↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Training deep learning models is energy-intensive. Existing analog hardware accelerators often incorporate digital circuitry, lacking a strong theoretical foundation and limiting their efficiency. The high energy consumption of gradient-based optimization is a major bottleneck.

This work introduces Feedforward-tied Energy-based Models (ff-EBMs), a novel hybrid model architecture combining feedforward and energy-based blocks. It develops a new algorithm that efficiently computes gradients end-to-end by chaining backpropagation and equilibrium propagation. Experiments on ff-EBMs using Deep Hopfield Networks demonstrate significant speedups (up to 4x) and improved performance on ImageNet32, setting a new state-of-the-art for the Equilibrium Propagation (EP) literature.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel approach to train analog and digital hybrid neural networks, addressing the critical need for more energy-efficient AI. It offers a scalable and incremental pathway for integrating self-trainable analog components into existing digital systems, potentially revolutionizing AI hardware design. The state-of-the-art results achieved on ImageNet32 also demonstrate the effectiveness of this approach.

Visual Insights#

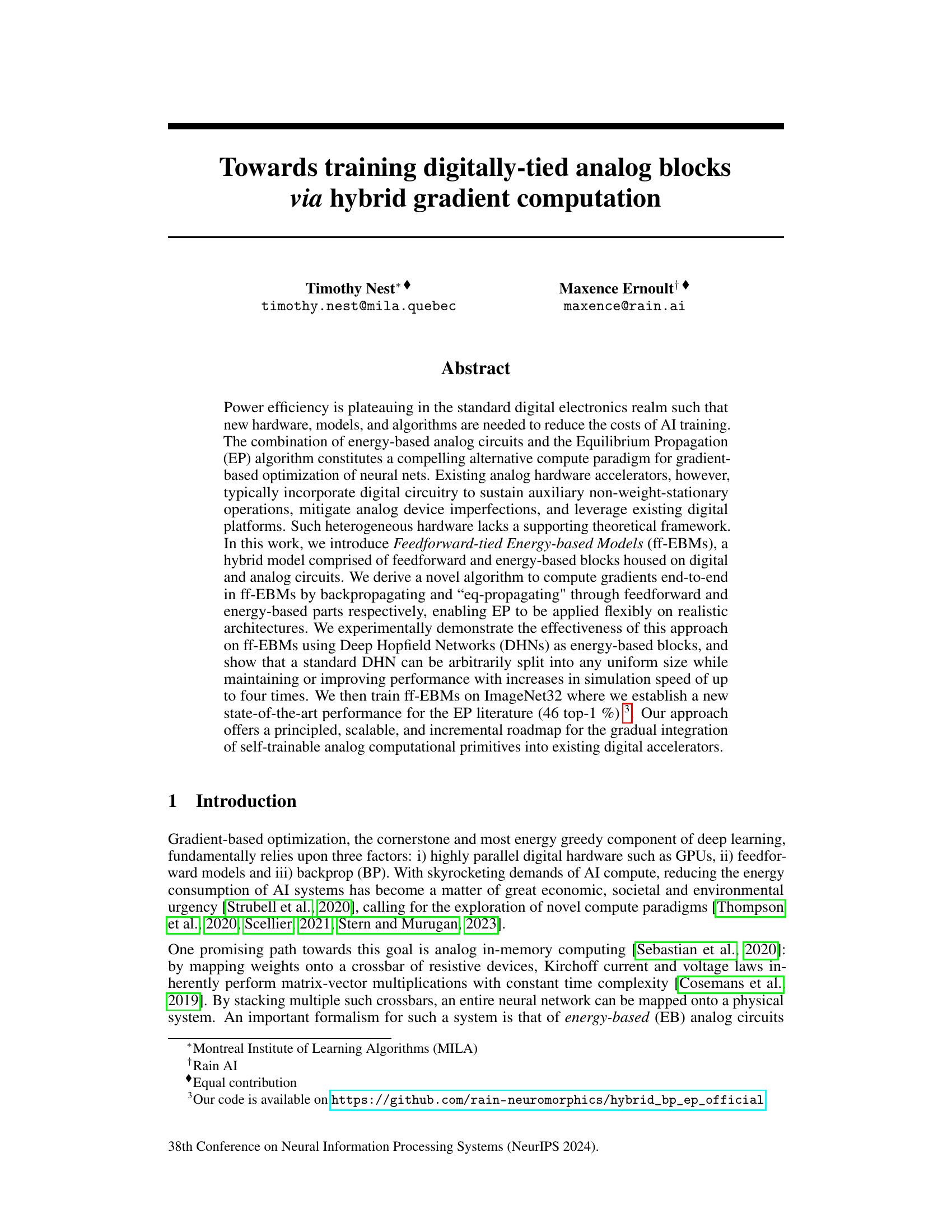

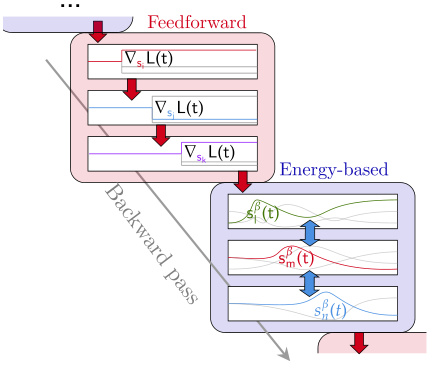

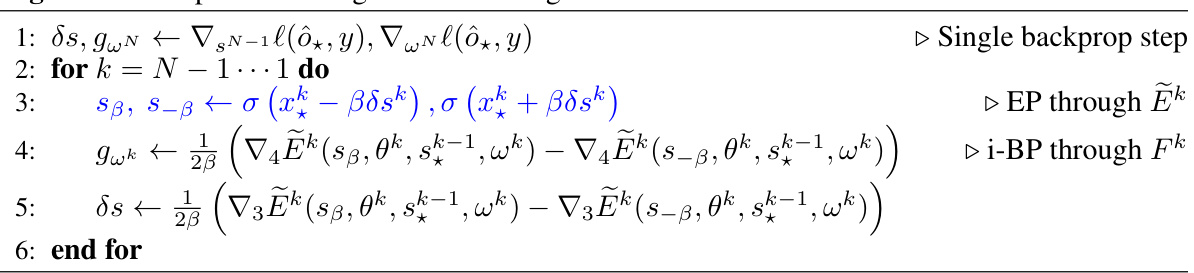

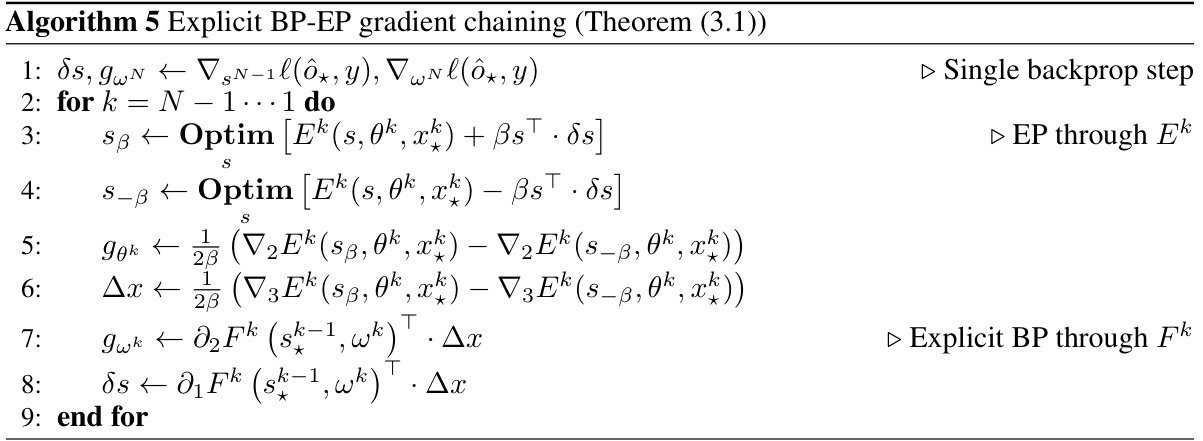

This figure illustrates the backpropagation (BP) and equilibrium propagation (EP) algorithm chaining for hybrid models comprising feedforward and energy-based blocks located on digital and analog circuits. The red blocks represent feedforward layers that use backpropagation, while the blue blocks represent energy-based blocks that utilize equilibrium propagation. The figure shows how error signals propagate backward through both types of blocks to update the model parameters.

