↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) typically predict forward in time; however, recent works suggest that enabling LLMs to critique their own generations can be beneficial. This paper introduces Time Reversed Language Models (TRLMs) that function in the reverse direction of time, scoring and generating queries given responses. This approach aims to provide unsupervised feedback, reducing reliance on expensive human-labeled data and addressing inherent limitations in forward-only LLM training.

The researchers pre-train and fine-tune a TRLM (TRLM-Ba) in reverse token order, scoring responses given queries. Experiments demonstrate that TRLM scoring complements forward predictions, boosting performance on several benchmarks including AlpacaEval (up to 5% improvement). The study further shows the effectiveness of TRLMs for citation generation, passage retrieval, and augmenting safety filters. Using TRLM-generated queries based on responses reduced false negatives in safety filtering with negligible impact on false positives, addressing a critical issue in LLM safety.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel approach to improving LLMs by using unsupervised feedback from time-reversed language models. This offers a cost-effective alternative to traditional methods like RLHF, reducing the reliance on expensive human feedback. The findings also have implications for improving safety filters and enhancing the performance of LLMs on various downstream tasks, opening up new avenues for research in LLM alignment and safety.

Visual Insights#

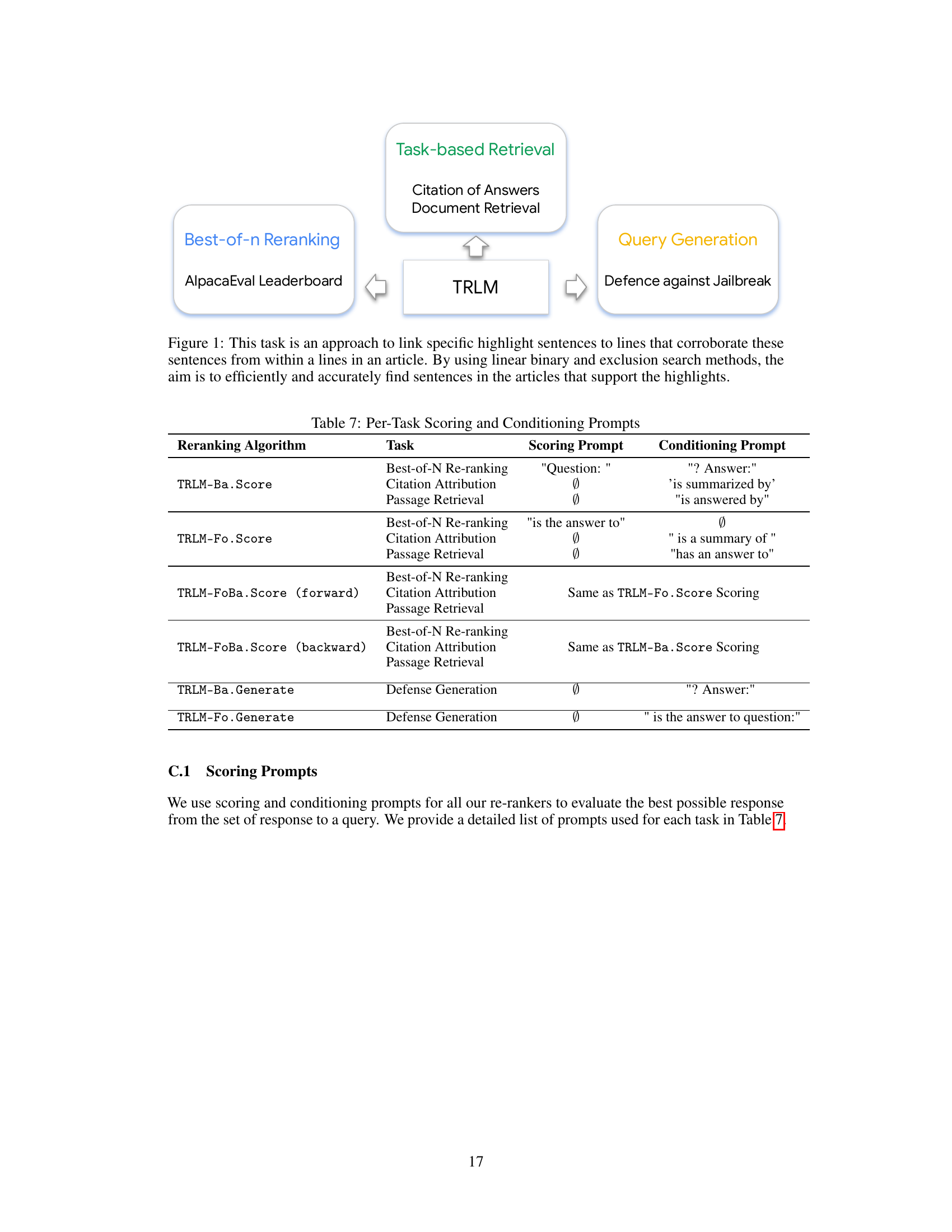

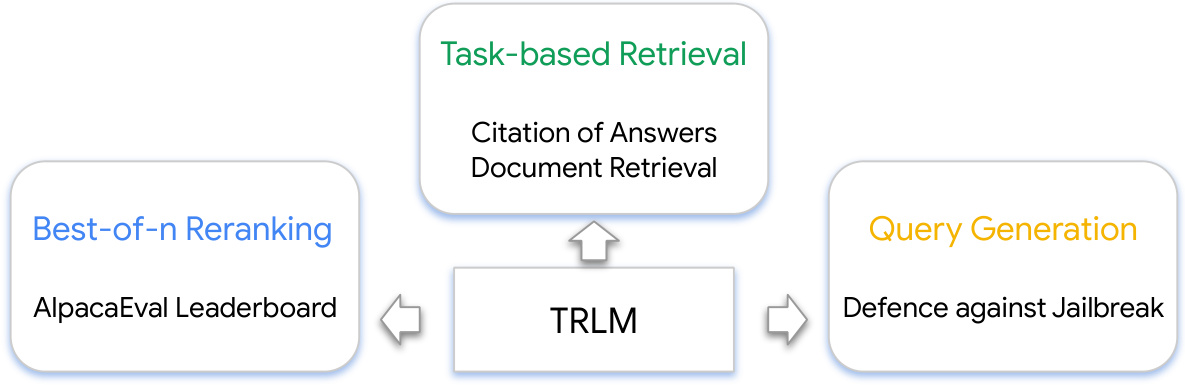

This figure shows the three main tasks that the paper addresses using TRLMs. The first task is best-of-N reranking, evaluated using the AlpacaEval leaderboard. The second task is task-based retrieval which consists of citation of answers and document retrieval. The third task is query generation for defense against jailbreaks.

