↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) often fail to generalize well to unseen data, a problem known as out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization. This paper focuses on a specific aspect of OOD, called compositional generalization, and introduces a new way to evaluate it called “rule extrapolation.” Rule extrapolation studies how well LLMs can extend rules learned from training data to new, unseen situations, where some rules are broken. The study uses formal languages to create controlled test scenarios that allow for precise measurement of OOD performance.

The researchers evaluate the performance of several different types of language models, including recurrent neural networks (RNNs), transformers, and state-space models, on a variety of formal languages. The experiments reveal that the performance of different LLMs varies greatly depending on the specific type of language and the types of rules violated. This research also lays the groundwork for a new theoretical framework based on algorithmic information theory to explain and predict OOD generalization behavior in LLMs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses the critical issue of out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization in large language models (LLMs), a significant limitation hindering their real-world applicability. By introducing the novel concept of rule extrapolation and using formal languages, this research provides a rigorous framework for evaluating compositional generalization and opens new avenues for theoretical understanding and practical improvements in LLMs. The findings challenge common assumptions about LLM architecture and highlight the need for considering inductive biases in model design for better OOD performance. This work also provides a normative theory which lays down foundations for designing future models with enhanced OOD generalization capabilities.

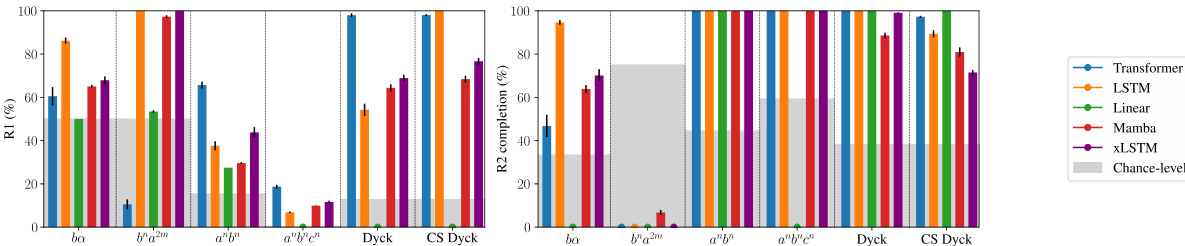

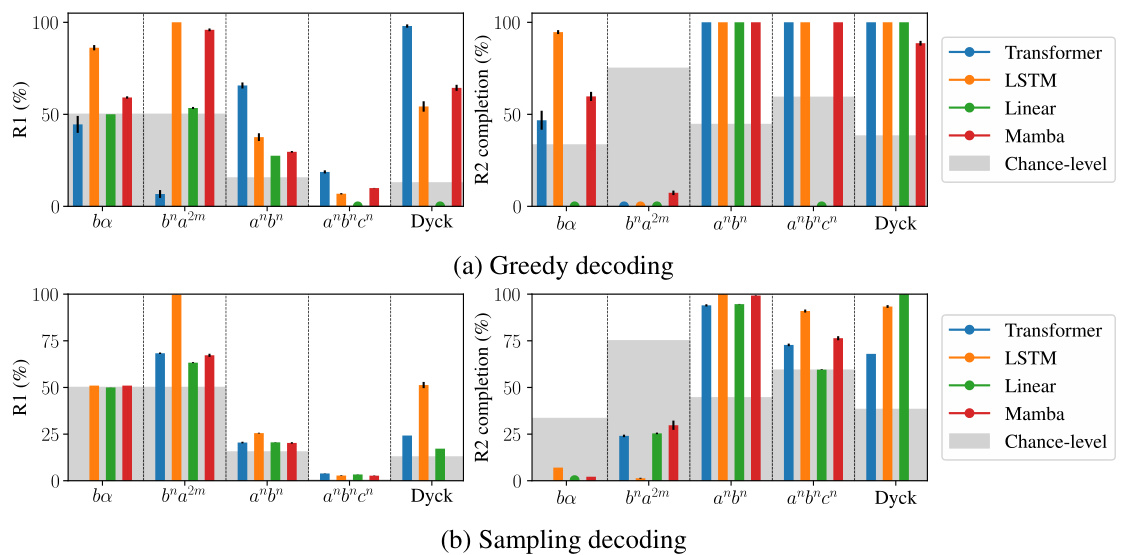

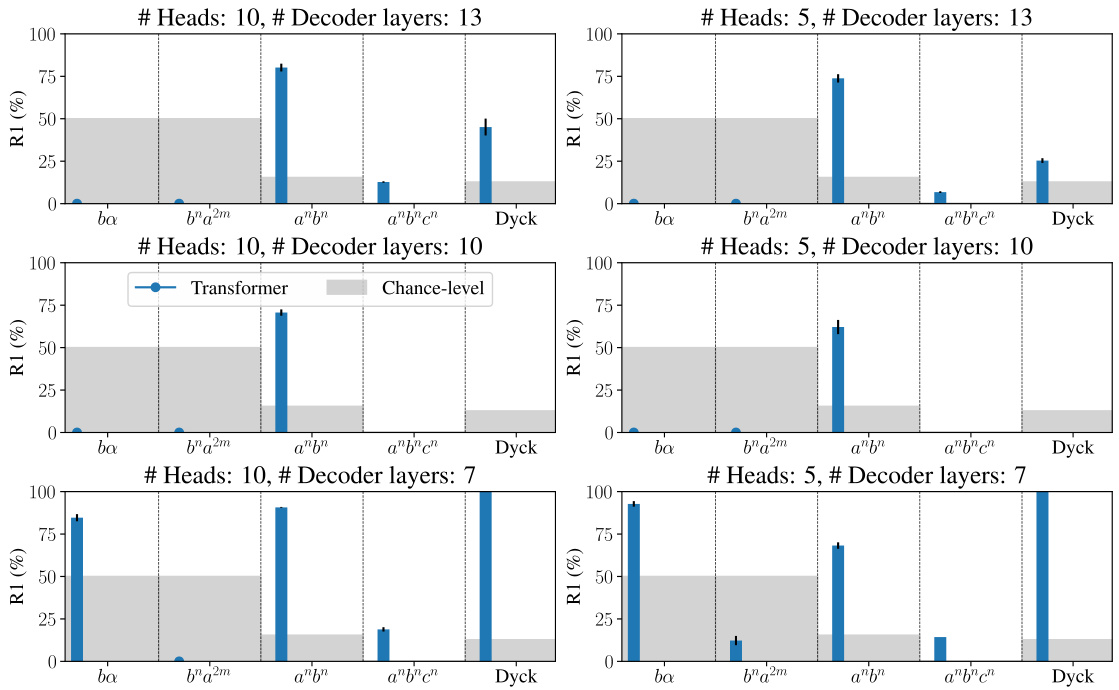

Visual Insights#

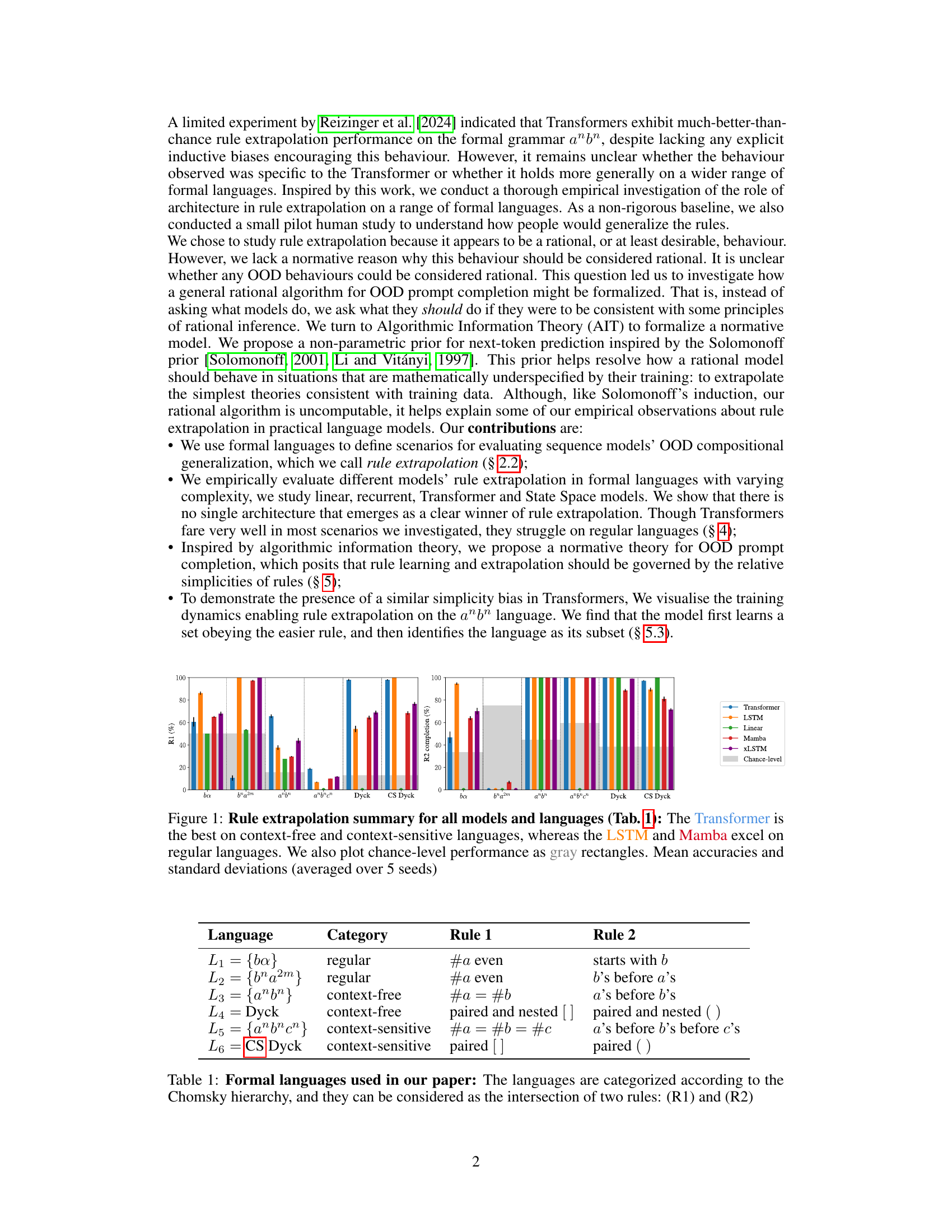

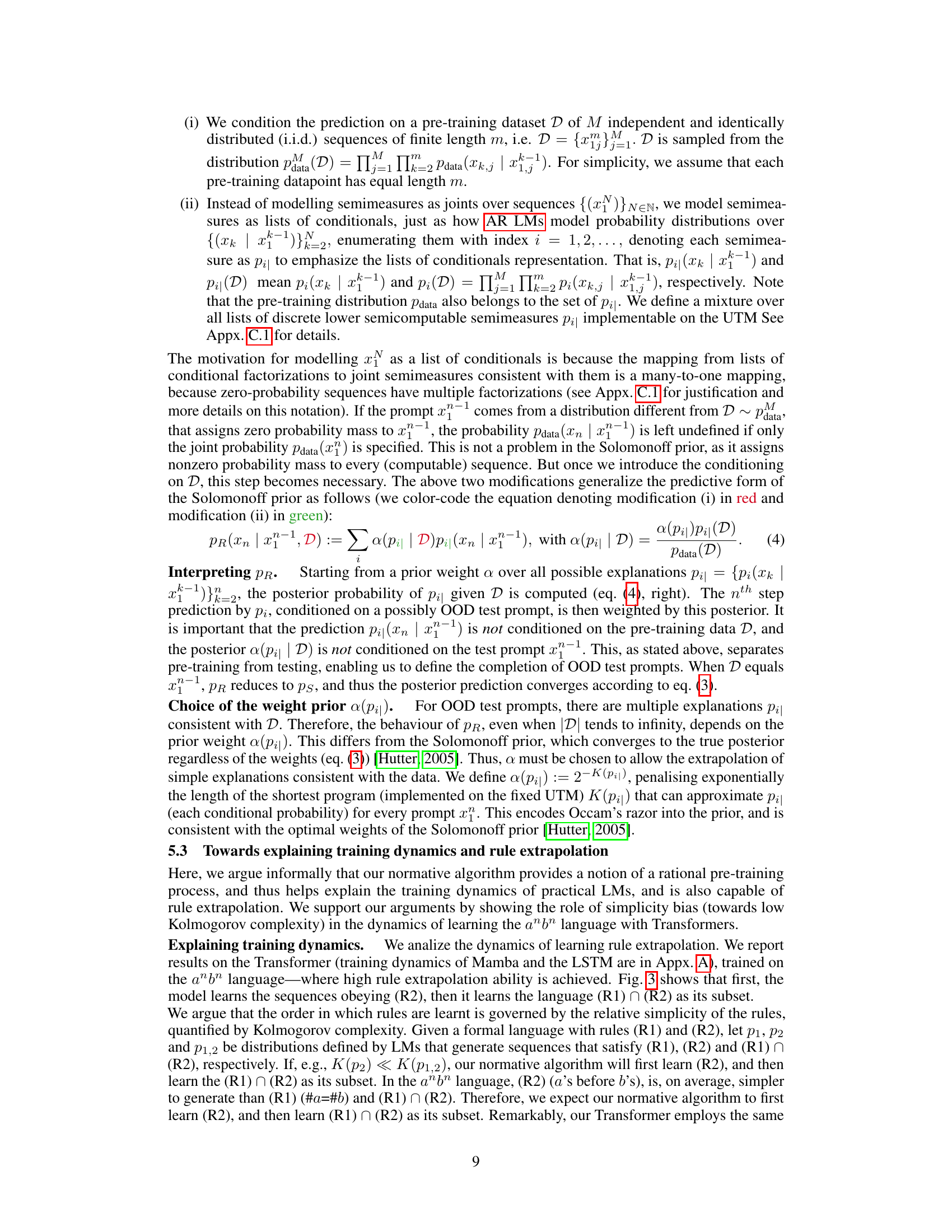

