↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Federated learning (FL) faces challenges with non-IID data (data heterogeneity) and high communication costs. One-shot FL (OFL) aims to reduce communication by aggregating models only once, but existing OFL methods lag behind standard FL in performance. This is due to the “isolation problem,” where locally trained models fit spurious correlations instead of learning invariant features. The paper proposes a novel method to address these issues.

FuseFL tackles these issues by providing a causal perspective on the OFL problem and proposing FuseFL, a novel approach that decomposes neural networks into blocks, progressively training and fusing each block. This approach augments features and avoids the isolation problem without extra communication costs. Extensive experiments demonstrate FuseFL’s significant performance gains over existing OFL and ensemble methods, while showing scalability and low memory use, highlighting its practical value for diverse FL settings.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it tackles the performance bottleneck in one-shot federated learning (OFL), a critical area for efficient and privacy-preserving machine learning. By introducing a novel causal analysis and the FuseFL method, it offers significant improvements in accuracy while maintaining low communication and storage costs. This opens up exciting avenues for applying OFL in resource-constrained environments and paves the way for more efficient collaborative machine learning solutions. The causal perspective is also valuable beyond the specific OFL context, offering insights into addressing data heterogeneity challenges in other distributed learning scenarios.

Visual Insights#

This figure is a causal graph that illustrates the data generation process in federated learning (FL). It highlights how spurious features (Rspu) and invariant features (Rinv) contribute to the data heterogeneity across different clients. Panel (a) shows the isolated training scenario in typical ensemble FL or one-shot FL, where models are trained independently and easily fit to spurious correlations, leading to poor performance. Panel (b) shows the federated fusion approach, where augmenting intermediate features from other clients helps to mitigate the spurious correlations and improve generalization.

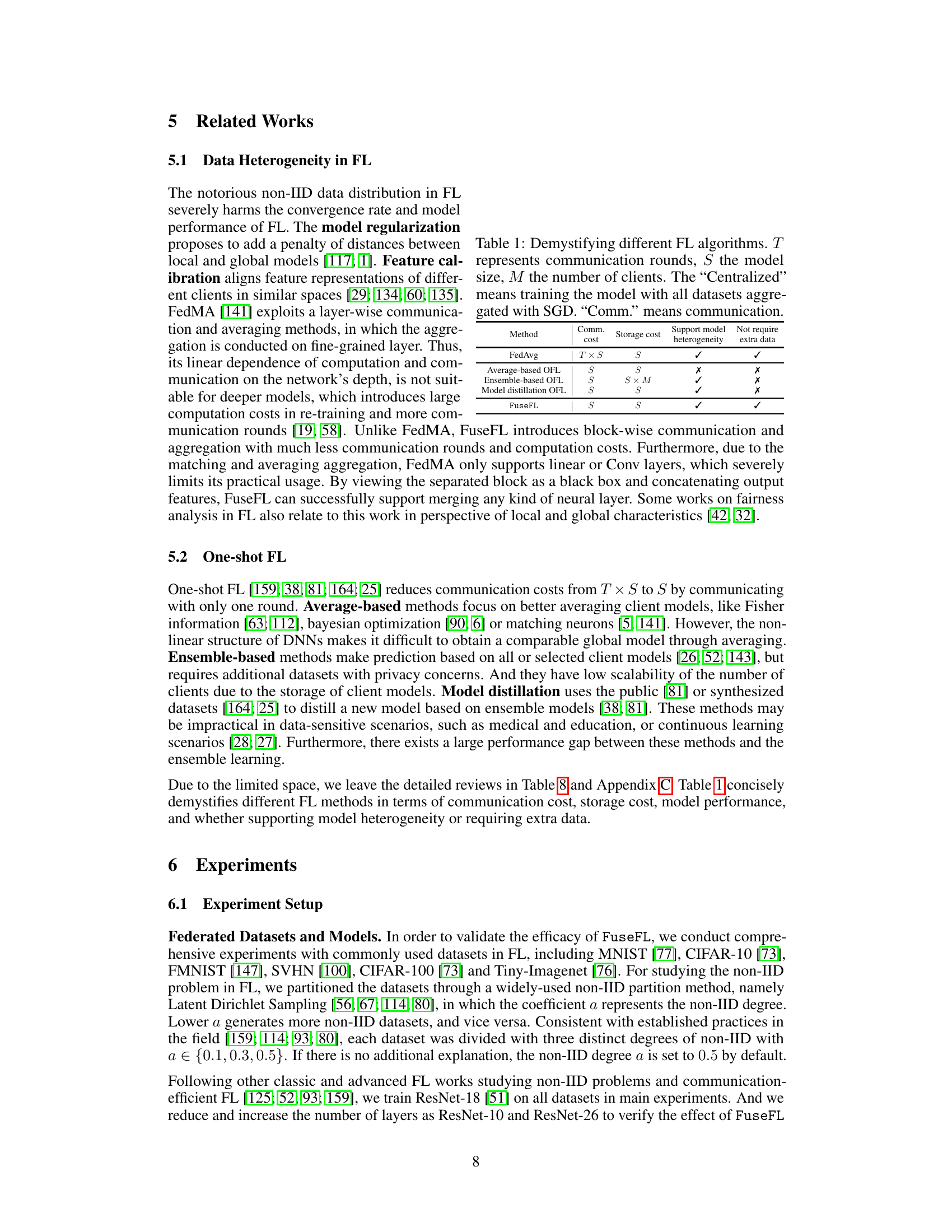

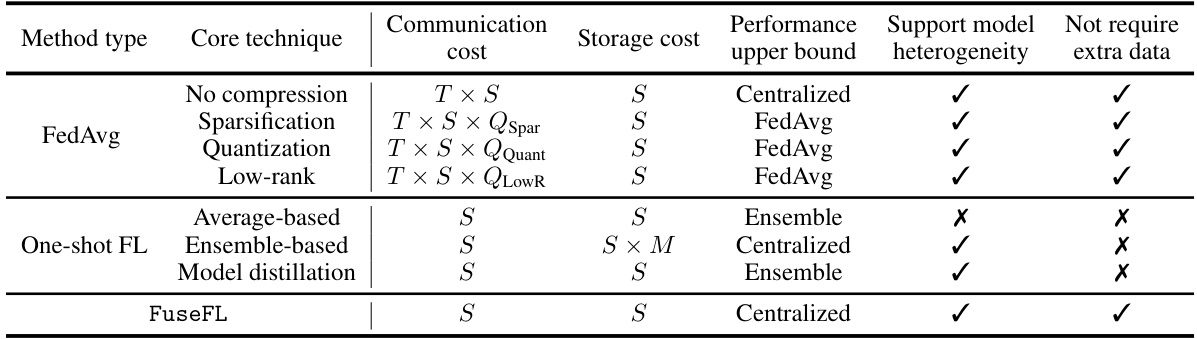

This table compares different federated learning (FL) algorithms based on their communication cost, storage cost, ability to handle model heterogeneity, and whether they require extra data. It shows that FedAvg has high communication costs, while one-shot methods like FuseFL significantly reduce this cost, but with trade-offs in terms of model heterogeneity support and extra data requirements.

