↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) currently rely heavily on Transformers, which face challenges regarding computational cost and context length limitations. LSTMs, while effective for sequential data, have been outpaced by Transformers. This paper addresses these limitations by improving LSTMs. Existing LSTMs are limited in revising storage decisions, have limited storage capacity, and lack parallelizability, hindering scaling to larger models.

The researchers introduce XLSTM, which incorporates exponential gating for better storage decision revision and includes two new LSTM variants: sLSTM with a scalar memory update and mLSTM with a fully parallelizable matrix memory and covariance update rule. XLSTM is then integrated into residual backbones to create XLSTM blocks, which are then stacked to form xLSTM architectures. Benchmarking against state-of-the-art models shows that XLSTM significantly outperforms current language models in both performance and scalability.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it significantly advances the field of large language models by improving the scalability and performance of LSTMs. It introduces novel architectural modifications and optimization techniques that allow LSTMs to perform favorably when compared to state-of-the-art Transformers, opening new research avenues for both LSTM and LLM researchers. This is particularly relevant given the limitations and computational costs associated with current Transformer models.

Visual Insights#

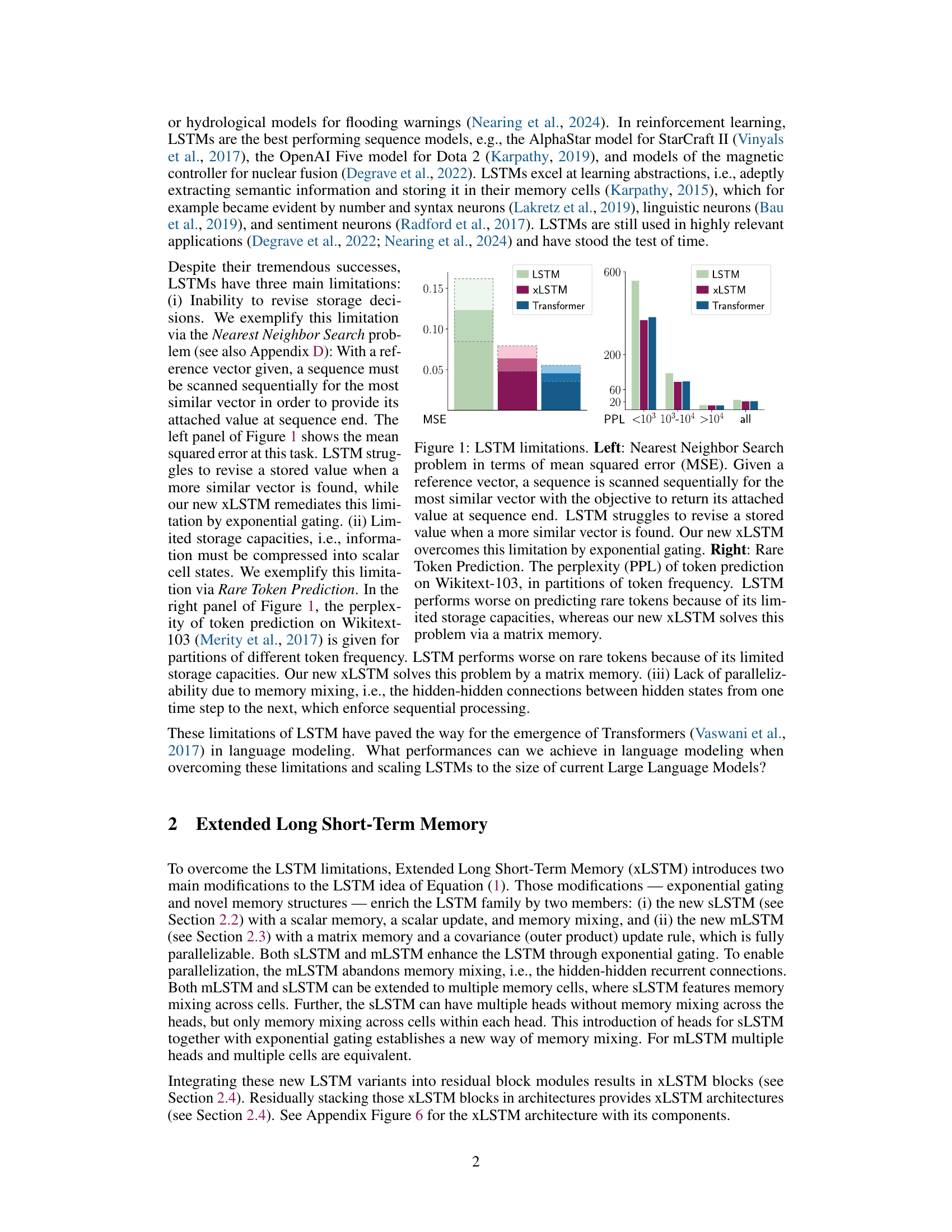

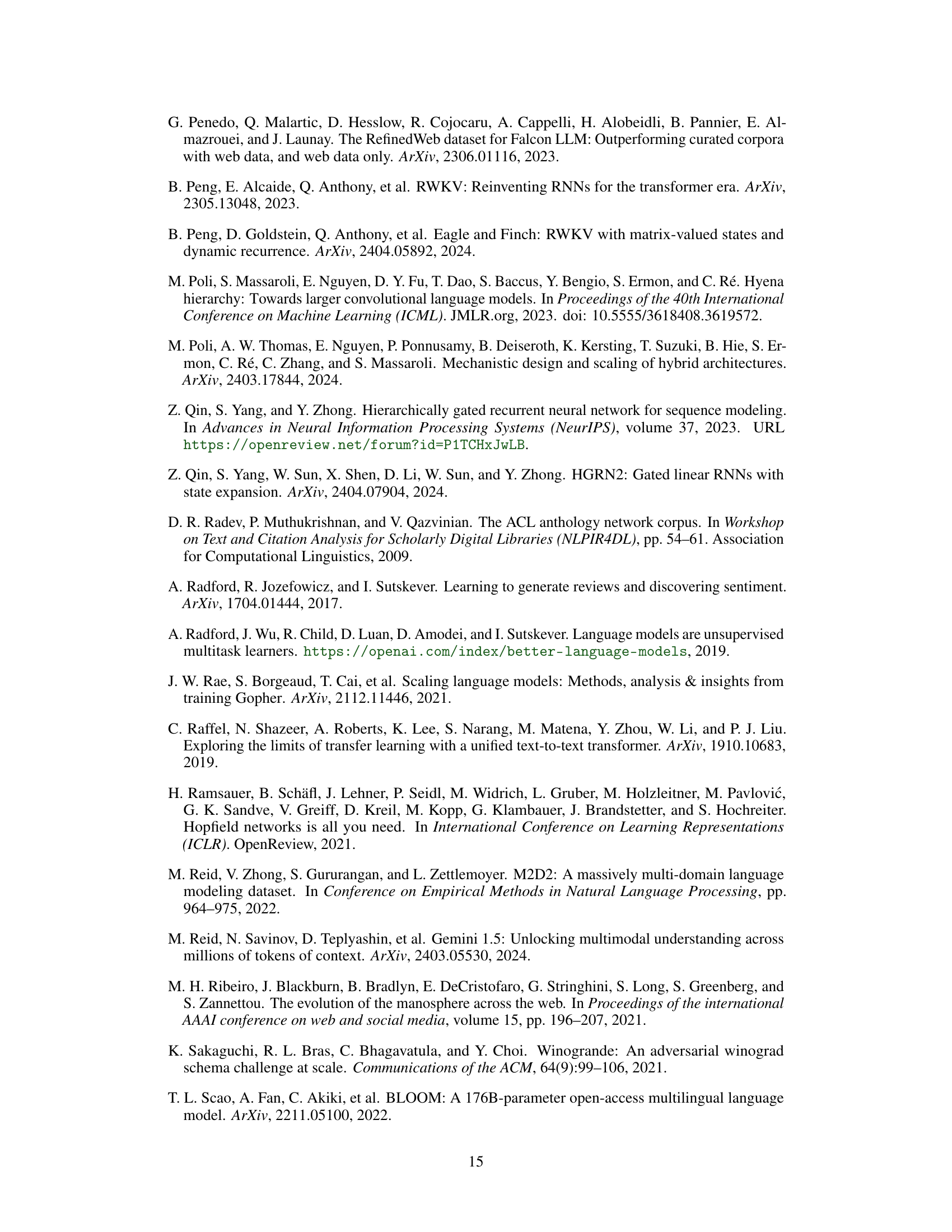

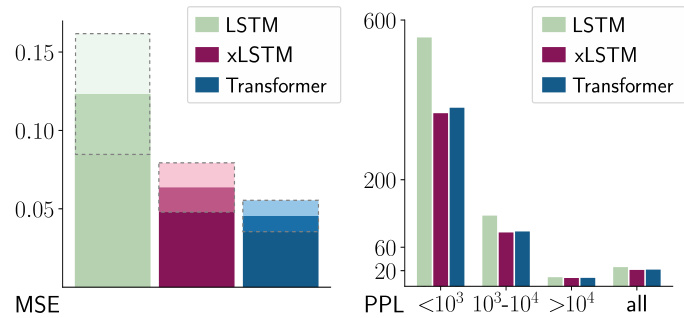

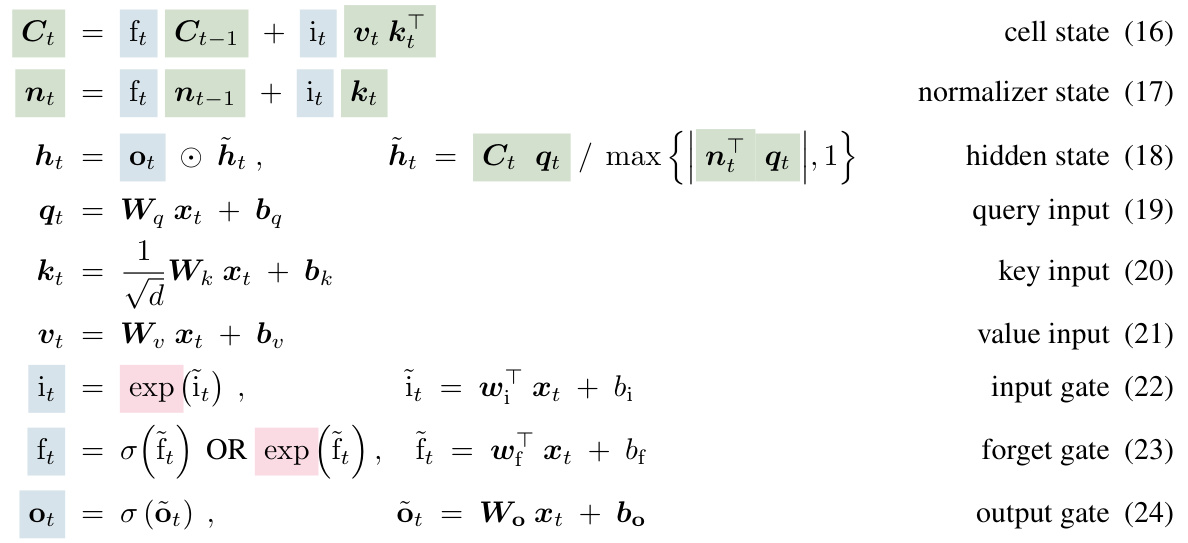

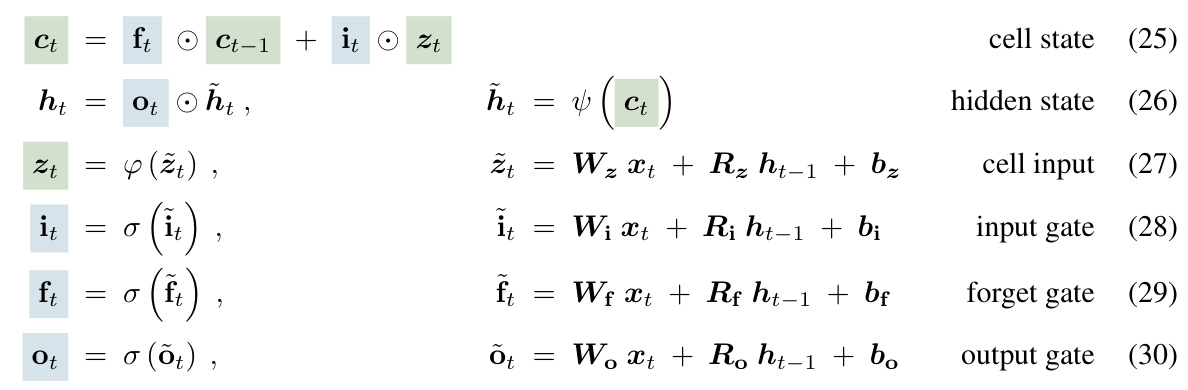

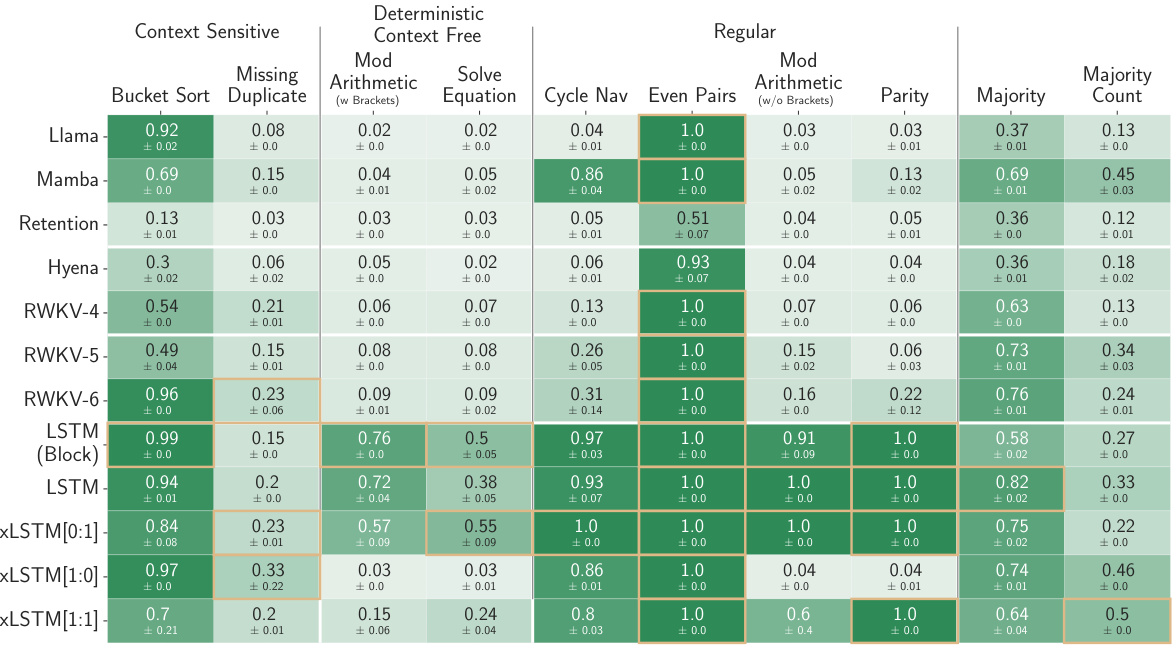

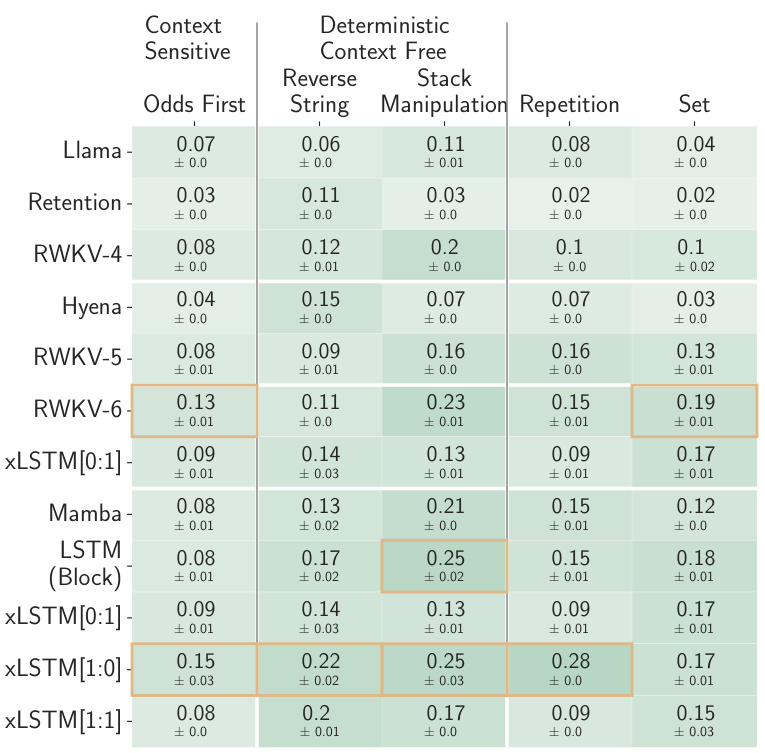

The figure demonstrates two limitations of LSTMs. The left panel shows the mean squared error (MSE) for the Nearest Neighbor Search task, highlighting LSTMs’ struggle to revise stored values upon finding a more similar vector. The right panel displays the perplexity (PPL) of token prediction on the Wikitext-103 dataset, partitioned by token frequency, revealing LSTMs’ poorer performance on rare tokens due to limited storage. The figure emphasizes that the proposed XLSTM architecture addresses both limitations.

