↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current single-view 3D reconstruction methods often produce visually appealing objects that are physically implausible when subjected to real-world forces, exhibiting problems like toppling or deformation. This significantly limits their applicability in various fields requiring physically accurate models, such as robotics, animation and manufacturing. Addressing these limitations is crucial for broadening the applications of single-image 3D modeling.

This research introduces a novel computational framework that incorporates physical compatibility into the 3D reconstruction process. By explicitly decomposing a physical object’s visual representation into its mechanical properties, external forces, and rest-shape geometry, and linking them through static equilibrium, the framework generates physically accurate 3D models that closely match input images and behave realistically under real-world forces. The method is rigorously evaluated and demonstrates significant improvements in physical realism compared to existing techniques. The resulting models are shown to be suitable for dynamic simulations and 3D printing, showcasing the framework’s practical utility.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in computer graphics, computer vision, and robotics because it bridges the gap between visual representations and physical reality. By addressing the limitations of current single-image 3D reconstruction methods that neglect physical properties, this research opens new avenues for creating realistic and functional 3D models, advancing applications in dynamic simulations and 3D printing. It also introduces novel evaluation metrics for physical compatibility, enhancing the rigor of future research in this area.

Visual Insights#

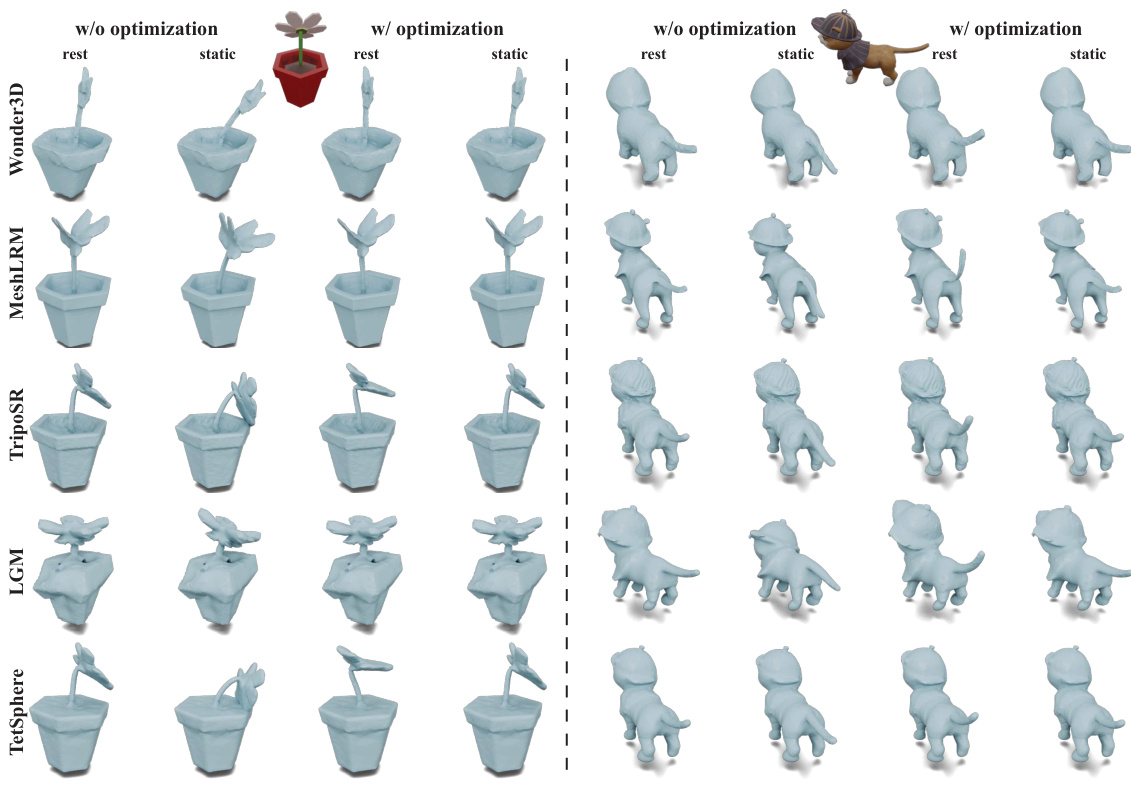

This figure shows a comparison between existing single-view 3D reconstruction methods and the proposed method. The top row displays examples of objects reconstructed by existing methods that exhibit unrealistic behavior when subjected to physical forces like gravity (toppling or deformation). The bottom row shows examples of the same objects reconstructed using the proposed method, which maintain stability and accurately reflect their static equilibrium state as shown in the input images.

