↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many neural networks struggle to adapt to changing data distributions, often ‘forgetting’ previously learned information. Animals, however, seamlessly switch between tasks using internal representations. This paper addresses the challenge of creating flexible AI systems by investigating how such task abstractions might emerge in neural networks. The core problem lies in balancing the need for rapid adaptation with the preservation of previously acquired knowledge. Existing methods often fail to achieve this balance effectively.

To solve this, the researchers propose a novel ‘Neural Task Abstraction’ (NTA) model which incorporates neuron-like constraints on the units that control the weight pathways. This model uses joint gradient descent to optimize both the weights and the gates, leading to the emergence of task abstractions. The fast timescale of gate updates enables rapid adaptation, while the slower timescale of weight updates protects previously learned information. The NTA model exhibits a ‘virtuous cycle’: fast gates drive weight specialization, and specialized weights improve the rate of gate updates, leading to flexible behavior mirroring that observed in cognitive studies.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it offers a novel theory of cognitive flexibility, showing how task abstractions emerge in neural networks through a virtuous cycle of fast-adapting gates and weight specialization. This has significant implications for understanding continual learning and developing more adaptable AI systems. The analytical tractability of the linear model used makes the findings broadly applicable across fields, potentially sparking further research into the dynamics of neural networks and their relationship to cognitive processes.

Visual Insights#

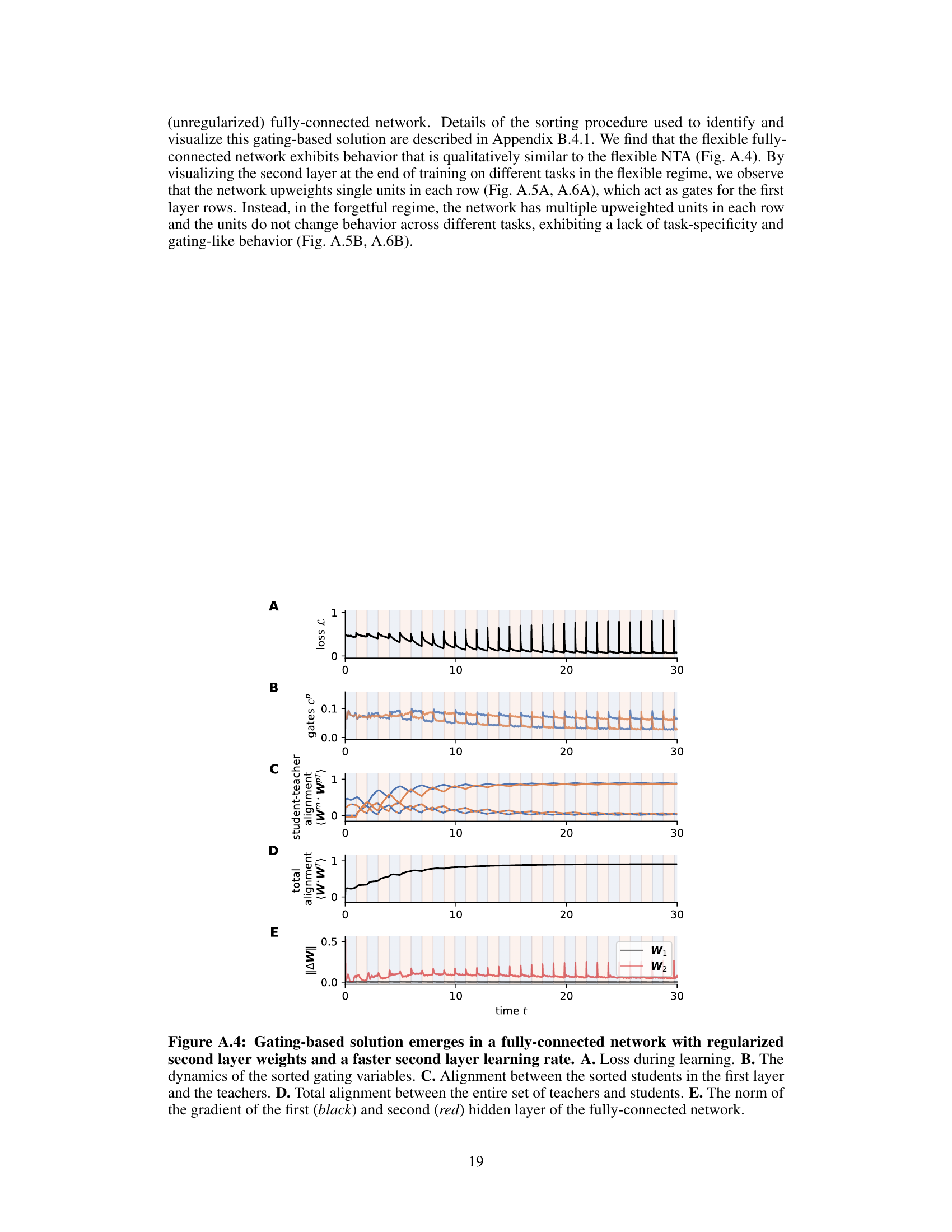

Figure 1 shows the model and learning setup used in the paper. Panel A illustrates a blocked curriculum in which two tasks are presented sequentially for some time before switching to the next task. The order of presentation is not random; it is designed to test the model’s ability to adapt flexibly to task changes over time. Panel B shows the Neural Task Abstraction (NTA) model architecture. This is a one-layer linear gated neural network. The model receives an input (x) and produces an output (y) through a weighted sum of P neural pathways, where each pathway has its own weight matrix (WP) and gating variable (CP). The gating variables control which pathways are most influential in generating the output. The model aims to learn both the optimal weights for each task and the appropriate gating strategy for switching between tasks. The focus of the paper is to show how task abstractions emerge from the joint training of weights and gates in this model.

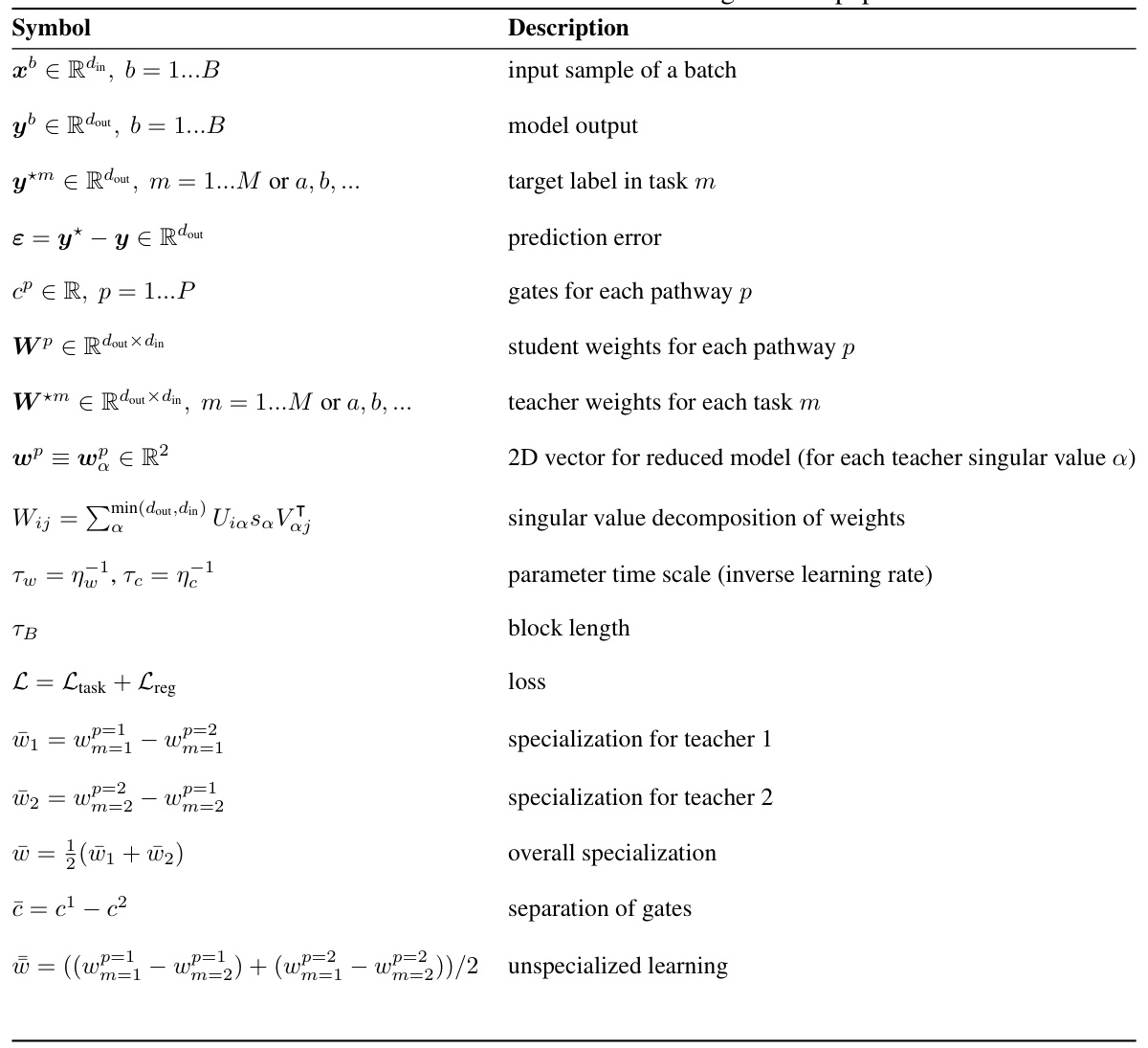

This table lists the symbols used throughout the paper, along with their descriptions. It covers various mathematical notations related to input and output data, model parameters (weights and gates), teacher and student parameters, task specialization and overall specialization, and other key variables in the analysis. The table provides a concise reference for the reader to easily understand the meaning of the symbols used within the equations and descriptions in the paper.

