↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current protein language model (PLM) training often focuses on increasing model size, neglecting compute-budget optimization. This leads to diminishing returns and overfitting issues. The lack of comprehensive scaling laws tailored to protein sequence data also hampers efficient PLM development. This research aims to address these issues.

This study introduces novel scaling laws for PLMs, addressing the limitations of existing methods. It utilizes a massive protein sequence dataset including metagenomic sequences to enhance diversity and training efficiency. Experiments reveal the efficacy of transfer learning between different PLM training objectives, offering an optimized training strategy with equivalent pre-training compute budgets. These findings offer practical guidelines for building compute-optimal PLMs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for AI researchers in biology due to its novel scaling laws for protein language models (PLMs). It provides practical guidance for optimally allocating compute resources, improving model training efficiency and performance. The findings will significantly impact the development of more powerful and effective PLMs, furthering research in protein design and understanding.

Visual Insights#

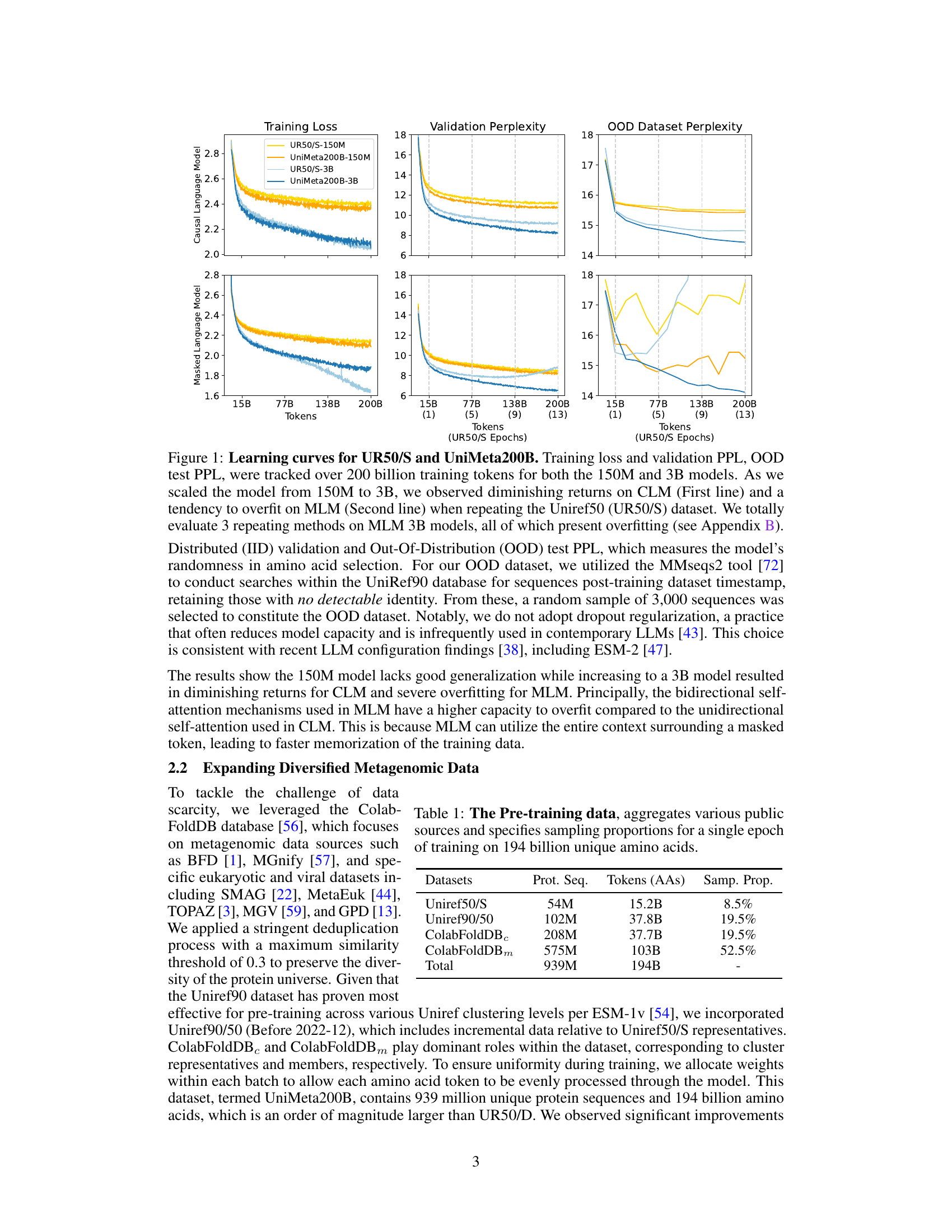

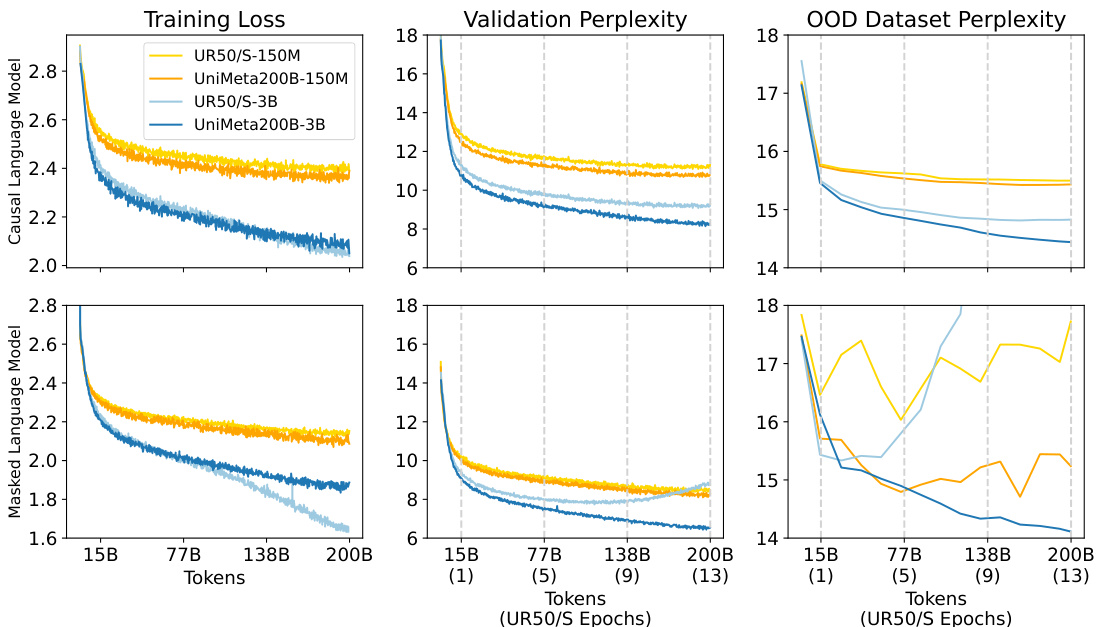

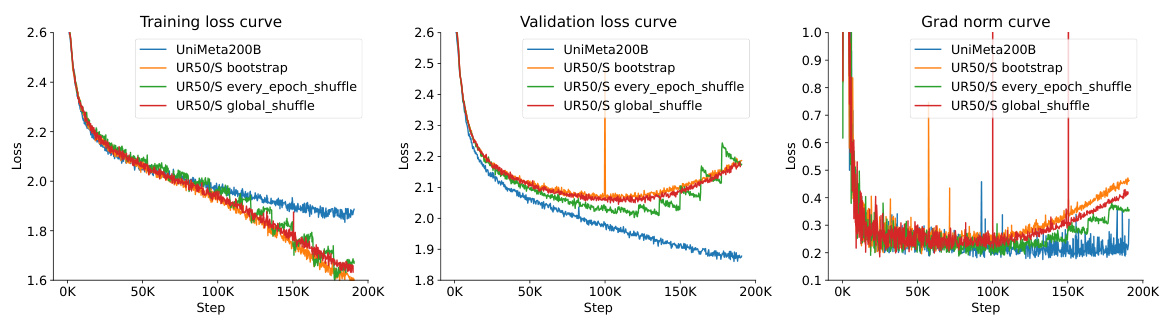

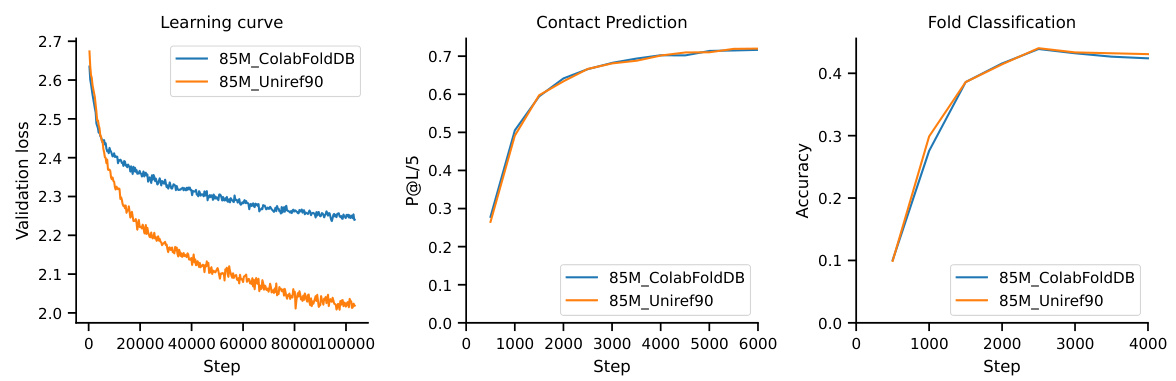

This figure displays the learning curves for two different models (150M and 3B parameters) trained on two datasets (UR50/S and UniMeta200B), showing the effects of model size and dataset size on performance. The results demonstrate diminishing returns for the Causal Language Model (CLM) and overfitting for the Masked Language Model (MLM) when using the UR50/S dataset repeatedly. The UniMeta200B dataset mitigated these issues.

