↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Fine-tuning pre-trained language models is widely adopted but faces challenges in selecting optimal hyperparameters and checkpoints. Existing model fusion methods, like averaging model weights, often underperform, especially in NLP due to a large discrepancy between the loss and metric landscapes during fine-tuning. This makes finding models with good generalization difficult.

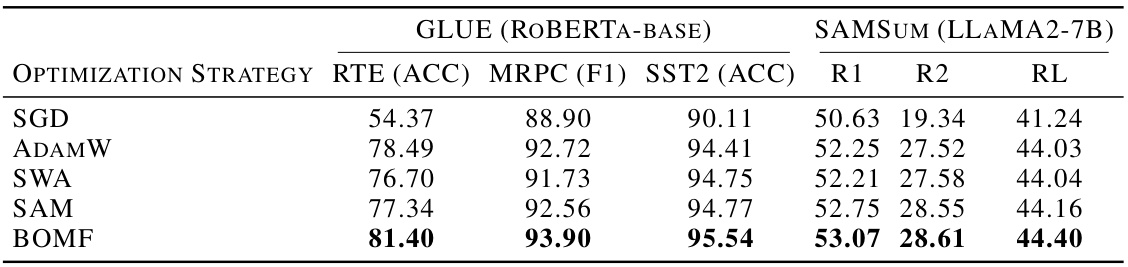

The paper introduces BOMF, a novel model fusion technique leveraging multi-objective Bayesian optimization. BOMF optimizes both the desired metric and loss, using a two-stage approach (hyperparameter optimization and model fusion optimization). Experiments demonstrate that BOMF significantly improves performance on various downstream tasks compared to existing methods. This makes it an efficient and effective tool for improving the fine-tuning process of language models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for NLP researchers due to its novel approach to model fusion using Bayesian optimization, addressing limitations of existing methods. It offers significant performance improvements across various downstream tasks and opens avenues for more efficient hyperparameter tuning and improved generalization in large language model fine-tuning.

Visual Insights#

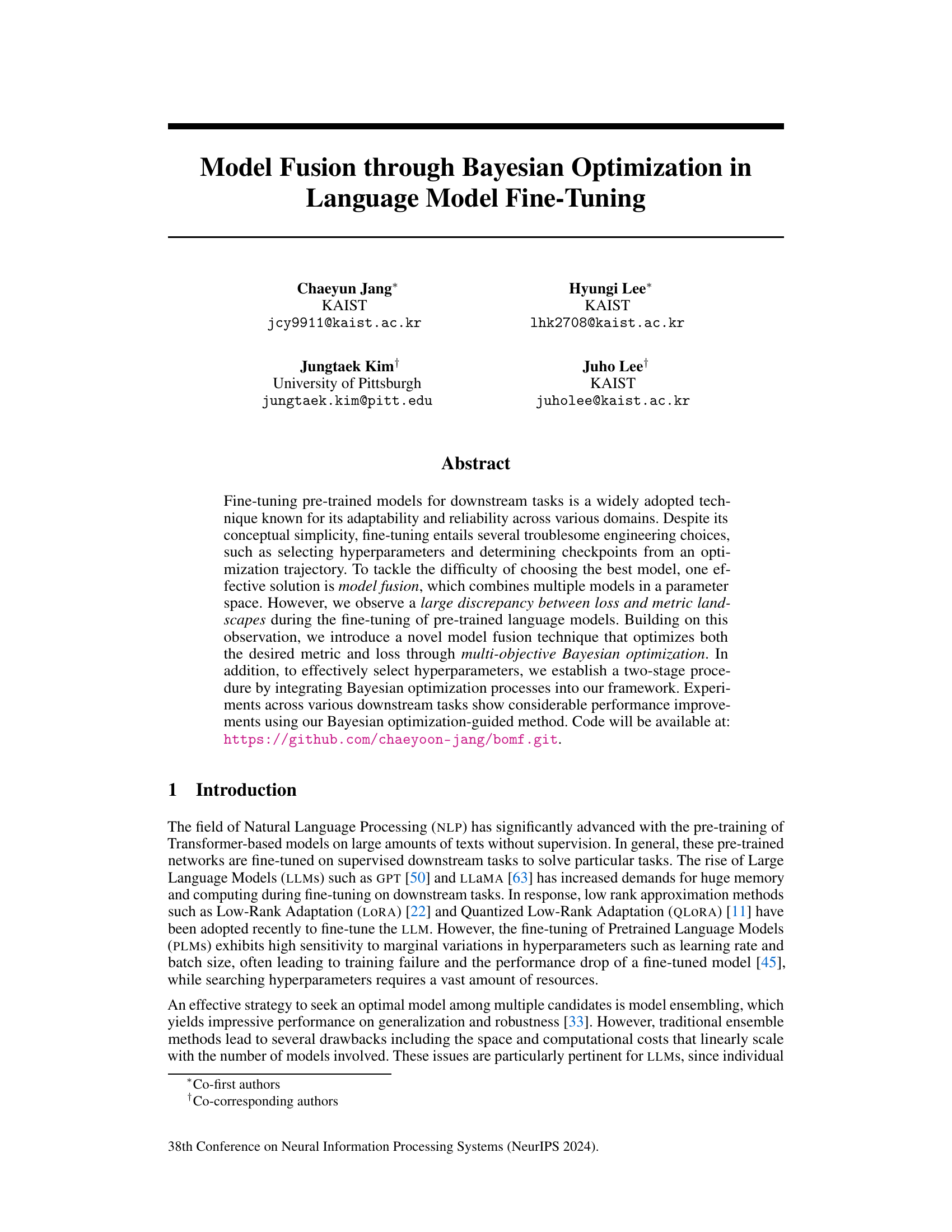

This figure visualizes the loss and metric landscapes for both computer vision and NLP tasks. The top row shows the results for a ResNet-50 model fine-tuned on the Caltech-101 dataset (a vision task), while the bottom row presents the results for a RoBERTa model fine-tuned on the MRPC dataset (an NLP task). The plots illustrate the discrepancy between loss and metric landscapes, highlighting the challenges of using simple averaging methods like SWA for model fusion in NLP.

