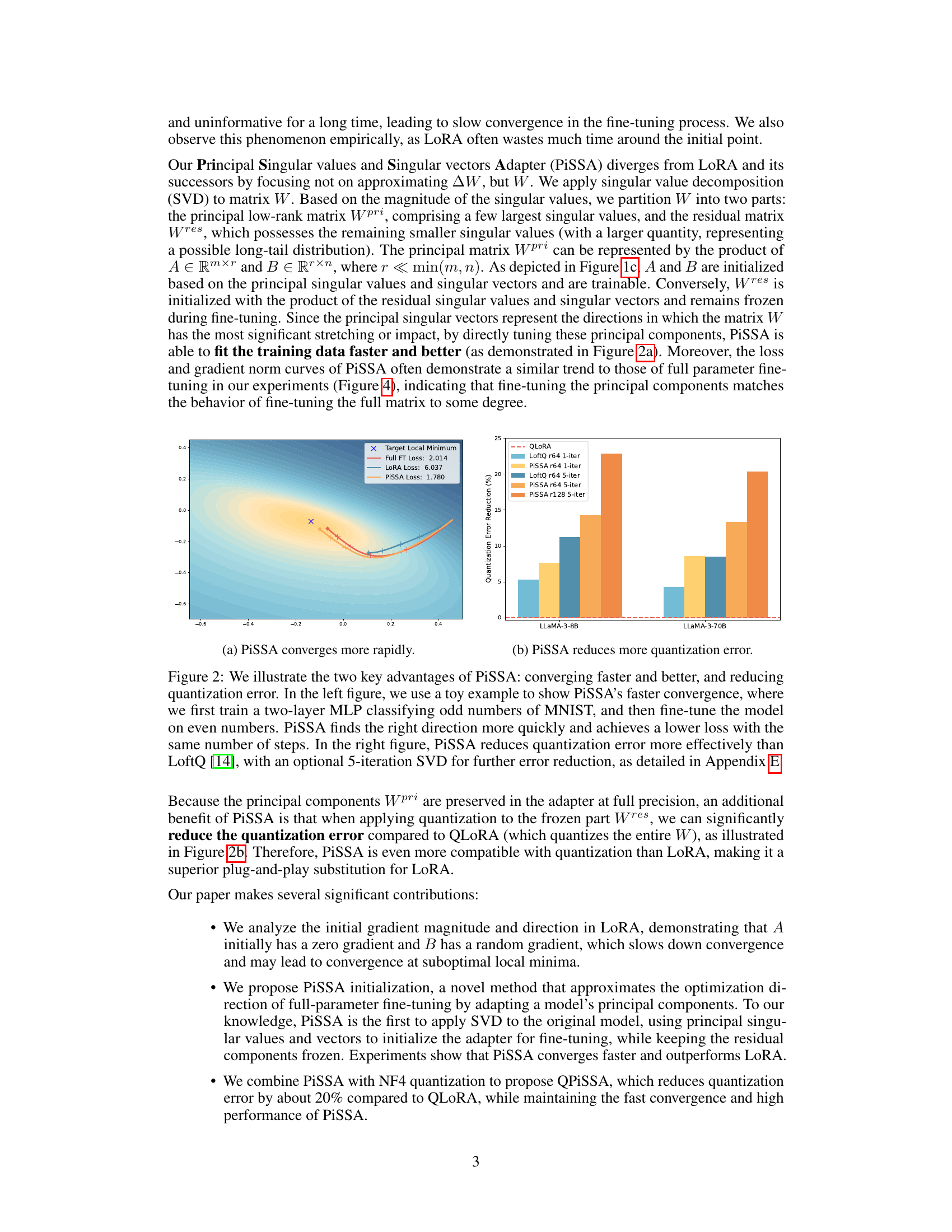

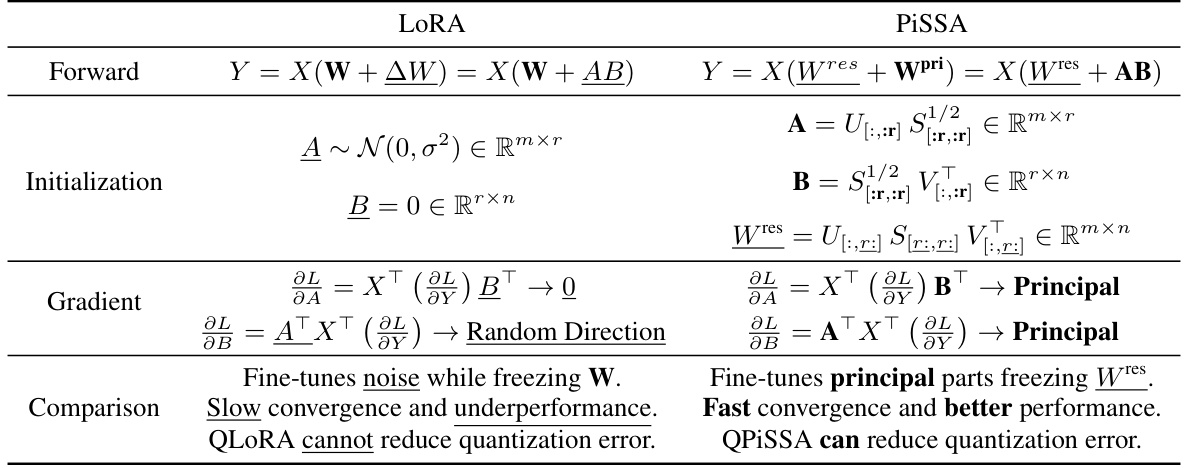

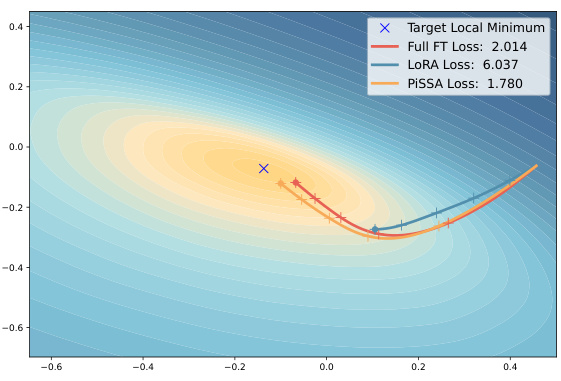

This figure demonstrates two key advantages of PiSSA over other methods. The left plot shows PiSSA’s faster convergence to a lower loss compared to LoRA in a toy example. The right plot illustrates that PiSSA reduces quantization errors significantly better than LoftQ, especially when combined with a 5-iteration SVD.

This figure demonstrates two main advantages of PiSSA over other methods. The left subplot shows PiSSA’s faster convergence speed by comparing the loss curves of PiSSA and LoRA in a simple classification task. The right subplot showcases PiSSA’s superior performance in reducing quantization error compared to LoftQ, especially when using a 5-iteration SVD.

