↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models’ training often relies on the Adam optimizer due to its superior performance compared to Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD). However, the reasons behind this performance gap remain unclear. This paper investigates this gap focusing on the characteristics of language data, which exhibits a significant class imbalance problem. Many words appear infrequently, leading to a disproportionate impact on the loss function. This imbalance makes it difficult for SGD to converge efficiently.

The researchers demonstrate that this heavy-tailed class imbalance is the root cause for slower convergence with SGD. They show that Adam and sign-based methods are less sensitive to this problem. Through experiments and theoretical analysis, they demonstrate that this imbalance creates imbalanced, correlated gradients and Hessians, which Adam is able to handle more effectively. The findings highlight the importance of considering data characteristics, particularly class imbalance, when designing and analyzing optimization algorithms. This research has significant implications for improving training efficiency and developing new optimizers tailored for data with heavy-tailed class imbalances, common in many real-world applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it identifies heavy-tailed class imbalance as a key factor in the superior performance of Adam over SGD in large language models. This sheds light on a previously unclear optimization challenge and opens avenues for developing new optimizers specifically tailored for imbalanced data, which is prevalent in many machine learning applications.

Visual Insights#

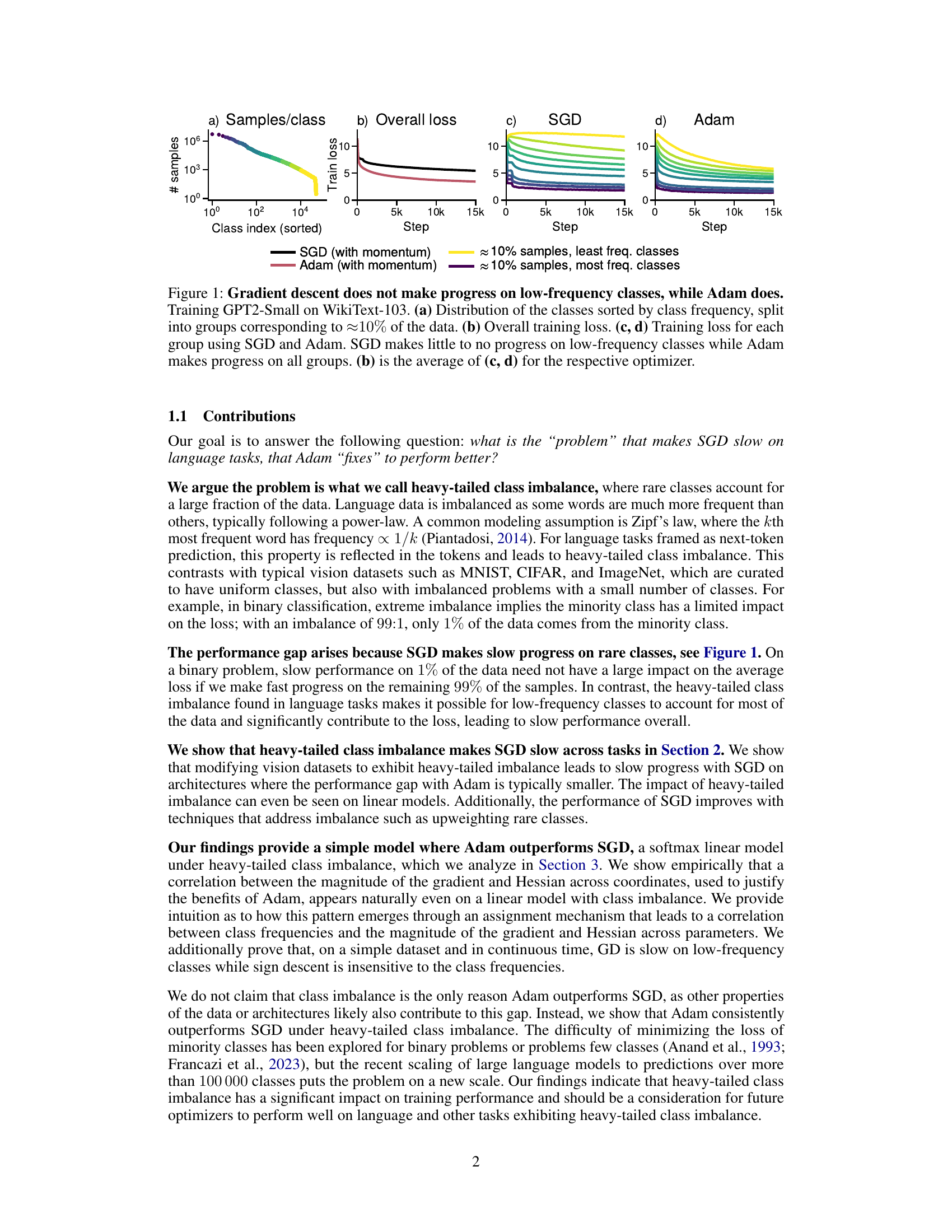

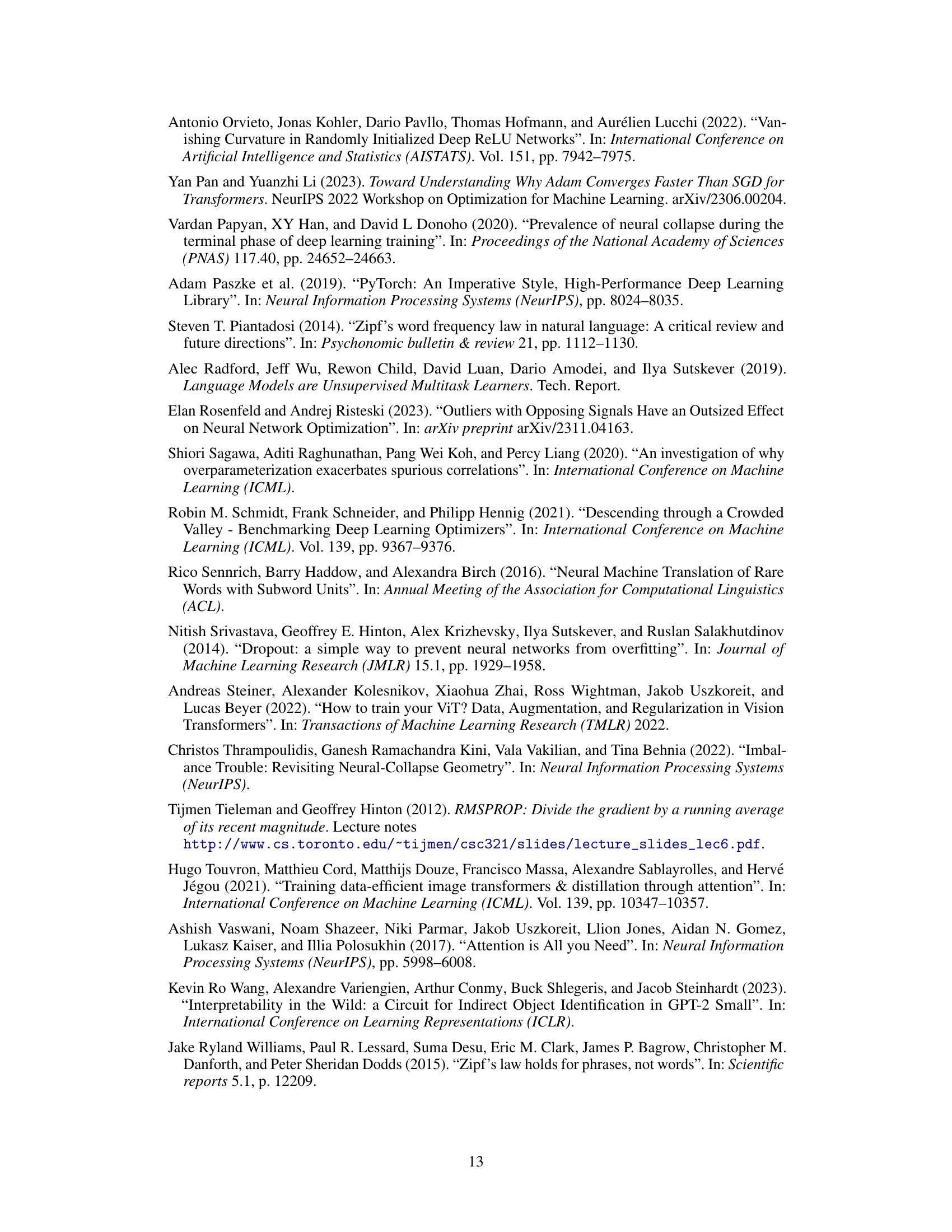

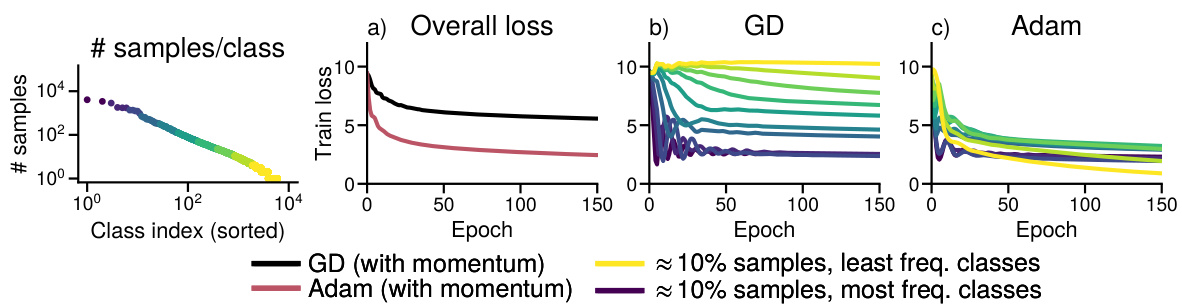

The figure visualizes the training performance difference between Adam and SGD optimizers on the GPT2-Small language model trained on the WikiText-103 dataset. It demonstrates that while Adam consistently reduces the training loss across all classes (including low-frequency ones), SGD struggles to make significant progress on low-frequency classes. This is shown via the distribution of samples per class, overall training loss, and the training loss for various frequency class groups.

