↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

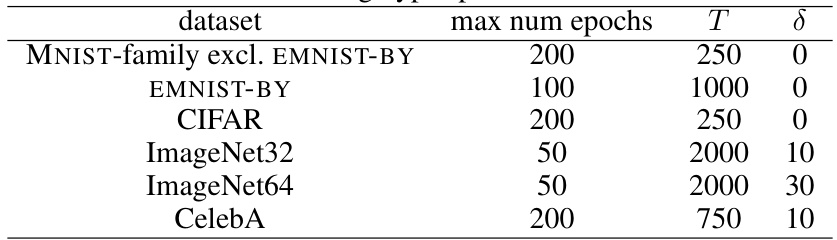

Many successful generative models utilize continuous latent variables, but inference remains intractable. Probabilistic integral circuits (PICs) offer a solution by representing models symbolically, but existing methods were limited to tree-structures, hindering scalability and expressiveness. This limitation made it challenging to learn complex distributions from data and limited the application of PICs to larger datasets. This paper introduces several key advancements to address these limitations.

The authors present a pipeline for constructing PICs with more flexible Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) structures beyond the previous tree-like constraints. They introduce a technique for approximating intractable PICs using tensorized probabilistic circuits (QPCs), which efficiently encode a hierarchical numerical quadrature process. Furthermore, neural functional sharing significantly enhances the training scalability of PICs by parameterizing them with multi-headed multi-layer perceptrons, thereby reducing computational costs and memory requirements. Extensive experiments demonstrate the effectiveness of these techniques, showcasing improved performance and scalability compared to traditional approaches.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on probabilistic modeling and deep generative models. It significantly advances the scalability and expressiveness of probabilistic integral circuits (PICs), a powerful yet previously limited class of models for handling continuous latent variables. The techniques introduced, particularly functional sharing, enable training of far larger and more complex models than previously possible, opening new avenues for research in probabilistic reasoning and generative modeling.

Visual Insights#

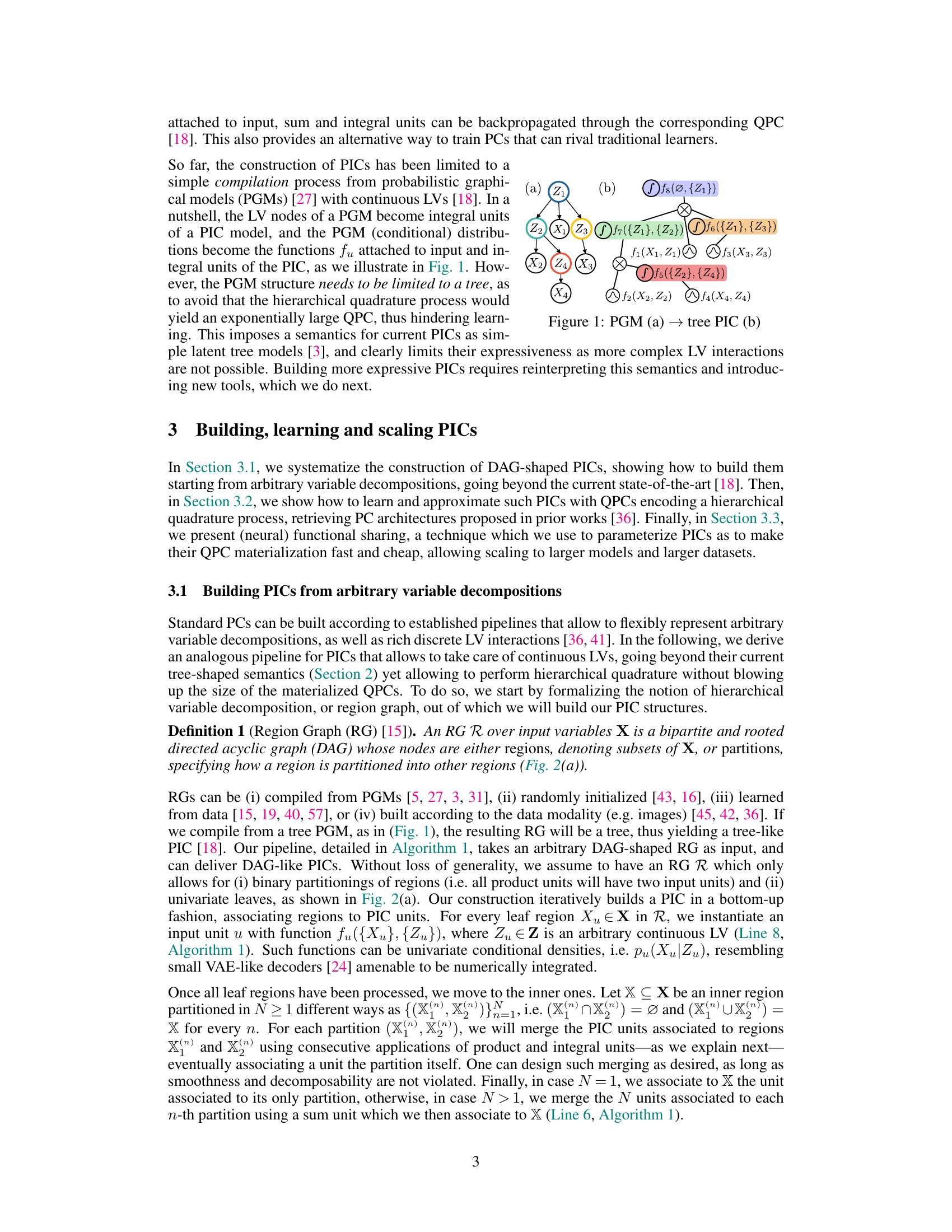

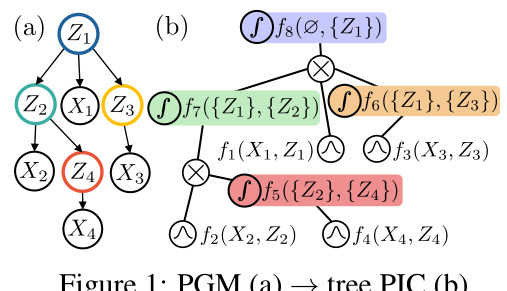

This figure illustrates the transformation of a Probabilistic Graphical Model (PGM) into a tree-shaped Probabilistic Integral Circuit (PIC). Panel (a) shows a simple PGM with continuous latent variables (Z1, Z2, Z3) and observed variables (X1, X2, X3, X4). Panel (b) displays the equivalent PIC, where the latent variables in (a) become integral units in (b), and the conditional distributions from (a) become the functions associated with the input and integral units in (b). The structure of the PGM directly informs the structure of the PIC. This conversion highlights the method used to translate between PGM representation and PIC representation, showcasing the hierarchical structure of continuous latent variables that PICs can capture.