This figure summarizes the performance of different language models (Transformer, LSTM, Linear, Mamba, XLSTM) on various formal languages (regular, context-free, and context-sensitive) in terms of rule extrapolation. The x-axis represents the languages, and the y-axis represents the accuracy of the models in completing the prompts. The Transformer generally outperforms other models on context-free and context-sensitive languages, while LSTM and Mamba show better performance on regular languages. Chance-level accuracies are also displayed for comparison.

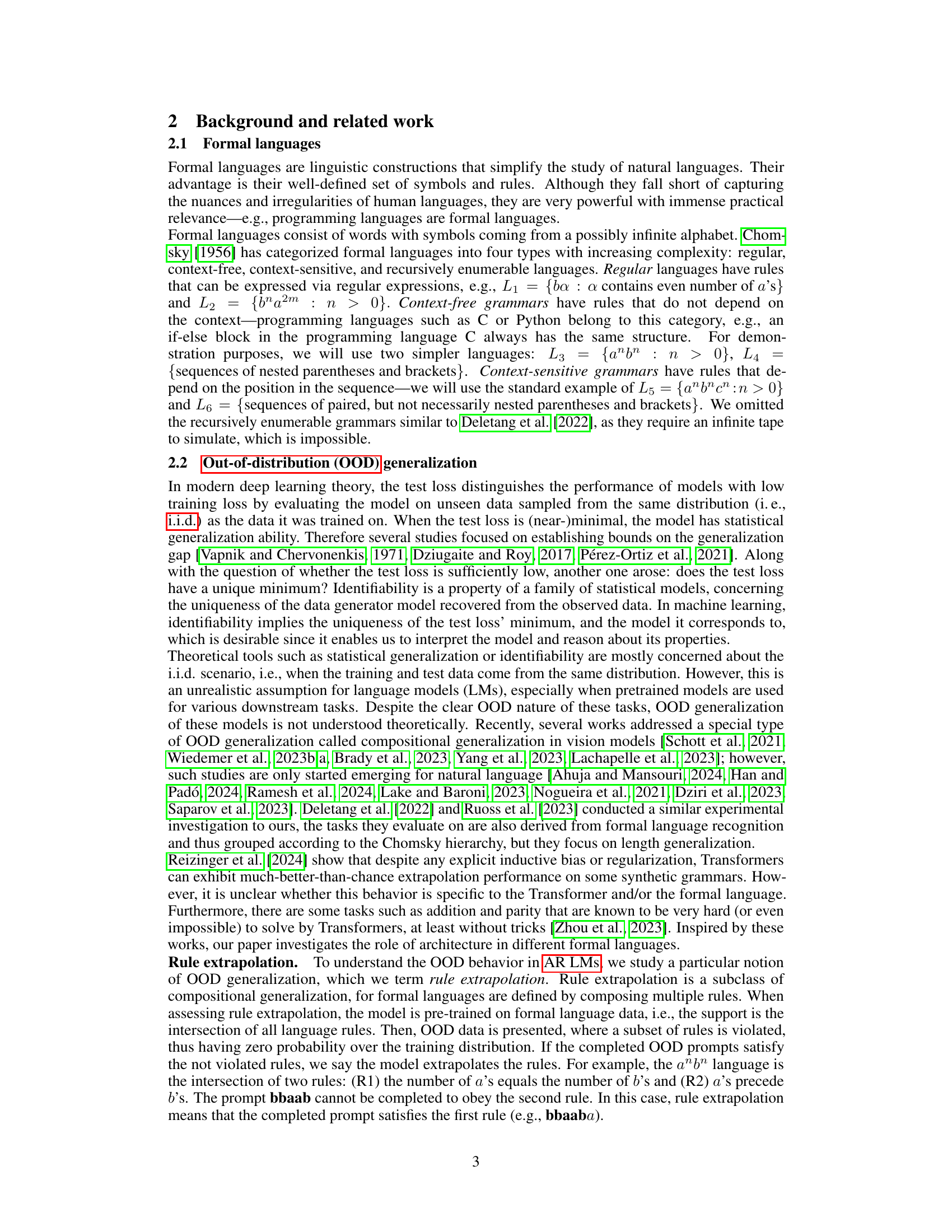

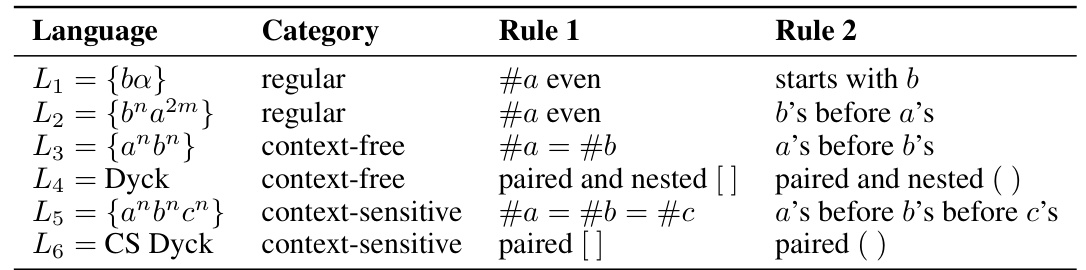

This table lists six formal languages used in the paper, categorized according to the Chomsky hierarchy (regular, context-free, context-sensitive). Each language is defined by the intersection of two rules (R1 and R2). The table is crucial for understanding the experimental setup, as these languages are used to evaluate the models’ ability to extrapolate rules in out-of-distribution scenarios.

In-depth insights#

Rule Extrapolation#

The concept of “Rule Extrapolation” presents a novel approach to evaluating the out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization capabilities of language models. Instead of focusing on overall performance, it dissects the model’s ability to extrapolate individual rules governing a formal language, even when other rules are violated. This granular analysis offers deeper insights into how models handle compositional generalization. By employing formal languages with varying complexity, the research can systematically probe the influence of architecture, revealing whether certain designs exhibit inherent biases towards rule extrapolation. The introduction of a normative theory based on algorithmic information theory provides a valuable framework for assessing not just what models do, but what they should do in such OOD scenarios. This provides a rational basis to evaluate OOD behaviour and helps explain empirically observed biases towards simpler rules. Formal languages offer a controlled environment to rigorously study these behaviors, but the study highlights the need to extend research to more complex, naturalistic language scenarios. Overall, “Rule Extrapolation” offers a significant step forward in understanding the OOD generalization phenomenon in language models.

