↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Expectation propagation (EP) is a powerful approximate inference technique, but its naive application struggles with the inherent noise in Monte Carlo (MC) estimations, especially when dealing with high-dimensional data. Previous attempts to address this issue using debiasing techniques often require many MC samples, impacting efficiency. This paper points out these limitations of current EP implementations.

This research introduces two novel EP variants, EP-η and EP-μ, that overcome the MC noise problem. By framing EP updates as natural gradient optimization, the authors derive updates well-suited for MC estimation and stable even with a single sample. The improved stability and sample efficiency of EP-η and EP-μ, along with easier tuning and better speed-accuracy trade-offs, extend EP’s applicability to more complex problems. Their efficacy is demonstrated on various probabilistic inference tasks.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with expectation propagation (EP), particularly those dealing with high-dimensional data or models where moment calculations are computationally expensive. The proposed methods offer a significant improvement in speed and accuracy, enabling broader application of EP to complex real-world problems. The new framework opens avenues for further research into natural gradient methods for Bayesian inference, and the development of more sample-efficient algorithms.

Visual Insights#

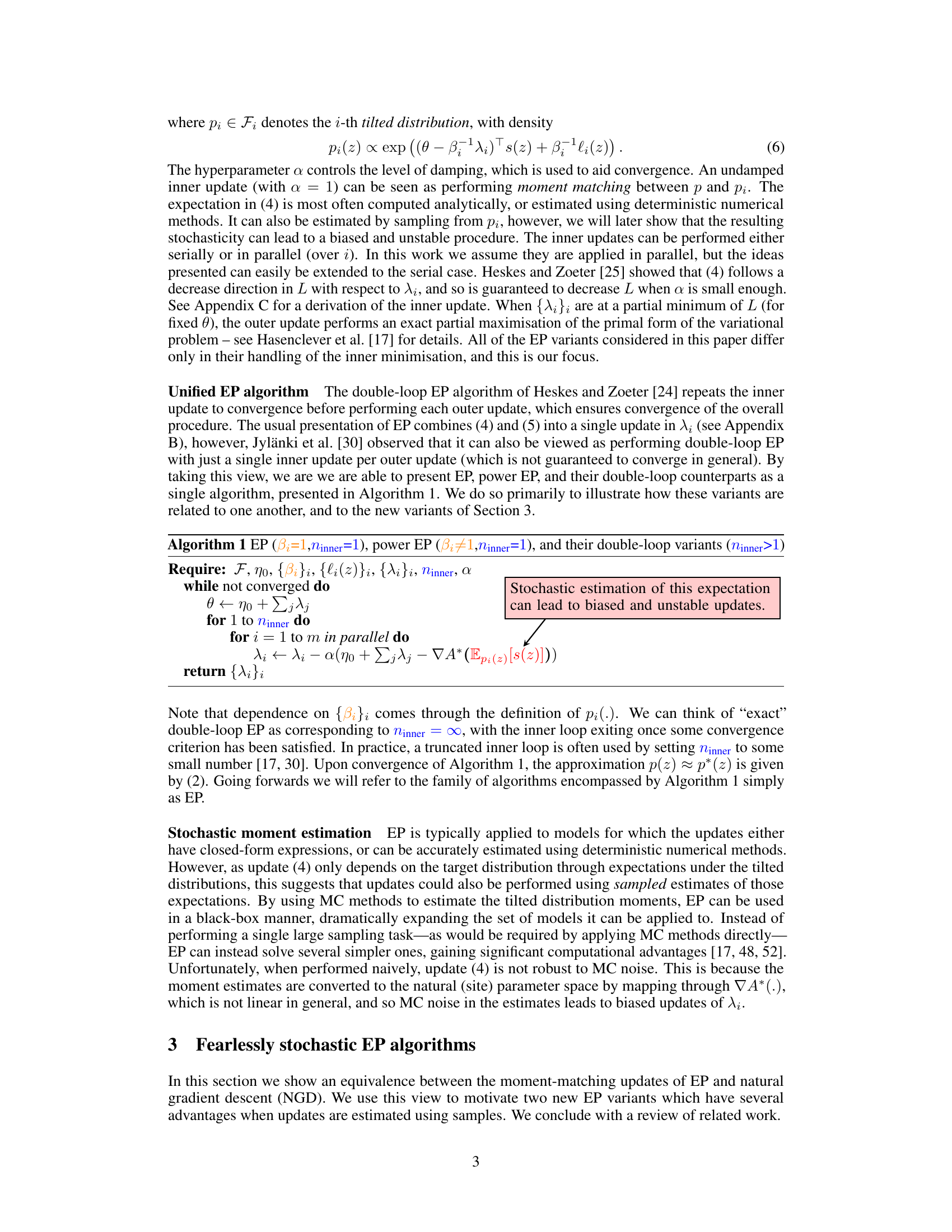

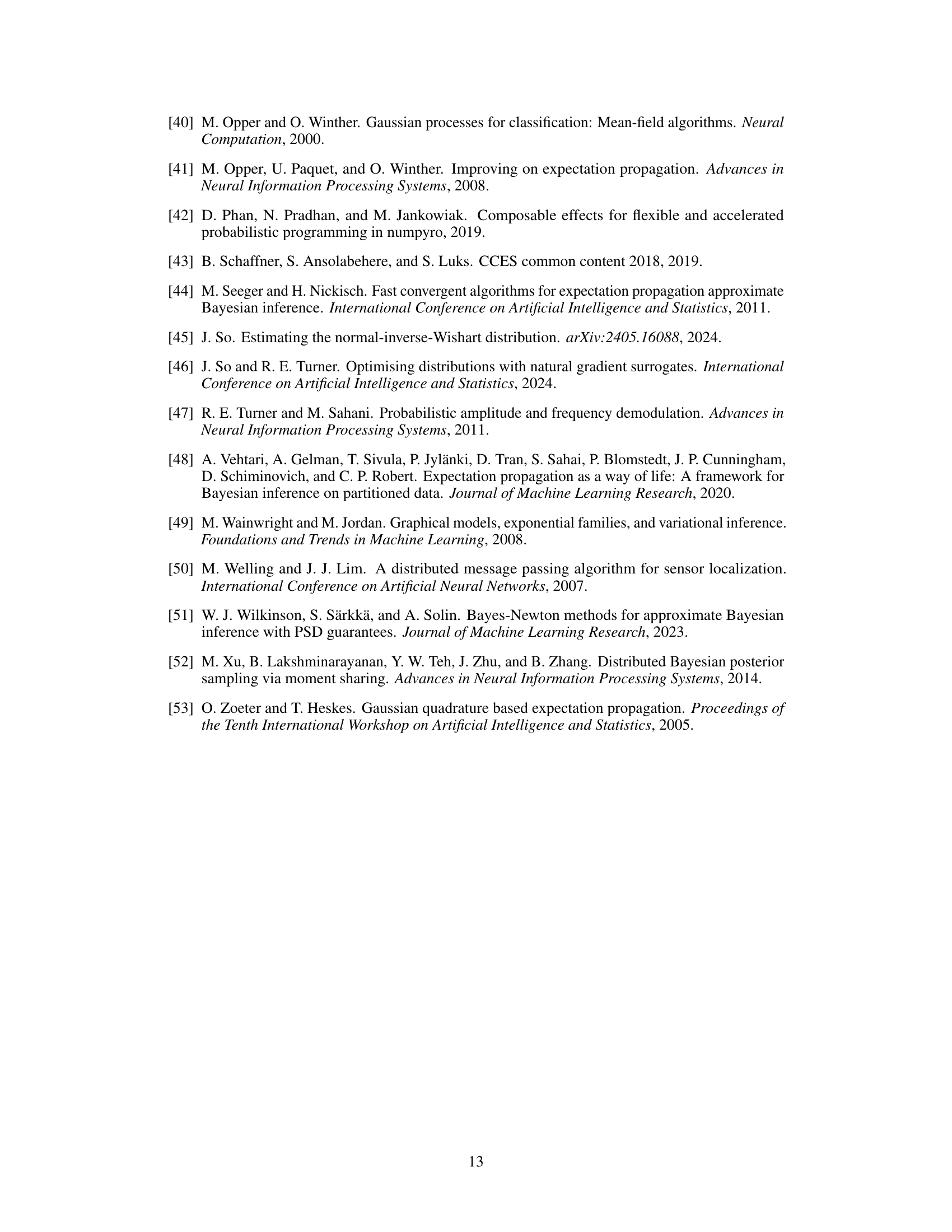

This figure analyzes the effect of step size and the number of Monte Carlo samples on different Expectation Propagation (EP) variants. It shows that the new EP-η and EP-μ variants are more robust to Monte Carlo noise and more sample efficient than previous methods, particularly when using a single sample. The left panel displays the expected decrease in the loss function L, while the right panel shows the bias in the site parameter λᵢ after a single update.