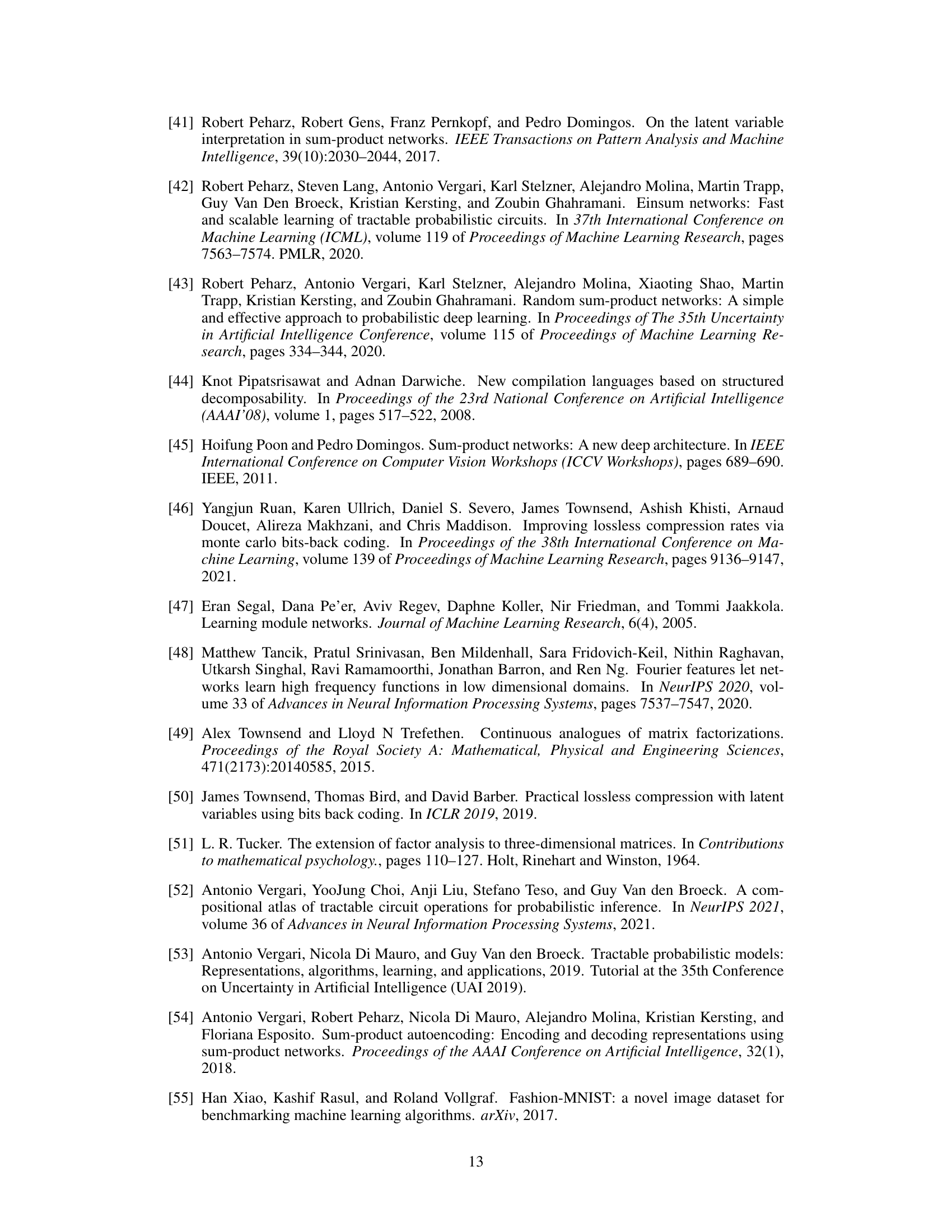

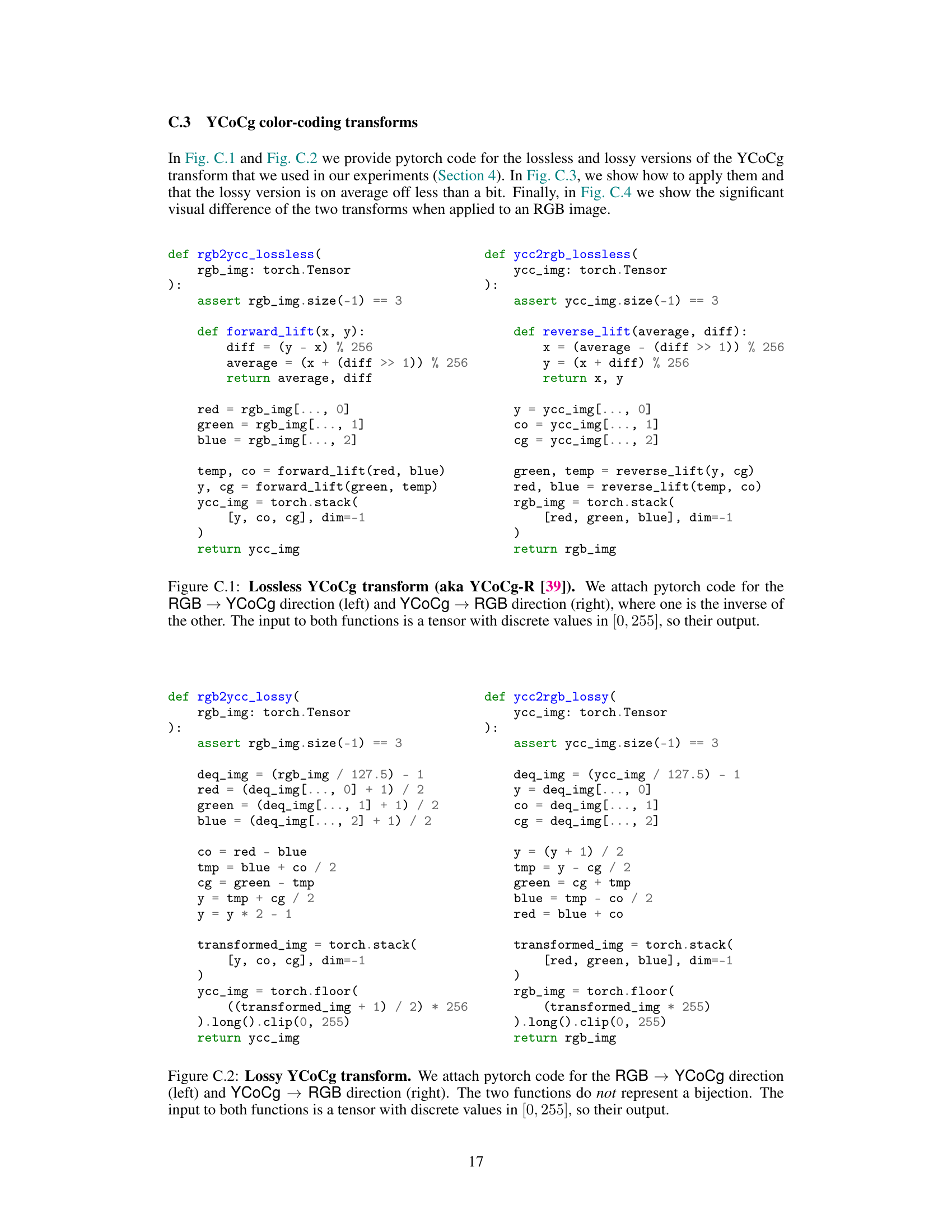

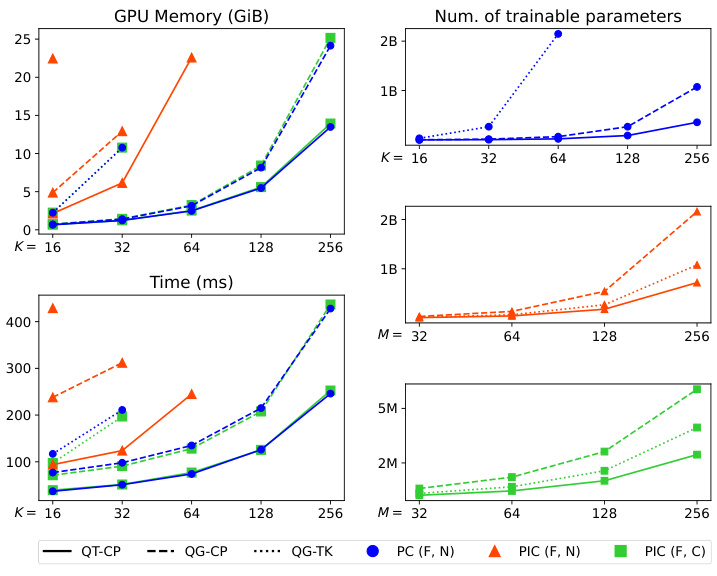

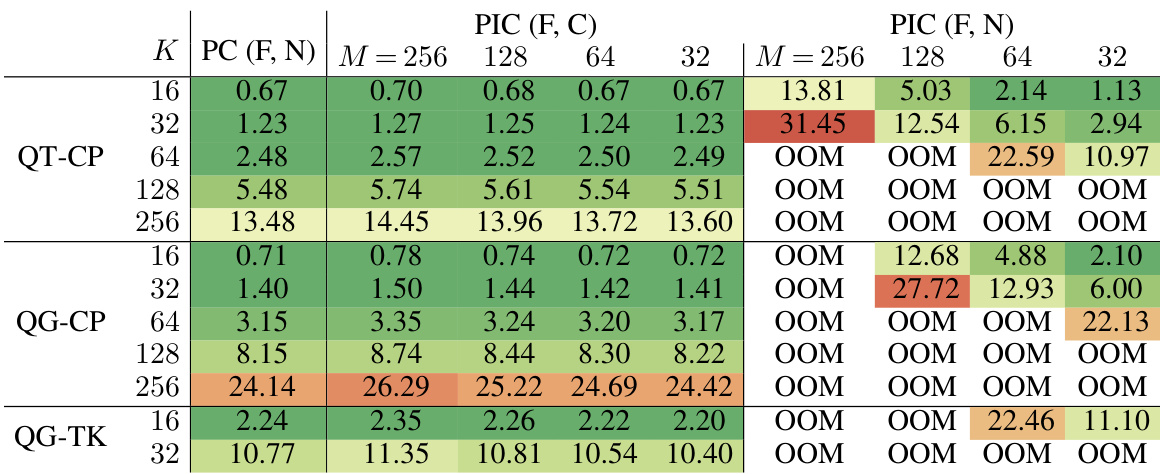

This table compares the training time and GPU memory usage for Probabilistic Integral Circuits (PICs) with different functional sharing techniques and standard Probabilistic Circuits (PCs). It shows how the choice of architecture, the number of quadrature points (K), and the sharing technique affect the computational cost of training.

In-depth insights#

PICs: DAG-shaped#

The concept of DAG-shaped Probabilistic Integral Circuits (PICs) represents a significant advancement in probabilistic modeling. Moving beyond the limitations of tree-structured PICs, this extension allows for the representation of more complex relationships between continuous latent variables. This is achieved through a systematic pipeline that constructs DAG-shaped PICs from arbitrary variable decompositions, overcoming the previous constraints imposed by tree-like structures. The ability to handle DAGs dramatically enhances the expressiveness of PICs, enabling them to model intricate dependencies and interactions that were previously intractable. This extension is particularly crucial for applications dealing with high-dimensional data and complex probabilistic reasoning tasks. Furthermore, the introduction of tensorized QPCs for approximation and the implementation of functional sharing techniques are crucial for scalability. Tensorization allows for efficient representation of continuous variables while functional sharing dramatically reduces the number of trainable parameters, making training feasible at scale. The combination of these improvements signifies a powerful leap towards the development of more expressive and scalable probabilistic models.

QPC Approx.#

The heading ‘QPC Approx.’ likely refers to a section detailing the approximation of Probabilistic Integral Circuits (PICs) using Quadrature Probabilistic Circuits (QPCs). This approximation is crucial because PICs, while theoretically expressive for modeling continuous latent variables, often become intractable for inference and learning. QPCs offer a tractable alternative by employing numerical quadrature to approximate the integral computations inherent in PICs. The discussion would likely cover the methods used for this approximation, including the choice of quadrature rules (e.g., Gaussian quadrature) and the impact of the number of quadrature points on accuracy and computational cost. A key aspect would be the trade-off between accuracy and efficiency: more quadrature points improve accuracy but increase computational burden. The section would also likely discuss how the parameters of the approximating QPC are learned, perhaps using methods like maximum likelihood estimation or variational inference. Finally, the effectiveness of the QPC approximation would be assessed and compared to other methods for approximating PICs, highlighting the advantages and limitations of QPC approximation in terms of accuracy, scalability, and learning performance.

