↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many machine learning tasks benefit from using simpler, feature-restricted models because they are computationally cheaper and easier to train with limited data. However, these restricted models often cannot capture the complexity of the target task. This paper introduces Induced Model Matching (IMM), a novel method that leverages the knowledge from a highly accurate restricted model to improve the training of a more powerful, full-featured model. Existing methods like noising and reverse knowledge distillation are shown to be approximations to IMM, suffering from consistency issues.

IMM addresses the limitation of prior methods by aligning the induced (restricted) version of the full-featured model with the restricted model. The paper shows that IMM consistently outperforms these prior approaches on various tasks including logistic regression, language modeling (LSTMs and Transformers), and reinforcement learning. These results highlight the general applicability of IMM and its potential to improve model training in scenarios where restricted data or models are easily available.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel and generally applicable methodology, Induced Model Matching (IMM), for leveraging readily available restricted models to improve the training of full-featured models. This addresses a common challenge across many machine learning applications where restricted data is easier to acquire than full data. IMM offers significant advantages over existing methods such as noising and reverse knowledge distillation, providing improved consistency and efficiency. The demonstrated improvements in various domains, including language modeling and reinforcement learning, suggest wide applicability and open avenues for future research on model training strategies and knowledge transfer.

Visual Insights#

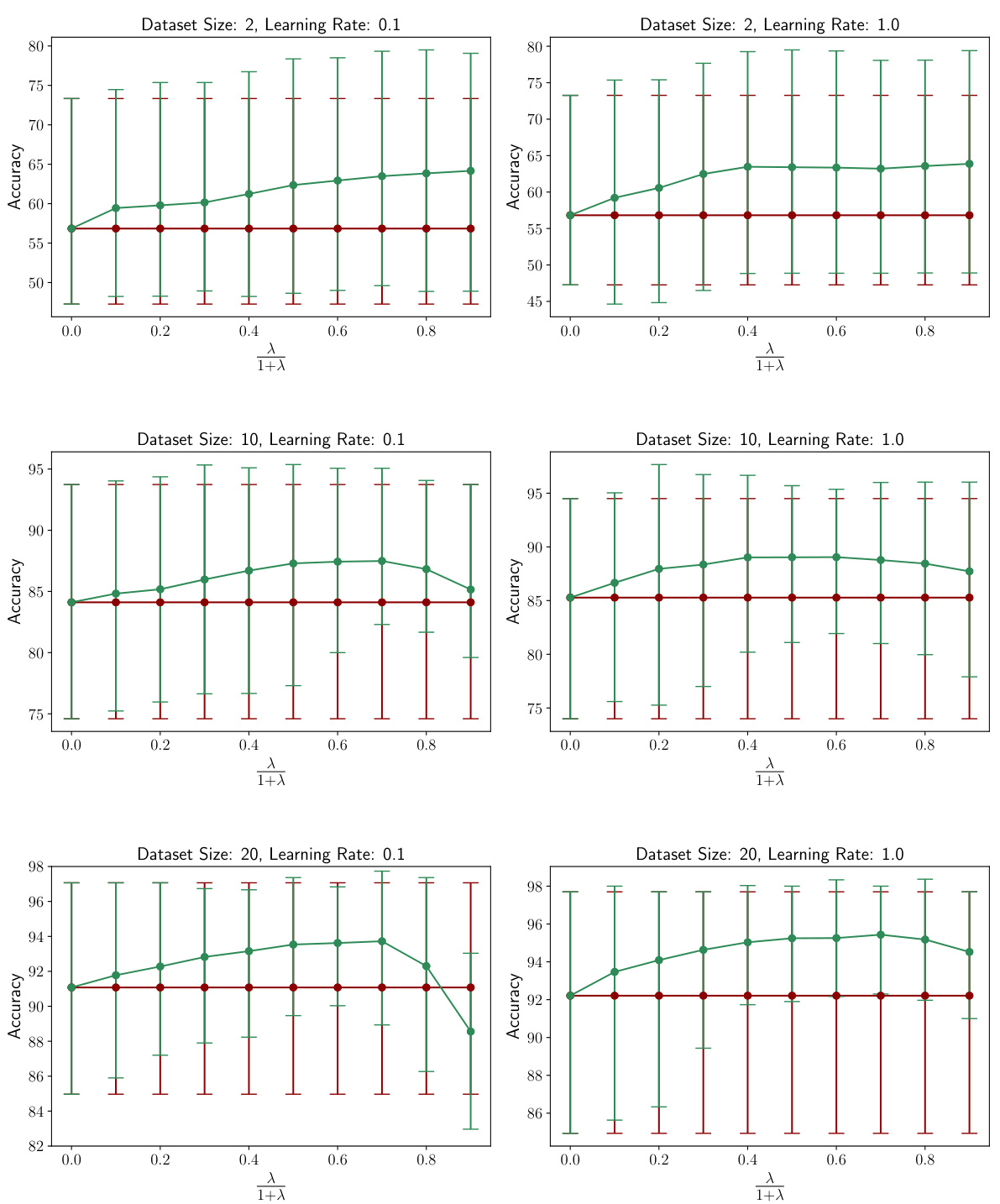

This figure shows the test accuracy results for a logistic regression model trained with and without Induced Model Matching (IMM). The x-axis represents the size of the dataset used for training, and the y-axis represents the test accuracy. Multiple runs (300) were conducted, and the bars in the graph represent the 10th to 90th percentiles of the accuracy across these runs, indicating the variance in performance. The graph compares four different training methods: IMM with a target model, noising with a target model, interpolation with a target model, and a baseline method with no IMM, noising, or interpolation. The results show that IMM consistently improves test accuracy compared to the other methods, especially with smaller datasets, suggesting its effectiveness in leveraging information from a restricted model to enhance full-featured model training.

