↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) are vulnerable to adversarial attacks that can bypass safety mechanisms. Existing adversarial training methods for LLMs are computationally expensive due to the need for discrete adversarial attacks at each training iteration. This hinders the widespread adoption of adversarial training in LLMs for improving robustness.

This paper proposes a new adversarial training algorithm (CAT) that utilizes continuous attacks in the embedding space of LLMs, which is orders of magnitude more efficient than existing discrete methods. It also introduces CAPO, a continuous variant of IPO that does not require utility data for adversarially robust alignment. Experiments show that these methods significantly enhance LLM robustness against various attacks while maintaining utility, offering a pathway towards scalable adversarial training for robustly aligning LLMs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel and efficient approach to adversarial training for large language models (LLMs). It addresses the significant computational cost of existing methods, opening avenues for improving the robustness of LLMs against various attacks while maintaining their utility. The findings challenge existing evaluation protocols and suggest potential improvements, shaping future research in LLM safety and robustness. This is particularly timely given the increasing integration of LLMs into various applications.

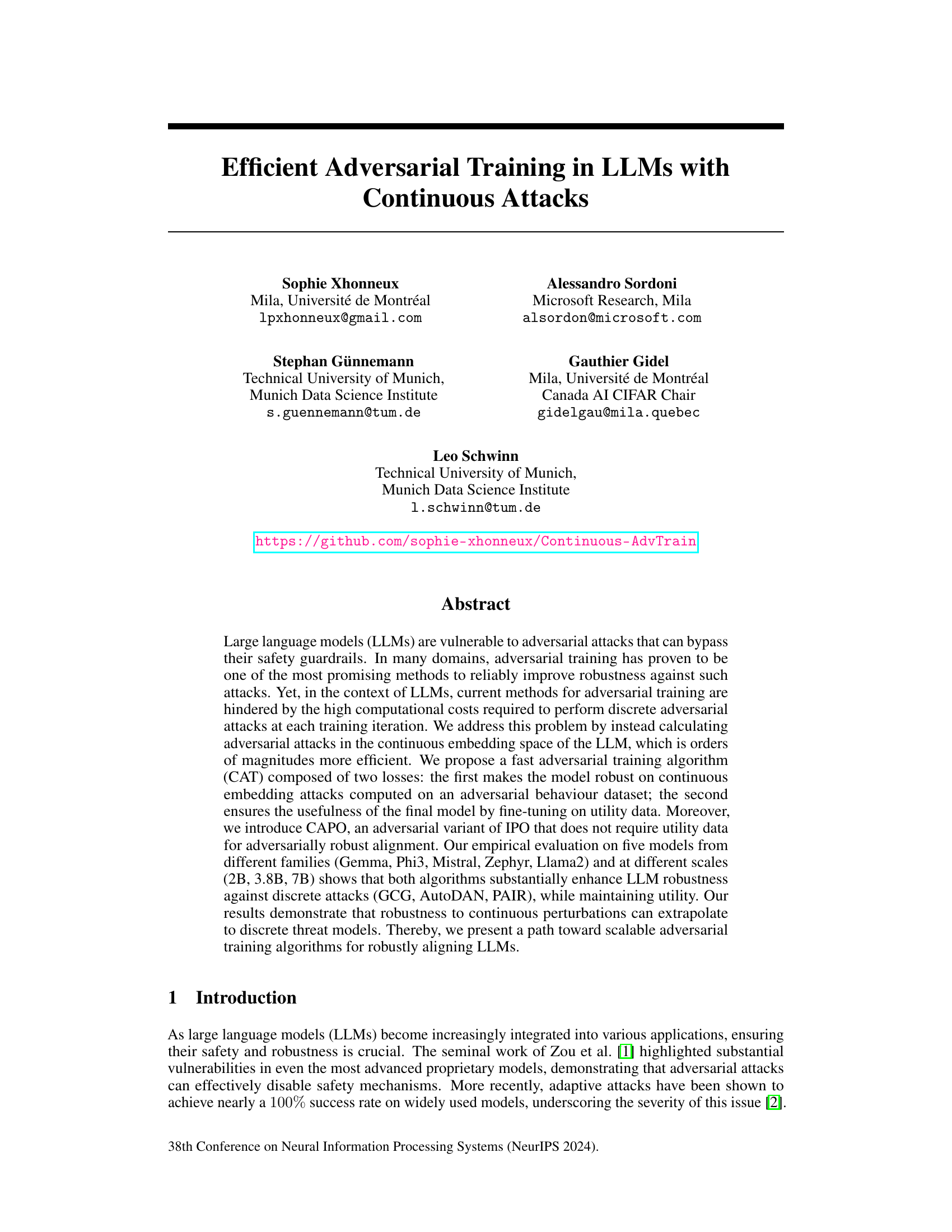

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the proposed continuous adversarial training (CAT) method. The left side shows the training loop where the input prompt is converted into embeddings. Instead of applying discrete adversarial attacks to the tokens directly, CAT applies continuous attacks to the embeddings. The right side shows that the model’s robustness achieved against continuous attacks in the embedding space extrapolates to robustness against discrete attacks, such as suffix attacks using Greedy Coordinate Gradient (GCG) and jailbreak attacks using AutoDAN and PAIR. This is achieved with significantly faster computation.