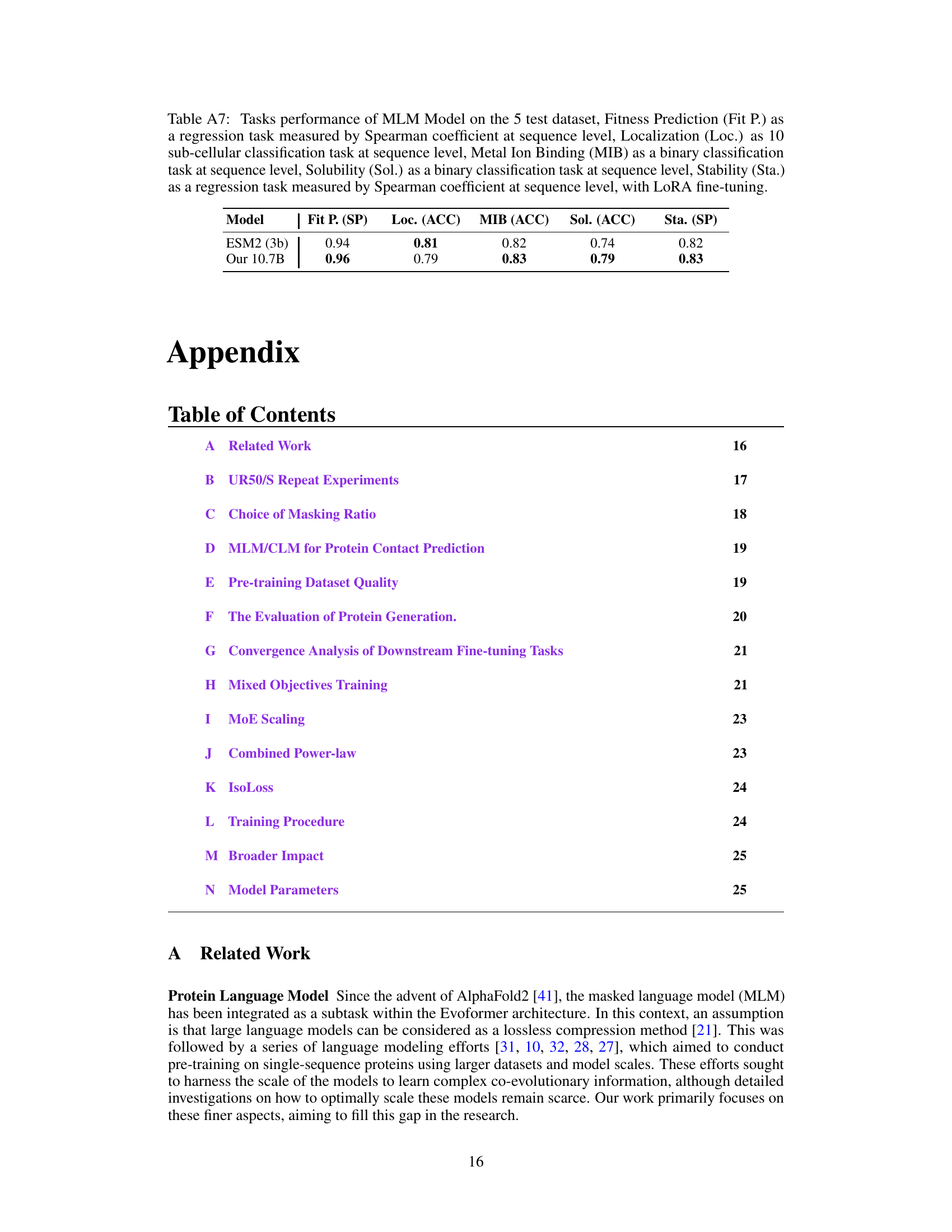

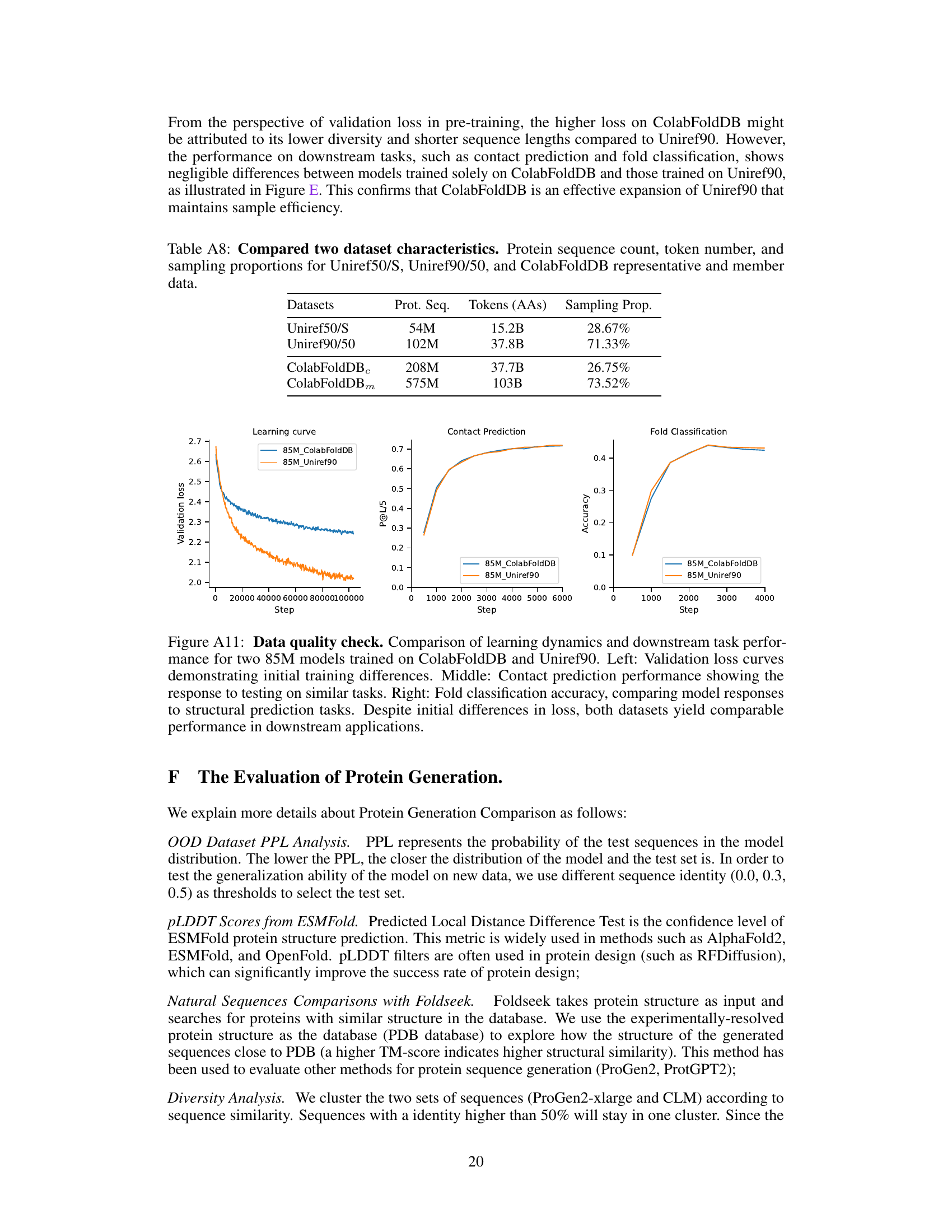

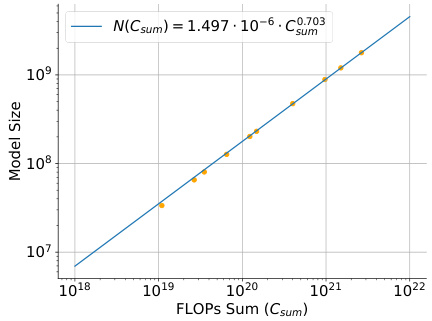

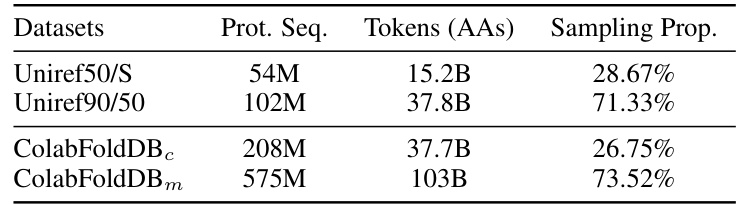

This table presents the composition of the pre-training dataset UniMeta200B. It lists four datasets used: Uniref50/S, Uniref90/50, ColabFoldDBC, and ColabFoldDBm. For each dataset, the number of protein sequences (‘Prot. Seq.’), the number of amino acid tokens (‘Tokens (AAs)’), and the sampling proportion (‘Samp. Prop.’) within the dataset are provided. The total number of protein sequences and tokens are also given at the end.

In-depth insights#

Compute-Optimal PLMs#

The concept of “Compute-Optimal PLMs” centers on efficiently training large protein language models (PLMs) by optimizing the balance between model performance and computational resources. Instead of solely focusing on increasing model size, this approach emphasizes finding the most effective compute budget for a desired performance level. Key strategies involve careful dataset selection to avoid overfitting and diminishing returns, using diverse and expansive metagenomic data to enhance model generalization. The authors explore and establish scaling laws tailored to protein sequence data for both Causal Language Models (CLMs) and Masked Language Models (MLMs), identifying optimal training token numbers for different model sizes. A significant finding highlights the transferability of knowledge between CLM and MLM pre-training, demonstrating potential compute savings through strategic allocation of training resources. This research ultimately provides a valuable framework for training powerful PLMs while managing computational costs effectively. The work provides practical guidelines to improve downstream task performances using less or equivalent pre-training compute budgets.

Metagenomic Data#

The integration of metagenomic data significantly enhances protein language models. Metagenomic data provides a far broader and more diverse representation of protein sequences than traditional databases like UniRef. This increased diversity is crucial for mitigating overfitting and diminishing returns often observed when training on limited, repetitive datasets. By including metagenomic sequences, the model gains exposure to a wider range of evolutionary patterns and sequence variations, leading to improved generalization and performance in downstream tasks. The resulting models are less likely to overfit on the training data and exhibit enhanced robustness when evaluated on unseen protein sequences. This approach addresses a key limitation in existing PLM training, namely, data scarcity and lack of diversity. Thus, incorporating metagenomic data is a critical step in advancing the field of protein language modeling towards more accurate and robust predictive capabilities.

Scaling Laws#

The concept of ‘scaling laws’ in the context of large language models (LLMs) is crucial for understanding how model performance changes with increased compute resources. The authors explore scaling laws specific to protein language models (PLMs), a domain with unique challenges compared to natural language. They investigate how model performance scales with both increasing model size and the amount of training data. This analysis is important because it helps determine the optimal balance between model size and training data to maximize performance for a given computational budget. Their findings reveal distinct power-laws for causal and masked language models (CLMs and MLMs), suggesting that resource allocation should be tailored to the specific objective. Furthermore, they demonstrate the effectiveness of transfer learning via scaling, showing that models trained with one objective (CLM) can be effectively transferred to another (MLM), optimizing resource utilization. This careful examination of scaling laws provides a valuable framework for researchers to efficiently develop and train high-performing PLMs.

Transfer Learning#

The concept of transfer learning, applied within the context of protein language models, presents a compelling avenue for enhancing model performance and efficiency. The core idea revolves around leveraging knowledge gained from training a model on one task (e.g., causal language modeling) to improve its performance on a related but different task (e.g., masked language modeling). This approach is particularly attractive when dealing with limited computational resources or datasets. The paper investigates the transferability between causal and masked language modeling objectives in protein sequence prediction, establishing scaling laws and demonstrating that knowledge transfer is particularly effective when scaling up both model size and data. Moreover, the study highlights that the transfer phenomenon is not symmetric, with benefits being more pronounced in one direction than the other, which needs further study to investigate the underlying mechanisms. The findings suggest that strategic allocation of computational resources between the source and target tasks is crucial for maximizing efficiency. This strategy is potentially applicable to other types of biological sequence data where compute resources are limited, offering a pathway for accelerating research in bioinformatics and related fields.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Expanding the dataset to include even more diverse protein sequences, potentially from less-studied organisms and environments, would enhance the generalizability and robustness of protein language models. Investigating alternative model architectures beyond transformers, such as graph neural networks or more specialized sequence models, may reveal superior performance or efficiency. The development of novel training objectives that better capture the complex relationships between protein sequence, structure, and function is a critical need. Further exploration of transfer learning techniques, especially how to effectively transfer knowledge across different tasks or datasets, is crucial for scaling these models more efficiently. Finally, focusing on improving the interpretability of the learned representations is crucial to understand the decision-making process of these models and their applications in biological discovery.

