↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

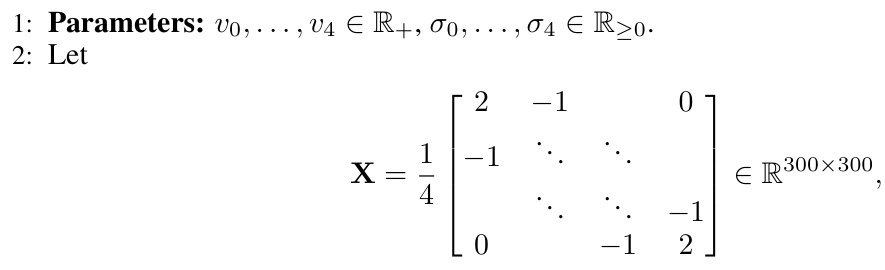

Many large-scale machine learning tasks rely on distributed optimization, where multiple devices collaboratively train a model. However, communication between devices and a central server is often a bottleneck due to the large size of models and network limitations. This paper focuses on improving communication efficiency by reducing the amount of data transferred. Current methods often struggle to minimize server-to-worker communication costs, especially in nonconvex settings (where the optimization problem is more difficult).

This research introduces two novel algorithms, MARINA-P and M3, designed to efficiently compress data sent from the server to the worker nodes. MARINA-P uses a technique called correlated compressors to reduce downlink communication, demonstrating theoretical improvements that are confirmed by experiments. M3 goes further by incorporating both uplink and downlink compression, further boosting efficiency and showcasing that communication complexity can improve with more worker nodes. The algorithms show that carefully designed compression can significantly improve communication efficiency without sacrificing model accuracy. These findings are particularly important for applications with limited bandwidth or a large number of worker nodes, like federated learning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in distributed optimization and federated learning. It directly addresses the critical issue of communication efficiency, a major bottleneck in large-scale machine learning. By proposing novel algorithms like MARINA-P and M3 with provable improvements in communication complexity, this work offers significant practical advantages and opens exciting avenues for future research in communication-efficient distributed optimization.