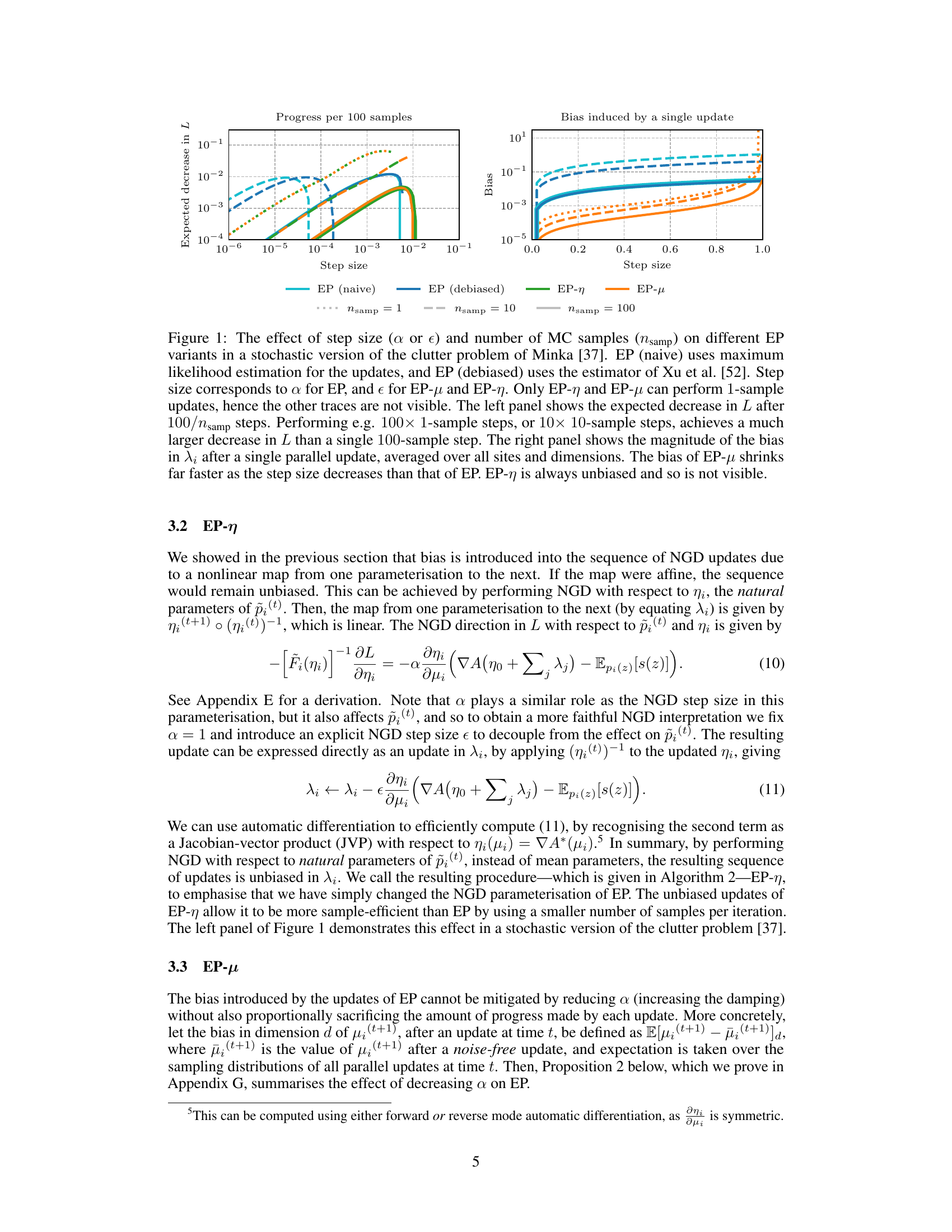

This algorithm presents a unified view of Expectation Propagation (EP), power EP, and their double-loop variants. It highlights the iterative process of inner and outer updates to optimize a variational objective. The inner updates involve moment-matching, which can be estimated stochastically (as shown in the caption’s note), potentially leading to instability and bias. The algorithm takes as input the exponential family of distributions (F), the natural parameter (η₀), site potentials ({pᵢ}ᵢ), likelihood terms ({lᵢ(z)}ᵢ), site parameters ({λᵢ}ᵢ), number of inner iterations (ninner), and damping parameter (α). It then iteratively updates θ and λᵢ until convergence, finally returning the optimized site parameters.

In-depth insights#

Stochastic EP#

The concept of ‘Stochastic EP’, referring to Expectation Propagation (EP) algorithms adapted for stochastic estimation, presents a significant advancement in approximate Bayesian inference. Traditional EP relies on exact moment calculations, often infeasible for complex models. Stochastic EP addresses this limitation by replacing exact moments with Monte Carlo (MC) estimates, extending EP’s applicability to a much wider range of models. However, naively applying MC estimates leads to instability and bias. The core innovation lies in framing EP updates as natural gradient descent, enabling the development of more robust variants like EP-η and EP-μ that are more sample-efficient, particularly when using single-sample estimations. These variants address key weaknesses of previous stochastic EP approaches by reducing bias and improving stability without requiring computationally expensive debiasing techniques. The theoretical framework and empirical results demonstrate the efficacy of these improved algorithms across several probabilistic inference tasks, showcasing their enhanced speed and accuracy in settings where conventional methods struggle.

Natural Gradient EP#

The concept of “Natural Gradient EP” presents a novel perspective on Expectation Propagation (EP), framing its moment-matching updates as natural-gradient-based optimization of a variational objective. This reframing offers crucial insights into EP’s behavior, particularly its robustness (or lack thereof) when using Monte Carlo (MC) estimations. By viewing EP through this lens, the authors propose two new EP variants, EP-η and EP-μ, specifically designed for MC estimation. These variants exhibit improved sample efficiency and stability, even when estimated using a single sample. The key advantage lies in their ability to mitigate the bias introduced by naively converting noisy MC estimates to the natural parameter space, a common weakness of standard EP. The proposed algorithms represent a significant advancement in robust and efficient approximate Bayesian inference, particularly within the context of high-dimensional and complex models where direct moment calculations are intractable.

EP-η and EP-μ#

The proposed EP-η and EP-μ algorithms offer a novel approach to expectation propagation (EP), addressing limitations of previous methods. EP-η leverages a natural-gradient perspective, performing optimization directly in the natural parameter space, leading to unbiased updates and enhanced sample efficiency, even with a single Monte Carlo sample. In contrast, EP-μ optimizes in the mean parameter space, offering a computationally simpler alternative with a reduced bias compared to standard EP. Both methods demonstrate improved speed and accuracy, effectively handling MC noise, unlike standard EP or previous debiased versions. This robustness results from the inherent stability of natural-gradient approaches, and avoids the need for computationally costly debiasing techniques. The improved performance is validated empirically across diverse probabilistic inference tasks. The authors provide a compelling theoretical justification, supporting the claims through rigorous mathematical proofs and demonstrating the practical advantages of these new methods.

