↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) struggle with processing long texts due to their limited context window. This constraint leads to significant performance degradation when dealing with text exceeding the window length. Existing solutions primarily focus on modifying positional encodings or attention scores, but lack in-depth understanding of the underlying mechanisms.

This research explores the positional information within and beyond the context window to analyze LLMs’ mechanisms. By decomposing positional vectors from hidden states, the researchers analyzed their formation, effects on attention, and behavior when texts exceed the context window. Based on their findings, they devised two training-free methods: positional vector replacement and attention window extension, demonstrating significant improvements in handling longer texts.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it uncovers the hidden role of positional information in LLMs and provides training-free methods to effectively extend context windows. It offers new insights into LLM mechanisms and opens avenues for improving their performance on long texts, which is a major challenge in the field. This is highly relevant to current research trends focusing on context window extension and LLM scalability.

Visual Insights#

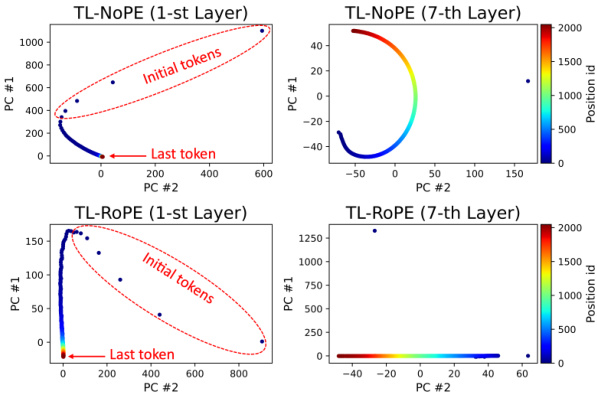

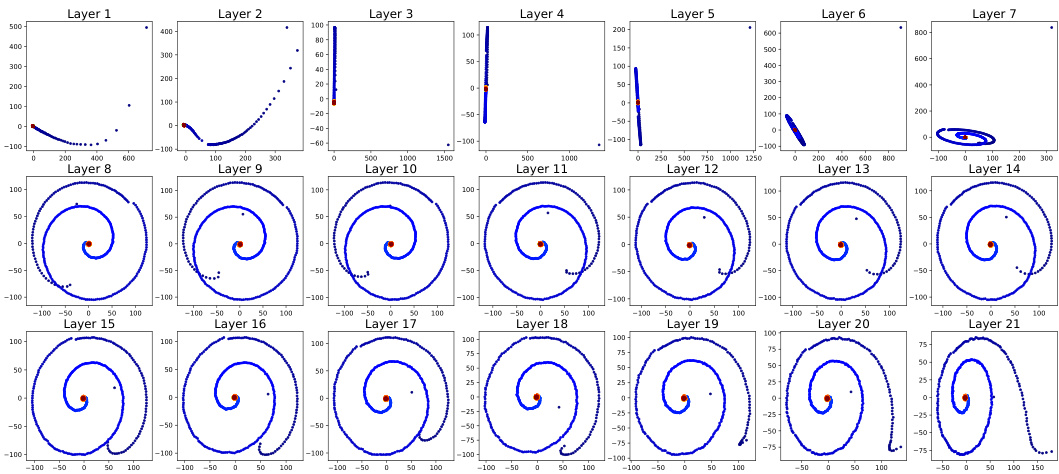

This figure uses principal component analysis (PCA) to visualize the positional vectors extracted from the first and seventh layers of two Transformer models: one without positional encodings (TL-NoPE) and one with rotary position embeddings (TL-ROPE). The plots show how positional information is distributed across different positions in the sequence. In the first layer, initial tokens show distinctly different positional vectors, while later tokens have similar vectors. This highlights the role of the initial tokens in establishing positional information within the sequence. By the seventh layer, the positional vectors become more evenly distributed across all positions, indicating that the network has learned to represent positional information more comprehensively.

