↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel approach to humanoid locomotion, using a transformer model trained on diverse sensorimotor data. This opens avenues for zero-shot generalization to new environments and data-efficient learning in robotics, addressing key challenges in the field. Its generative modeling framework has broader implications for other complex control tasks.

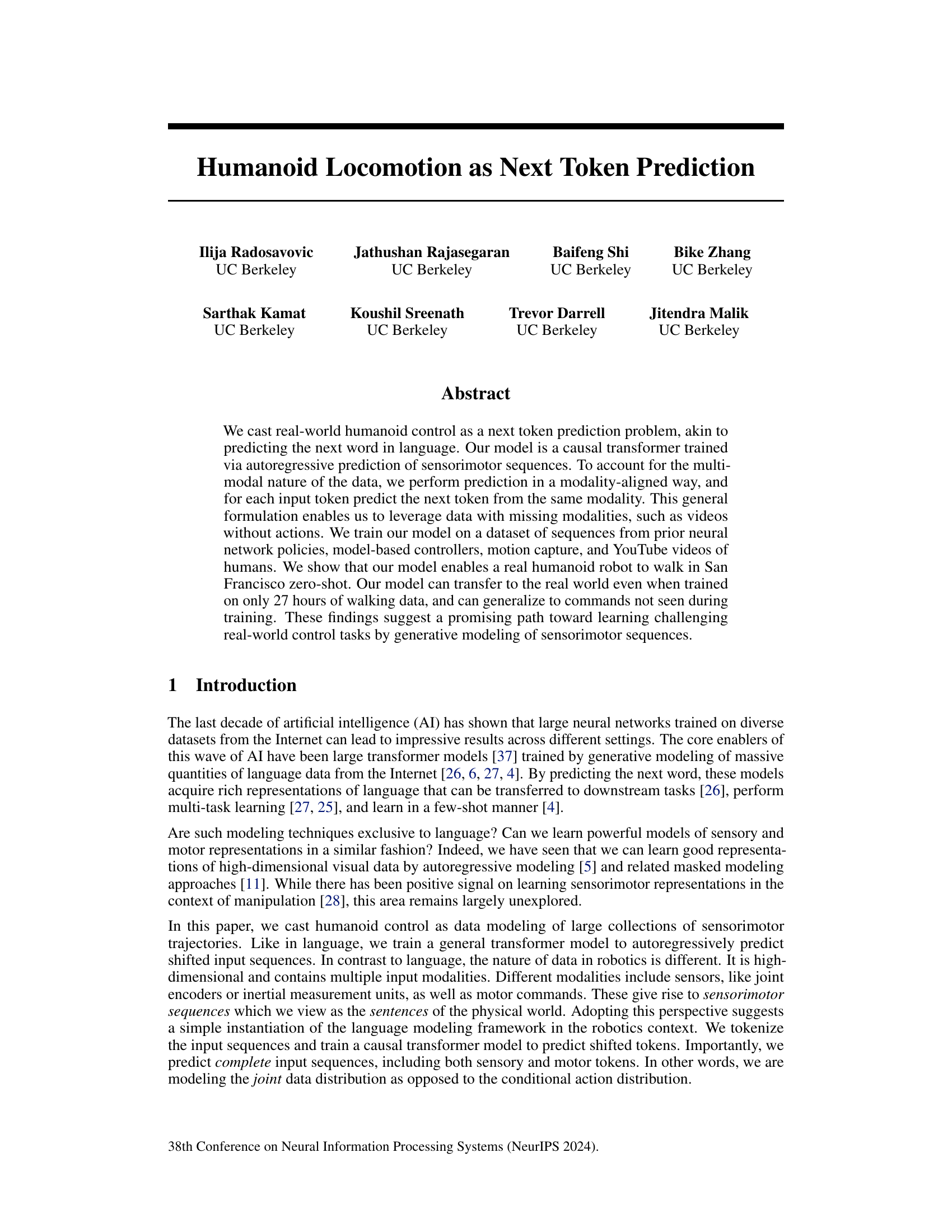

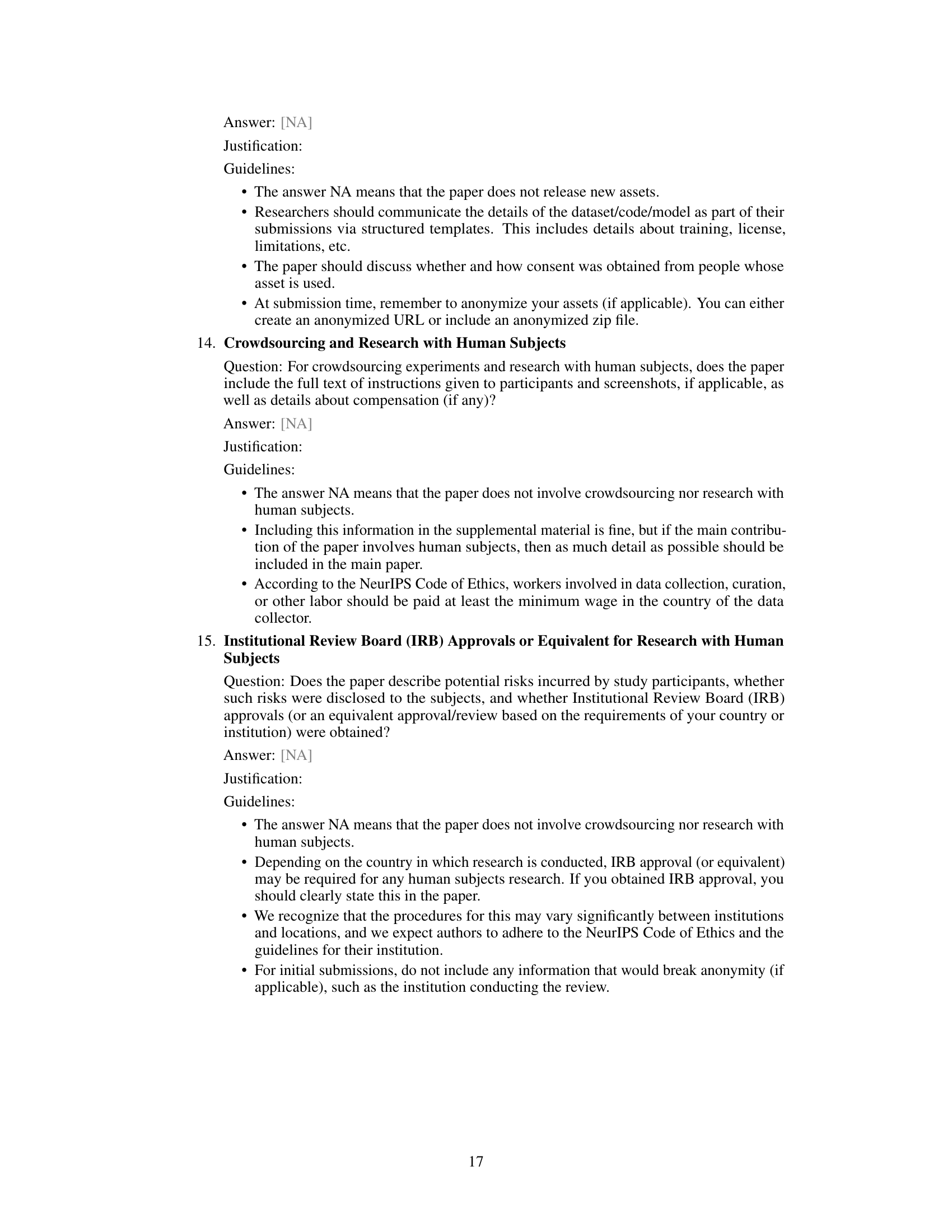

Visual Insights#

This figure shows a teal-colored humanoid robot walking in various outdoor locations throughout San Francisco. The photos illustrate the robot’s ability to navigate different terrains and environments, showcasing its zero-shot deployment in a real-world, complex urban setting. The full video can be found on the project’s webpage.

In-depth insights#

Next Token Prediction#

The concept of “Next Token Prediction” offers a novel framework for approaching humanoid locomotion control. By framing the problem as predicting the next element (token) in a sequence of sensorimotor data, the approach cleverly leverages the power of transformer models. This is a significant departure from traditional methods, moving away from explicit control designs and instead learning from large datasets of various modalities, including robot sensor data, motion capture, and even YouTube videos of humans. This data diversity is crucial for robustness and generalizability. The modality-aligned prediction is particularly ingenious, allowing the model to handle missing data points and learn from incomplete sensorimotor sequences. This ability to learn from various sources allows for efficient data utilization and a powerful zero-shot transfer to real-world scenarios. The generative modeling aspect is key, as it allows learning of the joint sensorimotor distribution, moving beyond simply conditioning actions on observations. Ultimately, this paradigm shift towards prediction demonstrates a promising path towards building more robust and adaptable humanoid robots.

Multimodal Learning#

Multimodal learning, in the context of a research paper on humanoid locomotion, would explore how to effectively combine different data sources such as visual, proprioceptive, and motor control signals to improve robot control and learning. A key aspect would be how to represent and fuse these diverse modalities, potentially using transformer-based architectures to learn rich, integrated representations of sensorimotor data. The effectiveness would be evaluated through metrics like zero-shot generalization to new environments and improved robustness. Challenges in multimodal learning, such as handling missing modalities (e.g., videos without corresponding motor commands), and managing the high dimensionality of multimodal data, would also be discussed. The discussion would highlight the potential advantages of a multimodal approach over unimodal methods, showing how combining diverse sensory information leads to more robust and adaptable humanoid locomotion. Finally, the impact of different data sources (simulated vs. real-world), and the scalability of the proposed approach to larger datasets would be analyzed.

Zero-Shot Transfer#