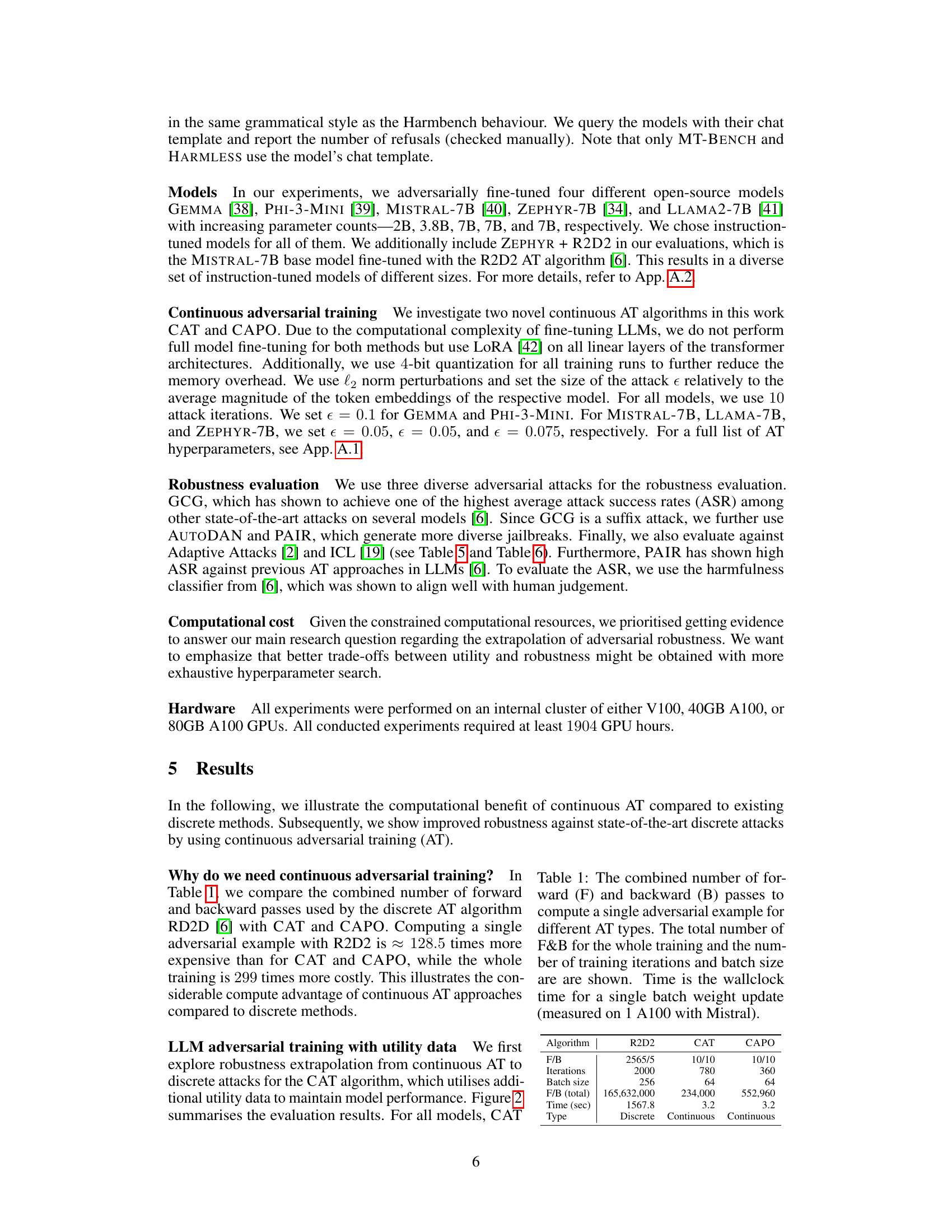

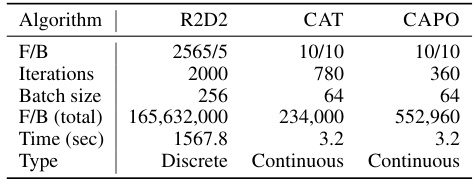

This table compares the computational efficiency of three different adversarial training algorithms: R2D2, CAT, and CAPO. It shows the number of forward and backward passes required to compute a single adversarial example, the total number of forward and backward passes for the entire training process, the number of training iterations, batch size, and the time taken for a single batch weight update. The table highlights the significant computational advantage of CAT and CAPO over R2D2, demonstrating that continuous adversarial attacks can be far more efficient than discrete attacks.

In-depth insights#

Continuous AdvTrain#

The concept of “Continuous AdvTrain” suggests a novel approach to adversarial training, likely within the context of large language models (LLMs). Instead of relying on discrete adversarial attacks, which involve manipulating individual tokens, this method operates in the continuous embedding space of the LLM. This offers a significant advantage in terms of computational efficiency, as continuous attacks are orders of magnitude faster to compute than discrete ones. The training process likely involves generating continuous perturbations to input embeddings, aiming to improve the model’s robustness against a wide range of adversarial examples. A key aspect would be how well robustness learned in the continuous embedding space translates to the discrete token space of actual LLM inputs. The effectiveness of “Continuous AdvTrain” would depend on the chosen loss function, the method of generating continuous perturbations and the overall training strategy. Successful implementation could offer a path to more scalable and efficient adversarial training for LLMs, resulting in more robust and reliable models.

CAT & CAPO Losses#

The core of this research lies in developing novel adversarial training algorithms for Large Language Models (LLMs) to enhance their robustness against attacks. CAT (Continuous Adversarial Training) leverages the efficiency of continuous attacks in the embedding space, drastically reducing computational costs compared to discrete methods. This efficiency is crucial for scalable adversarial training. CAPO (Continuous Adversarial Preference Optimization) builds upon CAT but introduces an adversarial variant of IPO, eliminating the need for utility data during training, making it even more efficient and potentially improving robustness-utility trade-offs. Both CAT and CAPO demonstrate that robustness against continuous perturbations successfully extrapolates to discrete attacks, paving the way for more efficient and robust LLM training.

