↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional methods for analyzing language model scaling laws rely on extensive training across multiple scales, proving computationally expensive and resource intensive. This paper addresses this challenge by proposing an observational approach. This innovative approach leverages publicly available models and their benchmark performance to infer scaling laws, thereby reducing computational costs and expanding the scope of analysis.

This observational approach reveals a surprising level of predictability in complex scaling behaviors. The researchers demonstrate its effectiveness in forecasting emergent capabilities, assessing agent performance, and estimating the impact of post-training techniques. By identifying a low-dimensional capability space that underlies model performance, the study provides a more efficient and generalized framework for understanding language model scaling. This method has significant implications for researchers seeking to develop, improve, and benchmark language models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it introduces a novel observational approach to studying language model scaling, overcoming limitations of traditional methods. This enables more efficient and comprehensive analyses, offering valuable insights into model behavior and guiding future research directions.

Visual Insights#

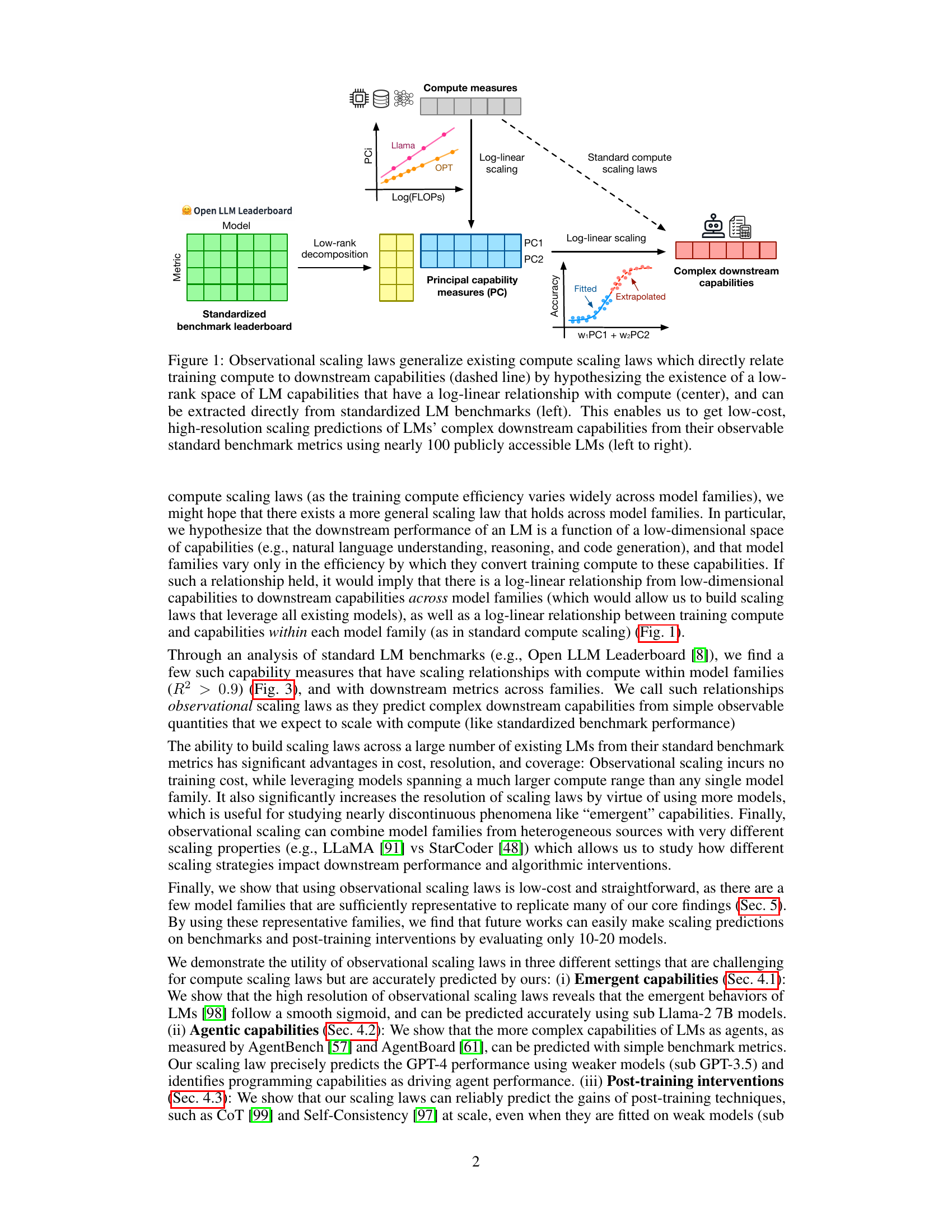

This figure illustrates the observational scaling laws proposed in the paper. It shows how the authors move from existing compute scaling laws (which directly link training compute to model performance) to their proposed observational scaling laws. The key innovation is the identification of a low-dimensional capability space that captures the performance of LMs across diverse benchmarks. This capability space is shown to have a log-linear relationship with compute, thereby allowing prediction of downstream performance from easily obtainable benchmark metrics. The figure highlights the process of extracting principal capability measures (PCs) from standardized benchmarks, using these measures to predict complex downstream capabilities, and extrapolating to unobserved regions of capability space.

This table presents the metadata and evaluation results for the pretrained base language models used in sections 4.1, 4.3, and 5 of the paper. It includes model family, model name, number of parameters (in billions), training data size (in trillions of tokens), total training FLOPs (in 1e21), and scores on several benchmark tasks: MMLU, ARC-C, HellaSwag, Winograd, TruthfulQA, XWinograd, and HumanEval. The table provides a comprehensive overview of the models’ characteristics and their performance across different evaluation metrics. Note that the most up-to-date results can be found at the provided GitHub link.

In-depth insights#

Observational Scaling#

The concept of “Observational Scaling” presents a compelling alternative to traditional scaling law methods in evaluating language models. Instead of the computationally expensive process of training numerous models across various scales, observational scaling leverages existing publicly available models to derive scaling relationships. This approach is particularly beneficial due to its cost-effectiveness and high resolution, enabling analyses with far greater data granularity. By focusing on the identification of a low-dimensional capability space—a low-rank representation of model capabilities derived from standard benchmark metrics—observational scaling allows for the generalization of scaling laws across diverse model families, despite variations in training compute efficiencies. This is a significant advance because it enables the prediction of complex phenomena, such as emergent behaviors and the impact of post-training techniques, with surprising accuracy, directly from readily accessible data. The predictive power and versatility of observational scaling laws make it a valuable tool for researchers and engineers seeking to efficiently understand and predict the future behavior of large language models.

Capability Space#

The concept of ‘Capability Space’ in the context of large language models (LLMs) is crucial for understanding how model performance scales with increased computational resources. It posits that an LLM’s capabilities aren’t simply a monolithic measure, but rather a multifaceted collection of distinct skills. These skills can be represented as a low-dimensional space, enabling easier visualization and analysis of model performance across various tasks and benchmarks. Instead of directly correlating compute to a single performance metric, this approach focuses on how compute influences different capabilities within the space. This is especially valuable when dealing with diverse model families trained with varying efficiencies, as it allows for a more generalized scaling law applicable across different architectural choices and training data. By understanding the relationships between capabilities in this space, we can better predict the emergence of new, complex behaviors and the effectiveness of post-training interventions. This framework moves beyond simple scaling laws by providing a richer understanding of LLM development and allows for more accurate extrapolations regarding future model performance.

Emergent Abilities#

The concept of “emergent abilities” in large language models (LLMs) refers to capabilities that appear unexpectedly as model size and training data increase. These abilities are not explicitly programmed but arise from the complex interplay of model parameters and training data. Researchers debate whether these abilities represent genuinely novel phenomena or merely the extrapolation of existing trends. Some argue that emergent abilities are merely the result of improved scaling laws and that a careful analysis of performance across different model sizes and training data reveals a consistent, predictable pattern. Others contend that these capabilities represent a fundamental shift in model behavior, highlighting the limits of simple scaling laws and suggesting that these unexpected features are not simply a matter of quantity but also quality. A key challenge lies in precisely defining and measuring emergent abilities, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. High-resolution scaling analysis is crucial for distinguishing between truly emergent behavior and the gradual unfolding of existing capabilities, a distinction that remains a focus of ongoing research.

Agentic Prediction#

The concept of ‘Agentic Prediction,’ as it relates to language models, centers on the ability to foresee how these models will behave as autonomous agents. This involves predicting their performance not just on standard benchmarks but also on complex, multi-step tasks that require interaction and decision-making. Success in agentic prediction requires moving beyond simple benchmarks, such as accuracy on question-answering tasks, to encompass measures that reflect the models’ abilities to plan, reason, and adapt within dynamic environments. The key challenge lies in finding appropriate metrics that accurately capture the multifaceted nature of agentic capabilities. While standard metrics may hint at potential, a more holistic evaluation that considers factors like planning horizon, adaptability to unexpected inputs, and robustness to adversarial conditions is needed. Ultimately, the goal is to anticipate the capabilities and limitations of future large language models as agents, enabling safer and more effective deployment in real-world settings. This requires a combination of theoretical advancements, more comprehensive benchmark development, and innovative evaluation methodologies.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending observational scaling laws to finetuned models, moving beyond pretrained base models. This would involve investigating how post-training interventions impact performance across diverse finetuning scenarios and scales. Additionally, future work should focus on developing surrogate measures for model complexity, going beyond simple metrics like FLOPs or parameter counts. This may allow more precise optimization and comparisons across diverse architectures and model families. Another avenue is investigating the impact of benchmark contamination on scaling law accuracy, considering potential data leakage into model training. Finally, it would be valuable to explore the heterogeneity within model families as different models within a family often demonstrate varied compute efficiencies. Addressing these areas would significantly enhance the predictive power and generalizability of observational scaling laws, improving the accessibility of resource-efficient scaling analysis.

