↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) are powerful but computationally expensive. Existing methods for improving efficiency focus on post-training techniques exploiting naturally occurring activation sparsity. This limits their potential. This is a significant problem for researchers and developers seeking to deploy LLMs widely.

This paper introduces Learn-To-be-Efficient (LTE), a novel training algorithm that encourages LLMs to learn more structured sparsity during training. LTE achieves this by using an efficiency loss penalty and an adaptive routing strategy. Experiments demonstrate that LTE consistently outperforms state-of-the-art baselines in various language tasks. LTE also significantly reduces inference latency with a custom kernel implementation.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on large language model (LLM) efficiency because it introduces a novel training algorithm that significantly improves inference speed and sparsity without compromising performance. It addresses the critical issue of high computational costs associated with LLMs, which is a major obstacle to their wider adoption and practical use. The findings demonstrate a new avenue for optimizing LLMs for efficiency, and the publicly available code facilitates further research and development in this area. This work has high relevance to the current trend of making LLMs more efficient and accessible.

Visual Insights#

The figure illustrates the Learn-To-be-Efficient (LTE) method. The left side shows a standard Feed Forward Network (FFN) with its activations represented by orange squares. The activations are then passed through the LTE training process (represented by a circular diagram with interconnected nodes), which optimizes for structured sparsity. The right side shows the resulting FFN after LTE training; the activations are still represented by orange squares but are now more sparsely distributed, indicating improved efficiency. The overall process aims to reduce computational cost by activating fewer neurons during inference without significantly sacrificing performance.

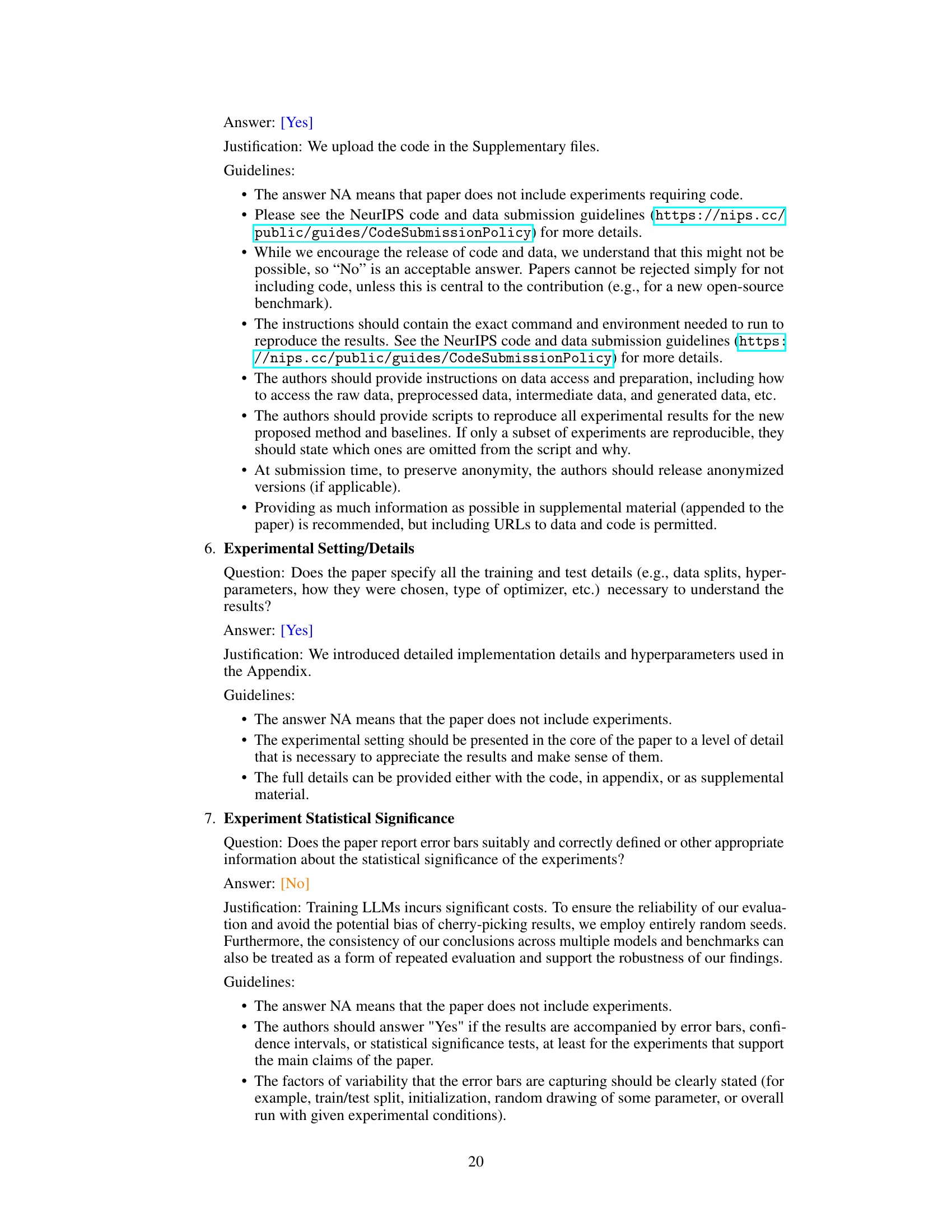

This table compares the GFLOPs per token for different methods (Full, Deja Vu, MoEfication, R-LLaMA+MoE, and LTE) on three NLG datasets (XSum, E2E, Wiki) using the LLaMA-7B model. The results show the computational efficiency gains achieved by each method, with LTE demonstrating significant improvements in reducing FLOPs while maintaining acceptable performance. Note that N/A indicates methods failed to reach expected performance levels.

In-depth insights#

Structured Sparsity#

Structured sparsity in large language models (LLMs) focuses on creating patterns in the sparsity of activated neurons during inference, as opposed to random sparsity. This is crucial because structured sparsity allows for more efficient hardware implementations. Algorithms like Learn-To-Be-Efficient (LTE) aim to train models to achieve this structured sparsity, resulting in significant improvements in inference speed without a substantial decrease in accuracy. While existing techniques focus on post-training manipulation of naturally occurring sparsity, LTE directly incorporates sparsity into the training process itself, learning to activate fewer neurons in a more organized manner. This approach is particularly valuable for LLMs using non-ReLU activation functions, where inherent sparsity may be lower than in ReLU-based models. Achieving high sparsity levels (e.g., 80-90%) with minimal performance degradation is a significant achievement, demonstrating the effectiveness of this approach in making LLMs more efficient and resource-friendly.

LTE Training#

The LTE training process is a two-stage approach designed for improved stability and efficiency. Stage 1, model-router training, uses a soft selection mechanism with a sigmoid routing function and an efficiency loss to encourage the selection of fewer, more important experts. The soft selection avoids the non-differentiability issues of hard thresholding and avoids biased expert score allocation inherent in softmax routing. This is coupled with a separability loss to improve the distinctness of expert scores. In Stage 2, model adaptation, the router is frozen, switching to a hard selection threshold, and the model parameters are further fine-tuned to adapt to the changed expert selection process. This two-stage training approach addresses the challenges of training routers stably within a MoE setting, allowing for flexible expert selection in service based on input and layer, ultimately improving model sparsity without significant accuracy loss.