Robustness Extrapolation#

The concept of “Robustness Extrapolation” in the context of large language models (LLMs) centers on the ability of a model trained to be robust against a certain type of attack (e.g., continuous embedding perturbations) to maintain that robustness when faced with different attacks. The core idea is that training with computationally efficient continuous attacks can lead to improved performance against significantly more expensive discrete attacks. This is crucial because discrete adversarial attacks, while effective at exposing vulnerabilities, are computationally costly and thus unsuitable for regular training. The research likely demonstrates that a model’s resistance to small, continuous changes in its input embedding space generalizes to a wider range of more substantial discrete changes, making continuous adversarial training a practical and scalable approach to enhance LLM robustness. The successful extrapolation hinges on the underlying representational structure of the LLM and the relationship between continuous and discrete perturbation spaces. This work likely provides valuable insights for the development of more efficient and scalable adversarial training techniques for LLMs, ultimately improving their safety and reliability.

Utility Trade-offs#

The concept of “utility trade-offs” in the context of adversarial training for large language models (LLMs) is crucial. Robustness against adversarial attacks often comes at the cost of reduced utility, meaning the model may become less helpful or accurate on benign inputs. This trade-off arises because adversarial training modifies the model to resist malicious inputs, potentially altering its behavior in unintended ways. Finding the optimal balance is a key challenge. Different adversarial training techniques exhibit varying degrees of this trade-off. Some methods prioritize robustness, even at the expense of significant utility loss, while others aim for a more balanced approach. The choice between these approaches depends on the specific application and the relative importance of robustness versus utility. Careful evaluation of the robustness-utility trade-off is essential, using various benchmarks and metrics, to ensure that the resulting model provides both safety and functionality. This necessitates a nuanced understanding of the limitations and potential downsides of different adversarial training strategies in the context of LLMs.

Failure Modes#

The section on ‘Failure Modes’ in this research paper offers critical insights into the limitations of current adversarial training methods for LLMs and robustness evaluation benchmarks. It highlights how existing evaluation metrics, focusing on utility and robustness separately, can be misleading, due to the inherent dependence on chat templates or specific grammatical structures. The paper emphasizes the model’s tendency to overfit safety objectives, leading to excessive refusals even on harmless prompts, a crucial issue often overlooked in prior studies. The inherent biases in existing datasets, such as Harmbench, are identified as potential sources of failure, as models trained on these data may not generalize well to diverse and nuanced scenarios. This analysis underscores the importance of developing more comprehensive and realistic evaluation benchmarks that address limitations in current practices. The authors’ exploration of this crucial area significantly contributes to a more robust and reliable evaluation of adversarial training techniques for LLMs.