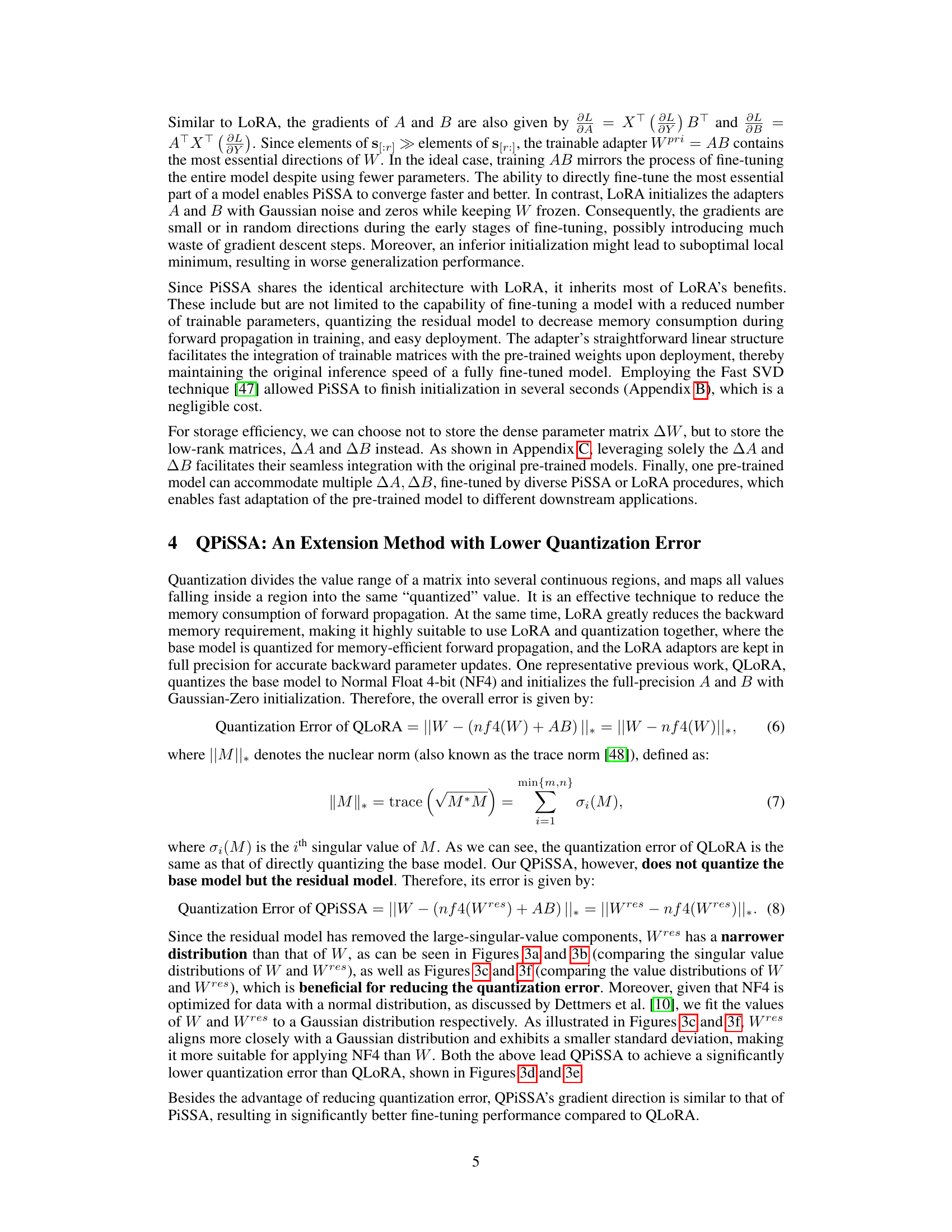

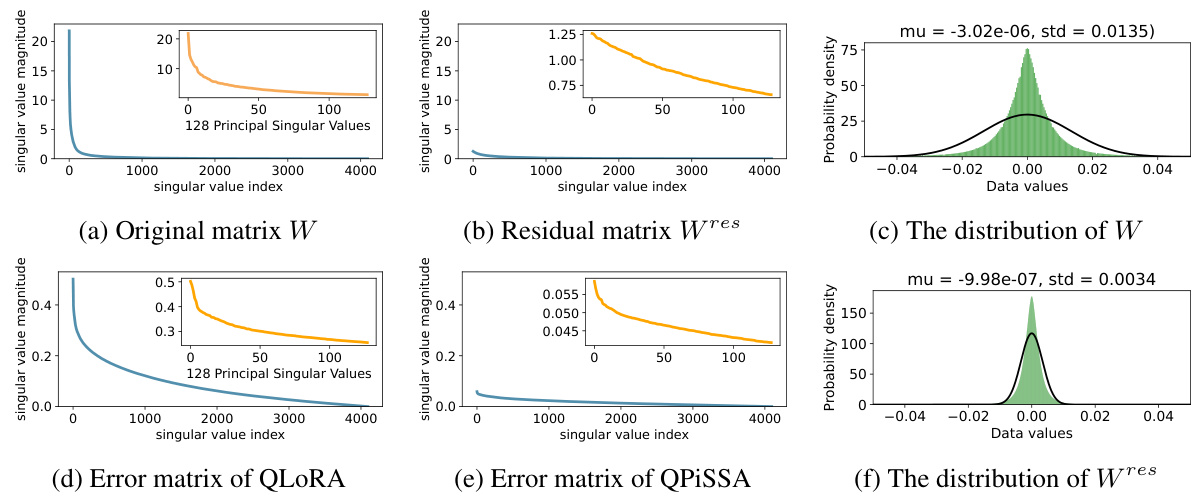

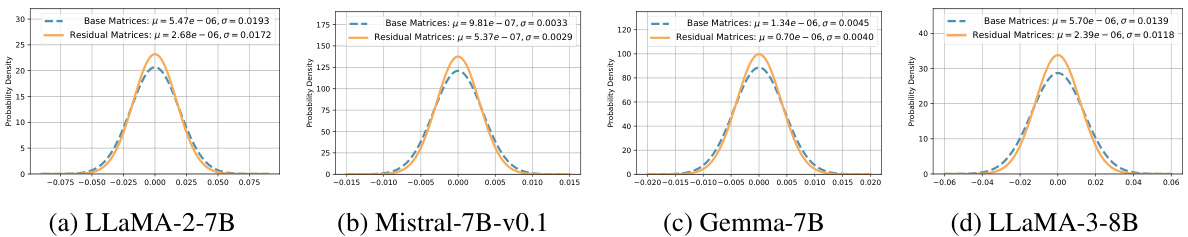

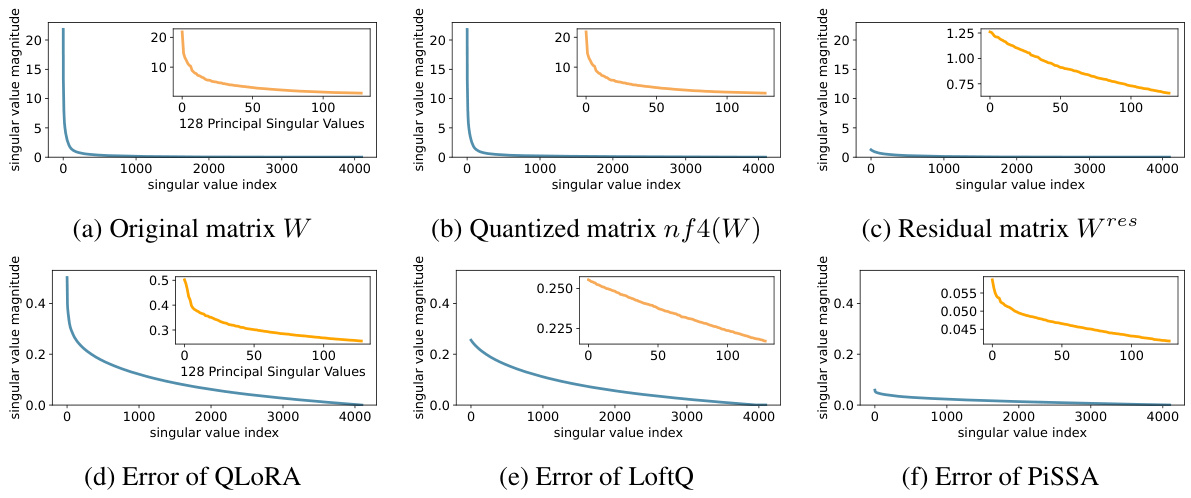

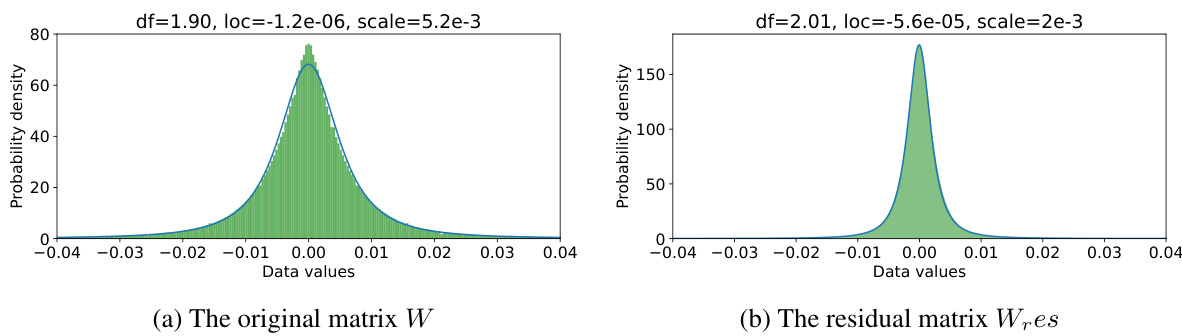

This figure visualizes the singular value decomposition of the query projection matrix (W) from the first self-attention layer of LLaMA 2-7B and its components after applying PiSSA. It shows the singular values of the original matrix (W), the residual matrix after PiSSA (Wres), the quantization error matrices for QLoRA and QPiSSA, and the data distributions for W and Wres. This visualization is used to illustrate the impact of PiSSA on reducing quantization error by demonstrating that the residual matrix (Wres) has a narrower distribution than the original matrix (W), making it more suitable for quantization.