In-depth insights#

Causality in OFL#

The exploration of causality within one-shot federated learning (OFL) offers a novel perspective on addressing the performance limitations of this approach. Traditional OFL methods often suffer from the isolation problem, where locally trained models are unable to generalize well to unseen data due to data heterogeneity. By adopting a causal lens, researchers can identify and mitigate these spurious correlations. The core insight is that locally trained models may easily fit to spurious correlations, leading to a poor performance on unseen data. Augmenting the training data with intermediate features from other clients serves as a crucial step to alleviate this problem. This intervention helps disentangle true causal relationships from spurious ones, resulting in models that generalize better and achieve enhanced robustness. Thus, exploring causality provides a potent framework for improving the performance and generalizability of OFL.

FuseFL Algorithm#

The FuseFL algorithm is a novel one-shot federated learning approach designed to address the limitations of existing methods. It cleverly leverages the concept of progressive model fusion, decomposing the global model into several blocks, which are then trained and fused iteratively in a bottom-up manner. This process allows local models to learn more invariant features from other clients, thus mitigating data heterogeneity and preventing overfitting to spurious correlations. The bottom-up approach enables feature augmentation without incurring additional communication costs, making FuseFL highly communication-efficient. Furthermore, the algorithm incorporates feature adaptation techniques to address the issue of mismatched feature distributions among different clients, ensuring smoother model fusion. By strategically splitting the model and managing the hidden dimensions, FuseFL achieves a significant performance improvement over existing OFL and ensemble FL methods while maintaining a low memory footprint and demonstrating excellent scalability. The use of causality analysis in understanding the underlying issues of OFL is a key strength, providing a theoretical framework for the algorithm’s design and effectiveness. FuseFL represents a significant advancement in one-shot federated learning, paving the way for more efficient and robust collaborative model training in distributed settings.

Feature Augmentation#

Feature augmentation, in the context of federated learning, addresses the critical issue of data heterogeneity. Locally trained models in isolated settings tend to overfit on spurious correlations specific to their limited datasets, leading to poor generalization. Augmenting features from other clients helps mitigate this by exposing models to broader patterns and reducing reliance on dataset-specific artifacts. This enhances the robustness of one-shot federated learning, which already faces communication cost constraints. A key idea is to leverage intermediate representations (features) from various models rather than raw data, preserving privacy. Effective augmentation strategies must also consider feature alignment and semantic consistency across clients, handling different data distributions and model architectures. The challenge lies in designing effective methods that provide a substantial performance boost without imposing additional communication or computational overheads.

Heterogeneous Models#

The concept of “Heterogeneous Models” in federated learning (FL) refers to scenarios where participating clients train diverse model architectures. This contrasts with homogeneous settings where all clients use identical models. The advantages of heterogeneous models lie in their ability to leverage the unique strengths of different architectures. For instance, some models might excel at feature extraction, while others are superior at classification. This diversity can enhance the robustness and overall performance of the federated system, leading to a potentially more accurate global model. However, the heterogeneity introduces significant challenges: the varying model complexities and output dimensions necessitate specialized aggregation methods. FuseFL, presented in the paper, elegantly addresses this by progressively fusing intermediate features, rather than directly averaging model weights. This innovative method allows it to effectively combine information from diverse architectures while maintaining efficiency. Nonetheless, exploring further methods to efficiently and effectively aggregate diverse models remains a crucial area for future research in federated learning.

Future of FuseFL#

The future of FuseFL looks promising, building upon its strengths in one-shot federated learning and causality-driven feature augmentation. Further research could explore advanced feature fusion techniques beyond simple averaging or 1x1 convolutions, potentially using more sophisticated methods to handle the heterogeneity of local feature distributions. Integrating techniques like attention mechanisms or transformer layers would be a natural extension, enabling FuseFL to process a broader spectrum of model architectures and data types more effectively. Investigating the application of FuseFL to diverse model architectures, beyond CNNs , like Transformers, would significantly broaden its reach and address the challenge of training large language models in a federated setting. Finally, incorporating robust privacy-preserving techniques is crucial to ensure widespread adoption, particularly in sensitive data domains. A deeper investigation into its robustness against various adversarial attacks would also strengthen its practical applicability and establish its reliability in real-world deployments.

