↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many researchers believe that large language models implicitly learn ‘world models’ – internal representations of how the world works. However, evaluating the accuracy of these models is a significant challenge. Existing methods often focus on next-token prediction accuracy which isn’t sufficient to capture the full complexity of a world model. The authors highlight that these models can make accurate next-token predictions while still possessing incoherent internal world models.

To address this, the paper proposes new evaluation metrics for world model recovery, inspired by classic language theory concepts. These metrics measure the model’s ability to compress and distinguish between sequences leading to the same or different states in the true underlying world model, respectively. Using these metrics in various domains like game playing, logic, and navigation, the researchers demonstrate that current generative models’ internal world models are less coherent than commonly believed.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it introduces novel evaluation metrics to assess the accuracy of implicit world models within generative models. This directly addresses the challenge of evaluating a model’s understanding of the underlying reality, which is vital for developing reliable AI systems. The work also opens avenues for further research in more complex, non-deterministic systems. The benchmark dataset is also a valuable contribution for future work in the area.

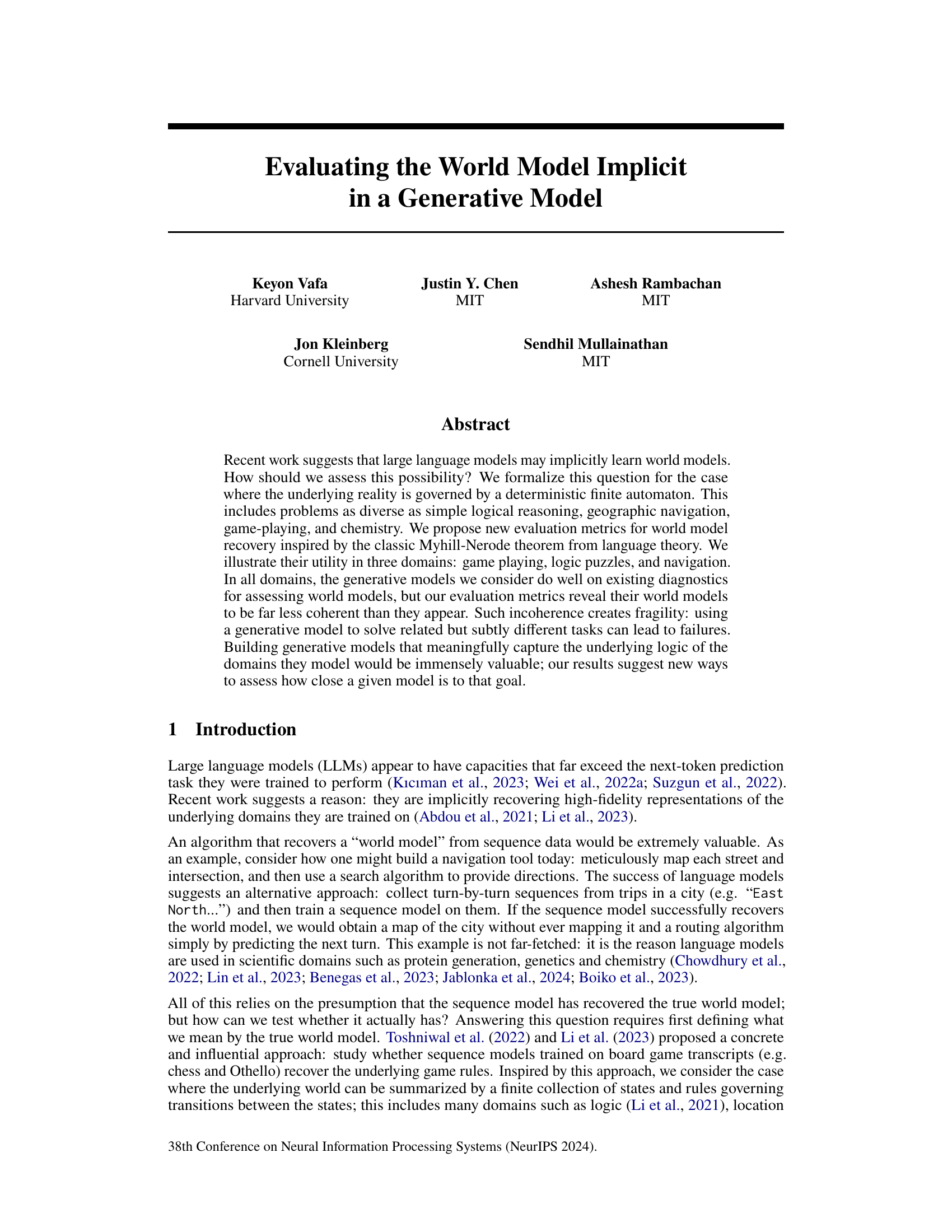

Visual Insights#

The figure illustrates the concepts of Myhill-Nerode boundary and interior. The left panel shows a conceptual diagram of a Myhill-Nerode boundary where the states are represented by circles that are either red, blue, or a combination of both. The green curve represents the boundary that separates the states. The right panel shows two examples of cumulative Connect-4 boards (a game where players drop disks into a vertical grid and attempt to get 4 in a row). Despite appearing different, these two example boards have the same set of valid next moves; they are indistinguishable in terms of next moves until a longer sequence of moves is considered, reaching the Myhill-Nerode boundary. This illustrates that evaluating world models only by checking the immediate next move is insufficient and demonstrates the necessity for looking at the longer sequences on the Myhill-Nerode boundary to properly assess model accuracy.