More visual insights#

More on figures

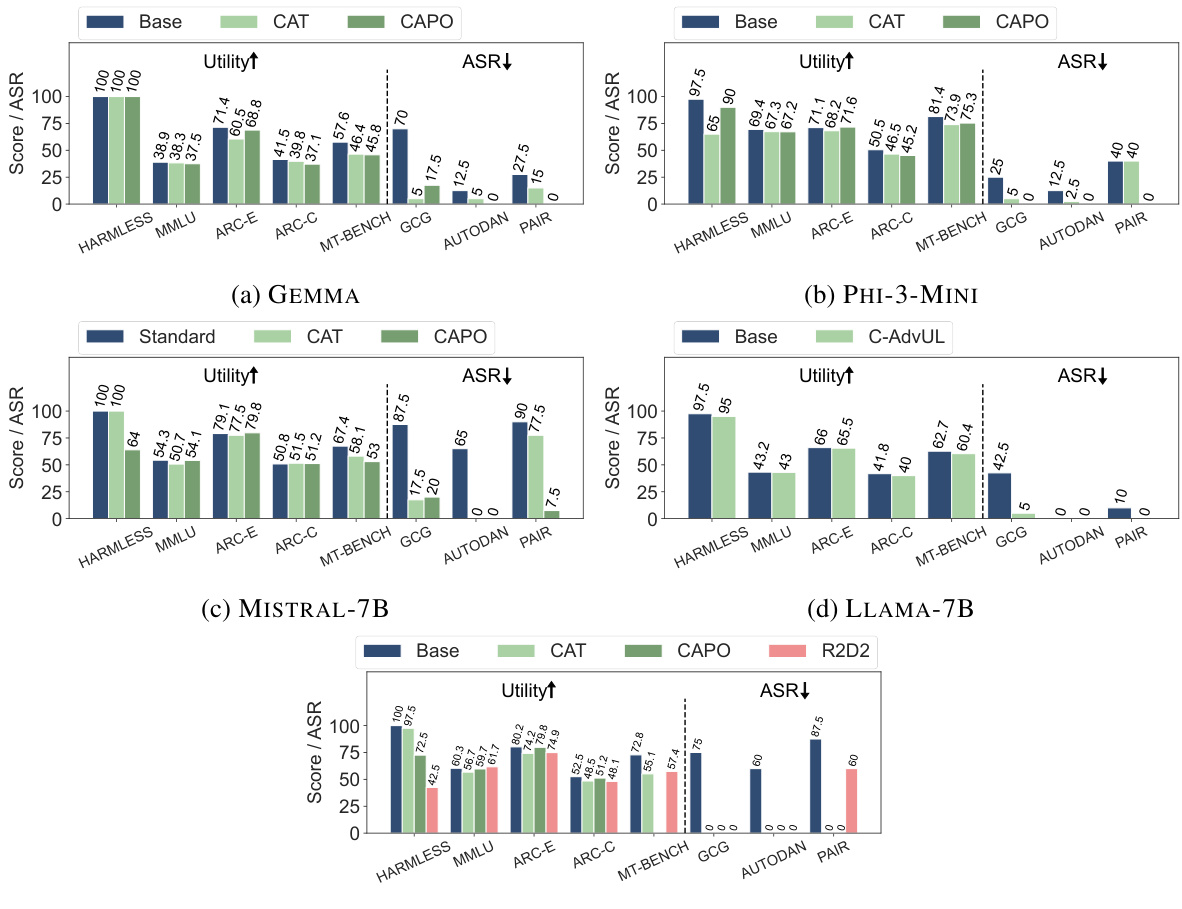

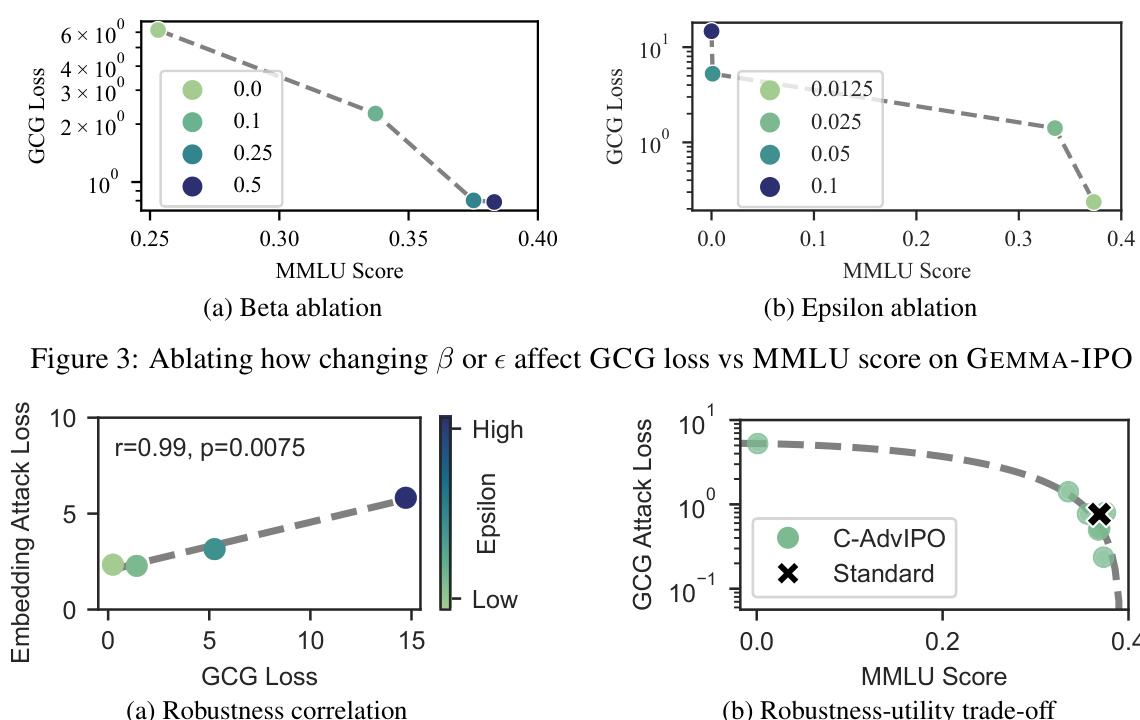

This figure shows the trade-off between utility and robustness for three different adversarial training methods (CAT, CAPO, and R2D2) across five different LLMs. It compares the performance of these methods against several benchmarks measuring both utility (MMLU, ARC-E, ARC-C, MT-BENCH) and robustness (GCG, AUTODAN, PAIR) against various attacks. The results illustrate that the proposed methods (CAT and CAPO) achieve significantly better robustness with a minor decrease in utility compared to the baseline and R2D2.

This figure shows the results of experiments comparing three adversarial training methods (CAT, CAPO, and R2D2) across five different language models. The goal is to evaluate the trade-off between model utility (measured by performance on MMLU, ARC-E, ARC-C, and MT-BENCH) and robustness against adversarial attacks (GCG, AutoDAN, and PAIR). The figure demonstrates that CAT and CAPO achieve significantly higher robustness than R2D2 with only a small decrease in utility, suggesting that these methods are effective for improving the robustness of LLMs against attacks.