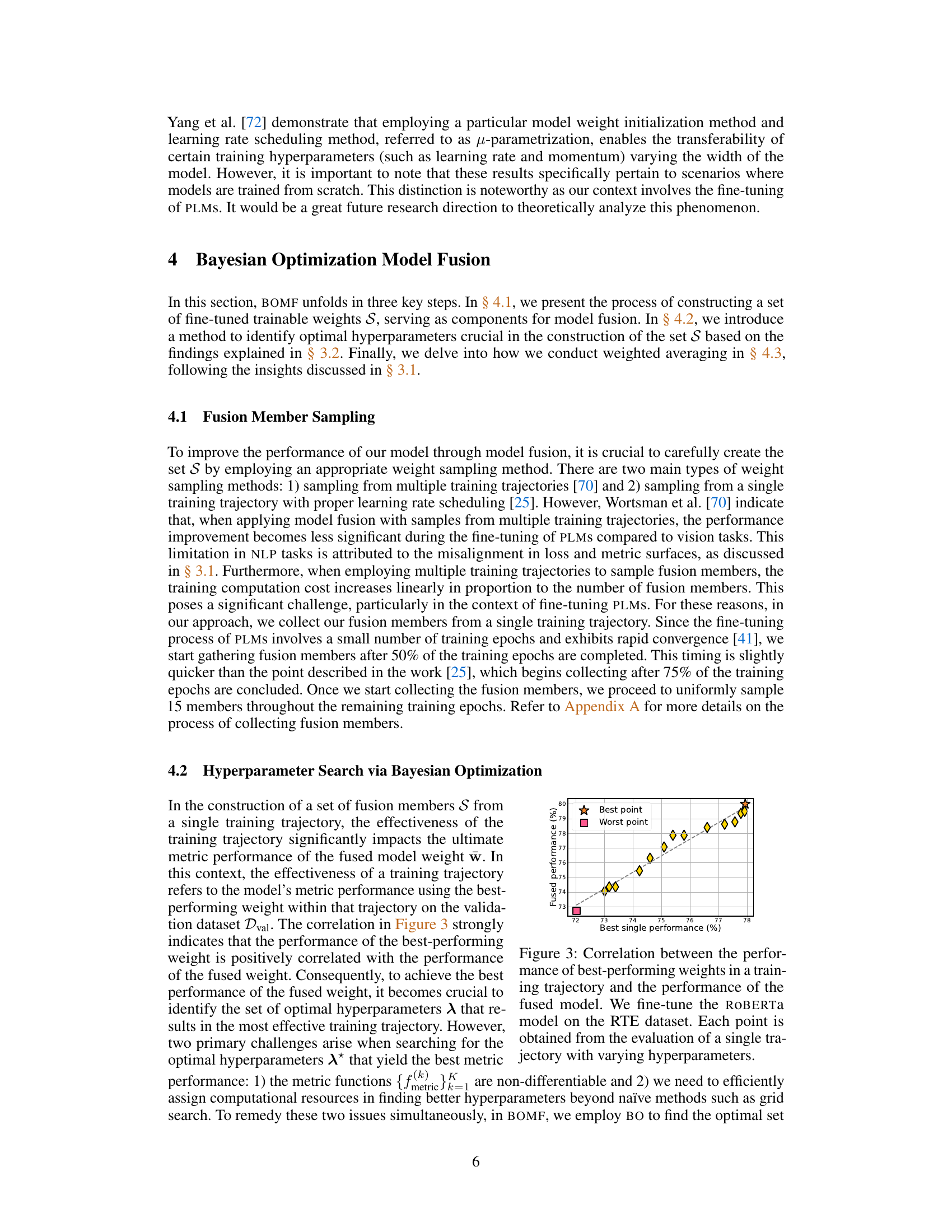

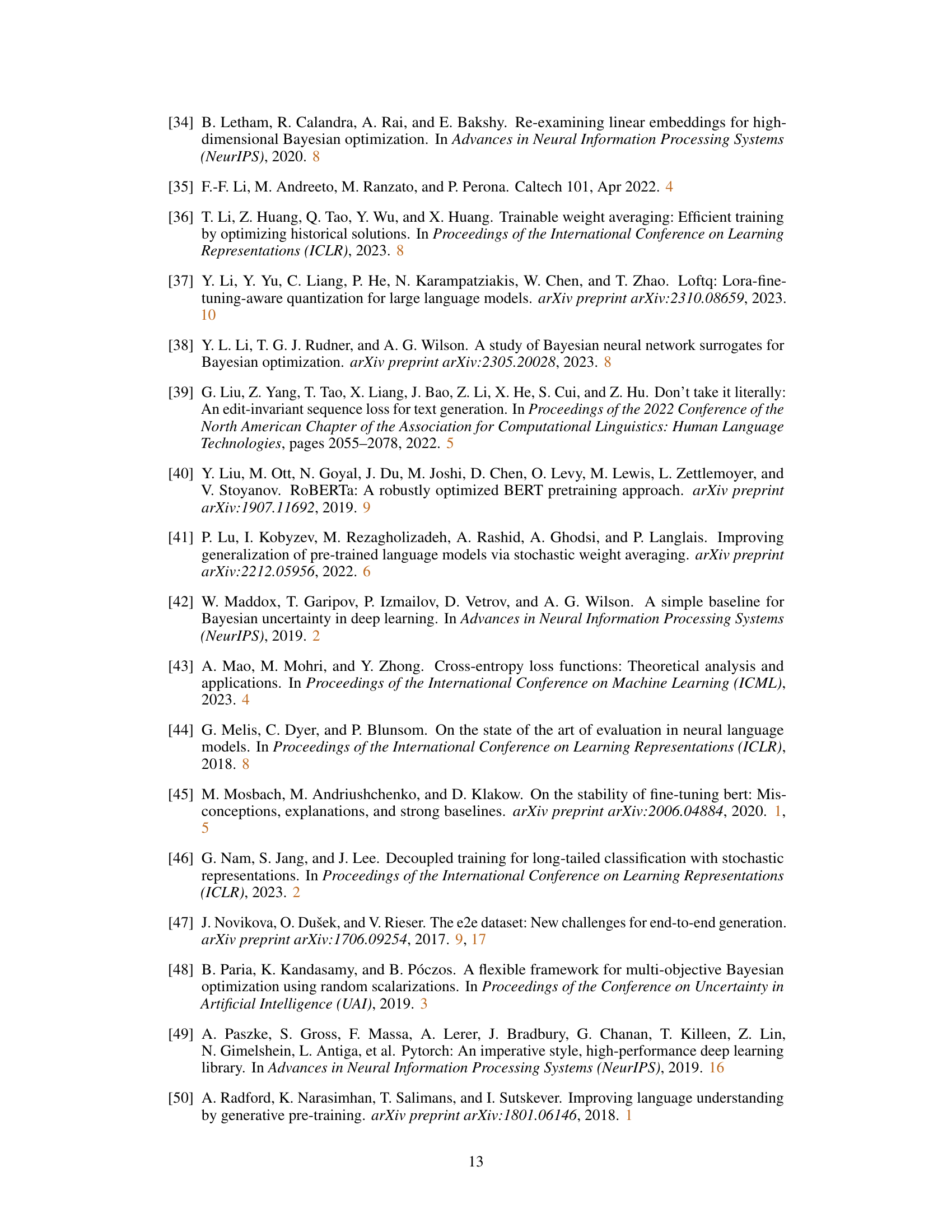

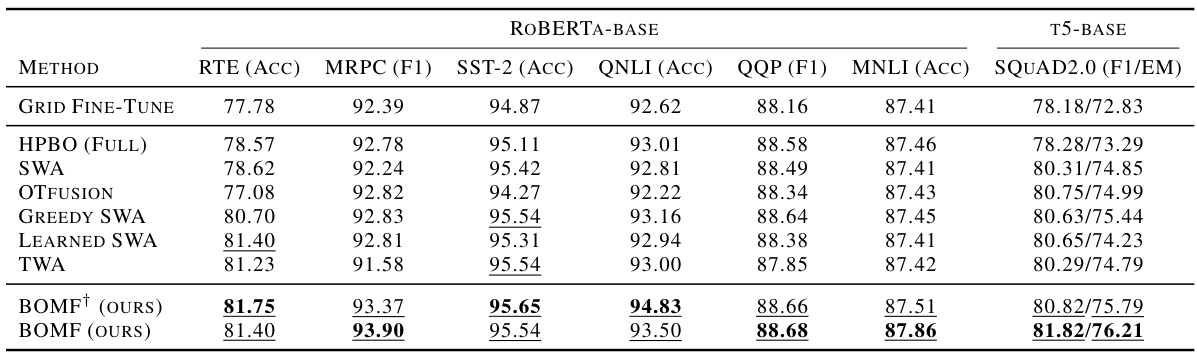

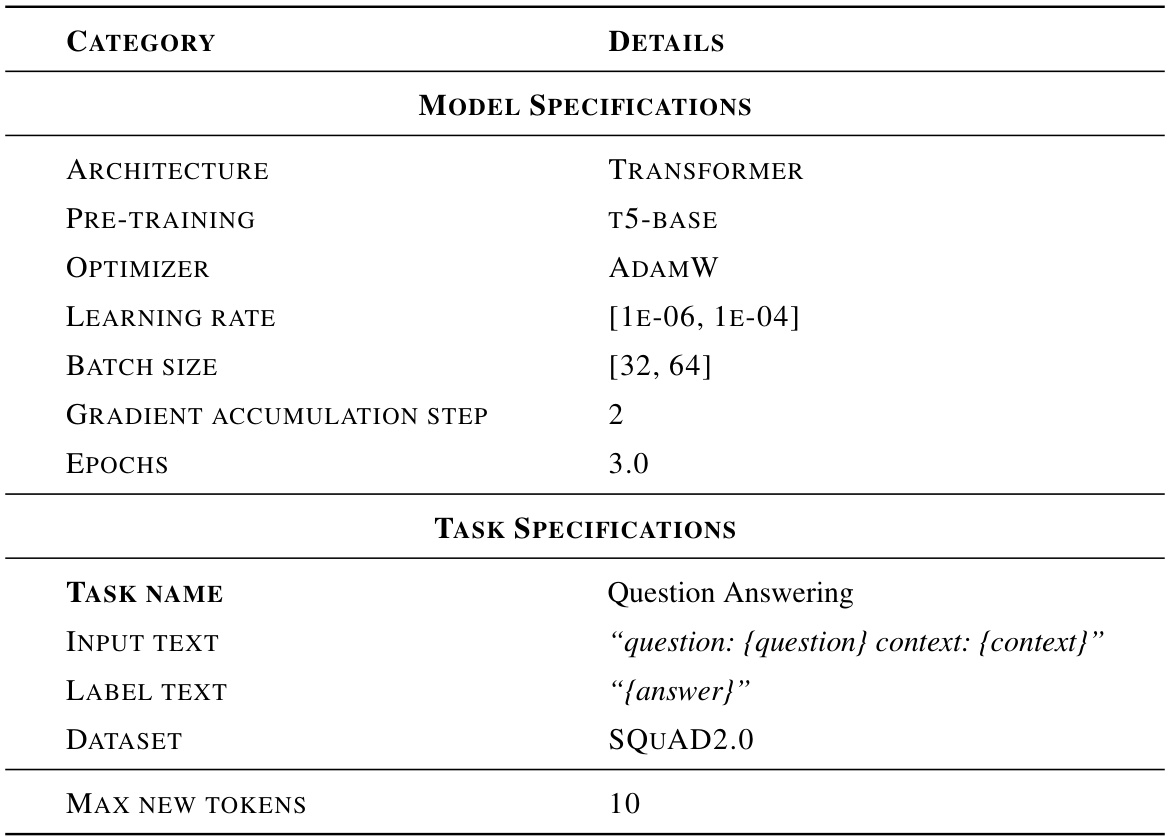

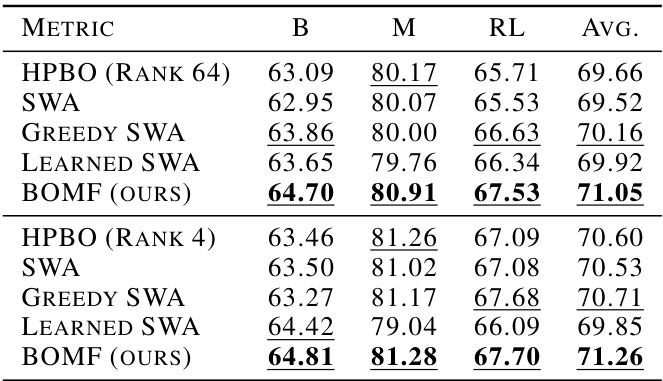

This table presents the results of different model fusion methods and baselines on two NLP tasks: text classification using ROBERTA-base and question answering using T5-base. The GLUE benchmark datasets are used for text classification, while the SQuAD2.0 dataset is used for question answering. Performance is measured using accuracy (ACC), F1 score (F1), and exact match (EM) as appropriate for each task. The table allows for comparison of various methods to enhance model fusion techniques.

In-depth insights#

Bayesian Optimization Fusion#

Bayesian Optimization Fusion represents a novel approach to model ensembling, particularly beneficial for large language models (LLMs). It addresses the challenges of traditional model fusion methods, such as Stochastic Weight Averaging (SWA), by incorporating Bayesian Optimization (BO) to efficiently find optimal weights, thereby outperforming simple averaging techniques. The method’s strength lies in its ability to handle non-differentiable metrics, common in natural language processing tasks, by employing multi-objective Bayesian optimization (MOBO) that considers both loss and evaluation metrics. This multi-objective approach mitigates the issue of misalignment between loss and metric landscapes often observed in LLMs. Furthermore, a two-stage optimization process enhances efficiency by first optimizing hyperparameters for fine-tuning and subsequently using BO for model fusion. This methodology demonstrates significant performance improvements across various downstream tasks, showcasing its effectiveness and scalability in improving the performance of LLMs.

Multi-Objective BO#

