↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

High costs and complex setups hinder robotics and reinforcement learning (RL) research. This limits contributions from researchers, educators, and hobbyists. Existing platforms are often expensive and require specialized skills and equipment.

BricksRL, a novel open-source platform, addresses these issues. It leverages the affordability and modularity of LEGO robots, combined with the TorchRL library for RL agents. This allows for cost-effective creation, design, and training of custom robots, simplifying the integration between the real world and state-of-the-art RL algorithms. Experiments show that inexpensive LEGO robots can be trained to perform simple tasks efficiently using BricksRL.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it democratizes access to robotics and reinforcement learning research, lowering the barrier to entry for researchers, educators, and hobbyists. The use of LEGO robots and open-source software makes it cost-effective and accessible, paving the way for wider participation and innovation in the field. The successful integration of non-LEGO sensors further highlights its flexibility and potential impact.

Visual Insights#

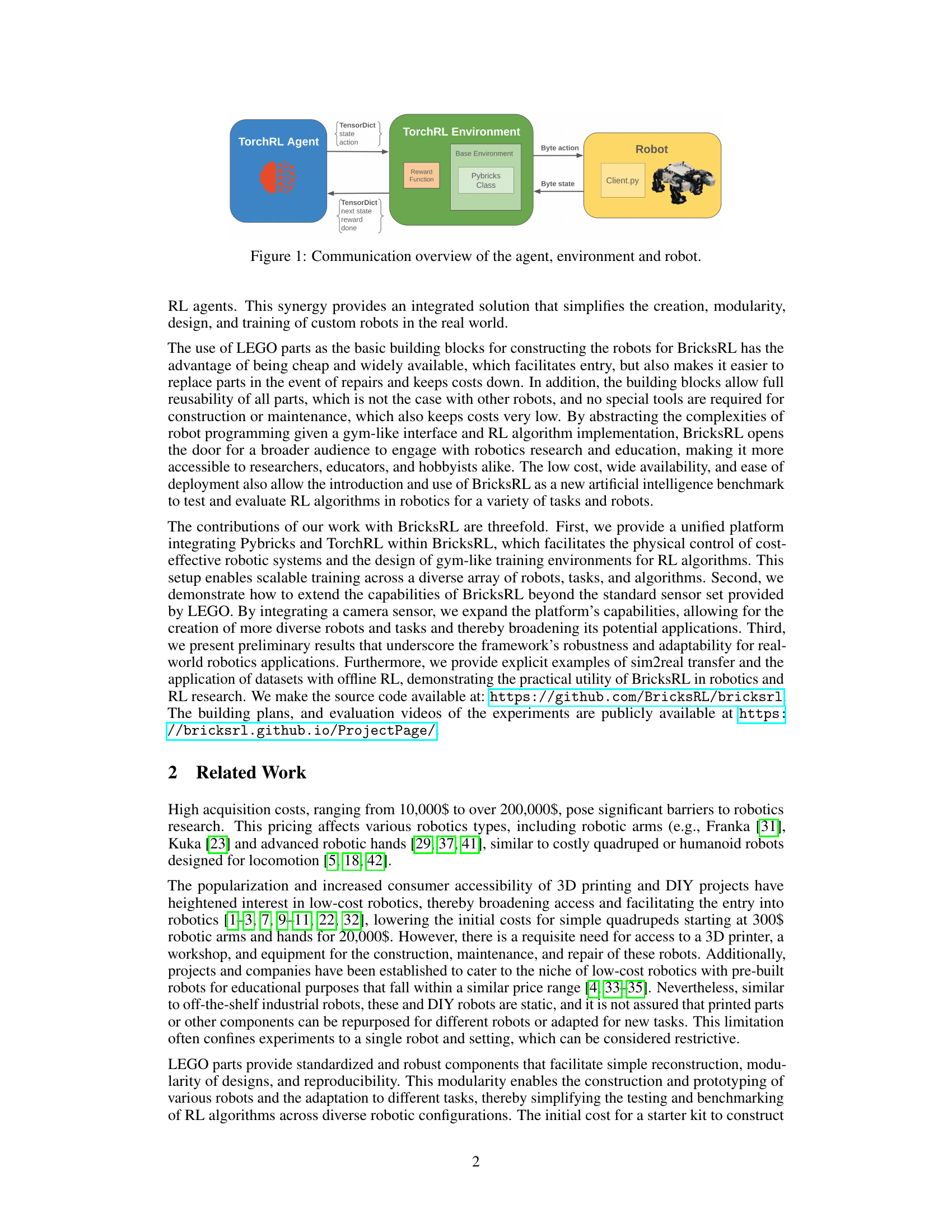

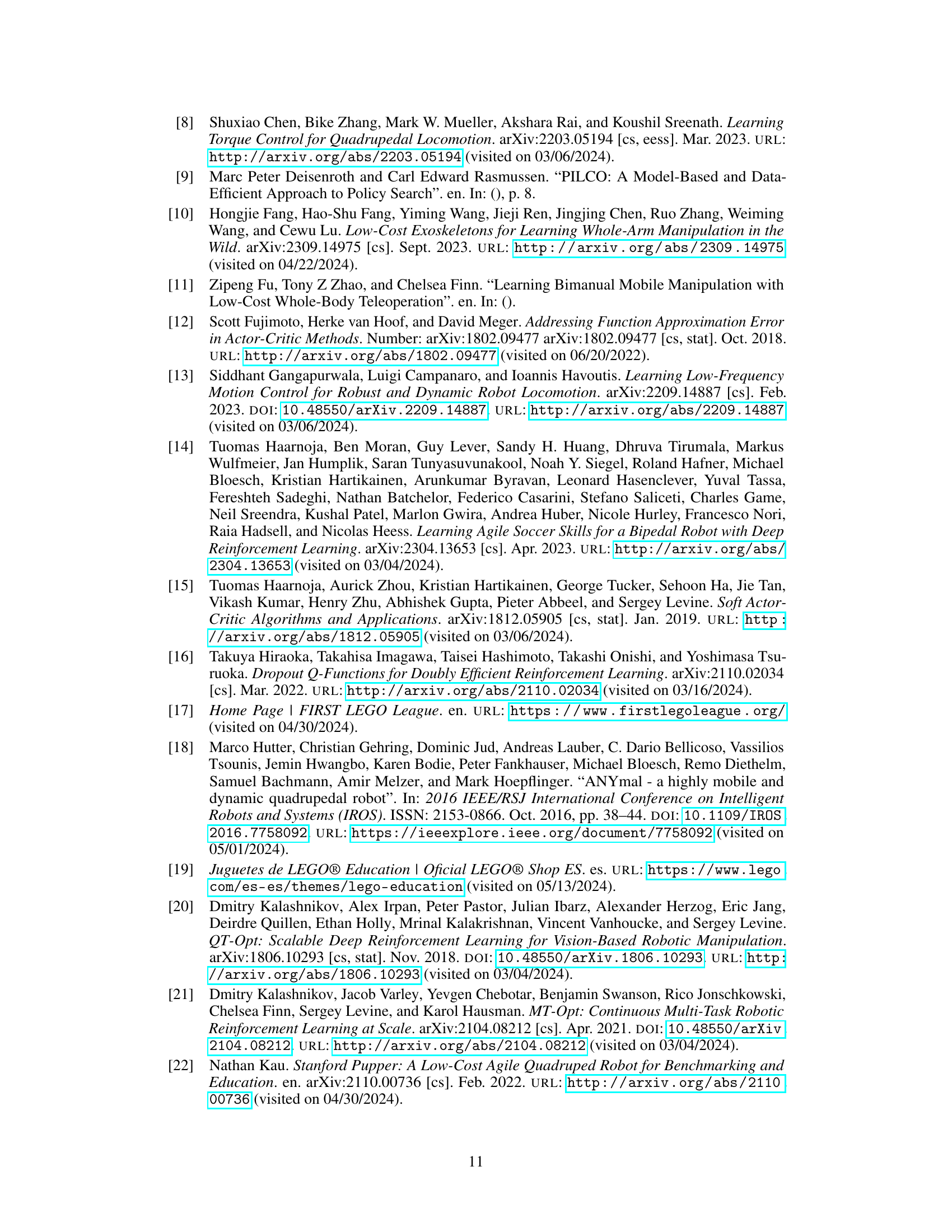

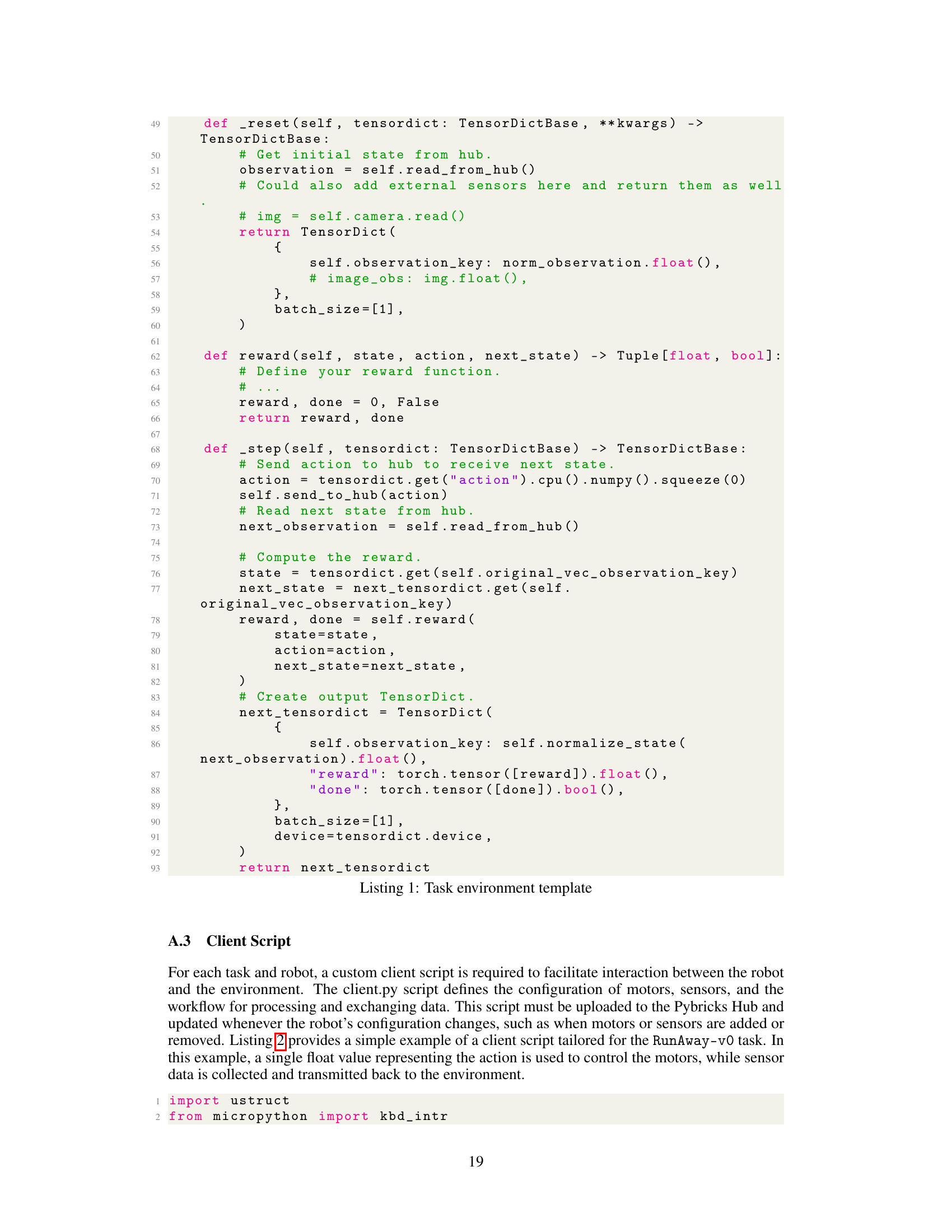

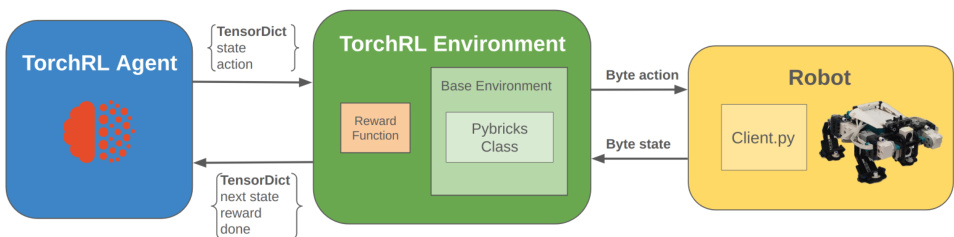

This figure illustrates the communication flow and data exchange between the three main components of the BricksRL platform: the TorchRL agent, the TorchRL environment, and the LEGO robot. The agent sends actions (as byte actions) to the environment via TensorDict. The environment, incorporating Pybricks Class for robot control and a reward function, processes these actions, interacts with the robot (via Client.py), receives state information (as byte states) from the robot, and provides the reward and next state back to the agent via TensorDict.