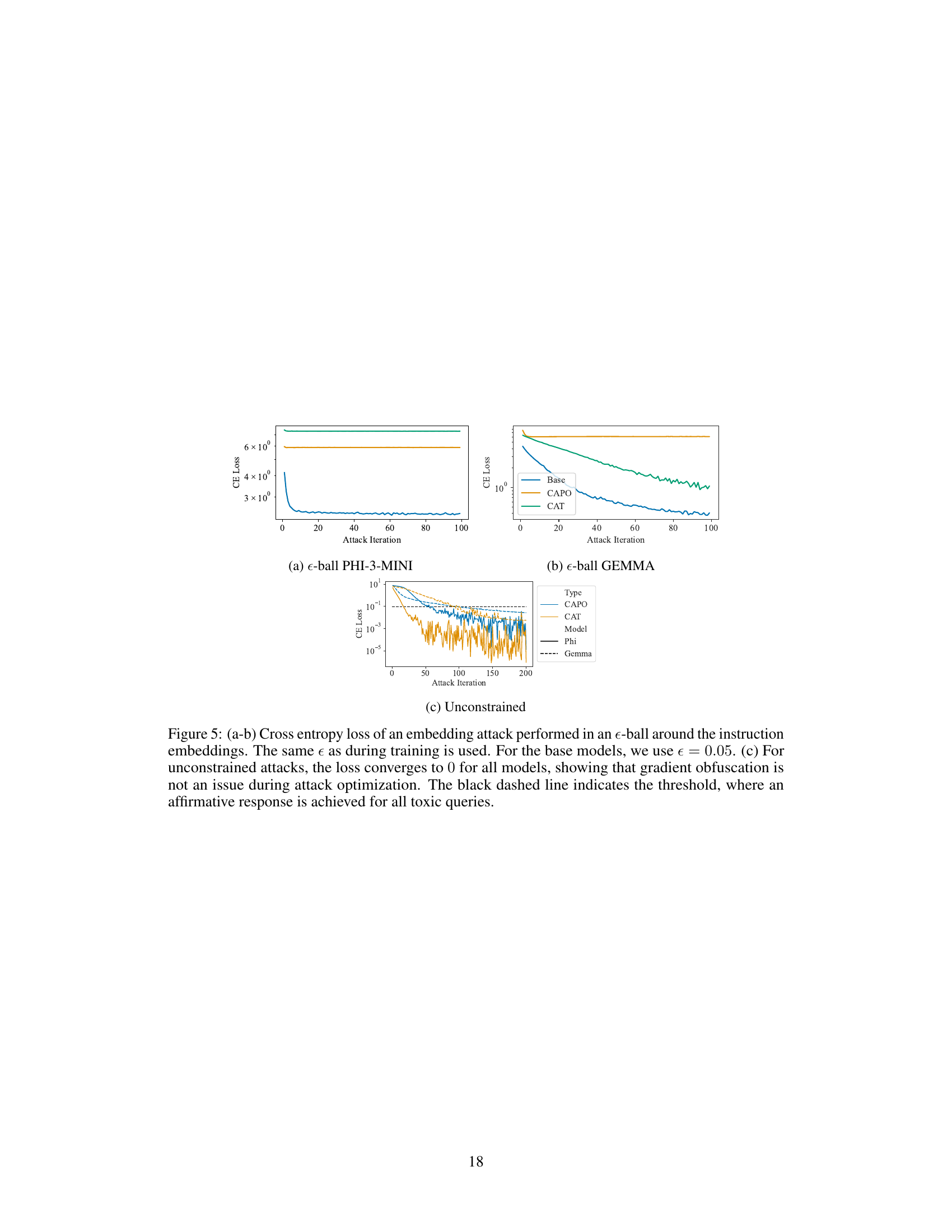

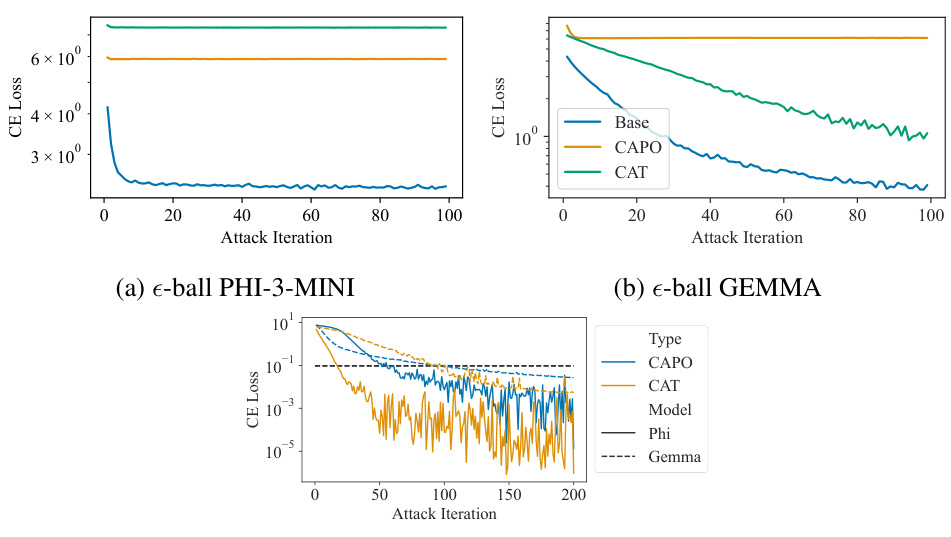

This figure shows the results of an embedding attack performed on two different models, PHI-3-MINI and GEMMA. The attacks are performed within an e-ball around the instruction embeddings, using the same epsilon value as during training. Subfigure (a) and (b) show the cross-entropy loss for each attack iteration, demonstrating that adversarial training improves the models’ robustness against these attacks. Subfigure (c) shows the results of an unconstrained attack, illustrating that even without constraints, gradient obfuscation is not a significant factor and the models still ultimately fail when the attacks are unconstrained.