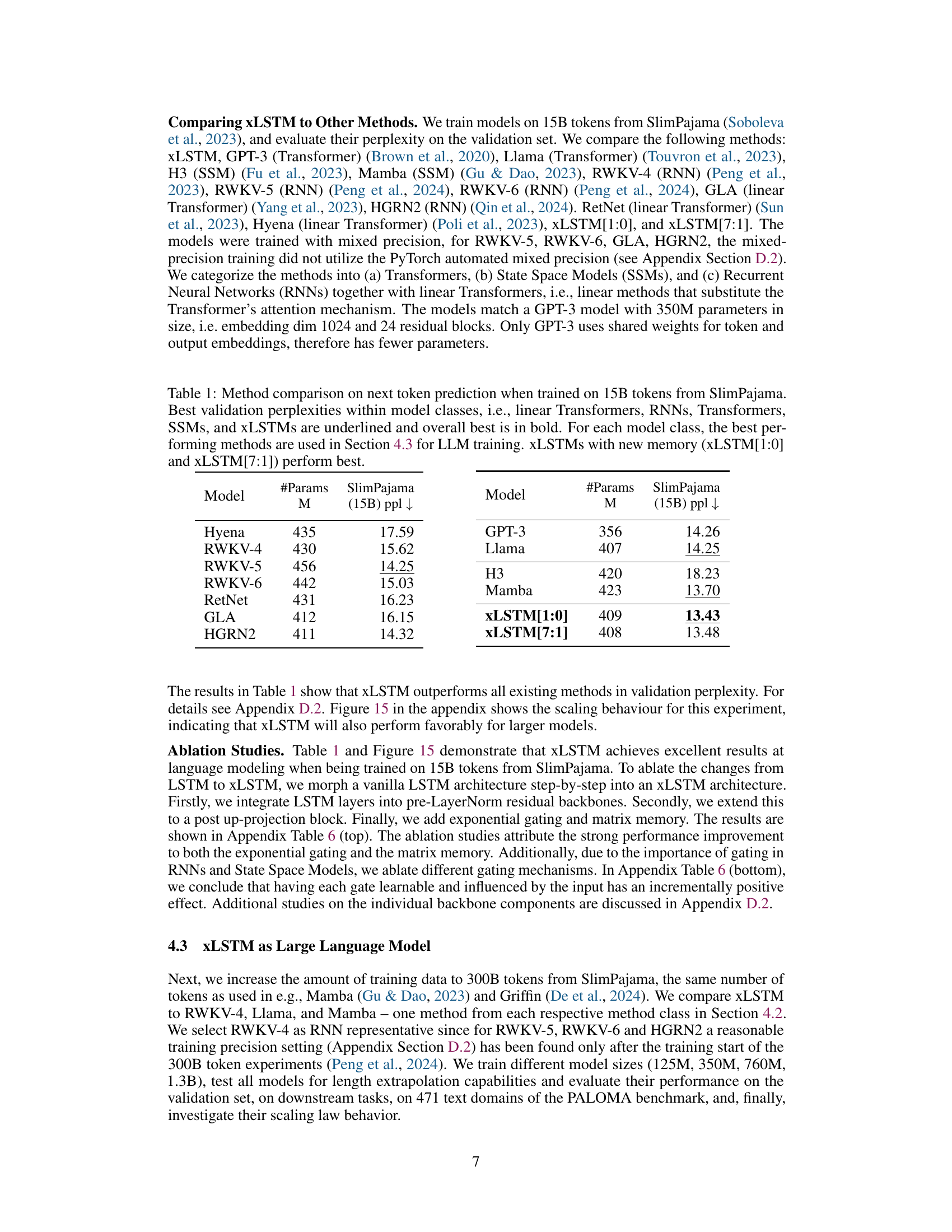

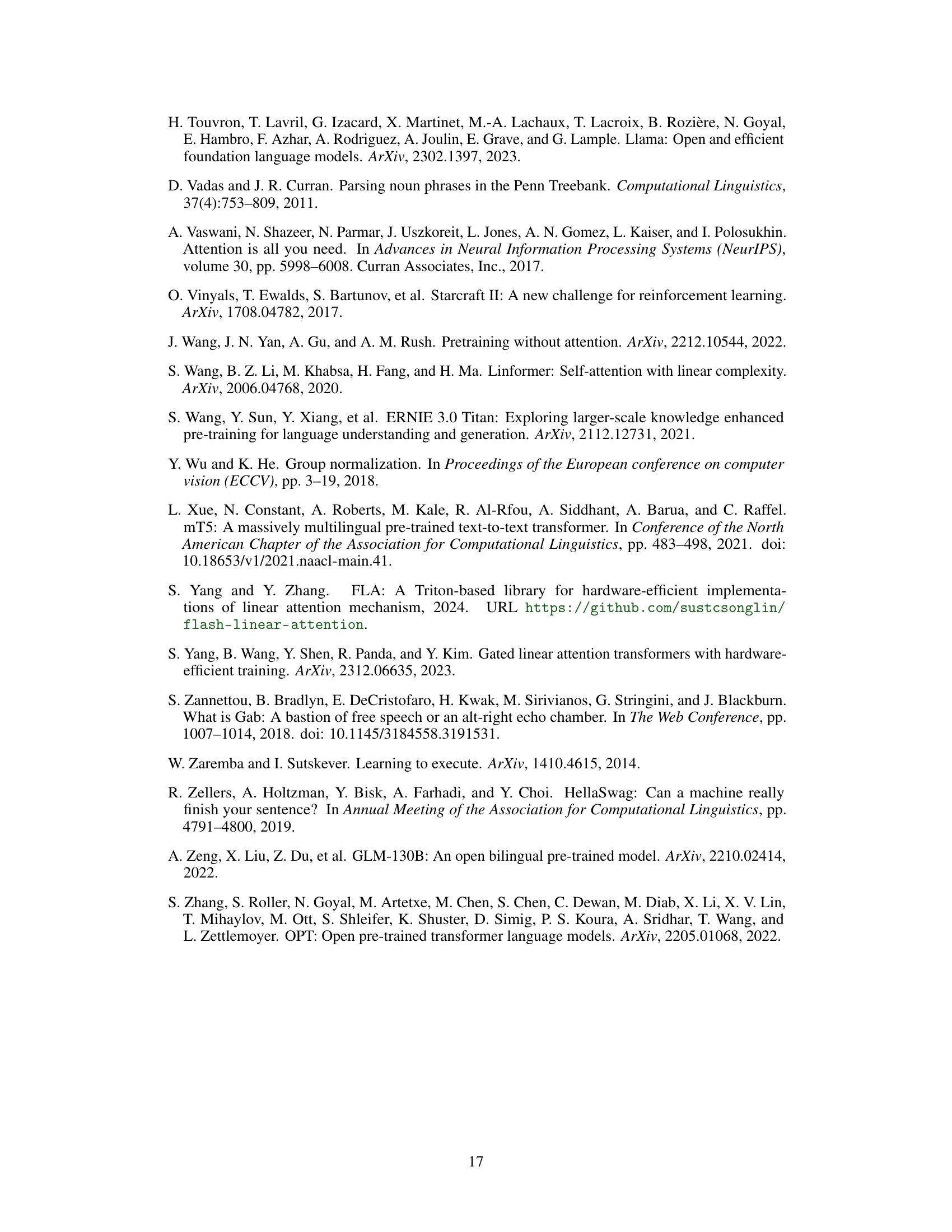

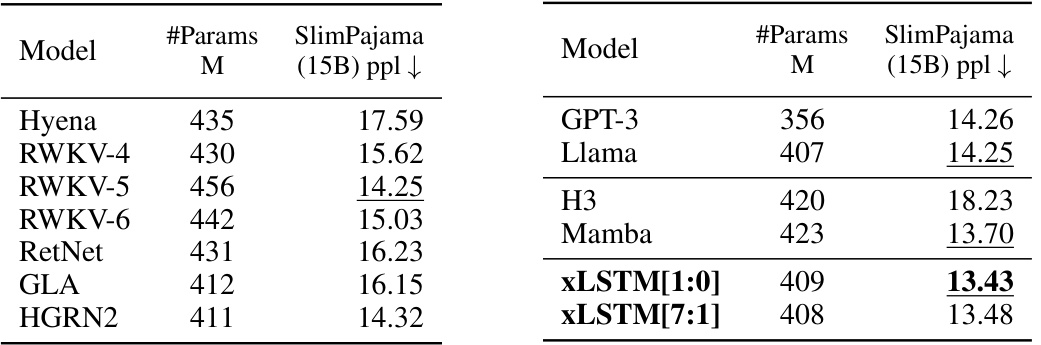

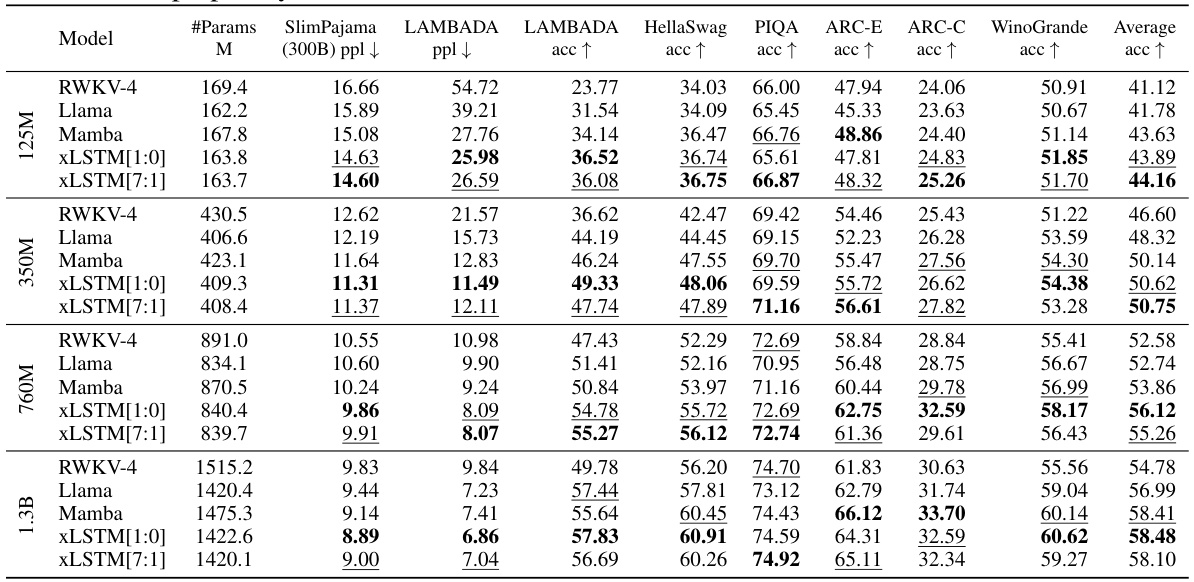

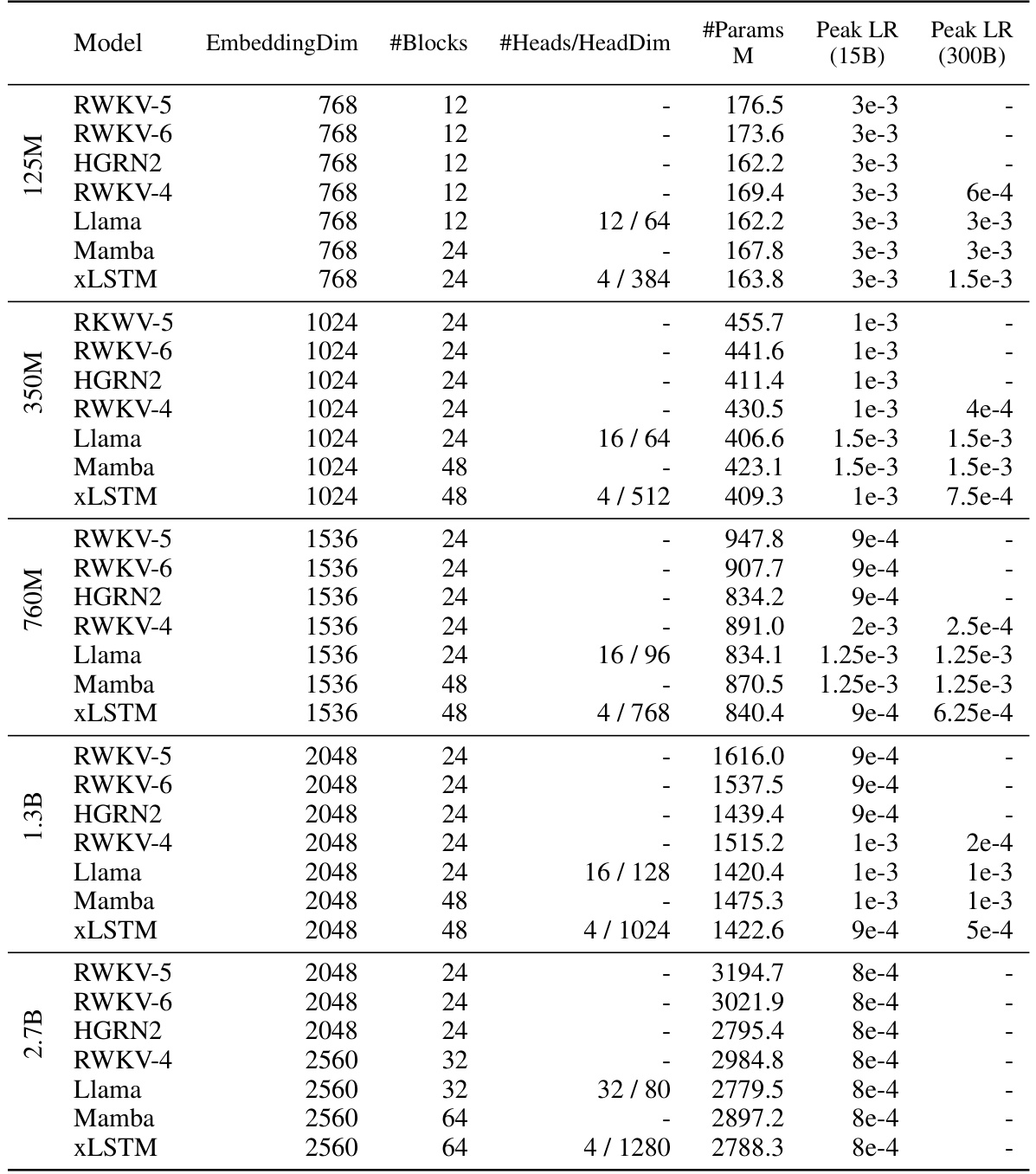

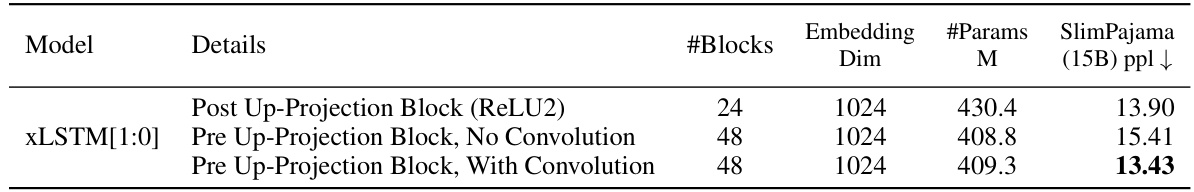

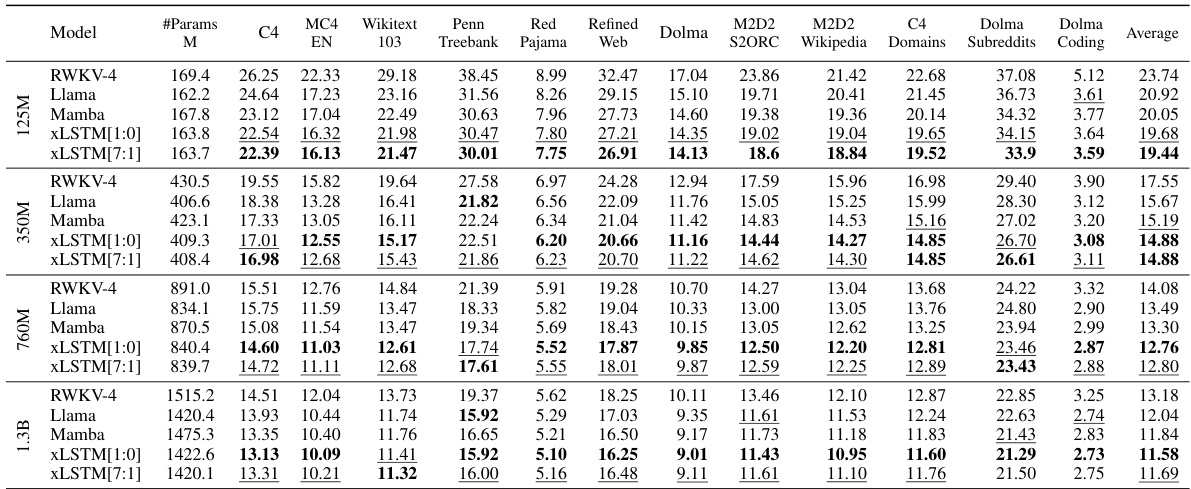

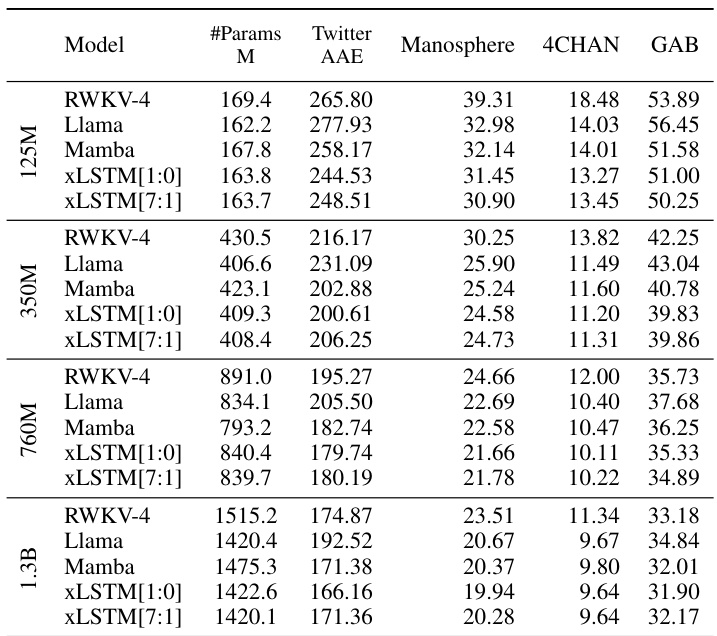

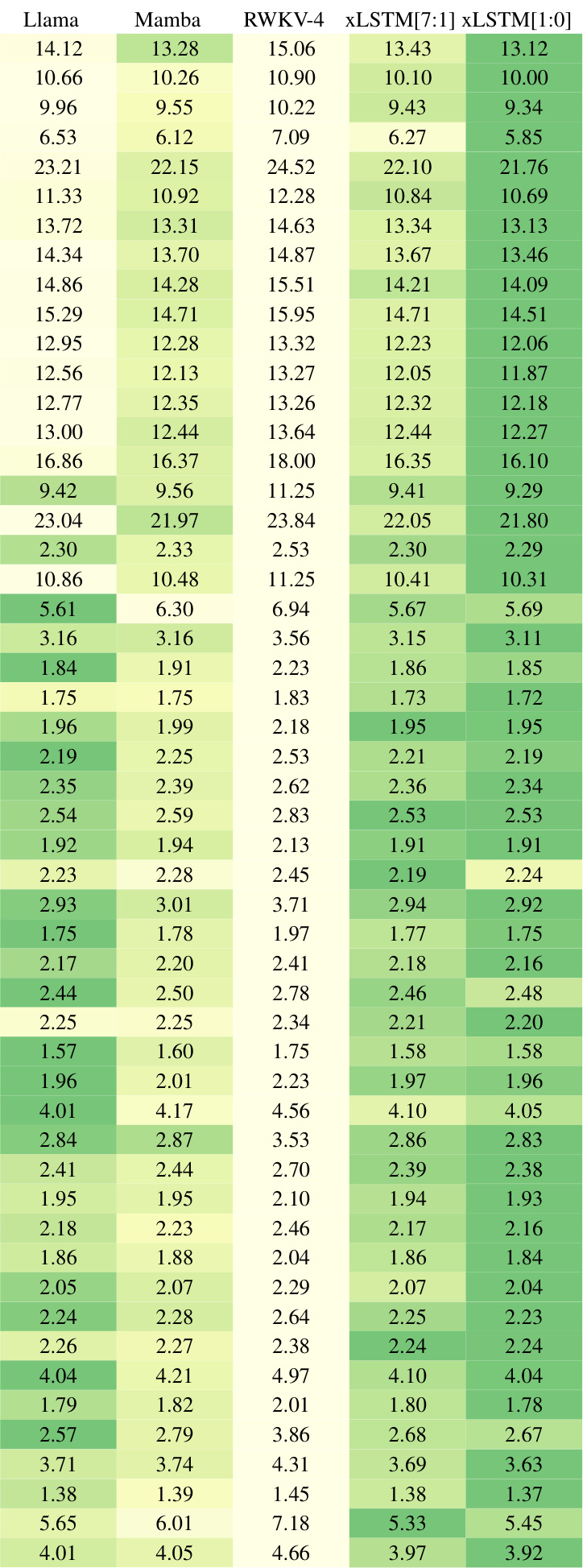

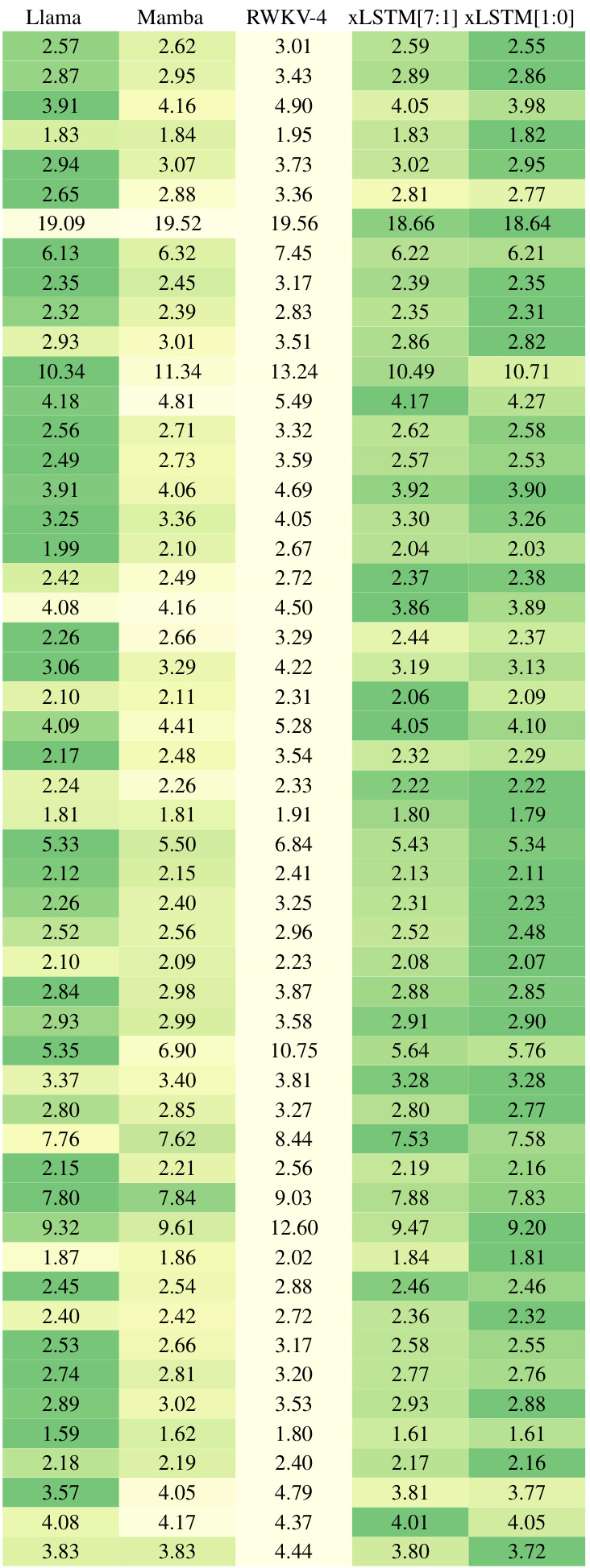

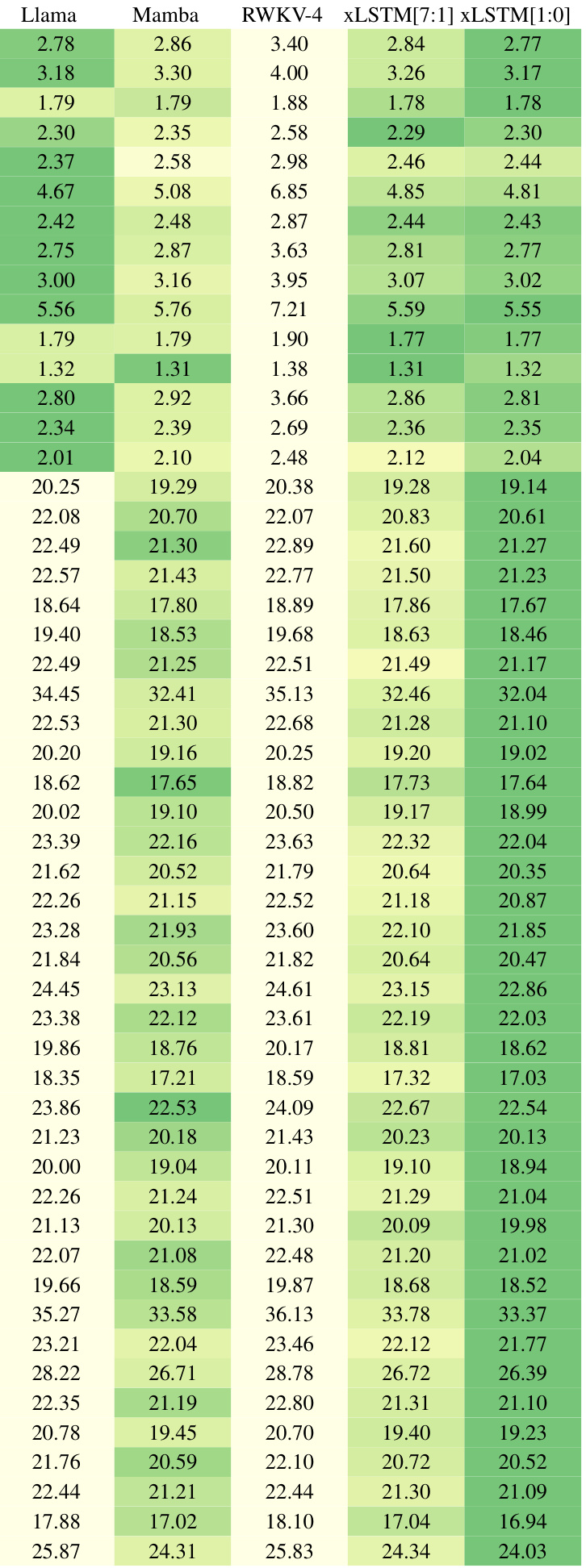

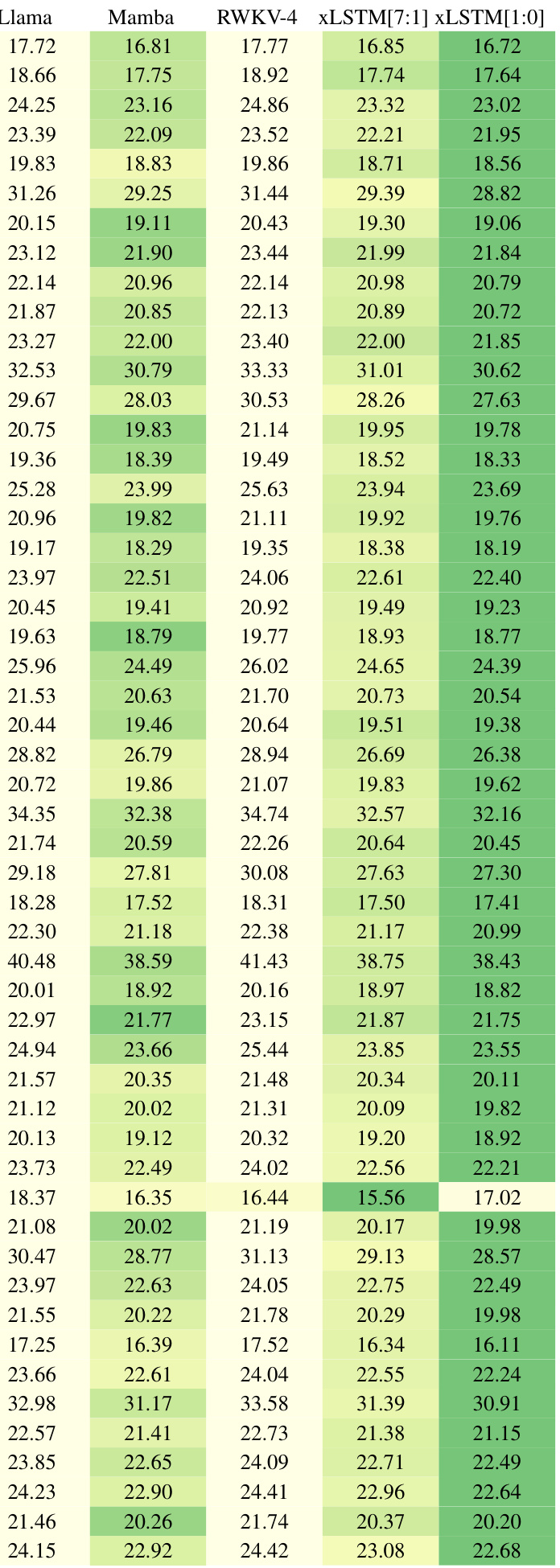

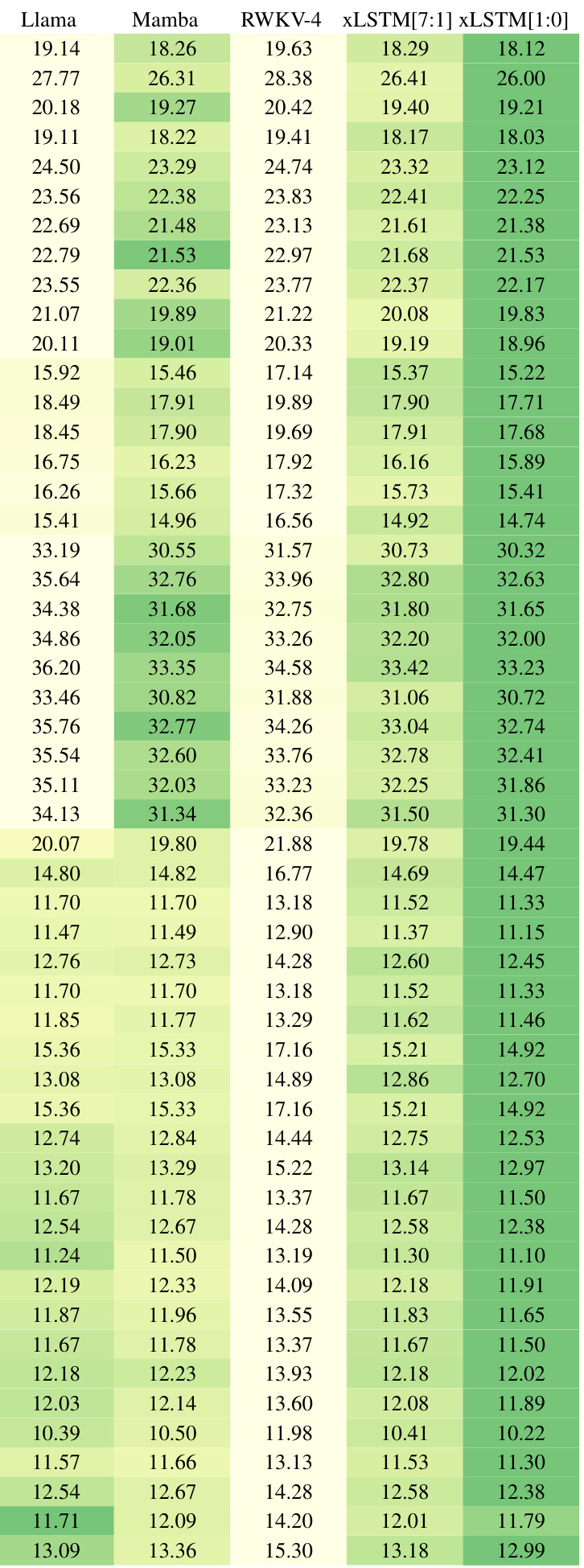

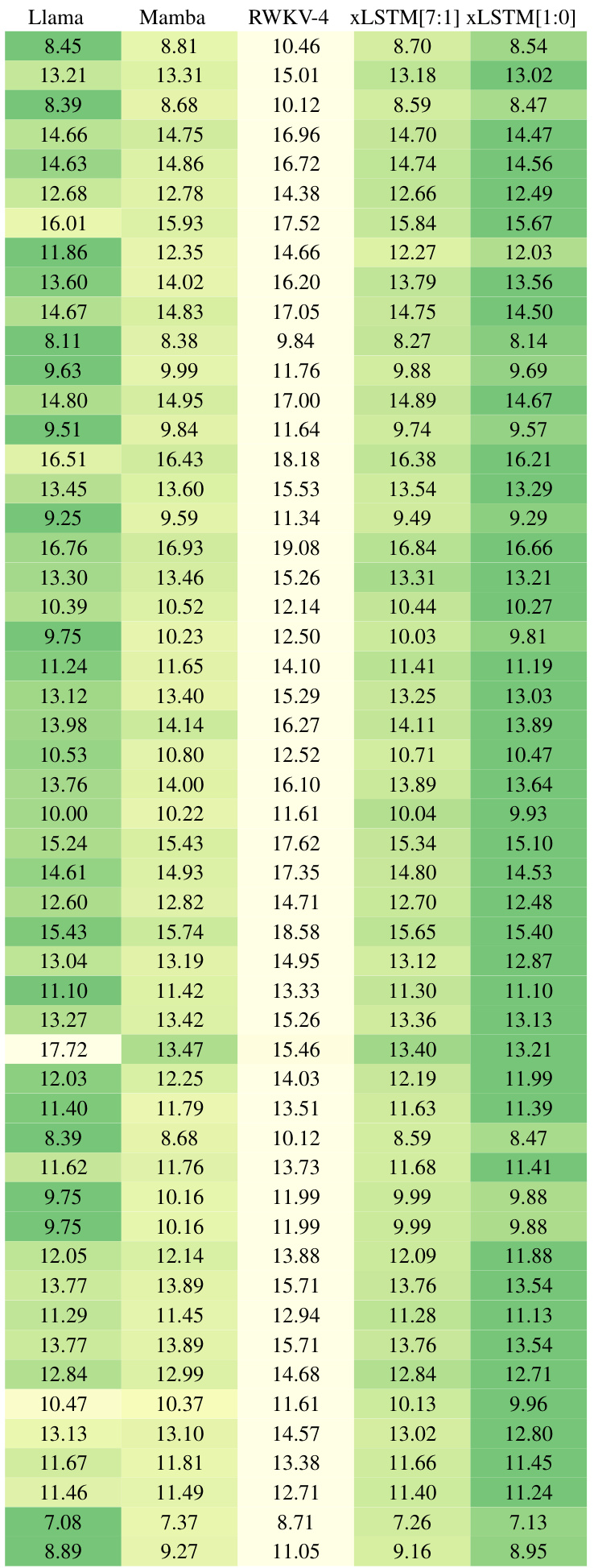

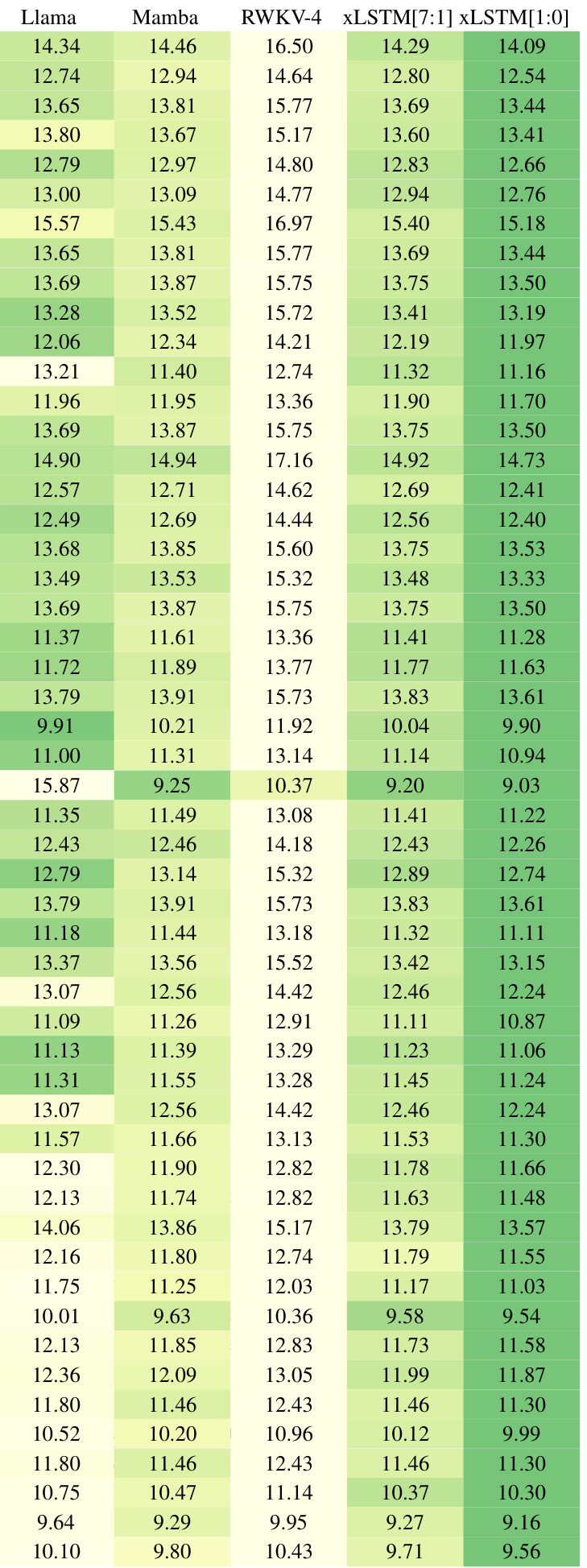

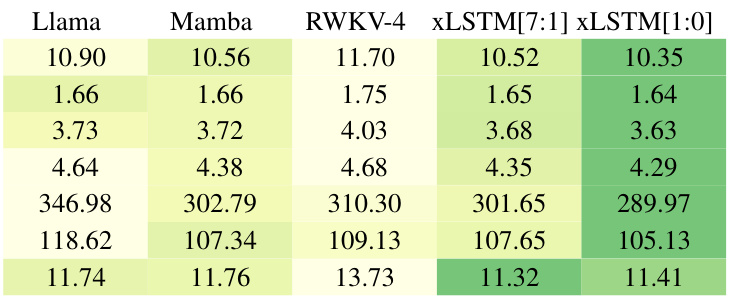

This table presents a comparison of different language models trained on 15 billion tokens from the SlimPajama dataset, evaluating their performance on next-token prediction. The models are categorized into linear Transformers, RNNs, Transformers, and State Space Models (SSMs), with xLSTMs forming a separate category. The table shows the number of parameters for each model, and their respective validation set perplexities. The best performing model in each category is underlined, with the overall best model in bold. Note that the best-performing models in each category are selected for further large language model (LLM) training in Section 4.3.

In-depth insights#

XLSTM: Intro & Background#

An introductory section, “XLSTM: Intro & Background,” would ideally set the stage for a research paper on XLSTM (Extended Long Short-Term Memory) architectures. It should begin by highlighting the limitations of current recurrent neural networks (RNNs) like LSTMs, especially concerning the vanishing gradient problem and difficulties in handling long-range dependencies. The introduction should then motivate the need for XLSTM by emphasizing the superior performance of Transformer networks in large-scale language modeling. It should then introduce XLSTM as a novel architecture designed to address the shortcomings of LSTMs while maintaining some of their advantages. A concise overview of XLSTM’s key innovations, such as exponential gating and modified memory structures (scalar and matrix versions), should be provided to create a clear understanding of its core mechanisms. This section should also offer a brief review of relevant prior research in RNNs and attention mechanisms, showcasing XLSTM’s position within the existing body of knowledge. The background should explain the rationale behind XLSTM’s design choices, particularly how its unique features contribute to improved efficiency and long-range dependency handling compared to state-of-the-art models. Finally, it should end with a clear statement of the paper’s objectives and how XLSTM’s capabilities will be evaluated.