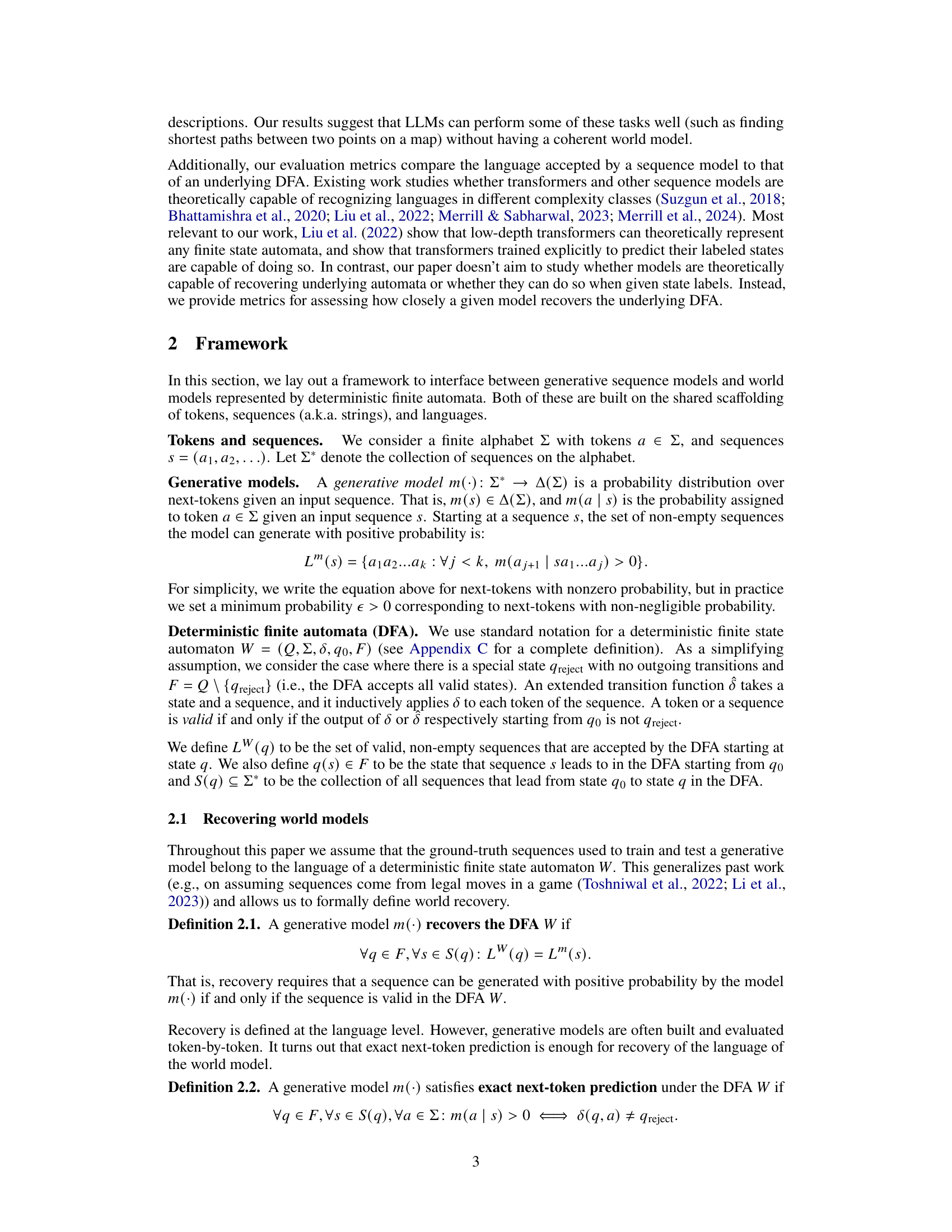

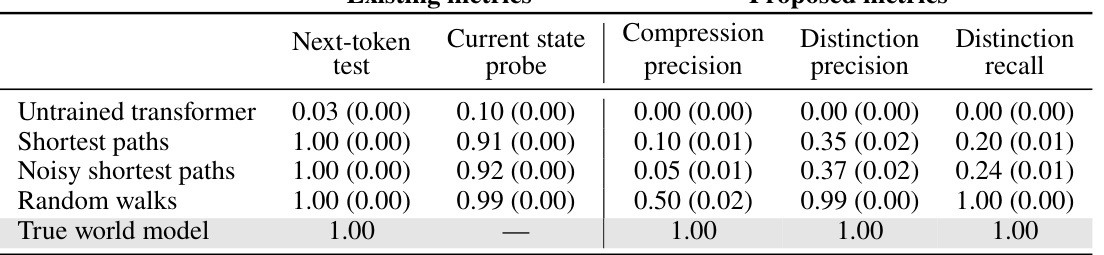

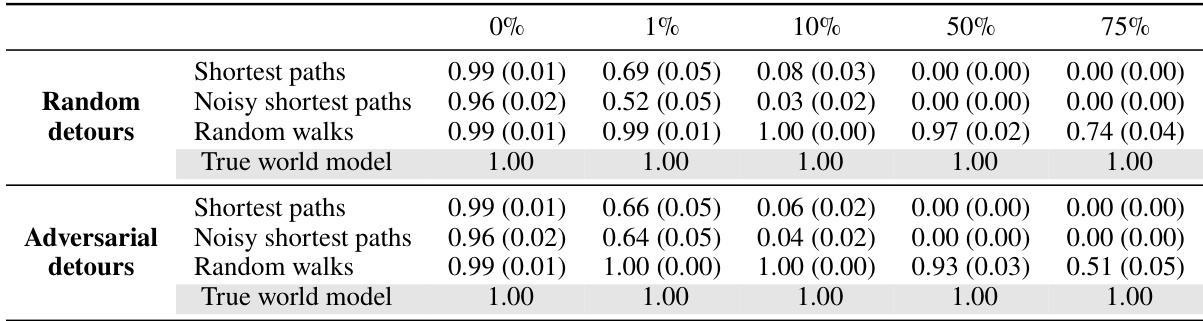

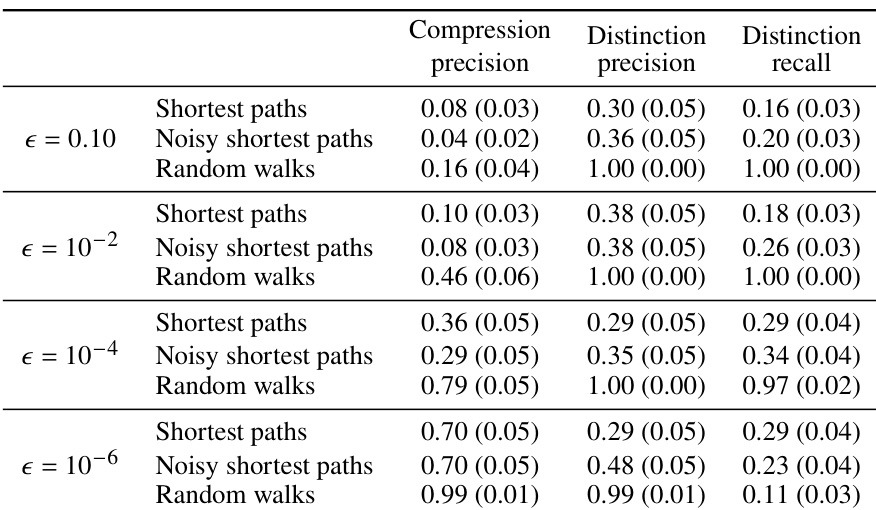

This table compares the performance of different language models on various metrics for evaluating world models. The existing metrics (next-token test and current state probe) assess the models’ ability to predict the next token or the current state, respectively. The proposed metrics (compression and distinction metrics) evaluate the coherence and consistency of the models’ implicit world models based on the Myhill-Nerode theorem. The results show that while some models perform well on the existing metrics, their performance can be significantly worse on the proposed metrics, indicating that those existing metrics are insufficient for fully evaluating the quality of the models’ world models.

In-depth insights#

Implicit World Models#

The concept of “Implicit World Models” in large language models (LLMs) is a fascinating area of research. LLMs, trained on vast textual data, appear to develop an internal representation of the world, enabling them to perform tasks beyond simple next-word prediction. This implicit knowledge, not explicitly programmed, allows for reasoning, planning, and even commonsense understanding. The paper investigates how to evaluate the quality and coherence of these implicit models. Current evaluation methods often focus on superficial performance metrics. However, the paper advocates for deeper evaluations that assess the internal consistency and structural validity of the world model, highlighting the danger of relying solely on task-specific accuracy. The authors propose novel evaluation metrics inspired by the Myhill-Nerode theorem, providing a more rigorous assessment of an LLM’s understanding of underlying principles rather than just surface-level capabilities. This approach allows for a more nuanced view, revealing that high task performance can mask significant inconsistencies within the model’s internal representation of the world. It shows the importance of focusing on the integrity of the world model itself, rather than just its observable outputs. Ultimately, understanding and improving these implicit models is crucial for building more robust, reliable, and truly intelligent LLMs.

Myhill-Nerode Metrics#

Myhill-Nerode metrics offer a novel approach to evaluating the implicit world models learned by generative models. They leverage the Myhill-Nerode theorem from automata theory, which states that distinct states in a deterministic finite automaton (DFA) can be distinguished by unique input sequences. The metrics assess a generative model’s ability to capture this state distinguishability. Compression metrics evaluate whether the model collapses distinct states by generating similar outputs, while distinction metrics check if it effectively differentiates states using unique continuations. This framework goes beyond simpler next-token prediction methods, which may fail to detect subtle inconsistencies. The Myhill-Nerode boundary, focusing on minimal distinguishing sequences, is key. This approach provides a more robust and theoretically grounded evaluation of a generative model’s world model accuracy, revealing the true coherence and ability of the model to generate relevant and consistent outputs for downstream tasks. The use of this approach highlights the significance of evaluating generative model’s internal representations beyond simple surface-level performance metrics.