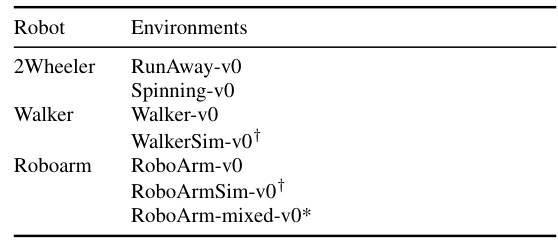

This table shows the robots used in the experiments and the environments they were tested in. The asterisk (*) indicates environments that use both LEGO sensors and image data, while the dagger (†) indicates simulated environments that do not involve the physical robot.

In-depth insights#

BricksRL: LEGO Robotics#

BricksRL is a novel platform leveraging LEGO bricks and the TorchRL reinforcement learning library to democratize robotics research and education. Its low cost and accessibility make it ideal for a wide range of users, from students to seasoned researchers. The platform’s modularity allows for easy creation and modification of custom LEGO robots, facilitating experimentation with various robot designs and tasks. The seamless integration of TorchRL simplifies the process of training RL agents on real-world robots, significantly reducing the barrier to entry for reinforcement learning research. BricksRL’s comprehensive open-source framework, combined with detailed documentation and readily available resources, empowers users to build, modify, and train their own LEGO-based robots. Its versatility further extends to incorporating non-LEGO sensors, showcasing enhanced adaptability and potential for diverse applications. By lowering the technical and financial obstacles in robotics research, BricksRL can significantly contribute to advancements in the field and promote broader participation in STEM education.

RL Algorithm Integration#

The seamless integration of reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms is a cornerstone of the BricksRL platform. TorchRL’s modularity allows for straightforward incorporation of various state-of-the-art algorithms (TD3, SAC, DroQ) simplifying experimentation and promoting reproducibility. BricksRL’s design prioritizes accessibility, enabling researchers and educators with varying levels of RL expertise to effectively utilize and adapt advanced algorithms. The gym-like interface further enhances usability, abstracting away complex robotic programming details. The platform’s capacity for sim2real transfer allows training in simulated environments before deploying to real-world LEGO robots, streamlining the learning process. Furthermore, the platform is not limited to standard algorithms; its modularity facilitates the integration of other methods and opens up new possibilities for exploration within the RL field and real-world robotic applications.

Modular Robot Design#

Modular robot design offers significant advantages in robotics, enabling adaptability and scalability not readily achievable with monolithic designs. The use of standardized, interchangeable modules allows for easy customization and repair, reducing development time and cost. LEGO bricks, for example, represent a readily available and cost-effective modular system, facilitating experimentation and education. However, challenges exist in ensuring consistent performance across different module combinations and managing the complexity of inter-module communication and control. Standardization of interfaces and communication protocols is crucial for widespread adoption of modular robotics. The modular approach fosters reproducibility, enabling researchers to easily replicate experiments and facilitating collaborative development. Future research should focus on improving inter-module communication efficiency, creating more sophisticated modular building blocks, and developing advanced control systems for managing the inherent complexity of modular robots.

Sim2Real Transfer#

Sim2Real transfer, bridging the gap between simulated and real-world robotic learning, is a crucial yet challenging aspect of reinforcement learning. Success hinges on effectively transferring policies learned in simulation to the real robot, requiring careful consideration of various factors. Accurate simulation models are paramount, minimizing the ‘reality gap’ by meticulously modeling robot dynamics, sensor noise, and environmental uncertainties. Domain randomization, a technique used to enhance robustness, involves introducing variability into simulation parameters, improving generalization. Data augmentation techniques, like adding noise or creating synthetic data, further aids in this process. However, successful transfer isn’t solely dependent on simulation fidelity; careful design of reward functions and training algorithms also play key roles. Addressing discrepancies in state and action spaces between simulation and reality, like compensating for sensor noise or mechanical imperfections, is vital. Thorough evaluation is crucial, comparing the performance of sim2real policies against real-world trained policies, which reveals the effectiveness of the transfer process. BricksRL, as showcased in the paper, effectively leverages these concepts for successful sim2real transfer using inexpensive LEGO robots, underscoring the democratization potential of this approach.

Offline RL for LEGO#

Offline reinforcement learning (RL) applied to LEGO robotics presents a unique opportunity to bridge the gap between simulated and real-world environments. LEGO’s modularity and affordability create a cost-effective and accessible platform for researchers and educators. Dataset generation, involving expert and random policy data collection, is crucial for effective offline RL training, enabling algorithms to learn complex behaviors from collected experiences without continuous real-time interaction. Sim2real transfer becomes vital, as models trained offline in simulation need robust adaptation to the real-world complexities of LEGO robots, including noise, backlash, and inaccuracies. The success of offline RL in this context highlights the potential for democratized robotics research, making advanced RL techniques accessible to a broader audience. Future research should explore strategies for improving dataset generation methods and sim2real transfer techniques to make offline RL training even more effective and reliable.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows three different LEGO robots used in the experiments described in the paper. (a) shows a simple two-wheeled robot, (b) shows a quadrupedal walking robot, and (c) shows a robotic arm. These robots represent a range of complexity and demonstrate the versatility of the BricksRL platform for building and controlling various robotic designs.