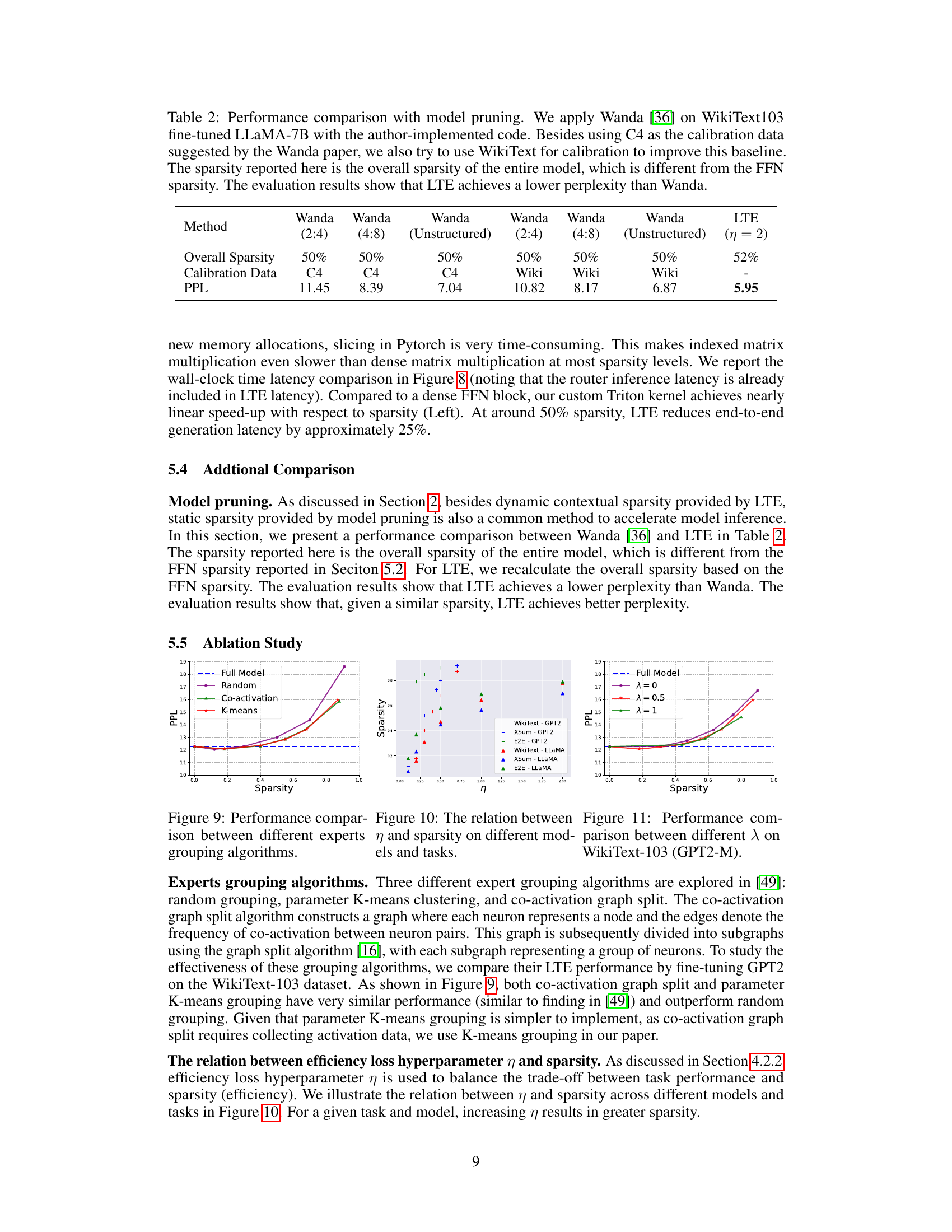

Hardware Speedup#

The research paper explores hardware acceleration techniques to improve the inference speed of large language models (LLMs). A key finding is that achieving structured sparsity during training is crucial for efficient hardware implementation. The authors propose a novel training algorithm, Learn-To-Be-Efficient (LTE), to encourage the model to develop this structured sparsity. LTE’s effectiveness is demonstrated through a custom CUDA kernel implementation, which leverages the structured sparsity to reduce memory access and computation, resulting in significant latency reductions. The hardware-aware optimizations are shown to deliver a substantial speedup, achieving a 25% reduction in LLaMA2-7B inference latency at 50% sparsity. This highlights the potential of carefully designed training algorithms in conjunction with optimized hardware kernels to bridge the gap between the theoretical efficiency gains of sparsity and tangible performance improvements in real-world LLM deployments.

Ablation Studies#

Ablation studies systematically remove components of a model or system to assess their individual contributions. In this context, they’d likely investigate the impact of each component of the proposed training algorithm. Key areas for ablation would include: the efficiency loss penalty (evaluating its contribution to sparsity and performance), the threshold-based sigmoid routing (comparing its stability and accuracy against other routing mechanisms like softmax), and the two-stage training strategy (determining if the separate stages are crucial). Results would show how each component affects the overall model’s performance, such as accuracy or latency reduction. The analysis should highlight the trade-offs between different components, illustrating whether some elements are more critical than others or exhibit synergistic effects when combined. Ultimately, ablation studies strengthen the paper’s claims by providing granular insights into the algorithm’s functionality and identifying the core elements essential for its success.

Future Work#

The paper’s core contribution is the LTE algorithm, showing promise in enhancing LLM efficiency. Future work should prioritize expanding LTE’s applicability beyond the tested models and datasets. A thorough investigation into the algorithm’s performance across diverse LLM architectures and various task types is crucial. Addressing the trade-off between sparsity and model accuracy at higher sparsity levels is key. Research into more robust routing strategies and the development of more efficient hardware implementations could further improve inference speed. Finally, exploring the integration of LTE with other efficiency-enhancing techniques, such as model quantization or pruning, could yield significant performance gains. Investigating the application of LTE to instruction tuning and few-shot learning scenarios requires further attention, as this could open doors to wider adoption and enhanced LLM generalisation abilities. Addressing the limitations of increased training complexity and the potential for biased expert selection also represents valuable future research directions.