More visual insights#

More on figures

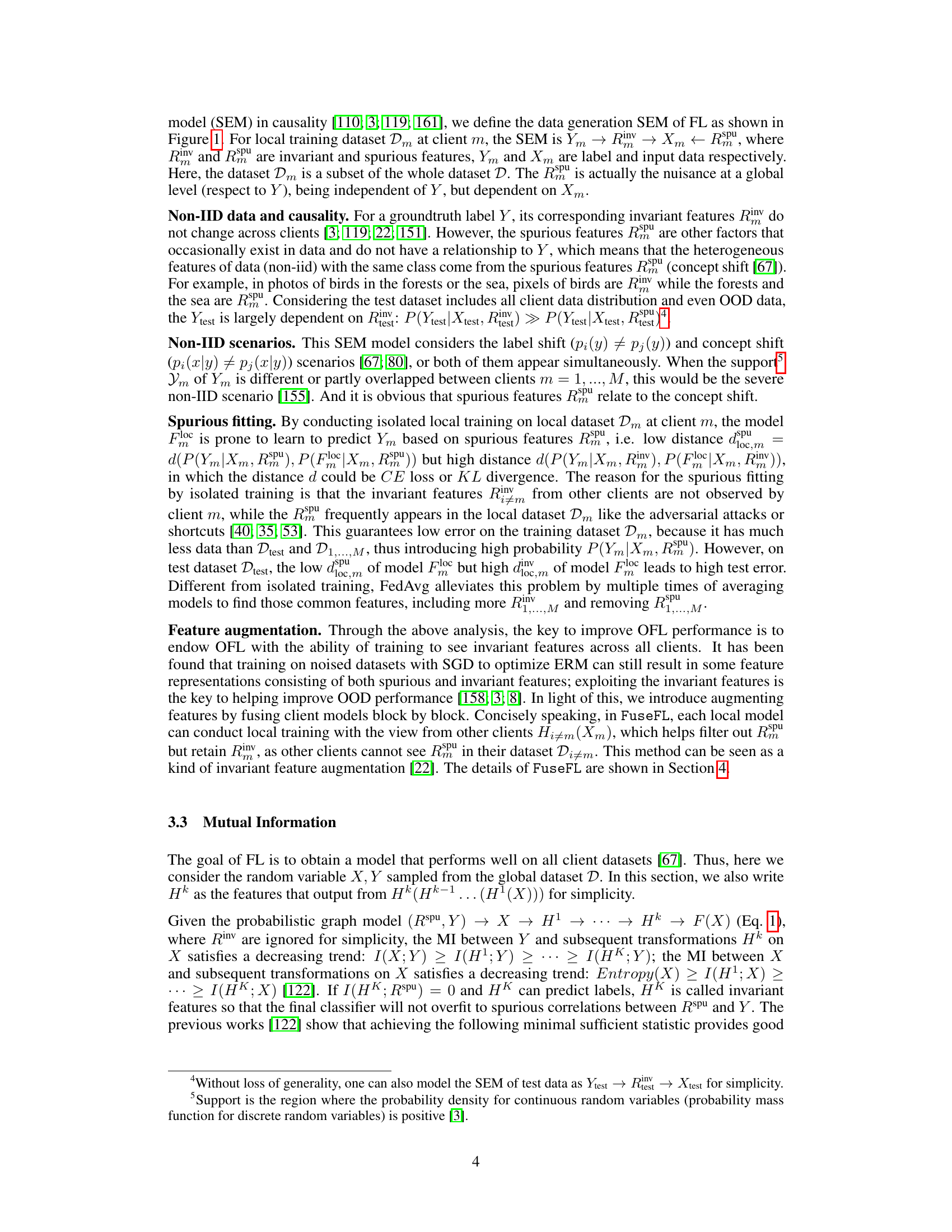

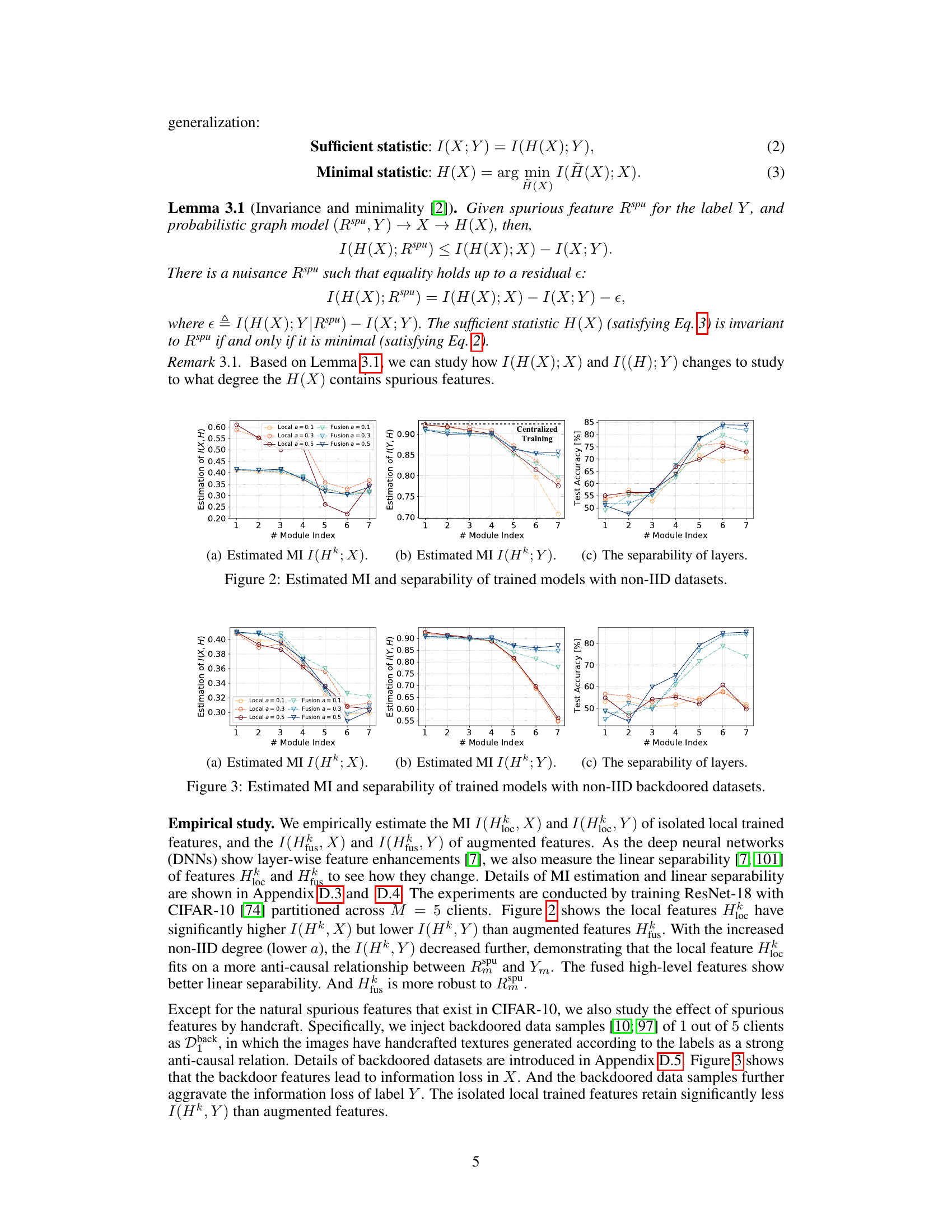

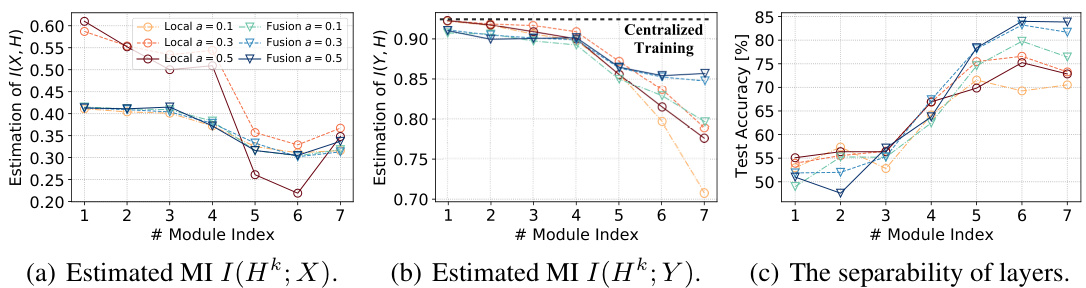

This figure presents the empirical estimation of mutual information (MI) between features and inputs (I(Hk; X)) and between features and labels (I(Hk; Y)) at different layers (modules) of a model trained on non-IID data. It shows that locally trained models tend to fit more on spurious correlations (higher I(Hk; X), lower I(Hk; Y)), while FuseFL’s progressive fusion helps to learn more invariant features (lower I(Hk; X), higher I(Hk; Y)). The separability of features at each layer is also compared, with FuseFL showing improved separability, indicating better generalization ability.