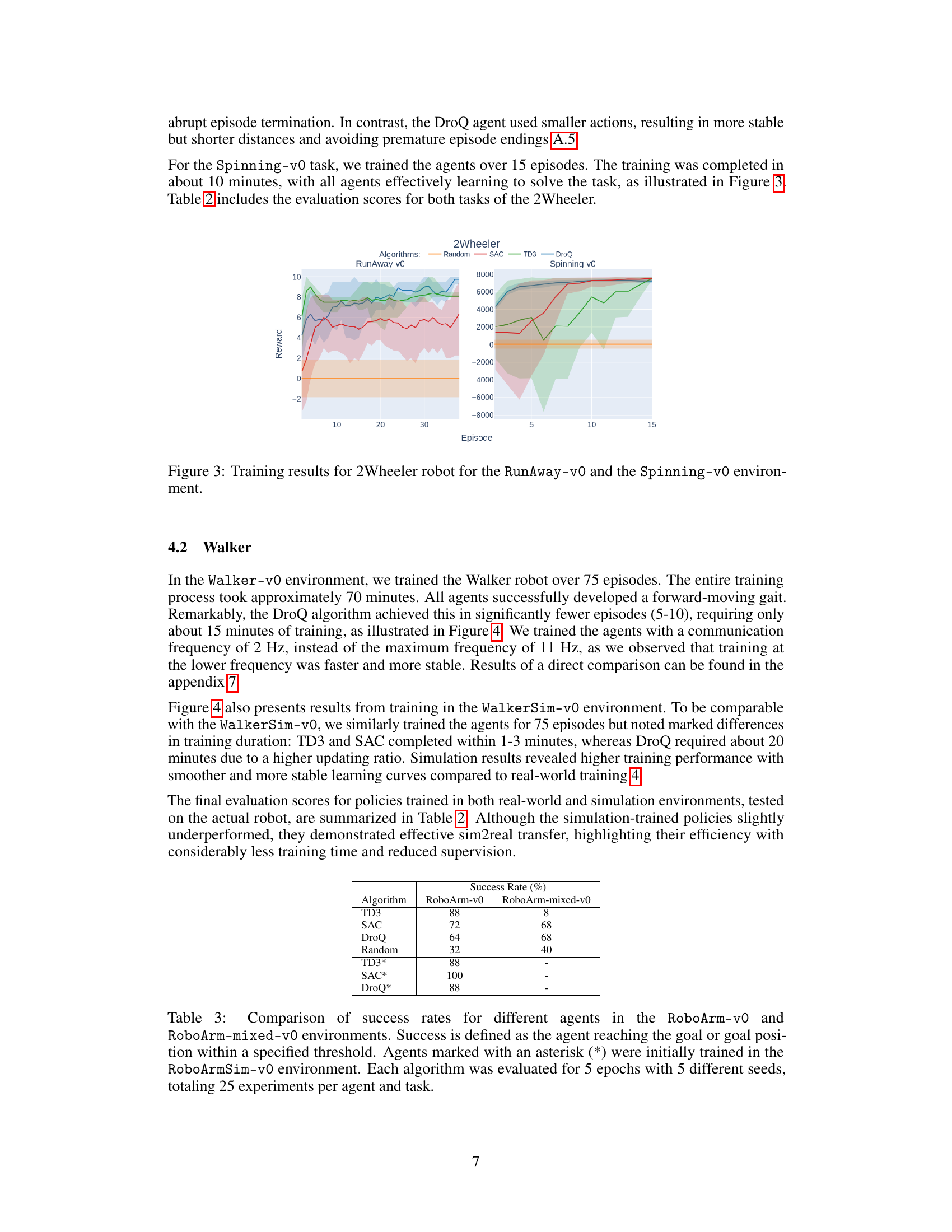

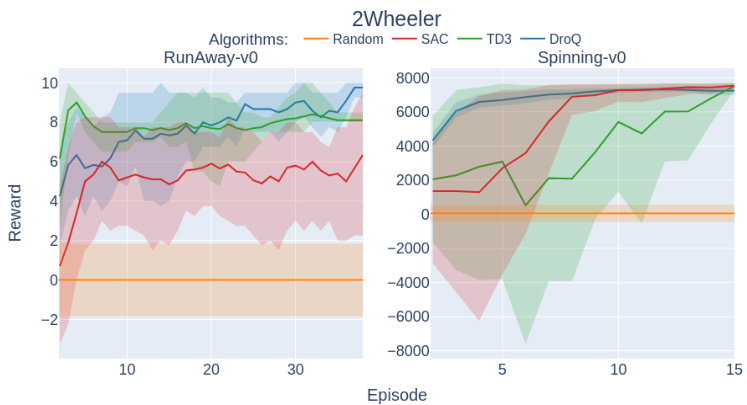

This figure shows the training performance of the 2Wheeler robot on two different tasks: RunAway-v0 and Spinning-v0. The left subplot (RunAway-v0) illustrates the reward obtained by four different reinforcement learning algorithms (Random, SAC, TD3, DroQ) over 40 training episodes. It shows the average reward with shaded standard deviation areas. The right subplot (Spinning-v0) displays the same information but over 15 episodes for the Spinning-v0 task. The figure visually demonstrates the learning progress of the algorithms on each task and allows a comparison of their performance.

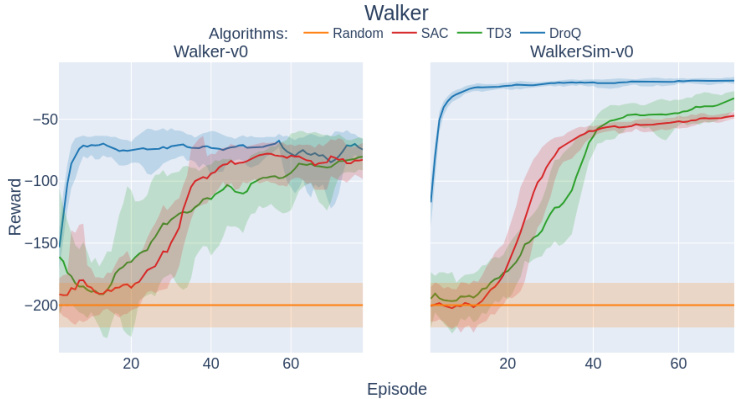

This figure compares the training performance of different reinforcement learning algorithms (Random, SAC, TD3, DroQ) on two environments for the Walker robot: the real-world Walker-v0 environment and its simulated counterpart, WalkerSim-v0. The x-axis represents the episode number, and the y-axis shows the reward obtained during training. Shaded areas indicate the standard deviation across multiple training runs. The figure illustrates the learning curves of each algorithm, highlighting their performance in both real-world and simulated scenarios, and how they compare against a random baseline.

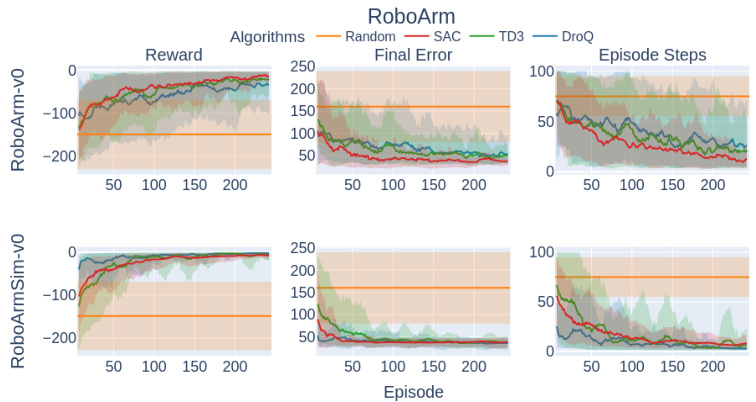

This figure shows the training performance comparison of different reinforcement learning algorithms (Random, SAC, TD3, DroQ) for the RoboArm robot in two environments: the real-world RoboArm-v0 and the simulated RoboArmSim-v0. For each environment and algorithm, three plots are presented: reward, final error (the difference between the robot’s final pose and the target pose at the end of each episode), and episode steps (the number of steps taken to complete each episode). The shaded areas represent the standard deviation across multiple training runs.