More visual insights#

More on figures

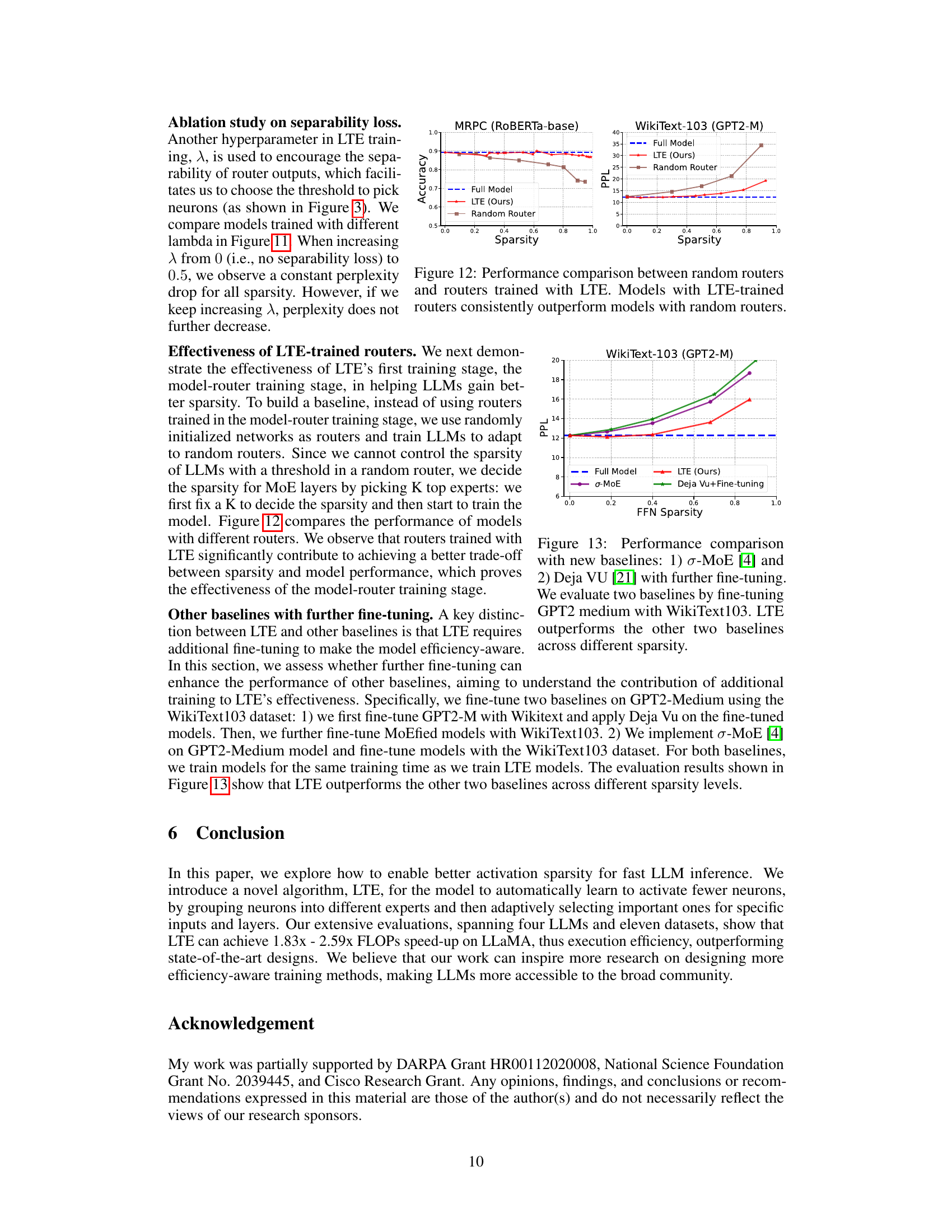

This figure shows the accuracy drop of two models, MRPC (ROBERTa-base) and QNLI (ROBERTa-base), when using noisy top-K Softmax routing at different sparsity levels. The accuracy of both models significantly decreases as sparsity increases, even at very low sparsity levels. This demonstrates a limitation of the noisy top-K Softmax routing method for achieving sparsity in language models.

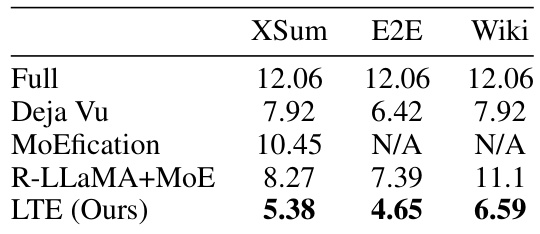

This figure compares the distribution of expert scores in two models: one trained without the separability loss and another trained with it. The separability loss is a component of the LTE training algorithm, designed to improve the selection of experts by making their scores more distinct. The graph clearly shows that adding the separability loss leads to a more clearly separated distribution of expert scores, making it easier to choose experts based on a simple threshold.

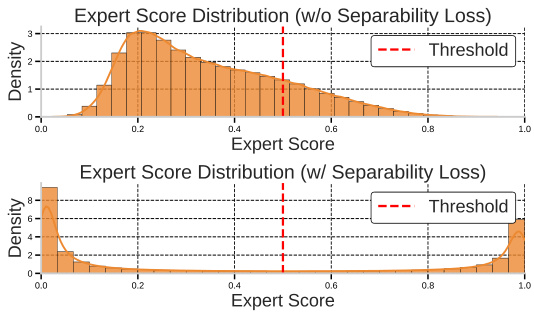

This figure illustrates how LTE achieves structured sparsity in the feed-forward neural network (FFN) layers of a transformer. The left side shows the input vector x multiplied by the weight matrix Wup. LTE selects a subset of neurons (shown in orange), creating a sparse representation. The matrix multiplication is then performed only on the selected neurons, which drastically reduces the computational load. The result of this sparse multiplication is then multiplied by the weight matrix Wdown, again with the same sparsity pattern, producing a final output vector xout. This structured sparsity is key to LTE’s efficiency gains.

