↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current video causal reasoning research primarily focuses on short videos with single events and simple causal relationships, neglecting the complexity of real-world scenarios involving multiple events across long videos. This limitation hinders the development of AI systems capable of comprehensive video understanding from a causal perspective. The lack of a suitable task and benchmark further exacerbates this issue, making it difficult to evaluate and compare the performance of different causal reasoning models.

This paper introduces a new task and dataset called Multi-Event Causal Discovery (MECD) to address this issue. MECD aims to uncover causal relationships between multiple events distributed chronologically across long videos. To accomplish this, the paper proposes a novel framework inspired by the Granger Causality method, employing an efficient mask-based event prediction model and integrating advanced causal inference techniques such as front-door adjustment and counterfactual inference to handle confounding and illusory causality. Experiments demonstrate that the proposed framework significantly outperforms existing methods, achieving improved accuracy in identifying causal associations within multi-event videos. The introduction of MECD and the proposed framework will significantly advance the state-of-the-art in video causal reasoning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it introduces a novel task and benchmark (MECD) for multi-event causal reasoning in videos, a significantly under-explored area. It also presents a novel framework that surpasses existing methods, opening avenues for improved video understanding and causal analysis research. The benchmark will facilitate future research, driving progress in AI’s ability to understand complex temporal relationships.

