↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many studies show language models gain capabilities through emergent algorithmic mechanisms, but a theoretical understanding remains elusive. Existing theoretical work on attention layers lack the precision to capture sharp transitions. This study aims to analyze the learning of semantic attention in a solvable model and how it relates to positional attention.

The researchers use a solvable model of dot-product attention with tied low-rank query and key matrices, focusing on the asymptotic limit of high-dimensional data and large sample sizes. They show that, depending on the data complexity, the model learns either a positional attention mechanism (tokens attending based on their position) or a semantic attention mechanism (tokens attending based on their meaning). They find a phase transition between these mechanisms, with semantic attention emerging as sample complexity increases and outperforming the purely positional model when sufficient data is available. This reveals a sharp transition that explains the improvement in LLM capabilities. This approach and analysis of the learning mechanisms bridges the gap between theory and experimental findings in the field of attention.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it provides the first theoretical explanation for the emergence of sharp phase transitions in attention mechanisms. This helps explain how language models develop capabilities, bridging the gap between empirical observations and theoretical understanding. It opens avenues for designing more efficient and interpretable AI systems.

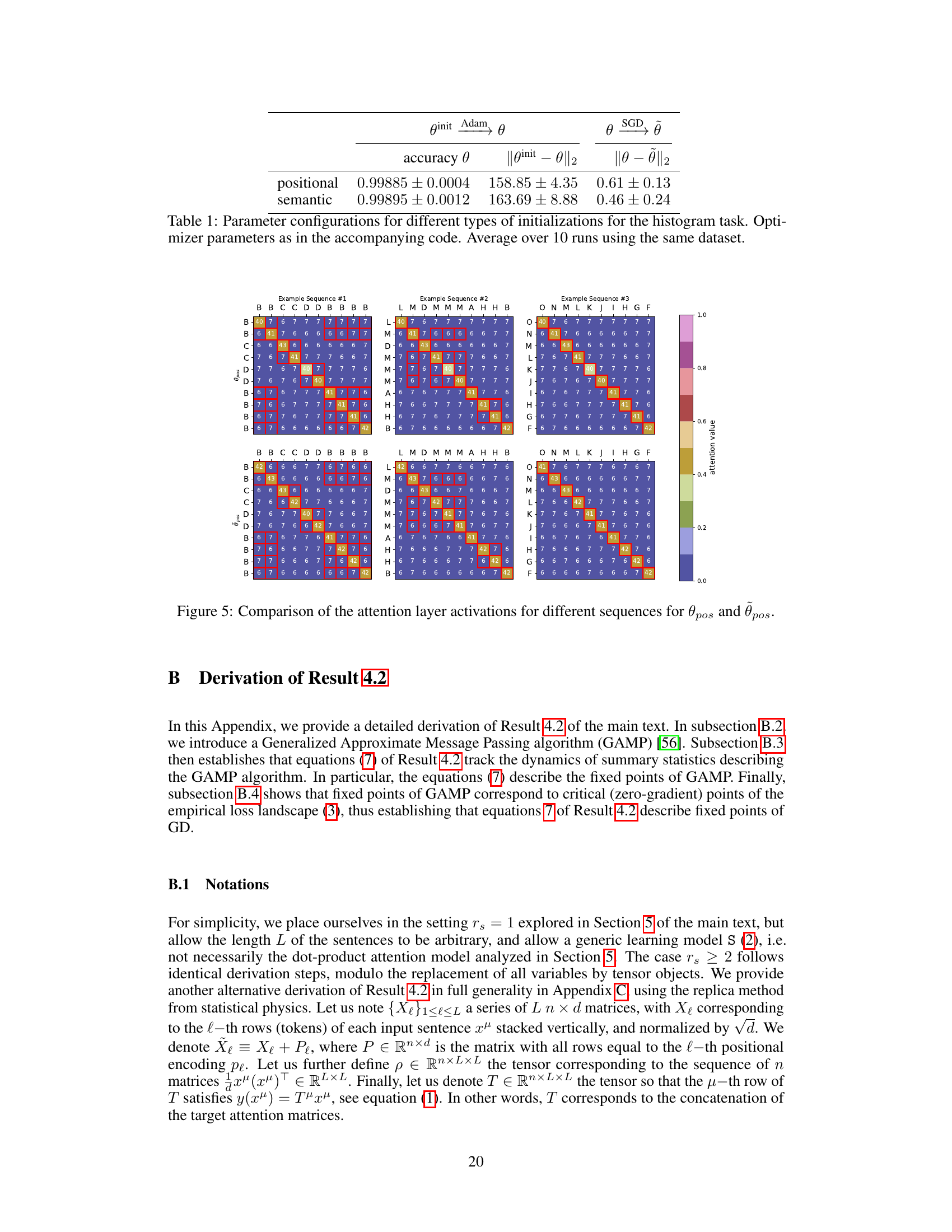