Multi-objective Bayesian Optimization (MOBO) addresses the challenge of optimizing multiple, often competing, objectives simultaneously. In the context of language model fine-tuning, MOBO is particularly valuable because the goals of minimizing loss and maximizing metrics (like accuracy or F1-score) may not align perfectly. Traditional single-objective optimization techniques often struggle to find optimal solutions that balance these competing needs. MOBO, on the other hand, seeks to identify the Pareto front—a set of solutions where improvement in one objective necessitates a trade-off in another. This approach allows for a more nuanced understanding of the optimization landscape and facilitates the selection of a solution that best suits the specific needs of the application. By considering both loss and metrics, MOBO can guide the fine-tuning process to models that generalize better and exhibit superior performance. Furthermore, MOBO’s sample efficiency makes it particularly suitable for scenarios with computationally expensive evaluation metrics, a common issue in large language model fine-tuning.

Loss-Metric Mismatch#

The concept of “Loss-Metric Mismatch” highlights a critical challenge in fine-tuning pre-trained language models (PLMs). Traditional approaches often rely on minimizing a loss function during training, assuming it correlates well with the desired evaluation metric. However, this assumption frequently breaks down in PLMs, leading to situations where a model with low training loss performs poorly on downstream tasks as measured by the target metric. This mismatch arises from the complex, high-dimensional nature of the PLM’s parameter space and the often non-linear relationship between the loss landscape and the metric landscape. Addressing this mismatch is crucial for effective fine-tuning, requiring methods that explicitly consider both loss and metrics during optimization, rather than simply focusing on loss minimization. This mismatch necessitates the development of novel optimization strategies that can navigate the intricacies of the PLM’s loss and metric surfaces to find models that generalize well and achieve high performance on the downstream task. Multi-objective optimization techniques are particularly relevant in this context as they allow for the simultaneous optimization of multiple conflicting objectives, such as loss and various evaluation metrics.

