↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Creating high-quality scientific figures is time-consuming. Current methods lack semantic information preservation, making figure editing and reuse difficult. Many researchers lack the programming skills to easily create these figures from scratch.

DeTikZify tackles this by using a multimodal language model that automatically generates TikZ code for scientific figures from sketches or existing figures. It leverages three new datasets and an MCTS algorithm to iteratively refine outputs. Evaluation shows DeTikZify outperforms existing LLMs, significantly improving the efficiency and accessibility of scientific figure creation.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in computer graphics and machine learning because it introduces a novel approach to automatically generate scientific figures using AI, addressing a significant bottleneck in research workflows. The project’s open-source nature further enhances its impact by fostering collaboration and accelerating progress in the field. It opens new avenues for research on multimodal models and code generation, pushing the boundaries of AI-assisted figure creation and impacting the efficiency and inclusivity of scientific publishing.

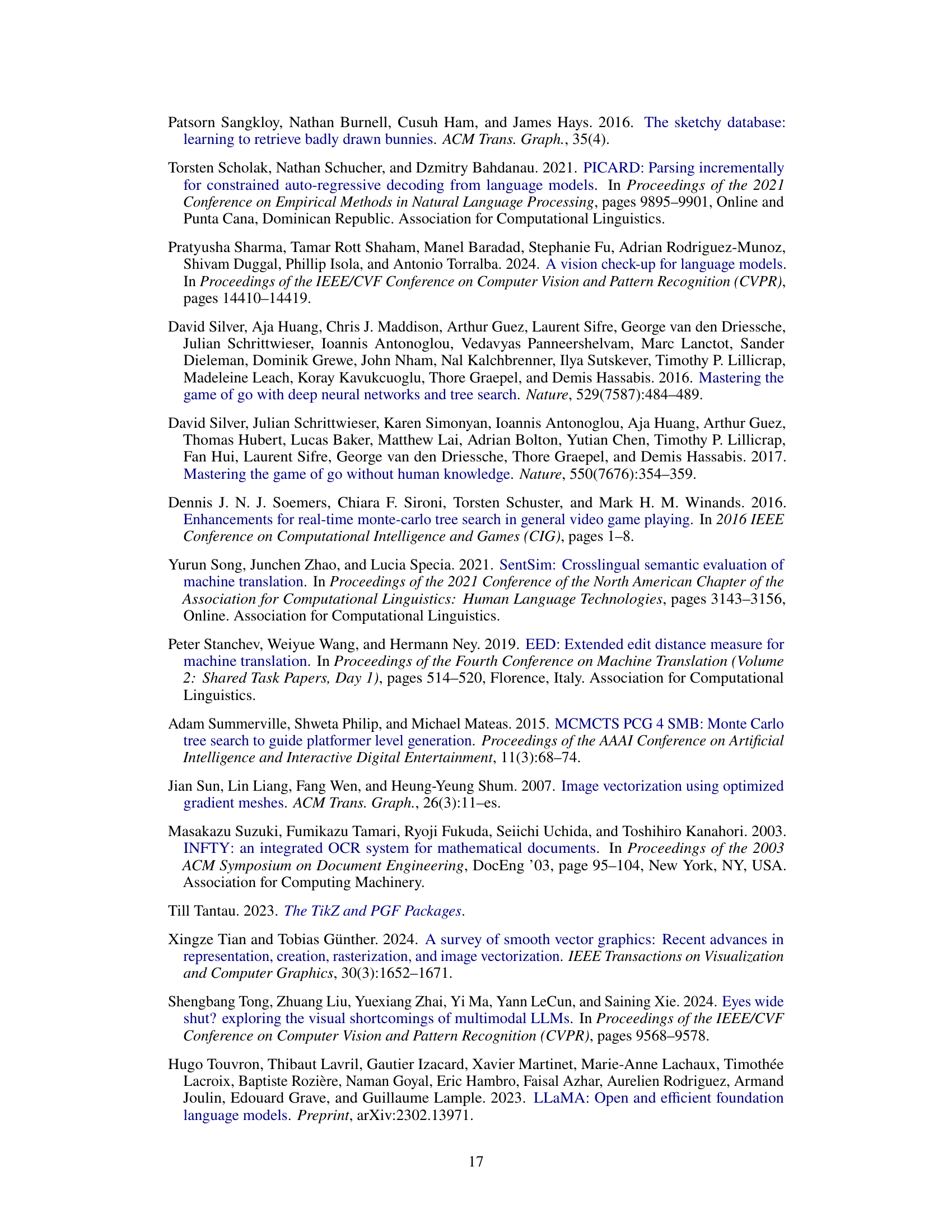

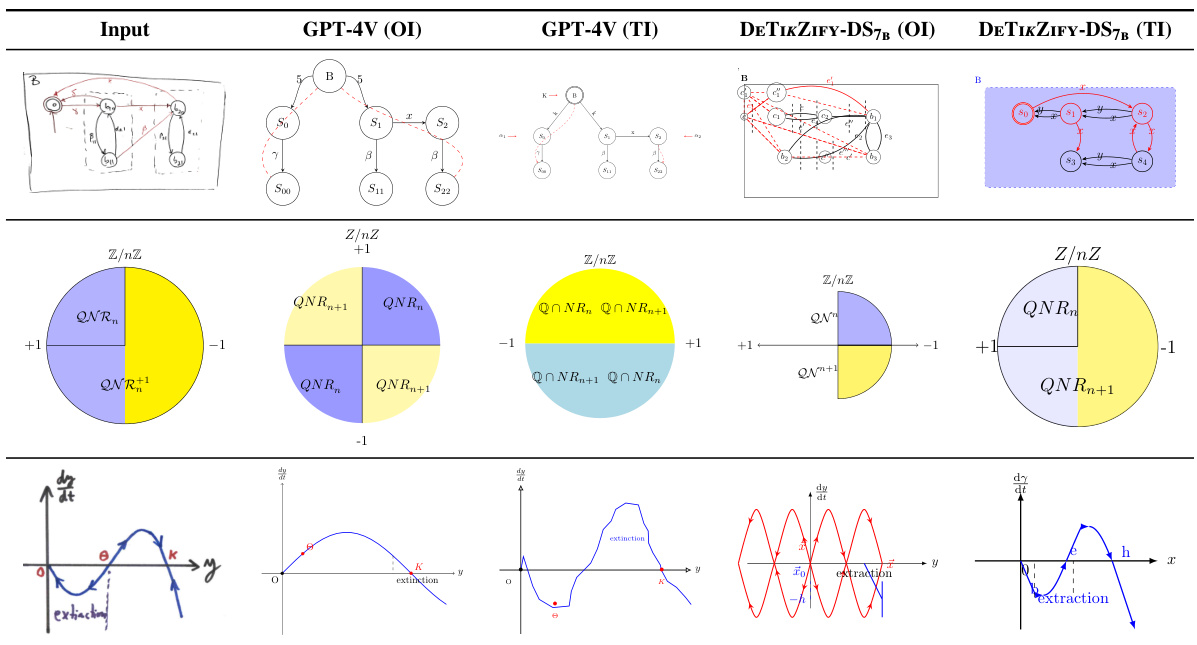

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the architecture of DETIKZIFY, a multimodal language model. It shows how DETIKZIFY takes either a sketch or an existing figure as input. These inputs are processed by the model, which generates a TikZ program as output. The TikZ program is then compiled using a LATEX engine. The resulting output is used to generate a reward signal that is fed back into the model via a Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) algorithm, allowing for iterative refinement of the generated TikZ program until satisfactory results are achieved.

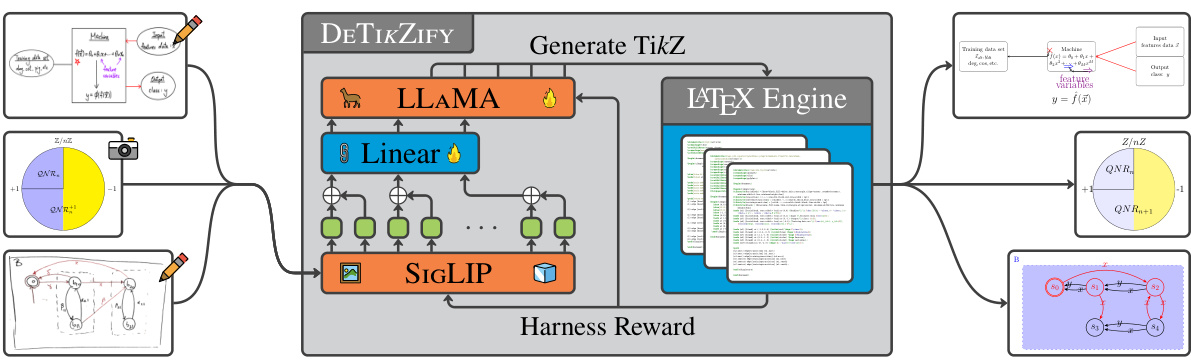

This table shows the number of unique TikZ graphics included in the DATIKZv2 dataset, broken down by source (curated, TeX.SE, arXiv, artificial). It also provides a comparison to the number of graphics in the previous version of the dataset, DATIKZv1, highlighting the significant increase in size of the DATIKZv2 dataset.

In-depth insights#

Multimodal Synthesis#