Visual Insights#

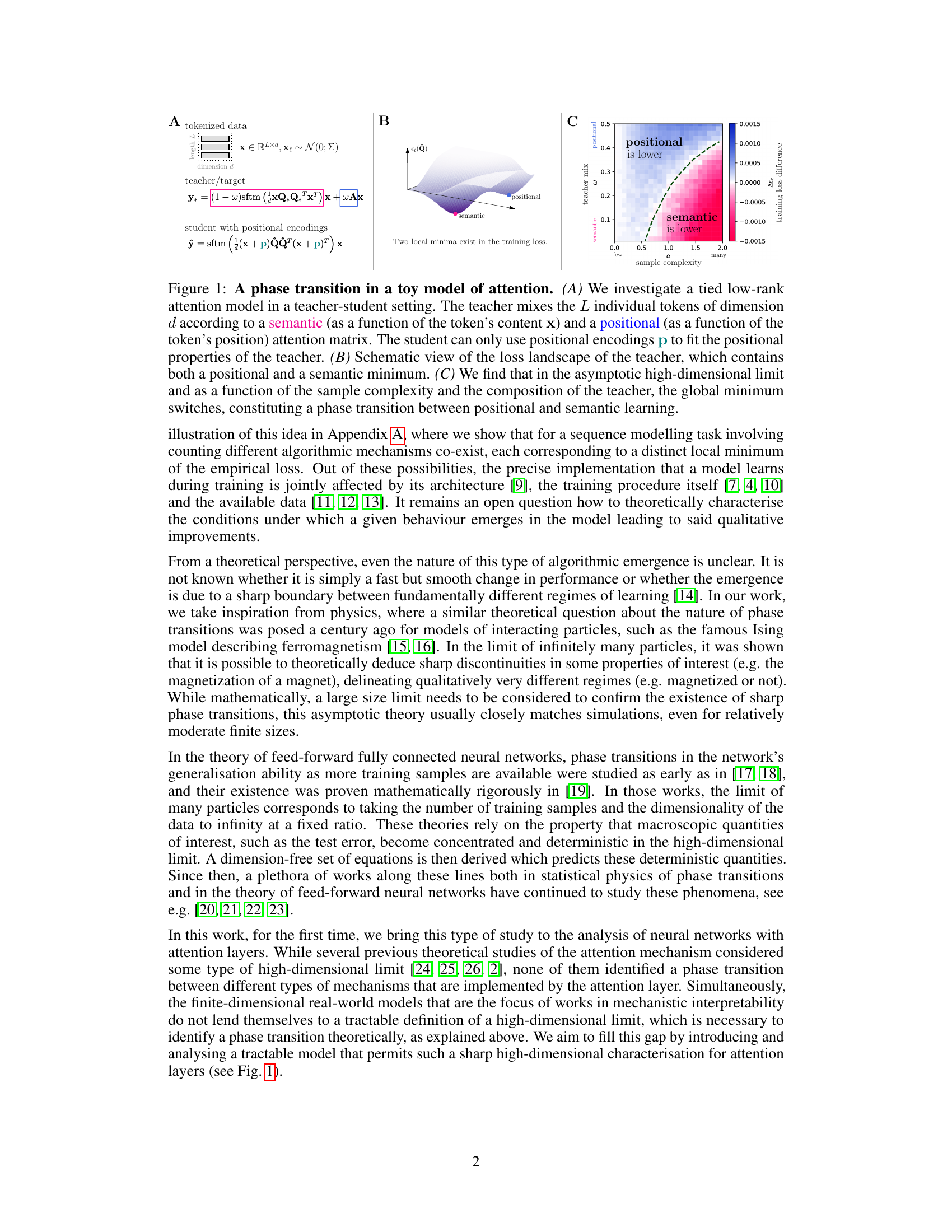

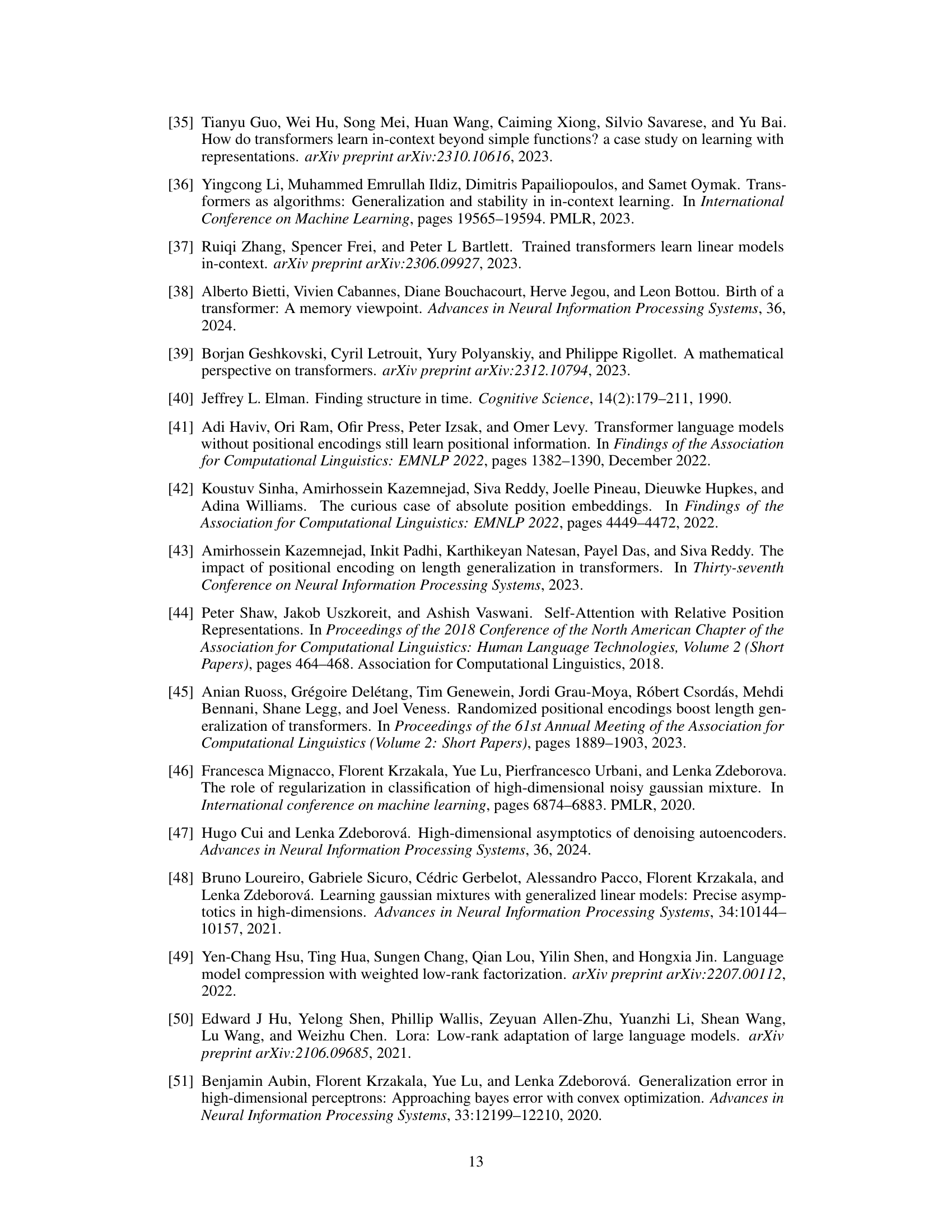

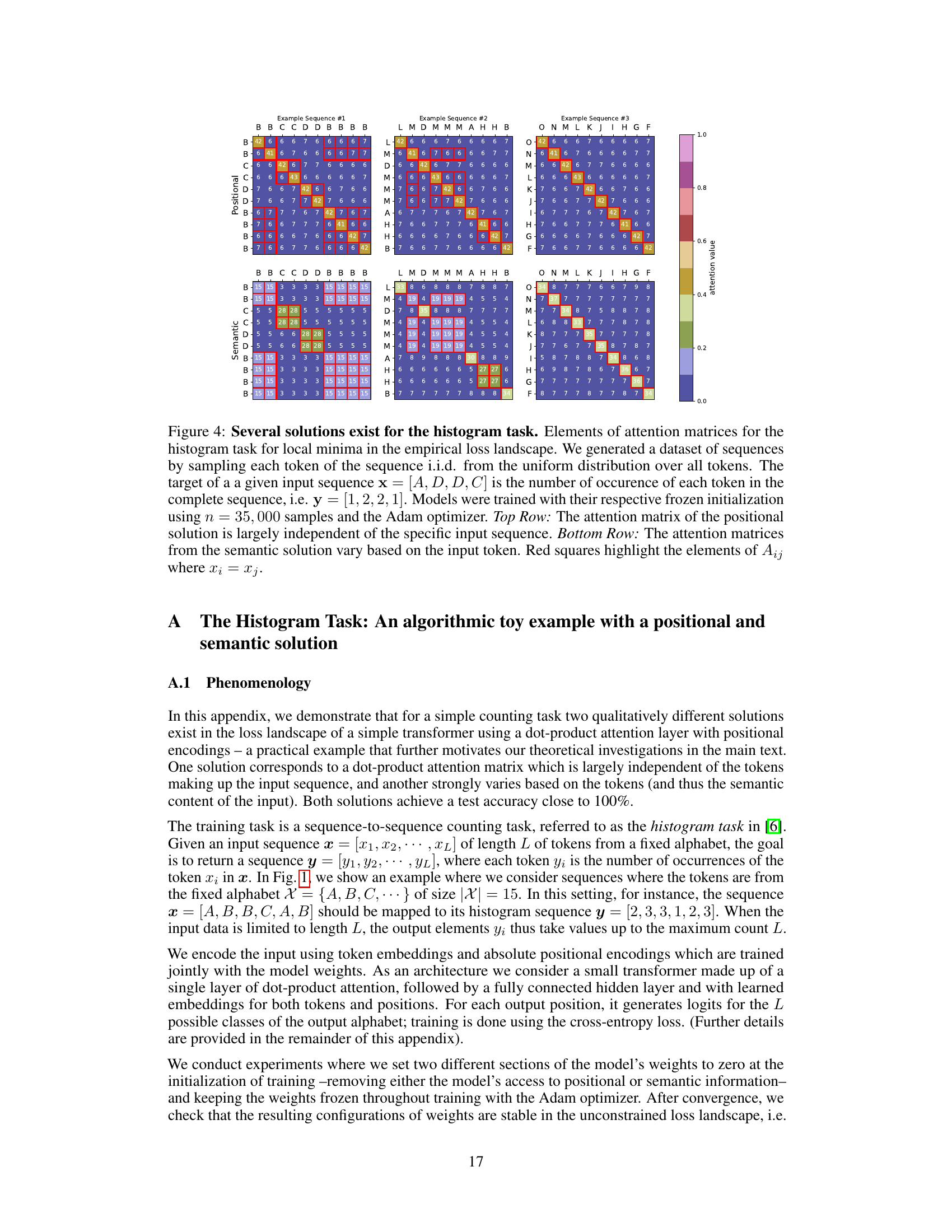

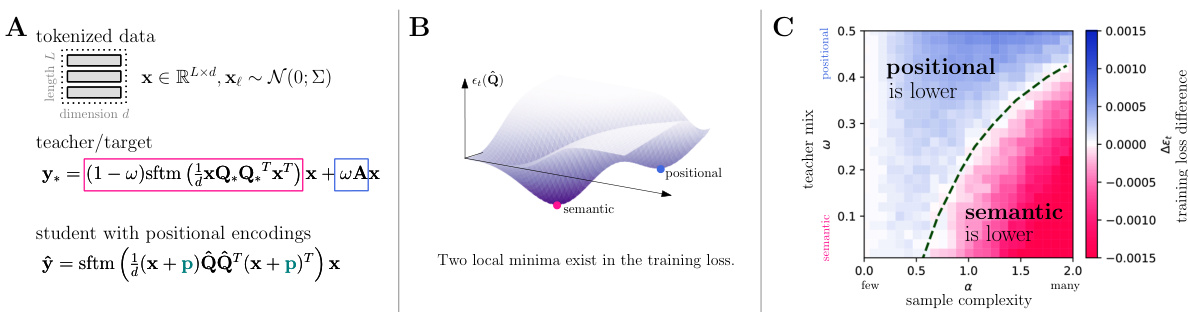

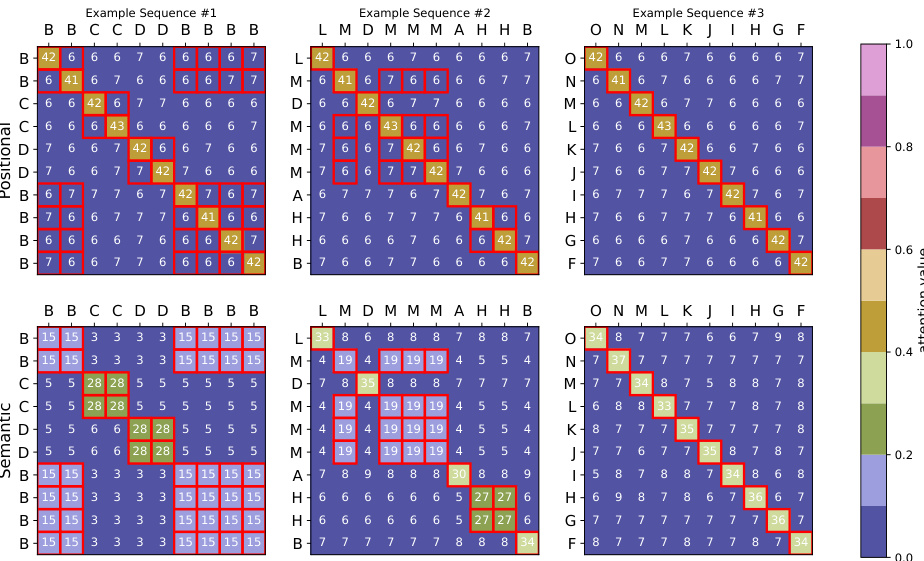

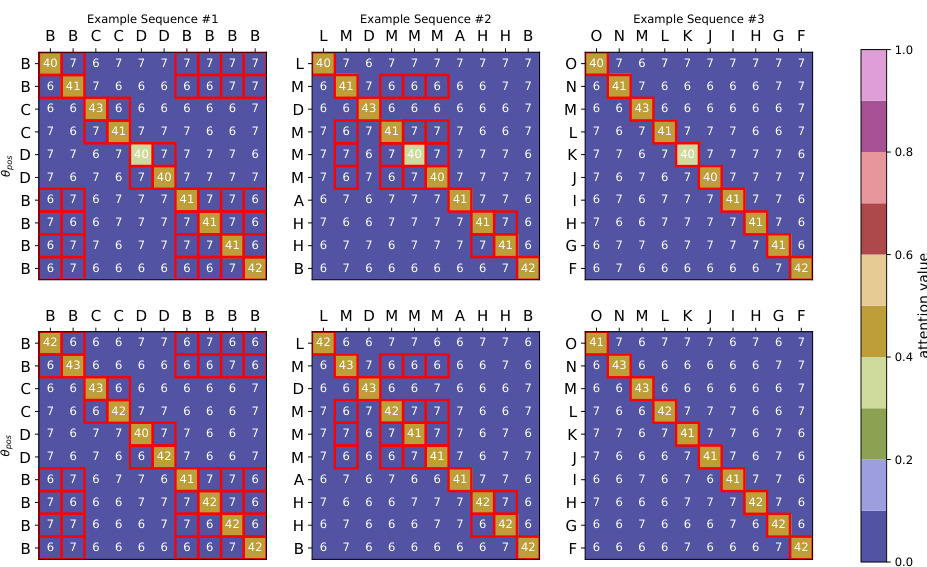

This figure shows a phase transition between positional and semantic learning in a toy model of dot-product attention. Panel A illustrates the model setup, where a teacher model uses both positional and semantic information to mix tokens, while a student model only uses positional encodings. Panel B shows a schematic of the loss landscape with both positional and semantic minima. Panel C demonstrates the phase transition, showing how the global minimum switches from positional to semantic learning as the sample complexity increases.