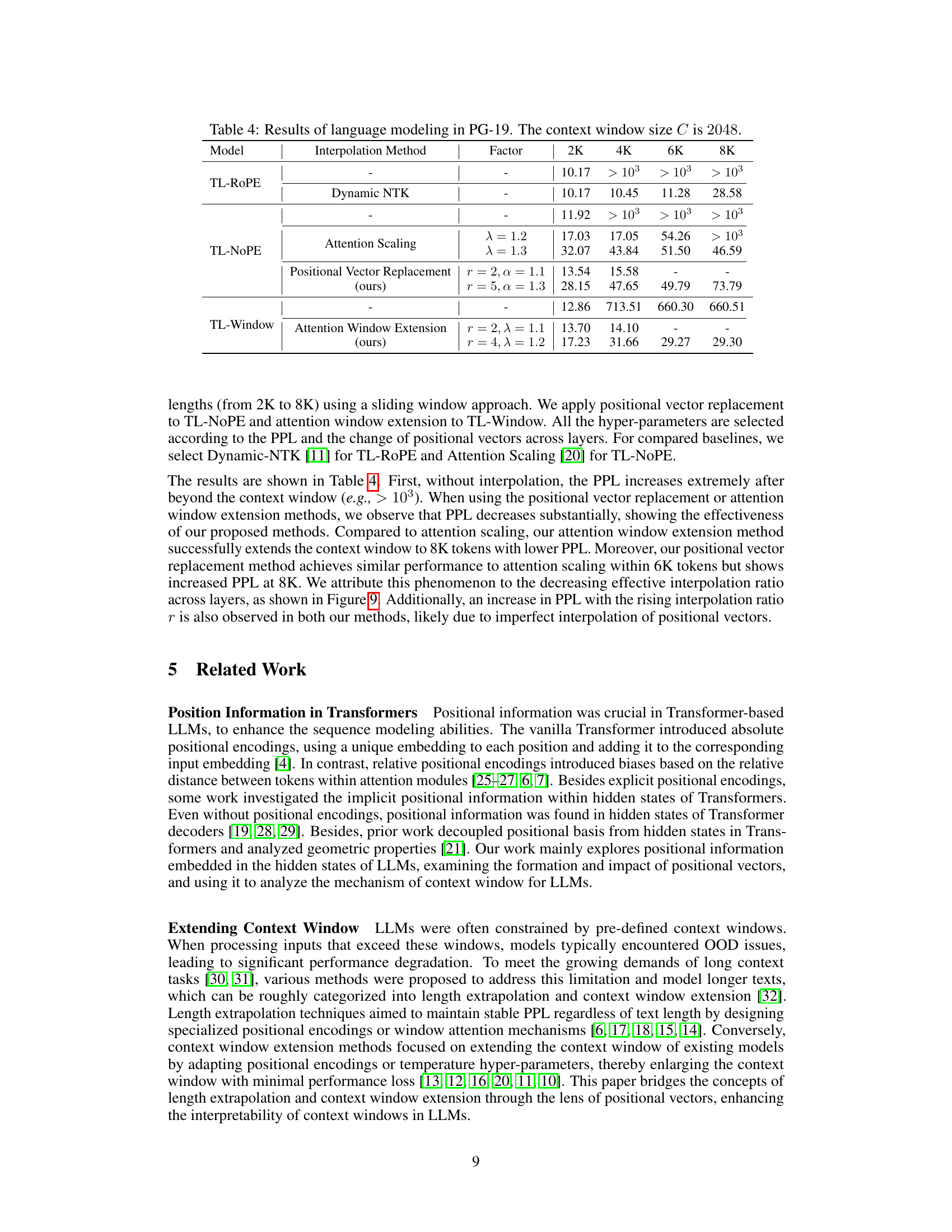

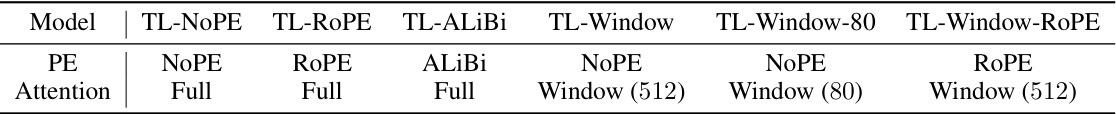

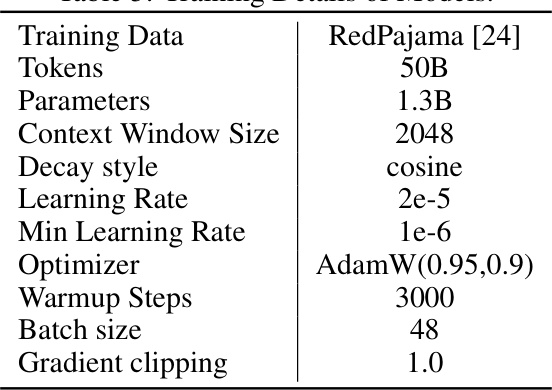

This table presents the different model variants used in the experiments. Each model is based on the TinyLlama architecture and varies in its positional encoding (PE) method and attention mechanism. Models are categorized by whether they employ no positional encoding (NoPE), Rotary Positional Embeddings (RoPE), or the ALiBi method. Attention mechanisms are either full attention (where each token attends to all others) or window attention with a specified window size (e.g., 512 or 80 tokens).

In-depth insights#

Positional Vector Role#

The concept of “Positional Vector Role” in LLMs centers on how positional information, encoded within positional vectors, influences model behavior. Positional vectors are crucial for capturing the sequential nature of text, distinguishing between tokens at different positions within a sequence. The paper’s analysis likely reveals how these vectors shape attention mechanisms, influencing which tokens interact most strongly during processing. This impact is particularly important at the boundaries of the context window, where out-of-distribution positional information can lead to performance degradation. The role extends to understanding length extrapolation and context window extension techniques, as modifications to positional vectors—whether through interpolation or other methods—directly affect the model’s ability to process longer sequences. The study likely shows how the initial tokens in a sequence play a key anchoring role, establishing a positional basis that shapes the vectors for subsequent tokens, and highlights the importance of maintaining consistent positional vector distributions both inside and beyond the context window for better performance. This suggests that the effective management of positional information is paramount in overcoming the limitations of context window size in LLMs.

Context Window Extension#

The concept of ‘Context Window Extension’ in large language models (LLMs) addresses the limitation of processing only a fixed-length input sequence. Expanding this window is crucial for handling longer texts and improving performance on tasks requiring extensive contextual understanding. Current approaches often involve manipulating positional encodings or attention mechanisms. Methods like positional vector replacement and attention window extension offer training-free solutions, aiming to improve upon existing techniques. These methods focus on altering how the model handles positional information, either by directly replacing out-of-distribution positional vectors or modifying the attention mechanisms. The effectiveness of these strategies depends on maintaining the consistency of positional information throughout the input sequence, avoiding a disruption in attention patterns and thereby preserving performance. However, challenges remain in achieving optimal interpolation of positional vectors, especially when significantly expanding the context window. Further research is needed to fully understand the impact of these techniques on different LLM architectures and to explore more robust and efficient solutions for context window extension.

LLM Mechanism#

Large language models (LLMs) function through a complex interplay of mechanisms, not fully understood. Transformer architecture underpins many LLMs, utilizing self-attention to weigh the importance of different words in a sequence. Positional encoding is crucial for LLMs to understand word order, with various methods like absolute or relative positional embeddings used. However, the limited context window is a significant constraint; models struggle with long sequences exceeding this limit. Recent research focuses on extending this window, often by manipulating positional embeddings or attention mechanisms. Hidden states within the model represent contextual information and evolve across layers; their analysis helps reveal how positional information propagates and impacts attention weights. Decomposing hidden states into semantic and positional vectors aids in understanding the formation and role of positional information. Training-free methods that leverage these insights offer promising ways to extend context windows without retraining the entire model. Further research will continue exploring these mechanisms, improving LLM performance and understanding their capabilities and limitations.

Training-Free Methods#

Training-free methods for extending context windows in large language models (LLMs) offer a compelling alternative to traditional fine-tuning approaches. They avoid the computational cost and potential instability associated with retraining, making them attractive for practical applications. The core idea revolves around manipulating positional information within the LLM without altering its underlying weights. This might involve modifying positional encodings, adjusting attention mechanisms, or interpolating positional vectors from existing representations. While these methods offer significant advantages in terms of efficiency, their effectiveness can be limited by the inherent constraints of the original model architecture. The ability to successfully extrapolate or interpolate positional information without retraining depends heavily on the sophistication of the model’s architecture and the specific techniques employed. Therefore, while promising, training-free methods may not always achieve the same level of performance improvement as fine-tuning; their value lies in their speed, convenience and ease of deployment.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on extending context windows in large language models (LLMs) could fruitfully explore several avenues. Scaling experiments to larger, more diverse LLMs is crucial to validate the generalizability of the findings beyond the specific models used in the study. Further investigation into the interaction between positional information and other types of encoding (e.g., relative position encodings or attention mechanisms) would provide deeper insight into the mechanisms governing context window limitations. A particularly promising avenue would be to investigate methods for more effective interpolation of positional vectors in training-free methods, as imperfect interpolation appears to hinder performance with larger contexts. Finally, research exploring potential applications of the discovered positional vector properties to other areas of LLM research, such as transfer learning or model compression, could unlock further valuable insights.