Functional Sharing#

The concept of “Functional Sharing” in the context of this research paper centers on optimizing the training process of Probabilistic Integral Circuits (PICs) by intelligently reusing and sharing the same functions across multiple units within the PICs architecture. This approach, especially useful in conjunction with the neural network-based parameterizations used in the paper, drastically reduces the computational burden of training by minimizing redundancy. Sharing functions effectively decreases the number of trainable parameters, improving memory efficiency, and accelerating training times. The authors explore two primary types of functional sharing: F-sharing (full sharing) where functions are identical, and C-sharing (composite sharing) where functions are composed of shared inner functions. The effectiveness of this technique is experimentally demonstrated in the paper, showcasing significant improvements in scalability and training efficiency compared to both standard PICs and other state-of-the-art probabilistic circuit models.

Scalable Training#

The concept of “Scalable Training” in the context of probabilistic integral circuits (PICs) addresses the challenge of training increasingly complex models with continuous latent variables. The primary bottleneck lies in the computational cost of numerical quadrature, which is used to approximate integrals during training. The authors tackle this by proposing several strategies. First, they introduce a pipeline for building more general Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG)-shaped PICs, moving beyond simpler tree structures. This allows for more flexible model architectures and potentially improved expressiveness. Second, they utilize tensorized circuit architectures, and third, they employ neural functional sharing techniques to significantly reduce the number of trainable parameters, thereby decreasing both computational demands and memory requirements during training. These improvements allow for more efficient and effective training of larger and more intricate models, leading to improved scalability and overall performance. The effectiveness of the methods, particularly the functional sharing, is demonstrated through extensive experiments. The functional sharing approach shows remarkable improvements, suggesting a practical method to increase the size and complexity of trainable PIC models.

Future Work#

The paper’s lack of a dedicated ‘Future Work’ section is a missed opportunity. Several promising avenues for extending this research are apparent. Investigating more efficient training methods for PICs, perhaps leveraging variational inference or alternative optimization techniques beyond maximum likelihood estimation, would be valuable. Addressing the current limitations in scalability, particularly regarding the memory-intensive nature of QPC materialization, is crucial. This could involve exploring novel architectures or approximation strategies for hierarchical quadrature. Developing efficient sampling methods for PICs is another important direction, enabling generative applications and full probabilistic reasoning. Finally, a broader investigation into the expressiveness and theoretical properties of DAG-shaped PICs, compared to their tree-structured counterparts, would enhance the understanding of this model’s capabilities and limitations. These extensions would solidify PICs as a powerful tool within the tractable probabilistic modeling landscape.

More visual insights#

More on figures

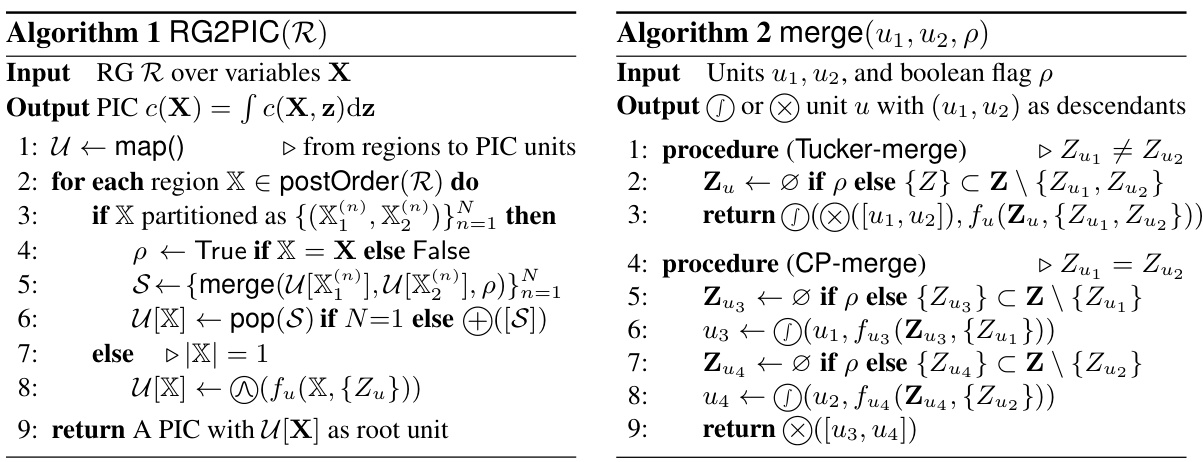

This figure illustrates the four-step pipeline for building and training Probabilistic Integral Circuits (PICs). It starts with an arbitrary Directed Acyclic Graph-shaped Region Graph (RG) which represents a hierarchical variable decomposition. This RG is then converted into a DAG-shaped PIC using Algorithm 1 and the Tucker-merge technique. The intractable PIC is then approximated by a tensorized Quadrature Probabilistic Circuit (QPC) using Algorithm 3 and a hierarchical quadrature process. Finally, the QPC is folded to improve inference speed.

This figure illustrates the process of converting a 3-variate function into a sum-product layer using multivariate numerical quadrature. It shows how an infinite quasi-tensor representation (a) is first approximated as a finite tensor (b) using integration points and weights, then flattened into a matrix (c) and finally used to parameterize a Tucker layer (d), a common architecture in probabilistic circuits.

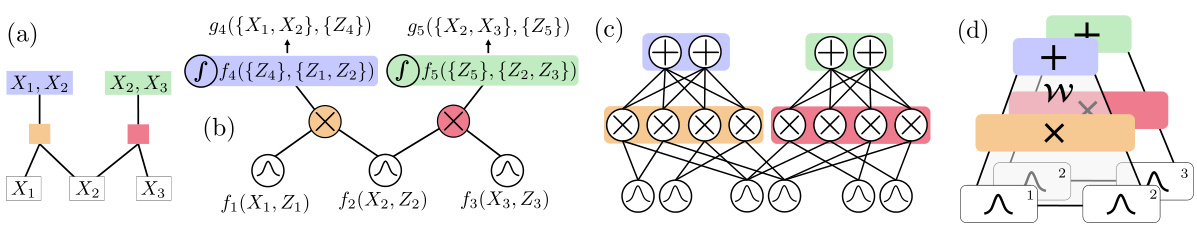

This figure illustrates the concept of neural functional sharing in the context of Probabilistic Integral Circuits (PICs). It shows how a multi-headed Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) with Fourier Features can parameterize a group of integral units within a PIC. The process of materializing the PIC into a Quadrature Probabilistic Circuit (QPC) leads to a folded CP-layer, which is a more efficient representation. The key idea is that the MLP is only evaluated K^2 times (K being the number of quadrature points), instead of 4K^2 times, resulting in computational savings.