More visual insights#

More on figures

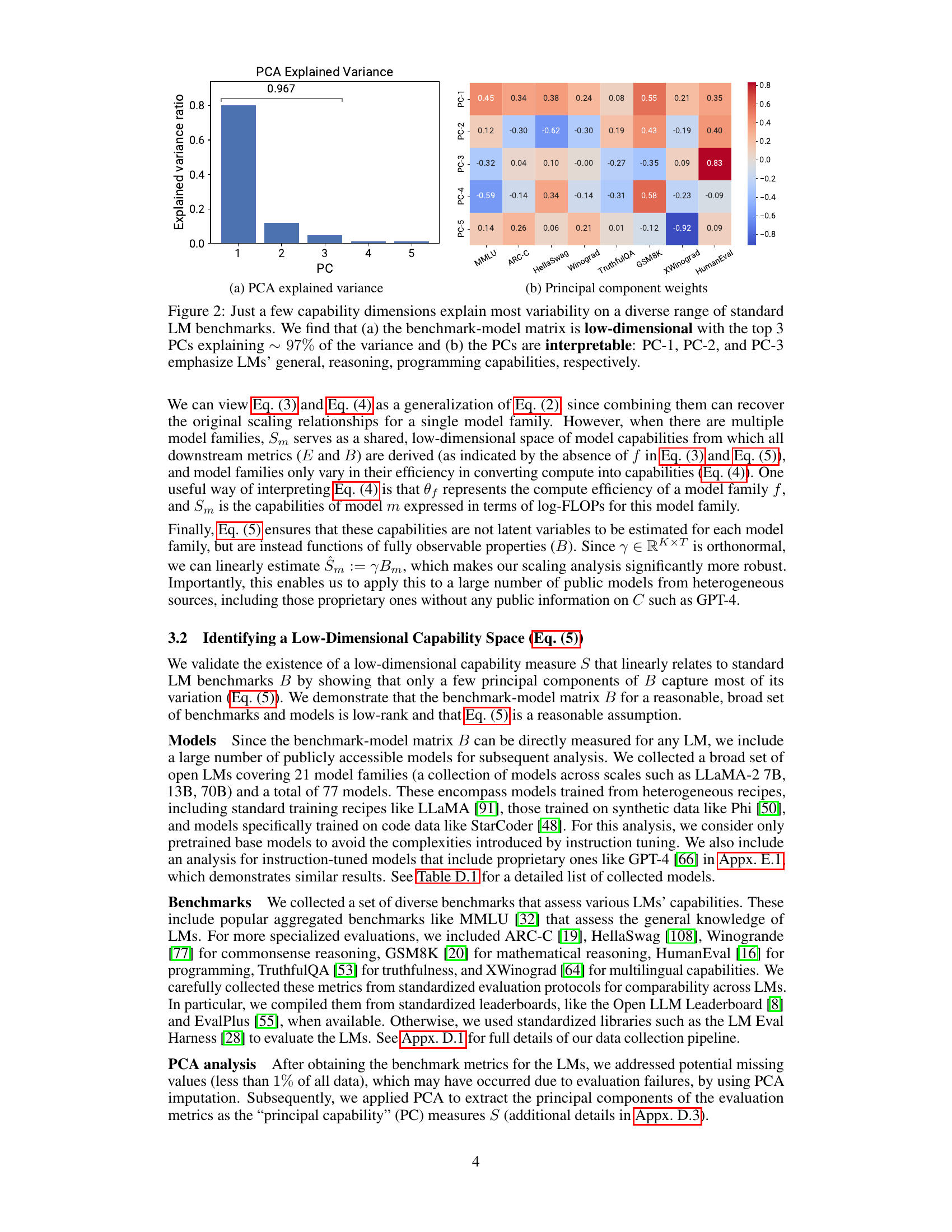

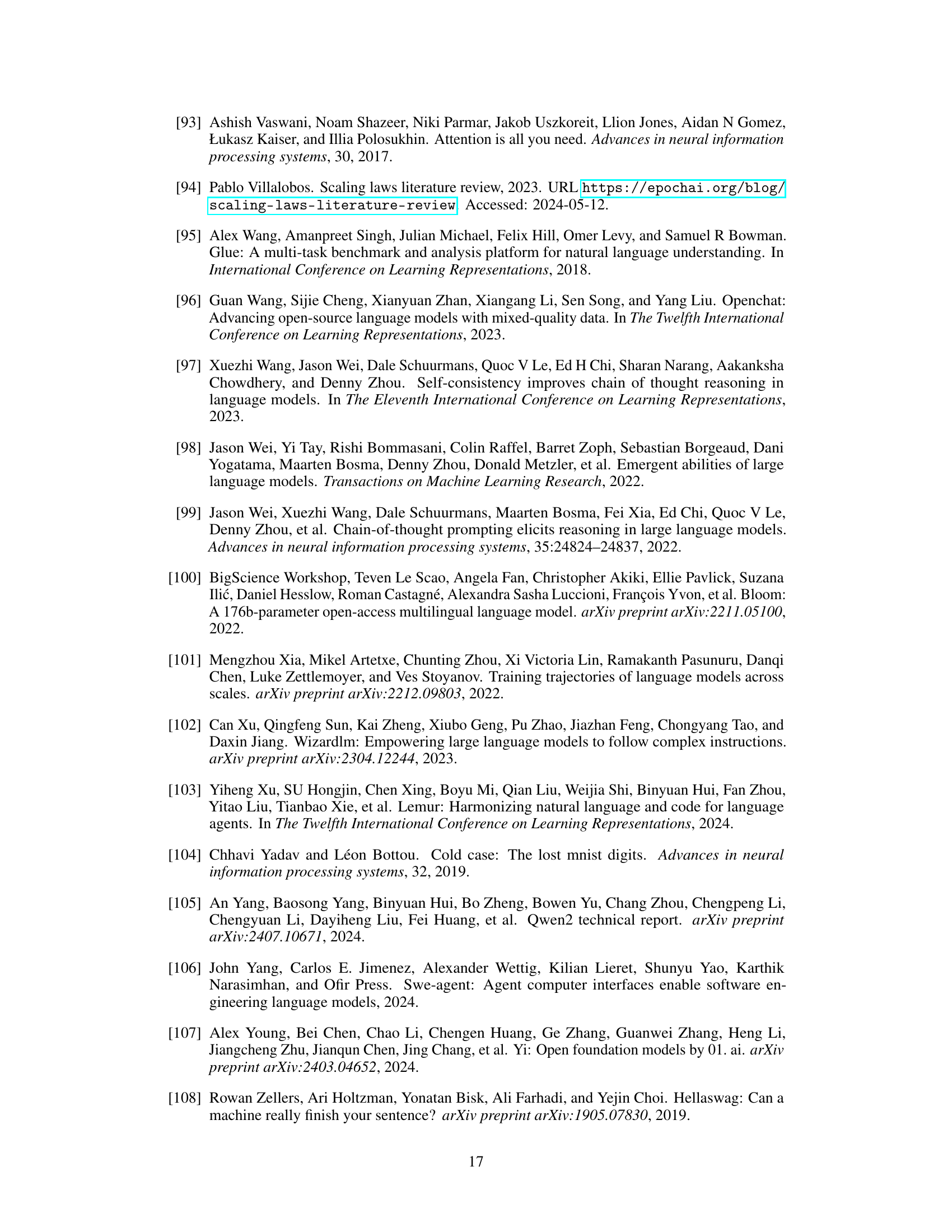

This figure demonstrates that a low-dimensional space of language model capabilities can explain most of the variability observed in a wide range of standard benchmarks. Panel (a) shows that the top three principal components (PCs) account for approximately 97% of the variance in benchmark performance, indicating a low-dimensional structure. Panel (b) presents the weights of each benchmark on each PC, offering an interpretation of each PC. PC-1 represents general capabilities, PC-2 highlights reasoning capabilities (mathematical, coding), and PC-3 emphasizes programming abilities. This suggests that complex language model capabilities may be understood as a combination of these more fundamental capabilities.

