↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) heavily rely on the Transformer architecture, with the attention mechanism being a significant computational bottleneck. Existing methods like FlashAttention have shown some promise in speeding up attention, but limitations persist, such as suboptimal GPU utilization. This research aims to address these limitations and improve attention computation efficiency.

FlashAttention-3, the focus of this research, introduces three key techniques: producer-consumer asynchrony to overlap computation and data movement; overlapping softmax operations with matrix multiplication; and hardware-accelerated low-precision computation using FP8. This approach achieves a significant speedup on H100 GPUs (1.5-2x with BF16, reaching up to 840 TFLOPs/s; 1.3 PFLOPs/s with FP8), while simultaneously demonstrating improved numerical accuracy compared to previous methods. The code is also open-sourced for community use.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large language models (LLMs) and Transformers. It presents FlashAttention-3, a significantly faster and more accurate attention mechanism, addressing a major bottleneck in LLM development. This advancement has the potential to unlock new applications in long-context tasks and accelerate progress in the field. The open-source nature of the code ensures widespread adoption and collaboration.

Visual Insights#

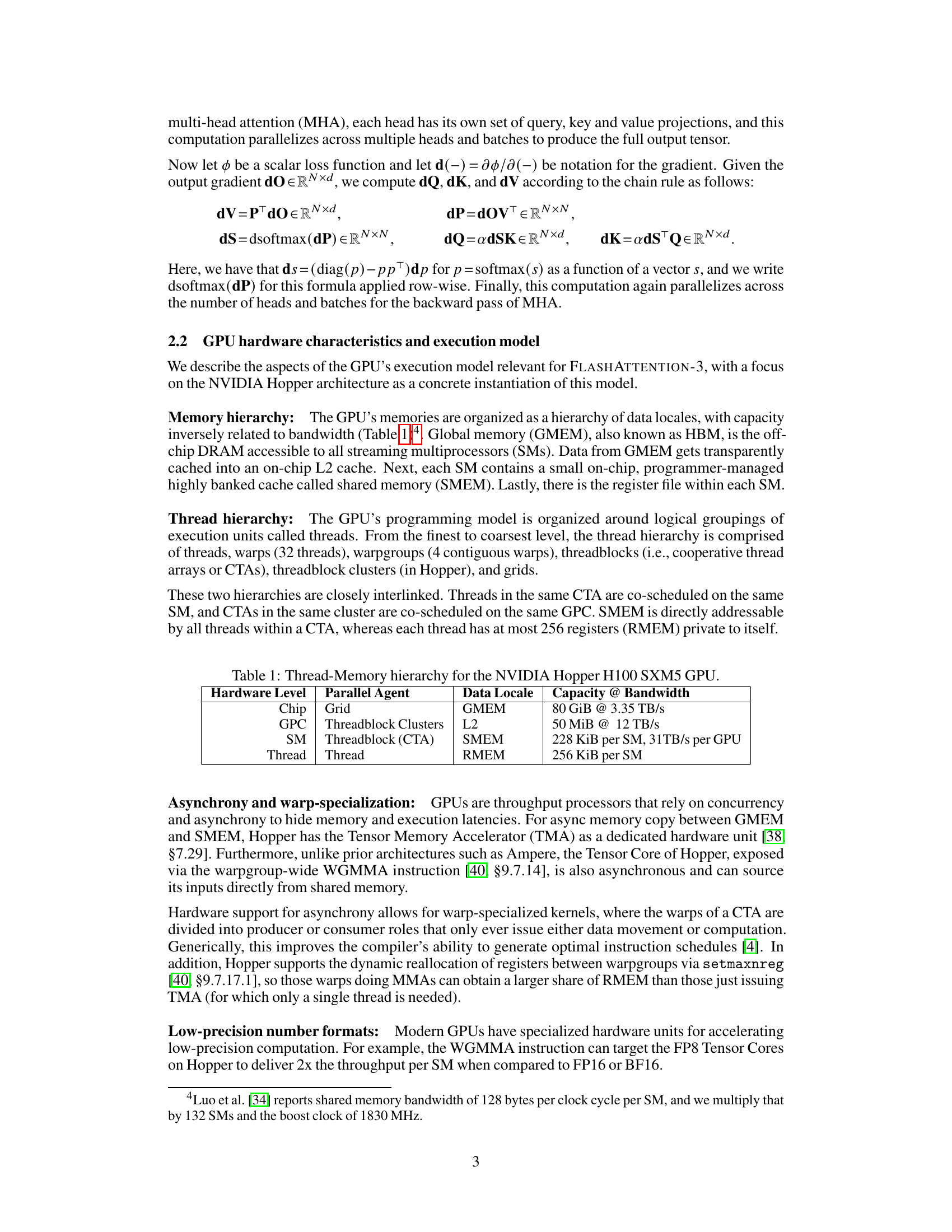

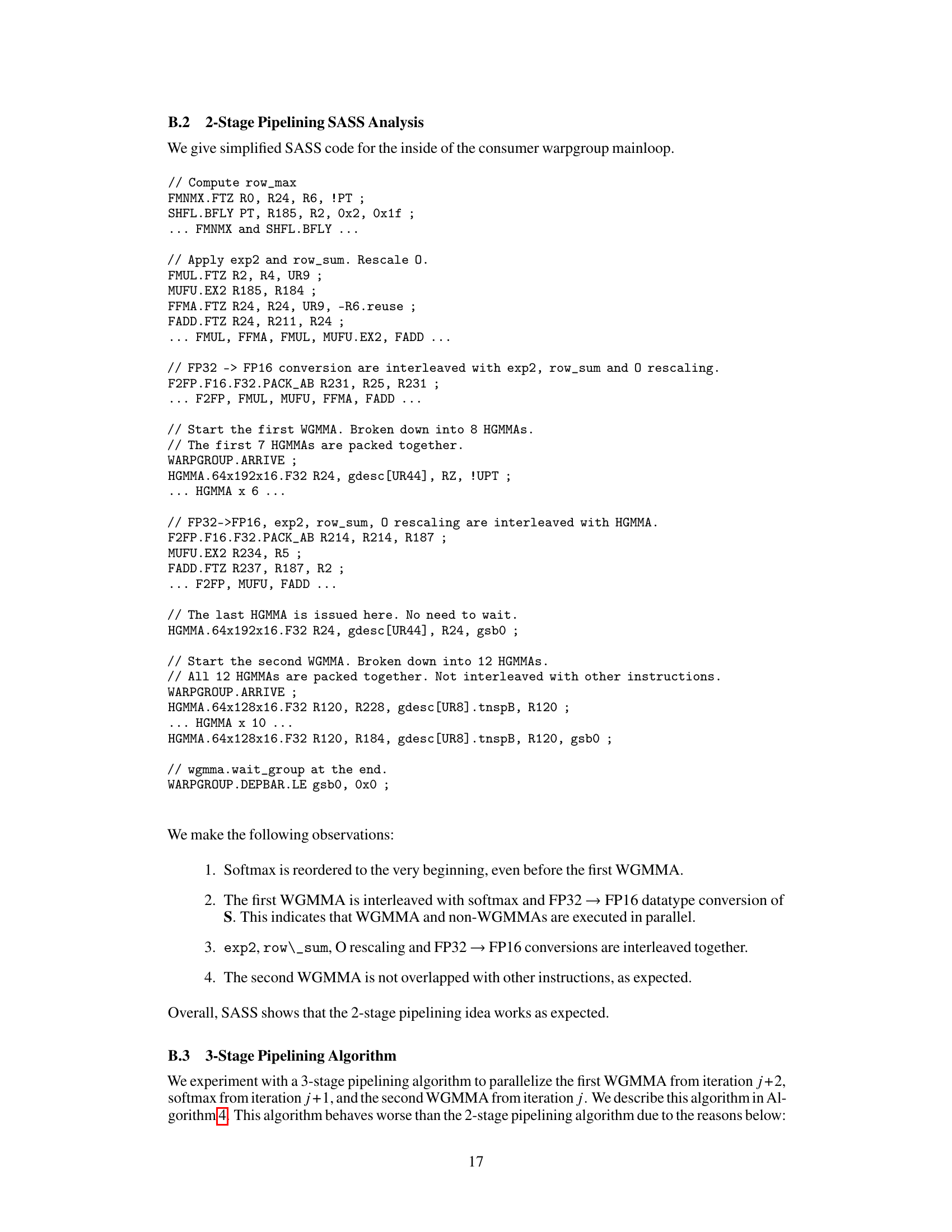

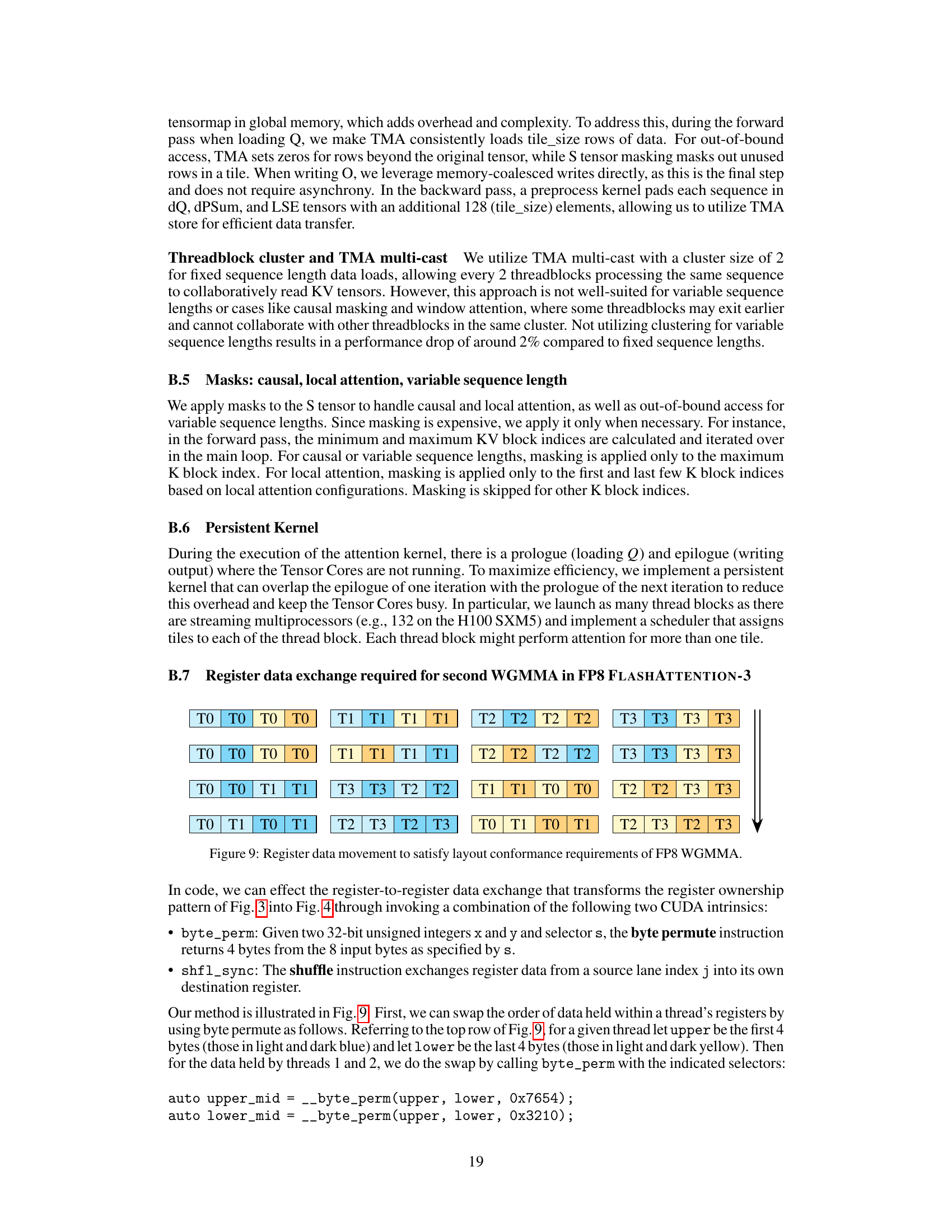

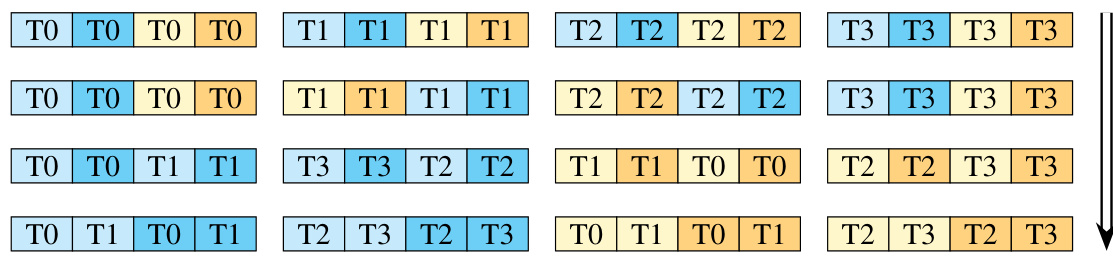

This figure illustrates the ping-pong scheduling strategy used in FlashAttention-3 to overlap computation. Two warpgroups (sets of threads) work in parallel. While one warpgroup performs GEMM operations (matrix multiplication), the other performs softmax calculations. Then, the roles switch, creating an overlap and hiding latency.

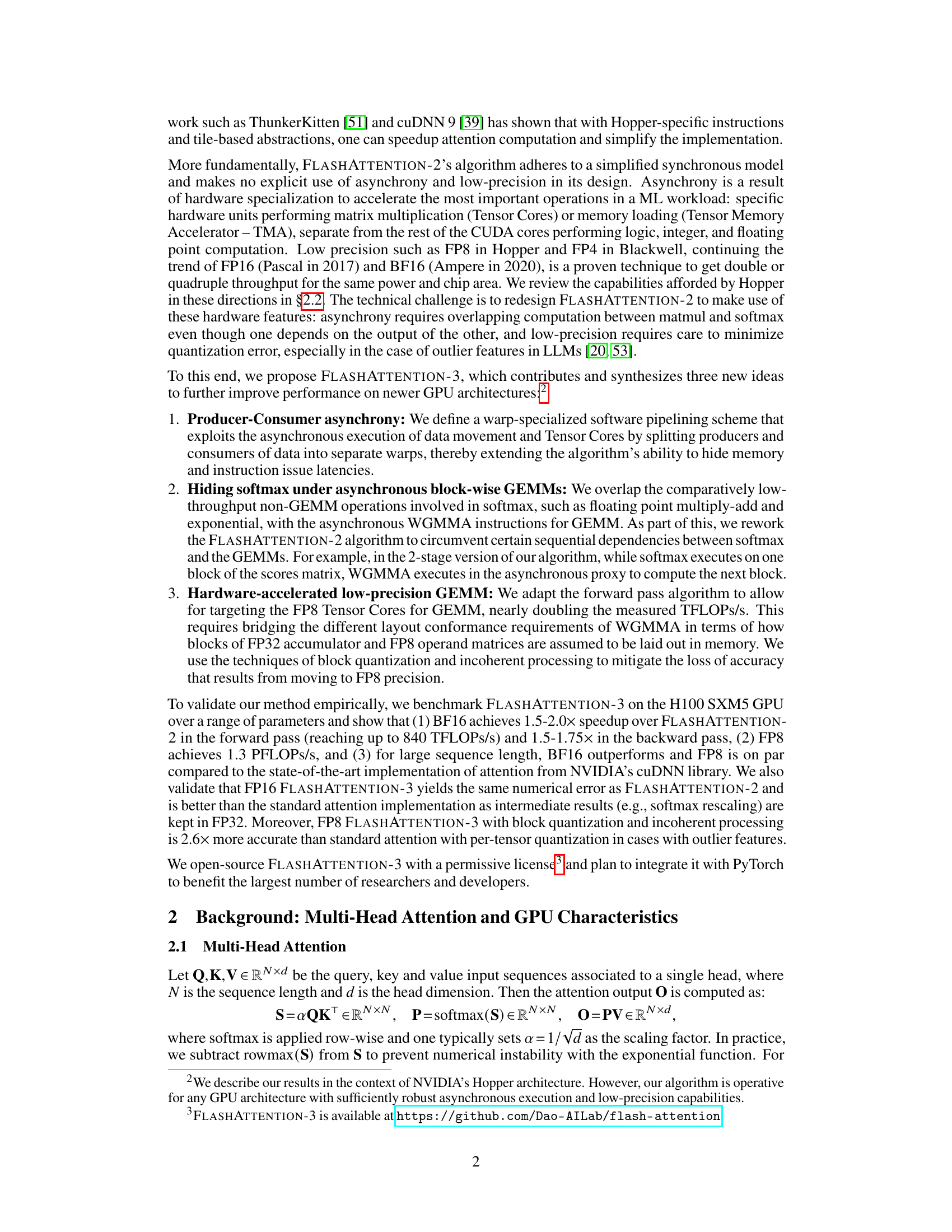

This table shows the memory hierarchy of the NVIDIA Hopper H100 SXM5 GPU, including the capacity and bandwidth of each level: Global Memory (GMEM), L2 Cache, Shared Memory (SMEM), and Registers (RMEM). It also specifies the parallel agent associated with each memory level, showing the relationship between the hardware architecture and the parallel programming model.