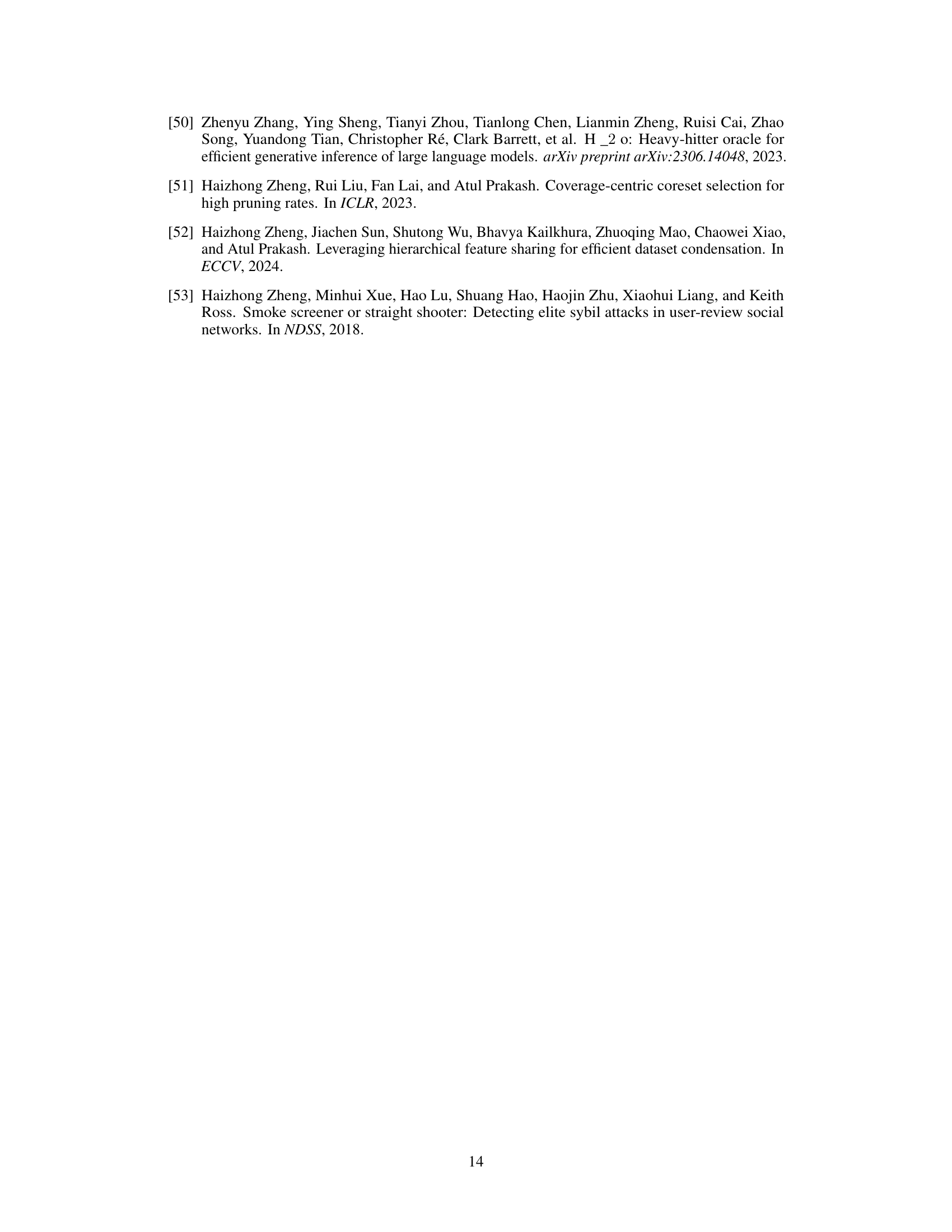

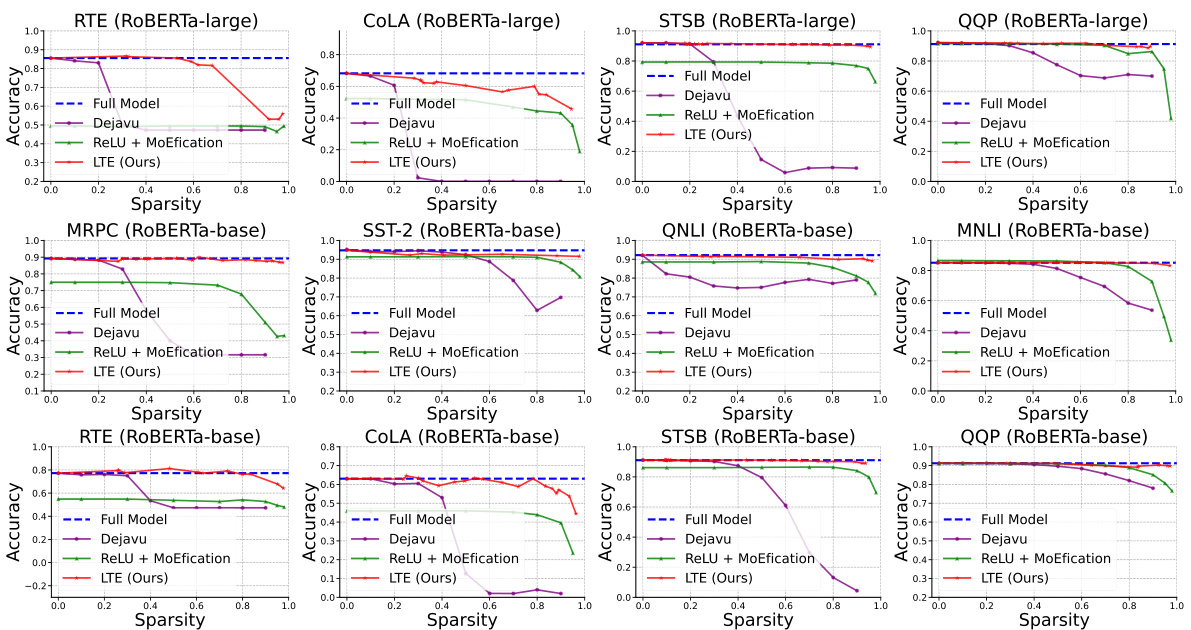

This figure displays the performance of LTE and baseline models on four different natural language understanding (NLU) tasks from the GLUE benchmark. The x-axis represents sparsity levels, ranging from 0 to 1 (100%). The y-axis shows accuracy. LTE consistently achieves higher accuracy than the other methods (Deja Vu, ReLU + MoEfication) at various sparsity levels, demonstrating its effectiveness in maintaining good performance even with high sparsity.

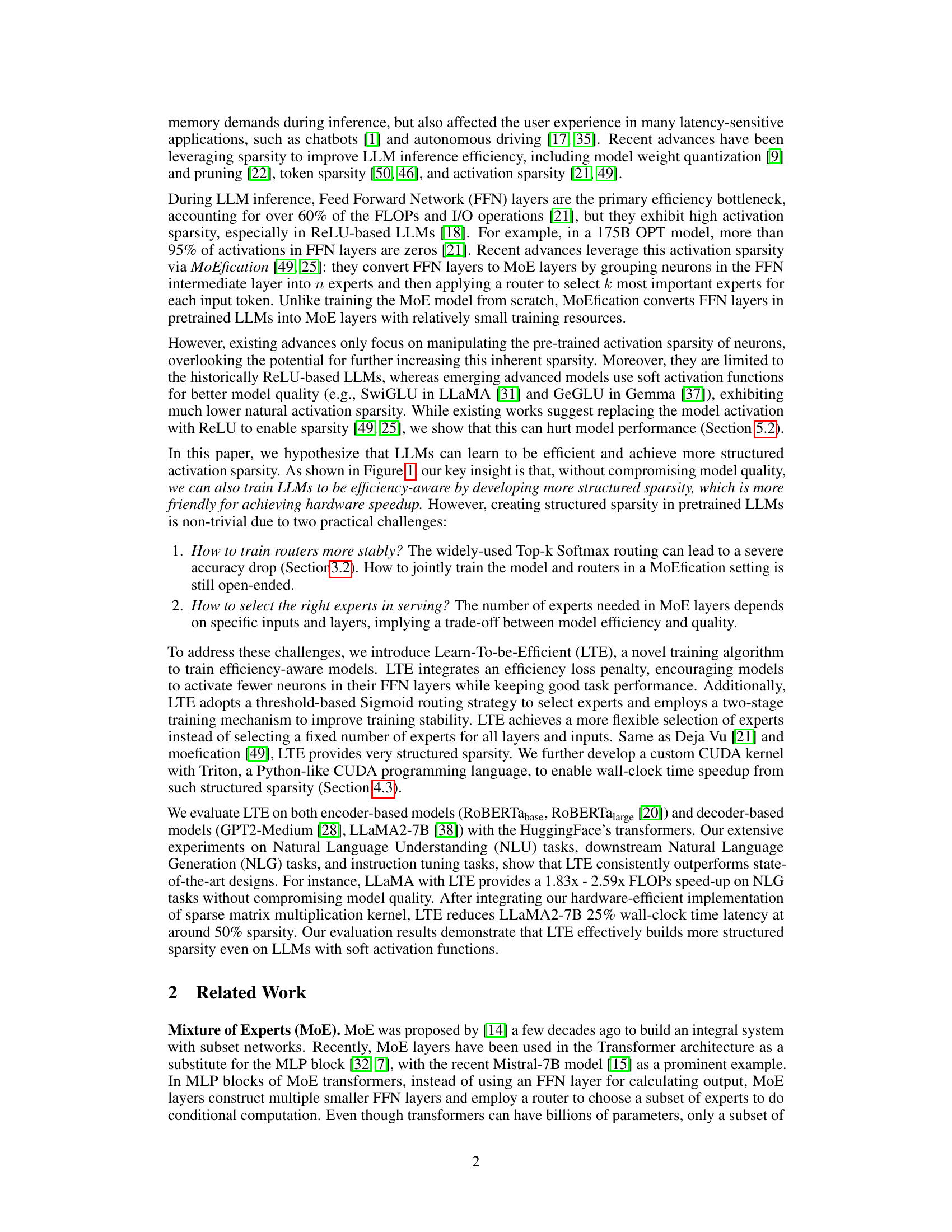

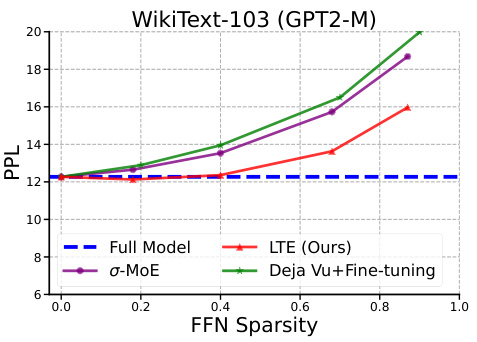

This figure compares the performance of LTE against other baselines (Full Model, Deja Vu, MoEfication, and R-LLaMA+MoEfication) across three different NLG (Natural Language Generation) datasets (XSum, E2E, and WikiText-103). The comparison is shown for two different decoder-based models: GPT2-Medium and LLaMA-7B. Each subfigure shows the performance metric (ROUGE-L for XSum and E2E, Perplexity for WikiText-103) plotted against sparsity levels. This visualization helps to understand how the different methods perform at various levels of sparsity and which model is more resilient to sparsity.