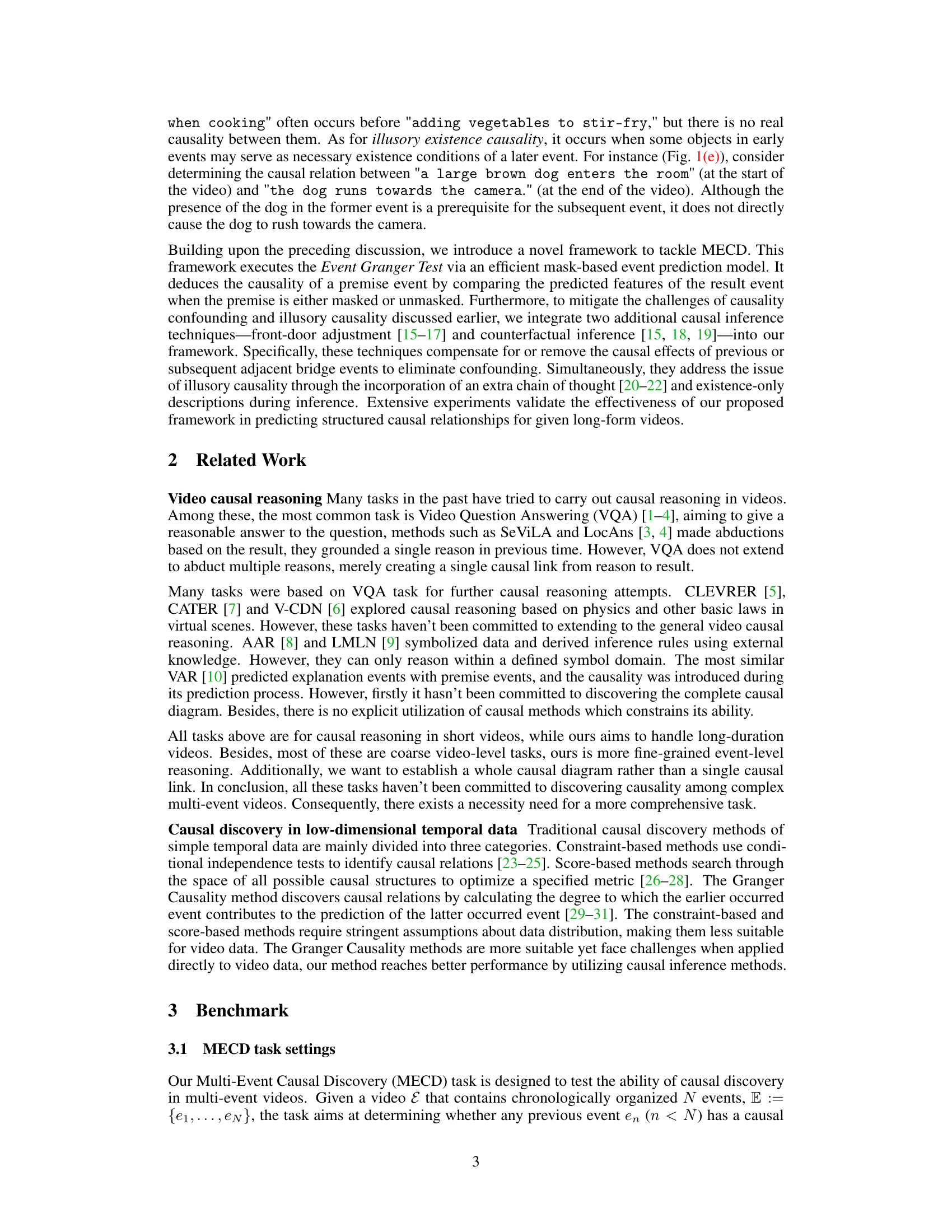

Visual Insights#

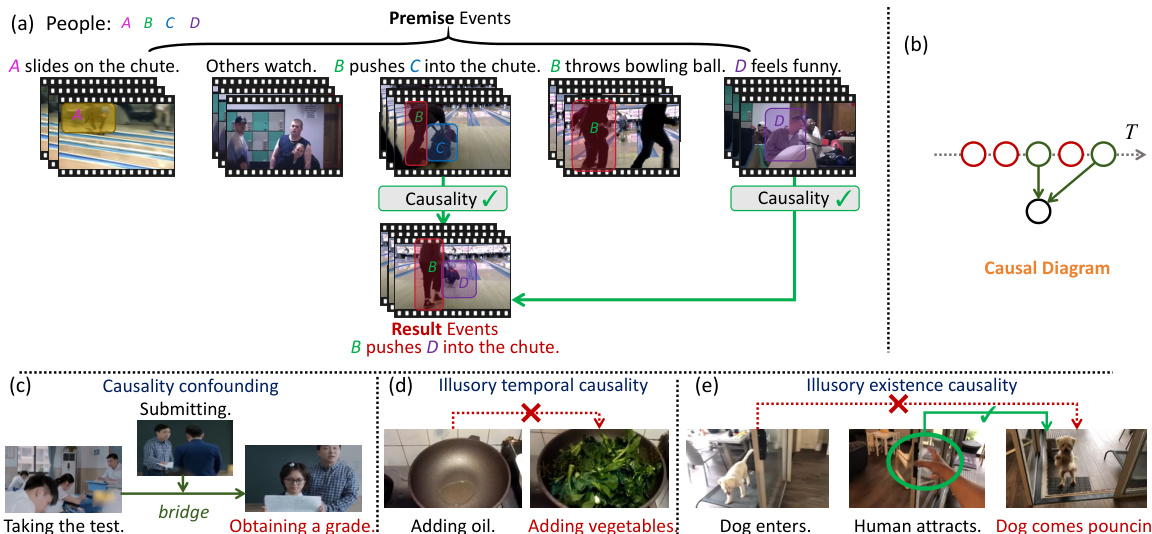

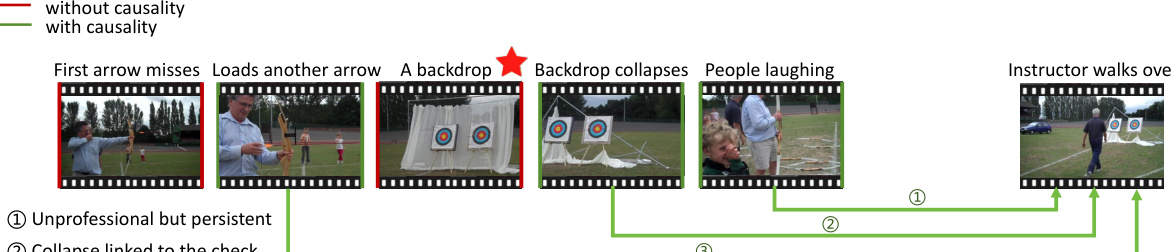

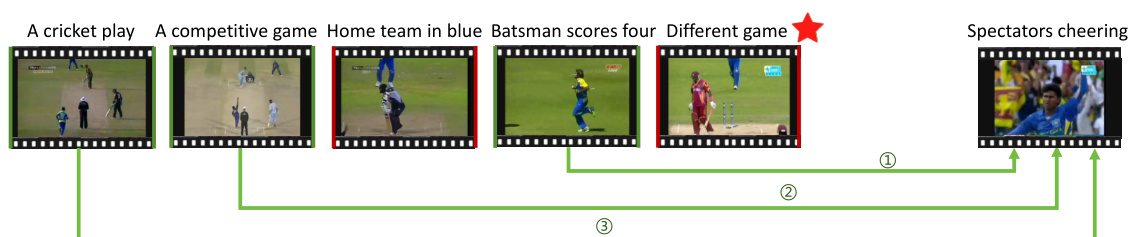

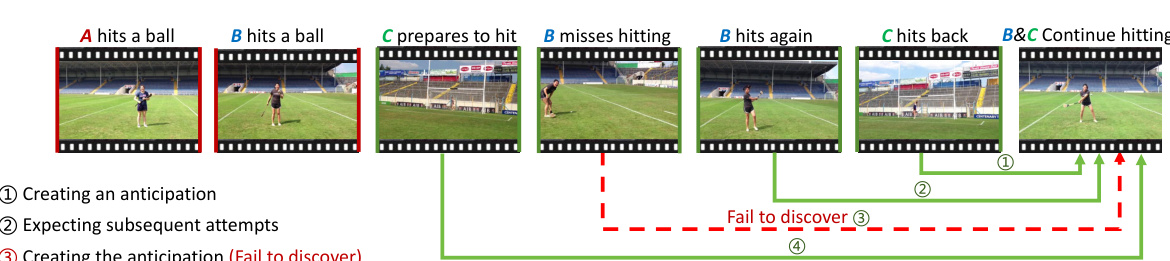

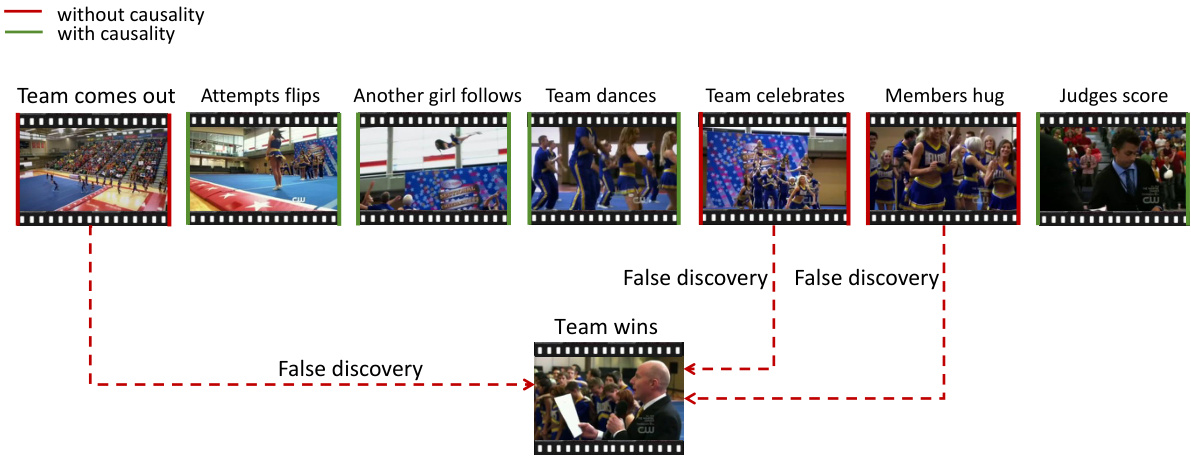

This figure illustrates the Multi-Event Causal Discovery (MECD) task. Panel (a) shows an example video with multiple events and their corresponding visual segments and textual descriptions. The goal is to identify causal relationships between events and represent them as a structured causal diagram, shown in panel (b). Panels (c), (d), and (e) depict three challenges in MECD: causality confounding (where an intermediary event obscures the true causal relationship), illusory temporal causality (where correlation is mistaken for causation due to temporal proximity), and illusory existence causality (where the presence of an object in an earlier event is wrongly interpreted as causation).