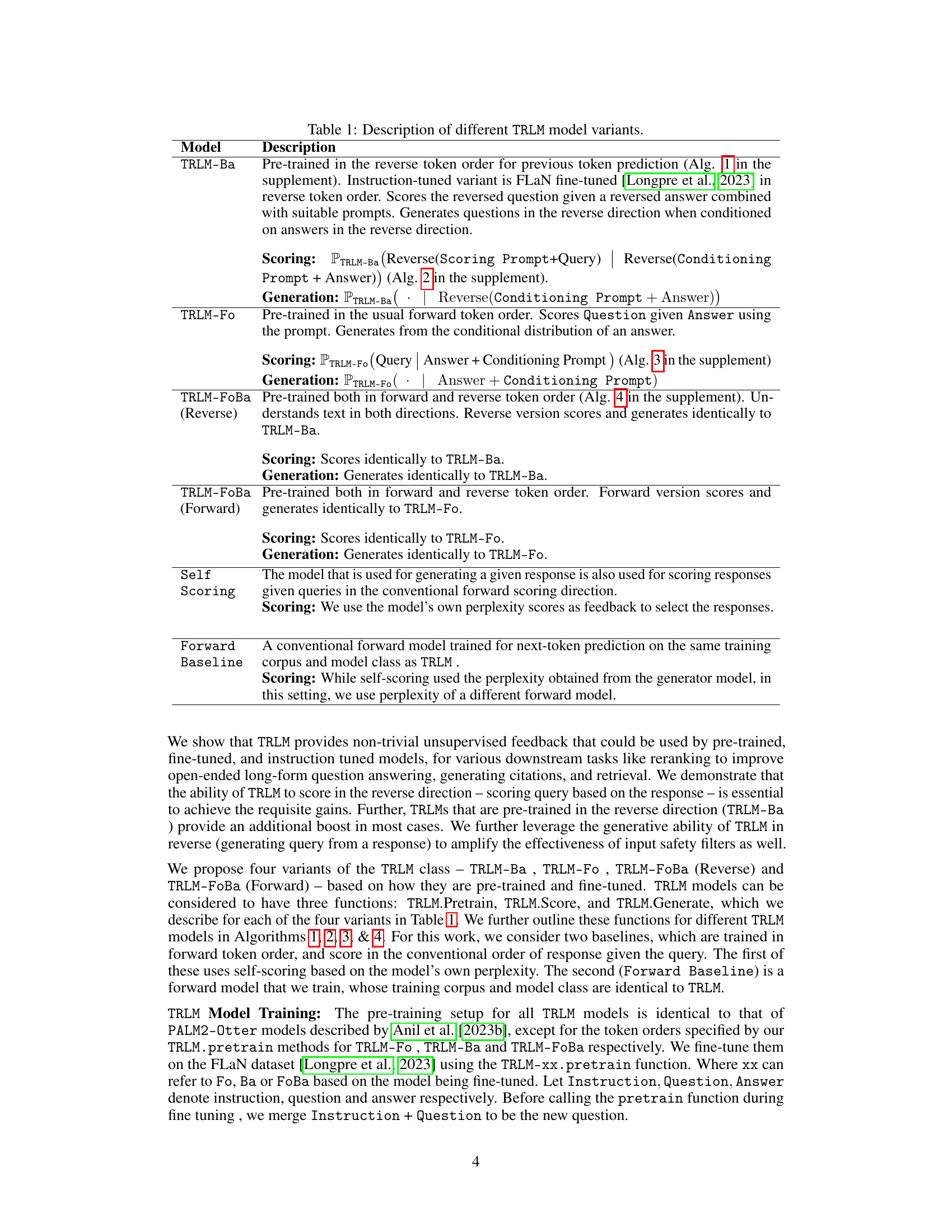

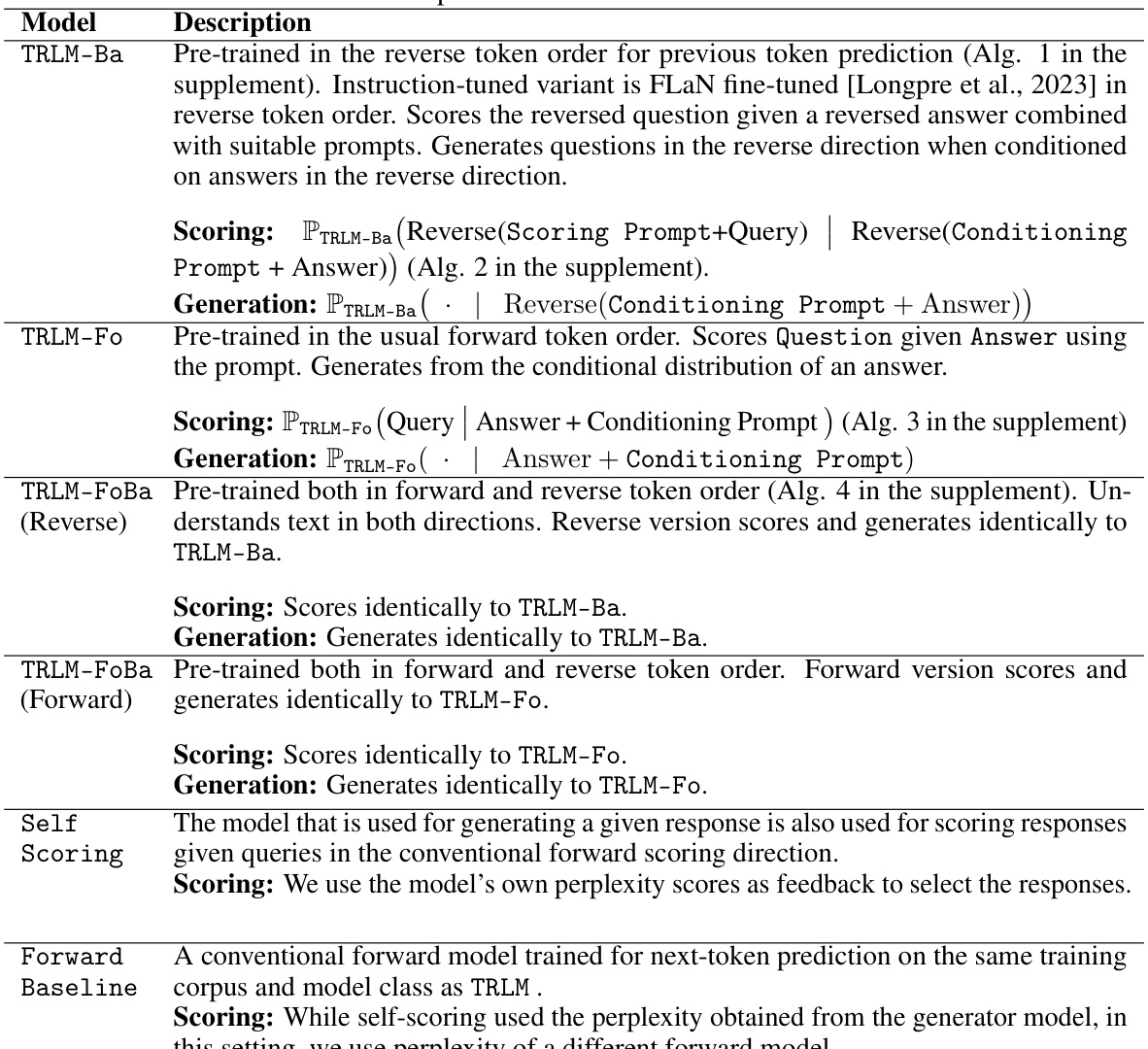

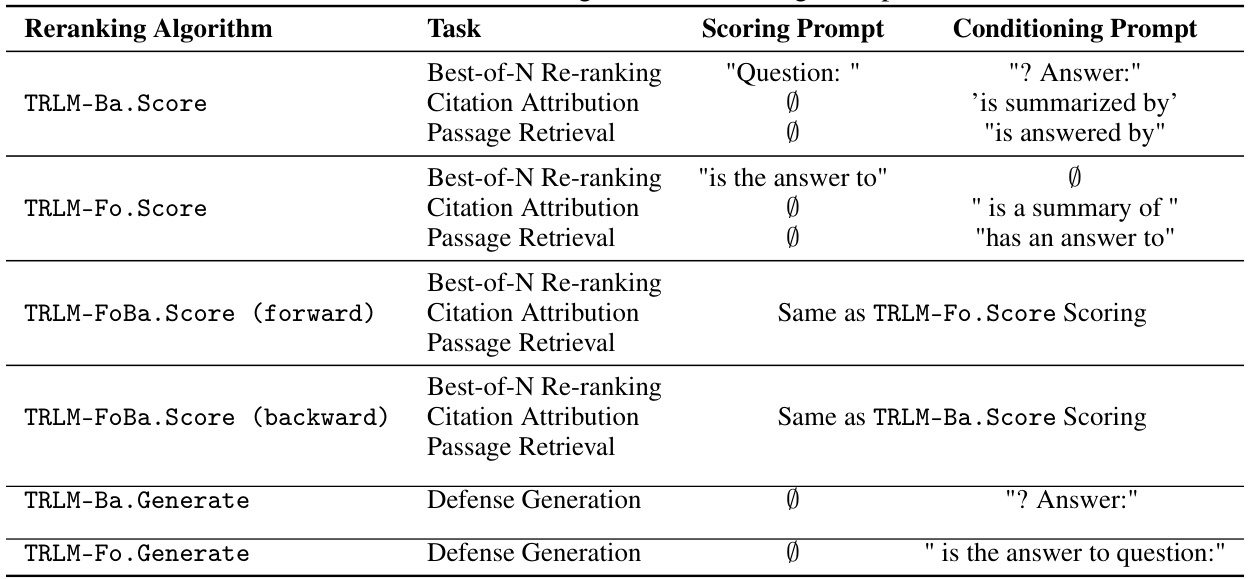

This table describes four variations of the Time Reversed Language Model (TRLM): TRLM-Ba, TRLM-Fo, TRLM-FoBa (Reverse), and TRLM-FoBa (Forward). Each model variant is differentiated by its pre-training method (reverse token order, forward token order, or both) and how it scores and generates queries given responses. The table details the scoring and generation processes for each variant, highlighting their unique characteristics and behaviors in relation to forward language models.