Visual Insights#

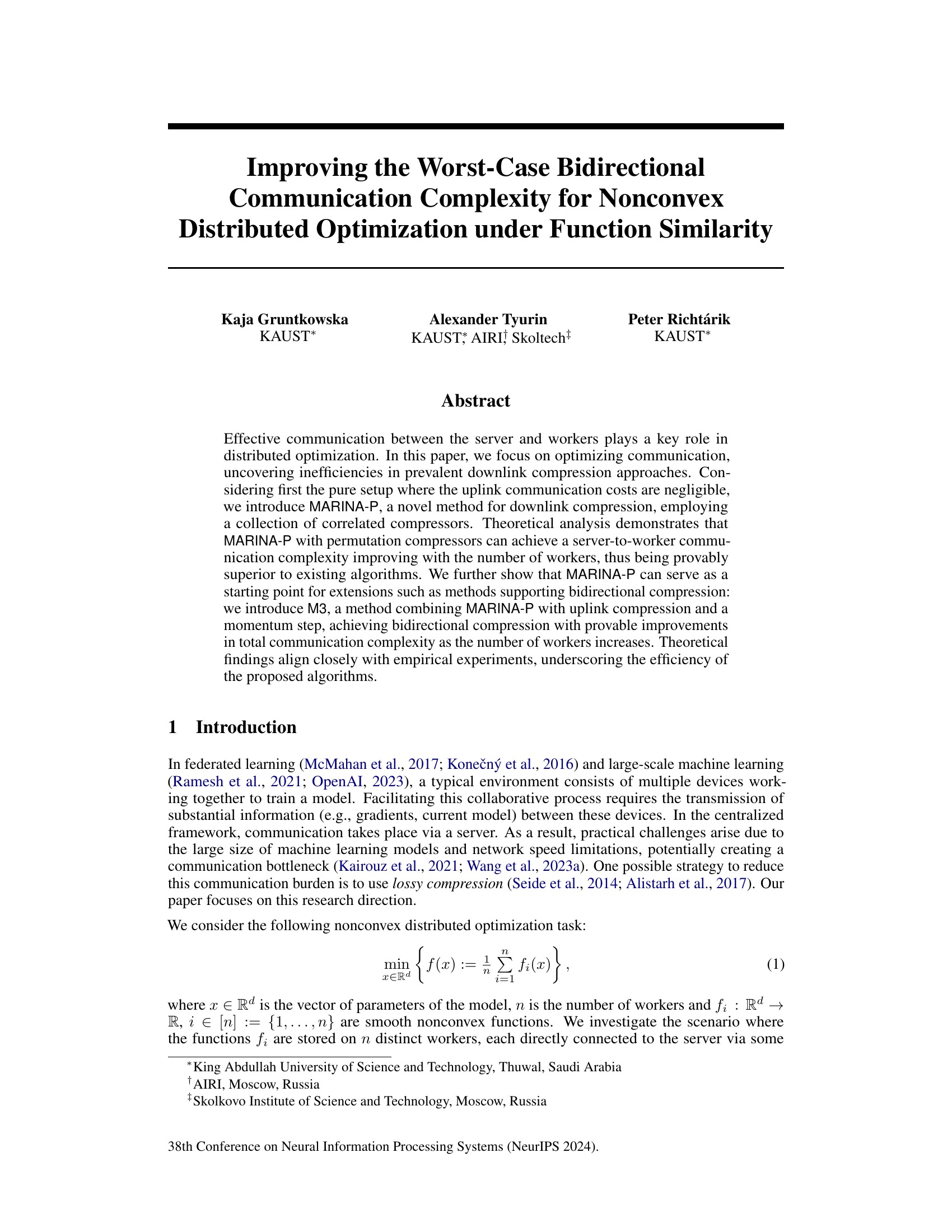

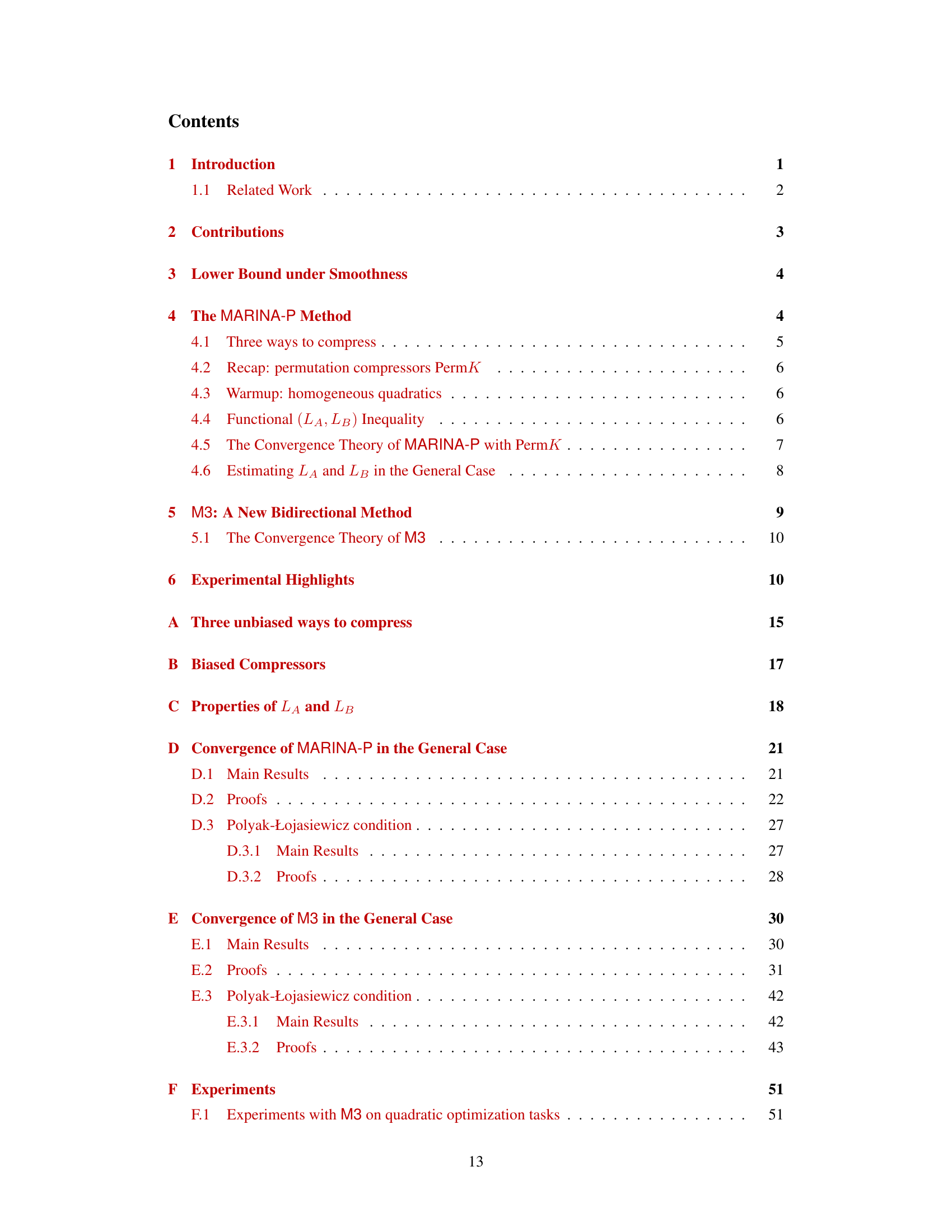

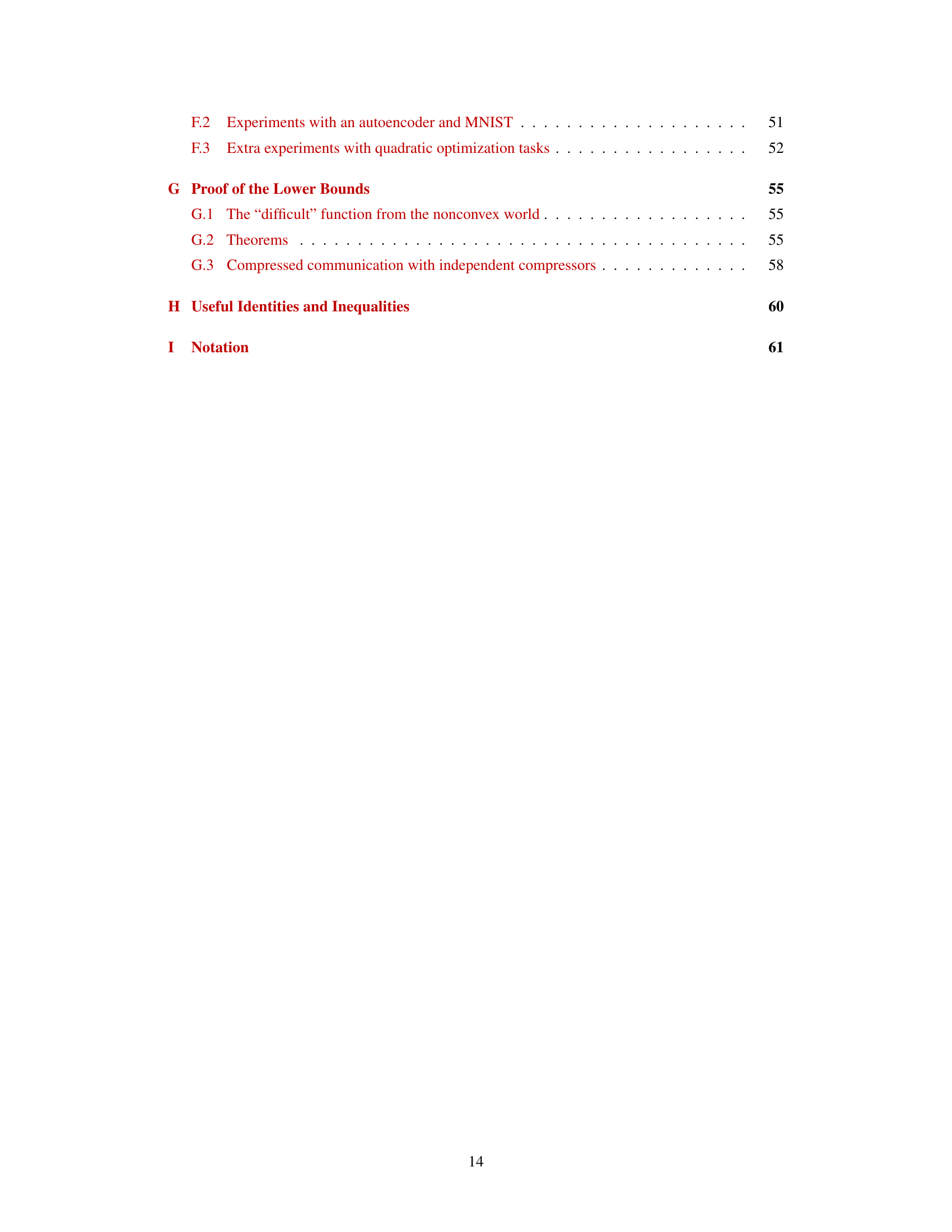

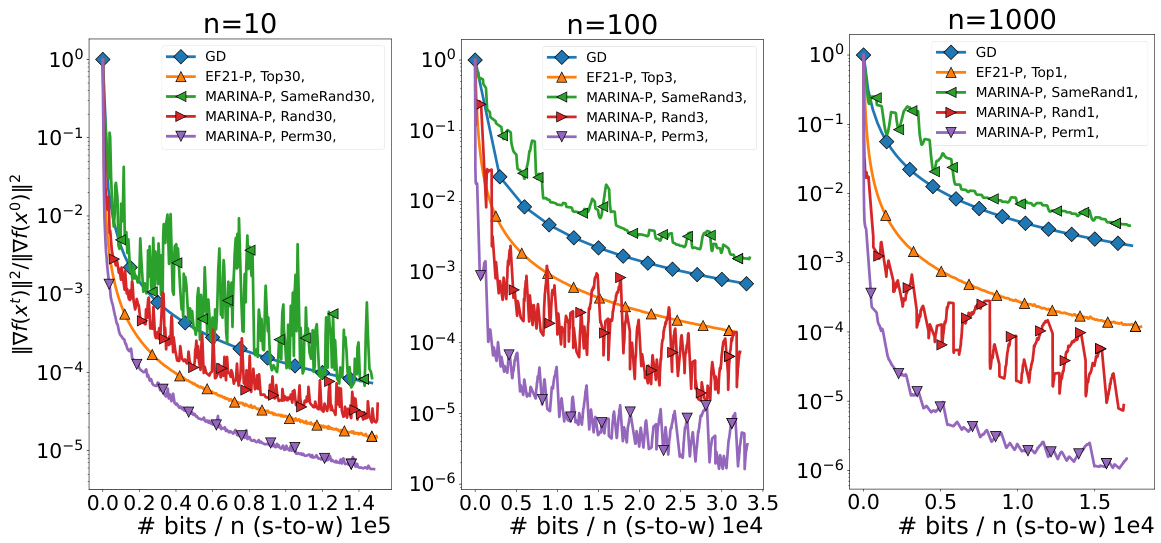

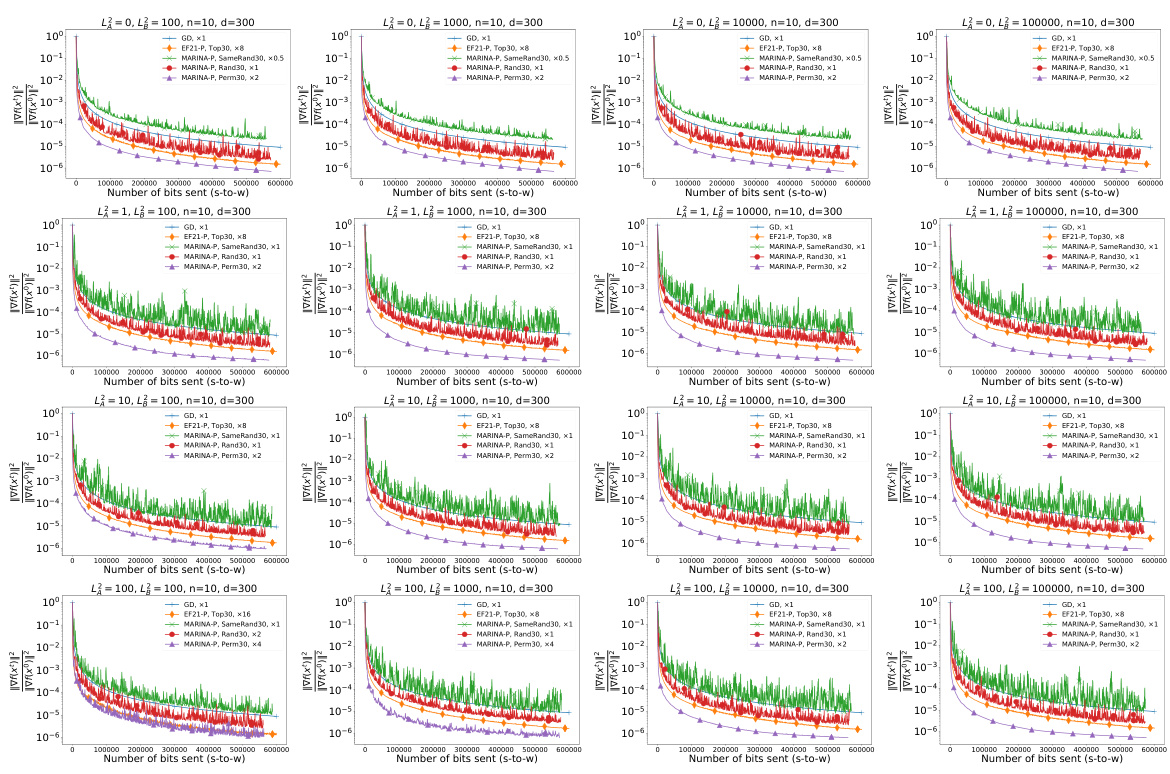

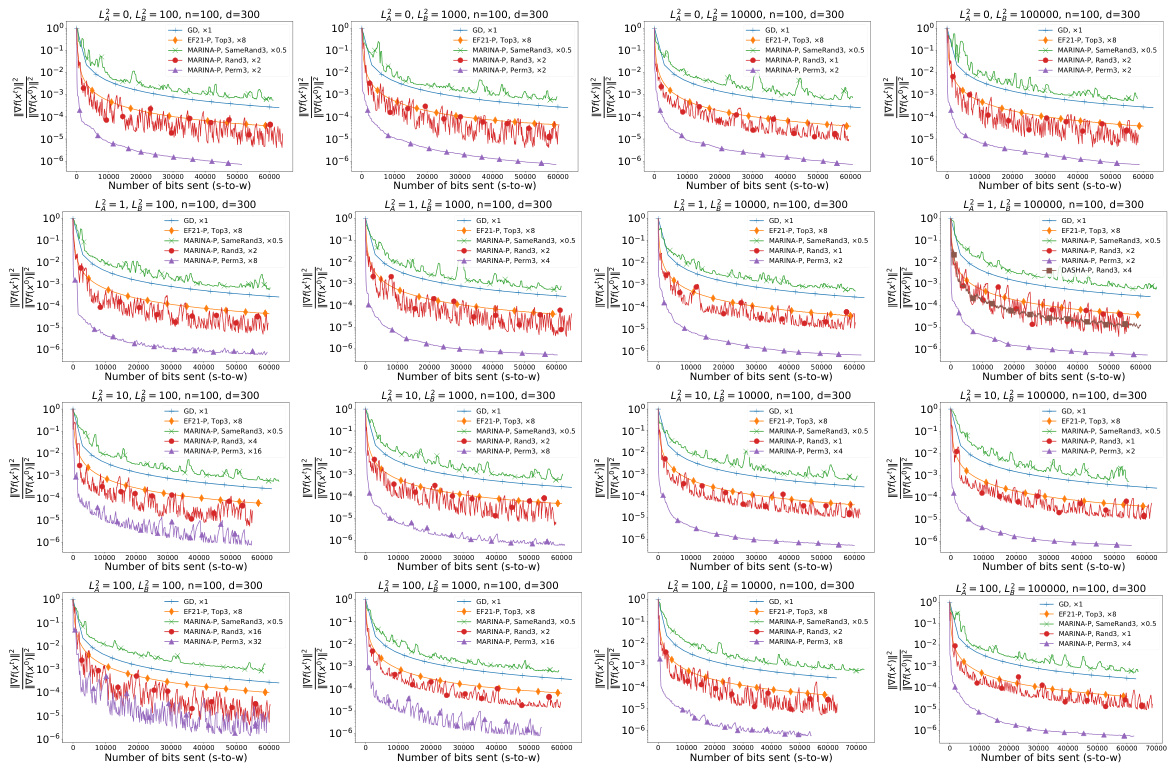

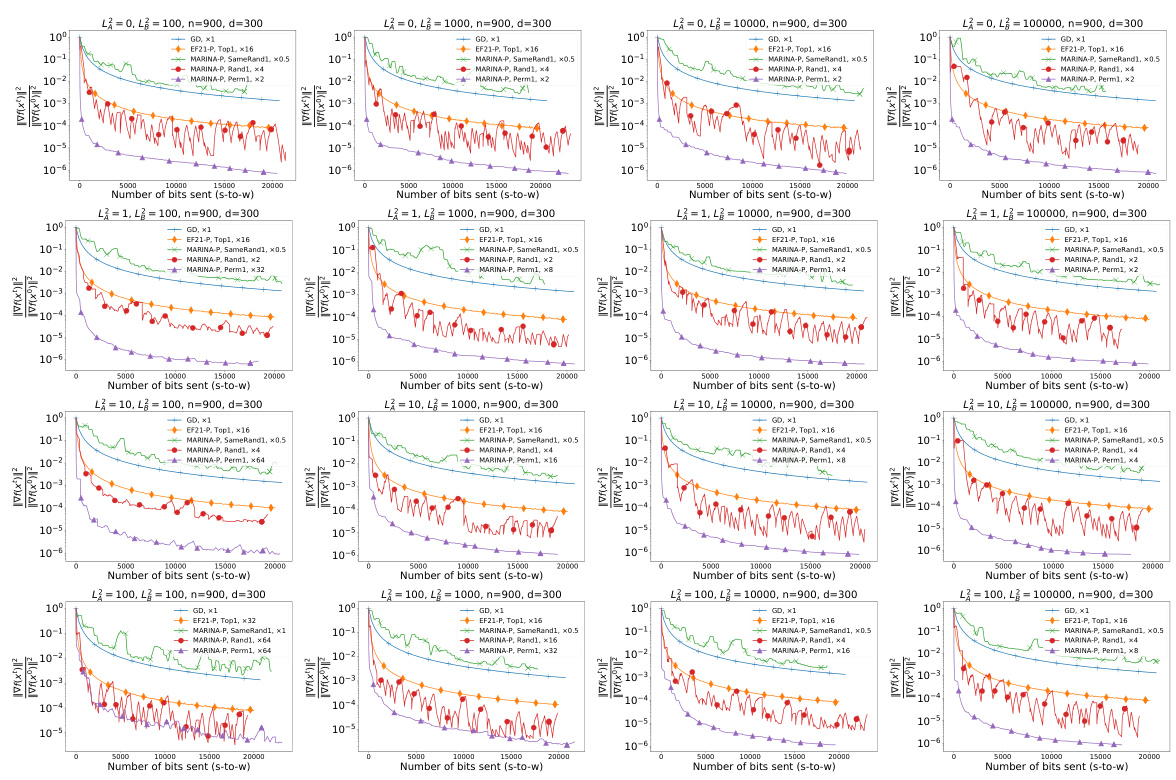

This figure displays the results of experiments on a