This figure shows the estimated mutual information (MI) between features and input (I(Hk; X)), features and labels (I(Hk; Y)), and the linear separability of layers in a model trained on non-IID datasets. The different lines represent different non-IID degrees (α = 0.1, 0.3, 0.5) and whether features are obtained from isolated local training or from FuseFL (feature fusion). The results indicate that FuseFL’s feature fusion method helps to improve the MI between features and labels and the separability of layers, reducing overfitting to spurious correlations.

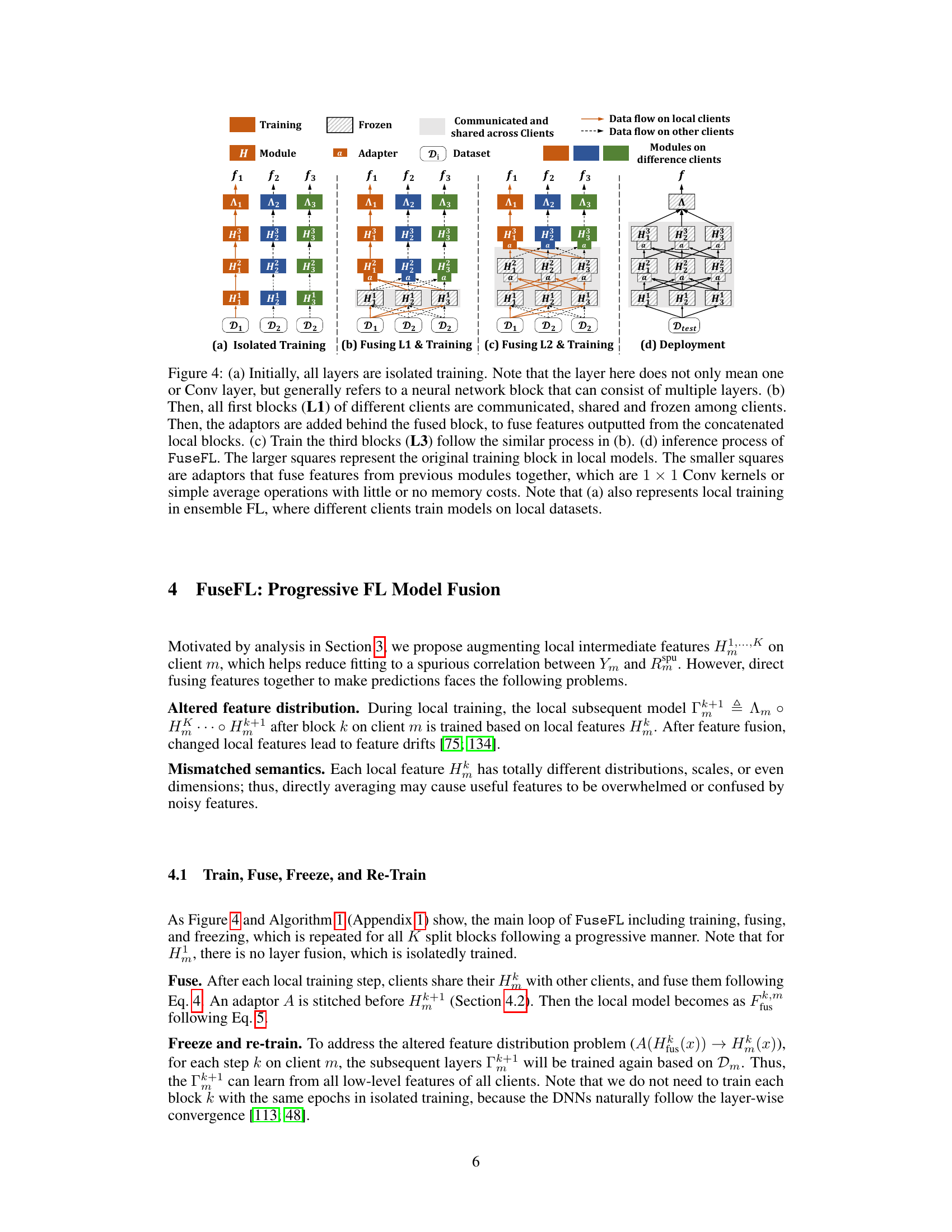

This figure illustrates the FuseFL training process. (a) shows the isolated training of each client’s model. (b), (c) show the progressive fusion of blocks from different clients, with adaptors used to integrate the fused features. (d) shows the final inference process.