Zero-shot transfer, in the context of robotics, signifies a model’s capacity to generalize to unseen environments or tasks without any explicit retraining or fine-tuning on those specific scenarios. This capability is particularly valuable because it significantly reduces the time and resources traditionally needed to adapt robots to new situations. The success of a zero-shot transfer largely depends on the richness and diversity of the training data, ensuring the model learns generalizable representations rather than just memorizing specific instances. A model achieving robust zero-shot transfer often leverages a strong underlying representation learning mechanism that captures underlying principles of locomotion and control, thus enabling generalization to novel contexts. This approach is crucial for creating more adaptable and robust robots that can effectively function in dynamic and complex real-world environments. The key challenge remains balancing generalizability with avoiding overgeneralization, ensuring that the model maintains sufficient performance across various scenarios while also avoiding catastrophic failures in unexpected situations. Effective zero-shot transfer, therefore, requires not just sophisticated algorithms but also meticulous data curation and model design that prioritize learning robust and generalizable representations of sensorimotor dynamics.

Data Efficiency#

The concept of data efficiency is central to evaluating the success of machine learning models, especially in resource-constrained domains like robotics. This paper tackles the challenge by demonstrating that a generative modeling approach, using a transformer network to predict sensorimotor sequences, significantly improves data efficiency compared to traditional reinforcement learning methods. The model’s ability to learn from incomplete data (e.g., videos without motor commands) is a crucial aspect of its efficiency, allowing it to leverage diverse and readily available data sources. The model’s performance scales favorably with dataset size, context length, and model capacity, indicating the potential to further enhance data efficiency by increasing the volume and richness of the training data. Zero-shot generalization to unseen environments and commands highlights the robustness and adaptability of this learned representation, further contributing to its overall data efficiency. The findings strongly suggest that generative modeling presents a promising pathway for developing data-efficient control strategies in robotics and other complex real-world applications.

Real-world Locomotion#

The successful transition of humanoid locomotion from simulation to real-world environments is a significant achievement. The paper highlights the zero-shot generalization capabilities of the model, enabling the robot to navigate diverse terrains like walkways, asphalt, and even uneven city streets in San Francisco. This demonstrates the robustness and adaptability of the learned control policy. A key aspect is the generative modeling approach. Instead of solely relying on reinforcement learning, the model is trained to predict sensorimotor sequences, incorporating data from multiple sources and handling missing modalities. This data-driven approach allows for a more generalized and robust solution compared to traditional methods that often struggle with real-world complexities and noisy data. The ability to train with incomplete data such as human videos, further improves the model’s generalization capacity. However, challenges remain. While impressive, the performance is not without limitations. Future work should focus on addressing robustness issues to handle unexpected events or terrain variations in real-world settings.