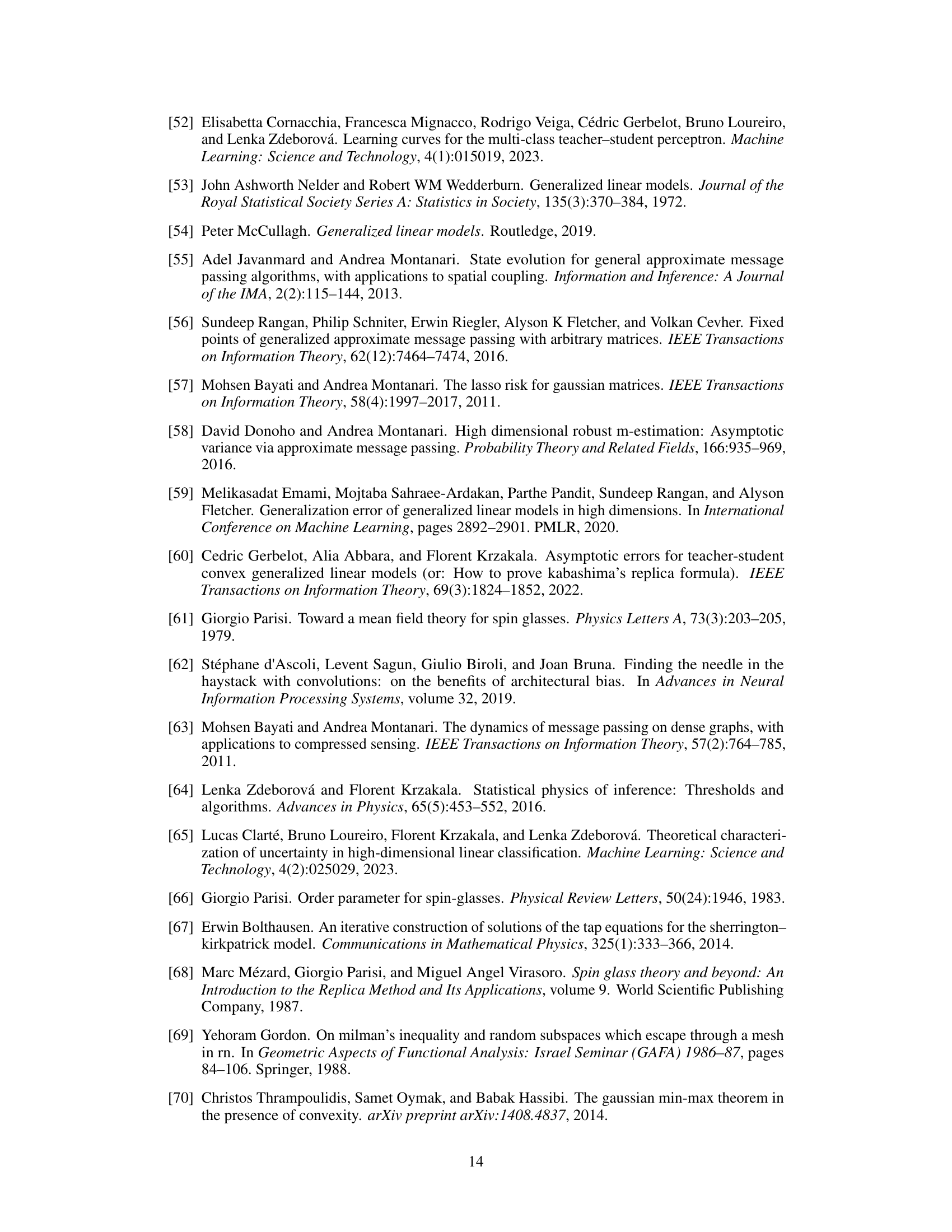

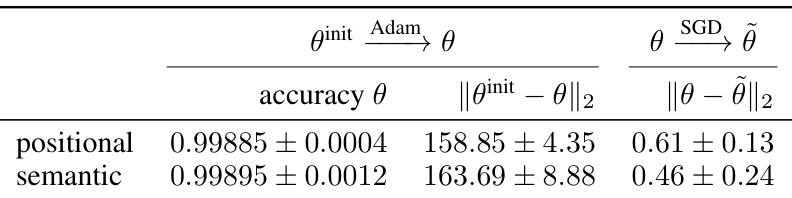

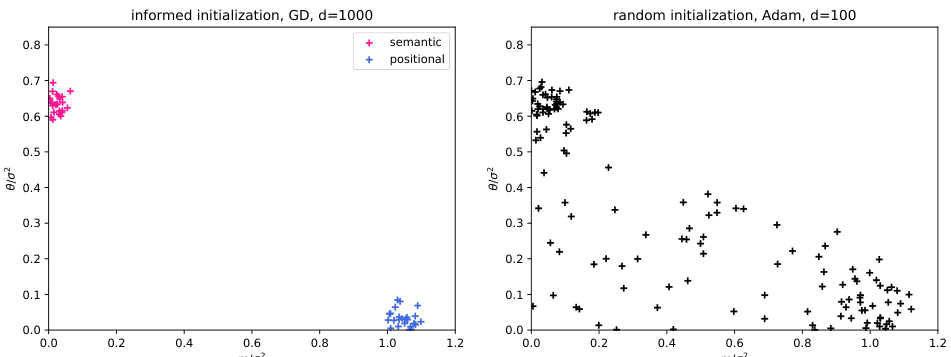

This table shows the results of different initialization methods for training a model on the histogram task. It compares positional and semantic initializations using the Adam and SGD optimizers. The table presents the accuracy achieved by each initialization, along with the Euclidean distance between the initial and final weights, providing insight into the convergence behavior of different training approaches.

In-depth insights#

Phase Transition#

The research paper investigates a fascinating phenomenon: a phase transition between positional and semantic learning within a solvable model of dot-product attention. This transition, driven by sample complexity, reveals a crucial shift in how the attention mechanism operates. With limited data, the model prioritizes positional information, relying on the inherent order of tokens. However, as more data becomes available, a critical threshold is crossed. The model then transitions to a semantic approach, focusing on the meaning and relationships between words rather than their positions. This is a significant finding, suggesting that the capacity for nuanced semantic understanding in attention models is not an inherent property, but rather an emergent one. The emergence depends heavily on the availability of sufficient training data, implying that models with access to substantial corpora are more likely to exhibit sophisticated semantic abilities. This highlights the dynamic interplay between data availability and the model’s learning strategy, making the phase transition a crucial element in understanding the capabilities of attention-based systems.

Attention Model#

The research paper delves into the fascinating realm of attention mechanisms within neural networks, specifically focusing on the theoretical underpinnings of how these mechanisms enable complex tasks from textual data. The analysis centers around the emergence of semantic attention as opposed to positional attention and identifies conditions that govern this transition. The study employs a solvable model of dot-product attention, simplifying several aspects of the actual attention layers to allow rigorous theoretical analysis. High-dimensional analysis and a focus on phase transitions provide a unique perspective, borrowing methods from statistical physics, which has largely been absent from prior attention mechanism research. This approach enables identifying the conditions under which semantic or positional solutions are favored, characterized by sharp thresholds in sample complexity and other parameterizations. The model’s simplicity allows for a clear analytical understanding of the mechanism’s expressiveness, limitations, and interactions with positional encodings. The ultimate goal is to enhance comprehension of how attention layers learn complex tasks, moving beyond simply demonstrating improved performance and achieving a deeper theoretical understanding. Phase transitions are a key theoretical insight providing a sharp distinction between regimes favoring semantic versus positional attention. This research contributes significantly to improving understanding of the underlying mechanisms within attention models and how they relate to model performance.