Experimental Results#

The Experimental Results section of a research paper is crucial for demonstrating the validity and impact of the proposed methods. A strong section will present results clearly and comprehensively, comparing the new approach against relevant baselines. Visualizations, such as graphs and tables, are essential for quickly conveying key findings. The discussion should highlight significant improvements, focusing on both quantitative metrics and qualitative observations. Statistical significance testing should be rigorously applied and clearly reported. A good section will also acknowledge limitations or unexpected results, providing a balanced and honest presentation. Crucially, the results should directly support and validate the claims made in the introduction and abstract. Sufficient detail should be given to allow for reproduction of the experiments, including parameters, settings, and data used. The experimental setup should be described in detail to allow for independent verification and validation of the findings.

Future Directions#

The ‘Future Directions’ section of this research paper would ideally delve into several promising avenues. Extending the fearless stochastic EP algorithms to a broader class of models beyond those explored is crucial, potentially by investigating novel sampling strategies tailored to specific model structures. Improving the efficiency of the underlying sampling kernels is another key area, especially for high-dimensional problems where drawing independent samples can be computationally expensive. Developing hybrid approaches that leverage both the sample efficiency of EP and the accuracy of other methods like CVI could yield significant improvements. Exploring how to efficiently parallelize EP updates across distributed systems would also be beneficial. Finally, a theoretical exploration of the implicit geometry of EP variants and their relationship to other optimization methods would deepen our understanding. Addressing the bias inherent in the update rule, even with the proposed improvements, warrants further investigation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

