↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current LLM ensembling methods struggle with heterogeneity and vocabulary mismatches, hindering the effective collaboration of diverse models. Existing approaches often involve training extra components, which can limit their generalization capabilities. This paper presents a new challenge in improving the current ensemble methods.

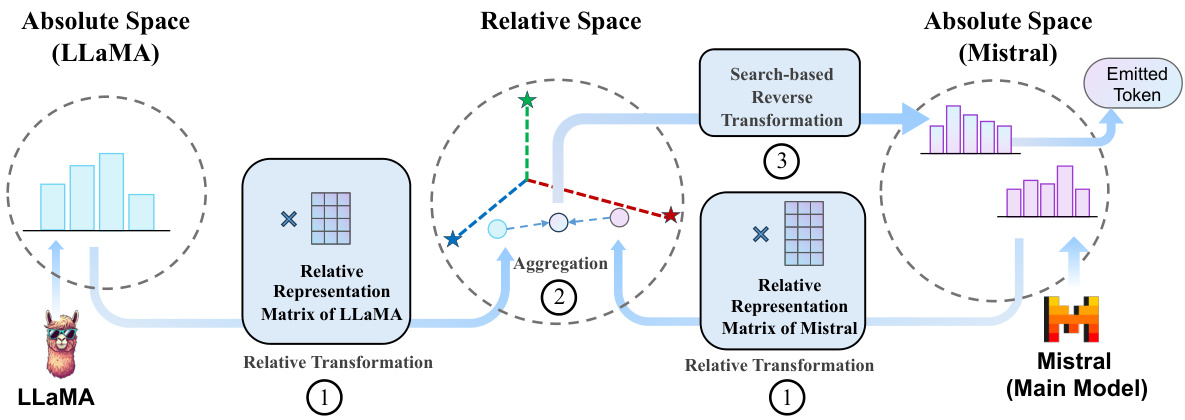

The proposed method, DEEPEN, addresses these challenges by leveraging relative representation theory. This innovative approach maps the probability distributions from each LLM into a shared ‘relative’ space, enabling seamless aggregation and a search-based inverse transformation back to the probability space of a single LLM. DEEPEN’s training-free nature and consistent performance improvements across various benchmarks highlight its practical value and potential for enhancing LLM capabilities.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel, training-free ensemble framework for large language models (LLMs). It addresses the crucial challenge of combining heterogeneous LLMs with mismatched vocabularies, a common issue limiting progress in LLM ensembling. The proposed method, DEEPEN, uses relative representation theory to achieve consistent performance improvements across diverse benchmarks. This opens exciting new avenues for research in LLM fusion techniques and model collaboration. Its training-free nature enhances the generalizability and practicality of the approach, making it readily applicable in real-world settings.

Visual Insights#

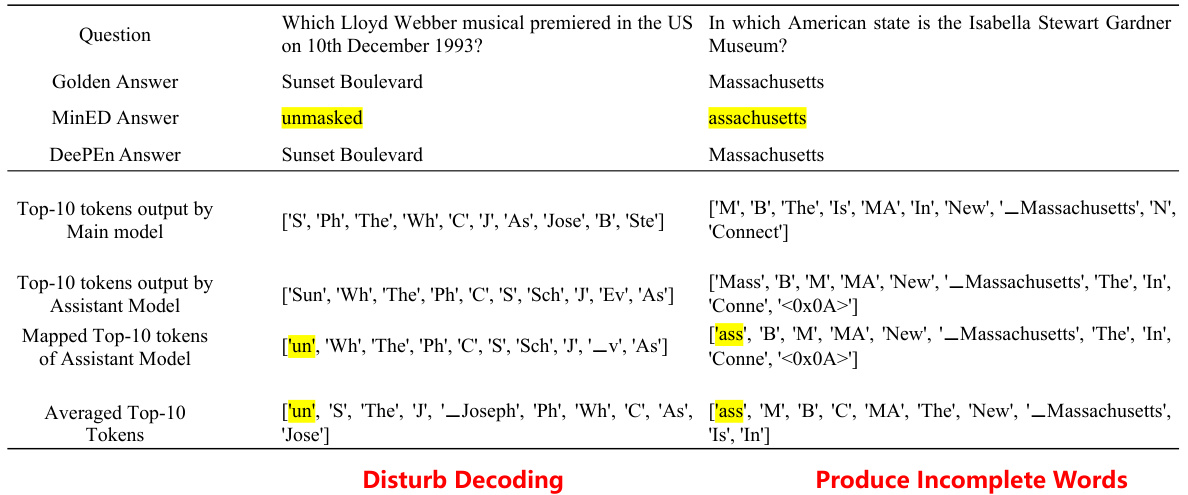

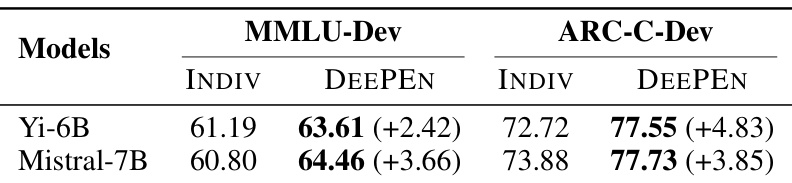

This figure visualizes the relative representations of word embeddings from three different language models: LLaMA2-7B, LLaMA2-13B, and Mistral-7B. LLaMA2-7B and LLaMA2-13B share the same vocabulary, while Mistral-7B has a different vocabulary. PCA and K-means clustering are used for visualization. The plots show that relative representations (based on cosine similarity to anchor tokens) are largely consistent across models with the same vocabulary, indicating cross-model invariance, even when model architectures or sizes differ. The red block highlights tokens unique to Mistral’s vocabulary, which still shows some alignment in the relative space, although consistency is lower compared to the models sharing vocabularies.