High-D Limit#

The heading ‘High-D Limit’ likely refers to the paper’s high-dimensional asymptotic analysis. This technique is crucial for simplifying the complex, non-convex optimization problem inherent in training neural networks with attention. By taking the embedding dimension (d) and the number of training samples (n) to infinity while maintaining a constant ratio (a = n/d), the authors aim to obtain a tractable closed-form solution for the model’s behavior. This approach allows for a precise characterization of the global minimum of the empirical loss landscape, thus revealing the phase transitions between positional and semantic learning. The high-D limit is not just a mathematical trick but a powerful tool for gaining theoretical insights that would be otherwise impossible to achieve through empirical studies alone. The results obtained in this limit help clarify the role of data complexity in shaping the model’s learning dynamics and provide a rigorous theoretical foundation for understanding the emergent properties of attention mechanisms.

Semantic Attention#

Semantic attention, a crucial concept in the field of natural language processing, focuses on enabling neural networks to understand the meaning of words and their relationships within a sentence. Unlike positional attention, which relies on word order, semantic attention leverages the contextual meaning to determine the relationships. This approach is particularly valuable because it allows the model to capture more nuanced relationships between words that might not be apparent solely from position. For example, words that appear far apart in a sentence might have a strong semantic link; semantic attention helps the model recognize such long-range dependencies. However, implementing and training semantic attention models presents unique challenges. It typically requires significantly more data to learn the complex semantic relationships compared to the simpler positional relationships. Furthermore, the computational cost of semantic attention can be substantially higher than positional attention, necessitating efficient model design and optimization techniques. Nonetheless, the potential benefits of semantic attention make it a vibrant area of ongoing research and development, promising to significantly advance the capabilities of language models.