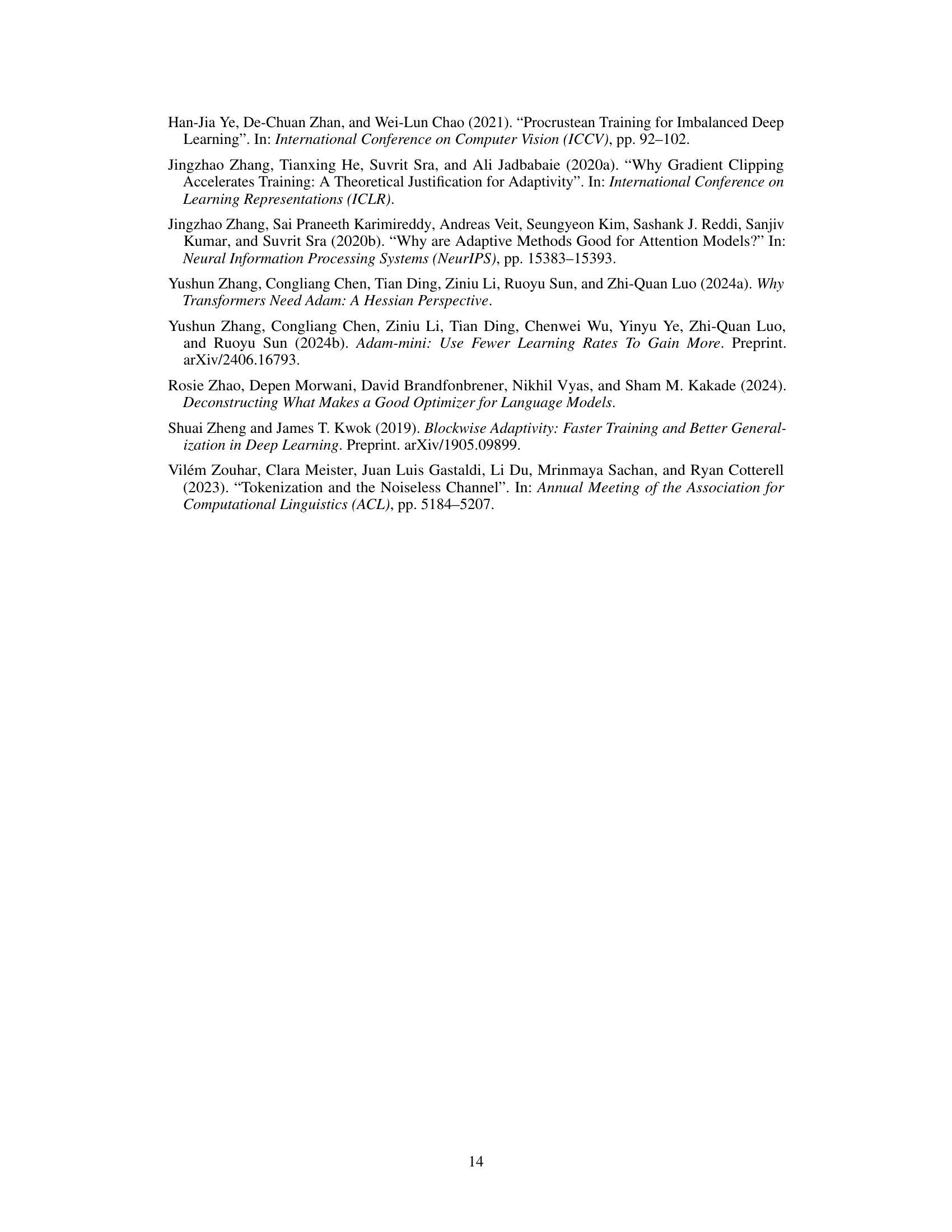

This table summarizes the models, datasets, and batch sizes used in the experiments presented in the paper. It aids in understanding the experimental setup and the different configurations used for evaluating the performance of various optimizers on different tasks and model architectures.

In-depth insights#

Adam’s edge in LLMs#

The research paper explores the reasons behind Adam optimizer’s superior performance over traditional gradient descent in training large language models (LLMs). A key insight is the presence of heavy-tailed class imbalance in language data, where some words are far more frequent than others. Gradient descent struggles with this imbalance, exhibiting slow convergence for infrequent words. Adam, however, displays more resilience to this issue and thus achieves better overall performance. The paper further examines this effect across various architectures and datasets, offering empirical evidence and a theoretical analysis using linear models to solidify this claim. Crucially, the authors show that imbalanced gradients and Hessians, a phenomenon frequently observed in LLMs, also contribute to Adam’s advantage. This is further corroborated by theoretical analysis of continuous time gradient descent. The paper provides a significant step in understanding Adam’s effectiveness specifically within the context of LLMs, highlighting the role of data characteristics in optimization.

Heavy-tailed imbalance#

The concept of “heavy-tailed class imbalance” in the context of large language models (LLMs) training is crucial. It highlights that the distribution of classes (e.g., words, tokens) in LLMs training data often follows a power-law distribution, where a few frequent classes dominate while many infrequent classes are under-represented. This imbalance makes training challenging because the optimization algorithms spend disproportionate time on frequent classes and neglect infrequent ones, leading to slow convergence and suboptimal performance. Gradient Descent (GD), a common optimization method, is shown to struggle with heavy-tailed imbalance, particularly due to slow progress on infrequent classes, which contribute significantly to the overall loss, especially in LLMs where the number of classes can easily reach hundreds of thousands. This issue is ameliorated by algorithms like Adam, that can handle imbalanced, correlated gradients and Hessians, which are inherent to heavy-tailed class imbalance. Adam’s resilience to this problem comes from its adaptive learning rates and momentum, which help to equalize updates across parameters, thereby addressing the class imbalance issue more effectively than GD. Therefore, understanding and mitigating heavy-tailed class imbalance is critical for better training of LLMs, and finding new optimizers or modifications to existing ones to deal with this issue remains an active area of research.

SGD’s slow convergence#

The paper investigates why the Adam optimizer outperforms Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) on large language models. A core argument is that SGD struggles with heavy-tailed class imbalance, a characteristic of language data where infrequent words or tokens significantly impact the overall loss function. The paper demonstrates that SGD’s progress slows considerably on low-frequency classes, unlike Adam which is less sensitive to this imbalance. This difference is attributed to how SGD updates are directly proportional to the magnitude of gradients, which are skewed by the imbalance, whereas Adam’s updates are less susceptible due to its inherent mechanisms such as momentum and adaptive learning rates. The authors provide theoretical and empirical evidence across multiple architectures and datasets showing that heavy-tailed class imbalance is a key factor in the performance gap, particularly in the context of high-dimensional data. This is further supported by analysis on simplified models, suggesting that correlated, imbalanced gradients and Hessians are at play and that continuous-time sign descent, a simplified Adam, converges considerably faster than gradient descent on low-frequency classes. In essence, the paper highlights a crucial interaction between optimization algorithms and data properties, emphasizing the need for algorithm design that accounts for heavy-tailed class imbalance inherent in many real-world datasets.

Linear model analysis#

Analyzing a linear model in the context of a research paper focusing on heavy-tailed class imbalance and optimizer performance offers valuable insights. A linear model, while simplistic, provides a powerful tool to isolate the impact of class imbalance from complexities introduced by neural network architectures. By examining gradient and Hessian dynamics in this simplified setting, we can determine whether the observed performance gap between optimizers like Adam and SGD is solely attributable to imbalance or influenced by other factors inherent in larger models. The analysis of gradients and Hessians reveals the potential for correlations between these quantities and class frequencies, a key factor affecting optimizer efficiency. This analysis might show that Adam’s resilience to heavy-tailed class imbalance stems from its ability to navigate correlated gradients and Hessians, whereas SGD is less effective due to slower convergence on low-frequency classes. Ultimately, the linear model analysis serves as a crucial proof-of-concept, strengthening the core argument of the research paper. Analytical results obtained using a linear model offer a verifiable explanation for the phenomena observed, supporting conclusions that may extend to more complex, real-world scenarios.

Sign descent’s speed#

Sign descent, a simplified version of Adam, offers valuable insights into the optimization dynamics of large language models. Its key advantage lies in its insensitivity to class frequencies, unlike gradient descent which struggles with heavy-tailed class imbalances prevalent in language data. This speed advantage stems from the fact that sign descent updates are independent of the class frequencies, unlike gradient descent updates which are directly influenced by the magnitude of gradients scaled by class frequencies, thus leading to slower convergence on low-frequency classes. The theoretical analysis proves this speed advantage in continuous time, showcasing sign descent’s superior convergence rate compared to gradient descent on imbalanced datasets. This finding highlights a crucial aspect of Adam’s success: its ability to approximate sign descent’s behavior, thereby mitigating the negative impact of imbalanced data on optimization speed. The robustness of sign descent to class imbalance is a key factor in explaining Adam’s superior performance on language modeling tasks compared to standard gradient descent algorithms.