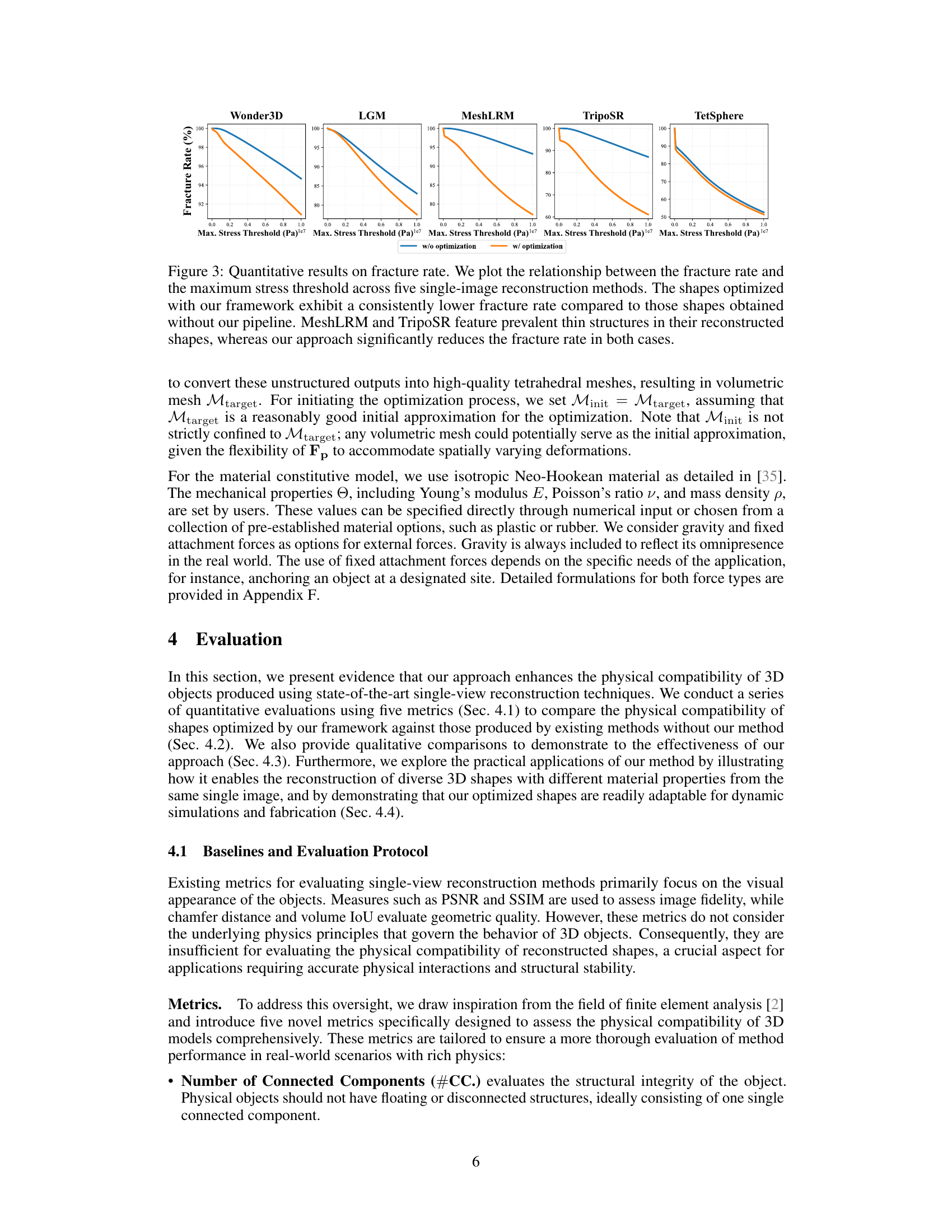

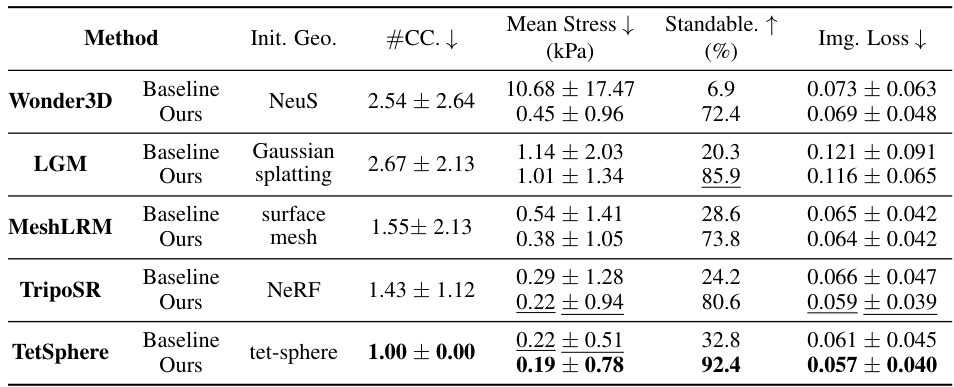

This table presents a quantitative comparison of physical compatibility metrics between baseline single-image 3D reconstruction methods and those methods enhanced by the proposed physical compatibility optimization. Four metrics are used: the number of connected components (#CC), mean stress (kPa), standability percentage, and image loss. Lower #CC and mean stress, as well as higher standability percentage and lower image loss indicate better physical compatibility. The results show consistent improvement across all methods when the optimization is applied, with TetSphere exhibiting the most significant gains.