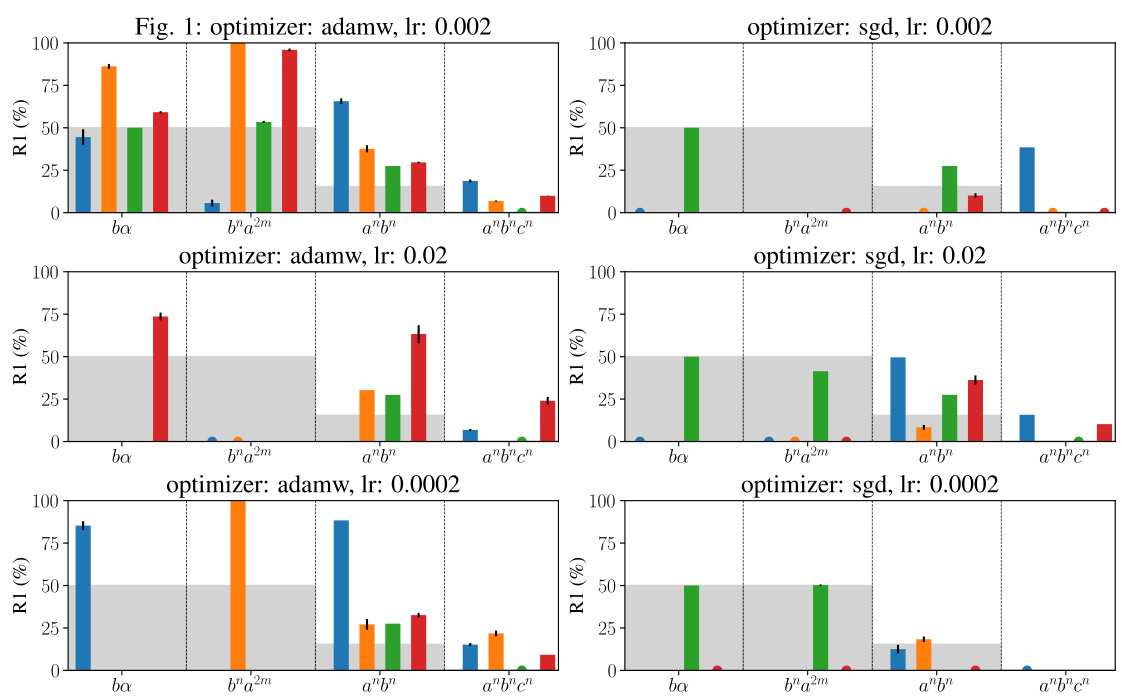

Model Architectures#

The effectiveness of various model architectures in handling out-of-distribution (OOD) data, specifically within the context of rule extrapolation in formal languages, is a central theme. The study compares the performance of linear models, LSTMs, Transformers, and State Space Models (SSMs), each possessing distinct inductive biases. The results reveal that no single architecture universally excels; Transformers show strength in context-free and context-sensitive languages, while LSTMs and SSMs (Mamba) outperform on regular languages. This highlights the importance of architectural considerations when addressing OOD generalization, and suggests that the optimal architecture is heavily dependent on the complexity and structure of the underlying language or task. Further investigation into the interplay between inductive biases and the capacity for rule extrapolation is warranted to fully understand these findings.

Formal Language#

The concept of formal languages plays a crucial role in the paper, serving as a controlled environment to investigate the out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization capabilities of language models. Formal languages, with their precisely defined syntax and rules, offer a distinct advantage over natural language datasets, which are often noisy and ambiguous. By focusing on formal languages, the study isolates the impact of architectural design on the models’ capacity to extrapolate rules beyond their training data. This approach allows for a more systematic investigation, enabling a finer-grained analysis of model behaviors in OOD scenarios and providing valuable insights into how various language model architectures approach compositional generalization. The choice of formal languages of varying complexities, ranging from regular to context-sensitive, is particularly insightful, allowing the researchers to probe the limits of different architectural designs and discern their strengths and weaknesses in handling complex grammatical structures. This rigorous approach significantly enhances the reliability and interpretability of the study’s findings.

Normative Theory#

The paper introduces a ‘Normative Theory’ section to address the limitations of existing approaches to out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization. Instead of merely observing model behavior, the authors aim to establish what a rational model should do. This is achieved by proposing a novel prior inspired by Solomonoff’s induction, which is a framework from algorithmic information theory. This prior assigns higher probabilities to simpler explanations consistent with training data, reflecting Occam’s razor. By conditioning this prior on training data, the authors enable the prediction of OOD prompts’ completions based on the simplest consistent explanation, which offers a rational basis for rule extrapolation, a specific type of compositional generalization. The uncomputability of this prior is acknowledged, but its value lies in providing a normative benchmark and explaining empirically observed model behaviors, particularly the simplicity bias of Transformers.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this rule extrapolation study are multifaceted. Extending the investigation beyond formal languages to encompass real-world datasets and more complex linguistic structures is crucial to validate the generalizability of the findings and assess the practical impact of the proposed normative theory. A deeper analysis of the interplay between architectural choices and rule extrapolation performance across various model sizes and training regimes is warranted. Investigating the efficacy of alternative training paradigms, beyond the current implementations, to optimize rule extrapolation and potentially bridging the gap between human and model performance would prove highly insightful. Finally, refining the normative theory by exploring computationally feasible approximations of the Solomonoff prior and integrating insights from mechanistic interpretability would strengthen the theoretical foundation of this significant area of research. This would permit stronger links to be made between the normative theory and the empirical observations, furthering our understanding of compositional generalization in language models.

More visual insights#

More on figures

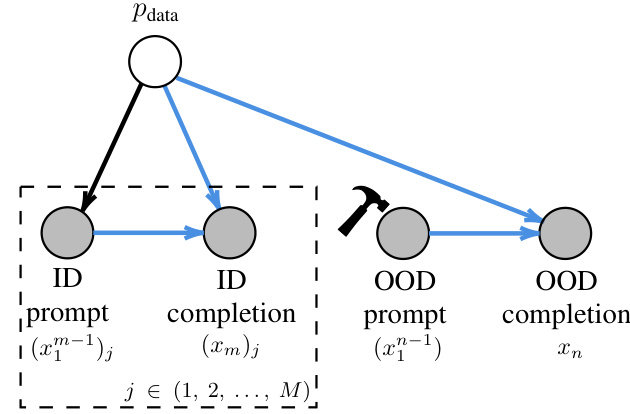

This figure is a graphical model showing how the proposed method for out-of-distribution (OOD) prompt completion works. The model assumes that the language model (LM) generates both in-distribution (ID) and OOD completions independently, following the same procedure. The blue connections in the graph represent this shared process. Despite the LM assigning zero probability to the OOD prompt, a conditional probability distribution for the OOD completions is defined, allowing the model to predict a completion even in this low-probability scenario.