More visual insights#

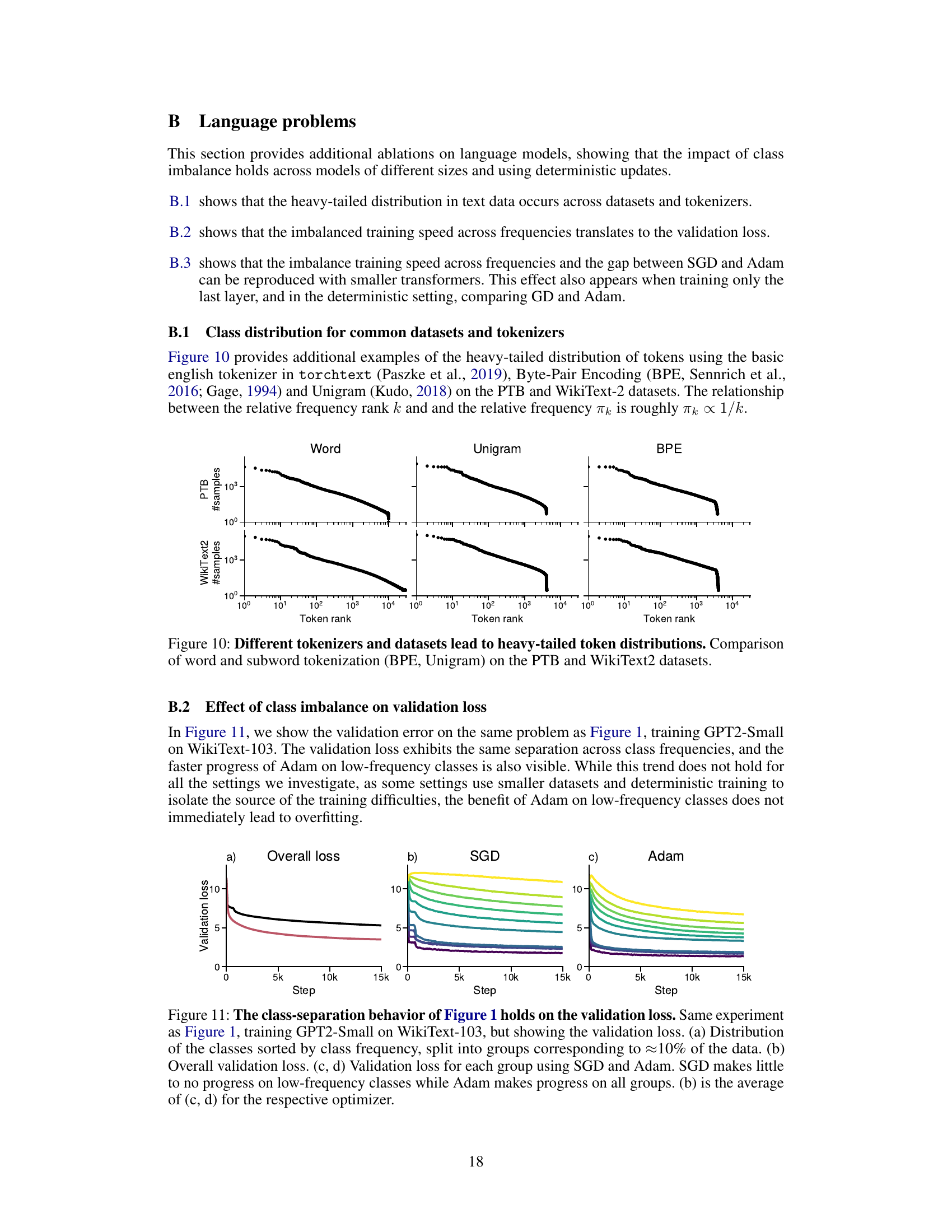

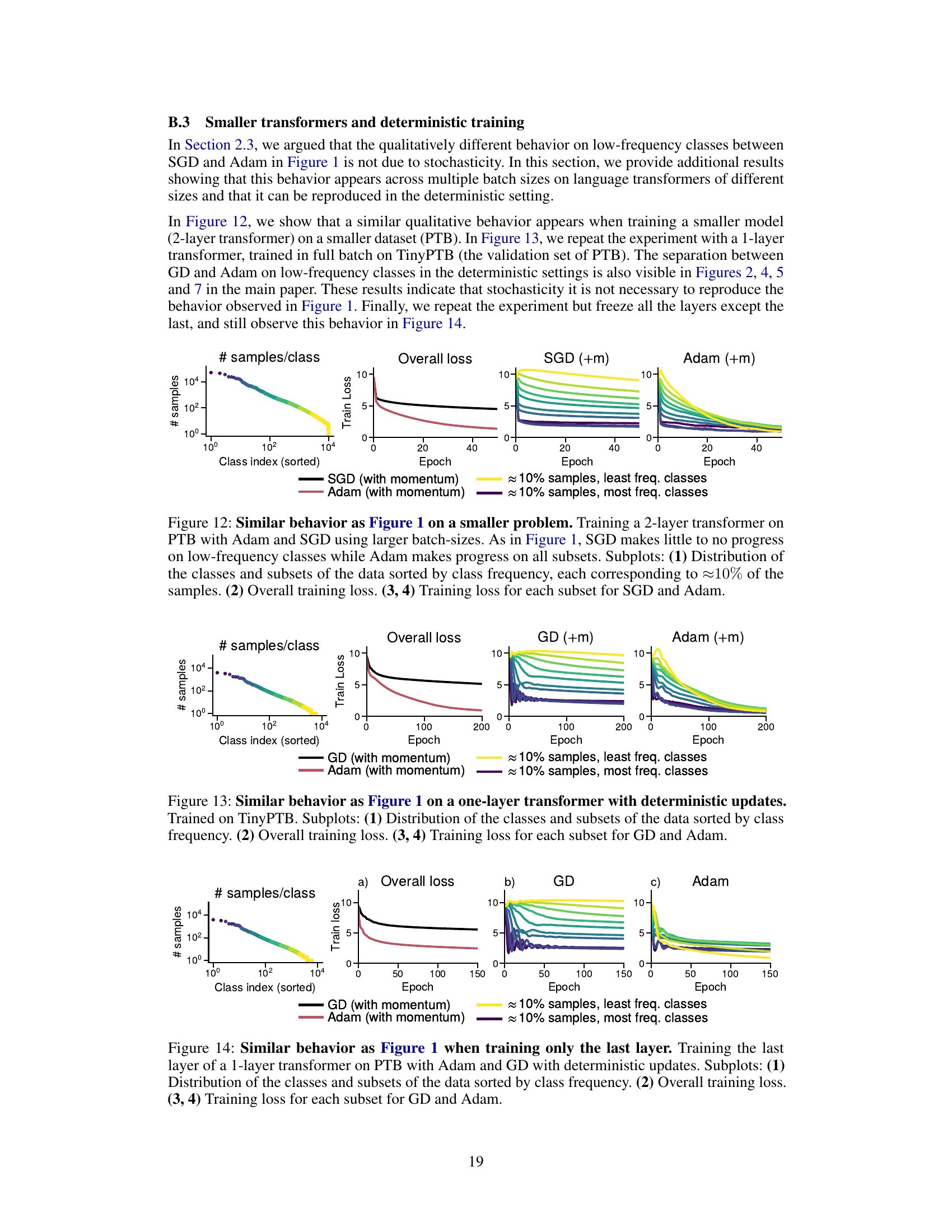

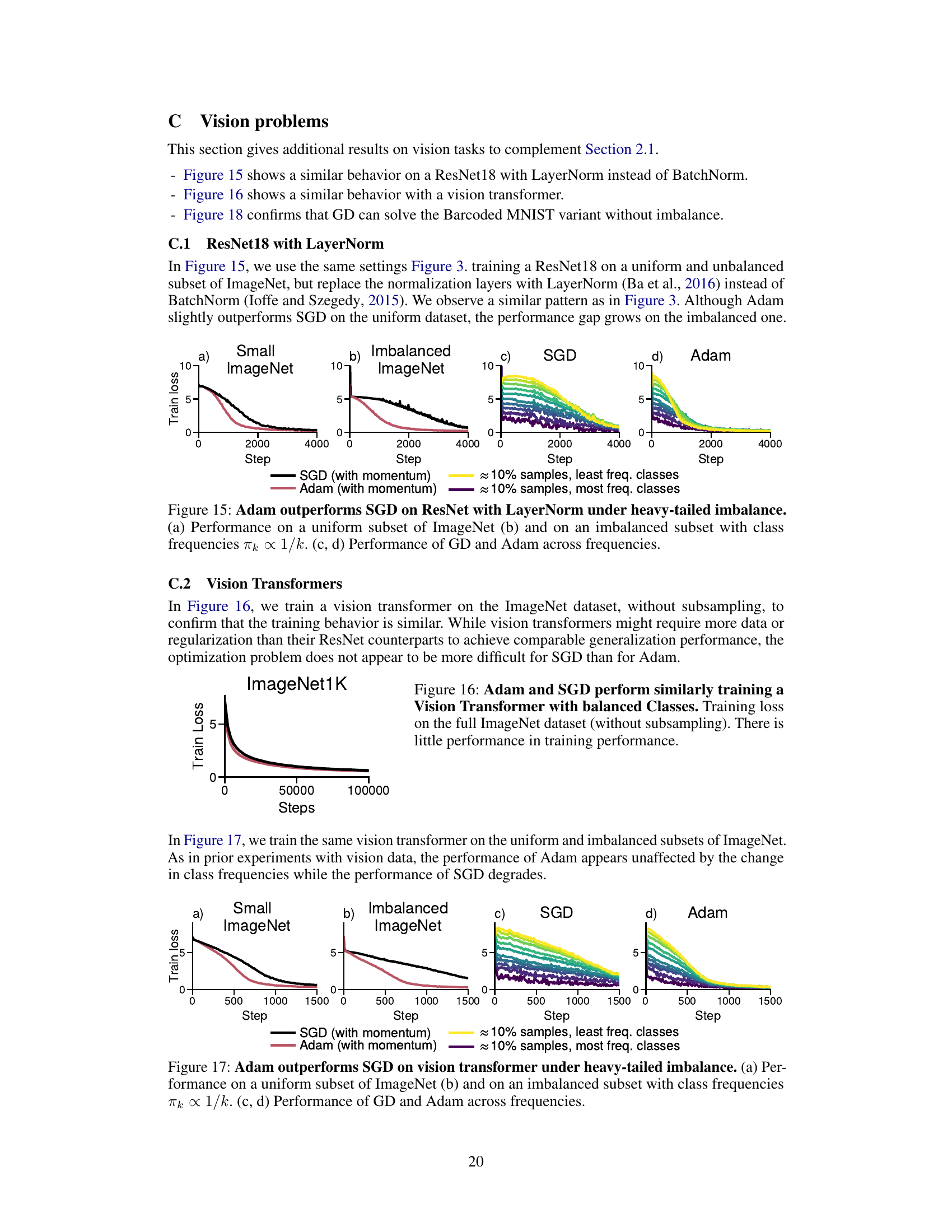

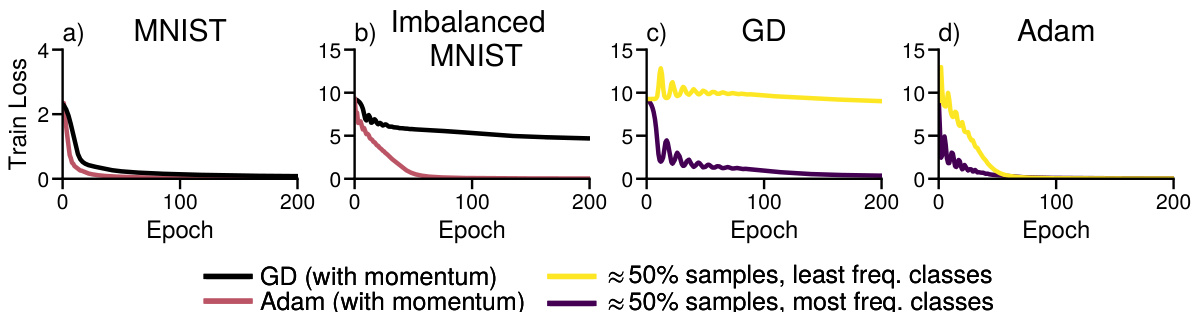

More on figures

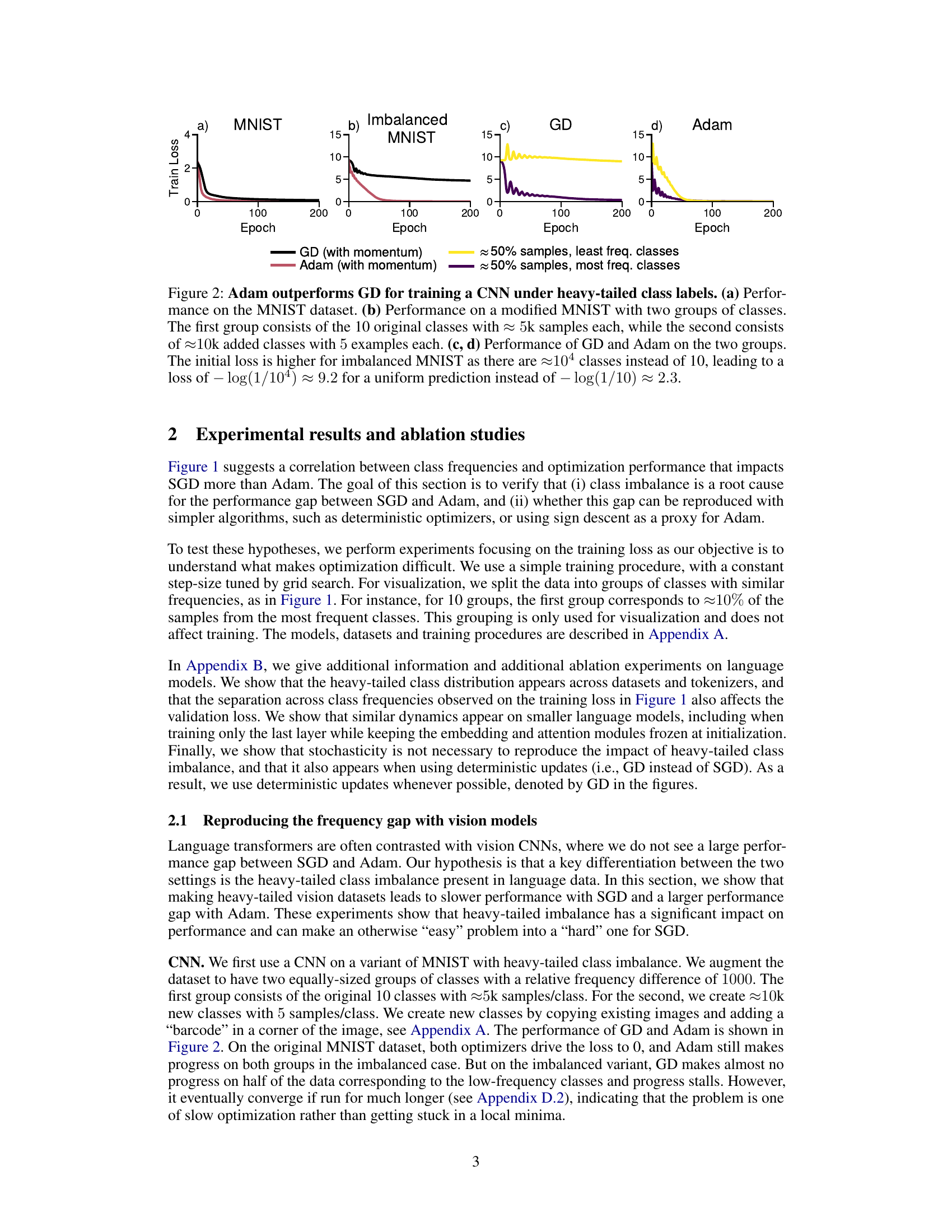

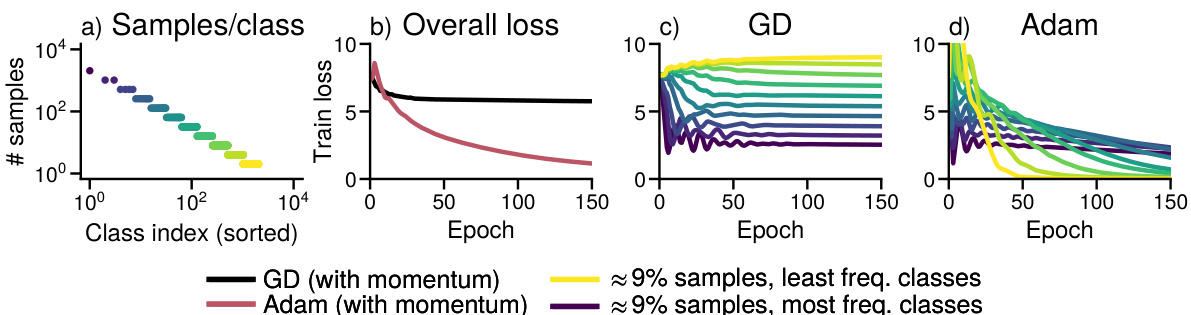

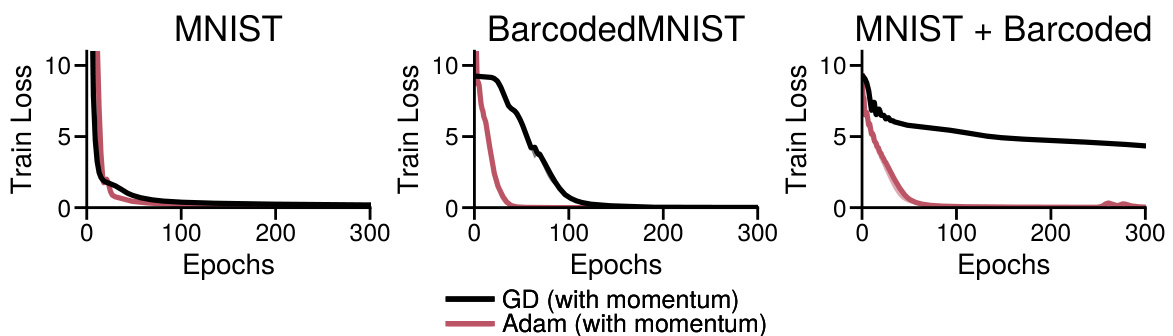

This figure shows the training loss curves for both Adam and Gradient Descent (GD) optimizers when training a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) on two versions of the MNIST dataset. The first version is the standard MNIST dataset, and the second version is a modified MNIST dataset with heavy-tailed class imbalance, where a large number of classes have very few samples. The results show that Adam significantly outperforms GD on the imbalanced dataset but performs similarly to GD on the balanced dataset. This highlights the impact of heavy-tailed class imbalance on the performance of GD compared to Adam.

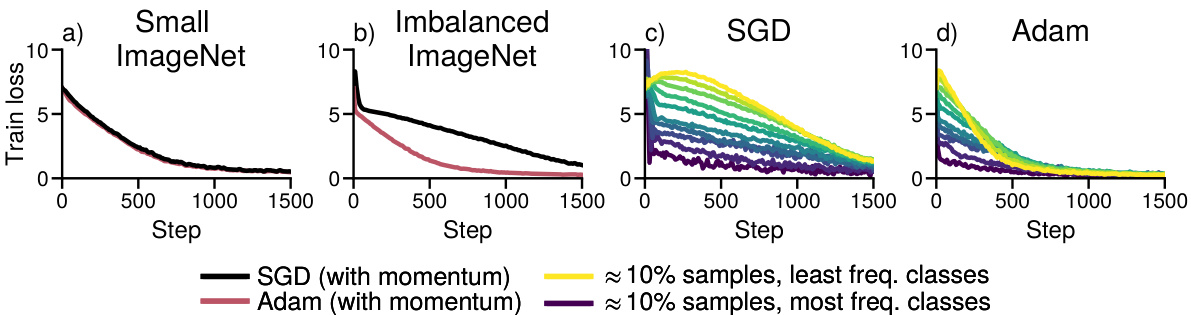

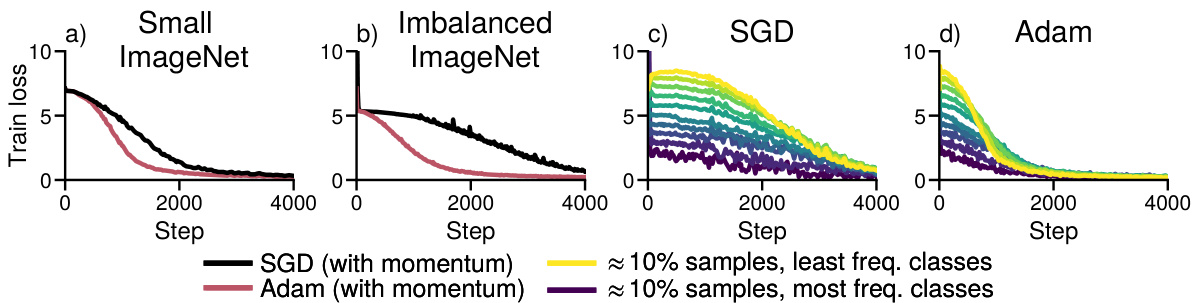

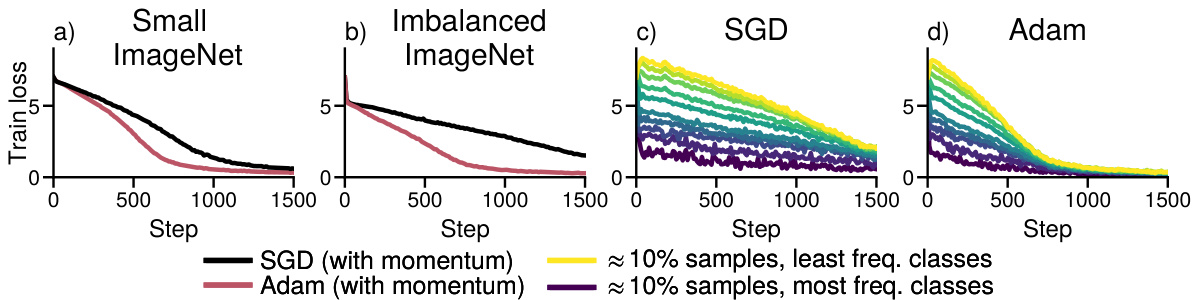