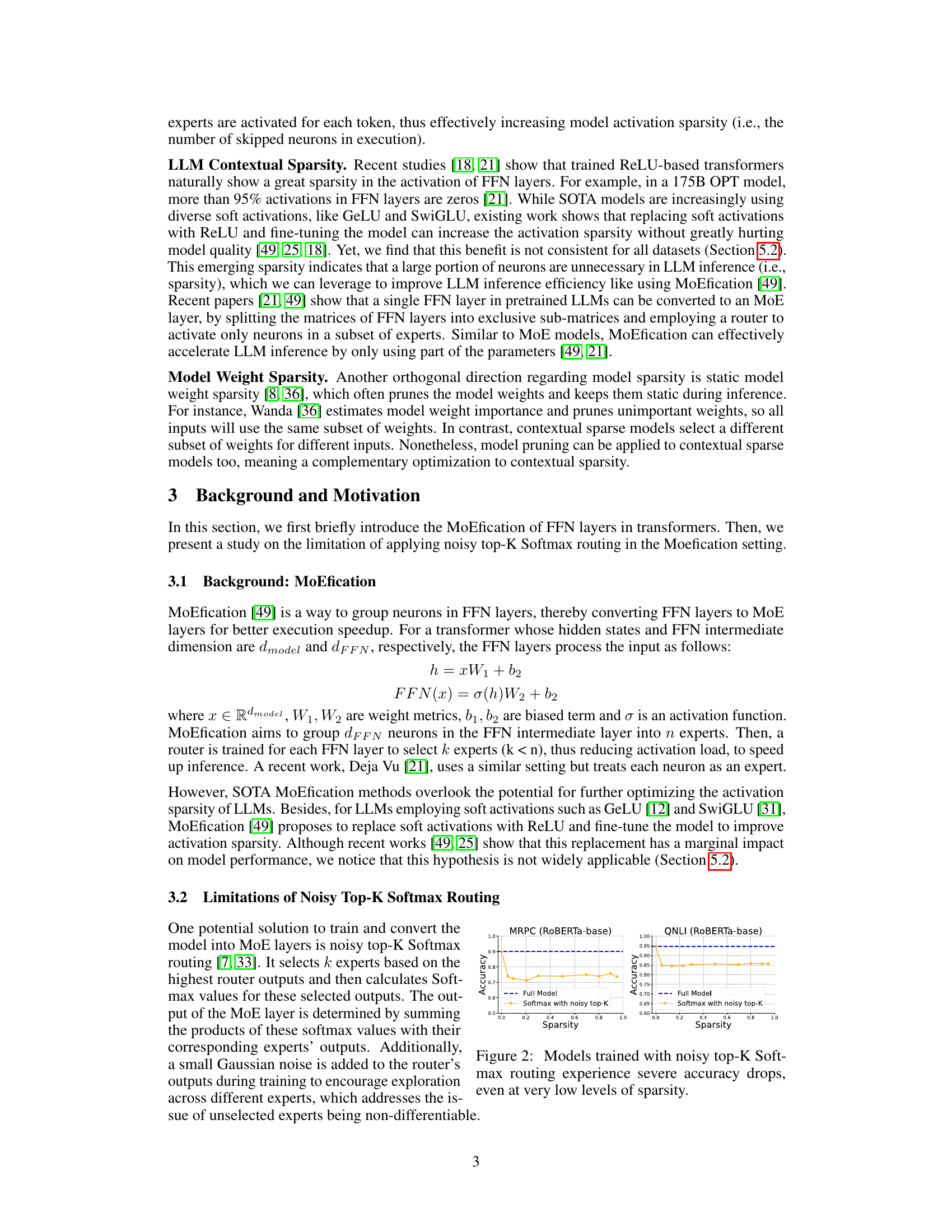

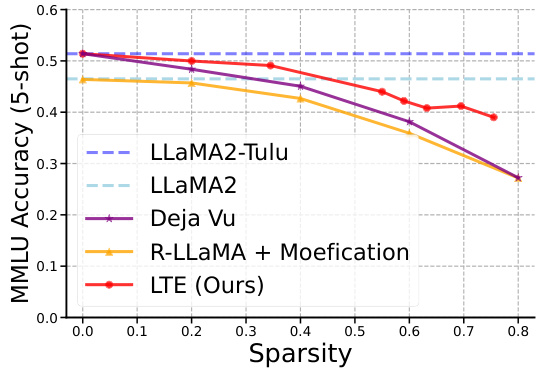

This figure shows the performance comparison of LTE with other baselines on a 5-shot MMLU benchmark. The x-axis represents the sparsity, and the y-axis represents the MMLU accuracy (5-shot). The results demonstrate that LTE consistently achieves higher accuracy than other methods across different sparsity levels. This highlights LTE’s effectiveness in improving model performance without significantly impacting efficiency.

The figure shows two subfigures. The left one presents a line graph comparing the FFN inference latency of a dense model and a model with LTE using a custom Triton kernel and PyTorch indexing across different sparsity levels. The right one displays a bar chart comparing the end-to-end generation latency of the dense model and the LTE model (at 50% sparsity) for various sequence lengths.

The figure shows a comparison of the performance of different expert grouping algorithms used in the Learn-To-be-Efficient (LTE) model. The algorithms compared are random grouping, co-activation graph split, and K-means clustering. The performance metric is perplexity on the WikiText-103 dataset, and the x-axis represents the sparsity of the model. The results indicate that co-activation graph split and K-means clustering achieve similar and better performance compared to random grouping.

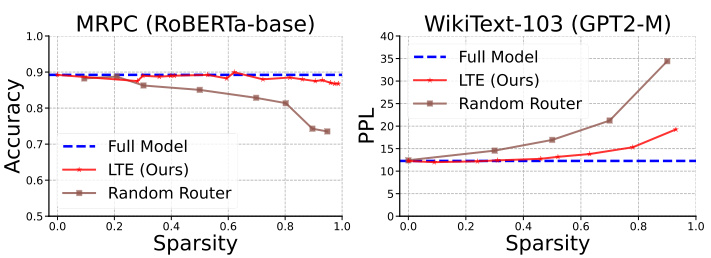

This figure compares the performance of models using randomly initialized routers versus routers trained with the Learn-To-be-Efficient (LTE) algorithm. The left panel shows accuracy on the MRPC dataset using a RoBERTa-base model, while the right panel displays perplexity on the WikiText-103 dataset using a GPT2-Medium model. Both panels demonstrate that models with LTE-trained routers consistently achieve better results across various sparsity levels, highlighting the effectiveness of LTE in training stable and efficient routers.