In-depth insights#

Async. Attention#

Asynchronous attention mechanisms represent a significant advancement in accelerating attention computations, a critical bottleneck in Transformer models. The core idea is to overlap computationally expensive operations like matrix multiplication and softmax, traditionally performed sequentially, by leveraging the inherent asynchronicity of modern GPU architectures. This allows the GPU to perform data movement (memory accesses) concurrently with core computations, thereby significantly reducing latency. Warp specialization plays a crucial role, dividing warps within a thread block into producers and consumers of data. This carefully orchestrated dataflow enhances efficiency by hiding memory access latencies and maximizing hardware utilization. Low-precision arithmetic further boosts performance by reducing memory footprint and accelerating computations through specialized hardware units. However, designing efficient asynchronous attention requires careful management of data dependencies and layout constraints to ensure correctness and maximize the benefits of asynchronicity. The complexity is further amplified by the need to handle various precision formats and the intricacies of software pipelining strategies.

Low-precision gains#

Low-precision arithmetic, particularly using FP8, offers significant speedups in deep learning computations by reducing the memory footprint and increasing the throughput of tensor operations. However, the benefits must be carefully weighed against potential accuracy losses. The paper explores strategies like block quantization and incoherent processing to mitigate these accuracy issues. Block quantization reduces error by scaling blocks of data individually, while incoherent processing randomly transforms data before quantization, thereby distributing the impact of precision loss more evenly. These methods demonstrate a trade-off between speed and precision, with the optimal balance dependent on the specific application and tolerance for error. Further research into sophisticated quantization techniques and error correction strategies is crucial to harness the full potential of low-precision computation without compromising accuracy significantly. The success of these techniques highlights the importance of hardware-software co-design in pushing the boundaries of deep learning performance.

H100 GPU Speedup#

The research paper’s findings on H100 GPU speedup are significant. FlashAttention-3 achieves a 1.5-2.0x speedup over its predecessor using BF16, demonstrating substantial performance gains. This improvement is attributed to three key techniques: exploiting asynchrony in Tensor Cores and TMA, overlapping computation and data movement, and leveraging hardware support for FP8 low-precision. The attainment of up to 840 TFLOPs/s with BF16 (85% utilization) and 1.3 PFLOPs/s with FP8 are remarkable achievements. The results suggest that these optimization strategies effectively utilize the H100’s architecture, overcoming previous limitations. Further validation shows FP8 FlashAttention-3 exhibits significantly lower numerical error compared to a baseline FP8 attention. Overall, the paper highlights the potential of these techniques for accelerating large language models and long-context applications. The observed speedups are very promising and indicate the potential of the improved architecture. The work opens doors for improved performance in the future.

Future Directions#

Future research directions stemming from this FlashAttention-3 paper could involve extending its capabilities to handle even longer sequences and larger batch sizes. Optimizations for specific hardware architectures beyond Hopper GPUs are also warranted. Another crucial area would be to thoroughly investigate the impact of low-precision arithmetic on the accuracy of downstream tasks, especially in large language models. Further exploration into the interplay between asynchrony, low-precision, and algorithm design is needed to fully exploit the potential of modern hardware. A detailed comparative analysis against other state-of-the-art attention mechanisms, including those utilizing approximation techniques, would strengthen the claims of superiority. Finally, exploring the integration of FlashAttention-3 into existing deep learning frameworks such as PyTorch will significantly broaden its adoption and utility within the research community.

Error Analysis#

A dedicated ‘Error Analysis’ section in a research paper would be crucial for evaluating the accuracy and reliability of a proposed method, especially when dealing with approximations or low-precision computations. It should begin by clearly defining the type of errors being measured (e.g., numerical error, approximation error, generalization error). A quantitative analysis, using metrics like RMSE, MAE, or relative error, should be presented, comparing the proposed method’s performance to baselines. This would involve a rigorous evaluation across different datasets and parameter settings, demonstrating error trends as these factors change. Crucially, the error analysis should explore potential sources of errors, identifying the limitations of the approach and suggesting areas for future improvement. A discussion of the trade-offs between accuracy and efficiency, particularly in contexts of limited computational resources, would also strengthen this section. Visualizations, such as error bars or plots demonstrating error distributions, can greatly enhance the understanding and clarity of the analysis. Finally, an explanation of how the error rates affect downstream applications or impact the overall outcome of the system would provide valuable context, solidifying the significance of the error analysis findings.