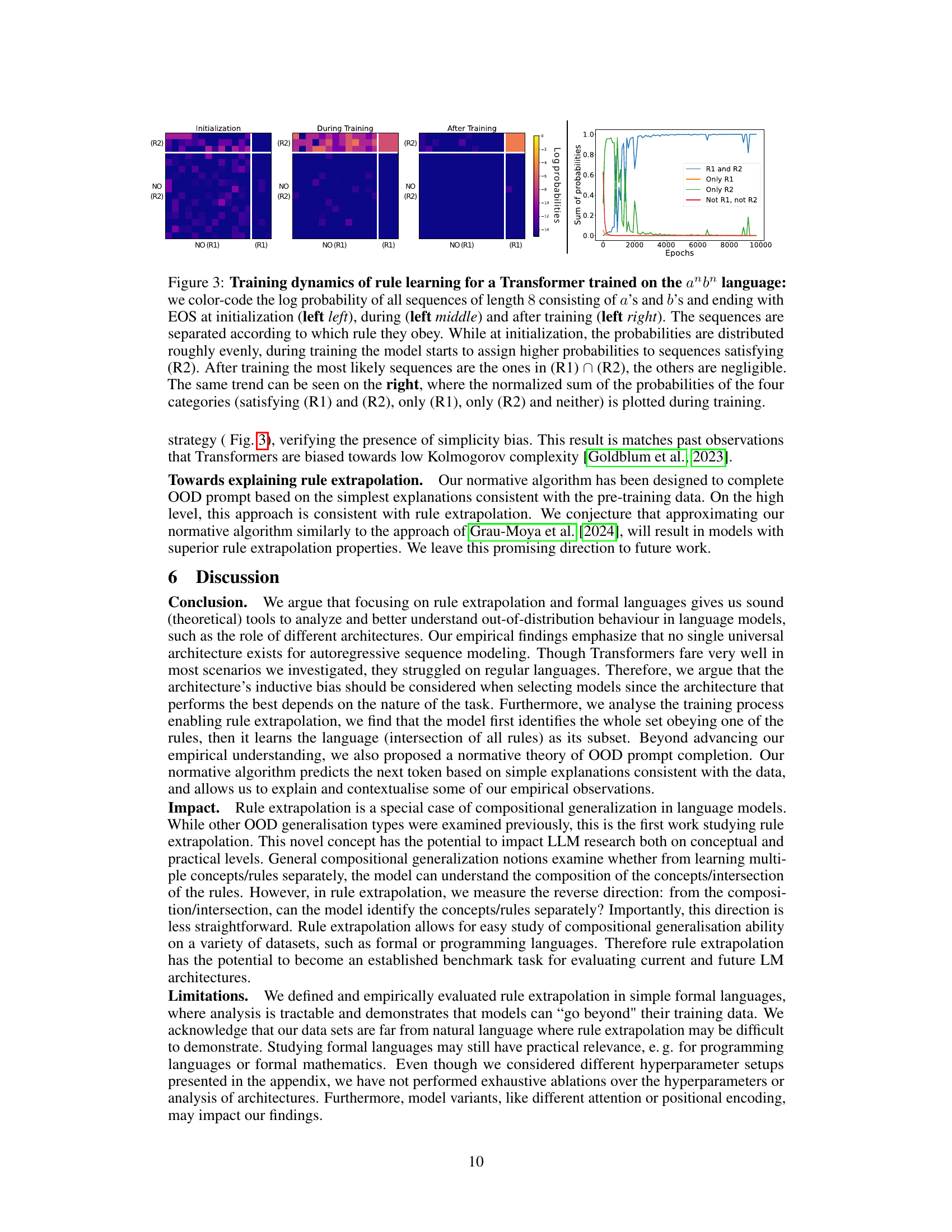

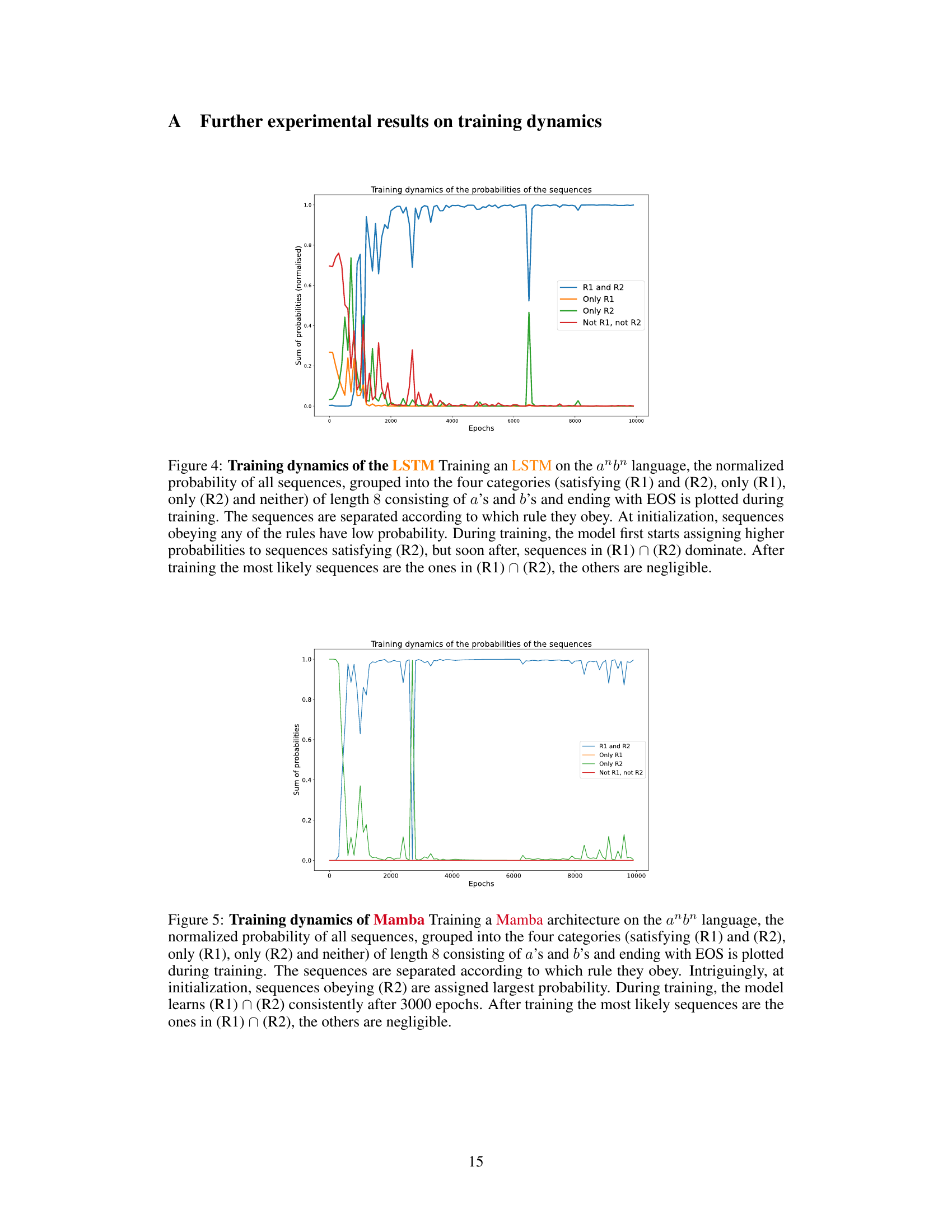

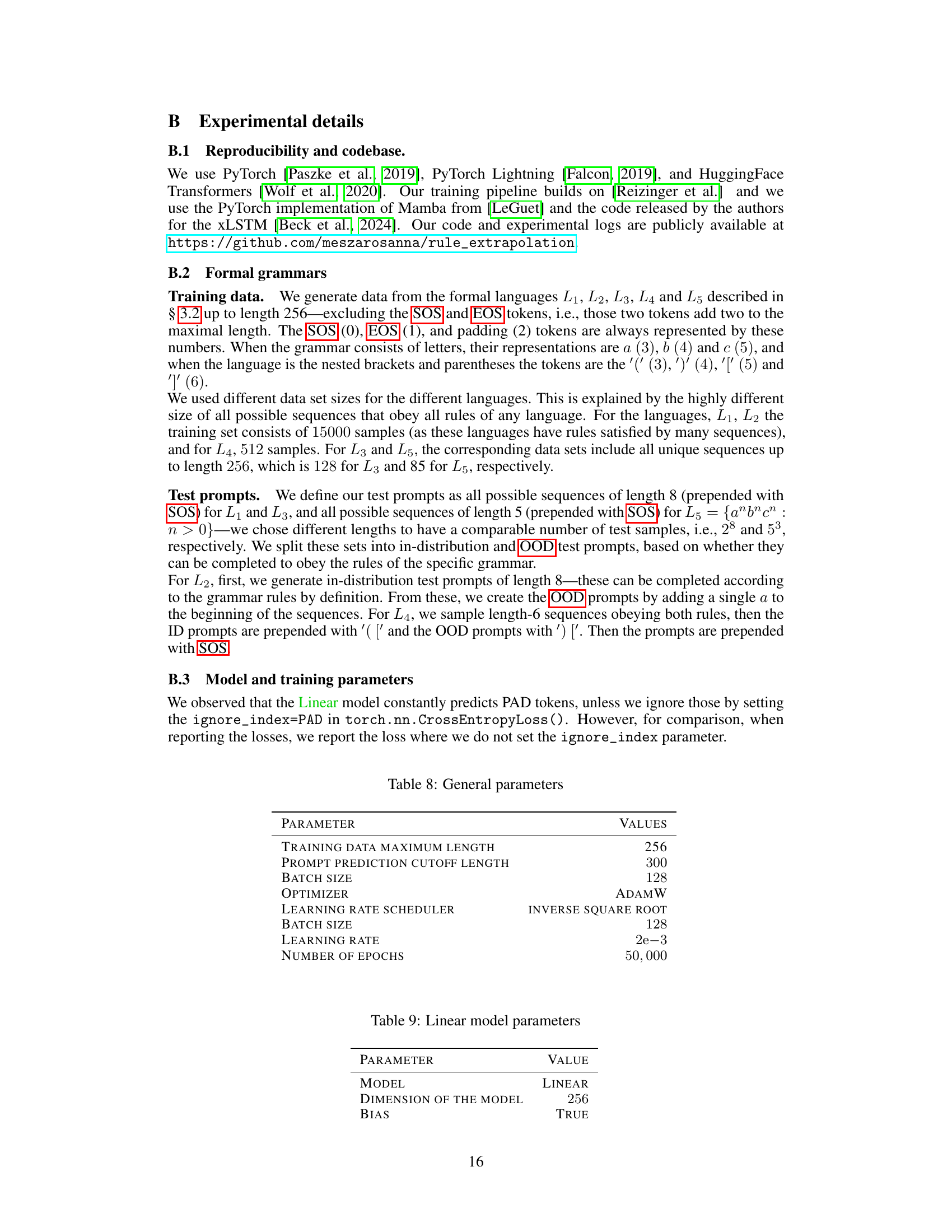

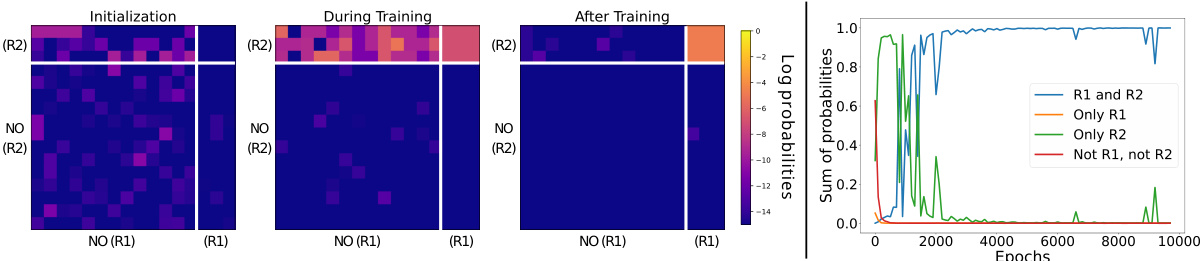

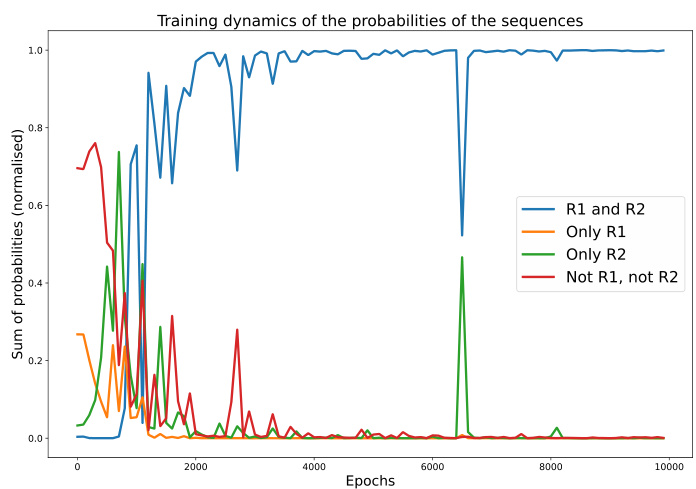

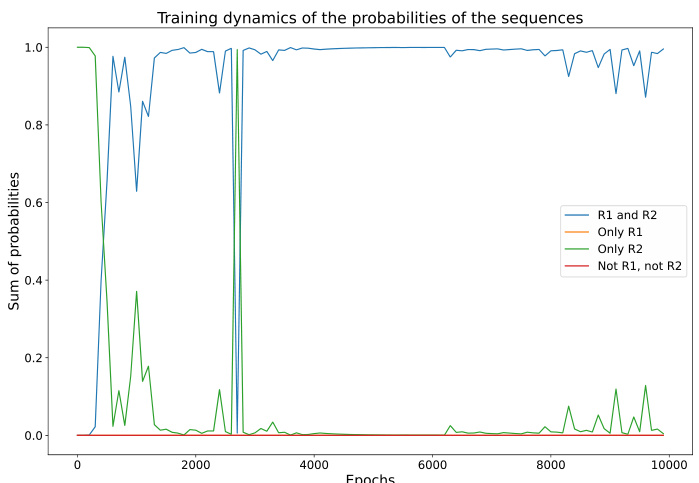

This figure visualizes the training dynamics of a transformer model on the anbn formal language. The heatmaps show the log probabilities of sequences of length 8, categorized by whether they satisfy rule R1, R2, both, or neither. The line graph shows the normalized sum of probabilities for each category over training epochs. The visualization demonstrates that the model initially assigns probabilities relatively evenly across categories but learns to favor sequences satisfying R2 first and eventually those satisfying both R1 and R2.

