↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Accurately tracking points in videos is crucial for many computer vision tasks. However, existing methods often suffer from high computational costs due to exhaustive search methods. To reduce computational burden, they usually downsample the video frames at the cost of precision, thus causing tracking failures. This problem is particularly challenging when the objects in the video are dynamic.

TrackIME tackles this issue with a new method that focuses on instance-level motion estimation to prune the irrelevant parts of video frames and therefore reduce the search space without downsampling. It introduces a unified framework that jointly performs point tracking and segmentation, resulting in improved accuracy and robustness to occlusions. Experimental results on standard benchmarks demonstrate TrackIME’s efficacy and superiority over existing methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel approach to video point tracking that significantly improves accuracy and efficiency. Current methods struggle with computational demands, often resorting to downsampling, which loses crucial details. TrackIME offers a solution by intelligently pruning the search space, focusing on relevant regions. This advancement is valuable across various computer vision tasks and paves the way for more sophisticated applications dealing with complex dynamic video scenes. Its strong empirical results on benchmark datasets are further evidence of its significance and impact.

Visual Insights#

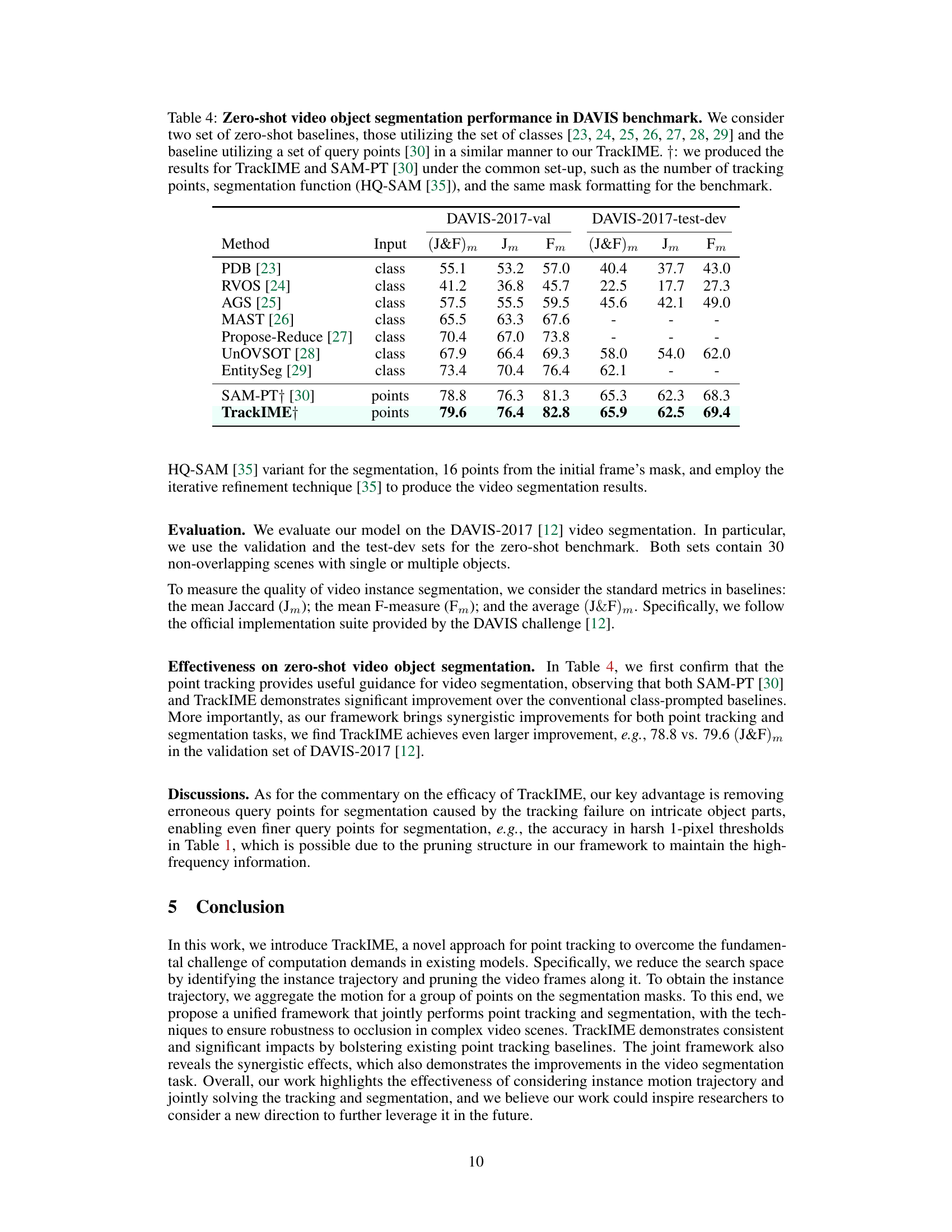

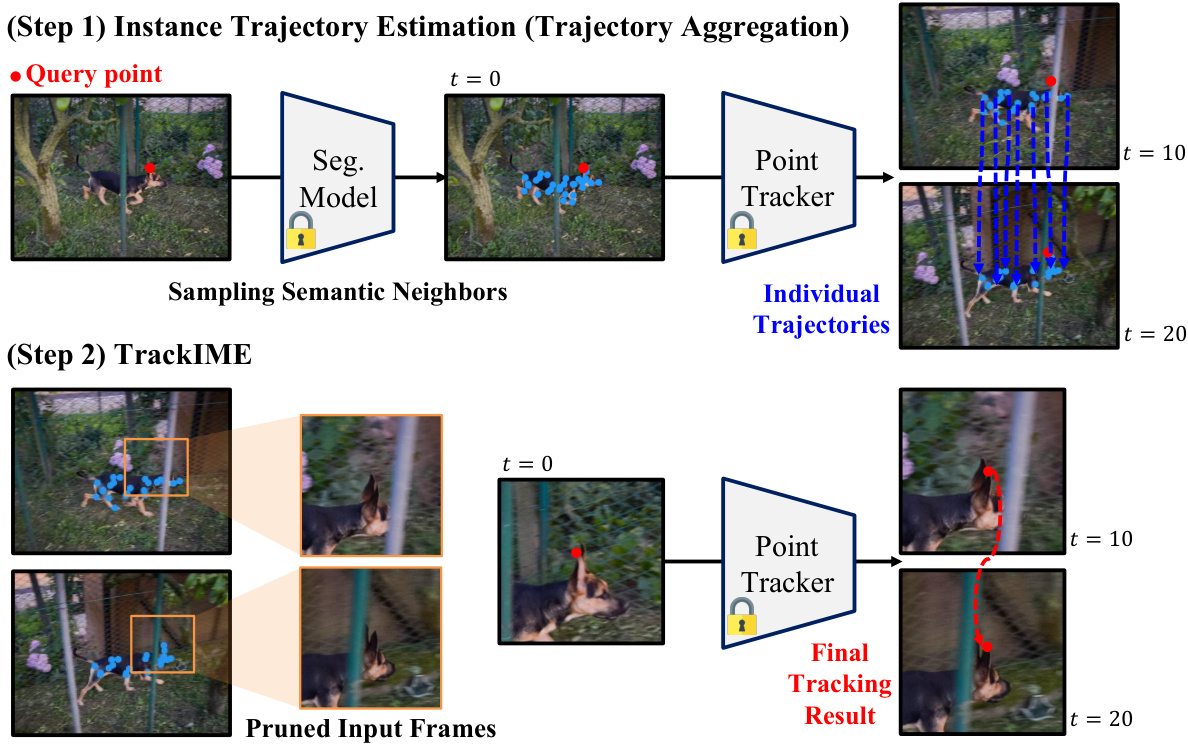

The figure illustrates the two-step process of TrackIME. Step 1 shows instance trajectory estimation through trajectory aggregation. A query point is identified, a segmentation model determines semantic neighbors, and an individual point tracker follows the trajectories of these neighbors. Step 2 shows TrackIME itself, where the pruned input frames (along the instance trajectory) are used in point tracking to generate the final tracking result. This method enhances point tracking by focusing only on relevant regions.

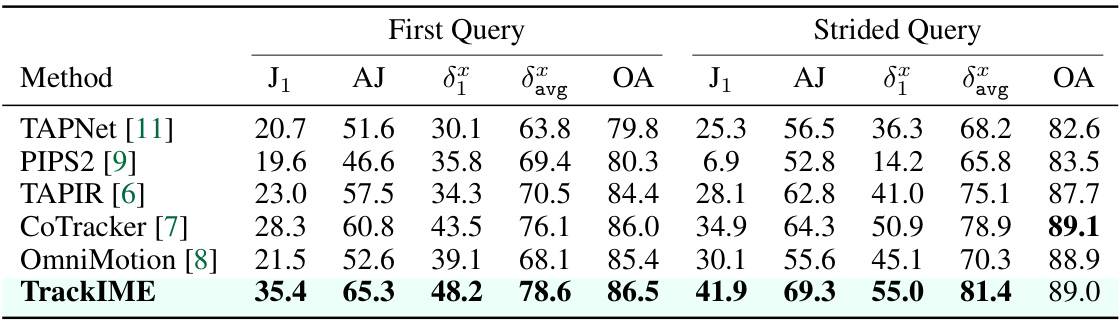

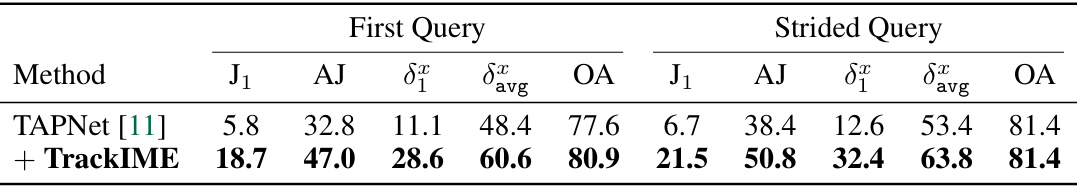

This table presents a comparison of point tracking performance on the DAVIS dataset for dynamic objects. Several state-of-the-art methods are evaluated using two different query scenarios: ‘First Query’ (single query at the start) and ‘Strided Query’ (queries at intervals). The metrics used to evaluate performance are Jaccard Index (J1 and AJ), average displacement error (δε and δavg), and occlusion accuracy (OA). TrackIME, the proposed method, is compared against other methods (TAPNet, PIPS2, TAPIR, CoTracker, OmniMotion) to show its performance gains.