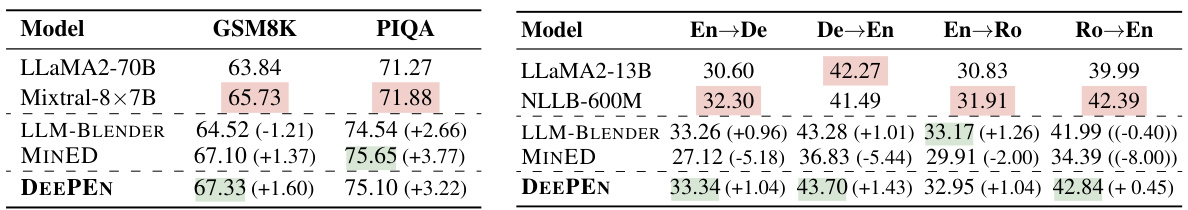

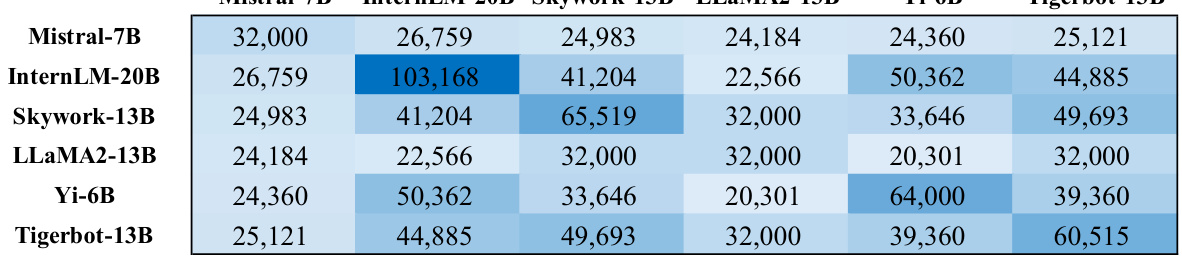

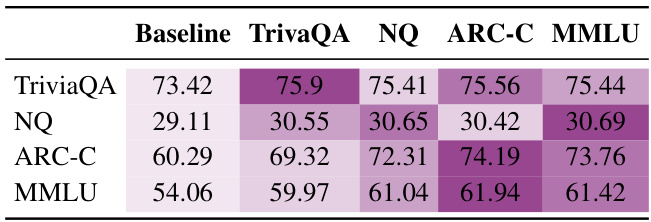

This table presents the main results of the experiments comparing different ensemble methods (LLM-BLENDER, MINED, DEEPEN-Avg, DEEPEN-Adapt, VOTING, MBR) on six benchmark datasets, categorized into comprehensive examination, reasoning capabilities and knowledge capacities. It shows the performance of individual models and different ensemble methods. The best performing individual model and the best performing ensemble method are highlighted. The table also demonstrates the effectiveness of combining different ensemble methods, particularly VOTING/MBR with DEEPEN.

In-depth insights#

Relative Rep Fusion#

Relative representation fusion, a core concept in the paper, offers a novel approach to ensemble learning for heterogeneous large language models (LLMs). Instead of directly averaging probability distributions, which is infeasible due to vocabulary mismatches, this method leverages the cross-model invariance of relative representations. This invariance, meaning the similarity between token embeddings remains consistent across models regardless of their vocabulary, is crucial for enabling fusion. Each LLM’s probability distribution is first transformed into a universal relative space. This transformation uses a matrix built from the relative representations of all tokens, effectively aligning disparate probability spaces. Aggregation occurs in this shared space, simplifying the process and avoiding the complexities of token misalignment. Finally, a search-based inverse transformation maps the fused relative representation back to the probability space of a chosen main LLM, ready to generate the next token. This framework is training-free, enhancing generalization, and uses rich internal model information beyond simple textual outputs, representing a significant improvement over prior LLM ensemble approaches.

Deep Parallelism#

Deep parallelism, in the context of large language models (LLMs), likely refers to techniques that exploit parallelism at multiple levels. One level would involve the parallel processing of different LLMs within an ensemble, allowing for simultaneous predictions from diverse model architectures. This contrasts with sequential methods, significantly reducing inference time. Another layer of deep parallelism might concern intra-model parallelism. LLMs themselves are massively parallel systems; optimizing how their internal computations are parallelized across hardware (e.g., GPUs) is crucial for efficiency. Therefore, ‘deep parallelism’ suggests a holistic approach, combining inter-model and intra-model parallel processing. This would lead to faster and more robust inference, leveraging the combined strengths of multiple LLMs in a highly efficient manner. The challenges of deep parallelism include efficient communication and synchronization overhead between the parallel components, and optimal distribution of tasks to balance computational load effectively. The potential benefits are substantial, suggesting future research directions in this field will be critical for scaling LLMs to handle even more complex tasks.

Cross-Model Invariance#

The concept of ‘Cross-Model Invariance’ is crucial in ensemble learning, especially when dealing with heterogeneous models. It suggests that despite variations in model architectures or training data, certain fundamental relationships or patterns remain consistent across different models. This invariance is typically observed in the semantic space of the models, meaning that similar inputs or concepts yield similar representations regardless of the specific model used. This phenomenon is incredibly valuable because it allows for the aggregation of predictions or knowledge from multiple, diverse models without requiring extensive cross-model alignment or adaptation. By leveraging cross-model invariance, ensemble methods can efficiently combine the strengths of individual models while mitigating their weaknesses. However, identifying and exploiting these invariant features is challenging, often requiring careful selection of appropriate representation techniques or transformation methods that map heterogeneous model spaces onto a shared, consistent representation space. The success of such methods hinges on the accuracy and reliability of identifying these invariant relationships, as failures can lead to performance degradation or inconsistent results. For example, in the context of language models, a robust cross-model invariant representation should capture the core semantic meaning of words or phrases irrespective of the specific vocabulary or embedding used by the model. This allows effective averaging or fusion of probability distributions generated by different models to improve overall predictive accuracy and robustness.