More visual insights#

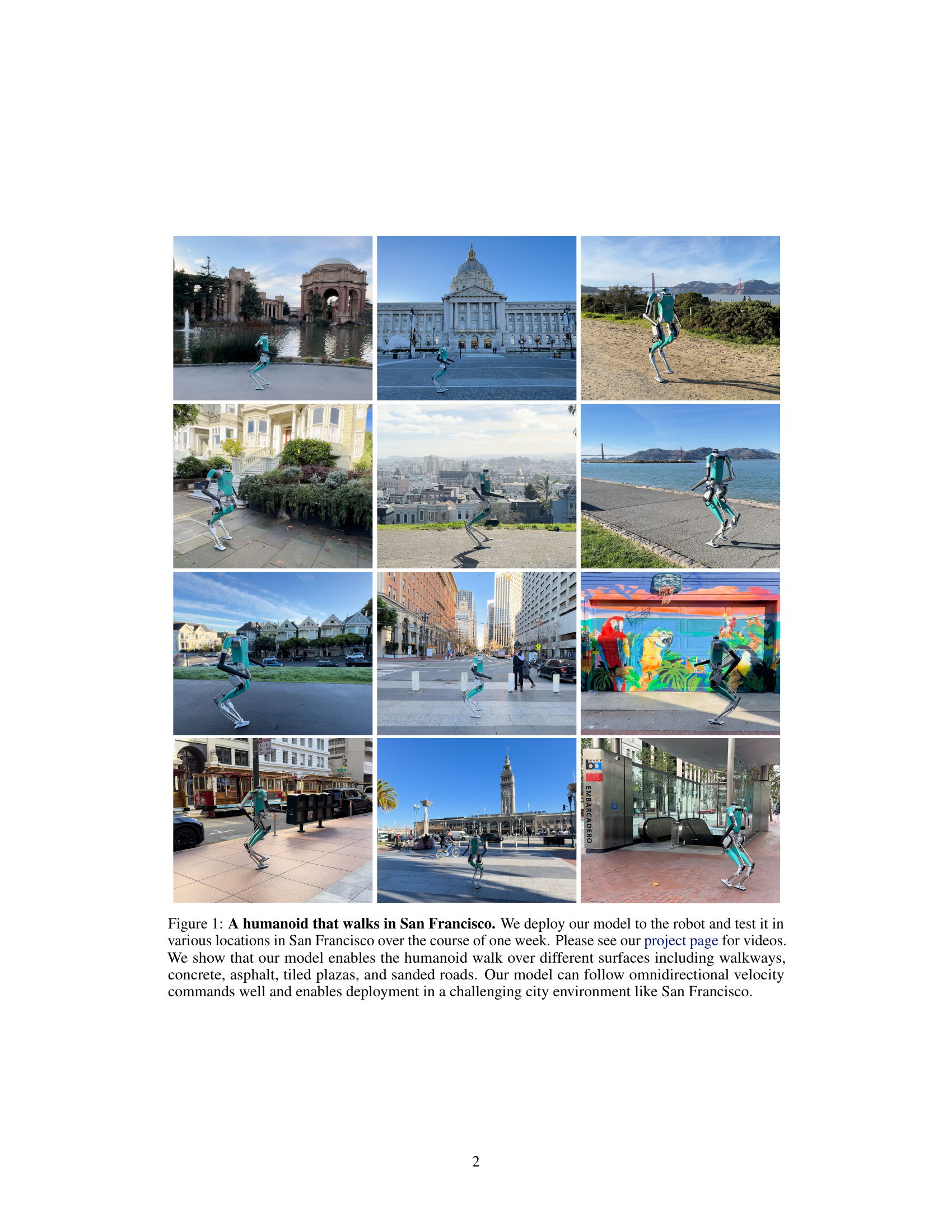

More on figures

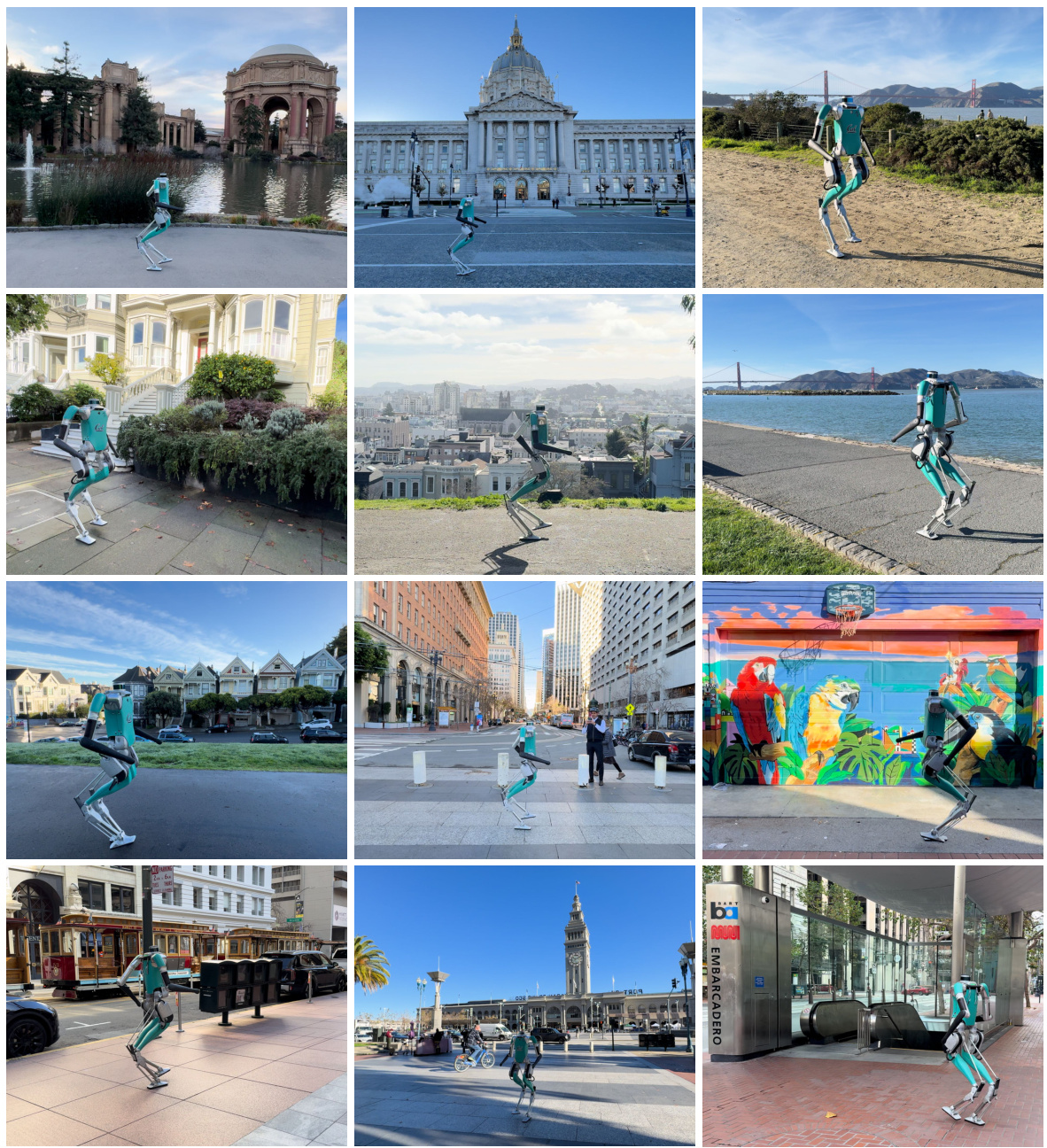

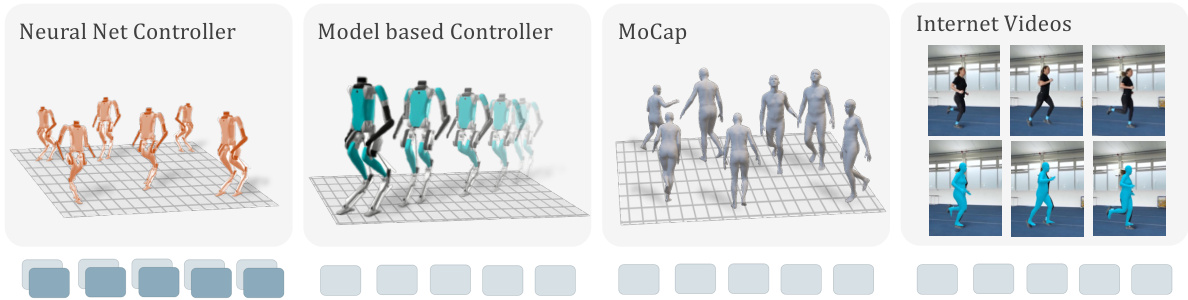

This figure illustrates the overall process of the proposed method in the paper. It starts by showing the various data sources used for training: neural network policies, model-based controllers, motion capture data, and videos from YouTube. All of this data is fed into a transformer model for training via autoregressive prediction. The trained model is then deployed on a real humanoid robot to perform zero-shot locomotion in various locations in San Francisco.