In-depth insights#

Instance Motion#

The concept of ‘Instance Motion’ in video analysis focuses on tracking the movement of individual objects (instances) within a scene. This is crucial because, unlike optical flow which deals with dense motion fields, instance motion specifically isolates object trajectories, enabling a more robust understanding of complex scenes with occlusions or multiple moving objects. Effective instance motion estimation requires accurate object segmentation, enabling the system to precisely define the boundaries of each instance. Once segmented, tracking algorithms can focus on the relevant regions of each frame, reducing computational cost and improving accuracy. This involves aggregating the motion of multiple points within the instance to estimate a cohesive trajectory, handling occlusion and noise in the process. This approach enhances point tracking significantly, as it avoids the computationally expensive search across the entire image. It also allows for better handling of occlusions since only the relevant parts of the image are analyzed, improving the robustness of the tracking over time.

Search Space Pruning#

The heading ‘Search Space Pruning’ suggests a method to optimize video point tracking by reducing the computational burden. The core idea is to intelligently restrict the area of each frame where the tracking algorithm needs to search for points, thus improving efficiency. This is crucial in video processing because exhaustive searches across the entire frame for every point in every frame are computationally expensive. The method likely uses instance segmentation or another object detection technique to identify the relevant regions in the image. By focusing the search within the boundaries of detected objects, it avoids unnecessary calculations in empty space, significantly reducing processing time and improving speed. Effective pruning depends critically on accurate instance segmentation. If the segmentation mask is inaccurate and misses parts of the object, the point tracker might fail to find all its instances, thus reducing the accuracy. A well-designed pruning method would likely incorporate mechanisms for handling occlusions and variations in object appearance throughout the video sequence. Furthermore, a balance needs to be struck: aggressive pruning can increase speed but may reduce accuracy if important features are discarded. Therefore, the algorithm should carefully define the pruning criteria to optimally trade-off speed and accuracy. A key aspect of the success of this approach hinges on its ability to dynamically adapt to the movement of objects across frames, ensuring the tracking focus stays centered around moving instances.

Unified Framework#

A unified framework in a research paper typically integrates multiple, previously disparate components into a single, cohesive system. This approach offers several key advantages. First, it promotes synergy, where the combined effect of the integrated components is greater than the sum of their individual parts. Second, a unified framework simplifies the overall system, making it easier to understand, implement, and maintain. Reduced complexity leads to improved efficiency and potentially better performance. Third, it facilitates easier adaptation and scalability, as changes or extensions to one component can be made without significant impact on the others. Finally, this approach often produces a more elegant and robust solution, offering superior performance and resilience compared to using independent modules. However, designing a truly unified framework requires careful consideration of the relationships between components and necessitates thoughtful integration. A poorly designed unified framework may introduce unexpected complexities or diminish the benefits of integration.

Progressive Inference#

Progressive inference, as described in the context, seems to be a method to enhance the accuracy of video point tracking by using a series of models with increasing fidelity. It leverages the results of a less computationally expensive model to inform a more accurate model. This hierarchical approach likely reduces the overall computational cost compared to using only a high-fidelity model. The key benefit is a synergistic improvement, where each model refines the trajectory estimation, culminating in a more precise final tracking result. By using a progressive strategy, the approach likely minimizes information loss that may occur when directly using downsampled frames, allowing for more precise tracking. The progressive inference method enhances the overall robustness of the video point tracking system by mitigating the risks associated with occlusion or errors in earlier stages. This is a smart strategy to leverage the advantages of multiple models without significant computational burden.

Future Directions#

Future research directions stemming from this work could involve developing more robust instance motion estimation techniques that are less reliant on pre-trained models and can handle more complex scenarios, such as significant occlusions or rapid motion. Exploring alternative pruning strategies that are more adaptive and less dependent on the accuracy of instance segmentation is also key. A deeper investigation into the synergistic interplay between point tracking and segmentation could potentially lead to improved performance in both tasks. Further investigation might focus on developing methods that are more computationally efficient, particularly for processing high-resolution video data. Finally, extending the approach to 3D point tracking would significantly broaden its applicability and impact.