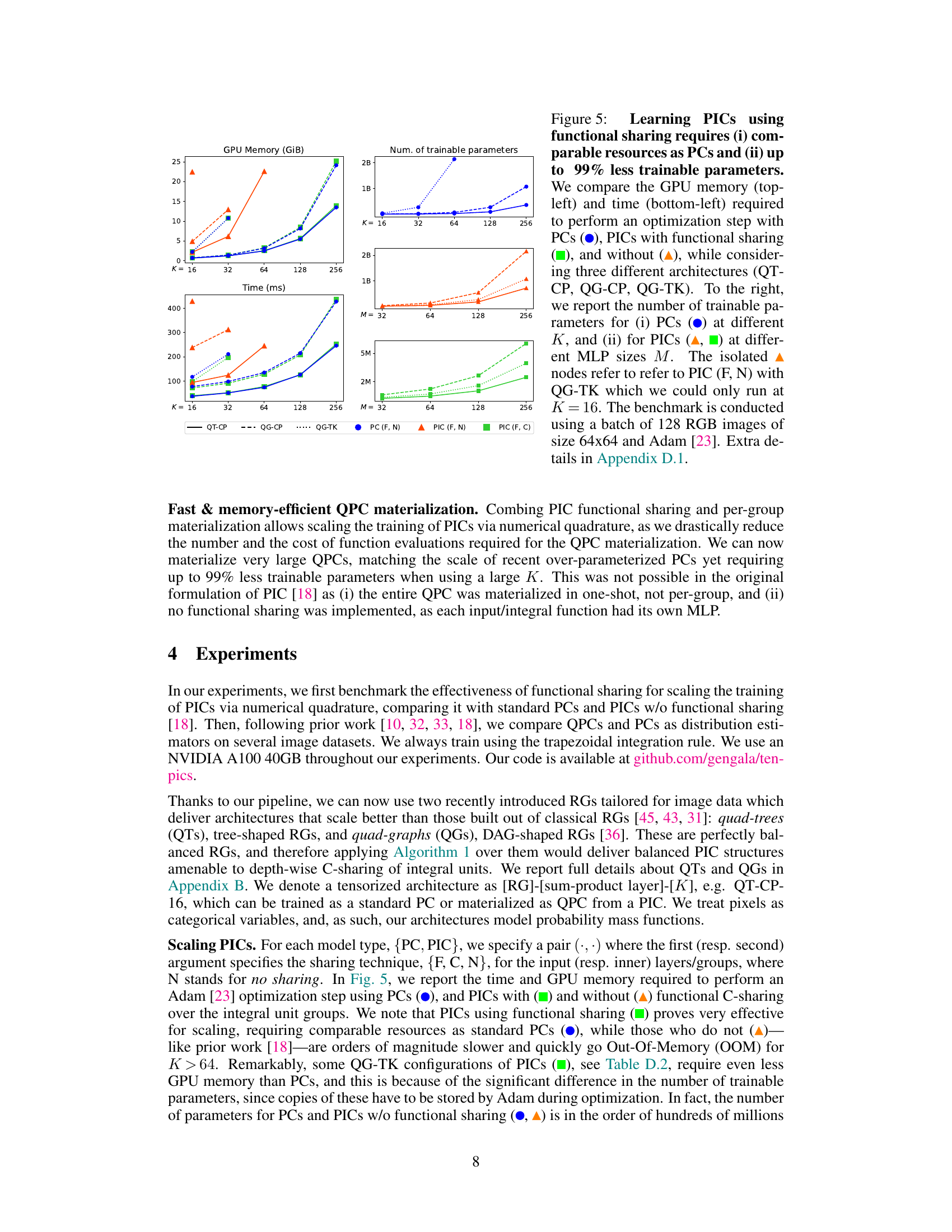

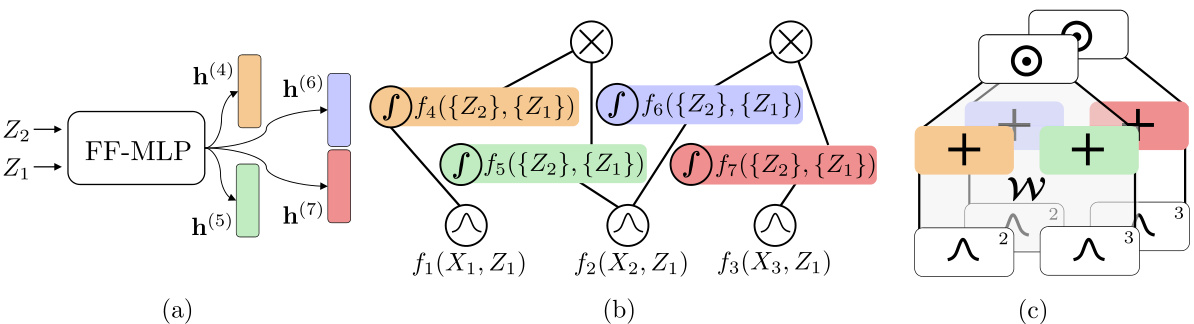

This figure compares the GPU memory and time required for training Probabilistic Integral Circuits (PICs) with and without functional sharing against standard Probabilistic Circuits (PCs). It demonstrates that functional sharing allows PICs to scale similarly to PCs, while requiring significantly fewer parameters (up to 99% less). The figure also shows the number of trainable parameters for PCs and PICs with varying parameters (K and M).

