↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current diffusion model inference methods, like DDPM, discretize the reverse diffusion process into numerous small steps, leading to slow inference. This is inefficient and motivates research for faster alternatives. The core issue is the imbalance in the complexity of subproblems within these methods; simple subproblems require many steps, while more complex ones could potentially achieve faster convergence with fewer steps.

This paper introduces the Reverse Transition Kernel (RTK) framework to address this. RTK allows a more balanced decomposition of the process into fewer, strongly log-concave subproblems. It then leverages efficient sampling algorithms (Metropolis-Adjusted Langevin Algorithm and Underdamped Langevin Dynamics) to solve these subproblems. This results in RTK-MALA and RTK-ULD, algorithms that significantly improve the convergence rate for diffusion inference, backed by theoretical guarantees.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in diffusion models because it proposes a novel framework that significantly accelerates inference by improving the convergence rate. It introduces new algorithms with theoretical guarantees, surpassing existing methods, and opens avenues for more efficient generative modeling. This is particularly important given the increasing use of diffusion models in various applications.

Visual Insights#

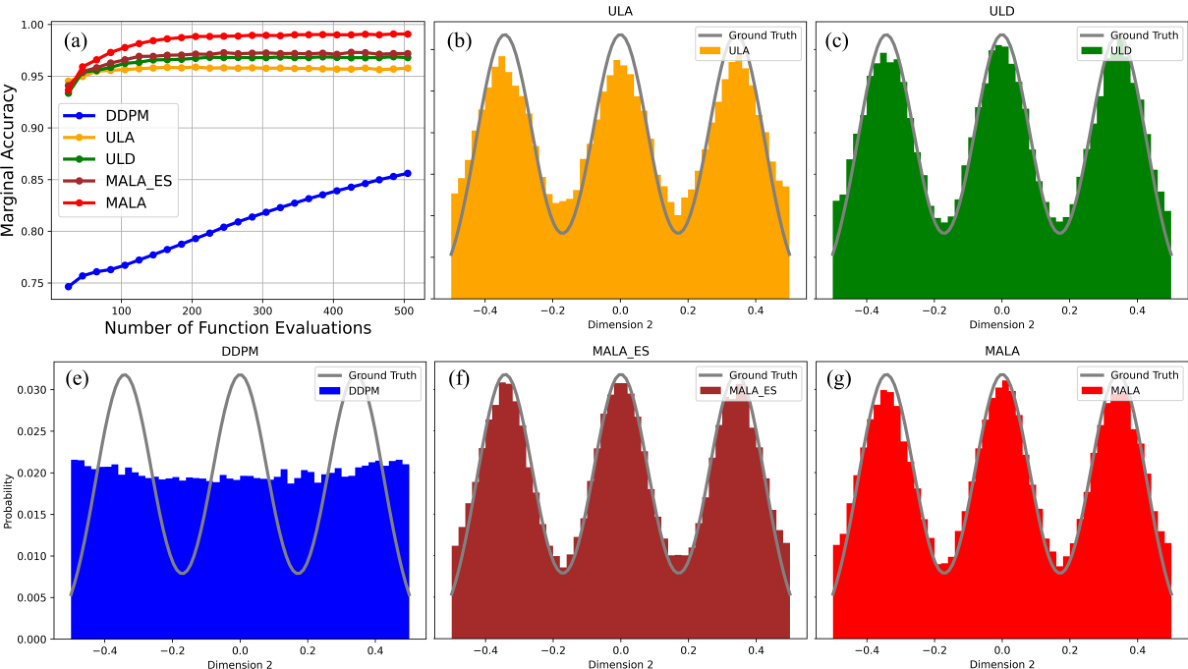

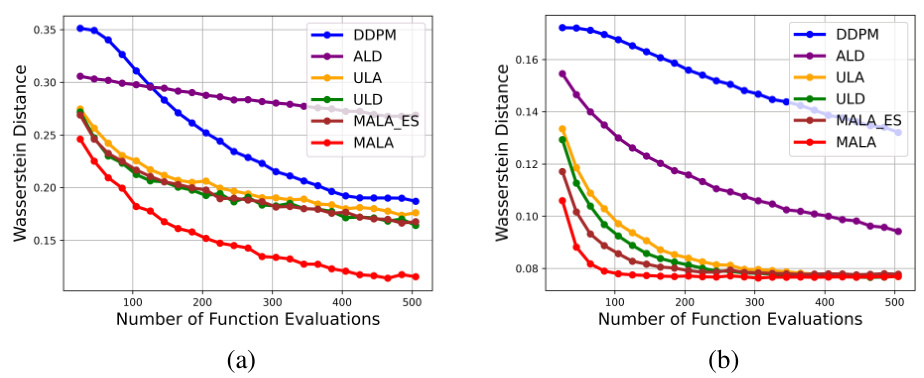

This figure compares the performance of various algorithms in sampling from a Mixture of Gaussian (MoG) distribution. Panel (a) shows the marginal accuracy of different sampling methods (DDPM, RTK-ULA, RTK-ULD, RTK-MALA, and score-only RTK-MALA) as a function of the number of function evaluations (NFE). Panels (b) through (f) display histograms of samples generated by each method, projected onto the second dimension (with the first dimension restricted to a specific range), showing the ability of the algorithms to capture the complex multi-modal structure of the MoG.

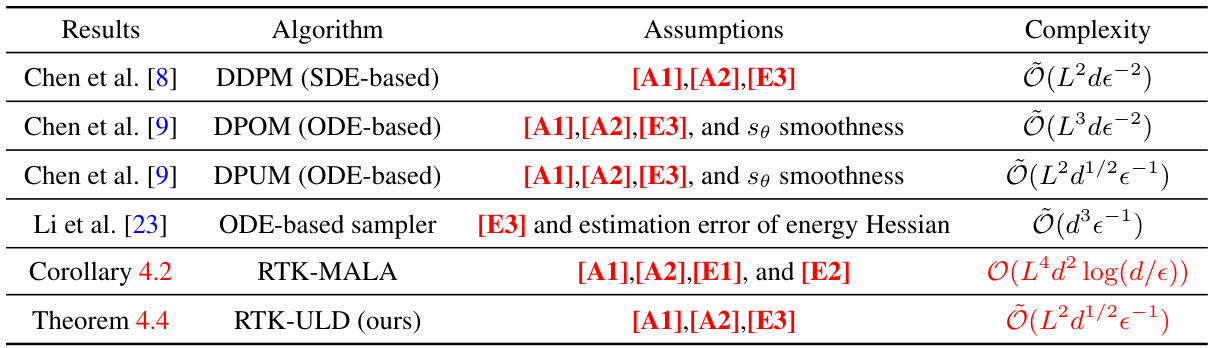