quadratic optimization problem. Three different scenarios with varying numbers of workers (n=10, n=100, n=1000) are compared. The y-axis represents the squared norm of the gradient (||∇f(x)||²), a measure of the algorithm’s convergence. The x-axis shows the number of coordinates transmitted from the server to the workers, representing the communication cost. Multiple algorithms (GD, EF21-P, and various versions of MARINA-P) are plotted for comparison, illustrating the efficiency of the proposed MARINA-P in reducing communication complexity, especially as the number of workers increases.

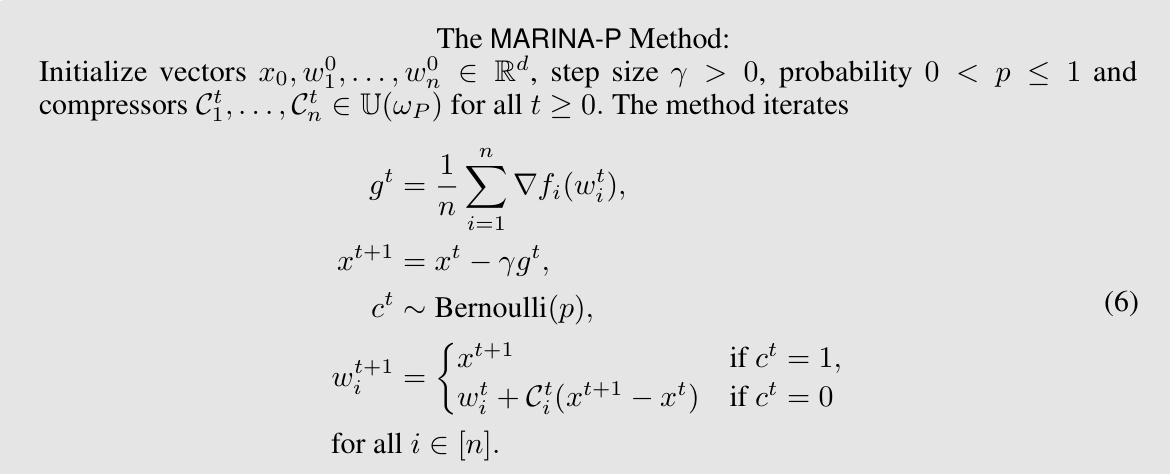

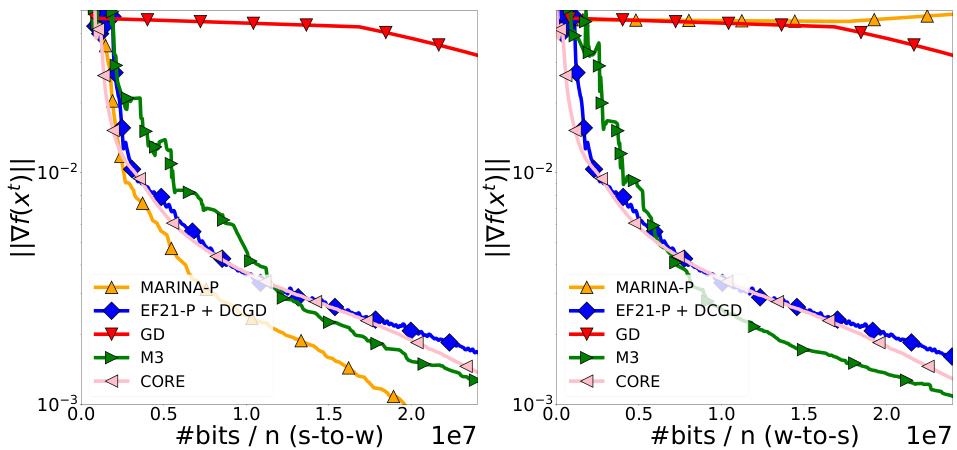

This table compares the worst-case communication complexities of different methods for finding an ɛ-stationary point in non-convex distributed optimization, specifically focusing on non-homogeneous quadratics. It contrasts the complexities of Gradient Descent (GD), other compressed methods (those using various compression techniques), CORE (a method proposed by Yue et al., 2023), MARINA-P (a new method with different compressor types), and M3 (a bidirectional compression method). The table separates server-to-worker (s2w) communication complexities from the total communication complexities (s2w + w2s). The results highlight that MARINA-P and M3 can achieve better complexities in certain regimes (specifically, when ’n’ (the number of workers) is large and the problem is close-to-homogeneous).