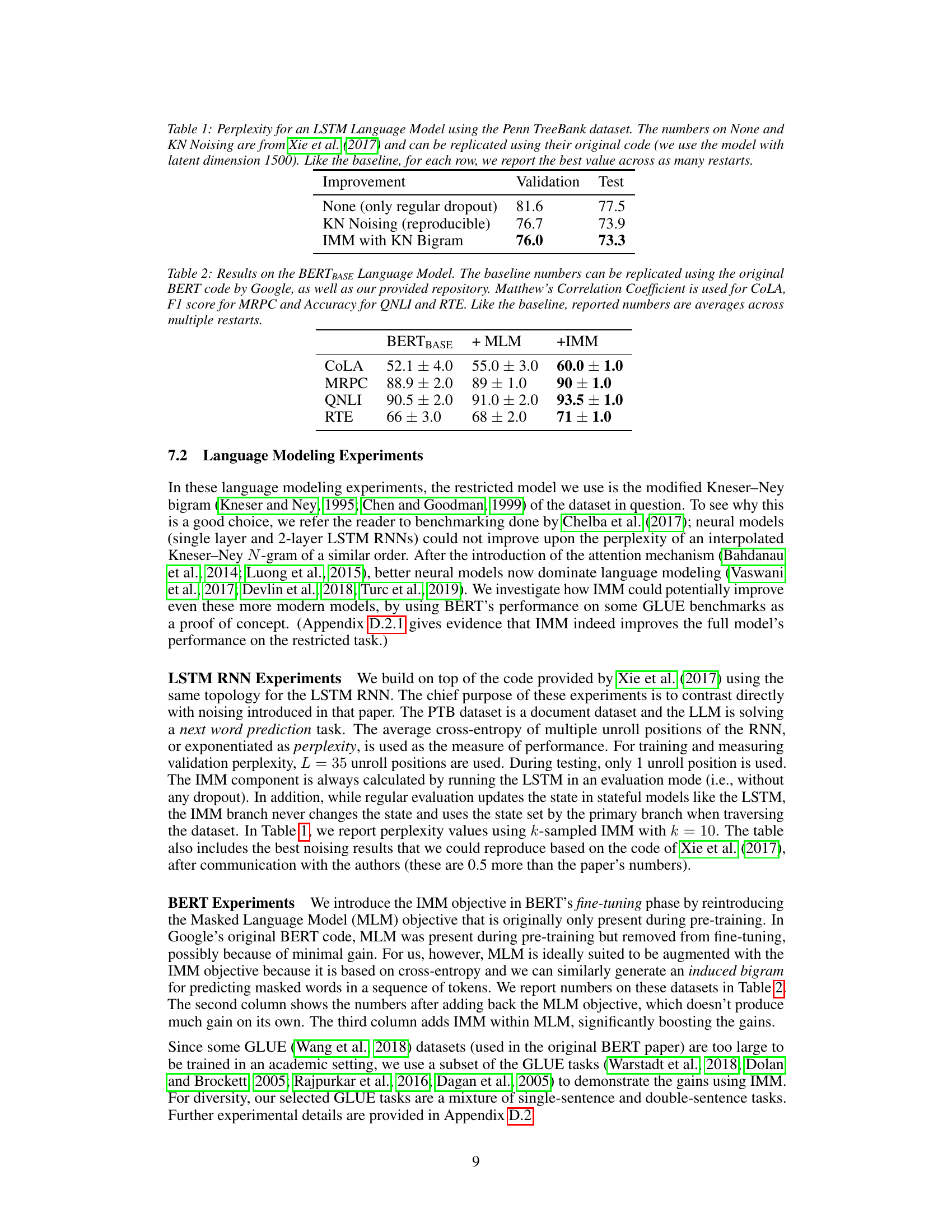

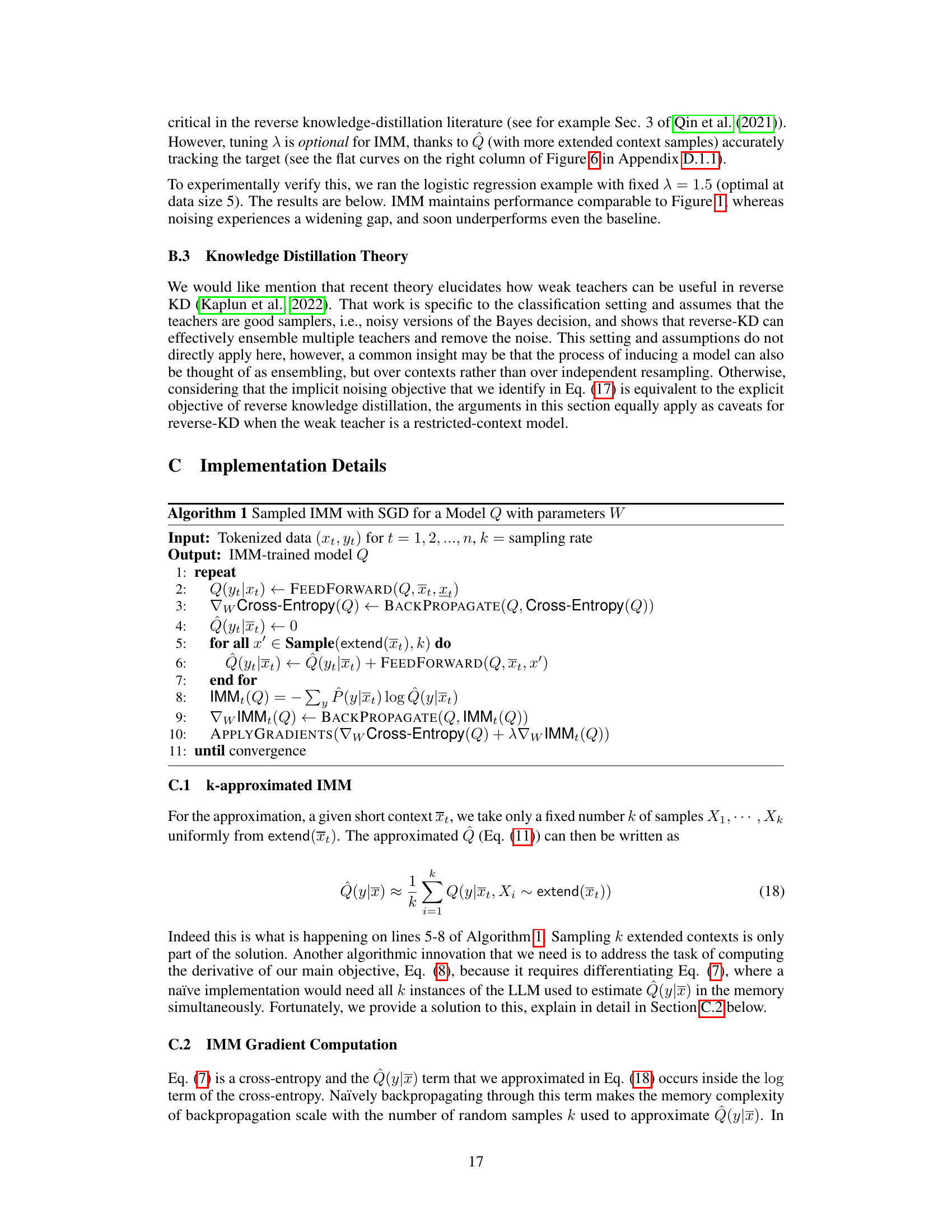

This table shows the perplexity results for an LSTM language model trained on the Penn TreeBank dataset using three different methods: None (only regular dropout), KN Noising (reproducible), and IMM with KN Bigram. The perplexity is reported for both validation and test sets. The results for None and KN Noising are taken from Xie et al. (2017) and are shown here for comparison. IMM, or Induced Model Matching, is a novel method introduced in the current paper.

In-depth insights#

IMM: Core Idea#

The core idea behind Induced Model Matching (IMM) is to leverage the knowledge of a highly accurate, feature-restricted model to improve the training of a more complex, full-featured model. IMM doesn’t simply add the restricted model as a regularizer; instead, it cleverly creates an induced version of the full model, restricted to the same features as the smaller model. This induced model is then aligned with the smaller model using a secondary loss function. This crucial step ensures consistency and addresses the limitations of previous methods like noising and reverse knowledge distillation which can suffer from inconsistencies, particularly with weak teachers. The benefit is a more efficient training process, achieving performance gains comparable to significantly increasing the dataset size. The strength of IMM lies in its generality: applicable in various scenarios where restricted data is easier to obtain or restricted models are simpler to learn, including language modeling, logistic regression, and reinforcement learning.

IMM: Experiments#

The IMM experimental section likely details empirical evaluations across diverse machine learning domains, demonstrating the effectiveness of Induced Model Matching (IMM). Key experiments probably include comparisons against traditional methods like noising or reverse knowledge distillation, showcasing IMM’s superior performance in improving full-featured models. The experiments would focus on evaluating metrics like accuracy, perplexity, or reward depending on the specific machine learning task. Toy examples, such as logistic regression, would likely serve as initial validations before applying IMM to more complex scenarios such as language modeling with recurrent neural networks (RNNs) or transformers, and reinforcement learning. The results would meticulously analyze the impact of hyperparameters, dataset size, and the quality of the restricted model on IMM’s performance, providing quantitative evidence supporting IMM’s benefits in a variety of contexts. Careful attention would be paid to illustrating IMM’s efficiency in handling scenarios where restricted data is abundant and full-featured data is scarce.