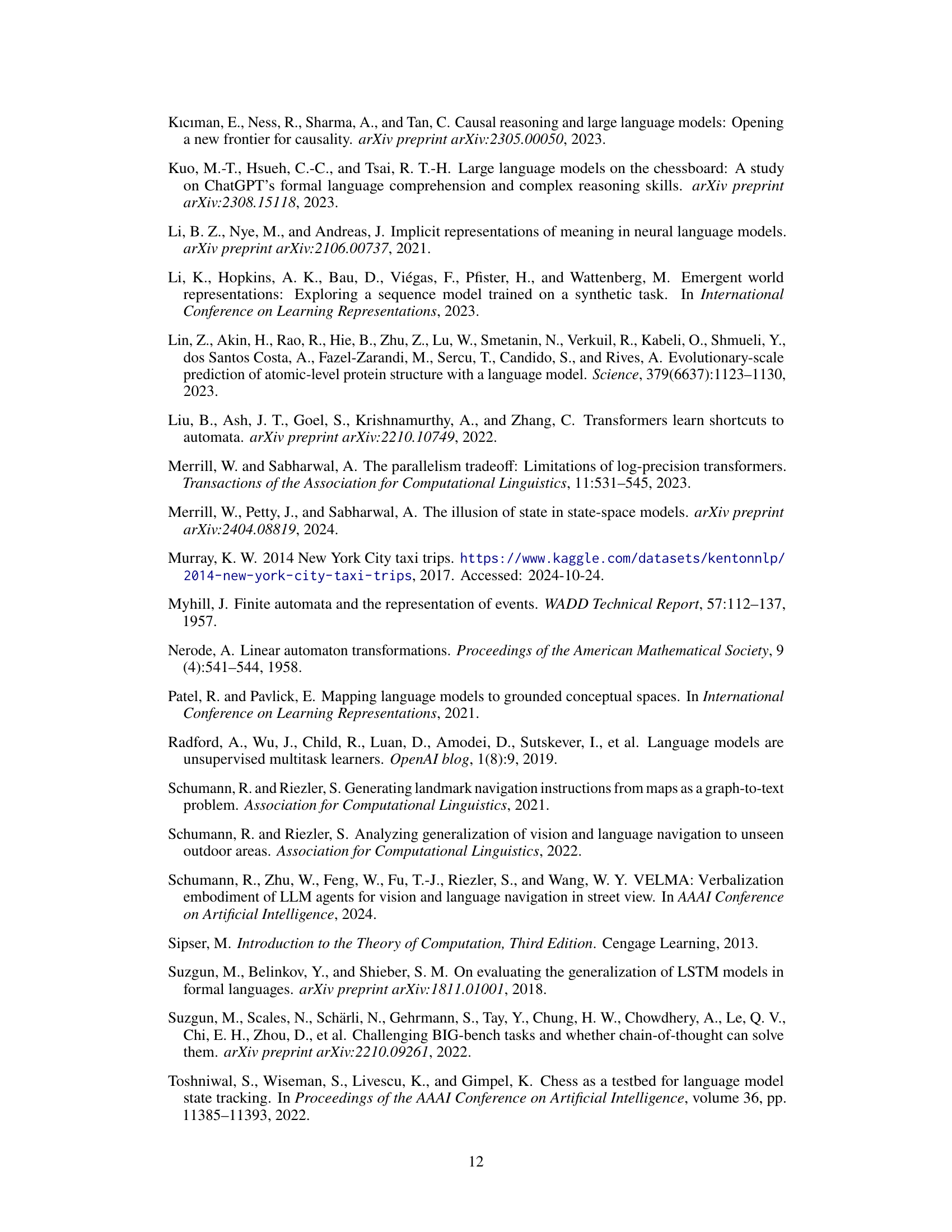

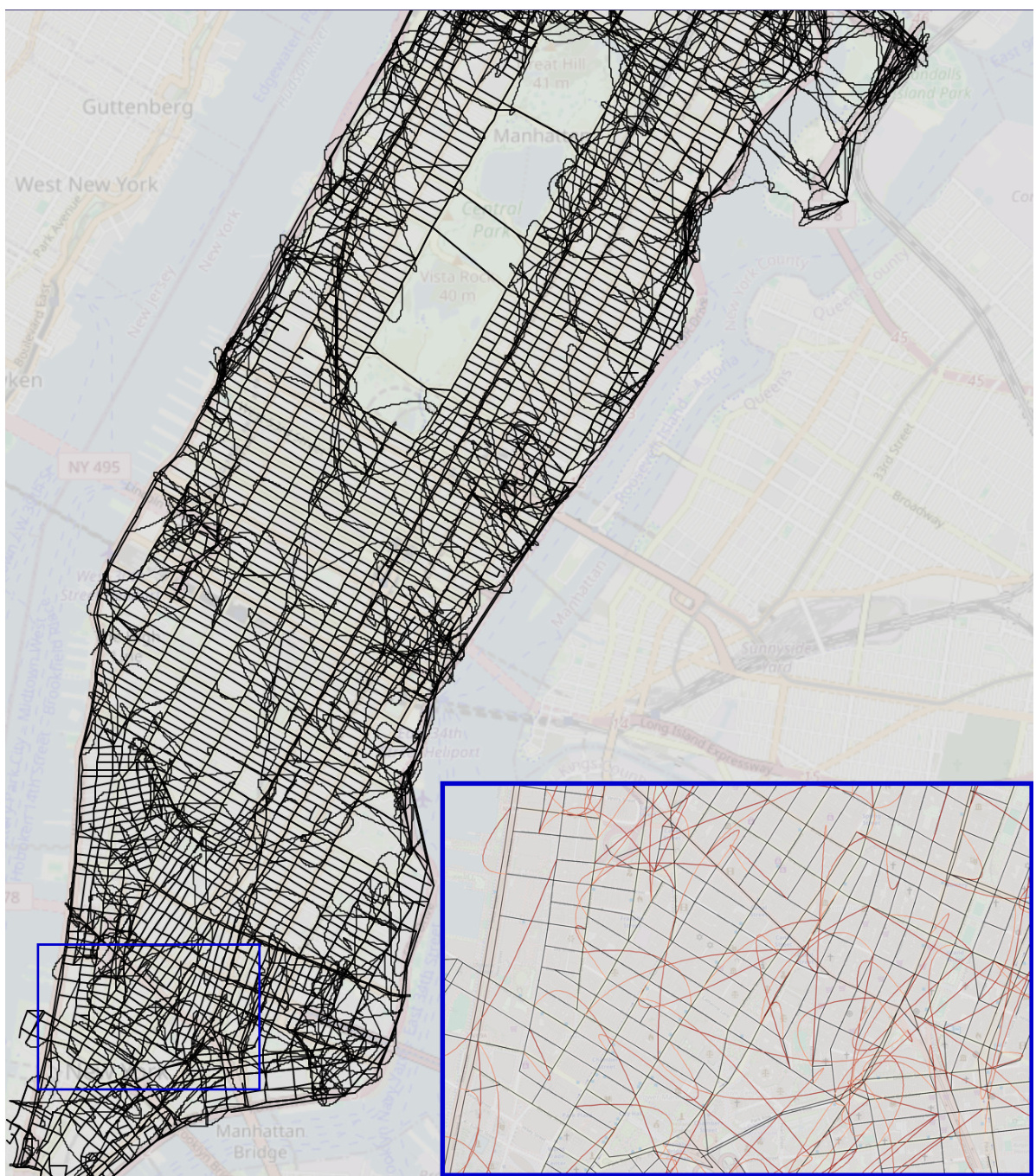

NYC Taxi Map Test#

The NYC Taxi Map Test section, though stylized, offers a potent critique of existing LLM evaluation metrics. It cleverly uses real-world taxi data to train transformer models and assess their capacity to implicitly learn a city map. Existing metrics like next-token prediction, while seemingly successful, fail to reveal the true incoherence of the learned map. The researchers introduce novel evaluation metrics grounded in the Myhill-Nerode theorem, revealing that while models accurately predict next turns in most cases, their underlying representation of the city’s structure is fragmented and nonsensical. Graph reconstruction of the implied map strikingly visualizes this incoherence, demonstrating a significant gap between high next-token prediction accuracy and an actual understanding of the underlying navigational structure. This highlights the fragility of LLMs trained on sequence data alone, with their performance breaking down under downstream tasks, such as route planning with unexpected detours. The study thus powerfully advocates for more rigorous evaluation methods that probe the deep structural understanding, not just superficial performance, of LLMs.

Fragile World Models#

The concept of “Fragile World Models” highlights the inconsistency between the impressive performance of large language models (LLMs) on certain tasks and their limited understanding of the underlying rules governing those tasks. The authors demonstrate that while LLMs might excel at surface-level tasks, their internal representations of the world are often incoherent and fragile. This fragility manifests as a failure to generalize to subtly different tasks, despite seemingly accurate performance on similar problems. This suggests that existing evaluation metrics, focused on next-token prediction, are insufficient for assessing genuine world model acquisition. The paper proposes novel evaluation metrics that reveal the underlying fragility by measuring the model’s ability to compress similar sequences leading to the same state, and to distinguish sequences leading to different states. This approach unveils significant discrepancies between the surface-level capabilities and the deep structural understanding within LLMs.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the framework beyond deterministic finite automata (DFAs) to encompass more complex models of the world, such as probabilistic or hierarchical models, is crucial to capture the nuances of real-world systems. This would involve developing new evaluation metrics that can robustly assess the coherence and accuracy of these more sophisticated world models. Furthermore, investigating the relationship between the architecture of generative models and their ability to recover world models represents a significant challenge. Examining different architectures, such as those with specialized memory mechanisms or inductive biases, could lead to the development of generative models that explicitly represent and reason about the underlying structure of the world. Finally, applying these evaluation methods to broader tasks and domains, moving beyond game playing and navigation, to fields like robotics or scientific discovery, is essential to demonstrate the practical utility and generalizability of these techniques. A key focus should be on understanding how the incoherence of implicit world models impacts real-world performance of LLMs and developing strategies to mitigate these issues.

More visual insights#

More on figures

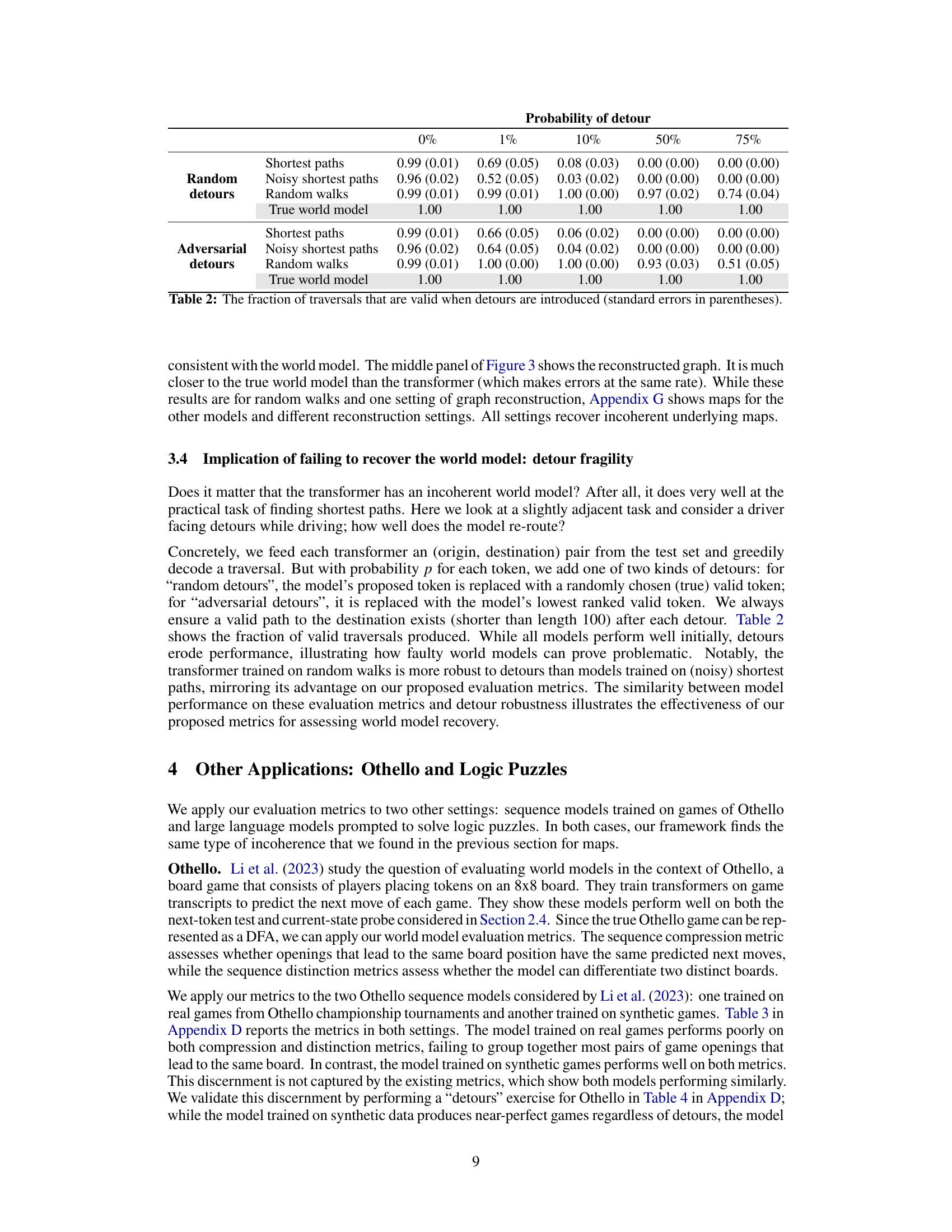

This figure visually explains the two proposed evaluation metrics: Compression Metric and Distinction Metric. The Compression Metric assesses whether a model correctly identifies that sequences leading to the same state in the underlying Deterministic Finite Automaton (DFA) should accept the same suffixes. The Distinction Metric evaluates a model’s ability to find the correct distinguishing suffixes for sequences that lead to different states in the DFA. Both metrics focus on the Myhill-Nerode boundary, illustrating the errors (compression and distinction) at the boundary to provide a clear understanding of the model’s accuracy in capturing the underlying state structure.