More visual insights#

More on figures

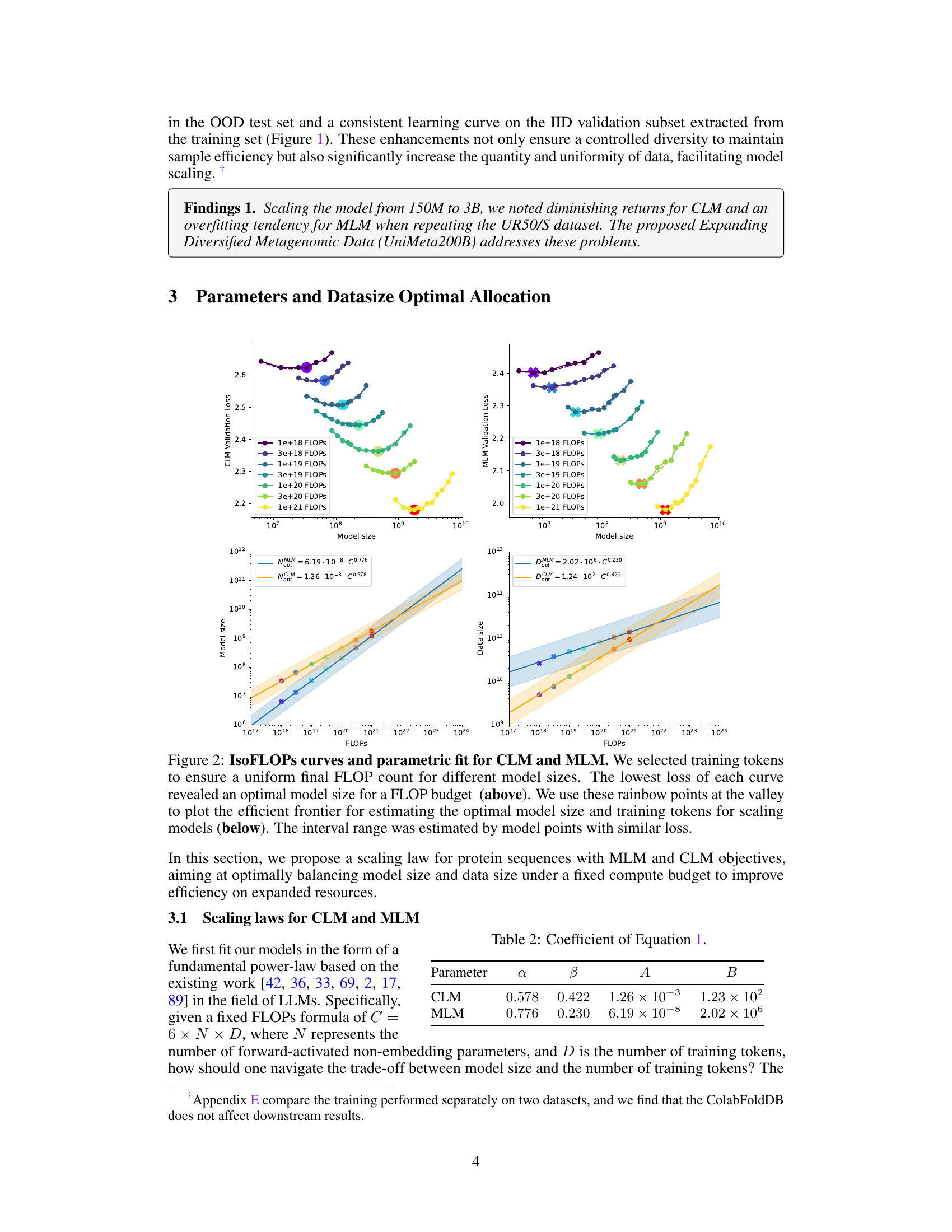

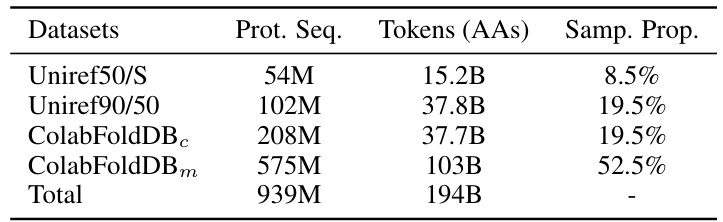

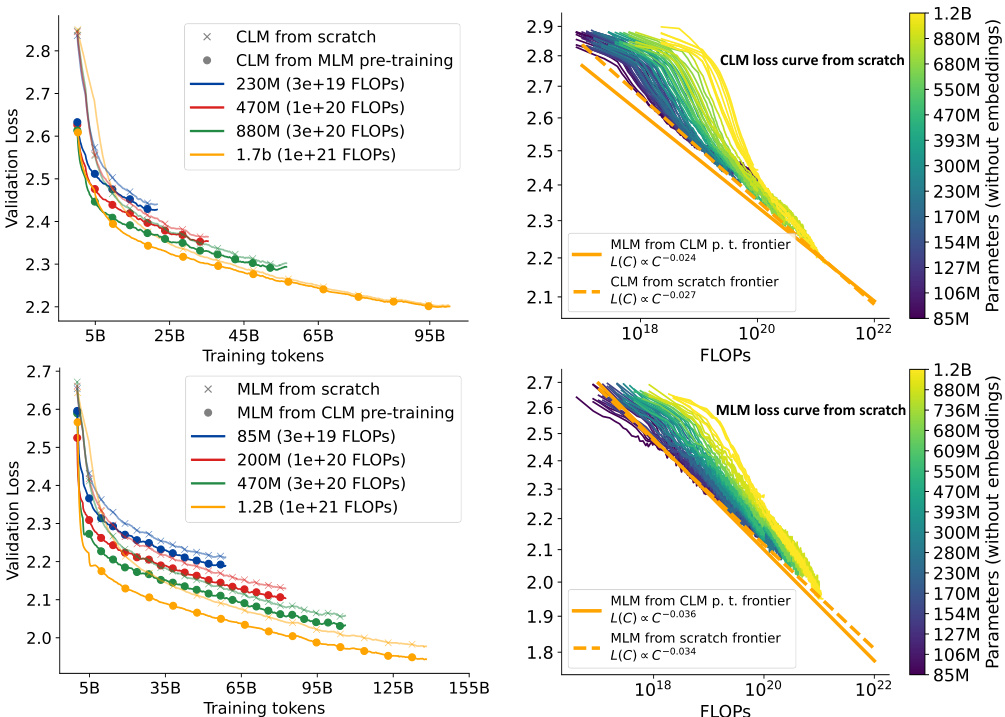

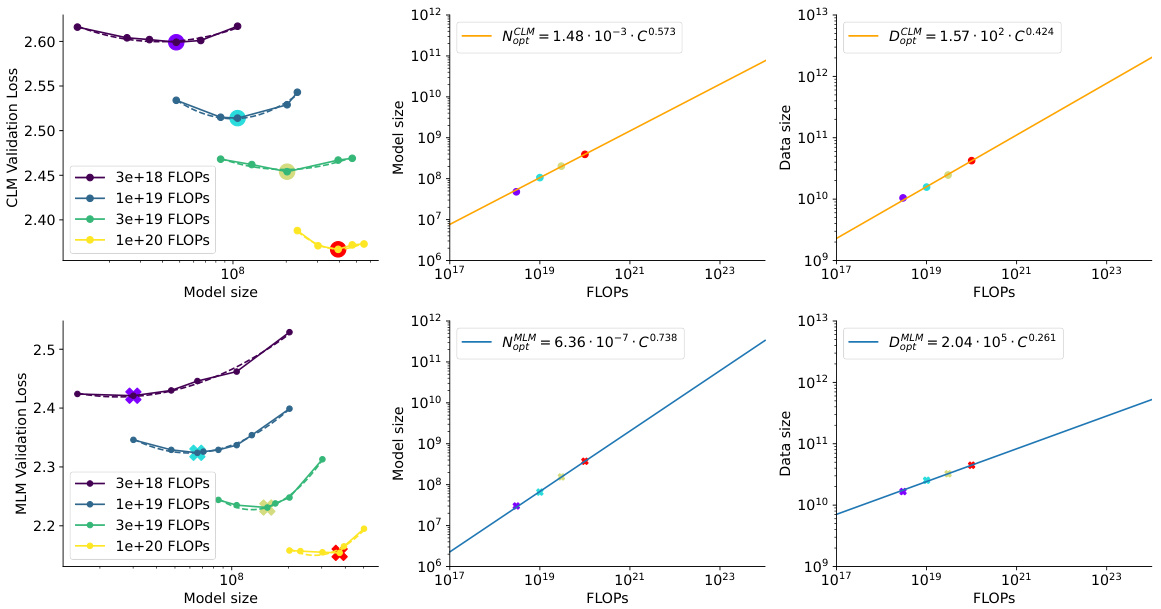

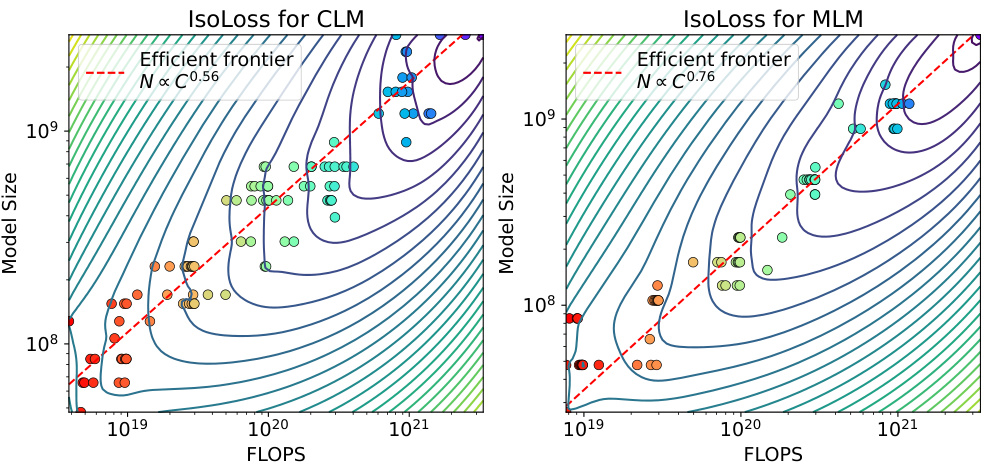

This figure shows the scaling laws for both Causal Language Model (CLM) and Masked Language Model (MLM). The upper part shows the validation loss for different model sizes under various FLOP (floating point operations) budgets. The lower part presents the efficient frontier, which illustrates the optimal model size and the number of training tokens needed to achieve the lowest loss for a given FLOP budget. The plots reveal distinct scaling relationships between model size and data size for CLM and MLM. It demonstrates that the model size grows faster than the training tokens for both models.

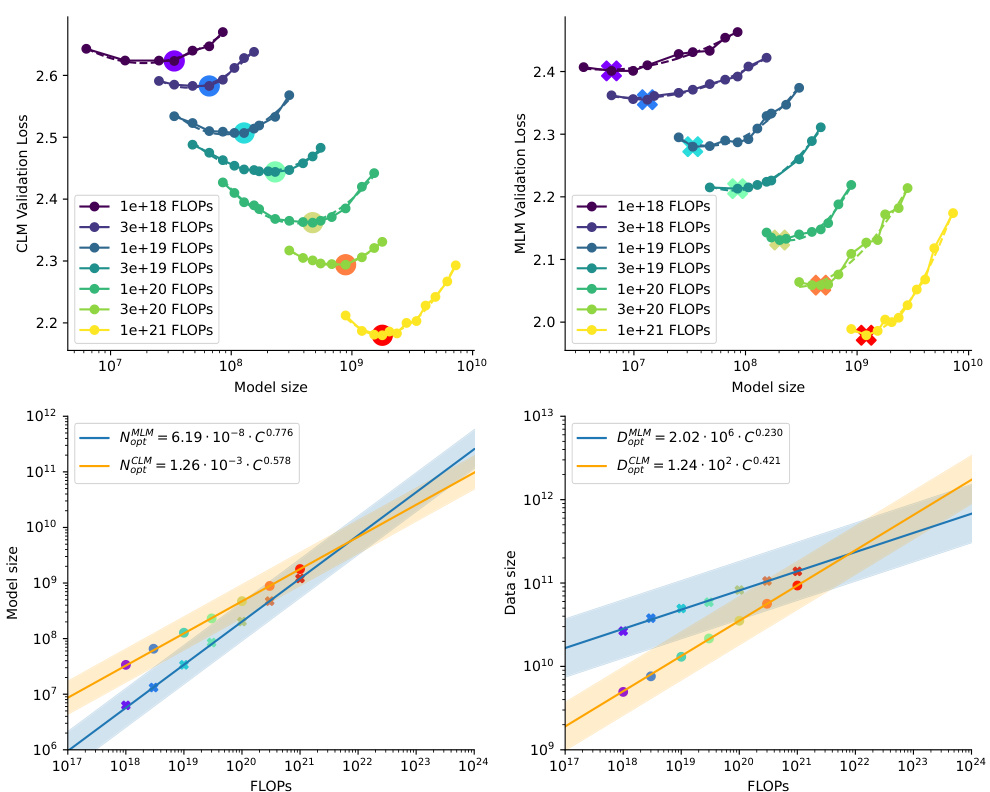

This figure shows the relationship between the total compute budget (FLOPs Sum) and the optimal model size when training both CLM and MLM models with equal model parameters. The solid line represents the power-law fit to the data points (orange dots). This figure demonstrates the strategy to allocate compute resources proportionally between CLM and MLM training when the goal is to optimize both objectives simultaneously, ensuring similar model sizes. The optimal compute allocation for a given model size is shown to ensure equal model size despite distinct power laws for each objective’s scaling.