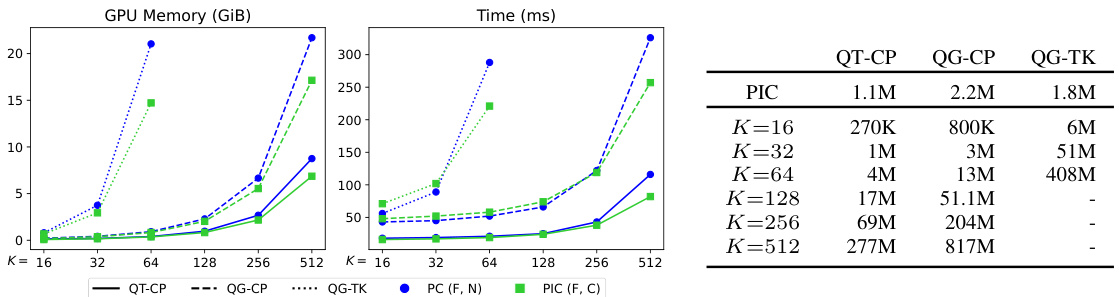

This figure compares the GPU memory and time required for an optimization step using PCs, PICs with functional sharing, and PICs without functional sharing. It also shows the number of trainable parameters for PCs and PICs with different architectures and hyperparameters. The results demonstrate that using functional sharing in PICs reduces the resources required for training compared to PCs and PICs without functional sharing.

This figure illustrates the four stages of the proposed pipeline for building and training probabilistic integral circuits (PICs). It starts with a region graph (RG), a DAG representing a hierarchical decomposition of variables. This RG is then converted into a DAG-shaped PIC using Algorithm 1 and a merging strategy (Tucker-merge shown here, but CP-merge is another option). The resulting PIC, if intractable, is then approximated by a tensorized quadrature probabilistic circuit (QPC) via Algorithm 3, which encodes the hierarchical quadrature process. Finally, to speed up inference, the QPC is folded, reducing the number of layers while maintaining the expressiveness.