Multimodal synthesis, in the context of a research paper, likely refers to the generation of outputs using multiple input modalities. This approach is particularly powerful when dealing with complex data types like scientific figures, which contain both visual and semantic information. A model capable of multimodal synthesis could take a hand-drawn sketch and textual description as input to generate a precise and semantically accurate scientific figure in a format such as TikZ. This would require the model to fuse visual and textual representations effectively, understanding both the abstract concept implied by the sketch and the detailed semantics from the text, and then translate this combined understanding into a precise, executable program. Successful multimodal synthesis in this domain would represent a significant advancement, streamlining the often tedious process of producing high-quality scientific figures. The challenges lie in the complexity of effectively integrating and weighting different modalities, handling ambiguities and inconsistencies in the input, and ensuring the output program is syntactically and semantically correct. The impact extends beyond ease-of-use for scientists, as such a system may assist in accessibility, data archiving, and potentially automation of figure generation.

MCTS Inference#

The heading ‘MCTS Inference’ suggests the paper employs Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), a decision-making algorithm, for inference. This is particularly relevant in scenarios with high-dimensional spaces or complex decision processes, common in tasks like synthesizing graphics programs. MCTS’s iterative nature, building a search tree, is likely leveraged to refine the generated TikZ code, improving accuracy and correctness. The use of MCTS is a key innovation, suggesting the model doesn’t simply generate code once but iteratively refines it, enhancing quality. This approach may address the probabilistic nature of large language models, mitigating errors and ensuring more valid outputs. The algorithm’s ability to handle complex, non-deterministic problems makes it well-suited for the challenge of graphics program synthesis. Furthermore, the paper likely details how MCTS interacts with the multimodal model architecture to effectively guide the code generation process. Evaluation likely involves comparing results of both MCTS-guided and direct generation, highlighting the performance boost achieved through iterative refinement.