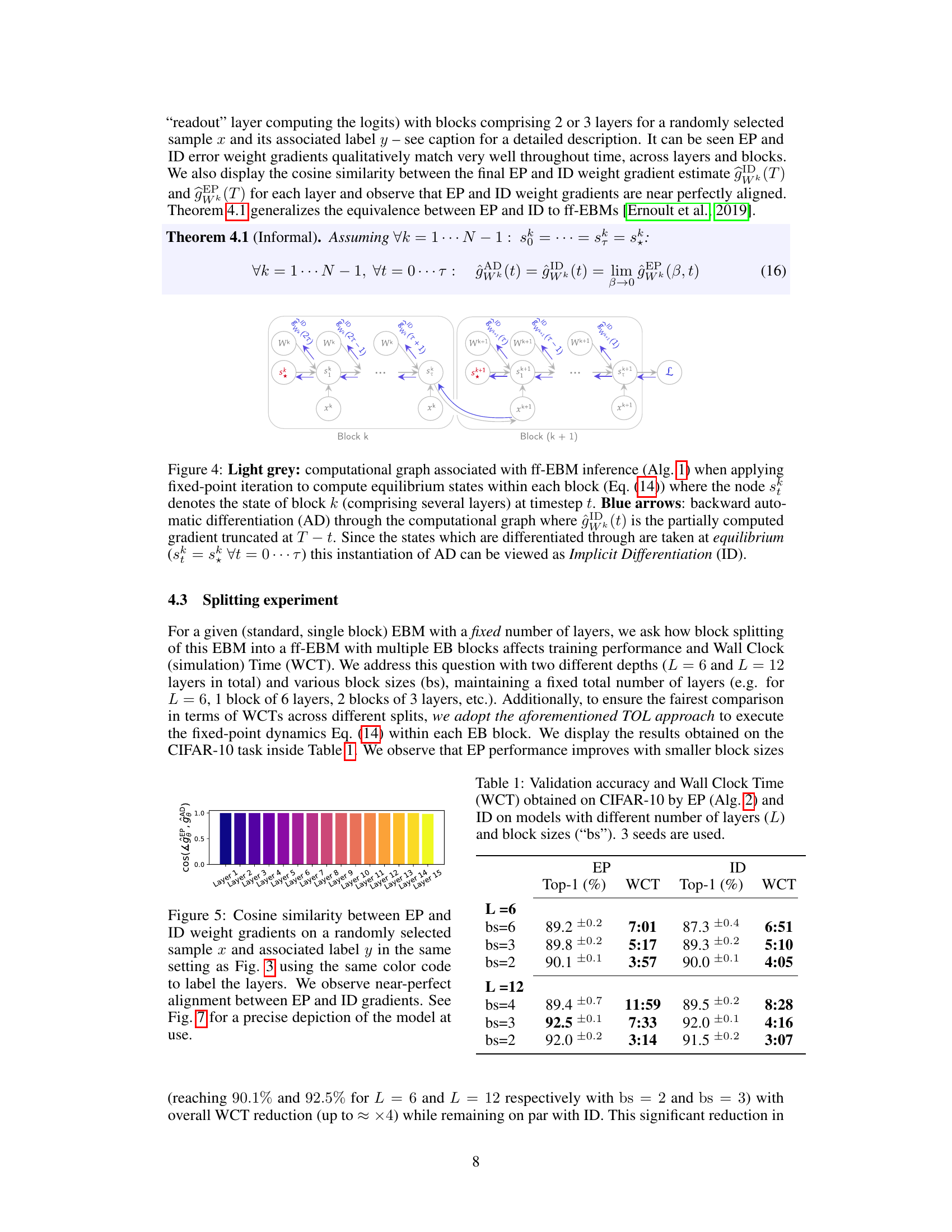

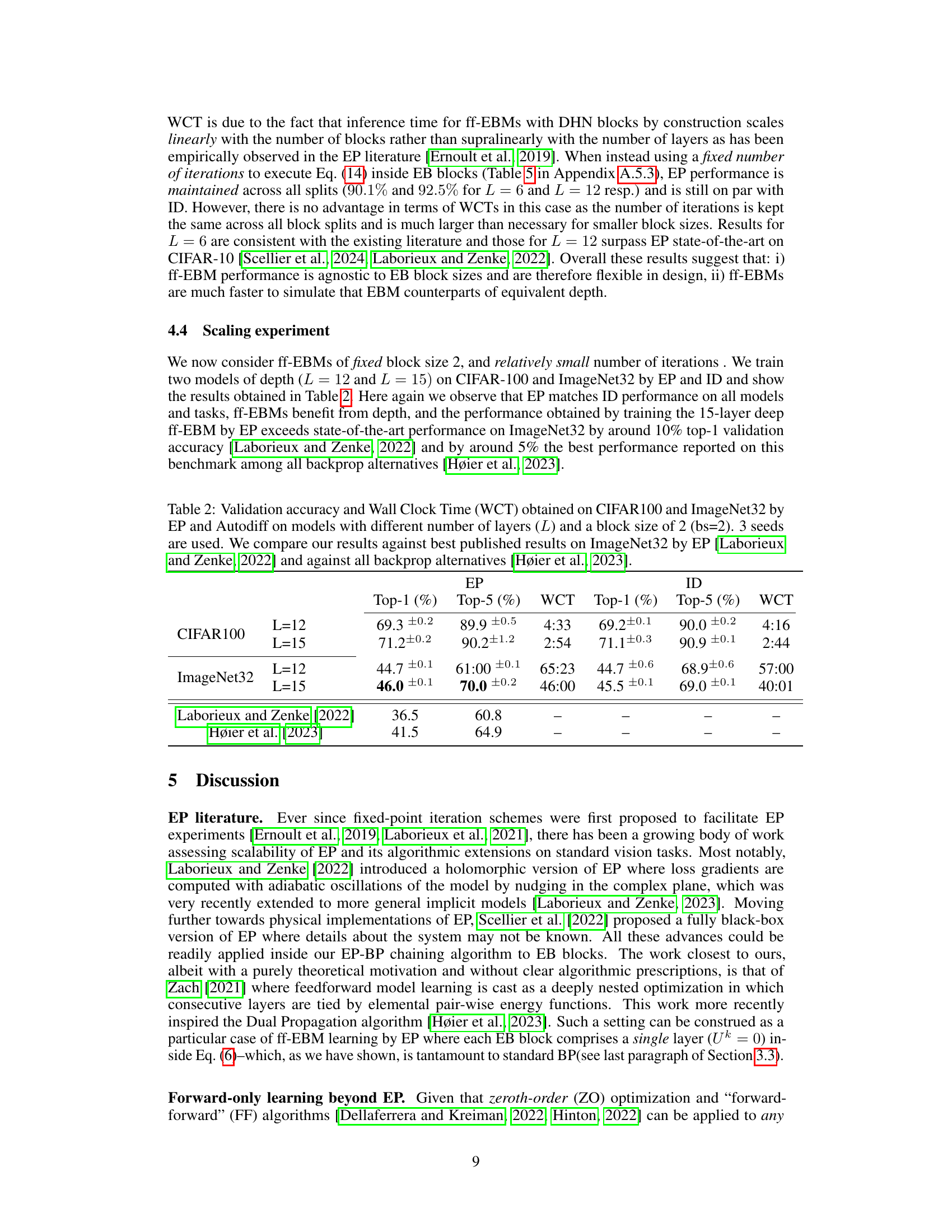

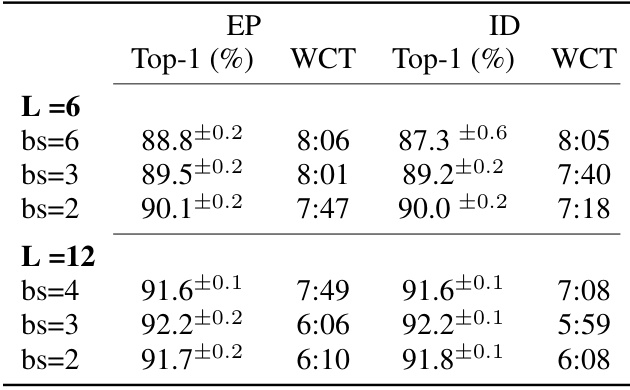

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on the CIFAR-10 dataset to evaluate the performance of two algorithms, EP (Equilibrium Propagation) and ID (Implicit Differentiation), using Feedforward-tied Energy-based Models (ff-EBMs) with varying numbers of layers and block sizes. The table shows the top-1 accuracy and wall clock time (WCT) for each configuration, providing insights into the impact of model architecture on both accuracy and computational efficiency. The results are averaged across three different seeds to ensure statistical reliability.