Noising vs. IMM#

The core of the paper revolves around a novel methodology called Induced Model Matching (IMM), which is presented as a superior alternative to existing data augmentation techniques like noising. IMM leverages a pre-trained restricted model to guide the training of a full-featured model, effectively using the restricted model’s knowledge to improve performance and reduce variance. While noising attempts to inject information from a restricted model through perturbation, it’s shown to be a suboptimal approximation of IMM and may not be consistent even with infinite data. IMM, conversely, offers consistency and direct optimization, leading to significantly better results in experimental settings involving language modeling and logistic regression. The comparison highlights IMM’s refined approach to knowledge transfer, moving beyond the noisy injection of noising toward a principled matching of model predictions at equivalent restricted levels. This allows for greater efficiency and more robust learning, particularly beneficial when data is scarce or computationally expensive.

IMM: Limitations#

Induced Model Matching (IMM), while promising, faces limitations. Computational cost is a major hurdle, especially for large models and extensive datasets. Direct implementation requires a secondary pass, increasing training time significantly. While sampling techniques (Sampled IMM) mitigate this, they introduce approximation errors and variance in gradients. Data dependency is another concern; the accuracy of IMM hinges on the quality of the restricted model. A poor restricted model undermines the improvements IMM offers, highlighting the necessity of a high-quality, accurate restricted model. Theoretical limitations also exist, as IMM’s effectiveness is sensitive to parameter tuning (λ). Inadequate tuning could hinder its performance. Furthermore, while IMM demonstrates consistency theoretically, finite-sample behavior requires further investigation. Finally, the general applicability of IMM across diverse machine learning tasks remains to be fully explored, with current research focusing primarily on language modeling and reinforcement learning.