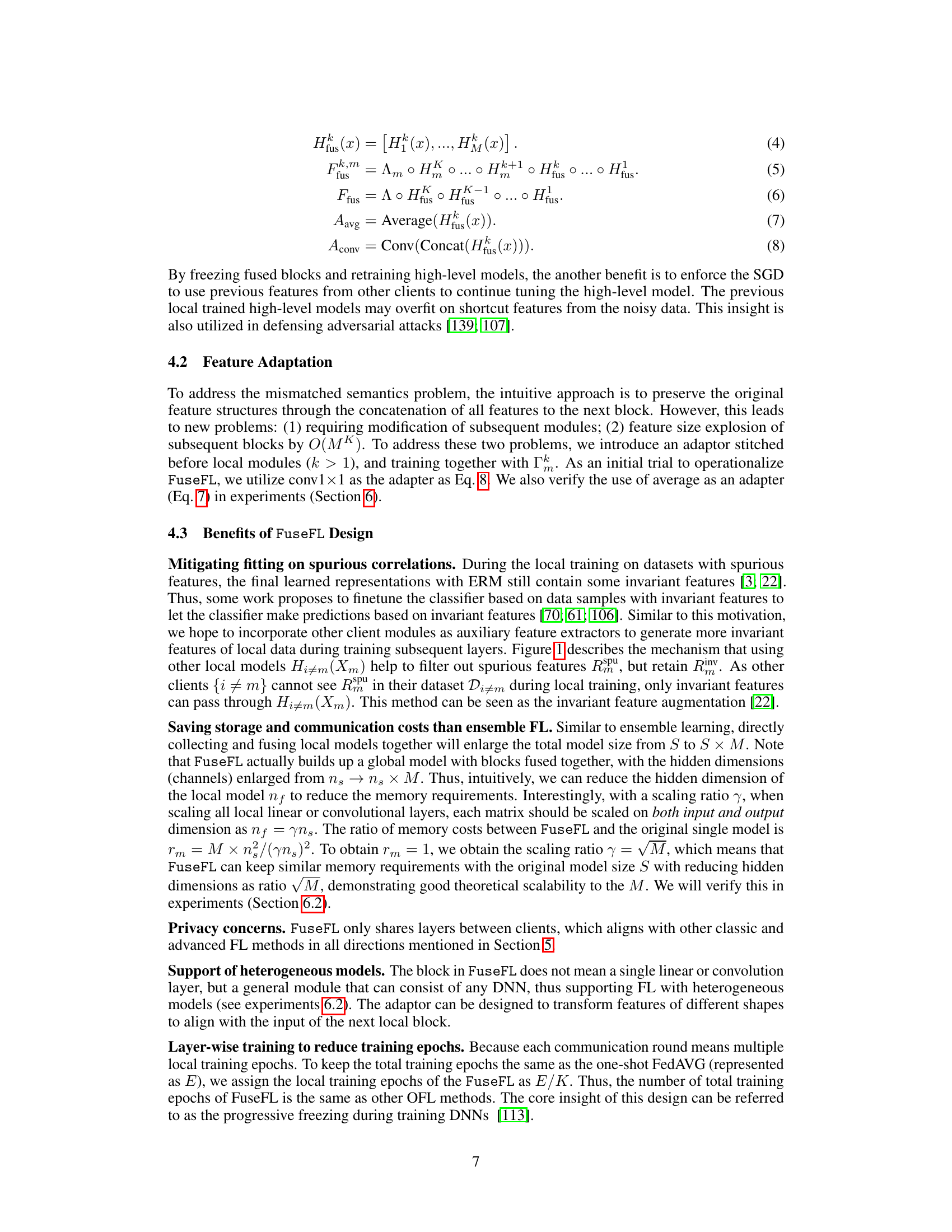

This figure shows example images from the CIFAR-10 dataset that have been modified to include backdoor triggers. The top row shows the original images, while the bottom row shows the same images with added shapes (squares, circles, triangles, etc.) overlaid on them. The shapes are color-coded according to the image’s label, creating spurious correlations that a model might learn during training if it is not robust to such adversarial examples. This is used to test the models’ resilience to backdoors in the experiments.