This figure shows the training loss curves for both SGD and Adam on ResNet18 when training on a subset of ImageNet with uniform class distribution (a) and heavy-tailed class distribution (b). Panels (c) and (d) break down the loss for subsets of classes grouped by frequency, showing SGD’s significantly slower progress on low-frequency classes compared to Adam. This illustrates the impact of heavy-tailed class imbalance on SGD’s performance.

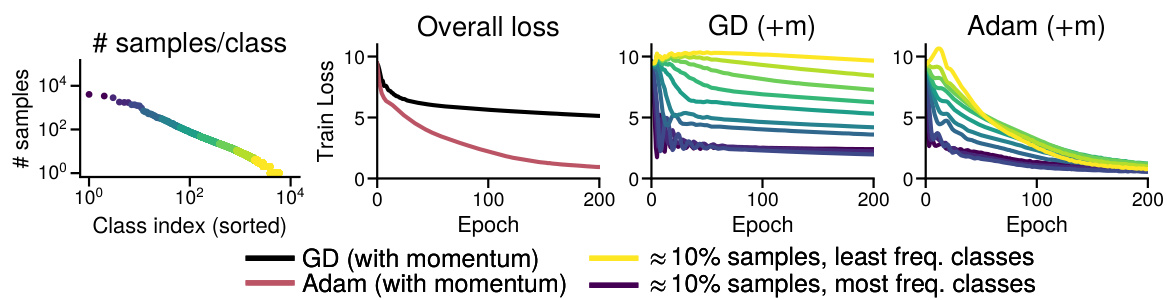

The figure shows the training loss curves for both Adam and SGD optimizers when training a GPT-2 small model on the WikiText-103 dataset. The x-axis represents the training step. The y-axis represents the training loss. The figure is divided into four subplots: (a) shows the distribution of classes by frequency, (b) shows the overall training loss, and (c) and (d) show the training loss for different groups of classes (10% of the data each) for SGD and Adam respectively. The key observation is that SGD struggles to make progress on low-frequency classes while Adam is able to consistently reduce the loss for all classes, showcasing its advantage in handling class imbalance.