This figure visualizes the training dynamics of a Transformer model on the anbn language. The left panels show heatmaps of log probabilities for sequences of length 8, categorized by which rules (R1 and R2) they satisfy. The right panel shows the evolution of the normalized probabilities of these four categories over training epochs. The results illustrate how the model learns the rules sequentially, initially prioritizing rule R2 (a’s before b’s), then converging to correctly generate sequences obeying both R1 (#a=#b) and R2.

This figure shows the training dynamics of a transformer model learning the formal language anbn. The left panels show heatmaps of log probabilities for sequences of length 8, categorized by whether they satisfy rules R1 and R2, or only one of them, or neither. The right panel shows the evolution of the sum of probabilities for each category over training epochs. The visualization demonstrates a bias towards learning rule R2 first, then subsequently learning the intersection of both rules (R1 ∩ R2).

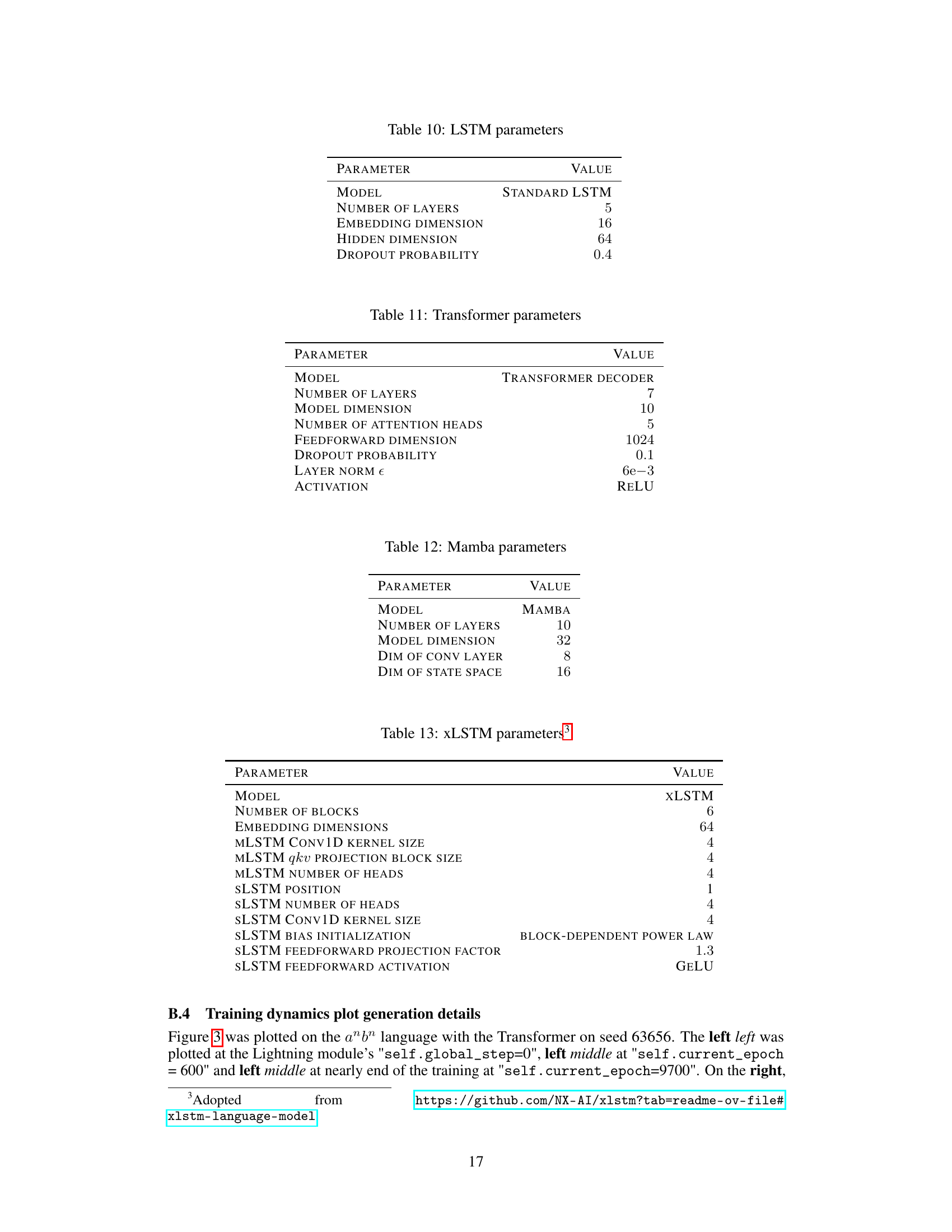

This figure compares the performance of different language models (Transformer, LSTM, Linear, Mamba) on rule extrapolation tasks using two different decoding methods: greedy decoding and sampling decoding. The models are evaluated on several formal languages (L1-L5) with varying complexity. The figure visually presents the accuracy of each model in completing sequences according to rule 1 (R1) and the completion of rule 2 (R2), which is only partially satisfied, highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of each model under different decoding strategies and across different language complexities. The chance-level performance is also included as a baseline.