More on tables

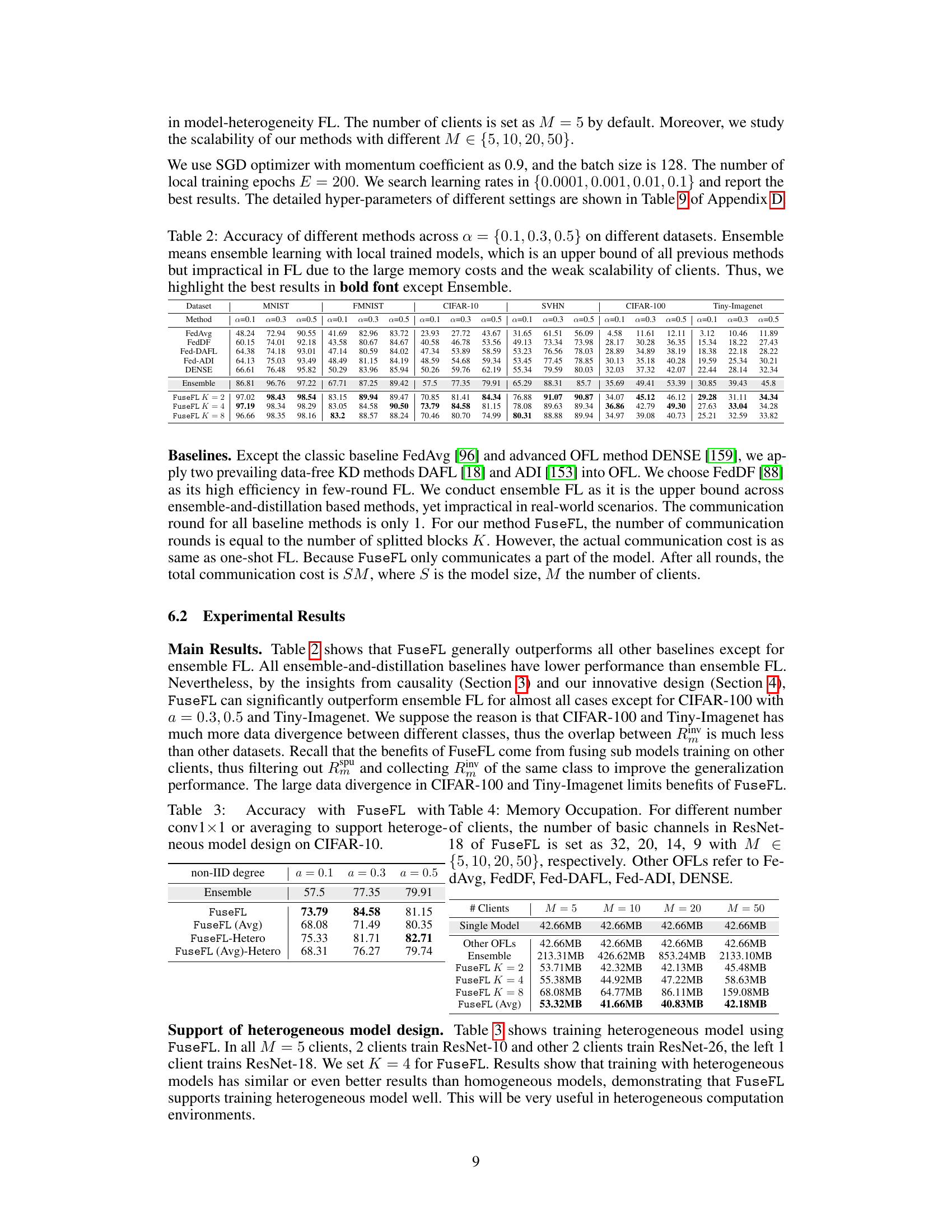

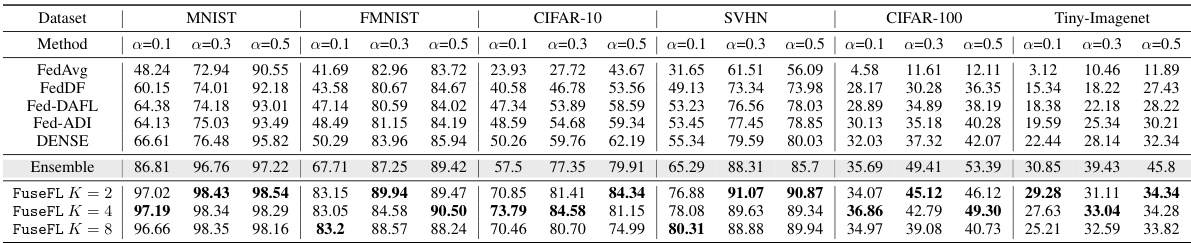

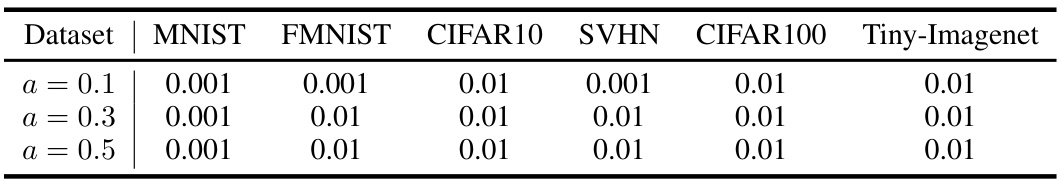

This table presents the accuracy results of various federated learning (FL) methods across three different non-IID data distributions (α = 0.1, 0.3, 0.5) and six datasets (MNIST, FMNIST, CIFAR-10, SVHN, CIFAR-100, Tiny-Imagenet). The methods compared include FedAvg, FedDF, Fed-DAFL, Fed-ADI, DENSE, and the proposed FuseFL with different numbers of modules (K). The ‘Ensemble’ row represents the upper bound achievable by combining local models, although this is impractical due to high memory and scalability issues. The table highlights the best-performing methods for each dataset and non-IID setting.

This table presents the accuracy of various federated learning (FL) methods across different datasets (MNIST, FMNIST, CIFAR-10, SVHN, CIFAR-100, Tiny-Imagenet) and non-IID data distribution levels (α = 0.1, 0.3, 0.5). The methods compared include FedAvg, FedDF, Fed-DAFL, Fed-ADI, DENSE, and FuseFL (with different numbers of modules K). Ensemble represents a baseline method that uses all local models for prediction. The table highlights the best performance achieved for each setting, excluding the ensemble method (which is impractical due to high memory and scalability issues). The results demonstrate the superior performance of FuseFL compared to other one-shot FL methods.

This table presents the accuracy results of various federated learning (FL) methods on different datasets with varying degrees of non-IID data (represented by α). The methods compared include FedAvg, FedDF, Fed-DAFL, Fed-ADI, DENSE, Ensemble, and FuseFL (with different numbers of modules, K). The Ensemble method serves as an upper bound for the other methods, but its high memory cost and scalability issues make it impractical for real-world FL scenarios. The table highlights the best-performing method for each dataset and α value, excluding the Ensemble method.

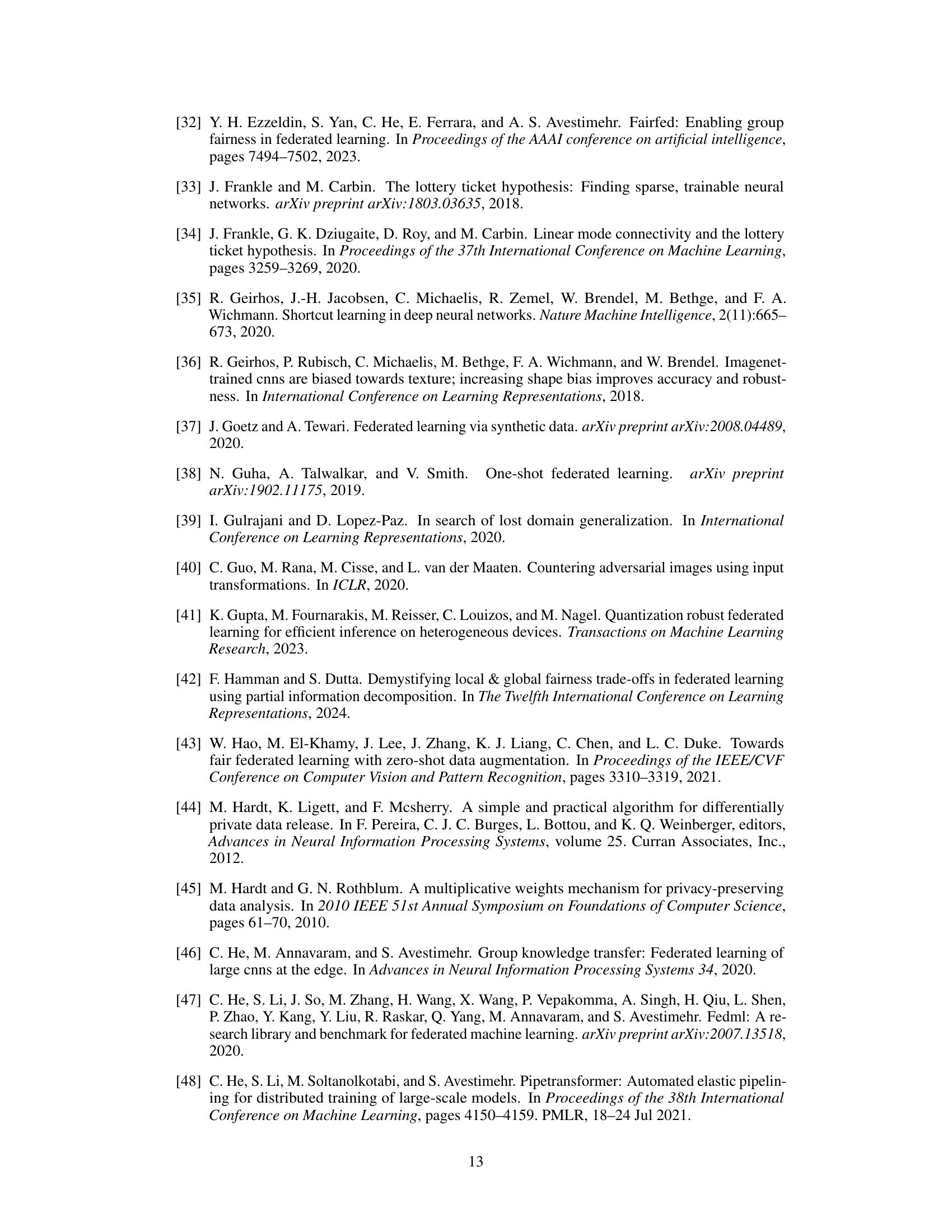

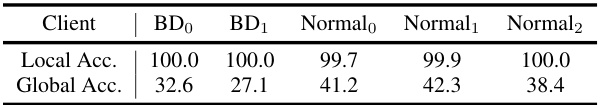

This table presents the local and global accuracy results for 5 clients in a federated learning experiment. Two clients (BD0 and BD1) were trained on datasets with backdoor attacks, whereas three clients (Normal0, Normal1, and Normal2) were trained on clean datasets. The ‘Local Acc.’ column indicates the accuracy achieved by each client on their own local dataset, demonstrating that the models trained on the backdoored datasets achieved almost perfect accuracy. However, the ‘Global Acc.’ column, which represents the accuracy obtained when all the models are aggregated on the server, shows a significant performance gap between clients trained on clean datasets and those trained on backdoored datasets. This indicates the negative impact of backdoor attacks on the overall federated learning model.