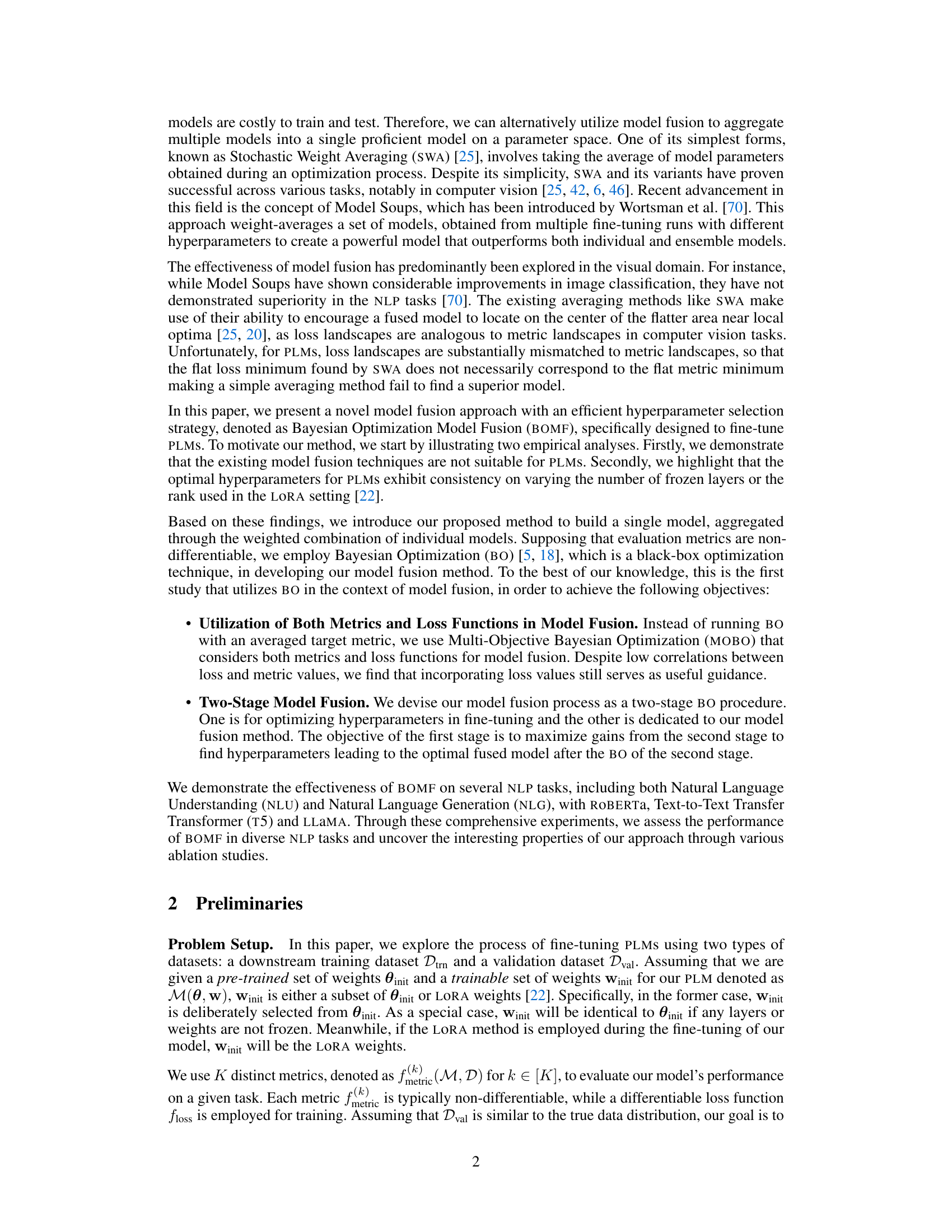

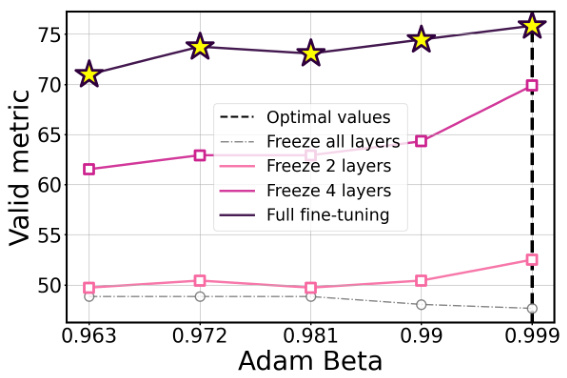

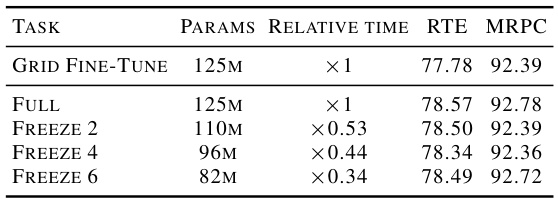

Hyperparameter Alignment#

The concept of “Hyperparameter Alignment” in the context of large language model (LLM) fine-tuning is crucial. The authors reveal a surprising finding: optimal hyperparameters exhibit consistency across various model configurations, even when altering the number of frozen layers or the rank in LORA (Low-Rank Adaptation). This alignment implies that hyperparameter searches can be significantly streamlined, potentially using smaller, computationally cheaper models to identify optimal settings applicable to larger LLMs. This significantly reduces the computational cost associated with hyperparameter optimization, a critical factor when working with the substantial computational demands of LLMs. The consistency observed across various architectural modifications highlights the inherent robustness of the optimal hyperparameter ranges within the model’s architecture, a property that could facilitate the transferability and reusability of hyperparameter tuning insights across different LLM models and tasks. This discovery is a significant contribution to efficient LLM fine-tuning and deserves further investigation to fully understand the underlying reasons and applicability.

Future Work: LORA#

Future research involving LORA (Low-Rank Adaptation) in the context of large language model fine-tuning could explore several promising avenues. Investigating the interplay between LORA’s rank and the effectiveness of model fusion techniques is crucial; lower ranks offer efficiency but might sacrifice the benefits of fusion. A thorough comparison of LORA with other low-rank approximation methods in the fine-tuning process is necessary to understand their relative strengths and weaknesses regarding model performance and resource utilization. Developing more sophisticated methods for selecting optimal LORA hyperparameters (rank, learning rate, etc.) is essential. The current study suggests a correlation but further research could lead to more efficient search strategies. Finally, extending the methodology to handle quantized LORA models would significantly improve efficiency for deploying these enhanced models on resource-constrained devices.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure visualizes the loss and metric landscapes for both computer vision and NLP tasks. The top row shows ResNet-50 on Caltech-101, with (a) showing the loss landscape and (b) showing the metric (1-accuracy and F1-score). The bottom row shows the same for ROBERTA on MRPC, again with (c) showing the loss and (d) showing the metric. The visualization helps illustrate the difference in landscape characteristics between vision and NLP tasks and is used to motivate the need for a new model fusion technique.

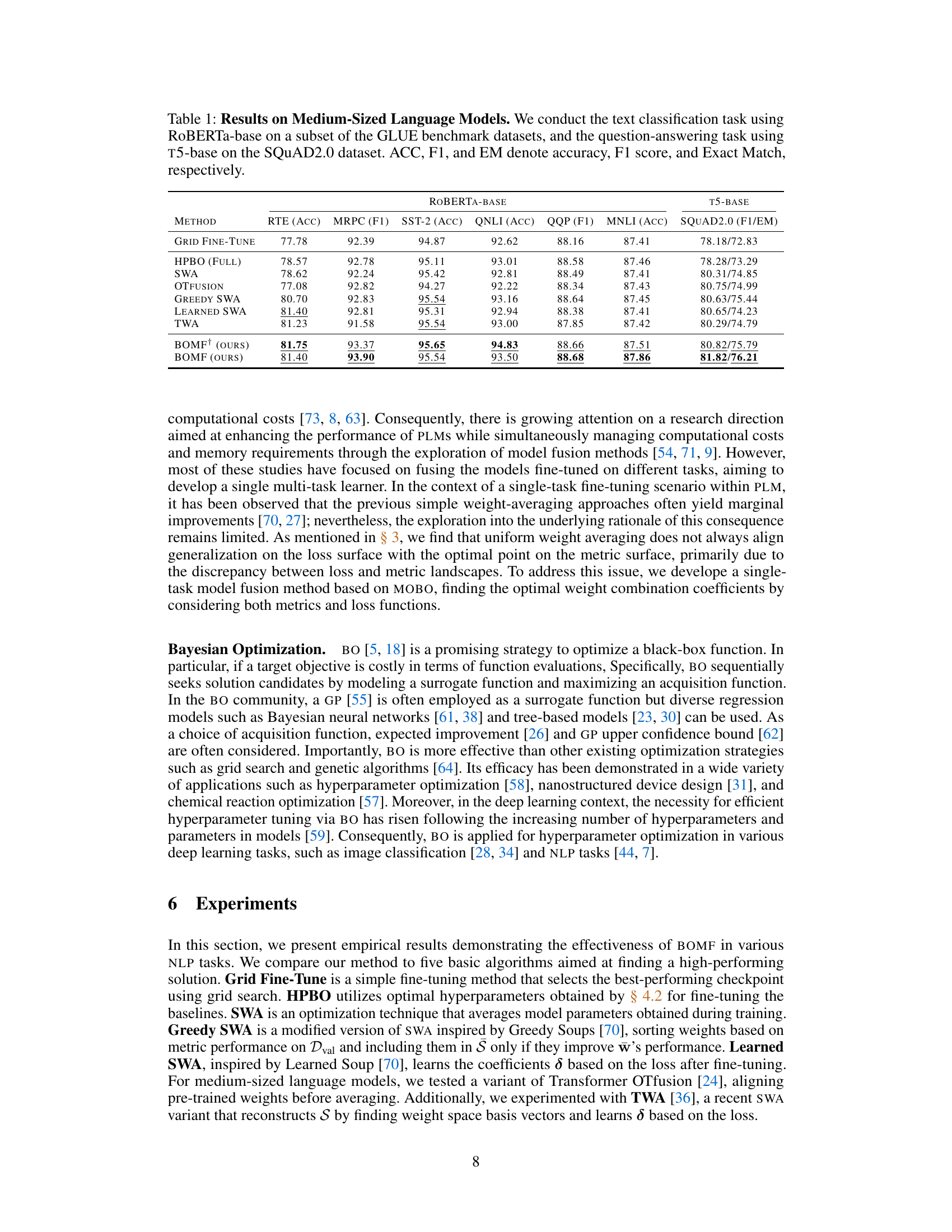

This figure shows the correlation between the best single model performance within a training trajectory and the final fused model performance after applying the BOMF method. Each point represents a different fine-tuning run with varying hyperparameters. The positive correlation indicates that using better performing training trajectories leads to better fused models.

This figure visualizes the loss and metric landscapes for both computer vision and NLP tasks. It highlights the significant difference between the loss and metric landscapes in NLP, showing a lack of alignment between loss minima and optimal metric values. The visualization uses ResNet-50 and ROBERTA models, with the metric representing accuracy (vision) and F1 score (NLP). The figure demonstrates a key finding of the paper: the mismatch of loss and metric landscapes makes simple averaging methods less effective for NLP fine-tuning.