Ensemble Limits#

The heading ‘Ensemble Limits’ prompts a rich discussion on the inherent boundaries of ensemble methods in the context of large language models (LLMs). While ensembling LLMs offers the potential for improved performance by combining diverse strengths, it’s crucial to acknowledge the limitations. One key limit is the computational cost; combining multiple LLMs significantly increases resource requirements, potentially outweighing performance gains. The effectiveness of ensembling is highly dependent on the diversity of the base models; similar LLMs yield marginal improvements. Another limitation revolves around generalization; while ensembles excel on seen data distributions, their performance on unseen data may not always improve, potentially even degrading. Finally, the complexity of managing and coordinating multiple LLMs introduces challenges. Effective ensemble methods must efficiently manage information flow and model interactions, which is a non-trivial task and further hindered by the lack of transparency in the internal workings of many LLMs. Therefore, understanding and addressing ensemble limits is paramount for the responsible and efficient application of LLMs in real-world scenarios.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Improving the efficiency of the inverse transformation in DEEPEN is crucial. The current search-based approach, while effective, introduces latency. Developing faster, more efficient methods, perhaps using learned mappings or approximations, would significantly enhance the framework’s practical applicability. Additionally, investigating alternative aggregation strategies beyond simple averaging in relative space warrants attention. More sophisticated techniques like weighted averaging based on model performance or uncertainty estimations could yield improved accuracy. The impact of different anchor word selections should be further examined. A more principled approach to anchor selection, potentially incorporating techniques from representation learning, could lead to more robust and reliable relative embeddings. Finally, applying DEEPEN to a broader range of tasks and model architectures, beyond those evaluated in the paper, would strengthen its generalizability and demonstrate its potential as a truly versatile LLM ensemble method.