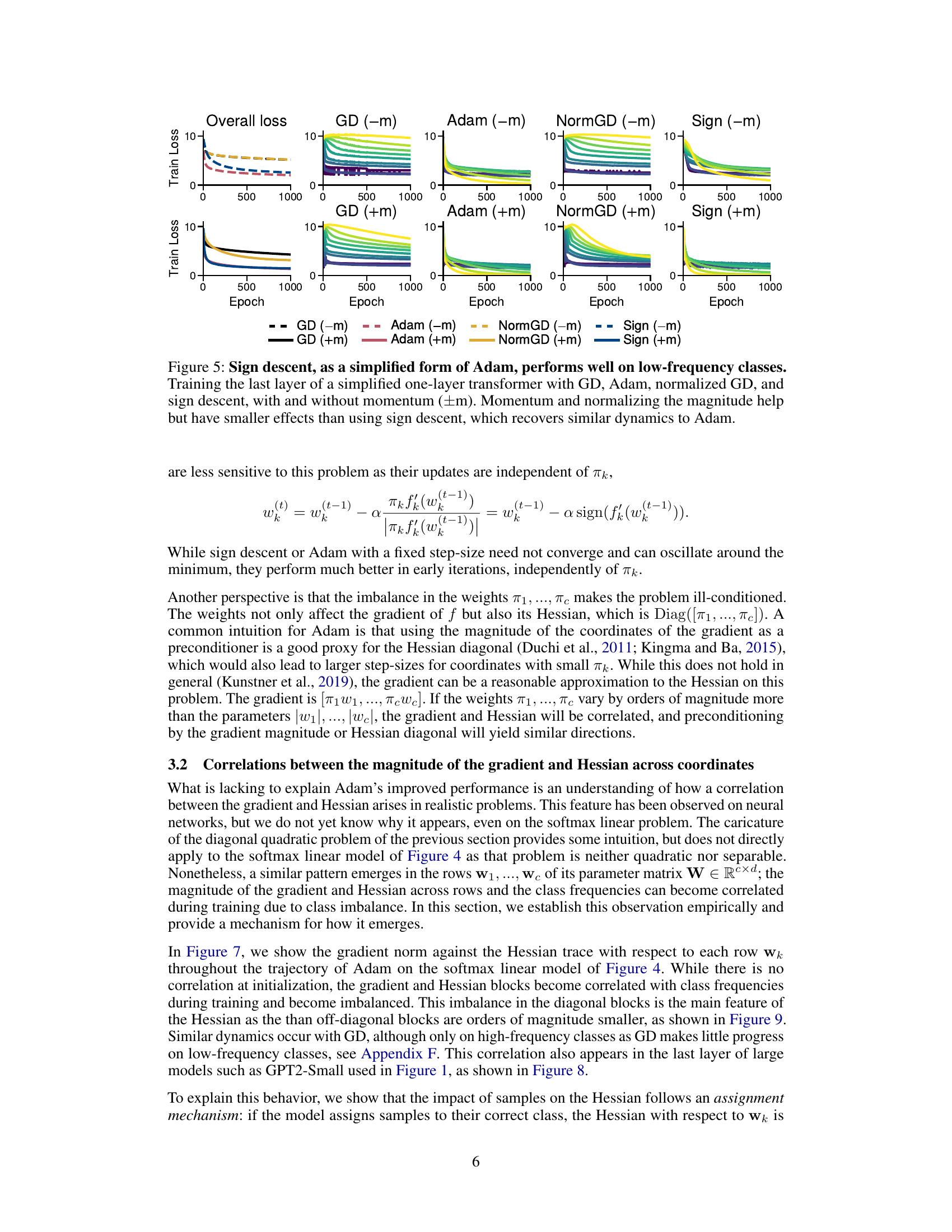

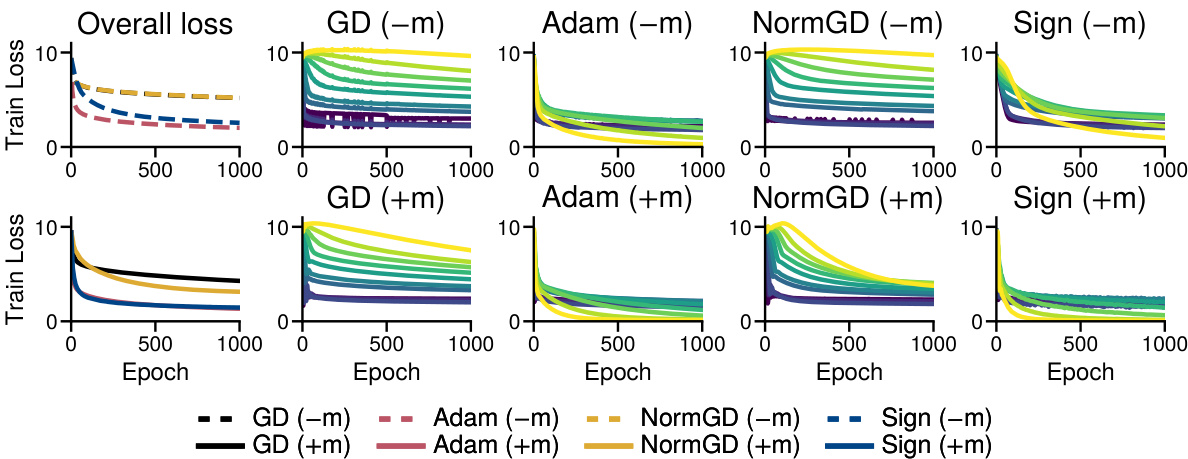

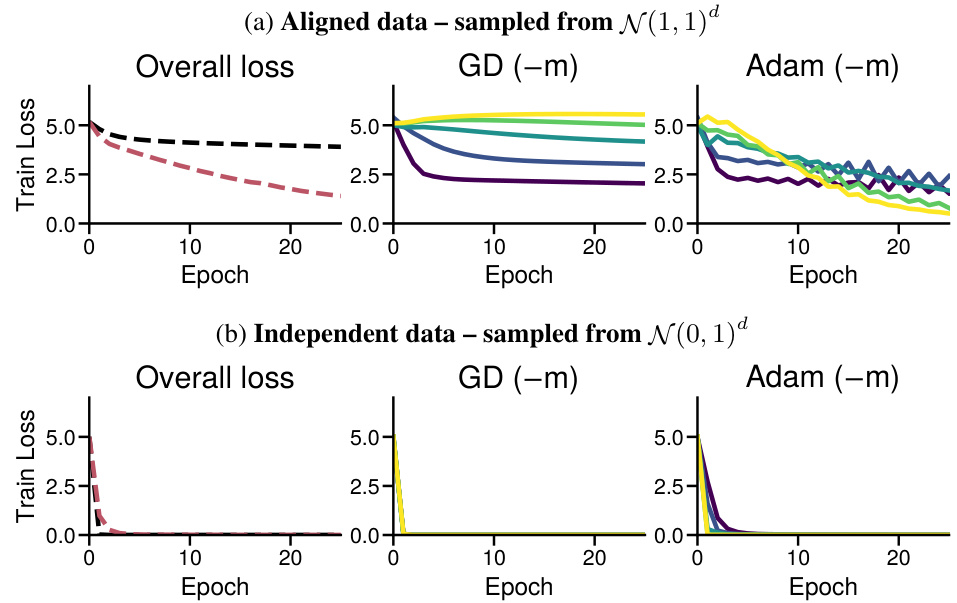

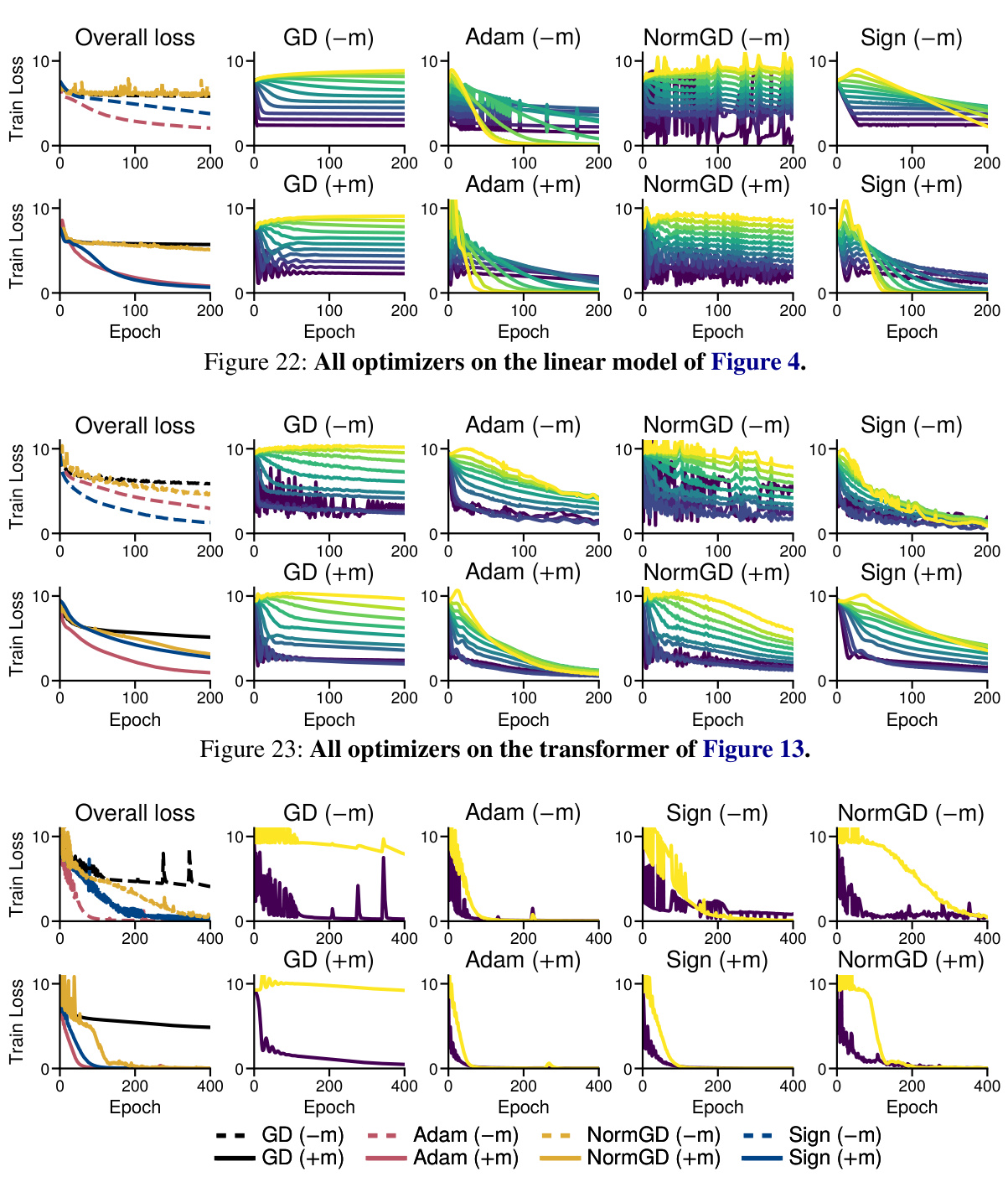

This figure compares the performance of four optimization algorithms (Gradient Descent (GD), Adam, Normalized GD, and Sign Descent) on training the last layer of a simplified transformer model. The experiment is designed to isolate the impact of the optimization algorithm on the ability to train low-frequency classes in a heavy-tailed class imbalance scenario. The results show that sign descent, a simplified version of Adam, shows improved performance on low-frequency classes, which is a characteristic of Adam’s success in large language models. The impact of momentum and normalization of the gradient magnitudes are also evaluated.