In-depth insights#

Single-View Physics#

Single-view 3D reconstruction, aiming to create a 3D model from a single image, presents significant challenges. Traditional methods often struggle to accurately capture physical properties and real-world interactions. A focus on ‘Single-View Physics’ would involve developing techniques that incorporate physical constraints directly into the reconstruction process. This could entail integrating physics-based simulations or incorporating prior knowledge of material properties, external forces (like gravity), and object stability. The goal is not simply to produce a visually realistic 3D model, but one that also behaves realistically under physical manipulation. Key innovations might include novel loss functions incorporating physics-based metrics or the integration of physics engines for real-time object simulation within the reconstruction framework. This emphasis on physical realism would lead to more robust and reliable 3D models useful in a wider array of applications, from robotics and virtual reality to 3D printing and engineering design. Challenges include dealing with ambiguities inherent in a single view, accurate material property estimation from images alone, and computationally efficient methods for incorporating physics simulations. Success would significantly advance the field of computer vision and its practical applications.

Physically-Aware 3D#

Physically-aware 3D modeling aims to integrate physical principles into the creation and manipulation of three-dimensional objects. This contrasts with traditional methods that often treat 3D models as purely geometric entities, ignoring properties like mass, material properties, and physical forces. A physically-aware approach ensures that generated objects behave realistically under various conditions (gravity, collisions, etc.), leading to more lifelike simulations and enabling applications such as realistic virtual environments and accurate physical simulations for engineering purposes. Key challenges include accurately modeling material behavior, efficiently simulating complex physical interactions, and integrating physics simulations seamlessly with 3D modeling workflows. The ultimate goal is to bridge the gap between the virtual and physical worlds, creating 3D models that not only look realistic but also behave realistically. This often involves sophisticated physics engines and numerical methods, demanding significant computational resources. The resulting increase in realism and accuracy, however, opens up a wider range of applications and benefits across various fields.

Equilibrium Constraint#

The concept of ‘Equilibrium Constraint’ within the context of physically-based 3D object modeling from a single image is crucial. It represents the core principle that governs the interaction between internal forces (from material properties and object deformation) and external forces (like gravity). Successfully enforcing this constraint ensures that the generated 3D model behaves realistically under the influence of these forces, maintaining stability and accurately reflecting its depicted state in the input image. This constraint is not merely a soft penalty but a hard constraint, implying that the optimization process must explicitly satisfy the equilibrium condition rather than simply approximating it. Failure to meet this condition often results in physically implausible objects that topple or deform unexpectedly, undermining the overall realism and utility of the model. Therefore, the implementation of the equilibrium constraint is central to the success of the proposed framework, allowing for the generation of robust, stable 3D objects that faithfully reflect both the visual appearance and physical behavior of their real-world counterparts.

Material Property Ablation#

A thoughtful exploration of a hypothetical ‘Material Property Ablation’ section within a research paper on physically compatible 3D object modeling would reveal crucial insights into the model’s robustness and fidelity. Such a section would likely involve systematically varying material properties (like Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and density) while holding other variables constant. The resulting 3D models, generated from the same input image, would then be evaluated under various physical conditions (such as gravity and external forces). This ablation study would reveal if changes in material properties affect only the rest-shape geometry or influence the final static equilibrium pose. Significant deviations from the expected behavior would highlight potential weaknesses in the model’s ability to accurately capture and translate the complex relationship between material properties and visual geometry. Conversely, consistency in final poses across varied materials would strongly support the model’s accuracy and ability to handle diverse material characteristics. The results of such an ablation study would be critical in assessing the generalization capability of the 3D modeling framework. Ultimately, this analysis would be key to determining the model’s suitability for practical applications demanding realism and fidelity under diverse material scenarios.

Future 3D Modeling#

Future 3D modeling research should prioritize integrating physics and material properties more realistically into the creation process, moving beyond simplistic visual representations. This will involve refining techniques for accurately inferring material properties from limited input data (like single images) and developing efficient methods for simulating complex physical interactions. Advancements in data-driven approaches can leverage vast datasets of 3D objects and their physical properties to improve accuracy and reduce computational costs. A key area of focus will be creating models that are not only visually accurate but also physically plausible, capable of withstanding forces and behaving naturally in simulations and real-world scenarios. Furthermore, research should explore new representations and efficient algorithms to handle diverse materials and complex geometries. The goal is to bridge the gap between the virtual and the physical, leading to more realistic and practical applications of 3D models.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows a comparison between existing single-view 3D reconstruction methods and the proposed method. The top row displays examples of objects reconstructed by existing methods that fail to maintain stability or exhibit undesired deformation under real-world physical forces. The bottom row shows examples of objects reconstructed by the proposed method which maintain stability and accurately reflect their static equilibrium state.