More visual insights#

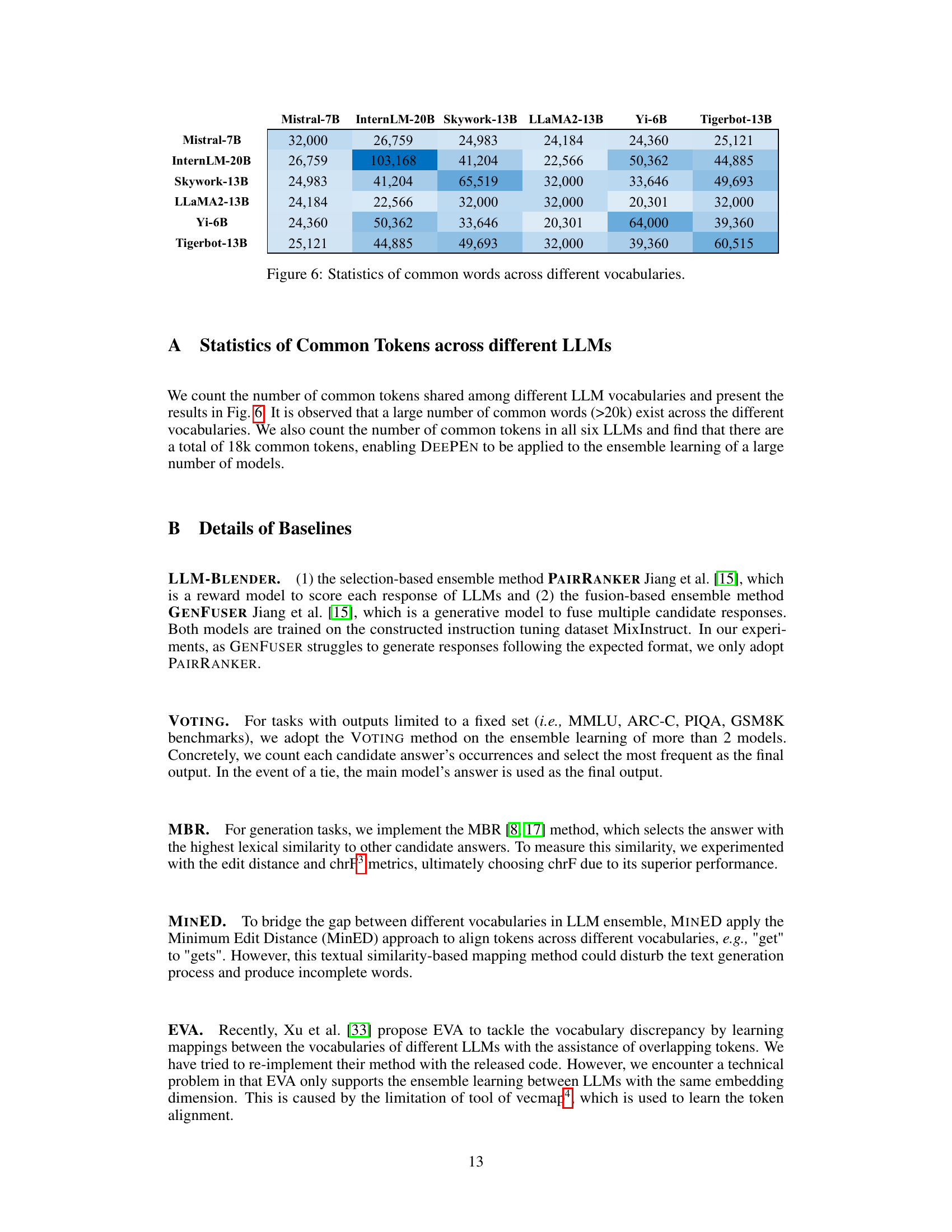

More on figures

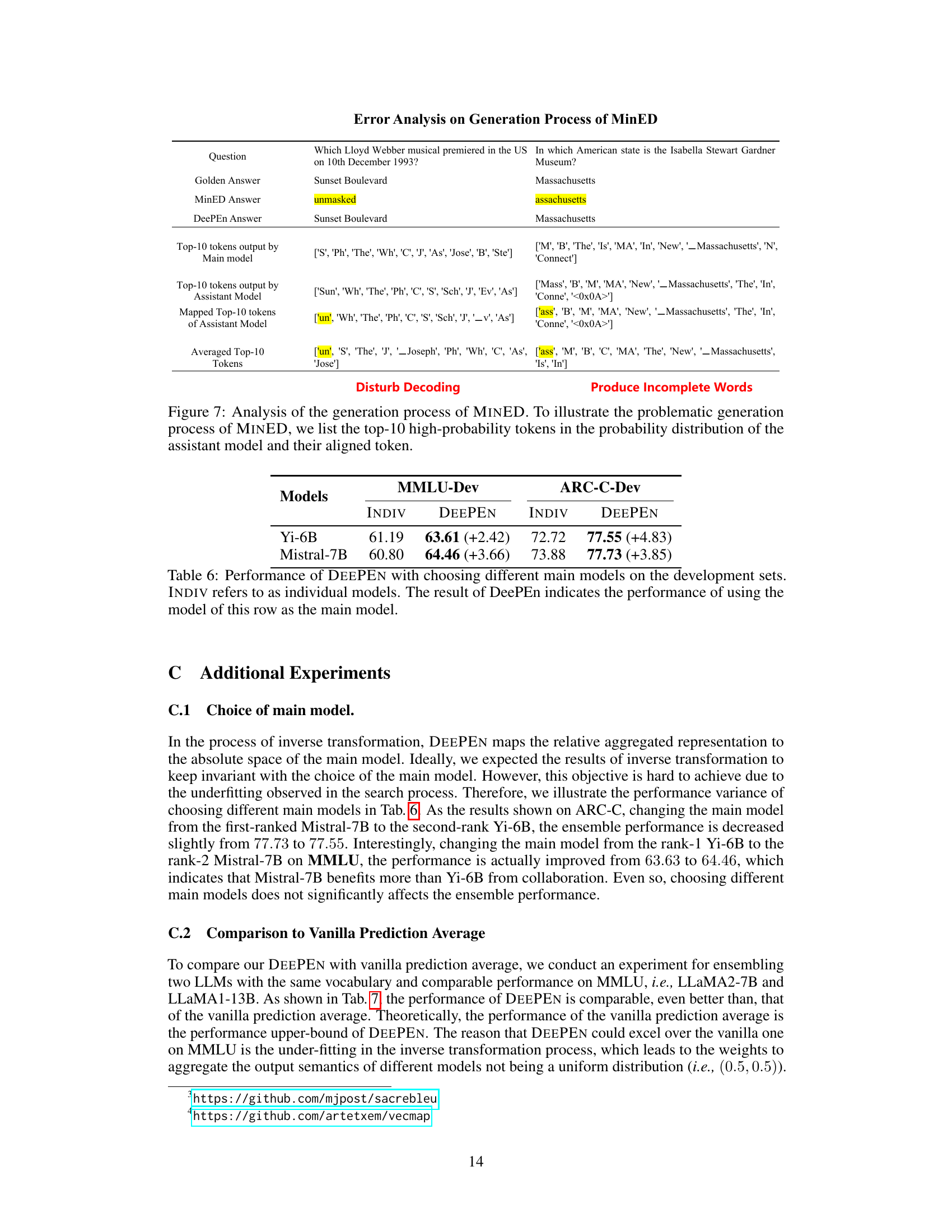

This figure illustrates the DEEPEN framework’s process. First, each LLM transforms its probability distribution from its own absolute space (vocabulary) to a shared relative space using its relative representation matrix. These relative representations are aggregated. Finally, a search-based inverse transformation maps the result back to the probability space of the selected main model, which produces the next token.