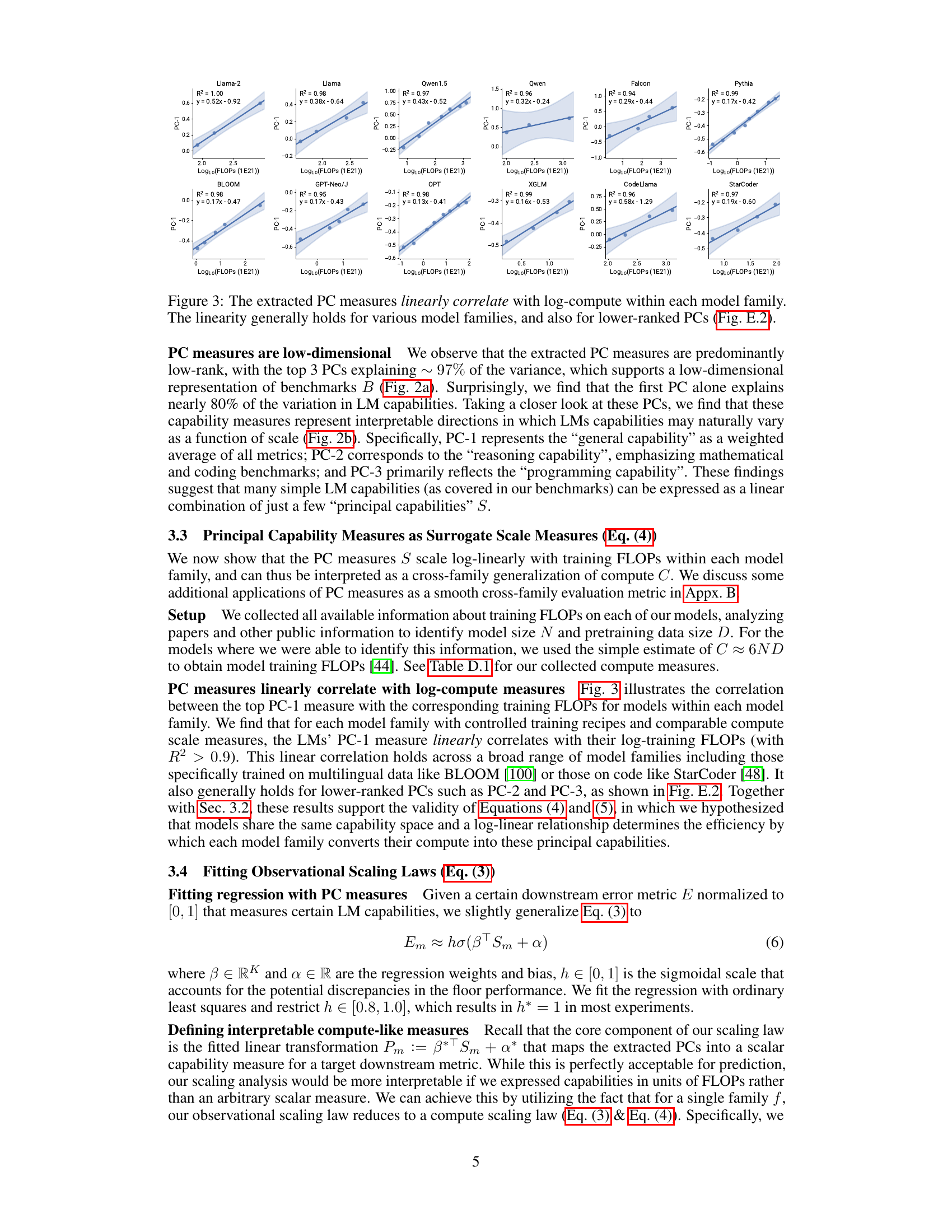

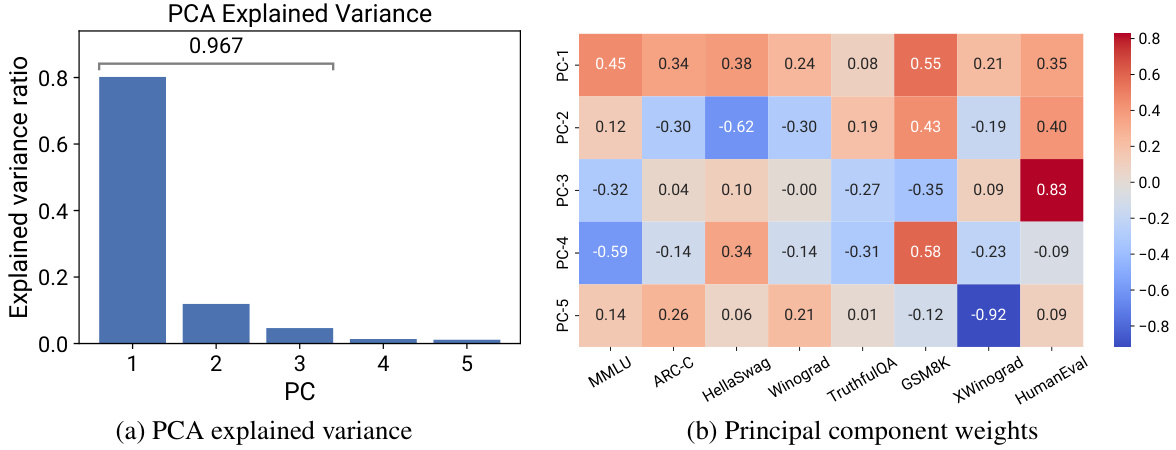

This figure shows the linear correlation between the principal component (PC) measures and the log-training FLOPs for several model families. Each panel represents a different model family, and the linear regression is displayed with the R-squared value. The strong linear correlation (high R-squared values) indicates the log-linear relationship between PCs (as surrogates for capabilities) and compute, supporting a generalized scaling law across model families. The consistency of this relationship for various model families and even lower-ranked PCs suggests that this property is robust and fundamental.