In-depth insights#

Flexible Task Learning#

Flexible task learning examines how neural systems adapt to dynamic environments by efficiently switching between different tasks. The key challenge is overcoming catastrophic forgetting, where learning new tasks causes the network to forget previously learned ones. This paper proposes a novel approach using a linear gated network with neuron-like constraints on its gating units. This architecture allows for fast adaptation through gradual specialization of the weight matrices into task-specific modules, protected by quickly adapting gates. The model exhibits a virtuous cycle: faster gate adaptation drives weight specialization, while specialized weights accelerate the gating layer. This leads to flexible task switching and compositional generalization, where the network effectively combines previously learned skills to solve new tasks. The model’s behavior mirrors cognitive neuroscience findings on task switching, suggesting that this framework offers a promising theory of cognitive flexibility in animals.

Linear Network Dynamics#

Analyzing linear network dynamics in the context of flexible task abstraction reveals a fascinating interplay between learning rates and weight specialization. Faster-adapting gating units drive weight specialization by protecting previously learned knowledge, creating a virtuous cycle. This specialization, in turn, accelerates the update rate of the gating layer, enabling more rapid task switching. The model’s response to curriculum changes, mirroring cognitive neuroscience observations, highlights the impact of task block length on learning efficiency and the transition between flexible and forgetful learning regimes. Joint gradient descent on synaptic weights and gating variables is crucial for this emergent cognitive flexibility. Understanding the effective dynamics within the singular value space of the teachers offers valuable insight into the mechanisms facilitating rapid adaptation and compositional generalization. The model’s linear nature allows for analytical reductions, making it tractable while retaining key characteristics of more complex systems.

Gated Weight Specialization#

Gated weight specialization, a core concept in this research, explores how neural networks adapt to dynamic environments by creating specialized modules for different tasks. Fast-adapting gating units play a crucial role by selecting the appropriate weight modules depending on the current task, enabling flexible task switching without catastrophic forgetting. This process involves a virtuous cycle: fast-adapting gates drive weight specialization, while specialized weights accelerate the gating layer’s update rate. The paper shows that the emergent task abstractions support generalization via task and subtask composition. A key finding is that this flexible learning regime contrasts with a forgetful regime where prior knowledge is overwritten with each new task. The emergence of these specialized modules and their flexible selection mechanism is a novel theory of cognitive flexibility proposing a mechanism by which animals and humans might respond flexibly to changes in their environment.

Compositional Generalization#

Compositional generalization, the ability of a system to generalize to novel combinations of previously learned components, is a crucial aspect of intelligent behavior. The research paper explores this concept within the context of neural networks, focusing on how flexible task abstractions emerge. The key finding is that the joint optimization of weights and gates in a linear network, under specific constraints, leads to the self-organization of weight modules specialized for individual tasks or sub-tasks. These modules act as building blocks for complex tasks. Furthermore, a gating layer learns unique representations that selectively activate the appropriate weight modules, thus enabling flexible task switching and adaptation. This architecture facilitates not only task-level generalization, where the network adapts to unseen tasks composed of familiar sub-tasks, but also sub-task-level generalization. In sub-task composition, novel tasks are created by combining parts of previously encountered tasks, and the network successfully generalizes. This demonstrates that the network’s learned task abstractions are compositional, supporting the emergence of intelligent behavior in dynamic environments.

Nonlinear Network Extension#

Extending the findings from linear networks to nonlinear networks is a crucial step in validating the theory’s broader applicability. The success of this extension hinges on demonstrating that the emergence of task abstractions and flexible gating isn’t solely a consequence of the linear network structure. A successful nonlinear extension would likely involve a careful consideration of how the nonlinearities interact with the gradient descent optimization and the dynamics of the gating layer. The authors might explore different nonlinear activation functions, analyzing how they affect weight specialization and the ability of the gating layer to effectively switch between task representations. Furthermore, demonstrating successful generalization to novel tasks or subtasks in the nonlinear setting is vital, showcasing that the learned task abstractions are robust and transferrable beyond the linear regime. Comparative analysis between the linear and nonlinear model’s performance in terms of generalization, speed of adaptation, and robustness to noisy or incomplete data would strengthen the paper’s conclusions.