The table compares the proposed RTK-MALA and RTK-ULD algorithms with existing state-of-the-art methods for diffusion inference in terms of their computational complexity and theoretical guarantees. The comparison highlights the improved complexity and convergence rates achieved by the proposed methods under different assumptions on the score function and energy function estimation.

In-depth insights#

RTK Framework#

The Reverse Transition Kernel (RTK) framework presents a novel approach to diffusion model inference. Instead of relying on numerous small steps like DDPM, RTK strategically decomposes the denoising process into fewer, larger steps. Each step involves sampling from a strongly log-concave target distribution, which facilitates the use of efficient algorithms like MALA and ULD. This balanced decomposition leads to significantly faster convergence rates compared to traditional methods, improving both the speed and efficiency of diffusion inference. Theoretical analysis proves superior convergence bounds, highlighting RTK’s advantage in high-dimensional settings. The framework’s flexibility allows for exploring different subproblem decompositions, paving the way for future enhancements and optimizations.

MALA & ULD#

The research paper explores the use of Metropolis-Adjusted Langevin Algorithm (MALA) and Underdamped Langevin Dynamics (ULD) for efficient sampling within a novel Reverse Transition Kernel (RTK) framework for diffusion models. MALA is highlighted for its high accuracy, particularly with linear convergence under certain conditions, offering a significant advantage over existing methods like DDPM. ULD, on the other hand, is praised for its state-of-the-art convergence rate of Õ(d1/2ε-1), even under minimal data assumptions. The paper provides theoretical analyses for both algorithms demonstrating superior convergence rates compared to previous work, with RTK-ULD achieving the best dependence on dimensionality and target error. The algorithms are empirically evaluated, showing that RTK-MALA and RTK-ULD reconstruct fine-grained structures of complex target distributions better than DDPM, offering a promising advancement in diffusion model inference.