More visual insights#

More on figures

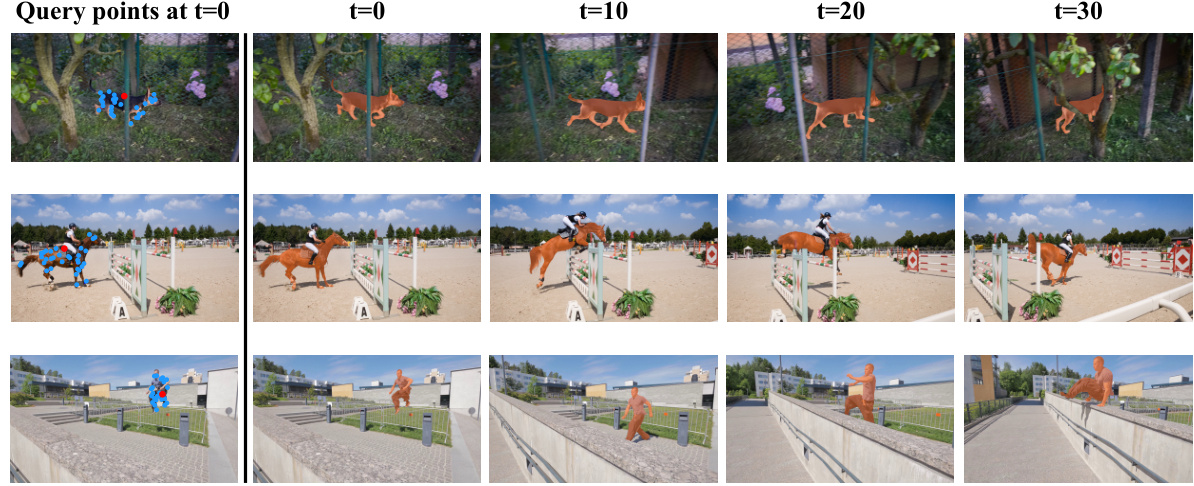

This figure demonstrates the video instance segmentation results produced by TrackIME. It shows how the framework generates high-quality segmentation masks by aggregating masks associated with individual query points, using their visibility values as weights. The example shows three different video sequences with their masks generated at different time frames(t=0, t=10, t=20, t=30).