In-depth insights#

Reversed LLMs#

The concept of “Reversed LLMs” introduces a fascinating paradigm shift in large language model (LLM) training and application. Instead of the conventional forward prediction (query to response), reversed LLMs predict in the reverse direction (response to query). This approach offers several intriguing possibilities. Firstly, it provides a novel mechanism for unsupervised feedback. By training a model to generate queries from responses, we can effectively evaluate the quality and relevance of LLM outputs without relying on expensive human annotation. Secondly, this reversal allows for a more nuanced understanding of LLM behavior. Analyzing the queries generated from different responses can reveal underlying biases or limitations in the forward model, potentially leading to improved model design and training. Thirdly, reversed LLMs can enhance downstream tasks. For instance, reranking multiple forward model generations using reverse LLM scores can significantly boost accuracy in question answering, citation generation, and passage retrieval. Finally, there’s the potential for enhanced safety. By using reversed LLMs to generate queries from potentially unsafe responses, we can create more robust safety filters that are less prone to adversarial attacks.

Unsupervised Feedback#

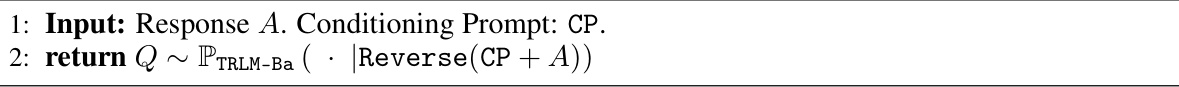

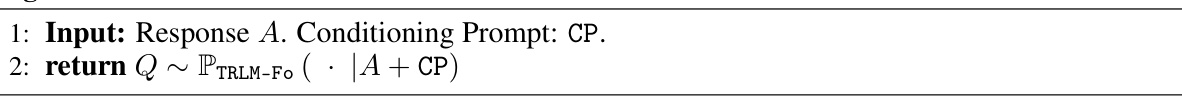

The concept of ‘Unsupervised Feedback’ in the context of large language models (LLMs) is a significant advancement. The core idea revolves around enabling LLMs to provide feedback on their own outputs without relying on explicit human supervision, thus reducing the cost and effort associated with traditional supervised methods like Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF). This is achieved by employing time-reversed language models (TRLMs) which process information backward in time. TRLMs score and generate queries when given responses, effectively performing the opposite of a standard LLM’s query-response flow. The paper explores several model variants: TRLM-F0 (forward model prompted to operate in reverse), TRLM-Ba (pre-trained in reverse token order), and TRLM-FoBa (pre-trained in both forward and reverse orders). The unsupervised feedback derived from these TRLMs is leveraged for multiple purposes, including reranking model outputs, improving citation generation and passage retrieval, and strengthening safety filters by identifying false negatives through query generation. The key novelty lies in the use of reverse pre-training, as evidenced by TRLM-Ba’s superior performance compared to models using only reverse prompting. This highlights a fundamental shift in how we approach LLM training and evaluation, enabling more efficient and scalable methods for improving LLM performance and safety.

Reranking & Scoring#

The concept of “Reranking & Scoring” in the context of large language models (LLMs) centers on refining the output of an LLM by using a secondary scoring mechanism to reorder or re-rank multiple generated responses. This process is crucial because LLMs, particularly when generating multiple outputs (e.g., best-of-N generation), may not consistently produce the highest-quality response as the first output. A scoring model acts as an evaluator, assigning a score to each LLM-generated response based on various factors like relevance, coherence, and fluency. The scores are then used to reorder the responses, placing the highest-scoring one at the top. The choice of scoring method significantly impacts the overall performance. Simple methods, like using the LLM’s own perplexity, can be less effective compared to more sophisticated approaches that leverage human feedback or incorporate external knowledge sources. The effectiveness of reranking heavily depends on the diversity of the initial LLM generations; more diverse initial responses provide a richer space for the scoring model to operate in. Furthermore, integrating reverse language models (TRLMs) into reranking creates an interesting avenue of exploration, where responses inform the scoring of the corresponding queries. This reverse approach allows for unsupervised feedback, potentially improving the overall quality of LLM generations without requiring human intervention.

Jailbreak Defense#

The research explores enhancing Large Language Model (LLM) safety by addressing vulnerabilities to “jailbreak” attacks. A novel approach involves utilizing Time-Reversed Language Models (TRLMs) to generate queries from responses. This allows for a more robust defense by projecting the potentially unsafe response back into the input space of a safety filter. The TRLM acts as a bridge, linking the output of the LLM to an input filter better suited to detect malicious inputs. This method aims to reduce false negatives (failing to identify unsafe content) without significantly increasing false positives (incorrectly classifying safe content). The effectiveness of this technique is empirically demonstrated, showing improved performance against several attacks compared to existing methods. This approach offers a unique and promising defense strategy against adversarial attacks by leveraging the generative capabilities of TRLMs to augment traditional input safety filters, addressing a critical weakness in current LLM security protocols. The results suggest this is a viable method for improving LLM safety and robustness.

Bipartite Model#

A bipartite graph model, in the context of a large language model (LLM) research paper, likely represents the relationship between questions and their corresponding answers. This model simplifies the complex interaction between questions and answers, making it easier to analyze and understand the impact of model choices. The model assumes a many-to-many relationship, where a question may have several correct answers, and an answer may be correct for several questions. The edges of the graph would represent the correct answer-question pairings. Analyzing this model might help to explain how the model handles ambiguity in question answering tasks. A focus on the model’s prediction of the correct pairings could reveal valuable insights into how the LLMs score or generate questions and answers. For example, a deviation from the idealized distribution, possibly caused by hallucination, could indicate problems in the LLMs’ reasoning or knowledge representation. Therefore, this simplified approach provides a useful way to quantify the model’s performance and understand the effects of training choices, such as using time-reversed language models, in both theoretical and practical aspects.