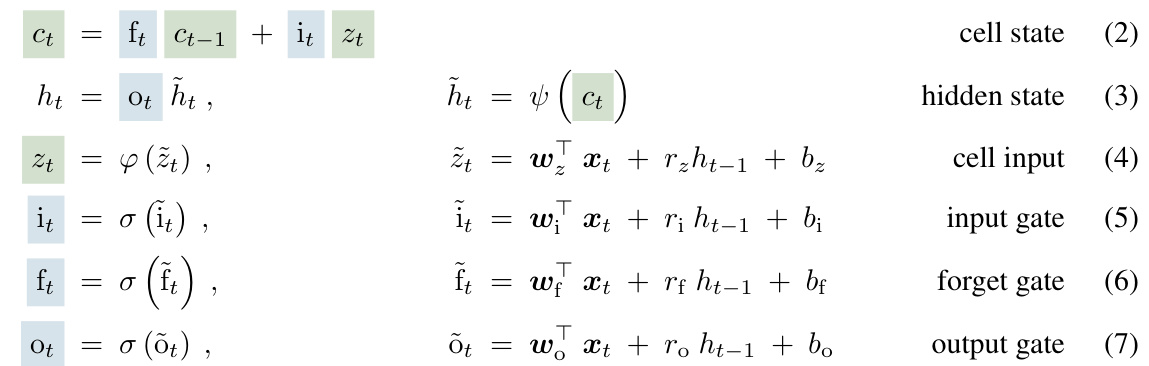

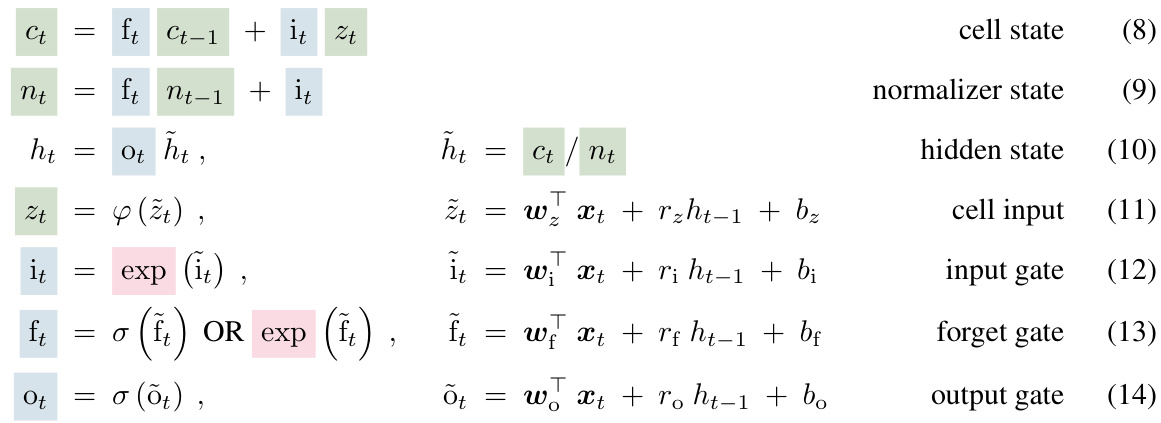

Exponential Gating#

The concept of “Exponential Gating” in the context of recurrent neural networks, particularly LSTMs, offers a compelling approach to address inherent limitations of traditional gating mechanisms. Standard sigmoid gates, due to their bounded nature, can struggle to effectively control information flow over extended sequences. Exponential gating, by using exponential functions, expands the dynamic range of the gate activations, allowing for more nuanced control and better handling of long-range dependencies. This increased expressiveness enables the network to learn more complex patterns and better manage information flow in sequences with varying temporal scales. However, the unbounded nature of exponential functions presents challenges, including potential numerical instability and gradient explosion during training. Thus, employing appropriate normalization and stabilization techniques, such as incorporating a normalizer state or applying clipping mechanisms, is crucial for mitigating these issues and ensuring stable and reliable model training. The effectiveness of exponential gating therefore hinges on a delicate balance between enhanced expressivity and maintaining numerical stability. While it presents a significant improvement over traditional methods, further research and careful implementation strategies are necessary to fully unlock the potential of this technique in diverse machine learning applications.

Novel Memory Designs#

The heading ‘Novel Memory Designs’ suggests a section dedicated to innovative memory architectures for neural networks. This could involve exploring alternatives to traditional recurrent neural network (RNN) memory, such as exploring memory augmentation techniques to improve long-term dependency handling and addressing the vanishing/exploding gradient problems inherent in RNNs. The designs might focus on enhanced storage capacity, potentially using matrices or other higher-dimensional structures to store more information efficiently, and parallel processing capabilities. The discussion may also cover memory access mechanisms, how the network retrieves and utilizes stored information, and strategies for managing information efficiently. Specific architectural changes, such as alternative gating mechanisms or new update rules, could be introduced. The section would likely benchmark the effectiveness of these novel designs against existing memory structures. Overall, it’s expected that ‘Novel Memory Designs’ presents significant improvements in network performance and learning capabilities.