More visual insights#

More on figures

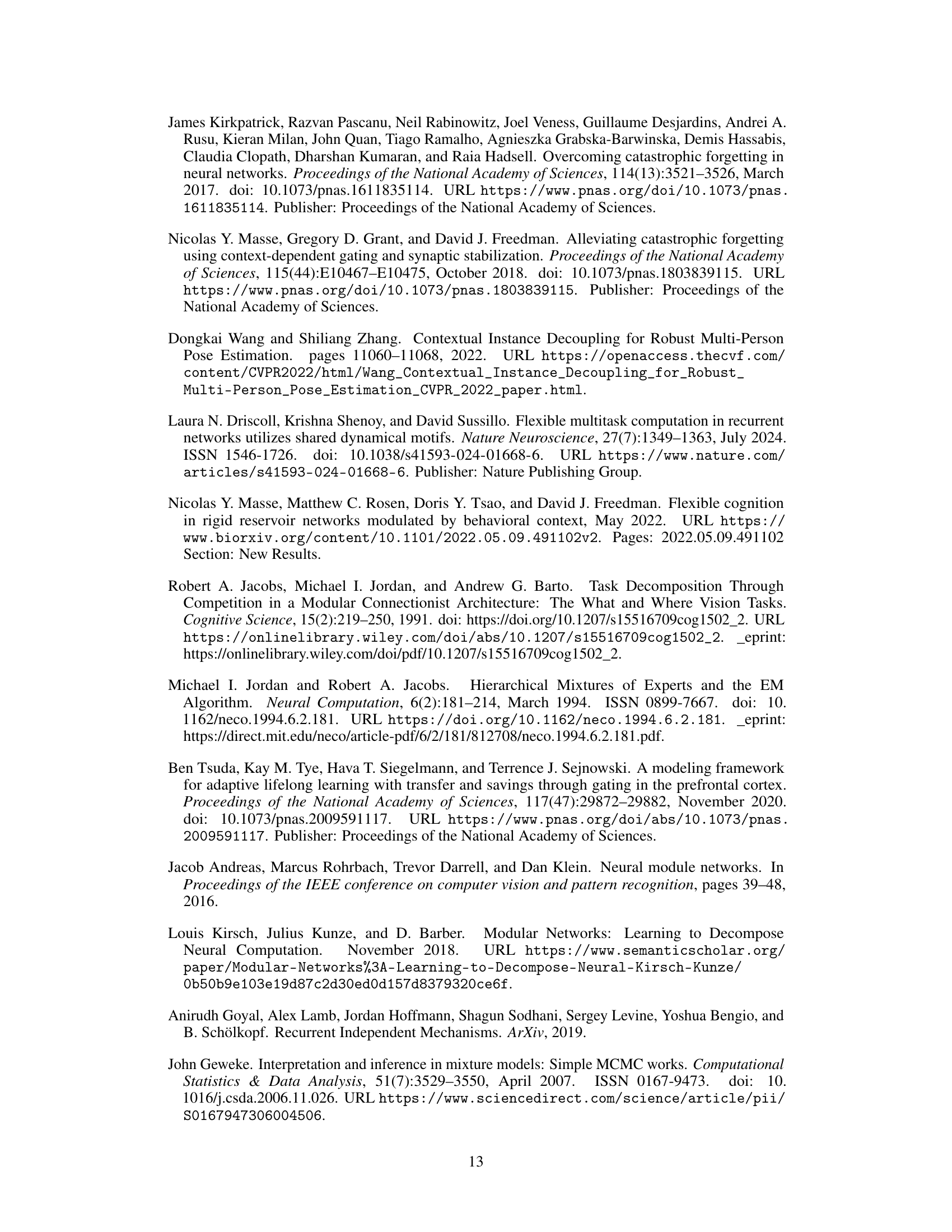

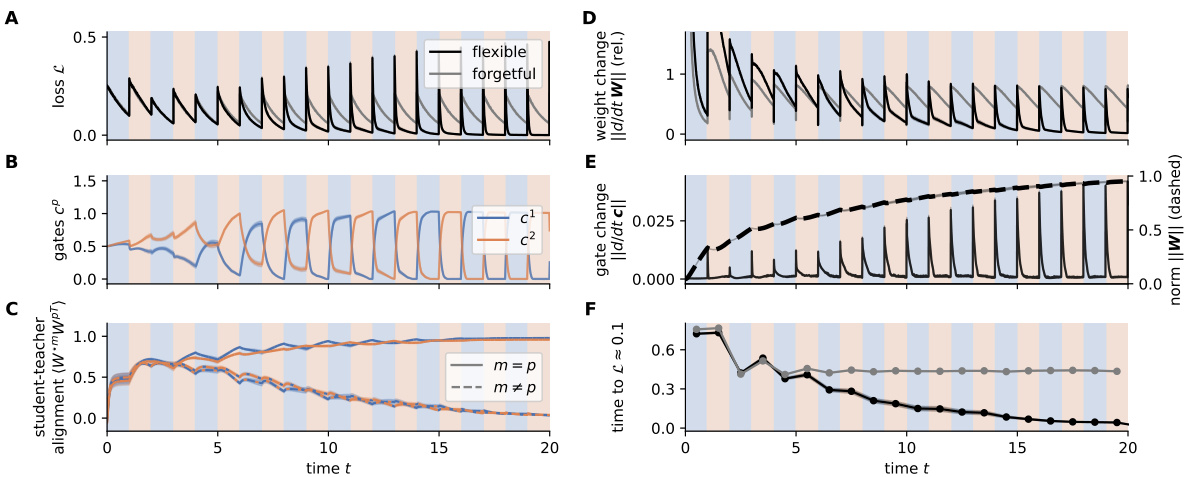

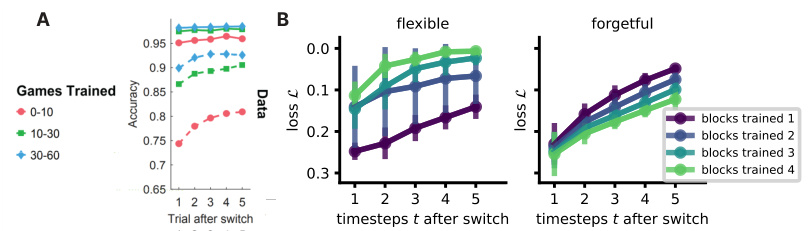

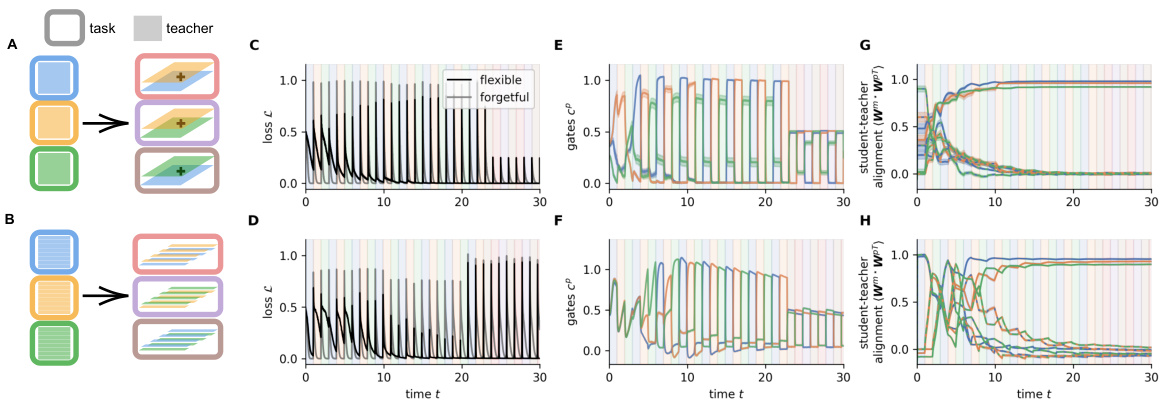

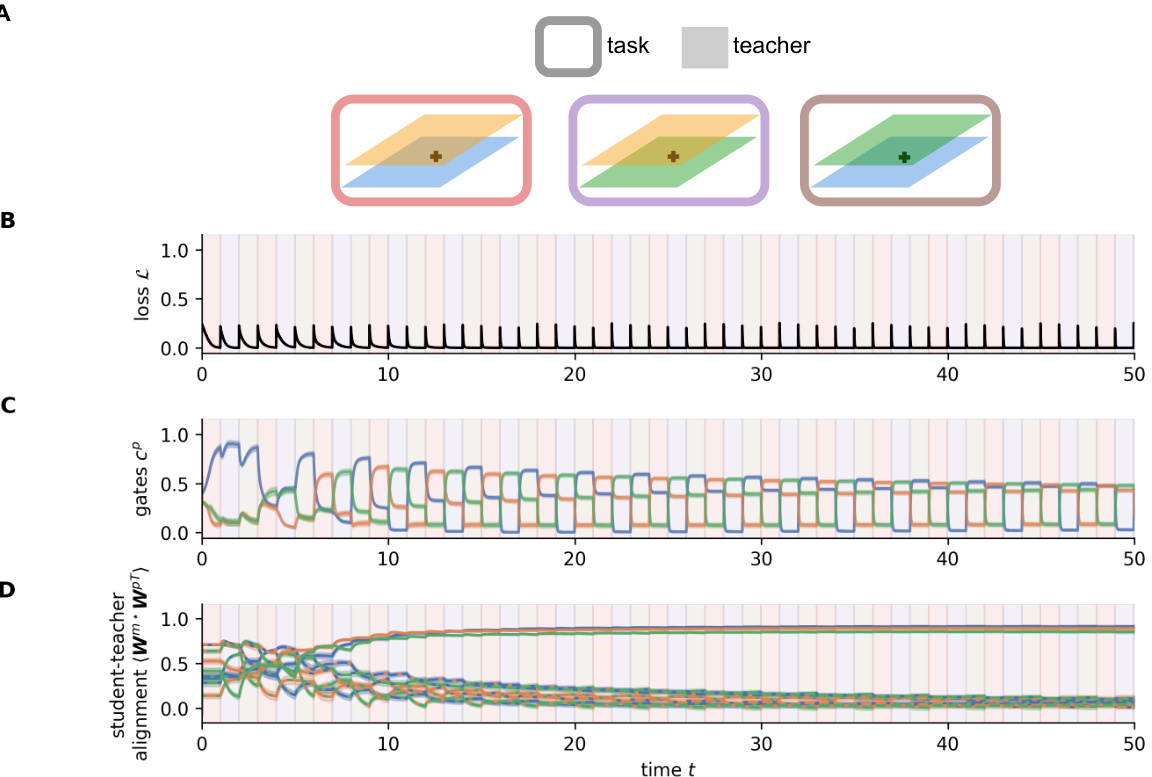

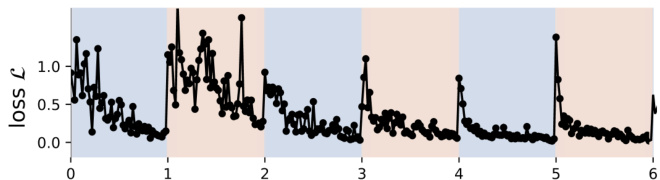

This figure shows the results of a simulation comparing two models: a flexible NTA model and a forgetful NTA model. Both models were trained on a blocked curriculum with two alternating tasks. The flexible NTA model shows a rapid decrease in loss and faster task adaptation compared to the forgetful model. The figure also displays the gate activity, weight alignment, update norms, and time to reach a loss of 0.1 for both models across multiple training blocks, demonstrating the benefits of the flexible gating mechanism.

This figure demonstrates the model’s ability to generalize to new tasks that are compositions of previously learned tasks. Panel A shows task composition, where new tasks are created by summing the weight matrices of previously learned tasks. Panel B shows subtask composition, where new tasks are created by concatenating rows from previously learned tasks. Panels C and D show the loss curves for both the flexible and forgetful models on these new compositional tasks. The flexible model (black line) shows significantly faster learning on the new tasks than the forgetful model (gray line), highlighting the advantage of task abstraction in compositional generalization.