This figure visualizes the loss and metric landscapes for both computer vision and NLP tasks. It shows the discrepancy between the loss and metric surfaces for NLP models, which motivates the use of a multi-objective Bayesian optimization approach in the paper.

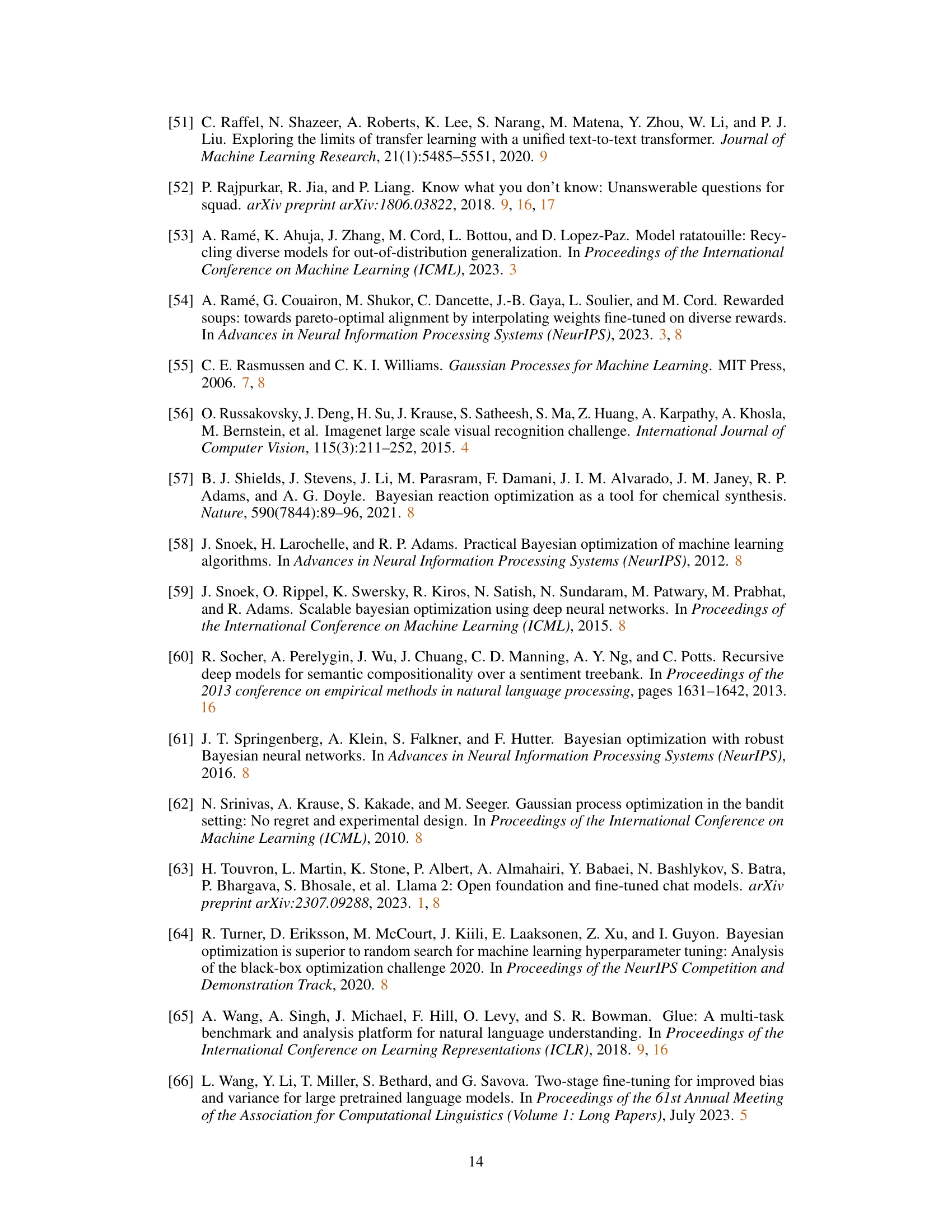

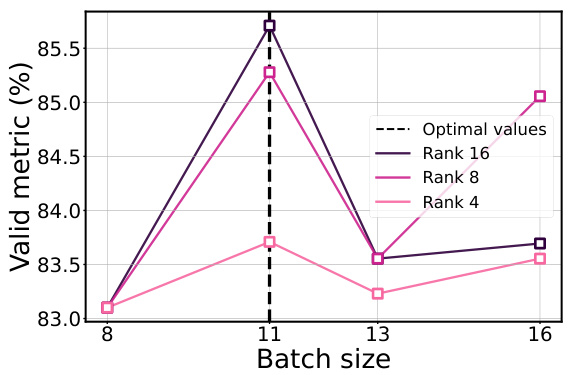

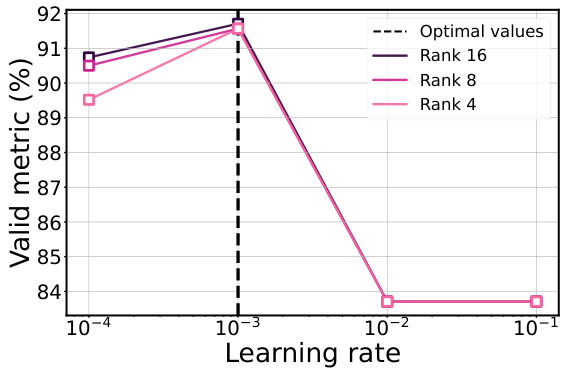

This figure visualizes the validation loss and F1 score for different hyperparameters (batch size and learning rate) across various LORA ranks in a fine-tuning experiment using the ROBERTa model on the MRPC dataset. The plots demonstrate that the optimal hyperparameters remain consistent regardless of the LORA rank used, highlighting the robustness and efficiency of the proposed method.

This figure shows the validation loss and F1 score for different hyperparameter settings (batch size and learning rate) and varying numbers of LORA rank during the fine-tuning of a ROBERTa model on the MRPC dataset. The plots demonstrate that the optimal hyperparameters remain consistent across different LORA ranks, suggesting a potential for efficient hyperparameter tuning using smaller models.

This figure displays the validation loss and F1 score for different hyperparameters (batch size and learning rate) and LORA ranks while fine-tuning a ROBERTa model on the MRPC dataset. The plots show a consistent alignment of optimal hyperparameters across various LORA ranks, suggesting that optimizing on a smaller model with fewer parameters can effectively transfer to larger models.

This figure presents the results of an experiment on the MRPC dataset using the ROBERTa model. The experiment explores the effects of varying three hyperparameters (learning rate, batch size, and the number of frozen layers) on both the validation loss and the F1 score. The plots show that the optimal hyperparameter values for achieving the best F1 score remain relatively consistent across different numbers of frozen layers. However, when all pre-trained layers are frozen, the optimal hyperparameters differ significantly.

This figure shows the validation loss and F1 score for different hyperparameters (batch size and learning rate) while varying the rank of the LORA (Low-Rank Adaptation) method during fine-tuning of the RoBERTa model on the MRPC dataset. The results demonstrate that the optimal hyperparameters remain largely consistent across different LORA ranks, suggesting that hyperparameter tuning might be performed on a smaller model with a lower LORA rank, potentially reducing computational cost.

This figure displays the validation loss and F1 score for different hyperparameter settings (batch size and learning rate) across varying LORA ranks while fine-tuning the ROBERTa model on the MRPC dataset. The results show that optimal hyperparameters remain consistent across different LORA ranks, suggesting potential computational savings by using lower-rank models during hyperparameter optimization.