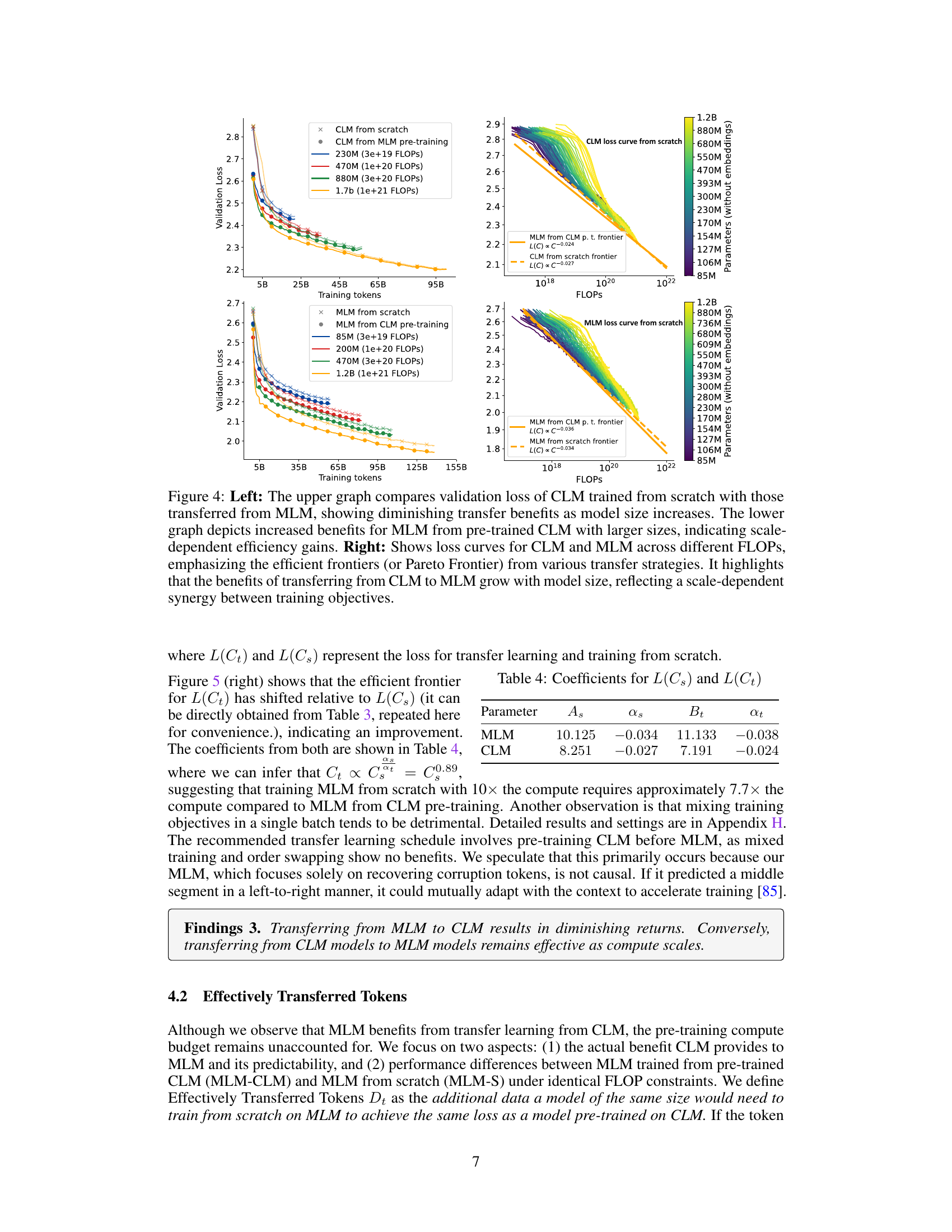

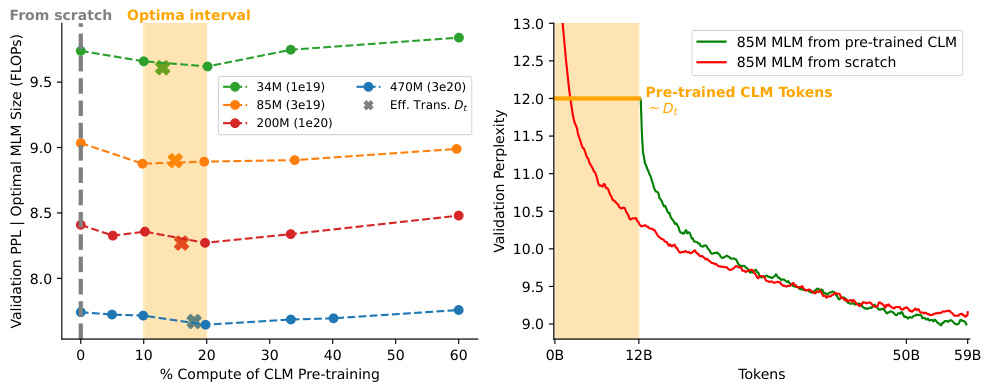

This figure shows the results of transfer learning experiments between Causal Language Model (CLM) and Masked Language Model (MLM). The left side shows that the benefit of transferring from MLM to CLM decreases as the model size increases, while the right side shows that the benefit of transferring from CLM to MLM increases with model size. The right panel also shows the efficient frontiers for CLM and MLM, highlighting the synergistic effect of training both models together.

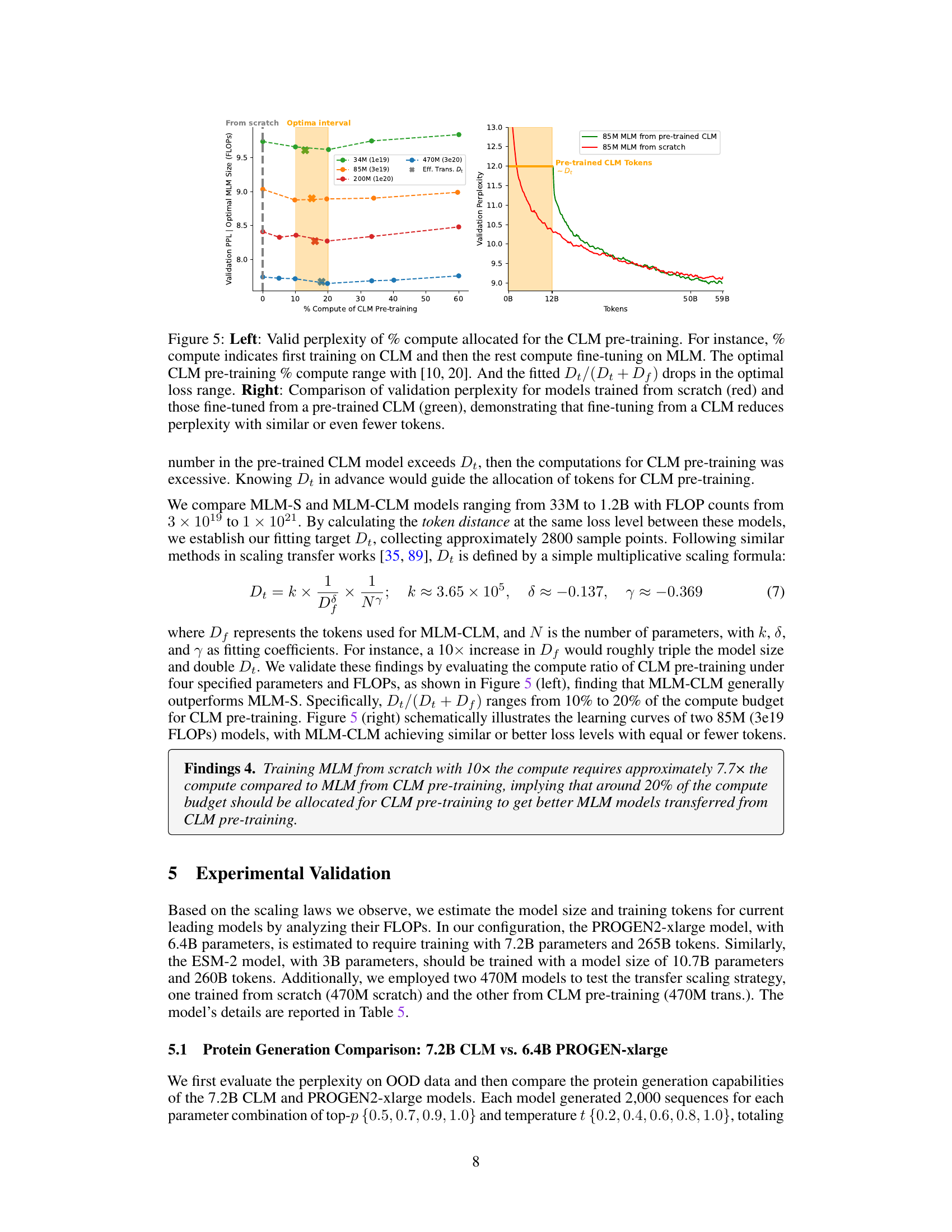

The figure displays the results of experiments assessing the impact of pre-training on CLM before fine-tuning on MLM for protein language modeling. The left panel shows how varying the percentage of compute allocated to CLM pre-training affects the validation perplexity of the final MLM model. An optimal range of 10-20% is observed. The right panel compares the validation perplexity curves for MLM models trained from scratch versus those fine-tuned from a pre-trained CLM model. The results suggest that fine-tuning from a pre-trained CLM model can lead to lower perplexity, even with a reduced number of tokens.

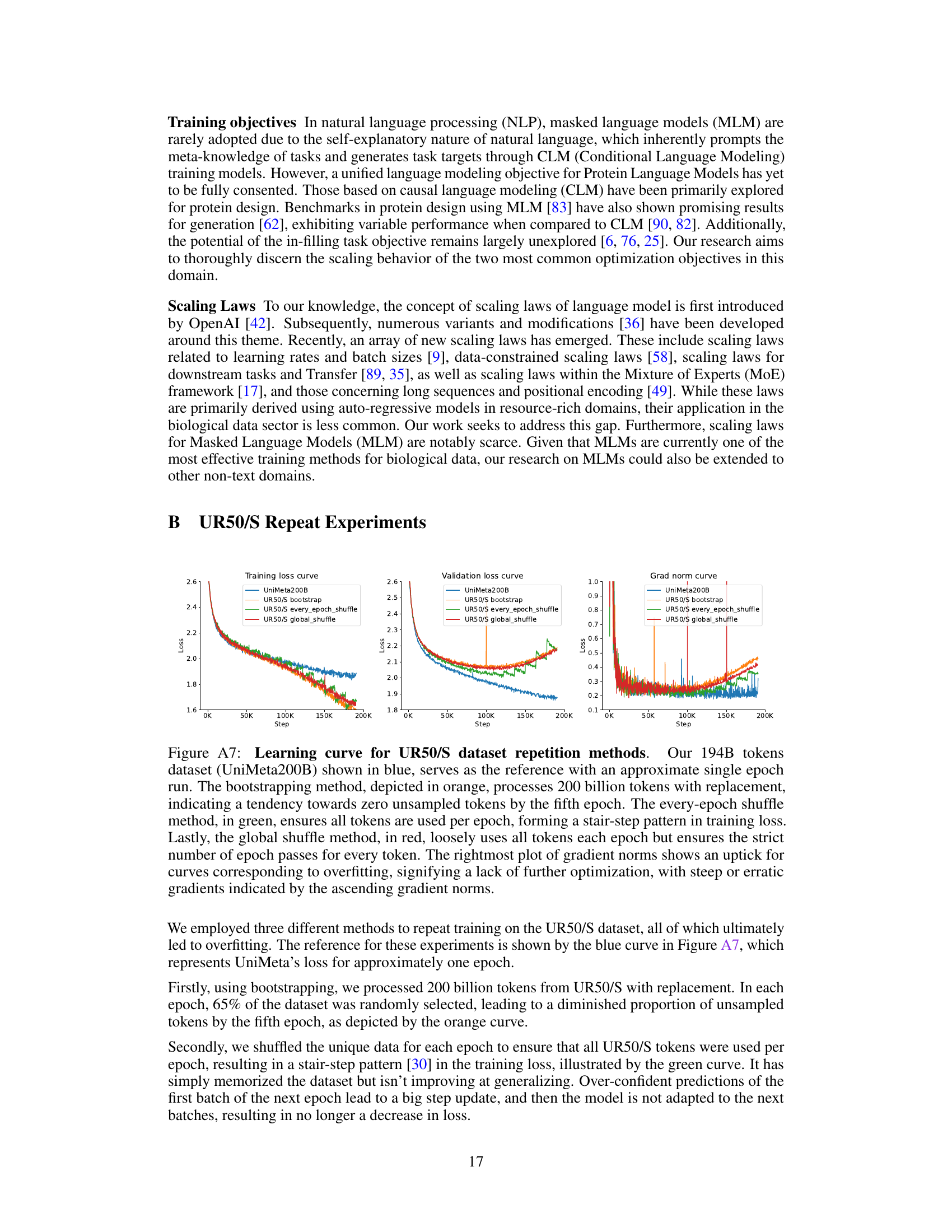

This figure shows the learning curves for two different datasets (UR50/S and UniMeta200B) and two model sizes (150M and 3B parameters) using both Causal Language Model (CLM) and Masked Language Model (MLM) objectives. The results highlight the diminishing returns of CLM and overfitting issues in MLM when using the UR50/S dataset repeatedly. This motivates the introduction of the UniMeta200B dataset to improve diversity and avoid overfitting.