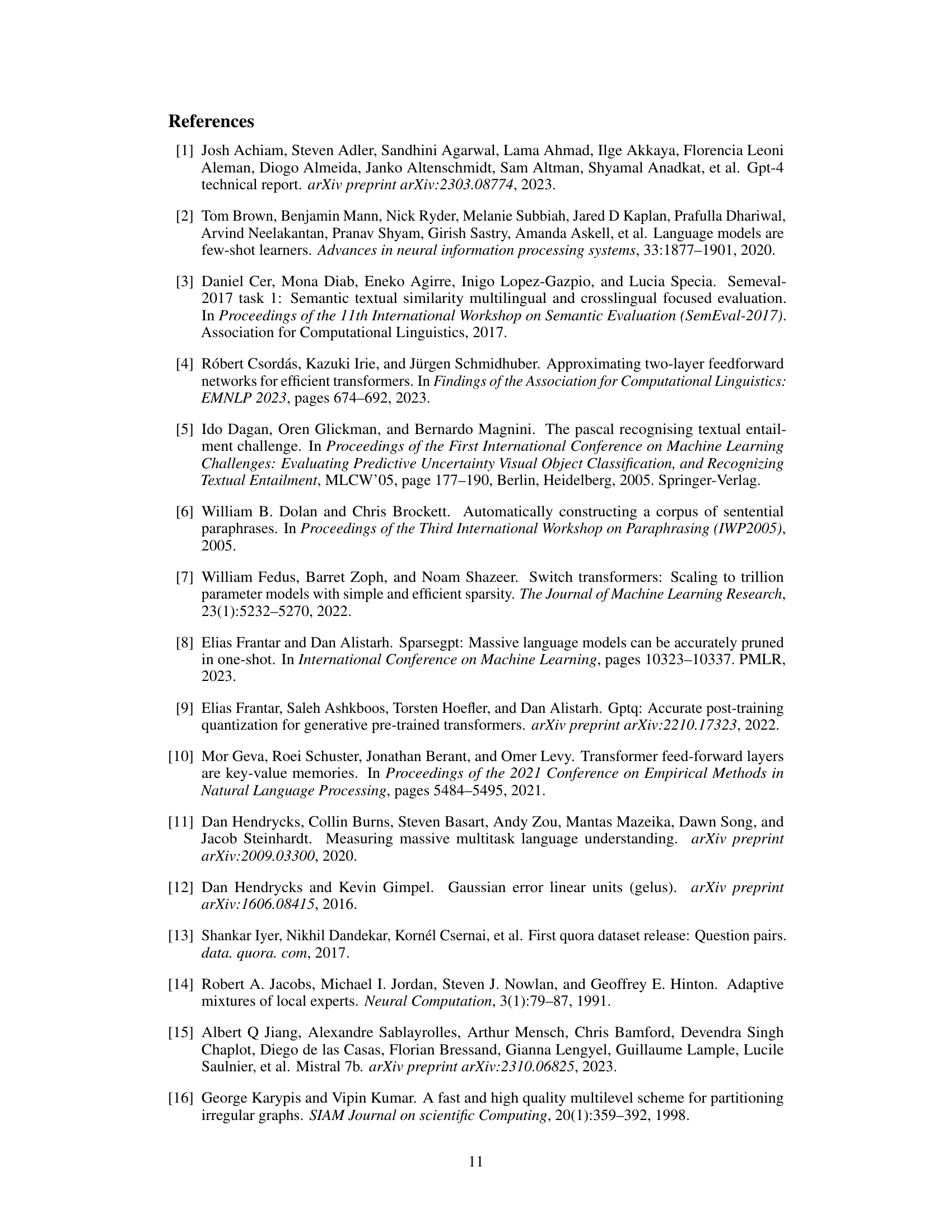

This figure compares the performance of LTE with other baselines on three different NLG (Natural Language Generation) tasks using two different decoder-based language models, GPT2-Medium and LLaMA-7B. Each column represents a different NLG task (XSum, E2E, and WikiText-103), while each row shows the results for a different language model. The x-axis shows the FFN (Feed-Forward Network) sparsity, and the y-axis shows the performance metrics (ROUGE-L for XSum and E2E, and perplexity for WikiText-103). The figure visually demonstrates the performance of LTE across various sparsity levels compared to other methods (Full Model, Deja Vu, MoEfication, and R-LLaMA+MoEfication).

This figure shows the performance comparison of LTE against other baselines (Deja Vu and ReLU + MoEfication) on four different Natural Language Understanding (NLU) datasets from the GLUE benchmark. The x-axis represents the sparsity level, and the y-axis represents the accuracy. The results demonstrate that LTE consistently achieves higher accuracy than the baselines across various sparsity levels, indicating its effectiveness in improving model efficiency without significant performance loss.