xLSTM Architecture#

The xLSTM architecture section would detail how individual xLSTM blocks, each incorporating either an sLSTM or mLSTM, are combined to form complete models. It would likely discuss the use of residual connections to facilitate efficient training and gradient flow, enabling the stacking of multiple blocks to handle long sequences. Layer normalization is another critical element, likely described as applied before each block, and potentially further details about its implementation (e.g., pre- or post-LayerNorm). The architecture’s design would be explained in the context of achieving performance and scaling comparable to state-of-the-art Transformers. Furthermore, the section would likely delve into the computational complexity and memory requirements of the architecture, contrasting it to traditional Transformers and highlighting the xLSTM’s advantages in terms of linear scaling. Finally, the choices of sLSTM and mLSTM in specific positions within the architecture would be motivated, potentially linking the selection to the type of tasks or sequence properties best handled by each variant (e.g., using sLSTM for tasks requiring memory mixing and mLSTM for those allowing parallelization).

Limitations & Future Work#

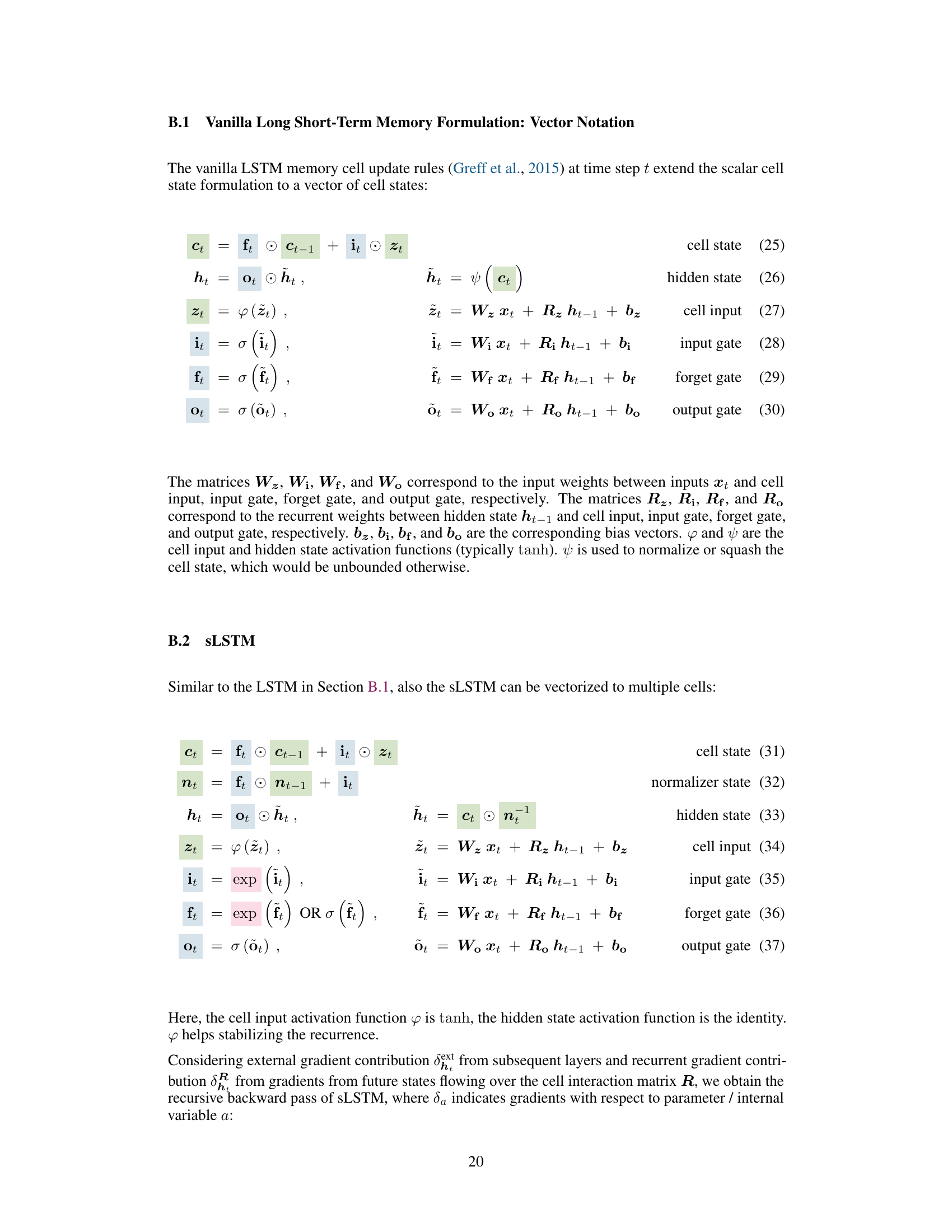

A thoughtful analysis of the ‘Limitations & Future Work’ section of a research paper would delve into the shortcomings of the presented approach, acknowledging limitations in methodology, scope, or generalizability. It would highlight areas where the research could be extended or improved. Key limitations might include the dataset’s size or bias, the model’s performance on specific tasks, the computational cost, or the model’s susceptibility to adversarial attacks. Future work could involve addressing these limitations through larger datasets, exploring alternative architectures, optimizing the model’s training process, or testing the robustness against different attacks. The discussion should also propose novel applications of the research, such as integrating it with other systems or applying it to different domains. A strong conclusion would emphasize the potential impact of future work on the field, while acknowledging the remaining challenges and opportunities.