In-depth insights#

Hybrid Gradient Flow#

A hypothetical ‘Hybrid Gradient Flow’ in a research paper would likely explore the combination of different gradient computation methods for training machine learning models, particularly within the context of energy-based models (EBMs) and analog computing. The core idea would be to leverage the strengths of multiple approaches, such as backpropagation (BP) and equilibrium propagation (EP), to overcome individual limitations and improve efficiency. For example, BP, while highly effective, is computationally expensive, whereas EP, being a biologically-inspired algorithm, could offer significant energy efficiency, particularly when implemented on specialized analog hardware. A hybrid approach could involve using BP for parts of the network and EP for others, perhaps routing the computation based on the model architecture or hardware constraints. This approach could unlock advantages like faster convergence, improved energy efficiency, and the ability to integrate self-trainable analog components into digital systems. A key challenge in developing a hybrid gradient flow would be developing a theoretical framework and algorithms to seamlessly integrate the different gradient computation methods. This would involve careful consideration of error propagation, parameter updates, and potential issues stemming from discrepancies between different optimization techniques. The paper might explore specific model architectures, like a combination of feedforward and energy-based blocks, where BP and EP are applied respectively. The results might highlight the trade-offs between accuracy, energy efficiency, and computational cost under different hybrid configurations. Ultimately, a successful ‘Hybrid Gradient Flow’ framework would offer a powerful approach to training more efficient and scalable machine learning models, pushing the boundaries of AI hardware and algorithms.

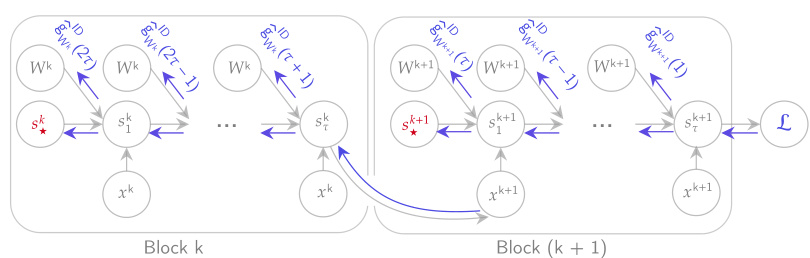

ff-EBM Architecture#

The ff-EBM architecture represents a hybrid approach to neural network design, cleverly combining the strengths of feedforward and energy-based models. Feedforward blocks, typically implemented digitally, handle tasks such as linear transformations and convolutions, leveraging the speed and scalability of existing digital hardware. These blocks are seamlessly integrated with energy-based blocks (EBMs), often realized using analog circuits. The EBMs offer significant advantages in energy efficiency and potentially faster computation, especially for matrix multiplications. A key aspect is the novel algorithm that enables end-to-end gradient computation, smoothly chaining backpropagation through feedforward layers with an ’eq-propagation’ method through the EBM, thus bridging digital and analog components for efficient training. The modular nature of this architecture allows flexible design, enabling the arbitrary division of a network into feedforward and EBM parts while maintaining or even improving performance, which highlights the significant potential of this hybrid design. Deep Hopfield Networks (DHNs) are used as example EBMs, showcasing the capability of the proposed framework. Overall, the ff-EBM architecture presents a promising path for future AI hardware, suggesting that combining digital and analog computation can enhance energy efficiency and potentially increase computation speed for training large scale models.

BP-EP Gradient Chain#

The concept of a ‘BP-EP Gradient Chain’ suggests a hybrid approach to training neural networks, combining the strengths of backpropagation (BP) and Equilibrium Propagation (EP). BP, a workhorse of deep learning, is computationally expensive. EP, an energy-based method, offers potential energy efficiency but faces scalability challenges. A gradient chain might involve using BP for feedforward layers (where parallelization is efficient) and EP for energy-based layers (potentially implemented in energy-efficient analog hardware). The key challenge lies in seamlessly integrating these two fundamentally different approaches. This requires a theoretical framework to show how the gradients from BP and EP can be combined accurately and efficiently. A successful BP-EP chain could leverage the speed and parallelizability of BP with the potential energy efficiency of EP. This could lead to faster and more sustainable training of large neural networks.

ImageNet32 SOTA#

The claim of achieving state-of-the-art (SOTA) results on ImageNet32 is a significant assertion requiring careful scrutiny. A true SOTA benchmark necessitates a thorough comparison against existing methods, using identical evaluation metrics and datasets. The paper needs to explicitly detail the specific models and approaches used for comparison, highlighting the performance differences and statistical significance of the improvement. The reproducibility of the results is crucial; a detailed description of experimental setup, hyperparameters, and training procedures must be provided to allow others to verify the claimed SOTA status. It’s important to examine if the reported accuracy accounts for the entire ImageNet32 dataset or a subset, and if any data augmentation techniques were used. Finally, the generalizability of the SOTA results should be discussed – can the improvements observed on ImageNet32 translate to other datasets and tasks?

Analog Integration#

Analog integration in AI accelerators presents a compelling path towards energy-efficient deep learning. Energy-based models (EBMs), implemented using analog circuits, offer potential advantages in terms of speed and power consumption compared to purely digital approaches. However, challenges remain in bridging the gap between the theoretical elegance of EBMs and the practical realities of hardware implementation. Noise, device imperfections, and non-idealities in analog circuits pose significant hurdles to training and inference. A hybrid approach, combining digital and analog components, emerges as a pragmatic strategy. This approach utilizes digital circuitry to handle tasks that are difficult or impractical to implement in analog, while leveraging the energy efficiency of analog for computationally intensive operations. Gradual integration, starting with self-trainable analog primitives within existing digital accelerators, presents a potentially scalable roadmap. Future research should focus on addressing hardware limitations, developing robust training algorithms for hybrid systems, and exploring novel analog circuit designs to maximize energy efficiency and scalability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