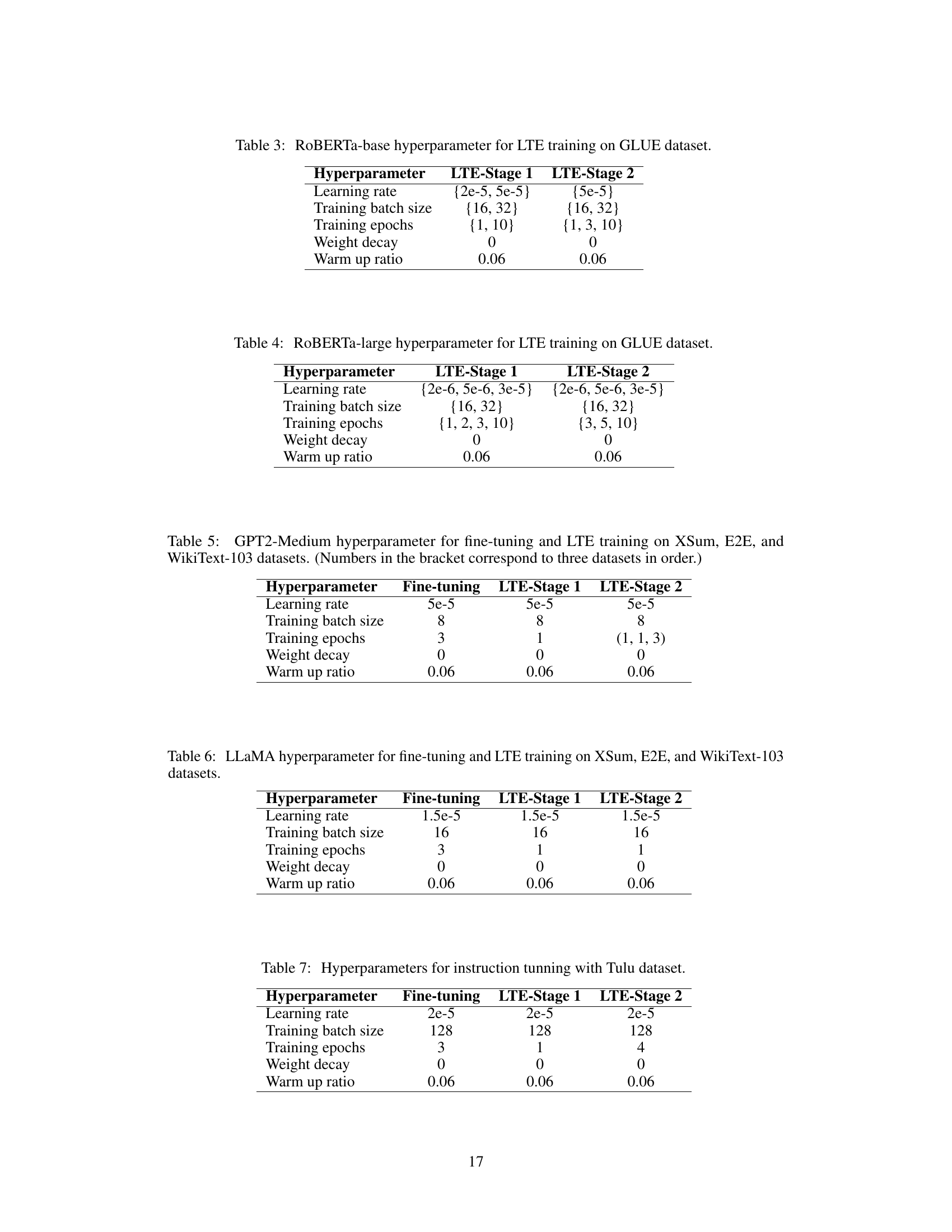

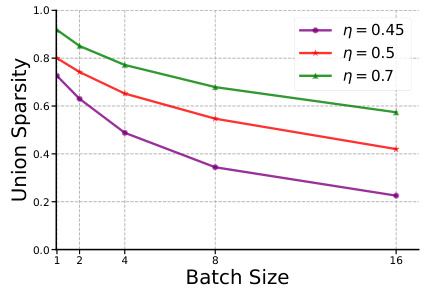

This figure shows how union sparsity changes with respect to batch size for different values of efficiency loss (η). Union sparsity represents the proportion of unique neurons activated across multiple input batches. As the batch size increases, more neurons tend to be activated, leading to a decrease in union sparsity. The figure demonstrates that the increase in activated neurons is not linear with the batch size. This suggests a non-uniform distribution of parameter access across different inputs. The non-linear relationship implies that even with larger batch sizes, significant sparsity can still be achieved. This observation is relevant for the application of LTE in high-throughput scenarios, where batching inputs activating similar neurons might help achieve a high union sparsity.

This figure shows the distribution of sparsity across different layers in two different models: RoBERTa-base (for MRPC task) and GPT2-M (for WikiText-103 task). It highlights that LTE doesn’t apply a uniform sparsity level across all layers but rather adapts it depending on the layer’s importance for the task. The pattern of sparsity distribution also differs between the two model architectures, reflecting their distinct designs and how information is processed through the layers.

More on tables

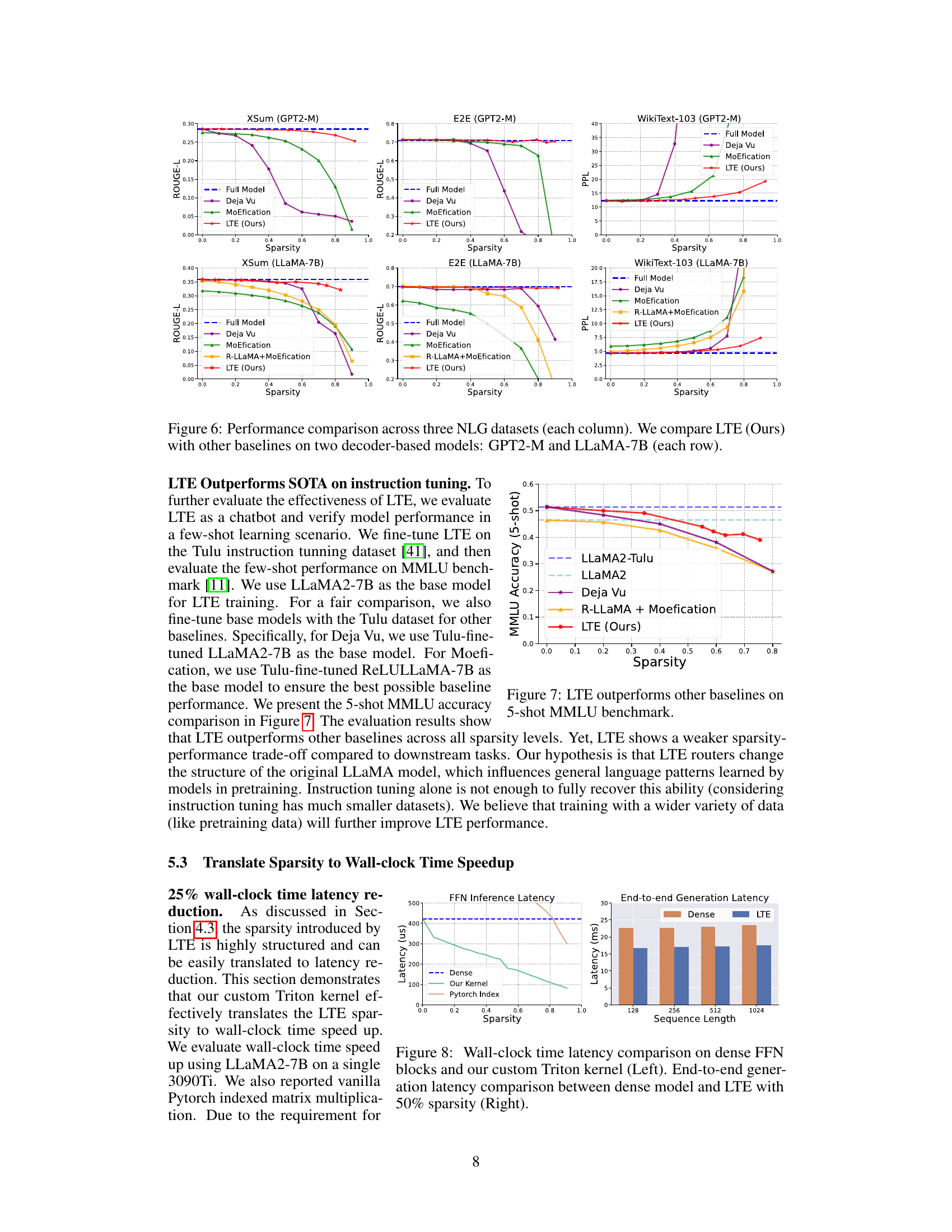

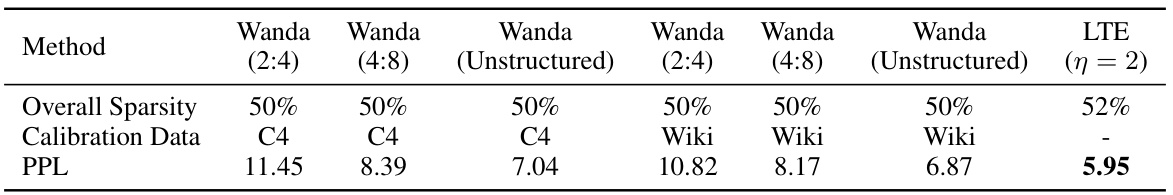

This table compares the performance of LTE and Wanda model pruning methods on the WikiText103 dataset. It shows perplexity (PPL) results for both methods at varying sparsity levels (50% and 52%). Different calibration data (C4 and WikiText) were used for Wanda, showing its impact on performance. LTE consistently demonstrates lower perplexity than Wanda. It highlights the difference between overall model sparsity and FFN layer sparsity.