Large TikZ Dataset#

The creation of a large-scale TikZ dataset is a significant contribution to the field of scientific visualization and code generation. Such a dataset would enable researchers to train more sophisticated models for automatically generating TikZ code from various input formats, such as sketches or natural language descriptions. The size and diversity of the dataset are critical; a larger dataset allows for training more robust models that can better generalize to unseen data and handle a wider range of scientific figure types. Careful curation of the dataset is also crucial, ensuring that the TikZ code is well-formed, efficient, and follows best practices. Furthermore, diversity in the types of figures represented in the dataset is key to training models capable of generating a variety of scientific visualizations. The availability of such a dataset would undoubtedly accelerate progress in the area of automated figure generation, ultimately making it easier for researchers to create publication-ready figures.

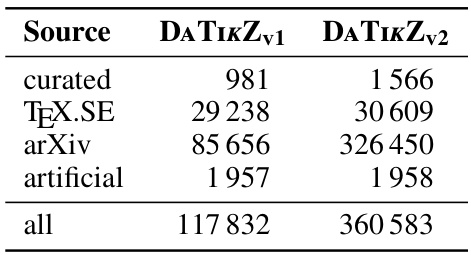

Human Evaluation#

A human evaluation section in a research paper is crucial for validating the results and demonstrating practical applicability. It provides an independent assessment of model performance, going beyond the limitations of purely automated metrics. A well-designed human evaluation should involve carefully selected participants, ideally with relevant expertise, and clearly defined evaluation tasks and scoring criteria. The number of participants should be sufficient to ensure statistical reliability, and the evaluation design should be robust and control for potential biases. In the context of comparing automated figure generation models, a human evaluation could focus on assessing the quality, correctness, and aesthetic appeal of the generated figures. Qualitative aspects like visual clarity, adherence to scientific conventions, and ease of interpretation are also important factors to consider. By incorporating human judgment, research findings gain more credibility and provide a better understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of the generated figures. Qualitative feedback from the human evaluators provides valuable insights for model improvement. Quantitative data from the human evaluation, such as scores on multiple criteria, can be analyzed statistically to understand the degree to which different models perform and to identify any areas needing further refinement.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section suggests several promising avenues. Extending DETIKZIFY to other graphics languages like MetaPost, PSTricks, or Asymptote is crucial for broader applicability. Exploring alternative reward signals beyond perceptual similarity, such as per-pixel measures or point cloud metrics, could significantly enhance the model’s accuracy and fidelity. Incorporating reinforcement learning with direct preference optimization may further boost the system’s iterative refinement capabilities. Finally, investigating mixed-modality inputs (combining text, images, and potentially even audio) presents exciting possibilities for even more nuanced and powerful scientific figure generation.

