↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Designing molecules with specific properties is challenging due to the vastness of chemical space. Existing latent space optimization (LSO) methods often decouple generation and optimization, leading to suboptimal performance and high computational costs. These methods also require additional inference models, increasing complexity.

The Latent Prompt Transformer (LPT) addresses these issues by integrating molecule generation and property optimization within a single framework. LPT uses a latent vector to decouple molecule generation and property prediction, allowing for efficient optimization in the latent space. LPT’s online learning algorithm progressively shifts the model distribution towards regions of desired properties, showcasing strong sample efficiency. The model’s effectiveness is validated across single/multi-objective, and structure-constrained optimization tasks, demonstrating its potential in drug discovery and material science.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in drug discovery and materials science. Its novel generative model, LPT, offers a unified framework for molecule generation and optimization, improving both computational and sample efficiency. This significantly advances current latent space optimization techniques, opening doors for more efficient and effective exploration of chemical space and the development of novel molecules with desired properties. Its online learning capabilities further enhance its practical applications in various optimization tasks.

Visual Insights#

This figure shows the distribution of docking scores (E) obtained using AutoDock-GPU at each iteration of the online learning process for the Latent Prompt Transformer (LPT) model. The x-axis represents the docking scores, and the y-axis implicitly represents the density of molecules with those scores. The color gradient represents the iteration number, showing how the distribution shifts towards higher docking scores (indicating better binding affinity) as the online learning progresses. This visualization demonstrates the model’s ability to effectively improve the binding affinity of generated molecules over time.

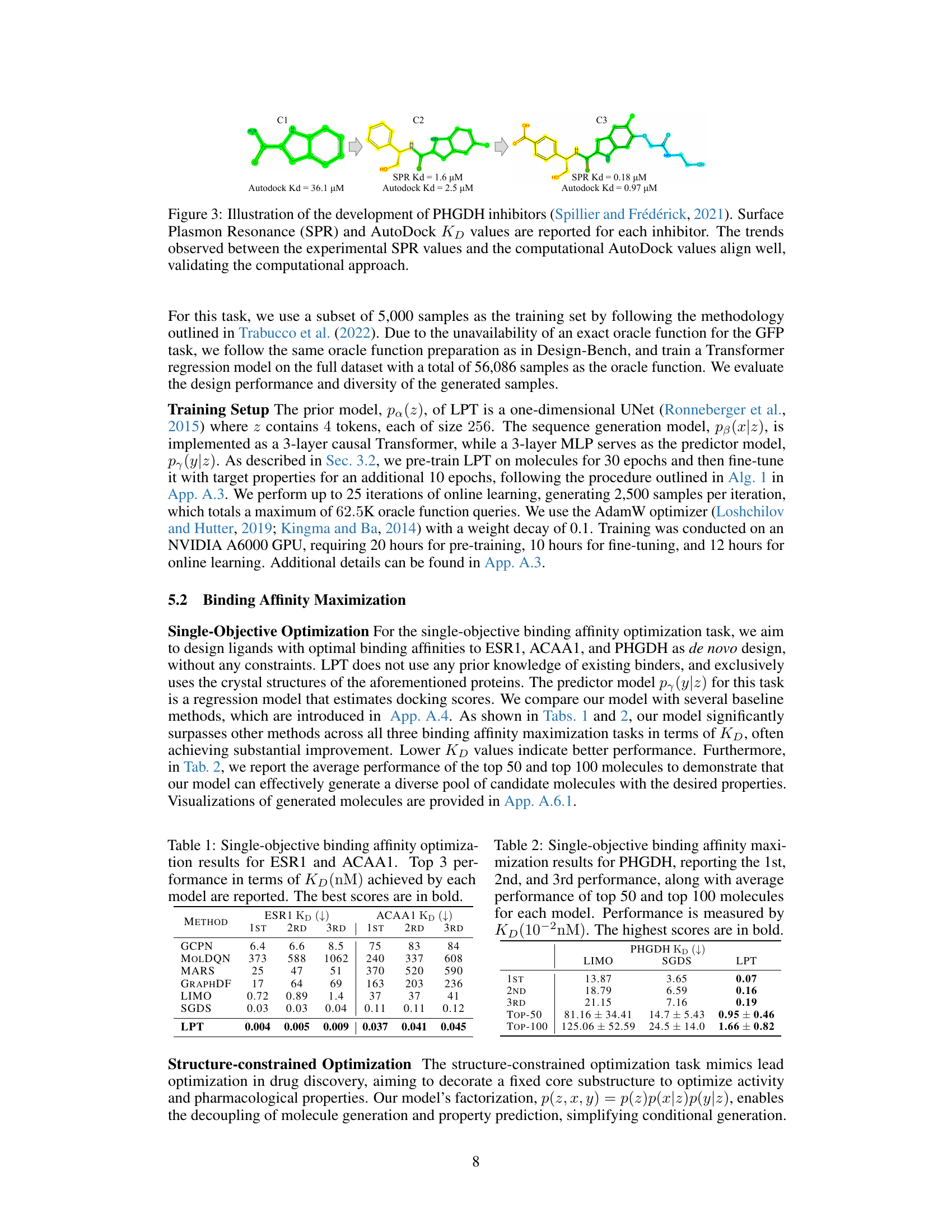

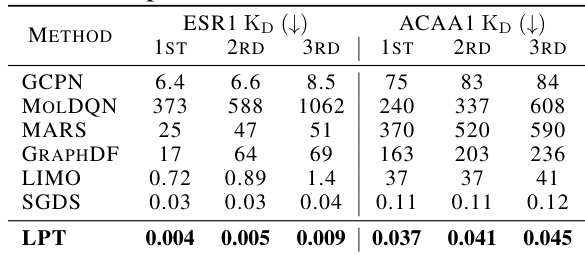

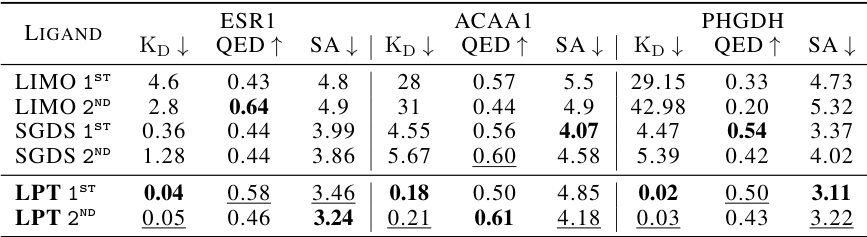

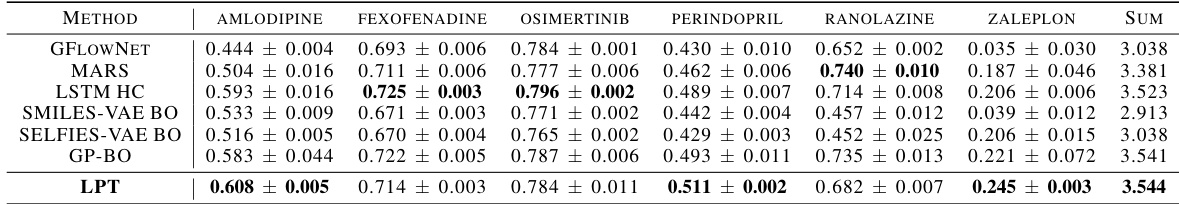

This table presents the top 3 KD (nM) values achieved by different machine learning models for single-objective binding affinity optimization tasks on two proteins: ESR1 and ACAA1. Lower KD values indicate stronger binding affinity, thus better performance. The models compared include GCPN, MolDQN, MARS, GraphDF, LIMO, SGDS, and the authors’ proposed model, LPT. The best performance for each model is highlighted in bold.

In-depth insights#

Latent Prompt Trans.#

The conceptualization of a ‘Latent Prompt Transformer’ (LPT) model for molecule design is intriguing. The core idea of using a latent vector as a ‘prompt’ to guide a causal Transformer for molecule generation is innovative, suggesting a powerful way to control the generative process. The unified framework, integrating generation and optimization in an end-to-end fashion, addresses limitations of traditional latent space optimization methods. Maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) is a clever choice for training, avoiding the need for separate inference networks and enhancing efficiency. The incorporation of an online learning algorithm to progressively adjust the model distribution, targeting desired properties, is another key strength, promising improved sample efficiency and adaptability to new objectives. However, further exploration into the generalizability and robustness of the LPT under various conditions, particularly with noisy or limited data, is essential to assess its broader utility. Investigating its scalability to significantly larger molecular spaces and complex multi-objective tasks remains a key area of future work.