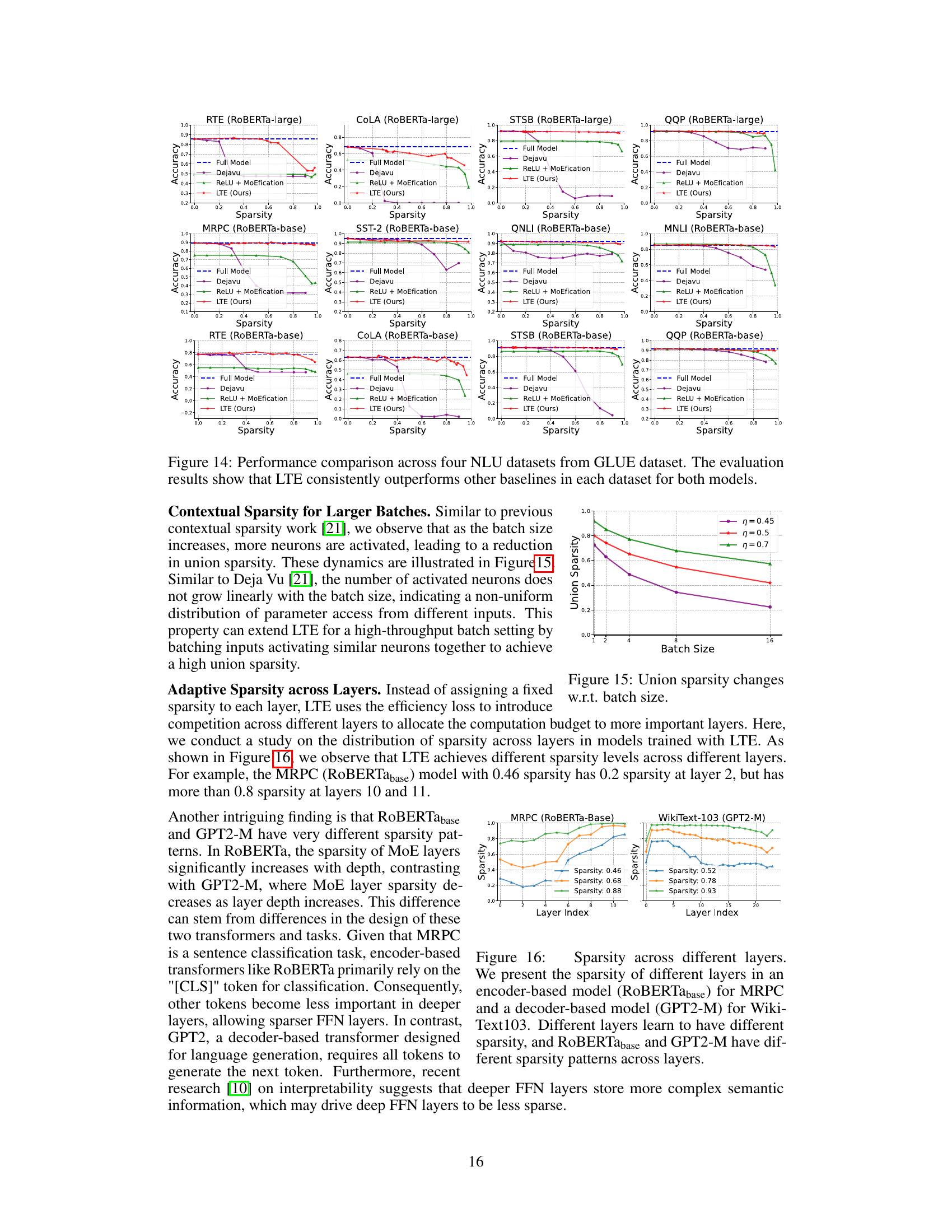

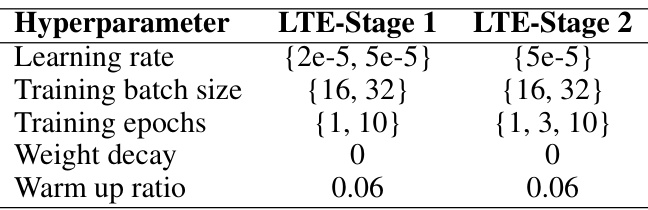

This table shows the hyperparameters used for training the ROBERTa-base model using the Learn-To-be-Efficient (LTE) algorithm on the GLUE benchmark dataset. It lists the learning rate, training batch size, training epochs, weight decay, and warm-up ratio for both stages of the LTE training process (LTE-Stage 1 and LTE-Stage 2). The values provided are either single values or a range of values indicating that multiple experiments were run with different settings to find the optimal hyperparameters.

This table shows the hyperparameters used for training the large version of RoBERTa model using the Learn-To-be-Efficient (LTE) algorithm on the GLUE benchmark dataset. It specifies the hyperparameters for both stages of the LTE training process: Stage 1 (model-router training) and Stage 2 (model adaptation). For each stage, hyperparameters such as the learning rate, training batch size, training epochs, weight decay, and warm-up ratio are listed. Braces {} indicate a range of values tested; the best performing value was selected.

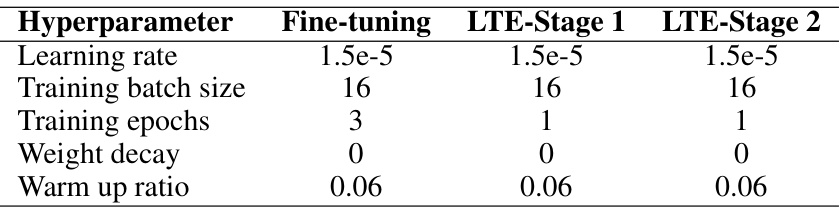

This table shows the hyperparameters used for fine-tuning and training with LTE for the GPT2-Medium model on three different datasets: XSum, E2E, and WikiText-103. It details the learning rate, training batch size, number of training epochs, weight decay, and warm-up ratio for each stage of the training process (fine-tuning, LTE Stage 1, and LTE Stage 2). Note that the number of training epochs varies depending on the dataset, reflecting the different training requirements of each dataset.

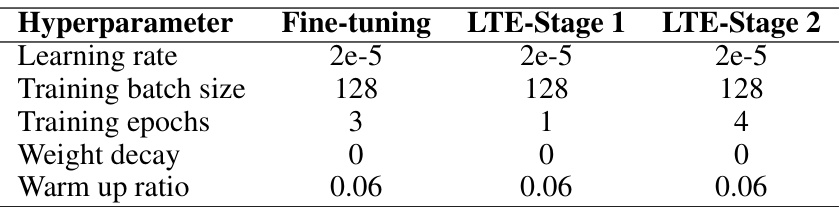

This table shows the hyperparameters used for fine-tuning and LTE training (both stage 1 and stage 2) on three different datasets: XSum, E2E, and WikiText-103. The hyperparameters include learning rate, training batch size, training epochs, weight decay, and warm-up ratio. Note that the values in parentheses correspond to the three datasets in order.

This table presents the hyperparameters used for fine-tuning and two-stage LTE training on the Tulu instruction tuning dataset. It shows the learning rate, training batch size, training epochs, weight decay, and warm-up ratio used in each stage of the training process. The fine-tuning stage prepares the base model, followed by LTE-Stage 1 (model-router training) and LTE-Stage 2 (model adaptation).

Full paper#