More on tables

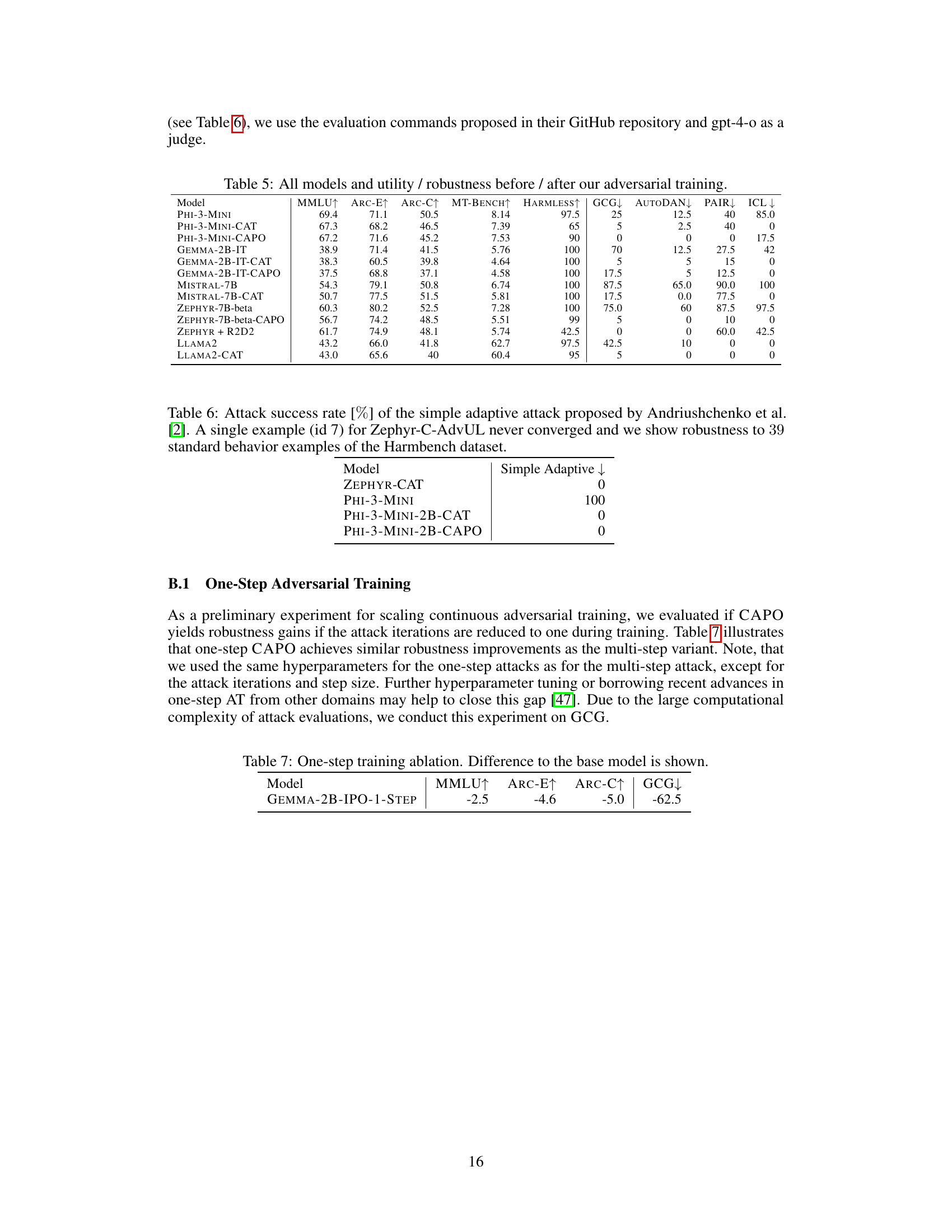

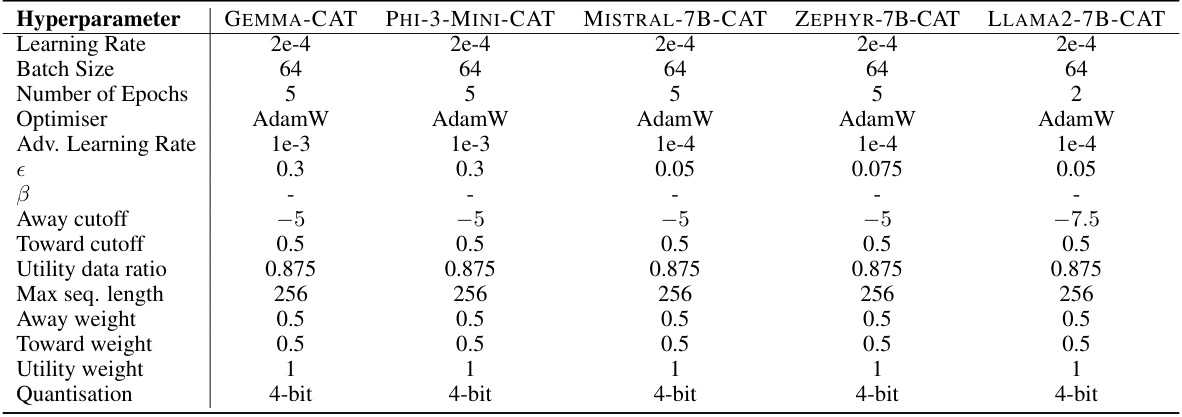

This table lists the hyperparameter settings used for training the various language models using the Continuous-Adversarial UL (CAT) algorithm. The hyperparameters cover learning rate, batch size, number of epochs, optimizer, adversarial learning rate, epsilon (attack strength), beta (IPO parameter, only relevant for CAPO), cutoff values for away and toward losses, the utility data ratio, maximum sequence length, and weights for away, toward and utility losses. Quantization level is also included.

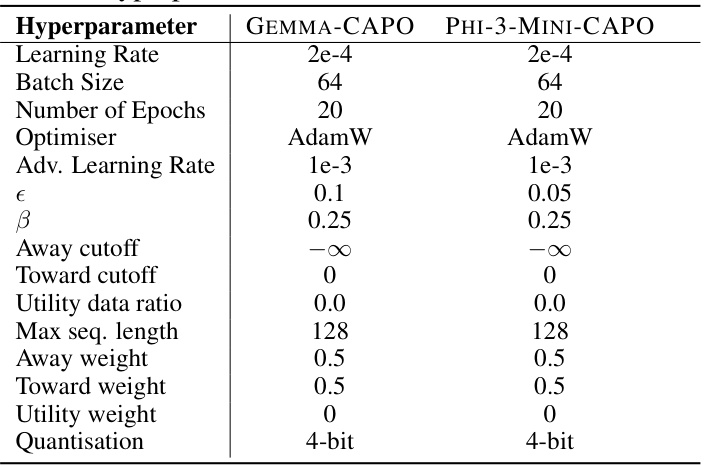

This table shows the hyperparameter settings used for training models using the CAPO algorithm. It includes parameters related to learning rate, batch size, number of epochs, optimizer, adversarial learning rate, epsilon (attack strength), beta (IPO parameter), cutoffs for away and toward losses, utility data ratio, maximum sequence length, loss weights, and quantization.

This table lists the six large language models (LLMs) used in the paper’s experiments. For each model, it provides the model name, a reference to its source, and a URL where it can be accessed.