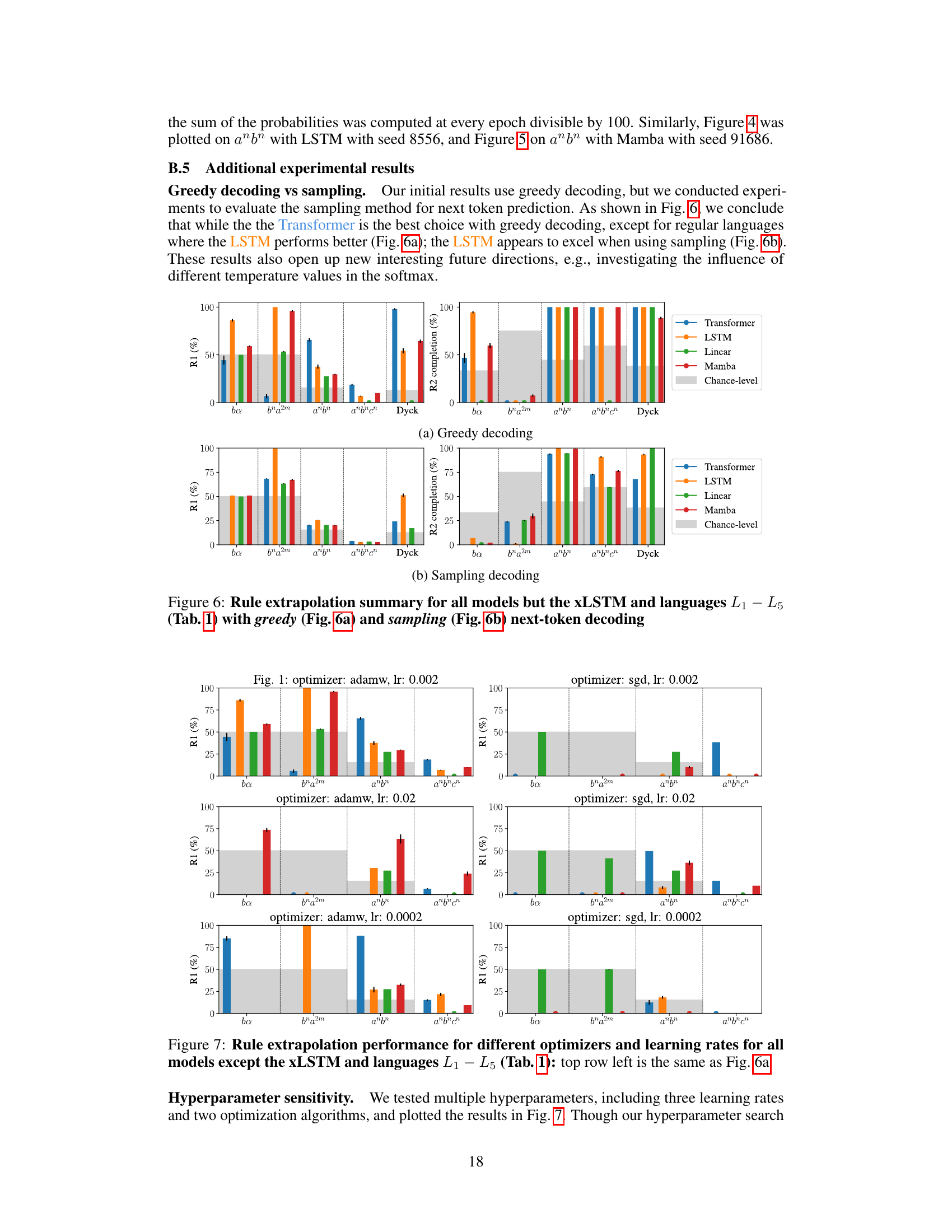

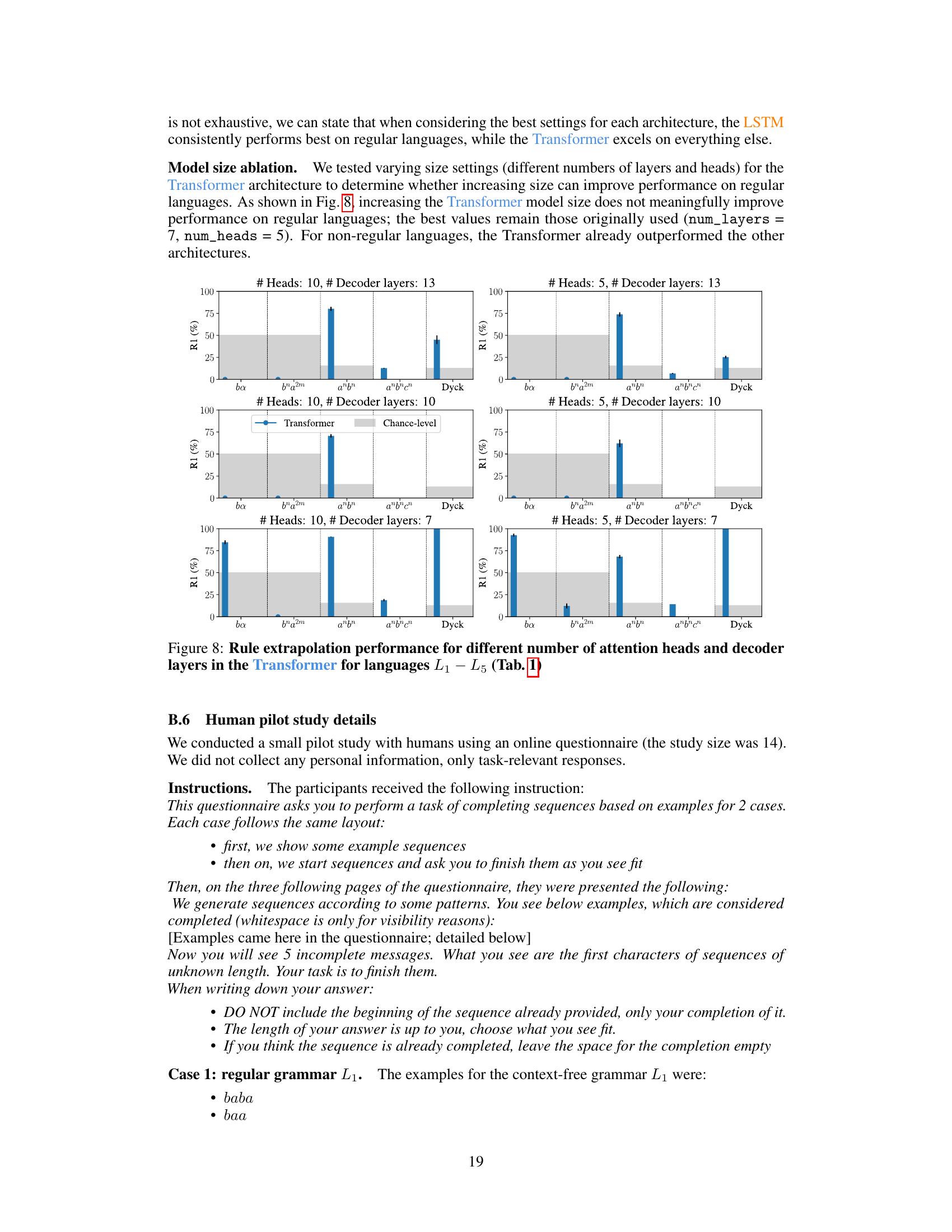

This figure summarizes the rule extrapolation performance of different models (Transformer, LSTM, Linear, Mamba) across six formal languages of varying complexity (regular, context-free, context-sensitive). The bar chart displays the accuracy of each model in completing OOD prompts that violate at least one rule of the language, showing how well the models extrapolate the remaining rules. The gray rectangles indicate the chance level accuracy for each language, representing the performance expected from a random guess. The Transformer achieves the highest accuracy for the context-free and context-sensitive languages, while the LSTM and Mamba perform best on the regular languages.

This figure summarizes the performance of various language models (Transformer, LSTM, Linear, Mamba) on rule extrapolation tasks across six formal languages with different complexities (regular, context-free, context-sensitive). The bar chart displays the accuracy of each model in completing sequences while adhering to at least one of the two rules defining each language, even when another rule is violated. The gray rectangles represent the chance-level accuracy for each task. The results indicate that the Transformer generally outperforms others on more complex languages, while LSTM and Mamba are better suited for regular languages.

More on tables

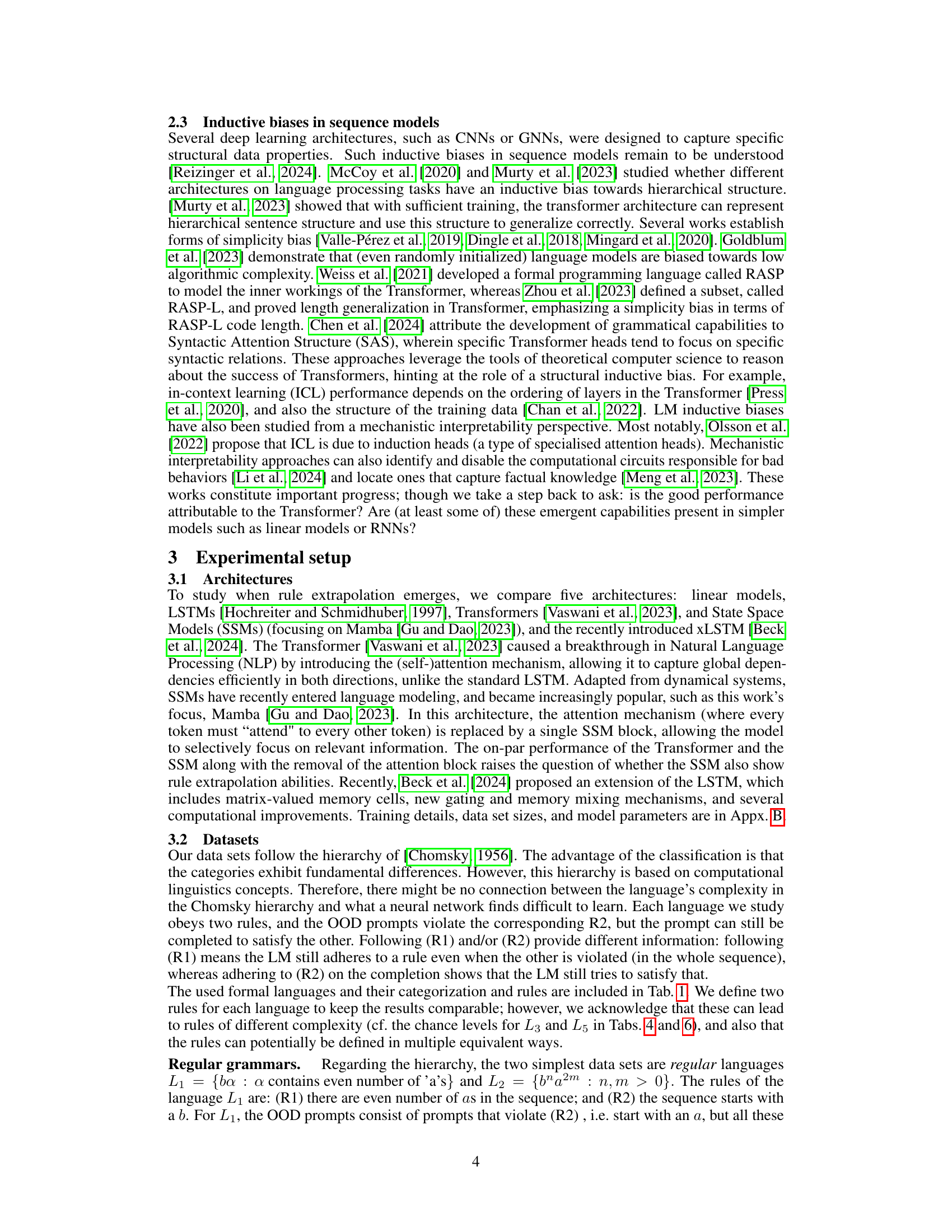

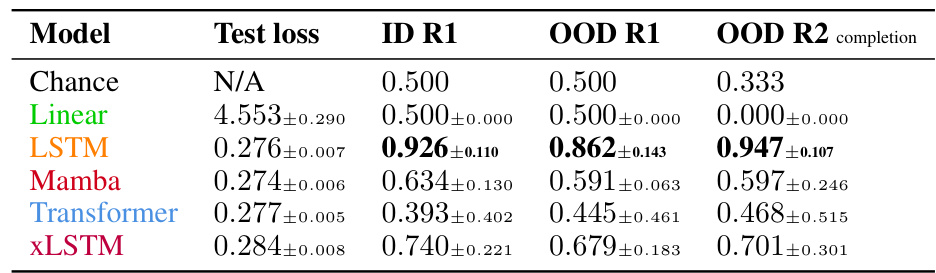

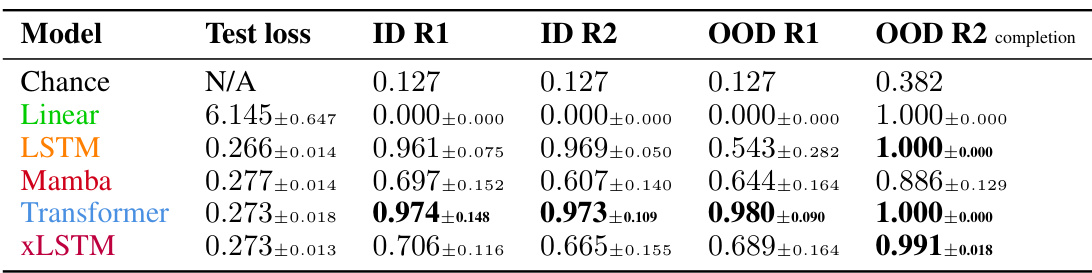

This table presents the results of evaluating different language models on a regular language (L1 = {ba}). The models were assessed based on their test loss, their ability to follow rule 1 (R1) in the in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) settings, and their ability to follow rule 2 (R2) in the OOD setting. Note that R2 is inherently satisfied by design for the in-distribution set and thus omitted from this section of the table. The LSTM model exhibits the highest accuracy in extrapolating rule 1 to the OOD data.