Future of IMM#

The future of Induced Model Matching (IMM) is bright, promising advancements across diverse machine learning domains. Further research should explore IMM’s applicability to more complex model architectures, beyond LSTMs and transformers, such as graph neural networks or diffusion models. Scalability remains a key challenge, and novel computational techniques are needed to efficiently handle large datasets and high-dimensional feature spaces. Investigating the optimal balance between accuracy and computational cost is crucial, particularly in resource-constrained environments. Furthermore, theoretical analyses should be conducted to better understand the generalizability and robustness of IMM, especially under noisy or incomplete data conditions. Combining IMM with other techniques, like transfer learning or data augmentation, may lead to even greater performance improvements. Finally, exploration of IMM in specialized applications, such as reinforcement learning, robotics, and medical diagnosis, would showcase its potential for real-world impact.

More visual insights#

More on figures

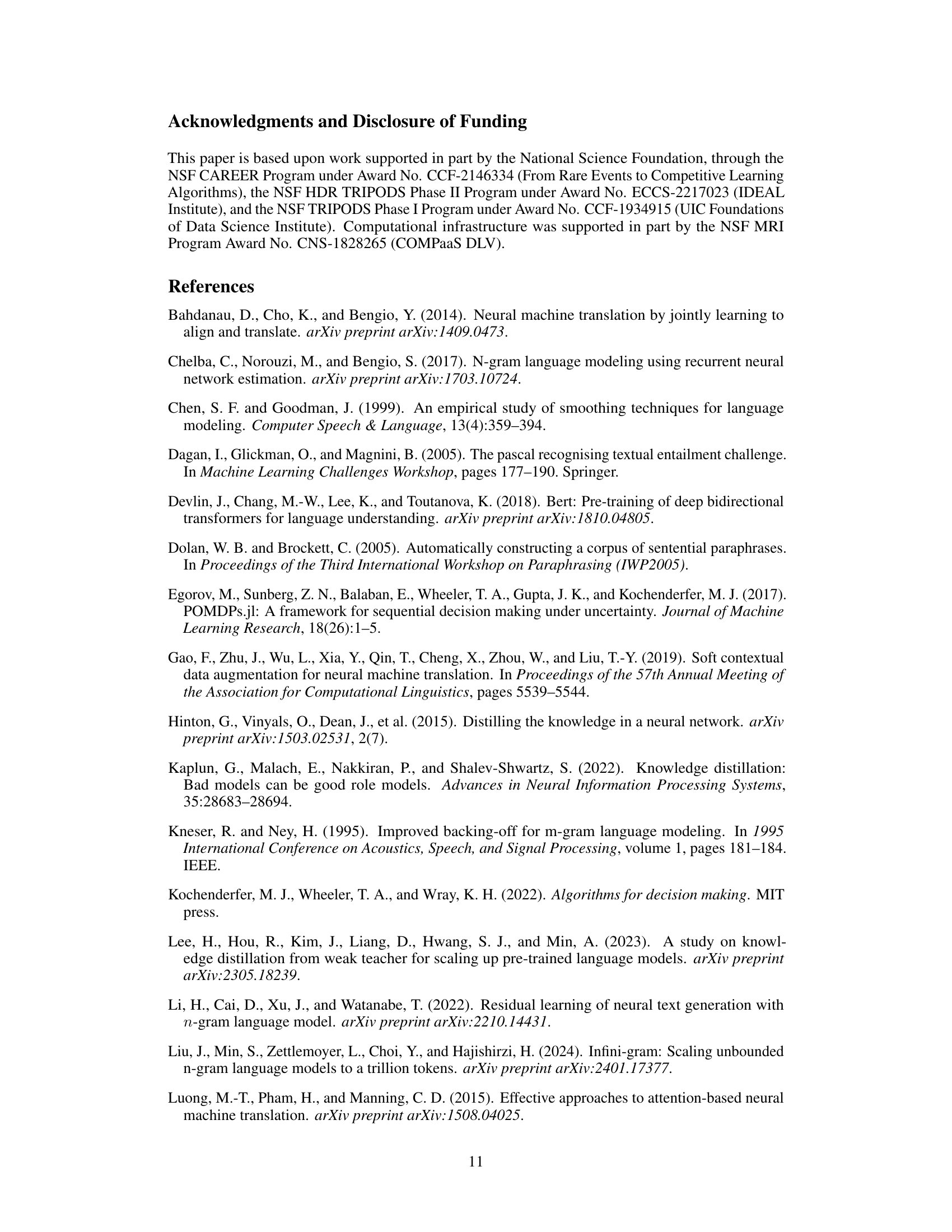

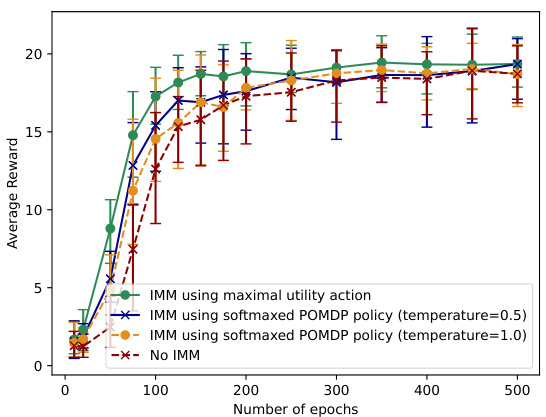

The figure shows the average reward achieved by an MDP (Markov Decision Process) agent trained with and without the IMM (Induced Model Matching) method. The MDP agent is trained using REINFORCE (Reinforcement Learning algorithm). A POMDP (Partially Observable Markov Decision Process) agent, trained on a limited observation space, is used to provide side information via the IMM method for improving the MDP training. The graph plots the average reward against the number of training epochs. Error bars represent 10th and 90th percentiles from multiple runs. The results show that incorporating the POMDP information via IMM leads to higher average reward and reduced variance.