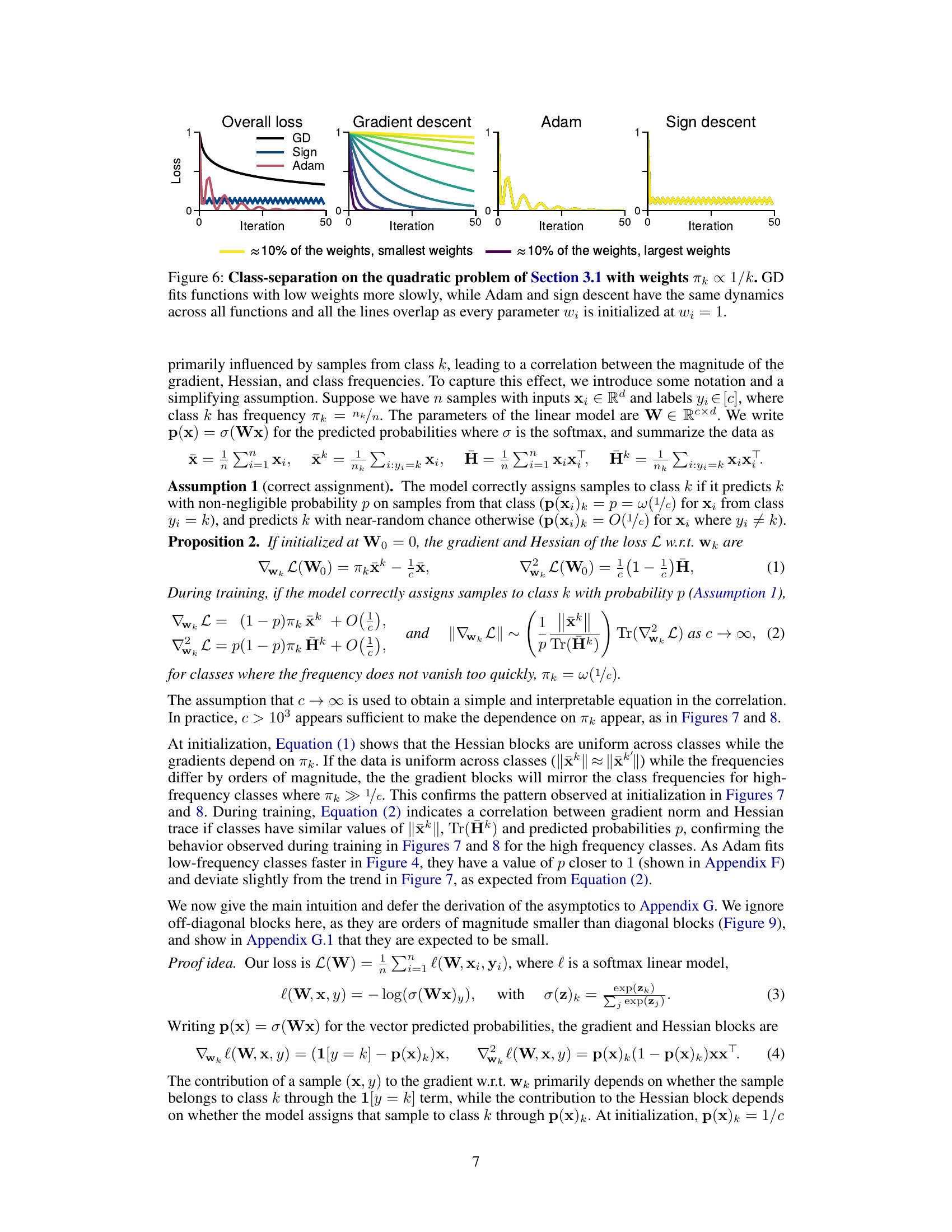

This figure shows the comparison of three optimization algorithms (Gradient Descent, Adam, and Sign Descent) on a weighted quadratic problem. The weights of the functions are inversely proportional to their index (πk = 1/k), simulating heavy-tailed class imbalance. Gradient Descent shows slow convergence on low-weighted functions, whereas Adam and Sign Descent exhibit similar and faster convergence across all functions. This illustrates that Adam and Sign descent are less sensitive to the scale differences caused by imbalanced weights compared to gradient descent.