This figure displays the training performance of the RoboArm robot within the RoboArm_mixed-v0 environment. The left subplot shows the reward obtained across training episodes for four different reinforcement learning algorithms (Random, SAC, TD3, DroQ). The right subplot shows the number of episode steps taken to reach the target location for each algorithm. The shaded areas represent the standard deviation across multiple trials for each algorithm. This figure demonstrates the algorithms’ learning curves and how quickly each method converges (or fails to converge) on the task, which integrates both motor angle controls and a webcam image for more complex decision-making compared to the simpler robot setups.

This figure compares the performance of the DroQ algorithm on the Walker-v0 task using two different communication frequencies: 11 Hz and 2 Hz. The plot shows the reward obtained over 70 episodes. It demonstrates that a lower communication frequency (2 Hz) leads to faster and more stable convergence, potentially due to the effect being similar to frame skipping in RL, which simplifies decision-making.

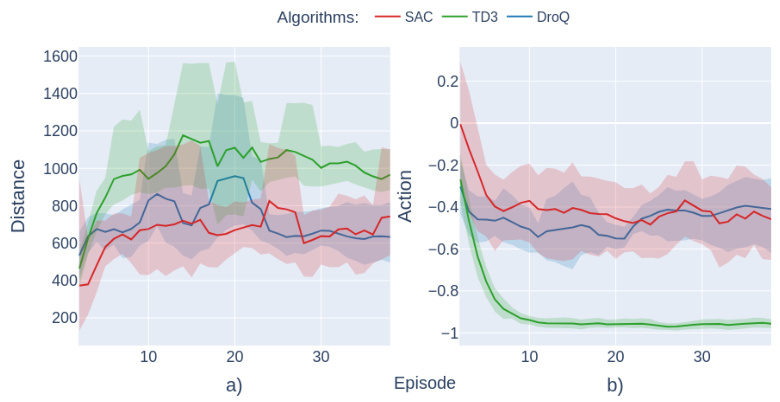

This figure shows the results of the RunAway-v0 task. The left subplot (a) displays the final distance achieved by three different reinforcement learning algorithms (SAC, TD3, DroQ) over multiple episodes. The shaded area represents the standard deviation. The right subplot (b) shows the mean action taken by each algorithm over the same episodes. Again, the shaded area represents the standard deviation. This illustrates the different strategies adopted by each algorithm to maximize the distance travelled while avoiding hitting a wall.