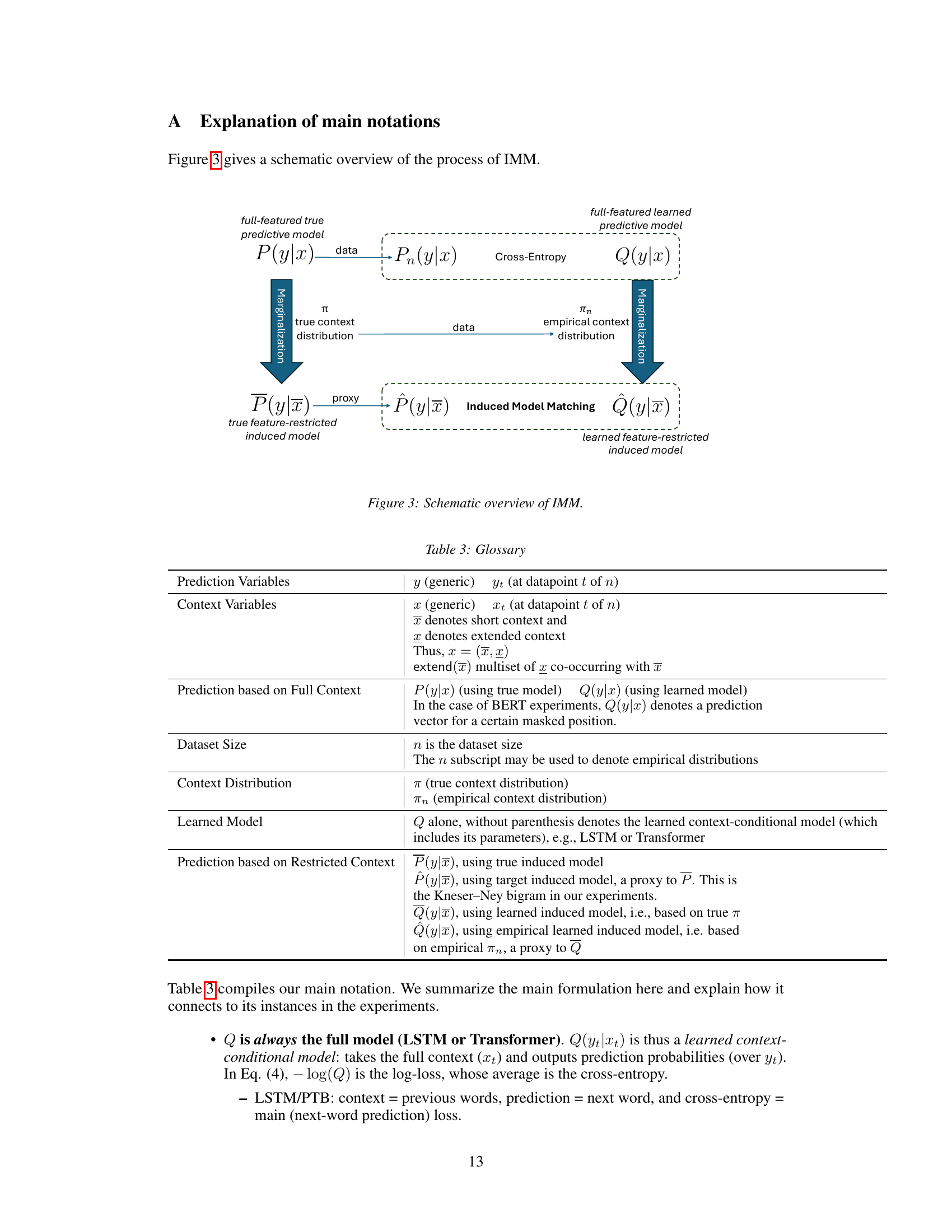

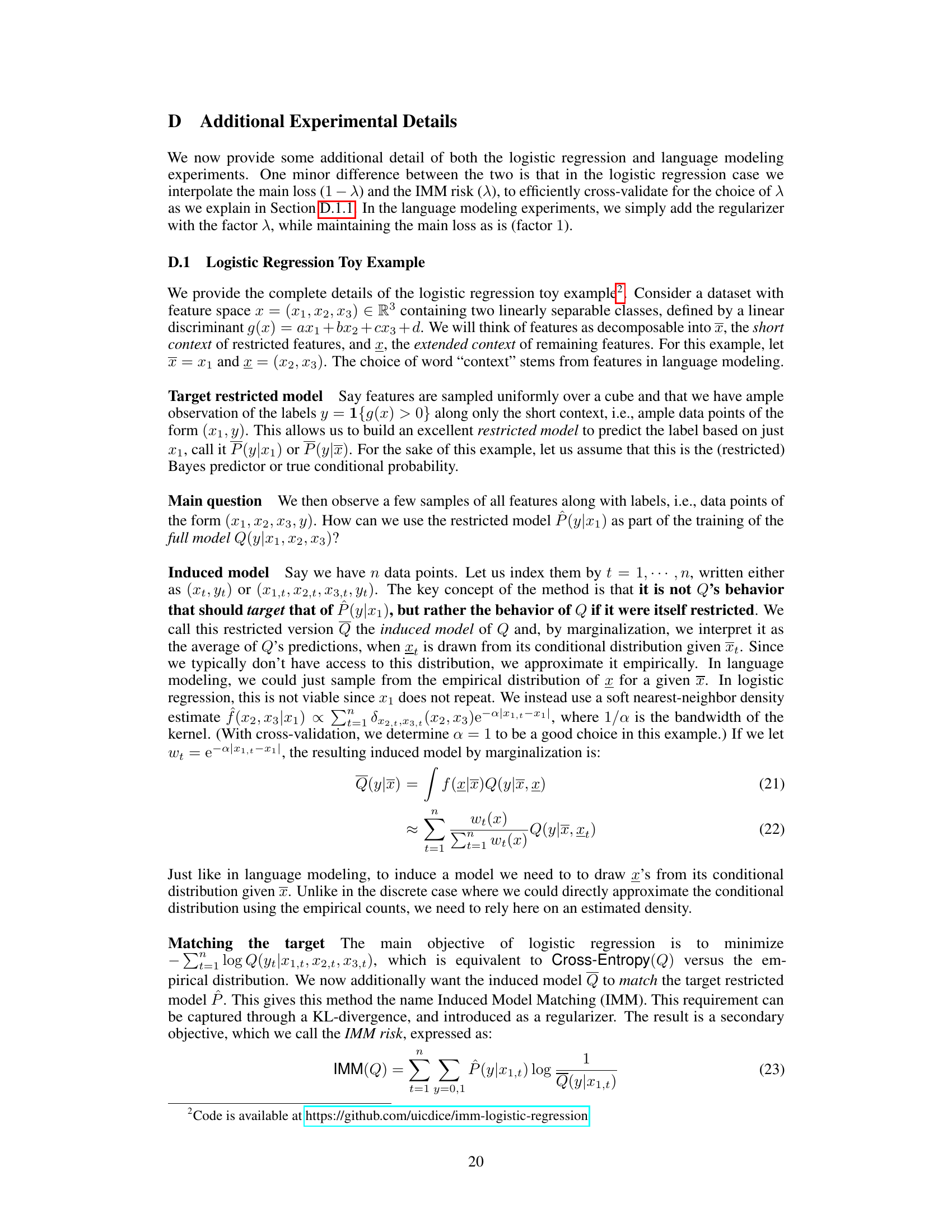

This figure shows a schematic overview of the Induced Model Matching (IMM) process. It illustrates how a full-featured true predictive model P(y|x) and its associated data are used to create a feature-restricted induced model P(y|x̄). Simultaneously, a full-featured learned predictive model Q(y|x) and its associated data are used to create a learned feature-restricted induced model Q(y|x̄). IMM then matches the proxy of the true feature-restricted induced model (P(y|x̄)) with the learned feature-restricted induced model (Q(y|x̄)). The true context distribution π and empirical context distribution πn are also shown to highlight the relationship between the true and empirical models.

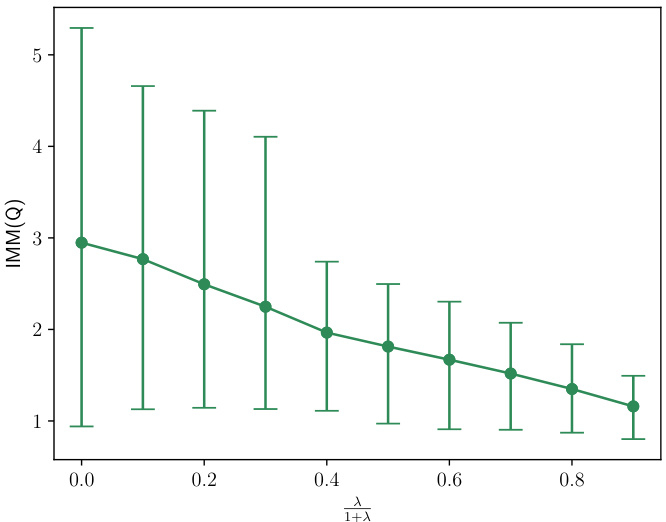

This figure shows the performance of the induced model Q on the restricted task (using only x1) as a function of the hyperparameter λ in the objective function. The y-axis represents the IMM(Q) value, and the x-axis shows the weight given to the IMM loss (λ/(1+λ)). It demonstrates that as the weight on the IMM loss increases, the performance of the induced model on the restricted task improves. The error bars show the variability across multiple runs.

This figure visualizes the inductive bias introduced by Induced Model Matching (IMM) in a 3D logistic regression example. The data points are uniformly sampled within a cube, and the Bayes-optimal restricted model uses only the x1 coordinate, assigning probabilities proportionally to the blue/red areas in the illustrated slice. IMM encourages the full logistic model to align with these weights, biasing the separating plane towards the correct inclination relative to the x1-axis, which speeds up learning.

