↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs), the third generation of neural networks, offer potential for low-energy, high-performance AI. However, their performance lags behind Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs). Spiking Transformers aim to bridge this gap, but their quadratic complexity hinders scalability. Existing spiking transformers have limited success on benchmark datasets like ImageNet.

This research introduces QKFormer, a novel spiking transformer that addresses the limitations of its predecessors. QKFormer utilizes a novel Q-K attention mechanism with linear complexity and high energy efficiency, improving training speed and allowing larger model development. The authors also employ a hierarchical architecture with multi-scale spiking representation. Experimental results demonstrate that QKFormer achieves state-of-the-art performance on various datasets, significantly outperforming existing methods, notably exceeding 85% accuracy on ImageNet-1K. This breakthrough highlights the potential of directly training SNNs for large-scale applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in neuromorphic computing and AI. It presents QKFormer, a novel, high-performance spiking transformer that significantly advances the state-of-the-art in direct training SNNs. The linear complexity and energy efficiency of its attention mechanism open exciting avenues for developing advanced AI models with superior performance and lower energy consumption. Its success on ImageNet-1K underscores the potential of SNNs for real-world applications.

Visual Insights#

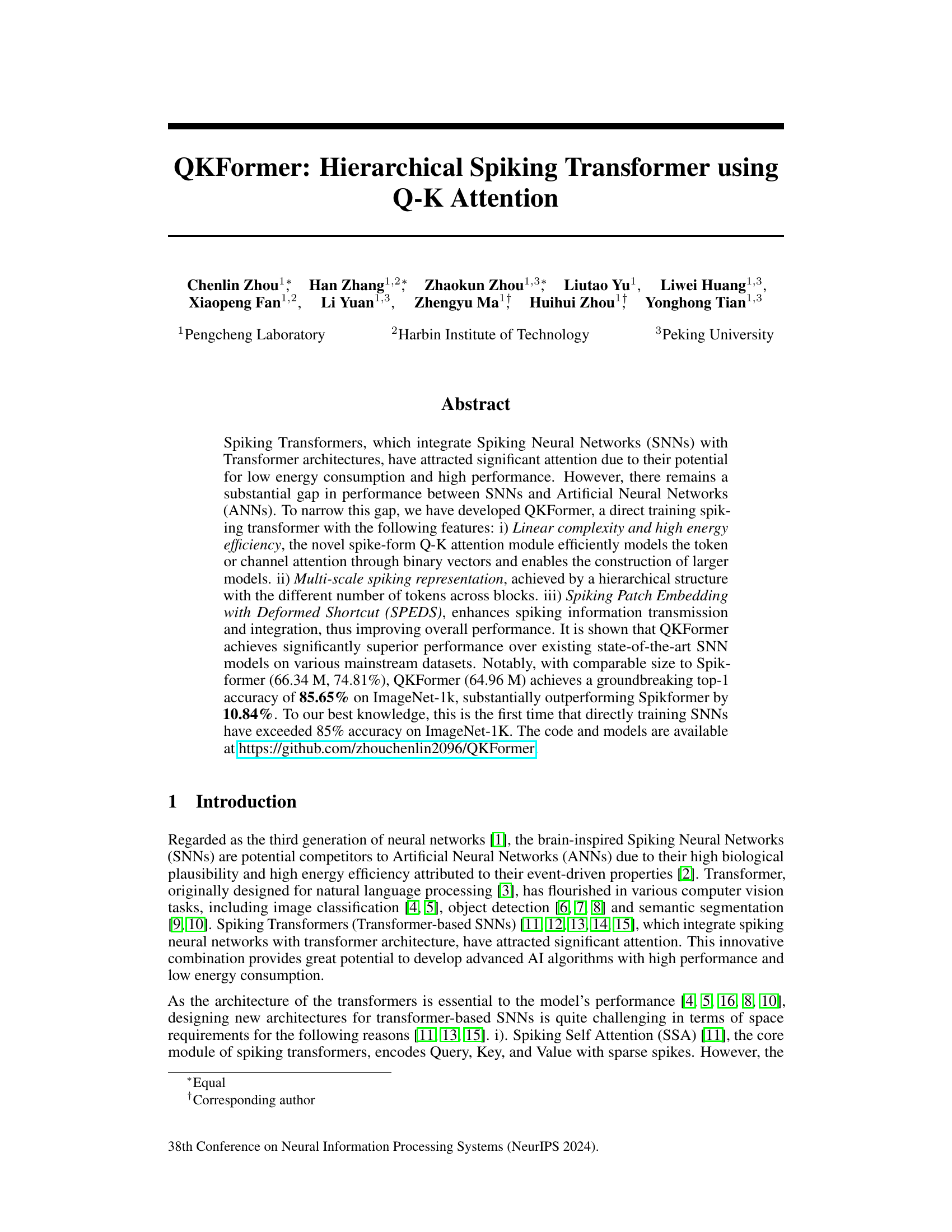

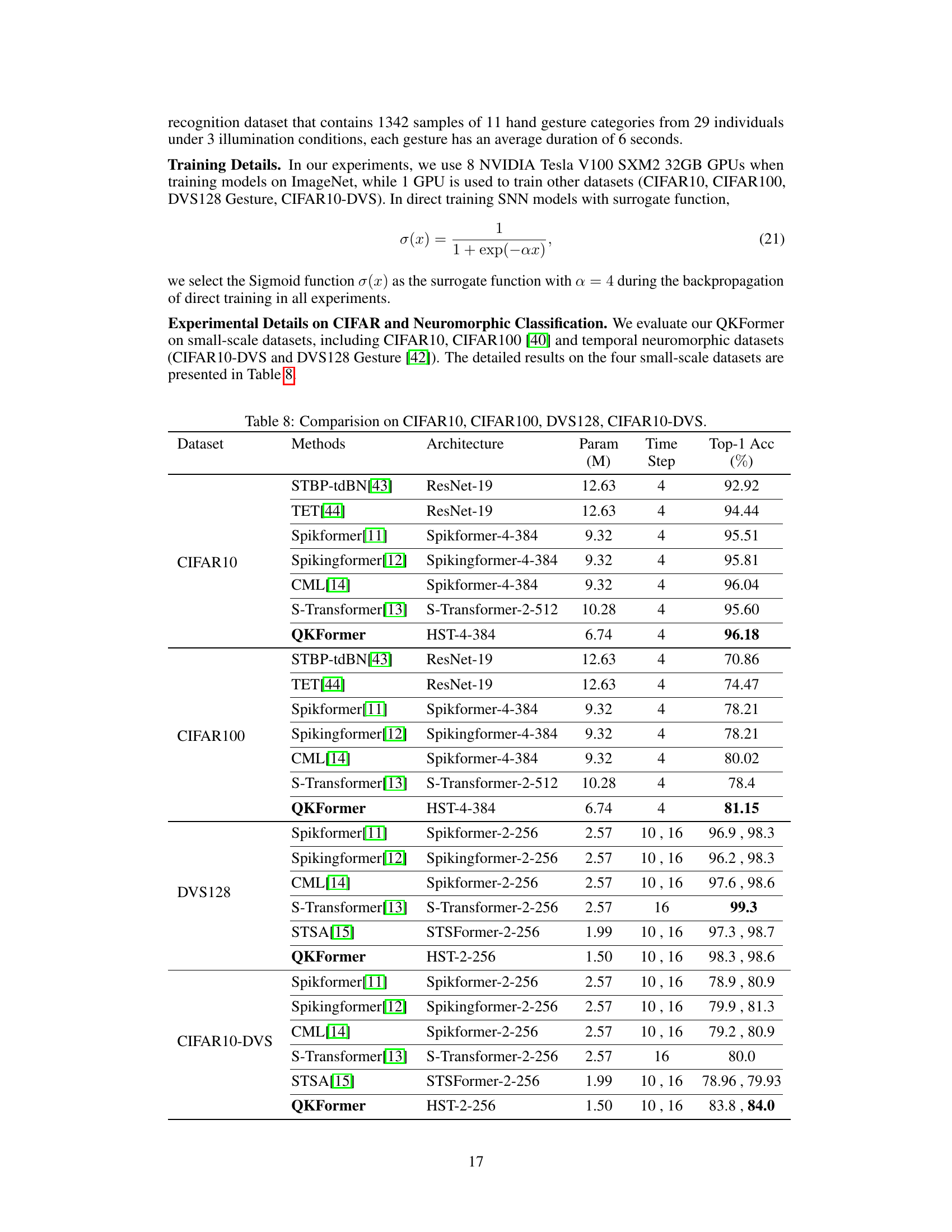

This figure illustrates the Q-K attention mechanism, a core component of the QKFormer model. It shows two versions: Q-K token attention (QKTA) and Q-K channel attention (QKCA). Both versions use binary spike inputs and perform sparse additions and masking operations to model token or channel attention efficiently. The figure highlights the linear complexity and energy efficiency achieved by using spike-form binary vectors. The Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) neuron model is used.