Convergence Rates#

Analyzing convergence rates in a research paper requires a nuanced understanding of the algorithms and methodologies employed. A key aspect is identifying the metric used to measure convergence, such as total variation (TV) distance or Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence. The choice of metric significantly influences the resulting rate. The paper likely explores different convergence rates for various algorithms, perhaps comparing a novel approach against existing baselines. A crucial aspect to consider is the dependence of the convergence rate on dimensionality (d) and the target accuracy (ε). Ideally, a faster algorithm would exhibit less dependence on d and a faster rate of decrease with improving ε. Theoretical bounds, derived through mathematical analysis, provide estimates of these rates; however, they often rely on specific assumptions about the underlying data distribution and algorithm properties. Finally, it is important to note that empirical results from experiments complement the theoretical analysis, providing a practical evaluation of the algorithms’ performance and convergence behavior, potentially highlighting discrepancies between theoretical predictions and real-world observations. Therefore, a comprehensive evaluation considers both theoretical bounds and empirical findings.

Empirical Results#

An Empirical Results section would ideally present a detailed comparison of the proposed method (RTK-MALA, RTK-ULD) against existing state-of-the-art techniques. This would involve quantitative metrics such as Total Variation (TV) distance and marginal accuracy, evaluating performance across multiple datasets (MoG, MNIST). The results should clearly demonstrate the superiority of the RTK framework in terms of both accuracy and computational efficiency (NFE). Visualizations like histograms, cluster plots, and generated samples would strengthen the findings by providing qualitative insights into the model’s capabilities. A discussion of the trade-off between accuracy and computational cost is crucial, showcasing scenarios where RTK methods excel and contexts where other approaches might prove more suitable. Analyzing the impact of hyperparameter choices and the robustness of the methods to variations in datasets would further enhance the analysis.

Future Work#

The paper’s lack of a dedicated ‘Future Work’ section is notable. However, several directions for future research are implied. Extending the theoretical analysis to encompass a wider range of diffusion models and data distributions is crucial. Currently, the theoretical guarantees rely on specific assumptions about the score function and data distribution. Relaxing these assumptions and evaluating performance on more diverse data would strengthen the framework’s applicability. Empirical validation on larger-scale datasets, potentially comparing against a broader set of state-of-the-art methods, is needed to definitively assess the practical performance gains of the proposed RTK framework. While the numerical experiments are promising, extensive testing is needed for real-world impact. Finally, investigating alternative MCMC methods for solving the RTK sampling subproblems could further optimize the inference process. Exploring and comparing different MCMC algorithms beyond MALA and ULD could reveal even faster or more stable methods, especially in high-dimensional settings. The focus on score-based diffusion models also presents an opportunity to explore its application with other generative model frameworks, potentially opening new avenues for improved sample generation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