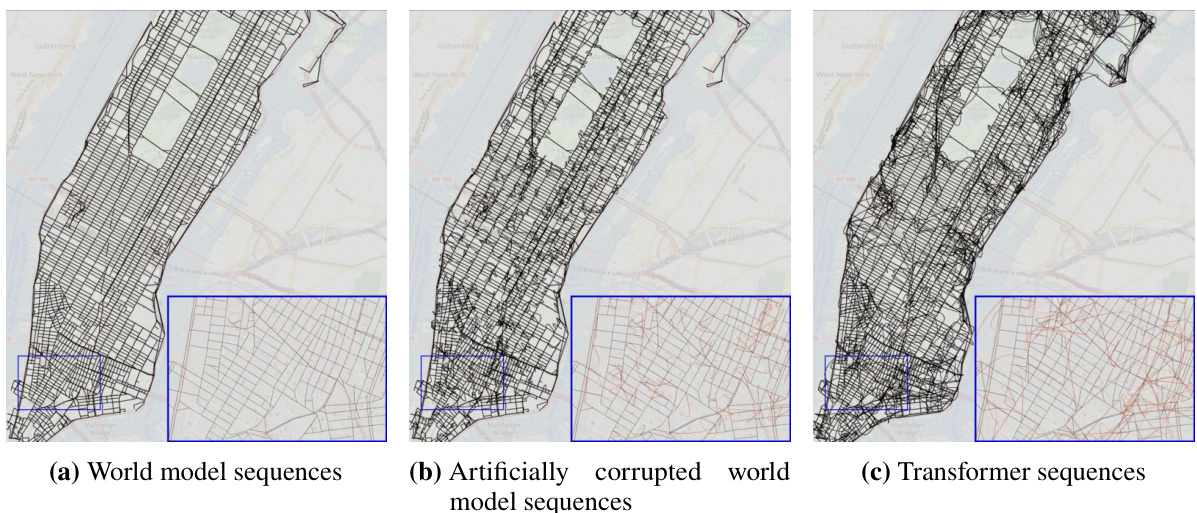

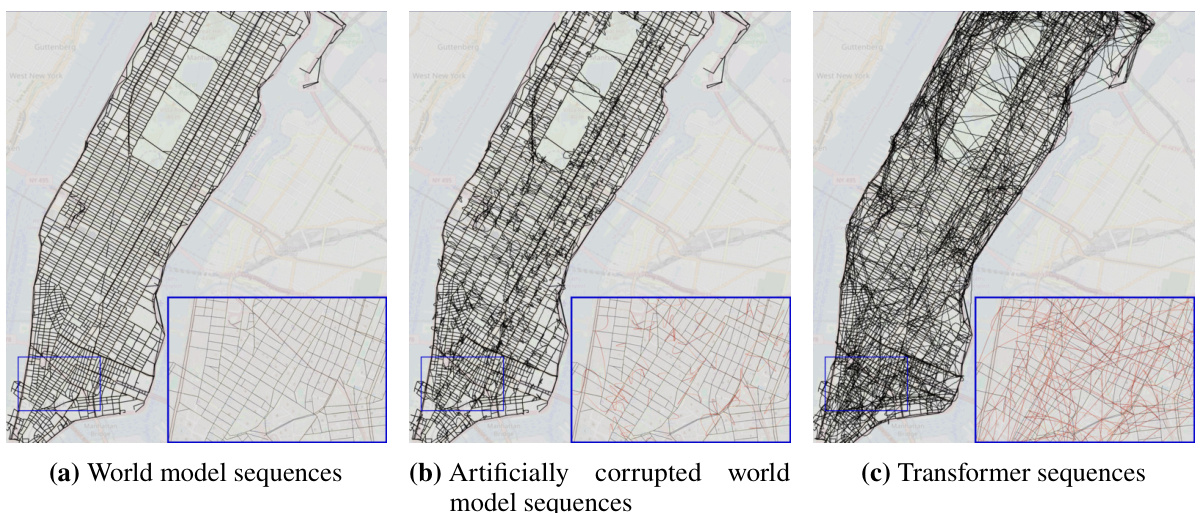

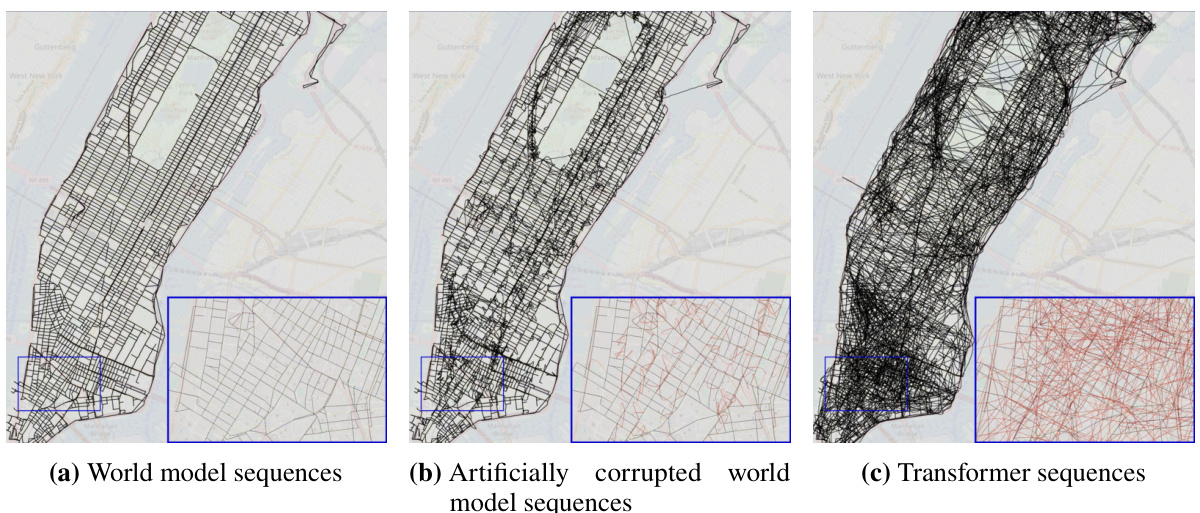

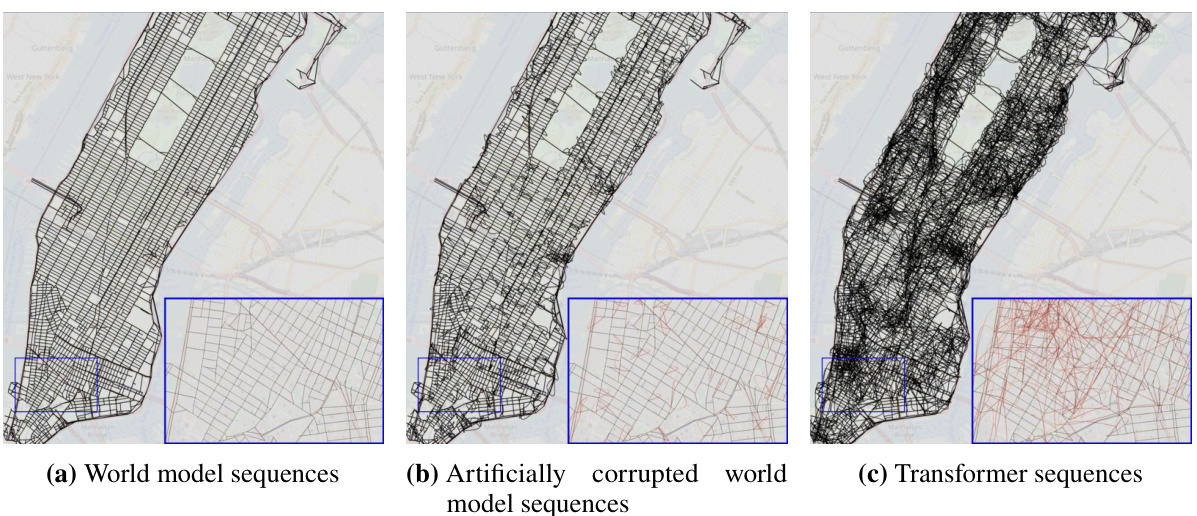

This figure shows a comparison of three different reconstructed maps of Manhattan. The first map is the ground truth, representing the actual street layout. The second map is the ground truth with added noise, simulating imperfections in real-world data. The third map is a reconstruction generated by a transformer model trained on random walk data. The zoomed-in sections highlight the differences, particularly illustrating how the transformer’s reconstruction includes many spurious edges that do not exist in the actual street network. Interactive versions of the reconstructed maps are available online.

This figure illustrates the concept of Myhill-Nerode interior and boundary. The left panel shows a visual representation of these concepts, where the interior represents sequences that lead to the same state regardless of the starting state, and the boundary represents the minimal sequences needed to distinguish between the states. The right panel shows an example with cumulative Connect-4 game states where both states have the same set of valid next moves, demonstrating how the length of sequences can affect distinguishing between states.

