↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Point cloud self-supervised learning often uses masked autoencoders, but existing methods feed the masked patch centers directly to the decoder, hindering effective semantic representation learning. This paper highlights a key observation: the decoder can reconstruct point clouds well even without encoder information if it has the masked patch centers. This raises concerns about the encoder’s role in learning semantic features.

To address this, PCP-MAE is proposed. This method uses a ‘Predicting Center Module’ (PCM) which shares parameters with the original encoder, and it learns to predict the significant centers. These predicted centers then replace the directly provided ones for masked patches in the decoder, enhancing reconstruction accuracy. Importantly, the PCM uses cross-attention, allowing it to leverage both visible and masked patch information for center prediction. Experimental results show that PCP-MAE significantly surpasses existing methods, achieving significant performance improvements on benchmark datasets. This indicates that the proposed method effectively guides the model to learn more meaningful representations, ultimately improving downstream task accuracy.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses the limitations of existing masked autoencoders for point cloud data by proposing a novel method to learn more effective semantic representations. This is vital for improving the accuracy and efficiency of downstream tasks like 3D object classification and scene segmentation, pushing the boundaries of self-supervised learning in 3D computer vision. The insights regarding center prediction and its impact on model training open new avenues for research and development in self-supervised learning methodologies.

Visual Insights#

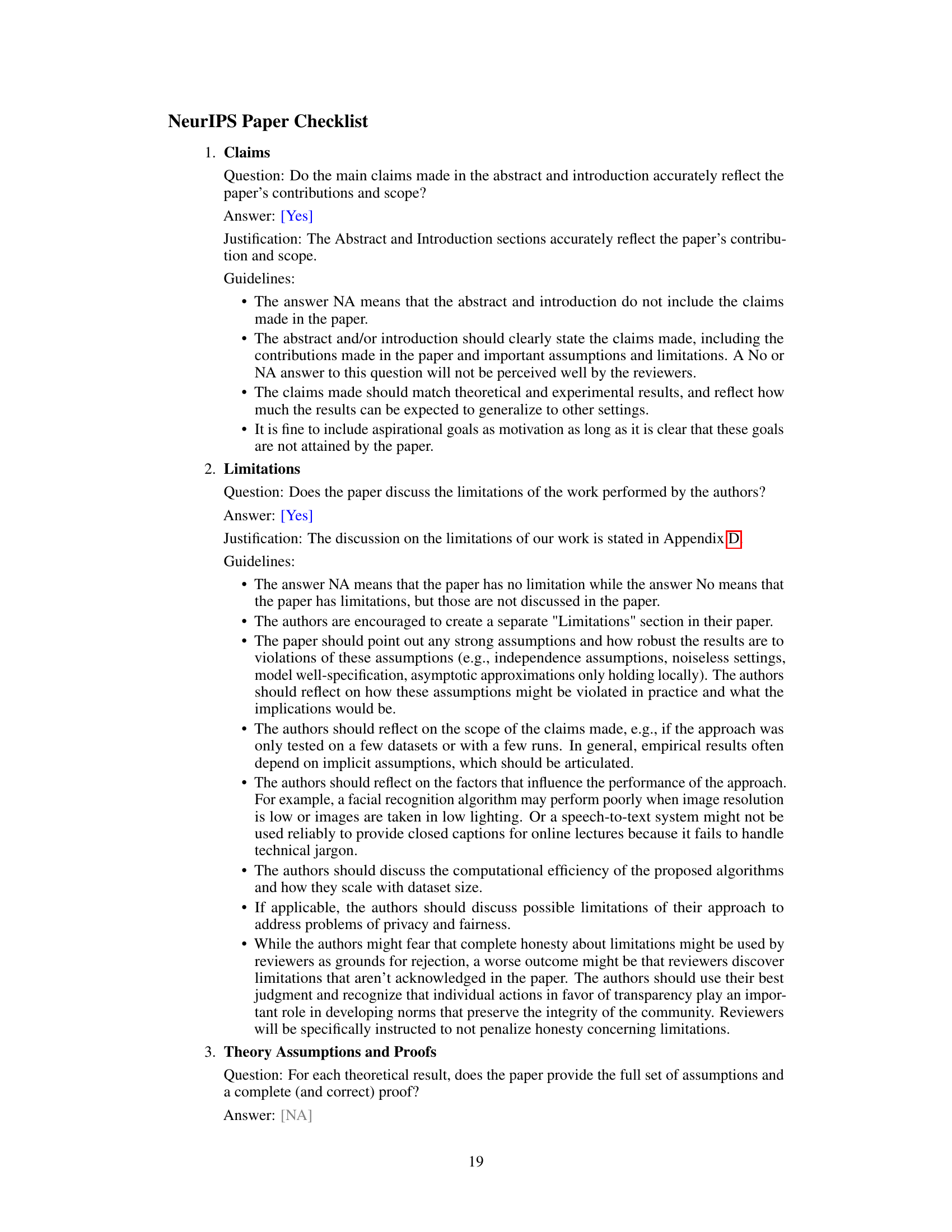

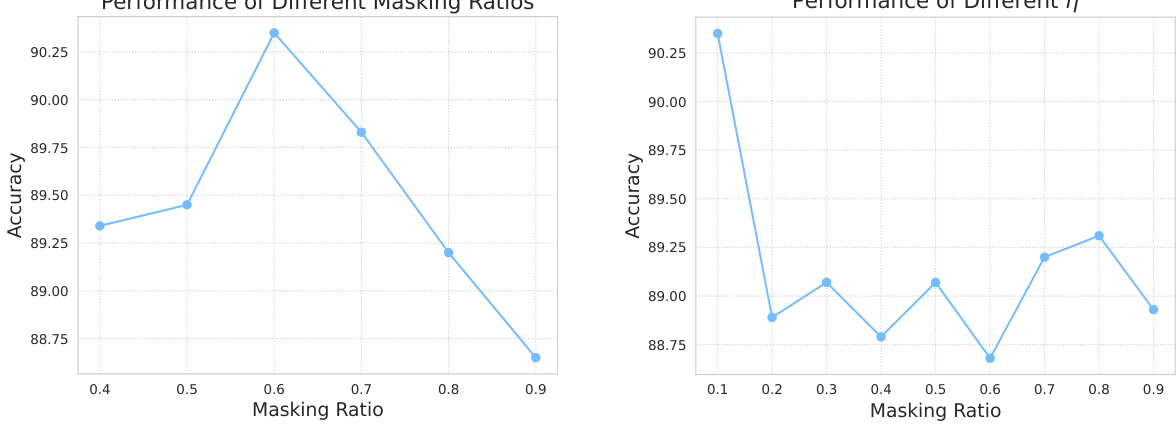

This figure empirically demonstrates a key difference between 2D and 3D masked autoencoders. In 2D (image) MAEs, if 100% of the image patches are masked, and only the positional embeddings (indices) are provided to the decoder, reconstruction is impossible. However, in 3D (point cloud) MAEs, even with 100% masking, and only using the positional embeddings (coordinates of patch centers), the decoder can still reconstruct the point cloud relatively well. This indicates that patch centers in point clouds contain rich information that the 2D indices in images do not.