Online Learning#

Online learning, in the context of this research paper, is presented as a crucial mechanism to overcome the limitations of traditional offline training methods for generative models. The core idea is to progressively adapt the model’s distribution towards regions in latent space that yield molecules with desired properties. This approach tackles a key challenge in molecular design, where offline models may struggle to generate molecules far removed from the training data. Instead of relying solely on a static dataset, online learning dynamically refines the model by incorporating newly generated molecules and their evaluated properties. This iterative process allows the model to explore regions of chemical space beyond the initial data distribution and thus discover novel molecules with improved characteristics. The process is described as a three-stage iterative cycle: (1) generation of new molecules based on desired properties through conditional sampling from the refined model, (2) evaluation of the generated molecules by using an oracle function that provides ground truth property values, and (3) retraining the model by updating its parameters using maximum likelihood estimation on the newly generated molecules. This continuous feedback loop allows for effective exploration of the complex chemical space and improves overall sample efficiency, especially when experimental evaluation of synthesized molecules is expensive and time-consuming.

Efficiency Analysis#

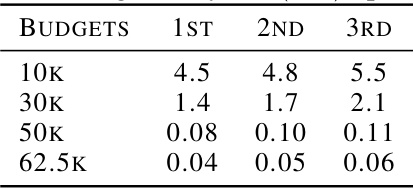

Efficiency analysis in this research paper focuses on both computational and sample efficiency within the context of molecule design. Computational efficiency centers on minimizing the time needed for training and inference, particularly within online learning where iterative MCMC sampling can be computationally expensive. Strategies to improve this are discussed, such as employing the Persistent Markov Chain method and reducing the number of MCMC steps. Sample efficiency emphasizes minimizing the number of costly oracle function calls (e.g., wet-lab experiments or docking simulations). The study explores how to enhance sample efficiency by guiding the learned model towards promising areas of the search space during generation and by prioritizing more informative samples during the online learning phase, demonstrating a trade-off between exploration and exploitation. The overall goal is to balance these two types of efficiency to suit the specific needs of the molecule design task, prioritizing computational efficiency for properties quickly assessed by software and sample efficiency for more time-consuming ones.

PHGDH Case Study#

A hypothetical ‘PHGDH Case Study’ in a molecule design paper would likely explore the application of novel machine learning methods to design molecules targeting Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH). The study might focus on PHGDH’s role in cancer, making it a relevant target for drug discovery. Researchers would likely compare their model’s performance against existing PHGDH inhibitors, demonstrating improvements in binding affinity or other relevant metrics. The case study might detail the use of techniques like structure-based drug design to guide the development process. Success would be measured by the model’s ability to discover novel, high-affinity PHGDH inhibitors, and the case study would analyze the structural features of these molecules to provide insights into the molecular mechanisms of PHGDH inhibition. Sample efficiency and computational efficiency would likely be key aspects of the evaluation, showing the model’s ability to produce results quickly and with minimal experimental resources. Finally, the study might compare its generated molecules with those designed by human experts, showcasing the potential of the approach and revealing any unique design strategies discovered.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore enhanced model architectures beyond the Transformer design, potentially leveraging graph neural networks or other methods better suited to capturing molecular structure and properties. Investigating alternative training paradigms such as reinforcement learning or evolutionary algorithms could unlock further improvements in sample efficiency and optimization performance. A key area for development is robustness against noisy or incomplete data, making the design process more practical for real-world applications where perfect information isn’t always available. Finally, the application of the Latent Prompt Transformer (LPT) to a broader range of chemical and biological design problems warrants investigation, exploring its potential in materials science, protein engineering, and other fields requiring generative design approaches. Benchmarking against a wider variety of state-of-the-art methods across diverse design tasks is also essential for comprehensively evaluating LPT’s capabilities and identifying its strengths and weaknesses relative to established techniques.