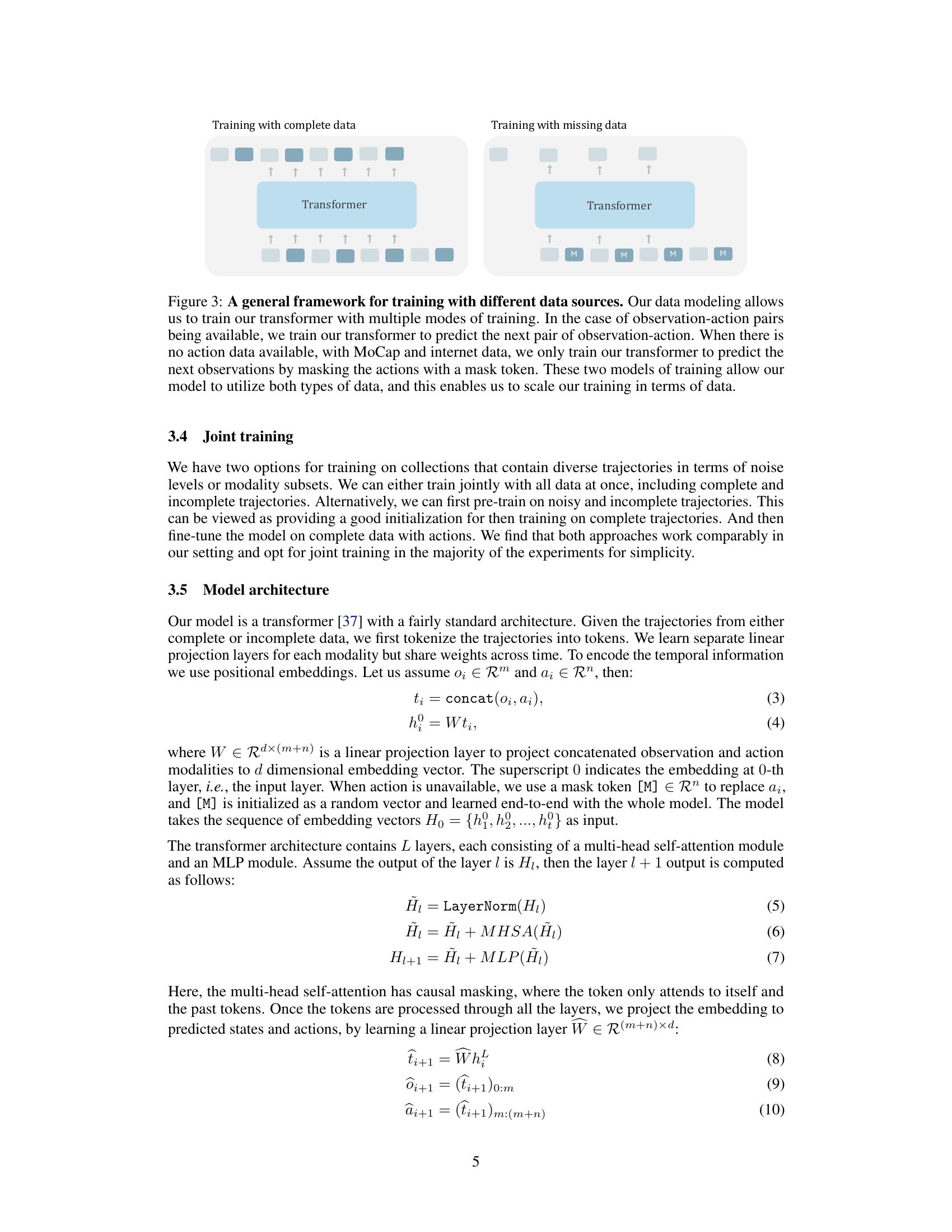

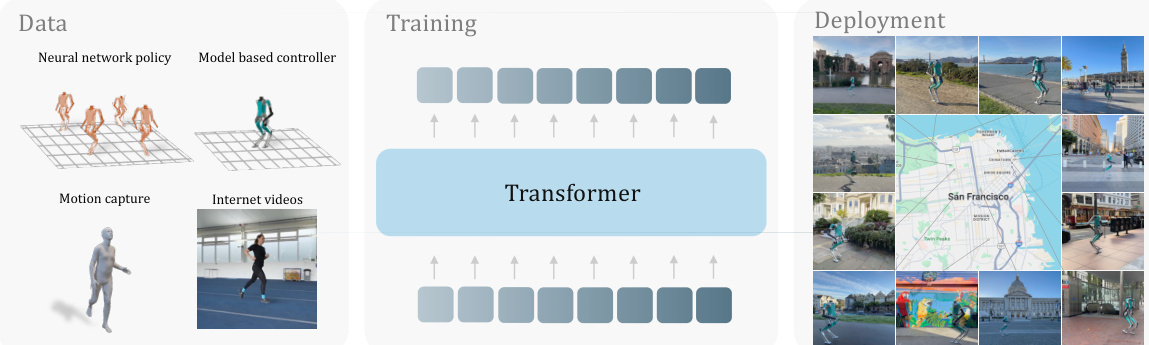

This figure illustrates the two training scenarios of the transformer model. The left side shows training with complete data (observation-action pairs), while the right side demonstrates training with missing data (only observations from MoCap and internet videos, actions are masked). The model’s ability to handle both types of data is highlighted, emphasizing its scalability.