More visual insights#

More on figures

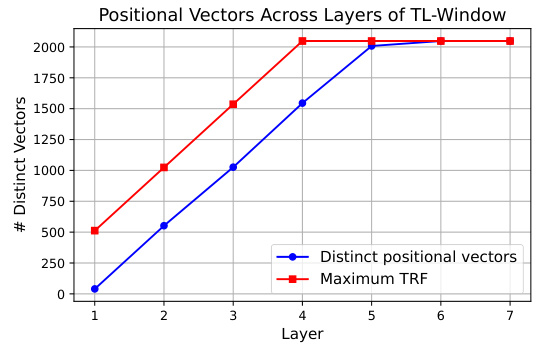

This figure compares the number of distinct positional vectors observed in a Transformer model with windowed attention against the theoretical receptive field (TRF). The TRF represents the maximum number of tokens a single token can theoretically attend to given the window size and number of layers. The plot shows that while the TRF grows linearly with the layer number, the number of distinct positional vectors also increases but more gradually. This suggests that even though the theoretical receptive field allows for larger context, the model does not fully utilize that capacity to capture distinct positional information at every layer. The difference likely reflects the effect of the attention mechanism’s ability to focus the attention on relevant tokens across layers, leading to a less than maximal use of the theoretically available receptive field.

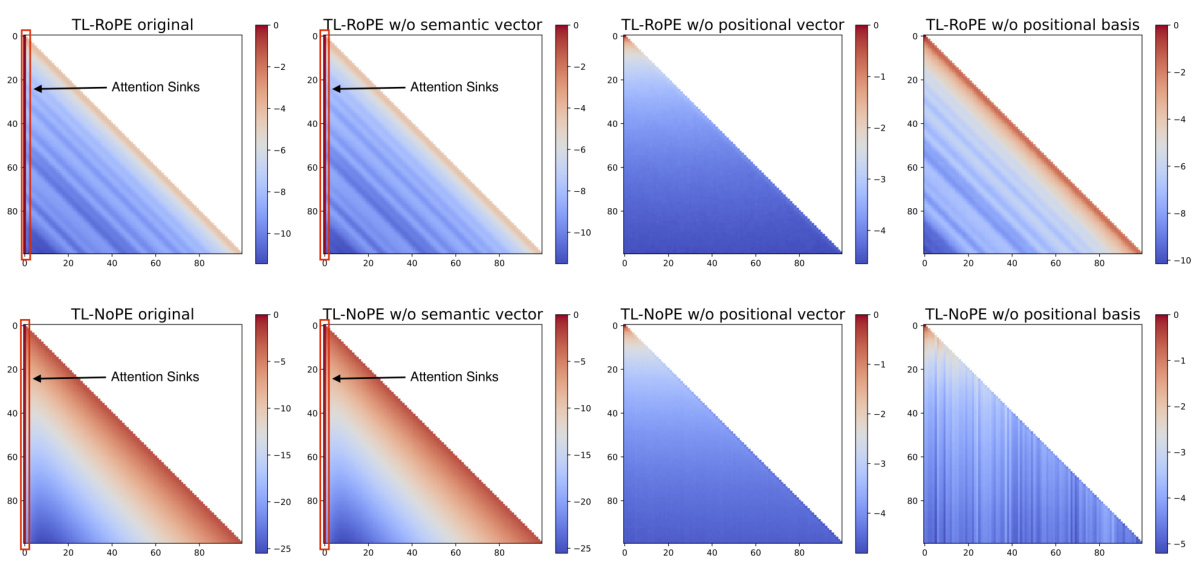

This figure visualizes the logarithmic attention maps for TL-ROPE and TL-NOPE models. It shows the attention weights across different positions for different scenarios: the original models and variants where semantic vectors, positional vectors, or positional bases have been removed. The heatmaps illustrate the impact of these different components on the overall attention distribution, particularly highlighting the formation of attention sinks and long-term decay properties. By comparing the original models to the modified versions, the figure demonstrates the critical role positional vectors and bases play in modulating attention scores and shaping the characteristic long-term decay patterns in LLMs.