More visual insights#

More on figures

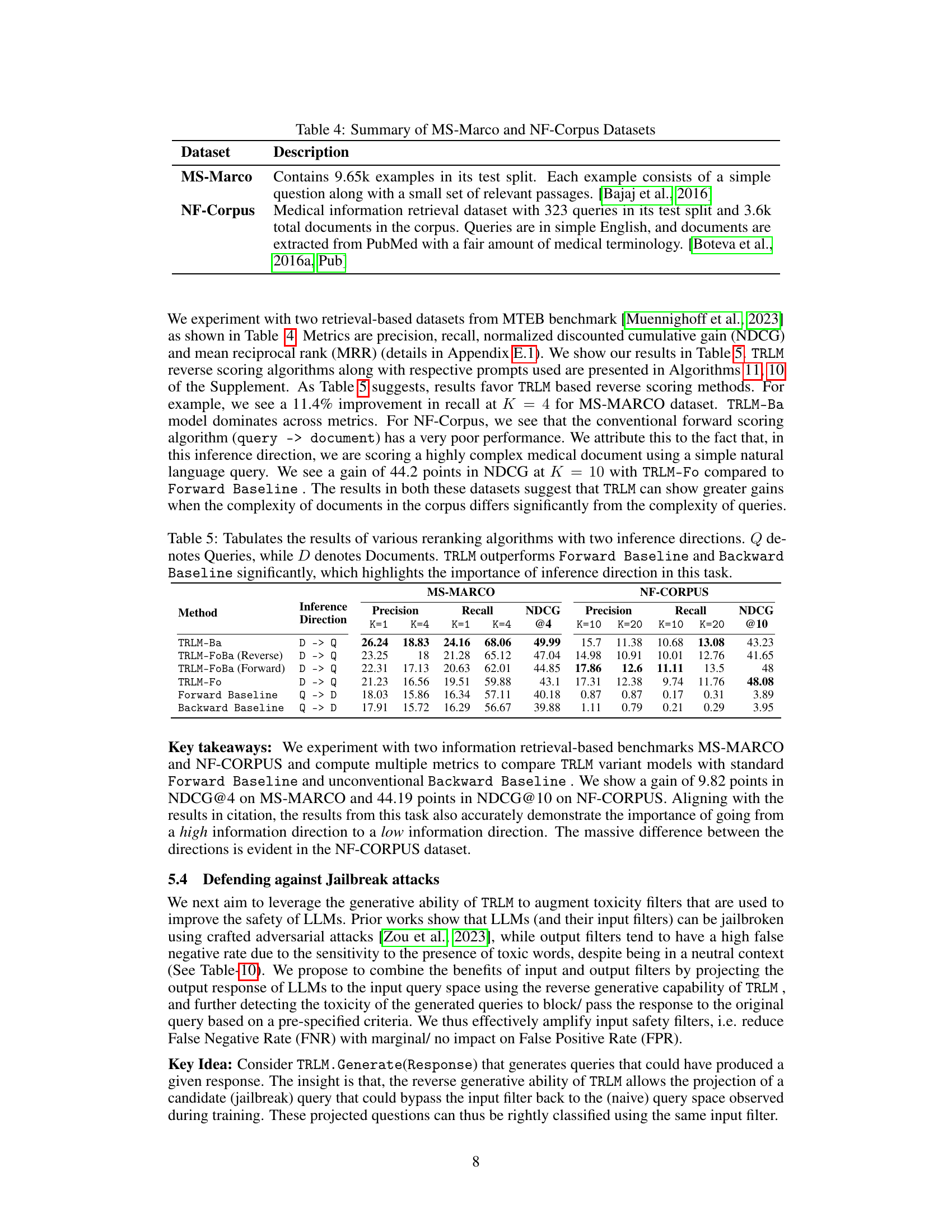

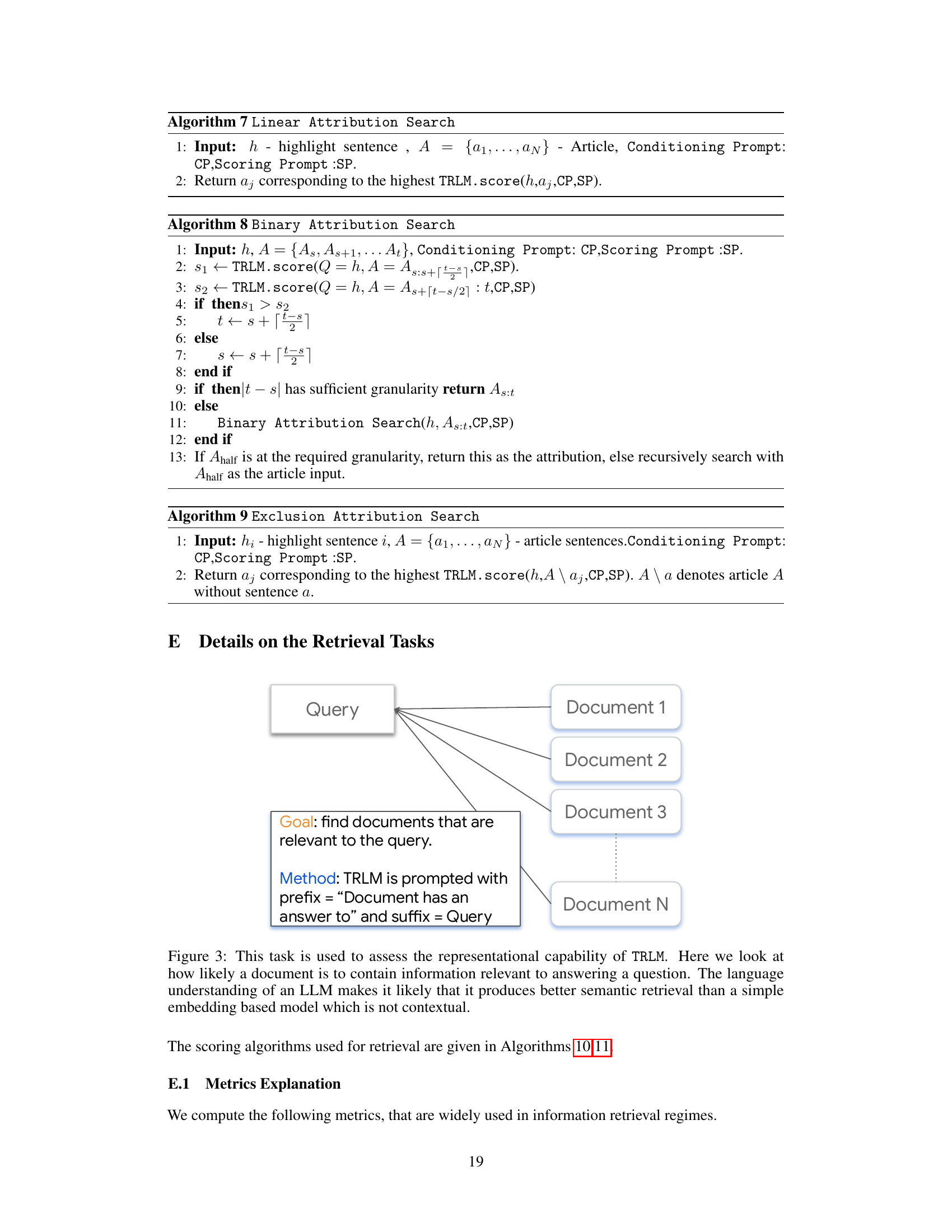

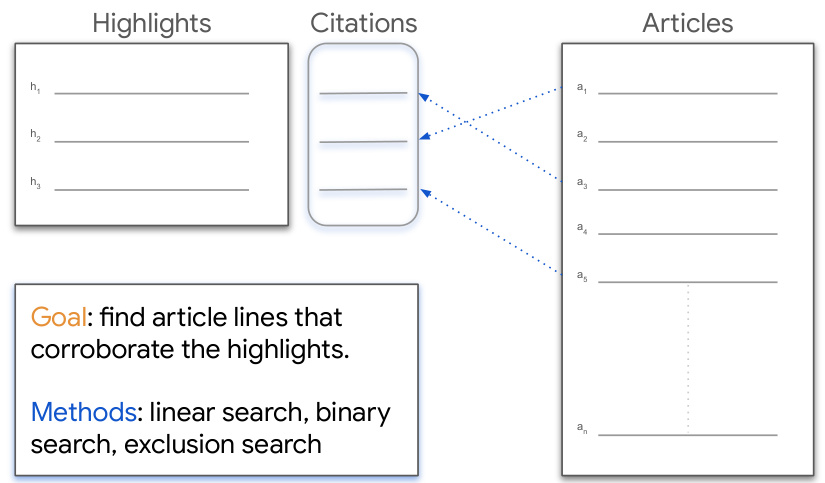

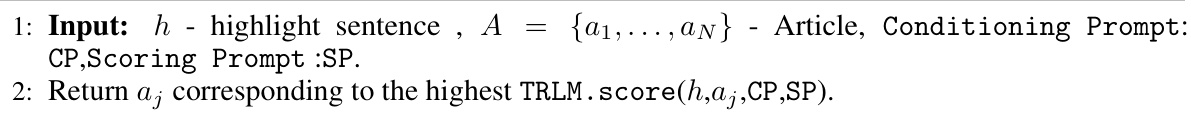

This figure illustrates the task of citation attribution. Given a set of highlight sentences (summaries) from an article, the goal is to identify the corresponding sentences in the original article that best support each highlight. Three search methods are employed: linear search, binary search, and exclusion search. Each method uses the TRLM (Time Reversed Language Model) to score sentences in the article based on their relevance to a given highlight. The best-scoring sentences are selected as the citations.