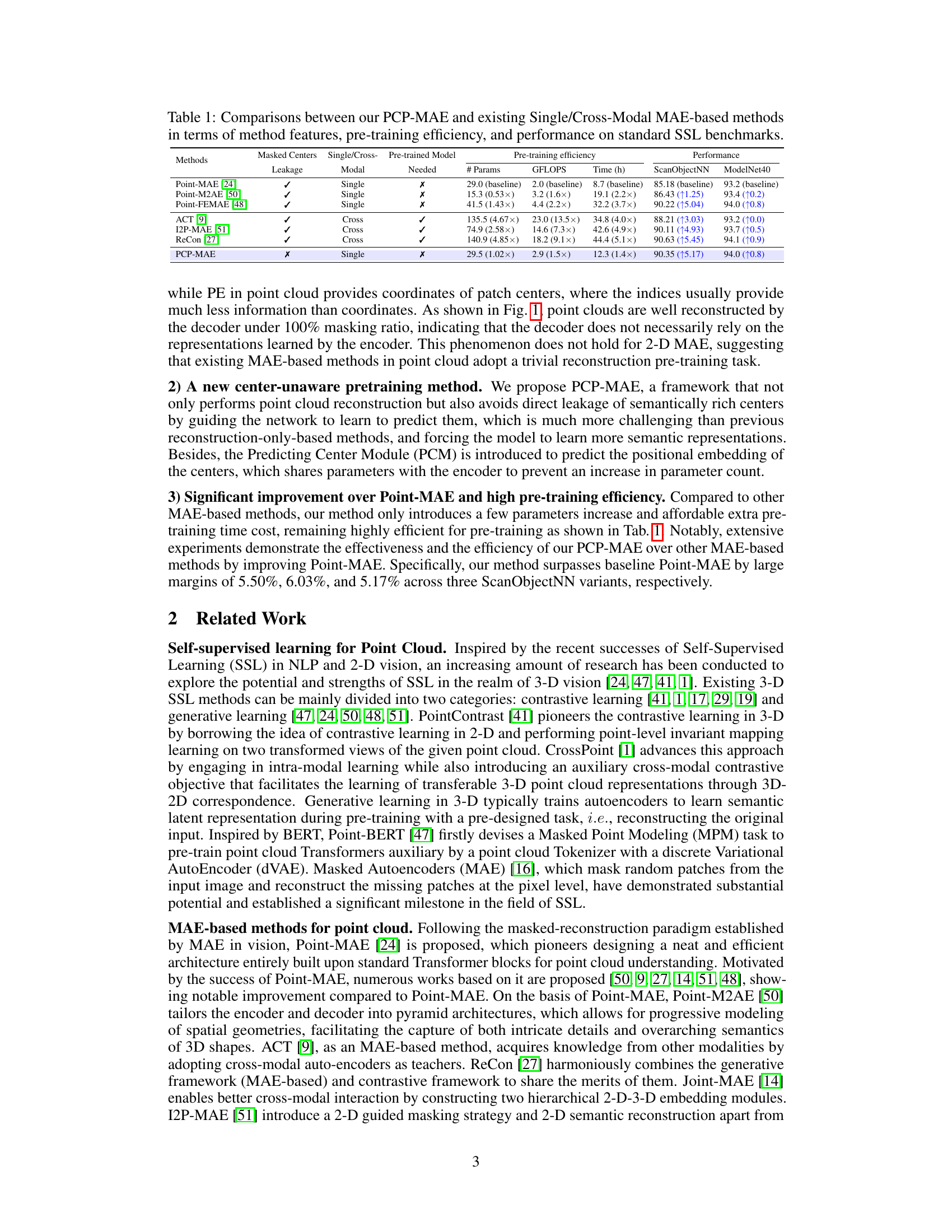

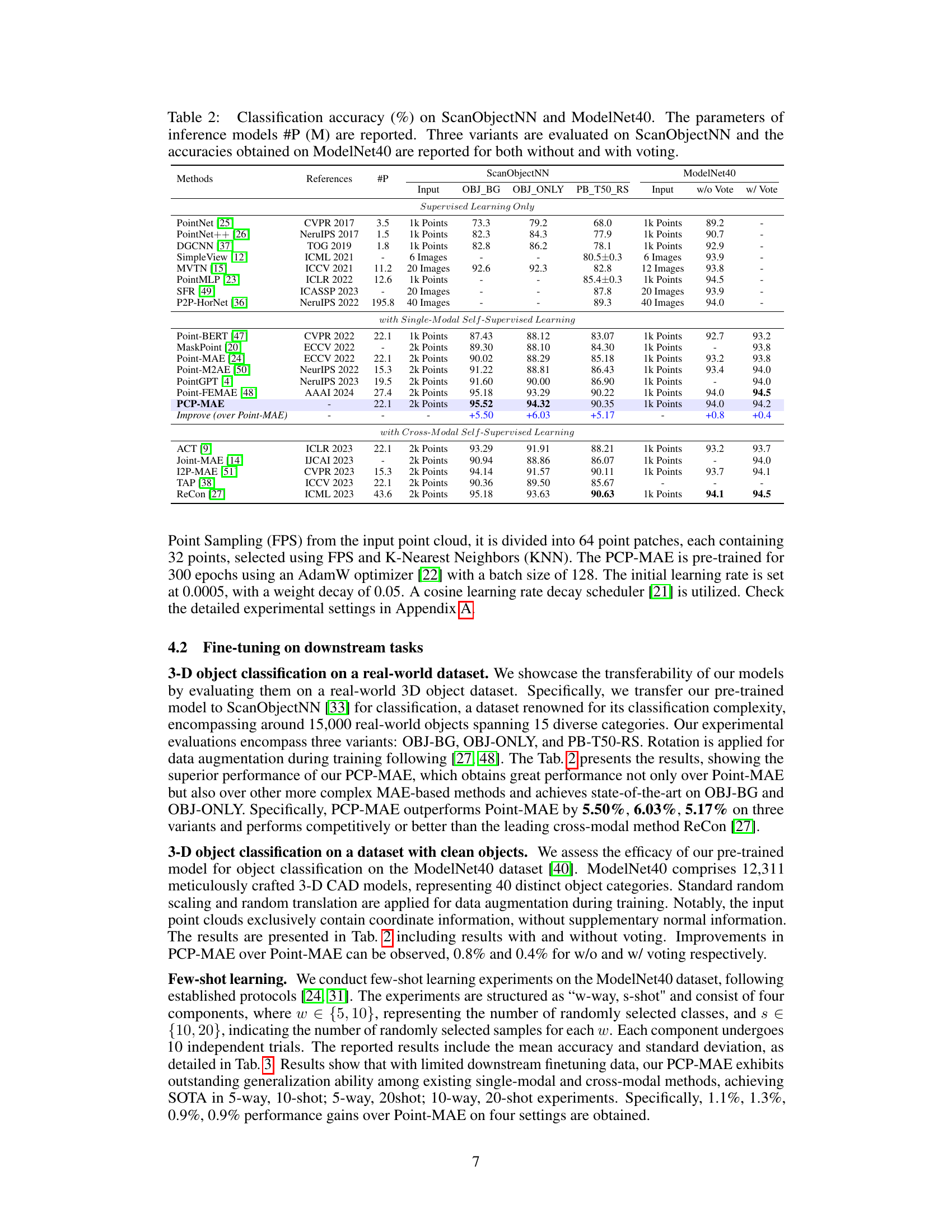

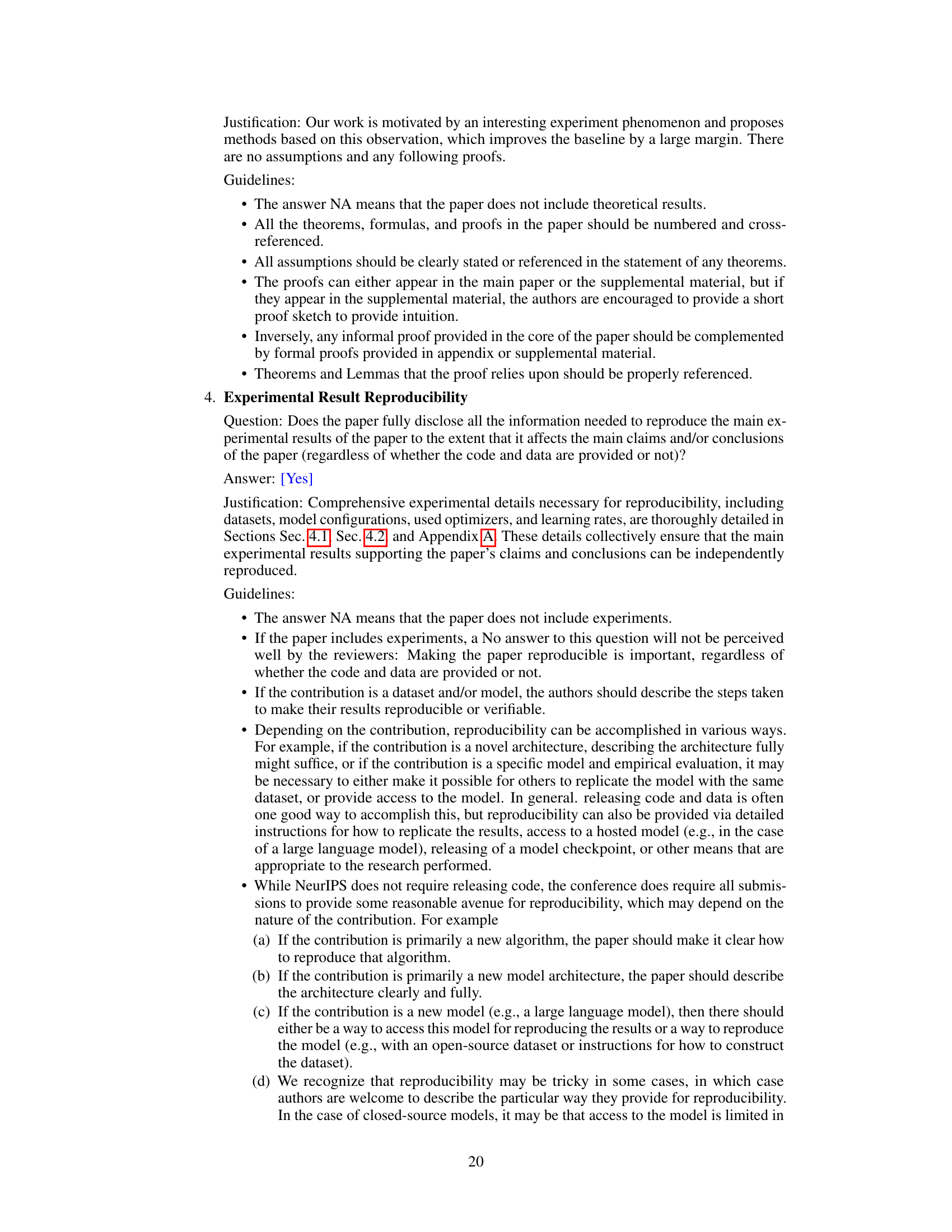

This table compares PCP-MAE with other single and cross-modal masked autoencoder methods for point cloud self-supervised learning. It provides a quantitative comparison across several key aspects: whether masked centers are leaked to the decoder, the type of model (single or cross-modal), whether a pre-trained model was used, the number of parameters, GFLOPS (a measure of computational cost), pre-training time, and finally the performance on the ScanObjectNN and ModelNet40 benchmarks. This allows for a comprehensive evaluation of PCP-MAE’s efficiency and effectiveness relative to existing state-of-the-art approaches.