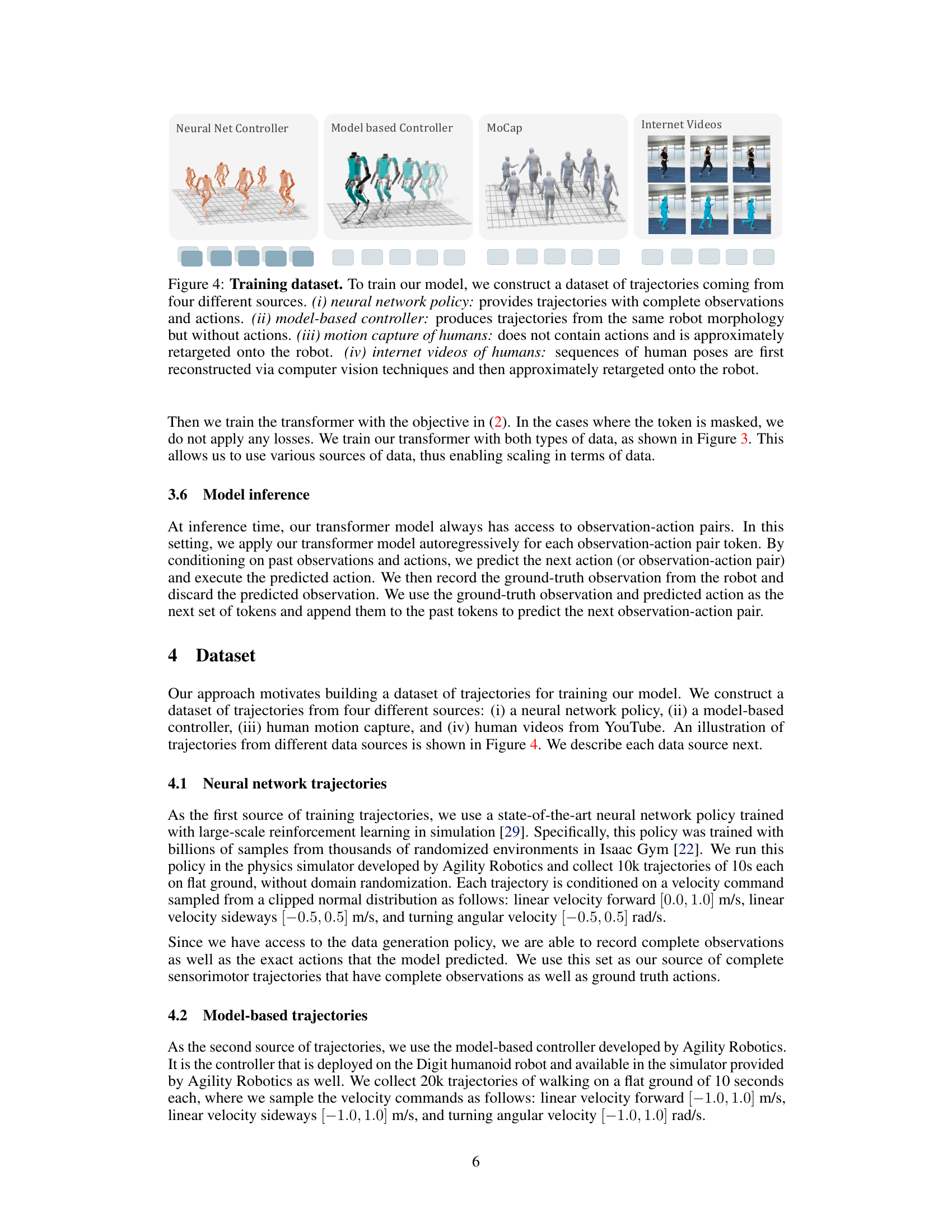

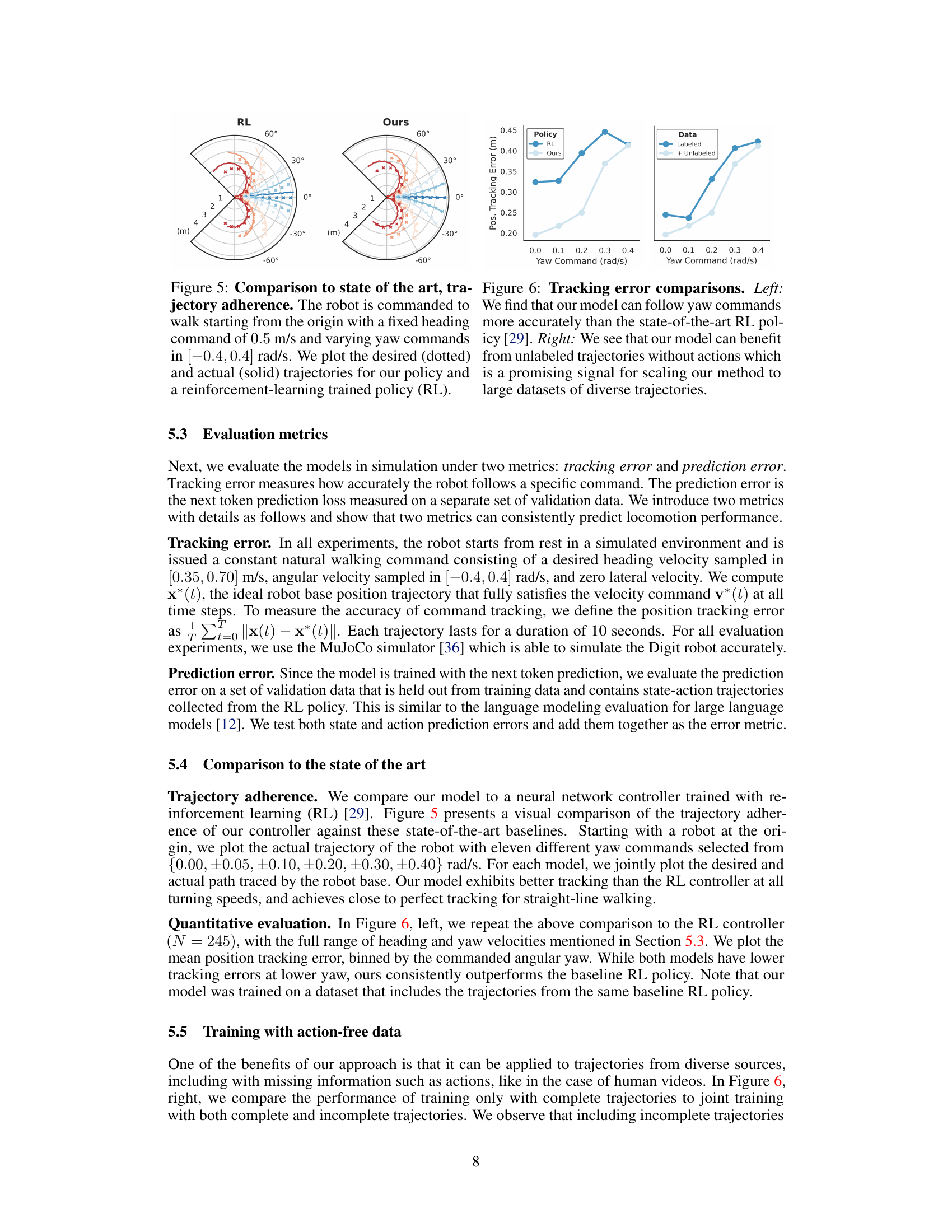

This figure shows the four data sources used to train the humanoid locomotion model. The neural network policy provides complete trajectories with observations and actions. The model-based controller offers trajectories with observations only. Motion capture data includes human movement retargeted to the robot, again without actions, and finally, internet videos of humans provide data processed through computer vision to extract pose information, then retargeted to the robot, also lacking action data.