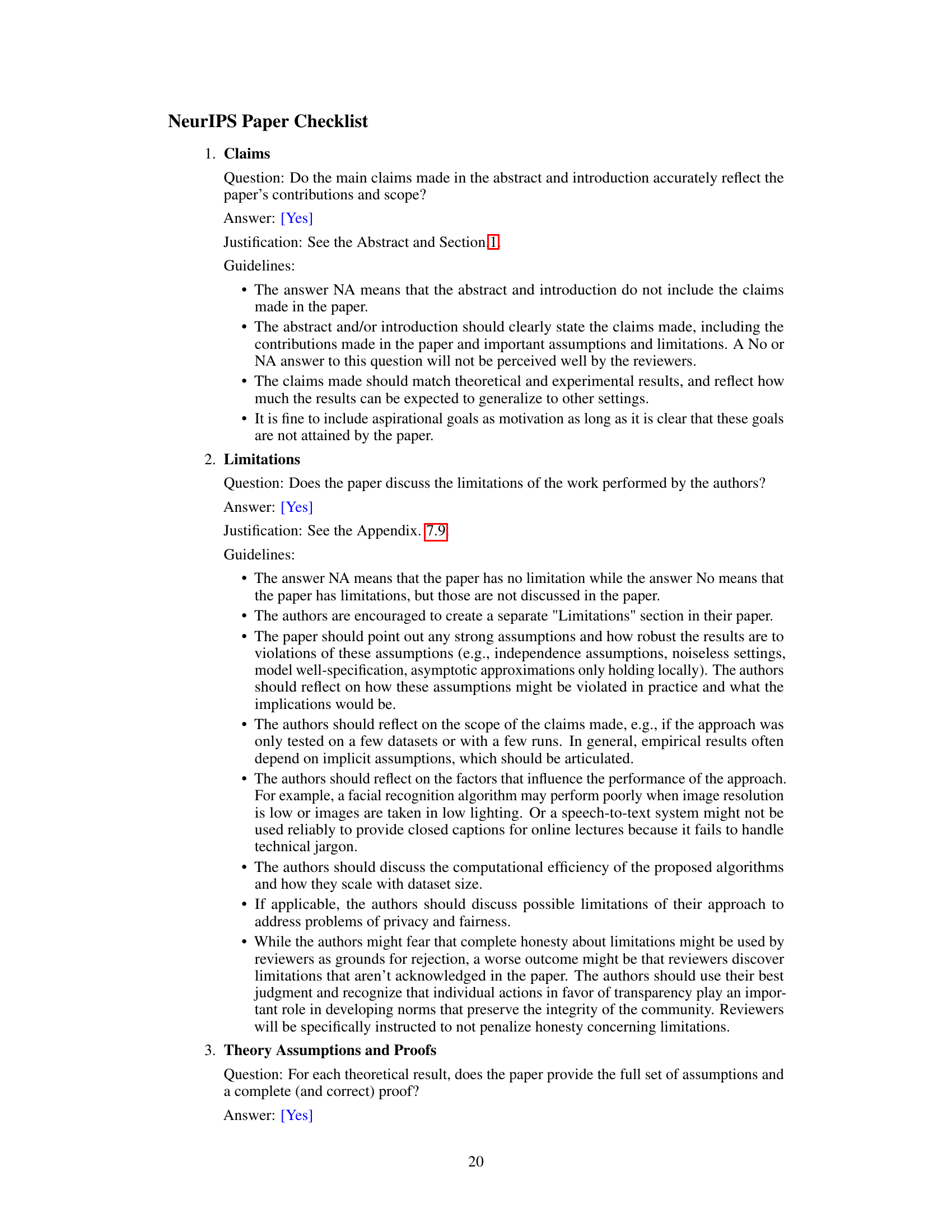

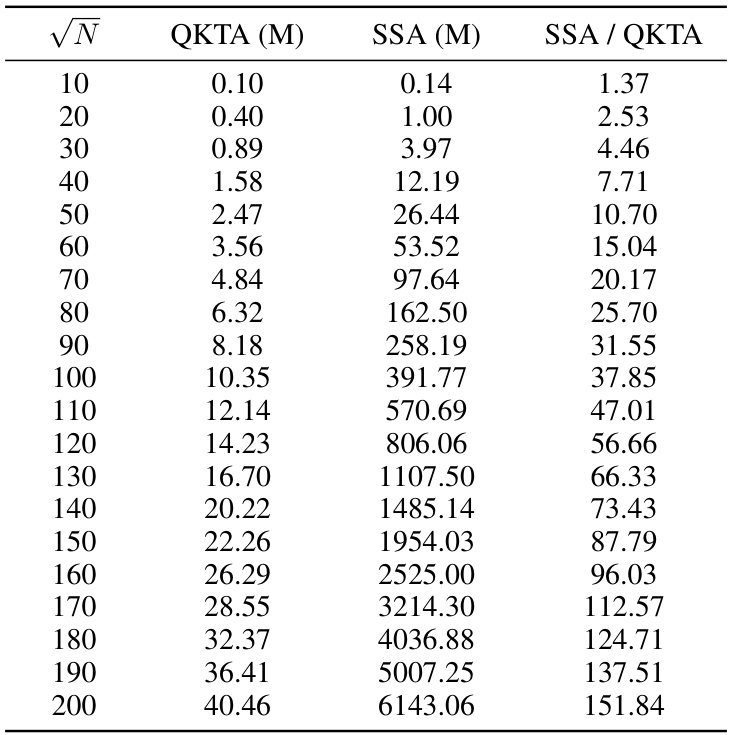

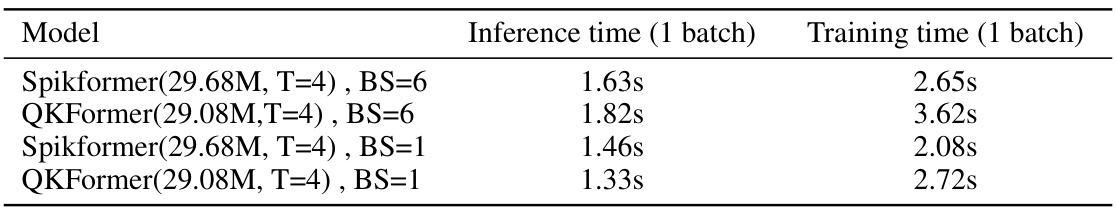

This table compares the time and space complexity of different self-attention mechanisms: Vanilla Self-Attention (VSA), Spiking Self-Attention (SSA), Spike-Driven Self-Attention (SDSA), Q-K Token Attention (QKTA), and Q-K Channel Attention (QKCA). The complexity is expressed in Big O notation, showing how it scales with the number of tokens (N) and the number of channels (D). It highlights the linear complexity of QKTA and QKCA compared to the quadratic complexity of VSA and SSA, indicating their potential for greater efficiency in larger models.

In-depth insights#

Spiking Transformer#

Spiking neural networks (SNNs), the third generation of neural networks, offer event-driven computation, promising low energy consumption. Integrating SNNs with the powerful Transformer architecture creates Spiking Transformers, aiming to leverage the strengths of both. A key challenge lies in efficiently implementing self-attention mechanisms within the SNN framework, as traditional methods often involve computationally expensive operations incompatible with SNNs’ sparse and event-driven nature. This necessitates novel attention designs that utilize spike-based computation and minimize floating-point operations. Spiking Transformers hold great potential for energy-efficient AI, but successful implementations require carefully addressing the trade-off between biological plausibility and computational efficiency. Significant research is focused on developing novel self-attention mechanisms tailored for SNNs and exploring efficient training methods for these hybrid architectures.

Q-K Attention#

The proposed Q-K attention mechanism offers a novel approach to self-attention in spiking neural networks (SNNs). Its core innovation lies in using only two spike-form components, Query (Q) and Key (K), unlike traditional methods that utilize three. This simplification drastically reduces computational complexity, achieving a linear time complexity compared to the quadratic complexity of existing methods. The binary nature of the spike-form vectors further enhances energy efficiency. This linear complexity is crucial for scaling up SNN models, enabling the construction of significantly larger networks and paving the way for processing more intricate and high-dimensional data. The design is specifically tailored for the spatio-temporal characteristics of SNNs, efficiently capturing relationships between tokens or channels. This efficient attention mechanism plays a pivotal role in the overall performance and scalability of the QKFormer architecture.