More visual insights#

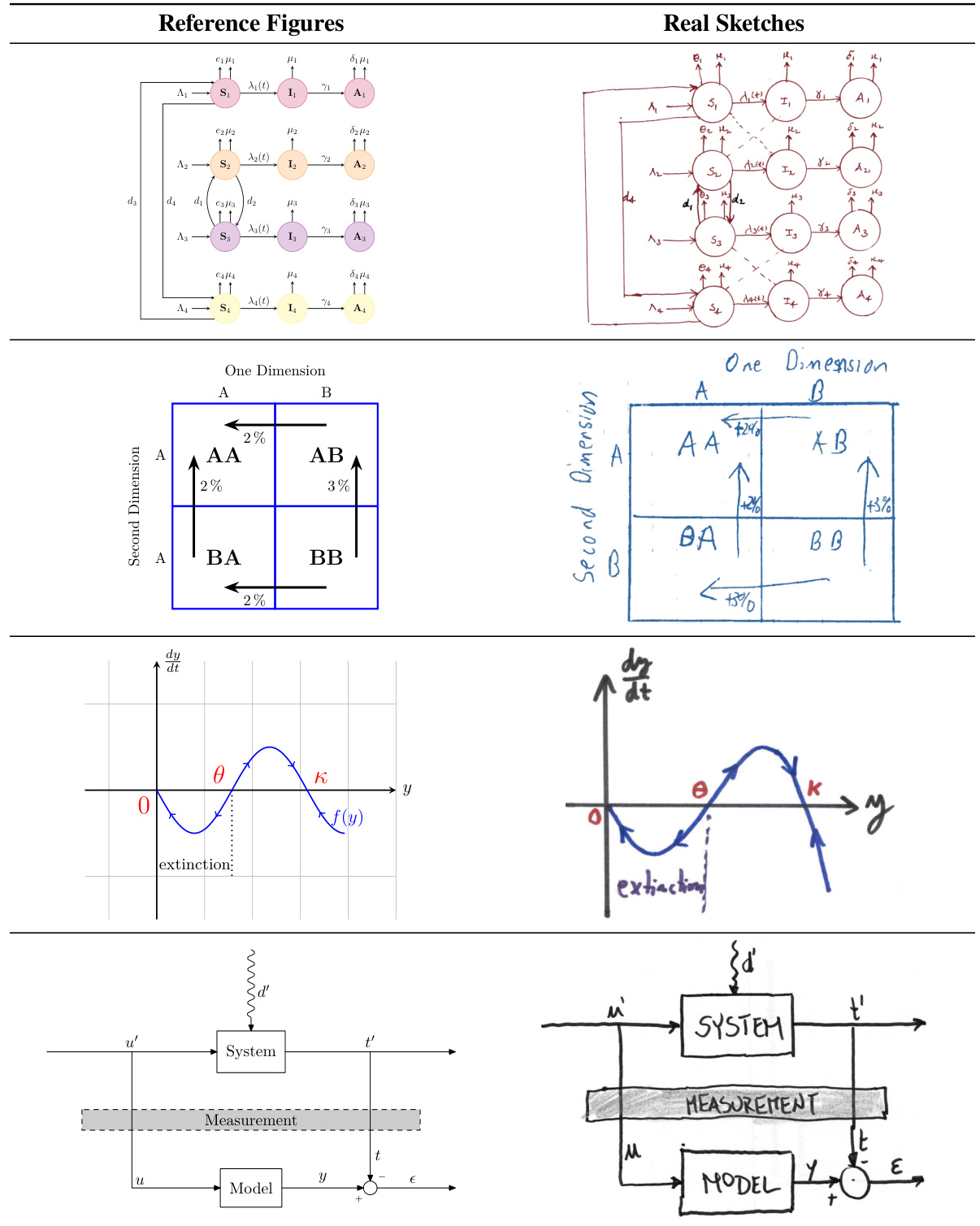

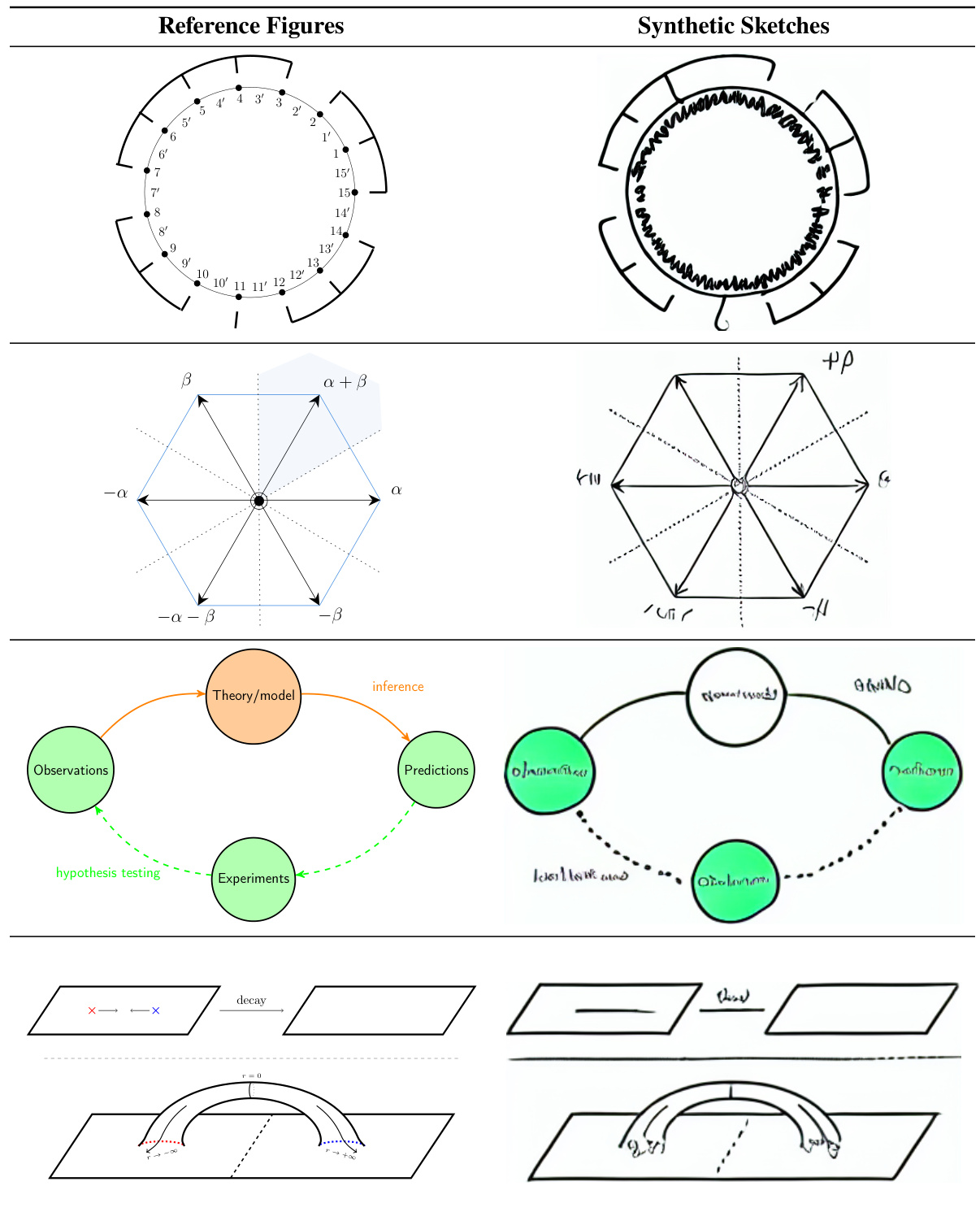

More on figures

The figure illustrates the architecture of DETIKZIFY, a multimodal language model. It takes sketches or figures as input and generates TikZ programs. These programs are then compiled by a LATEX engine, and the result is used to provide a reward signal to the model. The model uses Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) to refine the output iteratively until satisfactory results are obtained.