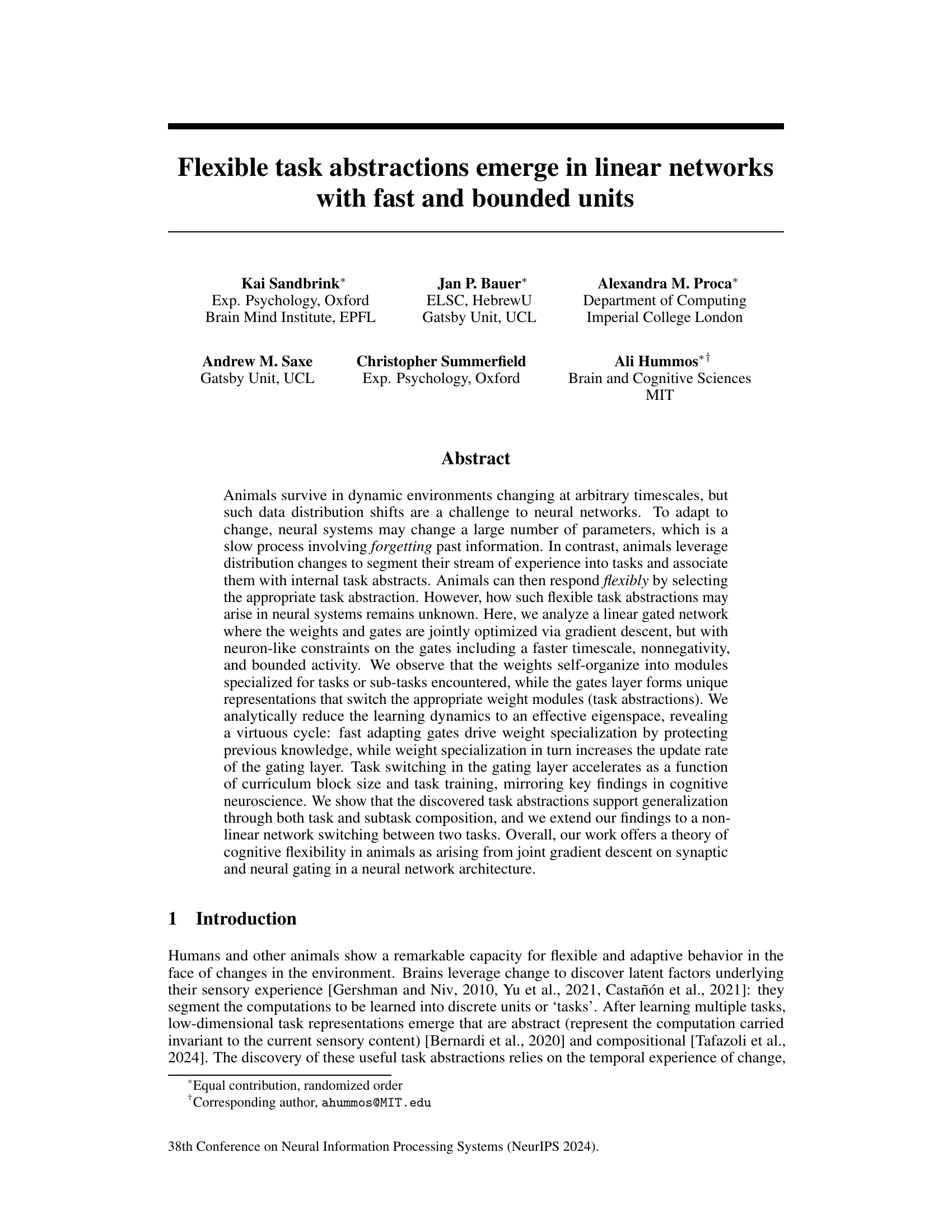

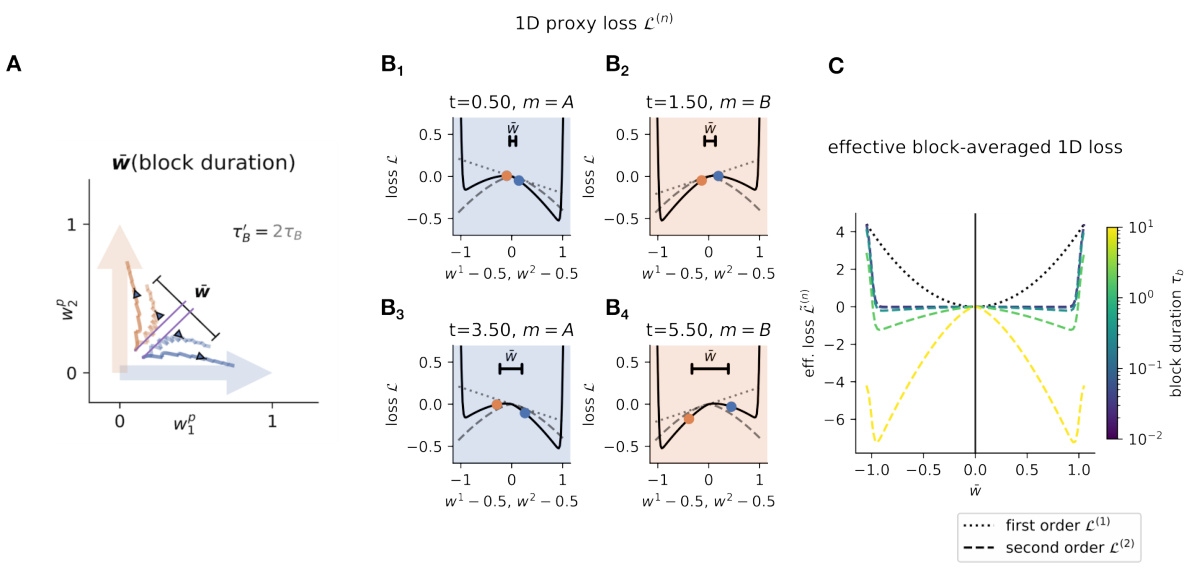

This figure describes the mechanism of gradual task specialization in a simplified 2D subspace of the model. It shows how student weight matrices and gates interact to achieve fast adaptation in the flexible learning regime, contrasting it with the forgetful regime. The figure also illustrates the self-reinforcing feedback loops between weight specialization and gate updates, showing how faster adapting gates drive weight specialization and vice-versa. Finally, it validates the model’s dynamics using both simulations and analytical predictions.

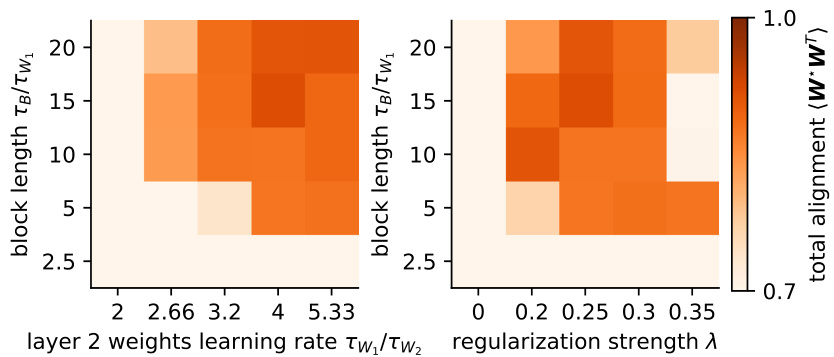

This figure shows the results of grid searches on the hyperparameters of the model to determine the conditions under which specialization emerges. The hyperparameters varied are block length, gate learning rate, and regularization strength. The colorbar represents the total alignment (cosine similarity) between the teachers and students, acting as a measure of specialization. The results illustrate that a longer block length, faster gate learning rate, and sufficient regularization strength all contribute to the emergence of a specialized, flexible learning regime in the model.