Hierarchical Design#

A hierarchical design in deep learning models, especially within the context of spiking neural networks (SNNs), offers significant advantages. It allows for multi-scale feature representation, processing information at different levels of abstraction simultaneously. This is crucial for handling complex data like images, where low-level features (edges, textures) build upon each other to form high-level semantic interpretations (objects, scenes). Computational efficiency is another key benefit; a hierarchy can reduce redundancy and unnecessary computations by progressively decreasing the number of tokens or channels as processing moves up the hierarchy. This is particularly important for SNNs, where computational cost is a major concern. Finally, a hierarchical structure can improve performance and robustness by allowing for efficient integration and transmission of spiking information across layers, facilitating better learning and generalization capabilities.

ImageNet Results#

An ImageNet analysis would deeply explore the model’s performance on this benchmark dataset, comparing it against state-of-the-art (SOTA) models. Key aspects to consider include top-1 and top-5 accuracy, examining whether the model surpasses previous SOTA results and by what margin. The analysis should also consider the number of parameters and computational efficiency, determining if superior accuracy comes at the cost of increased resource usage, which is crucial for evaluating the model’s practicality. Furthermore, a discussion on the training time and energy consumption will be highly relevant. Finally, error analysis on different image categories or subsets may reveal strengths and weaknesses and highlight future research directions.

Future SNNs#

Future SNN research should prioritize bridging the performance gap with ANNs by focusing on more efficient training methods, addressing the limitations of backpropagation in spiking networks, and developing novel architectures. Hierarchical structures and mixed attention mechanisms show promise. Furthermore, exploring new, more biologically plausible neuron models and synaptic plasticity rules, coupled with improved methods for efficient hardware implementation, are crucial. Research into novel learning paradigms beyond backpropagation is also needed. The development of scalable and energy-efficient SNNs suitable for real-world applications requires interdisciplinary collaboration to tackle challenges in both algorithm design and hardware acceleration. Ultimately, successful SNNs will balance biological realism with computational efficiency.

