↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many stochastic models in science and engineering are naturally infinite-dimensional. Conditioning these models to incorporate observed data is challenging, particularly for nonlinear processes. Existing methods often rely on discretization, which can introduce inaccuracies and limitations. This paper addresses these challenges.

This research introduces a novel approach using an infinite-dimensional version of Doob’s h-transform and score-matching techniques. The method allows conditioning without prior discretization. It is successfully applied to analyze the shapes of organisms evolving over time. The results demonstrate the feasibility and effectiveness of the approach in handling complex, infinite-dimensional data, paving the way for broader applications in various fields.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel method for conditioning nonlinear, infinite-dimensional diffusion processes, a significant challenge in various fields. This opens new avenues for analyzing function-valued data such as shapes in evolutionary biology and medical imaging, offering improved modeling capabilities beyond existing finite-dimensional techniques. The method also has implications for generative modeling and time series analysis in infinite dimensions.

Visual Insights#

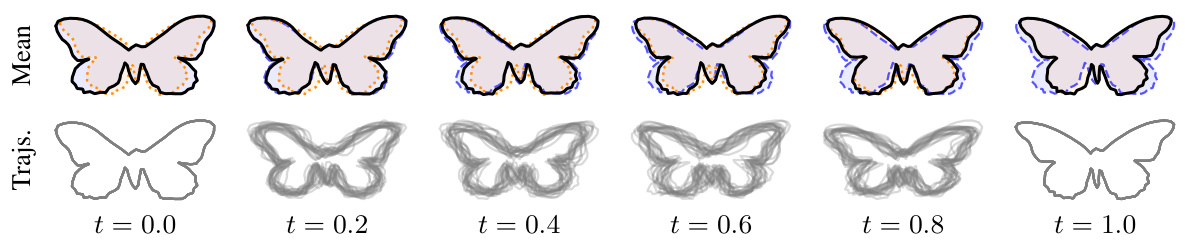

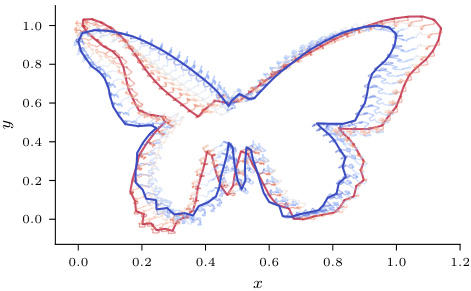

This figure shows the result of conditioning a stochastic differential equation (SDE) between two curves representing butterfly shapes. The top row displays the average shape at different time points across 20 simulated trajectories, while the bottom row visualizes each individual trajectory. The conditioning ensures that the SDE starts from one butterfly shape and ends at another, illustrating how the method smoothly transitions between the shapes.

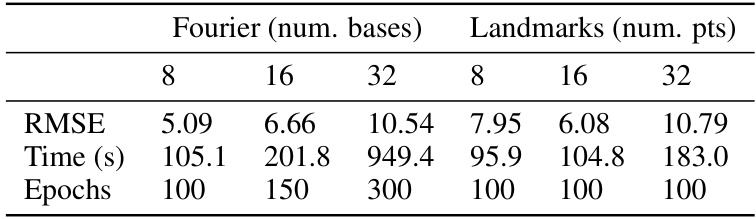

This table compares the root mean squared error (RMSE), training time, and number of epochs for training the score function of a Brownian motion process using two different discretization methods: Fourier basis and landmarks. The comparison is made for different numbers of basis functions/landmarks (8, 16, 32). The results show the trade-off between accuracy (RMSE), computational cost (Time), and training time (Epochs).

In-depth insights#

Infinite SDEs#

The concept of “Infinite SDEs” in the context of a research paper likely refers to stochastic differential equations (SDEs) defined in infinite-dimensional spaces. This is a significant departure from classical SDEs, which typically operate in finite-dimensional Euclidean spaces. The infinite-dimensionality introduces substantial mathematical challenges, requiring the use of advanced tools from functional analysis and stochastic calculus. Key considerations include the choice of appropriate function spaces (e.g., Hilbert spaces) and the definition of stochastic integration in these infinite-dimensional settings. The paper likely explores techniques to handle the complexities of infinite SDEs, such as Galerkin approximations or spectral methods to reduce the problem to a finite-dimensional system. A major focus might be on establishing the existence and uniqueness of solutions, and perhaps on developing numerical methods for approximation. The study could involve investigating specific types of infinite SDEs, possibly linked to applications in fields like stochastic partial differential equations (SPDEs) or generative models for function-valued data. The theoretical contributions would likely revolve around proving well-posedness results (existence, uniqueness, stability) under specific conditions, and possibly developing novel approximation schemes with error analysis. Practical applications might involve modelling complex systems with an infinite number of degrees of freedom, e.g., fluid dynamics or evolutionary biology.