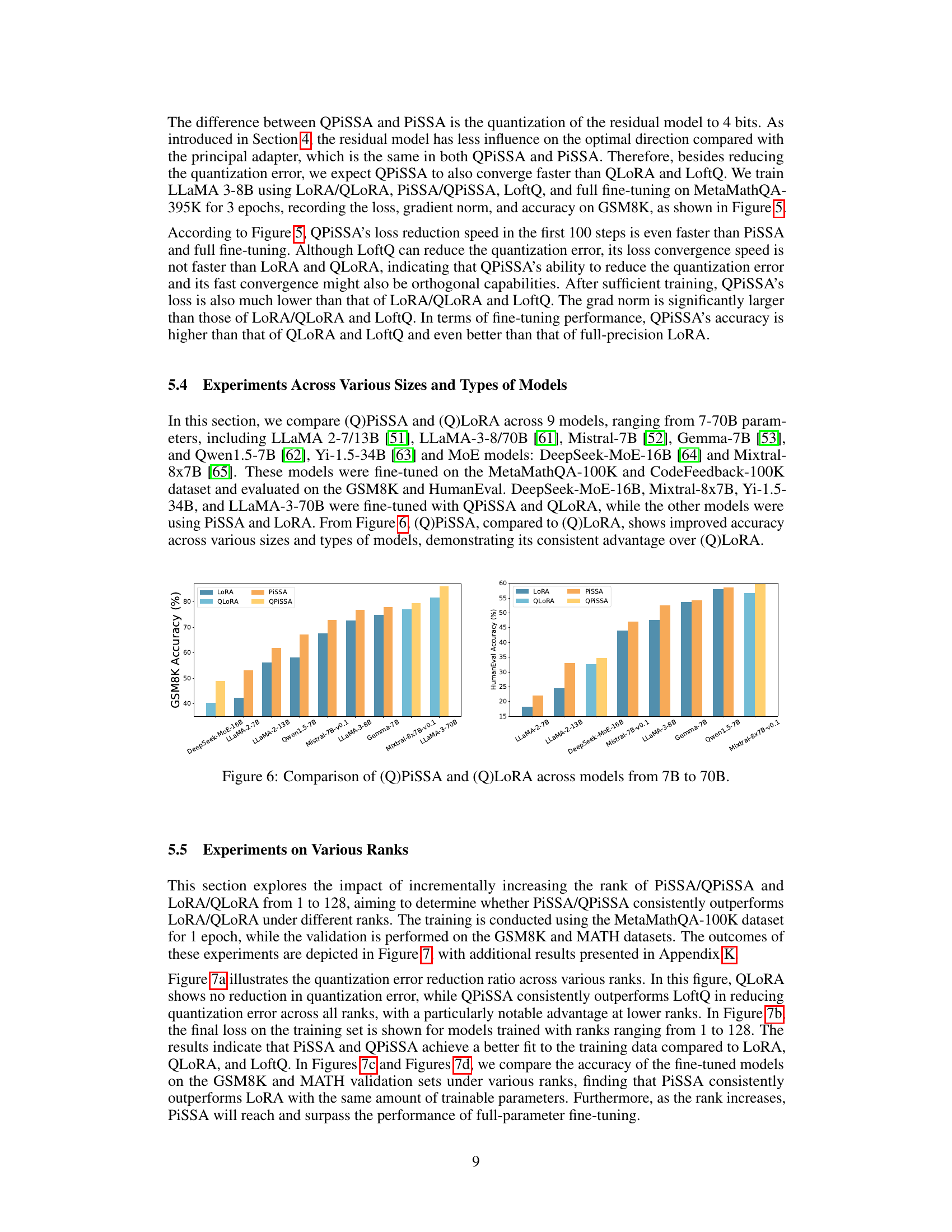

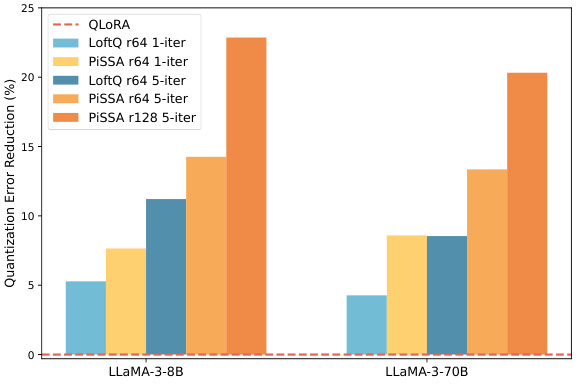

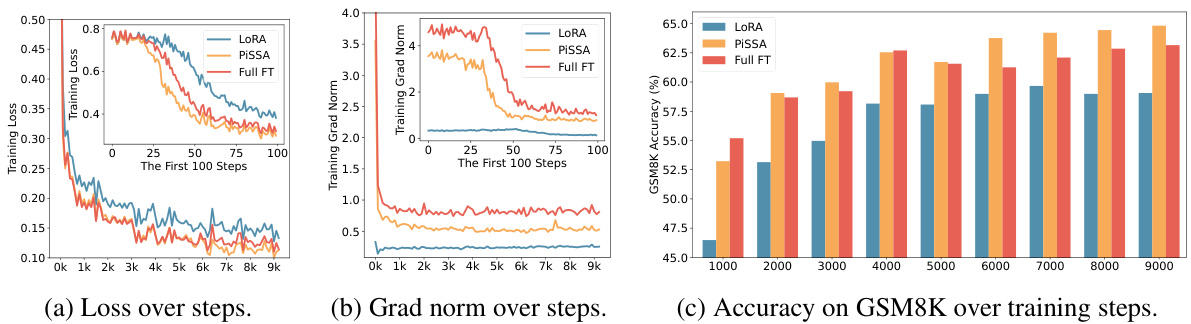

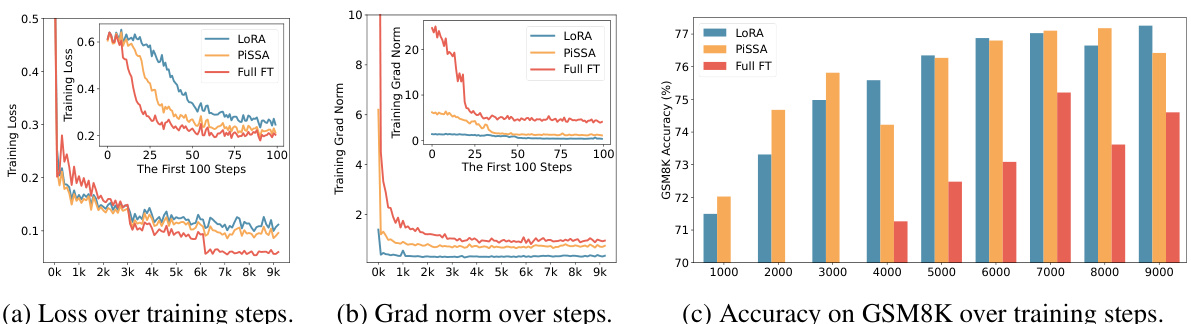

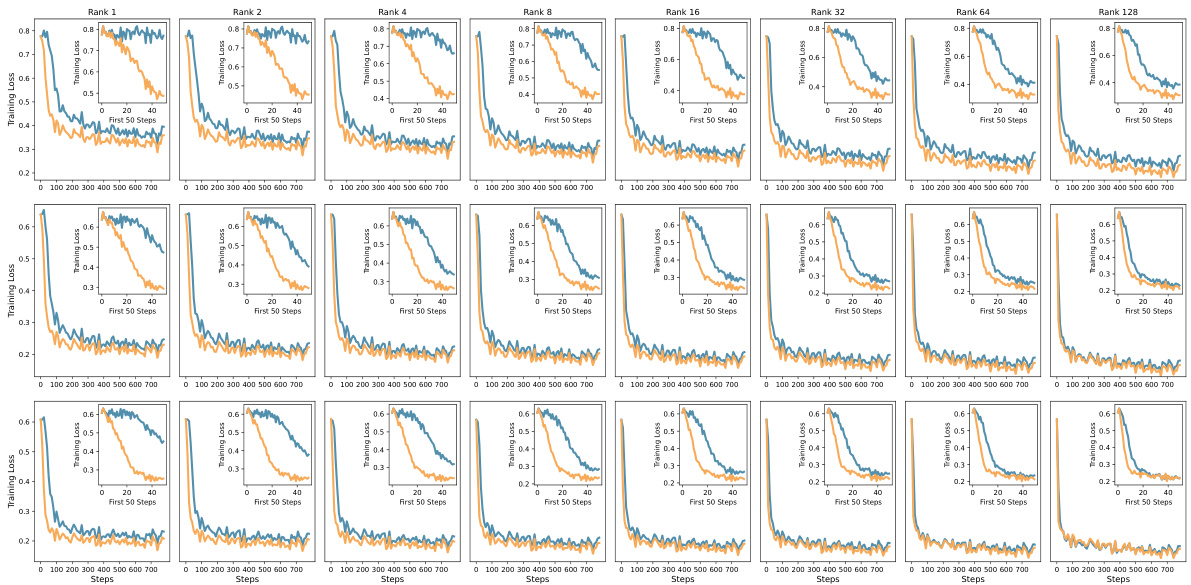

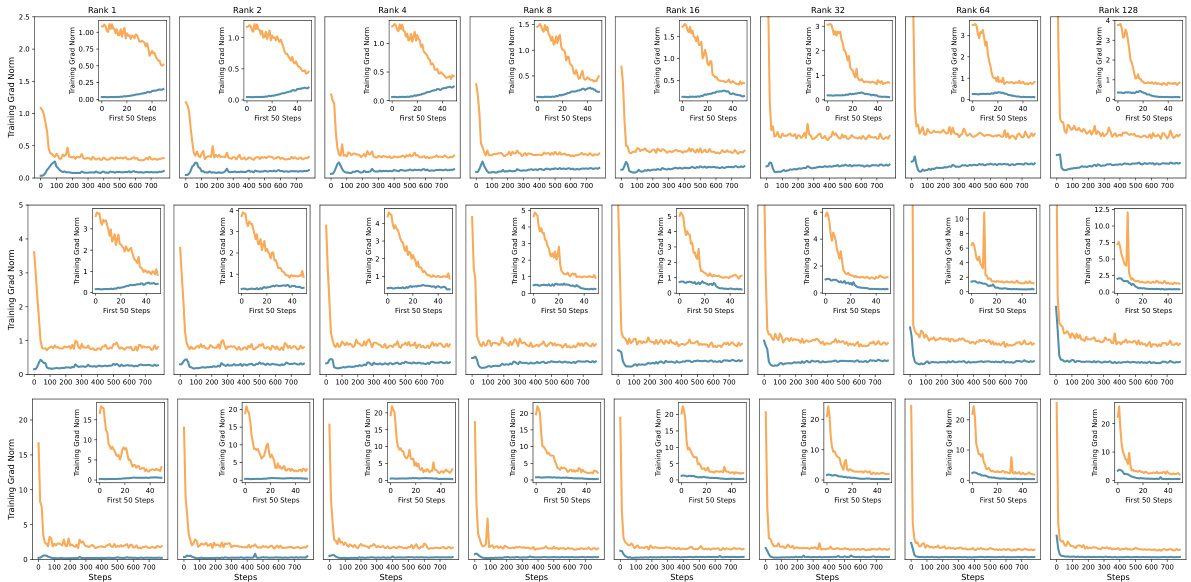

This figure compares the training performance of LoRA, PiSSA, and full fine-tuning methods. The plots show the training loss, gradient norm, and accuracy on the GSM8K benchmark over training steps. It visually demonstrates that PiSSA converges faster and achieves better accuracy compared to LoRA and is closer to the performance of full fine-tuning, which uses significantly more parameters.