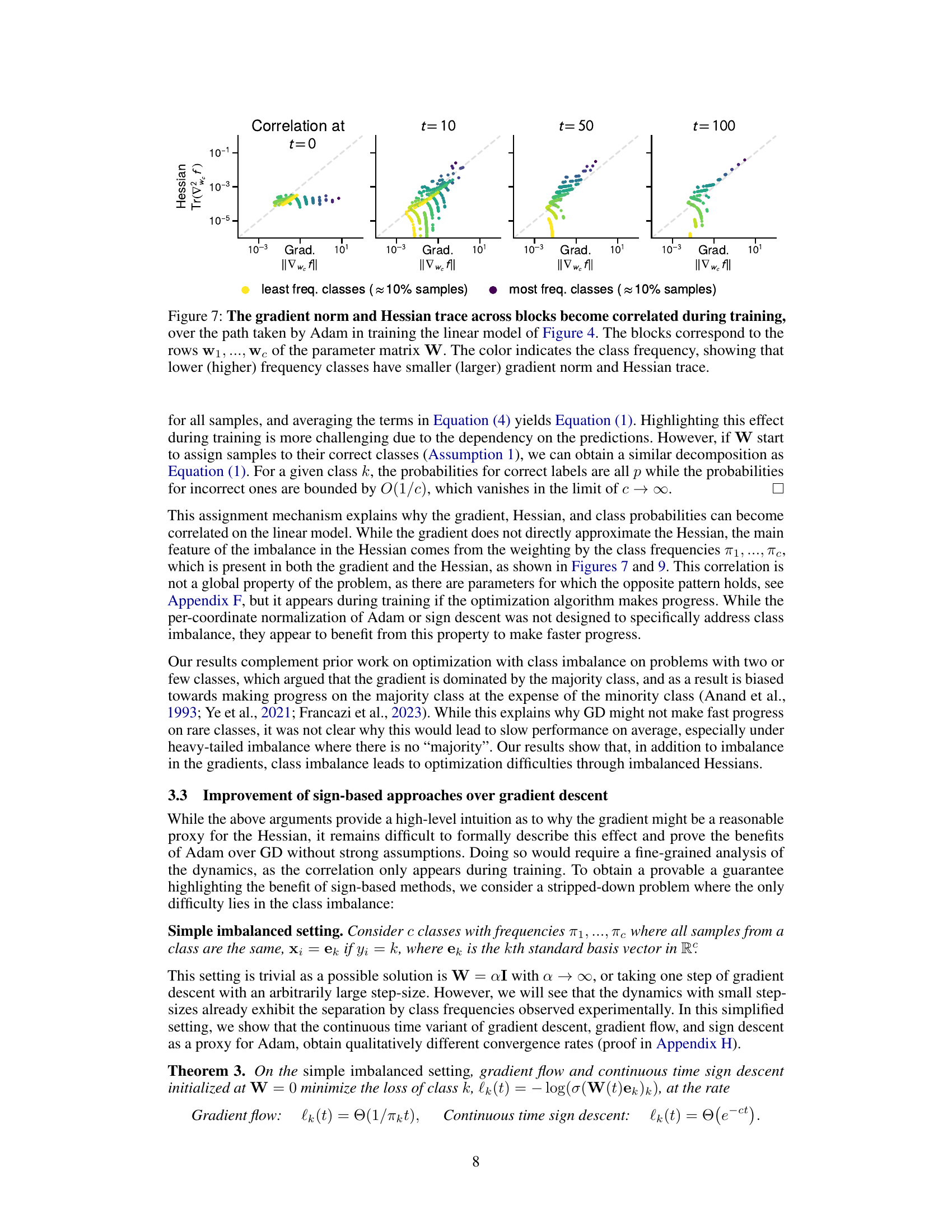

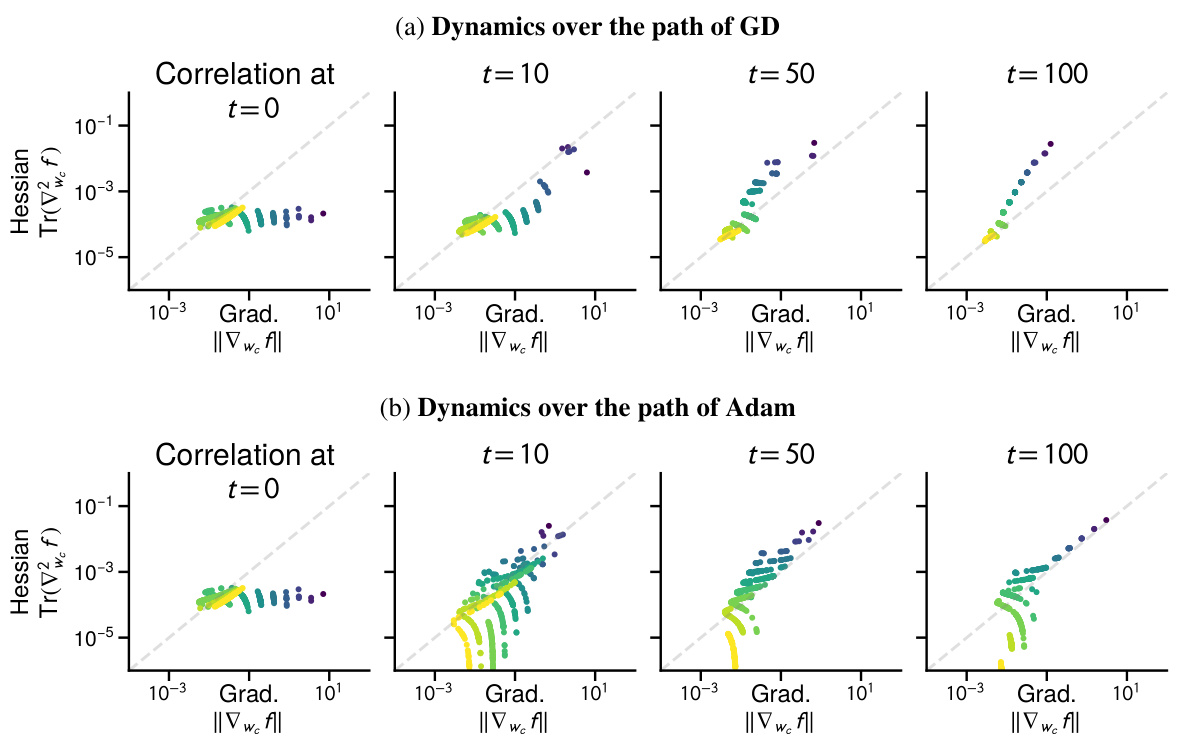

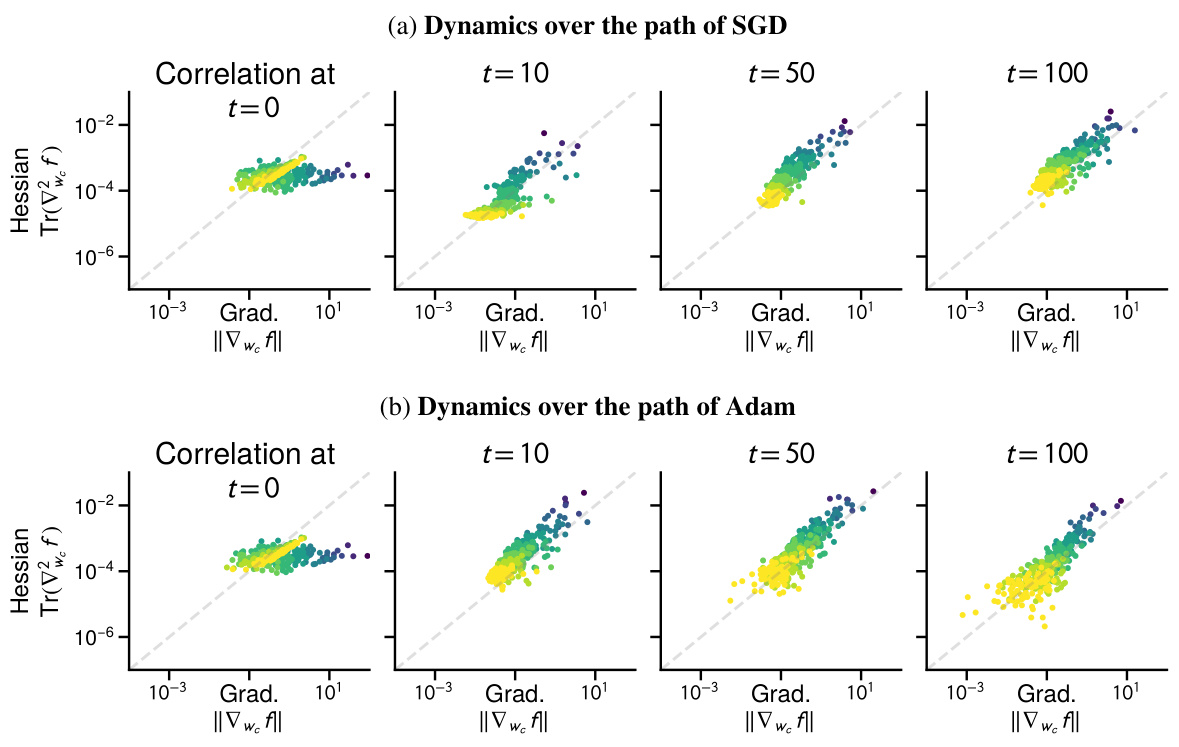

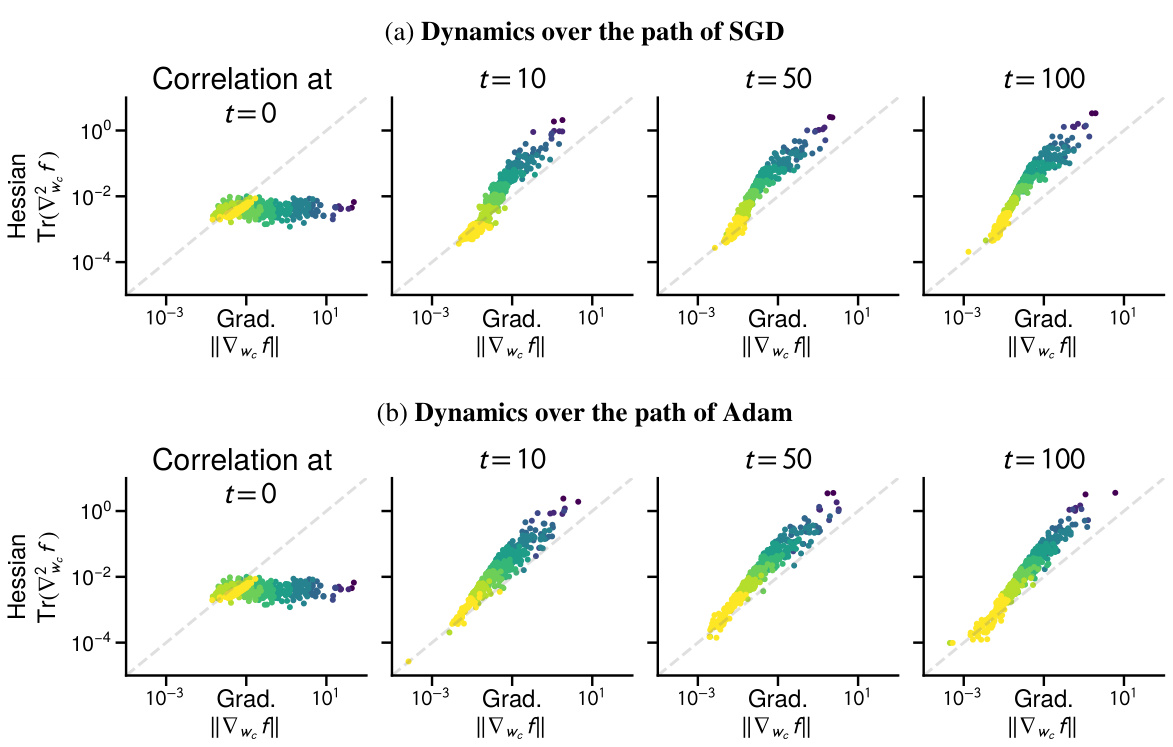

This figure visualizes the correlation between the magnitude of the gradient and the trace of the Hessian (a measure of curvature) across different parameter blocks (rows of the weight matrix W) during the training process of a linear model. The color-coding represents class frequencies, revealing a growing correlation between the magnitude of the gradient/Hessian and class frequency. This correlation is weak initially but strengthens during training, suggesting that Adam’s optimization path implicitly handles heavy-tailed class imbalance, as seen in low-frequency classes.

This figure shows how the correlation between gradient norm and Hessian trace changes during the training process for a linear model with heavy-tailed class imbalance. It visualizes this correlation across different blocks of the parameter matrix (rows W1,…,Wc), color-coded by class frequency. The key observation is that as training progresses using the Adam optimizer, a strong correlation emerges between the magnitude of the gradient/Hessian and class frequency: low-frequency classes tend to have smaller gradients and Hessian traces, while high-frequency classes have larger ones. This correlation is not present at the beginning of training (t=0).

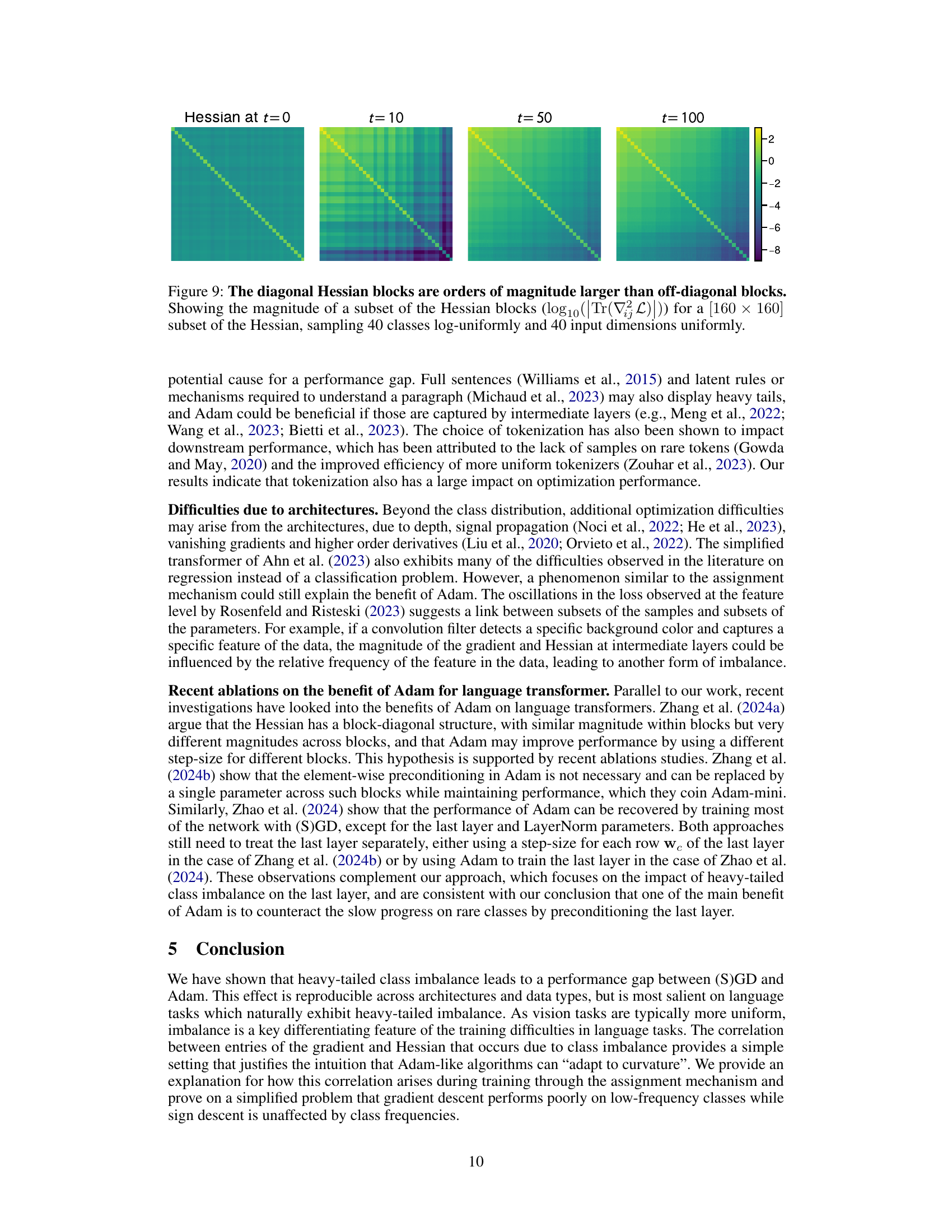

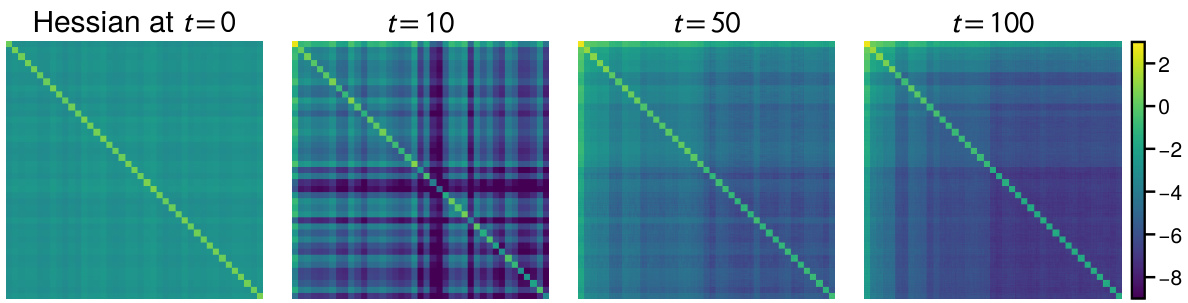

This figure shows the magnitude of the Hessian’s diagonal and off-diagonal blocks at different training times. The diagonal blocks, representing the self-interaction of parameters within the same class, are significantly larger than the off-diagonal blocks (representing interaction between parameters from different classes). This difference highlights the class imbalance’s impact on the Hessian structure, a key aspect of the paper’s argument regarding Adam’s superior performance.