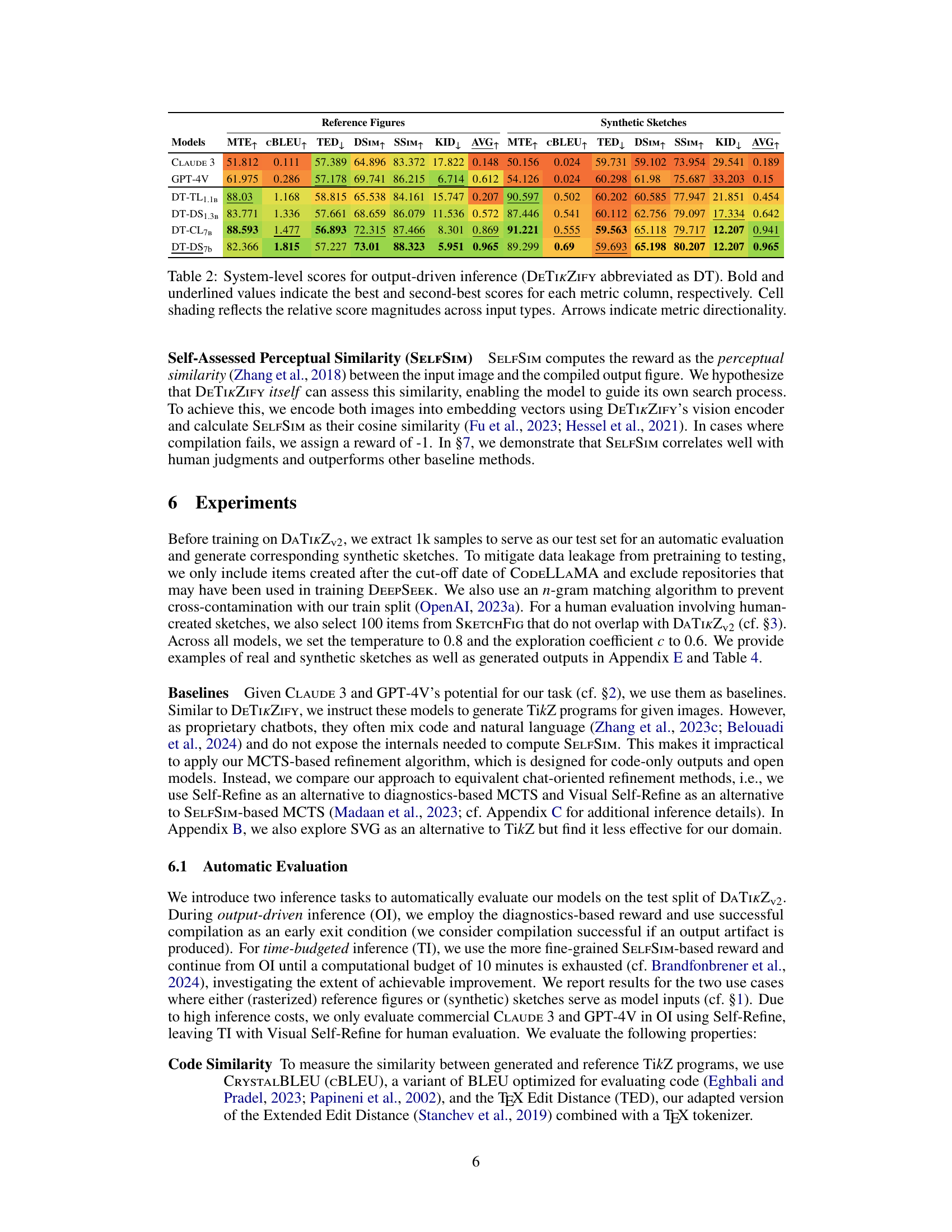

This figure visualizes the performance of different text generation strategies over time using two methods: kernel density estimation and log-linear regression. The left panel shows a bivariate distribution of Best-Worst Scaling (BWS) scores, illustrating the relationship between the quality of generated figures (higher scores are better) for reference figures and human sketches. The right panel presents a log-linear regression analysis of the SELFSIM reward scores across time for both sampling and Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) methods. The results highlight the consistent improvement in performance over time seen with the MCTS algorithm, outperforming the sampling-based approach.

The figure illustrates the DETIKZIFY architecture, a multimodal language model that takes sketches or figures as input and generates TikZ programs. These programs are then compiled using a \LaTeX engine, providing a reward signal that is used by a Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) algorithm to iteratively refine the generated TikZ program until a satisfactory result is obtained. The process involves a vision encoder, a language model (such as LLAMA), and a reward module that incorporates feedback from the \LaTeX compilation.

The figure illustrates the architecture of DETIKZIFY, a multimodal language model. It takes sketches or figures as input, processes them using a combination of a large language model (LLM) and a vision encoder, and outputs TikZ programs. These programs are then compiled using a LaTeX engine, providing feedback to the model through Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS). The MCTS algorithm allows for iterative refinement of the output until satisfactory results are obtained.

The figure illustrates the architecture of DETIKZIFY, a multimodal language model. It takes either a sketch or an existing figure as input. The model then generates a TikZ program (a type of code for creating graphics). This program is then compiled using a LATEX engine. The output of the LATEX compilation provides a reward signal, used by the Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) algorithm to iteratively refine the generated TikZ program until it’s satisfactory.

This figure shows the architecture of DETIKZIFY, a multimodal language model that synthesizes scientific figures as TikZ programs. It takes sketches or figures as input, processes them using an LLAMA language model and a SIGLIP vision encoder, and generates TikZ code that is then compiled using a \LaTeX engine. The resulting output is used to provide a reward signal, which is fed back into the model through a Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) algorithm. This iterative refinement process continues until satisfactory results are obtained.