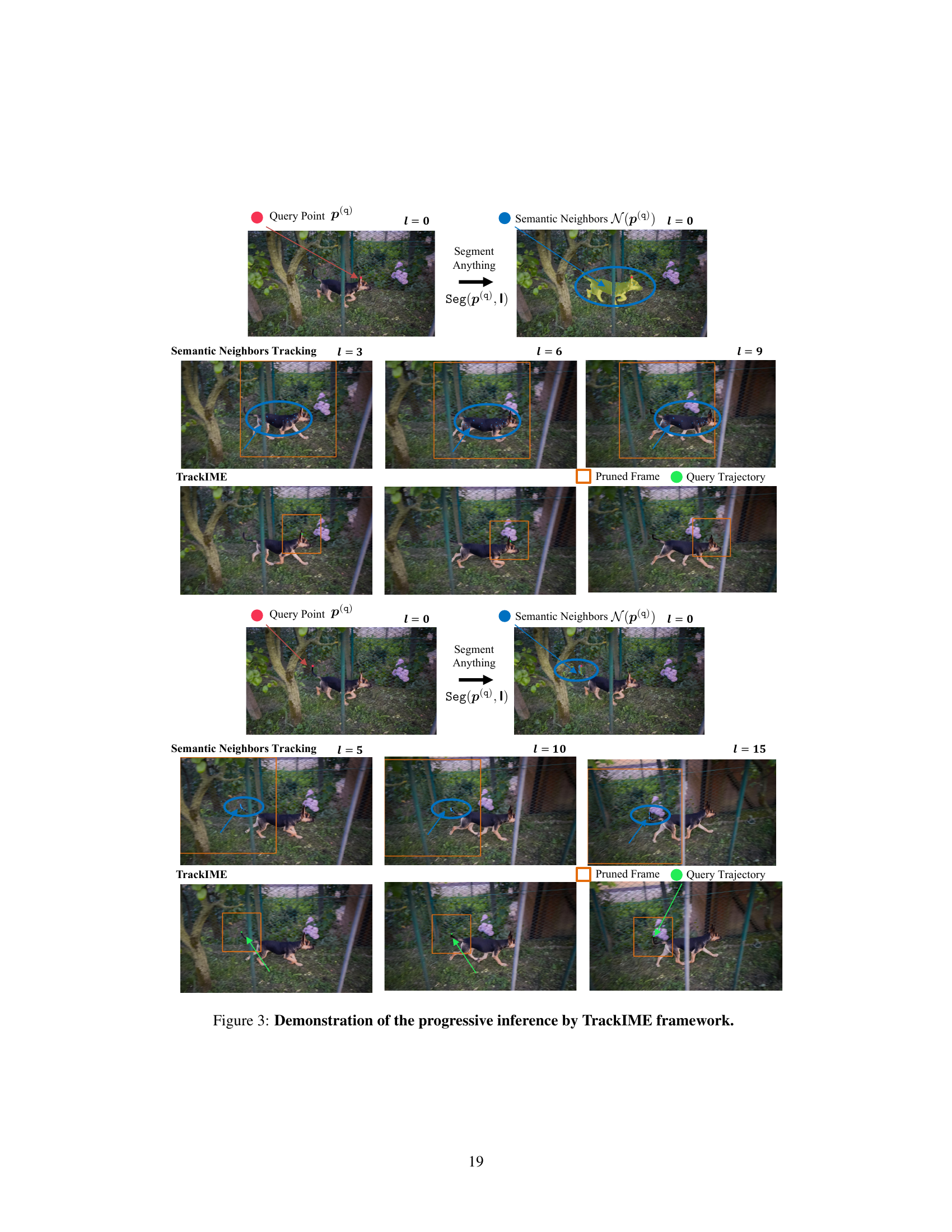

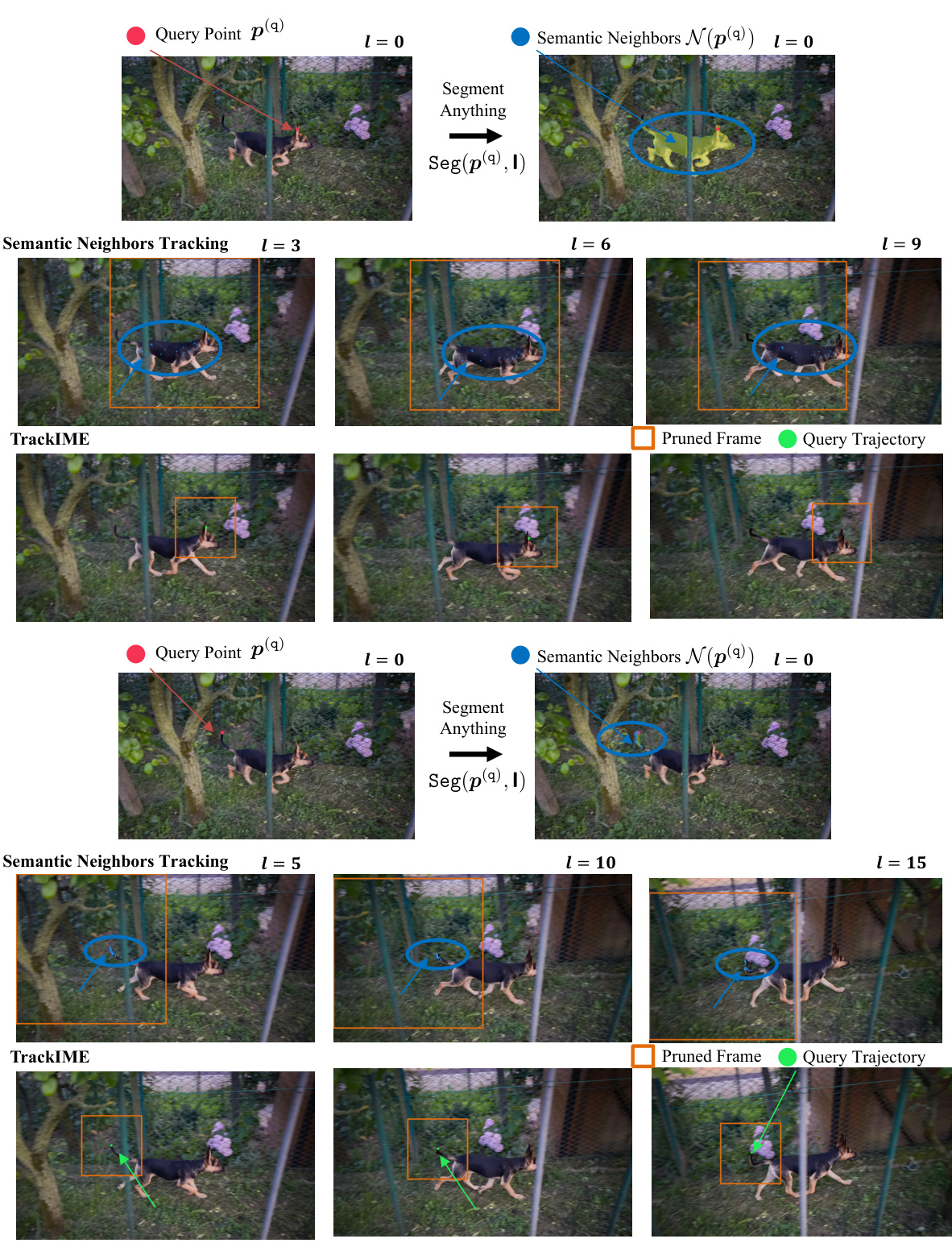

This figure demonstrates the progressive inference process in the TrackIME framework. It shows how the search space for point tracking is progressively pruned using instance motion estimation and segmentation. The top row illustrates the process for one query point, with the sampling of semantic neighbors and their tracking results. The bottom row shows a second example of progressive inference. In both examples, TrackIME starts with a broad search area centered around the query point (red circle), and gradually narrows this area over subsequent frames (orange boxes) by utilizing improved trajectory estimation from the instance mask. The final frame displays a significantly reduced search region.