More visual insights#

More on figures

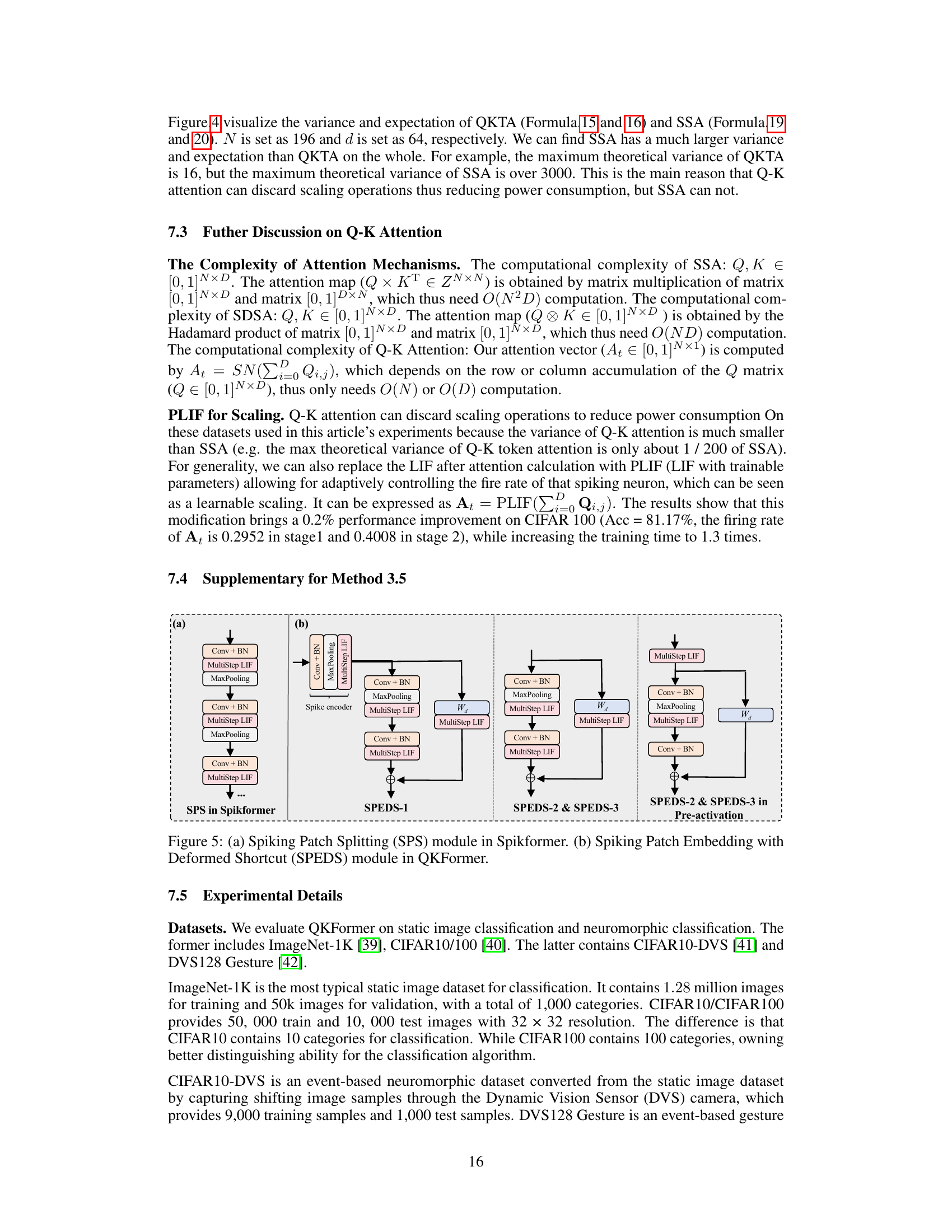

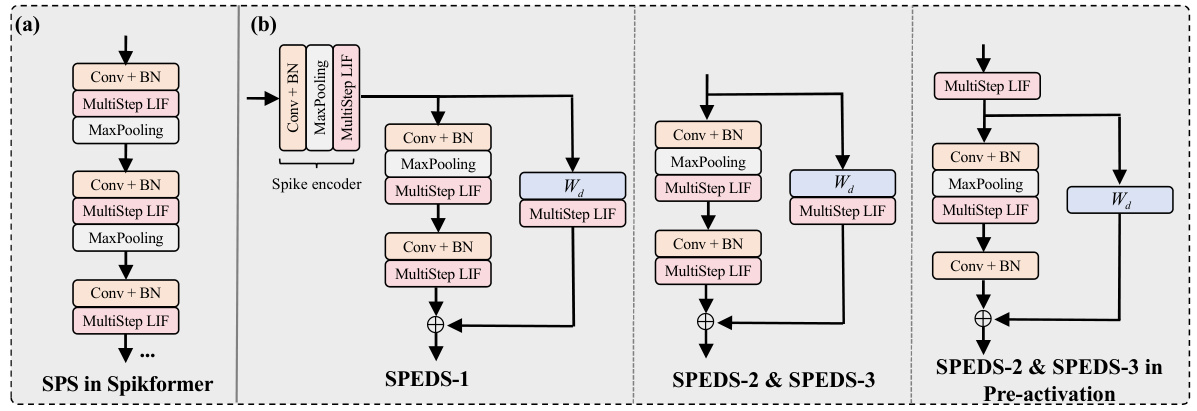

The figure illustrates the architecture of QKFormer, a hierarchical spiking transformer. It shows three stages. In stage 1, the input with dimensions of To × H × W × n is processed by SPEDS-1 (Spiking Patch Embedding with Deformed Shortcut) and N1 QKFormer blocks, each containing a Q-K Attention module and a SMLP (Spiking MLP) block. Stage 2 processes the output of stage 1 with SPEDS-2 and N2 QKFormer blocks, reducing the number of tokens. Finally, stage 3 uses SPEDS-3 and N3 Spikformer blocks (using Spiking Self Attention), further reducing tokens and increasing channels. This hierarchical design enables multi-level spiking feature representation, improving performance.