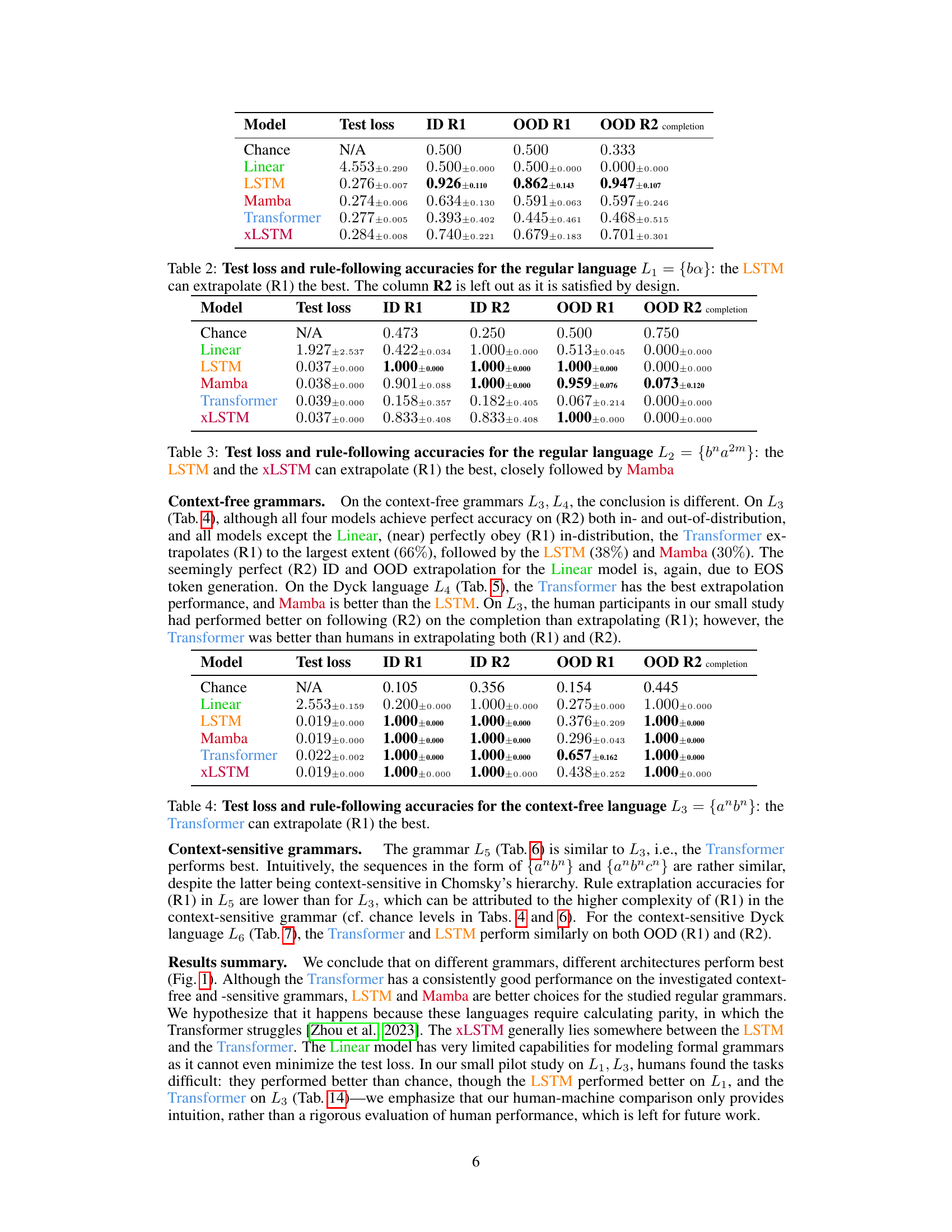

This table presents the test loss and rule-following accuracies for the regular language L2, where the models are evaluated on their ability to extrapolate rule 1 (R1). The LSTM and XLSTM models achieve the highest accuracies in extrapolating R1, followed closely by the Mamba model. The table also includes results for rule 2 (R2) completion, which is not directly comparable as it measures performance on a task designed to always satisfy R2.

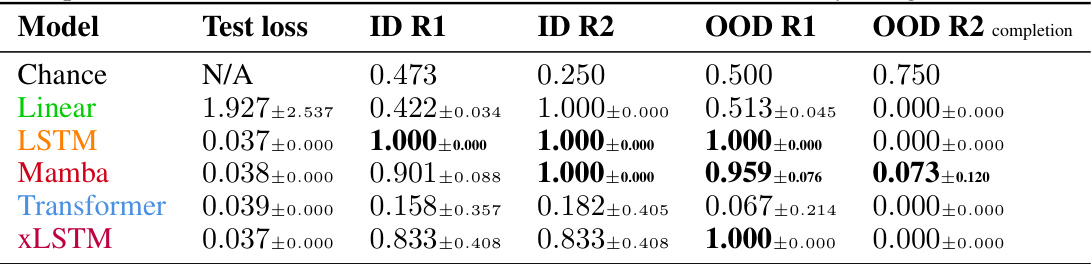

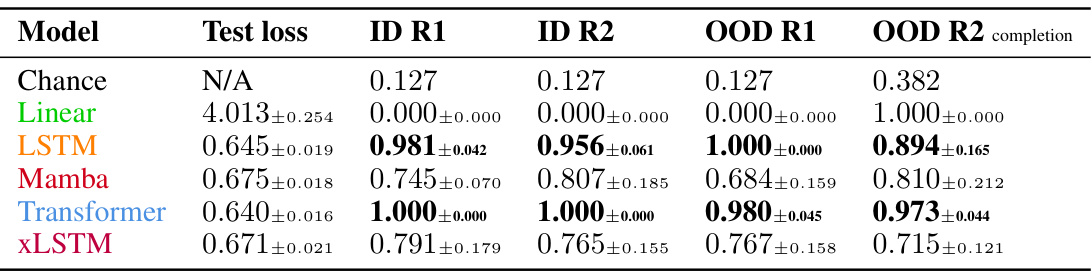

This table presents the results of evaluating different language models on a context-free language (L3 = {anbn}). The models were tested on their ability to extrapolate rule 1 (R1) which is that the number of ‘a’s equals the number of ‘b’s, when rule 2 (R2) is violated, meaning the ‘a’s do not precede the ‘b’s. The table shows the test loss, the accuracy of following rule 1 in the in-distribution data, the accuracy of following rule 2 in the in-distribution data, the accuracy of extrapolating rule 1 in the out-of-distribution data, and the accuracy of completing sequences while satisfying rule 2 in the out-of-distribution data. The Transformer model achieves the highest accuracy in extrapolating rule 1, indicating its superior ability to generalize this specific rule to out-of-distribution scenarios.

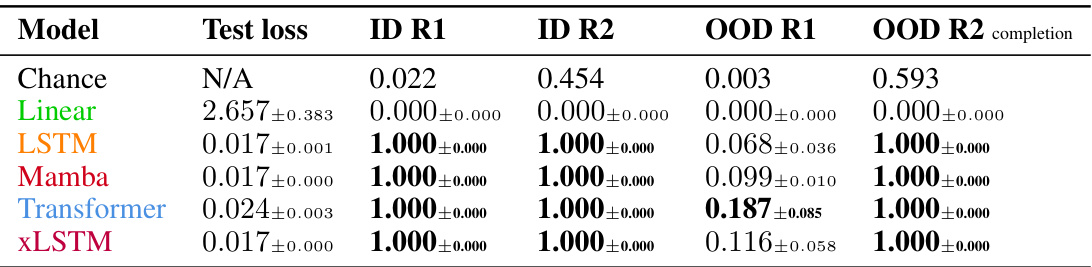

This table presents the results of evaluating five different models (Linear, LSTM, Mamba, Transformer, and XLSTM) on a context-free Dyck language (L4). The models were evaluated on their ability to follow two rules (R1 and R2), both in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD). The ‘Test loss’ column shows the model’s performance during training. The ‘ID R1’ and ‘ID R2’ columns indicate the accuracy of the models in adhering to rules R1 and R2, respectively, on in-distribution data. Conversely, the ‘OOD R1’ and ‘OOD R2 completion’ columns show the accuracy of the models in following rules R1 and R2 on out-of-distribution data, where R2 is intentionally violated. The results reveal the Transformer model’s superior performance in extrapolating rule R1.

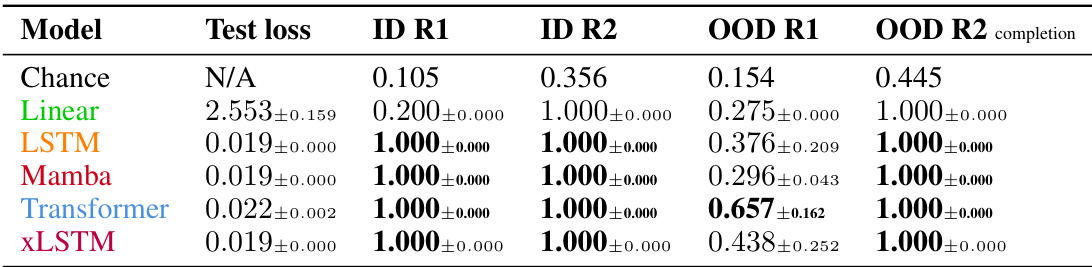

This table presents the results of the experiment on the context-sensitive language L5. It shows the test loss and the accuracy of the models in following rules R1 and R2, both in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD). The OOD setting violates rule R2, and the accuracy is measured in how well the models complete the sequences so that rule R1 still holds. The Transformer shows the best performance in extrapolating rule R1.

This table presents the results of evaluating the performance of five different sequence models (Linear, LSTM, Mamba, Transformer, and XLSTM) on a context-sensitive Dyck language (L6). The models were trained on sequences of paired parentheses and brackets where nesting is allowed. The table shows the test loss achieved by each model, along with their accuracy in following rules R1 (brackets are paired) and R2 (parentheses are paired) for both in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) prompts. OOD prompts violate rule R2, but still adhere to rule R1, allowing the assessment of rule extrapolation ability. The table shows that the Transformer and LSTM models perform best in extrapolating the rules.