The figure illustrates the DETIKZIFY architecture, a multimodal language model that takes sketches or figures as input and generates TikZ programs as output. The TikZ code is then compiled by a LATEX engine, which provides feedback to the model through a Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) algorithm. This iterative refinement process continues until satisfactory results are achieved.

This figure illustrates the architecture of DETIKZIFY, which is a multimodal language model designed for automatic synthesis of scientific figures as semantics-preserving TikZ graphics programs. It takes as input either a sketch or an existing figure. The model uses a LATEX engine to compile the generated TikZ code, providing a reward signal that is fed back to the model via a Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) algorithm. This iterative refinement process allows the model to improve its outputs until they are satisfactory.

More on tables

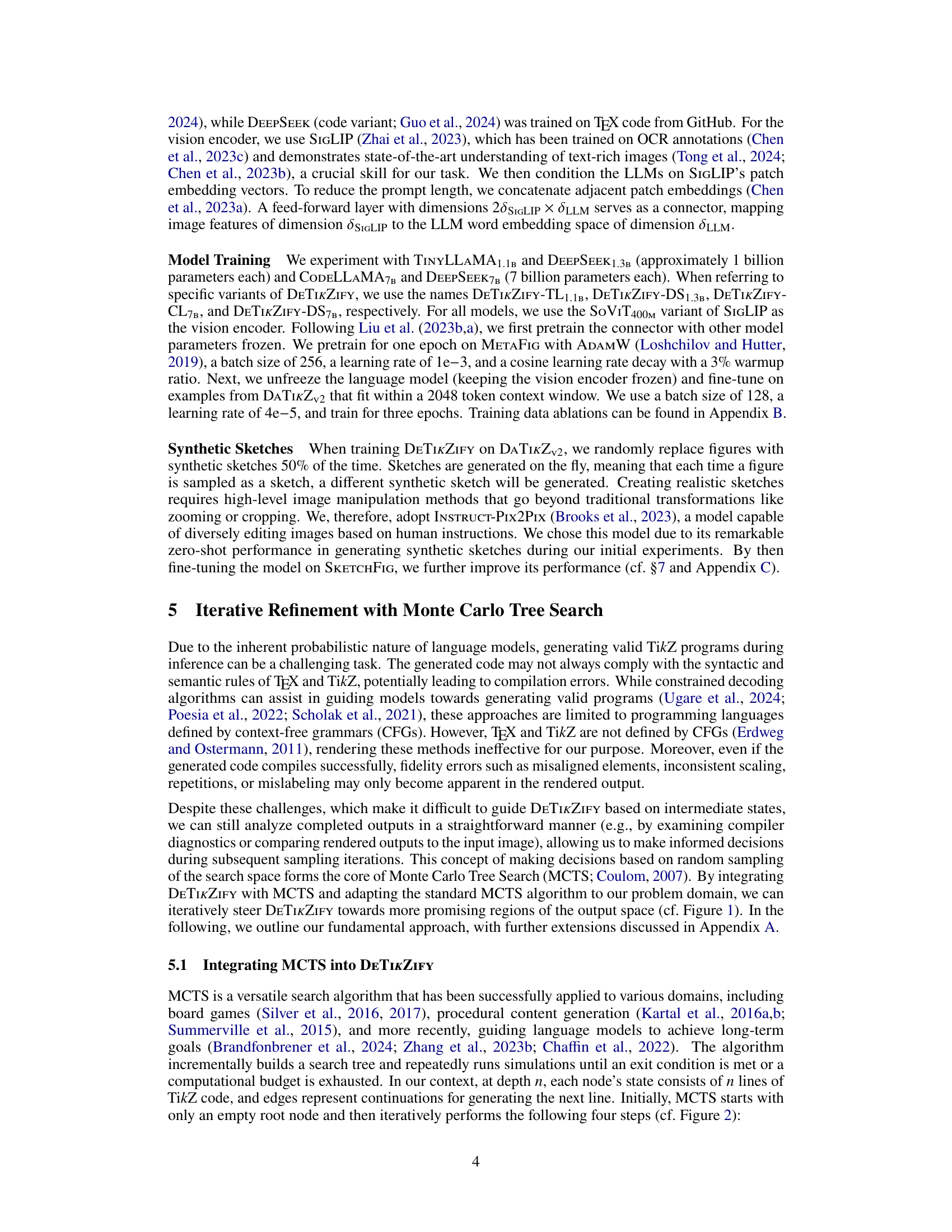

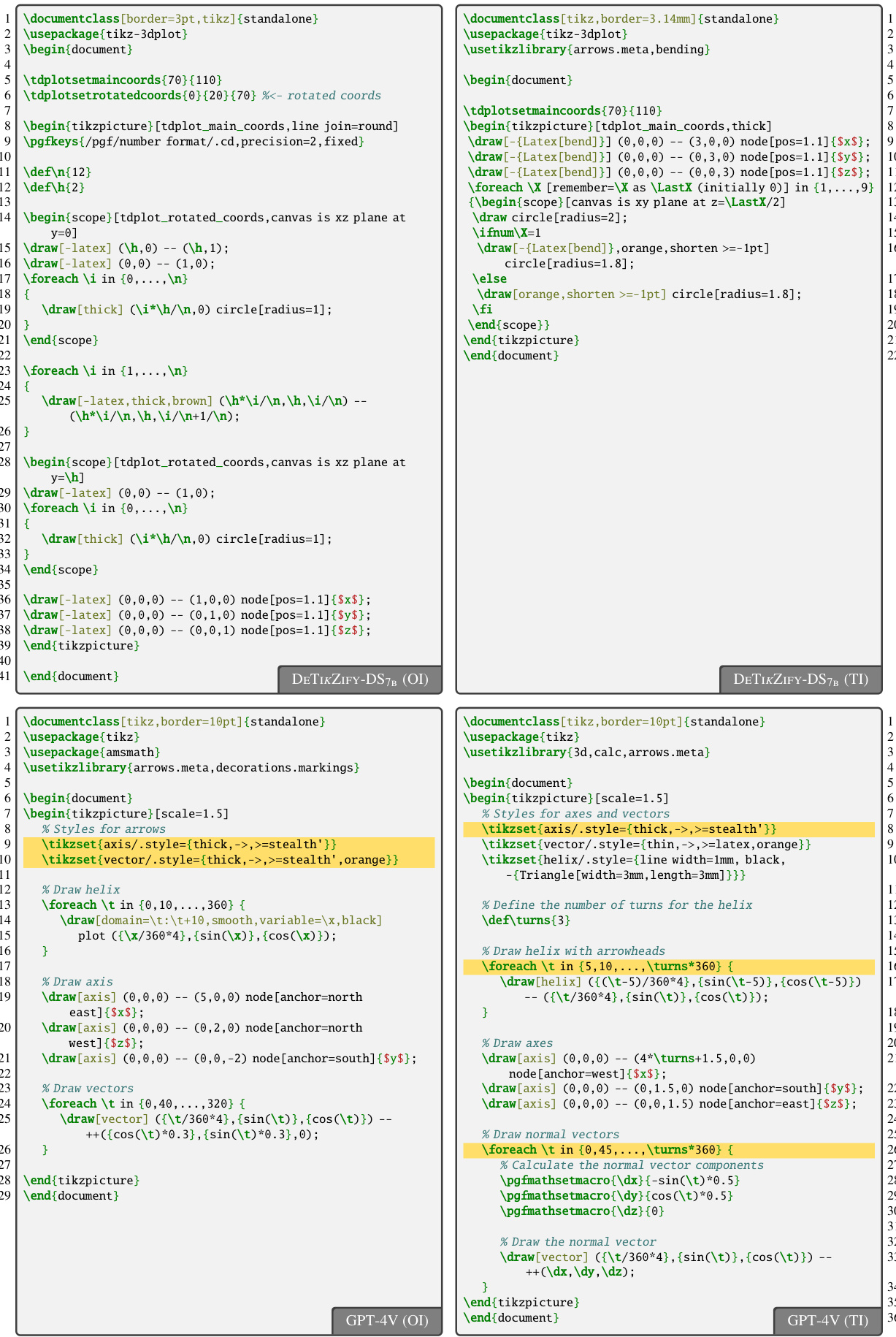

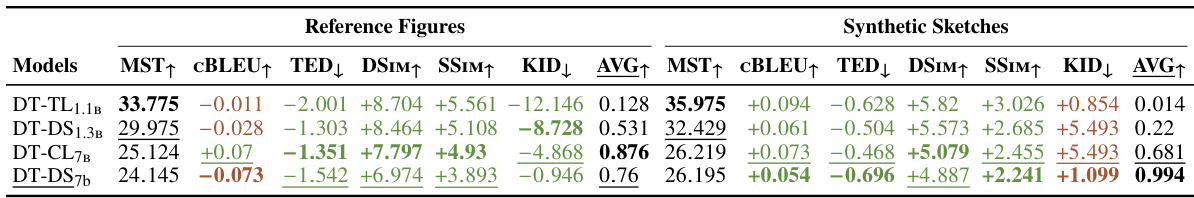

This table presents the results of an automatic evaluation of DETIKZIFY and several baselines on the task of generating TikZ code from images. The evaluation focuses on output-driven inference (OI), where the models generate code until a successful compilation is achieved. The table shows various metrics for evaluating the generated code, including: Mean Token Efficiency (MTE), which measures the efficiency of code generation; CrystalBLEU (cBLEU), which measures the similarity between generated and reference code; TEX Edit Distance (TED), measuring the edit distance between generated and reference code; DREAMSIM, SELFSIM, and SSIM, which are perceptual similarity metrics comparing generated and reference images; and Kernel Inception Distance (KID), which measures the distribution difference between the generated and reference images. Higher scores for MTE, cBLEU, DSIM, SSIM, and AVG are better, while lower scores for TED and KID are preferable. The table breaks down the results for models using either reference figures or synthetic sketches as input.