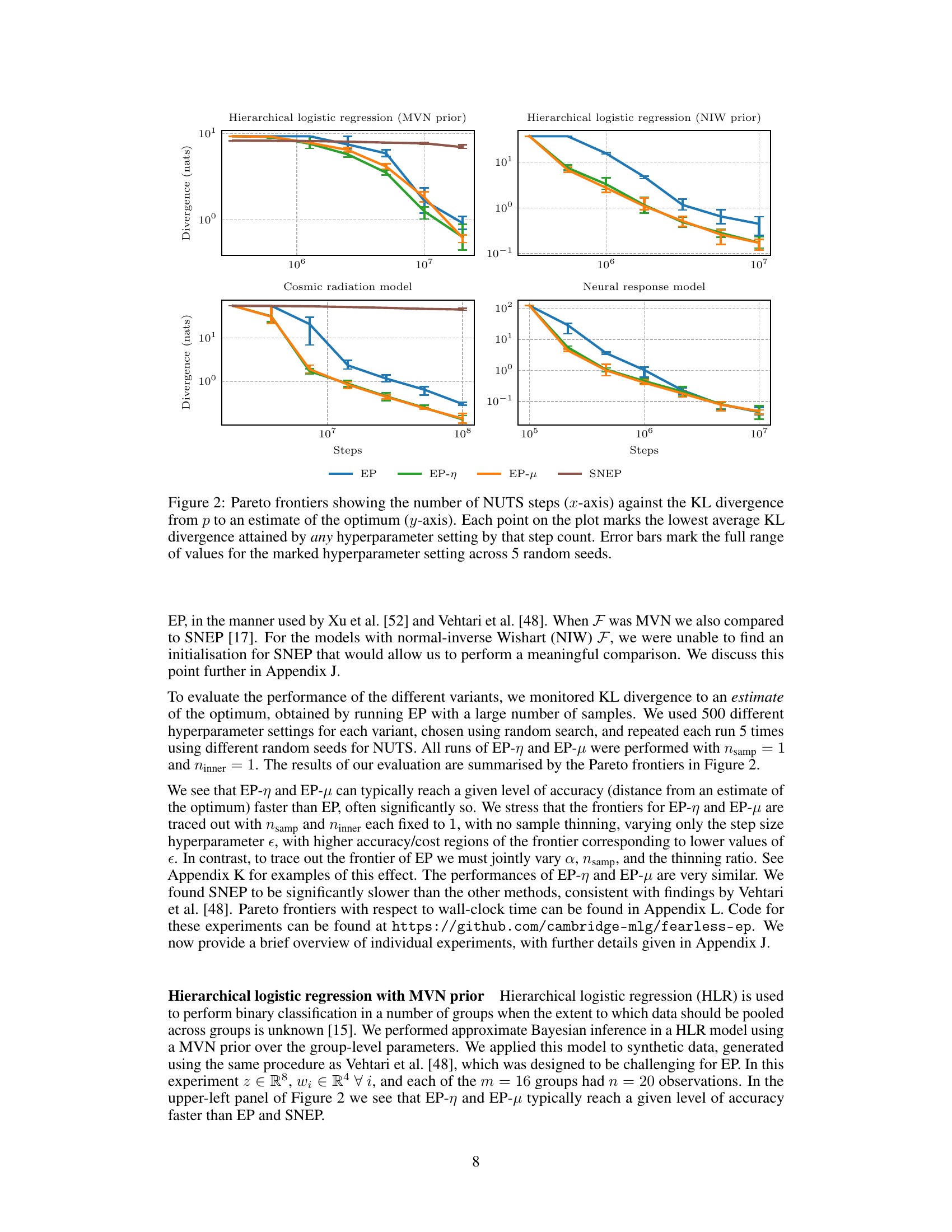

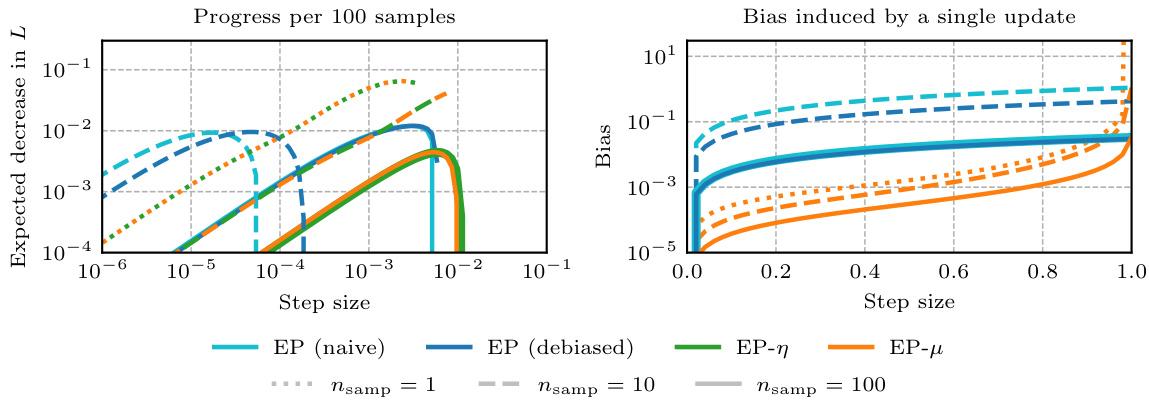

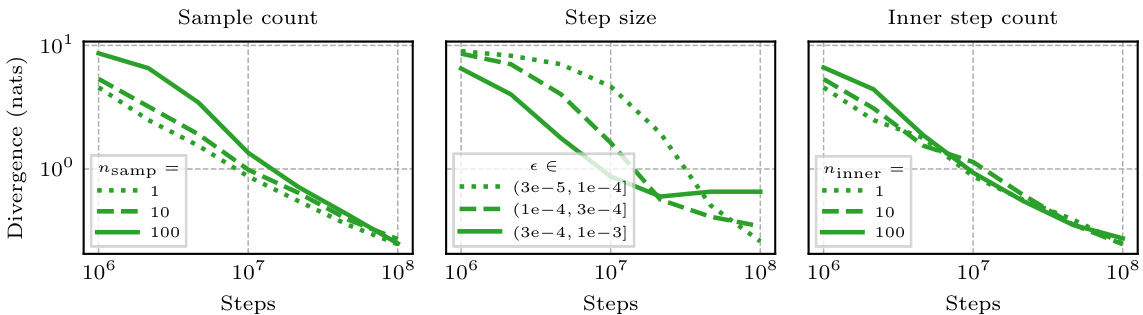

This figure compares the performance of different expectation propagation (EP) variants in terms of the number of NUTS steps required to reach a certain level of accuracy, measured by the KL divergence from the approximate posterior to the true posterior. Each point represents the lowest average KL divergence achieved at a given number of NUTS steps, across different hyperparameter settings. The error bars indicate the range of KL divergences obtained across five random seeds.