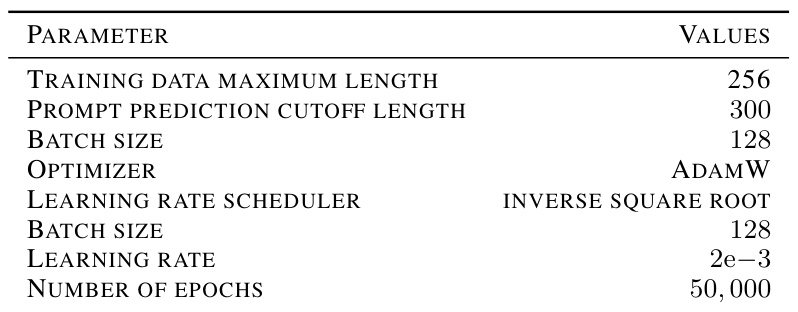

This table presents the hyperparameters used for training the different models in the experiments. It lists the values used for parameters such as the maximum length of training data, prompt prediction cutoff length, batch size, optimizer, learning rate scheduler, learning rate, and the number of epochs.

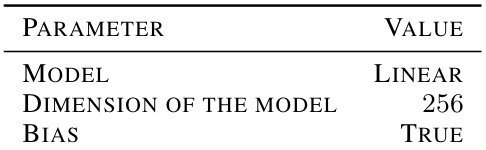

This table lists the hyperparameters used for the linear model in the experiments. It shows that a linear model was used, the dimension of the model was 256, and a bias term was included.

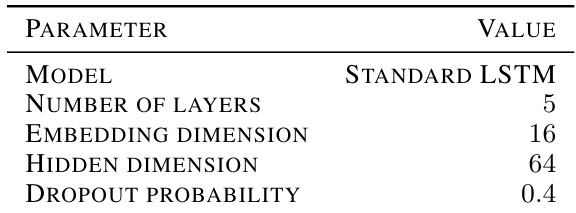

This table lists the hyperparameters used for the LSTM model in the experiments. It shows the model type as a standard LSTM, the number of layers (5), the embedding dimension (16), the hidden dimension (64), and the dropout probability (0.4). These settings were used to train and evaluate the LSTM’s performance on rule extrapolation tasks in formal languages.

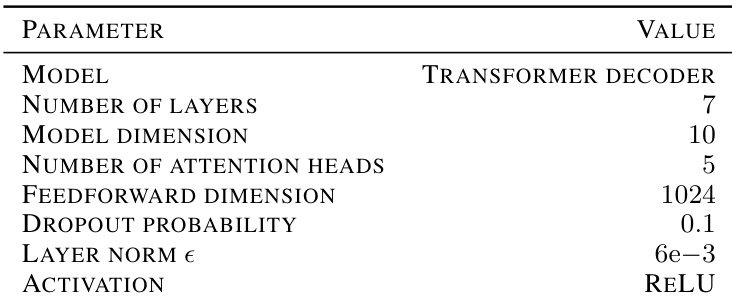

This table lists the hyperparameters used for the Transformer model in the experiments. It shows the model architecture, including the number of layers, the model dimension, the number of attention heads, the feedforward dimension, dropout probability, layer normalization epsilon, and the activation function used.

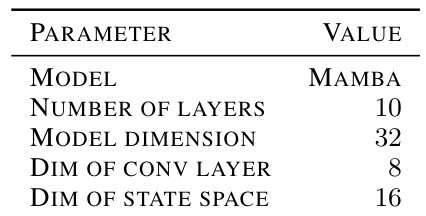

This table lists the hyperparameters used for the Mamba model in the experiments. It specifies the model architecture, including the number of layers, model dimension, dimension of the convolutional layer, and the dimension of the state space.

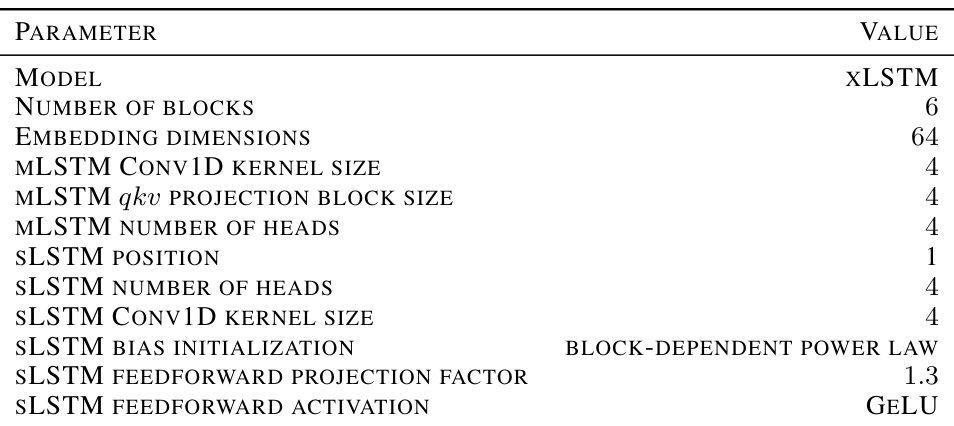

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the XLSTM model in the rule extrapolation experiments. It specifies the model architecture, including the number of blocks, embedding dimensions, and various parameters within the MLSTM and SLSTM components. These parameters control aspects like kernel sizes in convolutional layers, the number of attention heads, and activation functions.

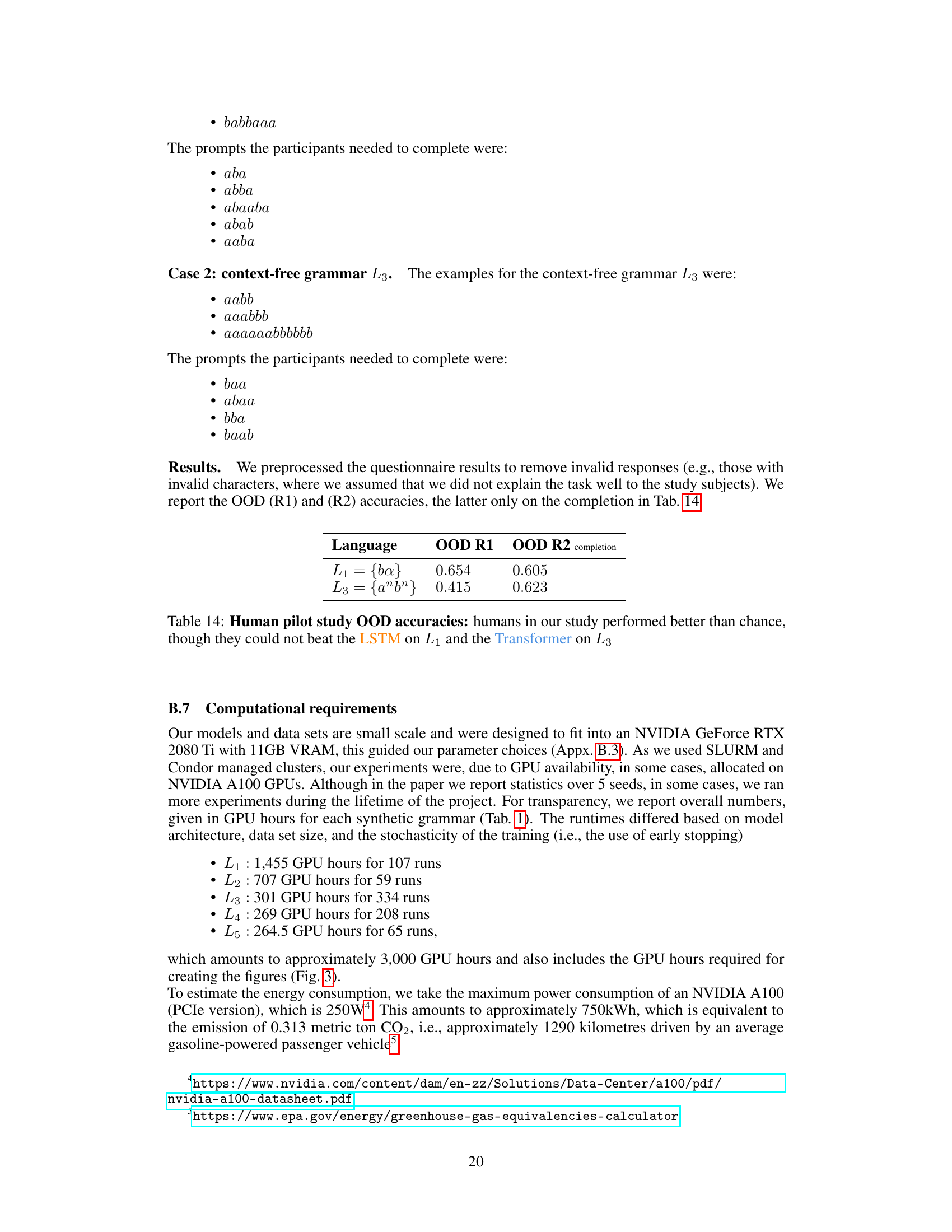

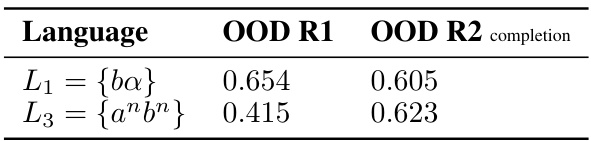

This table presents the results of a small-scale human study designed to evaluate human performance on out-of-distribution (OOD) rule extrapolation tasks, comparing human performance with the results obtained from the LSTM and the Transformer models in the main study. The study examined two formal languages, L1 and L3, each having two rules, and human subjects were tasked with extrapolating rule 1 (R1) and rule 2 (R2) in an OOD setting (i.e., when rule 2 was intentionally violated in the prompt). The table shows that human performance exceeded chance level on both languages, although it did not surpass the performance of the LSTM model on language L1 or the Transformer model on language L3.

Full paper#