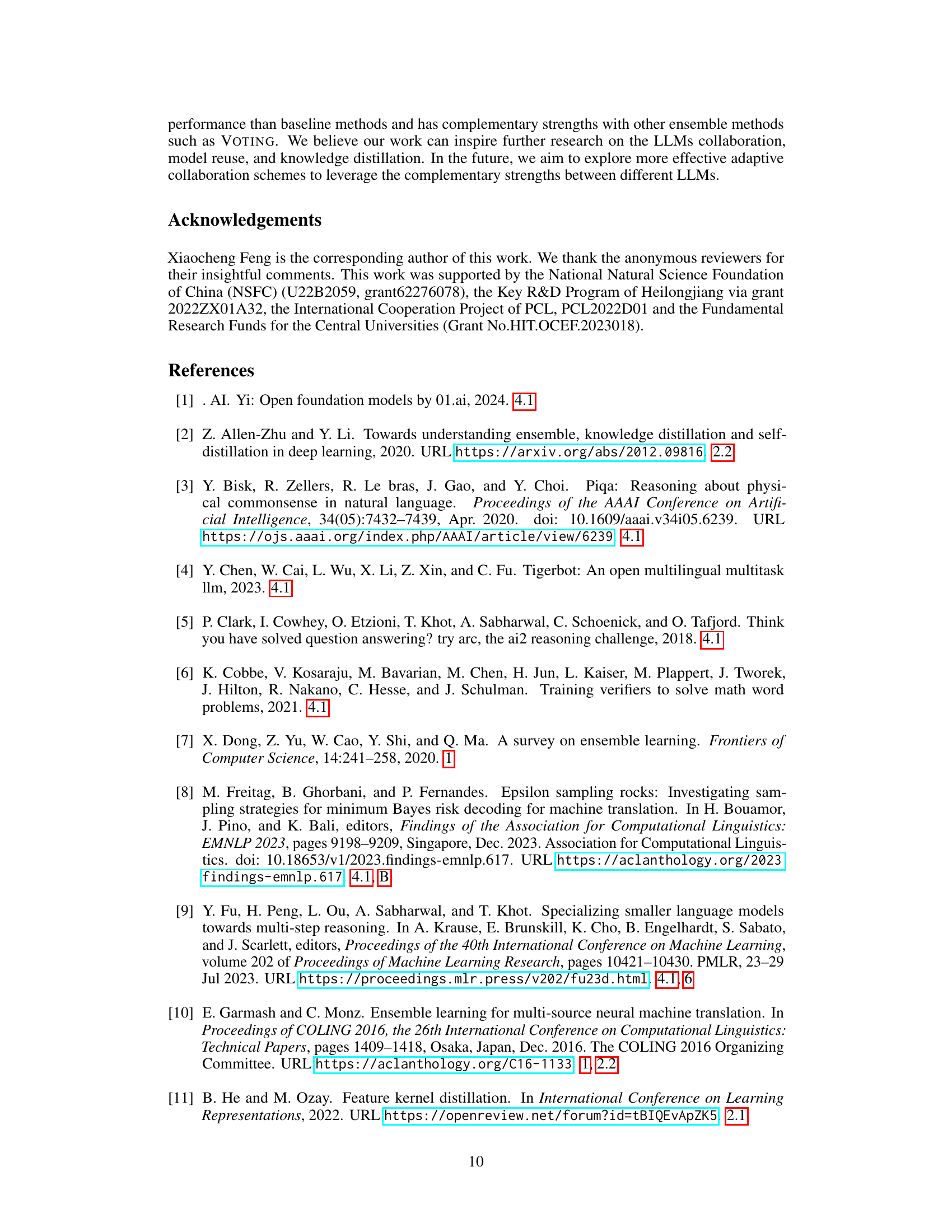

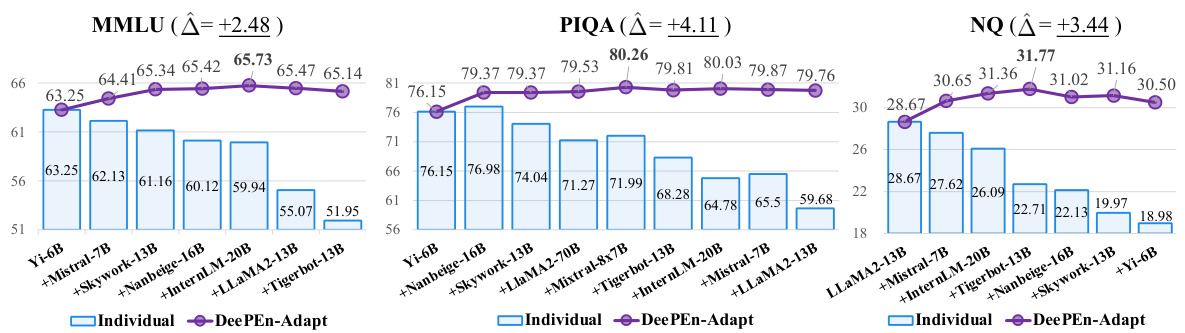

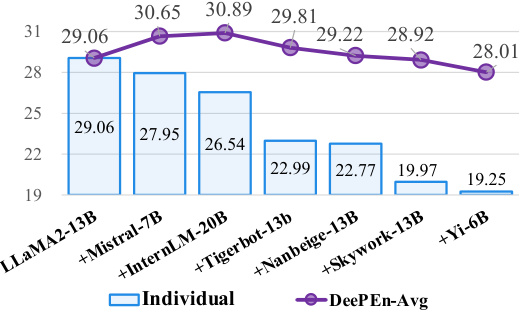

This figure shows the results of ensemble learning using different numbers of models on three benchmark datasets: MMLU, PIQA, and NQ. The models are added sequentially to the ensemble, ordered by their individual performance on a development set. The y-axis represents the performance (accuracy or exact match) on the test set, and the x-axis shows the number of models in the ensemble. The purple line shows the results of the DEEPEN-Adapt method (an adaptive weighting scheme), and the blue bars depict the individual model performances. The ‘A’ values indicate the maximum improvement gained by DEEPEN-Adapt over the best single model in each ensemble.