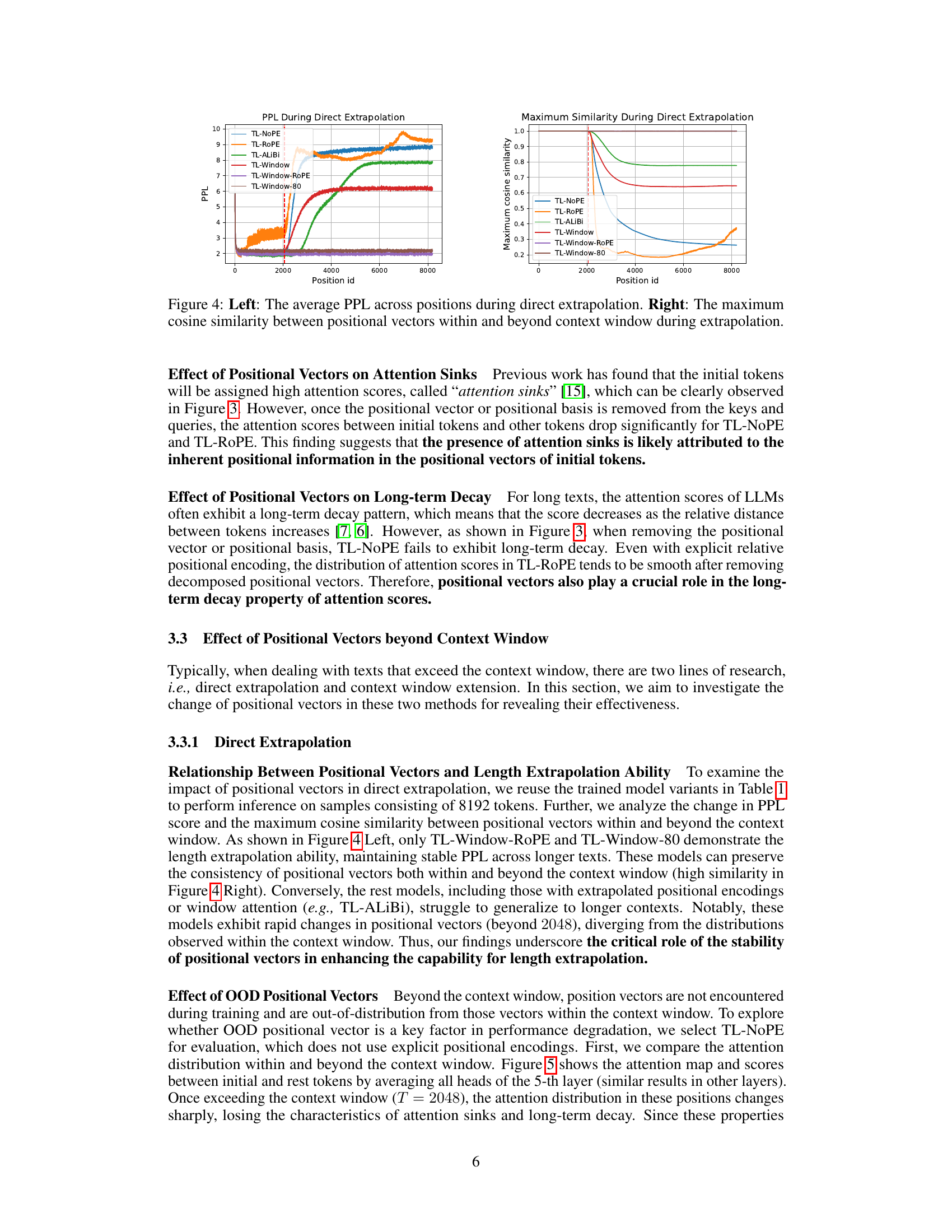

This figure shows the results of direct extrapolation experiments. The left panel displays the average perplexity (PPL) across different positions in sequences that exceed the context window. The right panel shows the maximum cosine similarity between positional vectors within and beyond the context window. The figure demonstrates that models with stable PPL scores also maintain high cosine similarity between positional vectors, both inside and outside the context window, highlighting the importance of positional vector consistency for successful length extrapolation.

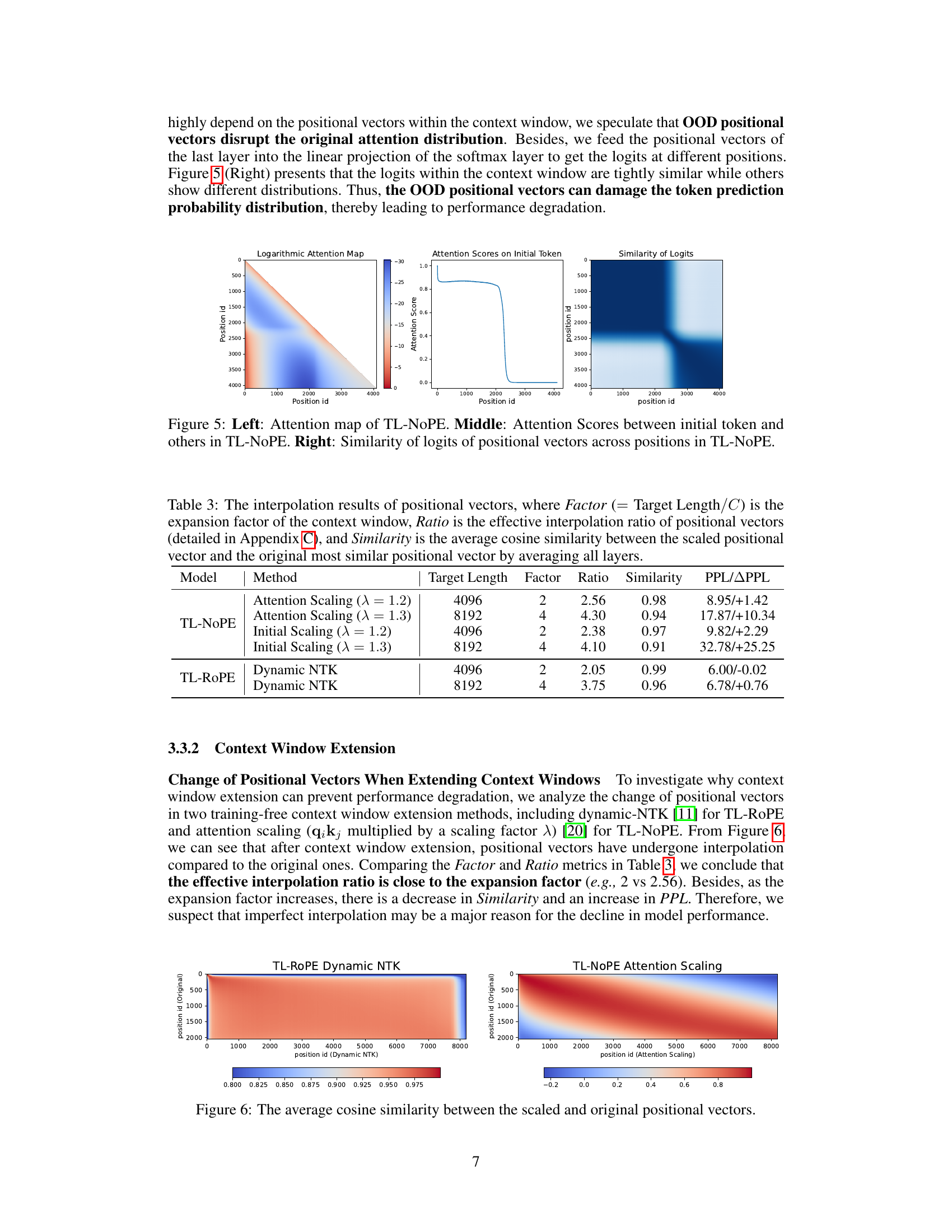

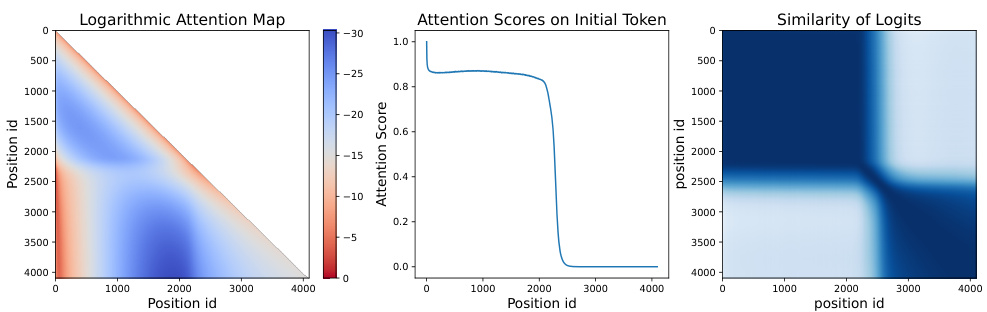

This figure visualizes the attention mechanism and the impact of out-of-distribution (OOD) positional vectors in a decoder-only Transformer without positional encodings (TL-NoPE). The left panel shows the logarithmic attention map, illustrating the distribution of attention weights across different token positions. The middle panel plots the attention scores specifically on the initial token, highlighting its role as an ‘attention sink’. The right panel displays the similarity of logits (output of the linear projection layer) across different positions, indicating the impact of OOD positional vectors on the model’s prediction probability distribution.