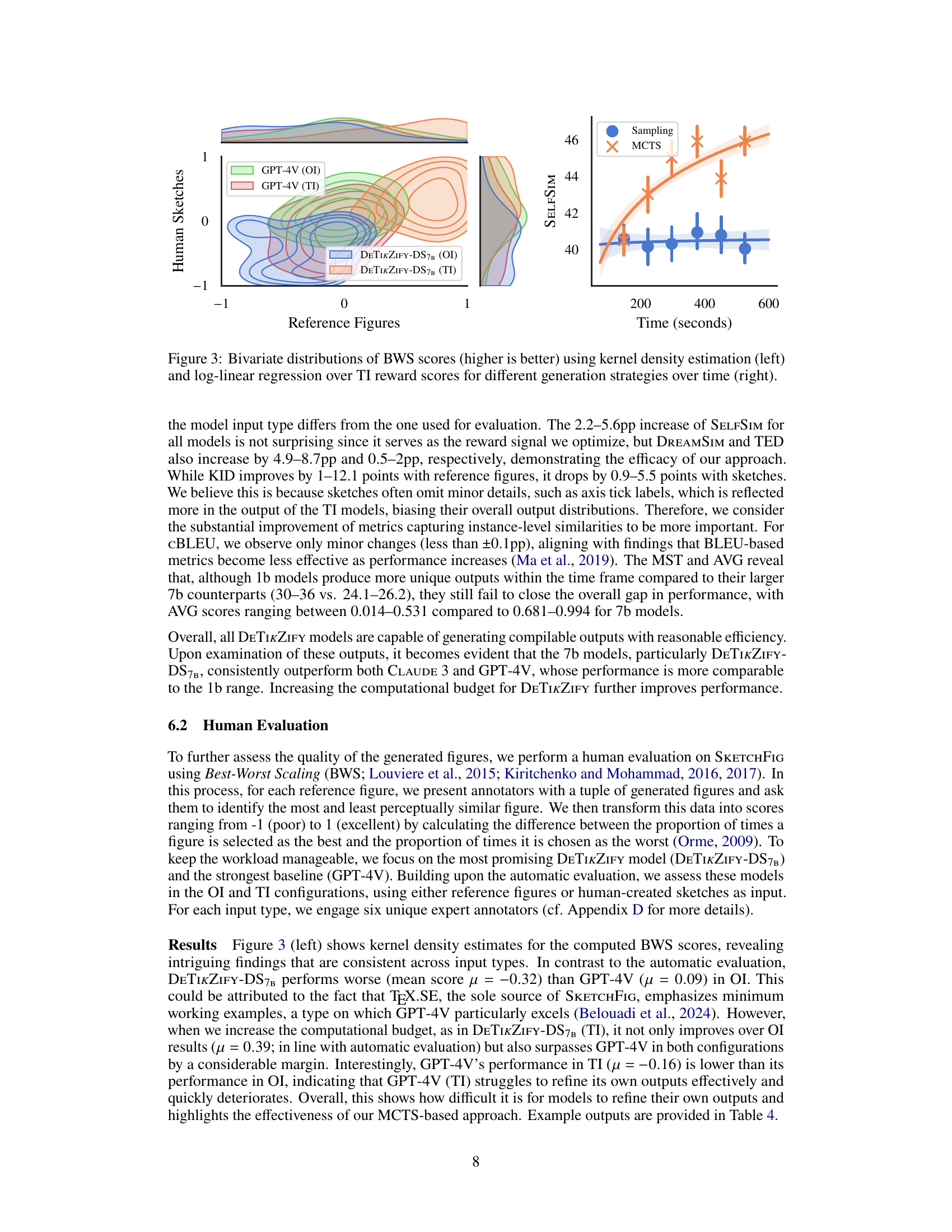

This table presents the results of a time-budgeted inference experiment, comparing the performance of four different DETIKZIFY models (with varying sizes and training data) on two tasks: generating TikZ code from reference figures and from synthetic sketches. It shows both relative changes (compared to the output-driven inference results in Table 2) and absolute scores for various metrics, including code similarity (CBLEU, TED), image similarity (DSIM, SSIM, KID), and overall average similarity (AVG). The table highlights the best performing models for each metric and input type (figures vs. sketches).

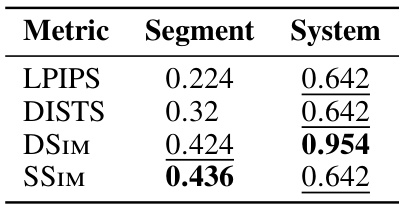

This table shows the correlation between image similarity metrics (LPIPS, DISTS, DSIM, SSIM) and human judgments at both segment and system levels. The higher the correlation value, the better the metric aligns with human perception of similarity. The table highlights that SELFSIM shows the strongest correlation at the segment level, while DREAMSIM has the highest correlation at the system level, indicating their relative effectiveness in evaluating image similarity.

This table presents the performance comparison of different models on the task of generating TikZ code from images. The models compared include CLAUDE 3, GPT-4V, and several variations of the DETIKZIFY model (with different sizes and training configurations). The metrics used to evaluate the generated TikZ code are Mean Token Efficiency (MTE), CrystalBLEU (cBLEU), TEX Edit Distance (TED), DREAMSIM (DSIM), Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), Kernel Inception Distance (KID), and the average of all similarity metrics (AVG). The table shows results for both reference figures and synthetic sketches as input to the models.

This table presents the results of an ablation study conducted on the DETIKZIFY-TL1.1B model using output-driven inference. It investigates the impact of removing either sketch-based training or connector pre-training from the model’s training process. The table shows the relative changes in various metrics (MTE, cBLEU, TED, DSIM, SSIM, KID) for both reference figures and synthetic sketches as input when comparing the full training to the models trained without sketch-based training or without connector pre-training. Positive changes are highlighted in green, while negative changes are in red. Reference scores are taken from Table 2.

This table presents the quantitative results of the DETIKZIFY model’s performance on the output-driven inference task. It compares DETIKZIFY against two baseline models (CLAUDE 3 and GPT-4V) across various metrics. These metrics assess both the code quality (MTE, cBLEU, TED) and the visual similarity between the generated and reference figures (DSIM, SSIM, KID, AVG). The table highlights the superior performance of DETIKZIFY, particularly the larger variants, in generating high-quality and visually accurate TikZ code from both reference figures and synthetic sketches.

Full paper#