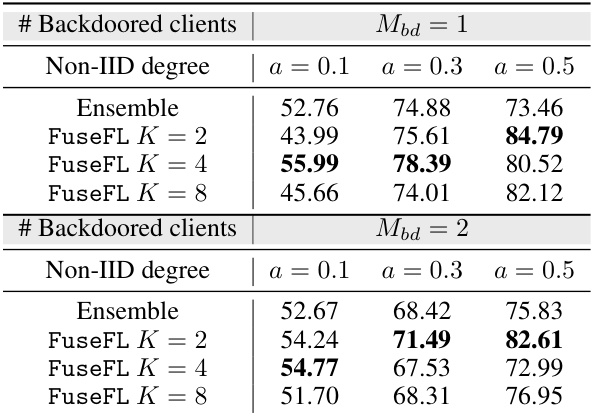

This table presents the test accuracy of different methods on backdoored CIFAR-10 datasets. The test dataset is clean, and the number of backdoored clients (Mbd) varies between 1 and 2. The results show how the backdoored data influences the performance of different methods under varying non-IID degrees (α).

This table compares different federated learning (FL) algorithms across several key characteristics: communication cost, storage cost, performance upper bound, support for model heterogeneity, and requirement for external data. It highlights the trade-offs between communication efficiency, model performance, and data requirements of various FL approaches.

This table shows the accuracy of various federated learning methods across three different levels of data heterogeneity (α = 0.1, 0.3, 0.5) and six different datasets (MNIST, FMNIST, CIFAR-10, SVHN, CIFAR-100, Tiny-Imagenet). The methods compared include FedAvg, FedDF, Fed-DAFL, Fed-ADI, DENSE, and the proposed FuseFL with different numbers of modules (K=2, 4, 8). Ensemble learning is also included as an upper bound, although it’s impractical for real-world federated learning due to its high memory cost and scalability issues. The best results for each setting are highlighted in bold, excluding the Ensemble results.