In-depth insights#

Center Prediction#

The concept of ‘Center Prediction’ in the context of point cloud processing is crucial for enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of masked autoencoders (MAEs). Directly feeding masked patch centers to the decoder, as done in some previous MAE approaches, hinders the encoder’s ability to learn robust semantic representations. The core idea behind center prediction is to make the encoder learn to predict these crucial centers rather than relying on their direct provision. This forces the encoder to develop stronger feature extractions, resulting in more meaningful latent representations. A dedicated module, often incorporating cross-attention mechanisms, is employed to predict these centers, typically sharing weights with the encoder to improve efficiency and promote parameter sharing. The success of this approach is demonstrated by significant performance gains in downstream tasks such as 3D object classification. The inherent challenge lies in preventing the decoder from exploiting the predicted centers as an easy shortcut for reconstruction, which requires strategies like stop-gradient operations. The strategy ultimately aims to create a pre-training task that is less trivial, promoting better representation learning and boosting overall performance.

Masked Autoencoders#

Masked autoencoders (MAEs) represent a powerful self-supervised learning technique. They work by masking a portion of the input data (e.g., pixels in an image or points in a point cloud) and then training a neural network to reconstruct the masked parts based on the visible parts. This process forces the network to learn rich, meaningful representations of the data, which can be used for downstream tasks. A key advantage of MAEs is their ability to scale to large datasets and complex architectures. However, the effectiveness of MAEs heavily depends on the masking strategy and the design of the encoder and decoder. Different variations exist, optimized for different data types (e.g., images, point clouds) and objectives. Careful consideration is needed regarding the type of masking, the ratio of masked to visible data, and the network’s capacity to effectively reconstruct the missing parts. The choice of reconstruction loss function also plays a critical role in the learning process.

Point Cloud SSL#

Point cloud self-supervised learning (SSL) tackles the challenge of training accurate 3D models with limited labeled data. Existing methods often leverage contrastive learning, comparing augmented views of the same point cloud to learn invariant representations. However, generative approaches, such as masked autoencoders, have gained popularity for their ability to reconstruct masked portions of the point cloud, thereby implicitly learning feature representations. This is particularly valuable for point cloud data, given its inherent sparsity and complexity. A key area of research focuses on optimizing the masking strategies to balance reconstruction difficulty and effective feature learning. Future work will likely explore combining contrastive and generative approaches to capture both local and global relationships in point clouds, as well as exploring more advanced architectural designs tailored to the unique characteristics of this data modality.

Pre-training Efficiency#

Pre-training efficiency is crucial for self-supervised learning in point cloud processing. The paper’s PCP-MAE method demonstrates a significant advantage in this area. By learning to predict center points instead of directly using them, PCP-MAE avoids leaking crucial information to the decoder, which forces the encoder to learn richer semantic representations. This approach, coupled with the parameter sharing between the Predicting Center Module (PCM) and the encoder, results in a pre-training process that’s both faster and more efficient than existing methods, as shown through comparisons with Point-MAE and other state-of-the-art models. The reduced computation time and improved performance highlights a key advantage of PCP-MAE: achieving high accuracy without extensive computational costs, making it a practical and efficient solution for large-scale point cloud data processing.

Future Works#

The ‘Future Works’ section of this research paper presents exciting avenues for extending the PCP-MAE model. Improving the scalability of PCP-MAE to handle larger datasets is crucial, potentially by exploring more efficient patch generation strategies. The authors acknowledge the limitations of relying solely on a generative approach, suggesting that integrating contrastive learning could enhance performance. Furthermore, the single-modal nature of PCP-MAE limits its scope. Therefore, exploring multi-modal learning, incorporating other data modalities like images or depth information, is a natural progression. Finally, there’s the potential for developing explainable AI capabilities to enhance the model’s interpretability, thereby enabling better trust and user understanding of PCP-MAE’s decision-making processes.