More visual insights#

More on figures

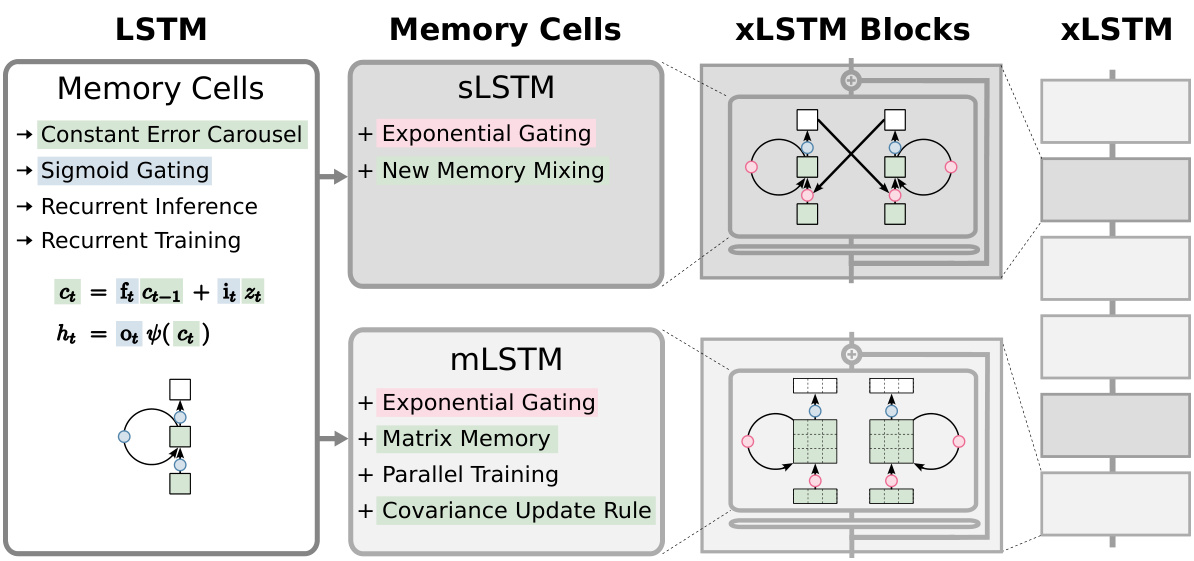

This figure illustrates the evolution of the LSTM architecture from the original version to the extended xLSTM. It shows the components added at each stage: exponential gating, new memory mixing in sLSTM, parallel processing capabilities of mLSTM with its matrix memory and covariance update, and finally, the combination of these into residual xLSTM blocks which can be stacked to create xLSTM architectures.

This figure illustrates the evolution of LSTM to xLSTM. It starts with the original LSTM cell, highlighting its core components: constant error carousel and gating. Then, it introduces the two new variants: sLSTM and mLSTM, each with its unique improvements. sLSTM incorporates exponential gating and a new memory mixing technique for enhanced revisability. mLSTM features exponential gating, matrix memory, and a covariance update rule for parallelization. The figure then shows how both sLSTM and mLSTM are integrated into residual blocks to form xLSTM blocks, which can then be stacked to create an xLSTM architecture.

This figure illustrates the evolution of LSTM to xLSTM. It starts with the original LSTM cell and shows how it’s extended by introducing exponential gating and new memory structures (sLSTM and mLSTM). The figure highlights the key differences between the original LSTM, sLSTM, and mLSTM, and how these components are integrated into xLSTM blocks and finally stacked into the xLSTM architecture.

This figure illustrates two limitations of LSTMs. The left panel shows that LSTMs struggle to update their memory when encountering a more similar vector later in a sequence, resulting in higher MSE in nearest neighbor search. The right panel shows that LSTMs perform poorly on predicting rare tokens compared to Transformers, suggesting limitations in their storage capacity. The authors’ proposed XLSTM model addresses these issues with improved memory mixing (left) and enhanced storage capacity (right).

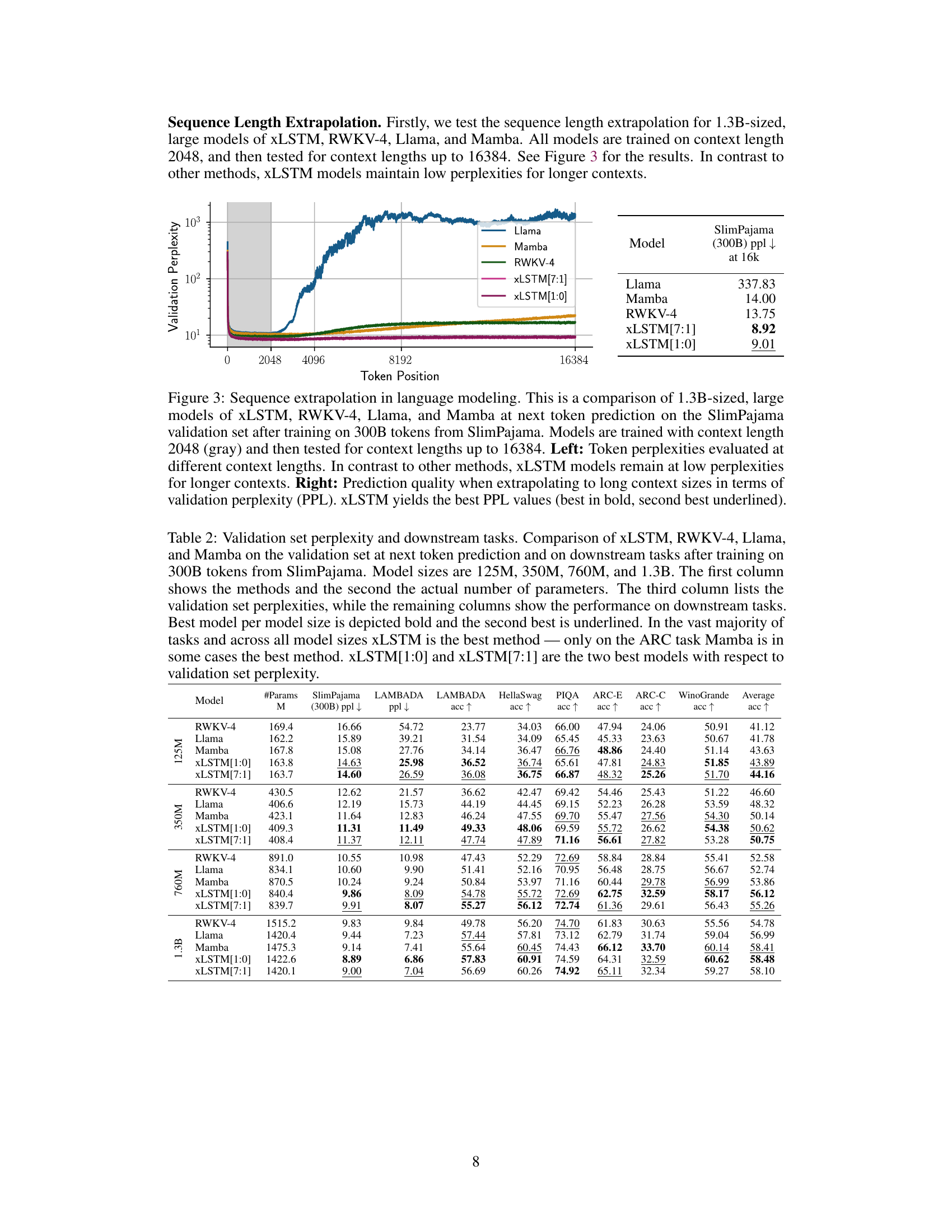

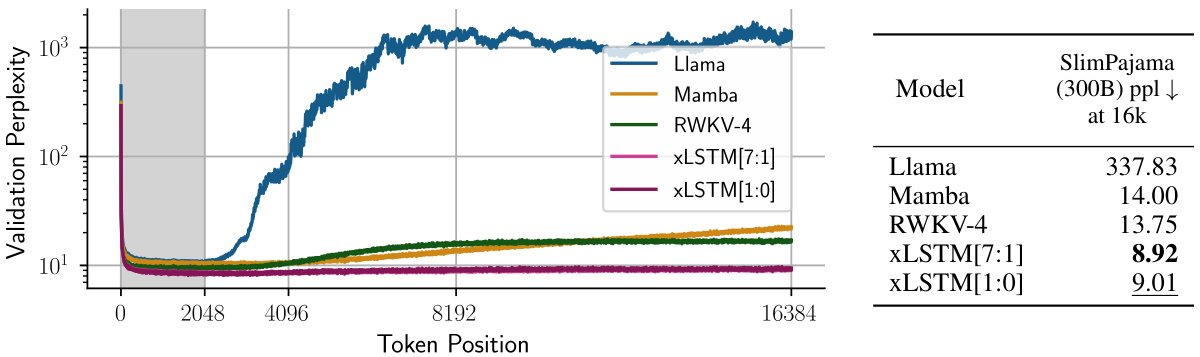

This figure compares the performance of xLSTM, RWKV-4, Llama, and Mamba models on a sequence extrapolation task in language modeling. The models were initially trained on sequences of length 2048. The left panel shows how perplexity changes as the models are tested on sequences of increasing length (up to 16384). The right panel summarizes this by showing the final validation perplexity at the longest sequence length (16384). The results demonstrate that xLSTM models maintain significantly lower perplexity compared to other models when tested on longer sequences.

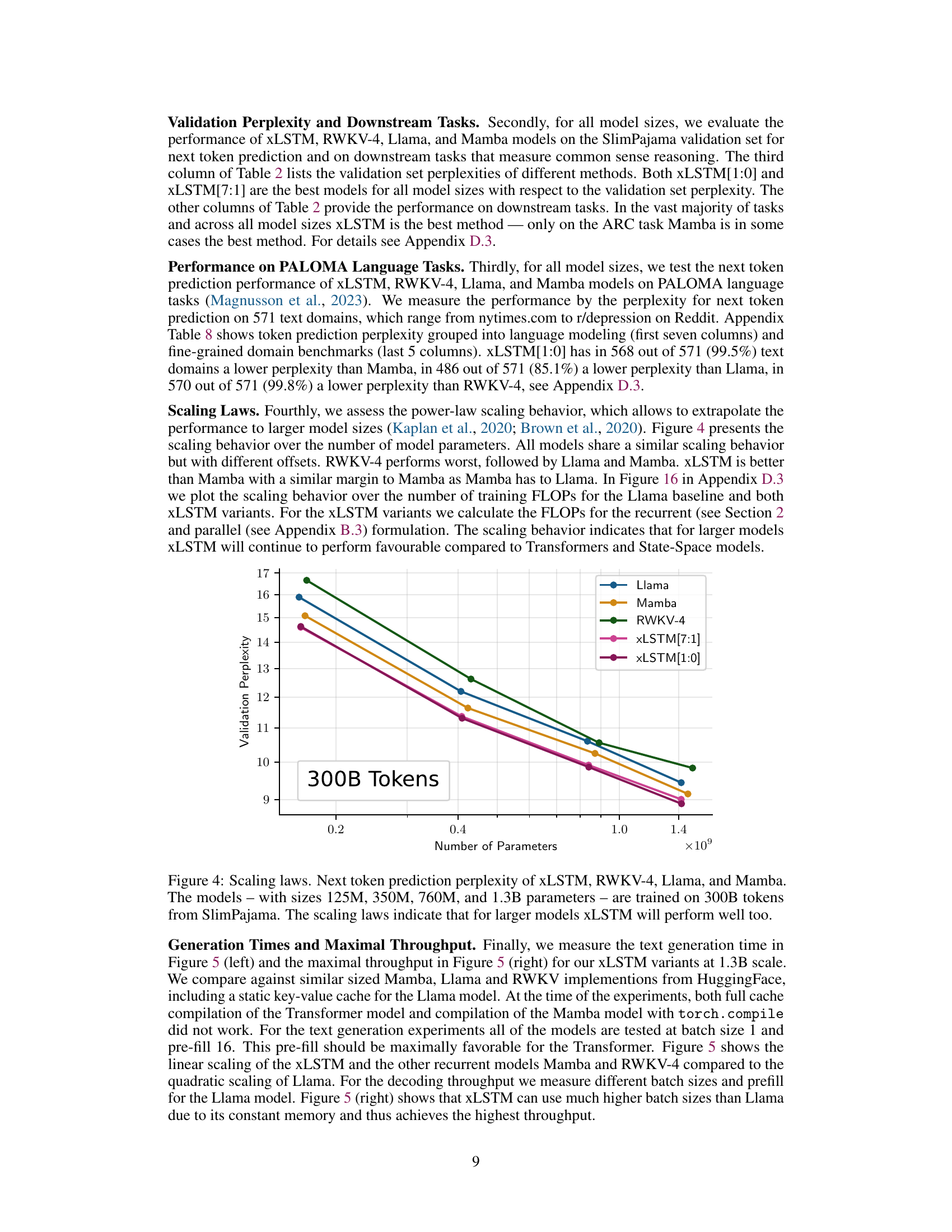

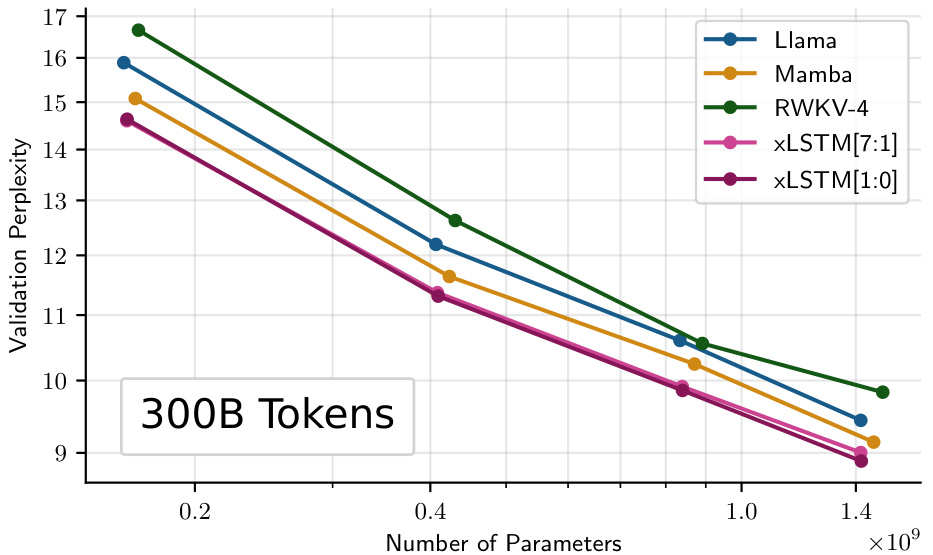

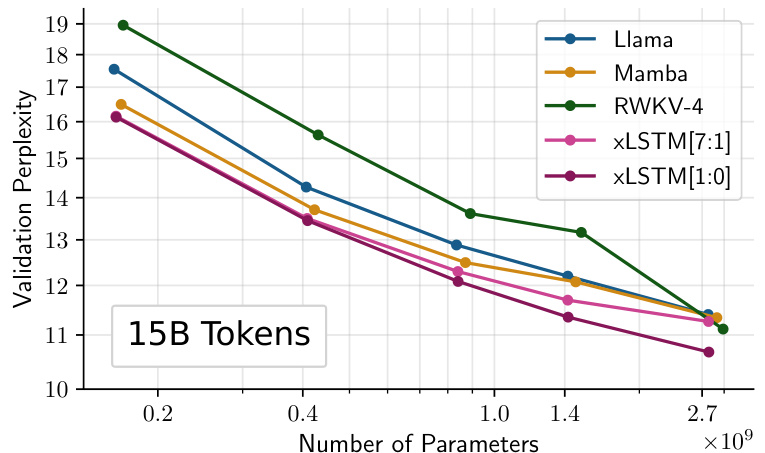

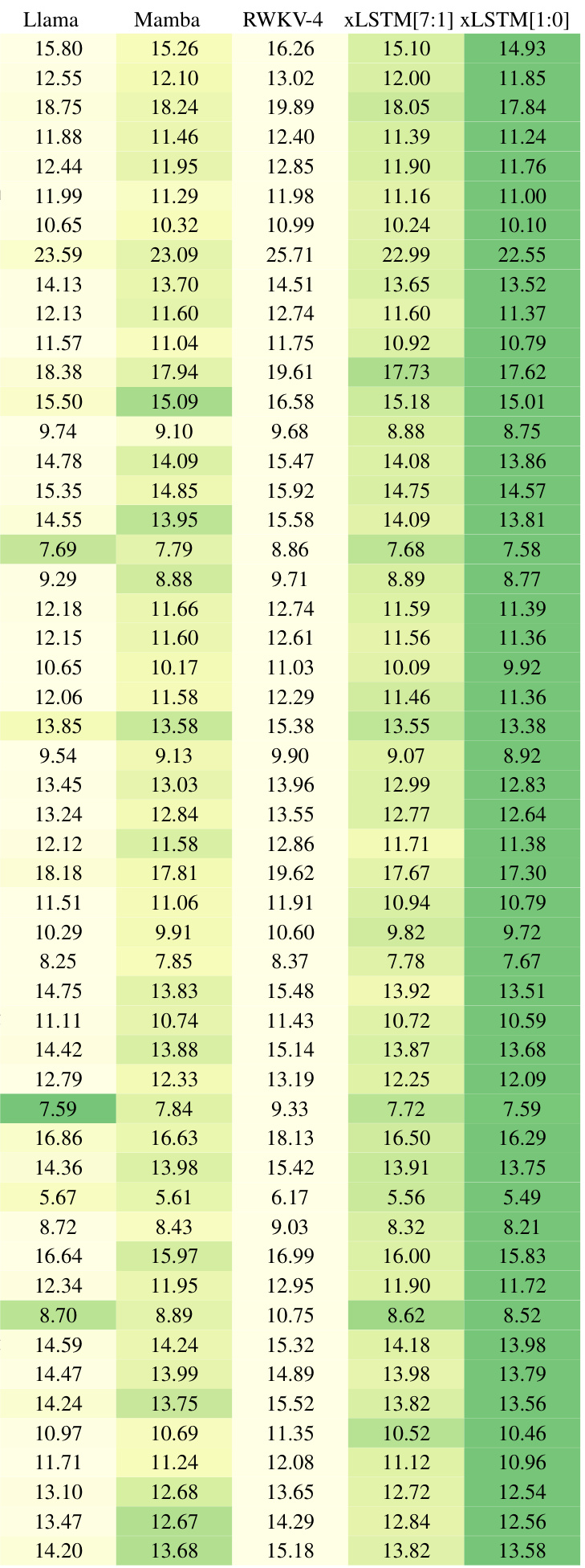

This figure compares the performance of different language models on a next-token prediction task using the SlimPajama dataset (15B tokens). It shows the validation perplexity as a function of the model size (number of parameters) for several models, including Llama, Mamba, RWKV-4, XLSTM[7:1], and XLSTM[1:0]. The results indicate that XLSTM models generally outperform the others, achieving lower perplexity scores across different model sizes. A slight performance dip is observed for XLSTM[7:1] at the largest model size, which is attributed to slower initial training convergence.