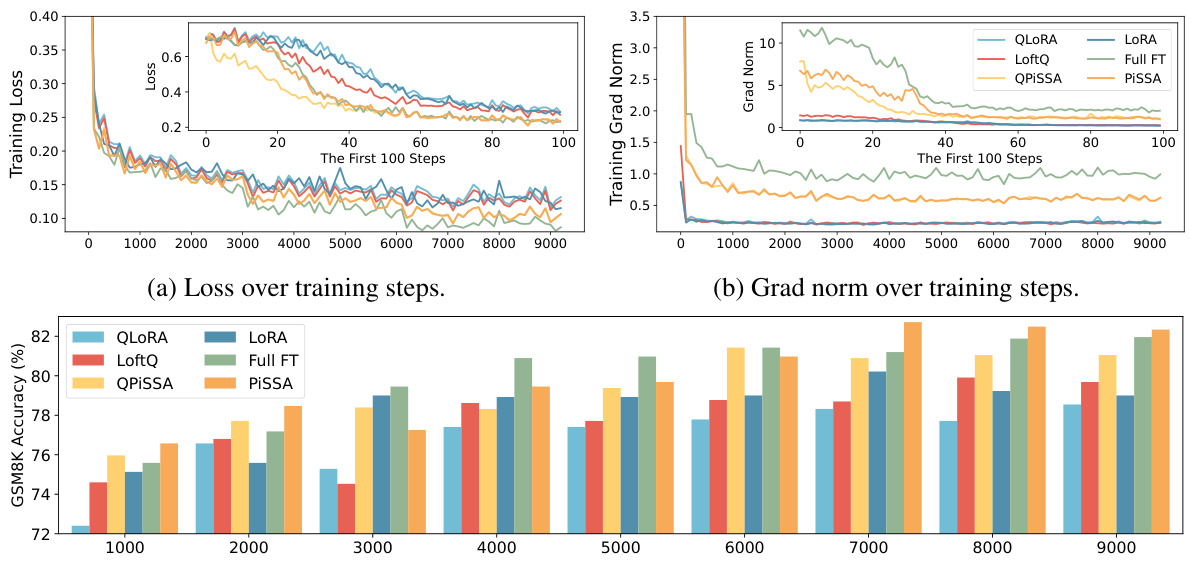

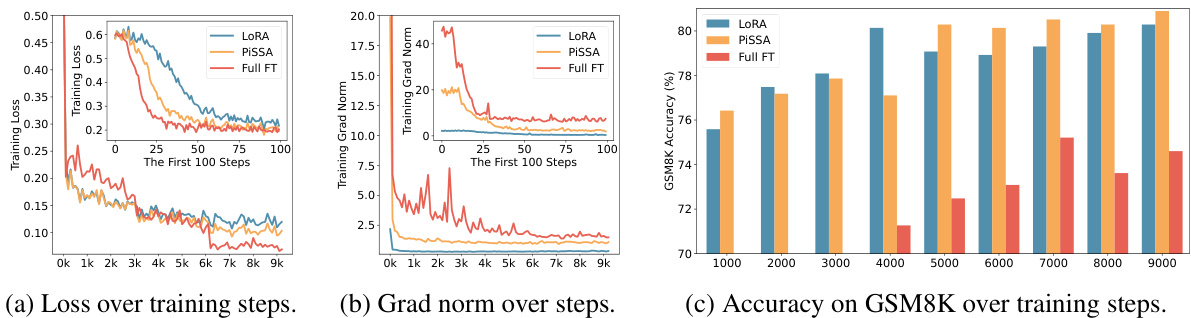

This figure compares the training performance of QLoRA, QPiSSA, LoftQ, and full fine-tuning methods across different metrics (loss, gradient norm, and GSM8K accuracy). The plots show how these different methods converge over training steps, highlighting the relative speed and performance of each approach. The comparison includes both quantized (Q) and unquantized versions to illustrate the impact of quantization on the fine-tuning process.

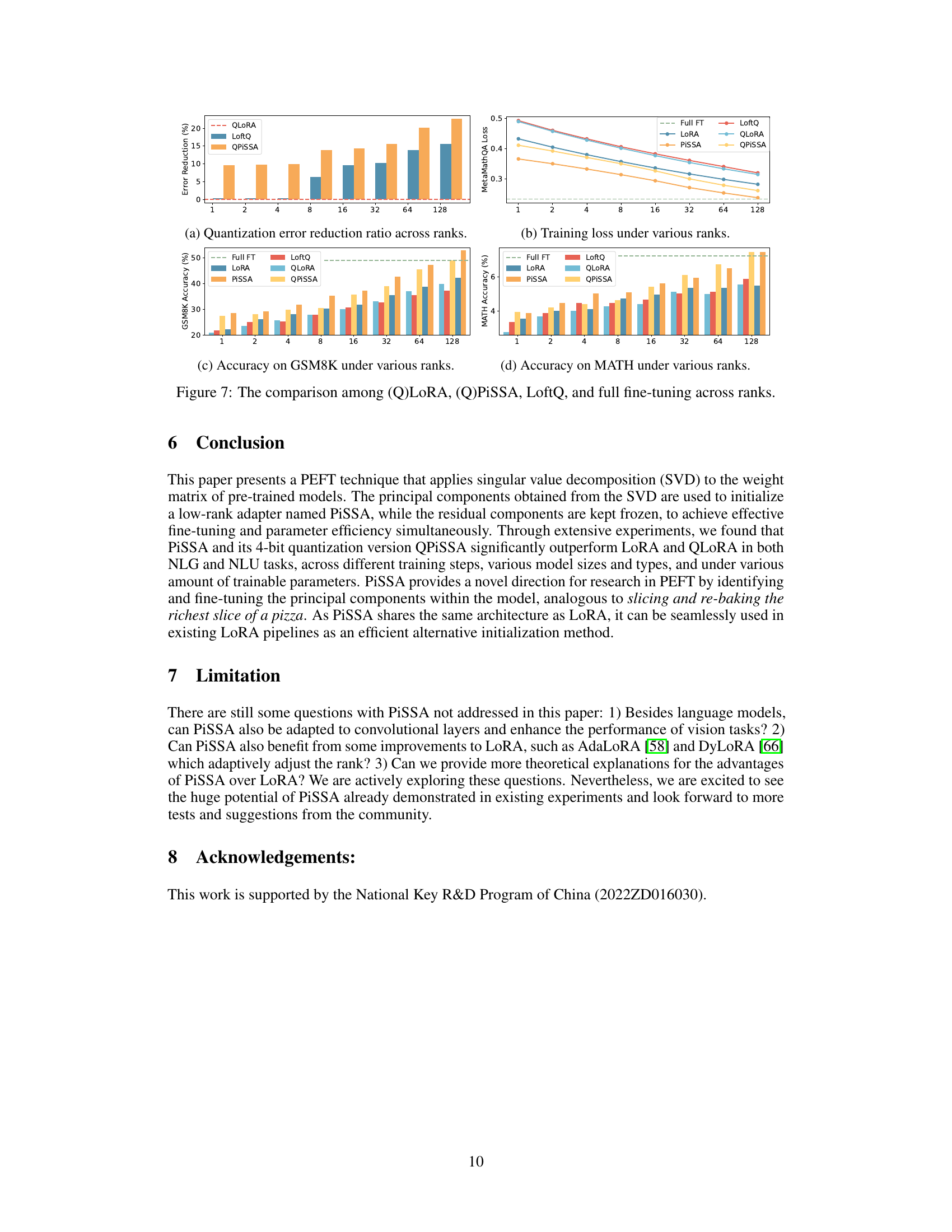

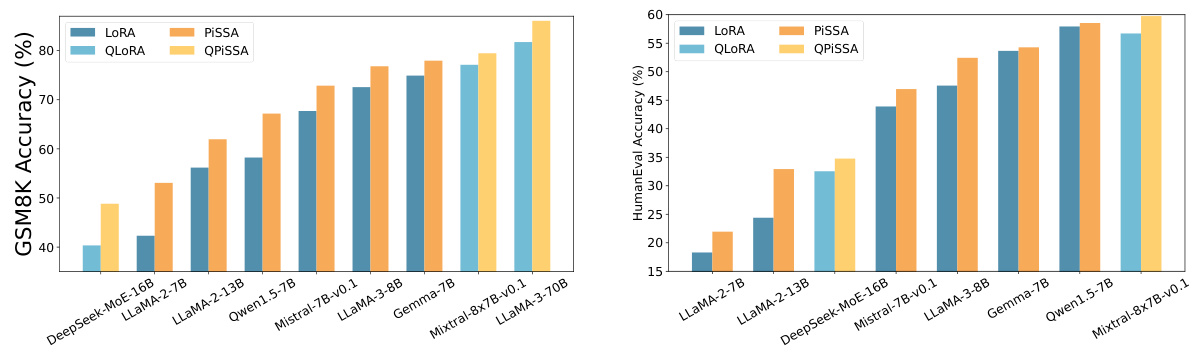

This figure compares the performance of PiSSA and LoRA, as well as their quantized versions QPiSSA and QLoRA, across nine different large language models ranging in size from 7 billion to 70 billion parameters. The models were fine-tuned on the MetaMathQA-100K and CodeFeedback-100K datasets and then evaluated on the GSM8K and HumanEval benchmarks. The bar chart visually represents the accuracy achieved by each method on each model. The results demonstrate a consistent advantage for PiSSA/QPiSSA across various model sizes and types.