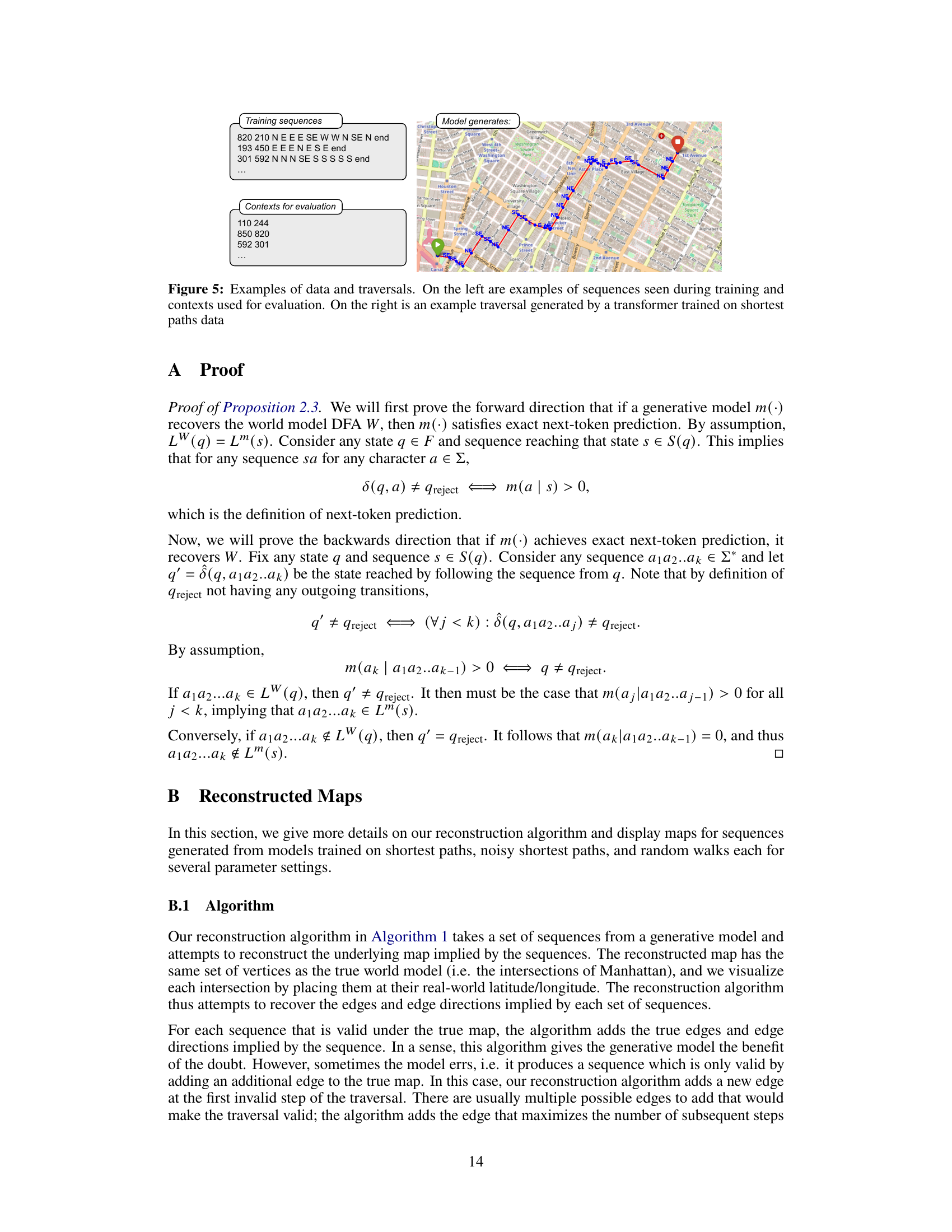

This figure shows examples of the training data used in the paper and how the model generates a traversal given an (origin, destination) pair. The left side displays several examples of sequences representing taxi trips in New York City, showing the origin node, destination node and the sequence of turns taken between them. The right side provides a visual representation of a model’s output on a sample context. The map illustrates the path generated by a transformer model trained to predict the shortest path between two locations. The generated path closely follows the actual street layout of the area and is marked with colored arrows indicating turns at each intersection.

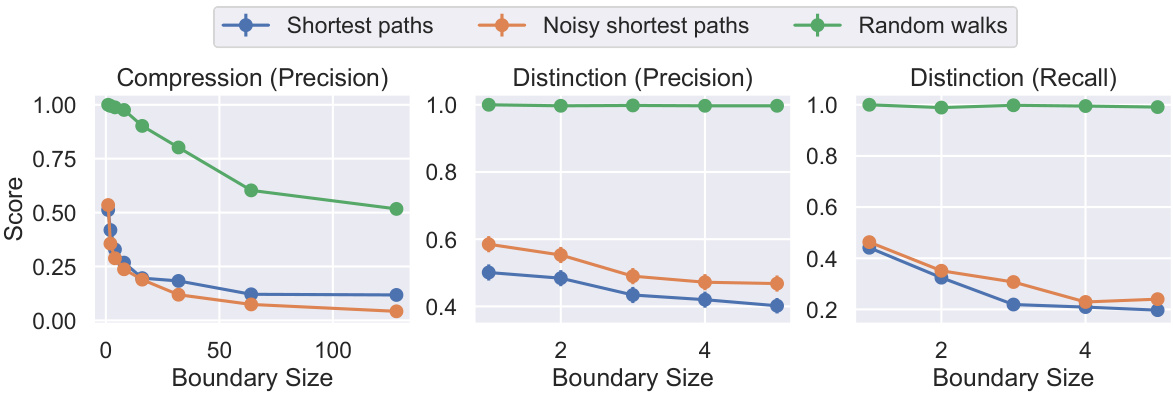

This figure shows how the three metrics (Compression Precision, Distinction Precision, and Distinction Recall) change as the maximum suffix length used to approximate the Myhill-Nerode boundary increases. The x-axis represents the boundary size (maximum suffix length), and the y-axis represents the metric score. Three lines are shown for each metric, corresponding to the three different data generation methods used to train the models (shortest paths, noisy shortest paths, and random walks). The figure demonstrates the impact of the boundary size on the performance of each metric, and how the performance varies across different data generation methods.

This figure shows the relationship between compression precision (a metric evaluating how well the generative model recognizes that two sequences resulting in the same state accept the same suffixes) and the number of two-way streets at the current intersection. The data is specifically from the model trained on shortest path traversals. The graph reveals a negative correlation: as the number of two-way intersections increases, the model’s ability to compress sequences diminishes. This indicates that the model struggles to represent the complexities inherent in scenarios with multiple possible turning directions from a given intersection.