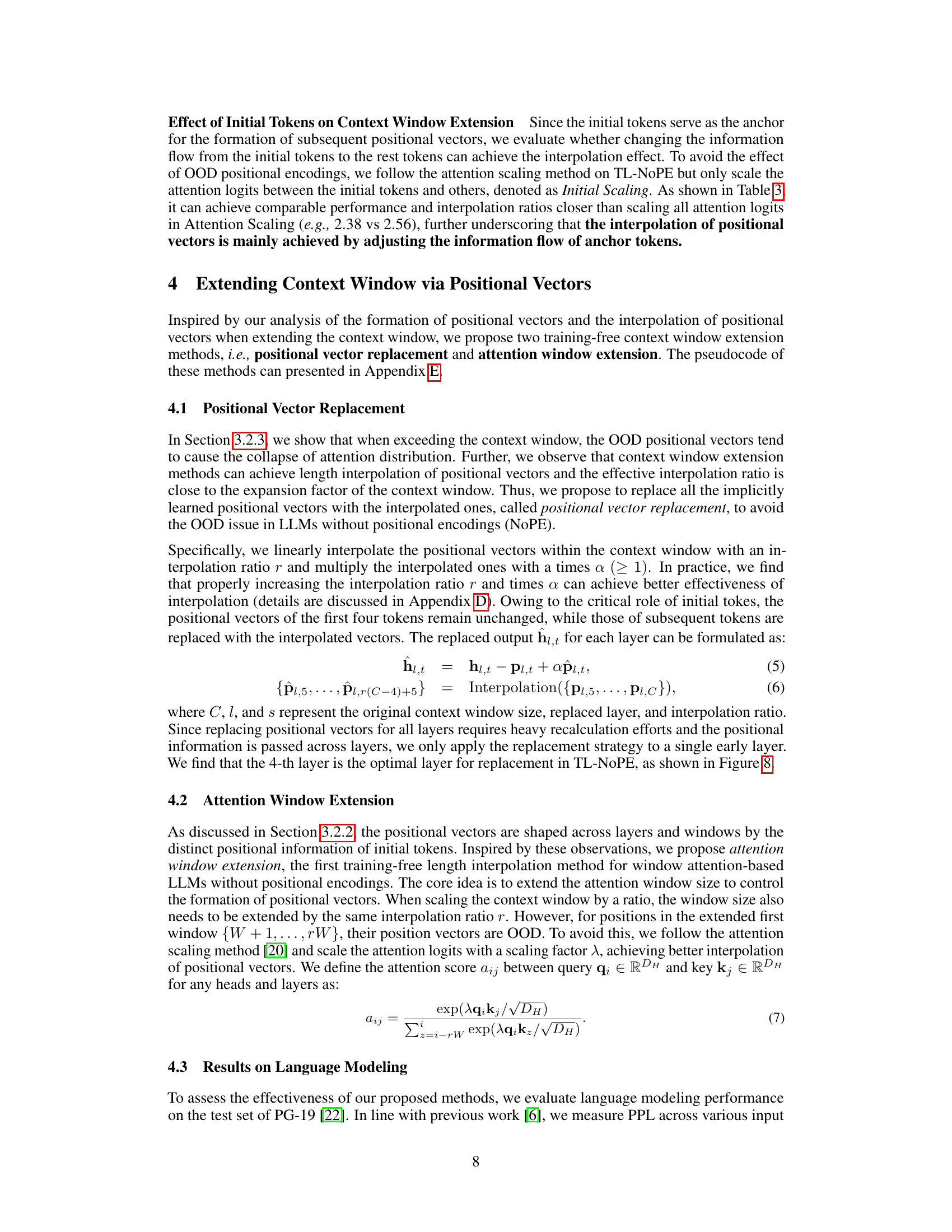

This figure displays two heatmaps visualizing the average cosine similarity between positional vectors before and after applying two different context window extension methods. The left heatmap shows the results for TL-ROPE with Dynamic NTK, and the right heatmap shows the results for TL-NoPE with Attention Scaling. Each heatmap compares the original positional vectors (y-axis) with the scaled positional vectors (x-axis) produced by the respective method. The color intensity represents the cosine similarity, with warmer colors indicating higher similarity and cooler colors indicating lower similarity. This figure helps in understanding the effectiveness of the context window extension methods by showing how well the new positional vectors generated by interpolation approximate the original ones.

The figure shows two line graphs, one for Transformers with NoPE and one for Transformers with RoPE. The y-axis represents the ‘First element of each hidden state after attention’, indicating the value of the first element of the hidden state vector after the attention mechanism has been applied. The x-axis represents the ‘position id’, which corresponds to the position of the token within the input sequence. Both graphs show a similar trend: the first element’s value increases rapidly at the beginning of the sequence and then plateaus. This demonstrates that the initial tokens in a sequence have a greater effect on the attention mechanism, as they are assigned greater attention weights, particularly evident in the NoPE model. This difference is likely due to the way positional information is handled in the models, with ROPE using rotary positional embeddings that might mitigate this initial token bias.

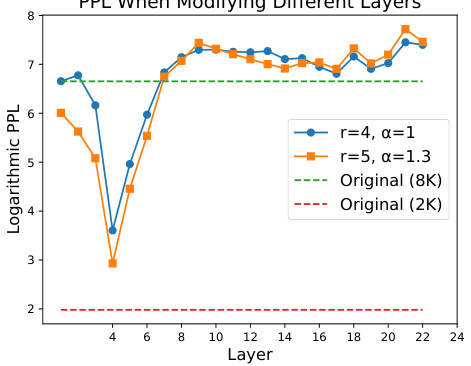

This figure shows the performance (logarithmic PPL score) of the positional vector replacement strategy applied at different layers of the TL-NoPE model. Two different interpolation ratios and expansion factors, (r=4, α=1) and (r=5, α=1.3), were used. The results show that replacing positional vectors in the 4th layer results in the lowest PPL, indicating this is the optimal layer for this operation. The graph also includes baselines representing the original performance with 2K and 8K tokens.