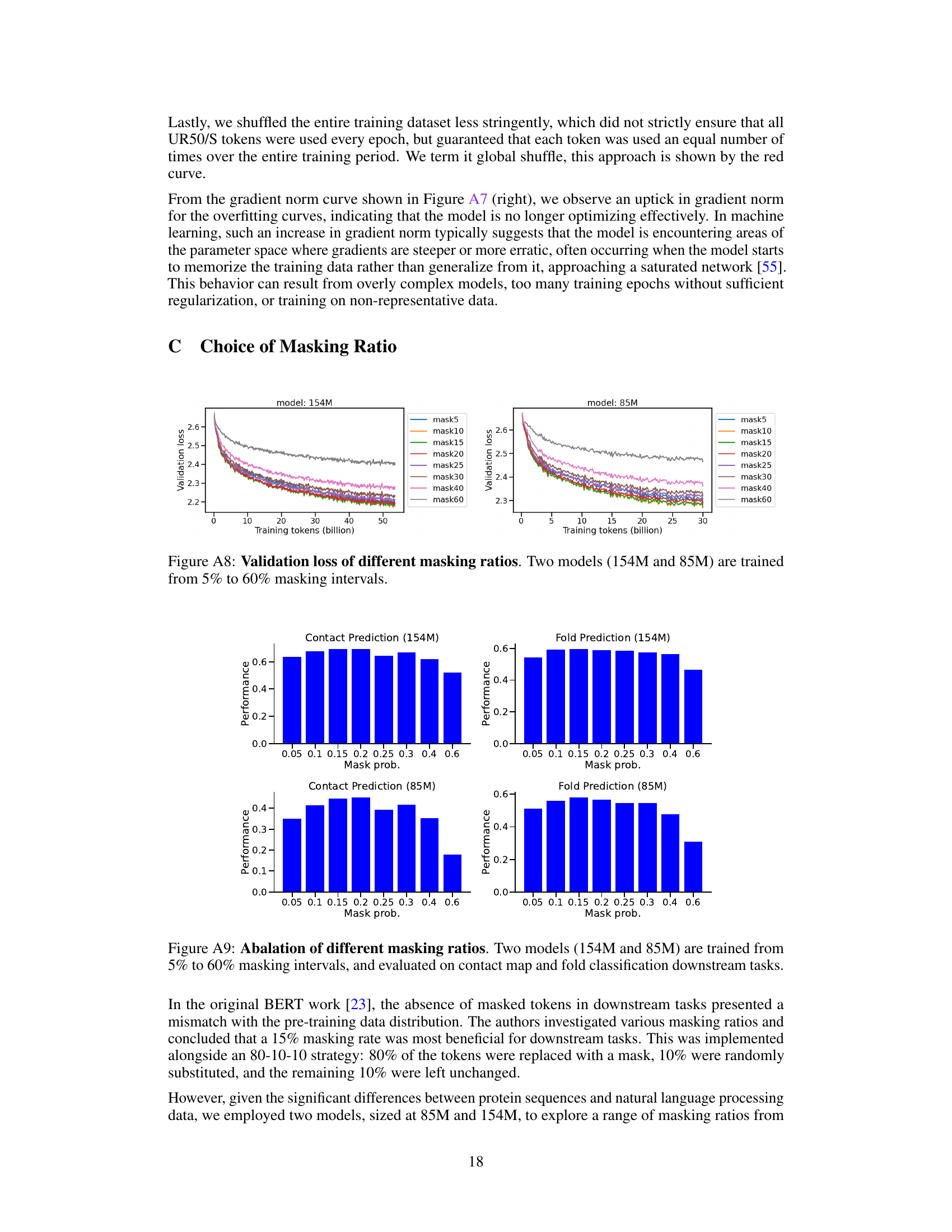

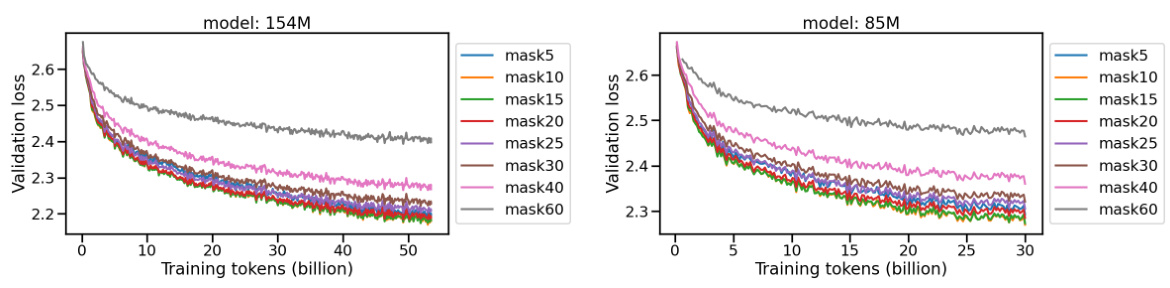

This figure displays the validation loss curves for two protein language models (154M and 85M parameters) trained with varying masking ratios. The x-axis represents the number of training tokens (in billions), and the y-axis represents the validation loss. Multiple curves are shown, each representing a different masking ratio (from 5% to 60%). The figure helps illustrate how the masking ratio, a hyperparameter in masked language modeling, affects the model’s performance during training, as measured by validation loss.

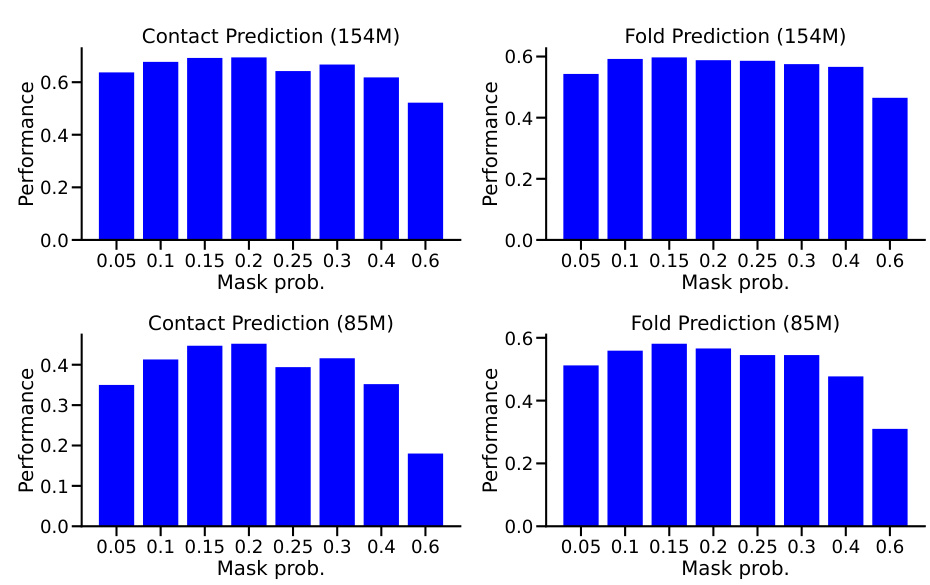

This figure shows the ablation study of different masking ratios on two models (154M and 85M). The models were trained with masking ratios ranging from 5% to 60% and then evaluated on downstream tasks, namely contact prediction and fold prediction. The results demonstrate the effect of different masking ratios on the model’s performance in these downstream tasks. The optimal performance was observed within the 10%-20% masking range, similar to the findings in NLP.

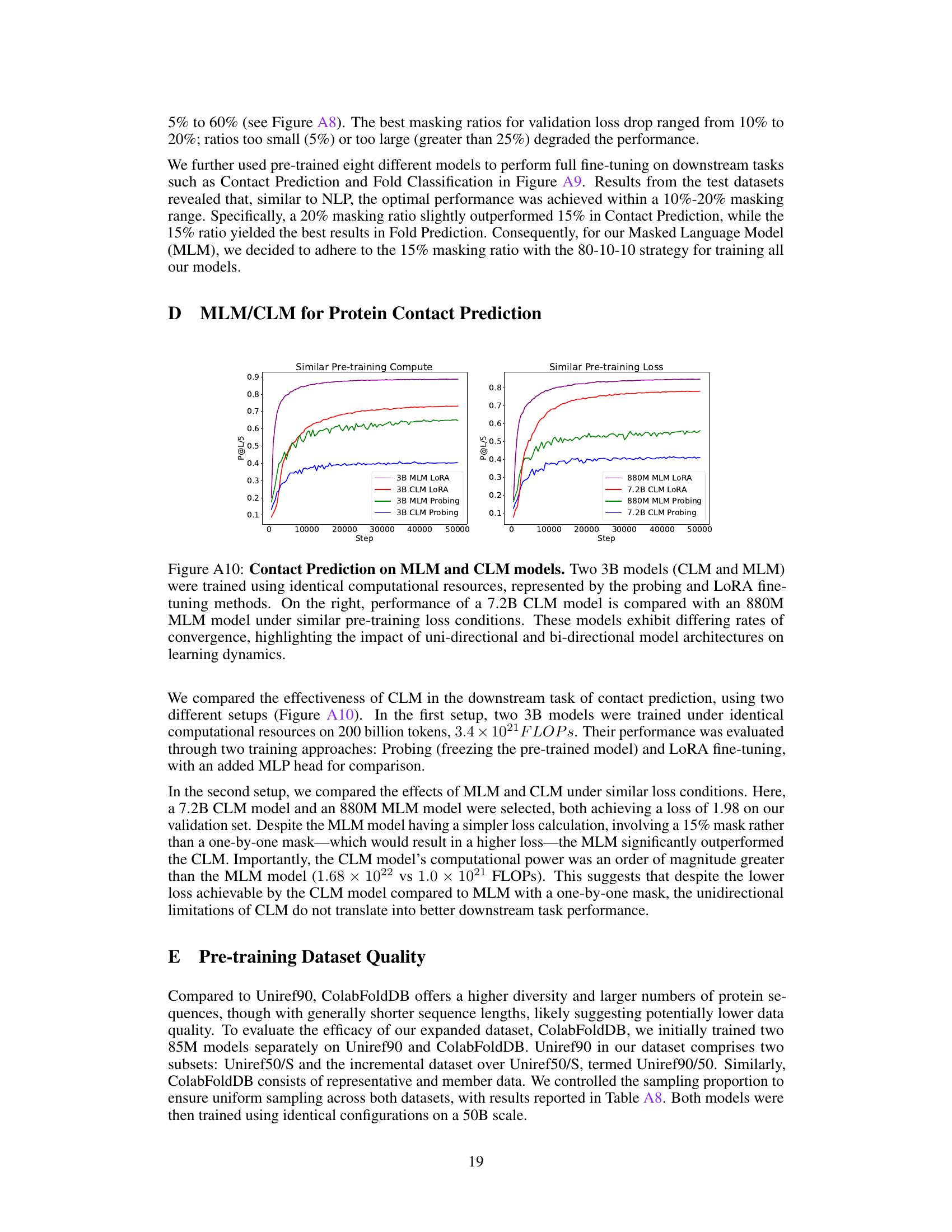

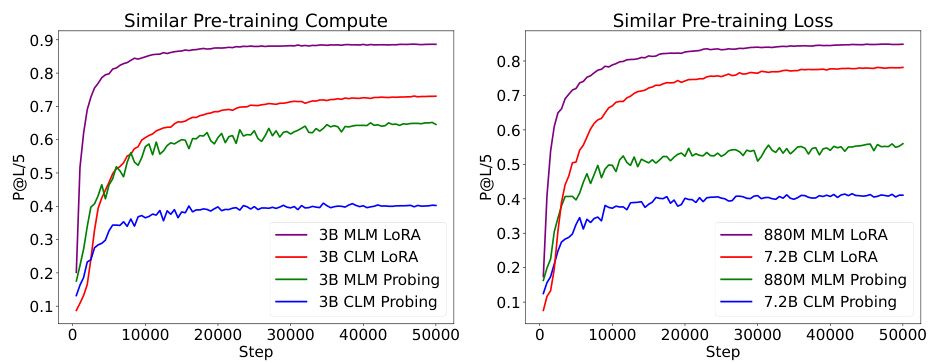

This figure compares the performance of Causal Language Models (CLM) and Masked Language Models (MLM) on the protein contact prediction task. Two 3B parameter models (one CLM and one MLM) were trained with the same computational resources, and their performance was evaluated using two methods: probing (freezing the pretrained model) and LoRA fine-tuning. The right panel shows the performance of a larger 7.2B parameter CLM model compared to an 880M parameter MLM model, both trained to achieve similar pre-training losses. The different convergence rates highlight the impact of the model architectures on learning dynamics.

This figure displays the learning curves for two different datasets (UR50/S and UniMeta200B) with two different model sizes (150M and 3B parameters). It shows how the training loss and validation perplexity change as the number of training tokens increases. It highlights that repeating the UR50/S dataset leads to diminishing returns for the Causal Language Model (CLM) and overfitting for the Masked Language Model (MLM). The UniMeta200B dataset, which includes metagenomic protein sequences, mitigates these issues.