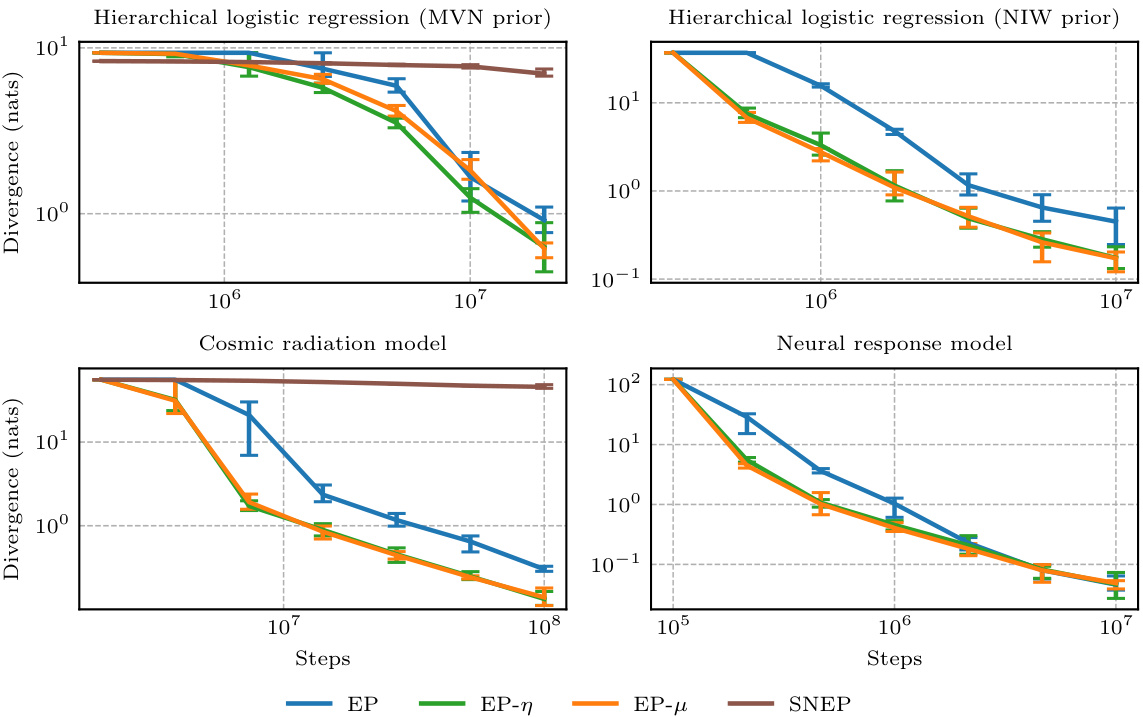

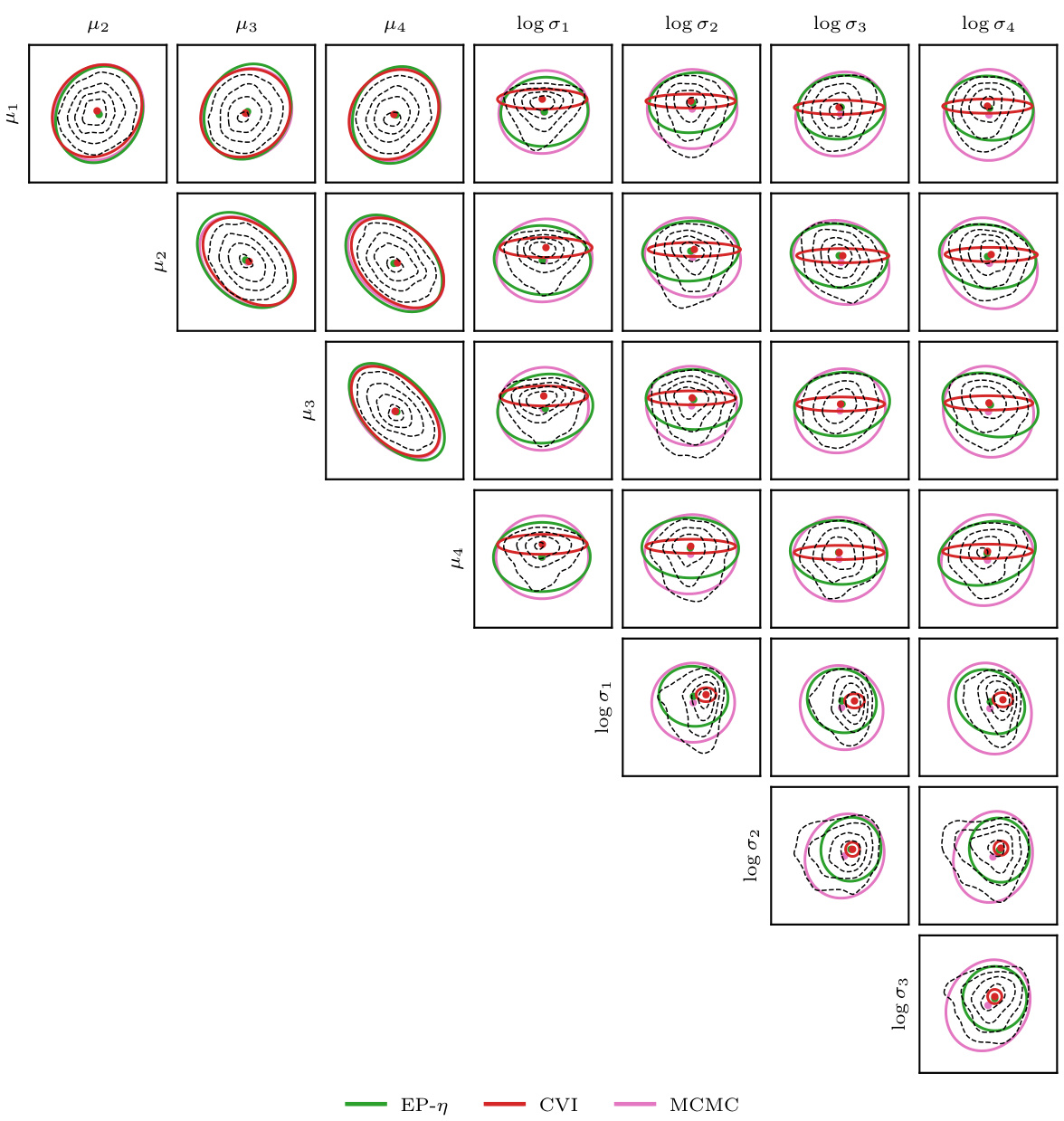

This figure compares the performance of EP-η against conjugate-computation variational inference (CVI) on a hierarchical logistic regression model. It shows KL divergence (forward and reverse) plots against both wall-clock time (using NUTS for sampling) and the number of samples drawn (using an ‘oracle’ sampling kernel). Pairwise posterior marginals are also displayed to visually compare the accuracy of the different methods.