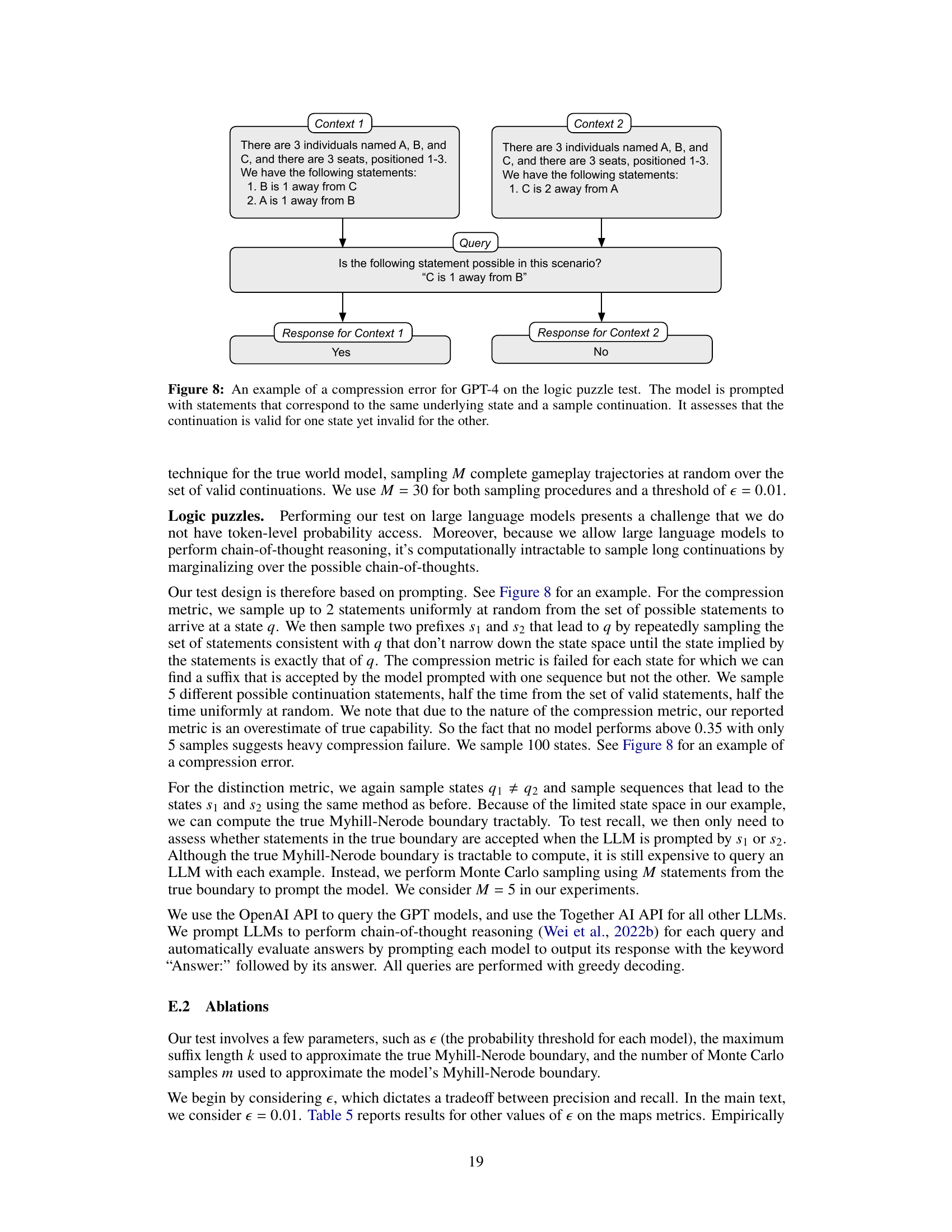

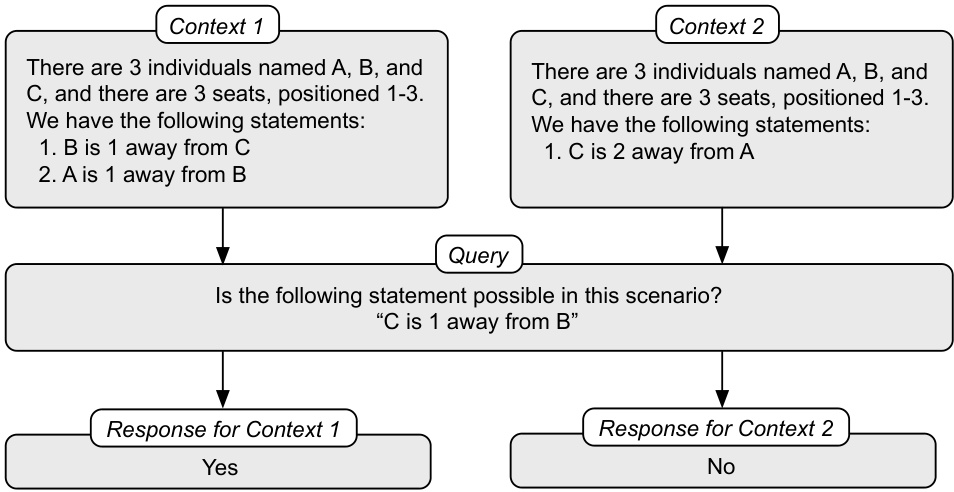

This figure demonstrates a compression error using GPT-4 on a logic puzzle. Two different sets of statements (Context 1 and Context 2) result in the same underlying state (the same seating arrangement possibilities). A query is then posed asking if a specific statement is possible in each scenario. The model correctly answers ‘yes’ for Context 1 but ’no’ for Context 2, showing an inability to consistently recognize that equivalent states should have the same valid continuations. This illustrates a failure of the compression metric.

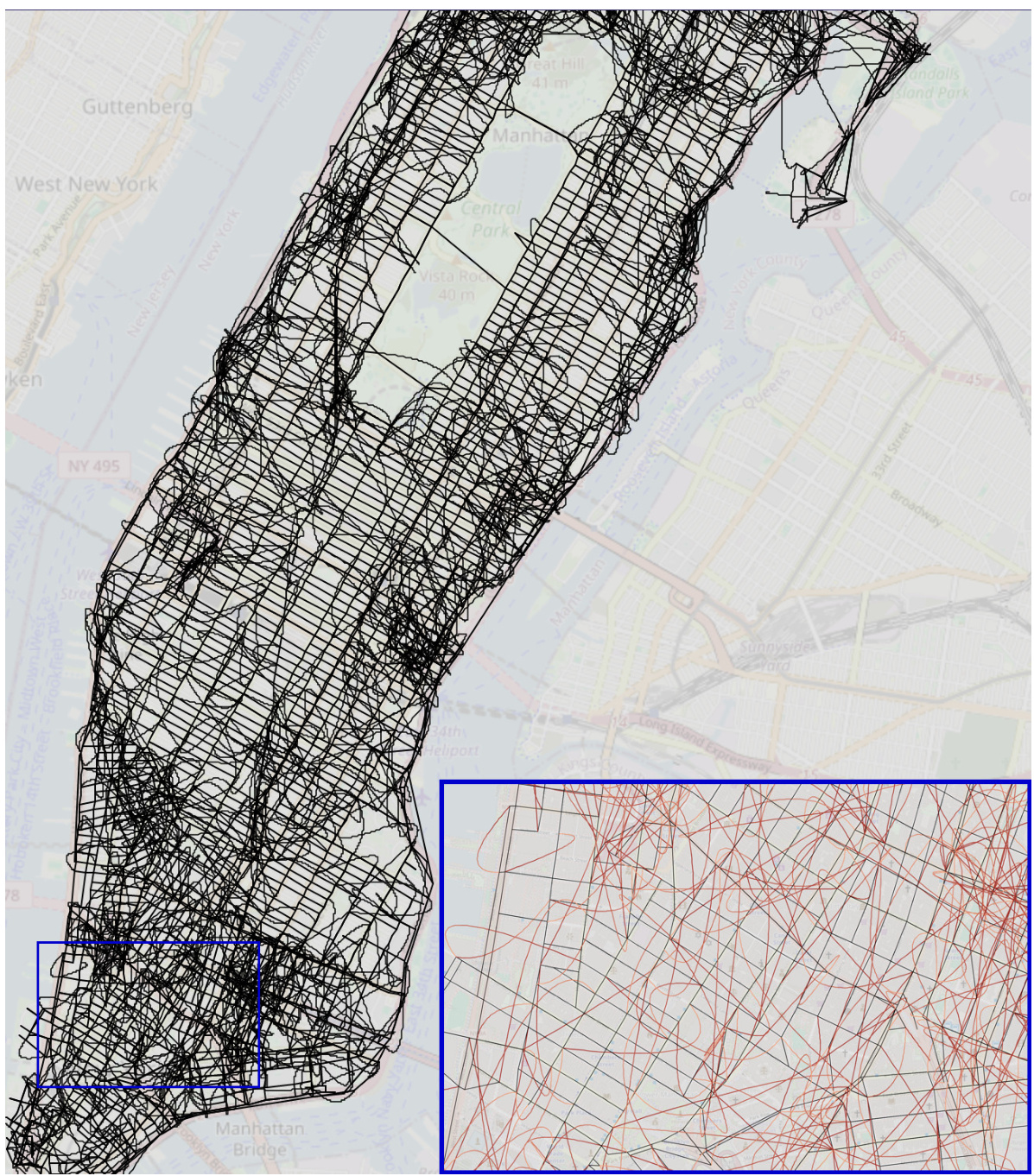

This figure compares the reconstructed maps of Manhattan generated from three different sources: the true street map, the true street map with added noise, and the map implicitly represented by a transformer model trained on random walks of taxi rides. The true map serves as a baseline. The noisy map simulates the effect of real-world uncertainties. The transformer’s output showcases how the model attempts to reconstruct the map based solely on sequential turn-by-turn instructions. The zoomed-in sections highlight the differences between the true map and the model’s output, with incorrect or non-existent streets represented in red, demonstrating the incoherence of the model’s implicit world representation.

This figure compares three reconstructed maps of Manhattan. The first is the actual map, the second is the actual map with some added noise, and the third is a map reconstructed from the sequences generated by a transformer model trained on random walks. The zoomed-in sections highlight the differences; the true map edges are black, while the falsely added edges are red, illustrating the inaccuracies of the transformer’s implicit world model.

This figure visualizes the reconstructed maps of Manhattan generated by three different models: the true world model, the true world model with added noise, and a transformer model trained on random walks. The maps illustrate the differences in the accuracy and coherence of the world models learned by each model. The true world model is shown to be accurate and consistent with the actual street layout, while the noisy world model and transformer model show inaccuracies and inconsistencies in the representation of the city’s streets.