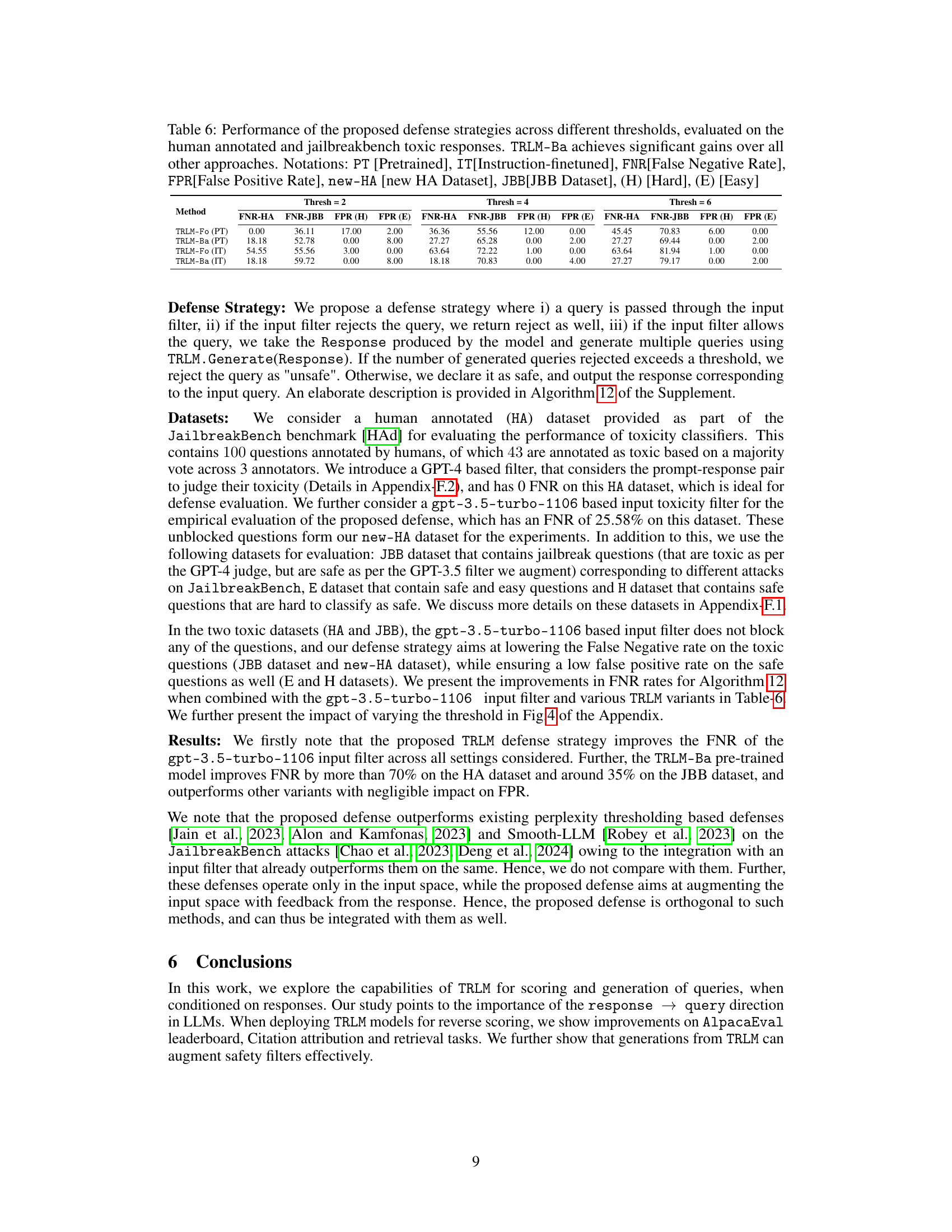

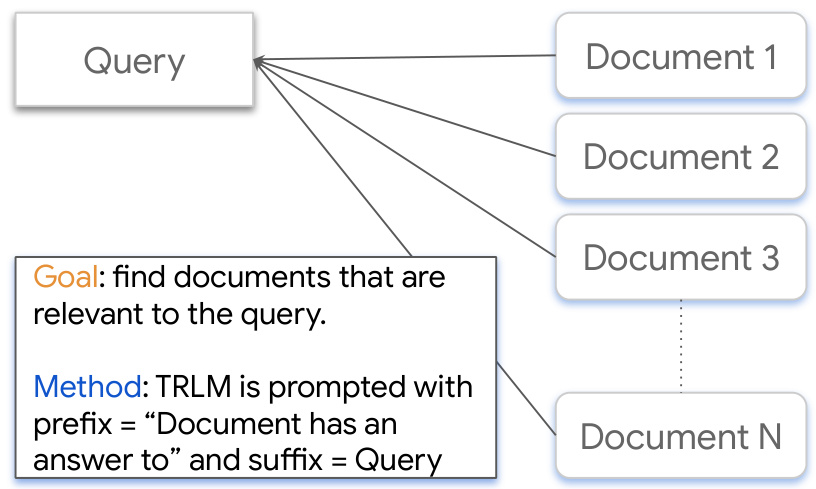

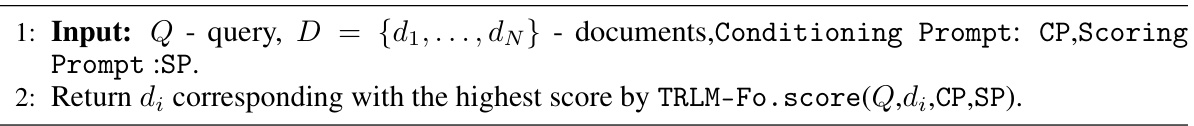

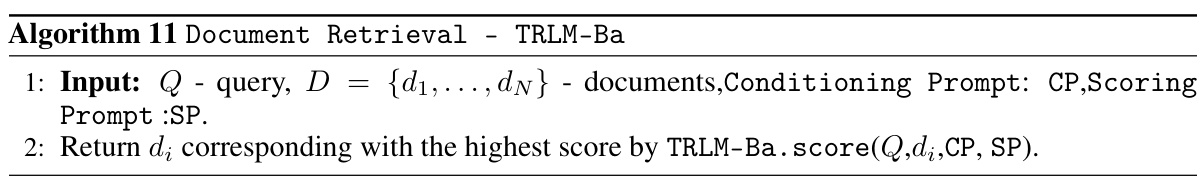

This figure illustrates the document retrieval task. The goal is to find documents relevant to a given query. The method uses a TRLM model, prompted with a prefix (‘Document has an answer to’) and the query as a suffix, to achieve semantic retrieval. This approach is expected to perform better than simple embedding-based methods because of the LLM’s contextual understanding.