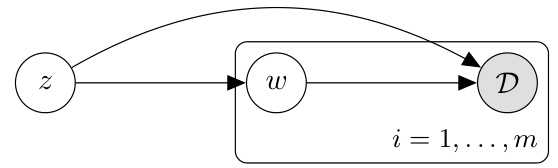

This figure shows the graphical model used for the experiments in Section 4. It illustrates the hierarchical structure where global parameters z influence local latent variables w which in turn influence the observed data D. There are m repeated instances of the w → D portion of the model, one for each data partition.

This figure compares the performance of different Expectation Propagation (EP) variants when using Monte Carlo (MC) sampling to estimate the updates. It shows that the new variants, EP-η and EP-μ, are more robust to MC noise and more sample-efficient than previous methods. The left panel illustrates the improvement in the variational objective (L) achieved by using multiple 1-sample updates compared to a single large-sample update. The right panel demonstrates how the bias in the updates decreases as the step size reduces for EP-μ, while EP-η remains unbiased.

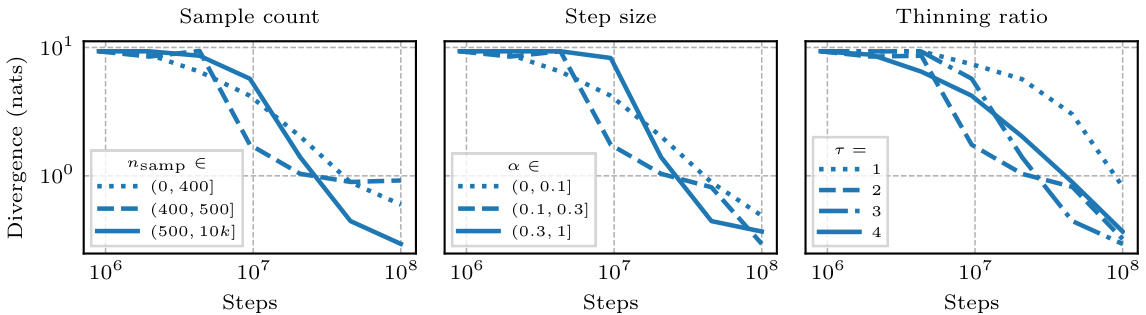

This figure compares the performance of different Expectation Propagation (EP) variants under different step sizes and numbers of Monte Carlo (MC) samples. It shows that the new variants, EP-η and EP-μ, are more robust to MC noise and more sample-efficient than previous methods, especially when using only a single sample per update.

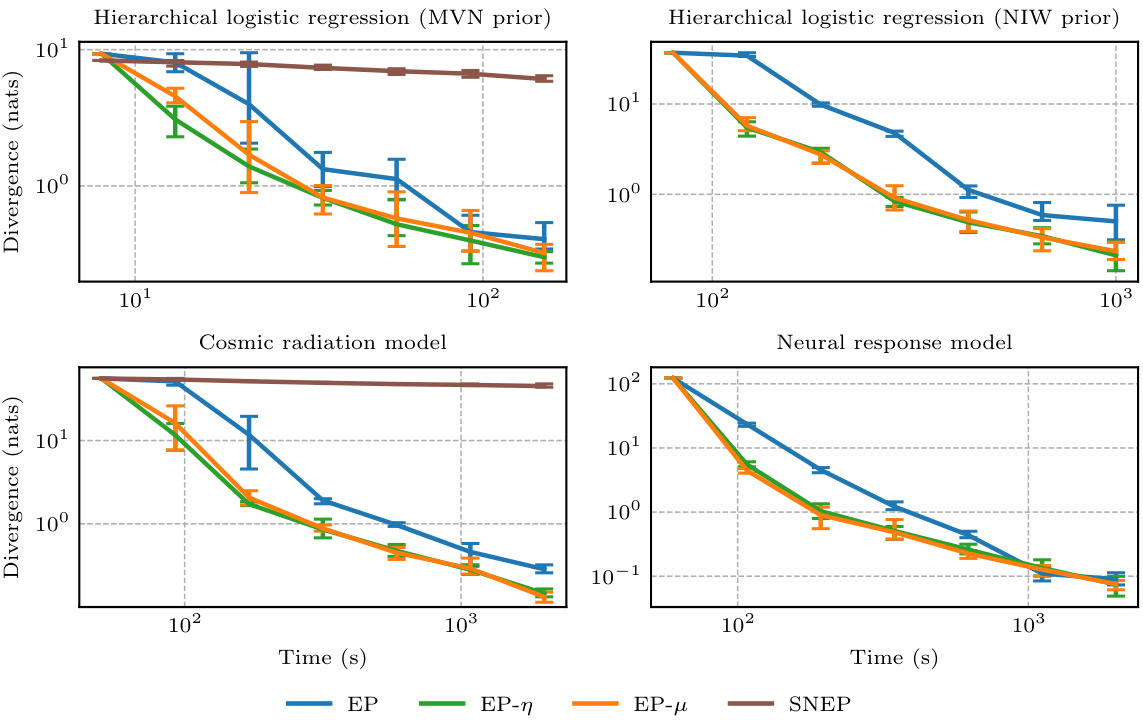

This figure presents Pareto frontiers illustrating the trade-off between computation time (in seconds) and the KL divergence from the approximate posterior (p) to the true posterior (obtained via a high-sample estimate). Each point represents the lowest average KL divergence achieved at a given time point across five different random seeds. The error bars reflect the range of KL divergences observed across these seeds for each hyperparameter configuration.