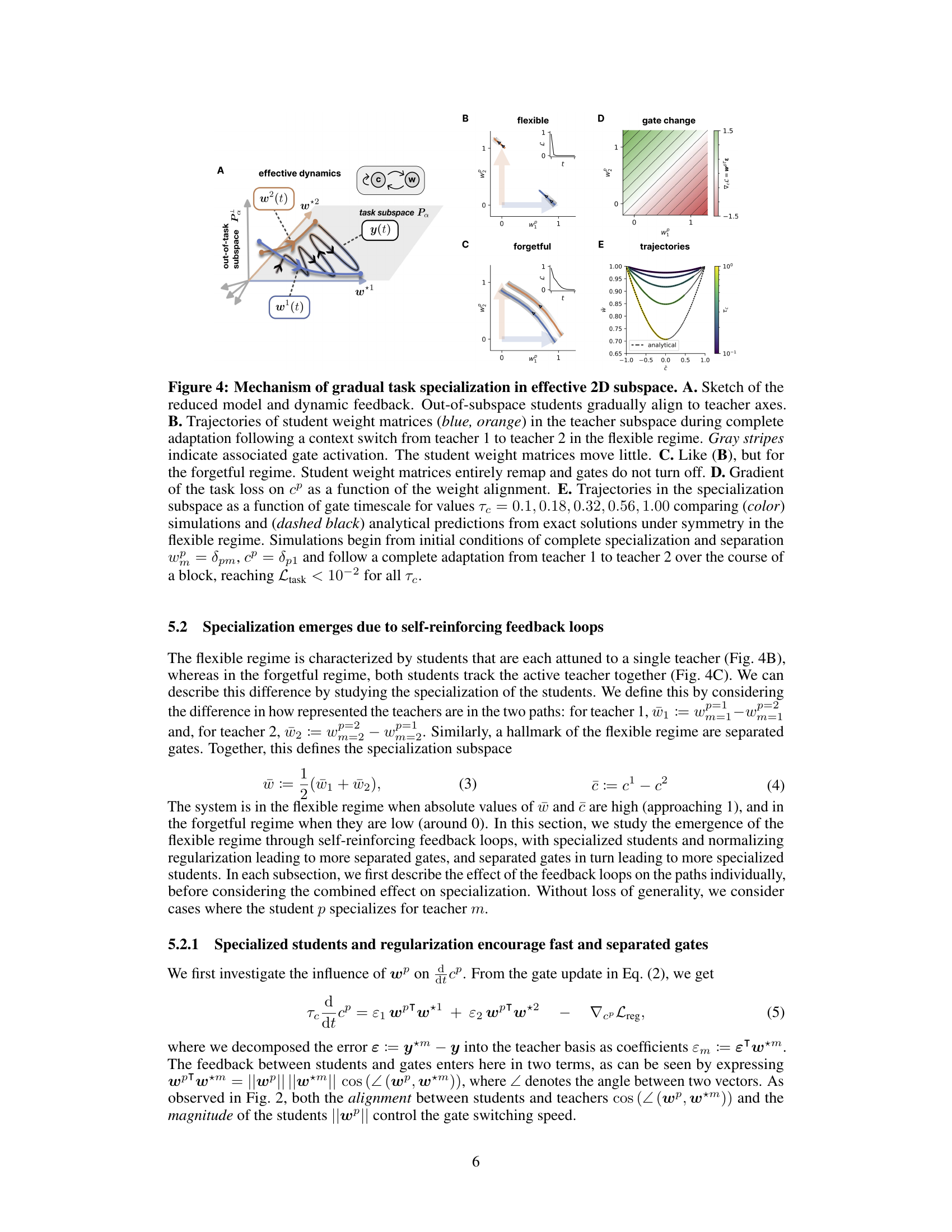

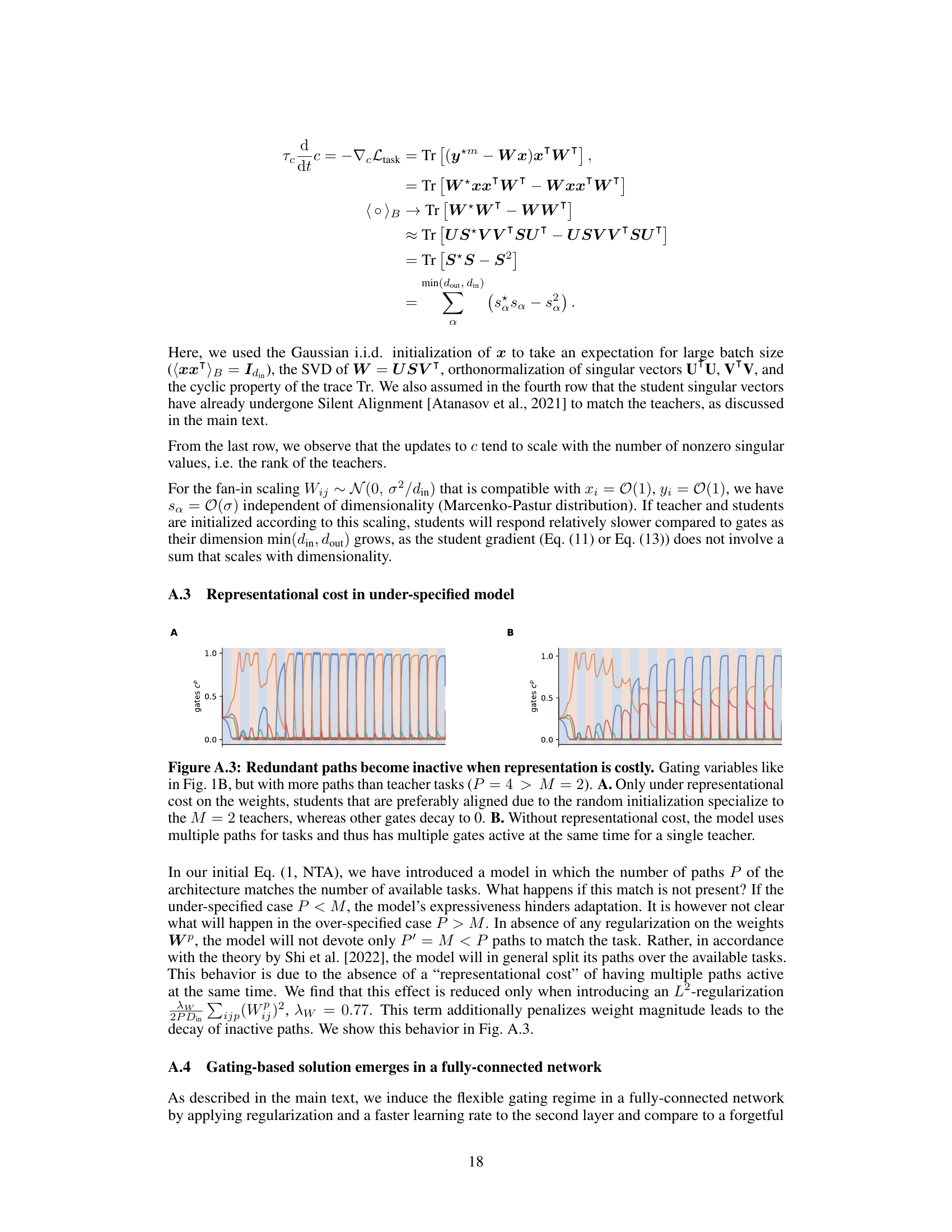

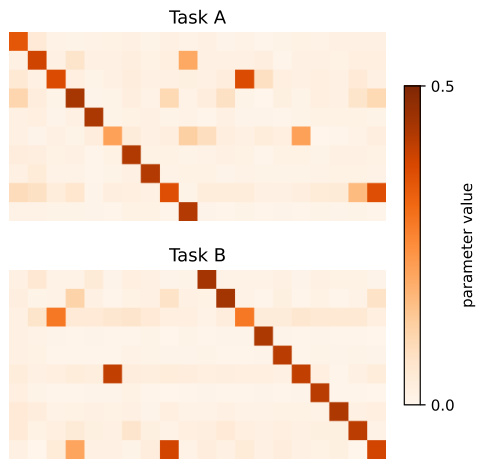

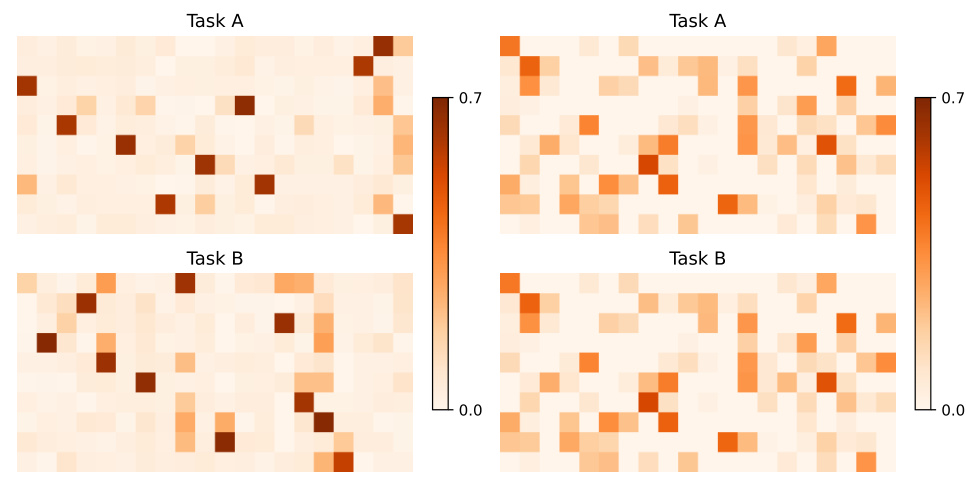

This figure shows the weights of the second layer of a two-layer fully connected network after training on two different tasks. The weights are sorted to show how they are specialized for different tasks (Task A and Task B). The diagonal shows the gating behavior, where the weights are strongly activated for one task and less so for the other. This demonstrates how fast learning rates and regularization on the second layer leads to the formation of task-specific gating.