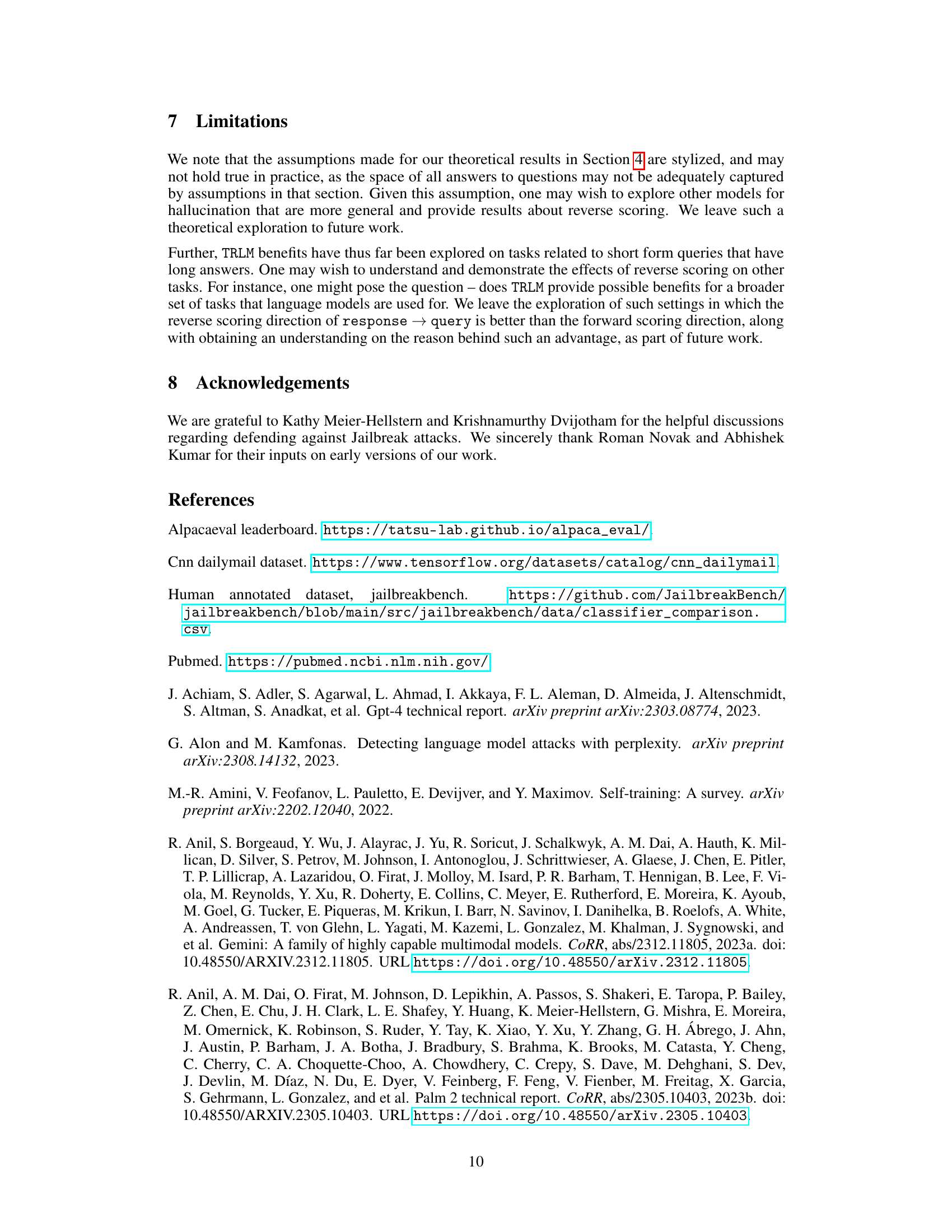

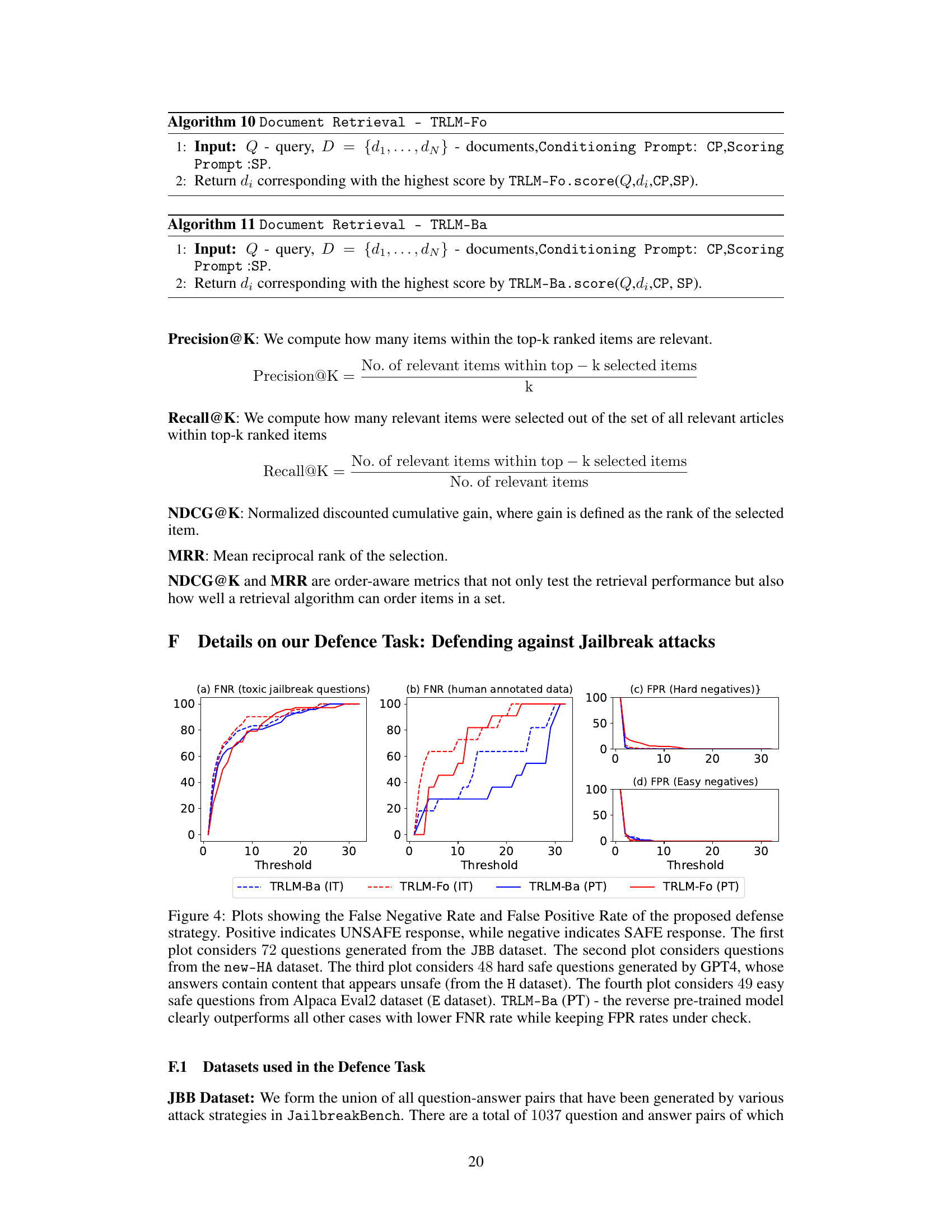

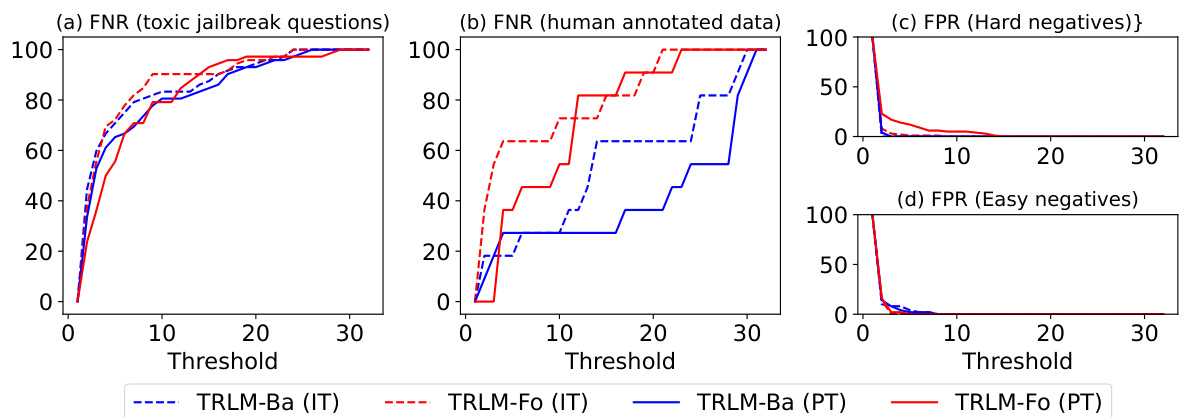

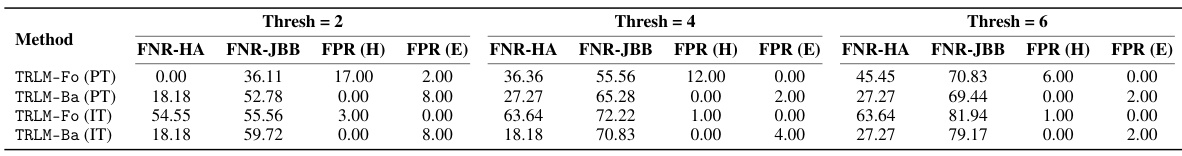

This figure visualizes the performance of different models in a jailbreak defense task. It shows the false negative rate (FNR) and false positive rate (FPR) for various models across four different datasets: toxic jailbreak questions (JBB), human-annotated data (HA), hard safe questions (H), and easy safe questions (E). The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the TRLM-Ba (PT) model, which achieves lower FNR while maintaining low FPR across datasets.