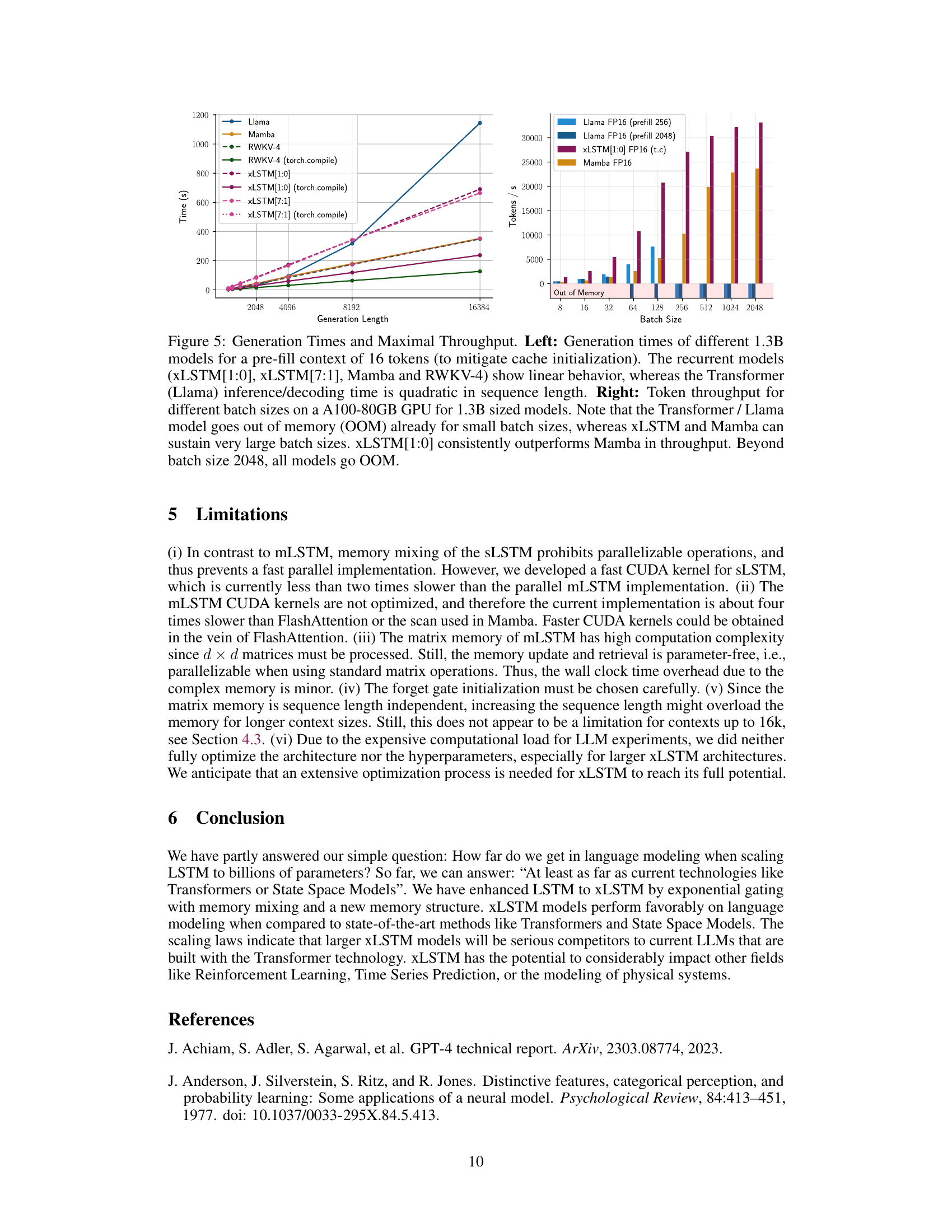

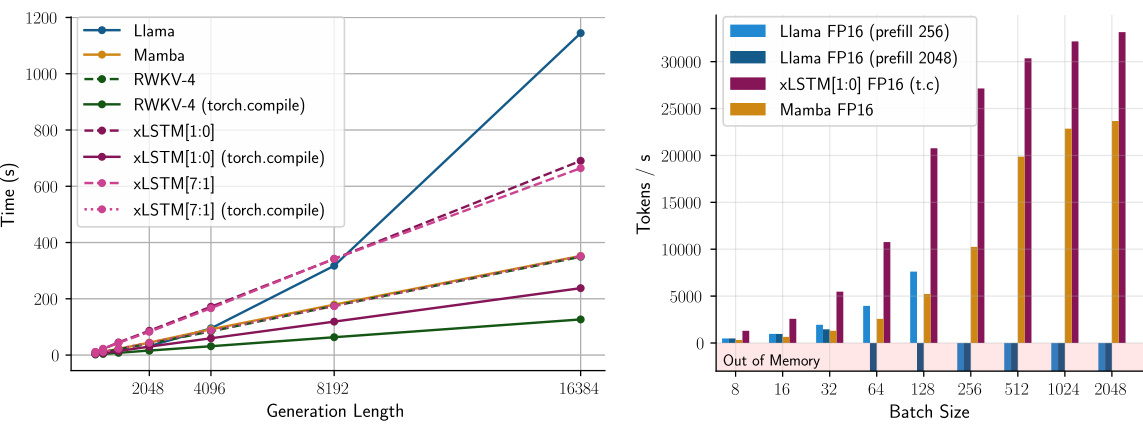

This figure compares the performance of different 1.3B large language models in terms of generation time and maximal throughput. The left panel shows that recurrent models exhibit linear scaling with generation length, unlike the Transformer model which shows quadratic scaling. The right panel demonstrates the throughput of the models at various batch sizes. It highlights that xLSTM[1:0] achieves the highest throughput at large batch sizes, while the Transformer model runs out of memory at relatively small batch sizes.

This figure illustrates the evolution of the LSTM architecture to the xLSTM architecture. It starts with the original LSTM cell, showing its core components such as the constant error carousel and sigmoid gates. It then introduces two new variants: sLSTM and mLSTM, which incorporate exponential gating and modified memory structures. The sLSTM introduces a new memory mixing technique, while the mLSTM enables parallelization using a matrix memory and a covariance update rule. Finally, it shows how these new LSTM variants are integrated into residual blocks to form xLSTM blocks, which are then stacked to create the final xLSTM architecture.

This figure illustrates the evolution of LSTM architectures from the original LSTM to the extended LSTM (xLSTM). It starts with the original LSTM cell, highlighting its constant error carousel and gating mechanisms. Then it introduces two new variations: sLSTM and mLSTM. sLSTM incorporates exponential gating and a new memory mixing technique, while mLSTM is fully parallelizable due to the use of a matrix memory and covariance update rule. The figure shows how these new LSTM variants are integrated into residual blocks to form xLSTM blocks, which are then stacked to create the final xLSTM architecture.

This figure illustrates the evolution of LSTM to xLSTM. It starts with the original LSTM cell, highlighting its core components like the constant error carousel and gating mechanisms. Then, it introduces two novel variations: sLSTM (with scalar memory and exponential gating) and mLSTM (with matrix memory, exponential gating, and a covariance update rule). Finally, it shows how these new LSTM variants are integrated into residual blocks (xLSTM blocks) and stacked to form the complete xLSTM architecture.

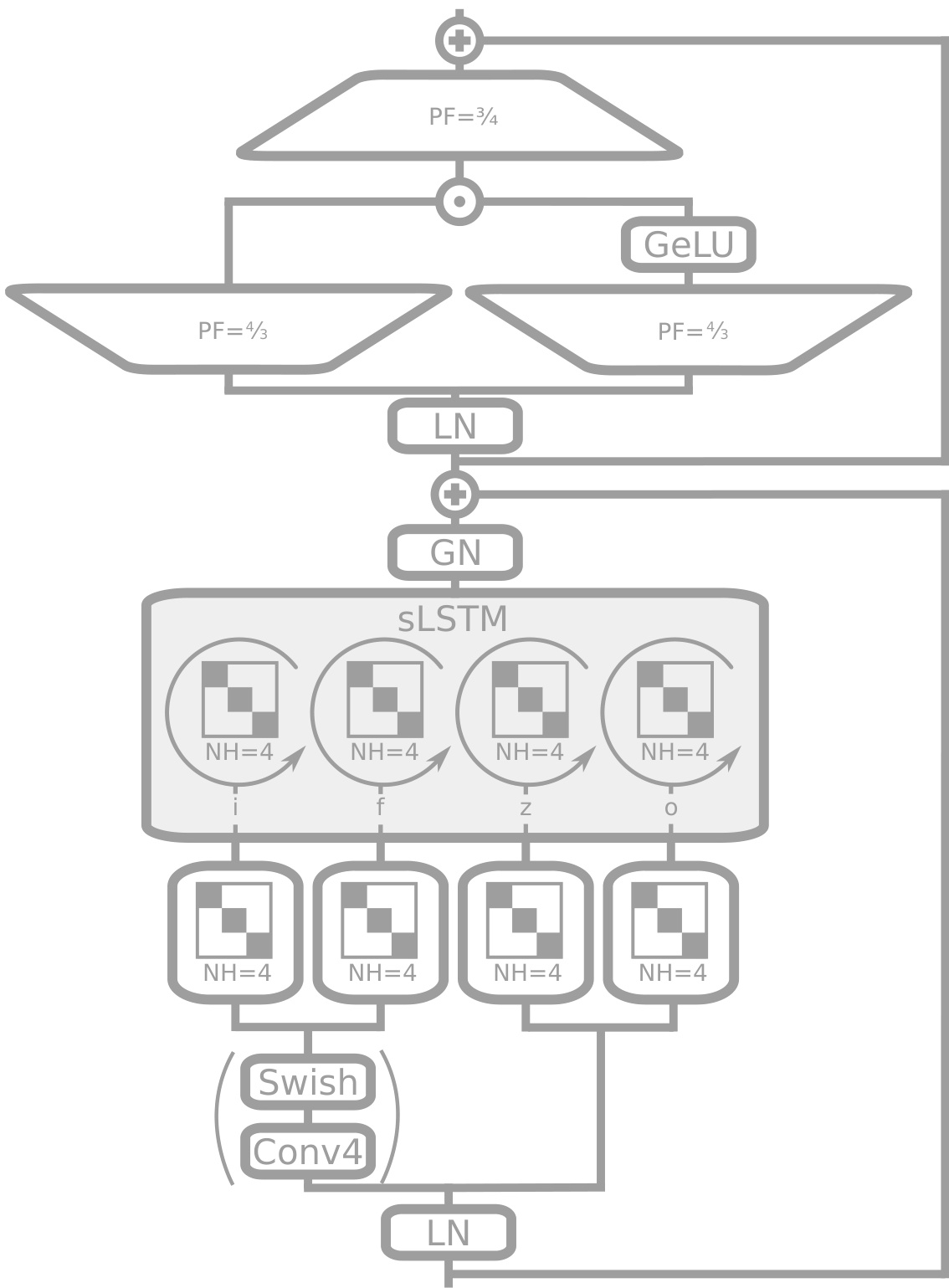

This figure shows the architecture of an sLSTM block, a key component of the XLSTM model. It illustrates how the input data is processed through a causal convolution (optional), a block-diagonal linear layer representing four heads, Group Normalization, and a gated MLP before being outputted. This block uses pre-LayerNorm residual architecture and exponential gating.

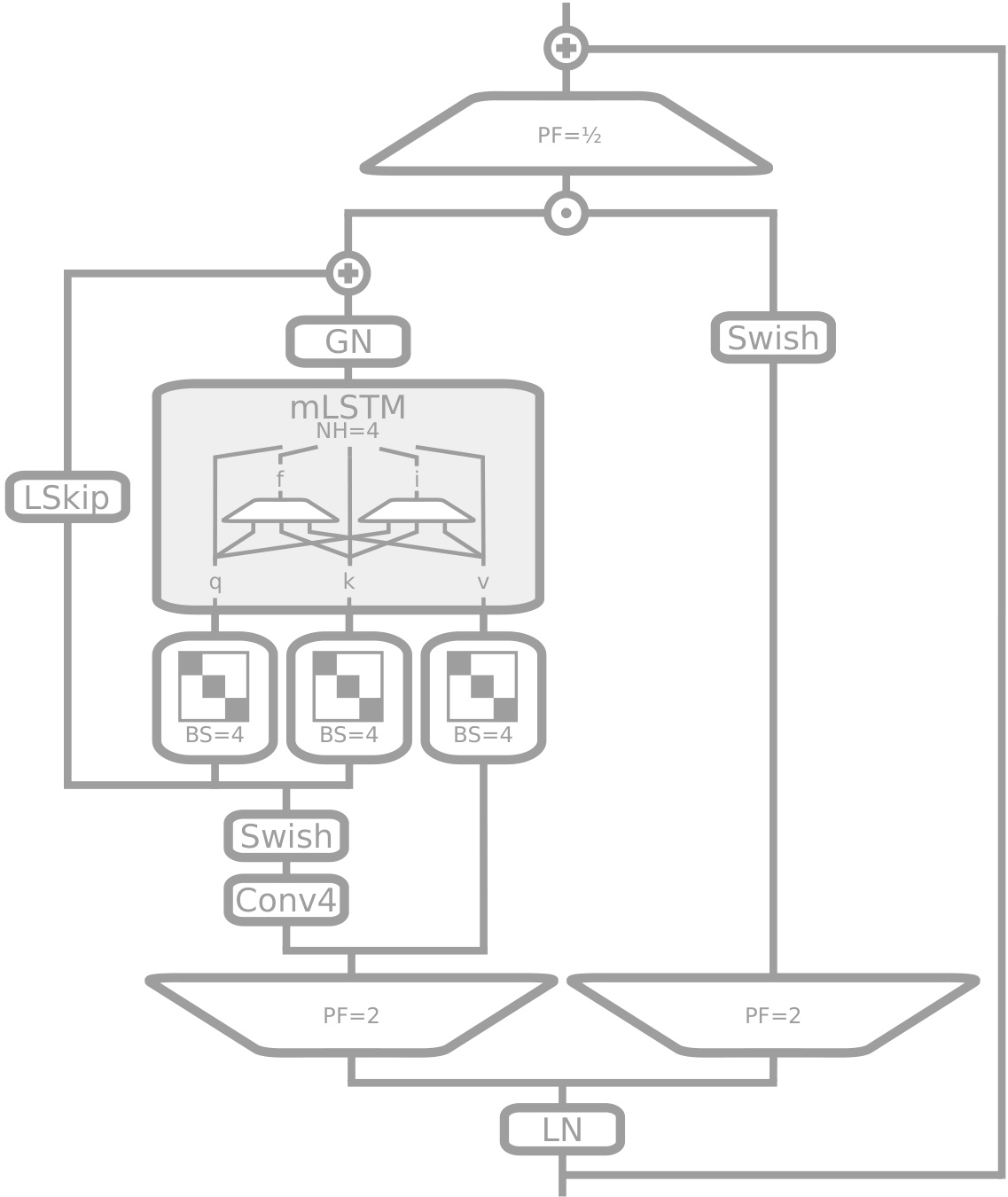

This figure depicts the architecture of an mLSTM block, a key component of the XLSTM model. It showcases the pre-up-projection design where the input is first linearly transformed to a higher dimension before being processed by the mLSTM cell. The mLSTM cell utilizes a matrix memory and a covariance update rule. Key features illustrated include the causal convolution, learnable skip connections, Group Normalization, and gating mechanisms.