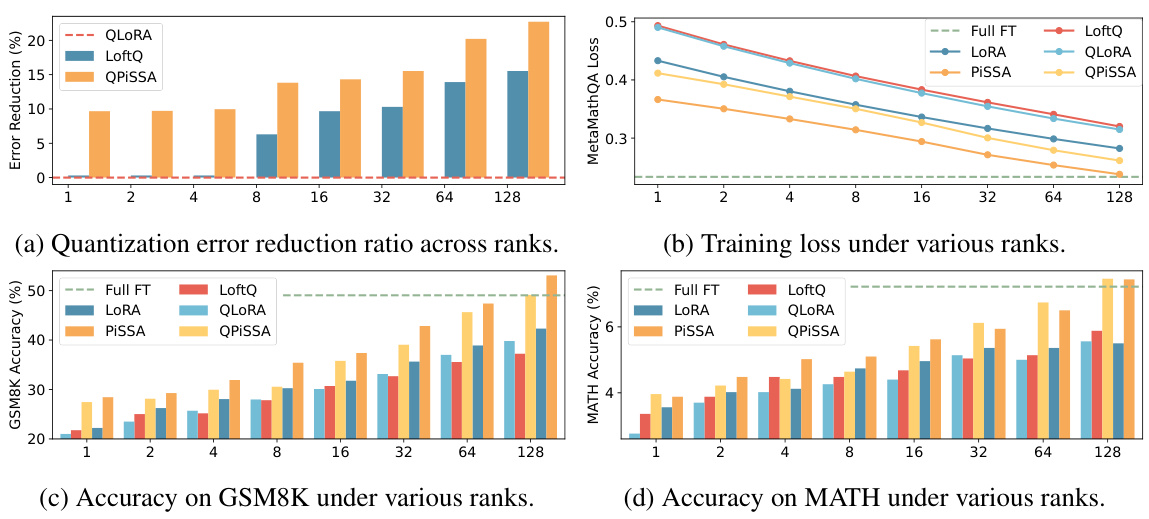

This figure compares the performance of QLoRA, QPiSSA, LoftQ, and full fine-tuning across different ranks. Subfigures (a) to (d) show the quantization error reduction ratio, training loss, GSM8K accuracy, and MATH accuracy respectively. The results show that PiSSA and QPiSSA generally outperform other methods, especially at lower ranks. However, at higher ranks, PiSSA’s performance might decrease slightly, suggesting potential over-parameterization.

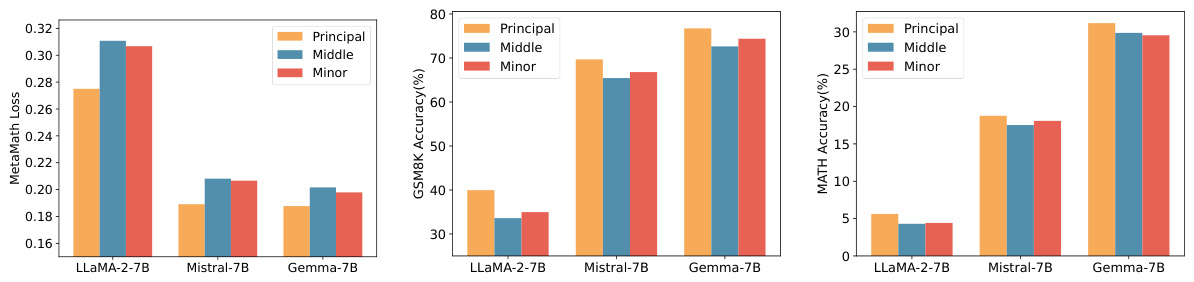

This figure shows the results of initializing the adapters in three different large language models (LLaMA-2-7B, Mistral-7B, Gemma-7B) with principal, middle and minor singular values and vectors. The results are evaluated on three different benchmarks: MetaMathQA (training loss), GSM8K (accuracy), and MATH (accuracy). It demonstrates that using principal singular values and vectors leads to the best performance across all three models.

This figure visualizes the singular value decomposition of the query projection matrix (W) from the first self-attention layer of the LLaMA 2-7B model and its decomposition into principal and residual components. It compares the singular value distributions of the original matrix (W), the residual matrix (Wres), and the quantization errors using QLORA and QPISSA methods. The figure shows that QPiSSA results in a smaller quantization error because the residual matrix (Wres) has a narrower distribution.

This figure visualizes the singular value decompositions and data distributions of different matrices related to the LLaMA 2-7B model’s self-attention query projection layer. It compares the original weight matrix (W), its quantized version (nf4(W)), the residual matrix after applying PiSSA (Wres), and the resulting error matrices for QLoRA and QPiSSA, providing a visual demonstration of how PiSSA reduces quantization errors by focusing on the principal singular values and vectors.

This figure visualizes the singular value decompositions of the original weight matrix (W) and the residual matrix (Wres) from a LLaMA 2-7B model’s self-attention layer. It also shows the distribution of values for these matrices and the quantization errors from QLORA and QPISSA methods. The figure shows that the residual matrix has a narrower value distribution than the original matrix and exhibits a smaller quantization error when using PiSSA.

This figure compares the training performance of LoRA, PiSSA, and full fine-tuning methods over training steps. Three subplots are shown: training loss, gradient norm, and accuracy on the GSM8K benchmark. PiSSA demonstrates faster convergence and higher accuracy than LoRA, while full fine-tuning shows signs of overfitting due to its use of many more trainable parameters.

This figure shows a comparison of the training loss, gradient norm, and accuracy on the GSM8K benchmark across three different fine-tuning methods: LoRA, PiSSA, and full fine-tuning. It illustrates that PiSSA converges faster and achieves a lower loss compared to LoRA, while maintaining performance comparable to full fine-tuning. The gradient norm for PiSSA shows a trend similar to full fine-tuning, unlike the behavior of LoRA which starts with near-zero gradient and slowly increases, suggesting that PiSSA is more effectively utilizing the gradient information during training.

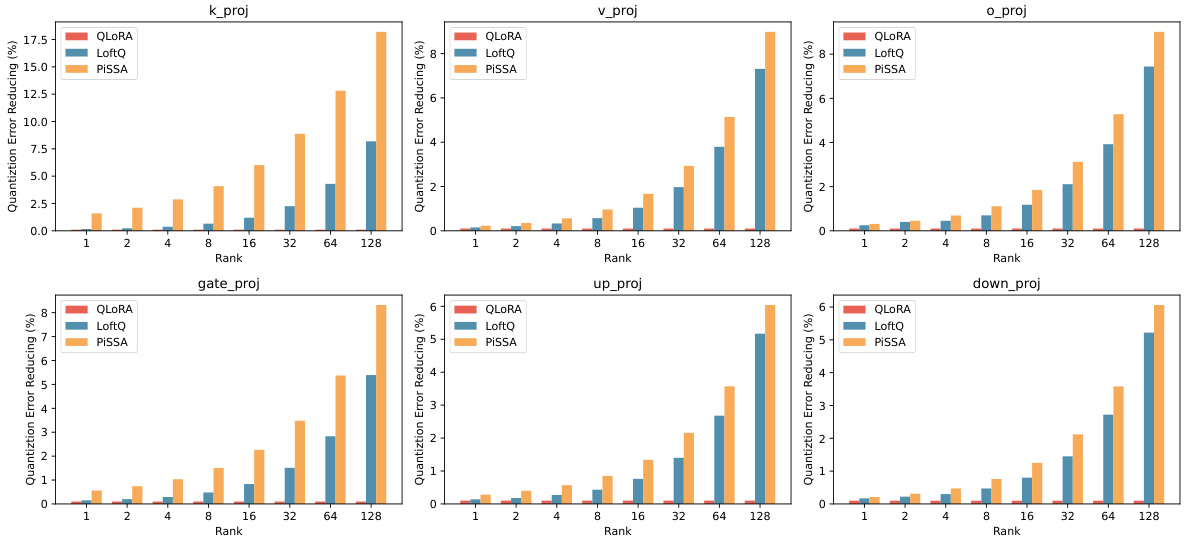

This figure compares the quantization error reduction ratios achieved by QLoRA, LoftQ, and PiSSA across different types of linear layers within a transformer model. It displays the error reduction for six different types of layers (‘k_proj’, ‘v_proj’, ‘o_proj’, ‘gate_proj’, ‘up_proj’, and ‘down_proj’) at varying ranks (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128). The results visually show PiSSA’s superior performance in reducing quantization error compared to QLoRA and LoftQ across all layer types and ranks.