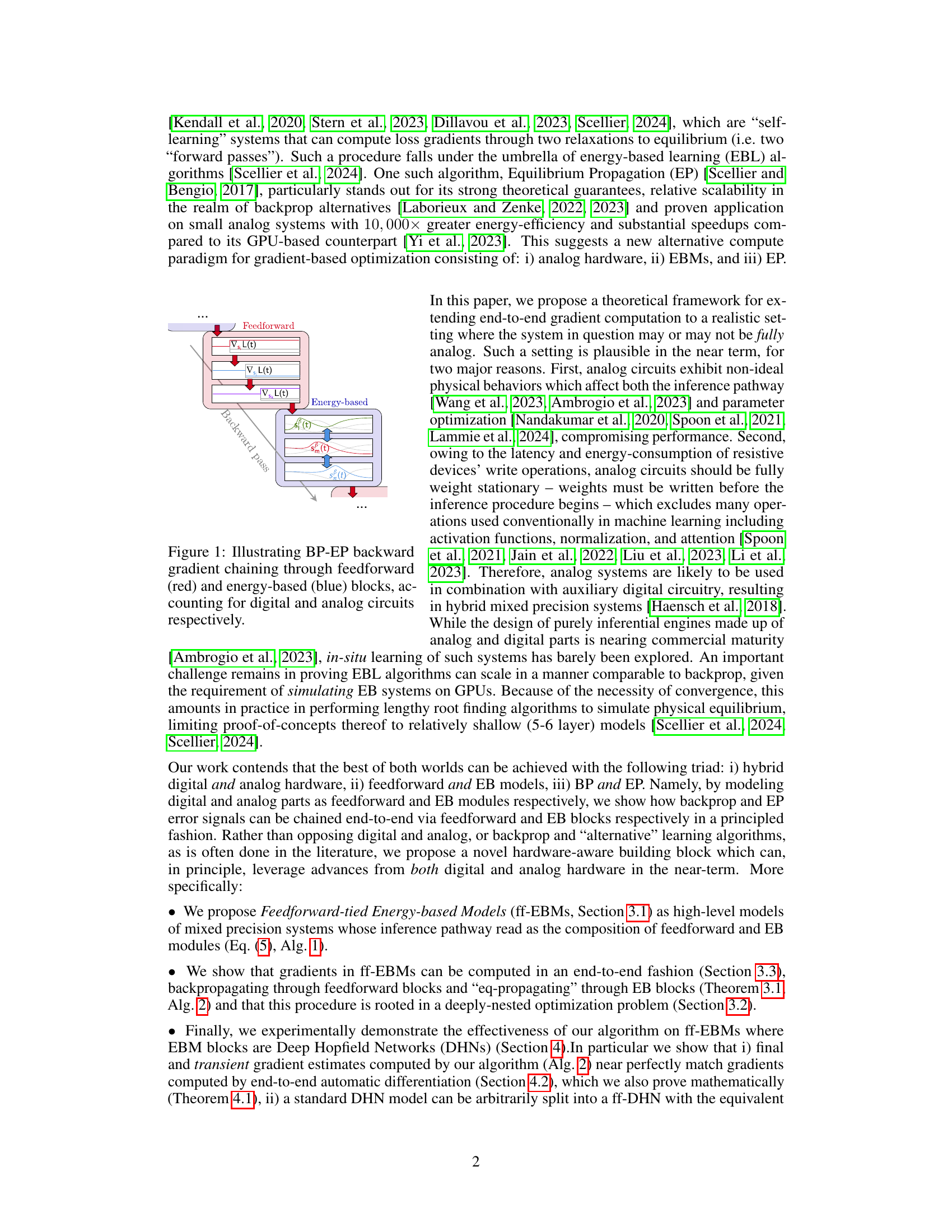

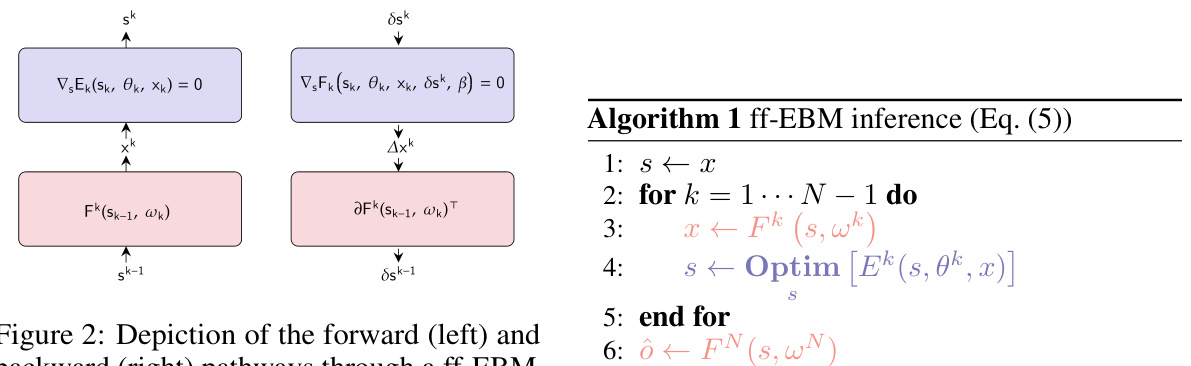

This figure illustrates the forward and backward propagation of signals through a Feedforward-tied Energy-based Model (ff-EBM). The left side shows the forward pass, where data is processed sequentially through feedforward (pink) and energy-based (blue) blocks. The right side shows the backward pass, illustrating how gradients are computed using a combination of backpropagation (BP) through feedforward blocks and equilibrium propagation (EP) through energy-based blocks. The combination of digital feedforward blocks and analog energy-based blocks is central to the hybrid approach of the paper. This figure visually summarizes how the proposed algorithm combines standard backpropagation and equilibrium propagation for end-to-end gradient computation.