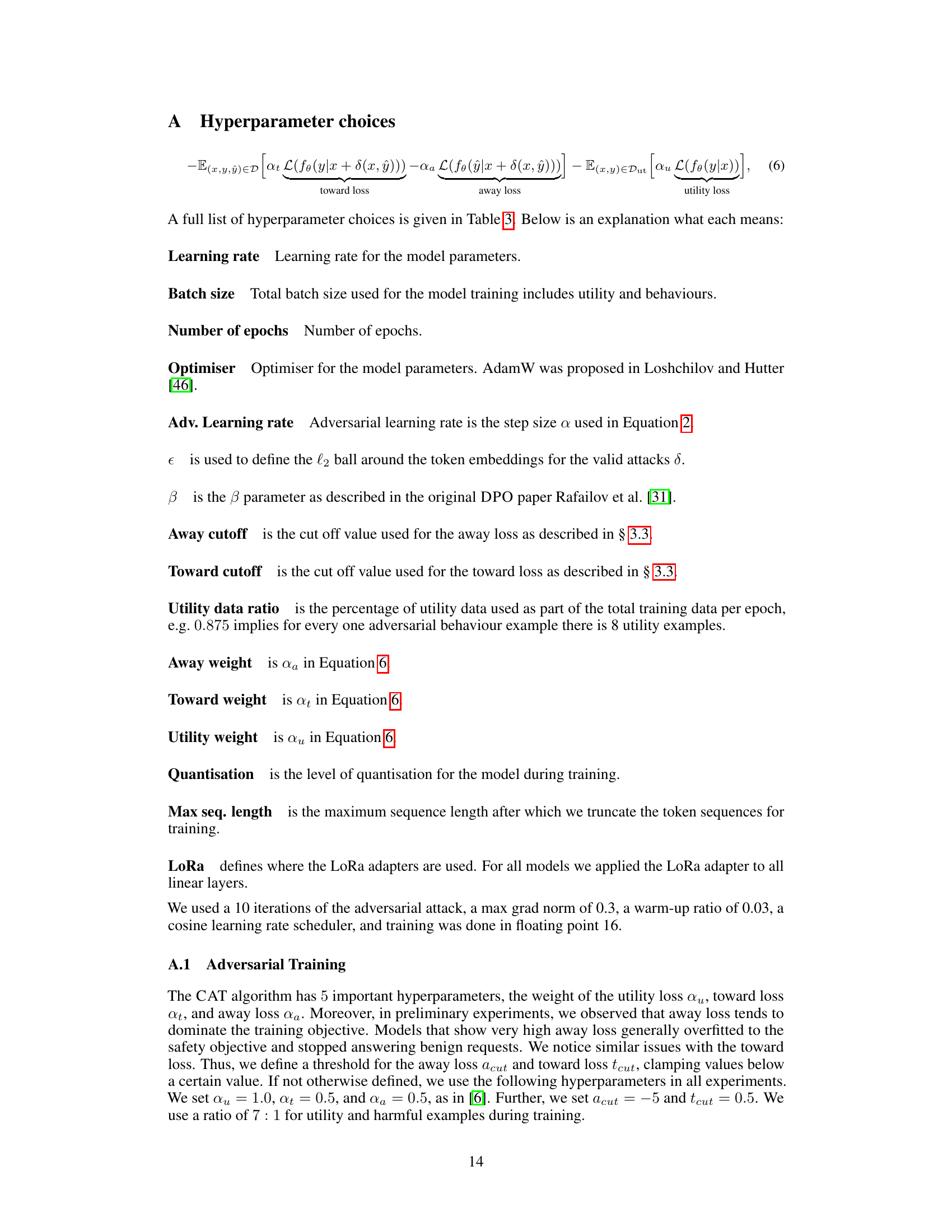

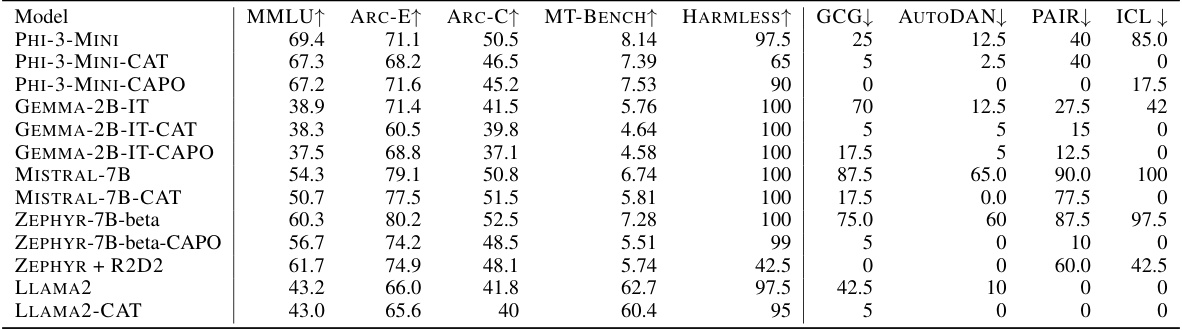

This table presents a comprehensive evaluation of different Language Models (LLMs) before and after applying two novel adversarial training algorithms: Continuous-Adversarial UL (CAT) and Continuous-Adversarial IPO (CAPO). It compares their performance to a baseline model (ZEPHYR + R2D2) using several metrics, including utility benchmarks (MMLU, ARC-E, ARC-C, MT-BENCH, HARMLESS) and robustness against various adversarial attacks (GCG, AutoDAN, PAIR, ICL). The table shows the trade-off between model utility and robustness to different attack strategies, highlighting the effectiveness of CAT and CAPO in improving model robustness.

This table presents the attack success rates of the simple adaptive attack proposed by Andriushchenko et al. [2] on several models. The simple adaptive attack’s success rate is measured against 39 standard behavior examples from the Harmbench dataset. One model (Zephyr-C-AdvUL) failed to converge on a single example (id 7), which is noted. The results show the effectiveness of different adversarial training methods in mitigating the impact of this specific attack.

This table shows the results of an ablation study comparing the performance of a one-step adversarial training approach to the multi-step approach. It indicates the changes in MMLU, ARC-E, ARC-C, and GCG metrics when using one-step adversarial training compared to the baseline model.