This figure visualizes the singular values and data distributions of the original weight matrix (W), the residual matrix (Wres), and the quantization errors for LLaMA 2-7B’s self-attention query projection layer. It highlights the narrower distribution and reduced magnitude of singular values in the residual matrix Wres after applying singular value decomposition, which is a key component of the PiSSA method. The reduced magnitude explains why quantizing Wres (QPiSSA) leads to lower quantization errors than quantizing the full matrix W (QLoRA).

This figure compares the performance of four different fine-tuning methods—(Q)LoRA, (Q)PiSSA, LoftQ, and full fine-tuning—across various ranks. The four subfigures show the quantization error reduction ratio, training loss, GSM8K accuracy, and MATH accuracy, respectively, for each method and rank. The results illustrate the performance advantages of PiSSA and QPiSSA, especially at lower ranks, and demonstrate their ability to match or exceed the performance of full fine-tuning in certain scenarios.

This figure compares the performance of QLoRA, QPiSSA, LoftQ, and full fine-tuning across different ranks. It visualizes the quantization error reduction ratio, the training loss, and the accuracy on GSM8K and MATH datasets. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of PiSSA and QPiSSA in reducing quantization error and achieving higher accuracy compared to other methods, especially at lower ranks.

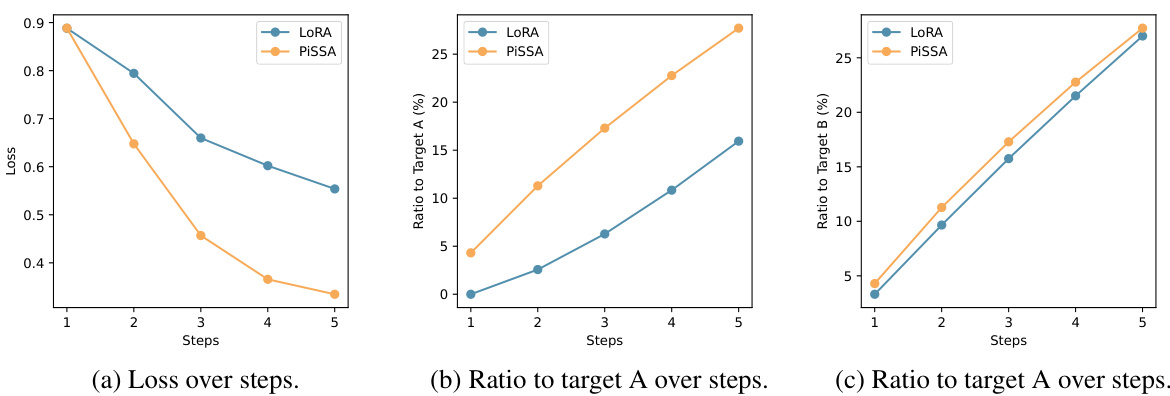

This figure compares the performance of LoRA and PiSSA over the first five training steps. The leftmost panel shows the training loss for each method. The remaining panels show the progress towards the final parameter values for matrices A and B (after 50 steps) as a percentage of the total distance from the initial parameter values. PiSSA demonstrates faster convergence towards the target parameters.