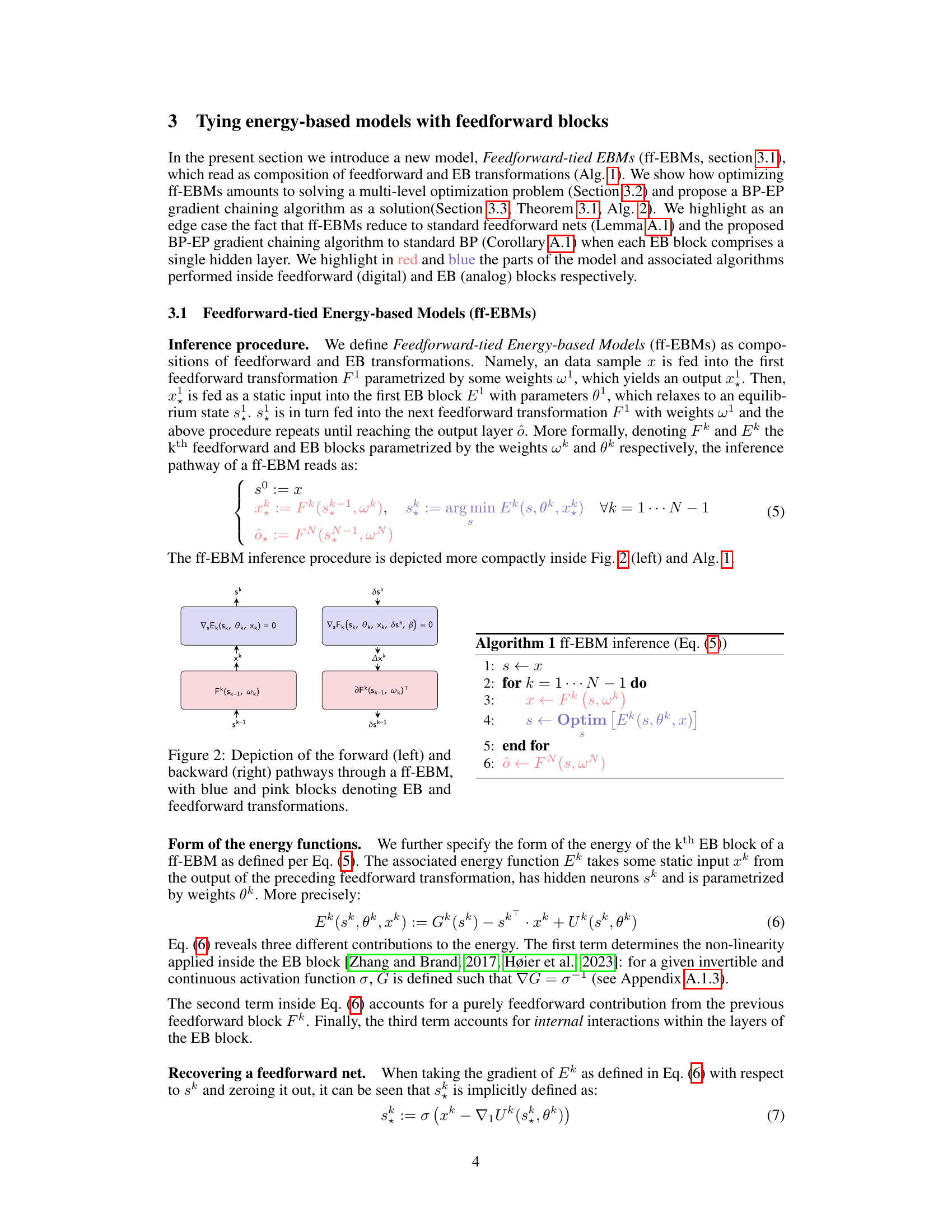

This figure compares the gradients computed by Equilibrium Propagation (EP) and Implicit Differentiation (ID) methods. It visualizes the transient gradient dynamics for a ff-EBM (Feedforward-tied Energy-based Model) with 6 blocks and 15 layers on a single data sample. Each subplot shows gradients for a single layer across all blocks, demonstrating how the gradients evolve over time as the methods propagate backward (ID) or forward (EP). The close alignment of the curves shows that the gradients computed by both methods match closely.

This figure compares the gradients computed by Equilibrium Propagation (EP) and Implicit Differentiation (ID) methods for a feedforward-tied energy-based model (ff-EBM). The ff-EBM consists of 6 blocks and 15 layers. Each subplot shows the gradients for a single layer within a block, with time progressing backward from the last block to the first block. The dotted lines represent EP and the solid lines represent ID. The figure demonstrates the close agreement between EP and ID estimates.

This figure illustrates the forward and backward passes of a Feedforward-tied Energy-based Model (ff-EBM). The forward pass shows data flowing through feedforward blocks (pink) and energy-based blocks (blue), with each energy-based block reaching an equilibrium state. The backward pass shows the gradient chaining method, where backpropagation occurs through the feedforward blocks and ’eq-propagation’ (a process derived from equilibrium propagation) occurs through the energy-based blocks. The arrows indicate the direction of signal flow, showcasing the hybrid approach that combines digital (feedforward) and analog (energy-based) computation.

This figure shows the cosine similarity between the EP and ID weight gradients across different layers for a random sample. The color coding of the layers matches figures 3 and 5. It demonstrates that the EP and ID gradients are nearly identical, indicating a strong agreement between the two methods.