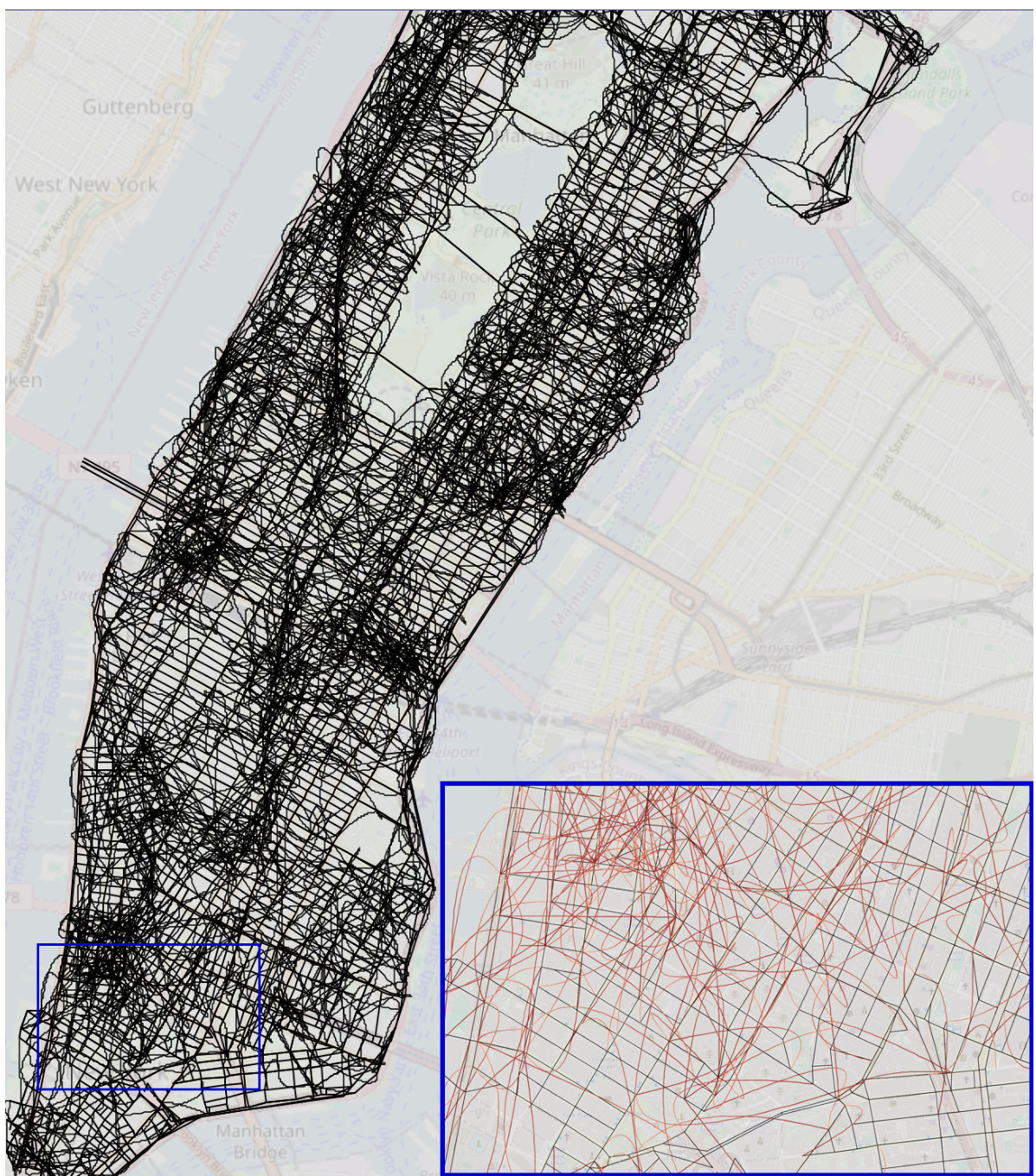

This figure compares three reconstructed maps of Manhattan. The first map is the ground truth map, the second is the ground truth map with added noise, and the third is a map reconstructed from a transformer model trained on random walk data. The zoomed-in sections highlight differences between the maps, showing the discrepancies between the true map and the model-generated map. Black edges are consistent with the ground truth, while red edges are inconsistencies generated by the model.

This figure shows three reconstructed maps of Manhattan. The leftmost map is the true world model. The middle map is the true world model with noise added. The rightmost map is the model reconstructed by a transformer trained on sequences of random walks. The zoomed-in insets show details of the maps. Black edges are from the true map; red edges are false edges added by the reconstruction algorithm. The authors provide interactive links to the full reconstructed maps from different transformer models.

This figure compares the reconstructed maps of Manhattan generated by three different models: the true world map, a noisy version of the true world map, and the map generated by a transformer model trained on random walks. The zoomed-in sections highlight the differences, with black edges representing the true map and red edges indicating errors introduced by the reconstruction algorithm. Interactive versions of the transformer-generated maps are available online.

This figure shows three reconstructed maps of Manhattan. The leftmost panel displays the true street map. The middle panel shows the true map with added noise to simulate real-world imperfections. The rightmost panel shows a map reconstructed from the predictions of a transformer model trained on random walk data. The zoomed-in sections highlight the differences between the true maps and the model’s reconstruction, with black lines representing true streets and red lines indicating inaccuracies or false streets introduced by the model.

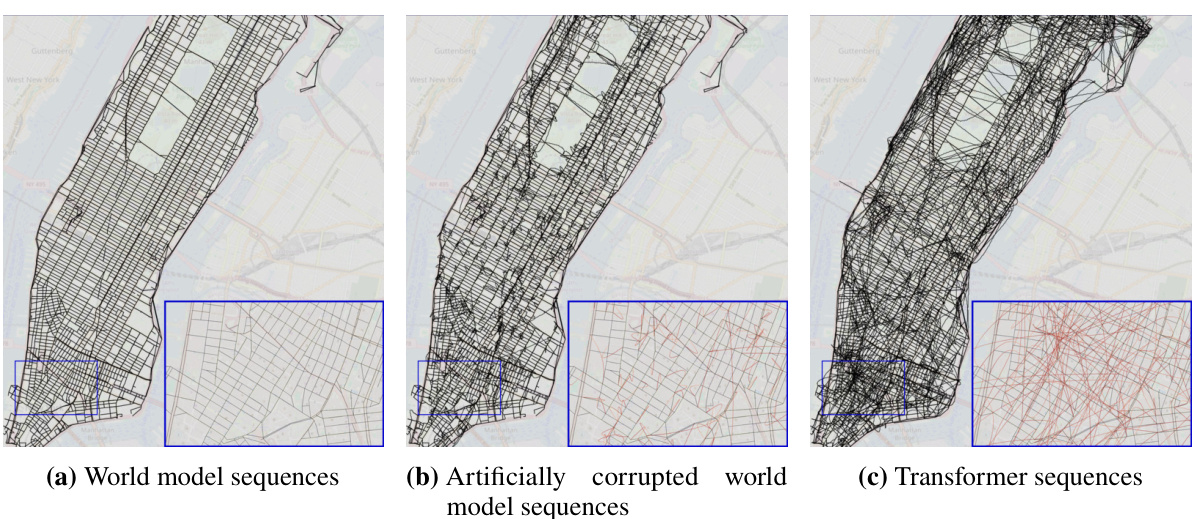

This figure shows three reconstructed maps of Manhattan. The leftmost map represents the true underlying street map of Manhattan as the ground truth. The middle map shows the true street map but with added noise, and the rightmost map shows the street map reconstructed from the sequences produced by a transformer model. The color-coding helps visualize the differences between the maps: black edges represent actual streets, while red edges indicate streets created by the reconstruction algorithm.

This figure shows three reconstructed maps of Manhattan. The leftmost map is the ground truth map, showing the actual street layout. The middle map shows the same layout but with some artificial noise added to simulate errors. The rightmost map is a reconstruction generated by a transformer model trained on random walk sequences through the city. The zoomed sections show detailed comparisons, highlighting the differences between the true map and the transformer’s interpretation. Black lines represent true street segments, while red lines represent street segments added by the reconstruction algorithm that were not in the original map. The interactive maps provide a more detailed visualization of the transformer’s representation of the city street network.

This figure compares the reconstructed maps of Manhattan generated by three different models: the true world model, a noisy version of the true world model, and a transformer model trained on random walks. The reconstruction algorithm attempts to build a map from the sequences of directions generated by each model. The true map is shown for comparison. Differences between the reconstructed maps and the true map highlight inconsistencies in the world models learned by the different models, particularly the transformer model which shows many inconsistencies and physically impossible street orientations and flyovers.

This figure compares three reconstructed maps of Manhattan. The first map represents the actual street layout. The second map adds noise to the true world model to simulate the effect of errors. The third map shows the map reconstructed from the sequences generated by a transformer model trained on random walks. The zoomed-in sections highlight the differences between the true and reconstructed maps, with false edges appearing in red. Interactive versions of the reconstructed maps are available online for the shortest path, noisy shortest path, and random walk models.

This figure compares three reconstructed maps of Manhattan. The first is the actual map of Manhattan. The second is the actual map of Manhattan but with added noise to simulate real-world imperfections. The third is a map reconstructed by a transformer model trained only on sequences of turns from random taxi rides. The differences between the maps highlight the limitations of using only next-token prediction accuracy to assess how accurately a generative model captures the underlying structure (world model) of a domain.

This figure compares the reconstructed maps of Manhattan generated from three different sources: the true world map, the true map with added noise, and a transformer model trained on random walks. The main point is to visualize how the transformer’s implicit understanding of the city’s street layout (its world model) differs from the actual map. The differences are highlighted in the zoomed-in sections, where incorrect connections generated by the transformer are shown in red, contrasting with the correct black lines of the true map. Interactive versions of the maps generated by the transformer models (trained on shortest paths, noisy shortest paths, and random walks) are available online via the links provided in the caption.

This figure shows three reconstructed maps of Manhattan. The leftmost panel shows the true street map. The middle panel depicts the true map but with artificially added noise. The rightmost panel shows a reconstructed map from a transformer model trained on random walks, illustrating the differences between the true map and the model’s implicit representation of the city’s street layout.

This figure compares the reconstructed maps of Manhattan generated from three different sources: the true world model, the true world model with added noise, and a transformer model trained on random walks. The images visually represent the street network. Black lines represent correctly identified streets, while red lines highlight incorrectly added streets by the model. The insets provide a zoomed-in view for a more detailed comparison. Interactive versions of the transformer-generated maps are available online.

This figure compares the reconstructed maps of Manhattan generated from three different models: the true world model, the true world model with added noise, and a transformer model trained using random walks. The reconstruction algorithm attempts to build a map from the sequence data, highlighting differences between the models’ ability to accurately represent the street layout. Black edges in the zoomed-in sections represent streets in the true map, while red edges represent inaccuracies introduced by the reconstruction process based on model-generated data. Interactive versions of the reconstructed maps produced by transformer models (trained on shortest paths, noisy shortest paths, and random walks data) are provided in the caption.