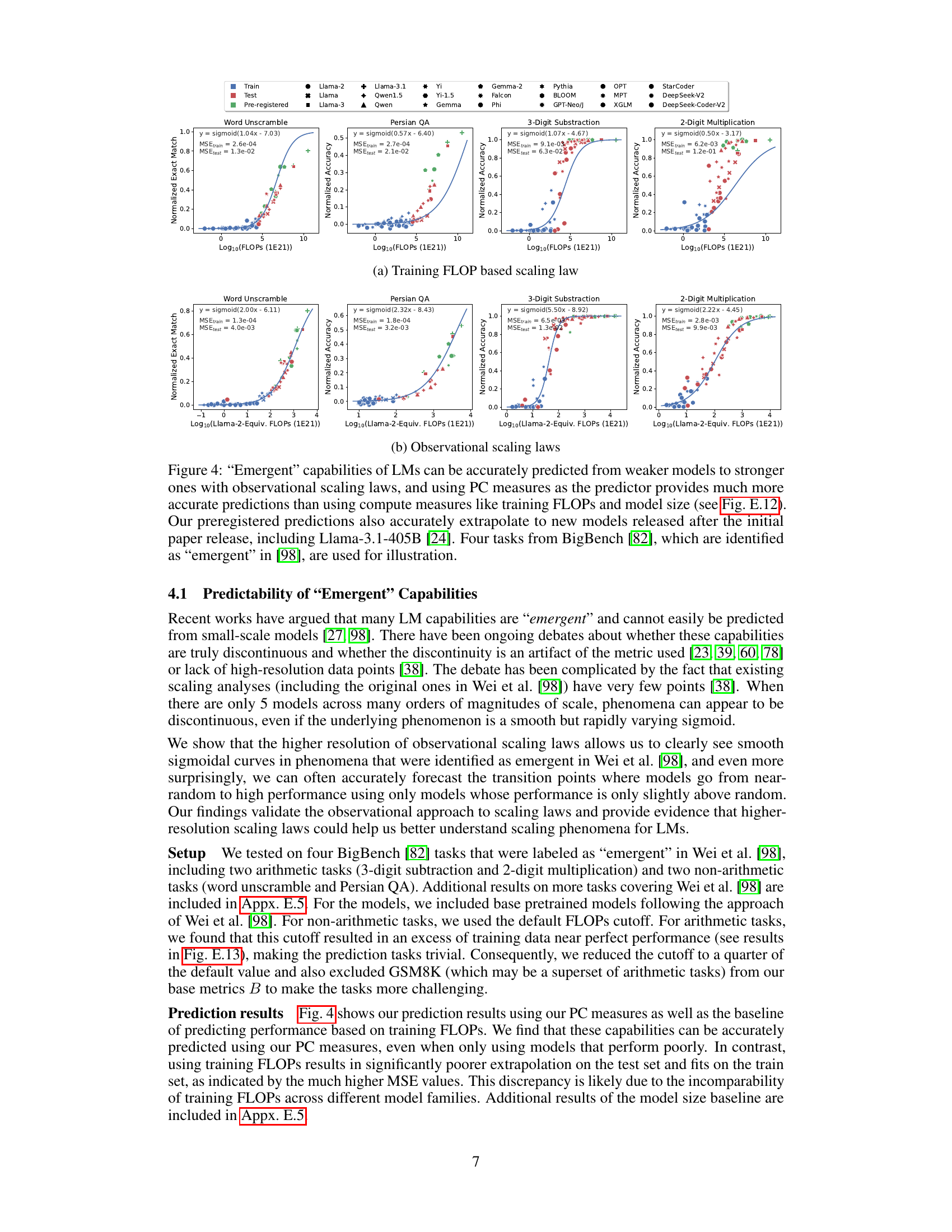

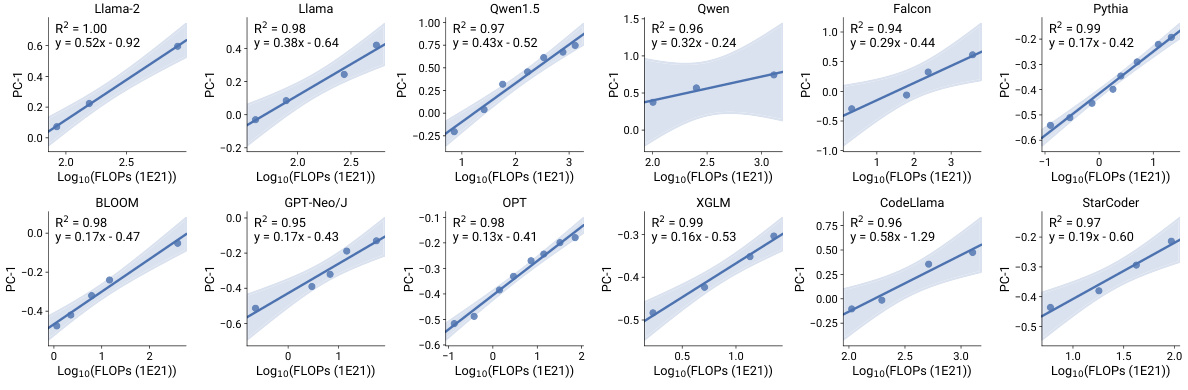

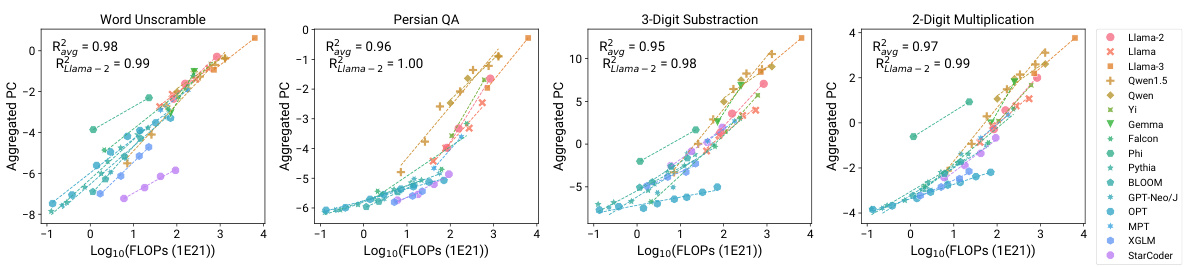

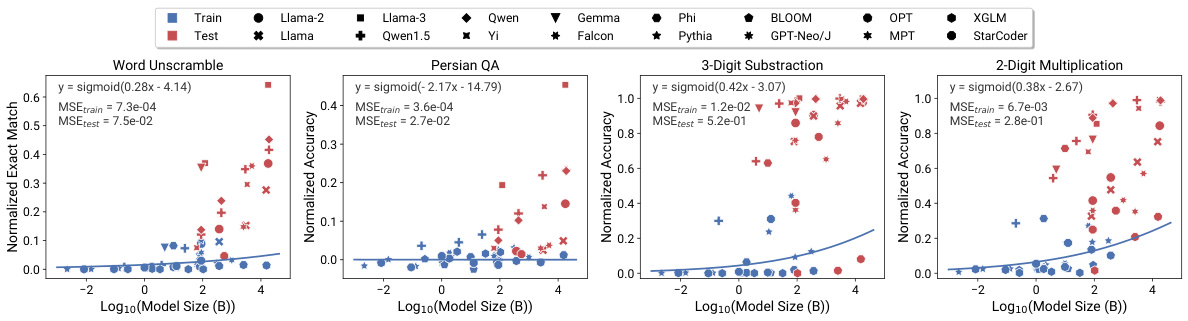

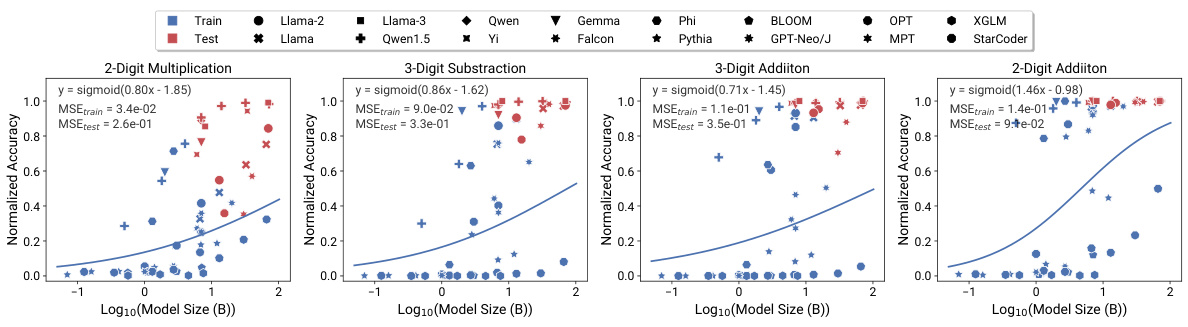

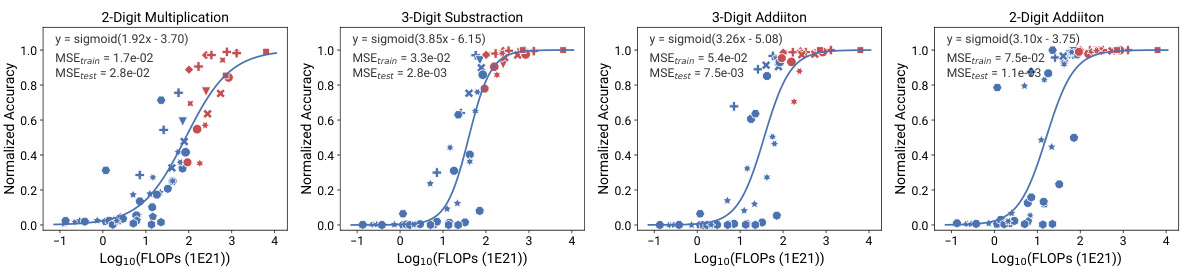

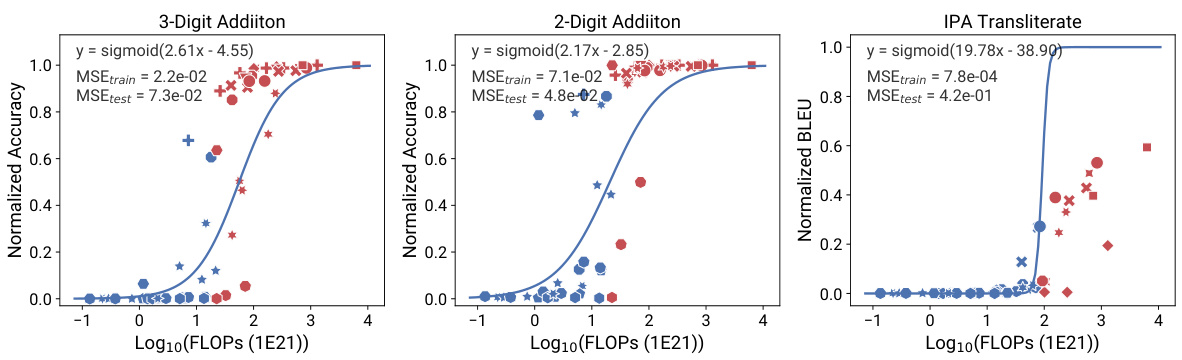

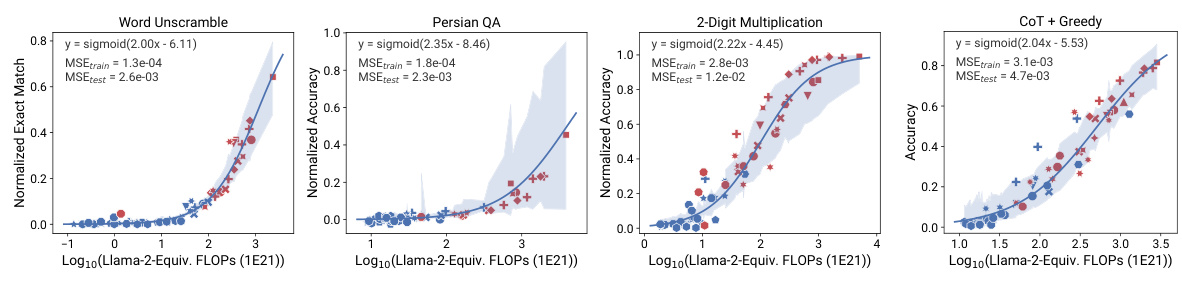

This figure compares the performance of different scaling methods in predicting the emergence of capabilities in large language models (LLMs). It shows that observational scaling laws, using principal component (PC) measures, accurately predict LLM performance across a wide range of model sizes, from weaker to stronger models. The accuracy of predictions from observational scaling laws is significantly higher than that obtained using training FLOPs or model size as predictors. The figure also demonstrates the ability of the proposed method to extrapolate to new models released after the initial study, highlighting the predictive power of the observational scaling laws. Four representative tasks from the BigBench benchmark are used to illustrate this phenomenon.

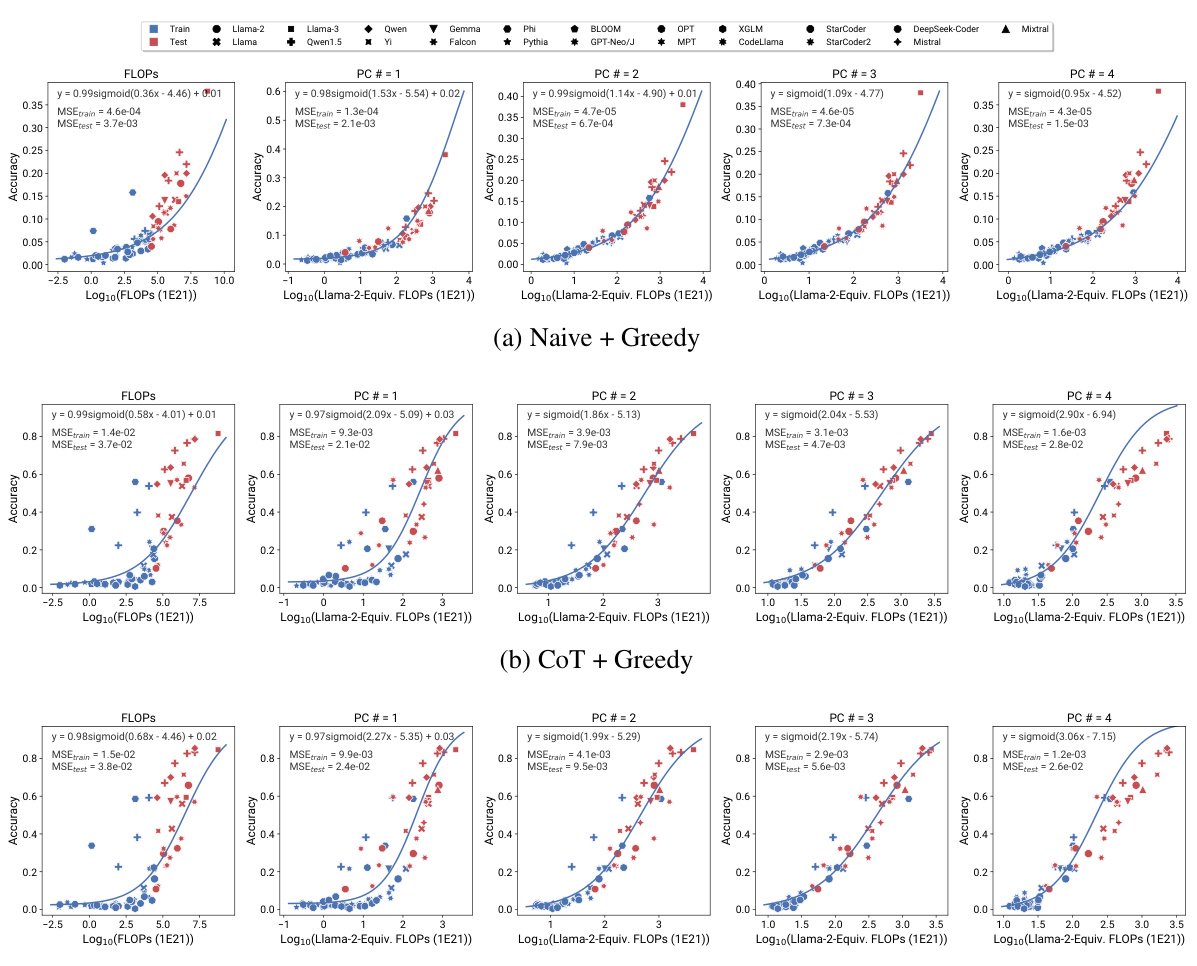

This figure compares the performance of training FLOP based scaling laws and observational scaling laws in predicting the emergent capabilities of large language models. The observational scaling laws, using principal component (PC) measures, show significantly better predictive accuracy than training FLOP based methods, particularly when extrapolating performance to larger models. The results include pre-registered predictions successfully validated on newer models, indicating the robustness of the method.