More visual insights#

More on figures

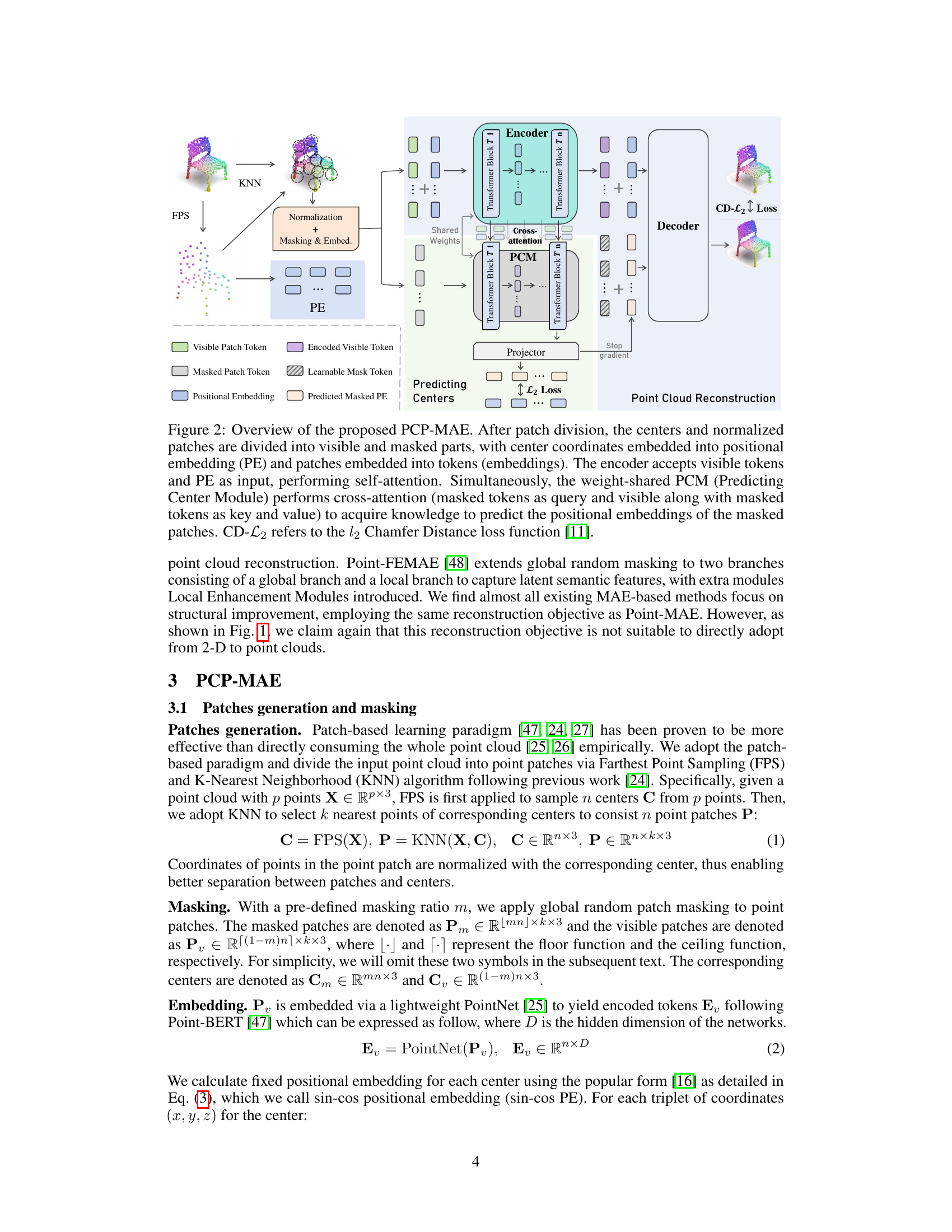

This figure illustrates the architecture of the proposed PCP-MAE method. It shows how the point cloud is divided into patches, which are then processed by the encoder and decoder. The encoder uses self-attention on visible patches and cross-attention with the PCM (Predicting Center Module) to predict the centers of masked patches. The decoder then uses these predicted centers, along with the visible patches, to reconstruct the masked patches. The overall objective is to minimize the Chamfer distance between the reconstructed point cloud and the original point cloud.

This figure illustrates the architecture of PCP-MAE, a novel self-supervised learning method for point clouds. It shows how the encoder processes visible patches and their center coordinates, while the predicting center module (PCM) predicts coordinates for masked patches. The decoder then uses this information to reconstruct the masked point cloud. The figure highlights the key components: Patch generation and masking, encoder with self and cross-attention, PCM with cross attention, and decoder for point cloud reconstruction.

The figure shows the results of masked autoencoder reconstruction experiments. In the left column, 2D images are completely masked (100% mask ratio), and only the positional embedding is fed to the decoder. Reconstruction fails. In the right column, 3D point clouds are completely masked, with only the positional embedding fed to the decoder, and reconstruction is surprisingly successful. This contrast highlights a key difference between 2D and 3D masked autoencoders and motivates the proposed PCP-MAE approach.

More on tables

This table compares PCP-MAE with other single and cross-modal masked autoencoder (MAE) methods for point cloud self-supervised learning. It provides a quantitative comparison across several factors: the type of method (single or cross-modal), whether masked center information is leaked, the number of model parameters, the computational cost (GFLOPS), the pre-training time, and finally the performance on standard benchmarks (ScanObjectNN and ModelNet40). This allows for a comprehensive evaluation of PCP-MAE’s efficiency and effectiveness compared to existing state-of-the-art methods.