More visual insights#

More on figures

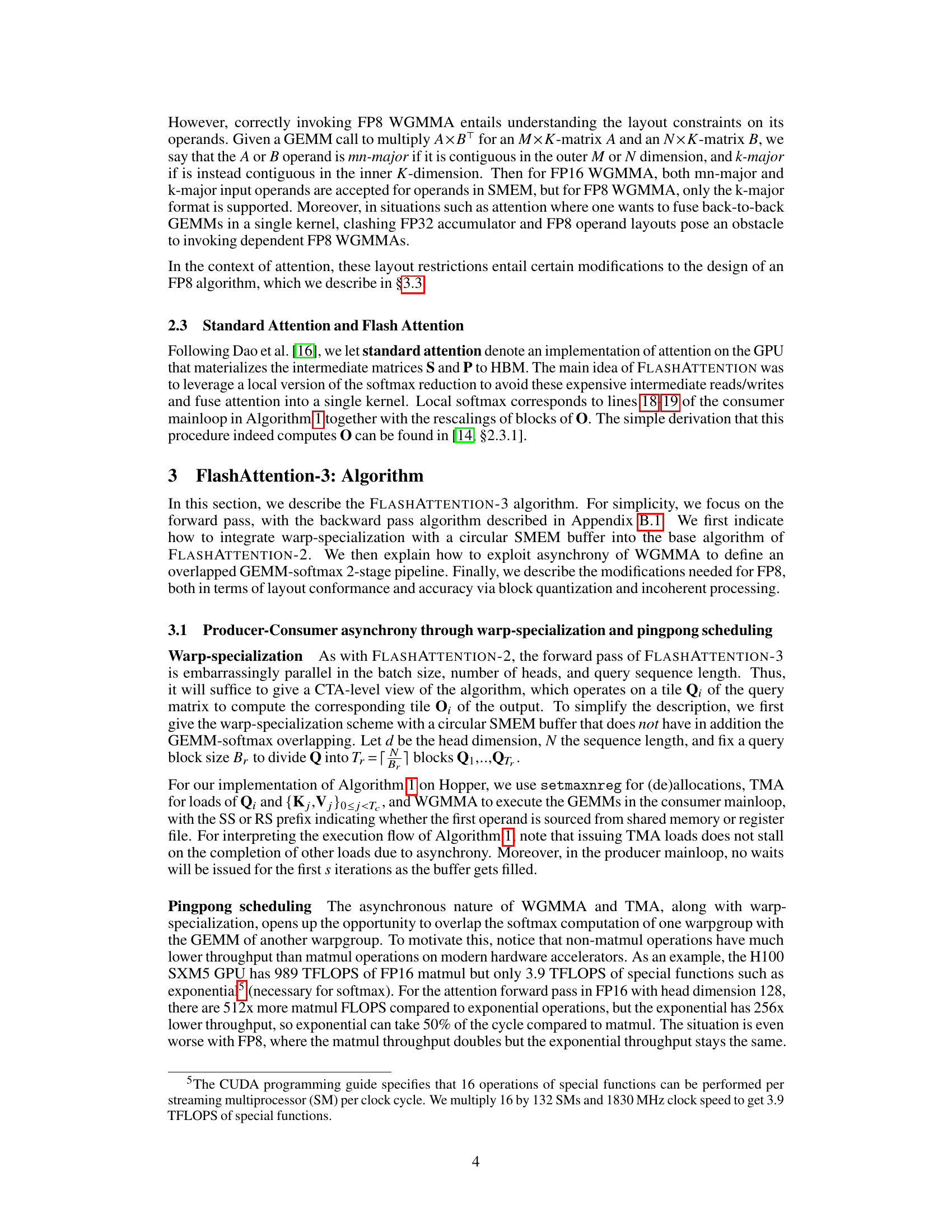

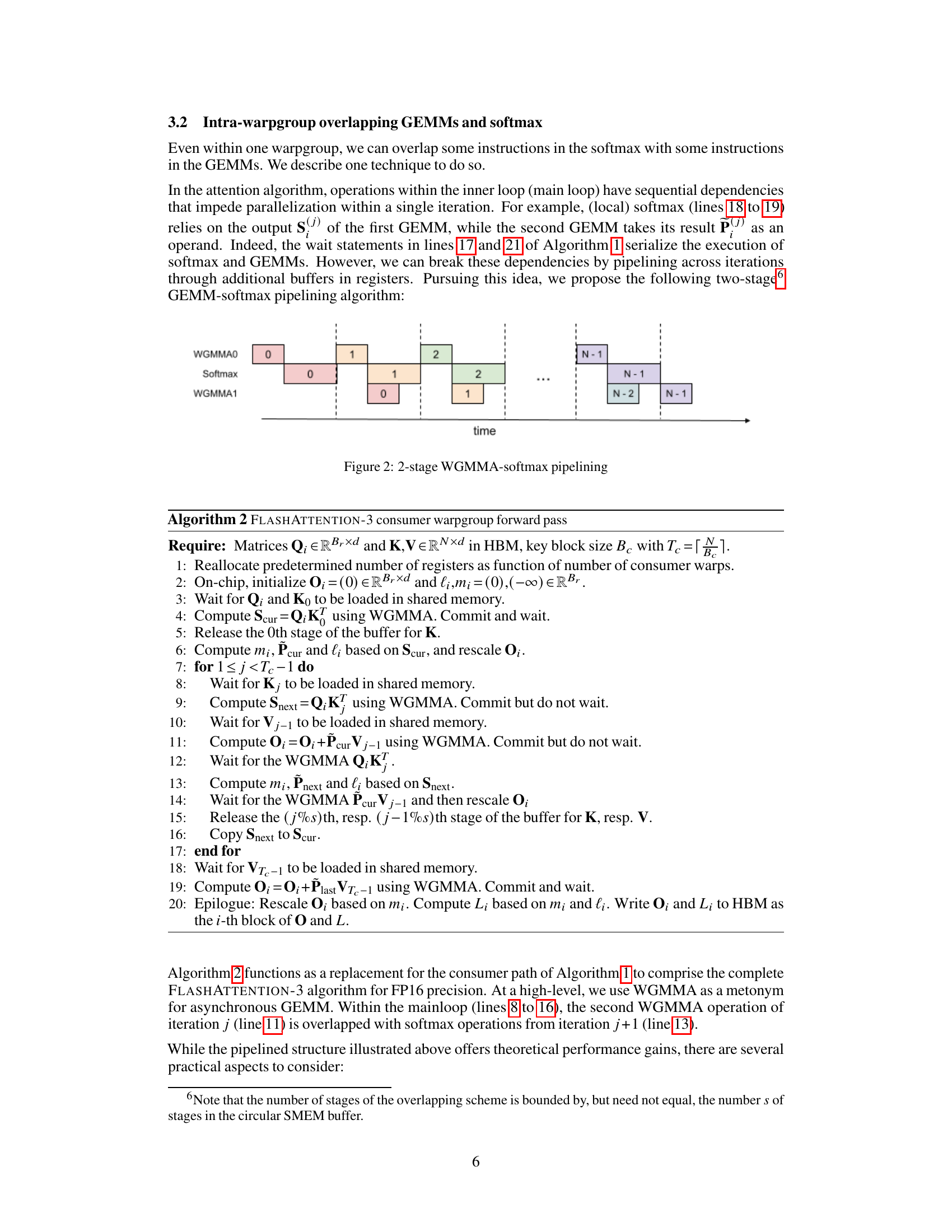

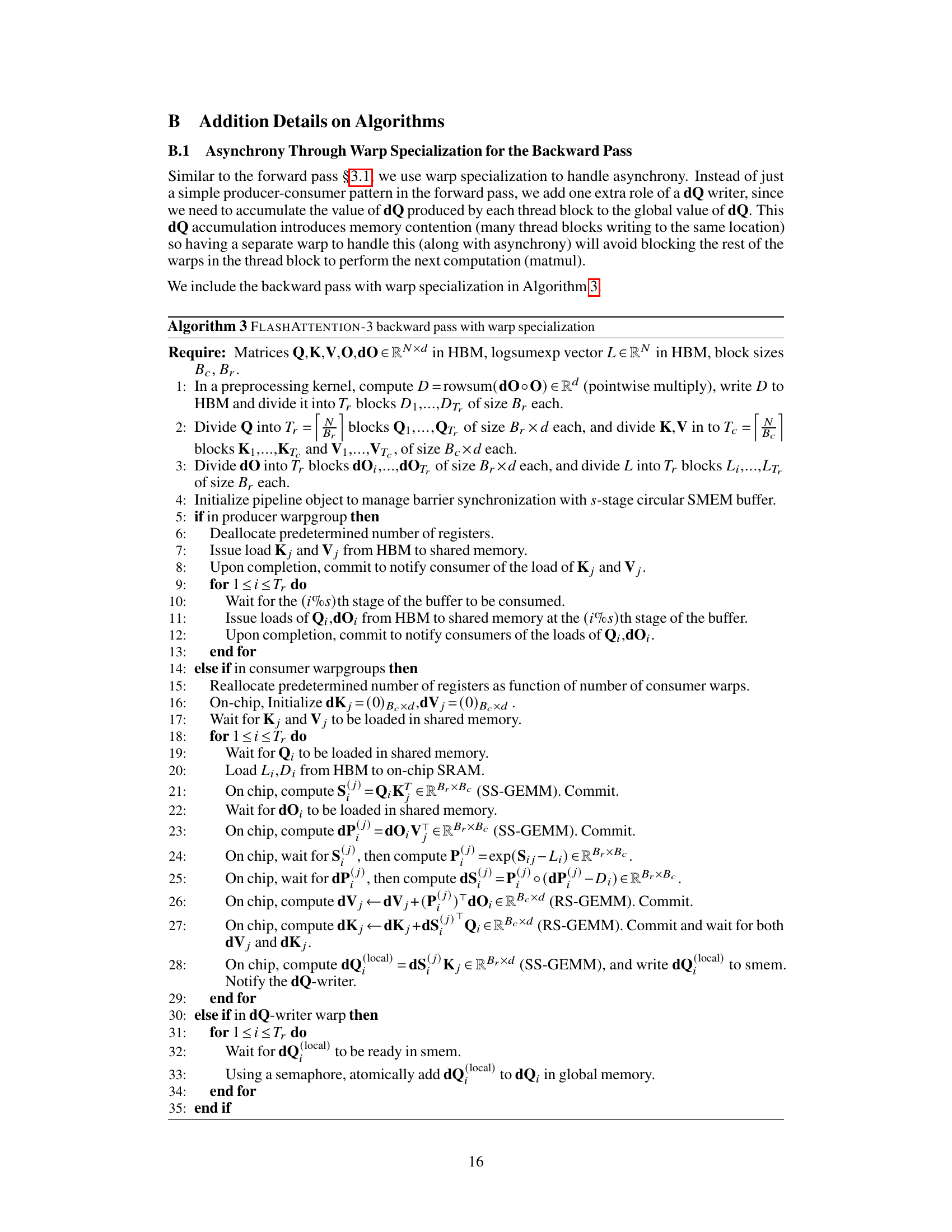

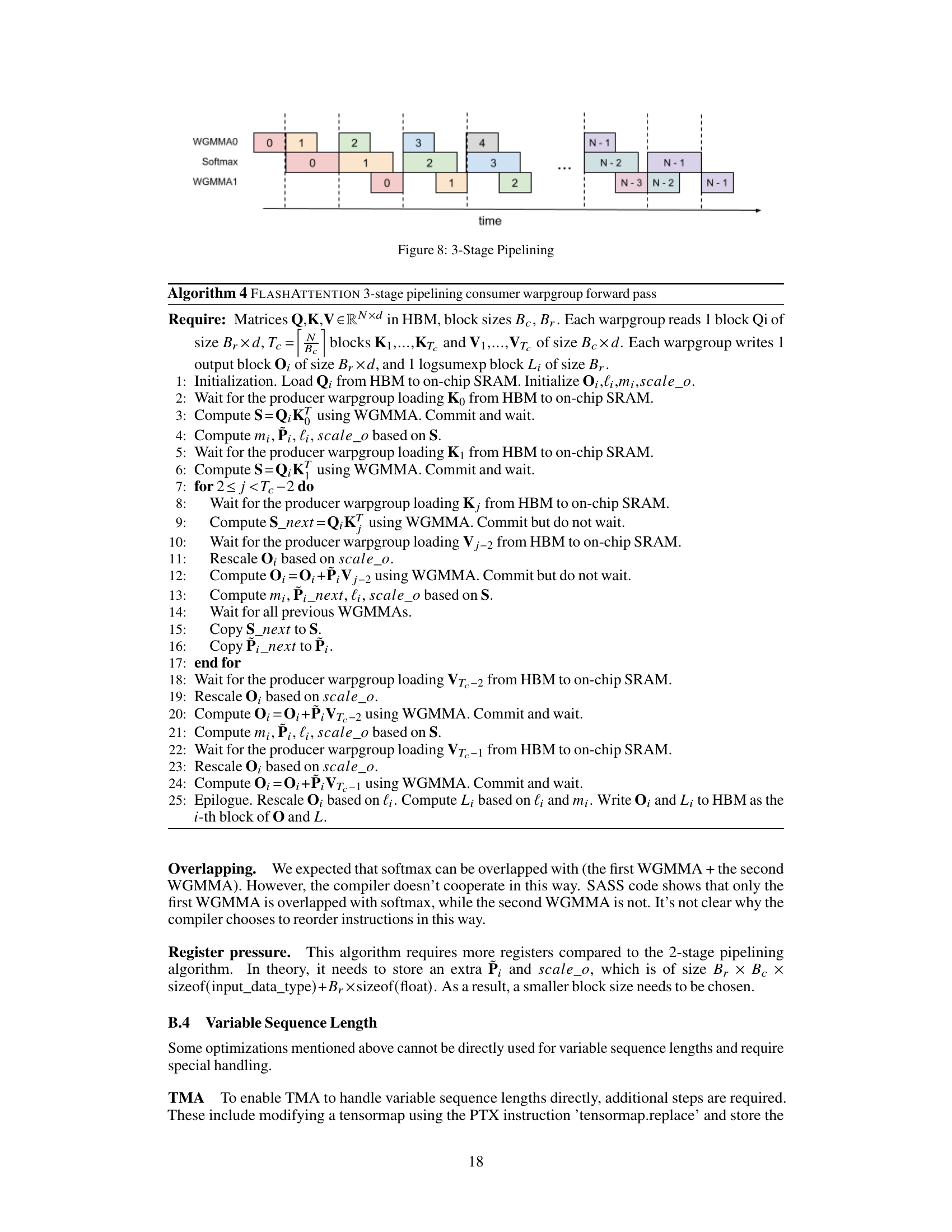

This figure illustrates the 2-stage pipelining scheme used to overlap GEMMs and softmax computations. The horizontal axis represents time, and the vertical axis shows the different stages of the algorithm (WGMMA0, Softmax, WGMMA1). The colored blocks represent the execution of different operations. The figure shows how the softmax operations of one iteration are overlapped with the GEMM operations of the next iteration, effectively hiding the latency of the softmax operations and improving efficiency. Note the pipelining effect between consecutive iterations.