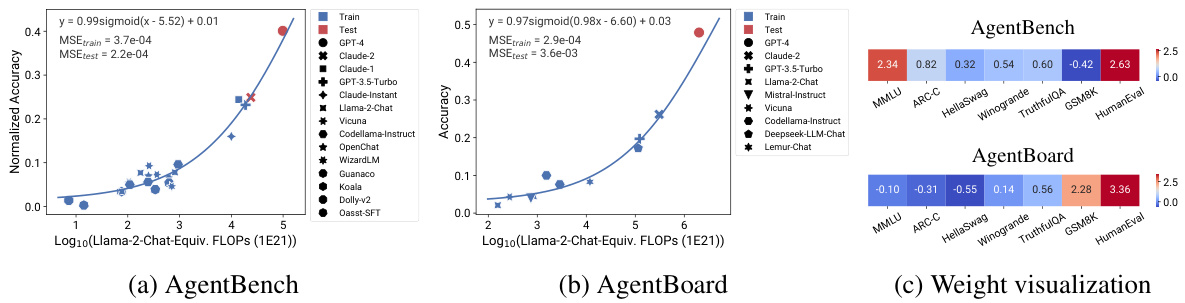

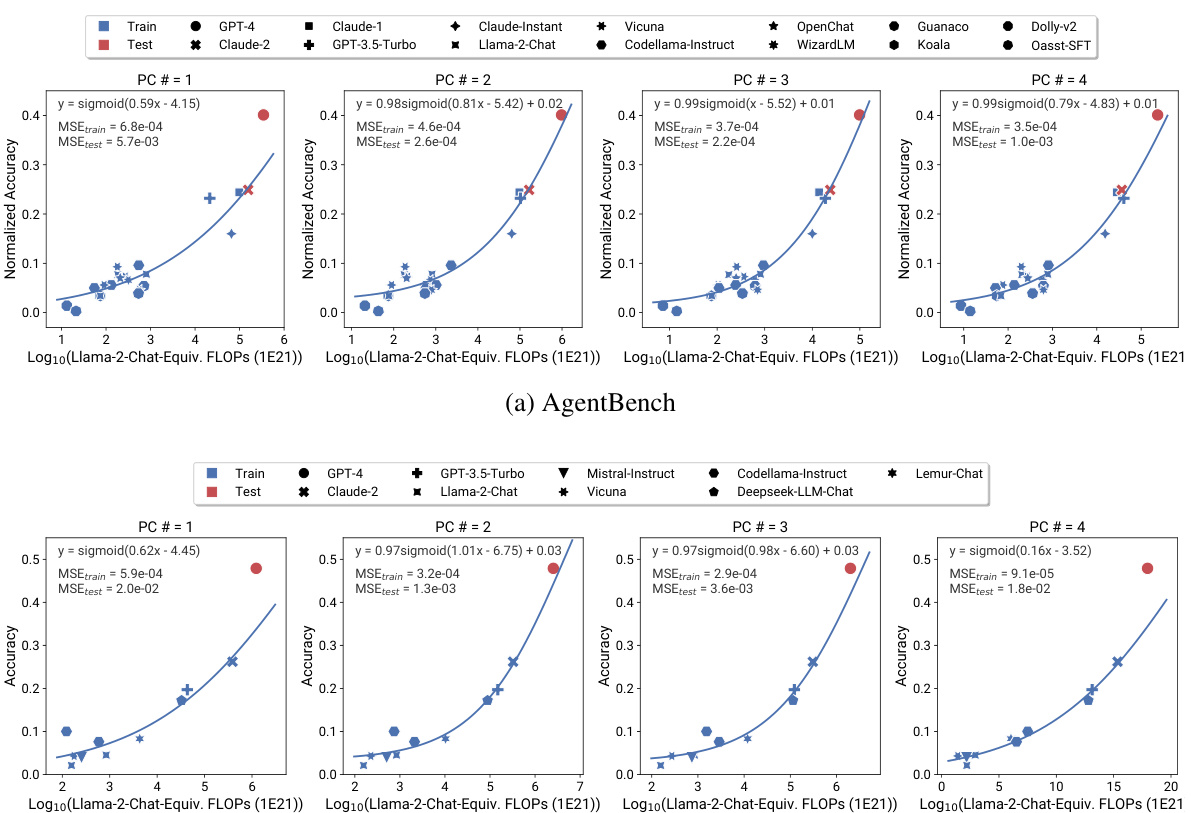

This figure shows that the agentic capabilities of instruction-tuned large language models (LLMs), as measured by AgentBench and AgentBoard, can be accurately predicted using principal component (PC) measures. The plots in (a) and (b) demonstrate the strong correlation between PC measures and agent performance, even extrapolating from weaker models to much stronger models like GPT-4. The weight visualization in (c) highlights the significant contribution of programming capabilities (HumanEval) to overall agentic performance. This suggests that improving programming skills in LLMs may be a key factor in enhancing their agentic abilities.