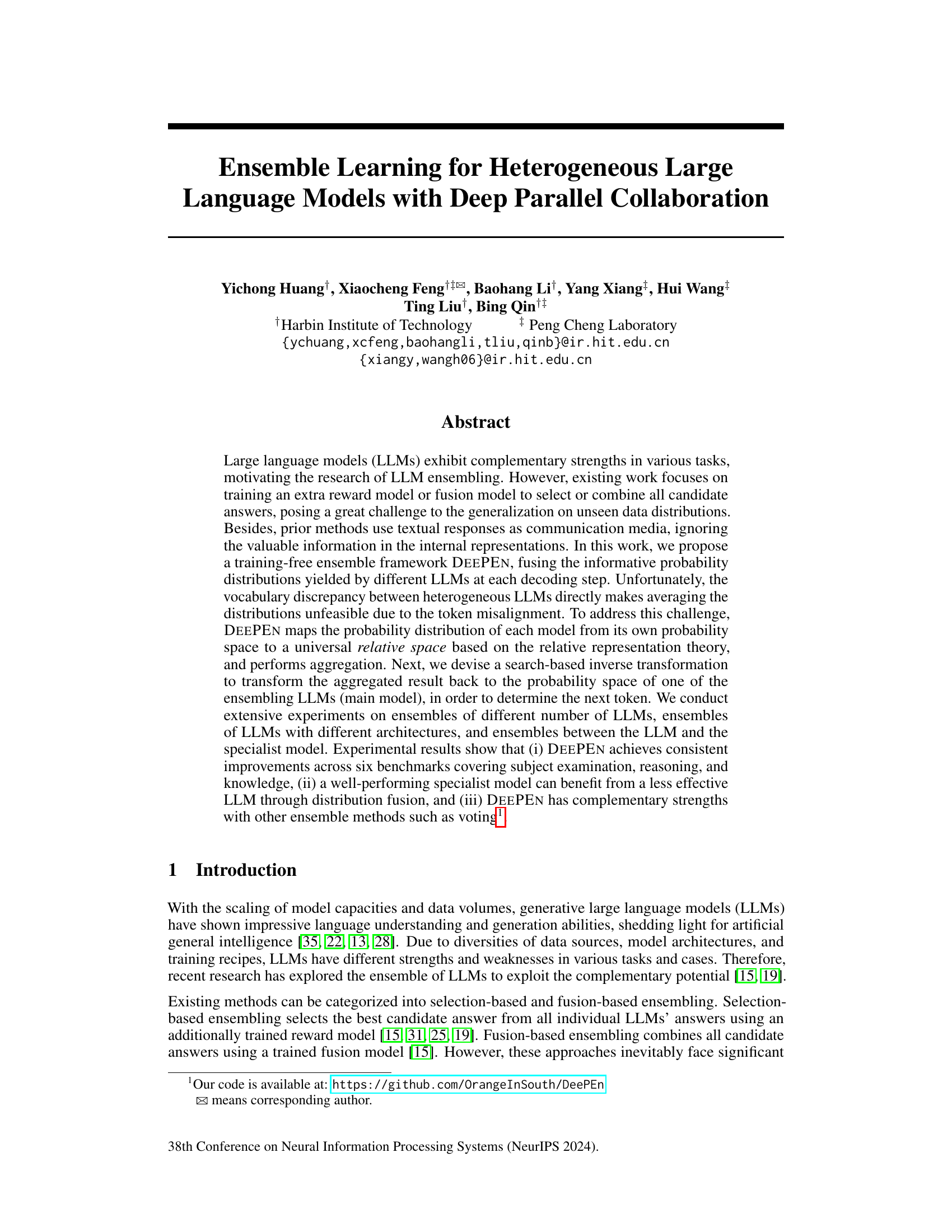

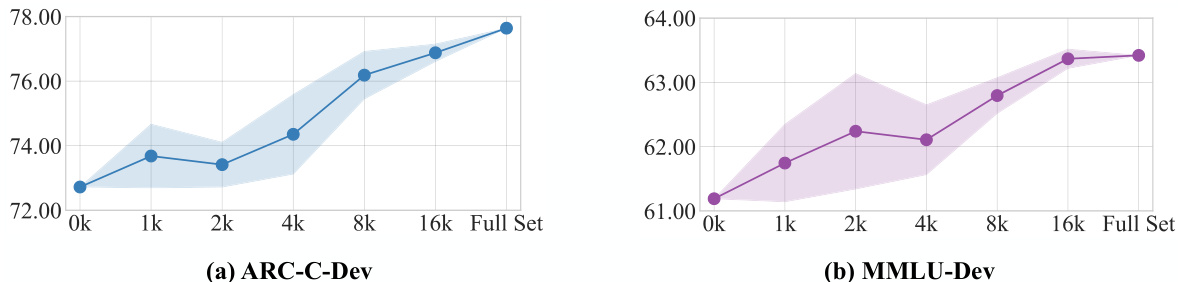

This figure shows the impact of the number of anchor words used in the relative representation on the model’s performance. The experiment was repeated four times for each number of anchor words. The results demonstrate an improvement in model performance as the number of anchor words increases, with a peak performance achieved when using the full set of common words.

This figure shows the results of ensemble learning on different numbers of models for three benchmark tasks (MMLU, PIQA, NQ). The models are added sequentially to the ensemble, in descending order of their individual performance on a development set. The graph shows that adding more models initially improves performance, but eventually leads to diminishing returns or even a slight performance decrease, suggesting an optimal ensemble size exists for each task. The ‘A’ values indicate the largest performance improvement achieved by the DEEPEN method compared to using a single model.

This figure visualizes relative representations of word embeddings from three different large language models (LLMs): LLaMA2-7B, LLaMA2-13B, and Mistral-7B. LLaMA2-7B and LLaMA2-13B share the same vocabulary, while Mistral-7B has a different one. The visualizations (using PCA and K-means clustering) show that despite vocabulary differences, the relative representations (measuring cosine similarity between embeddings and anchor tokens) exhibit a high degree of consistency between models with the same vocabulary. The red block highlights tokens unique to Mistral-7B’s vocabulary, illustrating the impact of vocabulary differences on absolute representations.

This figure visualizes relative representations of word embeddings from three different language models. Two models (LLama2-7B and LLama2-13B) share the same vocabulary, while Mistral-7B has a different vocabulary. The visualization uses PCA and K-means clustering to group similar embeddings. The plots show the consistency of relative representations across models, even with vocabulary differences. The red block highlights tokens unique to Mistral-7B’s vocabulary.