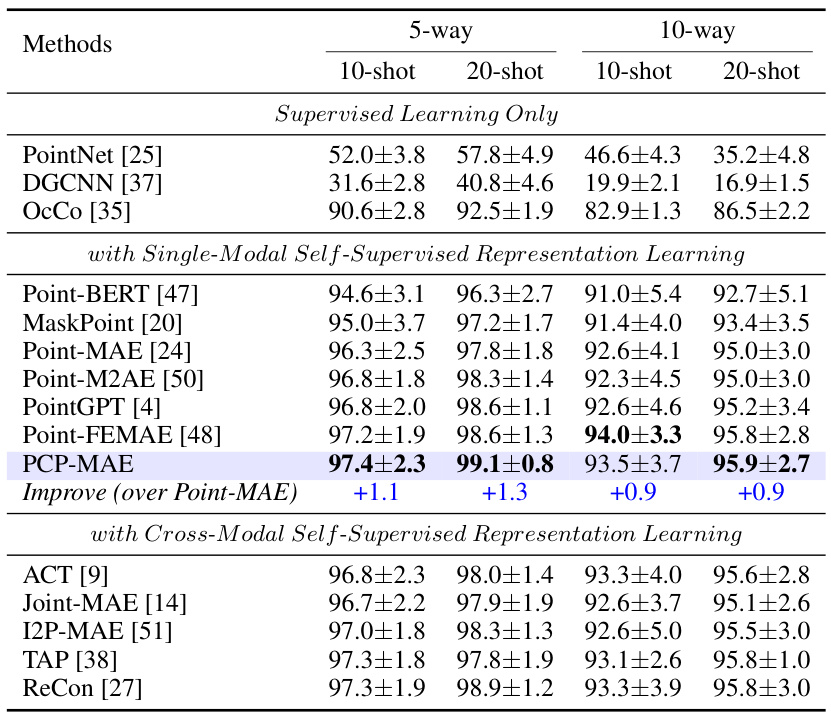

This table presents the results of few-shot learning experiments conducted on the ModelNet40 dataset. The experiments involved different numbers of classes (‘ways’) and examples per class (‘shots’). For each setting, ten independent trials were run, and the table shows the mean accuracy and standard deviation across these trials. The results highlight the model’s performance in low-data scenarios.

This table presents a comparison of different methods for 3D point cloud segmentation on two datasets: ShapeNetPart and S3DIS Area 5. For each method, it reports the Mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) for both part and instance segmentation on ShapeNetPart, and the Mean Accuracy (mAcc) and mIoU for semantic segmentation on S3DIS Area 5. The results show the performance of various self-supervised and supervised learning methods.

This table compares PCP-MAE against other single and cross-modal masked autoencoder (MAE)-based methods for point cloud self-supervised learning (SSL). It presents a comprehensive overview of the methods, considering factors such as whether masked centers are leaked to the decoder, the modality (single or cross-modal), the number of parameters, the computational cost (GFLOPS), pre-training time, and the performance across three standard SSL benchmarks on the ScanObjectNN dataset (OBJ-BG, OBJ-ONLY, PB-T50-RS) and ModelNet40. This allows readers to readily compare the efficiency and effectiveness of PCP-MAE to existing state-of-the-art approaches.