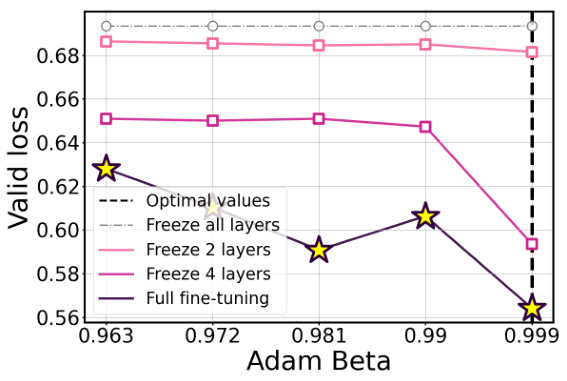

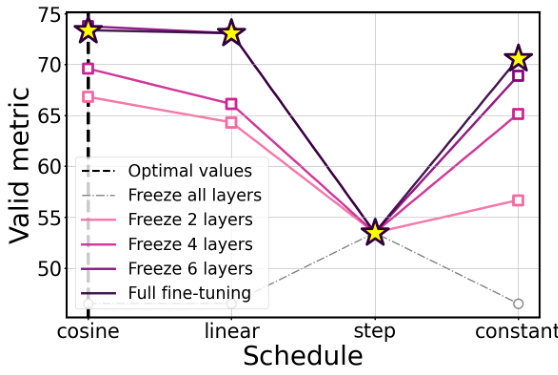

This figure visualizes the validation metric (accuracy) and loss for different learning rate schedules (cosine, linear, step, constant) and varying numbers of frozen layers (all, 2, 4, 6) during fine-tuning of the ROBERTa-base model on the RTE dataset. The consistent alignment of optimal hyperparameters across different numbers of frozen layers highlights their importance for achieving optimal performance. The results show that the choice of learning rate schedule significantly impacts performance, even with varying numbers of frozen layers.

The figure shows the validation loss and metric (accuracy) for the ROBERTa-base model on the RTE dataset, varying the learning rate schedule (cosine, linear, step, constant) and the number of frozen layers (all, 6, 4, 2, none). The key takeaway is that the optimal hyperparameters are largely consistent, even when different numbers of layers are frozen, highlighting the importance of proper hyperparameter tuning.

This figure visualizes the loss and metric landscapes for both computer vision (ResNet-50 on Caltech-101) and NLP (RoBERTa on MRPC) tasks. It shows a clear difference in the alignment between loss and metric landscapes between the two domains. In computer vision, there is a strong correlation, whereas in NLP, there is a significant mismatch. This difference motivates the use of multi-objective Bayesian optimization in the proposed method.

This figure visualizes the loss and metric landscapes for both computer vision and NLP tasks. It shows how the loss and metric surfaces differ between the two domains, highlighting the mismatch between loss and metric landscapes in NLP, which motivates the use of multi-objective optimization in the BOMF approach.