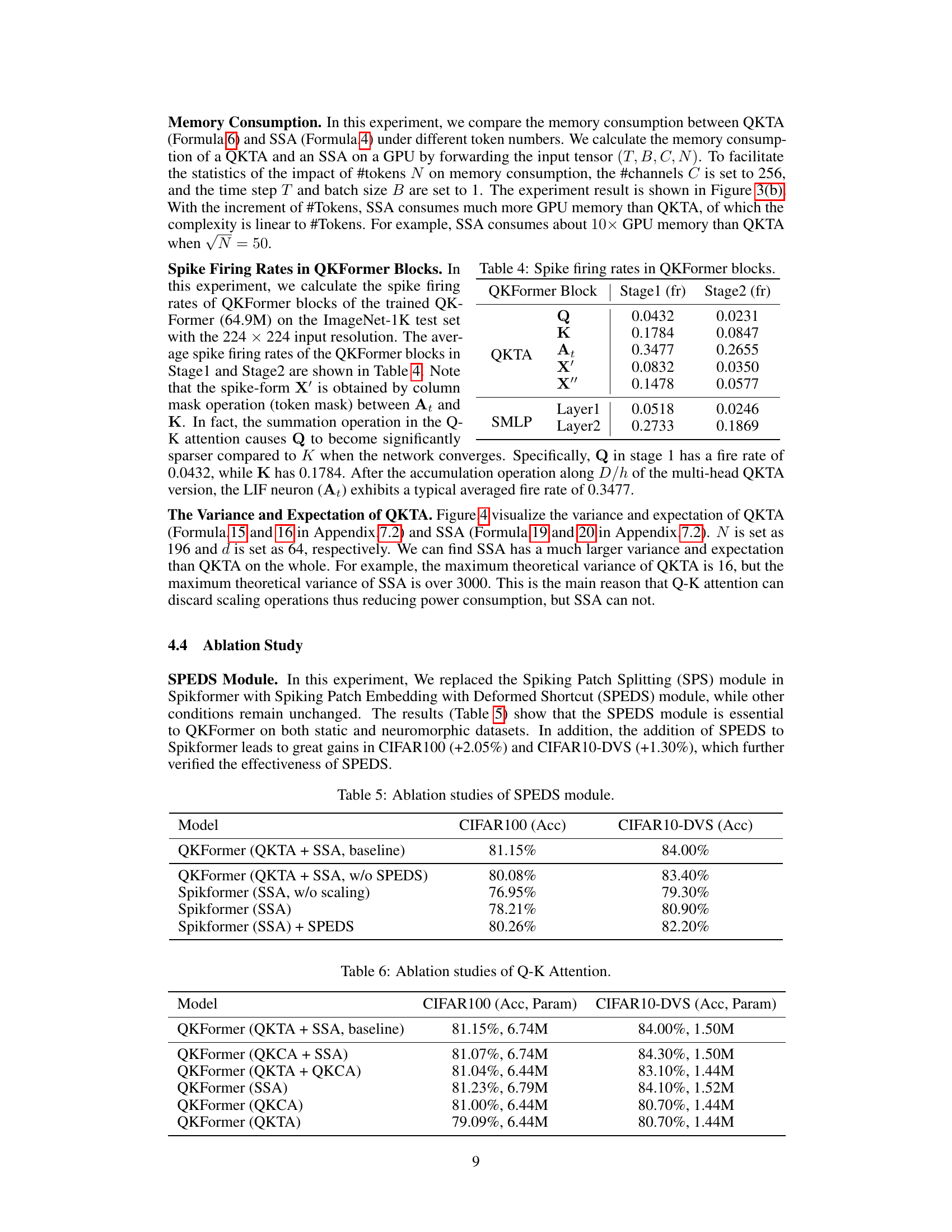

This figure visualizes the Q-K token attention mechanism and compares its memory consumption with SSA. The left panel (a) shows heatmaps of query (Q), key (K), and output (X’) matrices for Stage 1 and Stage 2 of the QKFormer model. White pixels indicate a value of 1 (spike), and black pixels represent 0 (no spike). The right panel (b) displays a graph comparing the GPU memory usage of QKTA and SSA across various numbers of tokens (N), demonstrating QKTA’s superior memory efficiency, especially as the number of tokens increases.

This figure visualizes the variance and expectation of both SSA (Spiking Self Attention) and QKTA (Q-K Token Attention) methods. It assumes that spike elements in both methods are independent and follow a Bernoulli distribution. The plots show how the variance and expectation change with respect to different firing rates (fQ, fK, fV) which represent the probability of a spike occurring for query, key, and value elements, respectively. Panel (a) shows the results for SSA, and panel (b) for QKTA, highlighting the difference between the two methods. The key takeaway is that QKTA shows significantly smaller variance and expectation than SSA. This is important because it justifies the elimination of scaling factors in QKTA, improving energy efficiency and simplicity.

This figure compares the Spiking Patch Splitting (SPS) module used in the Spikformer model with the Spiking Patch Embedding with Deformed Shortcut (SPEDS) module used in the QKFormer model. It illustrates the architectural differences between these two modules, highlighting how SPEDS integrates deformed shortcuts to enhance the transmission and integration of spiking information. The comparison showcases a key improvement in QKFormer’s design for efficient information flow in the network.

This figure shows the training and testing performance of the QKFormer model on the ImageNet-1K dataset. It displays four sub-figures: (a) Training loss illustrating the model’s loss during training across different model sizes (64.96M, 29.08M, and 16.47M parameters). (b) Testing loss representing the model’s performance on unseen data during training. (c) Top-1 accuracy showing the percentage of correctly classified images in the top prediction. (d) Top-5 accuracy showing the percentage of images where the correct class was among the top 5 predictions. The input image resolution used for both training and testing was 224x224 pixels.

More on tables

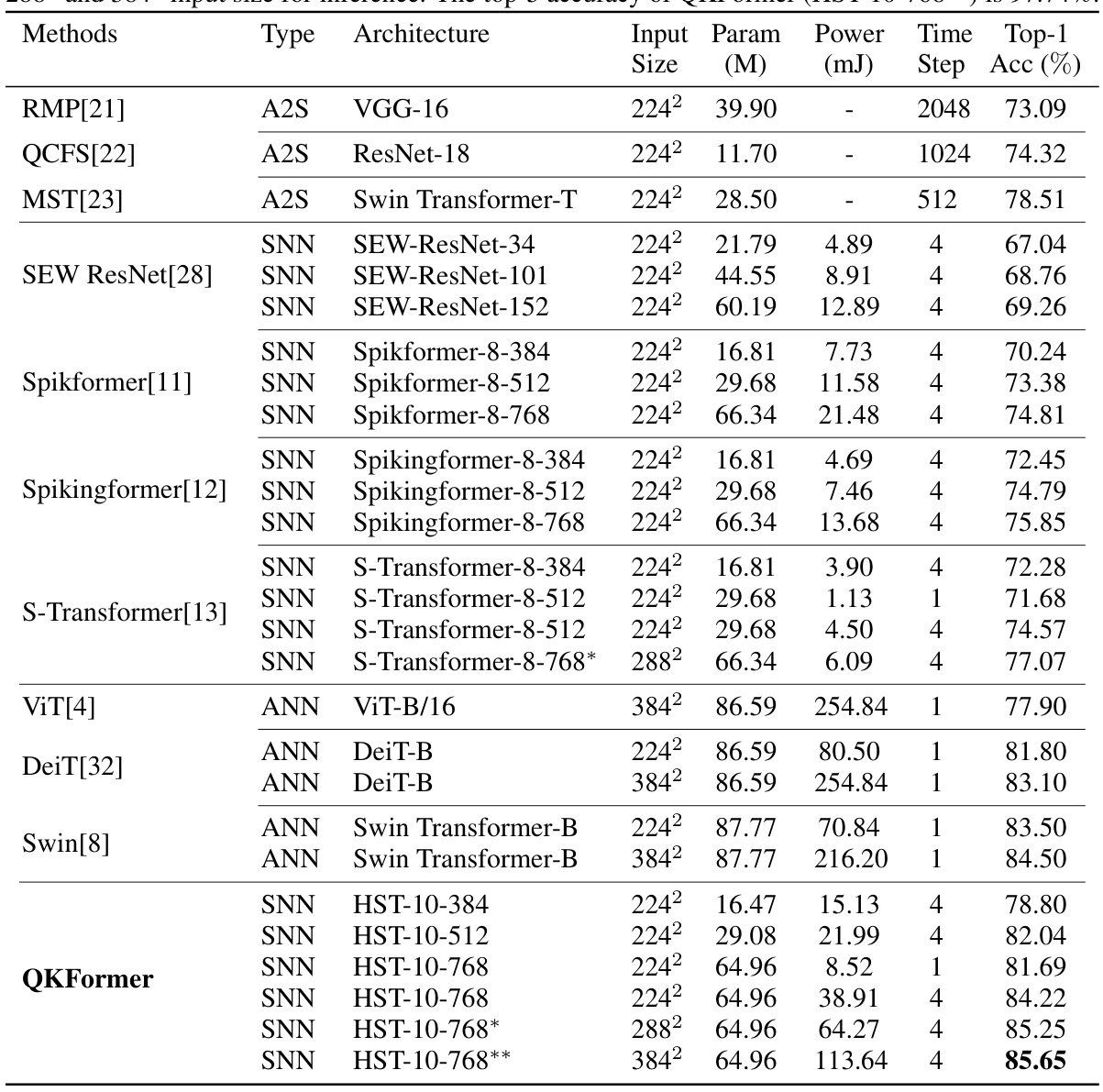

This table presents the results of various methods (both ANNs and SNNs) on the ImageNet-1K dataset. It compares their top-1 accuracy, model parameters, power consumption (in mJ), and number of time steps. It highlights the superior performance of QKFormer, especially when compared to other SNN models, and notes the difference in power consumption between ANNs and SNNs.