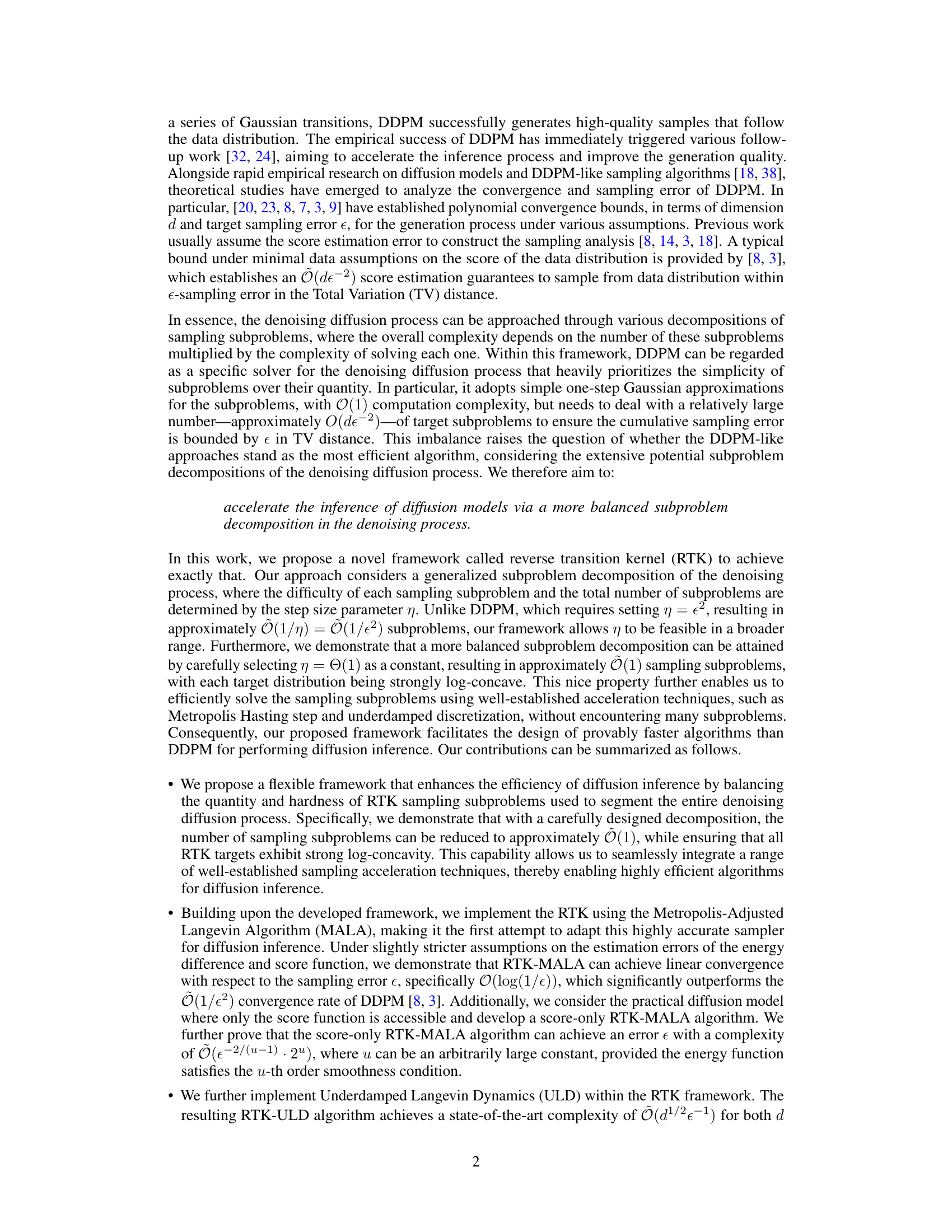

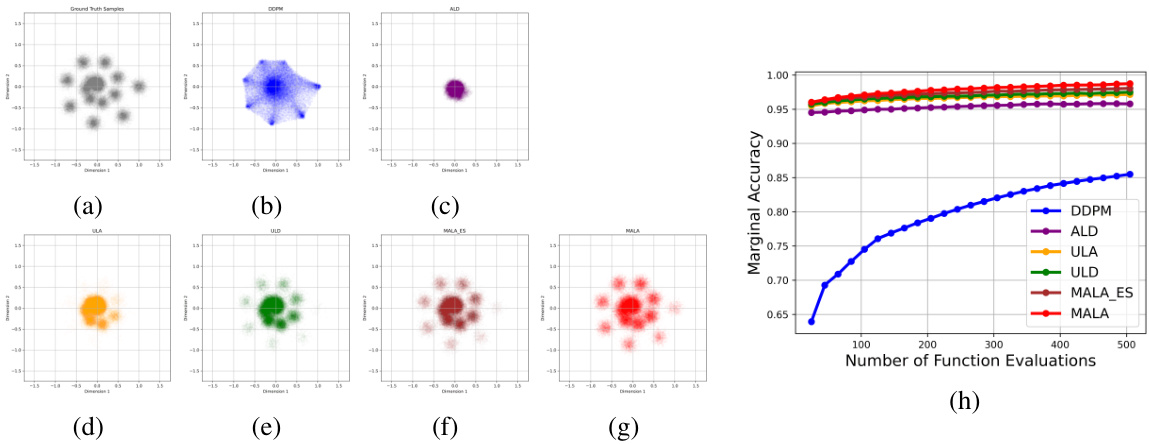

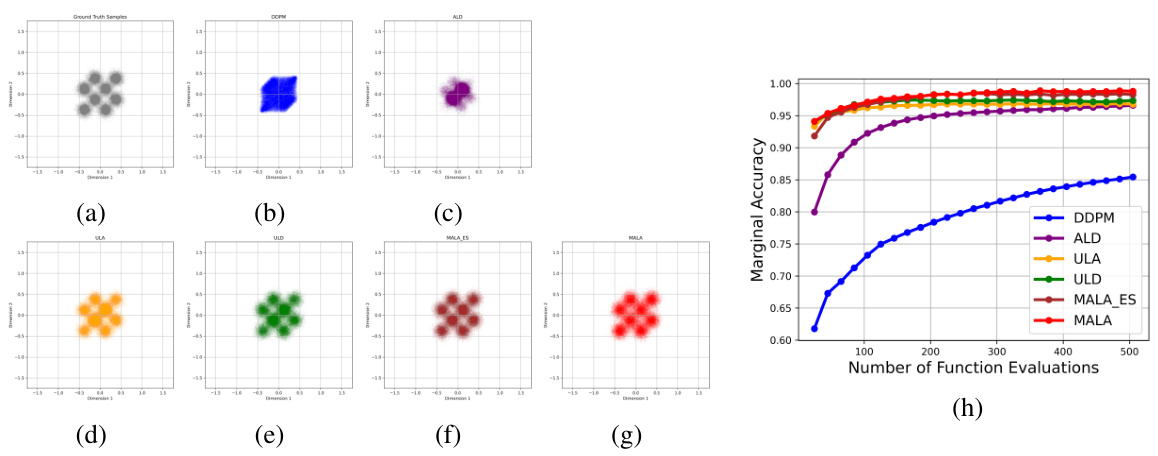

This figure compares the clustering results of different sampling methods, including DDPM, RTK-ULA, RTK-ULD, score-only RTK-MALA, and RTK-MALA, on a 10-dimensional Mixture of Gaussian (MoG) dataset. The results are projected onto the first two dimensions for visualization. The figure shows that RTK-based methods, especially RTK-MALA, outperform DDPM in reconstructing the complex structure of the MoG distribution, particularly in low-probability regions. The ground truth distribution is also shown for comparison.