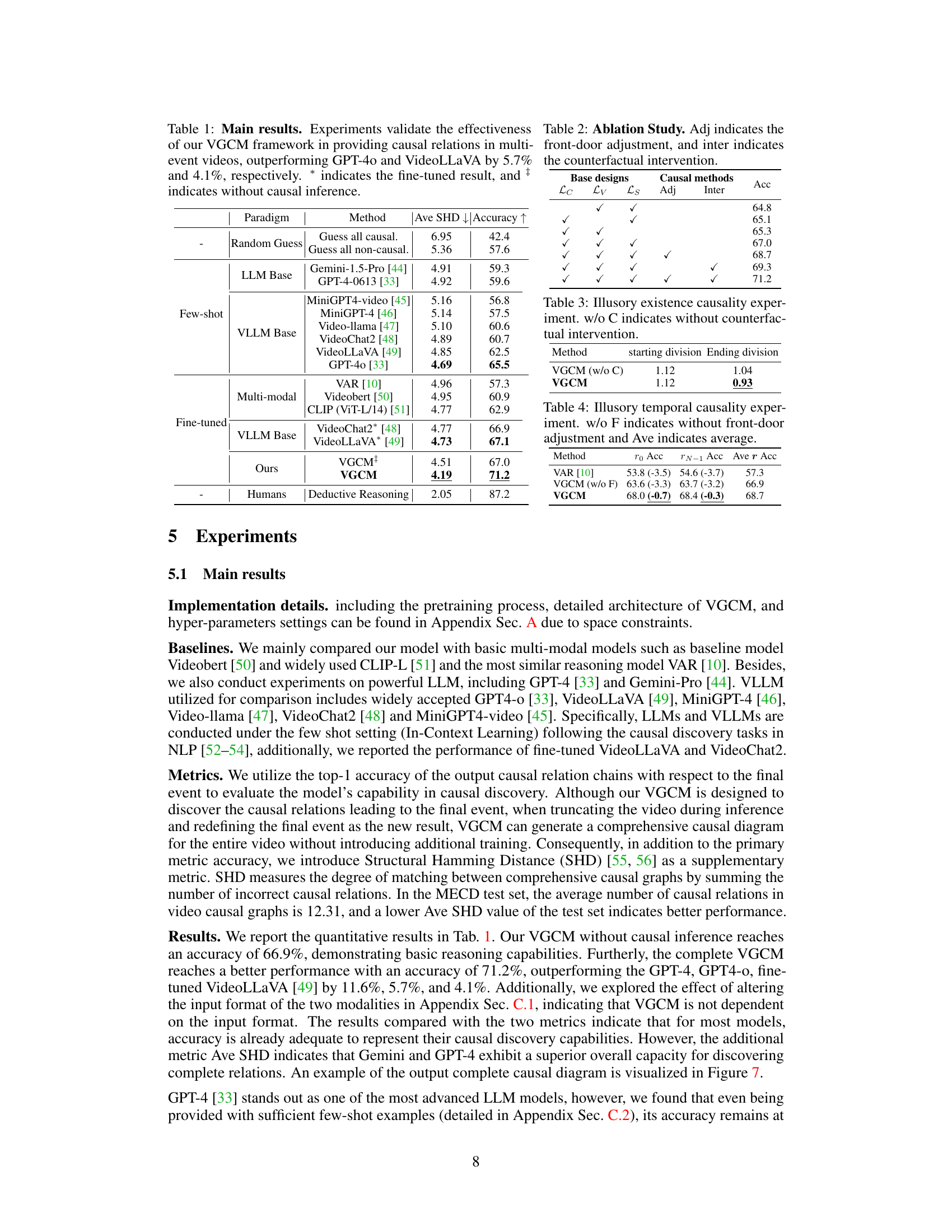

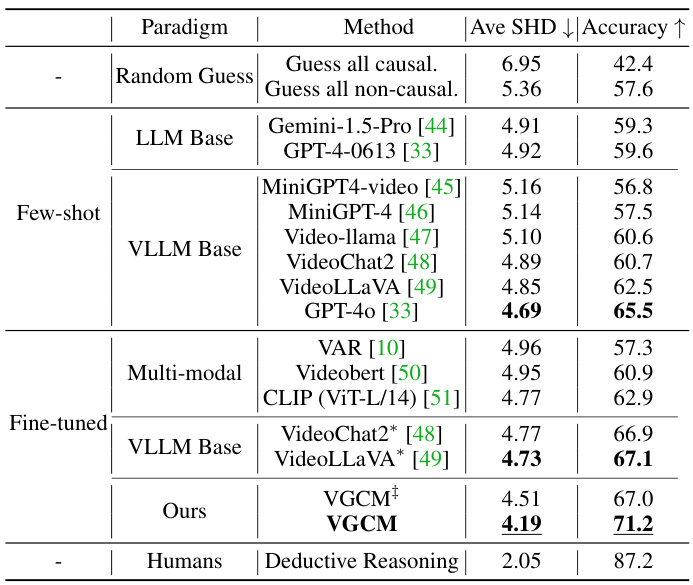

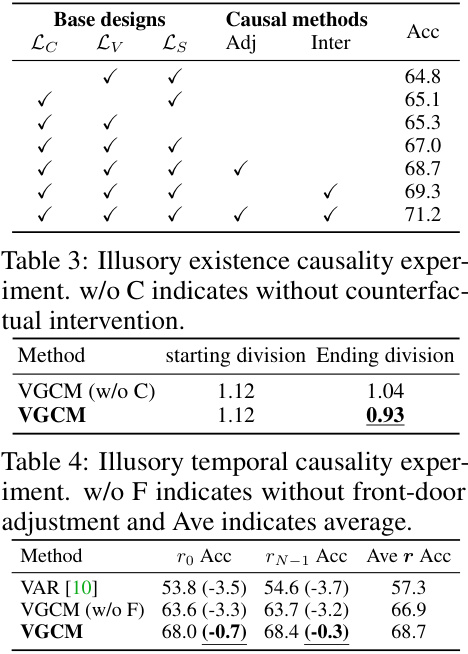

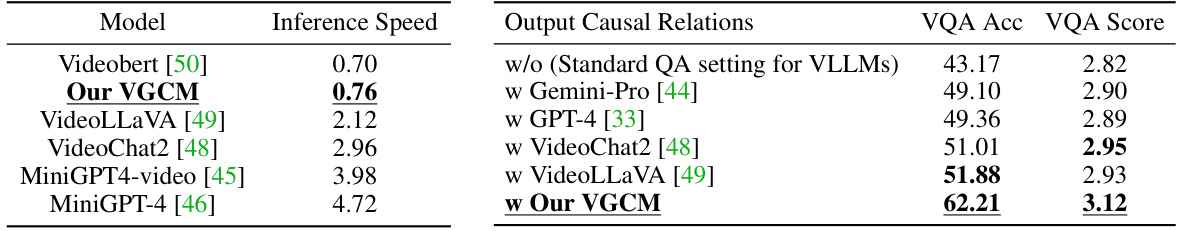

This table presents the main results of the experiments conducted to evaluate the performance of the proposed Video Granger Causality Model (VGCM). It compares VGCM’s accuracy and structural Hamming distance (SHD) against several baseline models, including various LLMs (Large Language Models) and VLLMs (Vision-Language Models) both with and without fine-tuning, and a random guess baseline. The results show that VGCM significantly outperforms these baselines in the multi-event video causal reasoning task. The table also highlights the impact of using causal inference techniques within the VGCM.

In-depth insights#

Multi-Event Causality#

Multi-event causality tackles the complex challenge of understanding causal relationships within video data spanning multiple events. Traditional approaches often fall short, focusing on single-event scenarios. This limitation restricts the ability to model complex chains of events. The key here is moving beyond simplistic cause-and-effect pairs to capture the intricate interplay of several events and their temporal dependencies. Key challenges include disentangling confounding factors where multiple causes influence a single outcome, addressing illusory causality where perceived causal links are spurious correlations, and the inherent ambiguity in defining event boundaries and relationships in long, continuous videos. The ultimate goal is to build models capable of extracting structured causal representations and reasoning paths, facilitating higher-level understanding of video dynamics and potentially enabling applications like advanced video summarization, prediction, and analysis for decision-making.

Granger Causality Test#

The Granger Causality Test, adapted for video analysis, forms a core component of the proposed framework. It leverages the predictive power of a model to infer causality between events. The test’s efficacy hinges on comparing the prediction accuracy of a result event under two scenarios: one where a suspected causal premise event is masked and one where it isn’t. A significant drop in predictive power when the premise event is masked strongly suggests a causal link. However, the paper acknowledges limitations of a direct application in video, citing challenges like causality confounding (where an intermediary event obscures the true causal relationship) and illusory causality (where correlation is misinterpreted as causation). To address these issues, the framework cleverly integrates techniques like front-door adjustment and counterfactual inference to isolate direct causal effects. This sophisticated approach demonstrates a thoughtful consideration of the complexities inherent in video causal reasoning, ultimately moving beyond simple predictive models to a more robust method of causal inference.

Causal Inference#

Causal inference, in the context of video analysis, seeks to establish cause-and-effect relationships between events. This is challenging due to the inherent complexity of videos, involving multiple, temporally distributed events and potential confounding factors. The core challenge lies in distinguishing genuine causal links from mere correlations. Approaches like Granger causality, while useful for time-series data, require adaptation for the multi-modal nature of video data (combining visual and textual information). Mitigating confounding effects is crucial; methods such as front-door adjustment and counterfactual inference help disentangle spurious associations. Successful causal inference demands robust event representation, sophisticated modeling of temporal dynamics, and techniques for handling noisy or incomplete data. The integration of causal inference methods significantly enhances the interpretability and reliability of video understanding systems, moving beyond simple predictive models to uncover the ‘why’ behind observed events.