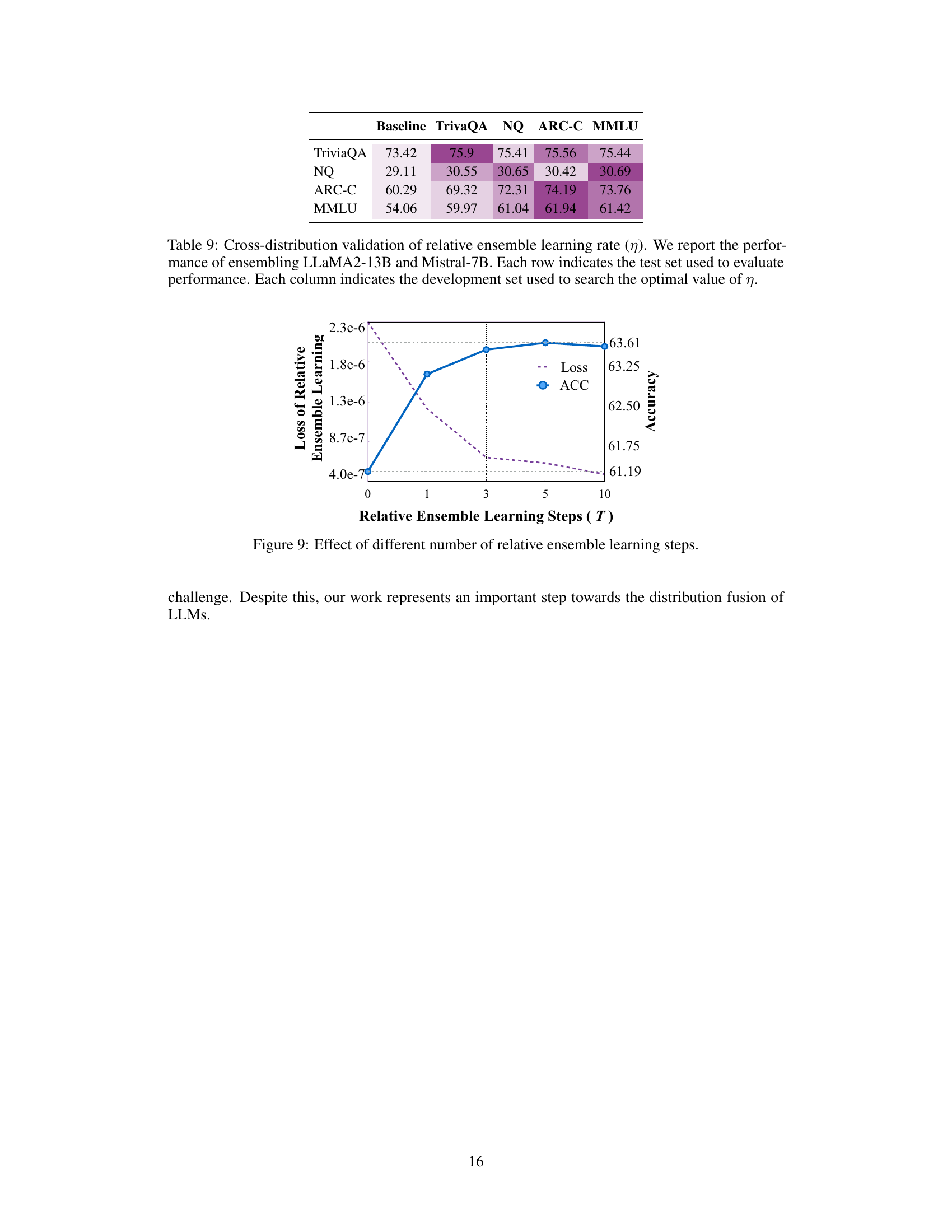

The figure shows the relationship between the number of relative ensemble learning steps (T) and the performance of DEEPEN. As the number of steps increases, the loss initially decreases sharply and then gradually plateaus, while the accuracy initially increases and then shows a slight decrease. This suggests that an optimal number of steps exists to balance the trade-off between reducing the loss and maintaining high accuracy.

More on tables

This table presents the main experimental results comparing different models and ensemble methods across six benchmark datasets. The benchmarks are categorized into comprehensive examination, reasoning capabilities, and knowledge capacities. Results are shown for individual models, top-2 model ensembles, and top-4 model ensembles. The table highlights the best performing individual model and the best performing ensemble method for each benchmark. It also shows the performance improvements achieved by different ensemble methods compared to the best individual model.