More on tables

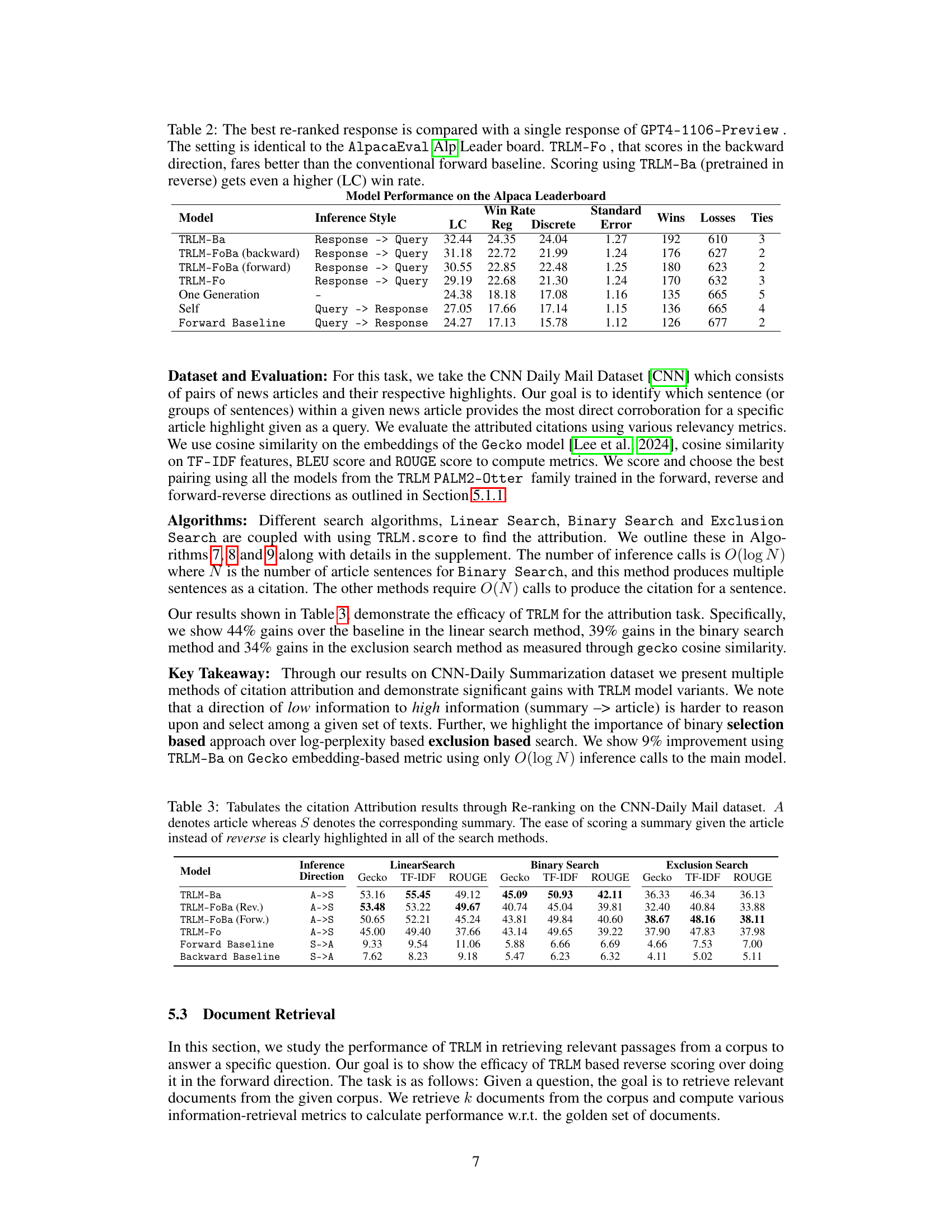

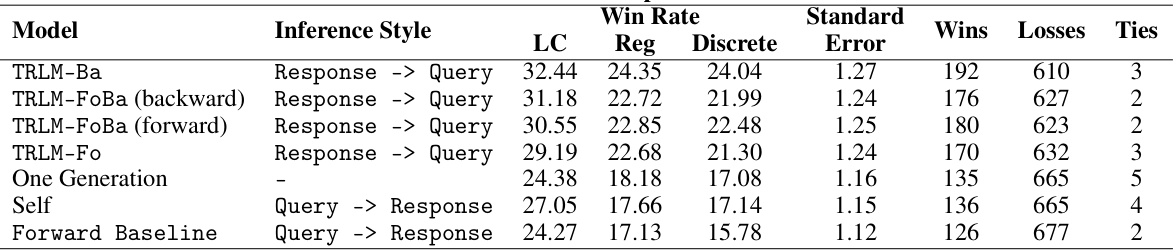

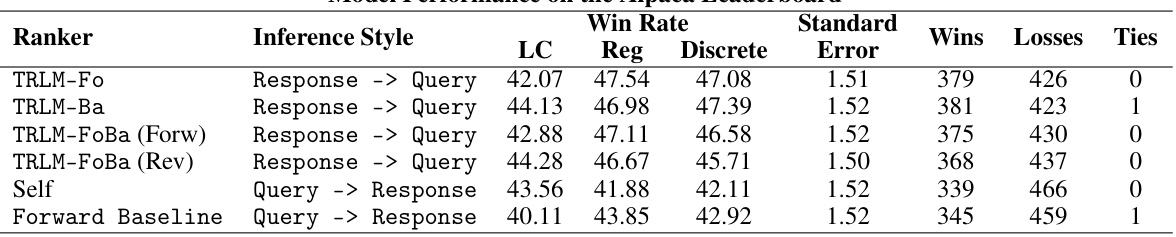

This table presents the results of the Alpaca Leaderboard evaluation. It compares the performance of different models, including various TRLM variants and baselines, in a best-of-N reranking task. The models’ performance is evaluated based on win rates, using length-controlled win rates to account for the length bias that is otherwise preferred by GPT4-1106-Preview. The table shows that TRLM models, especially TRLM-Ba, outperform the baselines, demonstrating the effectiveness of time-reversed scoring for improving the quality of LLM generations.

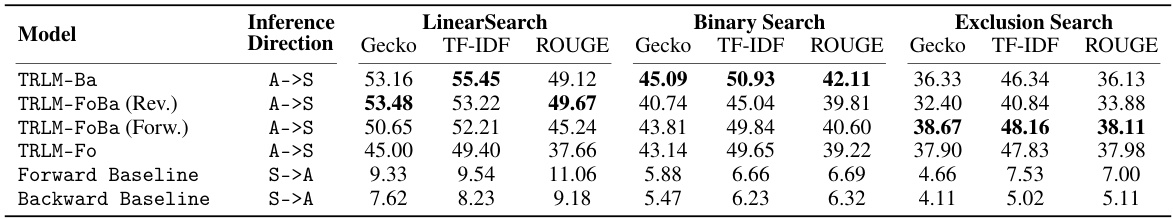

This table presents the results of citation attribution experiments using different methods and scoring directions on the CNN Daily Mail dataset. The goal is to identify which sentence(s) in a news article best support a given highlight summary. The table compares the performance of various models (TRLM-Ba, TRLM-FoBa, TRLM-Fo, Forward Baseline, Backward Baseline) using different search algorithms (Linear Search, Binary Search, Exclusion Search) and evaluation metrics (Gecko cosine similarity, TF-IDF cosine similarity, ROUGE). The results demonstrate the effectiveness of TRLM-based reverse scoring in improving citation attribution accuracy.

This table compares the performance of different models on the AlpacaEval Leaderboard, a benchmark for evaluating the quality of language models. The models used are TRLM-Ba, TRLM-Fo, TRLM-FoBa (forward), TRLM-FoBa (backward), One Generation, Self, and Forward Baseline. The table shows the win rate, a measure of how often the model’s response is better than a baseline response, along with standard, length-controlled, and discrete win rates. The results demonstrate that TRLMs, particularly TRLM-Ba, significantly improve the performance of the base model compared to the conventional forward baseline, highlighting the benefits of scoring in the reverse direction.

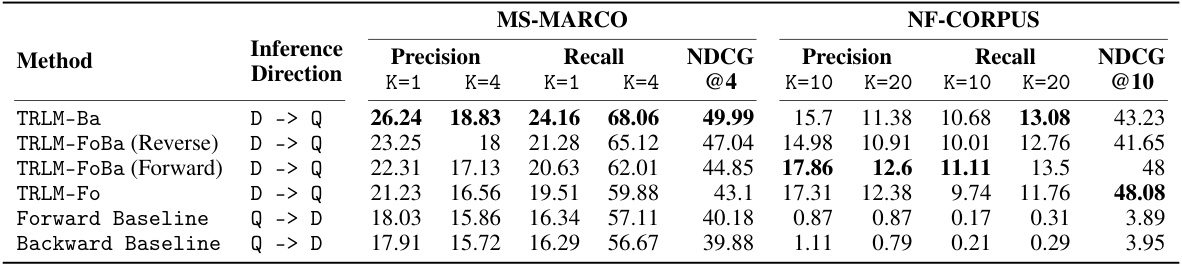

This table presents the performance of different reranking algorithms on two information retrieval datasets, MS-MARCO and NF-CORPUS. The algorithms are categorized by inference direction (query to document or document to query) and model type (TRLM variants, Forward Baseline, Backward Baseline). The results show precision, recall, and NDCG@k metrics for different values of k, demonstrating that TRLM models, especially when using a document-to-query approach, significantly outperform baselines. This highlights the importance of inference direction in these tasks.

This table presents the performance of different defense strategies against jailbreak attacks on various datasets. The strategies use different variants of the TRLM model (pre-trained and instruction-tuned), combined with an input toxicity filter. The table shows the False Negative Rate (FNR) and False Positive Rate (FPR) at different thresholds, indicating the effectiveness of the defense strategies in reducing toxic outputs while maintaining a low false positive rate. The results demonstrate that TRLM-Ba, particularly the instruction-tuned variant, significantly outperforms other methods.

This table presents the results of comparing different models’ performance on the AlpacaEval Leaderboard. It contrasts the win rates of various TRLM models (scoring in reverse) against a standard forward baseline and a self-scoring baseline. The table highlights that time-reversed scoring methods, particularly TRLM-Ba, achieve significantly higher win rates, demonstrating the effectiveness of time reversal for unsupervised feedback in LLMs.