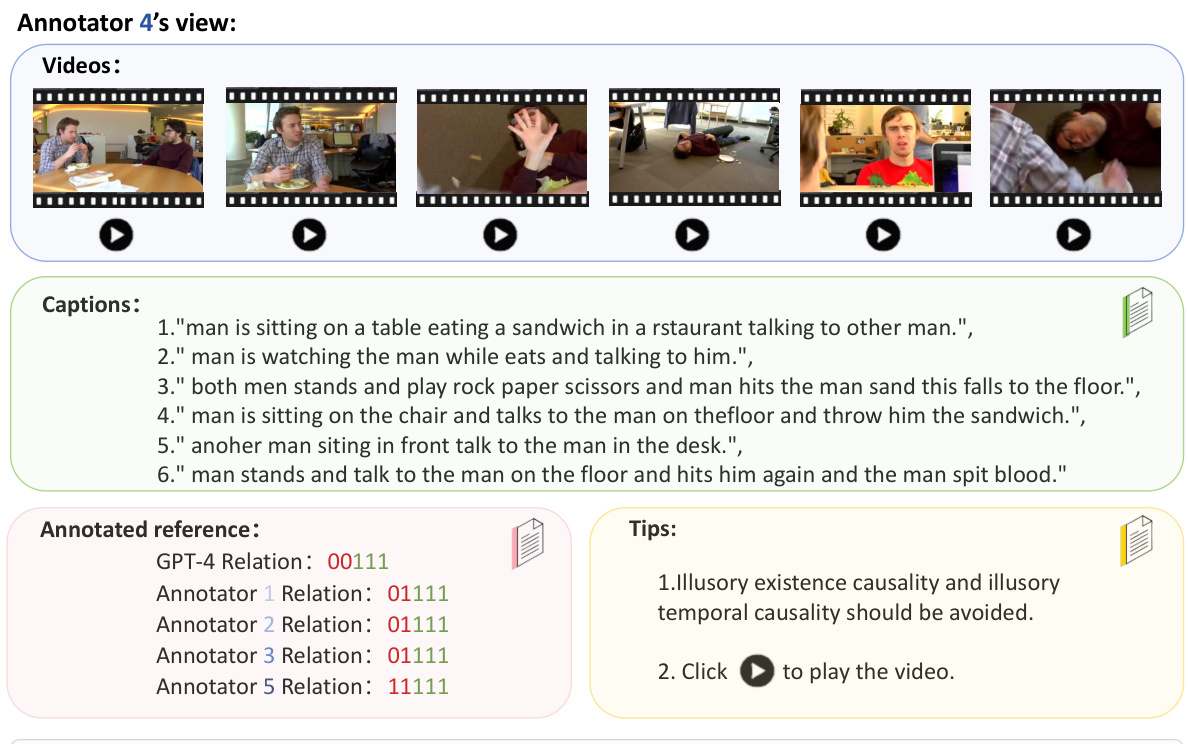

MECD Benchmark#

A robust MECD benchmark is crucial for advancing the field of video causal reasoning. It should include a diverse range of videos showcasing complex, multi-event scenarios and challenging causal relationships. High-quality annotations are essential, requiring careful consideration of causality confounding and illusory causality. The benchmark should facilitate evaluation of different model architectures and inference techniques and provide a platform for researchers to share and compare results. It should also incorporate metrics that measure not only overall accuracy, but also the quality and completeness of the discovered causal diagrams, encouraging the development of more nuanced evaluation strategies. Scalability and extensibility are important considerations, ensuring that the benchmark remains relevant as the complexity and scale of video data grow. Finally, clear guidelines and documentation are necessary to facilitate community participation and adoption, establishing a shared standard for evaluating progress in the field.

Future Directions#

Future research directions in multi-event causal discovery in videos could significantly benefit from improving the robustness and scalability of current methods to handle increasingly complex scenarios with longer videos and more intricate causal relationships. Addressing the challenges of causality confounding and illusory causality remains critical. This could involve exploring advanced causal inference techniques, such as incorporating domain knowledge or developing more sophisticated methods to disentangle direct and indirect causal influences. Enhancing the model’s ability to handle diverse visual and textual modalities, potentially by leveraging multimodal learning architectures, would expand applicability. Furthermore, research into creating larger and more diverse datasets, annotated with both event-level and temporal causal relationships, is crucial for training more robust and generalizable models. Finally, exploring the potential of explainable AI techniques to provide better insights into the reasoning process of the causal discovery models would increase trust and facilitate debugging.

More visual insights#

More on figures

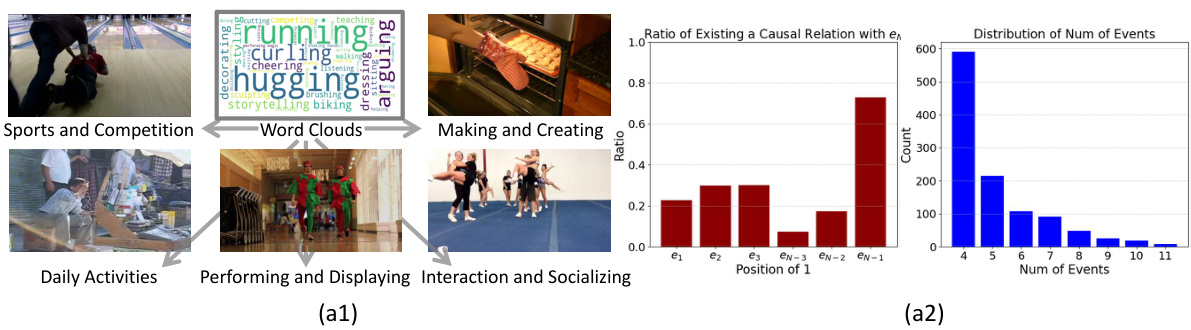

This figure shows the composition of the MECD dataset. (a1) displays five main video categories (Sports & Competition, Making & Creating, Daily Activities, Performing & Displaying, Interaction & Socializing) and a word cloud summarizing the common activities within each category. (a2) shows two graphs: the first graph shows the relationship between the position of an event and its likelihood of having a causal relation with the final event, with the second-to-last event being the most influential; and the second graph is a histogram illustrating the distribution of the number of events per video in the dataset.