In-depth insights#

Worst-Case Complexity#

Analyzing worst-case complexity in distributed optimization is crucial for designing robust and reliable algorithms. A worst-case analysis provides guarantees on the algorithm’s performance under the most challenging conditions, offering insights into the fundamental limits of the optimization process. In the context of distributed systems, factors like communication bandwidth, worker heterogeneity, and data sparsity significantly impact performance. The worst-case analysis helps to identify the dominant factors affecting scalability and to understand the trade-offs between different algorithmic approaches. By considering various scenarios and potential bottlenecks, worst-case complexity analysis provides a rigorous foundation for algorithm development. The focus is less on average-case behavior and more on establishing performance bounds that hold regardless of input data characteristics. The study of worst-case complexity therefore highlights the limitations and strengths of different optimization methods for specific distributed settings and helps in comparing the efficacy of algorithms without relying on specific dataset properties.

MARINA-P Algorithm#

The MARINA-P algorithm is a novel method for downlink compression in distributed optimization, designed to improve upon existing methods’ limitations. Its core innovation lies in using a collection of correlated compressors, unlike previous methods which typically employed independent compressors. This allows MARINA-P to achieve a server-to-worker communication complexity that provably improves with the number of workers. The algorithm’s effectiveness hinges on a new assumption, the “Functional (LA, LB) Inequality,” which quantifies the similarity between functions distributed across the workers. When this similarity is high (LA is small), MARINA-P significantly outperforms previous methods. The theoretical analysis is backed by empirical experiments showing strong agreement between theory and practice. However, limitations exist in scenarios where the functional similarity assumption is violated. Furthermore, the algorithm primarily focuses on downlink compression, potentially neglecting significant uplink communication costs in practical settings.

Bidirectional Compression#

Bidirectional compression in distributed optimization tackles the challenge of minimizing communication overhead by compressing both uplink (worker-to-server) and downlink (server-to-worker) information. This approach is crucial in large-scale machine learning where bandwidth limitations significantly impact training efficiency. While many methods focus solely on uplink compression, bidirectional strategies are essential for addressing the communication bottleneck comprehensively. The design of effective bidirectional compressors requires careful consideration of both compression ratios and the impact on algorithm convergence. Achieving provable improvements in total communication complexity is a key goal and requires novel techniques to overcome inherent limitations in compression. The trade-off between compression strength and convergence speed must be carefully balanced. Furthermore, the development of theoretical guarantees for bidirectional methods presents a significant challenge, requiring advanced analysis. Methods often employ advanced compression techniques such as permutation compressors which leverage correlations to improve efficiency. Finally, practical considerations related to implementation and computational overhead are important aspects to evaluate the effectiveness of any bidirectional compression approach.

Functional Inequality#

The concept of “Functional Inequality” in the context of distributed optimization, as introduced in the research paper, is a crucial assumption that bridges the gap between theoretical lower bounds and practically achievable convergence rates. It essentially quantifies the similarity or dissimilarity among the individual functions distributed across worker nodes. The inequality’s structure reveals a trade-off between two constants: LA, representing function similarity (smaller values indicate greater similarity), and LB, accounting for dissimilarity. This framework is significant because it allows the development of novel algorithms, like MARINA-P, that can demonstrably improve upon existing methods’ communication complexities, especially when the functions exhibit high similarity (LA is small). By introducing this assumption, the paper provides a formal justification for algorithms that show improved performance with an increased number of workers. The assumption’s relative weakness is also explored, demonstrating its applicability in common scenarios. This leads to improved theoretical results, which are validated by experiments. Overall, the Functional Inequality serves as a powerful tool in the quest for efficient distributed optimization, highlighting the importance of function structure in shaping the efficiency of distributed learning.

Empirical Validation#

An Empirical Validation section in a research paper would rigorously test the proposed methods. It would involve designing experiments to assess performance across various metrics, comparing against state-of-the-art baselines. Real-world datasets would be ideal to showcase practical applicability. The experiments should be well-designed with proper controls to eliminate confounding factors. Statistical significance tests are crucial to determine whether observed differences are genuine. The results must be presented transparently, including visualizations and error bars, to facilitate reproducibility and allow readers to judge the claims’ validity. Detailed descriptions of experimental setups, including parameter choices and hardware specifics, are needed for reproducibility. The discussion section following the results would critically analyze the findings, highlighting both strengths and limitations. A strong empirical validation builds confidence in the proposed method’s practical value. The results section should also address the effect of hyperparameter tuning. The choice of baselines and metrics must be justified to ensure the comparison is fair and relevant.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows the results of experiments on a quadratic optimization problem. The y-axis represents the squared norm of the gradient (||∇f(x)||²), a measure of how far the current solution is from a stationary point. The x-axis shows the number of bits per worker sent from the server to the workers (bits/n (s-to-w)). Different lines represent different algorithms: GD (Gradient Descent), EF21-P (a previous compressed gradient method), and MARINA-P (the proposed method) with various compression techniques (SameRandK, RandK, and PermK). The three subplots (n=10, n=100, n=1000) show how the performance of the algorithms change with the number of workers (n). The figure demonstrates that MARINA-P, especially with PermK compressors, achieves faster convergence using significantly fewer bits per worker, particularly as the number of workers increases.