This figure shows the test accuracy results of a logistic regression model trained with and without Induced Model Matching (IMM). The x-axis represents the size of the dataset used for training. The y-axis represents the test accuracy. Multiple runs (300) were performed, and the bars indicate the 10th to 90th percentiles of the accuracy across those runs. The figure demonstrates that using IMM consistently leads to higher accuracy and lower variance in the test accuracy compared to training without IMM.

This figure shows a heatmap representing the reward function used in the reinforcement learning experiment described in the paper. The reward is defined on an 11x11 toroidal grid, meaning the grid wraps around at the edges. The heatmap illustrates that the reward is highest in the center of the grid and decreases as the distance from the center increases.

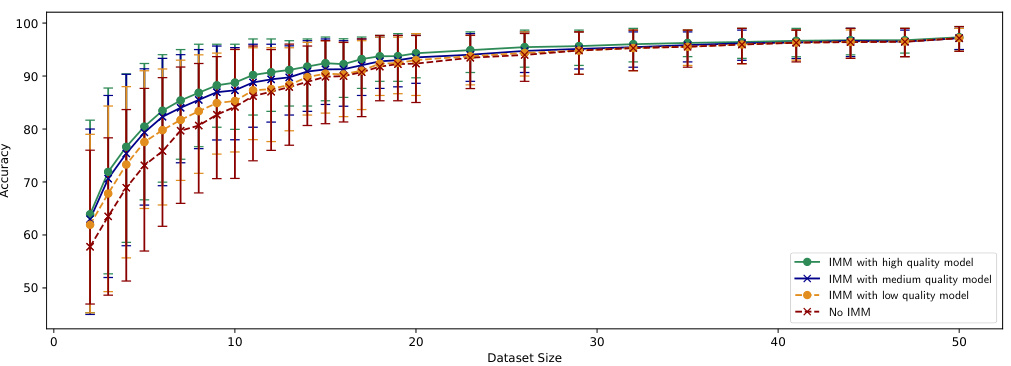

This figure shows the test accuracy of a logistic regression model trained with and without IMM, using restricted models of varying quality (high, medium, low). The x-axis represents the dataset size, and the y-axis shows the test accuracy. Error bars represent the 10th and 90th percentiles from 300 runs at each data point. The figure demonstrates that IMM consistently improves accuracy compared to training without it, even when using lower-quality restricted models. The improvement is most pronounced for smaller datasets.