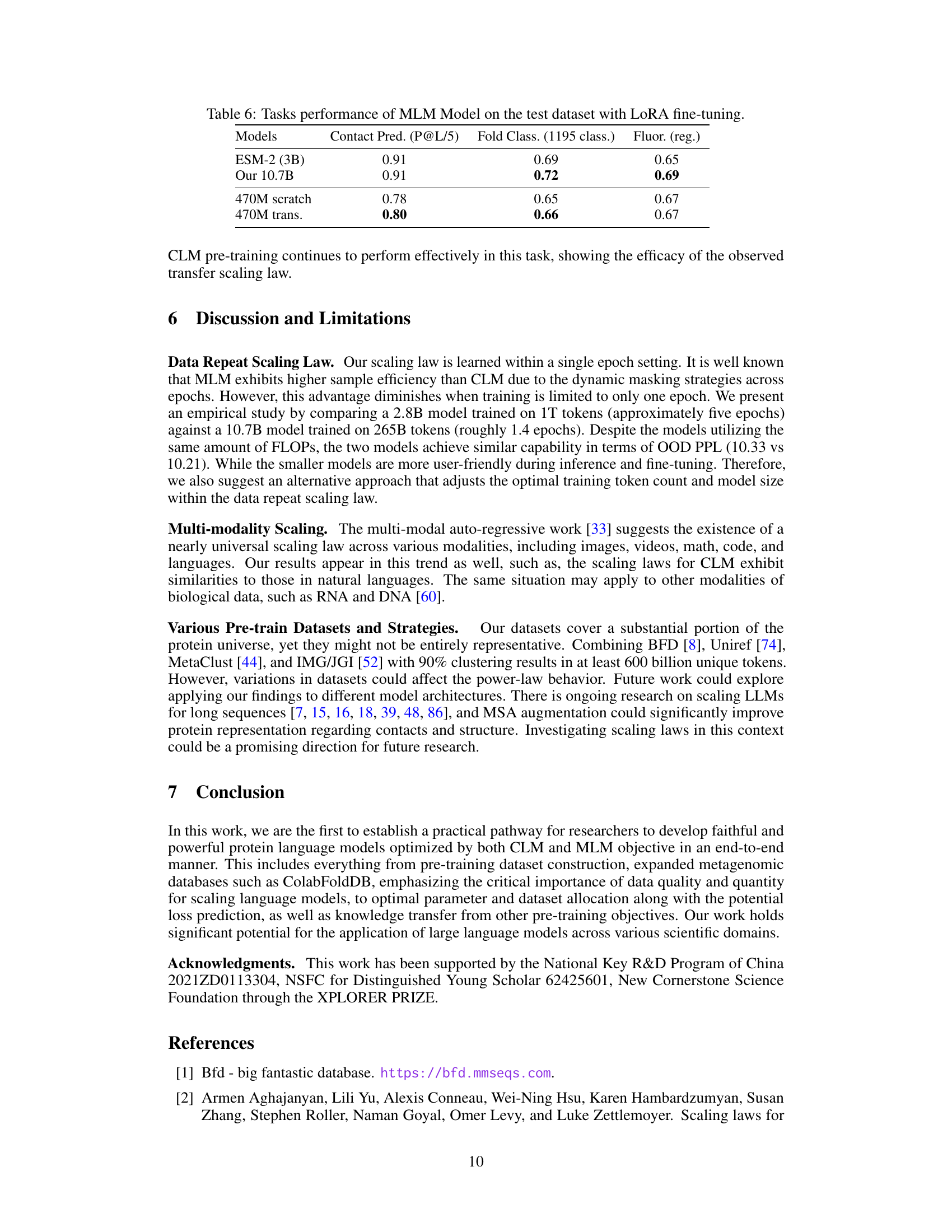

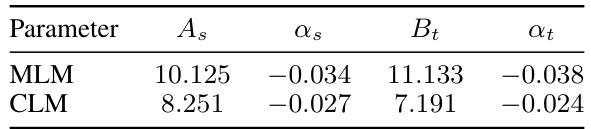

This figure compares the performance of the authors’ 7.2B CLM model against the PROGEN2-xlarge model using four different metrics: perplexity, pLDDT scores, Foldseek analysis, and sequence clustering. The results show that the 7.2B CLM model outperforms the PROGEN2-xlarge model in terms of perplexity, achieving lower values across different sequence identity levels (MaxID). It also demonstrates superior protein structure prediction (as measured by pLDDT), better similarity to natural protein sequences (according to Foldseek analysis), and greater sequence diversity (as indicated by the number of clusters at 50% sequence identity).

The figure shows the results of transfer learning experiments between Causal Language Models (CLM) and Masked Language Models (MLM). The left side demonstrates that transferring from MLM to CLM shows diminishing returns with increasing model size. In contrast, transferring from CLM to MLM shows increasing benefits as model size increases. The right side presents the loss curves for both CLM and MLM across a range of FLOPs. It shows the efficient frontiers for both from scratch training, as well as transfer learning approaches.

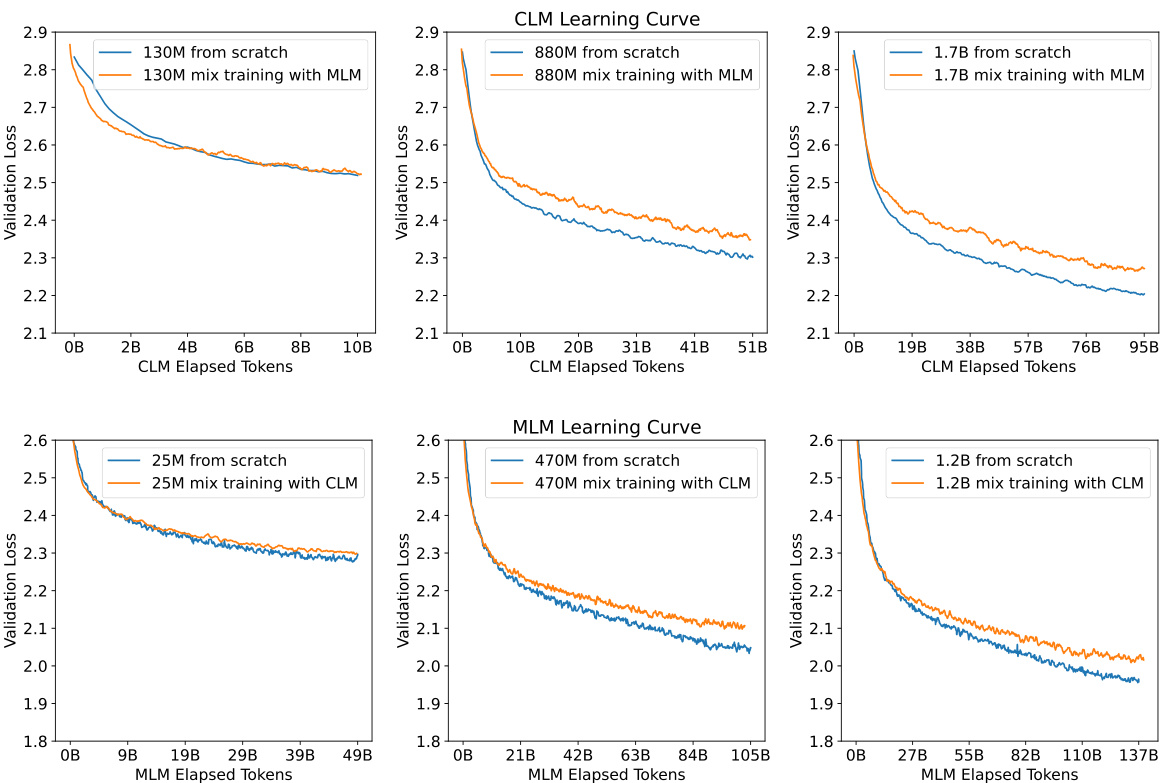

This figure compares the validation loss curves of models trained using two different approaches: training from scratch and mixed training (simultaneously optimizing for both CLM and MLM objectives). The results show that across all model sizes tested, training from scratch consistently yielded lower validation loss compared to the mixed training approach, suggesting that focusing on a single objective at a time during training is more effective than trying to optimize both simultaneously.

This figure shows the scaling laws for both Causal Language Model (CLM) and Masked Language Model (MLM) in protein language models. The top panels display the validation loss for CLM and MLM across various model sizes with a fixed FLOP count. The lowest loss points for each FLOP budget are highlighted. The bottom panels show the efficient frontier, illustrating the optimal model size and training token number as a function of FLOP budget. The efficient frontier helps to estimate the optimal resource allocation for training protein language models under different computational constraints.

This figure shows the scaling laws for Causal Language Models (CLM) and Masked Language Models (MLM) in protein language modeling. The top row presents plots showing the relationship between model size, training tokens, and validation loss for various FLOP (floating-point operations) budgets. The lowest loss for each FLOP budget indicates an optimal model size and data size. The bottom row shows the efficient frontier, which is a curve illustrating the optimal model size and training tokens for different FLOP budgets, enabling effective model scaling.

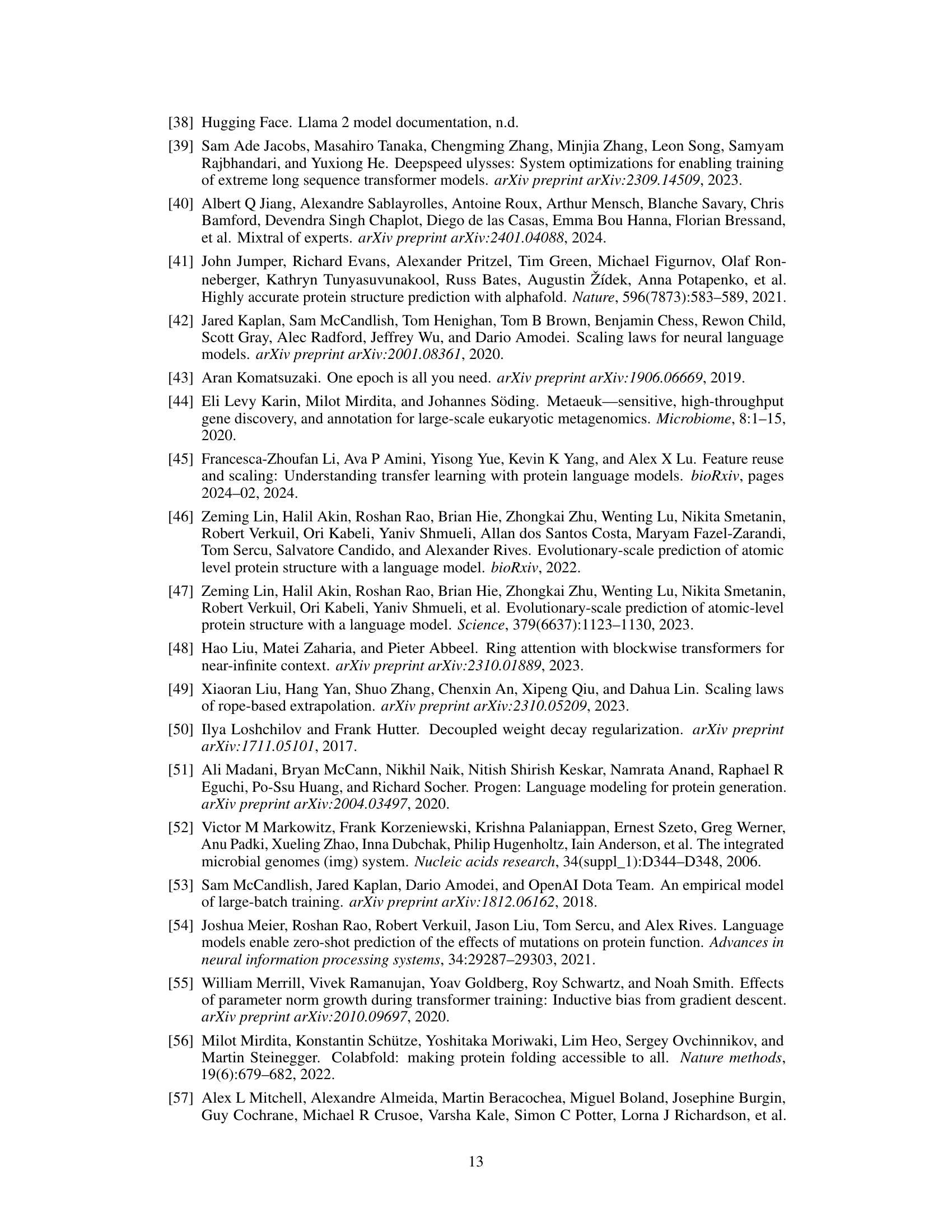

More on tables

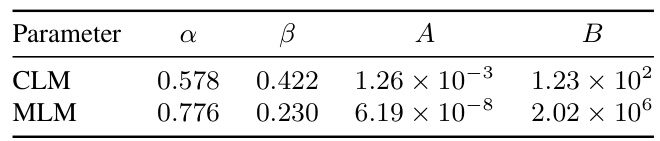

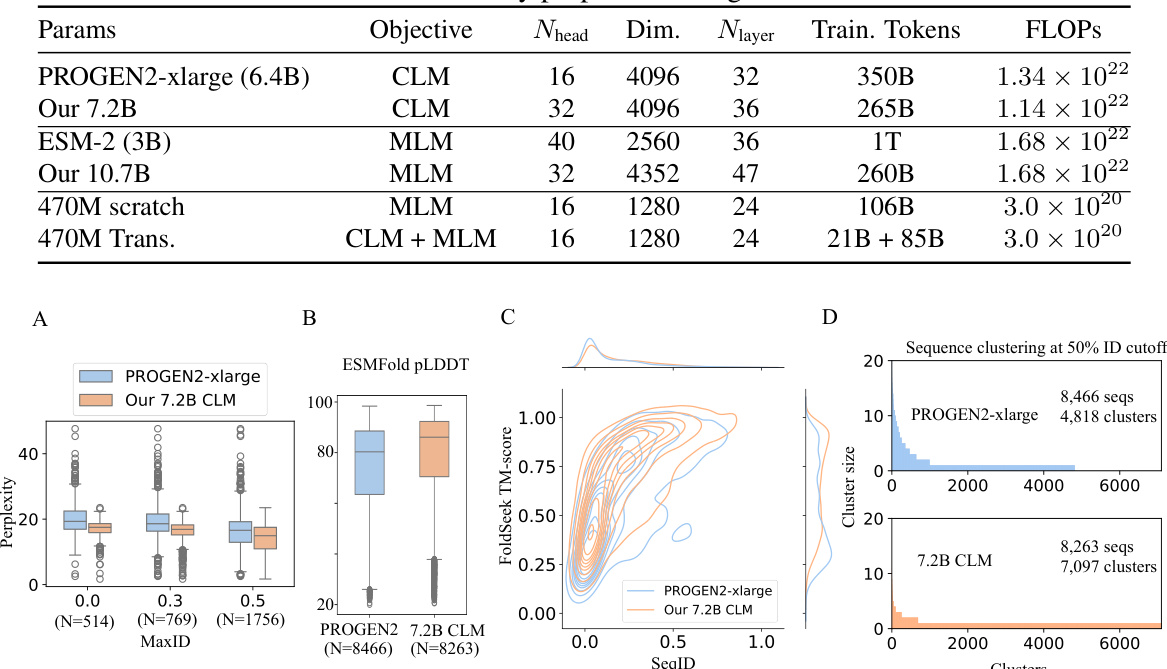

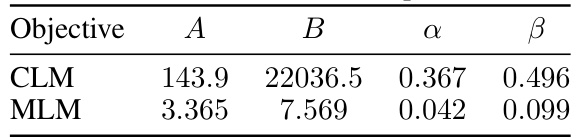

This table presents the coefficients obtained from fitting the power-law scaling equations for both Causal Language Model (CLM) and Masked Language Model (MLM). The parameters α and β represent the exponents of the power-laws describing the relationship between compute budget (C) and model size (N) and data size (D), respectively. A and B are scaling constants for the model size and data size equations. These coefficients show the different scaling behaviors of CLM and MLM in terms of the growth of model size and data size with respect to increasing compute budget.