More on tables

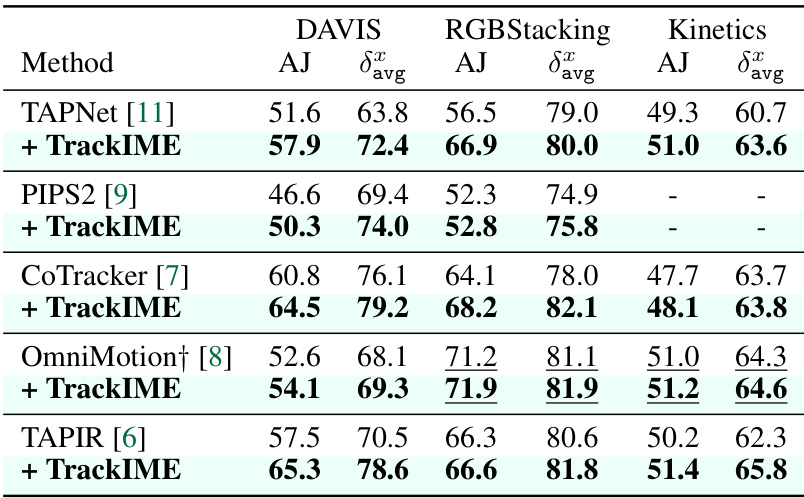

This table demonstrates the universality of TrackIME by incorporating it with five different point tracking models (TAPNet, PIPS2, CoTracker, OmniMotion, TAPIR) and evaluating their performance on three benchmark datasets (DAVIS, RGBStacking, Kinetics). It shows consistent performance improvements across all baselines and datasets when TrackIME is incorporated. Note that some results for OmniMotion are obtained using subsets of RGBStacking and Kinetics datasets because of high computational costs.

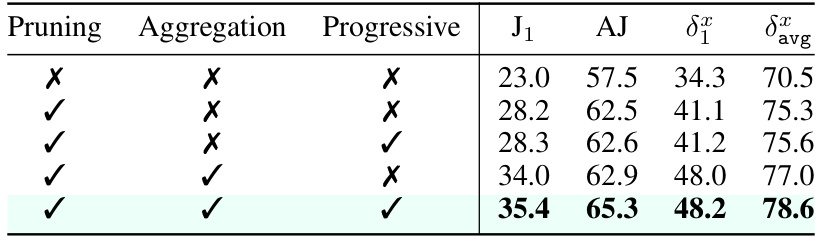

This table presents an ablation study evaluating the individual and combined effects of three key components of the TrackIME model on point tracking performance. The components are search space pruning, trajectory aggregation, and progressive inference. The performance is measured using the Jaccard index (J1), average Jaccard index (AJ), and average displacement error (δx) at 1-pixel and average pixel thresholds. The evaluation was conducted on the DAVIS benchmark dataset, which is widely used for dynamic object tracking.