More visual insights#

More on figures

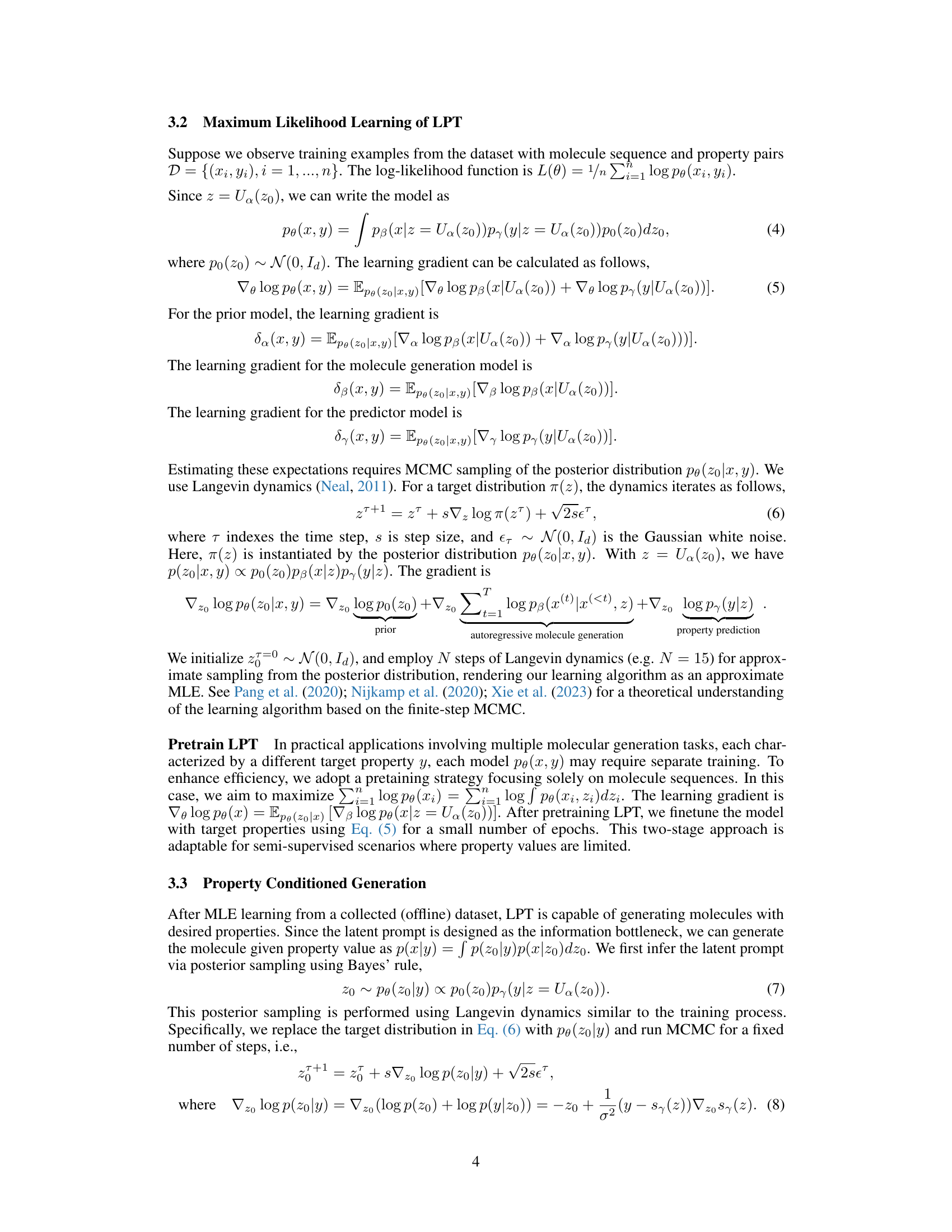

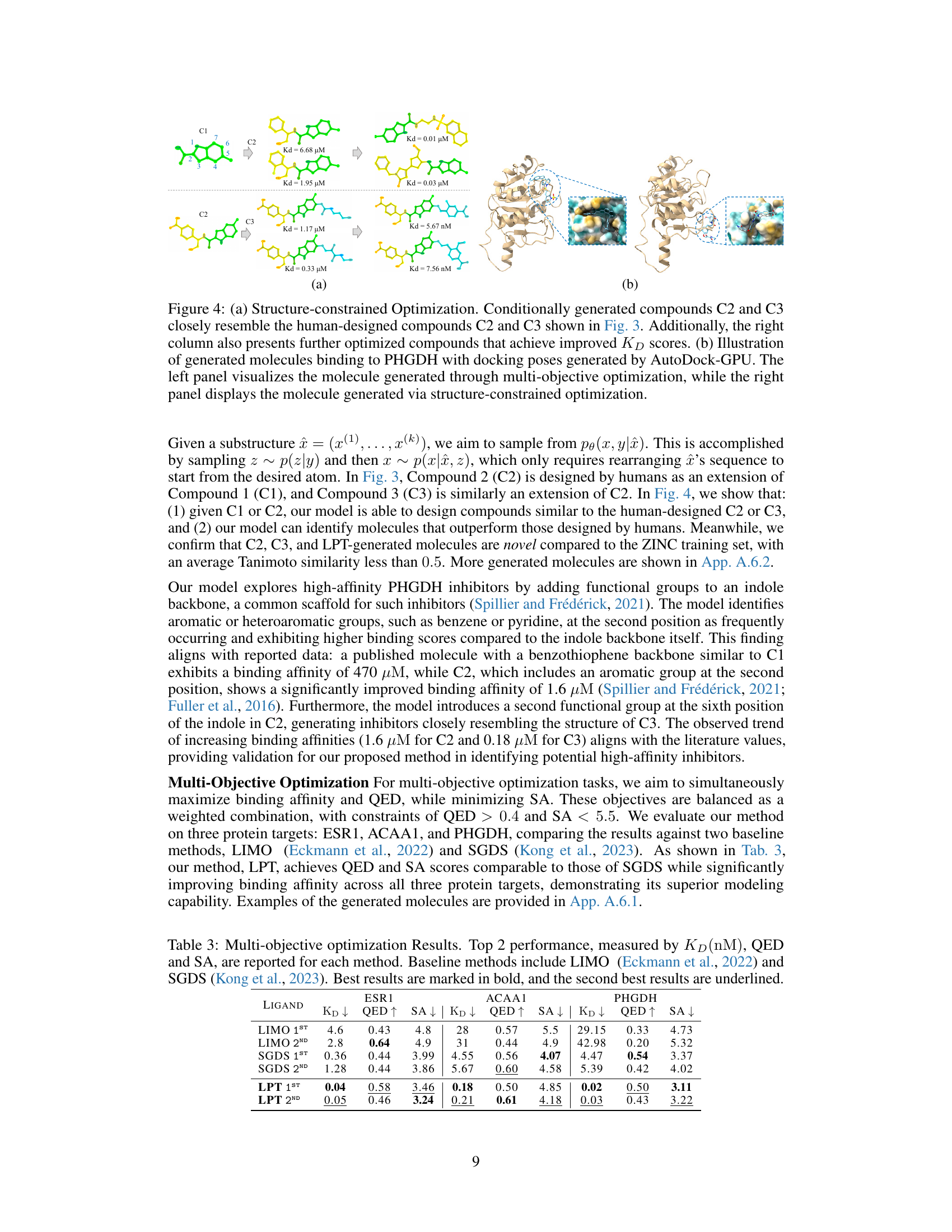

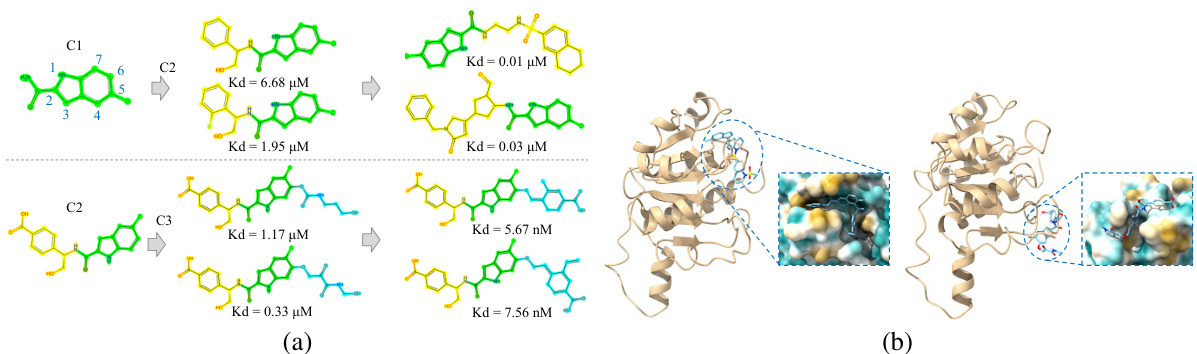

This figure demonstrates the results of structure-constrained optimization and multi-objective optimization for PHGDH. Part (a) shows how the model generates molecules (C2 and C3) similar to human-designed ones, and further optimizes them to achieve improved KD scores (a measure of binding affinity). Part (b) visualizes the binding poses of generated molecules to the PHGDH protein using AutoDock-GPU. The left panel showcases the molecule from multi-objective optimization, while the right shows one from structure-constrained optimization.

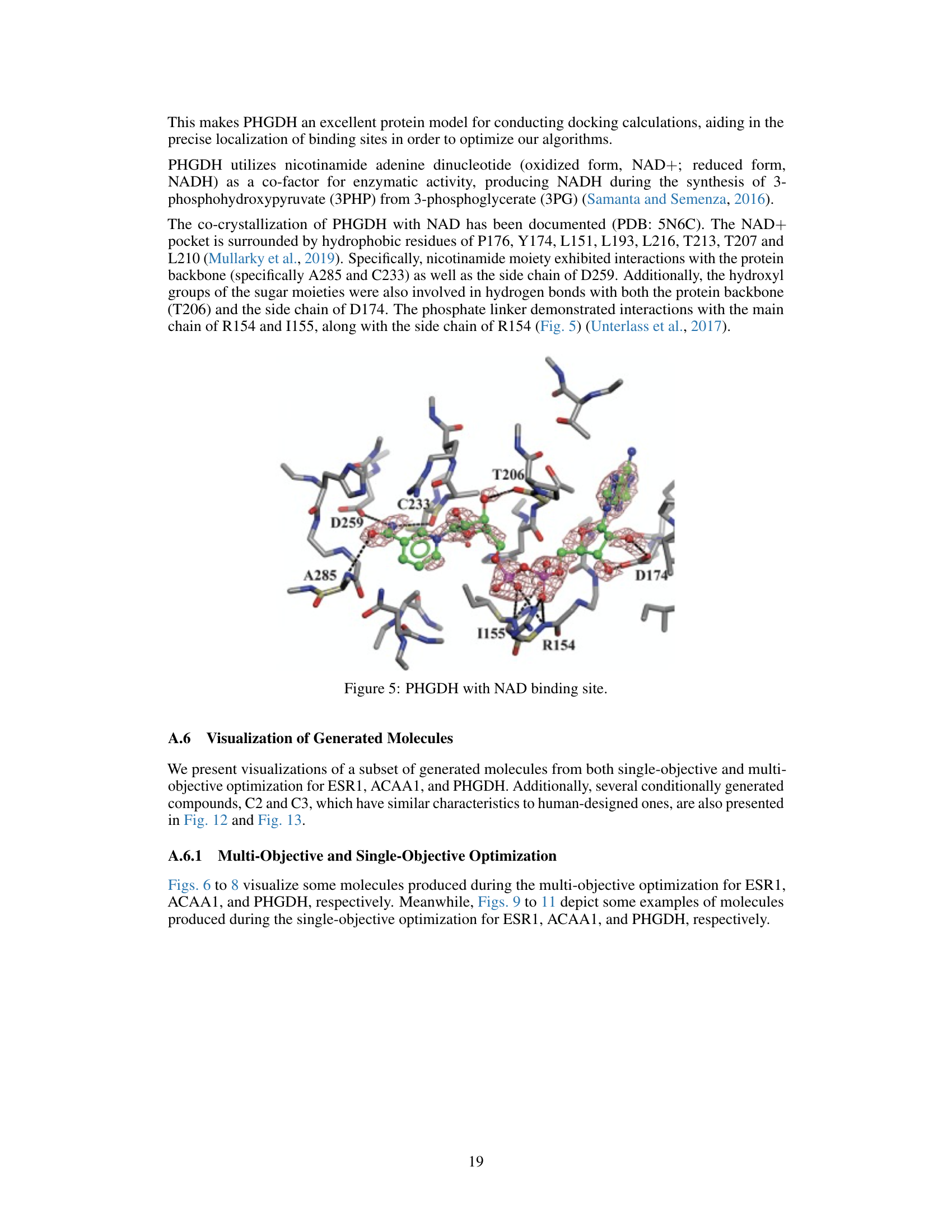

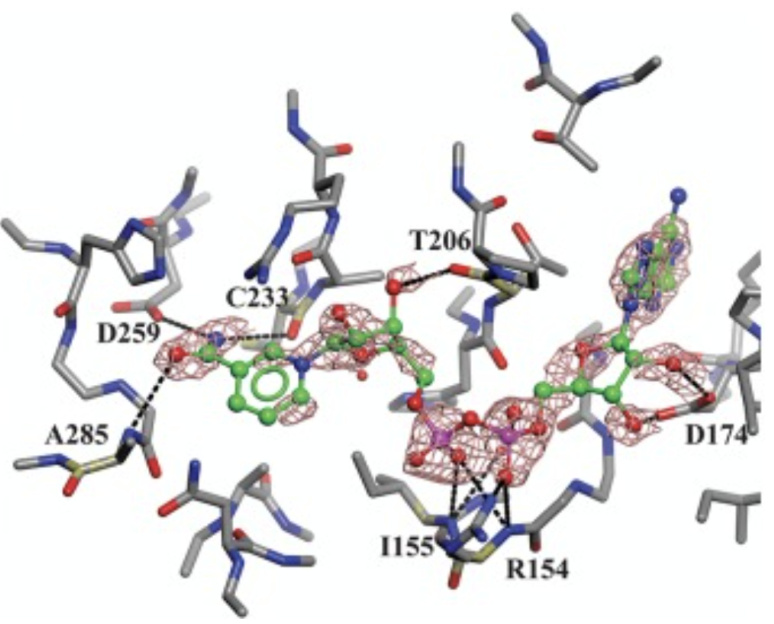

This figure shows the binding site of NAD+ to the Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH) enzyme. Key residues involved in the interaction are highlighted, including hydrophobic residues (P176, Y174, L151, L193, L216, T213, T207, L210) and interactions with the nicotinamide moiety (A285, C233, D259), sugar moieties (T206, D174), and phosphate linker (R154, I155). The figure illustrates the complex three-dimensional interactions that contribute to the binding affinity of NAD+ to PHGDH.