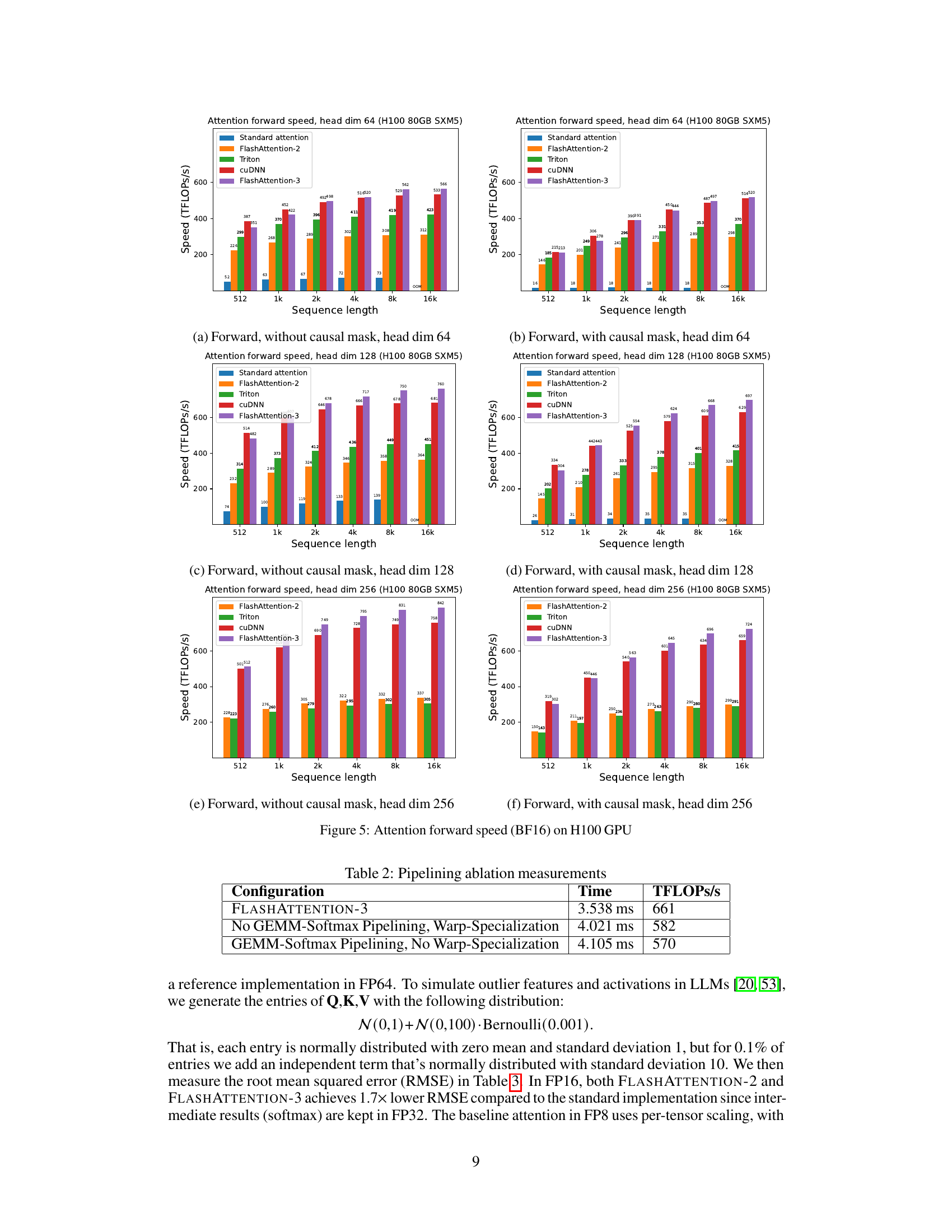

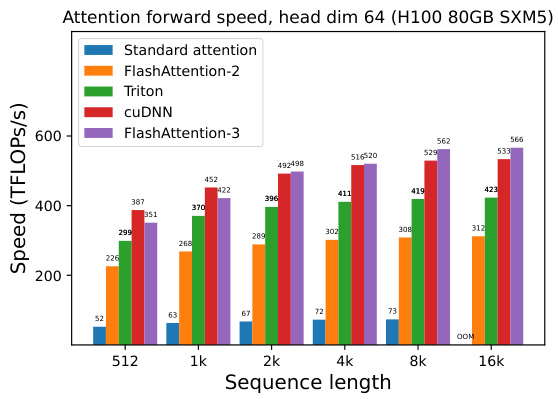

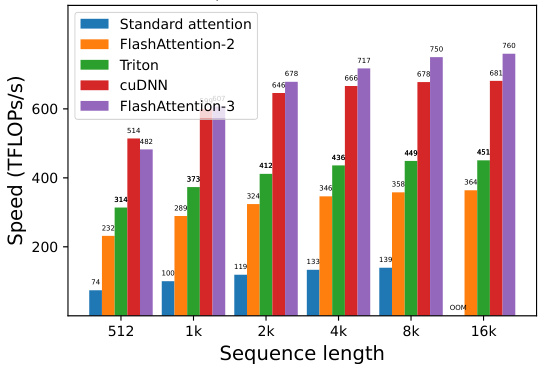

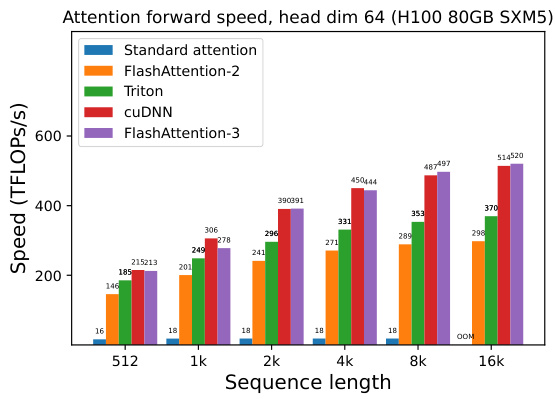

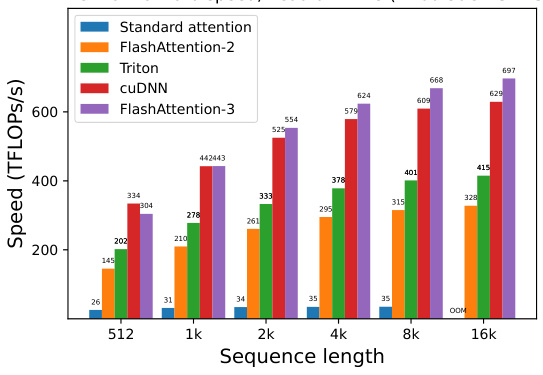

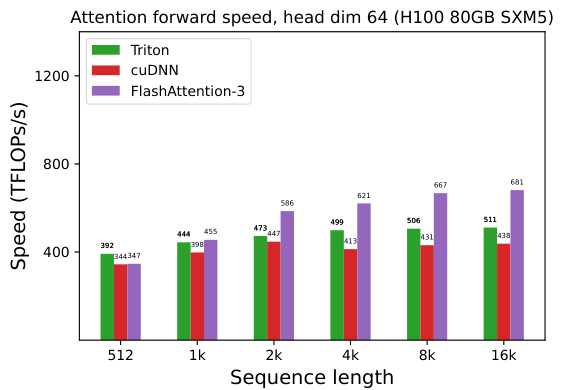

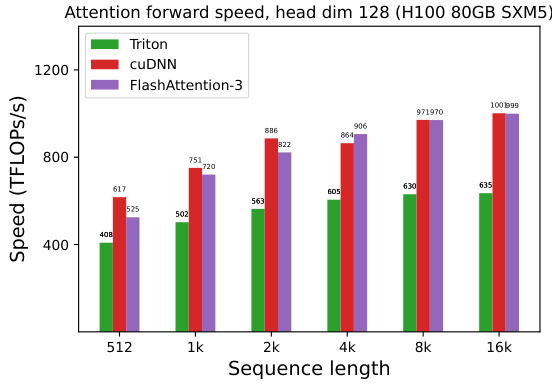

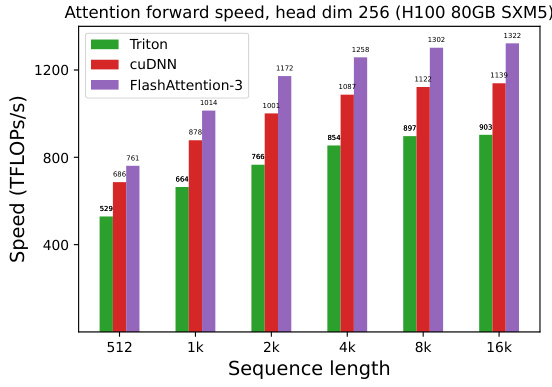

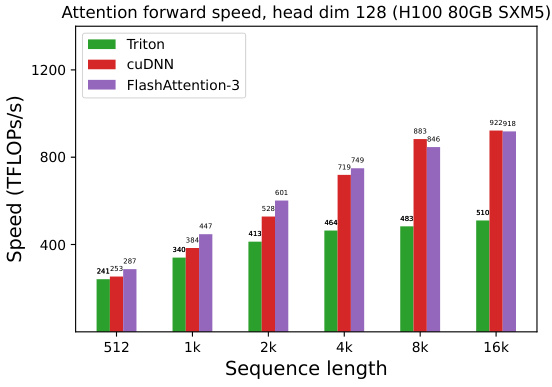

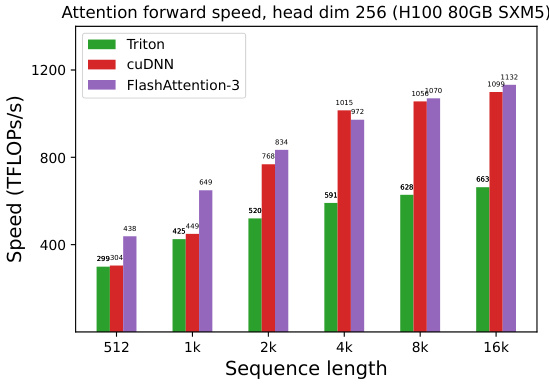

This figure compares the forward pass speed of different attention methods on an NVIDIA H100 GPU for various sequence lengths and head dimensions. The methods compared include standard attention, FlashAttention-2, FlashAttention-2 implemented in Triton, cuDNN’s optimized implementation, and FlashAttention-3. The results are shown separately for different causal mask settings (with and without) and head dimensions (64 and 128). FlashAttention-3 demonstrates significant speed improvements over other methods, especially at longer sequence lengths.

This figure presents a comparison of the forward pass speed (in TFLOPs/s) of different attention mechanisms on an NVIDIA H100 GPU using BF16 precision. The sequence length varies from 512 to 16k, and different head dimensions (64, 128, and 256) are considered, both with and without causal masking. The compared methods are standard attention, FlashAttention-2, FlashAttention-2 implemented in Triton, cuDNN’s optimized attention, and FlashAttention-3. FlashAttention-3 consistently demonstrates significant performance gains across all configurations.

This figure shows the results of benchmarking attention forward speed using BF16 precision on an NVIDIA H100 80GB SXM5 GPU. It compares the performance of FlashAttention-3 against standard attention, FlashAttention-2, its Triton implementation, and cuDNN. The benchmark is performed across different sequence lengths and with or without causal masking, and for head dimensions of 64, 128, and 256. The results demonstrate that FlashAttention-3 significantly outperforms other methods, especially for longer sequences.

This figure presents a comparison of the forward pass speed of different attention methods (Standard Attention, FlashAttention-2, Triton, cuDNN, and FlashAttention-3) using BF16 precision on an NVIDIA H100 80GB SXM5 GPU. The comparison is made across varying sequence lengths (512, 1k, 2k, 4k, 8k, 16k) and with different head dimensions (64 and 128), both with and without causal masking. The results illustrate the performance improvements achieved by FlashAttention-3, particularly for longer sequences.