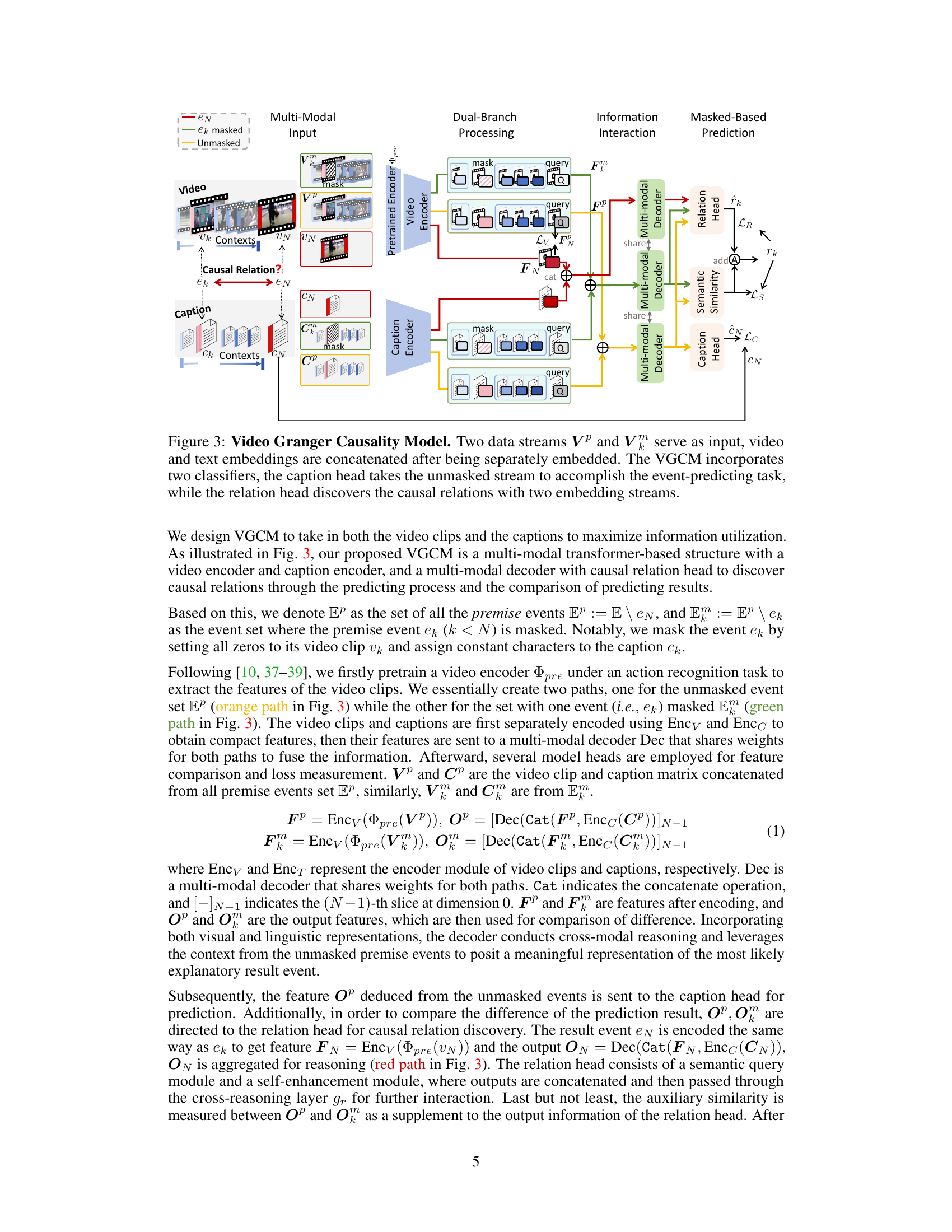

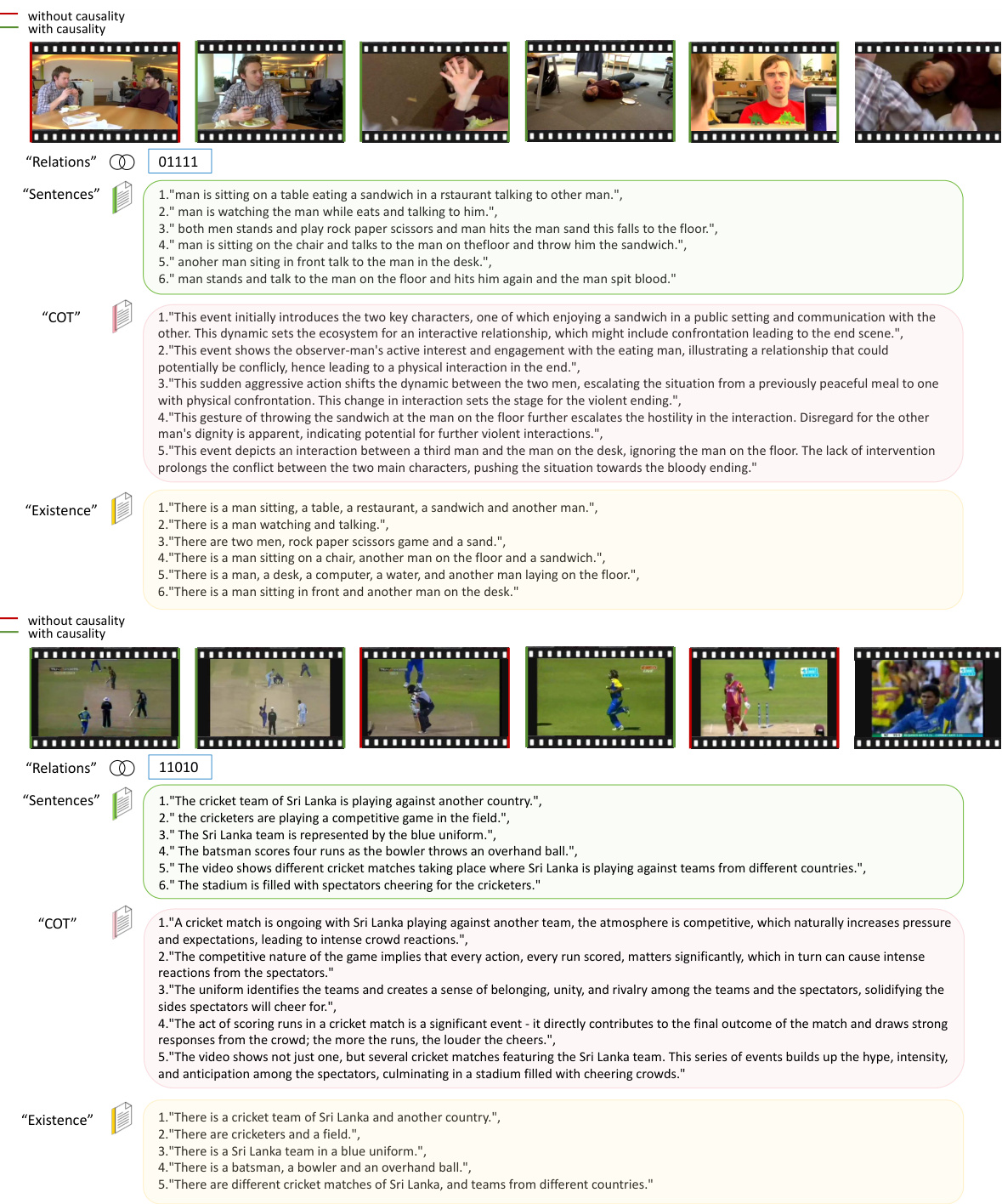

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Video Granger Causality Model (VGCM). The model takes video and caption data as input, processes them through separate video and caption encoders. These encodings are then fed into a multi-modal decoder, which has two branches. One branch uses all premise events (unmasked) to predict the result event, while the other masks a single premise event at a time to assess its causal impact. The results are then compared by a relation head that determines whether a causal relation exists between the premise and result events, alongside a caption head to predict the textual description of the result event.