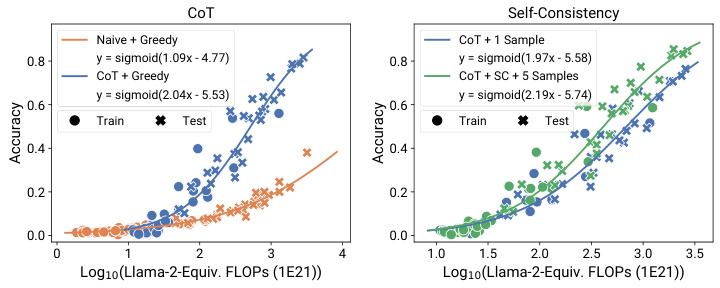

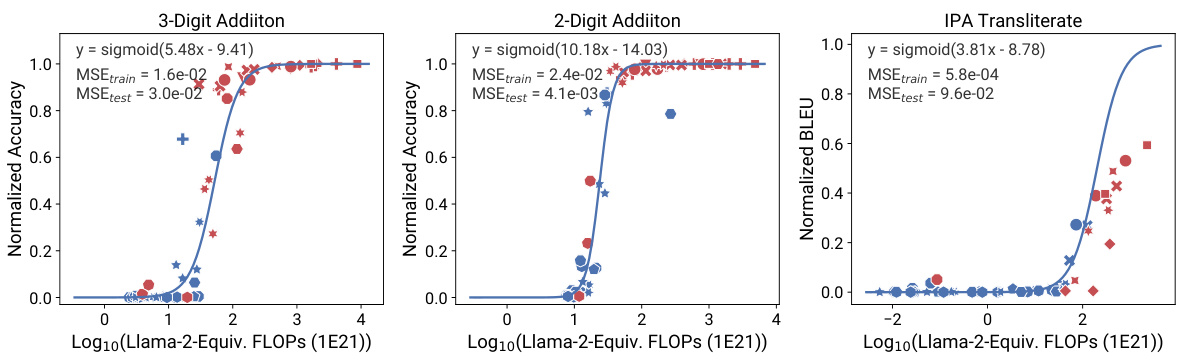

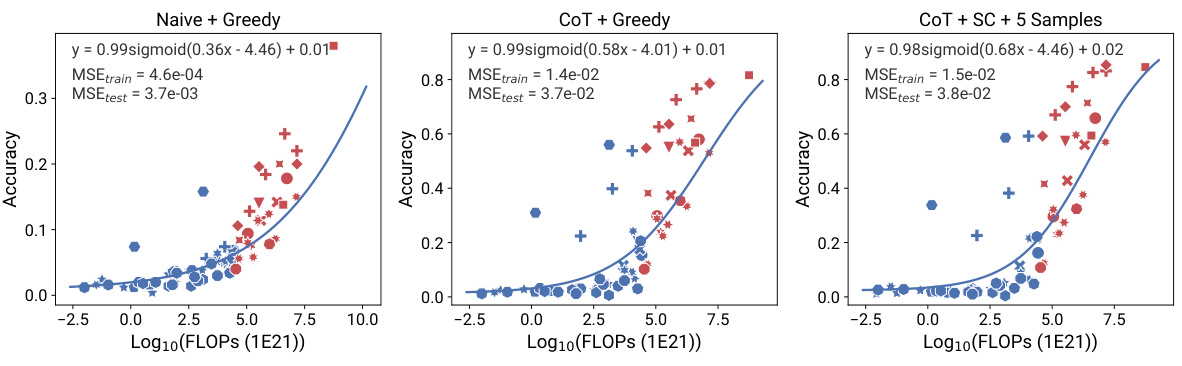

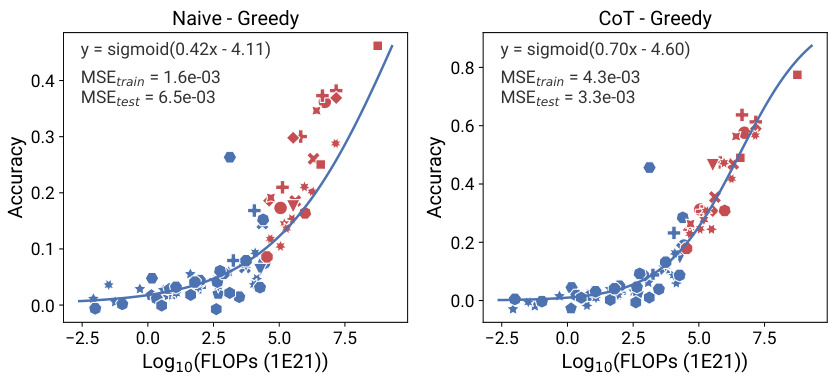

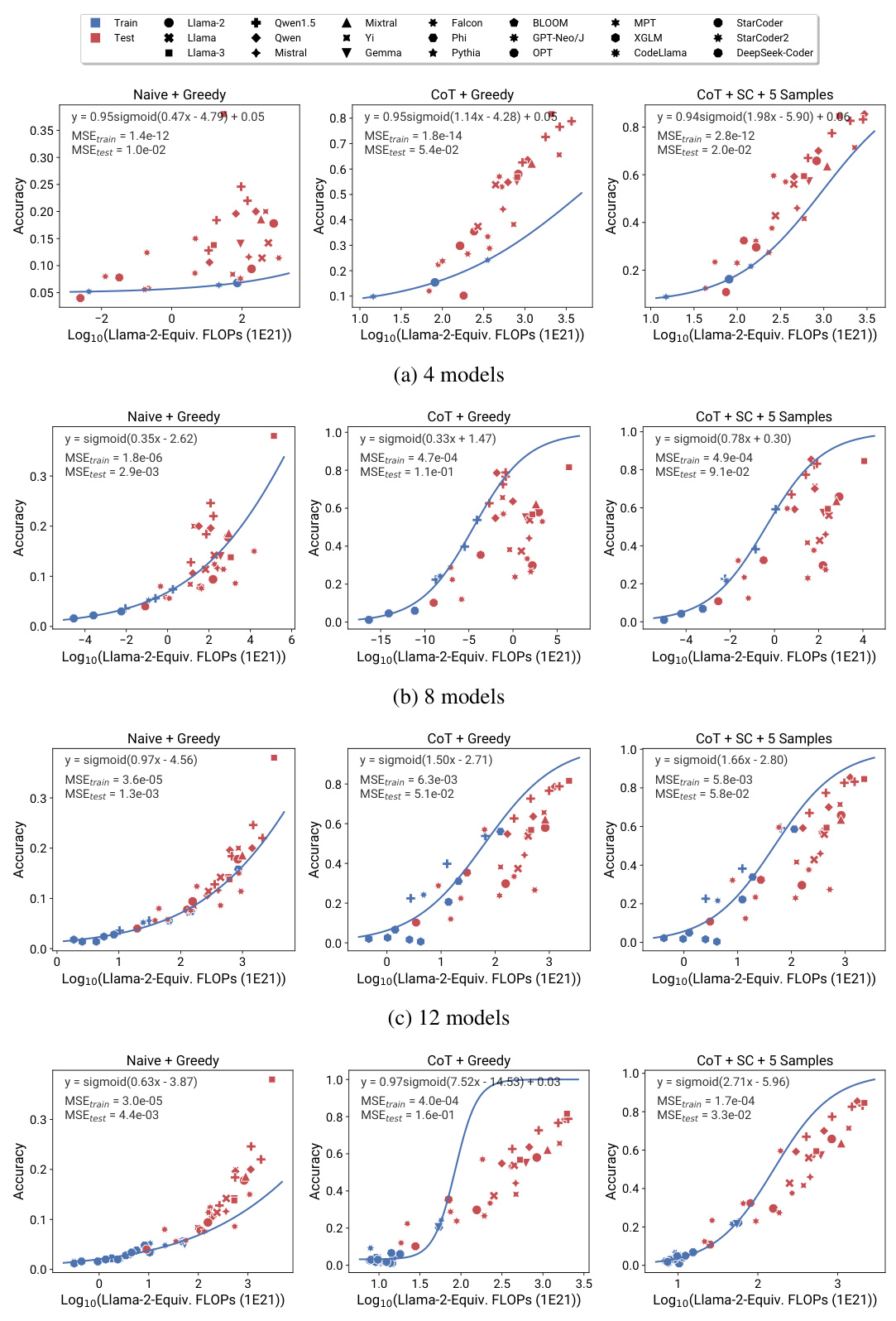

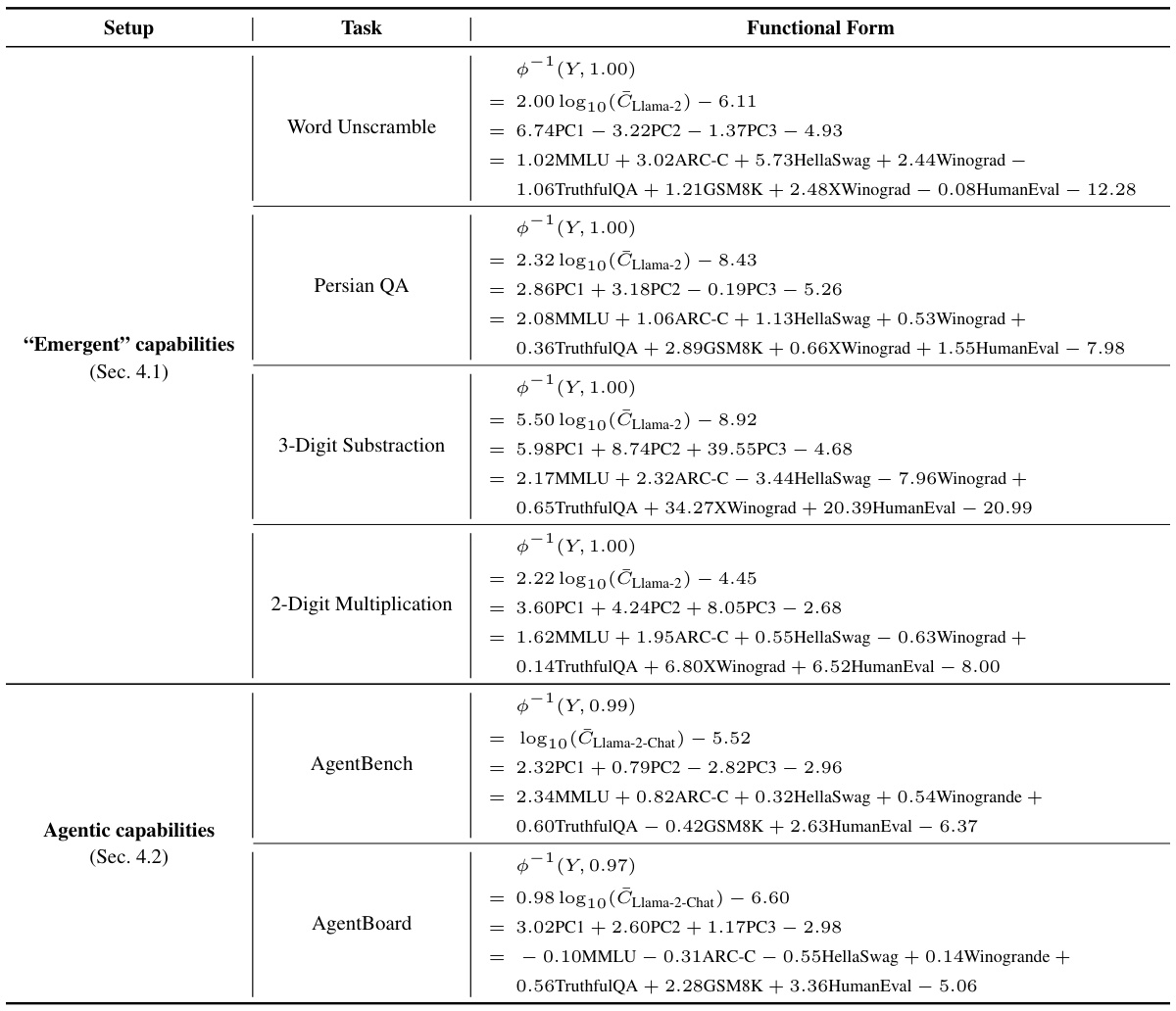

This figure shows the results of applying observational scaling laws to predict the impact of two post-training techniques, Chain-of-Thought (CoT) and Self-Consistency (SC), on language model performance. Panel (a) presents sigmoidal curves showing how accuracy scales with Llama-2 equivalent FLOPs for different methods (naive prompting, CoT, CoT + SC). CoT consistently outperforms naive prompting, and adding self-consistency to CoT offers further improvement. Panel (b) provides a visualization of the relative contribution of different benchmark tasks (MMLU, ARC-C, HellaSwag, Winogrande, TruthfulQA, XWinograd, HumanEval) to the overall capability scores. These contributions vary substantially between the naive and CoT approaches, highlighting the changing nature of language model capabilities as they scale.

This figure shows the results of applying observational scaling laws to predict the impact of post-training techniques (Chain-of-Thought and Self-Consistency) on language model performance. Panel (a) presents sigmoidal curves showing how the performance of language models with and without these techniques scales with a measure of capability. Notably, CoT shows a steeper curve, meaning the technique offers larger gains at higher capabilities. Panel (b) visualizes the weights of different benchmark metrics contributing to the overall capability measure, highlighting that CoT’s success relies more strongly on general knowledge and programming skills compared to the baseline.

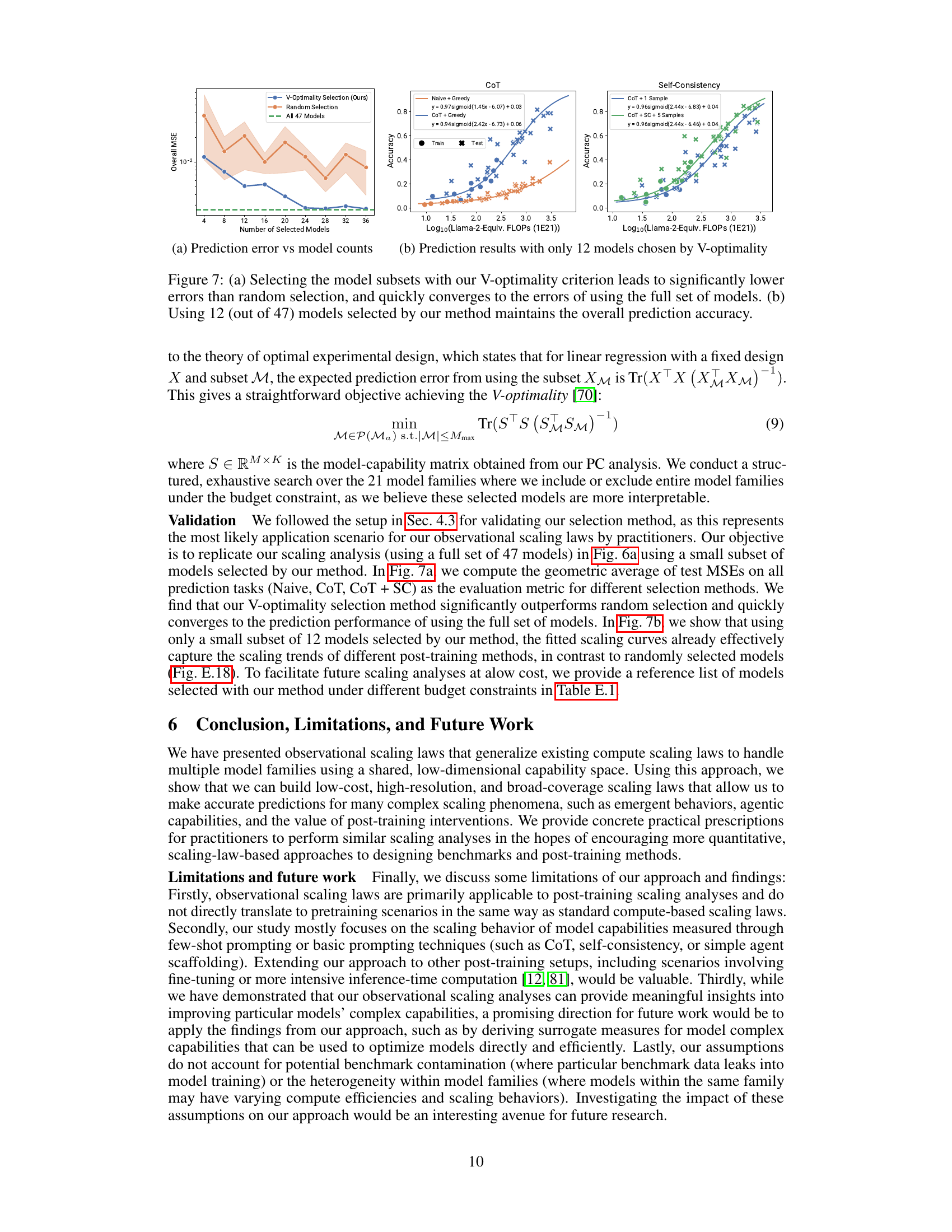

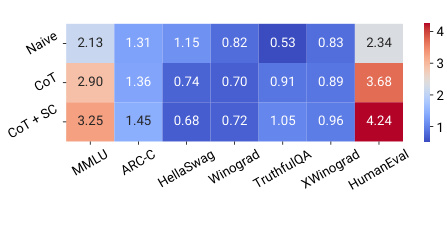

This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of the V-optimality model selection method proposed in the paper. The left panel (a) shows that selecting models based on V-optimality results in significantly lower mean squared error (MSE) compared to random selection, rapidly approaching the MSE obtained when using all 47 models. The right panel (b) shows that using only 12 models selected by the V-optimality criterion still produces prediction accuracy comparable to that achieved with all 47 models. This highlights the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of the proposed selection method.