Doob’s Transform#

The concept of Doob’s transform, when extended to infinite dimensions, presents a powerful tool for conditioning stochastic processes. The paper elegantly tackles the challenges of applying this transform to infinite-dimensional, non-linear diffusion processes, a significant advancement. Conditioning without prior discretization is a key innovation, allowing for a more natural and accurate representation of function-valued data. The authors’ use of Girsanov’s theorem in infinite dimensions is particularly insightful, providing a rigorous framework for deriving the conditioned process. The resulting stochastic differential equation (SDE) involves the score function, highlighting its crucial role in characterizing the conditional distribution. While the theoretical framework is strong, the practical implementation involves approximations, notably through the use of Fourier basis and score matching. Future directions, as noted, could involve deeper investigation into the approximation methods and their effect on accuracy, especially for high-dimensional settings. The application to time series analysis of organism shapes showcases the potential of the proposed method in evolutionary biology and related fields. Overall, the theoretical contributions are substantial, opening new avenues for modeling and inference within infinite-dimensional stochastic processes.

Score Matching#

Score matching is a powerful technique in machine learning used to estimate the gradient of a probability density function without explicitly knowing the function itself. This is particularly useful when dealing with complex, high-dimensional data where directly calculating the density is intractable. The core idea is to learn a model that approximates the score function, which is the gradient of the log-probability density. This approach leverages the fact that the score function can be estimated from samples from the target distribution using various methods, avoiding the need to explicitly model the probability density. Once the score function is learned, it can be used in various applications, such as generative modeling and data analysis. Different score matching methods exist, each with its advantages and disadvantages. For instance, some focus on minimizing a particular loss function, while others involve learning the score function via stochastic differential equations. The effectiveness of score matching often depends on the choice of model architecture, training procedure, and the nature of the target data distribution. High-dimensional settings present considerable challenges, and the choice of the model, especially for parameterizing the score function, critically impacts performance. Therefore, the scalability and robustness of score matching methods remain a crucial area of ongoing research. It also shows great promise and holds a prominent position in the field of generative modeling. Its ability to circumvent the challenges of explicitly working with probability densities makes it a valuable tool for tackling complex data generation challenges.

Shape Analysis#

Shape analysis, in the context of this research paper, appears to be a crucial application area for the developed infinite-dimensional stochastic process conditioning methods. The paper highlights the challenges of traditional shape analysis techniques when dealing with high-dimensional or infinite-dimensional shape data, particularly in evolutionary biology. The core innovation is the ability to condition infinite-dimensional diffusion processes representing shapes without requiring prior discretization. This allows for a more accurate and nuanced representation of shape evolution over time, especially valuable when studying the complex transformations of organism shapes across evolutionary lineages. The method’s effectiveness is demonstrated through experiments on butterfly shapes, showcasing its ability to model shape changes over time while accurately incorporating observed data. A key advantage lies in treating shapes directly as infinite-dimensional objects, circumventing the limitations of finite-dimensional approximations that can lead to information loss. The paper suggests broader implications for various shape analysis problems, including phylogenetic inference and medical imaging, by providing more accurate and robust modeling techniques for shape evolution and comparison.

Future Work#

The authors outline several promising avenues for future research. Extending the framework to non-strong solutions is a key goal, acknowledging the current reliance on Itô’s formula as a limitation. Further investigation into the network architecture for score learning, particularly for higher-dimensional SDEs, is suggested, as the current approach’s scalability is noted as a potential limitation. The paper also highlights the need to improve the efficiency of learning the forward bridge directly, rather than the current two-step process involving the time reversal. Finally, and perhaps most significantly, they emphasize the importance of extending the infinite-dimensional bridge methods towards addressing broader inference problems in a phylogenetic context, particularly for evolutionary biology and morphometric shape analysis.

More visual insights#

More on figures

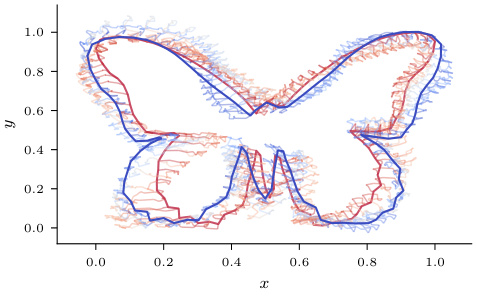

This figure shows a sample trajectory from a stochastic process that models the change in shape between two butterfly species. The red line represents the starting shape (Papilio polytes), and the blue line shows the ending shape (Parnassius honrathi). The intermediate shapes along the trajectory show how the shape changes over time according to the stochastic process.