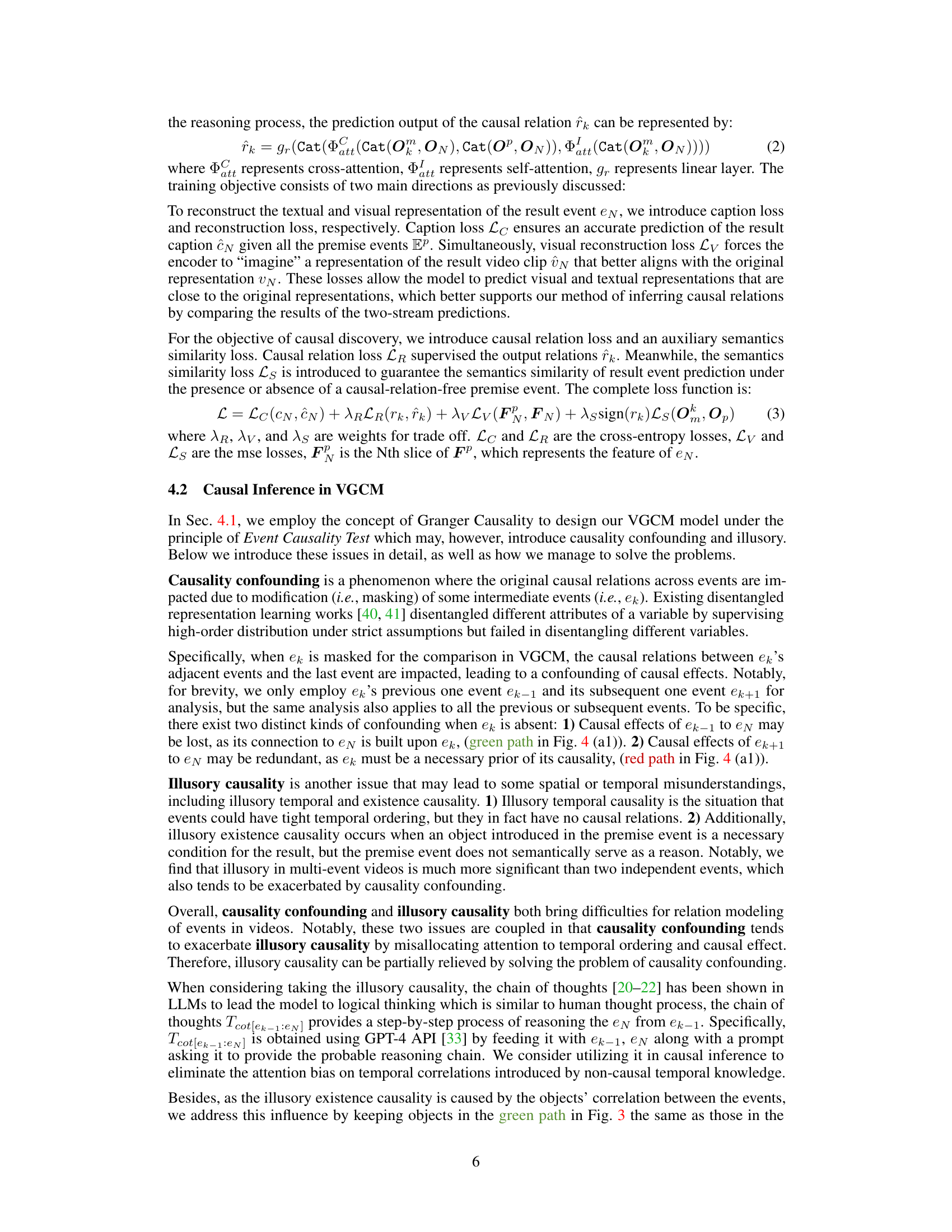

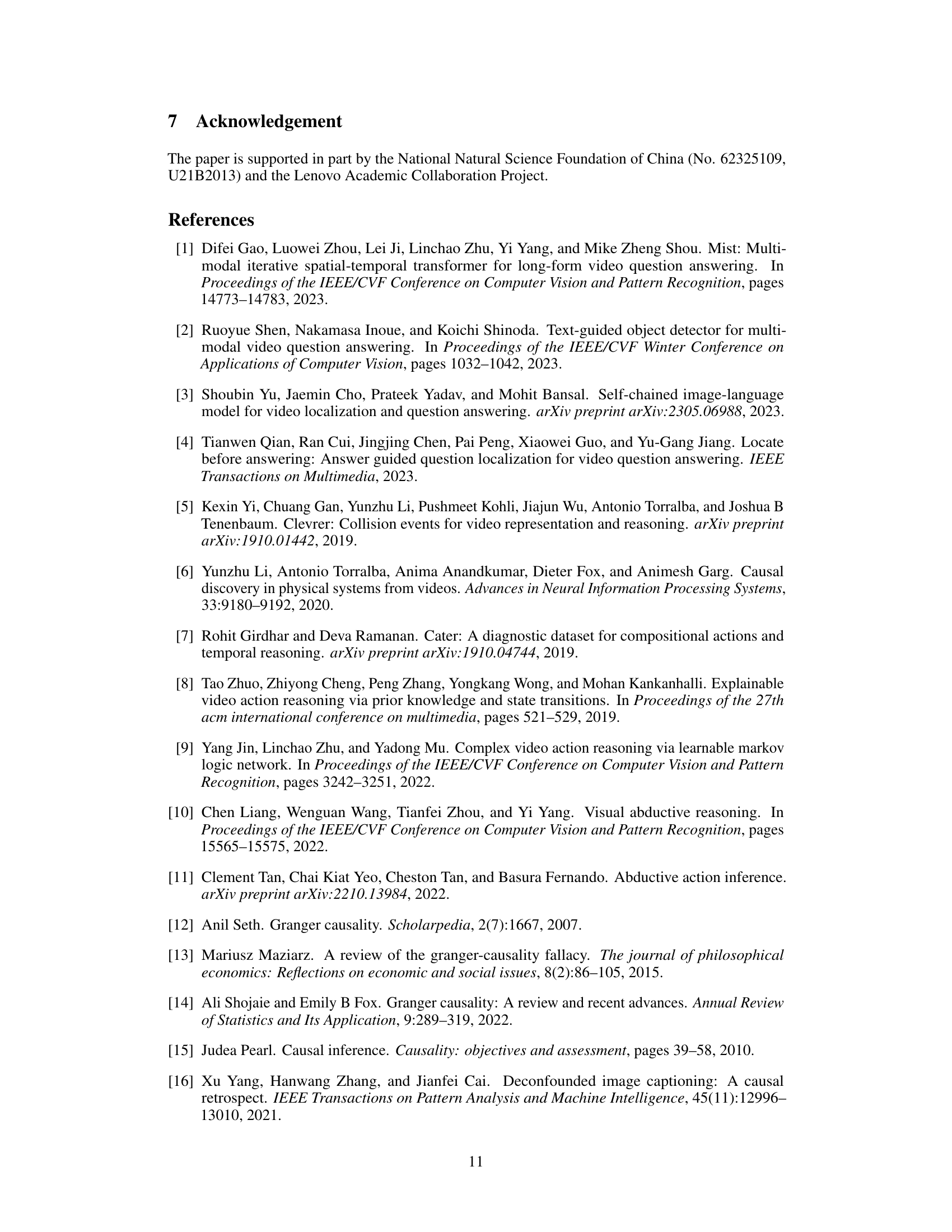

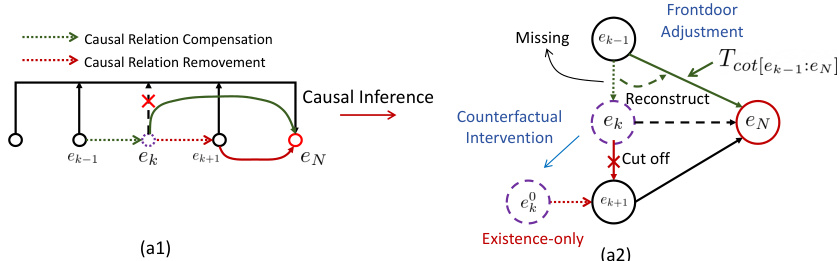

This figure illustrates how causality confounding and illusory causality affect causal relationships in multi-event videos. Panel (a1) shows a simplified causal diagram with three events (ek-1, ek, ek+1) leading to a result event (eN). When the middle event (ek) is masked (removed from consideration), the direct causal effect from ek-1 to eN is lost (blue dotted line), and a spurious causal link between ek+1 and eN might appear (red dotted line). Panel (a2) details the methods to handle this: Frontdoor adjustment addresses the missing link from ek-1 to eN; Counterfactual intervention removes the spurious link from ek+1 to eN; and an Existence-only path addresses the issue of illusory existence causality.