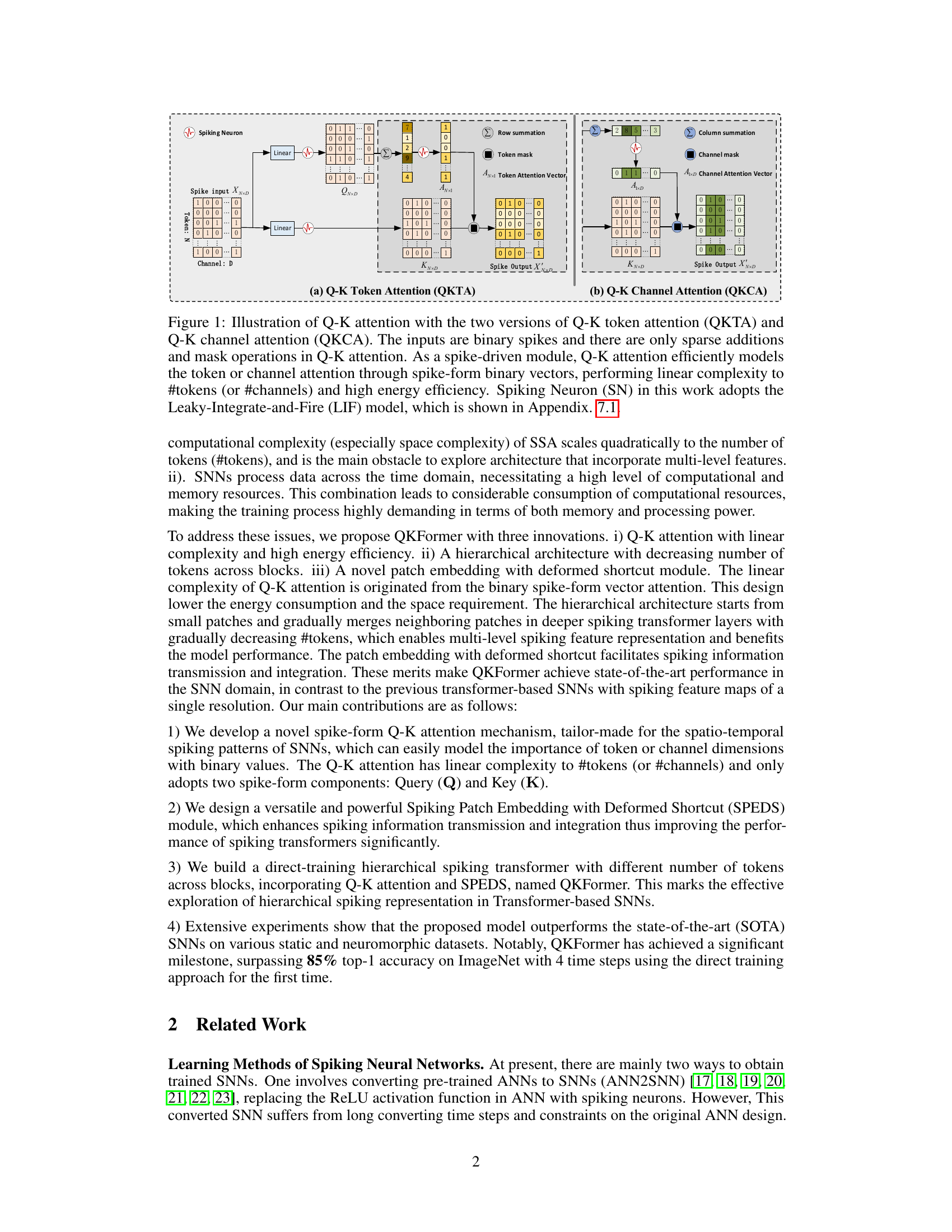

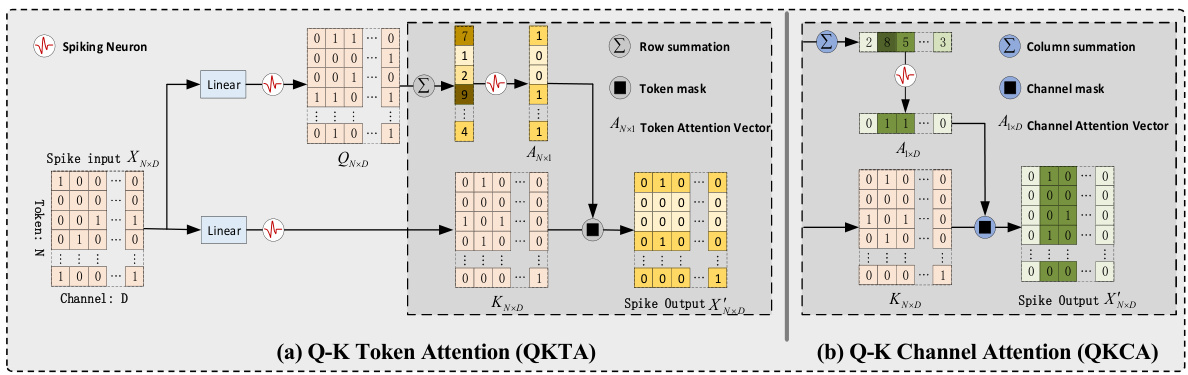

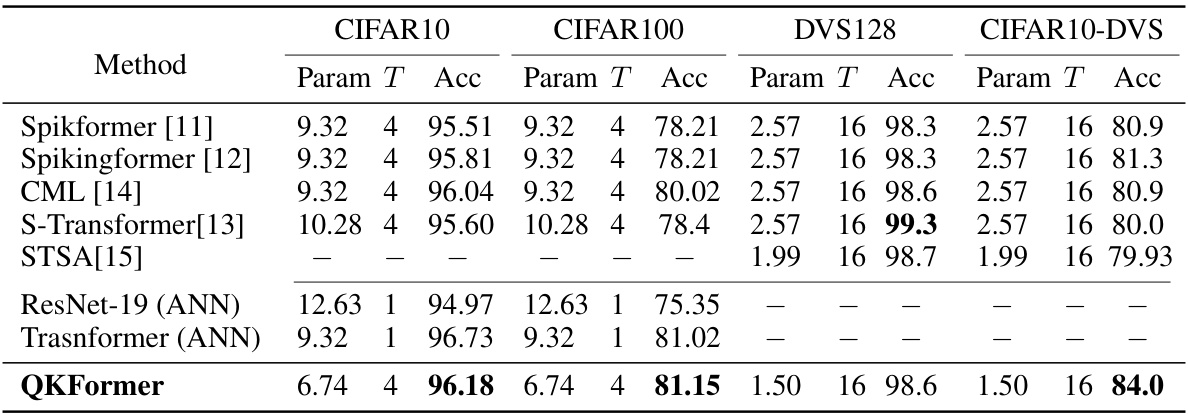

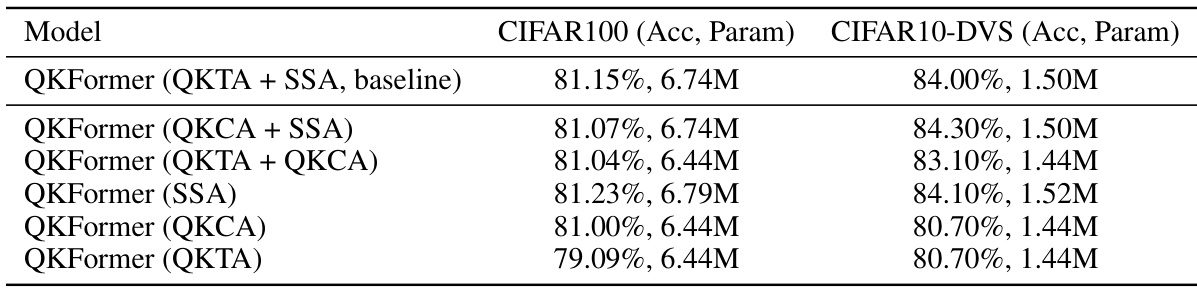

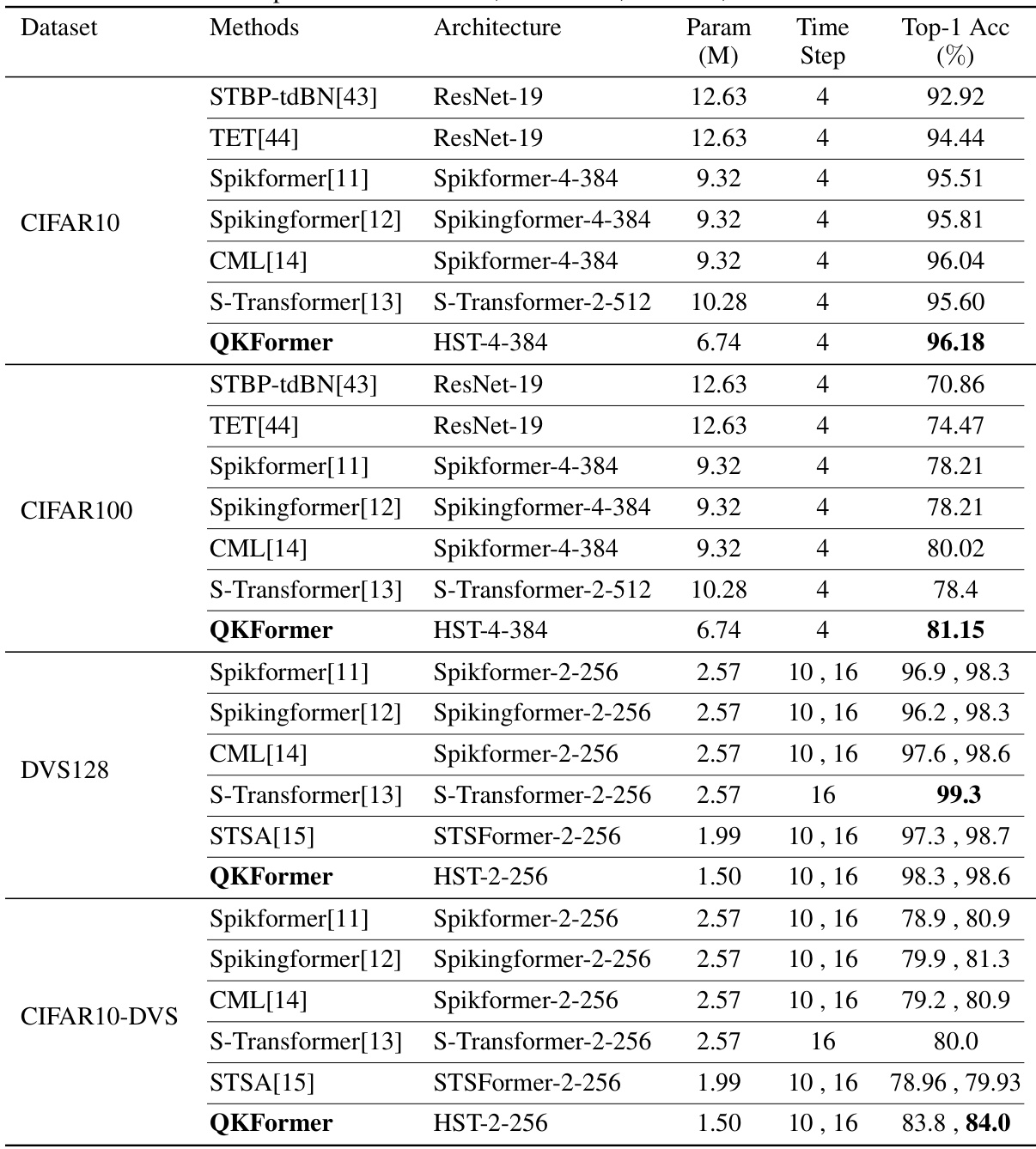

This table compares the performance of different spiking neural network models on four benchmark datasets: CIFAR10, CIFAR100, DVS128, and CIFAR10-DVS. The metrics used for comparison are the number of parameters (in millions), the number of time steps used, and the top-1 accuracy achieved. The table includes both Spiking Neural Network (SNN) models and Artificial Neural Network (ANN) baselines for comparison purposes. Note that the time steps may differ between models, affecting the interpretation of the accuracy.

This table presents a comparison of various methods (both ANNs and SNNs) on ImageNet-1K, including their model type, architecture, input size, number of parameters, power consumption (in mJ), number of time steps, and top-1 accuracy (%). It highlights the superior performance of QKFormer, especially compared to other SNN models. Note that the power data is calculated based on theoretical energy consumption and varies depending on the hardware.