Future Work#

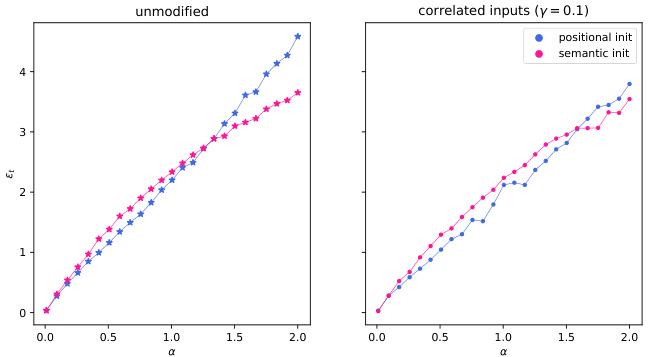

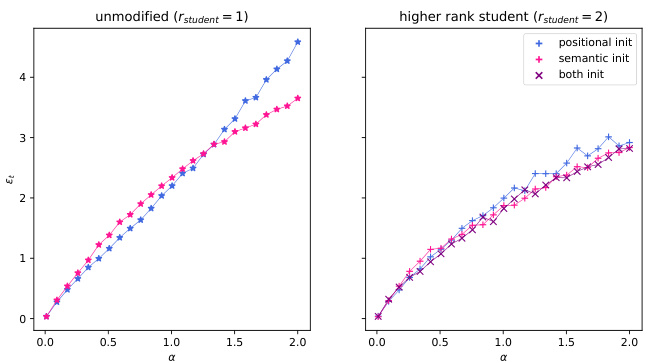

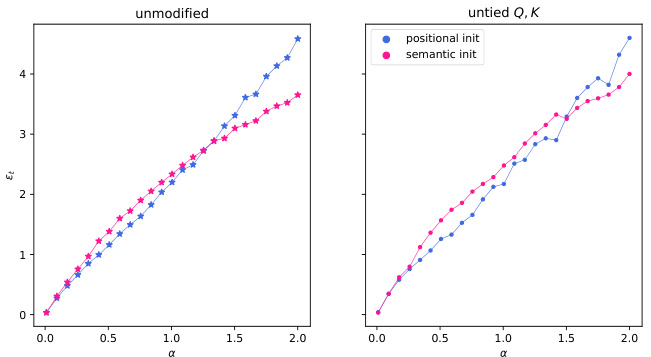

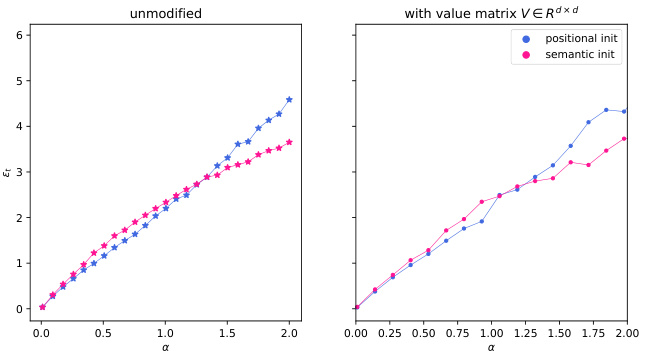

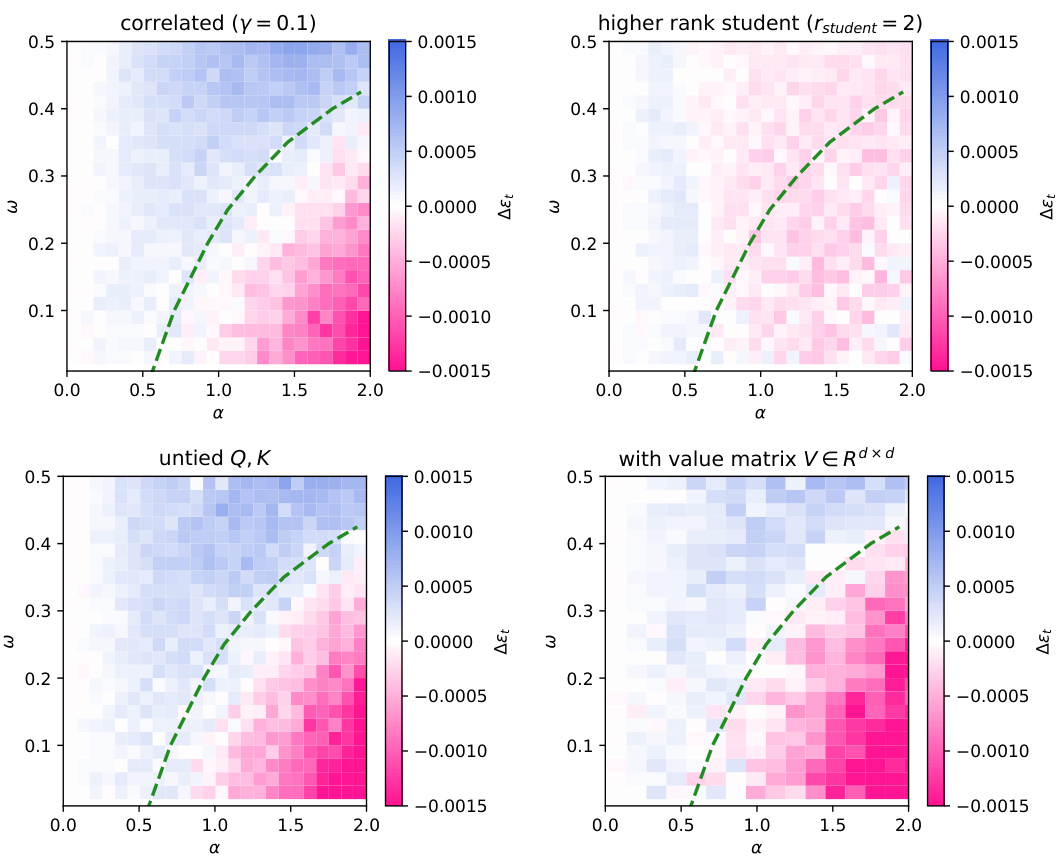

The paper’s core contribution is a theoretical analysis of a phase transition between positional and semantic attention mechanisms in a solvable model of dot-product attention. Future work could involve extending the model’s scope to encompass more realistic scenarios. This includes exploring more complex data models that incorporate inter-token correlations and handling more diverse types of textual data. Investigating the impact of various architectural decisions, such as the number of attention heads and layers, different activation functions, and untied query/key matrices, on this phase transition would offer valuable insights. A critical area for exploration is the dynamics of training algorithms, particularly gradient descent, to understand under what conditions the optimization landscape leads to the emergence of either positional or semantic attention. Additionally, future work could incorporate a more comprehensive theoretical framework that extends beyond the high-dimensional asymptotic limit analyzed in this paper to better capture the behavior of finite-dimensional models. Finally, empirical validation on a wider array of tasks and datasets would solidify the theoretical predictions of this study and possibly reveal additional nuances of this critical phase transition.

More visual insights#

More on figures

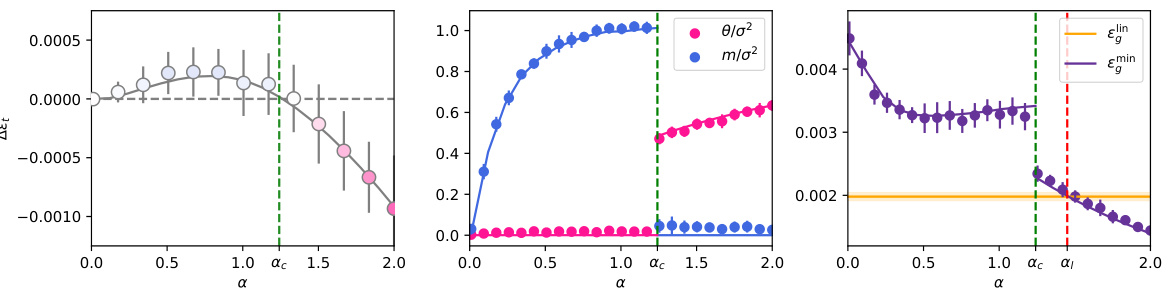

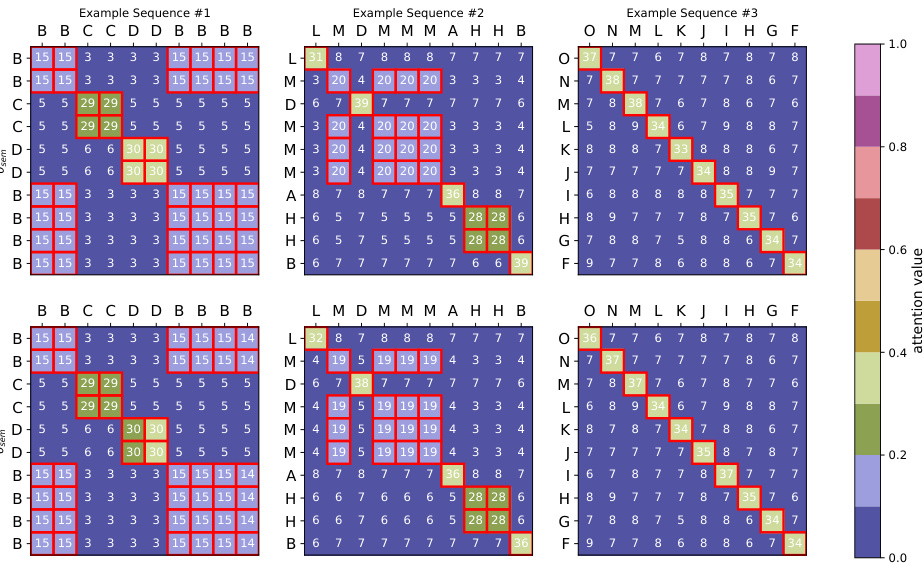

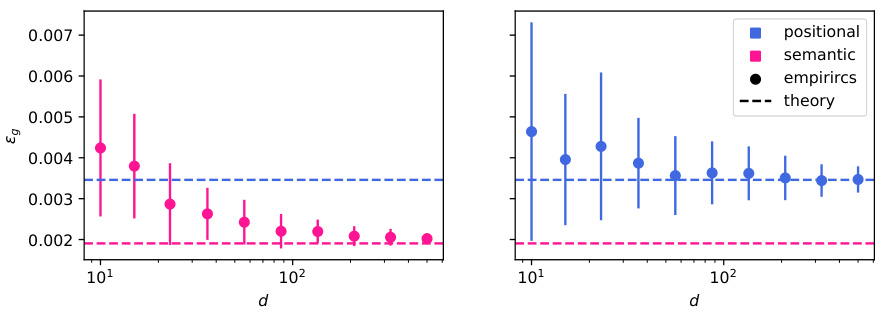

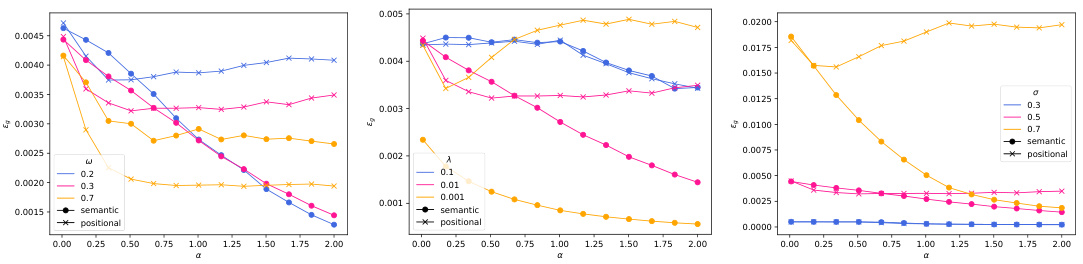

This figure shows a phase transition between positional and semantic learning in a toy model of attention. The left panel shows the difference in training loss between the semantic and positional solutions as a function of sample complexity (α). The middle panel shows the overlap between the learned weights and the target weights (θ) and the overlap between the learned weights and the positional embedding (m). The right panel compares the mean squared error (MSE) of the dot-product attention layer with a linear positional baseline.