This figure presents the forward pass speed of different attention methods using BF16 precision on an NVIDIA H100 GPU. The sequence length varies from 512 to 16k, and the head dimension is either 64 or 128, both with and without causal masking. The graph shows that FlashAttention-3 consistently outperforms other methods, including a standard attention implementation, FlashAttention-2, and optimized versions from Triton and cuDNN, especially as sequence length increases.

This figure shows the speed of different attention methods in terms of TFLOPS/s on an NVIDIA H100 GPU using BF16 precision. The sequence length varies from 512 to 16k, and different head dimensions (64, 128, and 256) are also tested with and without causal masks. The figure compares the performance of FlashAttention-3 with FlashAttention-2, Triton, and cuDNN implementations. FlashAttention-3 shows significantly faster performance than the others.

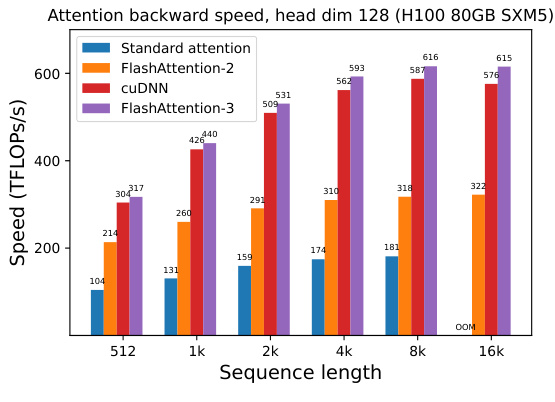

This figure presents the results of benchmarking the backward pass of attention using BF16 precision on an NVIDIA H100 80GB SXM5 GPU. The benchmark compares the speed (in TFLOPs/s) of four different methods: standard attention, FlashAttention-2, cuDNN, and FlashAttention-3. The results are shown for various sequence lengths (512, 1k, 2k, 4k, 8k, 16k) and a fixed head dimension of 64. It demonstrates the speed improvements achieved by FlashAttention-3 over existing methods.

This figure compares the backward pass speed of different attention methods (Standard attention, FlashAttention-2, cuDNN, and FlashAttention-3) on the H100 GPU using BF16 precision. The x-axis shows the sequence length, and the y-axis represents the speed in TFLOPS/s. The results are shown for different head dimensions (64 and 128). It demonstrates that FlashAttention-3 outperforms other methods across various sequence lengths.

This figure presents the forward pass speed of different attention methods (Standard Attention, FlashAttention-2, FlashAttention-2 in Triton, cuDNN, and FlashAttention-3) using BF16 precision on an NVIDIA H100 80GB SXM5 GPU. The speeds are shown for varying sequence lengths (512, 1k, 2k, 4k, 8k, 16k) and head dimensions (64 and 128), with and without causal masking. It demonstrates the speedup achieved by FlashAttention-3 compared to other methods.

This figure presents a comparison of the forward pass speed (in TFLOPs/s) of different attention mechanisms on an NVIDIA H100 80GB SXM5 GPU. The comparison includes standard attention, FlashAttention-2, FlashAttention-2 implemented using Triton, cuDNN’s optimized implementation of FlashAttention-2, and FlashAttention-3. The results are shown for various sequence lengths and head dimensions (64, 128, and 256), with and without causal masking. FlashAttention-3 consistently demonstrates superior performance across all tested configurations.

This figure illustrates the 2-stage WGMMA-softmax pipelining technique. It shows how the softmax computation for one iteration can overlap with the GEMM (WGMMA) computations for the next iteration, improving performance by hiding the latency of the softmax operation. The diagram depicts the pipelined execution of GEMM0, softmax, and GEMM1 operations across multiple iterations (0 to N-1).

This figure illustrates the ping-pong scheduling mechanism used in FlashAttention-3 to overlap softmax and GEMM operations. Two warpgroups alternate between performing GEMM and softmax calculations, maximizing hardware utilization. The colors represent the same iteration in different warpgroups, showing how the operations are interleaved.

This figure presents the results of benchmarking the forward pass of attention using BF16 precision on an NVIDIA H100 80GB SXM5 GPU. It compares the speed (in TFLOPS/s) of four different methods across varying sequence lengths and head dimensions: Standard Attention, FlashAttention-2, FlashAttention-2 in Triton (optimized for H100 using specific instructions), and FlashAttention-3. The results show that FlashAttention-3 consistently outperforms the other methods, demonstrating a significant speedup. The chart also considers the effect of causal masking (a technique used in certain types of sequence modeling).

This figure compares the forward pass speed of different attention methods (standard attention, FlashAttention-2, FlashAttention-2 in Triton, cuDNN, and FlashAttention-3) on an NVIDIA H100 GPU with different sequence lengths (512, 1k, 2k, 4k, 8k, 16k) and head dimensions (64 and 128). It shows the speed in TFLOPS/s for both causal and non-causal settings.

This figure compares the forward pass speed of four different attention implementations (Standard Attention, FlashAttention-2, FlashAttention-2 in Triton, cuDNN, and FlashAttention-3) across various sequence lengths (512, 1k, 2k, 4k, 8k, 16k) and head dimensions (64, 128, 256). Both causal and non-causal mask settings are shown, providing a comprehensive performance comparison under different conditions. The speed is measured in TFLOPs/s (Tera Floating Point Operations per second), a common metric for GPU performance. FlashAttention-3 consistently demonstrates superior performance across all scenarios.

This figure presents a comparison of the forward pass speed (in TFLOPs/s) of different attention methods on an NVIDIA H100 GPU using BF16 precision. The comparison includes Standard Attention, FlashAttention-2, FlashAttention-2 (Triton), cuDNN, and FlashAttention-3. The speed is measured across various sequence lengths (512, 1k, 2k, 4k, 8k, 16k) and with two head dimensions (64 and 128), both with and without causal masking. The results demonstrate the performance improvements achieved by FlashAttention-3.

This figure shows the forward pass speed of different attention methods (Standard Attention, FlashAttention-2, FlashAttention-2 in Triton, cuDNN, and FlashAttention-3) on an NVIDIA H100 GPU with BF16 precision. The speed is measured in TFLOPS/s and is plotted against the sequence length. The experiments were performed with both causal and non-causal masking options for head dimensions of 64, 128, and 256.

This figure shows the speed of the forward pass of attention using BF16 precision on an NVIDIA H100 GPU, comparing different methods: Standard Attention, FlashAttention-2, FlashAttention-2 in Triton, cuDNN (NVIDIA’s library), and FlashAttention-3. The results are shown for various sequence lengths and head dimensions (64, 128, and 256), with and without causal masking. FlashAttention-3 demonstrates significantly faster speeds compared to other methods, especially as sequence length increases.