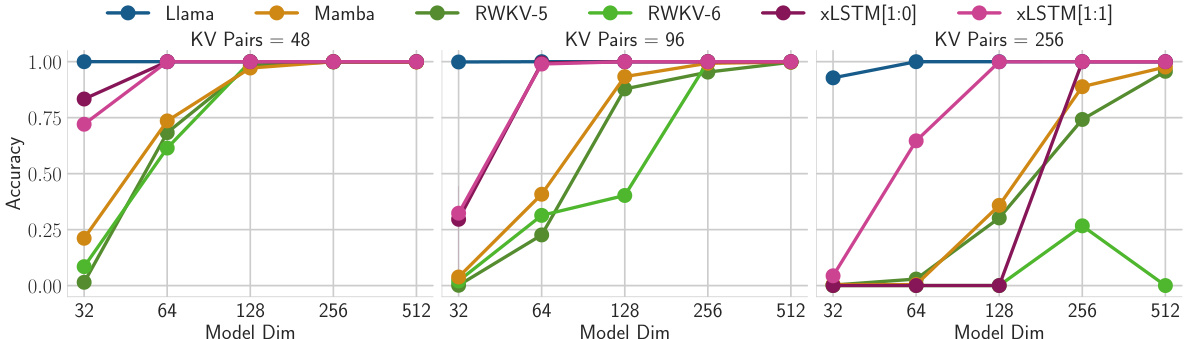

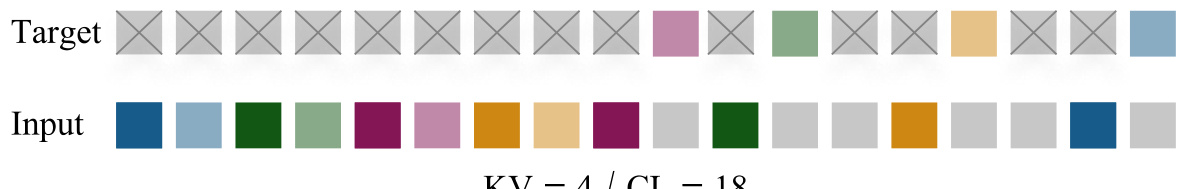

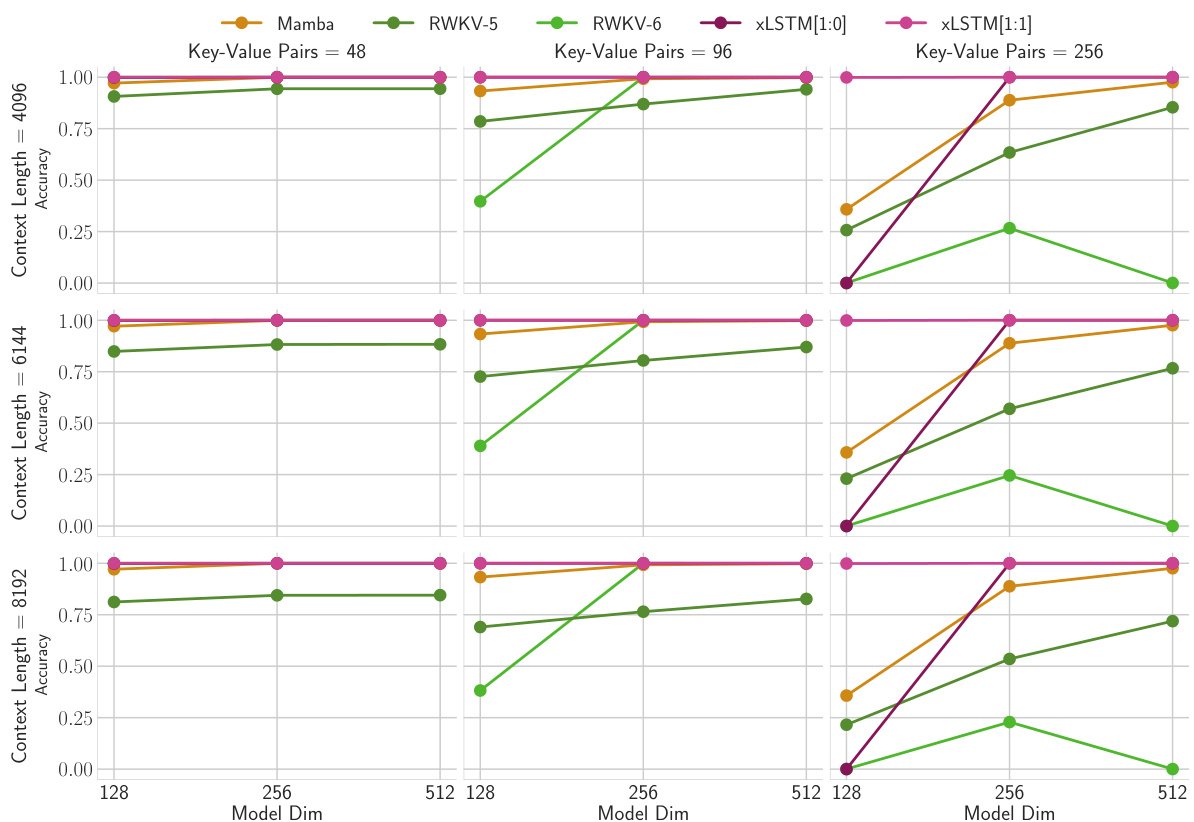

This figure illustrates the Multi-Query Associative Recall (MQAR) task. The top row shows the ’target’ sequence, where colored squares represent key-value pairs. The bottom row displays the ‘input’ sequence that the model receives, where the color coding corresponds to the key-value pairs in the target sequence. The model needs to predict the values (colored squares) in the target sequence based on the order of keys presented in the input sequence. The task’s complexity is controlled by varying the number of key-value pairs and the length of the input sequence.

This figure shows two graphs illustrating the limitations of LSTMs. The left graph shows that LSTMs struggle with the Nearest Neighbor Search problem because they cannot easily revise a stored value when a more similar vector is encountered. The right graph shows that LSTMs perform poorly on predicting rare tokens in the Wikitext-103 dataset due to their limited storage capacity. The figure highlights that the proposed XLSTM model addresses these limitations through exponential gating and a matrix memory.

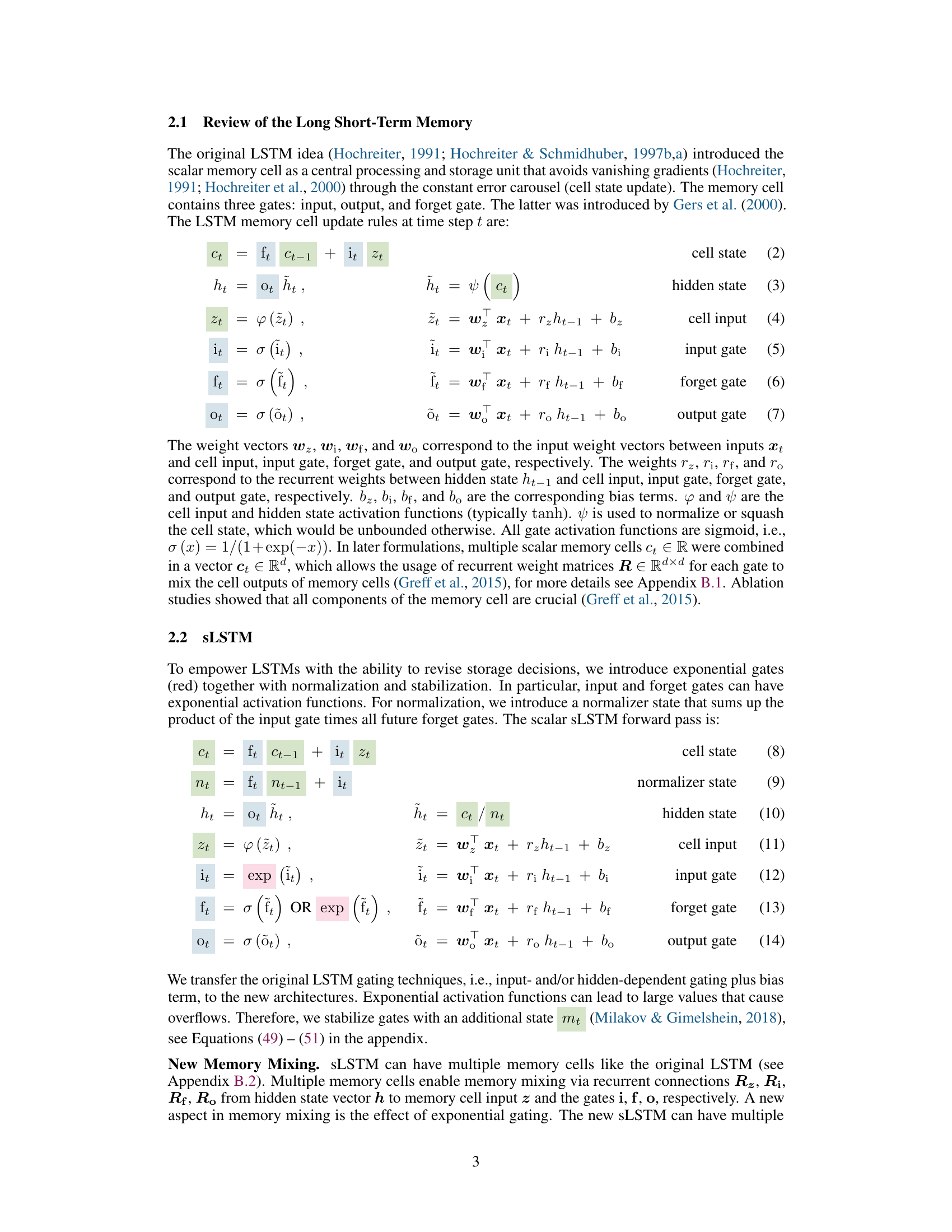

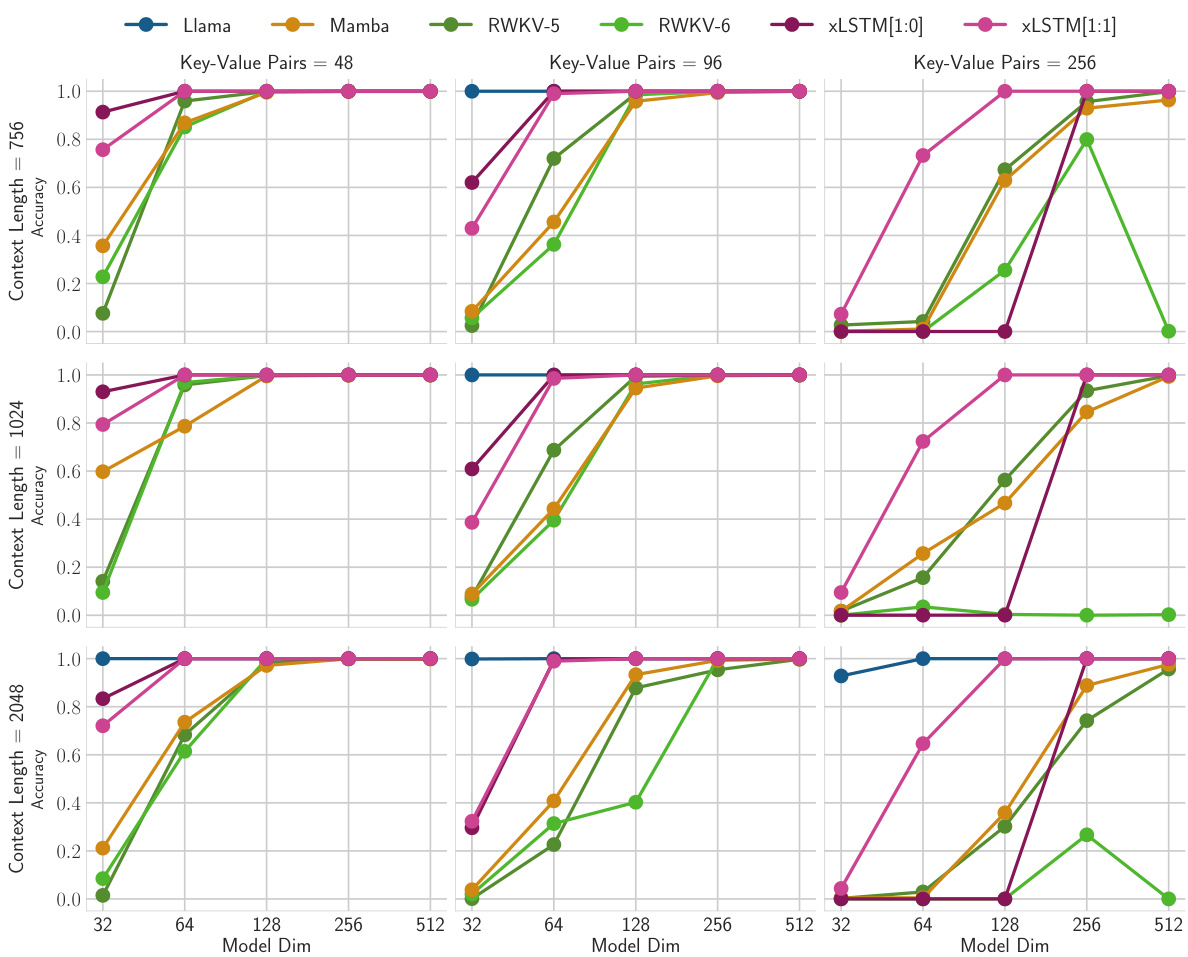

This figure shows the results of the second Multi-Query Associative Recall (MQAR) experiment. It explores how the accuracy of various models changes as the context length and the number of key-value pairs increase. The x-axis represents the model size (dimension), while the y-axis shows the accuracy achieved on the validation set. The different columns and rows represent variations in the number of key-value pairs and context lengths respectively.

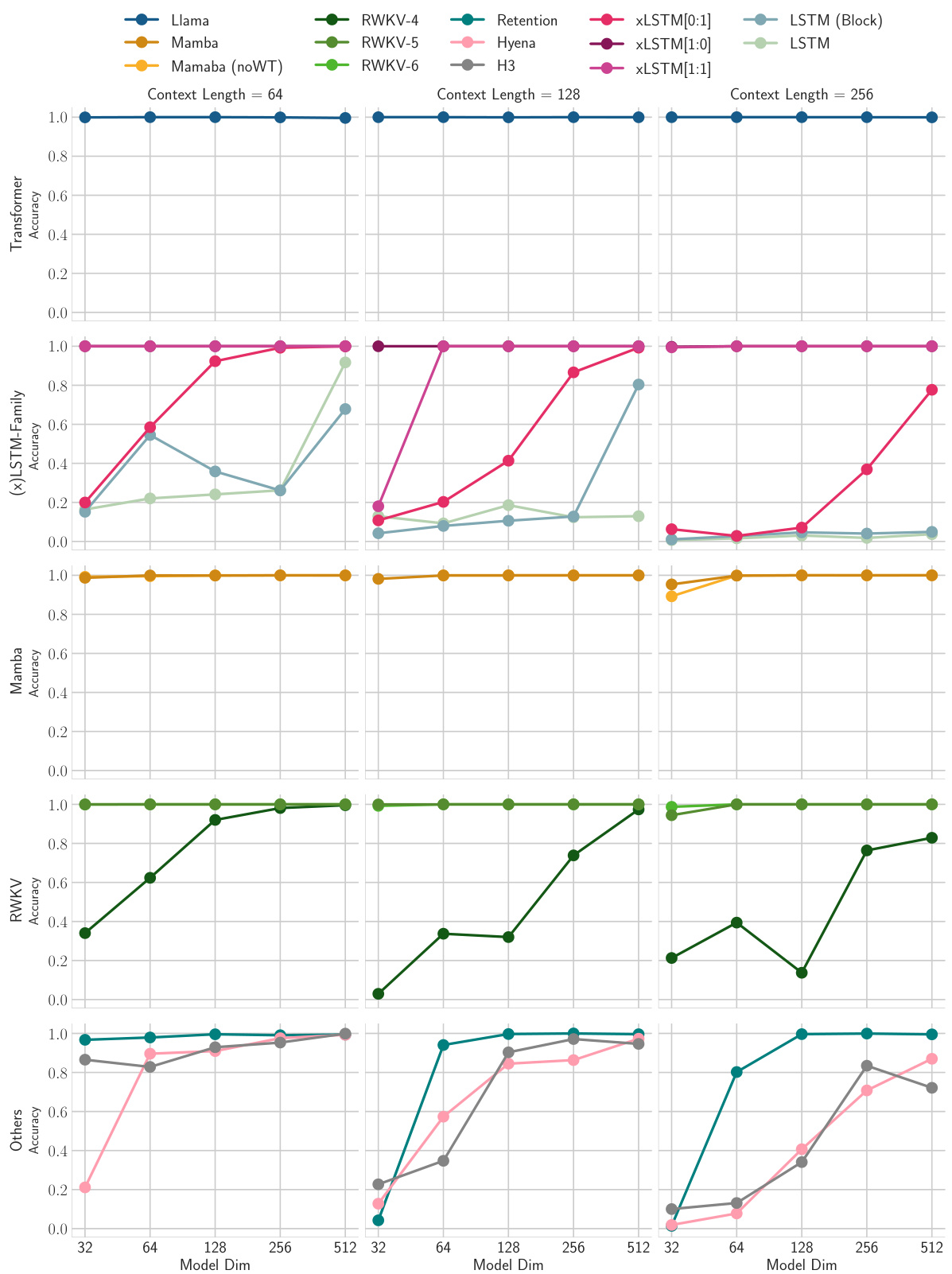

This figure shows the results of the first Multi-Query Associative Recall (MQAR) experiment. The experiment tested various models’ ability to perform associative recall with different levels of difficulty. Difficulty was manipulated by varying the context length (64, 128, 256) and the number of key-value pairs that needed to be memorized (4, 8, 16). The x-axis represents the model size (model dimension), while the y-axis indicates the validation accuracy. The plot is organized to group related models (e.g., Transformers, RNNs, and xLSTMs) for easier comparison.