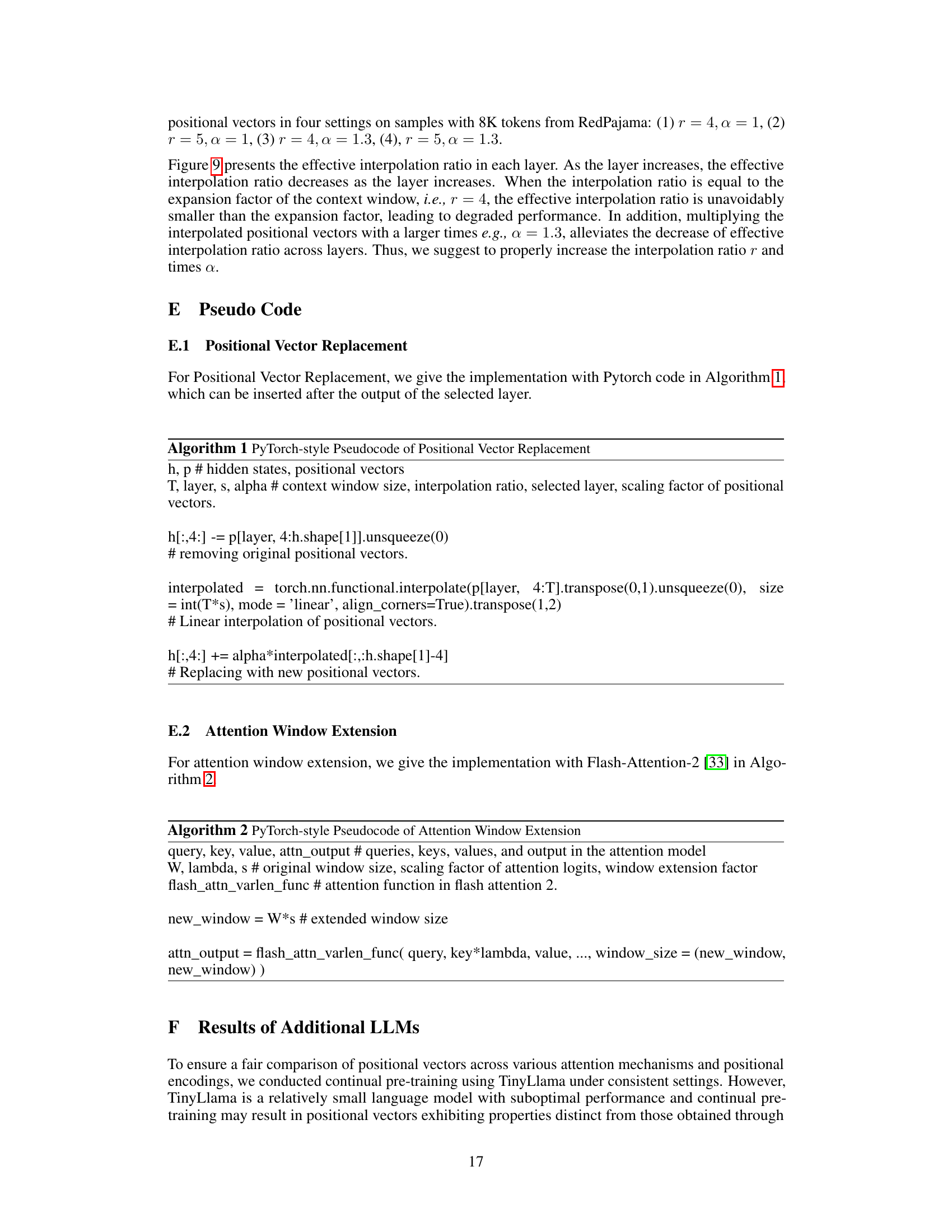

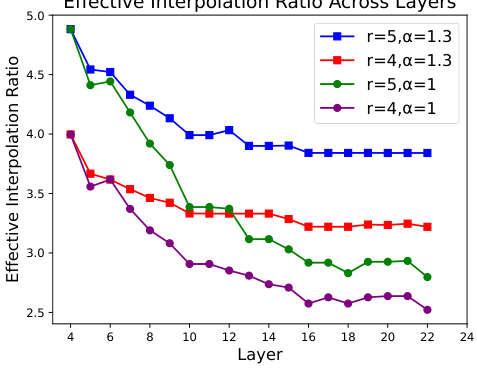

This figure shows how the effective interpolation ratio of positional vectors changes across different layers in a Transformer model. The effective interpolation ratio is a measure of how well the positional vectors are interpolated when extending the context window. The graph plots this ratio against the layer number for four different settings, each characterized by different interpolation ratios (r) and scaling factors (α). The figure demonstrates that as the layer number increases, the effective interpolation ratio decreases. This decline is mitigated when the scaling factor (α) is increased, suggesting that a higher scaling factor improves the quality of interpolation.

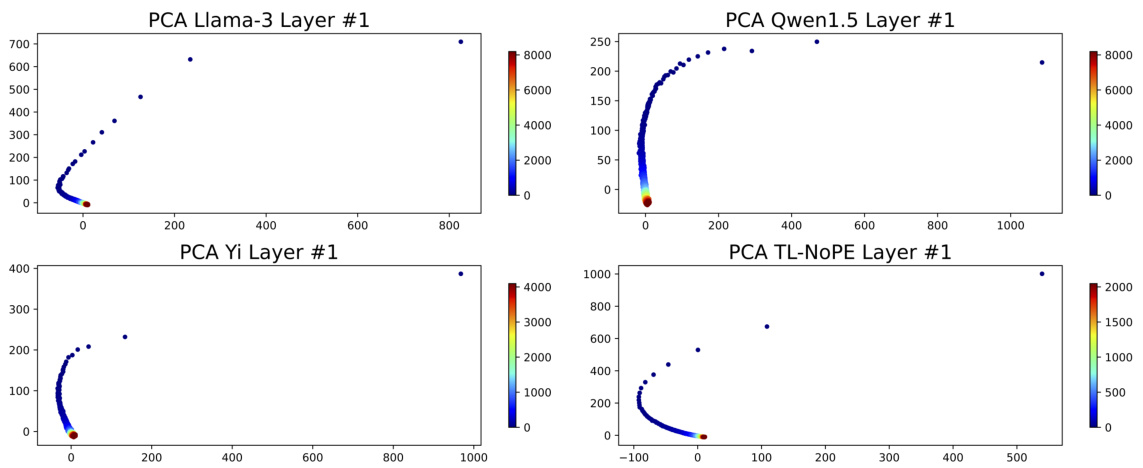

This figure shows the results of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) applied to the positional vectors extracted from the first layer of four different large language models (LLMs): Llama-3-8B, Qwen1.5-7B, Yi-9B, and a newly trained model TL-NoPE. The PCA reduces the dimensionality of the positional vectors, allowing for visualization in a 2D space. The plot helps to illustrate how the positional information is represented differently across these various models in the initial layer of the Transformer architecture.

This figure uses principal component analysis (PCA) to visualize the positional vectors extracted from the hidden states of a Transformer model. The left column shows the positional vectors from the first layer, while the right column displays those from the seventh layer. The visualization helps to understand how positional information is represented and evolves across different layers of the model, showing a clear shift from less distinct positional vectors in the first layer to more distinct vectors in the deeper layer.