This figure visualizes the result of conditioning a stochastic differential equation (SDE) between two curves representing shapes of two butterfly species. The SDE’s trajectory, representing shape evolution over time, is conditioned to start at one curve (red dashed line) and end at another (green dashed line). The top row displays the average shape of 20 simulated trajectories, while the bottom row shows the individual trajectories used to compute the average. This demonstrates the method of conditioning infinite-dimensional processes, a core contribution of the paper.

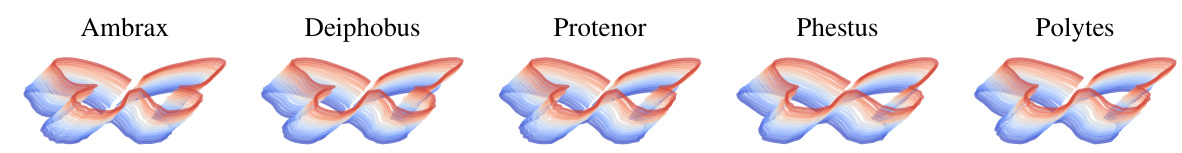

This figure displays five butterflies from closely related species. A mean butterfly shape is calculated from the dataset of 40 butterflies. The figure then shows single trajectories starting from this mean butterfly shape at time t=0 and ending at a representative butterfly from each of the five species at t=1.

This figure shows a stochastic process, essentially a random path, connecting two different butterfly shapes. The red outline represents the starting shape (Papilio polytes), and the blue outline represents the ending shape (Parnassius honrathi). The intermediate shapes along the path illustrate the evolution of the shape from start to finish. This is an example of how the authors apply their method to shape data in evolutionary biology.

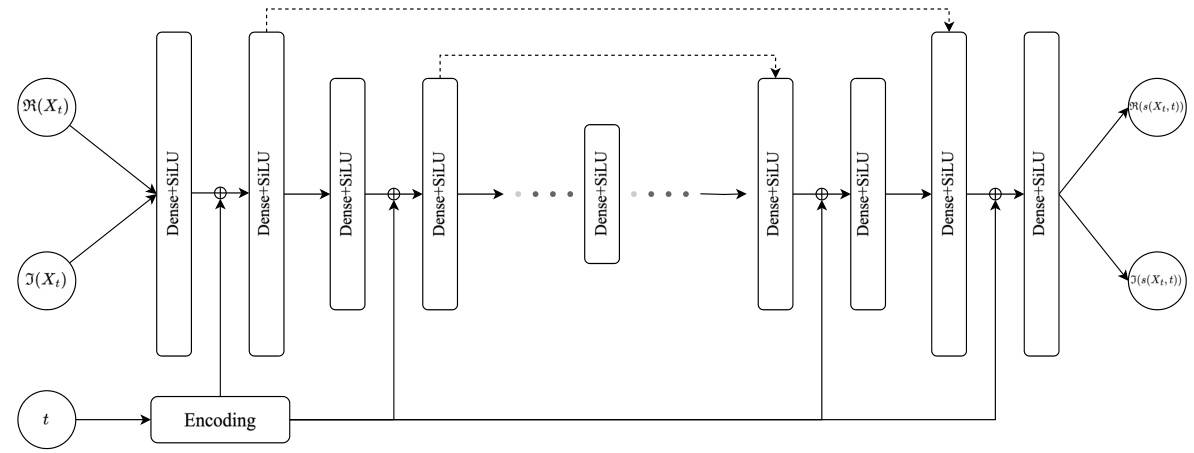

This figure shows the architecture of the neural network used to approximate the discretised score function. It is a U-net architecture with skip connections, where each layer consists of two dense layers using SiLU activation functions. Batch normalization is applied after each layer. The time step information is encoded using sinusoidal embedding and added to the output of the dense layers element-wise.

This figure visualizes the effect of varying the covariance (σ) of the Gaussian kernel and the number of basis elements (N) on the trajectory of a circle undergoing a stochastic process defined by a stochastic differential equation (SDE). Each row represents a different number of basis elements (N=8, 16, and 24), while each column shows the result for a different value of covariance (σ=0.1, 0.5, and 1.0). The images depict the shape of the circle at six different time points (t=0.0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0) as it evolves according to the SDE. The visual demonstrates how changes in the covariance and the number of basis elements affect the smoothness and complexity of the shape’s evolution over time.

Full paper#