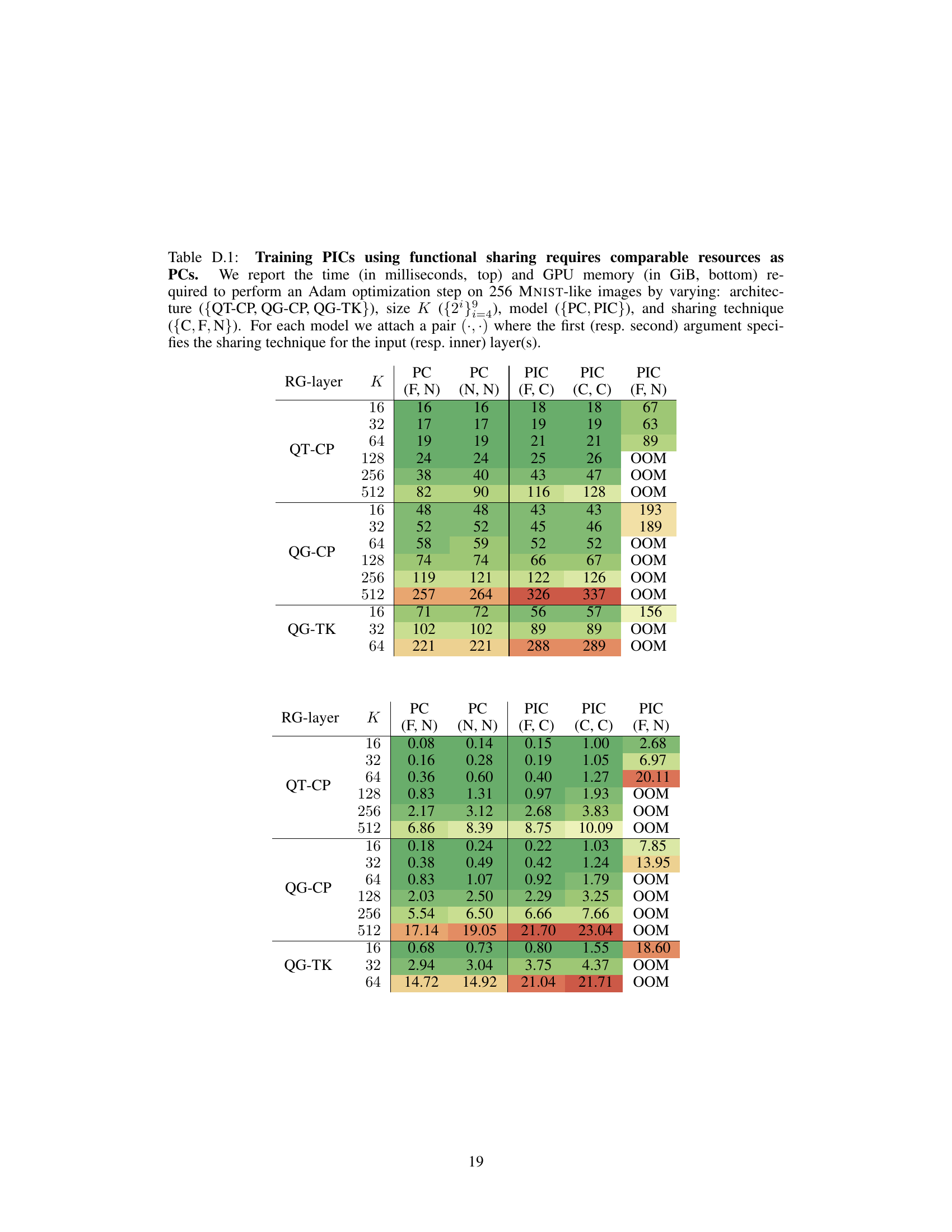

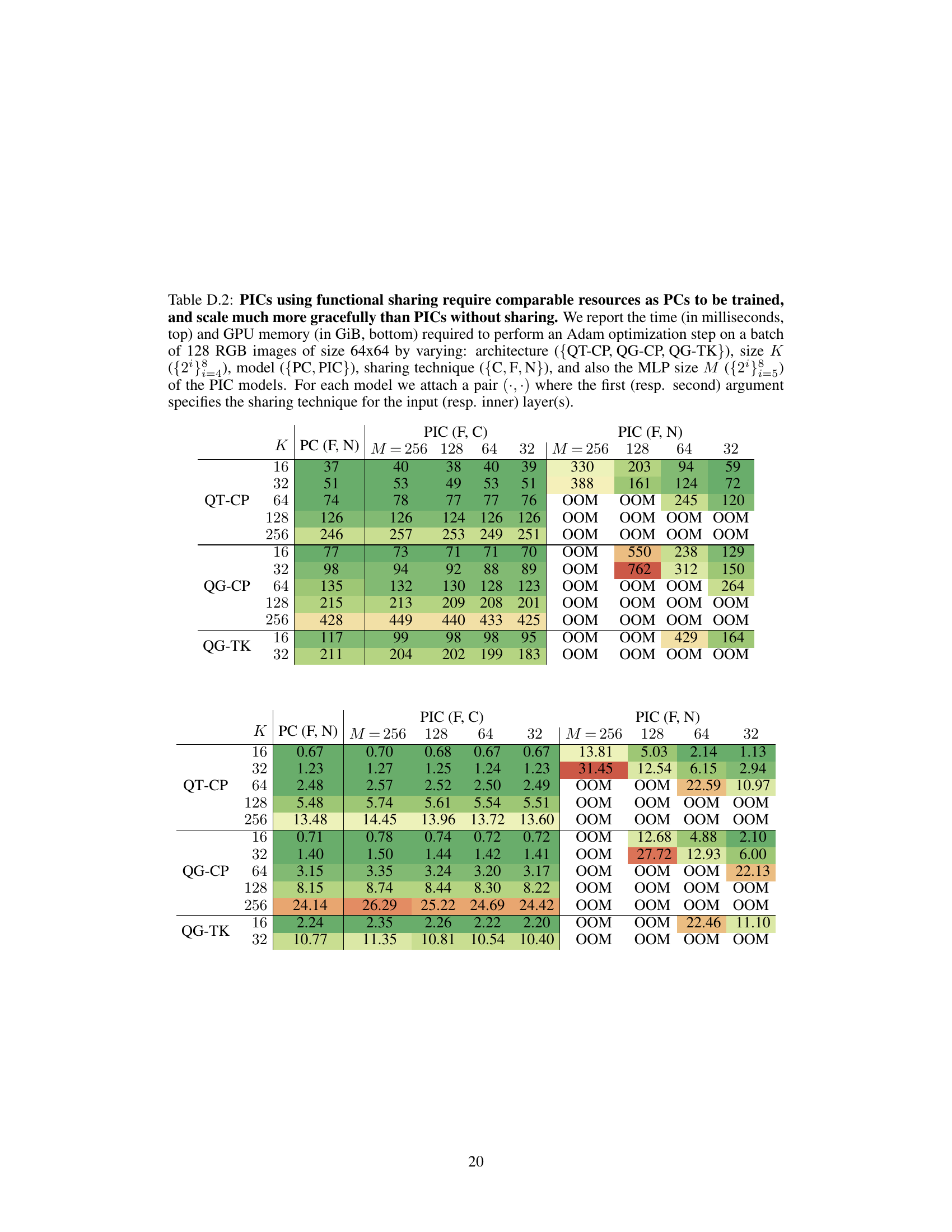

This figure compares the GPU memory and time required for an optimization step for PCs and PICs with and without functional sharing. It shows that PICs with functional sharing use comparable resources to PCs, while those without functional sharing require significantly more resources. The figure also displays the number of trainable parameters for both PCs and PICs, demonstrating that PICs with functional sharing have up to 99% fewer parameters. The experiment uses a batch of 128 64x64 RGB images and the Adam optimizer.