This figure shows the training loss curves for both Adam and SGD optimizers when training a GPT2-Small model on the WikiText-103 dataset. The dataset’s classes (words) have a heavily skewed distribution, with some words appearing much more frequently than others. The figure demonstrates that while Adam successfully reduces the training loss for both frequent and infrequent words, SGD struggles to make progress on the infrequent ones, leading to a much slower overall decrease in loss. This highlights a key difference between the two optimizers’ performance on language modeling tasks.

This figure shows the training loss curves for both Adam and SGD optimizers when training a GPT2-Small model on the WikiText-103 dataset. The dataset’s words are grouped by frequency (10% of data at each frequency level). The plots demonstrate that while Adam reduces training loss effectively for both low-frequency and high-frequency words, SGD struggles to improve low-frequency words, highlighting Adam’s superior performance on heavy-tailed class imbalance common in language tasks.

This figure shows the training loss curves for both Adam and SGD optimizers on the WikiText-103 dataset using the GPT2-Small model. The x-axis represents the training step, and the y-axis represents the training loss. Panel (a) shows the distribution of the number of samples per class (i.e., class imbalance). Panels (c) and (d) display the loss curves broken down by class frequency groups (approximately 10% of the data each) for SGD and Adam respectively. Panel (b) shows the overall training loss, which is an average of (c) and (d). The key takeaway is that Adam continues to make progress on low-frequency classes, whereas SGD does not.

This figure shows the training loss curves for both Adam and SGD optimizers while training a GPT2-Small model on the WikiText-103 dataset. The dataset is heavily imbalanced, with some classes having many more samples than others. The figure demonstrates that SGD struggles to reduce the loss for infrequent classes, while Adam successfully optimizes across all classes, demonstrating a key difference in performance between Adam and SGD on imbalanced datasets.

This figure shows that Adam optimizer is able to make progress on low-frequency classes during training of GPT-2 small model on WikiText-103 dataset, while the SGD optimizer is unable to make progress on those classes. The figure consists of four subplots: (a) shows the distribution of classes sorted by their frequency, (b) shows the overall training loss, (c) shows the training loss for each group of classes using SGD optimizer, and (d) shows the training loss for each group of classes using Adam optimizer. The results indicate that Adam is less sensitive to the heavy-tailed class imbalance in language tasks.

This figure demonstrates that Adam outperforms SGD in training a ResNet18 model on both a standard subset of ImageNet and a modified subset with heavy-tailed class imbalance. The imbalanced subset simulates real-world scenarios where class frequencies follow a power law (πk α 1/k). The plots show that SGD struggles to make progress on low-frequency classes, while Adam shows more consistent improvement across all classes. This highlights Adam’s resilience to the challenges posed by heavy-tailed class imbalance.

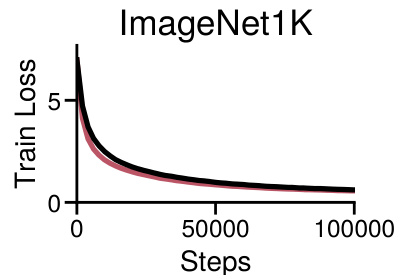

This figure shows the training loss curves for Adam and SGD optimizers while training a Vision Transformer model on the full ImageNet dataset. The key takeaway is that both optimizers show similar performance, indicating no significant performance gap between Adam and SGD in this specific scenario with a balanced dataset. This contrasts with the findings in other parts of the paper which highlight a performance gap when dealing with datasets exhibiting heavy-tailed class imbalance.

This figure demonstrates the performance difference between Adam and SGD optimizers when training a ResNet18 model on ImageNet datasets with varying class distributions. The left two subplots (a and b) show the overall training loss for both optimizers on a balanced subset of ImageNet (a) and on an imbalanced subset (b) where the frequency of classes follows a power law (πk α 1/k). The right two subplots (c and d) break down the loss per group of classes (roughly 10% of samples each). This detailed view clearly shows how SGD struggles to optimize for low-frequency classes while Adam continues to make progress across all classes, showcasing the impact of heavy-tailed class imbalance on SGD’s performance.

This figure shows the training loss curves for both Adam and GD optimizers on three different MNIST datasets: the original MNIST, a dataset with only the barcoded images (balanced classes), and a dataset with both the original and barcoded images (imbalanced classes). The results demonstrate that GD performs similarly to Adam on balanced data, but significantly worse on imbalanced data, especially when focusing on low-frequency classes. This confirms that heavy-tailed class imbalance is a key factor in Adam’s superior performance over GD, not simply an issue of dataset difficulty.

This figure shows the training loss curves for both Adam and SGD optimizers while training a GPT2-Small language model on the WikiText-103 dataset. The x-axis represents training steps. The y-axis represents the training loss. The classes are grouped by frequency (10% of data per group), and the curves are shown for each group separately and as an average. The figure demonstrates Adam’s superior performance, particularly for low-frequency classes where SGD shows minimal progress.

This figure demonstrates the key finding of the paper: Adam’s superiority over gradient descent in training large language models stems from its ability to handle heavy-tailed class imbalance. The plot shows the training loss for GPT2-Small on WikiText-103. Panel (a) displays the class distribution, sorted by frequency, divided into deciles. Panel (b) shows the overall training loss for both Adam and SGD. Panels (c) and (d) break down the training loss for each decile, revealing that SGD struggles to reduce the loss for low-frequency classes, while Adam makes consistent progress across all classes.

This figure shows the impact of L2 regularization on the performance gap between GD and Adam on the linear model experiment. Despite using L2 regularization to limit the magnitude of weights, the performance gap remains visible, particularly at lower regularization strengths. However, as regularization increases, fitting low-frequency classes becomes harder, and the performance difference diminishes.

This figure shows the training loss curves for both Adam and SGD optimizers when training a GPT-2 small language model on the WikiText-103 dataset. It highlights the impact of heavy-tailed class imbalance, where infrequent words (classes) have significantly slower loss reduction with SGD than frequent words. In contrast, Adam demonstrates consistent progress across all word frequency groups. The figure is divided into four subplots: (a) Displays the distribution of classes based on their frequency. Classes are grouped into deciles for easier visualization. (b) Presents the overall training loss for both optimizers across training steps. (c,d) Shows the training loss for each decile (group of classes) separately, further emphasizing Adam’s superior performance on infrequent word classes.

This figure shows the impact of reweighting the loss function to address class imbalance on four different machine learning problems: PTB, Linear, HT MNIST, and HT ImageNet. It compares the performance of standard SGD and Adam optimizers with two variations of SGD that use reweighted loss functions. The reweighted loss functions are designed to give more weight to low-frequency classes, aiming to mitigate the slow convergence of SGD on these classes. The results indicate that reweighting can improve SGD’s performance, sometimes outperforming standard SGD, especially when using the 1/√πk weighting scheme. However, reweighting with 1/πk showed mixed results, sometimes outperforming and sometimes underperforming standard SGD, highlighting the complexity of this approach. The type of updates (stochastic or deterministic) also vary across problems.

This figure shows the correlation between the gradient norm and the Hessian trace across blocks throughout the training process, specifically focusing on the path taken by the Adam optimizer in the linear model presented earlier in Figure 4. The plot displays the gradient norm and the Hessian trace for each row of the parameter matrix. The color-coding of the points reflects the frequency of the classes, illustrating a correlation between the magnitude of these values and the frequency of classes. Specifically, the figure highlights that lower-frequency classes tend to exhibit smaller gradient norms and Hessian traces compared to higher-frequency classes.

This figure shows a comparison of the training performance of Adam and SGD optimizers on the GPT2-Small language model trained on the WikiText-103 dataset. The x-axis represents the training steps, and the y-axis represents the training loss. The figure demonstrates that SGD struggles to make progress on low-frequency classes (words that appear less often in the dataset), while Adam consistently improves across all classes, regardless of frequency. The different panels show the overall loss and the loss for different groups of classes, divided by frequency.

This figure shows the correlation between gradient and Hessian throughout the Adam optimization process on a linear model with heavy-tailed class imbalance. The x-axis represents the gradient norm, and the y-axis represents the trace of the Hessian, both calculated for each row of the weight matrix. Each point represents a block of the Hessian corresponding to a particular class. The color of the point indicates the class frequency. The figure demonstrates that as the training progresses, a correlation develops between the magnitude of the gradient and Hessian and the class frequency. Specifically, lower frequency classes show a smaller gradient norm and Hessian trace, while higher frequency classes show larger values.

This figure shows the correlation between the magnitude of the gradient and the trace of the Hessian across coordinates during the training process using the Adam optimizer. The x-axis represents the gradient norm, and the y-axis represents the trace of the Hessian. Each point represents a coordinate (row of the parameter matrix), and the color indicates the frequency of the corresponding class. The results demonstrate that as training progresses (from t=0 to t=100), a correlation emerges between the magnitude of the gradient/Hessian and class frequency, particularly highlighting how Adam’s optimization dynamics lead to a stronger correlation between these factors compared to the initial state.

This figure shows the correlation between the gradient norm and Hessian trace across blocks during the training process using Adam optimizer on a linear model. It demonstrates that this correlation emerges over time and is related to the class frequency. Specifically, lower frequency classes exhibit smaller gradient norms and Hessian traces, while higher frequency classes show larger values. This correlation, not present at initialization, is considered relevant to the superior performance of Adam in heavy-tailed class imbalance scenarios.

This figure shows the correlation between the magnitude of the gradient and Hessian trace with respect to each row of the parameter matrix W throughout the training process using Adam optimizer. The training is done on the linear model with heavy-tailed class imbalance. The color-coding of data points represents class frequencies, illustrating that lower frequency classes exhibit smaller gradient norm and Hessian trace compared to high-frequency classes. This correlation emerges during training, demonstrating that Adam’s performance benefit may be linked to how it handles this correlation and the imbalance between different class frequencies.

This figure shows that the correlation between the gradient and Hessian blocks observed during the training process of Adam on the linear model (Figure 4) does not hold globally, and is dependent on the optimization path. It illustrates that the positive correlation appears throughout training and is not present at initialization (t=0). If we consider the opposite path of Adam’s iterates (-Wt), we find a negative correlation.

This figure visually demonstrates the magnitude difference between the diagonal and off-diagonal blocks of the Hessian matrix. The Hessian matrix, which represents the second derivative of the loss function with respect to the model’s parameters, is crucial in understanding optimization dynamics. The diagonal elements are significantly larger than off-diagonal elements. This is shown by plotting the log of the trace of the absolute value of each block (a 40x40 subset sampled from a larger Hessian). The color intensity represents the magnitude. The figure illustrates the result across different optimization steps (t=0, 10, 50, 100), highlighting how this pattern emerges and persists over time.

Full paper#