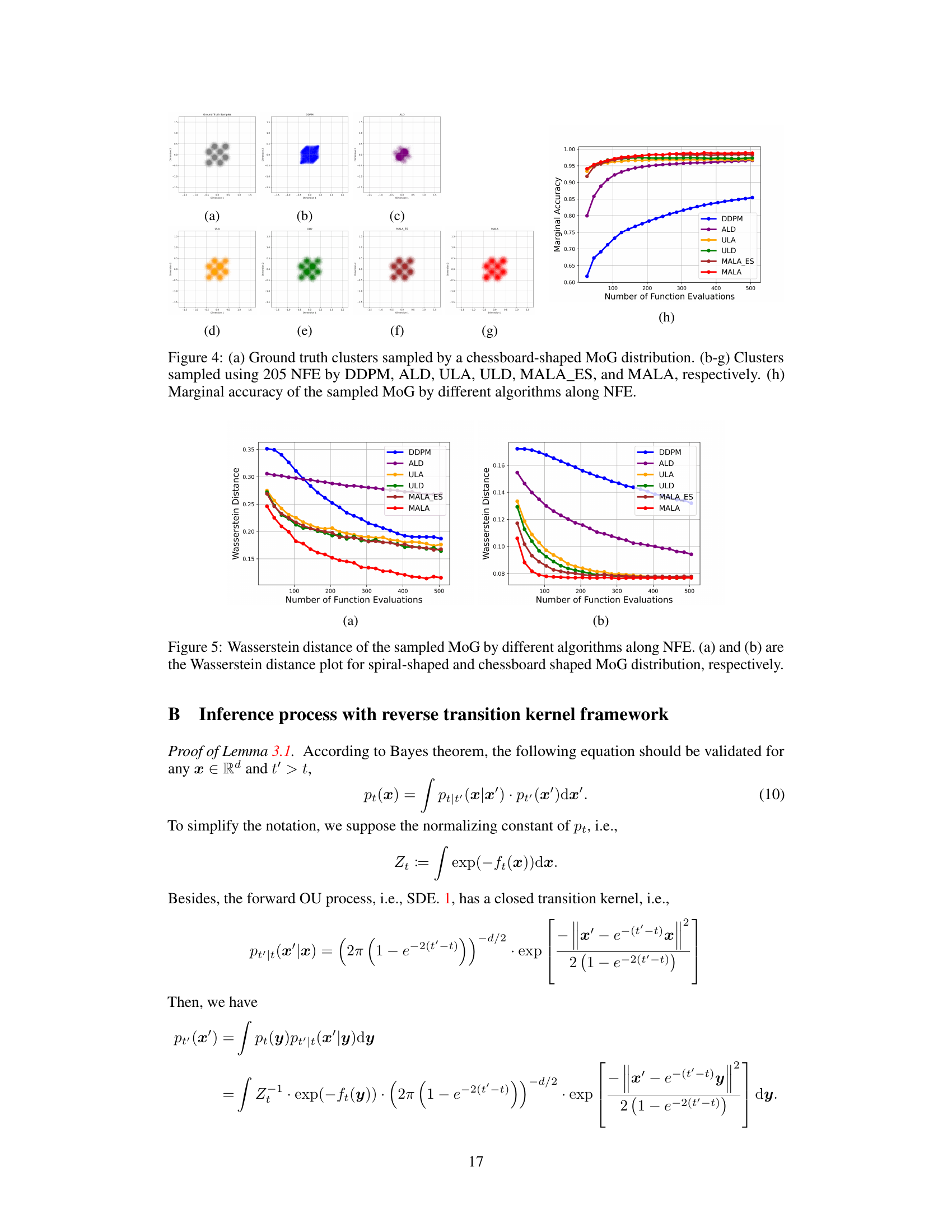

This figure compares the performance of different sampling algorithms (DDPM, RTK-ULA, RTK-ULD, RTK-MALA, and score-only RTK-MALA) on a Mixture of Gaussian (MoG) dataset. Subfigure (a) shows the marginal accuracy of each algorithm as a function of the number of function evaluations (NFE). Subfigures (b-f) display histograms of the sampled data along specific dimensions of the MoG, visualizing the algorithms’ ability to capture the complex structure of the MoG distribution. The results show that RTK-based methods significantly outperform DDPM, especially in accurately reconstructing the ground truth distribution, particularly in low-probability regions.