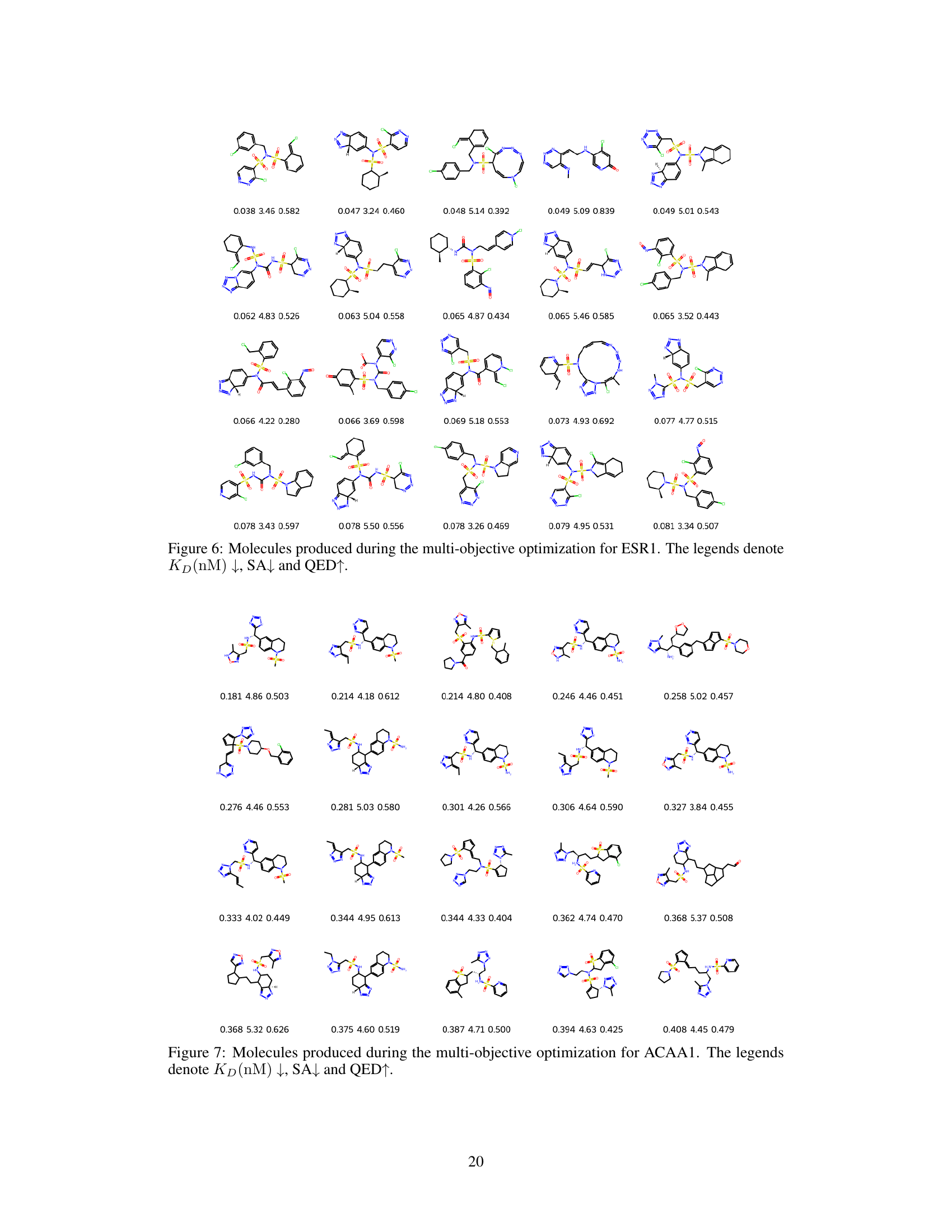

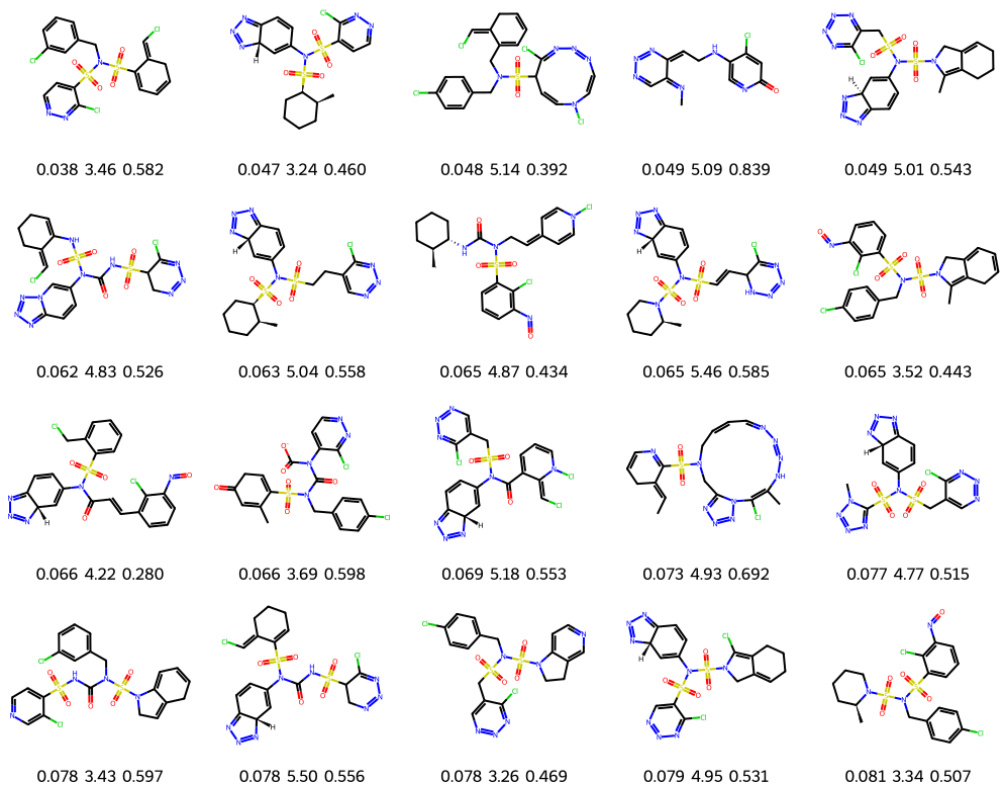

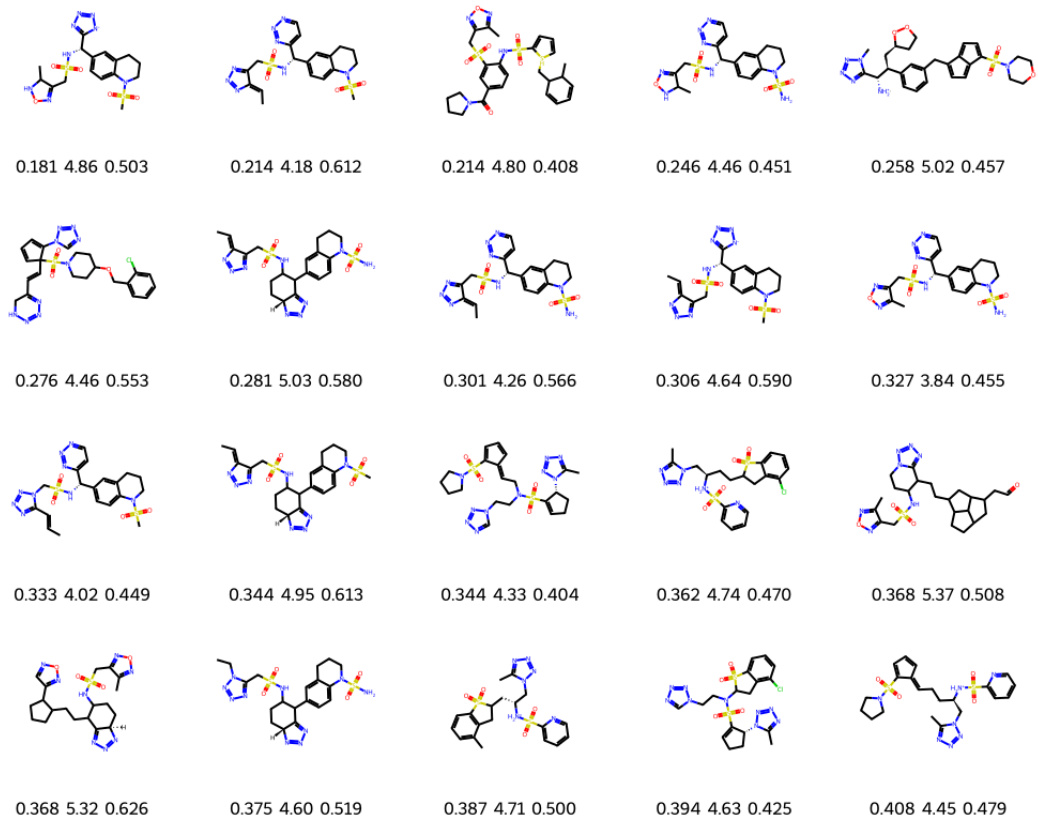

This figure shows 20 molecules generated by the Latent Prompt Transformer (LPT) model during a multi-objective optimization process targeting the Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH) protein. The optimization aimed to minimize the dissociation constant (KD, a measure of binding affinity), minimize the synthetic accessibility score (SA), and maximize the quantitative estimate of drug-likeness (QED). Each molecule is depicted with its corresponding KD (nM), SA, and QED values. The figure illustrates the model’s capability to discover diverse molecules with favorable properties.