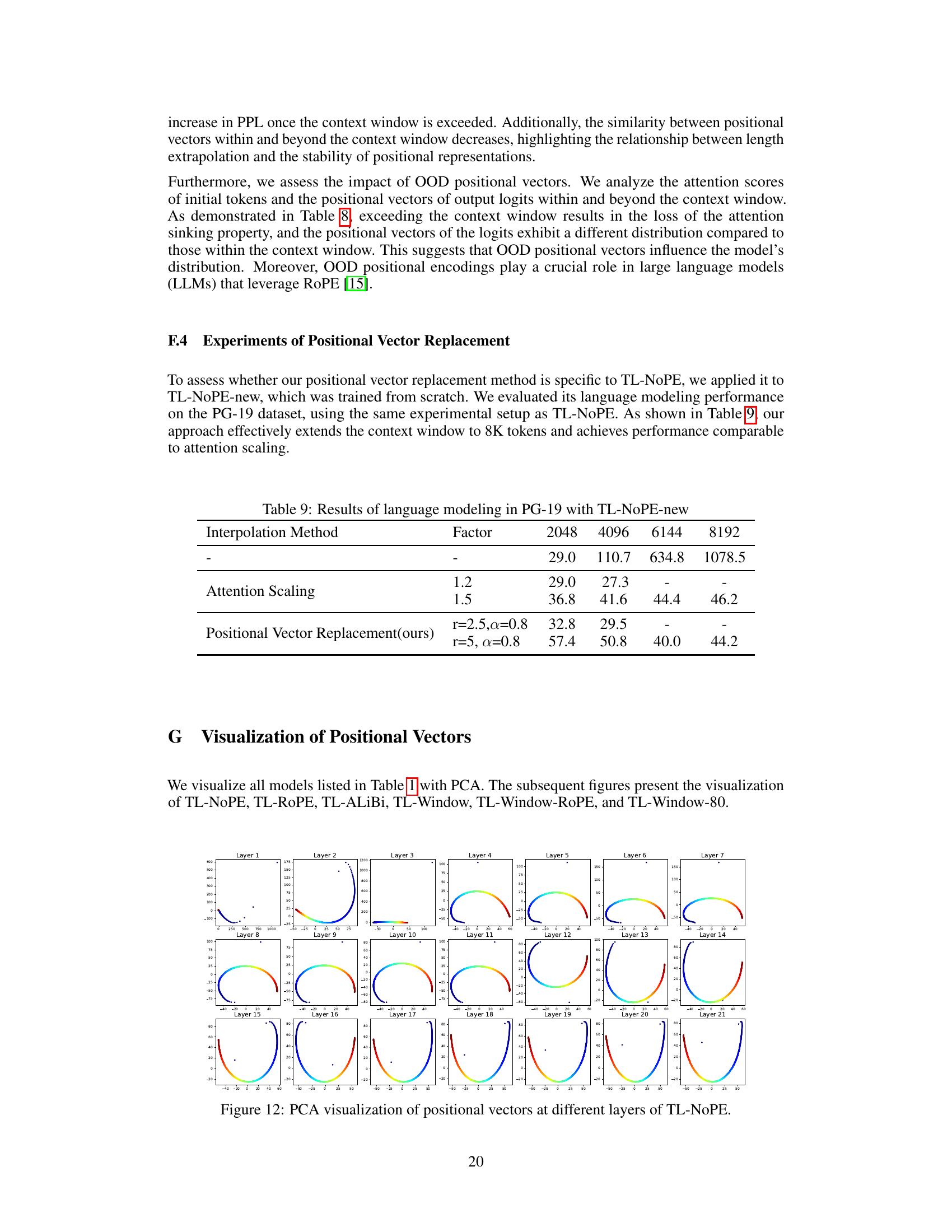

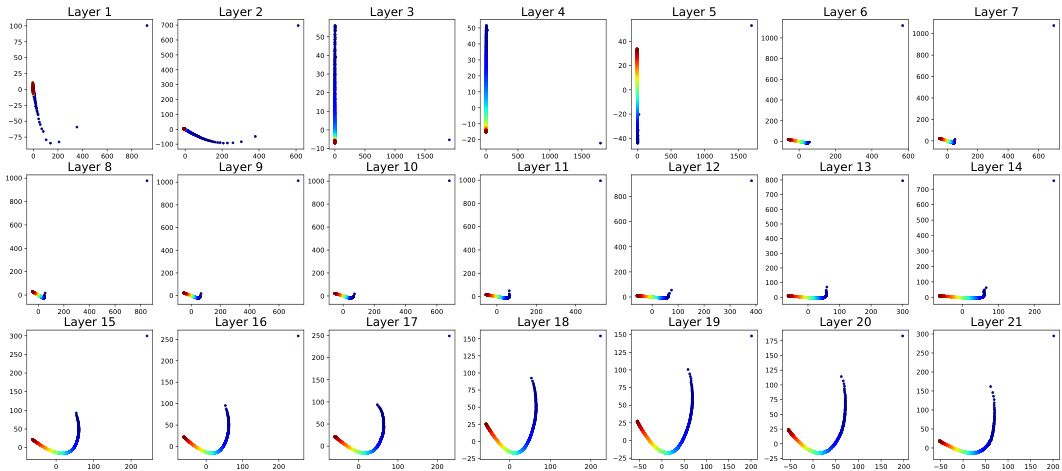

This figure shows the results of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) applied to positional vectors extracted from different layers (1-21) of the TL-NoPE model. Each subplot represents a different layer, visualizing the distribution of the positional vectors in a 2D space. The color coding likely indicates the position of the token within the sequence. The patterns reveal how the positional information evolves as the model processes the input sequence through its multiple layers. The initial layers might show a more scattered or less structured pattern, while deeper layers often exhibit a more organized and distinct representation of positional information.

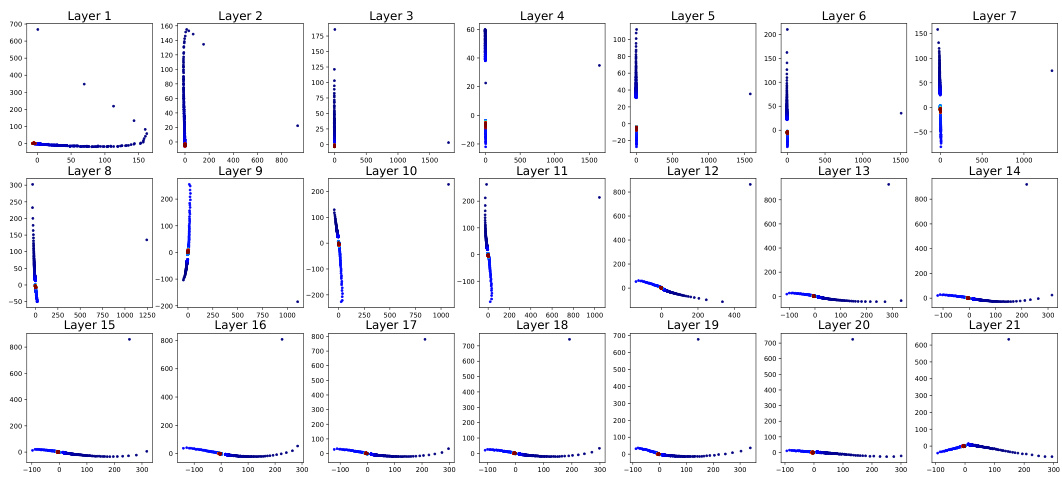

This figure shows the results of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) applied to positional vectors extracted from the first and seventh layers of a Transformer model. The left column displays the PCA for the first layer, and the right column displays the PCA for the seventh layer. Each plot shows how positional information is distributed across different positions within a sequence. In the first layer, initial tokens (the first few tokens in a sequence) exhibit significantly distinct positional vectors. By layer seven, the positional vectors of all tokens are evenly distributed, indicating a more sophisticated encoding of positional information across the sequence. The difference highlights how positional information evolves as the information passes through more layers of the Transformer model.