More on tables

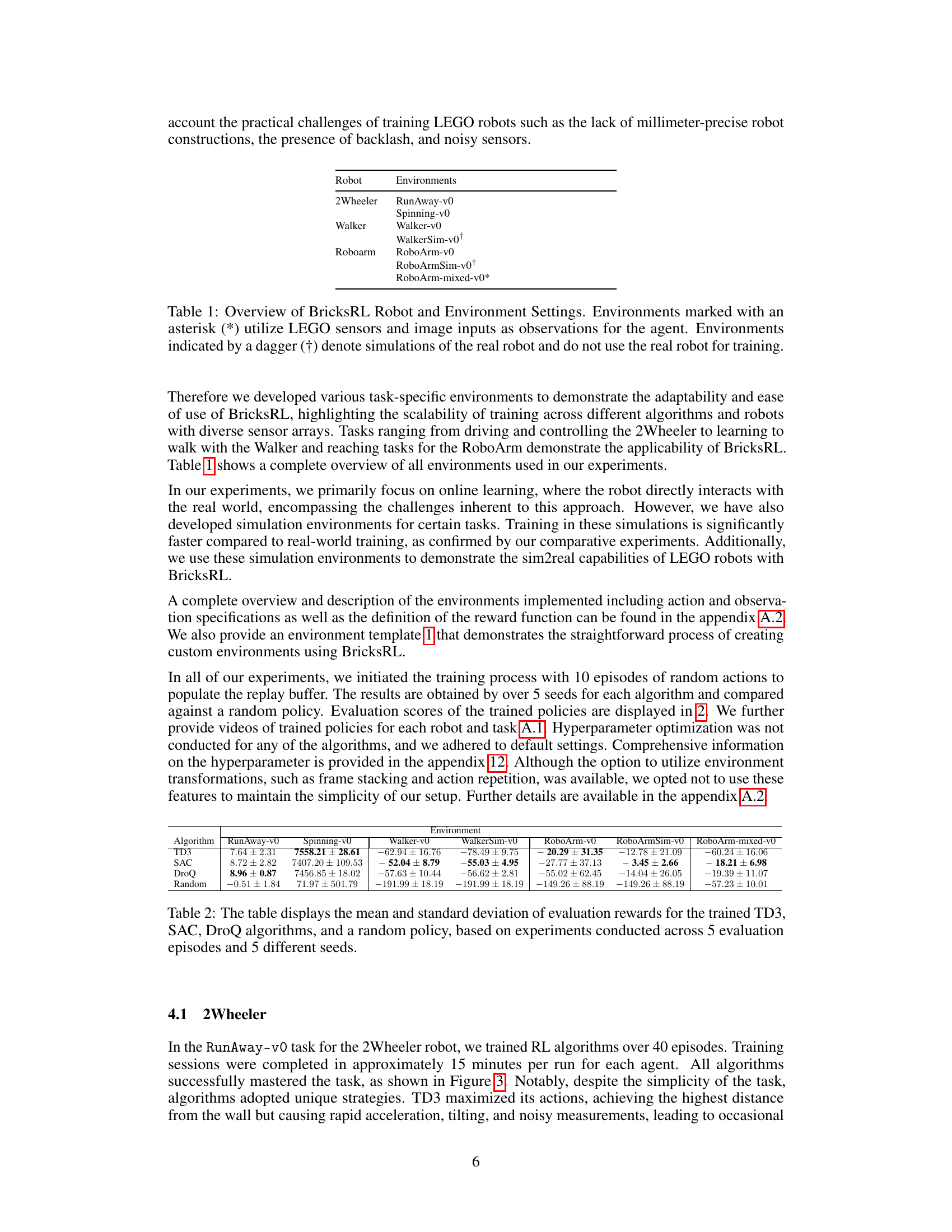

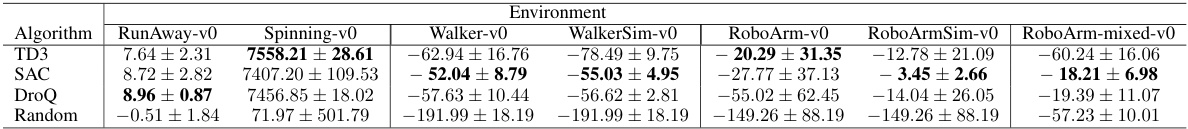

This table presents the mean and standard deviation of the evaluation rewards obtained for four different reinforcement learning algorithms (TD3, SAC, DroQ) and a random policy. The results are averaged across five evaluation episodes and five different random seeds for each algorithm. The table shows the performance of each algorithm on different robotic tasks and environments described in the paper, allowing for a comparison of their effectiveness. Note that the environments are also grouped by robot type.

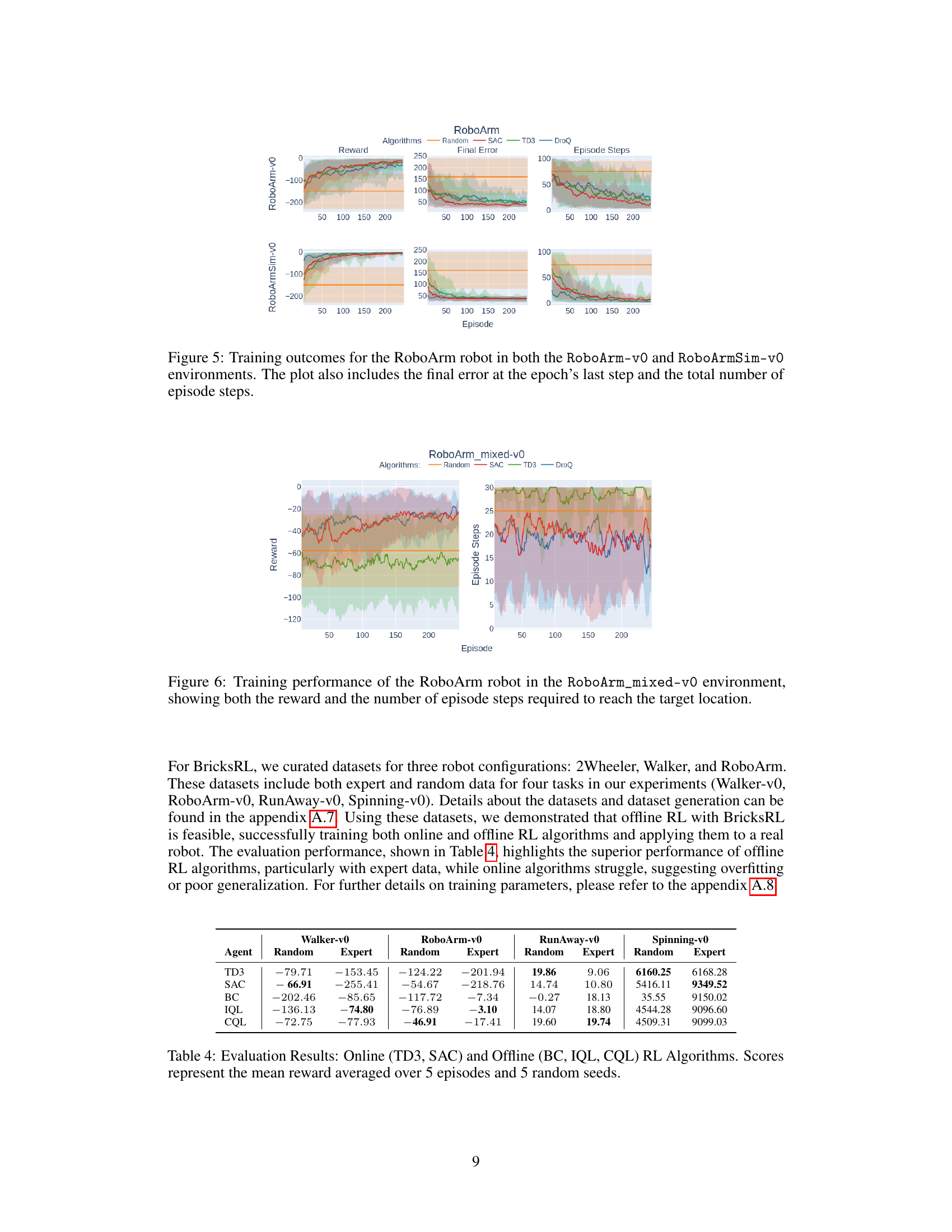

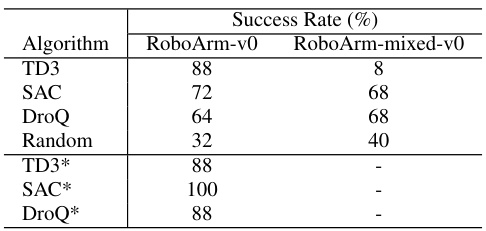

This table presents the success rates of different reinforcement learning algorithms (TD3, SAC, DroQ, and a random policy) on two RoboArm tasks: RoboArm-v0 (using only LEGO sensors) and RoboArm-mixed-v0 (incorporating a webcam). Success is measured by reaching the goal position within a time limit. The table also shows results for agents pre-trained in a simulated environment (RoboArmSim-v0), highlighting the potential of sim-to-real transfer.

This table presents the mean and standard deviation of the evaluation rewards obtained for different reinforcement learning algorithms (TD3, SAC, DroQ) and a random policy. The results are based on experiments conducted across five evaluation episodes and five different random seeds, providing a measure of the algorithms’ performance and variability.

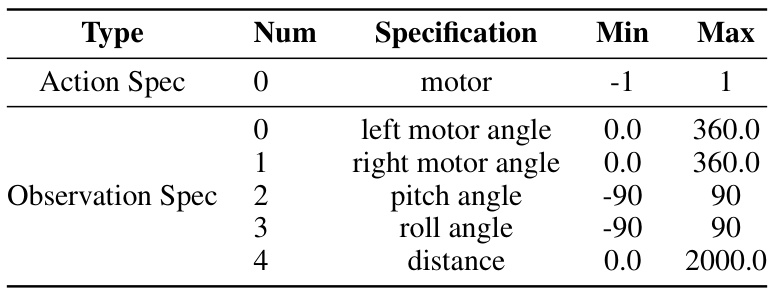

This table shows the specifications for actions and observations used in the RunAway-v0 environment. Actions consist of a single motor control value (ranging from -1 to 1), and observations consist of left and right motor angles (0.0 to 360.0 degrees), pitch angle (-90.0 to 90.0 degrees), roll angle (-90.0 to 90.0 degrees), and distance from an ultrasonic sensor (0.0 to 2000.0 mm).