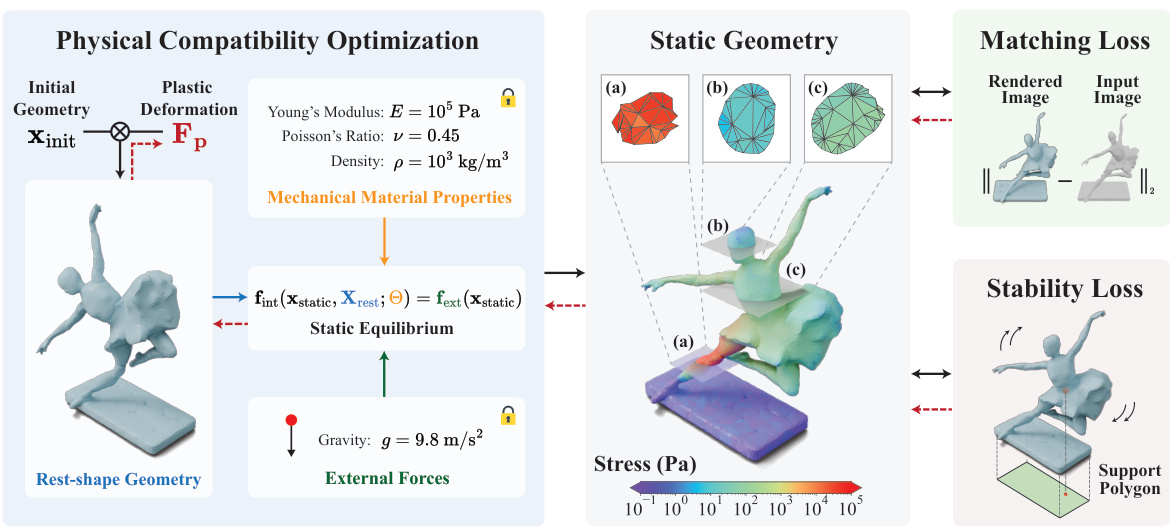

This figure illustrates the overall pipeline of the proposed method. It shows how predefined mechanical properties and external forces are used as input to optimize the rest-shape geometry. This optimization is constrained by the principle of static equilibrium and aims to ensure alignment with the target image while meeting stability criteria. The output is a physically compatible 3D model which matches the input image and behaves realistically in a simulation under external forces such as gravity.