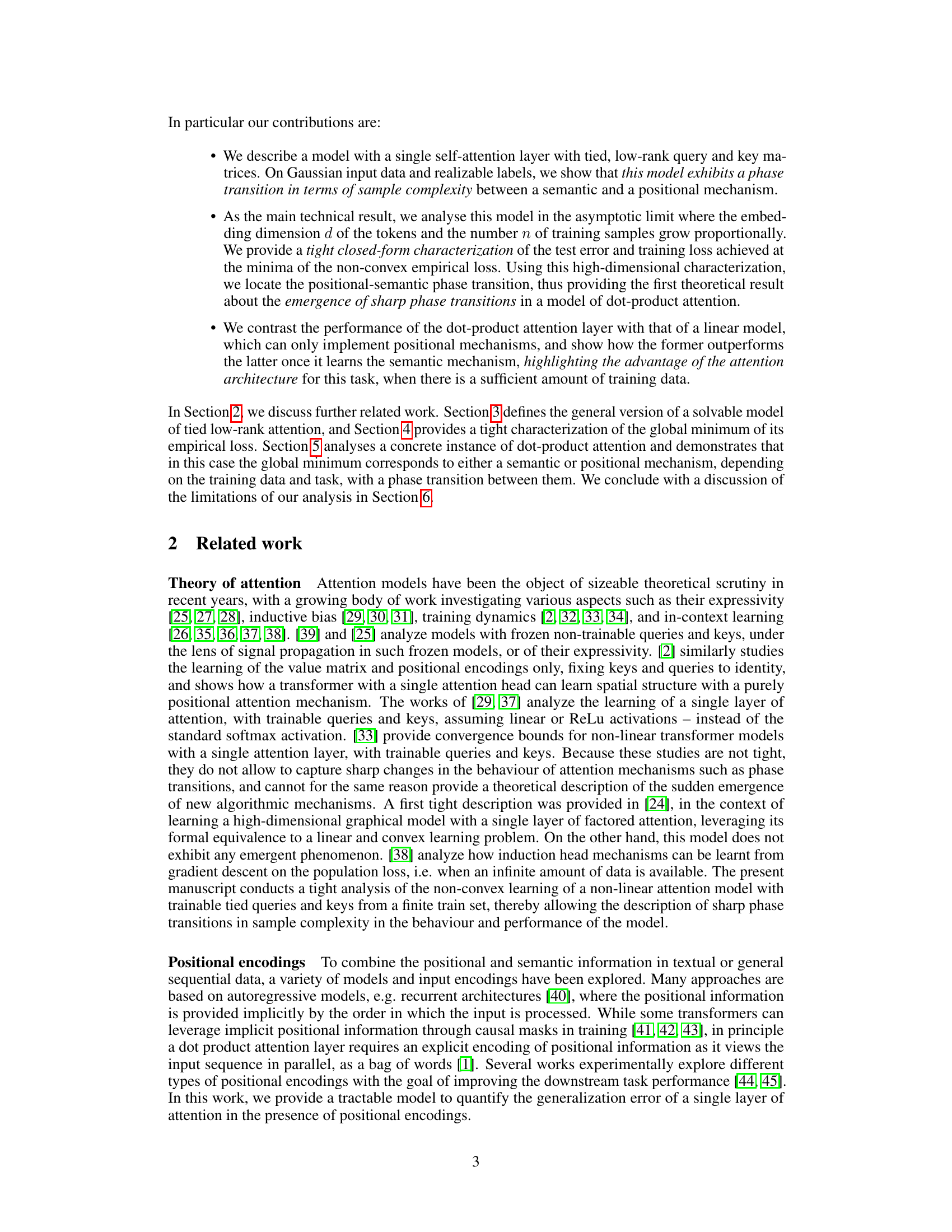

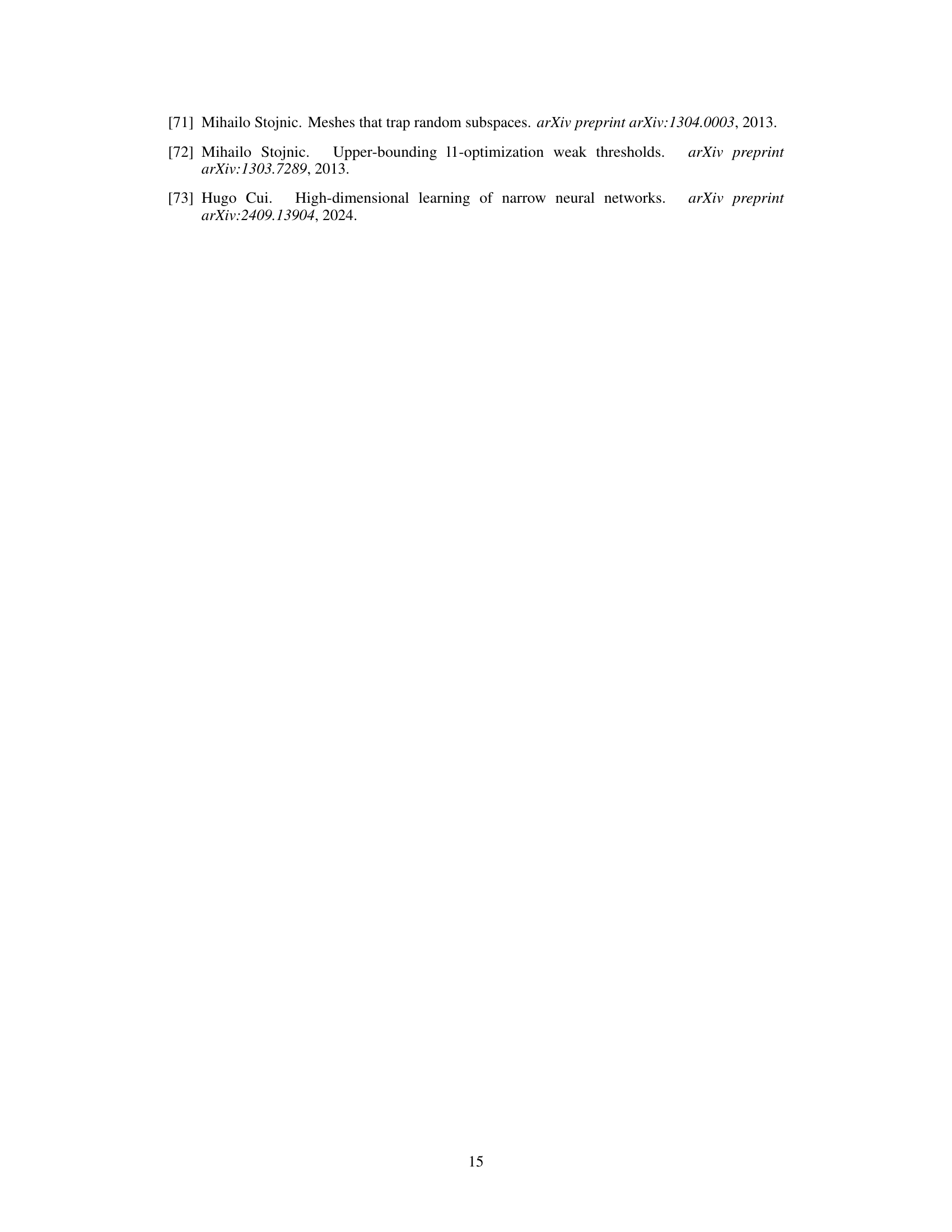

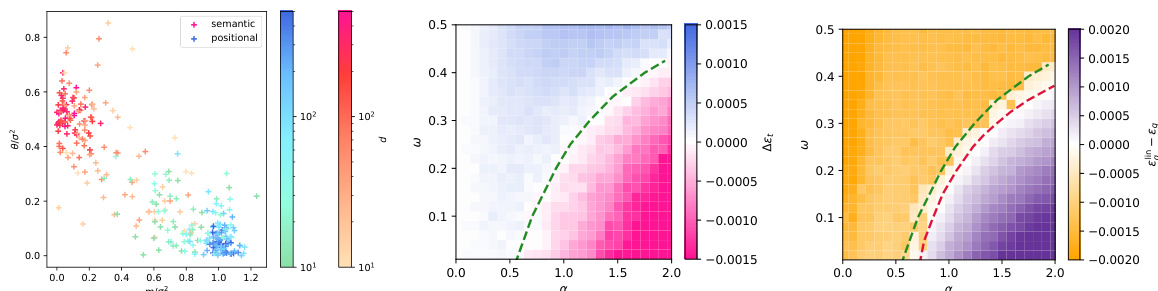

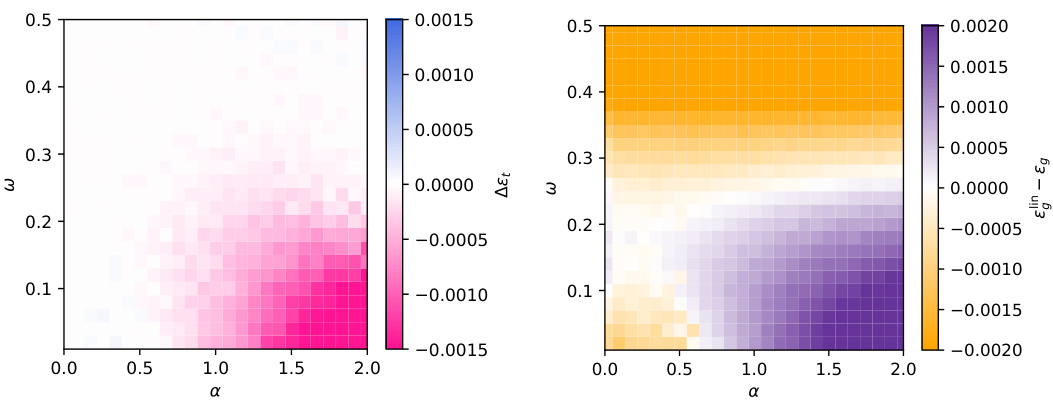

This figure shows the phase transition between semantic and positional mechanisms in a dot-product attention model. The left panel shows how scaling the embedding dimension and sample size affects the concentration of the summary statistics. The center and right panels depict color maps visualizing the difference in training loss and test error respectively between semantic and positional mechanisms, showing the sample complexity threshold where the semantic mechanism outperforms the positional mechanism.

This figure shows a phase transition between positional and semantic learning in a toy model of attention. The left panel shows the difference in training loss between semantic and positional solutions as a function of sample complexity. The center panel shows the overlap between learned weights and target/positional embeddings, comparing theoretical predictions with experimental results from gradient descent. The right panel compares the mean squared error (MSE) of the dot-product attention layer with a linear positional baseline.

This figure shows a phase transition between positional and semantic learning in a low-rank attention model. The left panel displays the difference in training loss between semantic and positional solutions as a function of sample complexity. The center panel shows the overlap between learned weights and target/positional embeddings, and the right panel compares the mean squared error (MSE) of the attention model to a linear baseline.

This figure shows a phase transition between positional and semantic learning in a toy model of attention. The plots show the difference in training loss between positional and semantic solutions as a function of sample complexity (α), overlap between learned weights and target weights, and test error comparison between the dot-product attention layer and a linear baseline. It demonstrates how increasing sample complexity leads to a transition from positional to semantic learning, where the dot-product attention outperforms the linear baseline when it learns the semantic mechanism.

This figure shows the phase transition between positional and semantic mechanisms in a dot-product attention model. The left panel shows the concentration of summary statistics in the high-dimensional limit. The center and right panels show color maps representing the difference in training loss and test MSE, respectively, between the positional and semantic solutions as a function of sample complexity (α) and teacher mix (ω). Dashed lines indicate theoretical predictions for phase transition thresholds.

This figure shows the phase transition between positional and semantic learning in a low-rank attention model. The left panel shows the difference in training loss between the semantic and positional solutions as a function of sample complexity. The center panel shows the overlap between the learned weights and the target weights (semantic overlap) and the learned weights and positional embeddings (positional overlap). The right panel compares the MSE of the low-rank attention model with a linear positional baseline, demonstrating that the semantic mechanism outperforms the positional baseline when sufficient data is available.

This figure shows the phase transition between semantic and positional learning mechanisms in a dot-product attention model. The left panel shows the concentration of summary statistics in the high-dimensional limit. The center and right panels display color maps representing the differences in training loss and test error between positional and semantic mechanisms, respectively, as functions of sample complexity (α) and the teacher’s mix parameter (ω). Dashed lines indicate the theoretical predictions for the phase transition thresholds.