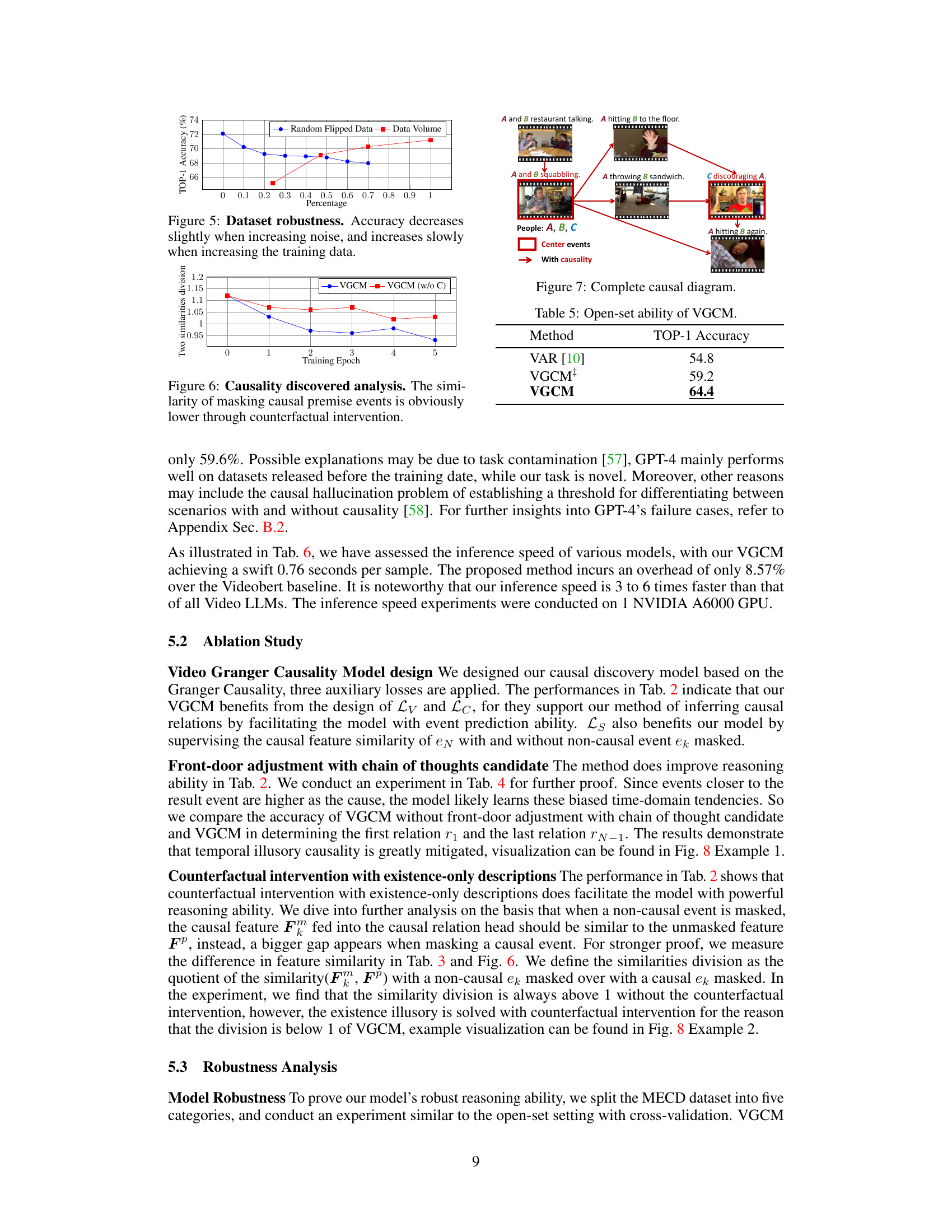

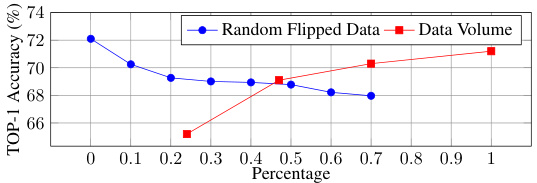

This figure shows the robustness of the MECD model to different factors such as noise in the data and the amount of training data. The blue line shows the accuracy when a random percentage of the causal relations are flipped, simulating noise in the data. The red line shows the accuracy as the amount of training data increases. As can be seen, the model is relatively robust to both noise and variations in the amount of training data.

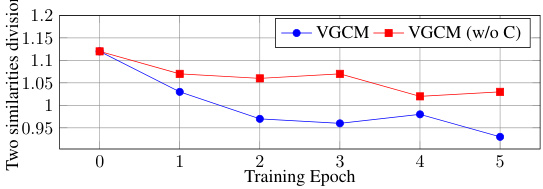

This figure shows the results of an ablation study evaluating the impact of counterfactual intervention on the similarity between the output features with and without masking a causal premise event. The x-axis represents the training epoch, and the y-axis represents the ratio of similarities between output features with and without masking. The blue line represents the results with counterfactual intervention, and the red line represents the results without it. The figure demonstrates that counterfactual intervention effectively reduces the similarity between the output features when masking a causal premise event, indicating its effectiveness in mitigating causality confounding and improving the accuracy of causal discovery.