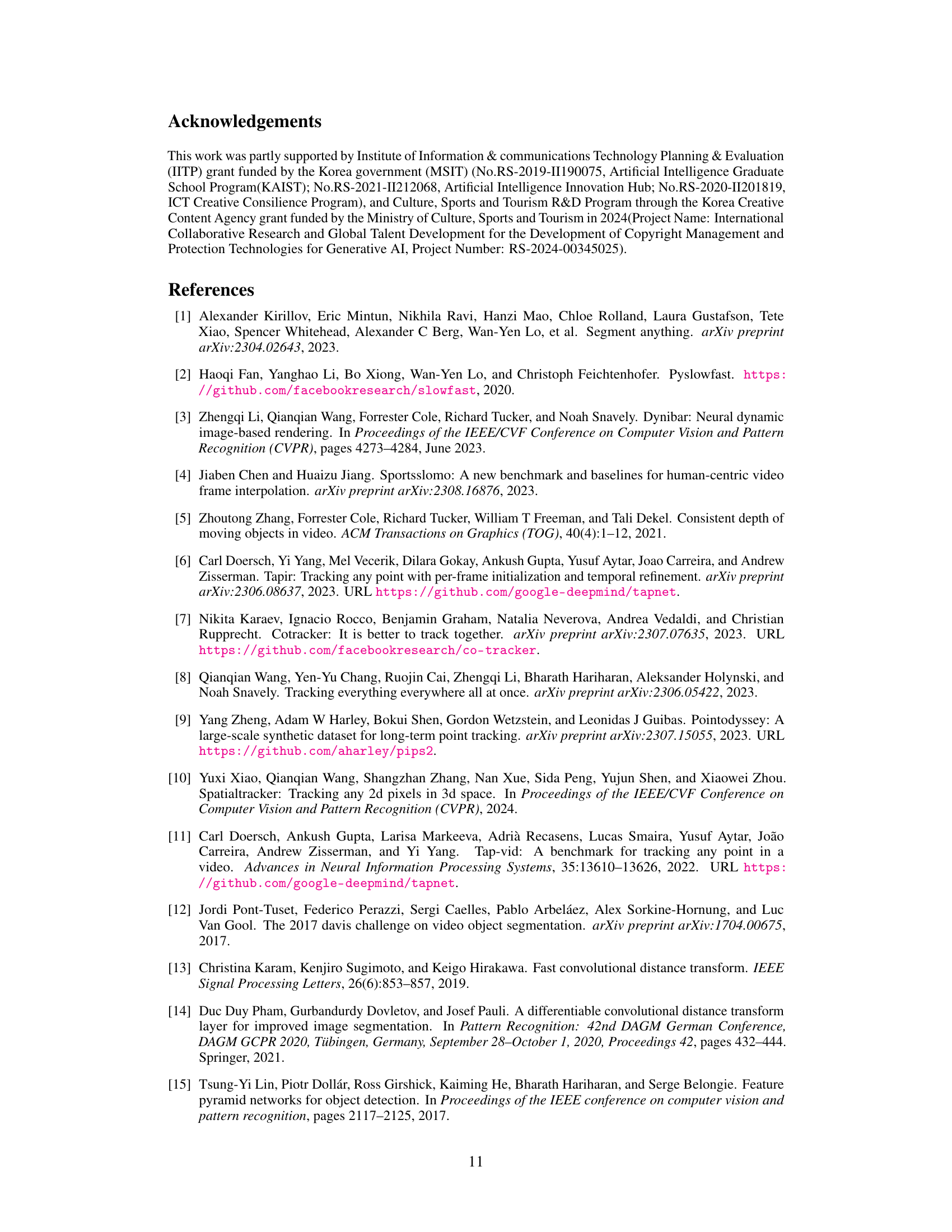

This table presents the performance comparison of different zero-shot video object segmentation methods on the DAVIS benchmark. It contrasts methods using class labels as input with those using point trajectories (like TrackIME). The results are given in terms of mean Jaccard (Jm), mean F-measure (Fm), and their average (J&F)m for both the validation and test-dev sets.

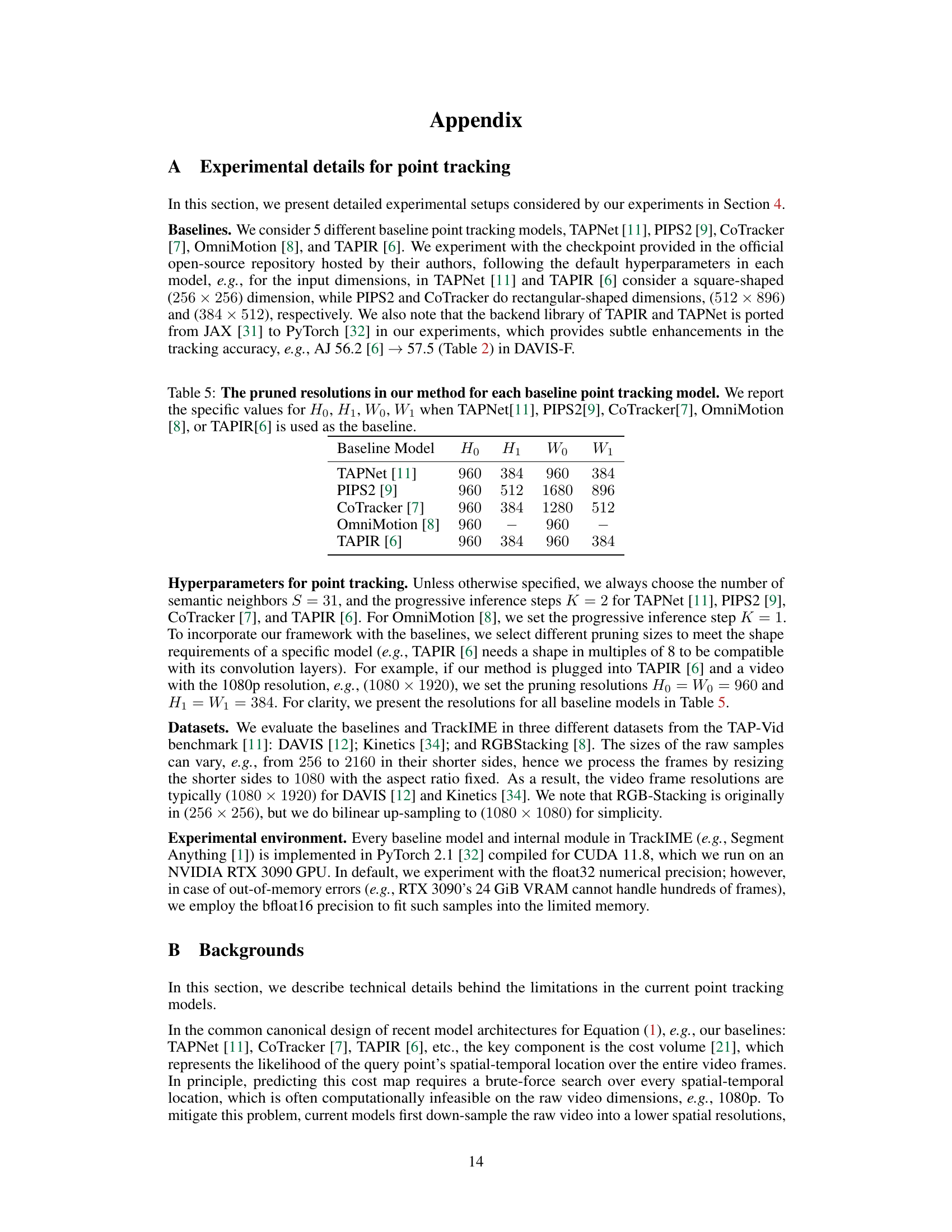

This table shows the input size used for each baseline model in the TrackIME framework. The baseline models are TAPNet, PIPS2, CoTracker, OmniMotion, and TAPIR. The table lists the height and width of the input frames (𝐻₀ and 𝑊₀) and the height and width of the pruned input frames (𝐻₁ and 𝑊₁). The pruned input frames are used to reduce computation time. This table is helpful to understand how the input sizes are adapted for different models within the TrackIME framework.