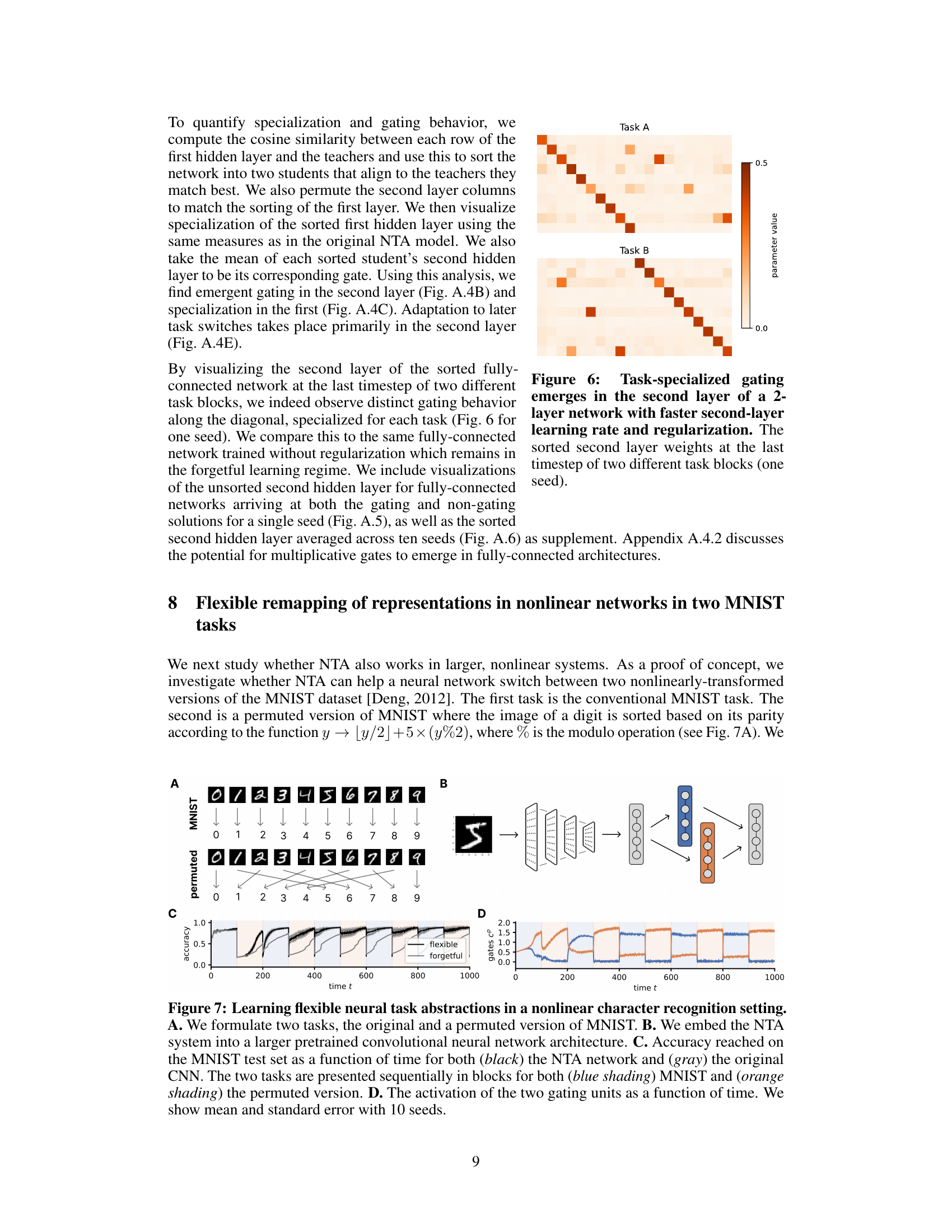

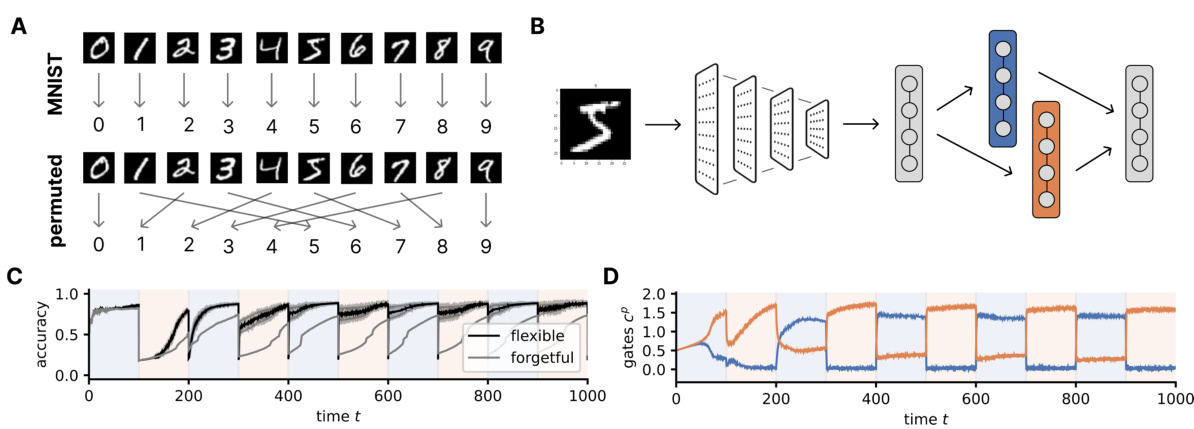

This figure demonstrates the application of the Neural Task Abstraction (NTA) model to a non-linear classification problem using the MNIST dataset. Panel A shows the two tasks: standard MNIST digit recognition and a permuted version where digits are reordered based on parity. Panel B illustrates the model architecture, showing how the NTA module is integrated into a pre-trained convolutional neural network (CNN). Panel C presents the accuracy results for both the NTA-enhanced CNN and a standard CNN over time, highlighting the faster adaptation of the NTA model to task switches. Panel D displays the activation patterns of the gating units in the NTA module, revealing how they selectively activate for each task.

This figure compares the performance of humans and two different NTA models (flexible and forgetful) on a task-switching experiment. Panel A shows human data from a previous study, illustrating faster task switching with more practice. Panel B contrasts the two NTA models, demonstrating that the flexible model shows faster task switching with more training blocks while the forgetful model shows the opposite trend. Error bars represent standard error across 10 simulations.

This figure compares the dynamics of the full model and the reduced 2D model. The results show that the reduced model accurately captures the essential dynamics of the full model, as measured by the loss function, gate activation patterns, and singular value magnitudes. This validates the use of the simplified 2D model for theoretical analysis in the paper.

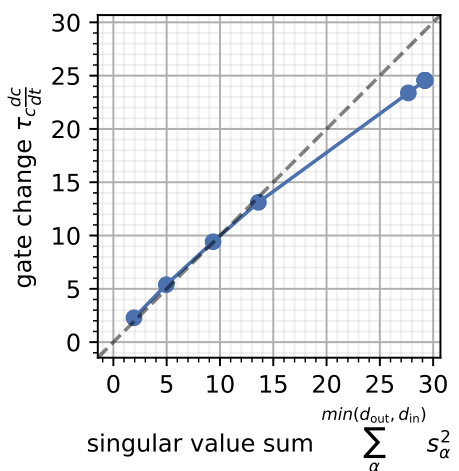

This figure shows the relationship between the speed at which gates change (vertical axis) and the dimensionality of the teacher (horizontal axis). It demonstrates that high-dimensional students (those with many singular values) learn slower than low-dimensional students. This is because high-dimensional students have more parameters to adjust during learning, making it slower to adapt their parameters when new information or tasks are introduced.

This figure compares the dynamics of a full linear gated neural network with its reduced 2D equivalent model. The comparison demonstrates that the reduced model accurately reflects the full model’s behavior in terms of loss function, gate activation patterns, and the magnitude of singular values. This validates the use of the simpler 2D model for analytical purposes, as it captures the essential dynamics of the more complex full model.

This figure shows that the flexible gated model generalizes to compositional tasks. In task composition, new tasks are created by summing previously learned tasks (teachers). In subtask composition, new tasks are formed by combining rows from different teachers. The figure demonstrates that the flexible model is able to adapt quickly to both task and subtask composition, showing low loss, appropriate gating activation, and strong student-teacher alignment.

This figure displays the results of a simulation comparing two models, a flexible NTA model and a forgetful NTA model. It demonstrates how joint gradient descent on gates and weights leads to fast adaptation through gradual specialization in the flexible model. Multiple subplots show the loss over time, gate activity, student-teacher weight alignment, norm of updates, and time to reach a specific loss threshold, highlighting the differences between the two models and showcasing the flexible model’s ability to adapt quickly to changing tasks.

This figure visualizes the unsorted second hidden layer of a fully-connected network after training on two tasks. The left panel shows a regularized network exhibiting specialization with single neurons in each row acting as gates, each specific to one task. In contrast, the right panel shows a non-regularized network lacking this specificity and thus exhibiting a lack of task-specific gating.

This figure shows the weight matrices of a fully connected network trained with (left) and without (right) regularization. The flexible network shows clear specialization of single neurons as gates for each task, while the forgetful network does not show this specificity. This demonstrates that regularization is crucial for the emergence of task-specific gating in a fully connected network.

This figure shows the results of a grid search over different hyperparameters: block length, gate learning rate (inverse of gate timescale), and regularization strength. The heatmaps show the total alignment (cosine similarity) between the weights of all students and teachers after training. Higher alignment indicates greater specialization of the network’s weights towards the different tasks. The figure helps illustrate the conditions under which the network enters the ‘flexible’ learning regime, characterized by rapid adaptation to task switches and preserved knowledge.

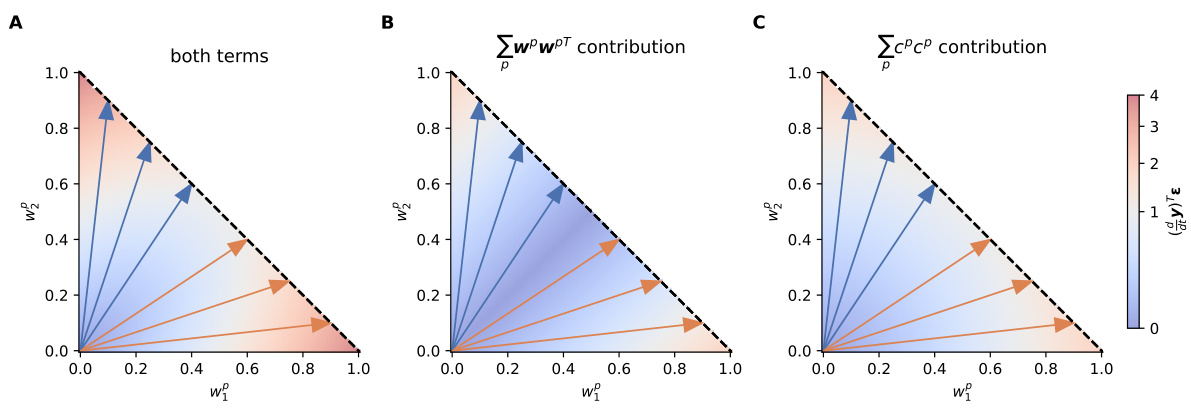

This figure shows the contribution of different terms of the Neural Tangent Kernel (NTK) to the adaptation speed. The NTK is used to analyze how the model output changes in response to a task switch. The figure shows that the adaptation is accelerated by two factors: student-teacher alignment and selective gating. The dashed lines show the possible solutions.