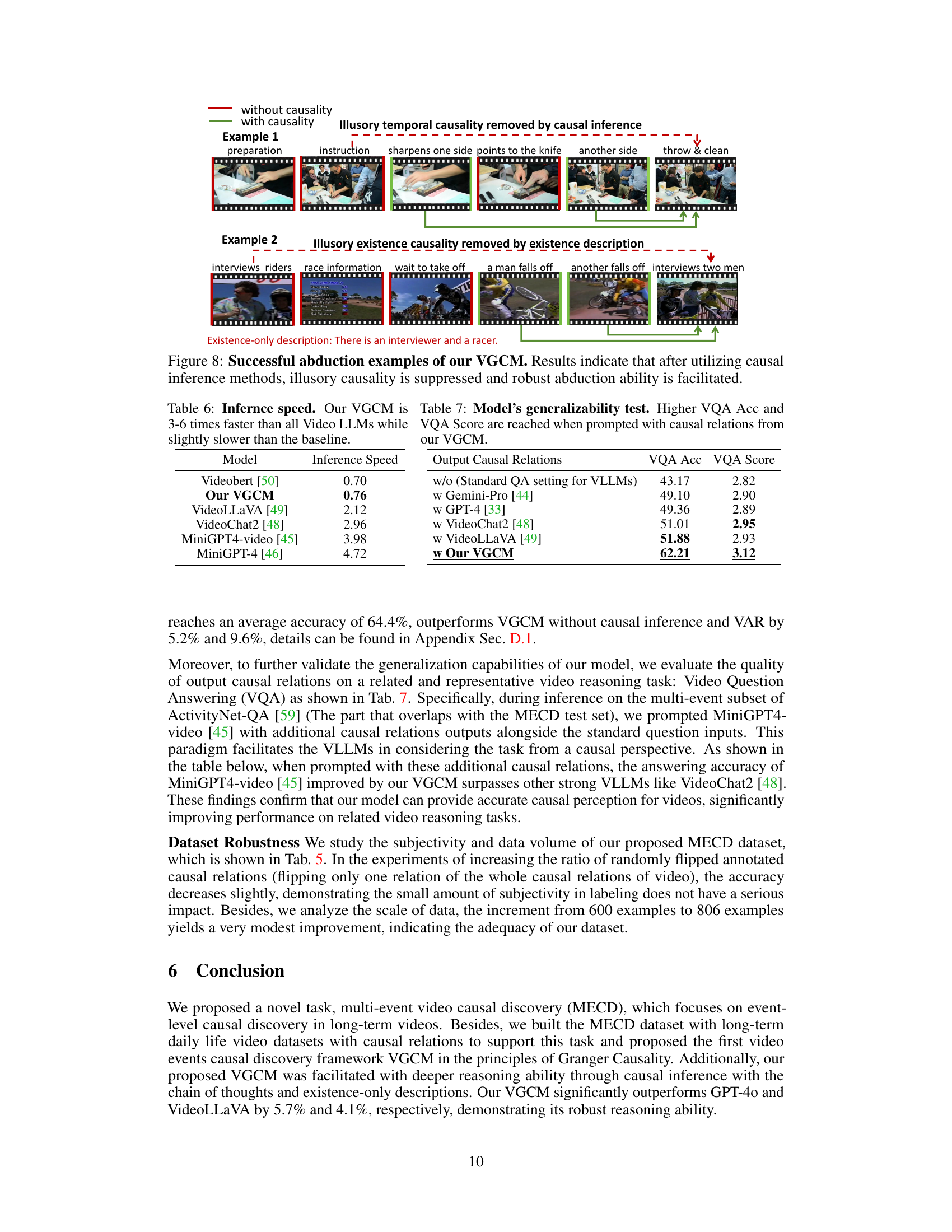

This figure visualizes a complete causal diagram generated by the VGCM model. The diagram shows multiple events chronologically arranged and connected by causal links. These links indicate how premise events causally influence the result event. The diagram effectively demonstrates the model’s ability to represent complex multi-event causal relationships in a structured format.

This figure illustrates the impact of masking an intermediate event (ek) on the causal relationships between adjacent events and the final event (en). Panel (a1) shows how masking ek can lead to either a missing causal effect (red arrow) from the event before ek (ek-1) to en, or a redundant causal effect (blue arrow) from the event after ek (ek+1) to en. Panel (a2) demonstrates how causal inference techniques, specifically front-door adjustment and counterfactual intervention, are used to address these issues of confounding. Front-door adjustment is used to compensate for the missing causal effect while counterfactual intervention is used to remove the redundant causal effect. The chain of thoughts and existence-only descriptions help to mitigate illusory causality.

This figure illustrates the concept of causality confounding and illusory causality and how the proposed method addresses these challenges. Panel (a1) shows a causal chain where the removal of an intermediate event (ek) affects the causality between other events, requiring compensation (red) and removal (blue) of causal effects. Panel (a2) details the causal inference techniques (front-door adjustment and counterfactual inference) used to address these issues, resulting in a more accurate representation of causality.

This figure shows a complete causal diagram generated by the VGCM model. It visually represents the causal relationships between multiple events in a video, illustrating how premise events contribute to the final result event. The diagram provides a comprehensive and structured overview of the causal chain, allowing for a clearer understanding of the complex interactions between various events.

This figure illustrates the causal effects of adjacent events when a premise event (ek) is masked in the Video Granger Causality Model (VGCM). Panel (a1) shows how masking ek disrupts the causal relationships, causing a confounding effect. The red arrows represent causal effects that are lost (missing) because ek is masked, requiring compensation. The blue arrows represent causal effects that are redundant because ek is masked and can be removed. Panel (a2) depicts the causal inference methods, front-door adjustment and counterfactual inference, used by VGCM to compensate for the missing effects and remove redundant ones. The introduction of chain of thoughts and existence-only descriptions are also highlighted to address illusory causality.

This figure showcases instances where GPT-4 incorrectly identifies causal relationships in videos. The errors stem from two main sources: confusing correlations with causality (illusory causality) and misinterpreting emotional expressions as causal factors. The examples highlight how GPT-4 struggles to differentiate between objective causal links and subjective interpretations of events, leading to inaccurate causal inferences.

This figure illustrates the Multi-Event Causal Discovery (MECD) task. Panel (a) shows an example of the task, where multiple premise events (events leading up to the final event) are shown chronologically, along with their corresponding video segments and textual descriptions. The goal is to determine causal relationships between the premise events and the final result event, and represent these relationships in a causal diagram. Panels (c), (d), and (e) illustrate confounding and illusory causality, which are challenges the MECD task addresses.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Video Granger Causality Model (VGCM). The model takes video and caption data as input, processes them through separate encoders, and then fuses the information in a multi-modal decoder. Two heads, a caption head and a relation head, are used for event prediction and causal relation discovery, respectively. The caption head predicts the result event based on the unmasked premise events, while the relation head identifies causal relationships by comparing predictions with and without masking premise events. This allows for the determination of causal links between events.

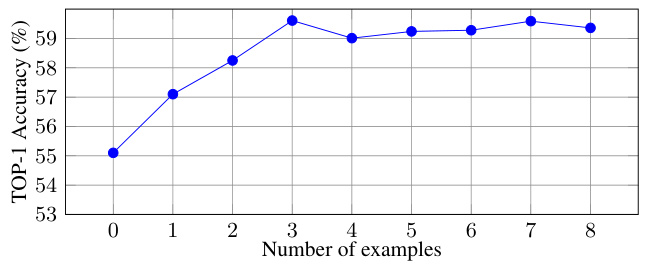

This figure shows how the accuracy of the model changes as the number of examples in few-shot learning increases. The x-axis represents the number of examples used, and the y-axis represents the top-1 accuracy. The accuracy shows a slight increase with an increasing number of examples until it plateaus after around 3 examples. This suggests that adding more examples beyond a certain point provides minimal additional benefit to the model’s performance.

More on tables

This table presents the main results of the experiments conducted to evaluate the performance of the proposed Video Granger Causality Model (VGCM) for multi-event video causal discovery. It compares the accuracy of VGCM against several baseline models, including traditional multi-modal models, large language models (LLMs), and video-LLMs. The results show that VGCM outperforms the state-of-the-art models, demonstrating its effectiveness in discovering causal relations within multi-event videos. The table also includes results with and without causal inference methods integrated into the VGCM, highlighting their impact on performance.

This table presents the main results of the experiments conducted to evaluate the performance of the proposed Video Granger Causality Model (VGCM). It compares the accuracy of VGCM against several baseline models, including various LLMs and VLLMs, in the task of multi-event causal discovery. The table highlights that VGCM outperforms other models, particularly GPT-4 and VideoLLaVA, demonstrating its effectiveness in identifying causal relationships within long videos containing multiple events. It also shows results with and without causal inference applied and indicates which models were fine-tuned.

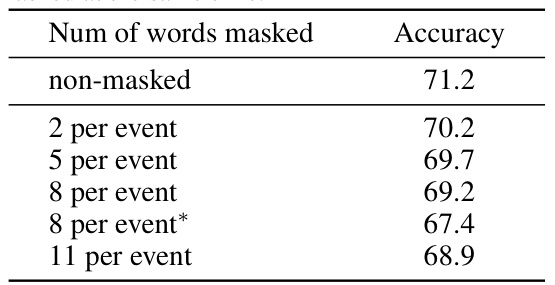

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the Video Granger Causality Model (VGCM). The experiment explores the impact of masking different numbers of words from the caption of each premise event on the model’s accuracy in predicting causal relationships. The accuracy is evaluated under different masking scenarios (2, 5, 8, and 11 words per event). A separate row shows the accuracy when 30 frames are masked at the same time.

This table presents the results of an ablation study conducted to evaluate the impact of masking visual input (video frames) on the performance of the Video Granger Causality Model (VGCM). The model’s accuracy in predicting causal relations is measured under different levels of visual masking (5, 15, 20, and 40 frames masked per event). A comparison is made with a non-masked condition for baseline accuracy. The impact of simultaneous masking of both visual and textual data is also examined by comparing the accuracy of masking 20 frames and 10 words compared to only masking 20 frames.

Full paper#