This figure shows the results of structure-constrained optimization and multi-objective optimization for PHGDH. (a) shows that the model can generate molecules similar to those designed by humans and even improve upon them. (b) illustrates the docking poses of molecules generated by both methods, highlighting the differences in binding.

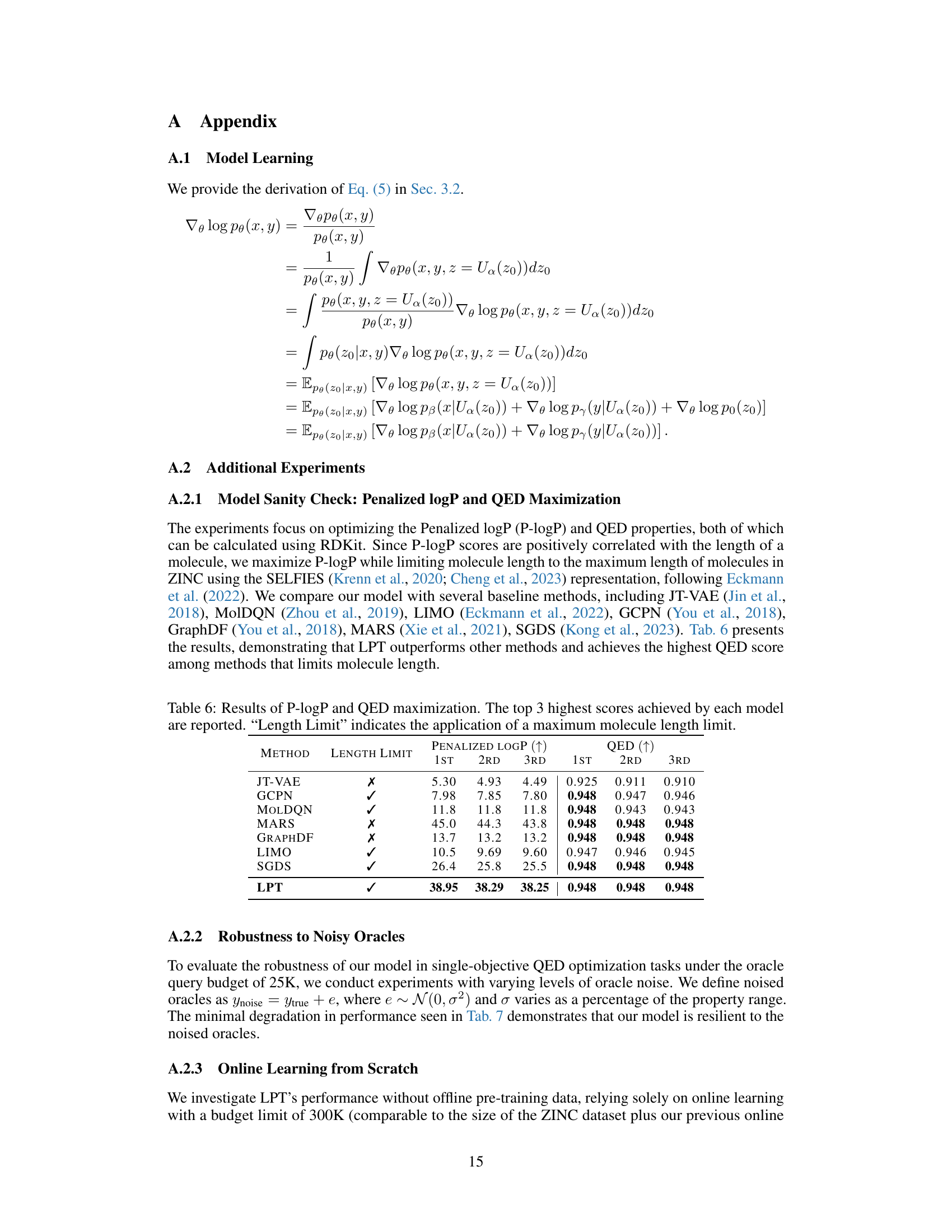

The figure shows the architecture of the Latent Prompt Transformer (LPT) model. The left panel illustrates the overall model, highlighting the three main components: a learnable prior for a latent vector (z), a molecule generation model (PB(x|z)) that uses the latent vector as a prompt, and a property prediction model (py(y|z)) that predicts the molecule’s properties based on the latent vector. The right panel provides a detailed view of the molecule generation model, emphasizing the use of the latent vector (z) as a prompt via cross-attention in the causal Transformer architecture.

The figure shows the architecture of the Latent Prompt Transformer (LPT), a generative model for molecule design. The left panel illustrates the overall model, highlighting three components: a latent vector z with a learnable prior, a molecule generation model pβ(x|z) based on a causal Transformer that uses z as a prompt, and a property prediction model py(y|z) that estimates the target property values given the latent prompt. The right panel shows a zoomed-in view of the molecule generation model, illustrating how the latent vector z is used as a prompt via cross-attention.

The figure illustrates the architecture of the Latent Prompt Transformer (LPT), a generative model for molecule design. The LPT consists of three main components: a latent vector with a learnable prior distribution (left panel), a molecule generation model based on a causal Transformer that uses the latent vector as a prompt (right panel), and a property prediction model that predicts the molecule’s properties using the latent prompt. The left panel shows how the latent vector z is generated from a neural transformation of Gaussian noise, while the right panel shows how the latent vector is used as a prompt for the molecule generation model via cross-attention, guiding the autoregressive generation process.

The figure shows the architecture of the Latent Prompt Transformer (LPT) model. The left panel depicts the overall model, showing the three main components: a latent vector with a learnable prior distribution (z), a molecule generation model based on a causal Transformer that uses the latent vector as a prompt (PB(x|z)), and a property prediction model that predicts the molecule’s properties using the latent prompt (py(y|z)). The right panel zooms in on the molecule generation model, illustrating how the latent vector z is used as a prompt via cross-attention.

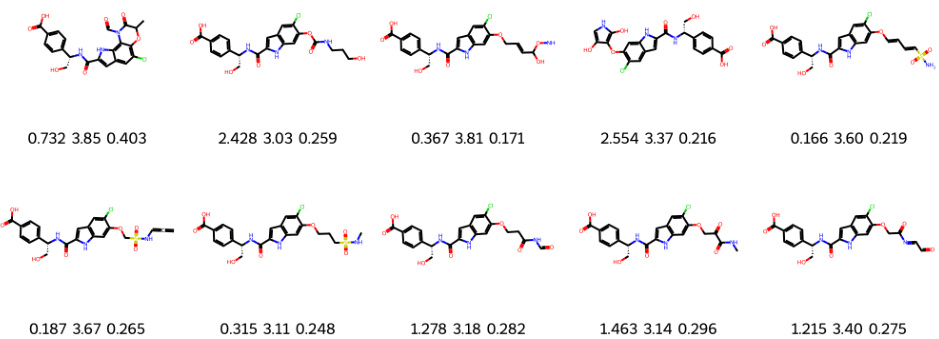

This figure shows molecules generated by a structure-constrained optimization process. Starting from a core structure (C1), the model generated molecules (C2) aiming to improve binding affinity (KD), while maintaining other desirable properties. The figure shows the generated molecules with their corresponding KD values, synthetic accessibility scores (SA), and quantitative estimate of drug-likeness (QED). Lower KD values indicate stronger binding affinity. Lower SA values indicate easier synthesis. Higher QED values indicate better drug-likeness.

This figure shows molecules generated by structure-constrained optimization. The optimization started with a core structure (C1) and aimed to generate molecules similar to a human-designed molecule (C2) while improving binding affinity to the PHGDH protein. KD represents the dissociation constant (lower is better), SA is the synthetic accessibility score (lower is better), and QED is a measure of drug-likeness (higher is better). The figure visually demonstrates the structural similarity between the generated molecules and the target molecule (C2), highlighting the success of the structure-constrained optimization approach.