This figure visualizes positional vectors obtained through Principal Component Analysis (PCA) from the first and seventh layers of a Transformer model. The left column shows the PCA results for the first layer, illustrating how initial tokens have significantly distinct positional vectors, while subsequent tokens exhibit similar vectors. The right column displays the PCA results for the seventh layer, demonstrating that after several layers, positional vectors become more evenly distributed across all positions. This visual representation helps to understand the formation and distribution of positional information within a Transformer model and how it evolves across different layers.

This figure uses Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to visualize the positional vectors extracted from the first and seventh layers of a Transformer model. The left column shows the PCA visualization of the positional vectors from the first layer, demonstrating that the initial tokens show significantly distinct positional vectors, while subsequent tokens’ vectors are more similar. The right column shows the PCA visualization of positional vectors from the seventh layer, indicating that positional vectors are more evenly distributed across all positions in later layers. This visual comparison helps illustrate how positional information is distributed and changes over the layers of the model. This visualization supports the paper’s claim that after the first layer, initial tokens form distinct positional vectors, serving as anchors to shape positional vectors in later tokens.

This figure displays the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of positional vectors extracted from the first layer of four different large language models (LLMs): Llama-3-8B, Qwen1.5-7B, Yi-9B, and a newly trained model TL-NoPE-new. PCA is used to reduce the dimensionality of the positional vectors and visualize them in a 2D space. The plot helps to understand how positional information is represented differently across these models in the initial layers, providing insights into the formation and distribution of positional information.

This figure uses Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to visualize the positional vectors extracted from the hidden states of a Transformer model at two different layers: the first and the seventh. The visualizations show how the distribution of positional vectors changes as the model processes the input sequence. In the first layer, the initial tokens exhibit distinct positional vectors, while in the seventh layer, the vectors are more evenly distributed across all positions. This demonstrates how positional information is implicitly learned and encoded within the model’s hidden states during the processing of the input.

More on tables

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the effects of removing different components (value, positional vector, positional basis, and semantic vector) from the attention mechanism in two transformer models: TL-NoPE and TL-RoPE. The study evaluates both the cosine similarity between original and modified positional vectors (Sim) and the perplexity (PPL) on the RedPajama dataset. It shows the impact of each component on positional vector formation and overall model performance, indicating the relative importance of each component for maintaining positional information and achieving good generalization performance. Removing positional vectors and their basis from initial tokens leads to significantly lower similarity and higher PPL, highlighting their crucial roles in attention mechanisms.

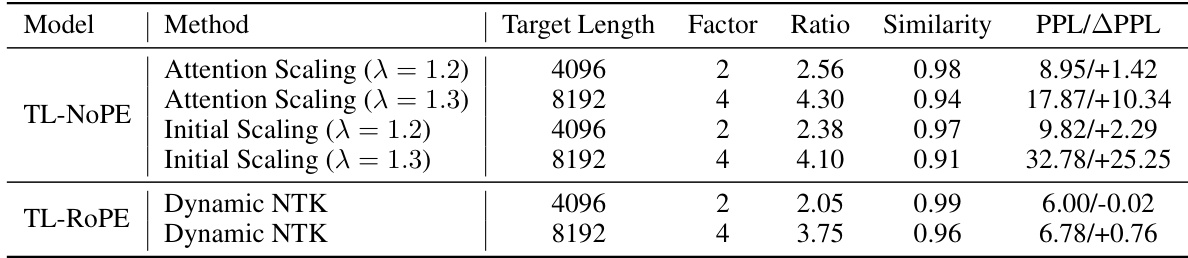

This table shows the results of positional vector interpolation experiments using two methods: Attention Scaling and Initial Scaling, applied to TL-NoPE and TL-ROPE models with different target lengths (4096 and 8192 tokens). The table presents the expansion factor of the context window, the effective interpolation ratio of positional vectors, the average cosine similarity between the interpolated and original vectors, and the resulting perplexity (PPL) and change in perplexity (ΔPPL). The results demonstrate the effectiveness of interpolation methods in improving the model’s performance on longer sequences, showing the relationship between interpolation ratio, similarity, and resulting perplexity.

This table presents the different model variants used in the paper’s experiments. The models vary in their attention mechanisms (full attention vs. windowed attention with different window sizes) and positional encoding schemes (no positional encoding, RoPE, and ALiBi). The table provides a concise overview of the model configurations used for comparison in the empirical analysis.

This table presents the results of an ablation study investigating the impact of removing different components (value, positional vector, positional basis, and semantic vector) from the attention mechanism on the cosine similarity (Sim) between positional vectors and perplexity (PPL) scores. The study examines two token groups: initial tokens (0-4) and subsequent tokens (32-256) in Llama-3, Yi-9B, Qwen-1.5-7B, and TL-NoPE-new. The results illustrate how the removal of different components affects both positional vector similarity and model performance (as measured by PPL).

This table presents the results of perplexity (PPL) and the cosine similarity of positional vectors during direct extrapolation. Three models with different context window sizes are evaluated: Llama-3-8B, Yi-9B, and TL-NoPE-new. For each model, the PPL at the original context window size (C) and twice the context window size (2C) are reported, along with the cosine similarity between positional vectors within and beyond the context window (Simi(2C)). The results demonstrate that direct extrapolation generally leads to a significant increase in PPL, and this increase is accompanied by a decrease in the similarity of positional vectors.

This table presents the results of an experiment that investigates the effect of exceeding the context window on the attention mechanism and the output logits in various LLMs. It displays the attention sink (a measure of the attention assigned to the initial tokens) and the similarity of logits (a measure of the consistency of the output) within and beyond the context window. The results demonstrate a significant decrease in attention sink and similarity of logits as the input length goes beyond the context window.

This table presents the results of language modeling experiments conducted on the PG-19 dataset using the TL-NoPE-new model. It compares the performance of three different context window extension methods: no method (baseline), Attention Scaling, and Positional Vector Replacement. The results show perplexity (PPL) scores for each method across different target lengths (2048, 4096, 6144, and 8192 tokens). The ‘Factor’ column indicates the extent of context window extension applied.

Full paper#