This table presents the coefficients obtained from fitting the power-law relation defined in Equation 2, which describes the scaling relationship between loss (L(x)), model size (N), compute budget (C), and training dataset tokens (D). The table shows separate coefficients for CLM and MLM objectives.

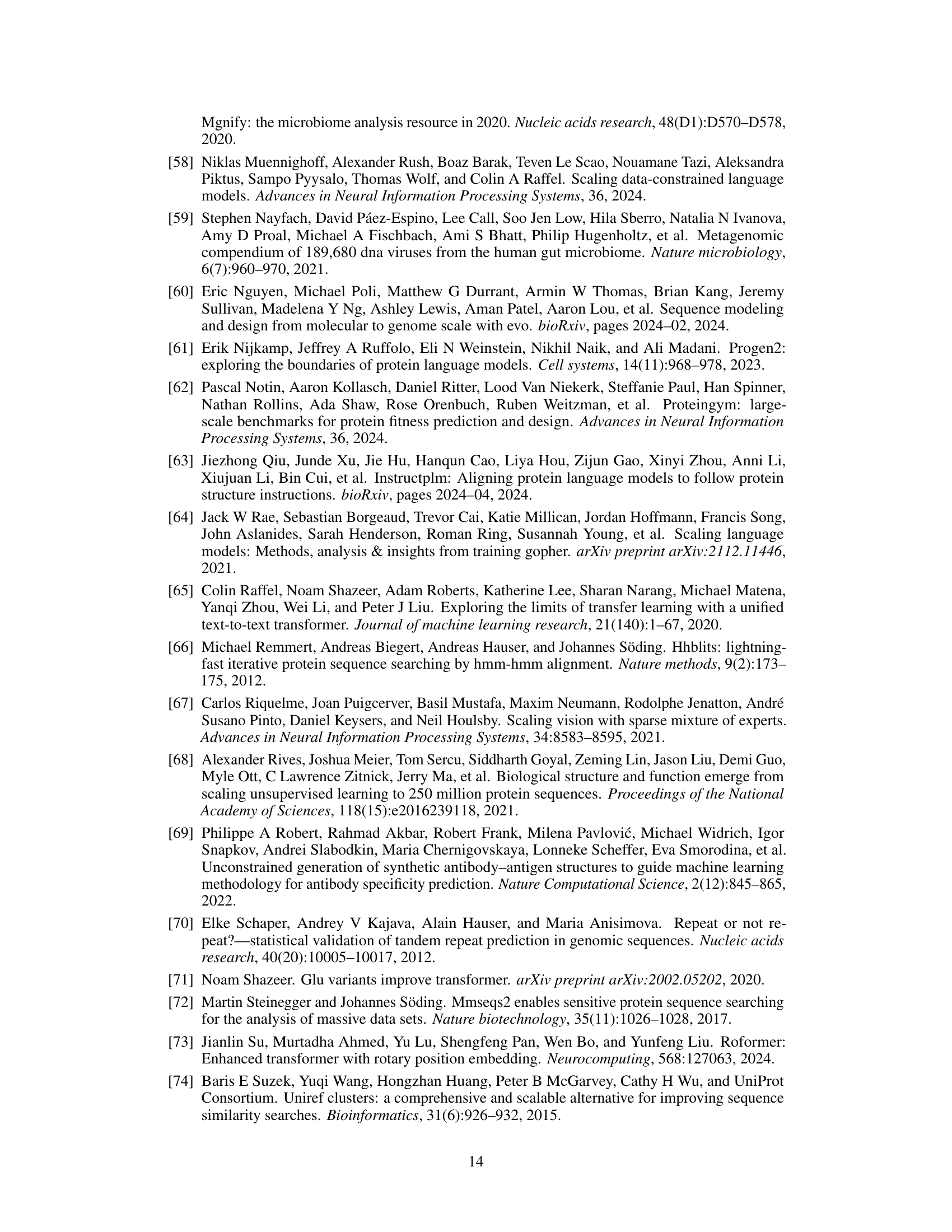

This table presents the coefficients obtained from fitting the power-law equations for the loss in transfer learning (L(Ct)) and training from scratch (L(Cs)) for both MLM and CLM objectives. The coefficients (As, αs, Bt, αt) are used in the equations L(Cs) = As × Cs^αs and L(Ct) = Bt × Ct^αt, which quantify how the loss changes with compute budget (C) for each objective. These coefficients help in understanding the relative effectiveness of training from scratch versus transfer learning for different model sizes and objectives.