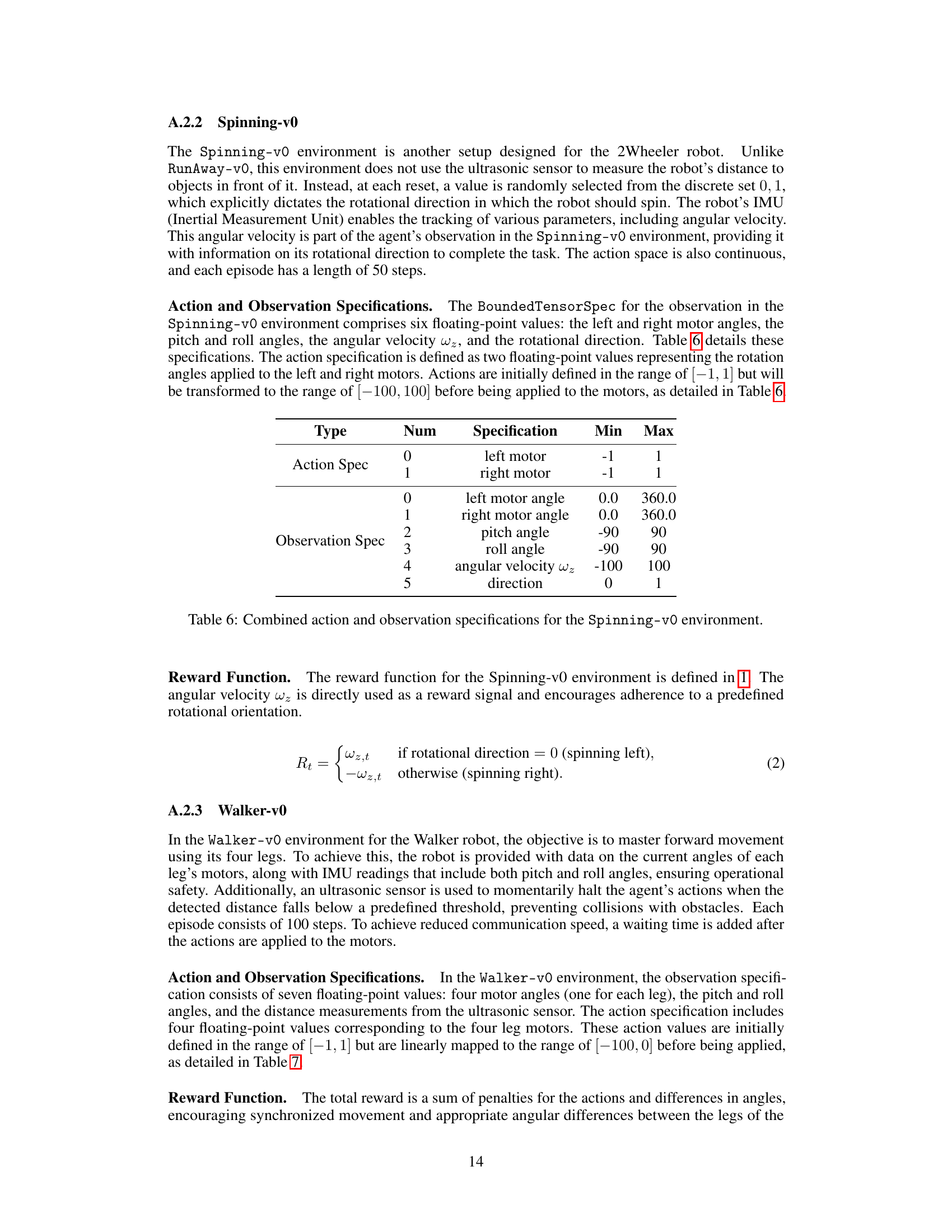

This table details the specifications for actions and observations within the Spinning-v0 environment. It shows the minimum and maximum values for each parameter, including left and right motor angles, pitch and roll angles (obtained from the robot’s IMU), angular velocity (wz), and the direction of rotation. The action space is continuous, defined by two floating-point values representing the rotation angles applied to the left and right motors. Note that the values are initially within the [-1,1] range, then transformed to [-100, 100] before being applied to the motors.

This table details the specifications for actions and observations within the Walker-v0 environment. For actions, it lists the motor controls (left front, right front, left back, right back) and their ranges. The observation section lists the motor angles, pitch, roll, and distance readings and their associated ranges. These specifications define the input and output data exchanged between the RL agent and the simulated environment during training.

This table details the specifications for actions and observations within the RoboArm-v0 environment. For actions, it lists the type of motor (rotation, low, high, grab), its numerical index, and the minimum and maximum values. For observations, it shows the motor angles (current and goal) and their corresponding ranges for each motor type.