This figure shows a phase transition between positional and semantic learning in a simplified self-attention model. Panel A depicts the model setup: a teacher uses both positional and semantic information, while the student only has access to positional information. Panel B illustrates the loss landscape, showcasing two minima corresponding to positional and semantic attention. Panel C demonstrates the phase transition where the global minimum shifts from positional to semantic attention as sample complexity increases. This transition is controlled by the teacher’s mixing of positional and semantic information.

This figure shows a phase transition between positional and semantic learning in a simplified attention model. Panel A describes the model setup, with a teacher model that uses both positional and semantic information and a student model that only uses positional information. Panel B illustrates the loss landscape of the teacher model which has two minima representing positional and semantic attention. Panel C shows that as the sample complexity (amount of data) increases, the global minimum of the student model transitions from a positional to a semantic solution. This highlights the emergence of semantic attention capabilities in the dot-product attention model given enough data.

This figure shows the phase transition between semantic and positional learning mechanisms in a dot-product attention model. The left panel shows the concentration of summary statistics for increasing embedding dimension and training samples. The central and right panels illustrate phase transitions in training loss and test error, respectively, comparing the dot-product attention model with a positional baseline. The phase transition marks the point where the semantic mechanism becomes superior to the positional one.

This figure shows a phase transition between semantic and positional mechanisms in a dot-product attention model. The left panel demonstrates the concentration of summary statistics (θ and m) for different embedding dimensions (d) and training samples (n) at a fixed ratio. The center panel displays the difference in training loss between semantic and positional solutions, highlighting the transition point (green dashed line). The right panel shows the difference in test MSE, indicating when the dot-product attention outperforms a linear baseline (red dashed line).

This figure shows the phase transition between semantic and positional mechanisms in a dot-product attention model. The left panel shows the concentration of summary statistics in the high-dimensional limit. The center and right panels show the difference in training loss and test error between semantic and positional mechanisms, highlighting a phase transition controlled by sample complexity.

This figure shows a phase transition between positional and semantic learning mechanisms in a dot-product attention model. The left panel demonstrates the concentration of summary statistics (θ and m) in different regions for semantic and positional minima as the embedding dimension and number of training samples scale proportionally. The center panel depicts a color map showing the training loss difference between semantic and positional minima, highlighting a transition point based on sample complexity. Finally, the right panel displays a similar color map for the test mean squared error (MSE), comparing the model’s performance to a linear positional baseline, revealing a threshold beyond which the attention model, using a semantic mechanism, outperforms the baseline.

Full paper#