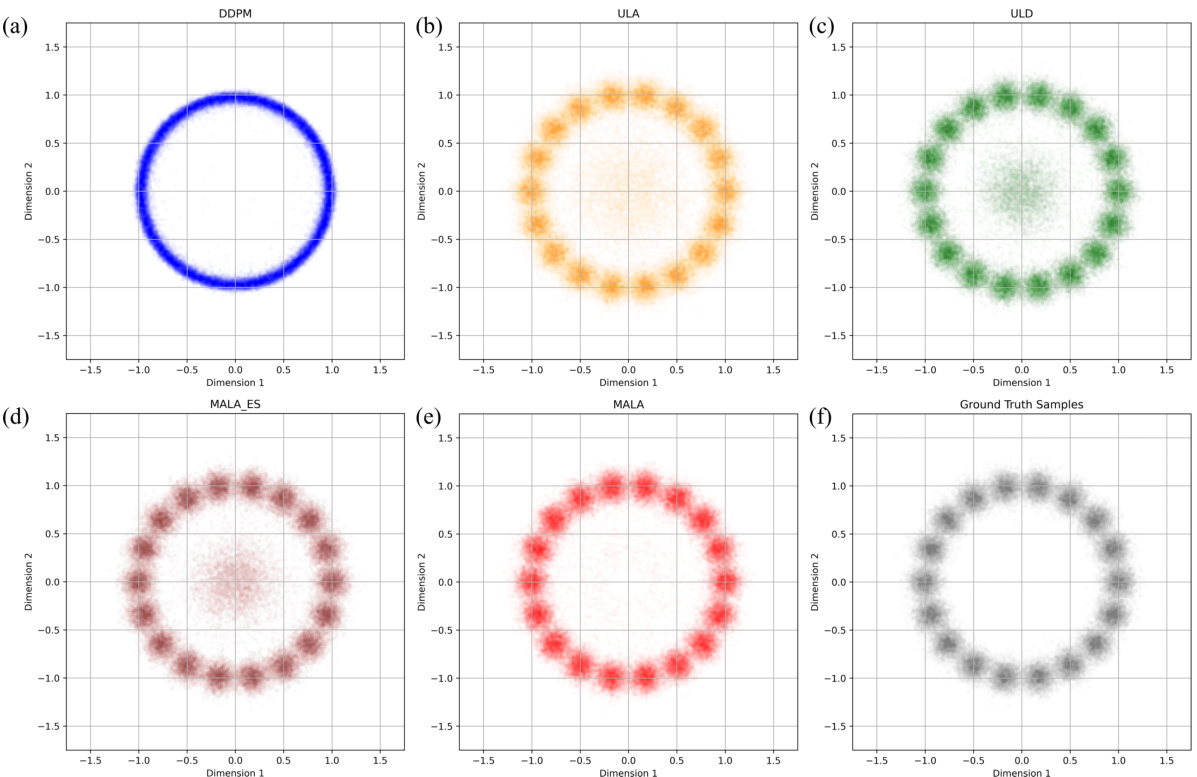

Figure 1(a) shows the marginal accuracy of different sampling algorithms (DDPM, RTK-ULA, RTK-ULD, RTK-MALA, and score-only RTK-MALA) along the number of function evaluations. The rest of the figure (Figure 1(b-f)) displays the histograms of the sampled MoG (Mixture of Gaussian) by the algorithms along a specific direction. In the histograms, the first dimension is constrained within (0.75, 1.25) and the second dimension is shown.

This figure compares the performance of various sampling algorithms on a Mixture of Gaussian (MoG) dataset. Panel (a) shows the marginal accuracy of each algorithm as a function of the number of function evaluations (NFE). Panels (b-f) display histograms of the sampled data, demonstrating how well the algorithms recover the true underlying MoG distribution along different dimensions. RTK-based algorithms demonstrate better performance than the baseline DDPM algorithm.

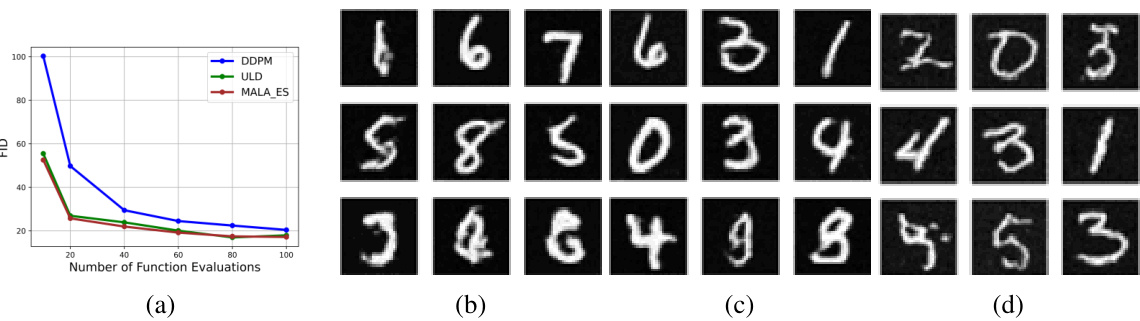

This figure compares the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) scores of MNIST image samples generated by different algorithms (DDPM, ULD, and score-only RTK-MALA). Part (a) shows the FID scores plotted against the number of function evaluations (NFEs), demonstrating the improved performance of the RTK-based methods. Parts (b), (c), and (d) display example MNIST digit images generated by each algorithm, respectively, using 20 NFEs. The images illustrate the visual quality differences between the methods.

Full paper#