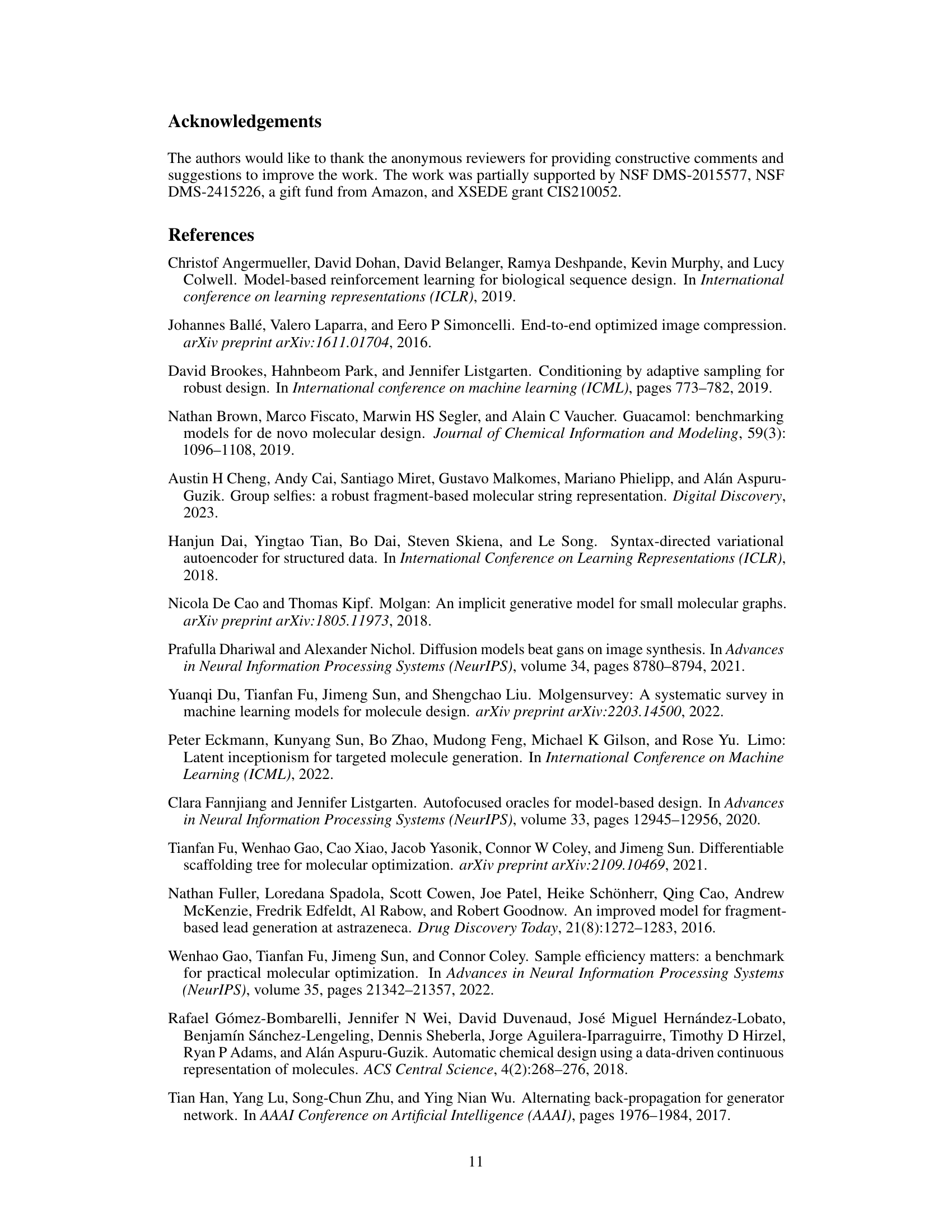

More on tables

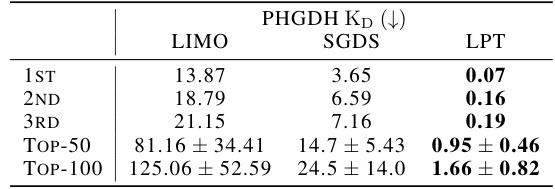

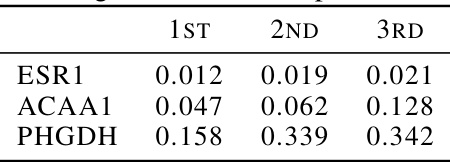

This table presents the results of single-objective binding affinity maximization for the PHGDH protein. It compares the performance of three different models (LIMO, SGDS, and LPT) in terms of the dissociation constant KD (in nanomolar units), which is a measure of binding affinity. Lower KD values indicate stronger binding. The table shows the top 3 KD values achieved by each model, as well as the average KD for the top 50 and top 100 molecules generated by each model. The LPT model demonstrates significantly better performance than the other two models, achieving substantially lower KD values.

This table presents the results of single-objective binding affinity optimization experiments on two proteins, ESR1 and ACAA1. Three different models (GCPN, MOLDQN, MARS, GraphDF, LIMO, SGDS, and LPT) were evaluated. The table displays the top three lowest KD (dissociation constant) values obtained by each model. Lower KD values indicate better binding affinity. The best performance for each model is highlighted in bold. This shows a comparison of the models’ capabilities in identifying molecules that strongly bind to their target proteins.

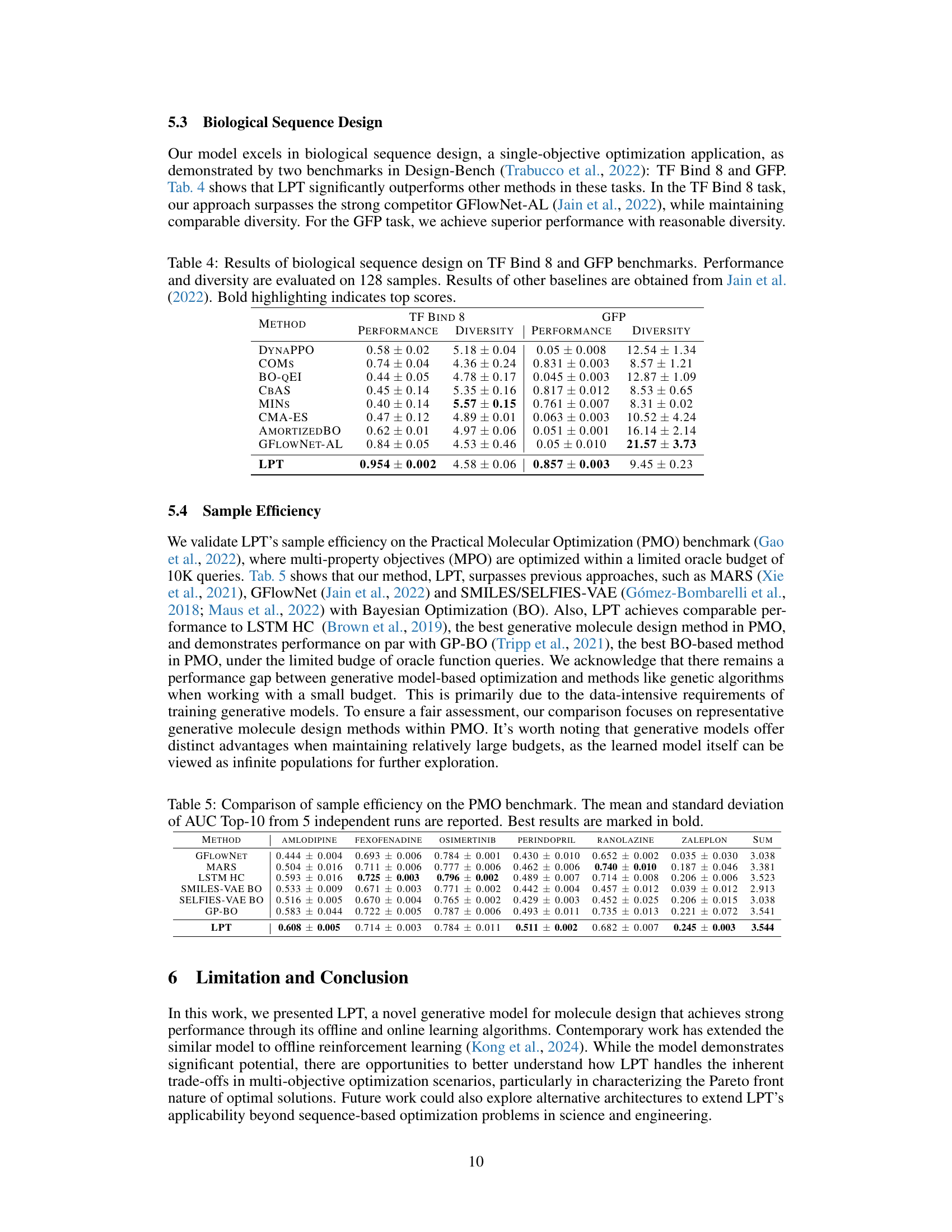

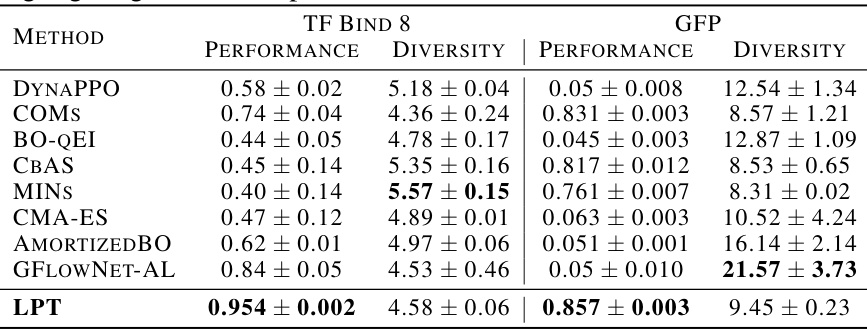

This table presents the results of applying the Latent Prompt Transformer (LPT) model to two biological sequence design tasks: TF Bind 8 and GFP, as found in the Design-Bench benchmark. It compares the LPT model’s performance and sequence diversity against several other state-of-the-art baselines. The performance metric is task-specific (higher is better), and diversity measures the variation within the generated sequences. Results from other methods are taken from a cited prior work (Jain et al., 2022). The table highlights LPT’s superior performance in both tasks.