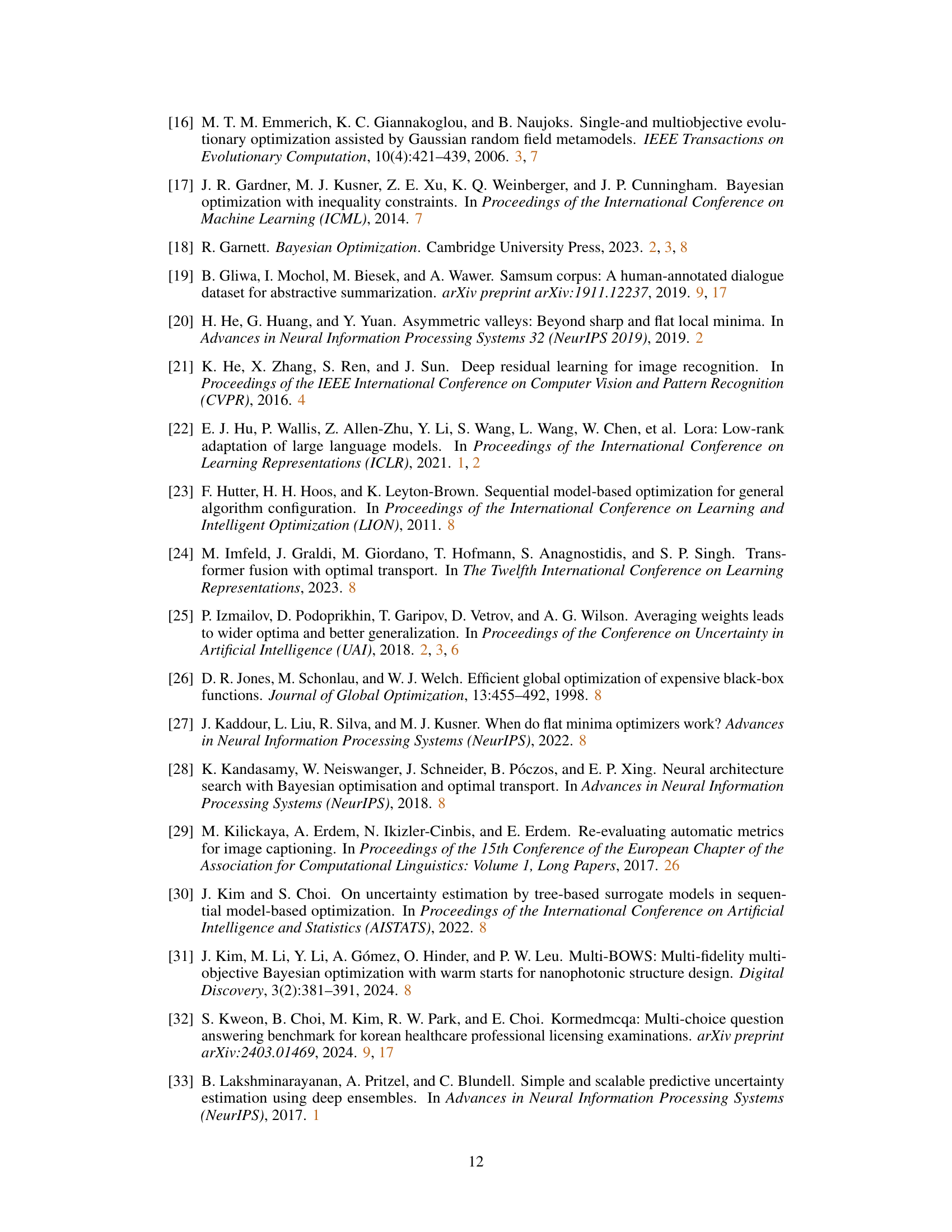

More on tables

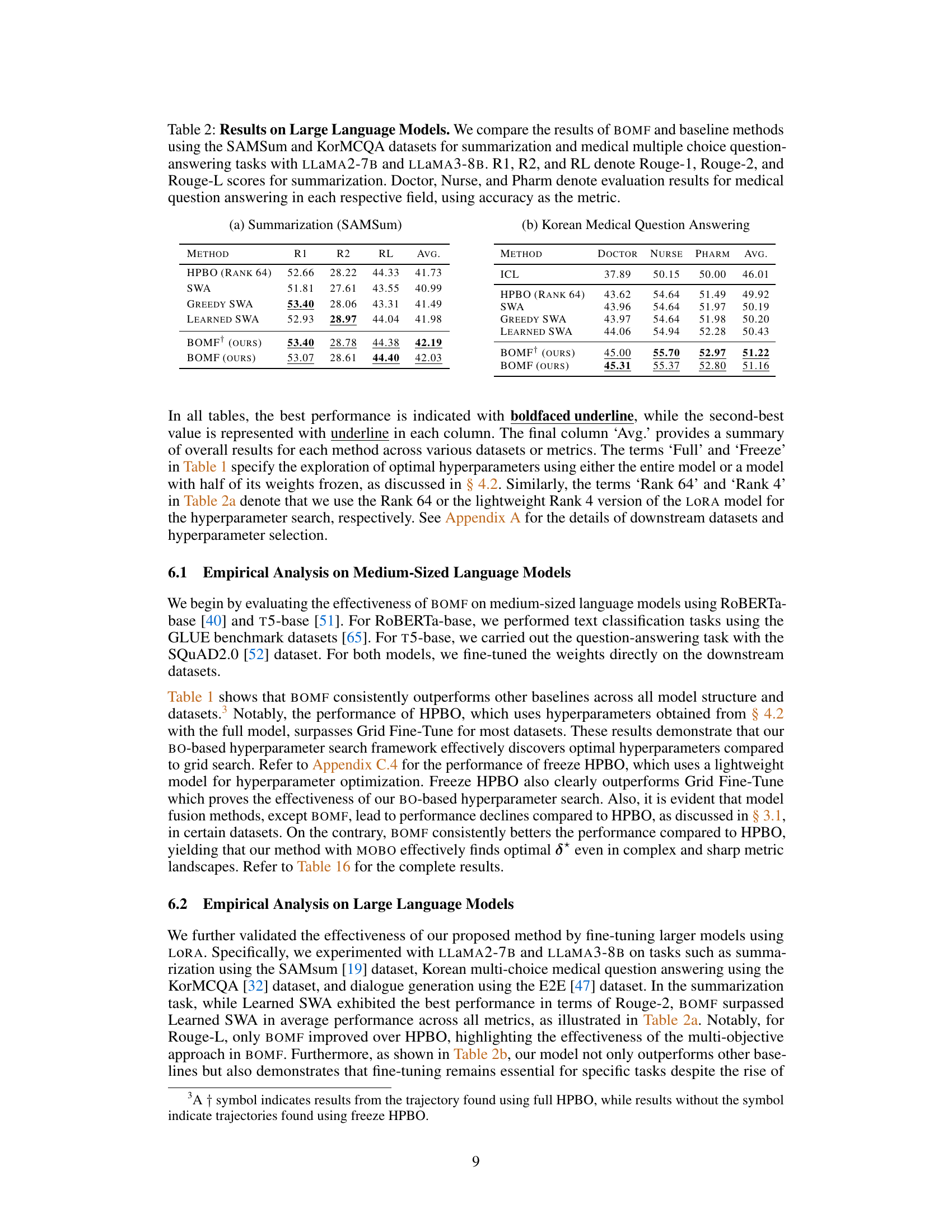

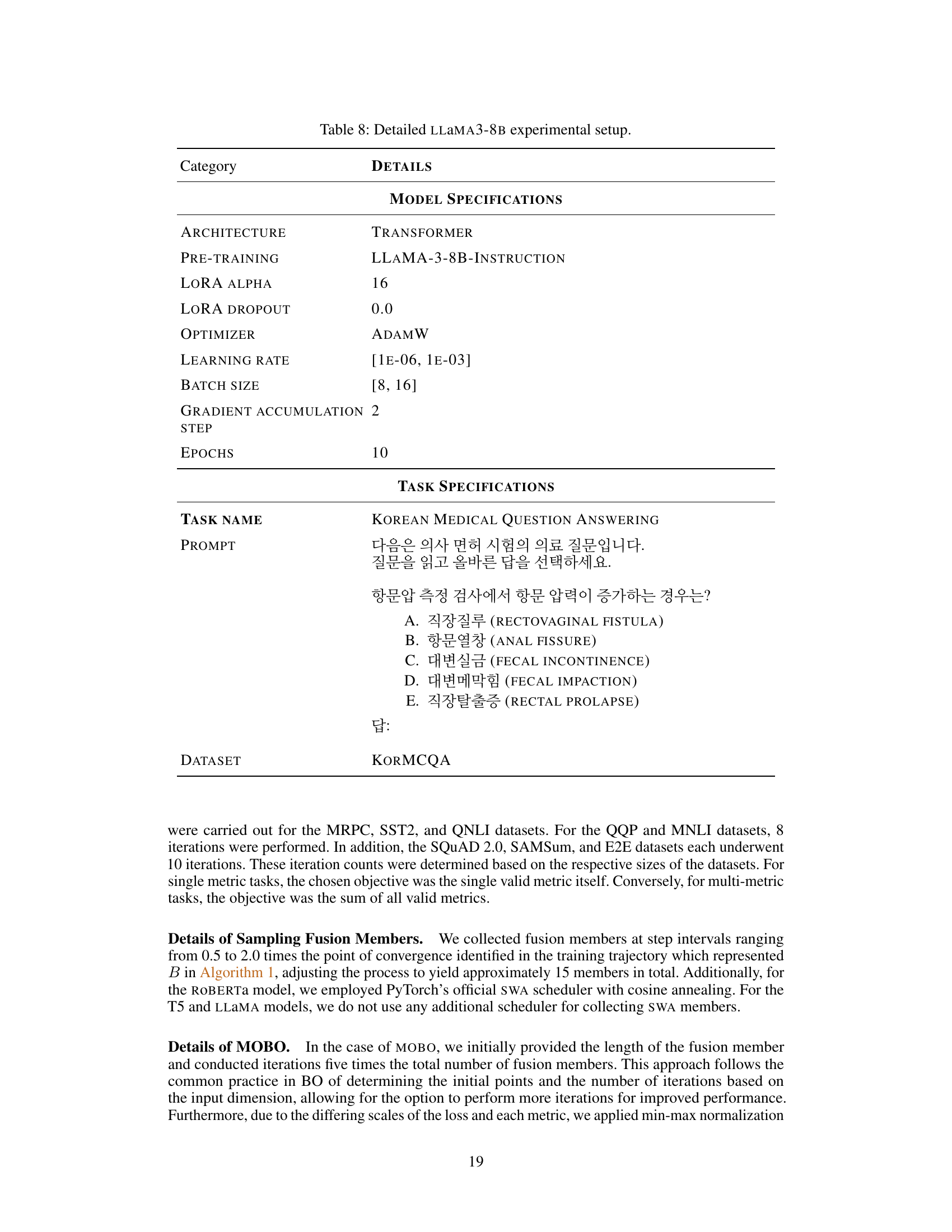

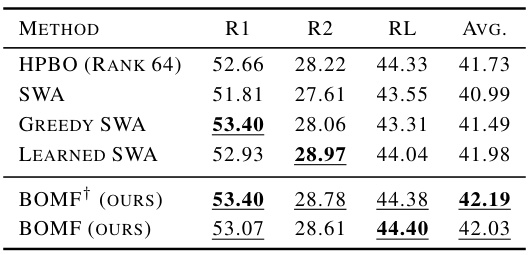

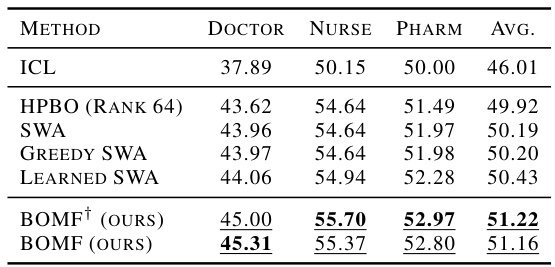

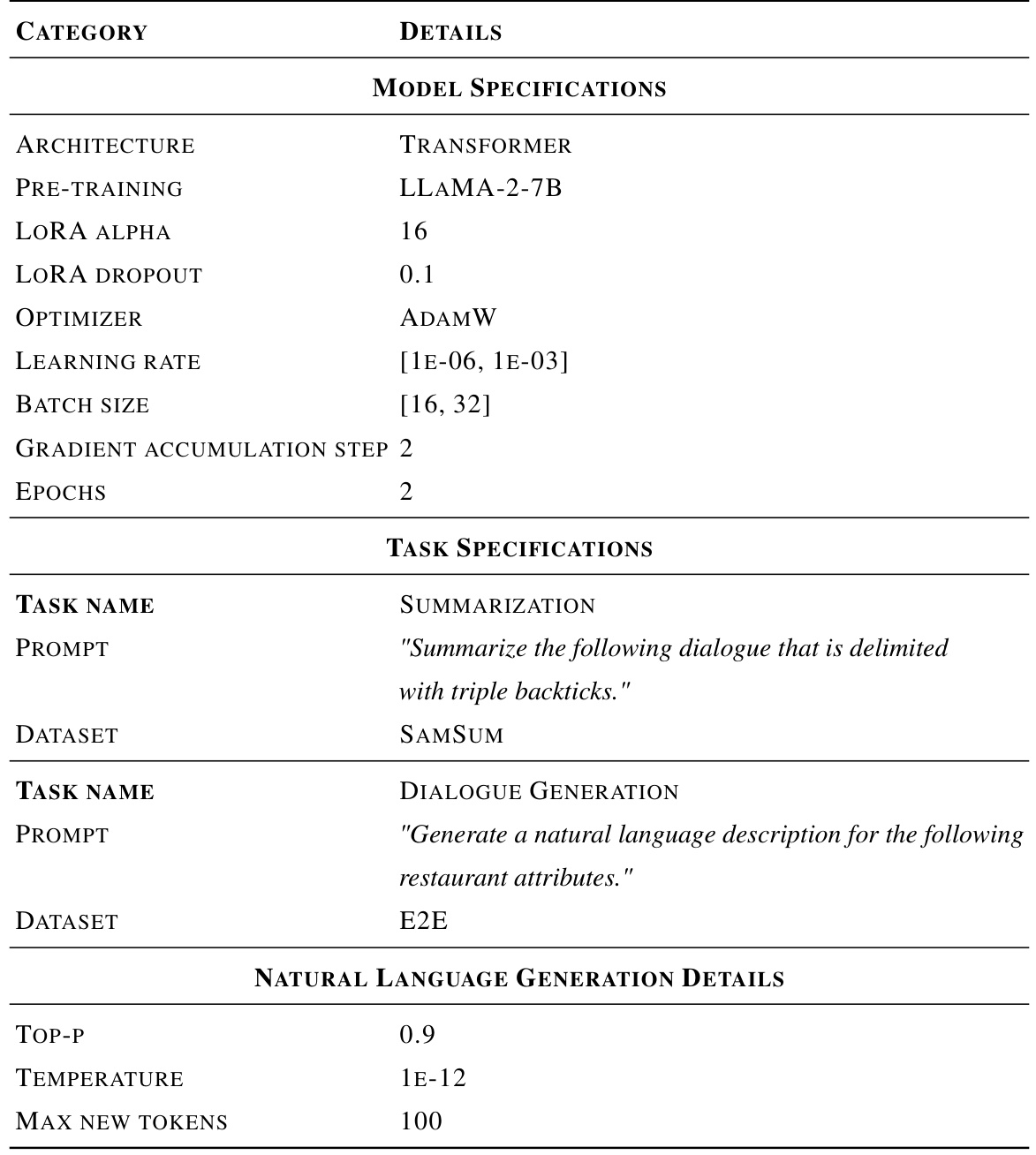

This table compares the performance of BOMF against several baseline methods on two tasks using large language models: summarization (SAMSum dataset) and Korean medical multiple choice question answering (KorMCQA dataset). For summarization, Rouge scores (R1, R2, RL) are reported. For the question-answering task, accuracy is reported for three different professions (doctor, nurse, pharmacist). The results are shown for two different large language models: LLAMA2-7B and LLAMA3-8B.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of BOMF and several baseline methods on two tasks using large language models: summarization (SAMSum dataset) and medical multiple-choice question answering (KorMCQA dataset). The models used are LLAMA2-7B and LLAMA3-8B. For summarization, performance is measured using Rouge-1, Rouge-2, and Rouge-L scores. For the medical question answering task, accuracy is reported for three categories: Doctor, Nurse, and Pharmacist. The table helps assess BOMF’s effectiveness compared to established methods in these specific contexts.

This table presents the results of different model fusion techniques and baselines on two NLP tasks: text classification using the RoBERTa-base model and question answering using the T5-base model. The GLUE benchmark datasets are used for text classification, and the SQuAD2.0 dataset is used for question answering. The table shows performance metrics for each method across various datasets, including accuracy (ACC), F1 score (F1), and Exact Match (EM).

This table compares the performance of different model fusion techniques and fine-tuning methods on medium-sized language models (RoBERTa-base and T5-base) for text classification and question answering tasks. It shows the accuracy (ACC), F1 score (F1), and exact match (EM) for each method across different datasets. The results highlight the effectiveness of the proposed BOMF (Bayesian Optimization Model Fusion) method compared to several baselines.

This table compares the performance of different model fusion methods (BOMF and baselines) on medium-sized language models (ROBERTa-base and T5-base). The models were fine-tuned on text classification tasks from the GLUE benchmark and a question answering task from SQuAD2.0. The table shows the accuracy (ACC), F1 score, and Exact Match (EM) for each model and dataset. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of BOMF in improving model performance.

This table compares the performance of different model fusion methods (BOMF and baselines) on two medium-sized language models: RoBERTa-base and T5-base. The models were fine-tuned on various text classification tasks from the GLUE benchmark and a question answering task using the SQuAD2.0 dataset. The table reports accuracy (ACC), F1 score, and exact match (EM) for each method across multiple datasets. This provides a quantitative assessment of the proposed BOMF method against well-established baselines.

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on medium-sized language models (ROBERTa-base and T5-base) for text classification and question answering tasks. It compares the performance of BOMF (the proposed method) against several baseline methods across various datasets (a subset of GLUE and SQuAD2.0). The results are reported using accuracy (ACC), F1-score (F1), and Exact Match (EM) as evaluation metrics, providing a comprehensive comparison of the model’s performance on different tasks.

This table presents the results of different model fusion methods and baselines on medium-sized language models (RoBERTa-base and T5-base) for text classification (using a subset of GLUE benchmark datasets) and question answering (using the SQuAD2.0 dataset). It compares the performance of BOMF (the proposed method) against several baseline methods like Grid Fine-Tuning, HPBO, SWA, OTfusion, Greedy SWA, Learned SWA, and TWA. The evaluation metrics used are Accuracy (ACC), F1 score (F1), and Exact Match (EM).