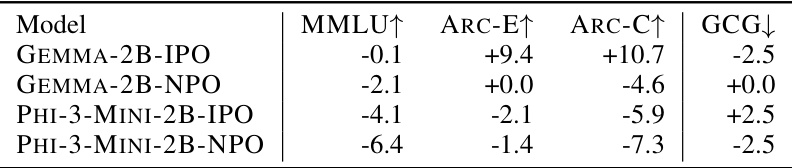

This table presents the results of an ablation study where the model was trained using IPO and NPO methods without adversarial attacks. It compares the performance on MMLU, ARC-E, ARC-C, and GCG to the base model, showcasing the impact of removing adversarial training from the training process. The difference from the base model in terms of MMLU score (higher is better), ARC-E score (higher is better), ARC-C score (higher is better), and GCG loss (lower is better) is presented.

This table presents the results of an ablation study where the models were fine-tuned using IPO and NPO without adversarial training. The results show the difference in MMLU, ARC-E, ARC-C, and GCG scores compared to the baseline models. It demonstrates that neither IPO nor NPO without adversarial attacks improve robustness.

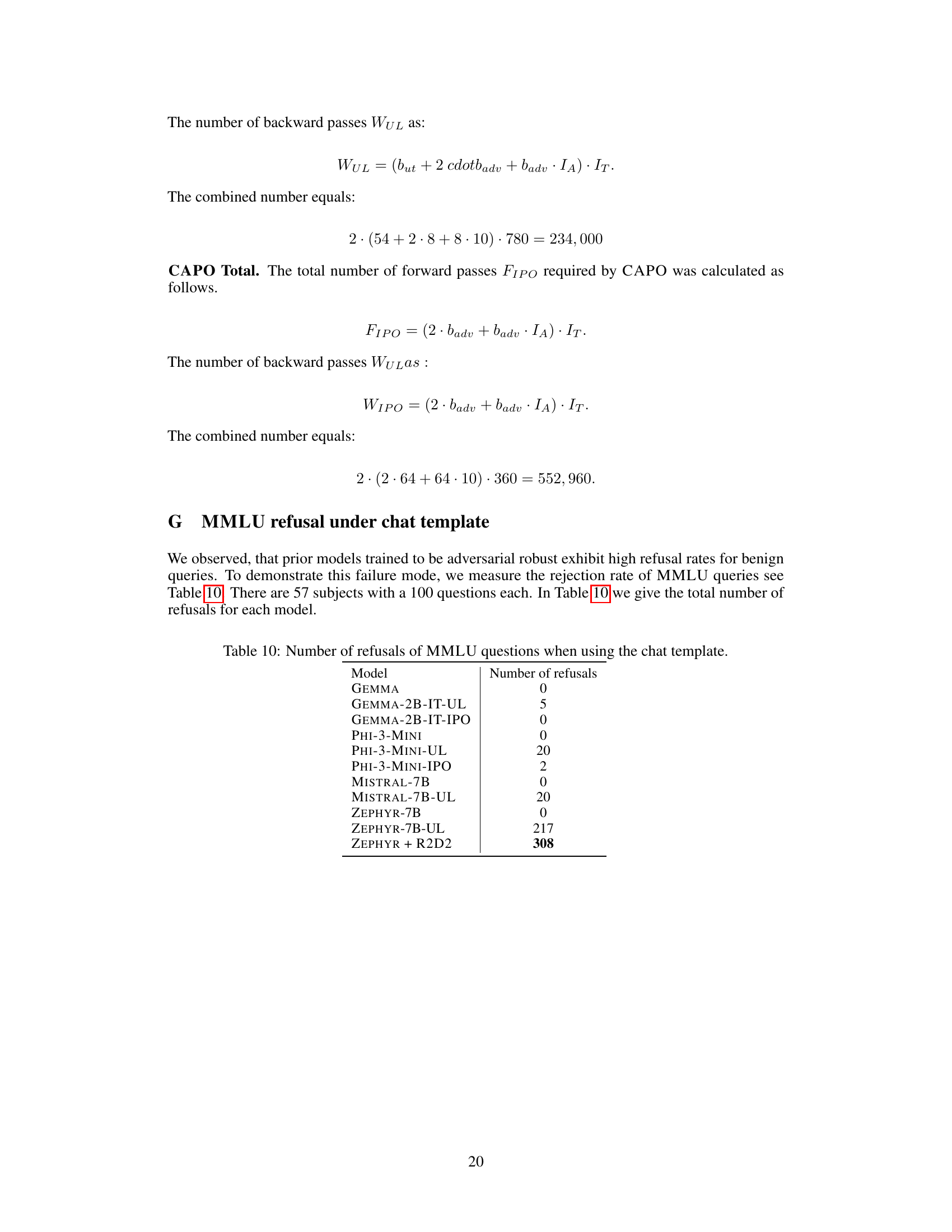

This table presents the number of times each model refused to answer a question from the MMLU benchmark when the chat template was enabled. The models listed include both baseline models and models trained using different adversarial training techniques (UL, IPO). The results highlight a potential failure mode where models trained for adversarial robustness become overly cautious and refuse to answer even benign questions.

This table presents the attack success rate (ASR) for different models on the POLITEHARMBENCH dataset. The POLITEHARMBENCH dataset is a modified version of the original Harmbench dataset, where harmful prompts are rephrased in a polite manner. This table shows how the politeness of the prompts affects the model’s vulnerability to adversarial attacks. The models include various versions of GEMMA, PHI-3-MINI, MISTRAL-7B, ZEPHYR-7B, and ZEPHYR + R2D2, both with and without adversarial training (UL and IPO) applied. The results highlight the potential vulnerabilities even when adversarial attacks are expressed politely.

Full paper#