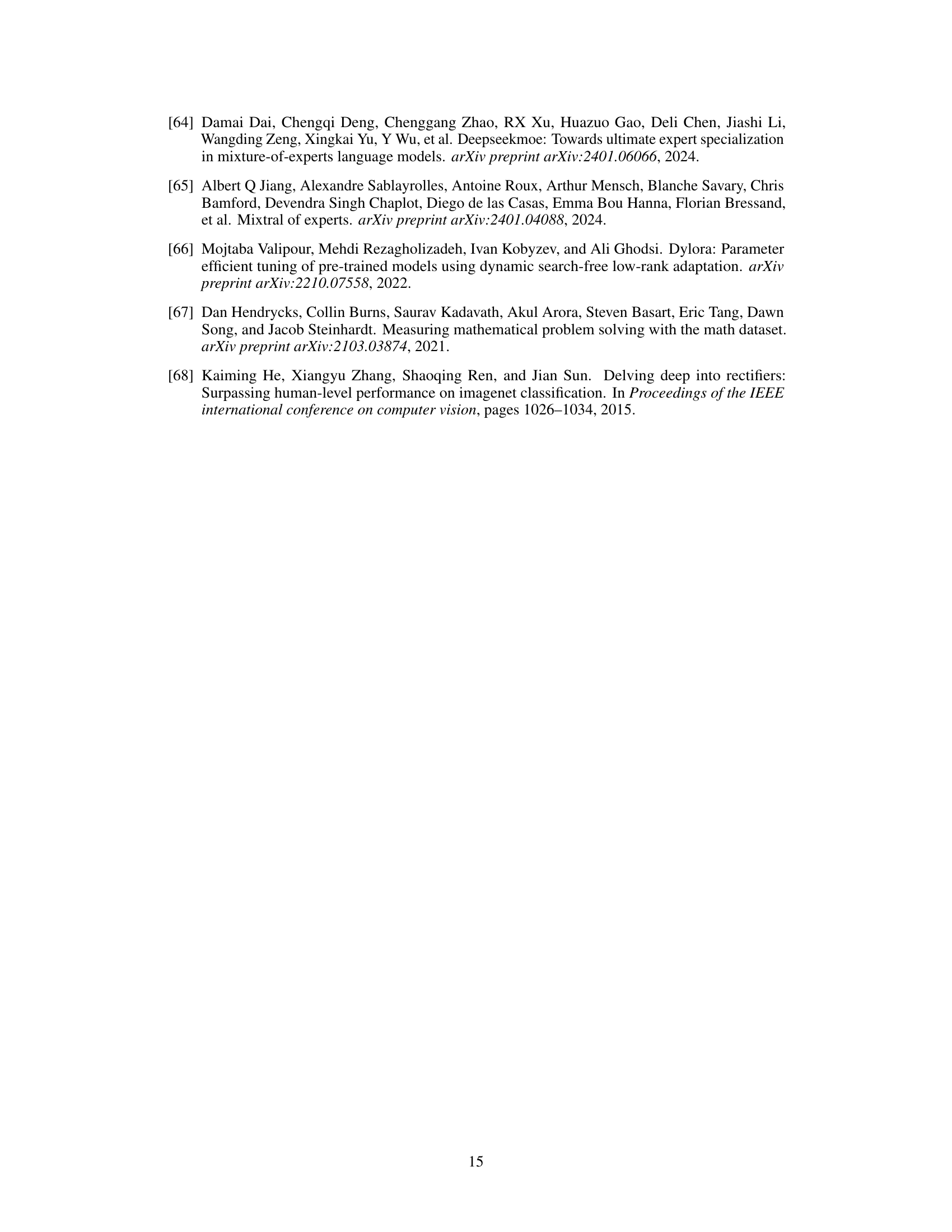

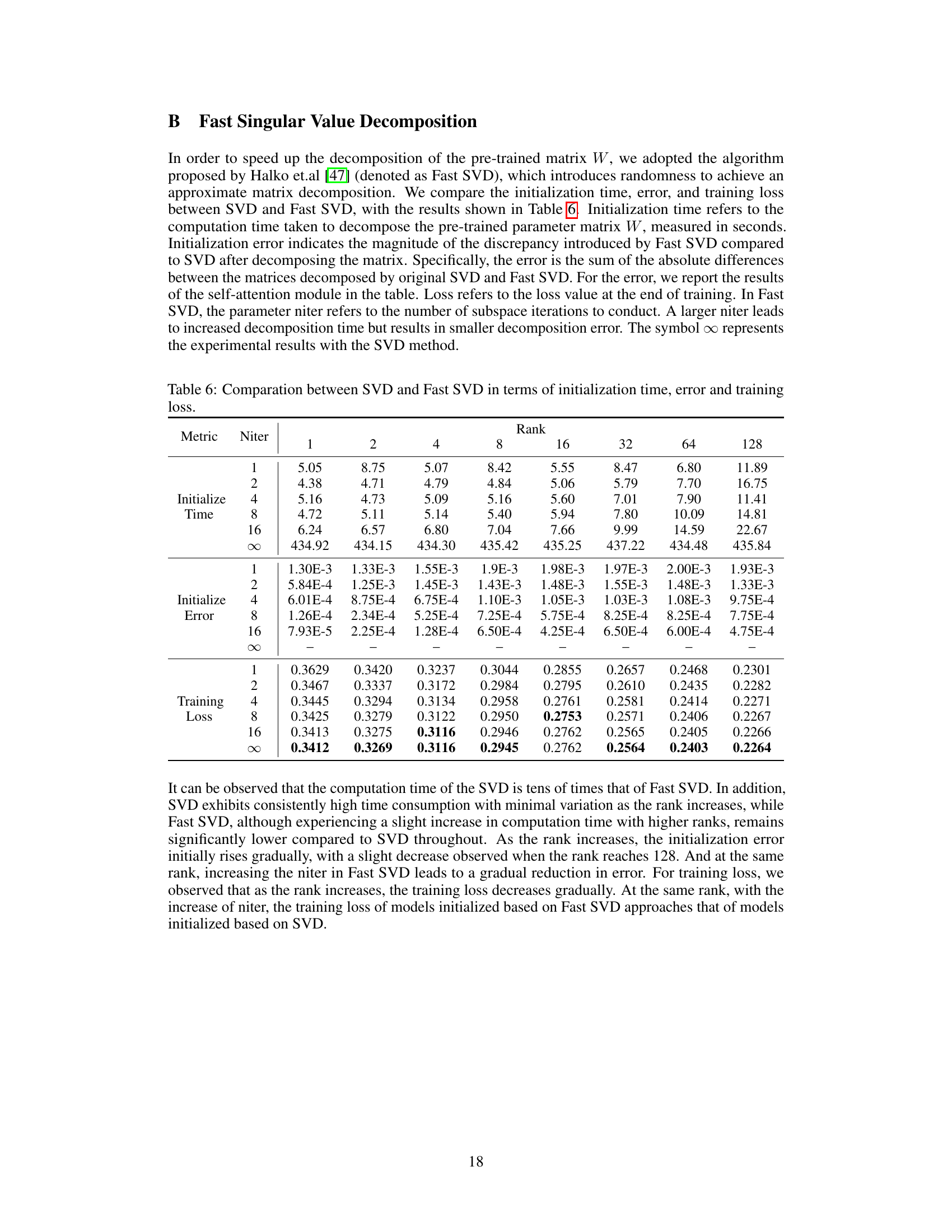

More on tables

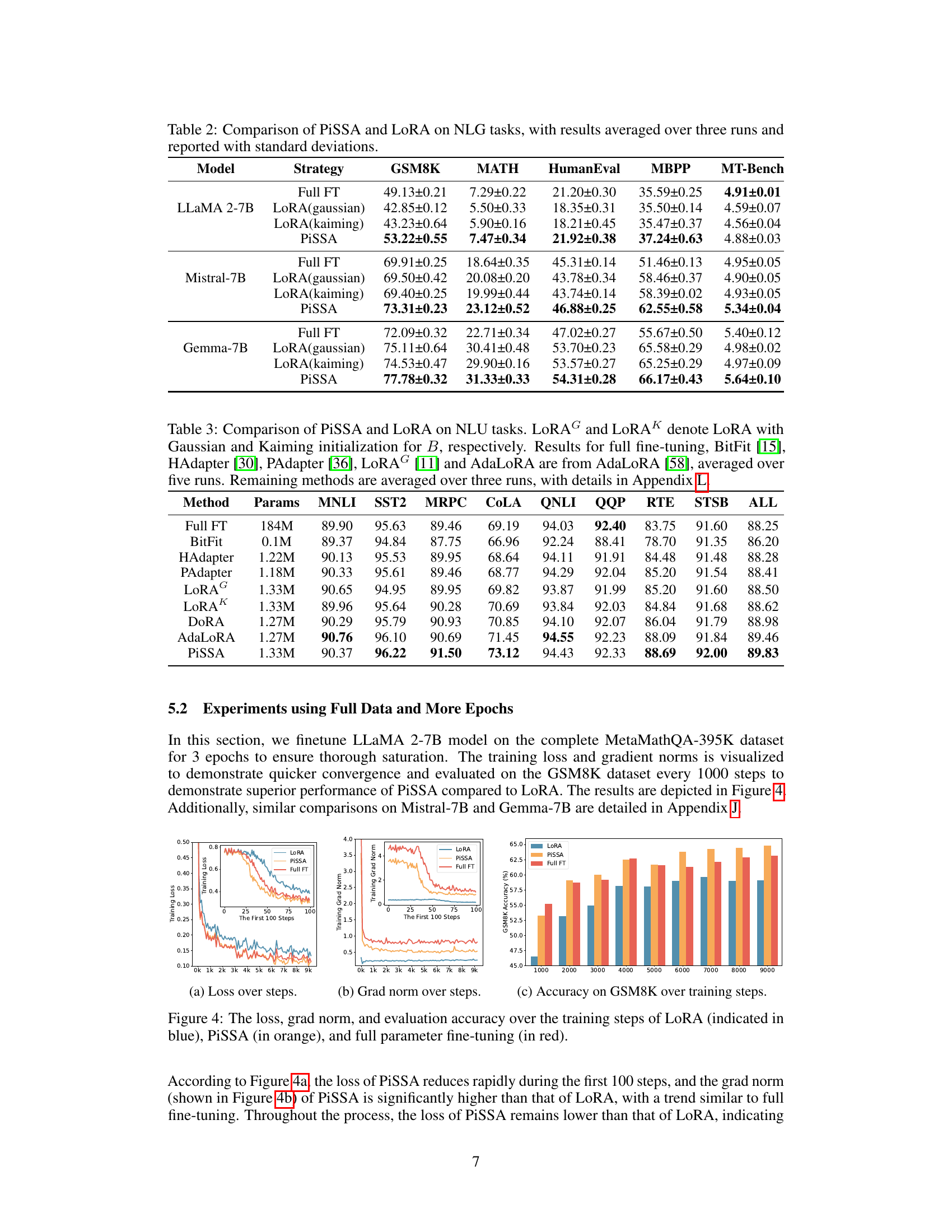

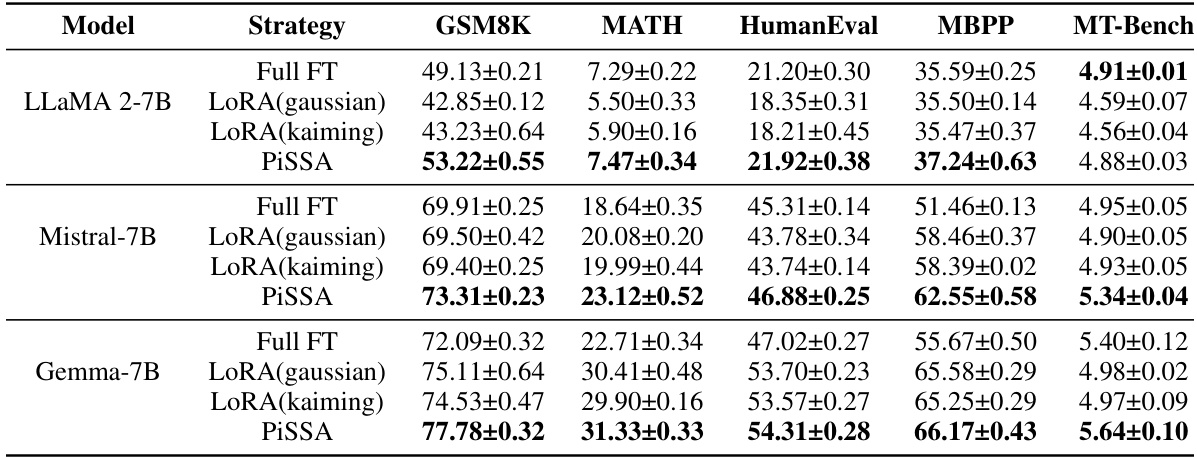

This table presents a comparison of the performance of PiSSA and LoRA on various natural language generation (NLG) tasks. Three different large language models (LLaMA-2-7B, Mistral-7B, and Gemma-7B) were fine-tuned using both methods, and the results (averaged over three runs) are reported with standard deviations for each task. The tasks include GSM8K, MATH, HumanEval, MBPP, and MT-Bench, providing a comprehensive evaluation across different benchmarks and model types.

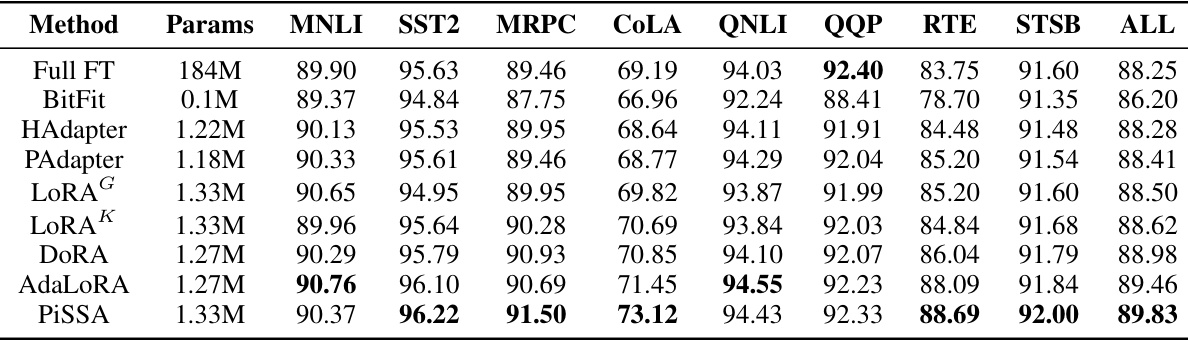

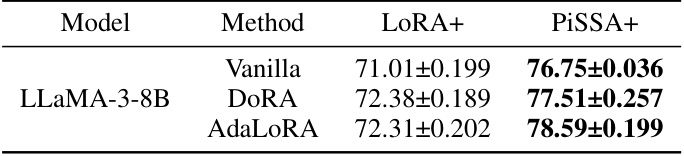

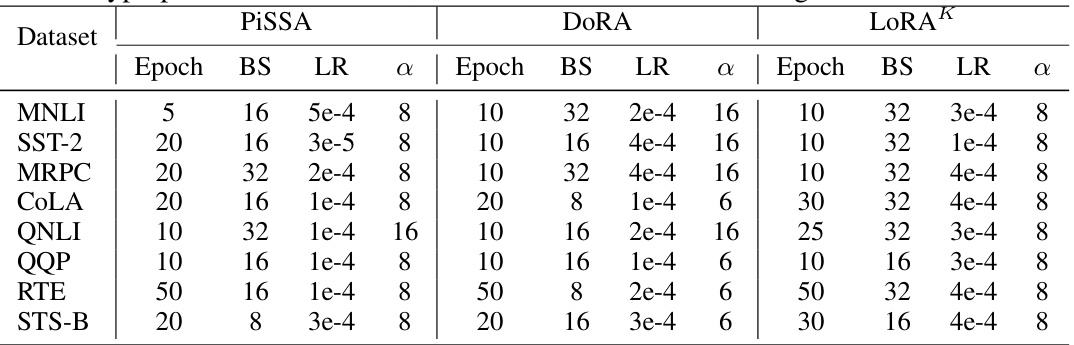

This table compares the performance of PiSSA and LoRA on eleven natural language understanding (NLU) tasks using the GLUE benchmark. It shows the accuracy achieved by various methods, including full fine-tuning, BitFit, HAdapter, PAdapter, LoRA (with Gaussian and Kaiming initialization), DORA, and AdaLoRA. The table highlights PiSSA’s consistent performance improvement compared to LoRA across different tasks. Details about the experimental setup and statistical analysis can be found in Appendix L.