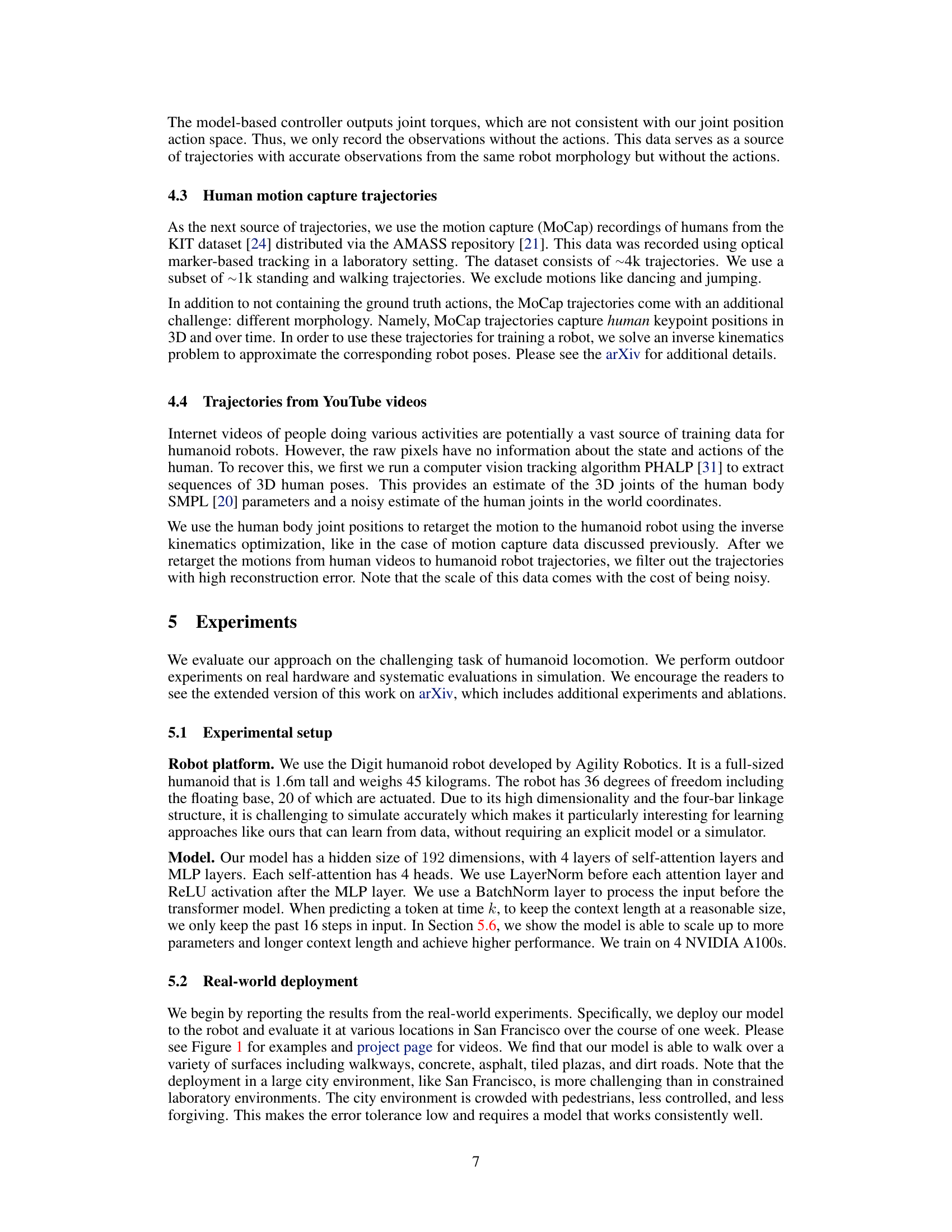

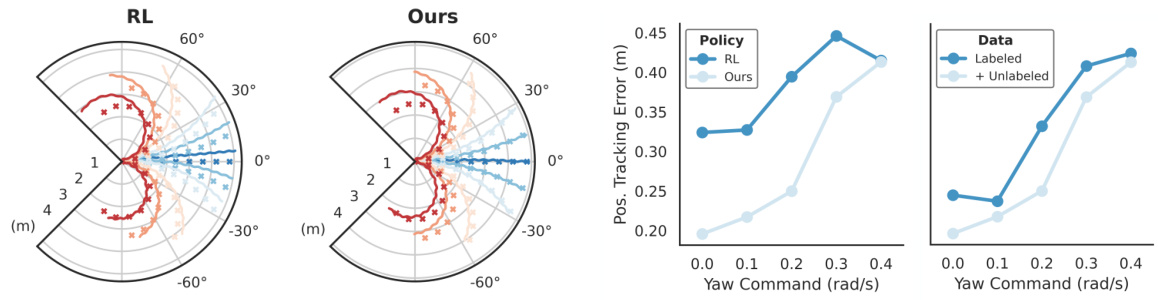

This figure compares the trajectory adherence of the proposed method to a reinforcement learning baseline. The robot is given a forward walking command with varying yaw commands. The plots show the desired trajectory (dotted lines) and the actual trajectories (solid lines) for both the proposed method and the reinforcement learning baseline. The plot demonstrates that the proposed method follows the desired trajectories more accurately than the reinforcement learning baseline.