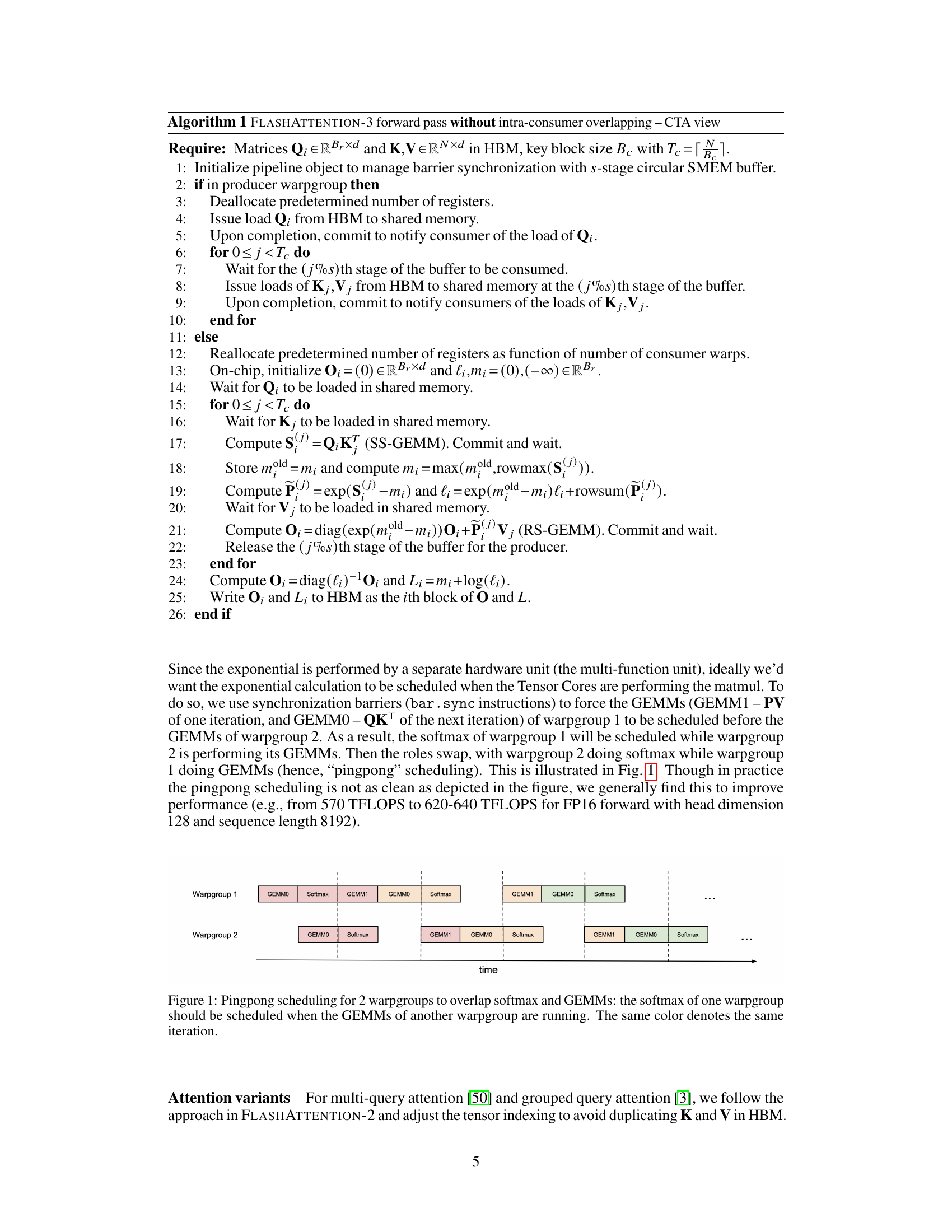

More on tables

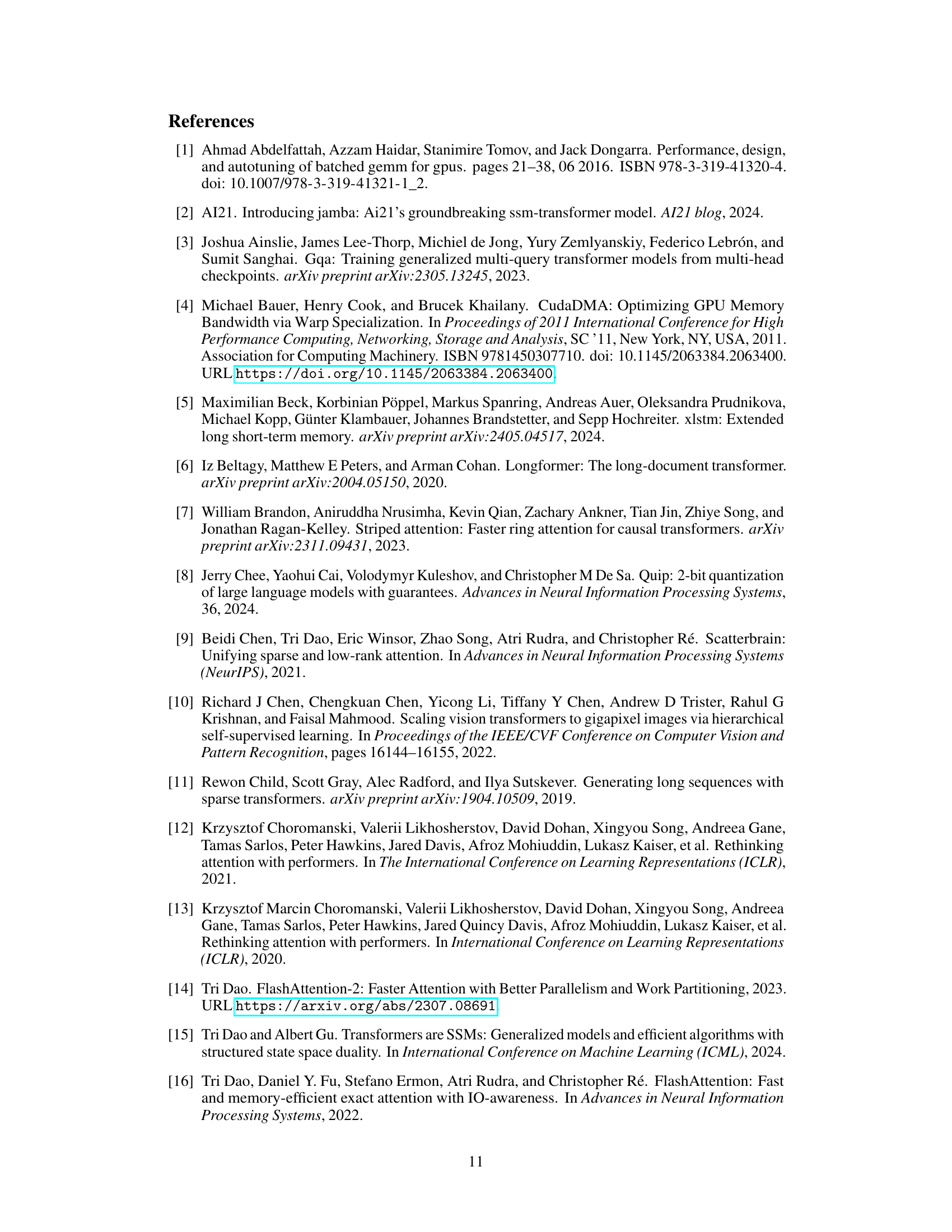

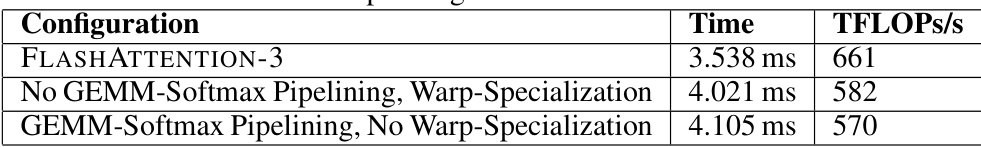

This table presents the results of an ablation study to evaluate the impact of two key techniques, GEMM-Softmax pipelining and warp specialization, on the performance of FLASHATTENTION-3. It shows the time taken and the TFLOPs/s achieved for three configurations: FLASHATTENTION-3 with both techniques, FLASHATTENTION-3 without GEMM-Softmax pipelining, and FLASHATTENTION-3 without warp specialization. The results demonstrate the individual and combined contributions of these optimization strategies.

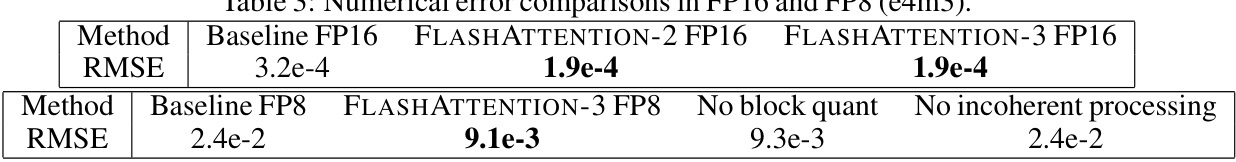

This table presents the root mean squared error (RMSE) for different attention methods using FP16 and FP8 precision. The baseline FP16 represents a standard attention implementation. FLASHATTENTION-2 and FLASHATTENTION-3 are improved attention methods. The table demonstrates the error reduction achieved by FLASHATTENTION-3 with FP16, and also shows the effects of block quantization and incoherent processing on the accuracy of the FP8 version of FLASHATTENTION-3.

Full paper#