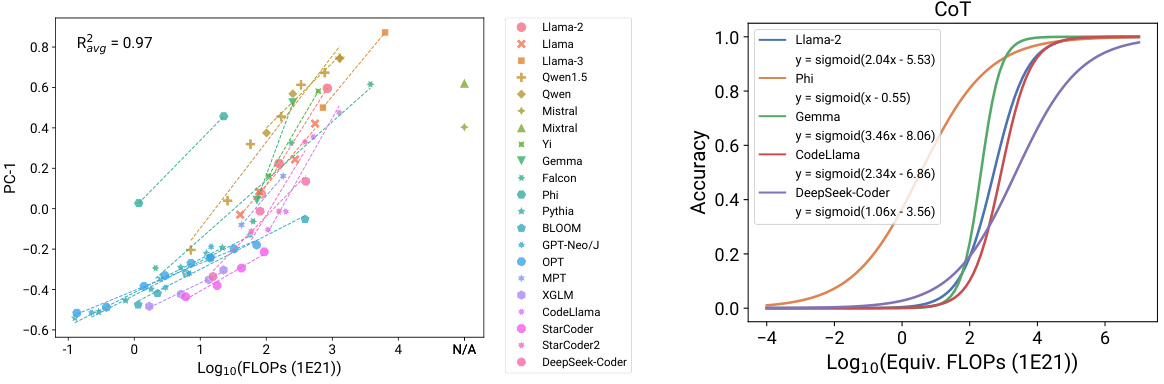

This figure shows the linear relationship between the principal component (PC) measures and the logarithm of the training FLOPs (floating point operations) for different language models. Each line represents a different family of language models. The high R-squared values (R2>0.9) indicate a strong linear correlation, suggesting that the PCs effectively capture the scaling behavior of language models across various model families. The figure visually supports the claim that the PC measures serve as a low-dimensional representation of language model capabilities, with model families differing primarily in their efficiency at converting training compute into these capabilities.

This figure demonstrates that a small number of principal components (PCs) can capture most of the variance in the performance of various language models across a range of standard benchmarks. Panel (a) shows that the top three PCs account for roughly 97% of the variance, indicating a low-dimensional structure underlying the benchmark scores. Panel (b) further reveals the interpretability of these PCs, showing that PC1 reflects general capabilities, PC2 emphasizes reasoning skills (e.g., math and code), and PC3 highlights programming ability. This suggests that language model capabilities, even across different benchmark tasks and model families, can be effectively summarized by a small set of underlying factors.

This figure shows the linear correlation between the principal component (PC) measures and the logarithm of the training FLOPs for different model families. The plots demonstrate a strong linear relationship (R-squared values mostly above 0.94) for each family, indicating that the PCs serve as good surrogates for compute in scaling analysis, even across different model families. The consistency of the linear relationship across multiple model families and PC measures (including lower-ranked PCs, shown in a supplementary figure) supports a low-dimensional representation of language model capabilities.

This figure shows the linear correlation between the principal component (PC) measures and the logarithm of the training FLOPs (floating point operations) for different model families. The plots demonstrate that the PCs, which represent a low-dimensional space of language model capabilities, exhibit a consistent log-linear relationship with compute within each model family. This suggests that the PCs can serve as a useful surrogate for the compute scale, allowing scaling laws to be generalized across different model families. The high R-squared values (R2>0.9) indicate a strong linear fit for most of the model families.

This figure displays the linear correlation between the principal component (PC) measures and the log-training FLOPs for different model families. It visually demonstrates that the PC measures, which represent a lower-dimensional space of LM capabilities, exhibit a consistent log-linear relationship with compute within each model family. This is true even for the lower ranked PCs. The R-squared values are provided for each model family to indicate the strength of the linear relationship.

This figure compares the performance of different language models on four tasks identified as exhibiting ’emergent’ capabilities in a prior study. The left-hand side shows the performance based on training FLOPs, while the right-hand side shows performance based on the observational scaling laws introduced in the paper. The observational scaling laws use principal component analysis (PCA) to capture the underlying capabilities of the models, leading to better predictions than using FLOPs alone. The figure demonstrates the predictability of emergent capabilities across a range of model sizes, including the extrapolation of the model’s performance to new models that were released after the publication of the paper.

This figure compares the performance of observational scaling laws and compute-based scaling laws on three challenging benchmarks from the Open LLM Leaderboard v2: GPQA, MATH Lvl 5, and BBH. The observational scaling laws, which use principal component measures as proxies for model capability, are shown to yield more accurate predictions, especially when extrapolating to larger model sizes, than the compute-based scaling laws that rely directly on training FLOPs.

This figure shows the comparison of observational and compute-based scaling laws on three new benchmarks from Open LLM Leaderboard v2: GPQA, MATH, and BBH. Observational scaling laws, using principal component measures, show better extrapolation performance on these more challenging benchmarks compared to those using training FLOPs or model size.

This figure shows the linear correlation between the top principal component (PC) measures and log-training FLOPs within each model family. The R-squared values (R2) are displayed for each family, indicating the goodness of fit of the linear regression model. The figure demonstrates the consistency of the log-linear relationship between compute and capabilities across various model families, supporting the hypothesis that model families primarily vary in their efficiency at transforming training compute into capabilities, rather than inherent differences in capabilities.

This figure compares the predictability of ’emergent’ capabilities using different scaling methods. It shows that observational scaling laws using principal component (PC) measures are more accurate than using training FLOPs or model size. The figure also demonstrates the accuracy of preregistered predictions in extrapolating to newer, larger models.

This figure demonstrates that the agentic capabilities of instruction-tuned large language models (LLMs), as measured by AgentBench and AgentBoard, can be accurately predicted using principal component (PC) measures. The plots show a strong correlation between PC measures (representing a low-dimensional space of LLM capabilities) and the performance of various models on agentic tasks, even extrapolating from weaker models to stronger ones like GPT-4. Furthermore, the weight visualization highlights the importance of programming capabilities (HumanEval) in driving agent performance.

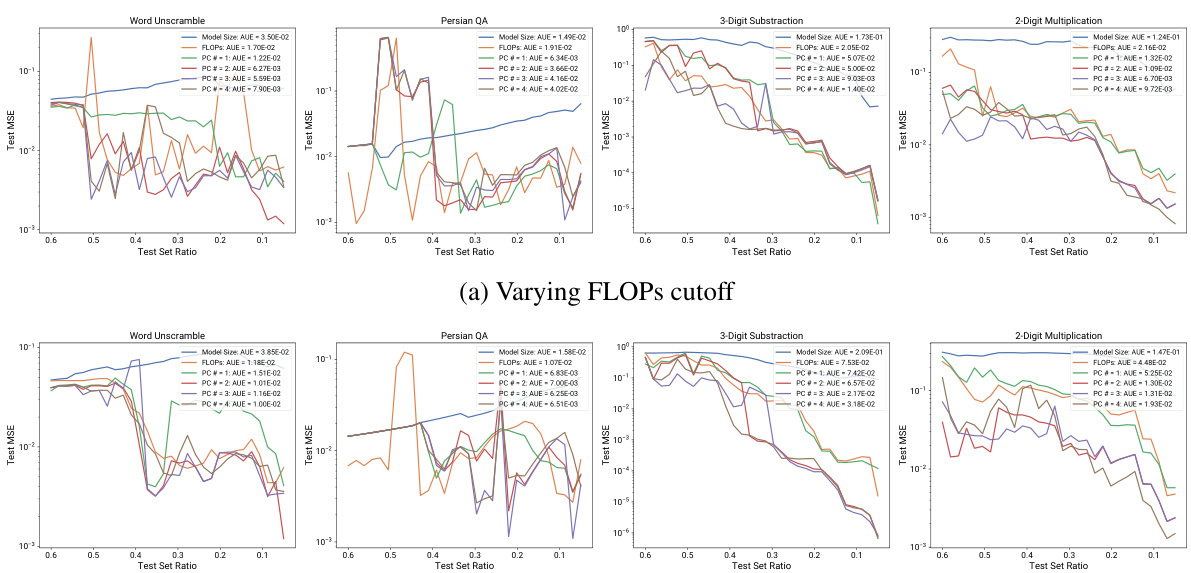

This figure compares the performance of different scaling measures (model size, FLOPs, and PCs with varying numbers of principal components) on post-training analysis tasks under various holdout cutoffs. The area under the test error curve (AUE) is used to summarize the overall prediction performance. The results show that PC measures (using 2 or 3 components) consistently achieve lower AUE and transition to low prediction error regions sooner compared to model size and FLOPs, indicating superior robustness and efficiency.