The figure shows the average reward achieved by training an MDP policy with and without using IMM. The MDP is trained using REINFORCE, where the restricted model is a POMDP that only observes one coordinate of the agent’s position on an 11x11 toroidal grid. The x-axis represents the number of epochs (effectively the dataset size), and the y-axis shows the average reward achieved during the rollout horizon. Different lines represent the MDP trained without IMM, and the MDP trained with IMM using either the maximal utility action from the POMDP or a softmaxed POMDP policy with different temperatures. Error bars show 10th and 90th percentiles from 30 Monte Carlo runs. The plot demonstrates that incorporating information from the POMDP using IMM significantly improves the performance of the MDP, particularly with smaller datasets.

This figure compares the test accuracy of a logistic regression model trained with and without the Induced Model Matching (IMM) method. The x-axis represents the size of the dataset used for training, and the y-axis shows the accuracy. The graph displays that IMM consistently improves the accuracy of the model, particularly with smaller datasets. Error bars showing 10th to 90th percentiles over 300 runs are included to show variability. The figure provides visual evidence supporting the claim that IMM enhances model performance.

This figure shows the test accuracy results of a logistic regression model trained with and without Induced Model Matching (IMM). The x-axis represents the size of the dataset used for training, and the y-axis shows the test accuracy. Multiple runs (300) were conducted, and error bars represent the 10th to 90th percentiles of the accuracy results. The graph demonstrates that IMM improves the accuracy of the logistic regression model, especially when the training dataset is relatively small.