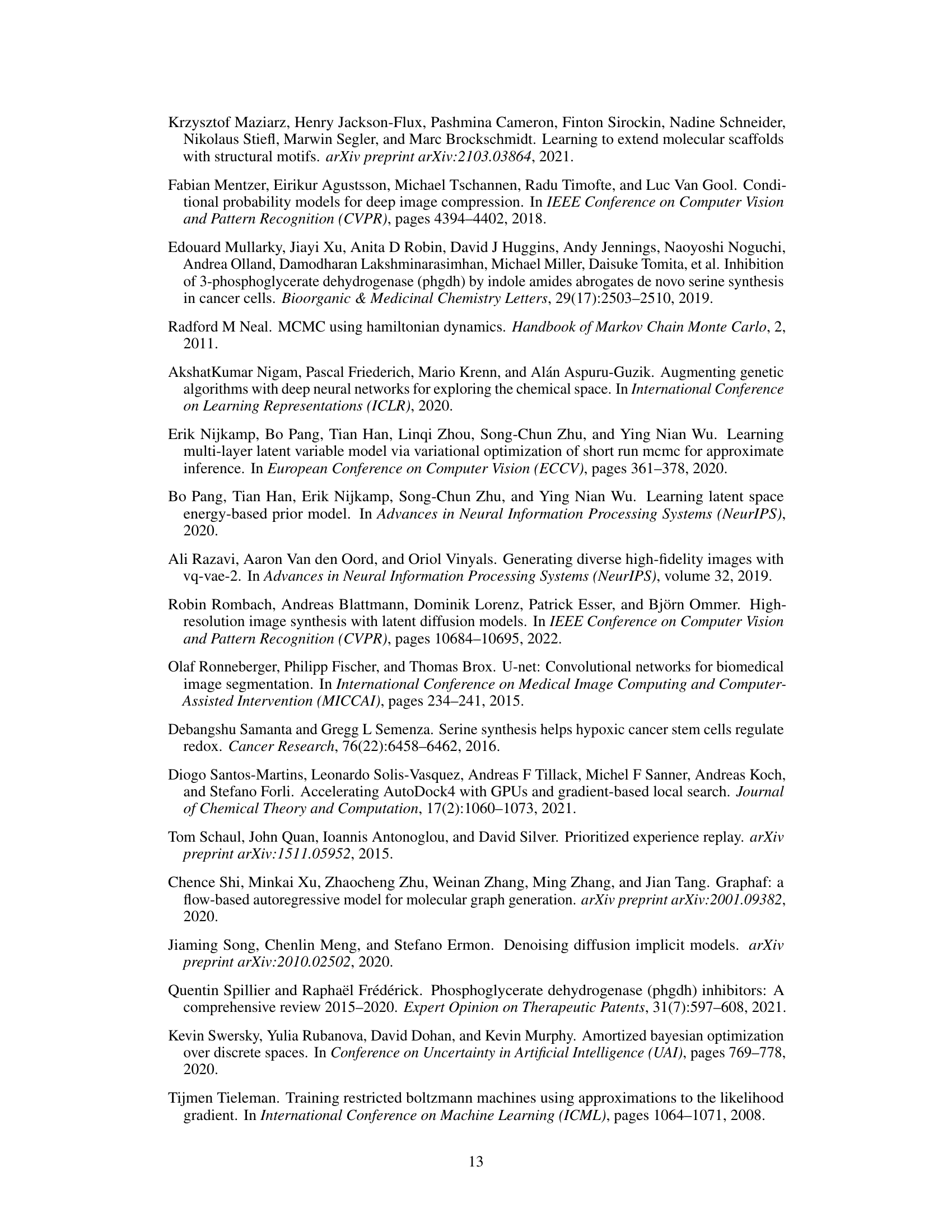

This table compares the sample efficiency of different methods on the Practical Molecular Optimization (PMO) benchmark. The benchmark involves optimizing multiple properties within a limited oracle budget (10k queries). The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the Area Under the Curve (AUC) for the top 10 molecules for each method, across five independent runs. The best performing method for each molecule is highlighted in bold.

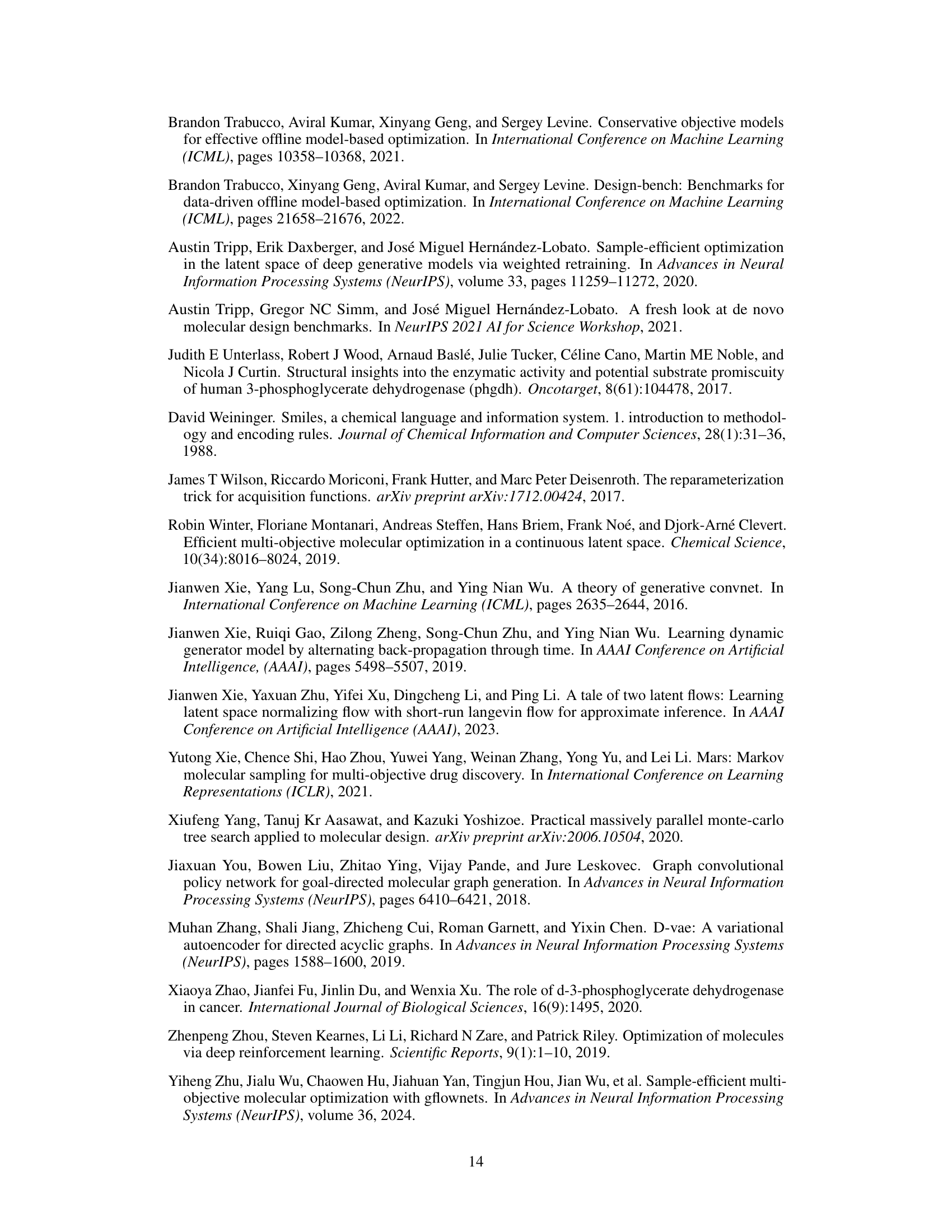

This table presents the results of maximizing the Penalized logP (P-logP) and QED properties of molecules, comparing the performance of various models (including JT-VAE, GCPN, MolDQN, MARS, GraphDF, LIMO, SGDS, and LPT). The table indicates whether a maximum length limit was applied for each model and shows the top three scores obtained for both P-logP and QED. LPT demonstrates superior performance on both metrics.