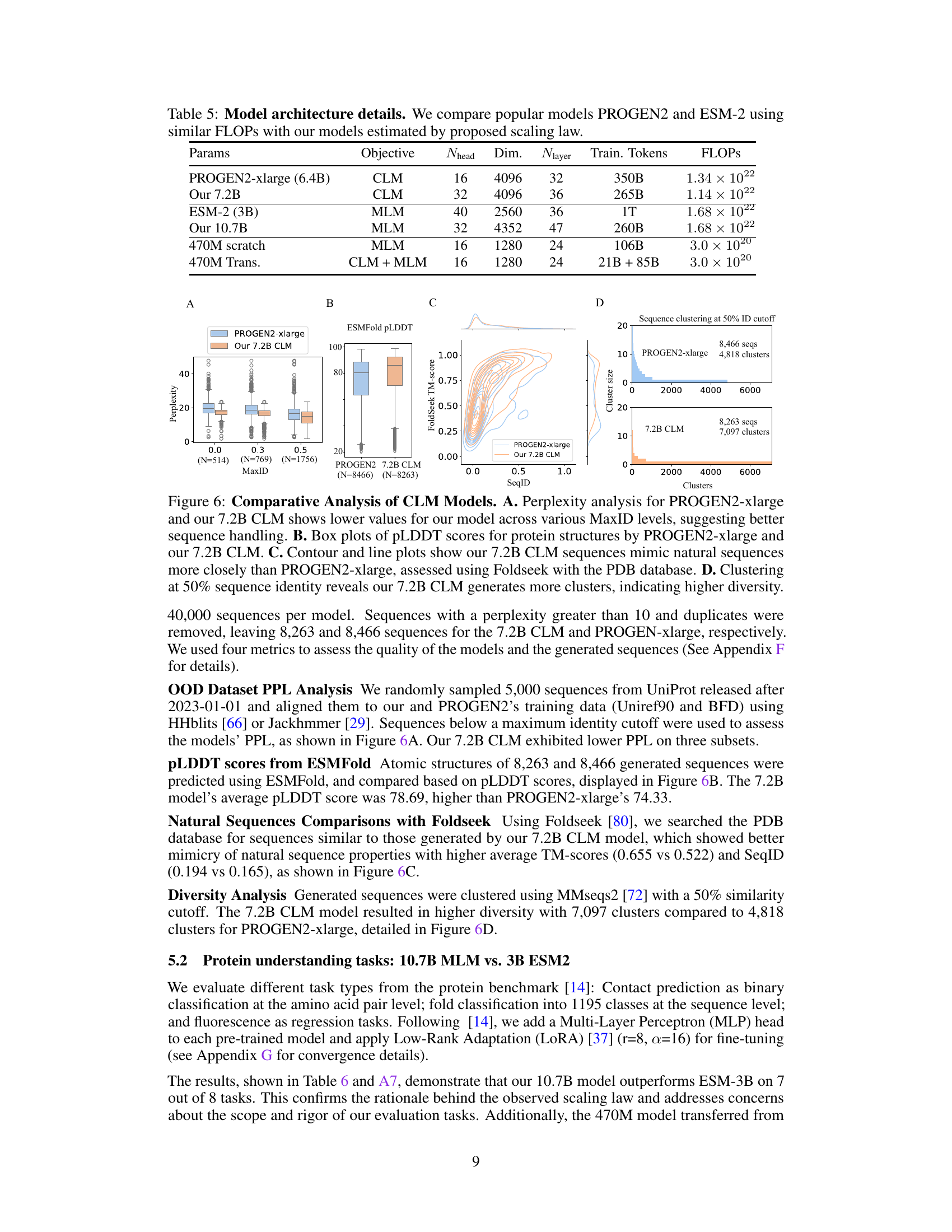

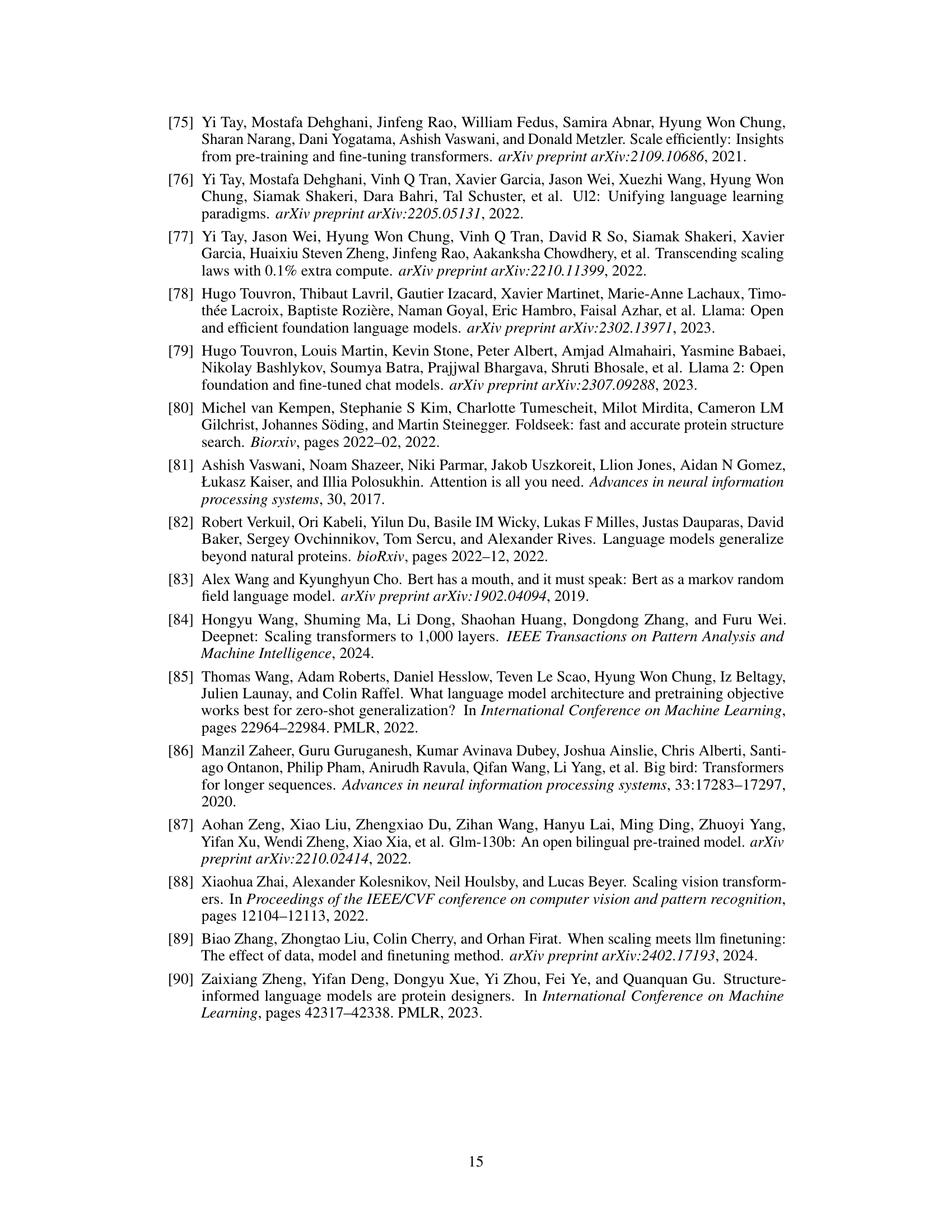

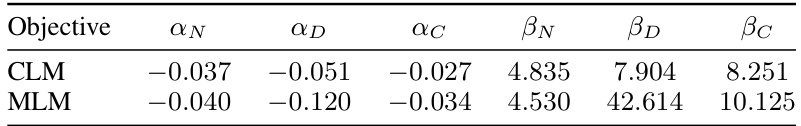

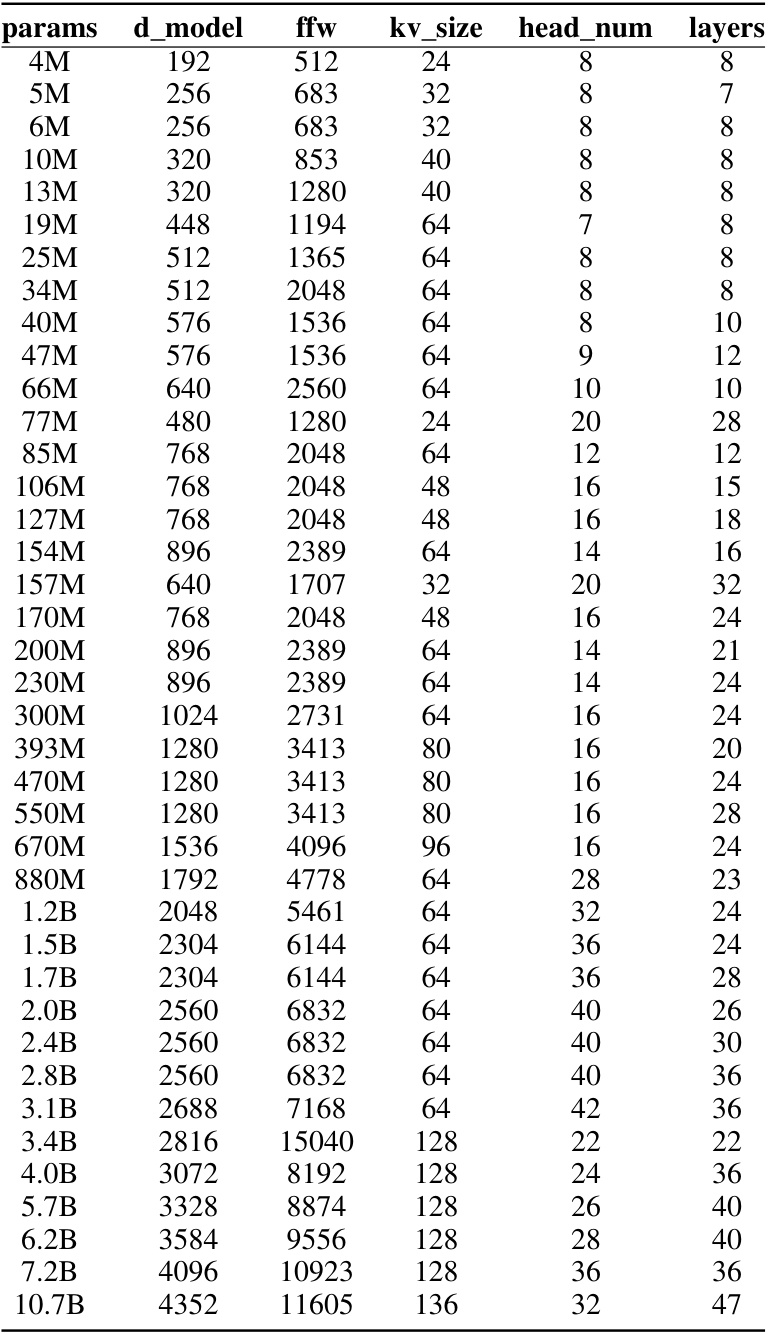

This table presents the architectural details of several protein language models, including PROGEN2-xlarge, ESM-2, and models developed by the authors. It compares models with similar FLOPs (floating point operations) to highlight the trade-offs between model size, training tokens, and computational efficiency achieved by the authors’ proposed scaling laws. The table lists the number of parameters, the objective function (CLM or MLM), the number of attention heads, the dimension of the hidden layer, the number of layers, the number of training tokens, and the total FLOPs for each model.

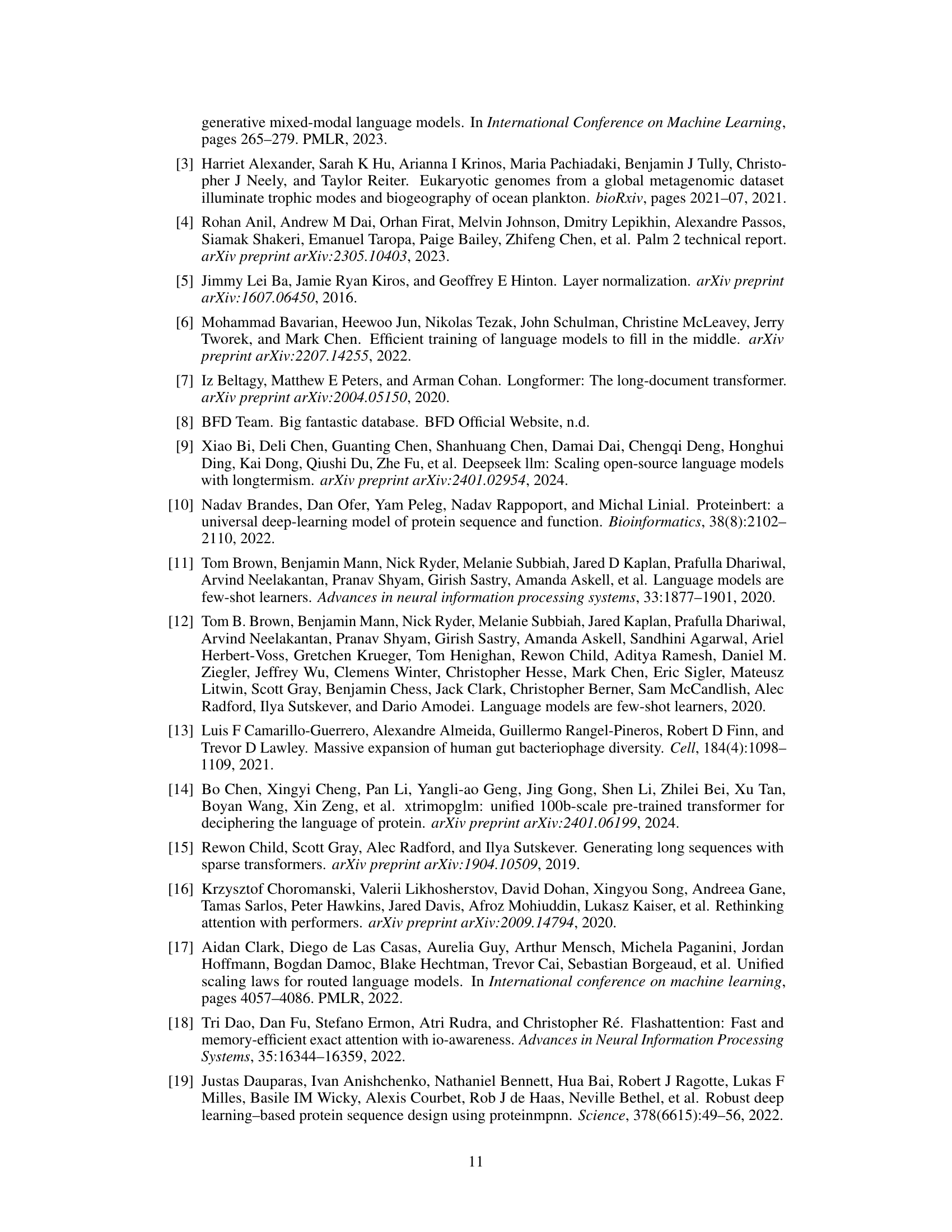

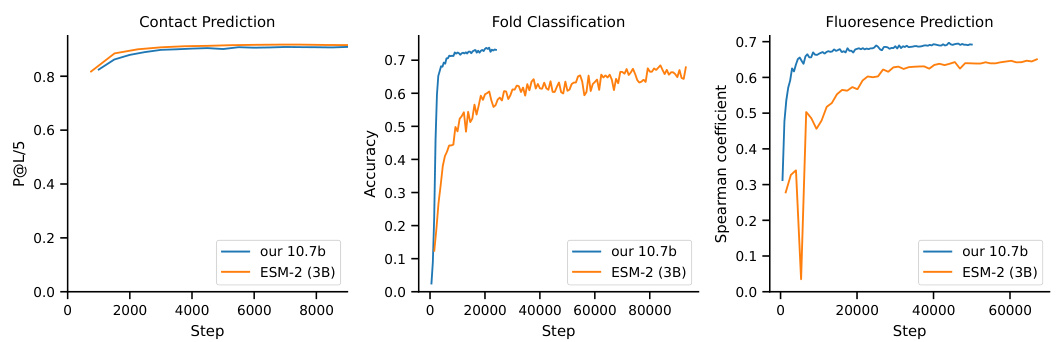

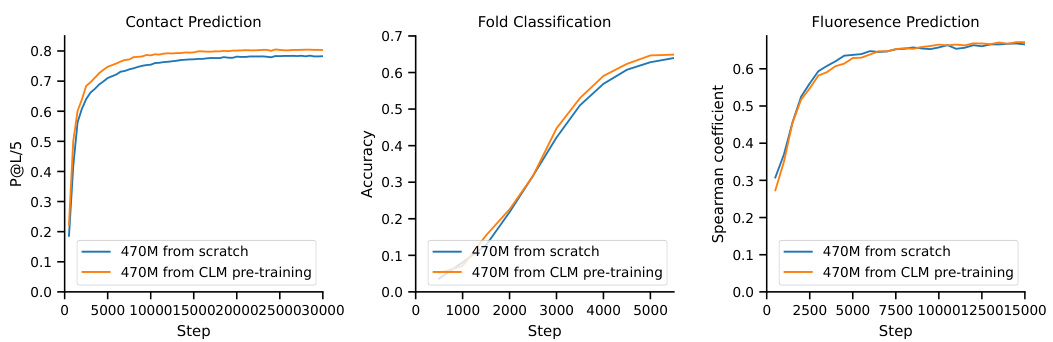

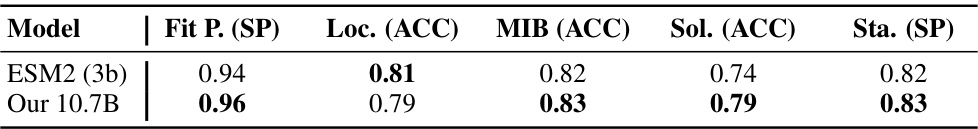

This table presents the performance of Masked Language Models (MLMs) on various downstream tasks after fine-tuning with Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA). It compares the performance of a 3B parameter ESM-2 model and a 10.7B parameter model trained using the methods described in the paper. It also includes results for smaller 470M parameter models, one trained from scratch and one using transfer learning from a pre-trained Causal Language Model (CLM), highlighting the impact of model size and transfer learning techniques on performance. The tasks evaluated include Contact Prediction, Fold Classification, and Fluorescence prediction.

This table presents the performance of the MLM model (both the 10.7B parameter model trained with the proposed scaling laws and a 3B parameter ESM-2 model) on various downstream tasks after fine-tuning with LoRA. The tasks include contact prediction (P@L/5), fold classification (1195 classes), and fluorescence (regression). The results show how the proposed method compares to a well-established model in protein language modeling.

This table provides a comparison of the architecture details for several protein language models, including PROGEN2-xlarge, ESM-2, and the models developed by the authors of the paper. The comparison is based on similar FLOPS (floating point operations) counts, which reflects computational costs. The table shows the number of parameters, the objective function used during training (CLM or MLM), the number of attention heads, the embedding dimension, the number of layers, the number of training tokens, and the total FLOPS. The authors’ models were sized based on the scaling laws developed and described in their paper. This comparison allows the reader to understand the relative sizes and computational costs of these various models.

This table presents the coefficients derived from fitting Equation 8, a combined power-law model, to the data for both CLM and MLM objectives. The equation aims to capture the relationship between model size (N), training data size (D), and loss (L). Coefficients A, B, α, and β represent parameters in the power-law model, providing insights into the scaling behavior of protein language models with different objectives. The table quantifies the relative contributions of model size and data size to the overall loss, which is crucial for optimizing the training process given limited computational resources.

This table presents the architecture details of various protein language models, including the number of parameters, hidden dimension, number of layers, number of attention heads, and FLOPs. It compares the popular models PROGEN2 and ESM-2 with the models proposed in the paper. The FLOPs of the proposed models are estimated based on the scaling laws proposed in the paper.

Full paper#