This table presents a comparison of different point tracking methods on the DAVIS dataset, focusing on dynamic objects. The metrics used to evaluate performance include Jaccard Index (J1 and AJ), average delta errors (δε and δανg), and occlusion accuracy (OA). The results show that TrackIME, when combined with the TAPIR tracker, consistently outperforms other state-of-the-art methods in various metrics.

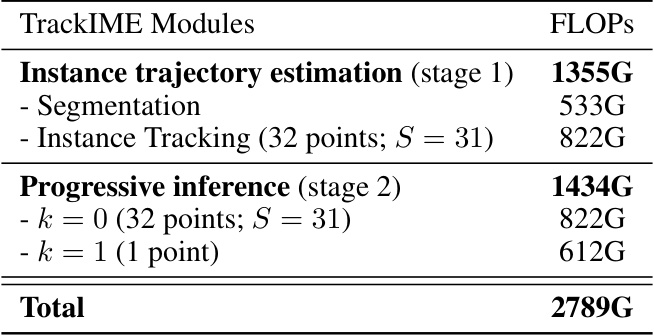

This table compares the computational cost (measured in FLOPs) and performance of different versions of the TAPIR model and the TrackIME model. It shows how FLOPs increase with higher input resolution for TAPIR, and also shows the performance of TrackIME, which uses a smaller input size while outperforming the other higher resolution TAPIR models.

This table demonstrates the universality of TrackIME by incorporating it with different state-of-the-art point tracking models (TAPNet, PIPS2, CoTracker, OmniMotion, TAPIR). It shows the average Jaccard index (AJ) and average accuracy (δαavg) for each model, both with and without TrackIME, across three benchmark datasets (DAVIS, RGBStacking, Kinetics). The results highlight consistent improvements achieved by TrackIME across various models and datasets.

This table shows the ablation study of different pruning sizes used in the TrackIME framework. It compares the performance using various pruning sizes (1080, 960, 768, 512, 384 pixels) with a single progressive step (K=1), and a configuration with two progressive steps (K=2) using sizes 960 and 384. The results are evaluated using various metrics, including pixel-scale metrics (J1, δ1, J2, δ2) and average-scale metrics (AJ, δavg). This analysis demonstrates how different pruning strategies impact performance in terms of accuracy and efficiency.

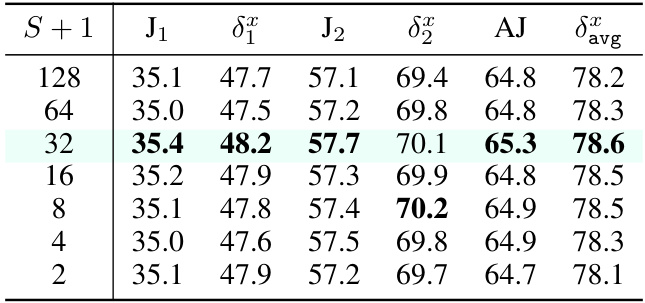

This table presents an ablation study on the effect of varying the number of semantic neighbors (S+1) used in the TrackIME framework. The study evaluates the impact on the performance of the point tracking task, measured by both pixel-level (J1, J2) and average-scale (AJ, δavg) metrics. The results are obtained using the DAVIS-F dataset.

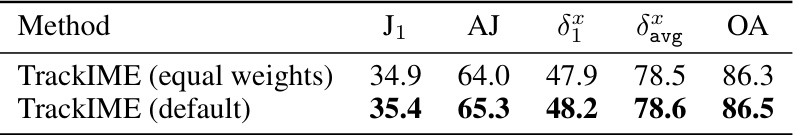

This table presents an ablation study on the impact of using equal weights versus default weights in the aggregation process within the TrackIME framework. The evaluation metrics used are J1 (Jaccard-1), AJ (Average Jaccard), δα1 (d-average accuracy at 1-pixel threshold), δαavg (average d-average accuracy), and OA (Occlusion Accuracy). The results show that using the default weights yields slightly better performance than using equal weights for all metrics. This highlights the importance of the weighted aggregation strategy employed in TrackIME for improved accuracy.

This table presents a comparison of point tracking performance on dynamic objects using the DAVIS dataset. It compares several methods, including TAPNet, PIPS2, TAPIR, and CoTracker, and shows how TrackIME improves upon the baseline performance of TAPIR. The metrics used for evaluation include Jaccard Index (J1, AJ), average displacement error (δε), and occlusion accuracy (OA). Two query scenarios are considered: First Query (single query at the start of the video) and Strided Query (queries at every 5 frames).

Full paper#