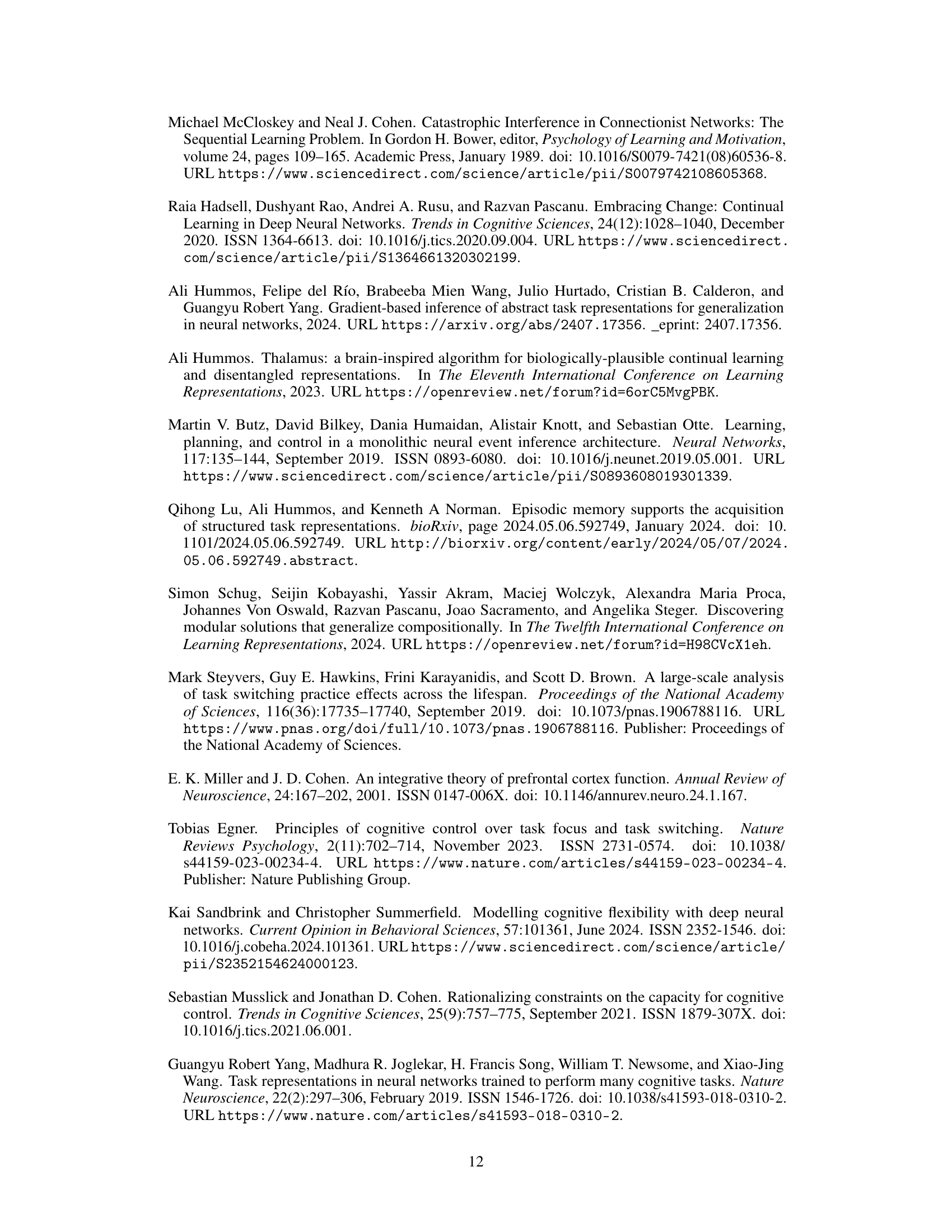

This figure shows how longer training blocks lead to faster specialization in a neural network model. Panel A illustrates how longer blocks allow students (weight matrices) to move further toward specialization before a task switch reverses their progress. Panels B and C demonstrate the effect on loss and specialization (respectively) using a simplified 1D model with first-order and second-order terms in the loss function. The first-order term (due to linear gradient descent) is shown to be insufficient for specialization, while the second-order term leads to a non-linear, double-well loss landscape that promotes stable specialization. Longer blocks allow sufficient time for the students to descend toward a specialized state within this landscape.

This figure analyzes how the Neural Tangent Kernel (NTK) contributes to the accelerated adaptation observed in the flexible regime. It decomposes the NTK into contributions from specialized weights (wPwPT) and selective gates (CPCP). Heatmaps illustrate how these contributions vary with different degrees of student specialization, showing that the combination of both factors leads to faster adaptation.

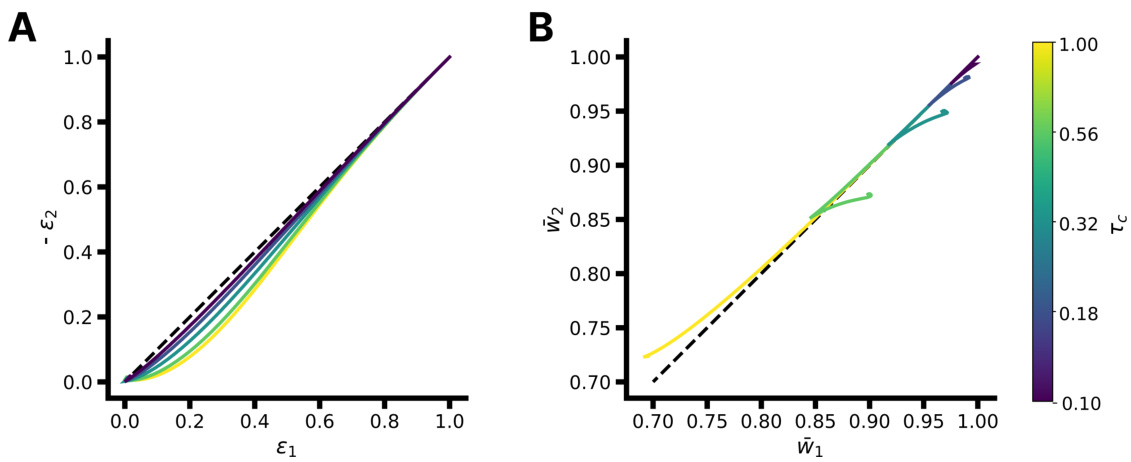

This figure shows the learning dynamics of the model’s parameters when a task switch occurs. Panel A and B shows how the error in the specialization subspace changes over time for different values of the gate timescale (Tc). Panel C shows how the weight matrices adapt in the specialization subspace, while panel D shows the orthogonal component of learning. Finally, panel E shows how the gate change varies over time in the specialization subspace. Overall, the figure illustrates that learning happens both inside and outside of the specialization subspace, and that gate timescale plays an important role in the adaptation speed.

This figure shows that a gated neural network model can generalize to new tasks formed by combining previously learned tasks (compositional generalization). The top row illustrates task composition, where new tasks are created by summing the weights of previously learned tasks. The bottom row shows subtask composition, where new tasks are created by combining rows from previously learned tasks. The model’s performance (loss), gate activation, and student-teacher alignment are shown for both task composition and subtask composition, demonstrating the model’s ability to leverage previously learned representations for new tasks.

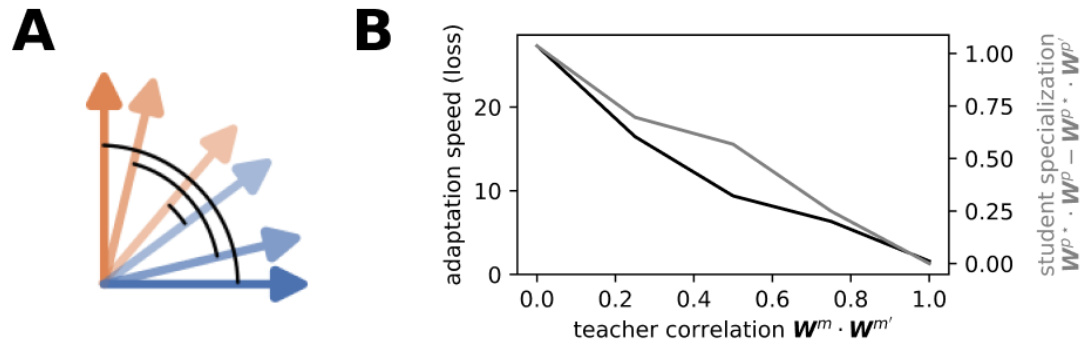

This figure demonstrates the robustness of the model’s flexible learning regime to deviations from the assumption of orthogonality between tasks. Panel A illustrates how the cosine similarity between teachers changes as the angle between their vectors varies. Panel B shows how the adaptation speed (measured by the loss after a task switch) and the degree of student specialization vary as a function of teacher correlation. It is observed that as teachers become less orthogonal (correlation approaches 1), both the adaptation speed and specialization decrease, indicating a graceful degradation from the idealized orthogonal case.