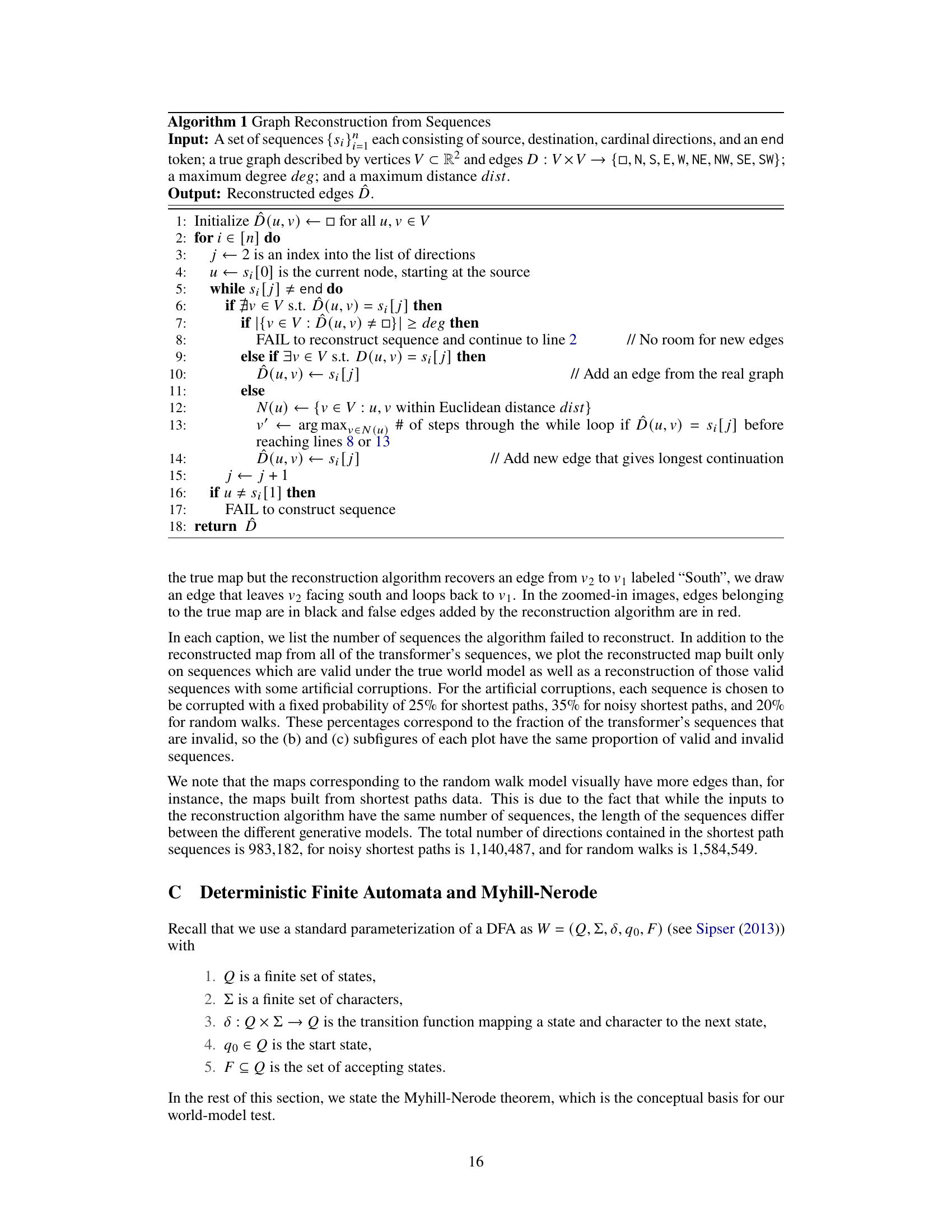

More on tables

This table compares the performance of different world models on sequence compression and distinction metrics. It contrasts the results from two existing evaluation metrics (next-token test and current state probe) with the proposed metrics. The table shows that models performing well on the existing metrics may still poorly perform on the new metrics, highlighting limitations of existing evaluation methods.

This table compares the performance of different models on novel sequence compression and distinction metrics against existing metrics (next-token test and current-state probe). The results show that models performing well on traditional metrics may perform poorly on the newly proposed metrics, highlighting the limitations of the existing evaluation methods in assessing the coherence of implicit world models.

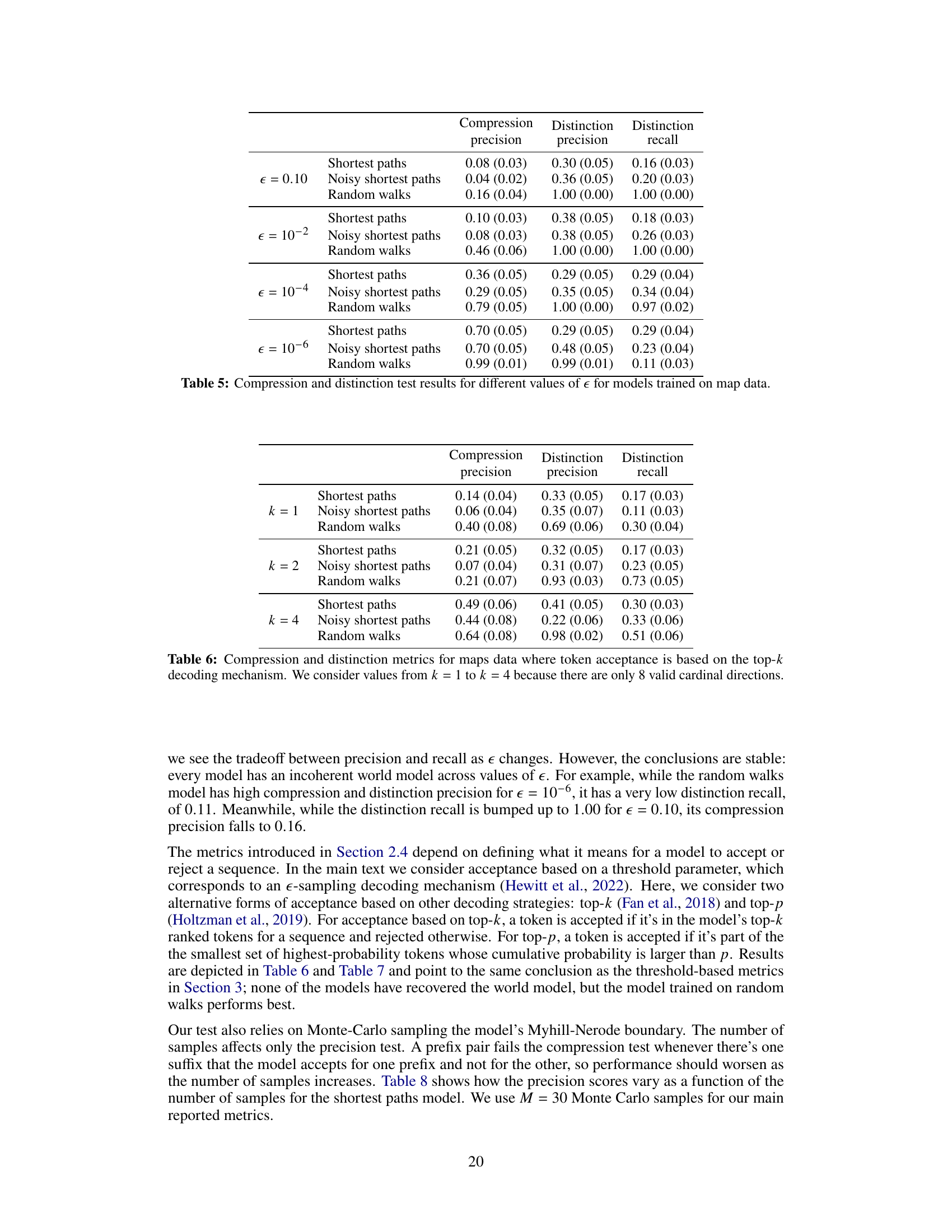

This table compares the performance of various models (untrained transformer, models trained on shortest paths, noisy shortest paths, and random walks) on different metrics for evaluating world models. It contrasts two types of metrics: existing metrics (next-token test and current-state probe) and the proposed metrics (compression and distinction metrics) from the paper. The results demonstrate that models performing well on existing metrics may still have incoherent world models, highlighting the limitations of existing approaches and the value of the new metrics. Standard errors are included in parentheses to indicate the uncertainty of the results.

This table presents the results of applying the proposed evaluation metrics (compression and distinction precision and recall) to Othello game sequence models. It compares the performance of an untrained transformer, models trained on real championship Othello games, models trained on synthetic Othello games, and a true world model representing perfect knowledge of the game’s rules. The goal is to assess how well each model captures the underlying structure of the game. Lower precision and recall scores indicate a less accurate world model.

This table compares the performance of different generative models (untrained transformer, models trained on shortest paths, noisy shortest paths, and random walks) on both existing metrics (next-token test, current-state probe) and the proposed metrics (compression precision, distinction precision, distinction recall). The existing metrics evaluate whether the model predicts valid next tokens and whether the model’s representation can recover the current state. The proposed metrics evaluate whether the model effectively compresses similar sequences and distinguishes dissimilar sequences. The table shows that while models may achieve high scores on existing metrics, they may perform poorly on the proposed metrics, indicating the insufficiency of existing evaluation methods.

This table compares the performance of different generative models on novel metrics for evaluating world models (compression and distinction) to existing metrics (next-token and current state). The results show that models performing well on traditional metrics can still fail on the proposed metrics, highlighting the limitations of existing evaluation methods.

This table compares the performance of different generative models on various metrics for assessing world model recovery. It contrasts the proposed metrics (compression precision, distinction precision, distinction recall) with existing metrics (next-token accuracy and current-state probe). The results reveal that models performing well on existing metrics might still have poor performance on the newly proposed metrics, highlighting the limitations of traditional evaluation approaches.

This table compares the performance of different models on various metrics for evaluating the quality of their implicit world models. It contrasts two types of metrics: existing metrics (next-token test and current-state probe) and the proposed metrics (sequence compression and distinction). The results highlight that models which perform well on existing metrics might perform poorly on the newly proposed metrics, indicating the limitations of existing methods for evaluating implicit world models.

This table compares the performance of different models on novel metrics for evaluating world models against existing metrics (next-token test and current-state probe). The novel metrics evaluate the coherence of the implicit world model learned by the generative models. The table shows that models performing well on traditional metrics can perform poorly on the proposed metrics, indicating that traditional metrics may not be sufficient for evaluating world model recovery.

Full paper#