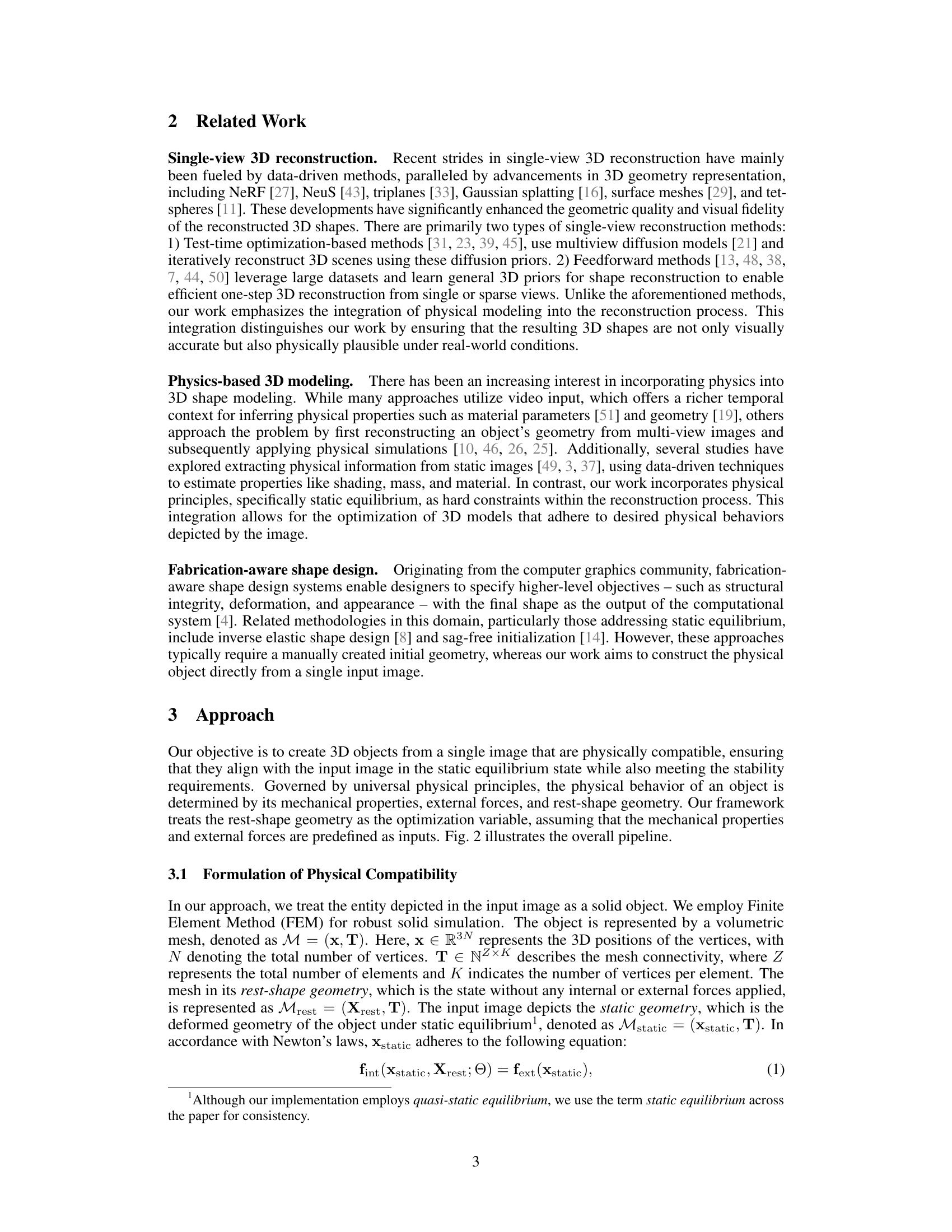

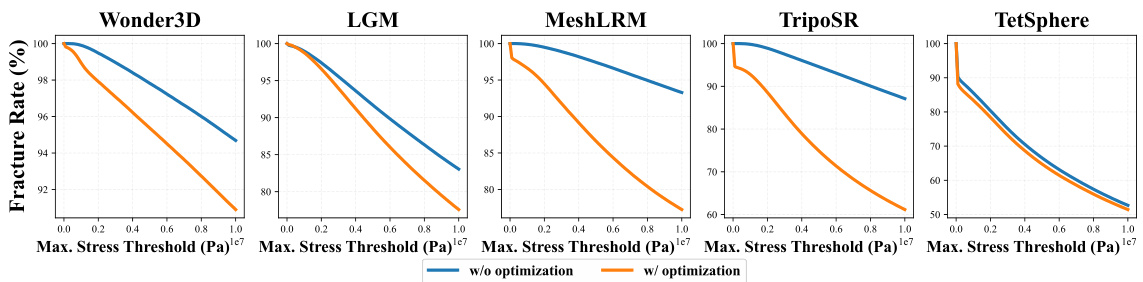

This figure shows the fracture rate (percentage) plotted against the maximum stress threshold (Pascals) for five different single-image 3D reconstruction methods. Each method is represented by two lines: one for results without the authors’ optimization framework applied and one with the optimization applied. The results show that, across all five methods, applying the optimization significantly reduces the fracture rate at all stress thresholds. This is particularly noticeable for MeshLRM and TripoSR, which exhibit considerably higher fracture rates without optimization due to thinner structures in their reconstructions. The improved fracture resistance with the optimization highlights the enhanced physical realism and robustness of the resulting 3D models.

This figure shows a comparison of the results obtained with and without the authors’ proposed physical compatibility optimization. The left side shows that optimized rest shapes closely match the input images when subjected to gravity, unlike the unoptimized shapes. The right side demonstrates that the optimized shapes are stable and self-supporting, whereas the unoptimized shapes are not.