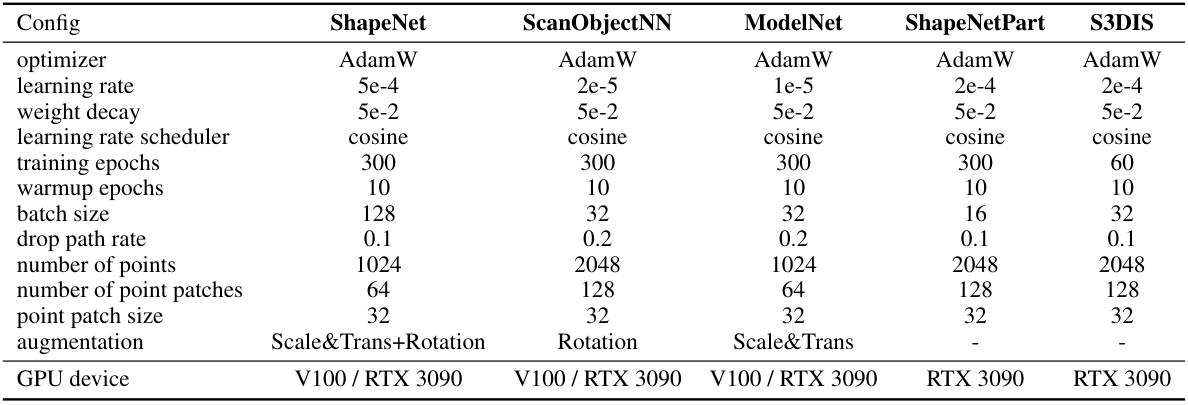

This table details the hyperparameters, optimization settings, and data augmentation techniques used during both the pre-training and downstream fine-tuning phases of the PCP-MAE model. It specifies settings for different datasets (ShapeNet, ScanObjectNN, ModelNet, ShapeNetPart, and S3DIS), providing a comprehensive overview of the experimental setup. The information includes the optimizer used (AdamW), learning rates, weight decay values, learning rate scheduling methods, training epochs, warm-up epochs, batch size, drop path rate, number of points used, number of point patches, point patch size, data augmentation strategies applied and GPU devices used.

This table presents the results of experiments comparing different loss functions used in the PCP-MAE model for 3D object classification on the ScanObjectNN dataset. Three variants of the dataset (OBJ_BG, OBJ_ONLY, and PB_T50_RS) are evaluated, and the accuracy for each is reported. The ℓ2 distance loss function is shown to achieve the best overall results.

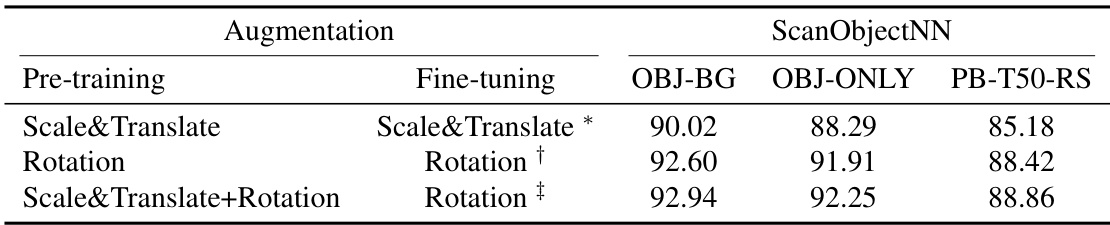

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the impact of different data augmentation techniques used during the pre-training phase of the PCP-MAE model. The accuracy of the model is evaluated on three variants of the ScanObjectNN dataset (OBJ_BG, OBJ_ONLY, PB_T50_RS). The table shows that combining Scale&Translate and Rotation augmentations yields the best performance.

This table compares the performance of Point-MAE under different data augmentation strategies (Scale&Translate, Rotation, and Scale&Translate+Rotation) during both pre-training and fine-tuning stages. The results are presented for three variants of the ScanObjectNN dataset (OBJ-BG, OBJ-ONLY, and PB-T50-RS). The table highlights the impact of augmentation choices on the overall model accuracy, showing that combining Scale&Translate and Rotation provides the best results in this specific experiment.

This table compares the performance of two state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods, Point-FEMAE and ReCon, using the data augmentation strategy proposed in the paper. It shows the accuracy of each method on three different variants of the ScanObjectNN dataset (OBJ-BG, OBJ-ONLY, and PB-T50-RS). The results demonstrate that the proposed augmentation strategy affects the performance of these SOTA methods and yields slightly lower accuracy when compared to their original performance with their original augmentations.

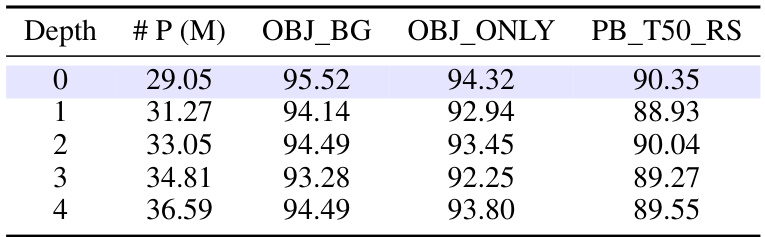

This table shows the impact of varying the number of transformer layers within the projector module of the PCP-MAE model on the accuracy of 3D object classification. The results are presented for three different variants of the ScanObjectNN dataset: OBJ_BG, OBJ_ONLY, and PB_T50_RS. The default configuration (marked in blue) uses zero layers. Increasing the depth of the projector generally does not improve performance, indicating that simple prediction is sufficient.

This ablation study analyzes the impact of sharing parameters between the encoder and the Predicting Center Module (PCM) on the model’s performance. The table presents accuracy results for three variants of the ScanObjectNN dataset (OBJ_BG, OBJ_ONLY, PB_T50_RS). The ‘shared’ row shows the results when the encoder and PCM share parameters, while the ’non-shared’ row shows the results when they do not. The default setting (in blue) demonstrates superior performance with shared parameters, highlighting their beneficial impact on model accuracy.

Full paper#