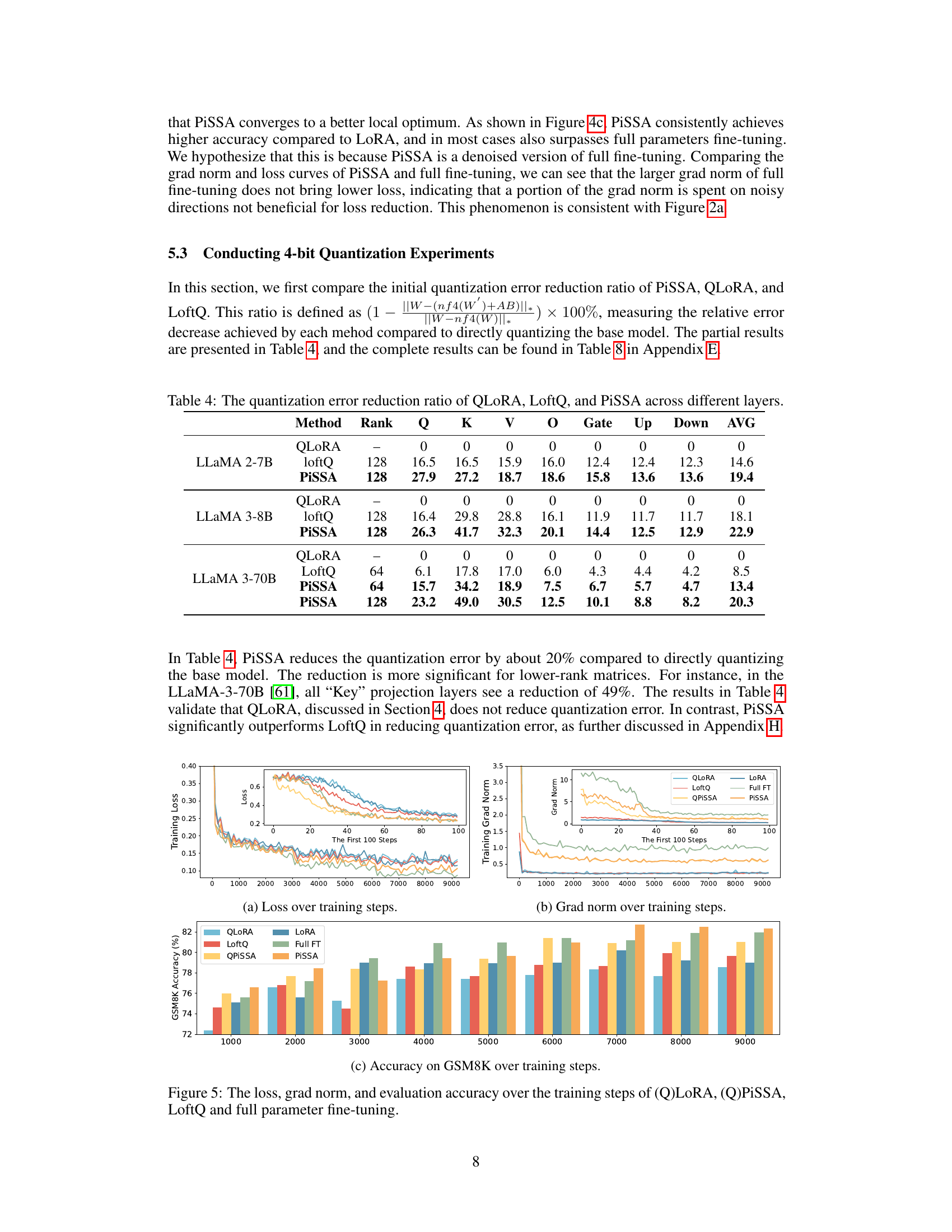

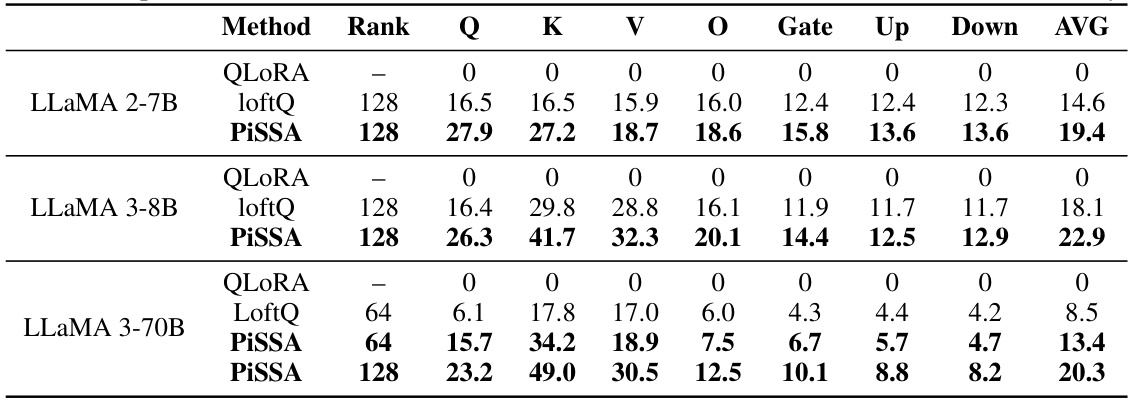

This table compares the quantization error reduction ratios achieved by three different methods (QLoRA, LoftQ, and PiSSA) across various layers of different language models. The error reduction ratio is calculated as (1 - ||W-(nf4(W)+AB)||) × 100%, where ||.|| denotes the nuclear norm. A higher ratio signifies a greater reduction in quantization error, indicating a more effective method. The table shows that PiSSA consistently outperforms the other two methods across different model sizes and various layers, demonstrating its advantage in reducing quantization error.

This table compares the performance of different methods on the GSM8K benchmark. It shows the accuracy achieved by the vanilla LORA and PiSSA models, and also the accuracy when these models are enhanced with three LoRA improvement methods (DORA, AdaLoRA). The results demonstrate that PiSSA consistently outperforms LORA, and that incorporating LoRA improvements further enhances the performance of both methods.

This table compares the performance of PiSSA and LoRA on eleven natural language understanding (NLU) tasks from the GLUE benchmark. It shows the accuracy of different models (including various parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods) for each task and their overall performance. The results highlight the consistent improvement of PiSSA over LoRA across the NLU tasks.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of PiSSA and LoRA on several Natural Language Generation (NLG) tasks. The models were evaluated on various metrics such as GSM8K, MATH, HumanEval, MBPP and MT-Bench across four different models: LLaMA 2-7B, Mistral-7B, Gemma-7B. The results are averages of three runs and include standard deviations to show variability. The table highlights the consistent superior performance of PiSSA compared to LoRA.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of PiSSA and LoRA on various Natural Language Generation (NLG) tasks. The results are averaged over three runs and include standard deviations to indicate the variability in the results. The table shows that PiSSA consistently outperforms LoRA across a variety of models and tasks, highlighting the effectiveness of PiSSA as a parameter-efficient fine-tuning method.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of PiSSA and LoRA on various Natural Language Generation (NLG) tasks. It shows the accuracy achieved by full fine-tuning, LoRA with Gaussian initialization, LoRA with Kaiming initialization, and PiSSA across multiple models (LLaMA-2-7B, Mistral-7B, Gemma-7B) and several NLG benchmarks (GSM8K, MATH, HumanEval, MBPP, MT-Bench). Standard deviations are included to show the variability in the results.

This table compares the performance of PiSSA and LoRA on eleven different natural language understanding (NLU) tasks. It shows various model parameters, the results for each model on each task (with metrics like accuracy), and indicates the methods used for initialization. Results from five runs for full fine-tuning, BitFit, HAdapter, PAdapter, LoRAG and AdaLoRA are included, while PiSSA and LoRA results are based on three runs. Details about these results can be found in Appendix L. The table highlights the differences in performance between PiSSA and LoRA and other state-of-the-art models.

This table compares the performance of PiSSA and LoRA on eleven different natural language understanding (NLU) tasks using the GLUE benchmark. It shows the accuracy achieved by various methods, including full fine-tuning, BitFit, HAdapter, PAdapter, LoRA (with Gaussian and Kaiming initialization), AdaLoRA, and PiSSA. The table highlights the performance gains achieved by PiSSA compared to other methods, demonstrating its effectiveness in NLU tasks. The table also shows the model parameters used and includes references to relevant papers and appendices for more detail.

Full paper#