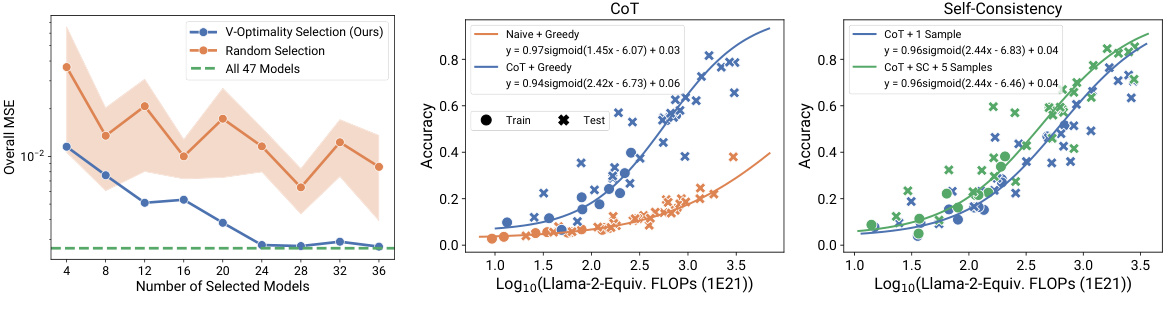

This figure shows the limitations of using single benchmark metrics to assess language model capabilities. Some metrics, such as HellaSwag and Winogrande, quickly reach saturation with larger models, while others like MMLU and GSM8K may produce random results for smaller models. This illustrates the importance of using multiple metrics and considering the model’s size and compute resources to gain a comprehensive understanding of its capabilities.

This figure demonstrates the predictability of emergent capabilities in large language models using observational scaling laws. The top row shows predictions based on training FLOPs, highlighting the inaccuracy of this approach, especially when extrapolating to larger models. The bottom row displays significantly improved accuracy achieved using observational scaling laws with principal component (PC) measures as predictors. The plot shows four tasks from the BigBench benchmark, chosen because they were identified as exhibiting emergent capabilities. The preregistered predictions successfully extend to new models released after the initial paper.

This figure shows the prediction performance using model size for emergent capabilities. It demonstrates that using model size leads to significantly worse forecasts compared to using training FLOPs and PC measures, and fails to capture the emergent trend. This is because models from different families were trained with very different data sizes and quality and may use different architectures.

This figure compares the performance of different language models on four tasks identified as exhibiting ’emergent’ capabilities in previous research. It shows that observational scaling laws using principal component (PC) measures as predictors accurately forecast model performance across a wide range of compute scales. The predictions based on PC measures are substantially more accurate than those based on training FLOPs or model size, highlighting the value of the observational scaling laws. Furthermore, preregistered predictions made prior to the release of certain models were still accurate, demonstrating the predictive power of this approach.

This figure shows the results of using the default FLOPs cutoff on arithmetic tasks for emergent capabilities. It compares the prediction performance of observational scaling laws (using PC measures) against model size and training FLOPs. Even with many data points exhibiting near-perfect performance, the observational approach using PC measures is shown to be more effective than using other simpler metrics.

This figure compares the prediction performance of using model size for the ’emergent’ capabilities of LMs against using training FLOPs and PC measures. It shows that model size leads to significantly worse forecasts and poorly captures the emergence trend. This is attributed to the fact that models from different families were trained with varying data sizes, quality, and architectures.

This figure shows the results of applying observational scaling laws and two baseline methods (model size and training FLOPs) to four tasks from Wei et al. [98]. These tasks were selected as examples of capabilities exhibiting emergent behavior. The observational scaling law accurately predicts the performance trend from weak to strong models. Both model size and training FLOPs fail to make accurate predictions for the selected tasks. The figure shows that the observational scaling laws predict the performance on tasks with emergent capabilities more accurately than the other baseline methods.

This figure shows the limitations of using single benchmark metrics to evaluate language model capabilities across different scales. The figure demonstrates that some metrics (e.g., HellaSwag, Winogrande) saturate quickly as model size increases, while others (e.g., MMLU, GSM8K) show near-random performance for smaller models. This highlights the need for a more comprehensive approach to evaluating LM capabilities across scales, such as the observational scaling laws proposed in the paper.

This figure demonstrates the accuracy of observational scaling laws in predicting the emergence of capabilities in large language models. It compares predictions made using the principal component (PC) measures against predictions using training FLOPs and model size. The results show that PC measures yield significantly more accurate predictions, especially when extrapolating to larger, more capable models. The figure includes preregistered predictions made before the release of the paper which were subsequently validated with new models, showcasing the predictive power of the observational scaling laws.

This figure compares the performance of different language models on four tasks identified as ’emergent’ in previous research. It showcases how observational scaling laws, using principal component measures (PCs), accurately predict the performance of larger, more capable models based on the performance of smaller models. The figure demonstrates that the PCs are superior predictors compared to using traditional compute metrics such as training FLOPs and model size. Furthermore, the predictions of the observational method successfully generalize to newly released models.

This figure demonstrates the accuracy of observational scaling laws in predicting the emergence of LMs’ capabilities compared to using training FLOPs or model sizes. The left panels show the sigmoidal curves fitting training FLOPs and the right panels show the ones fitting observational scaling laws. It also shows the extrapolation of the model performance to new models that were not included during the training process.

This figure compares the performance of two different scaling law approaches for predicting the emergent capabilities of large language models (LLMs). It evaluates four tasks from the BigBench benchmark that are considered to exhibit emergent behavior. The first approach uses training FLOPs as a predictor variable, while the second utilizes principal components (PCs) derived from multiple standard LMs benchmarks. The results demonstrate the superiority of the PC-based approach in accurately forecasting the transition point where the models start exhibiting high performance. The PC-based approach also successfully predicts the performance of newer, more powerful LMs.

This figure shows the results of applying observational scaling laws to predict the impact of Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting on the BigBench-Hard (BBH) benchmark. It compares the predictive accuracy of using training FLOPs versus PC measures. The results suggest that while both measures provide reasonable predictions, PC measures more accurately capture the scaling trends, particularly in cases where using training FLOPs alone is less effective (e.g., the ‘Naive’ setup and the Phi model, trained on synthetic data).

This figure demonstrates the accuracy of observational scaling laws in predicting the ’emergent’ capabilities of large language models (LLMs). It compares the predictions of LLMs’ performance on four tasks from BigBench using training FLOPs and principal component (PC) measures as predictors. The results show that PC measures provide significantly more accurate predictions than training FLOPs, especially when extrapolating from weaker to stronger models. Furthermore, it highlights the predictive power of the method even for newly released models.

This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of observational scaling laws in predicting the emergent capabilities of LLMs. It compares predictions made using traditional training FLOP-based scaling laws against those using observational scaling laws based on principal component measures (PCs). The results show that observational scaling laws, particularly those using PCs, provide significantly more accurate extrapolations of performance from weaker to stronger models, even for newly released models not present in the original training data. The emergent capabilities are tested on four tasks selected from the BigBench dataset.

This figure compares the predictive performance of training FLOP-based scaling laws and observational scaling laws using PC measures for predicting the ’emergent’ capabilities of LLMs on four different tasks. The results show that observational scaling laws with PC measures produce more accurate predictions, especially when extrapolating to larger models, than FLOP-based scaling laws. The accuracy of the preregistered predictions further demonstrates the reliability and generalizability of the model.

This figure shows the linear correlation between the principal component (PC) measures and the logarithm of the compute (log-compute) for different model families. The results demonstrate that PC measures, representing model capabilities, increase linearly with log-compute within individual model families, indicating consistent scaling behavior. The consistent linear relationship holds even for lower-ranked principal components (shown in Figure E.2 in the appendix), which further supports the robustness and generalizability of the observational scaling law.

This figure compares the performance prediction of ’emergent’ capabilities using different methods: training FLOP based scaling law and observational scaling law. The observational scaling law uses principal component (PC) measures as predictors, showing significantly more accurate predictions on both training and test sets, compared to the training FLOP based method. The result also extends to new models released after the initial paper release, demonstrating the model’s capability to extrapolate performance based on the PC measures. The four tasks shown in the figure are sampled from BigBench and identified as ’emergent’ in previous studies. This figure validates the effectiveness and generalizability of the observational scaling law in predicting complex capabilities of language models.

This figure displays the performance of different Language Models (LMs) across various benchmarks. It highlights the limitation of using a single benchmark metric, as some metrics saturate at high performance levels while others provide unreliable scores at low performance. This indicates the need for a more comprehensive set of metrics to capture the full range of LM capabilities.

This figure demonstrates the predictability of ’emergent’ capabilities of large language models (LLMs) using observational scaling laws. The figure compares the performance of training FLOP based scaling laws versus observational scaling laws on four tasks (Word Unscramble, Persian QA, 3-Digit Subtraction, 2-Digit Multiplication) from the BigBench benchmark. Observational scaling laws, which utilize principal component (PC) measures, provide significantly more accurate predictions of LLM performance than using compute measures like training FLOPs and model size. This accuracy extends to newly released models that were not part of the original model set used to create the scaling law, highlighting the generalizability of the approach. The high resolution of observational scaling laws reveals the smooth sigmoidal behavior of emergent capabilities, which were previously considered discontinuous.

More on tables

This table presents the metadata and base evaluation metrics for the pretrained base models used in sections 4.1, 4.3, and 5 of the paper. The metadata includes parameters, data size, and FLOPs (floating point operations). The evaluation metrics cover several benchmarks: MMLU (Massive Multitask Language Understanding), ARC-C (AI2 Reasoning Challenge), HellaSwag (Commonsense Reasoning), Winograd Schema Challenge, TruthfulQA (Truthfulness), XWinograd (Multilingual Commonsense), and HumanEval (Programming). Model names follow the HuggingFace naming convention. For the most current results, consult the provided GitHub link.

This table presents the metadata and evaluation results for 77 pretrained base language models used in sections 4.1, 4.3, and 5 of the paper. The metadata includes the number of parameters, the amount of training data, and the estimated training FLOPs. The evaluation metrics include scores from several standard benchmarks assessing general capabilities, reasoning, and programming skills. The table also specifies the model family and model name following the HuggingFace naming convention. A link is provided for the most up-to-date results.

This table presents the metadata and evaluation results for the pretrained base language models used in sections 4.1, 4.3, and 5 of the paper. It includes information such as the model family, model name, number of parameters, data size, training FLOPs, and performance scores on various standard benchmarks (MMLU, ARC-C, HellaSwag, Winograd, TruthfulQA, XWinograd, HumanEval). The data collection process is detailed in Appendix D.1.1, and a link to the most up-to-date results is provided.

This table presents a comprehensive overview of the metadata and baseline evaluation metrics for various pretrained language models used in different sections of the research paper. It includes information such as model family, model name, number of parameters, data size, training FLOPs, and performance scores on several standard benchmarks (MMLU, ARC-C, HellaSwag, Winogrande, TruthfulQA, XWinograd, HumanEval). The table facilitates a detailed comparison of various models across different scales and capabilities.

Full paper#