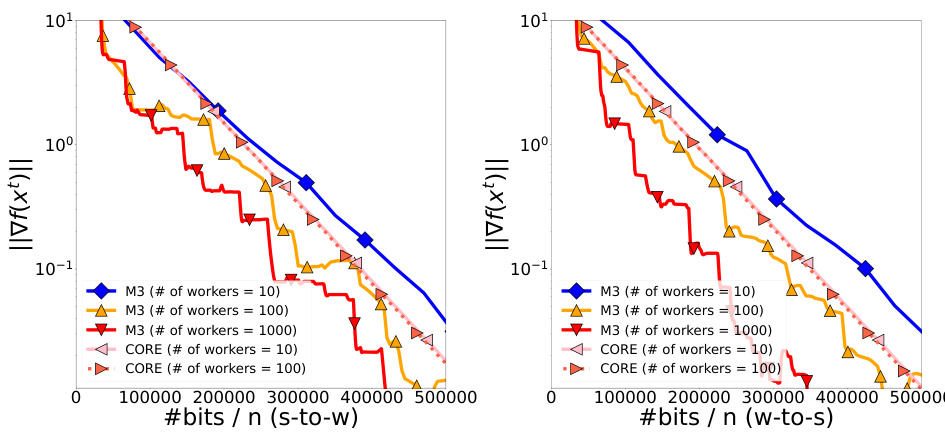

The figure shows the convergence performance of the M3 and CORE algorithms on a quadratic optimization problem. Two plots are presented: one showing the norm of the gradient against the number of bits transmitted from the server to the workers, and another showing the same metric against bits transmitted from workers to the server. Different curves represent different numbers of workers (10, 100, and 1000) for each algorithm. The plots illustrate the communication complexity of each method. M3 shows consistently better convergence than CORE, and demonstrates that the efficiency of M3 improves with increasing number of workers.

This figure presents experimental results on a quadratic optimization problem. It compares the convergence rate of several distributed optimization algorithms (GD, MARINA-P with various compressors (SameRand, Rand, Perm), and EF21-P) in terms of the norm of the gradient against the number of bits communicated from the server to the workers (bits/n s-to-w). The results are shown for different numbers of workers (n=10, 100, 1000) to illustrate how communication complexity scales with the number of workers. The x-axis represents the communication cost in bits per worker, while the y-axis shows the norm of the gradient at each iteration. This allows for evaluating the convergence speed of each algorithm under different communication constraints.

This figure displays the results of experiments on a quadratic optimization problem. Three different worker counts (n = 10, 100, 1000) are used, with various compression techniques compared against gradient descent (GD). The y-axis represents the norm of the gradient, indicating the convergence speed. The x-axis shows the number of coordinates sent from the server to the workers, which directly relates to communication complexity. The goal is to illustrate how different methods achieve faster convergence with reduced communication.

This figure shows the results of experiments on a quadratic optimization problem. The y-axis represents the norm of the gradient, which measures how close the algorithm is to a solution. The x-axis represents the number of coordinates sent from the server to the workers, indicating the communication cost. Multiple lines are presented, each representing a different algorithm (GD, EF21-P, and MARINA-P with various compression strategies). This allows for a comparison of the convergence speed and communication efficiency of each algorithm.

The figure shows the results of experiments on a quadratic optimization problem. Different algorithms (GD, EF21-P, MARINA-P with various compressors) are compared based on the norm of the gradient against the number of bits sent from the server to the workers. The experiments are conducted with 10 workers, varying the smoothness parameter (L) and heterogeneity parameter (L²) across different experimental settings. The goal is to show the impact of different parameters and algorithms on the optimization process, particularly highlighting the performance of MARINA-P with PermK compressors.

This figure presents the results of experiments on a quadratic optimization problem. It compares the convergence speed (measured by the norm of the gradient) of several distributed optimization algorithms against the number of bits communicated from the server to the workers. The algorithms include gradient descent (GD), EF21-P with different TopK compressors (Top1, Top3, Top30), and MARINA-P with various compressor types (Rand1, Rand3, Rand30, Perm3, Perm30, SameRand1, SameRand3, SameRand30). Different numbers of workers (n=10, n=100, n=1000) are tested to demonstrate how scaling impacts the communication complexity.

Full paper#