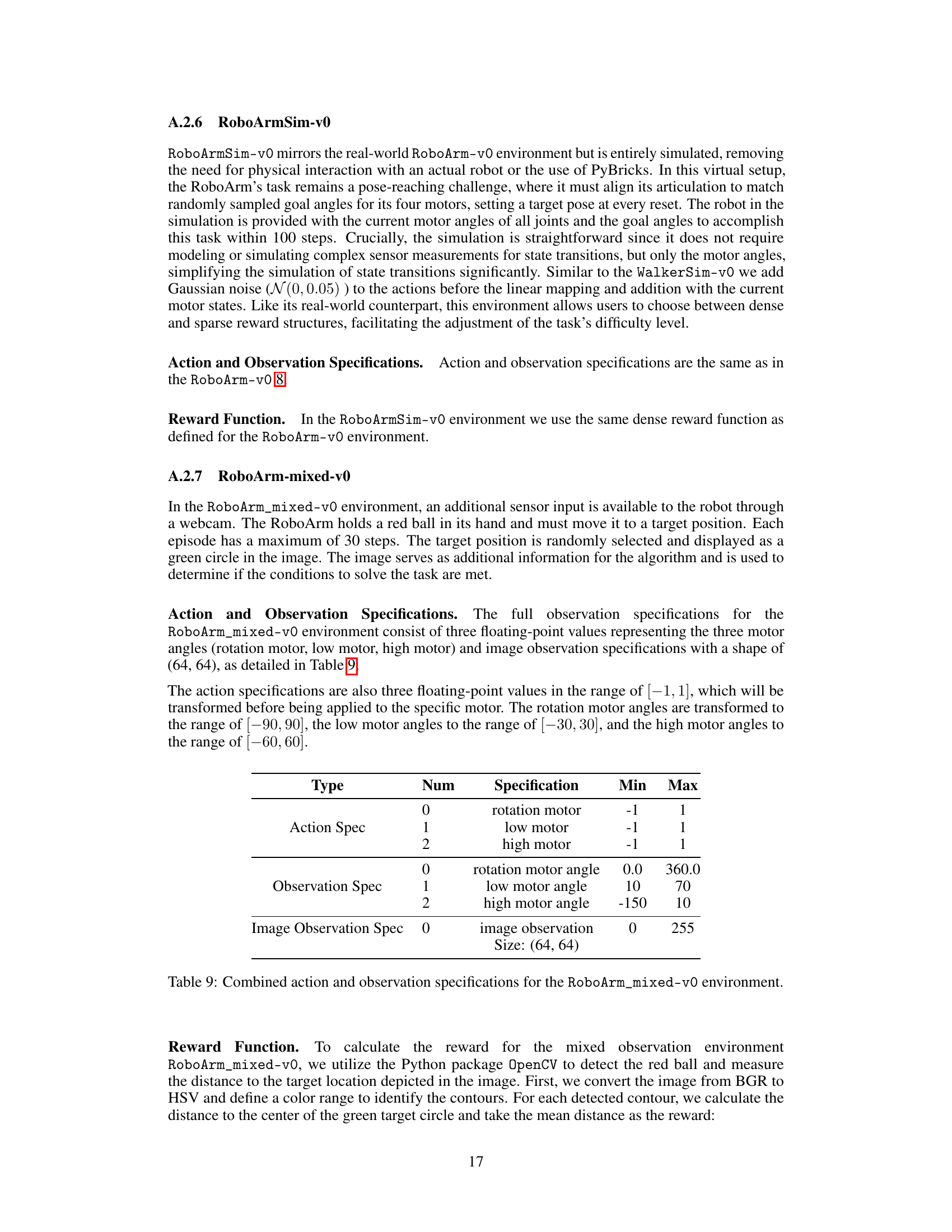

This table presents the specifications for actions and observations in the RoboArm-mixed-v0 environment. Actions consist of three continuous values controlling the rotation, low, and high motors. Observations include these three motor angles and an image observation with dimensions (64, 64). The minimum and maximum values for each specification are given.

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the three reinforcement learning agents: DroQ, SAC, and TD3. The parameters include learning rate, batch size, UTD ratio (for DroQ only), prefill episodes, number of cells in the network, gamma, soft update epsilon, alpha initial (for SAC only), whether alpha is fixed, normalization method, dropout rate, buffer size, and exploration noise (for TD3 only). These hyperparameters were used to fine-tune the model and may affect the final results of the experiment.

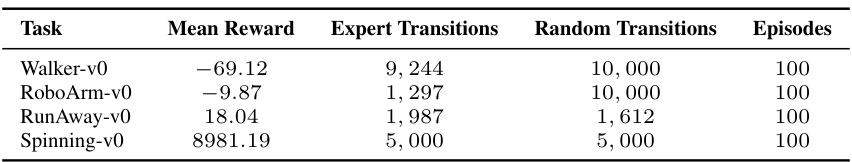

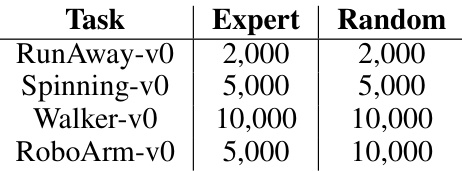

This table summarizes the statistics of the datasets used in the experiments. For each task (Walker-v0, RoboArm-v0, RunAway-v0, Spinning-v0), it shows the mean reward obtained by an expert policy, the number of expert transitions collected, the number of random transitions collected and the number of episodes used in data collection. This provides information on the quality of the datasets and the amount of data available for training reinforcement learning models.

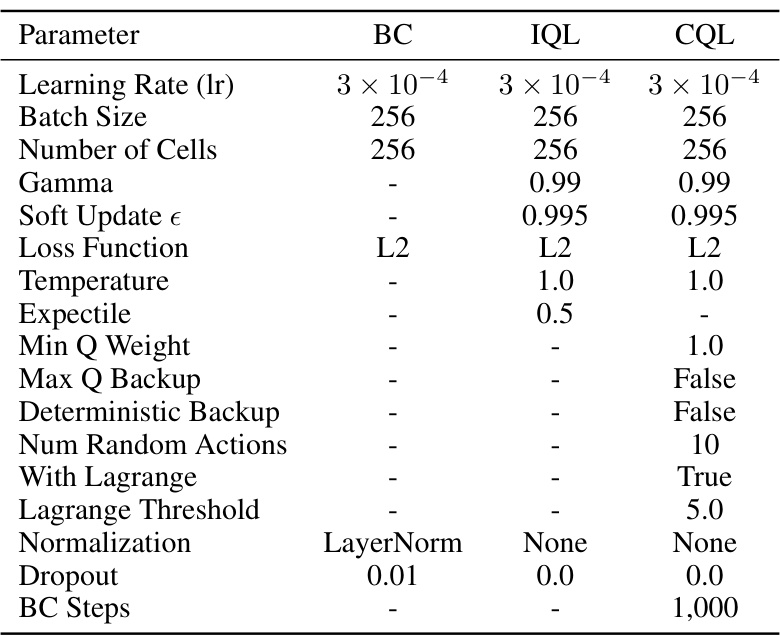

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training three offline reinforcement learning algorithms: Behavior Cloning (BC), Implicit Q-Learning (IQL), and Conservative Q-Learning (CQL). It shows the settings for parameters such as learning rate, batch size, number of cells in the network architecture, gamma (discount factor), soft update epsilon, loss function, temperature (for IQL and CQL), expectile (for IQL), minimum and maximum Q-weight, whether deterministic backup and the use of Lagrange were applied, and other regularization parameters. These hyperparameters were used to tune the performance of each algorithm during offline training.

This table shows the robots used in the experiments and their corresponding environments. It indicates whether each environment uses the actual robot or a simulation, and highlights those utilizing additional LEGO sensors (marked with *) or incorporating image data as observations. The dagger symbol (†) denotes that only a simulation of the robot was used for training in that environment.

Full paper#