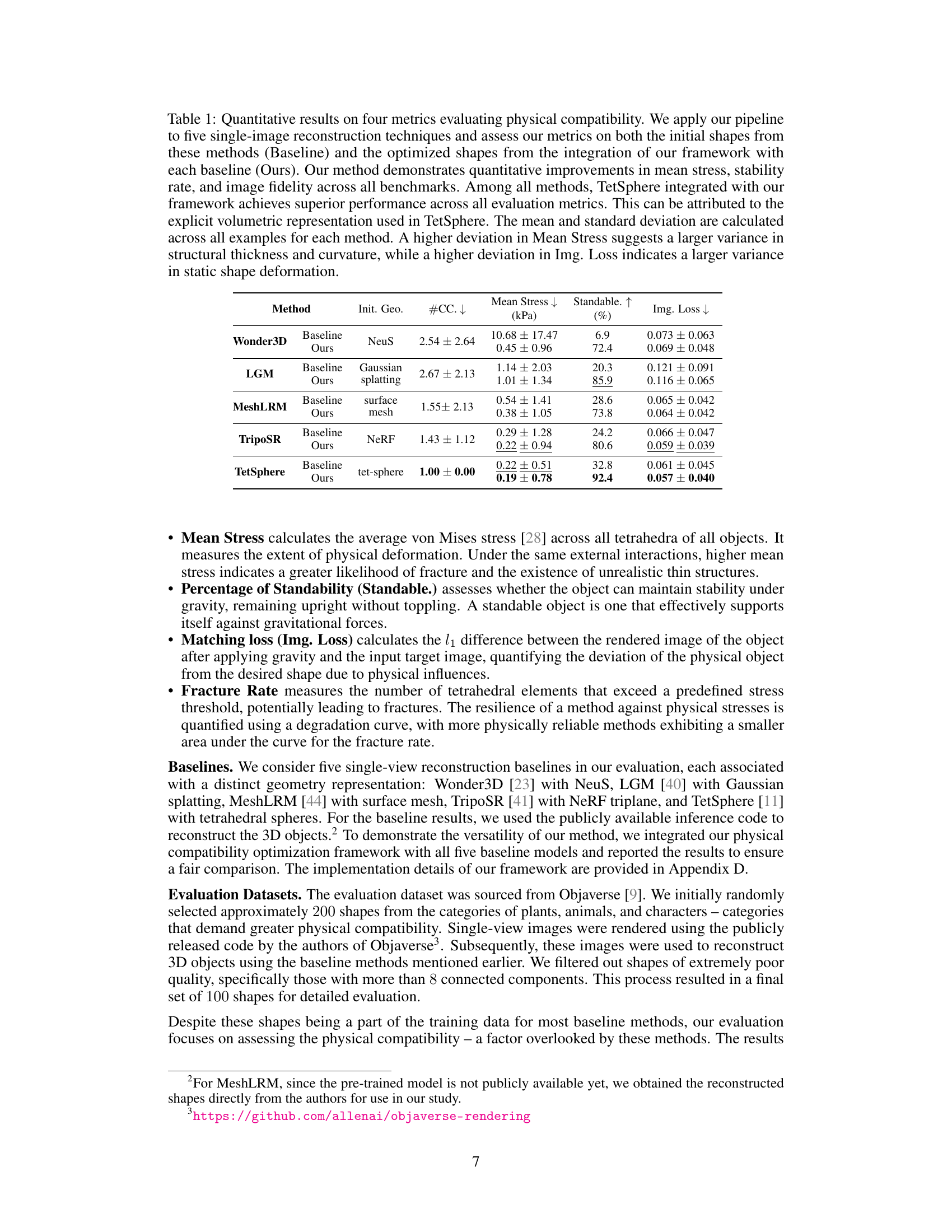

This figure shows an ablation study on how different Young’s modulus values affect the resulting shapes. The top row displays various rest-shape geometries produced by changing the material property. The middle row demonstrates that, under static equilibrium, these different rest shapes all result in the same static shape. The bottom shows how different material properties lead to different deformations under the same external force (compression from a yellow block). This highlights that the framework controls object behavior by decomposing the different physical attributes.

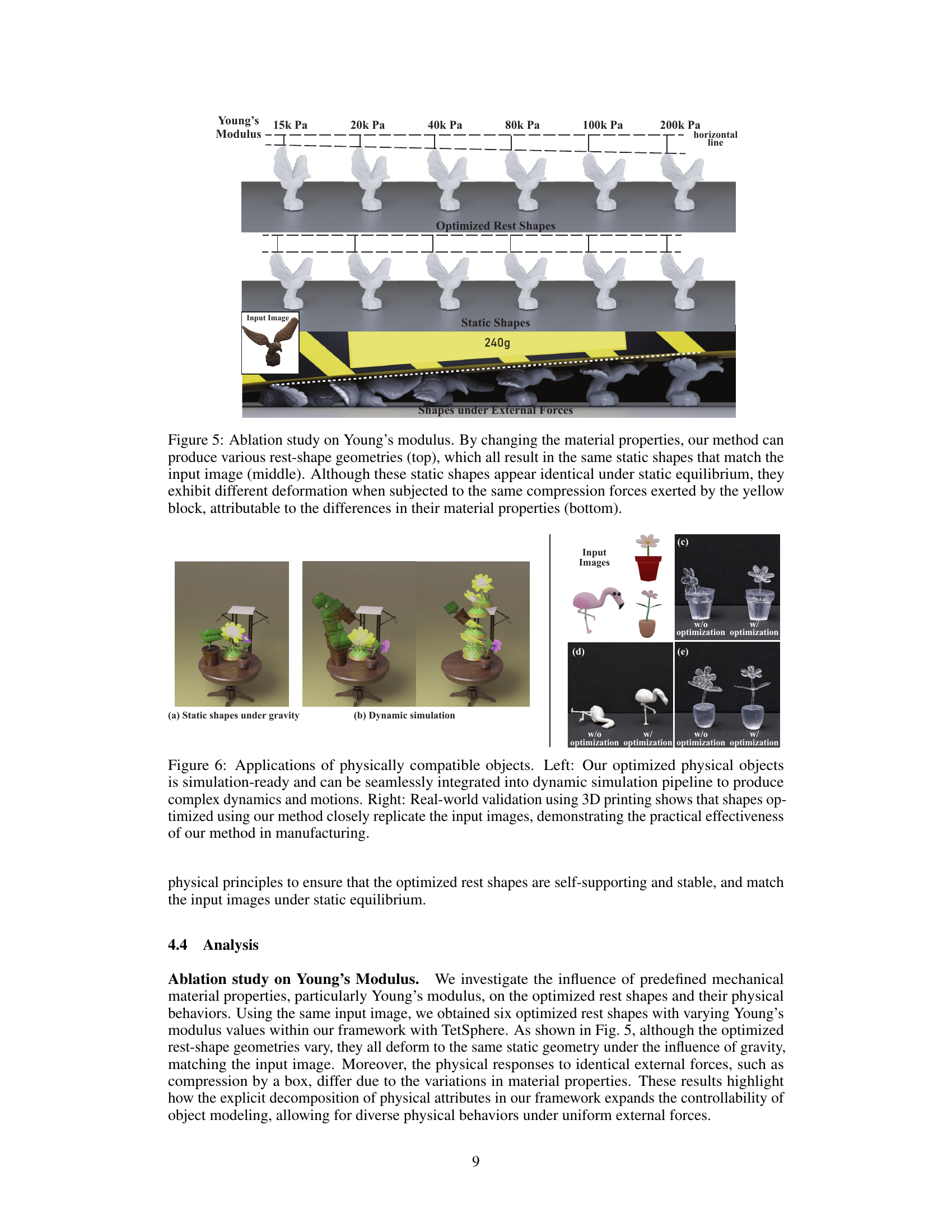

This figure demonstrates the applicability of the proposed method in two scenarios: dynamic simulation and 3D printing. The left side shows a dynamic simulation of three plants, exhibiting realistic motion under gravity and wind. The right side presents real 3D-printed objects, showcasing the accuracy in replicating the input images, indicating the method’s practicality in manufacturing.

This figure shows a comparison of 3D object reconstruction results with and without the authors’ proposed physical compatibility optimization. The left side demonstrates that the optimized rest shapes accurately match the input image geometry under gravity, while the unoptimized shapes do not. The right side shows that the optimized shapes are stable, while the unoptimized ones are not.