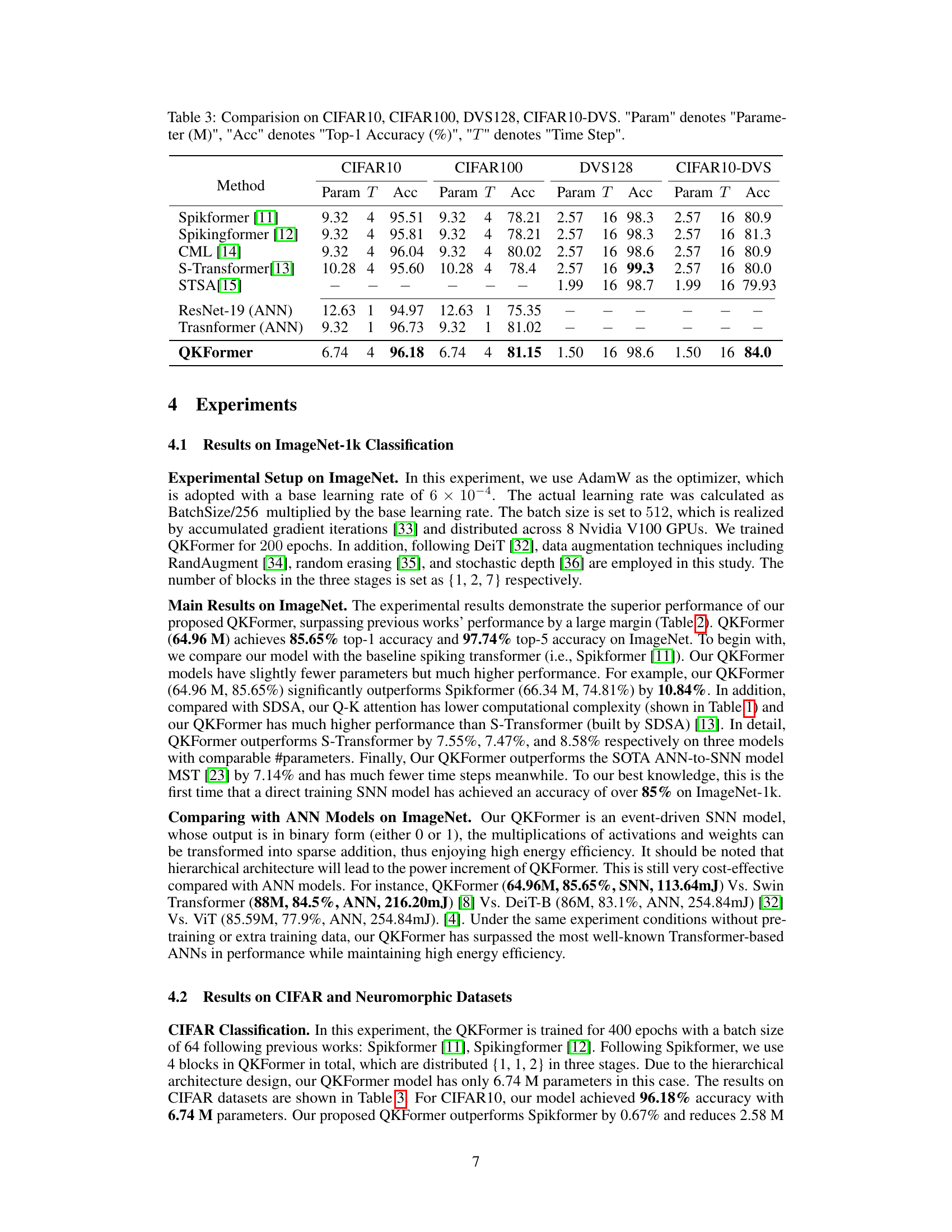

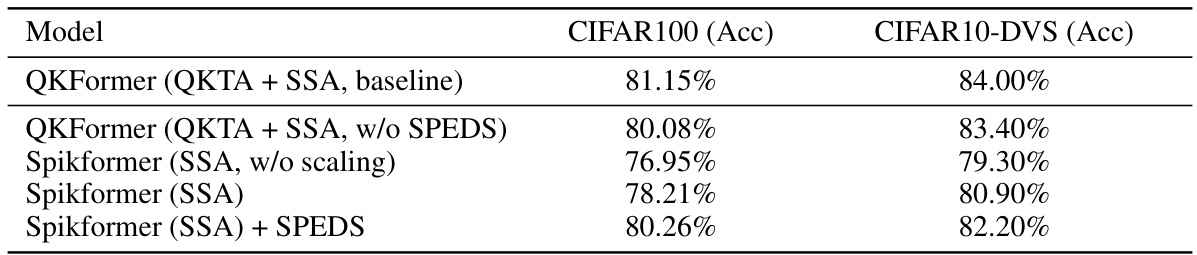

This table presents the ablation study results focusing on the impact of the Spiking Patch Embedding with Deformed Shortcut (SPEDS) module on the performance of the QKFormer model. It compares the performance of QKFormer with and without SPEDS, as well as Spikformer with and without SPEDS, on CIFAR100 and CIFAR10-DVS datasets. The results demonstrate the positive contribution of the SPEDS module to improving accuracy.

This table presents the ablation study results focusing on the impact of different Q-K attention mechanisms on the model’s performance. It shows the top-1 accuracy and the number of parameters (in millions) for various configurations of QKFormer on CIFAR100 and CIFAR10-DVS datasets. The baseline is QKFormer using QKTA + SSA. The other rows show variations on the attention module, such as using only QKCA or QKTA, or using only SSA. The results demonstrate the impact of the Q-K attention choice on model accuracy and efficiency.

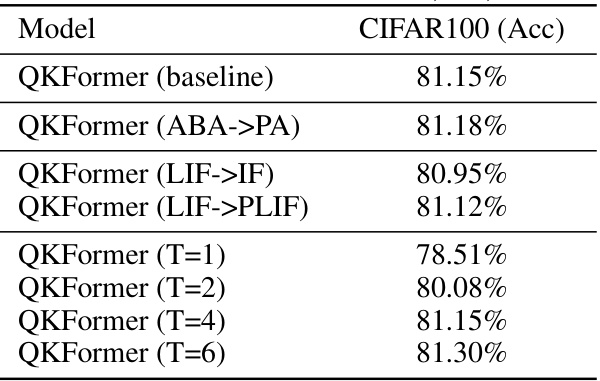

This table presents the ablation study results on CIFAR100, comparing the performance of QKFormer under different configurations. Specifically, it investigates the impact of changing the residual connection type (ABA to PA), the spiking neuron model (LIF to IF, LIF to PLIF), and the number of time steps (T). The baseline is QKFormer with ABA residual connection, LIF neuron model, and 4 time steps (T=4).

This table presents the results of various methods (both SNNs and ANNs) on the ImageNet-1K dataset. It shows the model type (ANN or SNN), architecture, input size, number of parameters, power consumption (in mJ), number of time steps, and top-1 accuracy. The table highlights QKFormer’s superior performance and energy efficiency compared to other SNN and ANN approaches, especially achieving a groundbreaking top-1 accuracy exceeding 85% on ImageNet-1K.

This table presents a comparison of various methods (both ANNs and SNNs) on the ImageNet-1K dataset. Metrics include top-1 accuracy, number of parameters, power consumption (in millijoules), and the number of time steps. The table highlights the superior performance of QKFormer, particularly when compared to similar-sized Spiking Transformer models.

This table presents a comparison of various models’ performance on the ImageNet-1K dataset, including the top-1 accuracy, the number of parameters, power consumption, and the number of time steps. It compares both spiking neural network (SNN) and artificial neural network (ANN) models, highlighting QKFormer’s superior performance and efficiency.

Full paper#