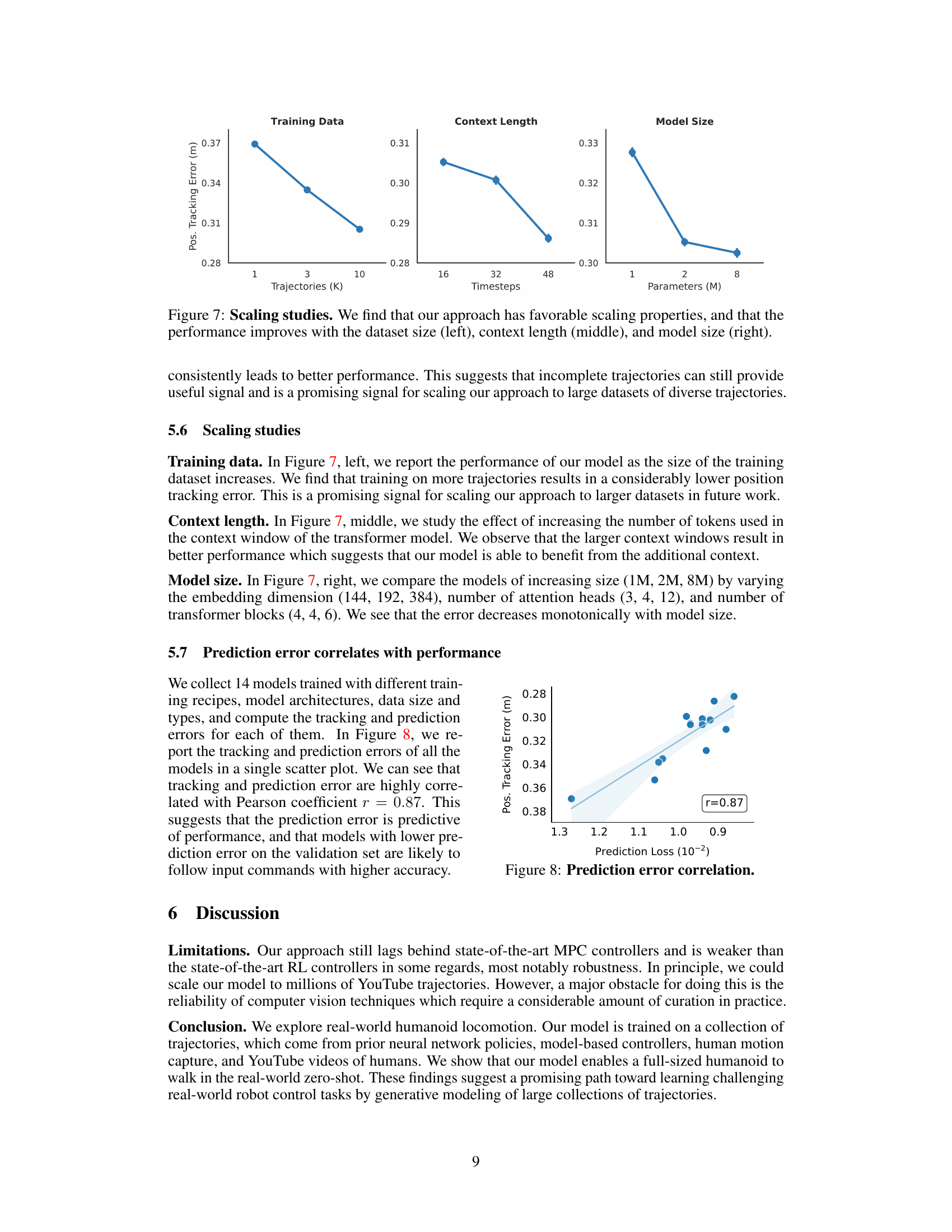

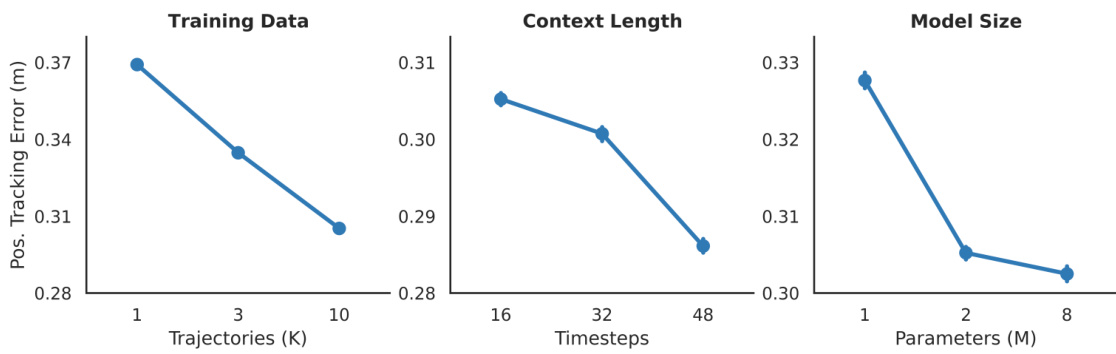

This figure shows the results of scaling studies performed on the model. Three subplots illustrate how performance (measured by position tracking error) changes with increases in (left) training dataset size (number of trajectories), (middle) context length (number of timesteps considered by the model), and (right) model size (number of parameters). In all cases, performance improves with increased scale, indicating favorable scaling properties.