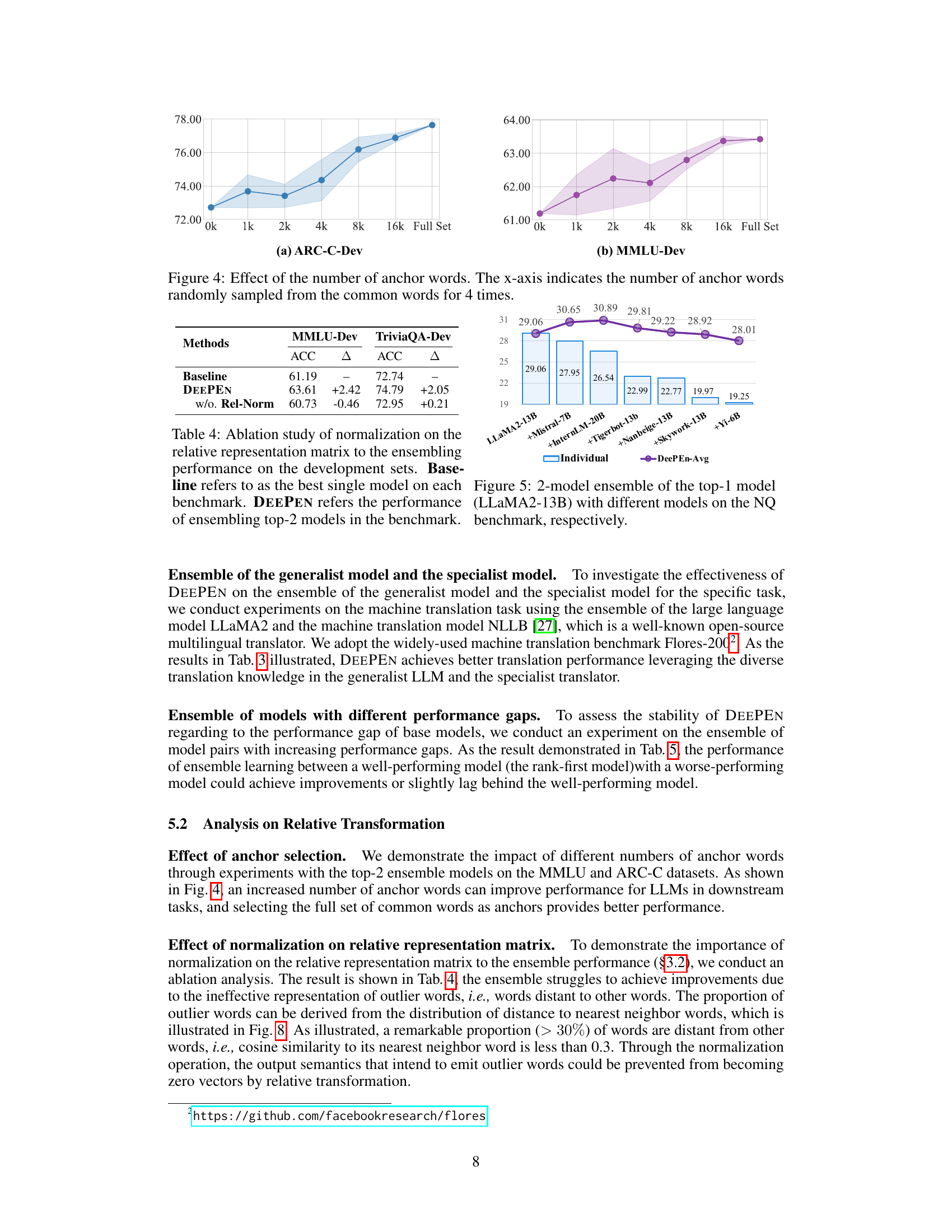

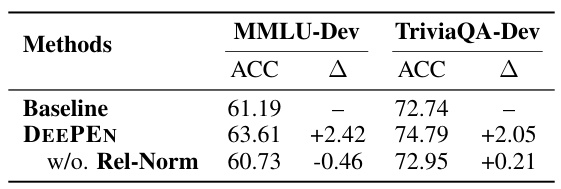

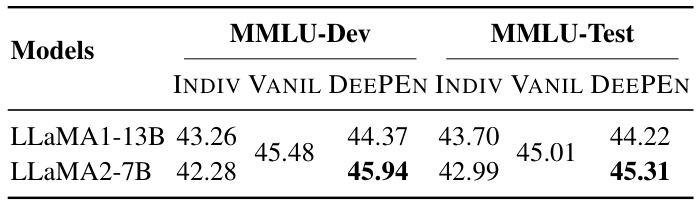

This table presents the ablation study results on the impact of normalization in the relative representation matrix on the model’s performance. It compares the performance of DEEPEN with and without normalization against the baseline (best single model) on the development sets for MMLU and TriviaQA.

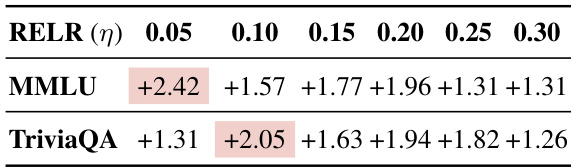

This table shows the impact of different relative ensemble learning rates (η) on the performance of the DEEPEN model. The improvements are calculated as the difference between the performance of the top-2 model ensemble using DEEPEN and the best performing individual model across two different datasets (MMLU and TriviaQA). The highlighted values indicate the best-performing RELR for each dataset, showing the model’s sensitivity to this hyperparameter.

This table presents the main results of the experiments conducted in the paper. It compares the performance of individual language models and several ensemble methods across six benchmarks. The benchmarks cover different aspects of language understanding, including comprehensive examination, reasoning capabilities, and knowledge capacities. The table highlights the best-performing individual model and ensemble method for each benchmark, indicating the effectiveness of the proposed DEEPEN framework compared to existing ensemble approaches.

This table presents the main results of the paper, comparing the performance of different models and ensemble methods on six benchmarks. The benchmarks are categorized into comprehensive examination, reasoning capabilities, and knowledge capacities. The table shows the performance of individual models and several ensemble techniques, including LLM-BLENDER, MINED, DEEPEN-Avg, and DEEPEN-Adapt, across all benchmarks. It highlights the best-performing individual model and ensemble method for each benchmark and indicates where methods were not applicable. The top 4 models for each benchmark are also identified.

This table presents the main experimental results, comparing the performance of individual LLMs and different ensemble methods (LLM-BLENDER, MINED, DEEPEN-Avg, DEEPEN-Adapt, VOTING, MBR) across six benchmark datasets categorized into comprehensive examination, reasoning capabilities, and knowledge capacities. The best-performing individual model and ensemble method are highlighted for each benchmark. The table also shows results for ensembles of two and four models, indicating the impact of ensemble size.

This table shows the inference latency of the DEEPEN model with different numbers of search steps (T) in the inverse transformation process. The baseline latency is 0.19 seconds, and the latency increases with increasing T, reaching 0.24 seconds at T=10. The relative change in latency is shown as a percentage increase compared to the baseline.

This table presents the main results of the experiments comparing different ensemble methods on six benchmark datasets. It shows the performance of individual models and various ensemble techniques, highlighting the best-performing individual model and ensemble method for each benchmark. The table categorizes the benchmarks into comprehensive examination, reasoning capabilities, and knowledge capacities. The results show the improvements achieved by different ensemble methods compared to individual models.

Full paper#