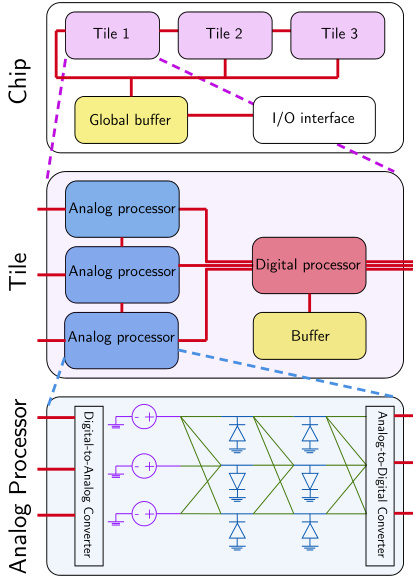

This figure illustrates the architecture of feedforward-tied energy-based models (ff-EBMs) at chip scale. It combines analog and digital processors to perform equilibrium propagation (EP). The analog processors consist of resistive devices, diodes, and voltage sources, while the digital processors handle control and data transfer. The system has multiple tiles, each containing analog processors, a digital processor, and a buffer. ADCs and DACs facilitate communication between analog and digital parts. The global buffer and I/O interface provide overall system communication and interaction with the external environment.

This figure compares the transient dynamics of Equilibrium Propagation (EP) and Implicit Differentiation (ID) for computing gradients in a Feedforward-tied Energy-based Model (ff-EBM). The ff-EBM has 6 blocks and 15 layers, with varying block sizes. The plot shows partially computed gradients over time for both methods, demonstrating that they closely align.

This figure compares the transient dynamics of Equilibrium Propagation (EP) and Implicit Differentiation (ID) for computing gradients in a feedforward-tied energy-based model (ff-EBM). It shows that partially computed gradients for both methods align closely over time and across layers and blocks of a 15-layer ff-EBM with Deep Hopfield Networks (DHNs) as energy-based modules. Each subfigure shows gradients for different weights in each layer to illustrate the similarity between the two gradient computation methods.

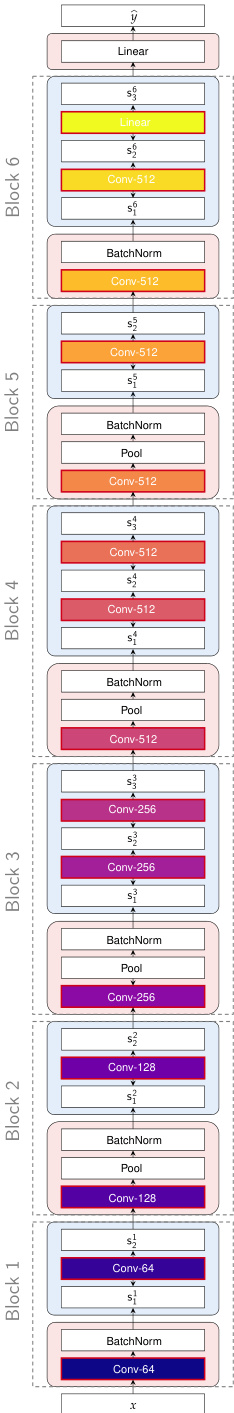

This figure shows the architecture of the feedforward-tied energy-based model (ff-EBM) used in the static gradient analysis of the paper. It details the arrangement of convolutional layers, batch normalization layers, pooling layers, and the energy-based blocks within the ff-EBM. The color-coding of the blocks matches that used in Figures 3 and 5, allowing for easy cross-referencing between the figures. The caption highlights the important detail that the term ‘block’ refers to a combination of feedforward and energy-based blocks, not just one or the other.

This figure compares the gradient calculations of Equilibrium Propagation (EP) and Implicit Differentiation (ID) methods on a Feedforward-tied Energy-based Model (ff-EBM). The ff-EBM used has 6 blocks and 15 layers, with varying block sizes. The graph plots partially computed gradients across the layers, showing how they align over time for both methods. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of EP in matching ID gradients, highlighting its potential as a viable alternative for gradient-based optimization in this mixed digital-analog setting.