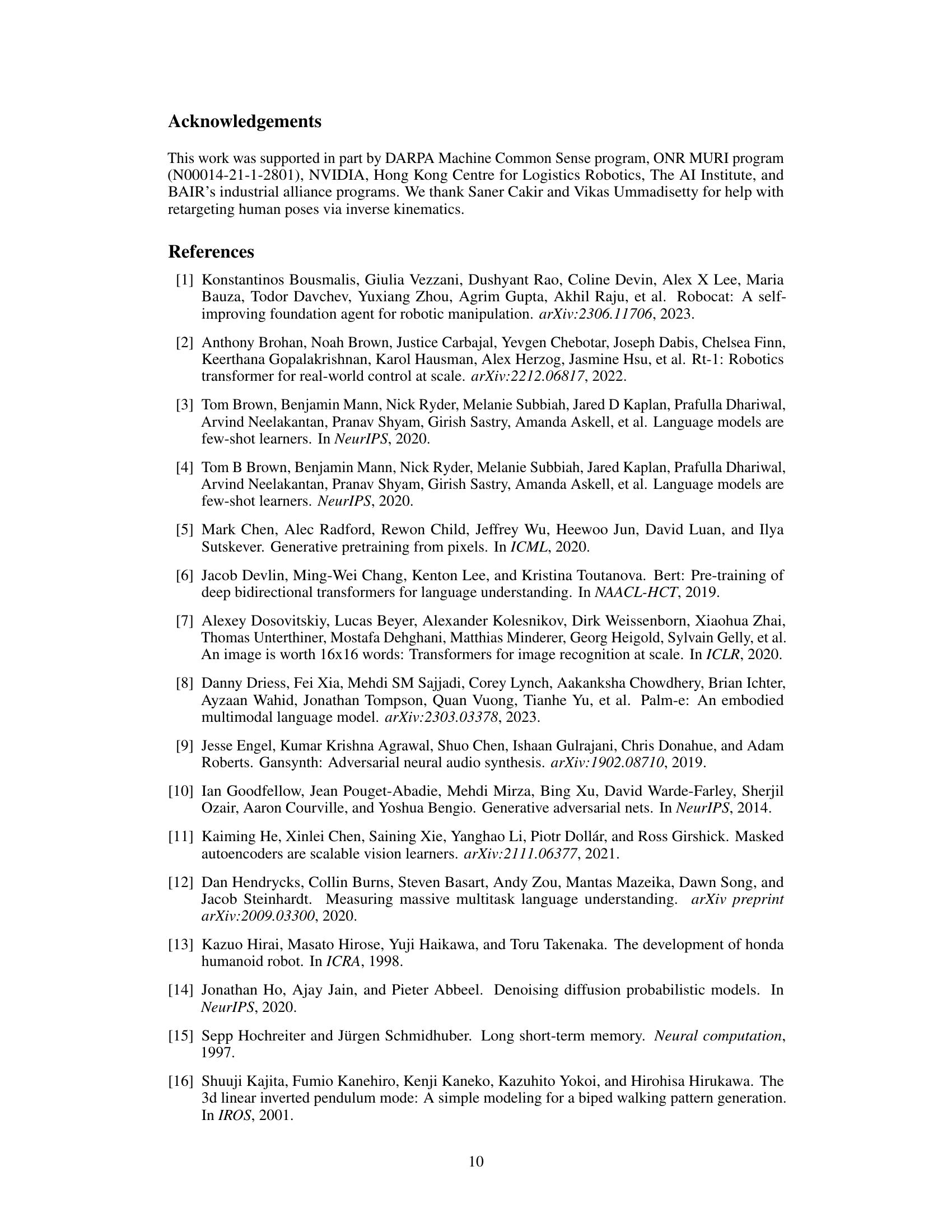

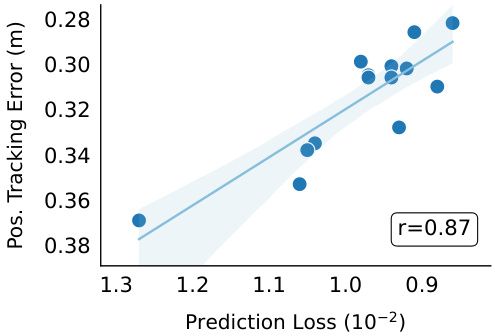

This figure shows the correlation between prediction error and position tracking error in the simulation experiments. The scatter plot displays the position tracking error (y-axis) against the prediction loss (x-axis) for fourteen different models trained with varied training methods, architectures, and data sizes. The strong positive correlation (r=0.87) indicates that models with lower prediction errors generally exhibit better position tracking accuracy.

Full paper#