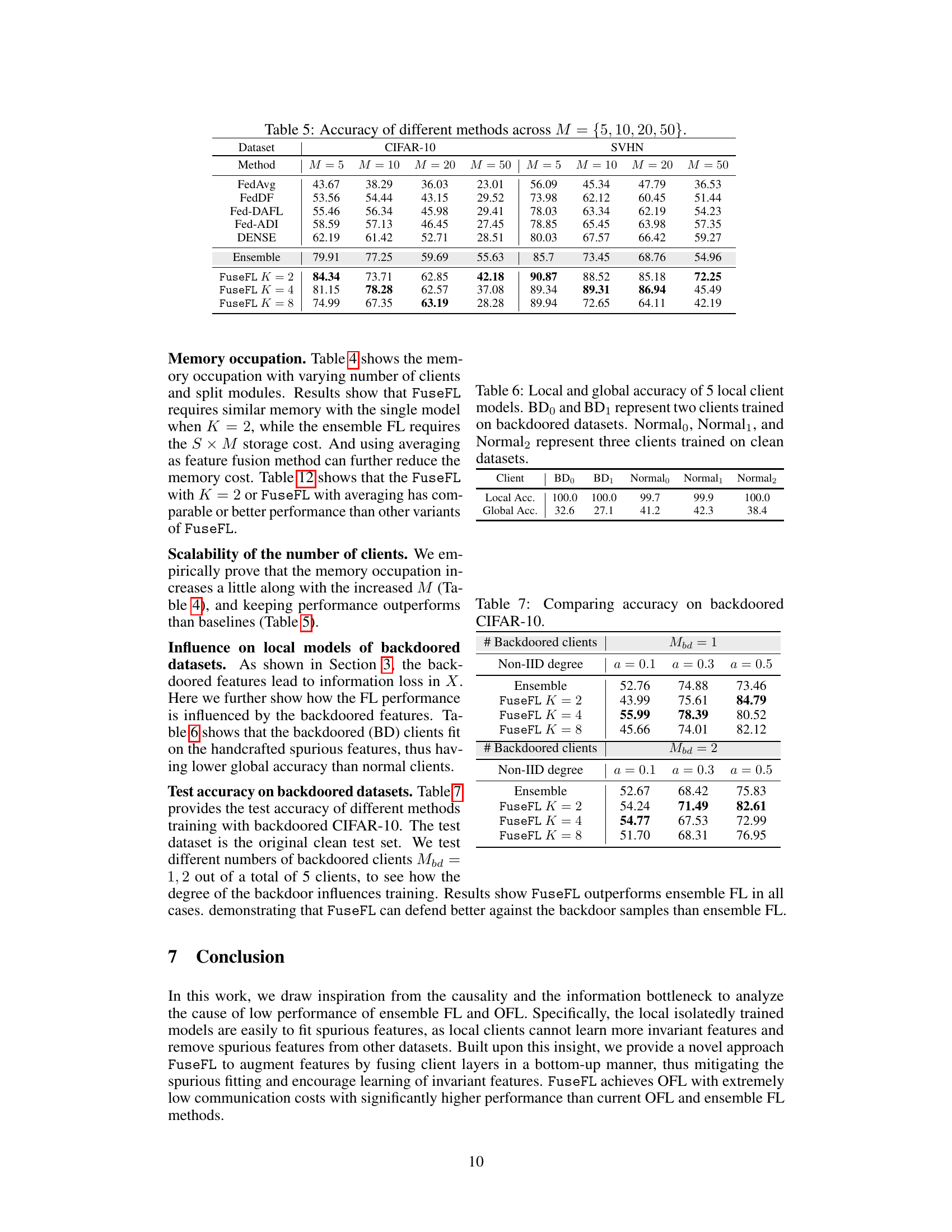

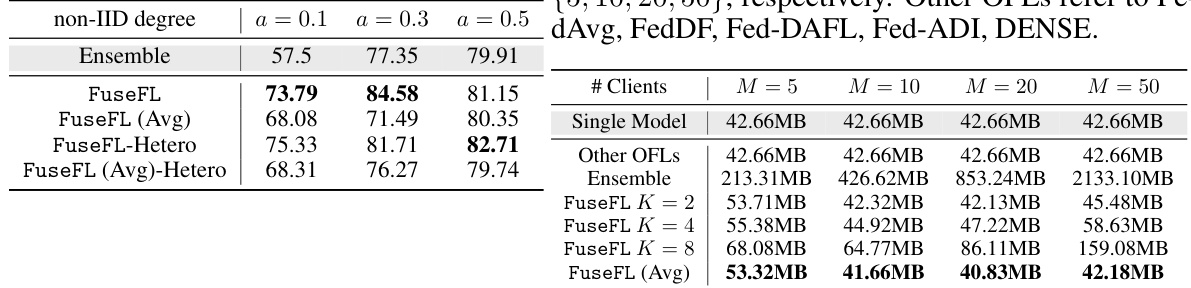

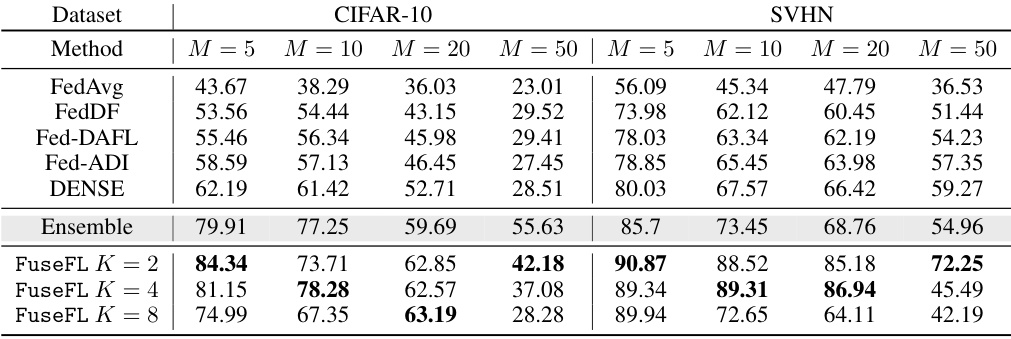

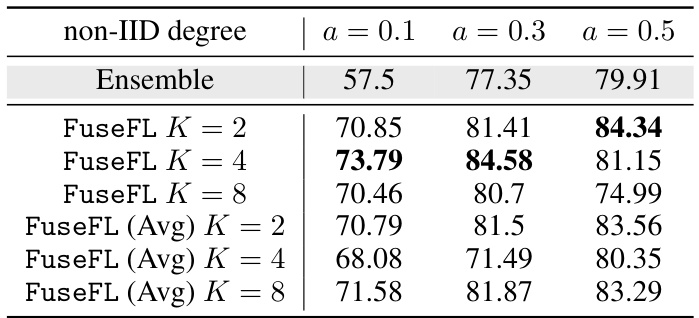

This table compares the performance of different model fusion methods (FuseFL with conv1x1, FuseFL with averaging, FuseFL with conv1x1 and heterogeneous models, FuseFL with averaging and heterogeneous models) on CIFAR-10 dataset with varying number of clients (M=5, M=10). The ‘Ensemble’ row provides a benchmark representing the upper bound performance achievable through ensembling local models.

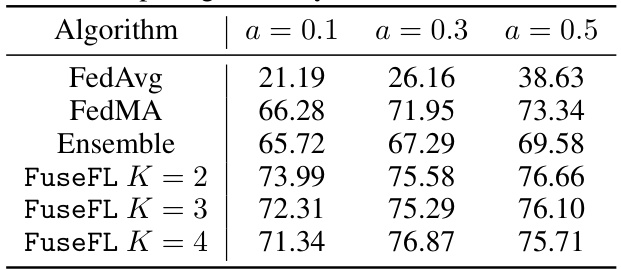

This table compares the accuracy of various federated learning algorithms, including FedAvg, FedMA, Ensemble, and FuseFL with different numbers of blocks (K), on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The comparison is made for three different levels of non-IID data distribution (α = 0.1, 0.3, 0.5). The table highlights the performance of FuseFL in achieving comparable or better accuracy than other methods, especially when considering the constraint of only one communication round. It shows that FuseFL generally outperforms the other methods under one-shot communication constraints.

This table presents the accuracy results of different federated learning methods (FedAvg, FedDF, Fed-DAFL, Fed-ADI, DENSE, Ensemble, and FuseFL) on various datasets (MNIST, FMNIST, CIFAR-10, SVHN, CIFAR-100, Tiny-Imagenet) under different non-IID data distribution levels (α = 0.1, 0.3, 0.5). The Ensemble method serves as an upper bound, highlighting the performance limitations of other one-shot federated learning methods. FuseFL’s best results are bolded, demonstrating its superior performance compared to other methods except the computationally expensive Ensemble method.

This table compares several federated learning (FL) algorithms based on their communication costs, storage costs, and support for model heterogeneity. It highlights the communication and storage cost savings of one-shot FL and the proposed FuseFL method while showing their performance in comparison with multi-round FL methods and ensemble methods. The table also notes whether the methods require additional data for training.

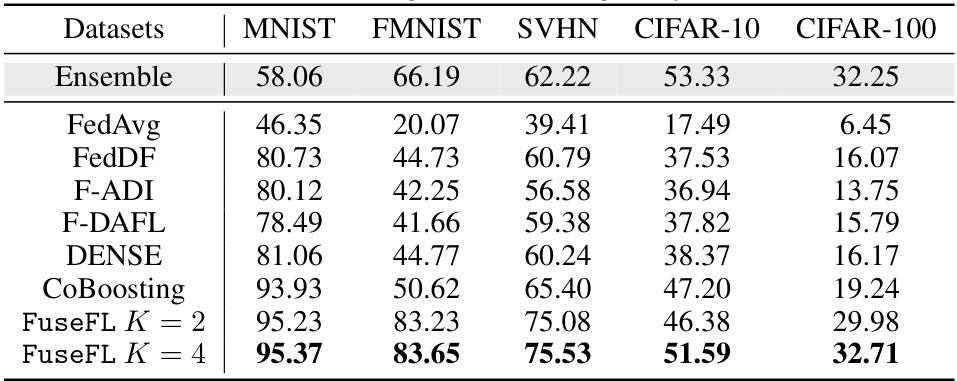

This table presents the accuracy results of different federated learning methods on various datasets (MNIST, FMNIST, SVHN, CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100) under a higher degree of data heterogeneity (α = 0.05). It compares the performance of FuseFL with several baseline methods including FedAvg, FedDF, Fed-ADI, Fed-DAFL, DENSE, and CoBoosting. The results demonstrate the accuracy of each method across these datasets. The purpose is to show that FuseFL performs well even under significant data heterogeneity.

Full paper#