More on tables

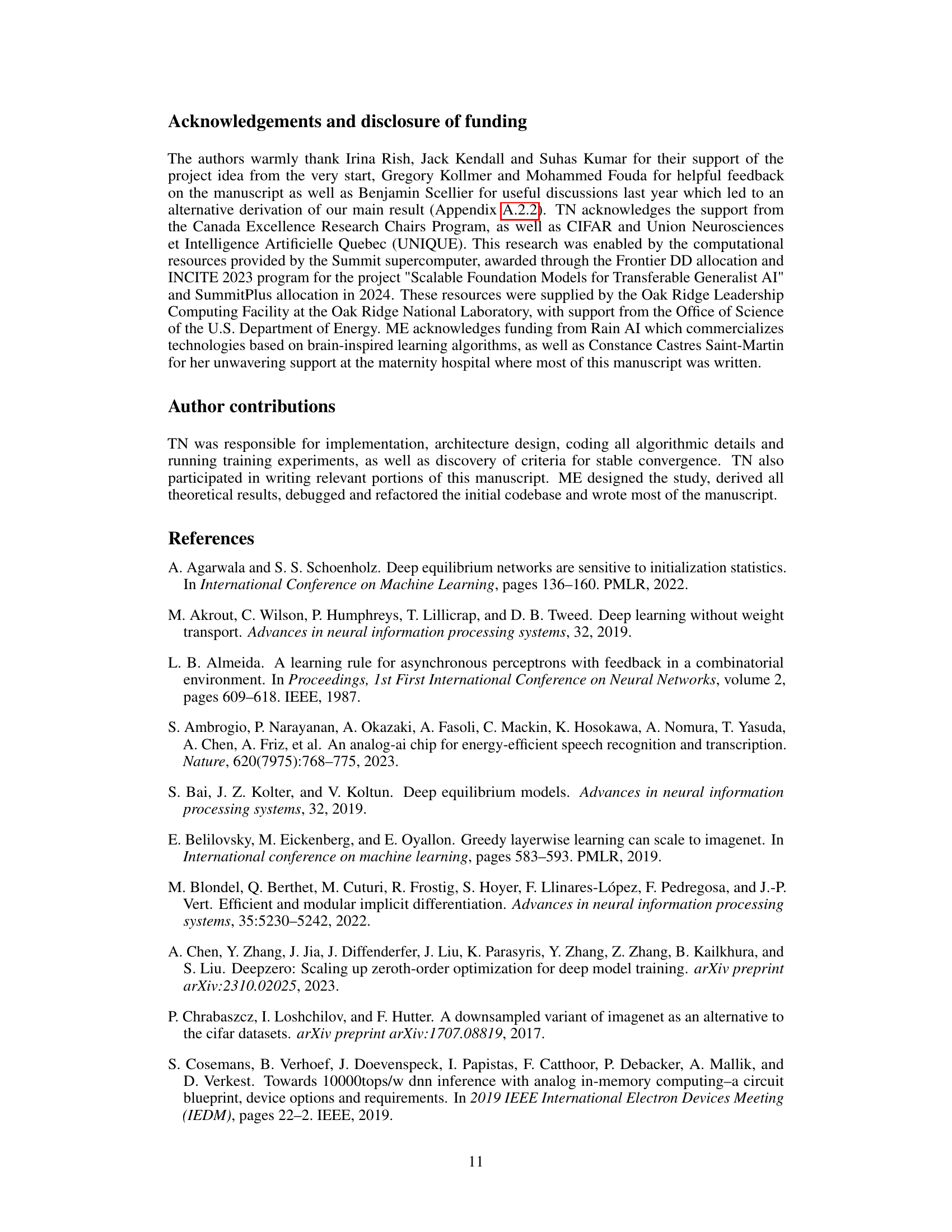

This table presents the top-1 and top-5 validation accuracy and wall clock time (WCT) for models trained on CIFAR100 and ImageNet32 using both Equilibrium Propagation (EP) and Implicit Differentiation (ID). The results are shown for models with 12 and 15 layers and compare the performance of EP against state-of-the-art results from the literature.

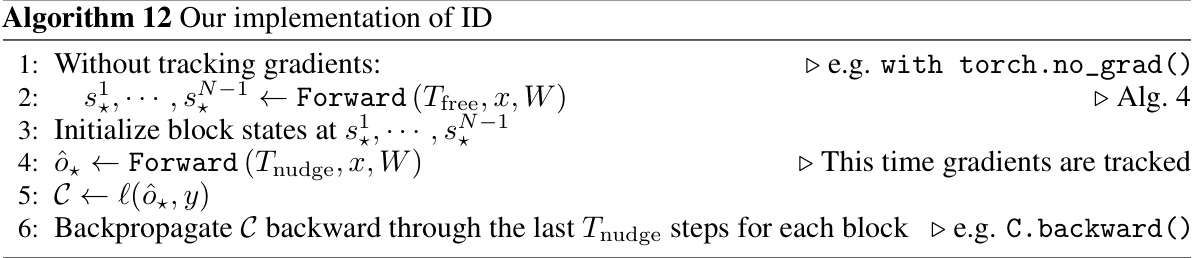

This table presents the validation accuracy and wall-clock time (WCT) achieved on the CIFAR-10 dataset using both Equilibrium Propagation (EP) and Implicit Differentiation (ID) methods. The experiments were performed on models with varying numbers of layers (L) and different block sizes (bs), which represent how the model is split into feedforward and energy-based components. The results show how the performance and computational efficiency of the model change with different architectural configurations.

This table presents the results of validation accuracy and wall clock time on CIFAR-10 dataset for different model configurations using Equilibrium Propagation (EP) and Implicit Differentiation (ID). It shows how the performance and computation time vary with the number of layers (L) and different block sizes (bs) in the feedforward-tied energy-based models (ff-EBMs). The results demonstrate the impact of model architecture on both accuracy and efficiency.

This table presents the results of validation accuracy and wall clock time (WCT) on CIFAR-10 dataset for different models trained using Equilibrium Propagation (EP) and Implicit Differentiation (ID). The models vary in the number of layers (L) and block sizes (bs), which represent how many layers are grouped into one energy-based block. The table shows the performance (top-1 accuracy) and computation speed (WCT) for different model configurations. The results highlight the impact of model architecture on both performance and computational efficiency.

This table presents the results of validation accuracy and wall clock time (WCT) on CIFAR-10 dataset for different models trained using Equilibrium Propagation (EP) and Implicit Differentiation (ID). The models vary in the number of layers (L) and the number of blocks (‘bs’), allowing for an analysis of how different model architectures affect performance and computational efficiency. The use of 3 seeds ensures a more reliable estimate of performance.

This table presents the results of validation accuracy and wall clock time on CIFAR-10 dataset using two different algorithms, EP (Alg. 2) and ID. The experiments varied the total number of layers (L) in the model and the size of the blocks (bs) used in the feedforward-tied energy-based model (ff-EBM). Three different seeds were used for each configuration to assess the reproducibility and stability of the results.

This table presents the results of validation accuracy and wall clock time on CIFAR-10 dataset for different configurations of the proposed Feedforward-tied Energy-based Models (ff-EBMs). The configurations vary in the total number of layers (L) and the number of blocks the model is split into (bs). It compares the performance of the proposed Equilibrium Propagation (EP) algorithm (Alg. 2) with Implicit Differentiation (ID). The results demonstrate that EP achieves similar or better accuracy than ID across various configurations and exhibits a significant reduction in wall clock time with smaller block sizes. This shows that ff-EBMs can scale with smaller block sizes while maintaining performance.

This table shows the validation accuracy and wall clock time for CIFAR-10 using two different algorithms (EP and ID) and varying the number of layers and block sizes in the model. Three separate seeds were used for each configuration to provide a measure of statistical reliability. The results demonstrate how the performance and computation time change as the model’s architecture is altered.

Full paper#