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on medium-sized language models (RoBERTa-base and T5-base). It compares the performance of the proposed BOMF method against several baseline methods across various text classification (using GLUE benchmark datasets) and question answering (using SQuAD2.0) tasks. The results are reported in terms of accuracy (ACC), F1 score (F1), and exact match (EM) metrics, providing a comprehensive performance comparison.

This table presents the results of different model fusion and fine-tuning methods on medium-sized language models (ROBERTa-base and T5-base). It compares the performance of BOMF against several baseline methods across multiple text classification and question-answering tasks, using standard evaluation metrics (accuracy, F1 score, exact match). The results highlight the effectiveness of BOMF in achieving state-of-the-art results on these tasks.

This table shows the Spearman’s rank correlation between loss and metrics (R1, R2, RL) for different optimization strategies on the SAMSum dataset using the LLAMA2-7B model. It compares the baseline (HPBO), using only loss for optimization; Loss BO SWA, using only loss in the MOBO process; Metric BO SWA, only using metrics in the MOBO process; and BOMF, using both loss and metrics. The results highlight the impact of incorporating multiple objectives into the optimization process.

This table presents the performance comparison of different optimization strategies (including the proposed BOMF) on two medium-sized language models: ROBERTa-base for text classification tasks using the GLUE benchmark, and T5-base for question answering using the SQuAD2.0 dataset. The results are shown for various metrics: accuracy (ACC), F1 score (F1), and exact match (EM).

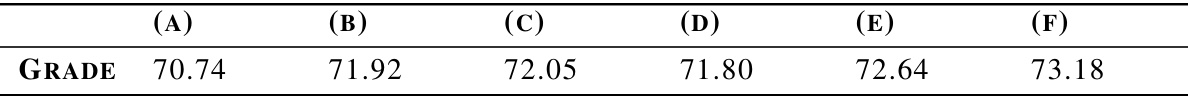

This table compares the performance of different model fusion methods, including BOMF, using a ChatGPT-based evaluation approach. The evaluation involves a human-like grading task of the similarity between student-submitted answers and the ground truth, providing a numerical score for each model.

This table presents the results of the text classification task using the RoBERTa-base model on a subset of the GLUE benchmark datasets and the question-answering task using the T5-base model on the SQuAD2.0 dataset. It compares the performance of the BOMF method to several baseline methods (Grid Fine-Tune, HPBO (Full), SWA, OTFUSION, Greedy SWA, Learned SWA, TWA) across different metrics (accuracy, F1 score, exact match). The results show the effectiveness of BOMF compared to other baselines.

This table compares the performance of different model fusion techniques (BOMF and baselines) on two NLP tasks: text classification using ROBERTa-base and question answering using T5-base. It shows the accuracy (ACC), F1 score (F1), and Exact Match (EM) for each method across various datasets. The results highlight the improved performance of the proposed BOMF method.

This table presents the performance comparison of different model fusion methods and baselines on two medium-sized language models: ROBERTA-base for text classification (using GLUE benchmark datasets), and T5-base for question answering (using SQuAD2.0 dataset). The results show accuracy (ACC), F1-score (F1), and Exact Match (EM) for each method and dataset. It helps to evaluate the effectiveness of various model fusion strategies in improving the performance of pre-trained language models on downstream NLP tasks.

This table presents the results of the proposed BOMF method and several baseline methods on two medium-sized language models: RoBERTa-base for text classification on the GLUE benchmark and T5-base for question answering on SQuAD2.0. The table compares the performance across different datasets using metrics like accuracy (ACC), F1 score (F1), and Exact Match (EM).

Full paper#