This figure demonstrates the model’s ability to generalize to compositional tasks. Panel A shows task composition, where new tasks are created by summing previously learned teacher tasks. Panel B shows subtask composition, where new tasks are created by concatenating rows from different teachers. The figure displays loss, gating activity, and student-teacher alignment to illustrate how the model handles these novel compositions. Results show that the flexible model quickly adapts to compositional tasks, while the forgetful model struggles.

This figure shows the results of applying the Neural Task Abstraction (NTA) model to the FashionMNIST dataset. Two different task orderings were used: one orthogonal (upper-to-lower clothing items) and one non-orthogonal (warm-to-cold weather clothing items). The top panels show the accuracy on the test set for both the flexible and forgetful NTA models over time. The bottom panels show the activity of the gating units over time. Error bars representing the mean and standard error across 10 different seeds are included. The results demonstrate that the flexible NTA model adapts more quickly to task switches in both scenarios, highlighting its adaptability and robustness across different task structures.

This figure compares the performance of two NTA models (flexible and forgetful) during a task-switching experiment. The flexible model uses a faster timescale for gates than weights. The figure displays the loss over time, gate activity, student-teacher weight alignment, norm of updates to weights and gates, and time to reach a specific loss threshold. The flexible model shows faster adaptation and weight specialization compared to the forgetful model.

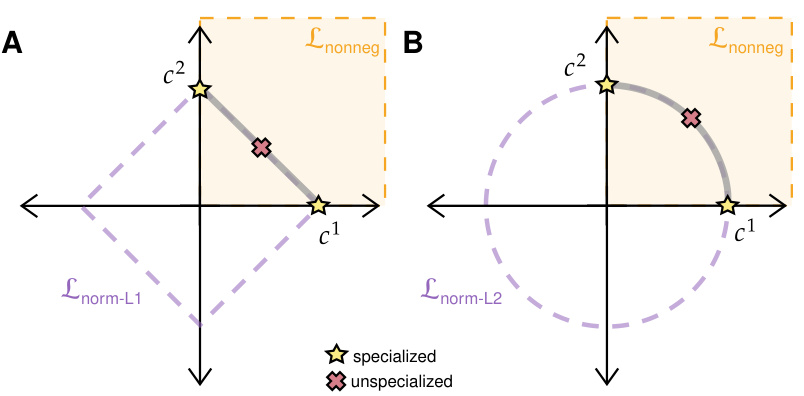

This figure illustrates how different regularization methods affect the gating variables in the model. The Lnorm-L1 regularization (left panel) encourages sparsity in the gating variables, while the Lnorm-L2 regularization (right panel) allows for multiple gates to be active. The key point is that neither regularization method forces specialization; there are solutions that involve both gates being active at similar levels. However, regularization makes the solutions with one gate significantly dominant much more likely.

More on tables

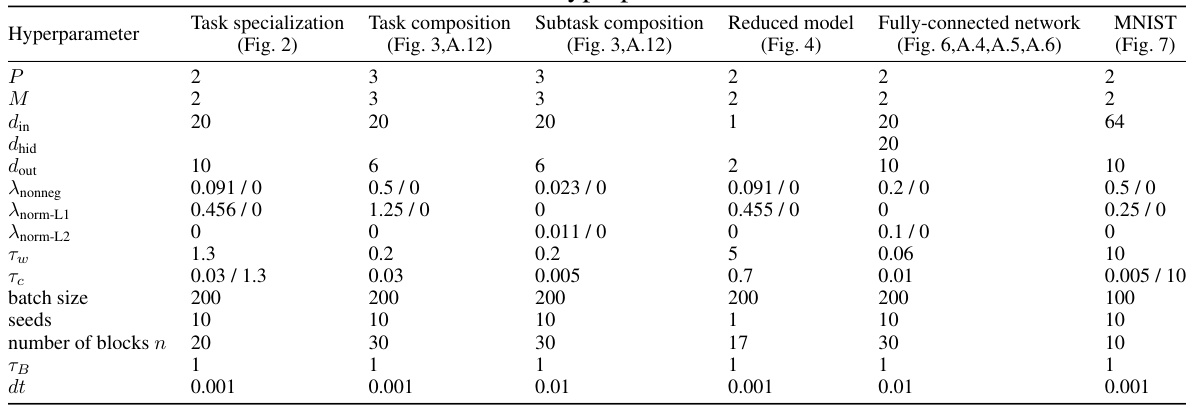

This table lists the hyperparameters used in the different experiments of the paper. It shows the values for parameters such as the number of paths (P), number of tasks (M), input dimension (din), hidden dimension (dhid), output dimension (dout), regularization coefficients (Anonneg, Anorm-L1, Anorm-L2), timescales for weight and gate updates (Tw, Tc), batch size, number of seeds, number of blocks, block length (TB), and timestep size (dt). The values are presented for the main experiments shown in Figures 2, 3, and 4, as well as the fully-connected network experiments in Figures 6, A.4, A.5, and A.6 and the MNIST experiments in Figure 7. Note that some parameters have multiple values separated by a slash, indicating a different setting used for the experiment.

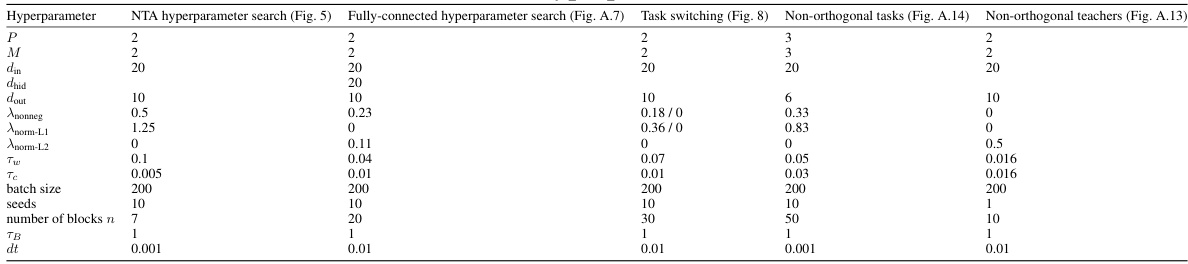

This table lists the hyperparameters used in the different experiments described in the paper. It shows the values used for the number of paths (P), number of tasks (M), input dimension (din), hidden dimension (dhid), output dimension (dout), the regularization parameters (Anonneg, Anorm-L1, Anorm-L2), the time constants for weights and gates (Tw, Tc), batch size, number of seeds, number of blocks (n), block length (TB), and time step (dt). Different sets of hyperparameters were used for the different experiments; this table details those choices.

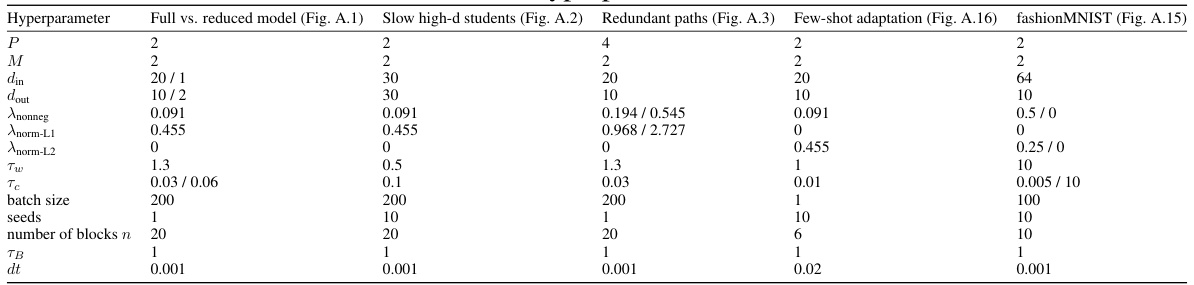

This table lists the hyperparameters used in several experiments presented in Appendix A. These experiments include comparing the dynamics of the full model with a reduced model, examining how high-dimensional student models learn slower, exploring what happens with redundant paths in the network, analyzing few-shot adaptation, and investigating performance on the fashionMNIST dataset. Each row specifies a different experimental setting and shows the values of hyperparameters such as P (number of paths), M (number of distinct tasks), din (input dimension), dout (output dimension), Anonneg (coefficient for non-negativity term), Anorm-L1 (coefficient for L1 normalization term), Anorm-L2 (coefficient for L2 normalization term), Tw (weight time constant), Tc (gate time constant), batch size, number of seeds used, number of blocks, block length (TB), and time step (dt). The table provides detailed parameters for each of the experiments, allowing readers to reproduce the results.

Full paper#