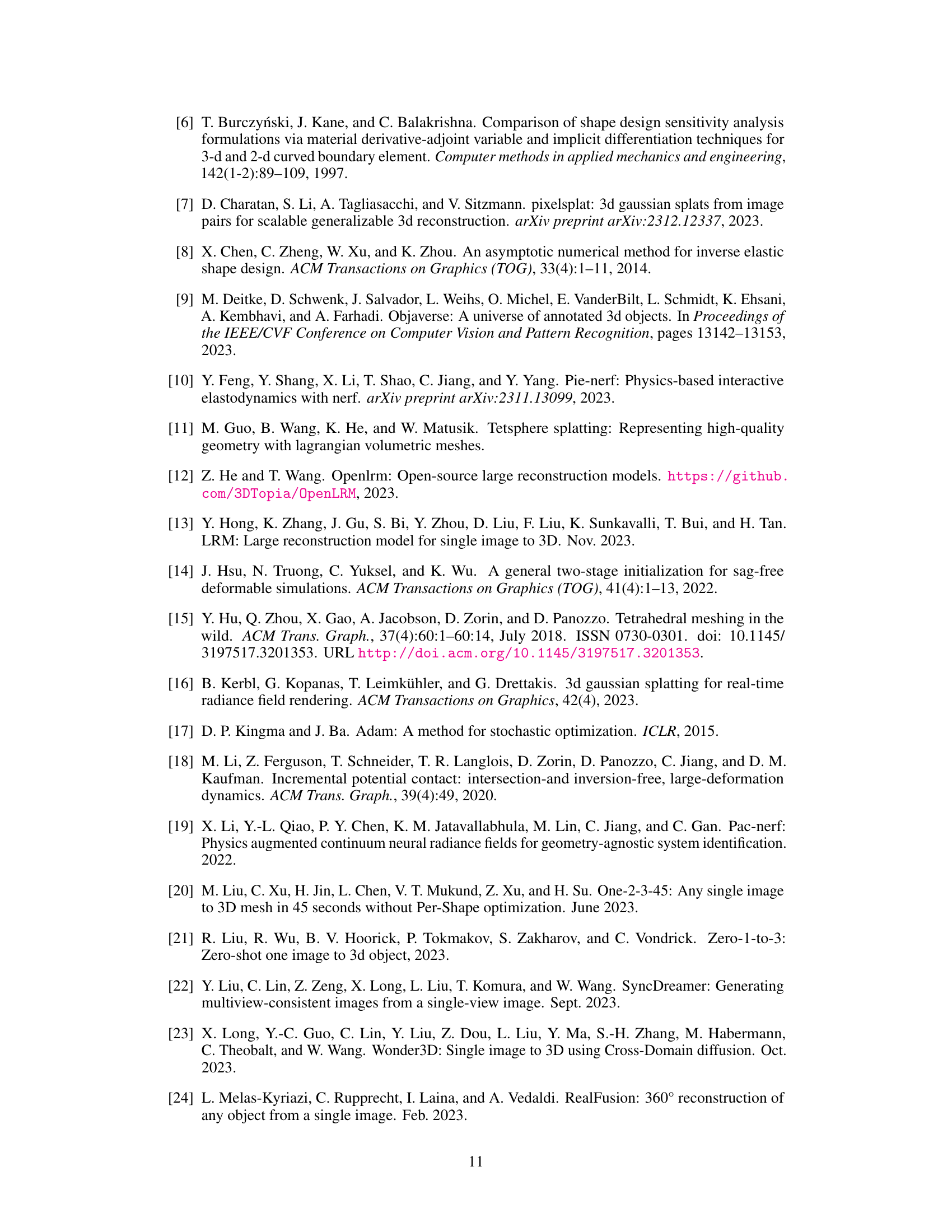

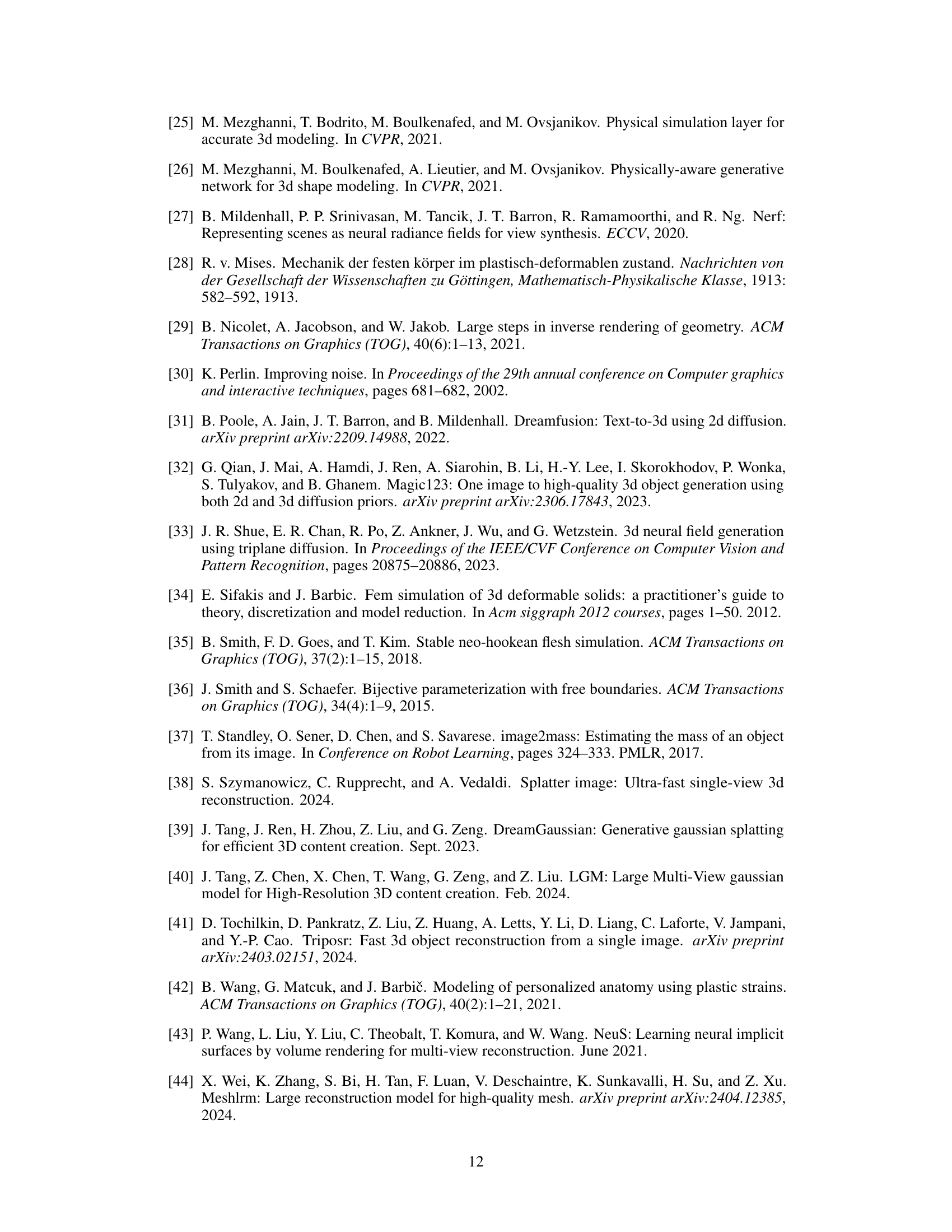

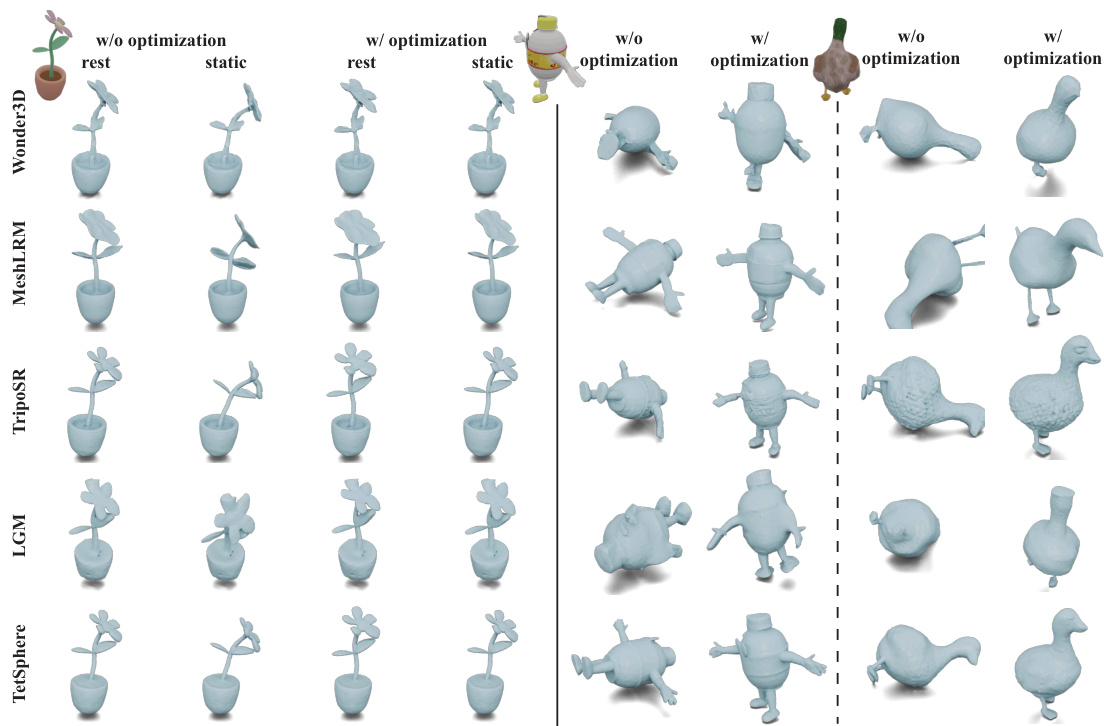

This figure shows additional qualitative results of physical compatibility optimization. It demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed optimization framework in generating physically realistic 3D objects. The left side shows the results of using five different single-view reconstruction methods without the optimization framework, while the right side displays the results with the optimization framework applied. The comparison highlights the improvement in physical compatibility and realism achieved by the optimization framework. The results are presented for different types of 3D models including plants and animals.

Full paper#