This table compares the performance of different models on the AlpacaEval leaderboard, a benchmark for evaluating language models. The models use different scoring and inference methods, including time-reversed language models (TRLM). The table shows that TRLM models, particularly TRLM-Ba, achieve higher win rates compared to a forward baseline, demonstrating the effectiveness of using time-reversed scoring for reranking responses.

This table shows the scoring prompts and conditioning prompts used for different tasks in the experiments. The prompts are tailored to each task (Best-of-N reranking, citation attribution, and passage retrieval) and to the direction of the language model (forward or backward). This table is essential for understanding how the model is prompted to score the different responses and generate different queries for each task.

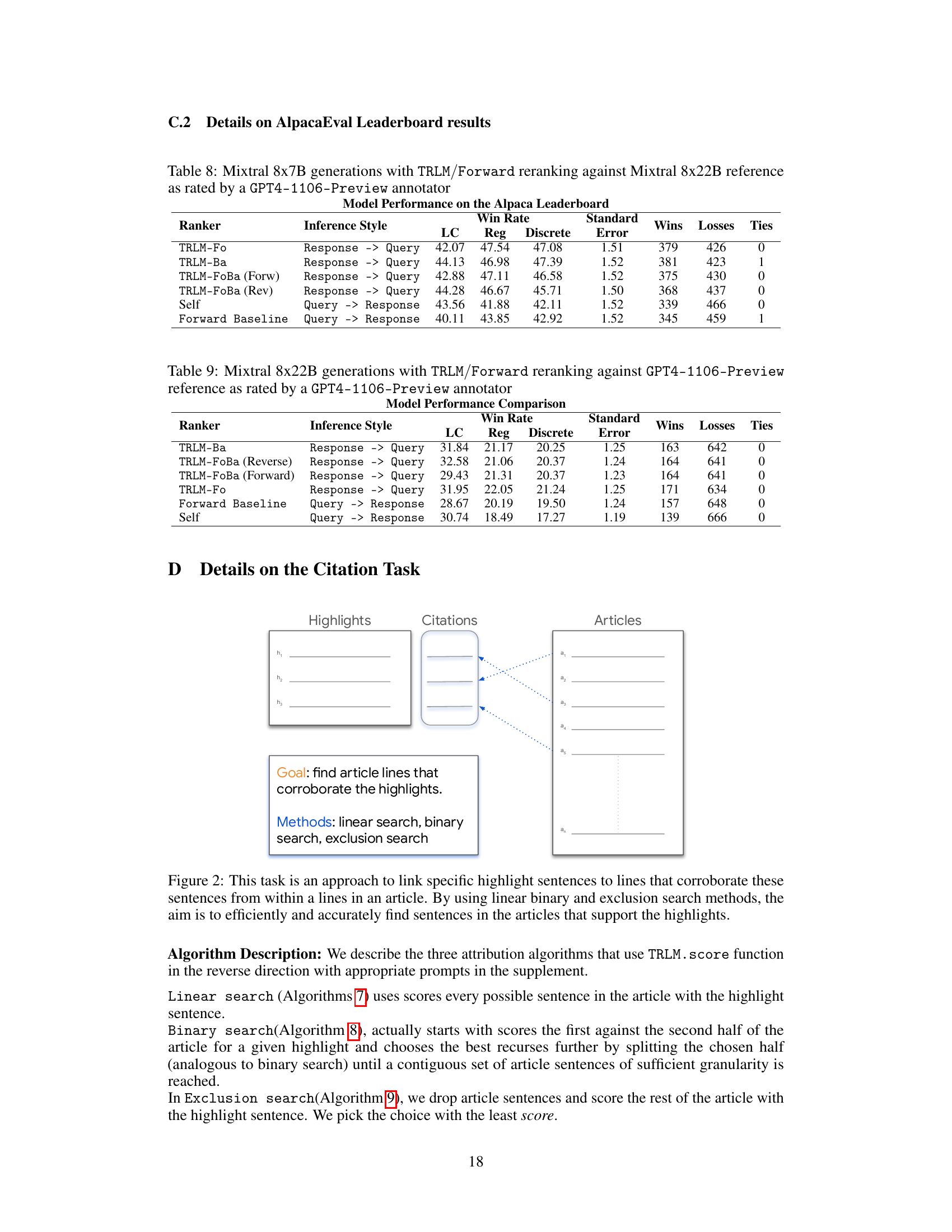

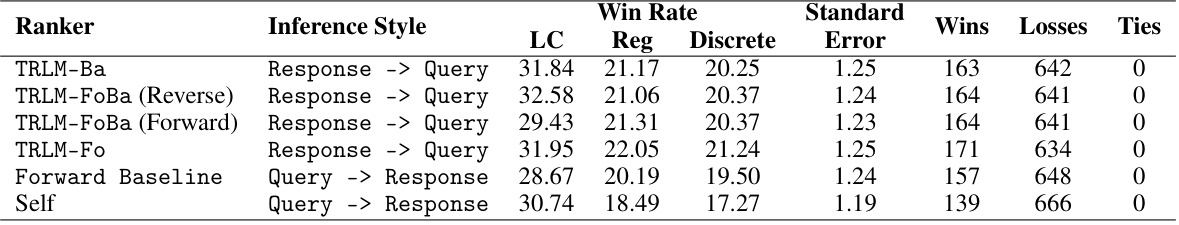

This table presents the results of the Alpaca Leaderboard evaluation using Mixtral 8x7B model with different reranking methods including TRLM variants, Self and Forward Baselines. The evaluation is performed against a Mixtral 8x22B reference model, and the results are assessed by a GPT4-1106-Preview annotator. Metrics shown include win rate (LC, Reg, Discrete), standard error, wins, losses and ties.

This table presents the results of an AlpacaEval leaderboard experiment using the Mixtral 8x22B language model. Different reranking methods are compared: TRLM-Ba, TRLM-FoBa (Reverse), TRLM-FoBa (Forward), TRLM-Fo, Forward Baseline, and Self. The table shows win rates (LC, Reg, Discrete), standard errors, and the counts of wins, losses, and ties for each method. The goal is to evaluate the effectiveness of different TRLM variants in improving the model’s responses compared to a strong baseline.

This table presents the results of comparing different models’ performance on the AlpacaEval leaderboard. The models are evaluated based on their win rate, a metric representing the percentage of times the model generates a better response than a baseline model. The table showcases the improvement achieved by using Time-Reversed Language Models (TRLMs) for scoring in the reverse direction (Response → Query) compared to the conventional forward scoring (Query → Response). Specifically, it demonstrates that TRLM-Fo (which scores in reverse but uses a forward-trained model) outperforms the forward baseline, and TRLM-Ba (pre-trained in reverse) achieves even higher win rates.

This table presents the results of comparing different models’ performance on the AlpacaEval leaderboard. It shows the win rates (standard and length-controlled) achieved by several models, including various TRLM configurations (TRLM-Ba, TRLM-Fo, TRLM-FoBa), a self-scoring baseline, and a forward baseline. The table highlights the improvement in win rates obtained by using TRLMs for scoring in the reverse direction (response->query) compared to conventional forward scoring (query->response). The length-controlled win rate metric is particularly emphasized, indicating that TRLMs are effective even when accounting for length bias.

This table presents the results of reranking experiments on the AlpacaEval leaderboard. It compares the performance of different models, including TRLM-Ba, TRLM-Fo, TRLM-FoBa (forward and backward), Self, and Forward Baseline, in terms of win rate (standard and length-controlled) when using various scoring methods. The results show that TRLM-Ba and TRLM-Fo, which score in the reverse direction (response to query), achieve higher win rates compared to the forward baseline, demonstrating the effectiveness of reverse scoring in improving LLM generations.

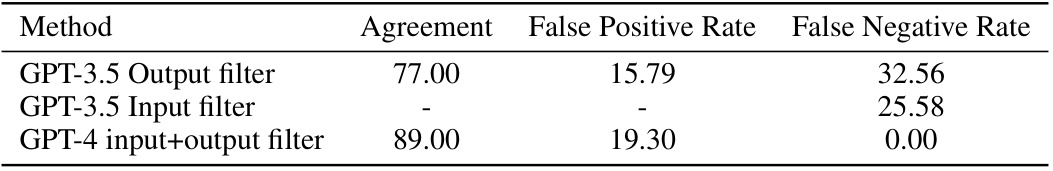

This table compares the performance of different input and output filter combinations on a human-annotated dataset from JailbreakBench. It shows the agreement rate, false positive rate, and false negative rate for each method. The GPT-3.5 input filter is a baseline, while the GPT-4 input+output filter represents a combined approach. The numbers reflect the accuracy and error rates of the filter combinations in identifying toxic content.

Full paper#