This figure shows the performance comparison of different language models trained on 15 billion tokens from the SlimPajama dataset. The models are compared based on their validation perplexity, which measures how well the models predict the next token in a sequence. The models included in the comparison are Llama, Mamba, RWKV-4, xLSTM[7:1], and xLSTM[1:0]. The x-axis represents the number of parameters in each model, while the y-axis shows the validation perplexity. The results indicate that xLSTM models generally outperform other models across various parameter scales, demonstrating superior performance in language modeling.

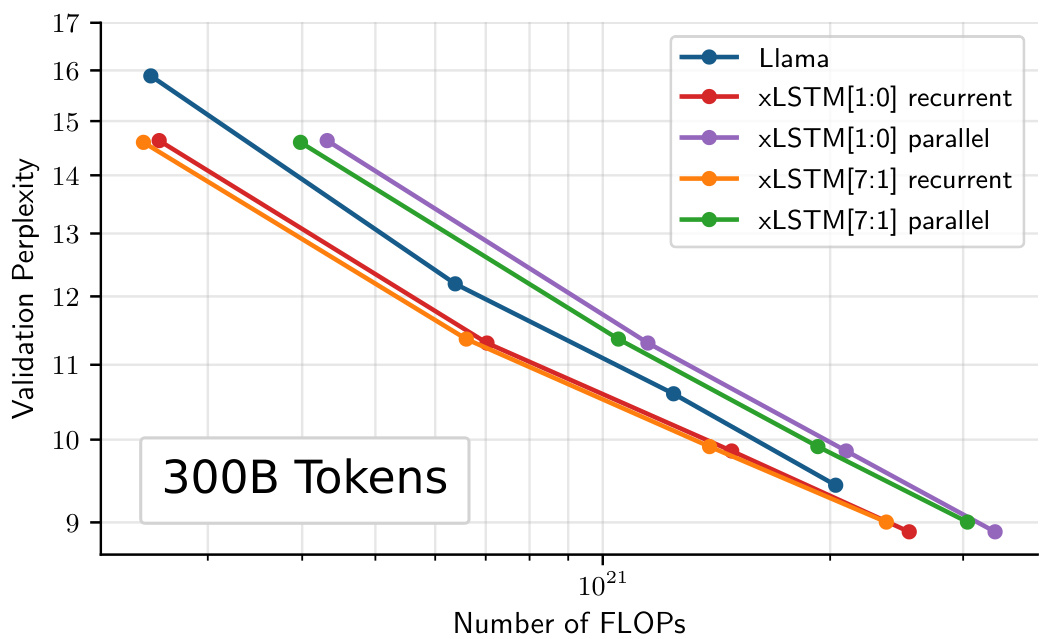

This figure shows the scaling behavior of Llama, and two versions of XLSTM (one with only mLSTM blocks and another with a mix of sLSTM and mLSTM blocks) as the number of training FLOPs increases. The models were trained on 300B tokens with a context length of 2048. The plot displays validation perplexity on the y-axis and the number of FLOPs on the x-axis. The results suggest how the model’s performance (perplexity) changes with the increasing computational cost. Different lines represent the recurrent and parallel versions of the XLSTM models, showcasing the trade-off between performance and parallelization.

More on tables

This table presents the results of comparing various language models on a next-token prediction task using the SlimPajama dataset. It shows the validation perplexity achieved by each model. Models are categorized into linear Transformers, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Transformers, and State Space Models (SSMs). The best-performing model in each category and the overall best-performing model are highlighted. The table also indicates that the best performing models from each category were selected for further large language model training in a subsequent section.

This table compares the performance of various language models on a next-token prediction task. Models are categorized into linear Transformers, RNNs, Transformers, and State Space Models (SSMs). The table shows the number of parameters and the validation perplexity for each model. The best-performing model in each category is underlined, and the overall best model is shown in bold. Notably, the xLSTMs with new memory capabilities achieve the lowest perplexity scores, highlighting their effectiveness in this task. These top-performing models are then used in further experiments.

This table compares the performance of various language models, including xLSTM variants, on a next-token prediction task using the SlimPajama dataset. It shows the validation perplexity achieved by each model, highlighting the best-performing models within different model categories (linear Transformers, RNNs, Transformers, SSMs) and overall. The table also notes that the best-performing models from each category are used in subsequent, larger-scale experiments.

This table compares the performance of various language models on a next-token prediction task using the SlimPajama dataset. It shows the validation perplexity achieved by different model architectures (Transformers, RNNs, SSMs, and XLSTMs), highlighting the best-performing models within each class and overall. The table is specifically useful for understanding the relative performance of XLSTMs compared to state-of-the-art alternatives on a large-scale language modeling task. The table also indicates that XLSTMs with new memory mechanisms perform exceptionally well.

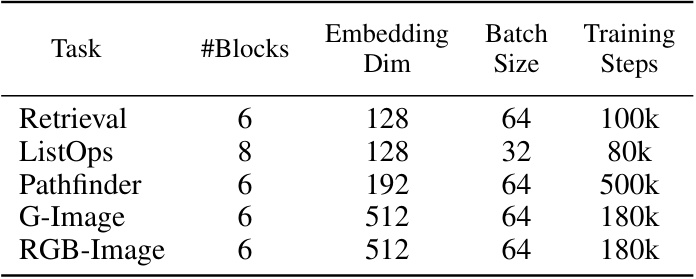

This table shows the hyperparameters used in the Long Range Arena experiments. It lists the number of blocks, embedding dimension, batch size, and training steps used for each of the five tasks: Retrieval, ListOps, Pathfinder, G-Image, and RGB-Image. The hyperparameters were chosen to optimize performance on the given tasks. The table helps to reproduce these experiments.

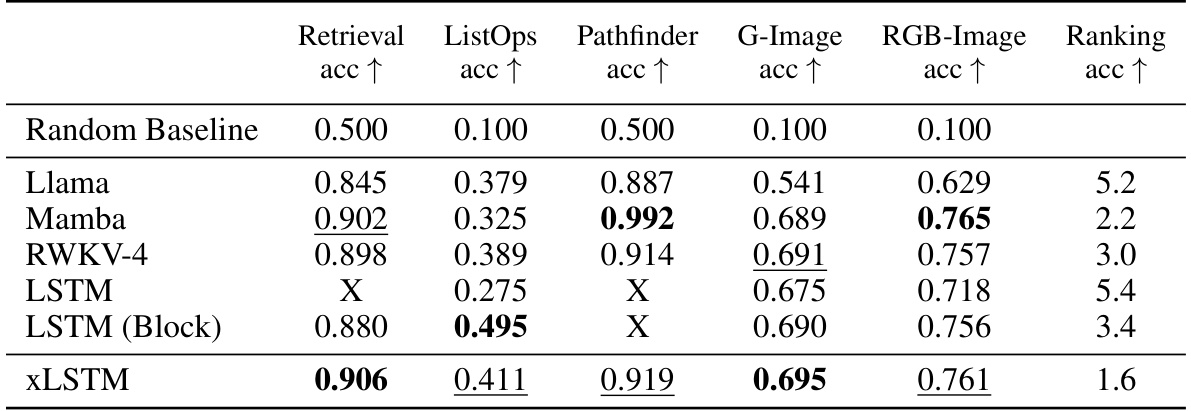

This table shows the results of the Long Range Arena benchmark. The accuracy of different models on five tasks (Retrieval, ListOps, Pathfinder, G-Image, and RGB-Image) is presented. The best performing model for each task is highlighted in bold and the second-best model is underlined. A ranking of all models is also provided, indicating the overall performance of each model across all tasks.

This table compares the performance of various language models on the next token prediction task using the SlimPajama dataset (15B tokens). Models are categorized into linear Transformers, RNNs, Transformers, and State Space Models (SSMs). The table shows the number of parameters for each model and its validation perplexity. The best performing models within each category are highlighted, with the overall best model shown in bold. The results indicate that XLSTM models with new memory mechanisms achieve the lowest perplexity, suggesting their superiority in next-token prediction.

This table compares the performance of various language models on the next token prediction task using the SlimPajama dataset (15B tokens). The models are categorized into linear Transformers, RNNs, Transformers, and State Space Models (SSMs). The table shows the number of parameters for each model and its validation perplexity. The best performing model in each category is underlined, and the overall best-performing model is shown in bold. Notably, the xLSTMs with new memory achieve the lowest perplexity.

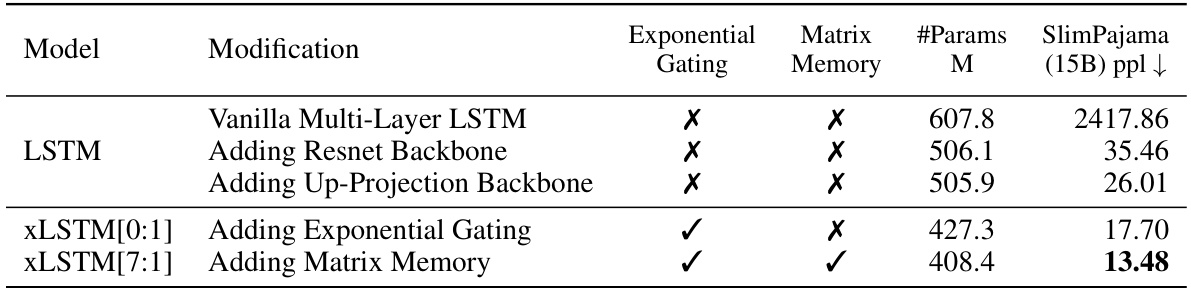

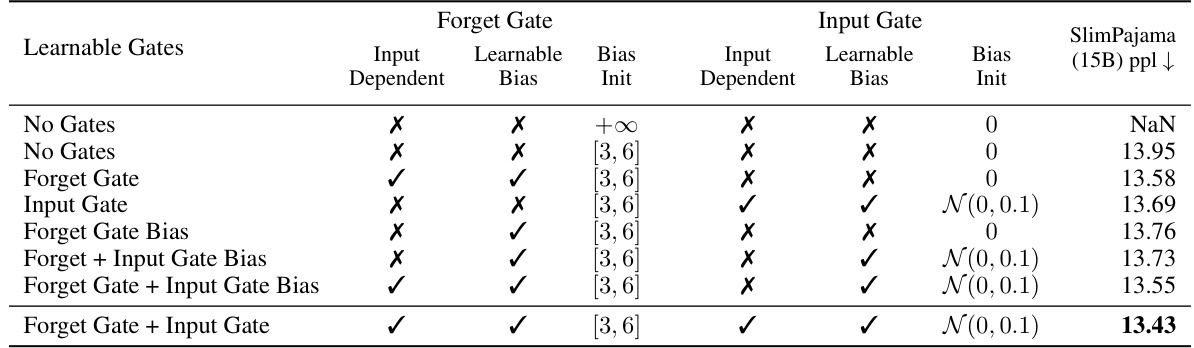

This table presents ablation studies on the xLSTM architecture. The top part shows the impact of adding different xLSTM components (exponential gating and matrix memory) on the model performance. The bottom part focuses on different gating techniques, comparing various combinations of learnable gates, input-dependent gates, and bias initializations. The results highlight the contribution of each component to the model’s overall performance, measured by the validation perplexity (PPL) on the SlimPajama dataset.

This table compares the performance of various language models on the next token prediction task, using 15B tokens from the SlimPajama dataset for training. The models are categorized into linear Transformers, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Transformers, and State Space Models (SSMs). The table highlights the best validation perplexity within each model class, with the overall best performance shown in bold. The best performing models from each class are then used in subsequent experiments.

This table presents the results of comparing various language models on the next token prediction task, after training them on 15 billion tokens from the SlimPajama dataset. The models are categorized into linear Transformers, RNNs, Transformers, and SSMs, with xLSTMs forming a separate class. The table highlights the best validation perplexity within each model category and overall. It also indicates that the xLSTMs with the new memory components achieved the best performance.

This table compares the performance of various language models on the next-token prediction task using the SlimPajama dataset (15B tokens). Models are categorized into linear Transformers, RNNs, Transformers, and State Space Models (SSMs). The table shows the number of parameters for each model and their validation set perplexity. The best performing model in each category is highlighted, along with the overall best-performing model. This table informs the selection of models for further large-language model training in Section 4.3.

This table compares the performance of various language models on a next-token prediction task, using 15B tokens from the SlimPajama dataset for training. The models are categorized into linear Transformers, RNNs, Transformers, and State Space Models (SSMs), along with the novel xLSTMs. The table highlights the best-performing model within each category and overall, indicating the superior performance of xLSTMs with the new memory structures.

This table compares the performance of various language models on the next token prediction task, using the SlimPajama dataset with 15B tokens. The models are categorized into linear Transformers, RNNs, Transformers, and SSMs, with xLSTMs forming a separate category. The table shows the number of parameters for each model and its validation perplexity. The best performing model within each category is underlined, and the overall best model is shown in bold. The table highlights that xLSTMs with novel memory mechanisms achieve the best performance, setting the stage for the scaling experiments in section 4.3.

This table compares the performance of various language models (including xLSTM variants) on the next-token prediction task. Models are grouped into categories (linear Transformers, RNNs, Transformers, SSMs) based on their architecture and the best performing model from each category is used in later experiments. The table highlights the best overall performance and indicates the best-performing models in each category, showing that xLSTMs with new memory structures outperform others.

This table compares the performance of various language models on the next token prediction task using the SlimPajama dataset. The models are categorized into linear Transformers, RNNs, Transformers, and SSMs, with XLSTMs included as a separate category. The table highlights the best validation perplexity results within each model category, with the overall best performance shown in bold. The best performing models from each category are selected for further large-scale language model training in section 4.3 of the paper. The results showcase the superior performance of XLSTMs, particularly those with the new memory mechanisms.

This table compares the performance of various language models on the next token prediction task after training on 15 billion tokens from the SlimPajama dataset. Models are grouped into categories: linear Transformers, RNNs, Transformers, and State Space Models (SSMs). The table shows the number of parameters for each model and its validation set perplexity. The best performing models in each category are highlighted, and the overall best-performing model is indicated in bold. The results show xLSTMs with new memory structures achieving the lowest perplexity.

This table compares the performance of various language models on a next-token prediction task using the SlimPajama dataset (15B tokens). Models are categorized into linear Transformers, RNNs, Transformers, and SSMs, with XLSTMs forming a separate category. The table shows the number of parameters for each model, along with its validation perplexity (lower is better). The best performing model within each category is underlined, and the best overall model is bolded. The results highlight that the XLSTMs with novel memory architectures (xLSTM[1:0] and xLSTM[7:1]) achieve the lowest perplexity, indicating superior performance in this benchmark.

The table compares various language models trained on 15B tokens from the SlimPajama dataset, evaluating their performance based on next-token prediction perplexity. It highlights the best-performing models within different model categories (linear Transformers, RNNs, Transformers, SSMs, and xLSTMs). It also notes that the best-performing models are subsequently used for large language model training in a later section of the paper.

This table compares the performance of various language models (including xLSTM variants, Transformers, RNNs, and SSMs) on a next-token prediction task using the SlimPajama dataset with 15B tokens. The models are grouped into classes, and the best-performing model within each class is highlighted. The table shows the number of parameters for each model and its validation perplexity. The xLSTMs with the novel matrix memory architecture achieve the lowest perplexity, demonstrating their superior performance on this specific task.

This table compares the performance of various language models on the next-token prediction task using the SlimPajama dataset. Models are categorized into linear Transformers, RNNs, Transformers, and SSMs, with XLSTMs forming a separate category. The table shows the number of parameters for each model and its validation perplexity. The best-performing model in each category is underlined, with the overall best model shown in bold. The table highlights that the XLSTMs, particularly those incorporating new memory mechanisms, achieve the lowest perplexity.

This table compares the performance of various language models on a next-token prediction task using the SlimPajama dataset (15B tokens). Models are grouped by architecture type (linear Transformer, RNN, Transformer, SSM). The table shows the number of parameters for each model and its validation set perplexity. The best-performing model in each class is highlighted, with the overall best model shown in bold. The best-performing xLSTM models, which incorporate novel memory mechanisms, are emphasized.

This table presents the results of comparing various language models on next token prediction task using 15B tokens from SlimPajama dataset. It compares different model classes such as Transformers, RNNs, and SSMs, along with the proposed xLSTMs. The table highlights the best performing model within each class and overall by underlining and bolding the best validation perplexities. The best performing xLSTMs are those with new memory.

Full paper#