More on tables

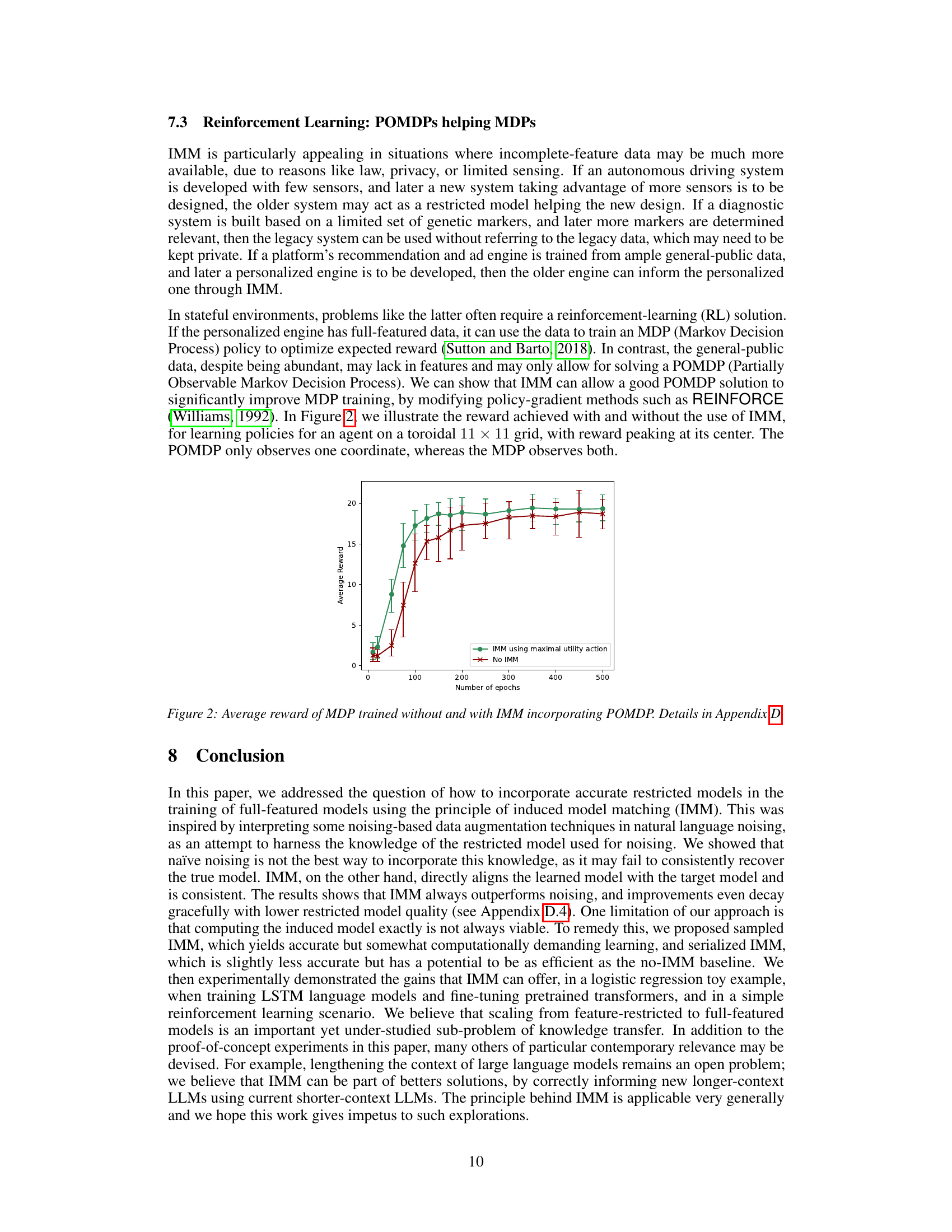

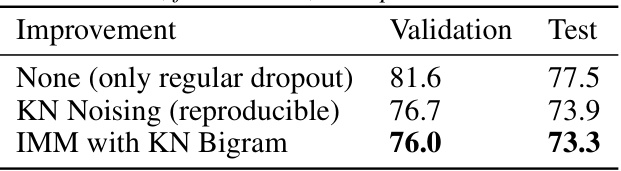

This table shows the results of experiments using the BERTBASE language model on several GLUE tasks. Three configurations are compared: the baseline BERTBASE model, the model with the Masked Language Model (MLM) objective added, and the model with the Induced Model Matching (IMM) method added in addition to MLM. The metrics used vary depending on the specific task (Matthew’s Correlation Coefficient for COLA, F1 score for MRPC, and accuracy for QNLI and RTE). All results are averages across multiple restarts.

This table shows the perplexity results for an LSTM language model trained on the Penn TreeBank dataset using different methods: no regularization, KN noising (a data augmentation technique), and IMM with KN bigrams. The table compares the validation and test perplexity scores achieved by each method and highlights the improvement achieved by IMM over other methods. Lower perplexity indicates better performance.

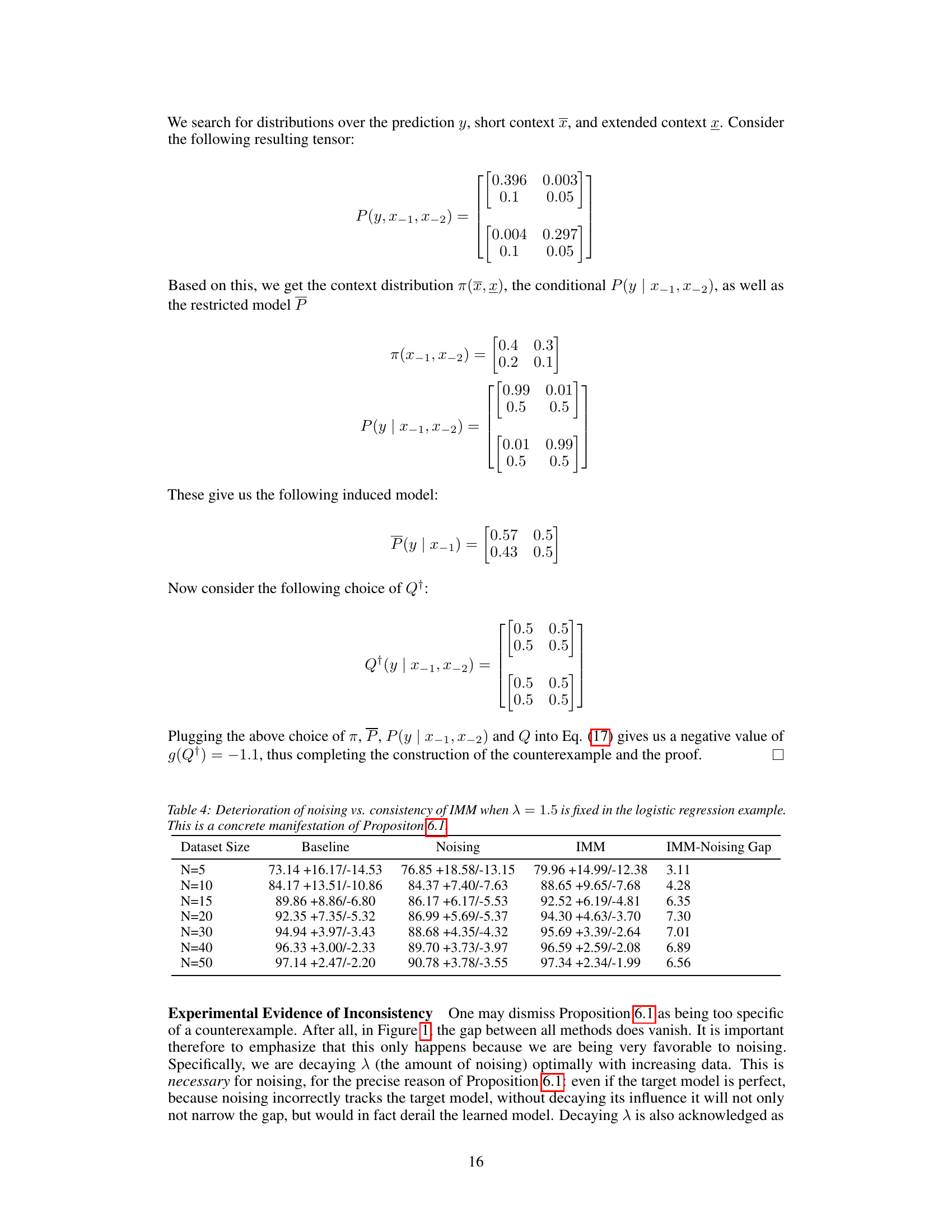

This table presents the performance comparison between the baseline, noising, and IMM methods across different dataset sizes in a logistic regression experiment where the regularization parameter λ is fixed at 1.5. The ‘IMM-Noising Gap’ column shows the difference in performance between IMM and noising, highlighting IMM’s improvement. The results demonstrate IMM’s consistent superior performance compared to noising, even as the dataset size increases.

This table compares the performance of a Kneser-Ney bigram model and an LSTM model (with and without IMM) on a bigram prediction task using the Penn TreeBank dataset. It demonstrates that a simple bigram model outperforms the LSTM on this restricted task, highlighting the potential benefits of incorporating restricted model knowledge when training full-featured models. The table shows that IMM improves the LSTM’s performance on this task.

Full paper#