This figure compares the performance of EP-η and conjugate-computation variational inference (CVI) on a hierarchical logistic regression model. The left two plots illustrate the KL divergence (both forward and reverse) between the approximations and a true posterior (estimated with MCMC). The left plot shows time comparison, and the middle plot shows sample comparison using an ‘oracle’ sampling kernel for EP-η to remove the effect of the sampler. The right two plots show pairwise posterior marginals for both methods against the true posterior marginals, showing that EP-η is closer to the truth. The discussion of the results and further details can be found in section 5 and appendix M.

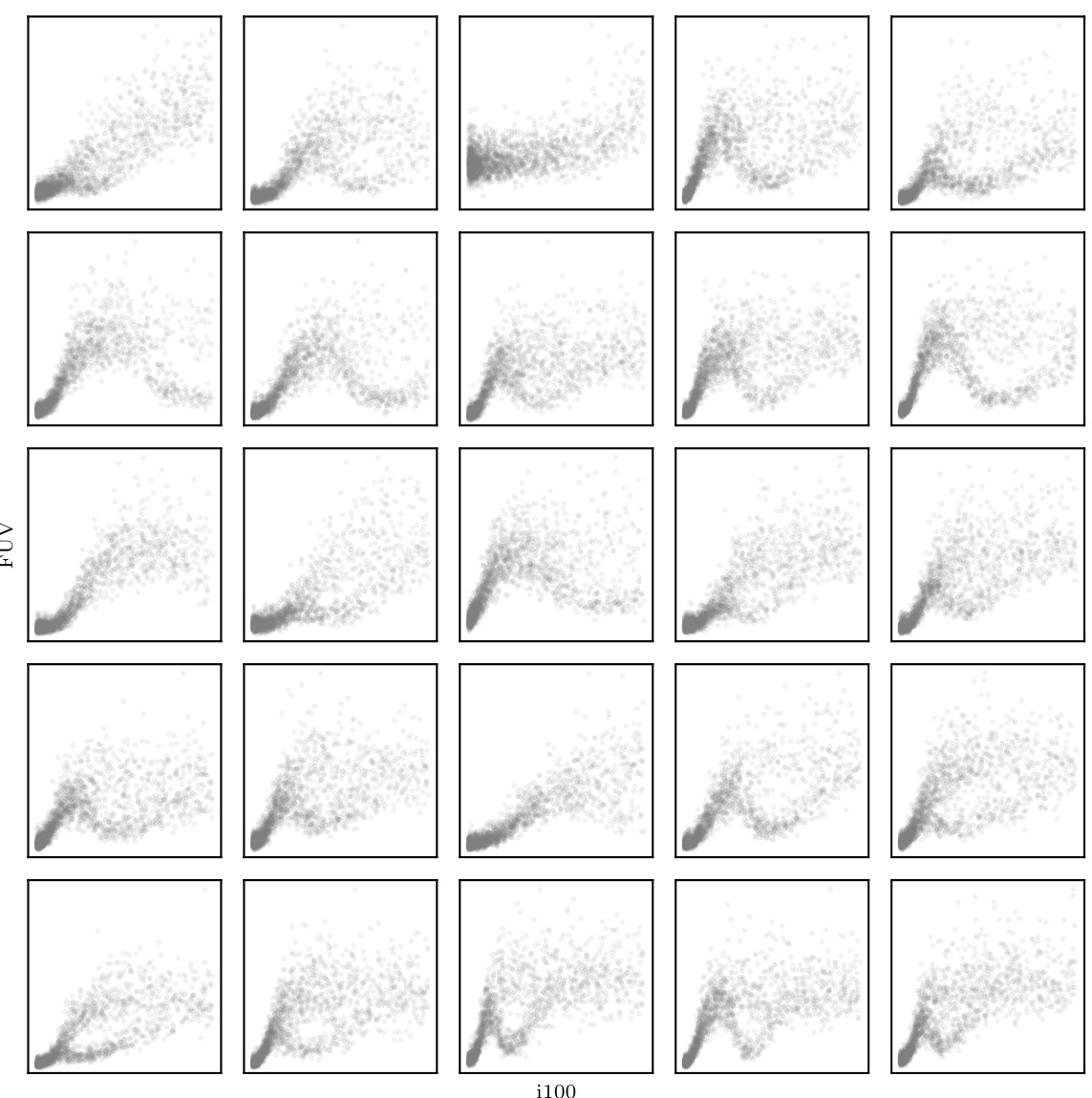

This figure shows scatter plots of synthetic data generated to mimic the cosmic radiation data used in Vehtari et al. [48]. Each subplot represents a single sector of the observable universe, plotting the galactic far ultraviolet radiation (FUV) against the 100-µm infrared emission (i100). The data was generated using parameters manually tuned to match the qualitative properties of the original dataset.

Full paper#