This table presents the results of single-objective QED optimization experiments conducted under various levels of oracle noise. The results demonstrate the robustness of the model, as its performance degrades only minimally even with significant noise levels.

This table presents the top three KD (nanomolar) values obtained for three different proteins (ESR1, ACAA1, and PHGDH) using an online learning approach from scratch. KD values represent binding affinity; lower values indicate stronger binding. This demonstrates the model’s performance when trained only with online learning, without any offline pre-training data.

This table presents the results of ablation studies conducted to evaluate the impact of different components of the Latent Prompt Transformer (LPT) model on its performance. The experiments were carried out for a single-objective optimization task focusing on the PHGDH protein target. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the dissociation constant (KD) for the top 100 unique molecules generated in the final iteration of the online learning process for different model variations. Each row represents a different model variation obtained by removing or modifying specific components of the original LPT model. By comparing the KD values across these variations, the importance of each component can be assessed. The results highlight the contribution of each component to the overall model performance and provide insights into the design of the LPT model.

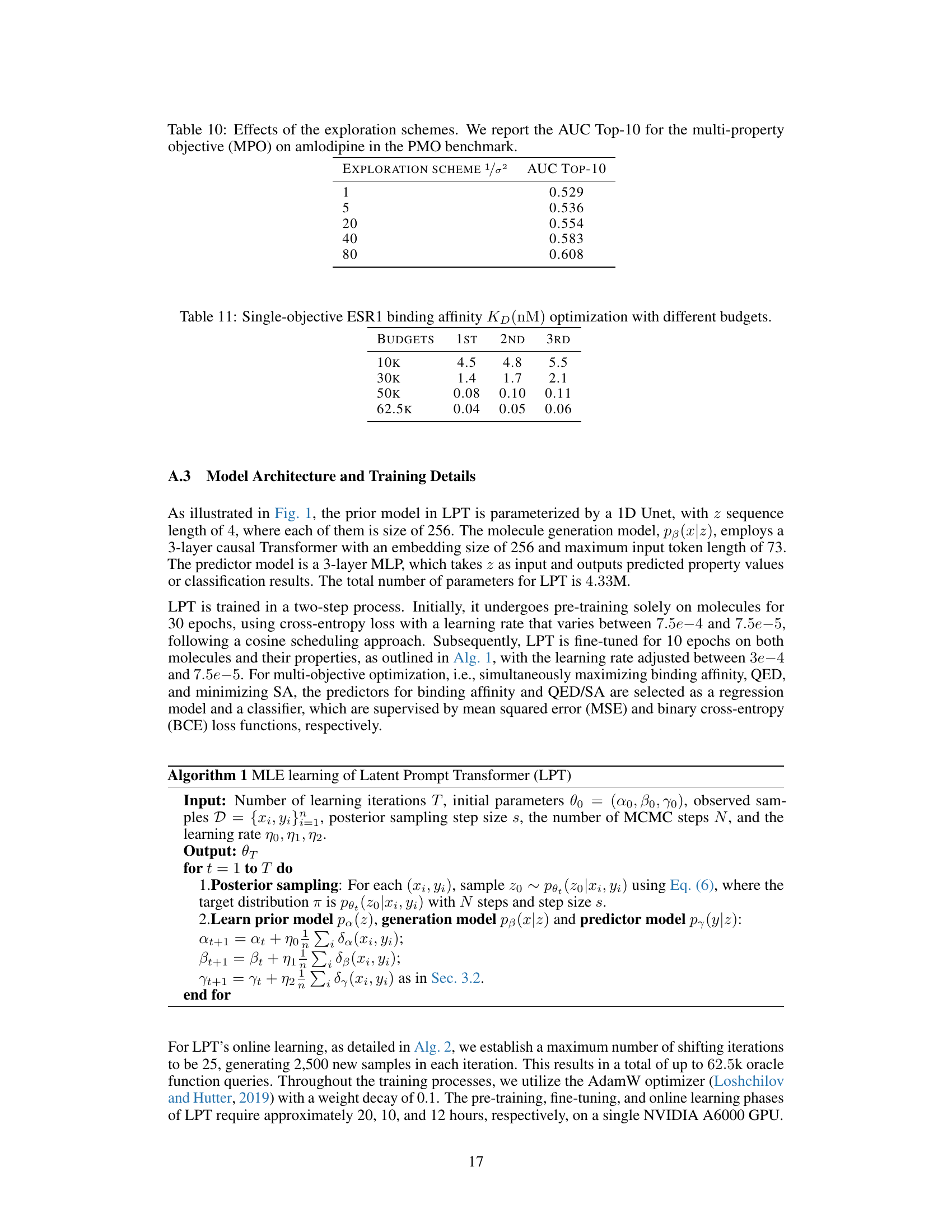

This table presents the results of an experiment that explores the effect of different exploration schemes on the performance of a multi-property objective optimization task. The exploration scheme is controlled by a hyperparameter (1/σ²) that balances exploitation and exploration during the optimization process. The results show that increasing the value of the hyperparameter leads to improved performance, as measured by the AUC Top-10 metric.

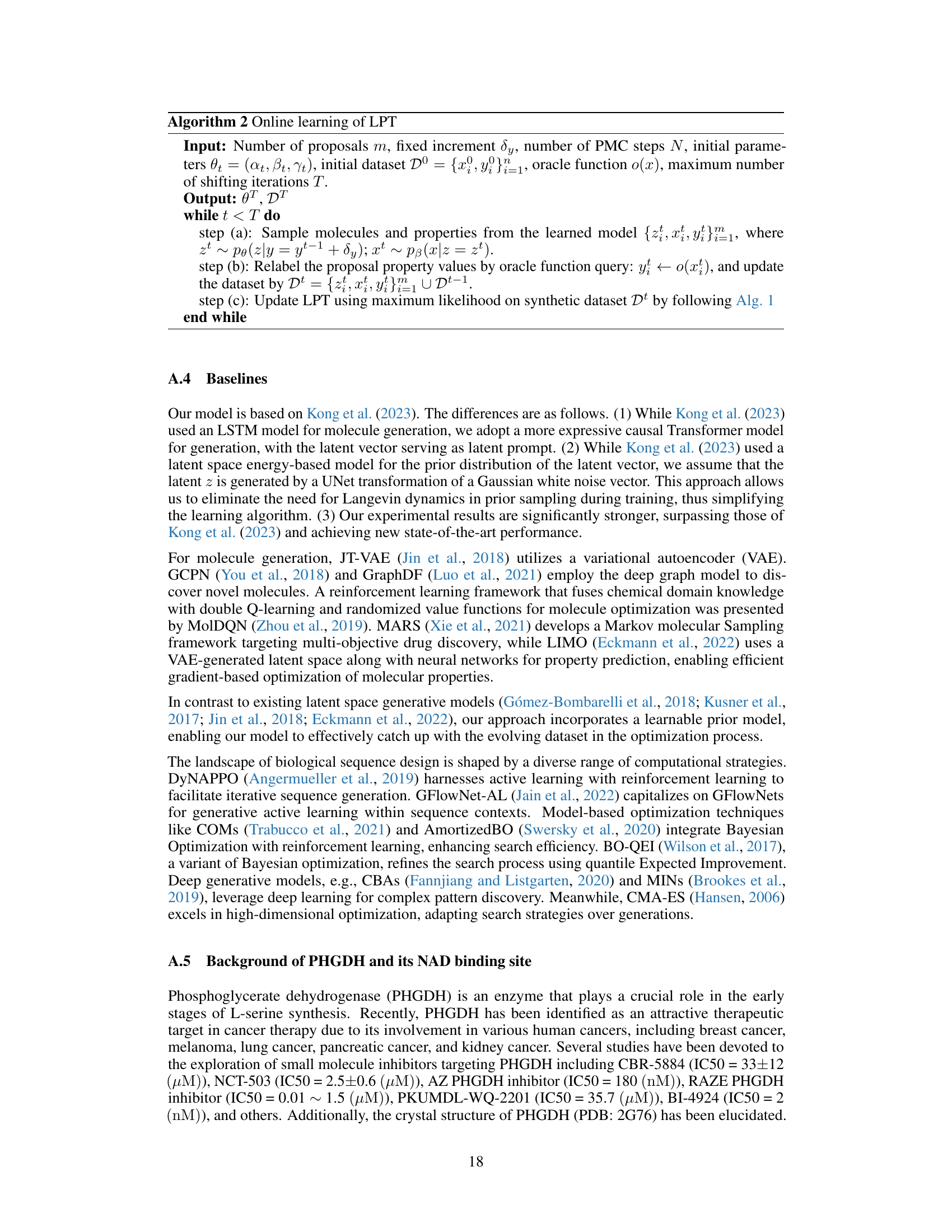

This table shows the top 3 KD (nM) values achieved for ESR1 binding affinity optimization under different oracle query budgets (10K, 30K, 50K, and 62.5K). Lower KD values indicate stronger binding affinity. The results demonstrate the improvement in binding affinity as the budget increases.

Full paper#