More on tables

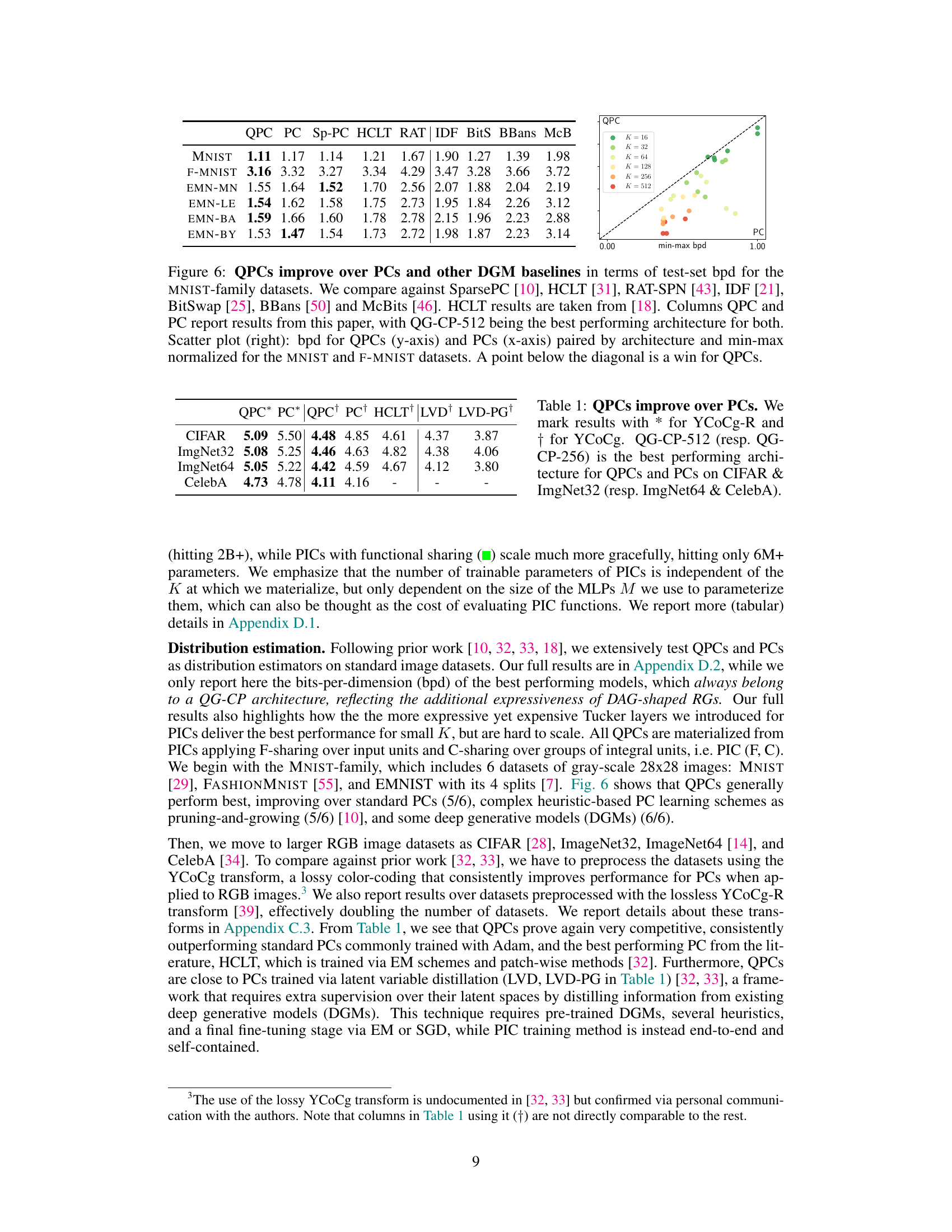

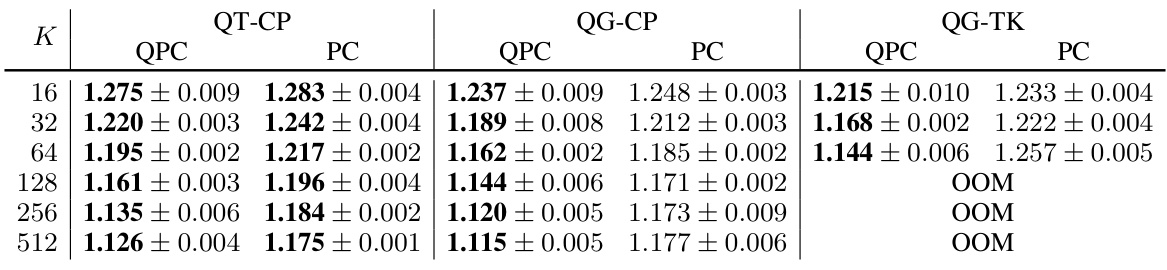

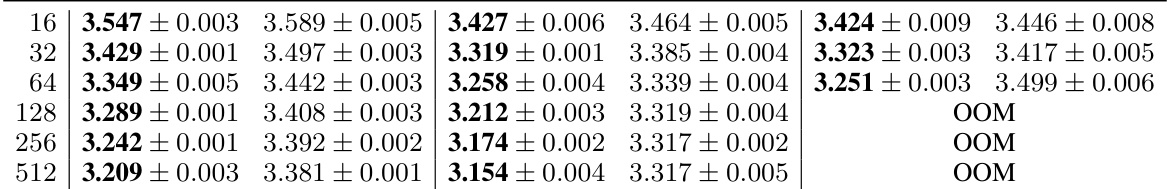

This table compares the test-set bits-per-dimension (bpd) for different models on MNIST-family datasets (MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, EMNIST). It shows that QPCs (Quadrature Probabilistic Circuits) generally outperform other models, including various Probabilistic Circuits (PCs) and Deep Generative Models (DGMs). The best performing QPC architecture is highlighted.

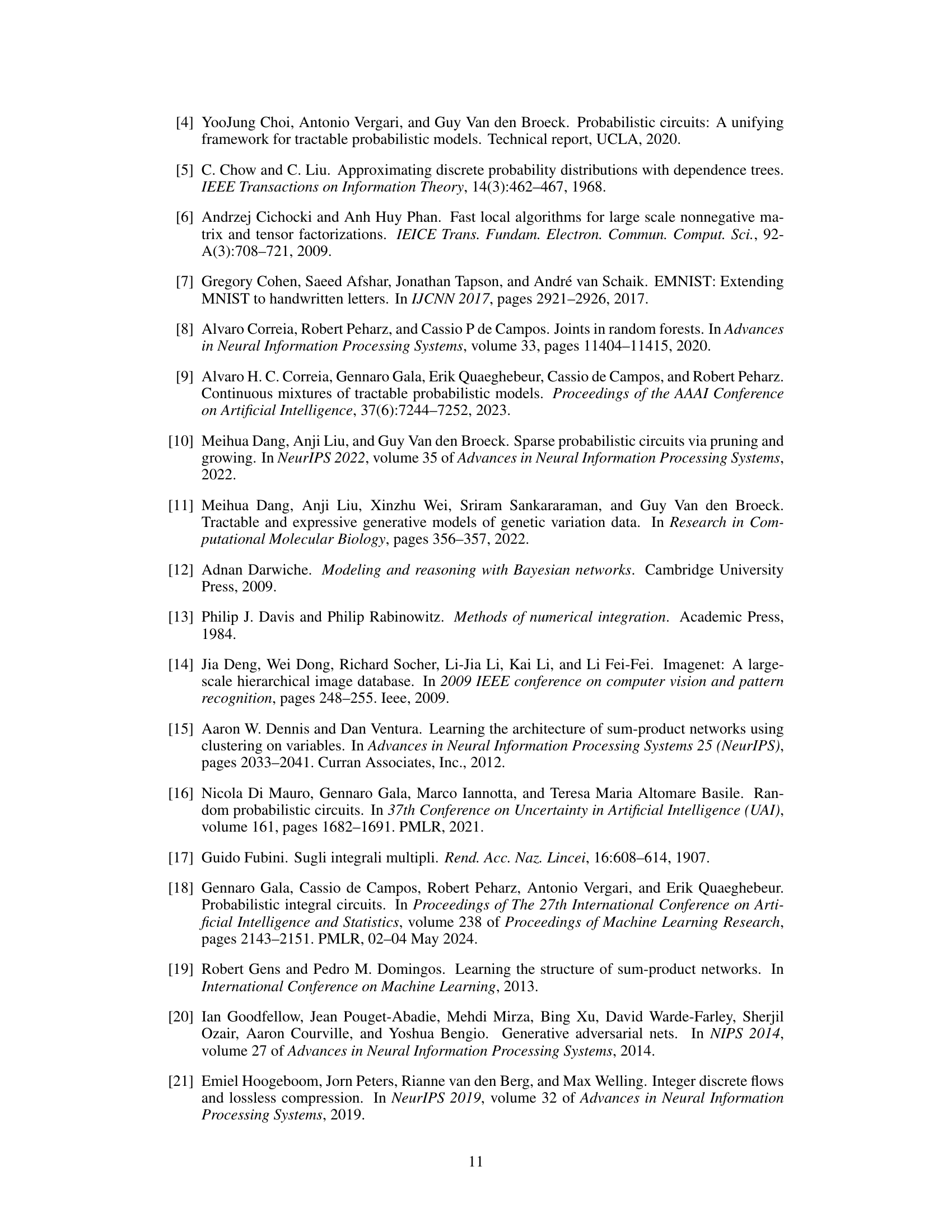

This table compares the performance of QPCs and PCs on various image datasets (CIFAR, ImageNet32, ImageNet64, and CelebA). The results show that QPCs generally outperform PCs in terms of bits per dimension (bpd), indicating better model efficiency. Different preprocessing methods (YCoCg and YCoCg-R) are used for some datasets, affecting the bpd values and are indicated by asterisks and daggers respectively. The best performing QPC architecture for each dataset is also specified.

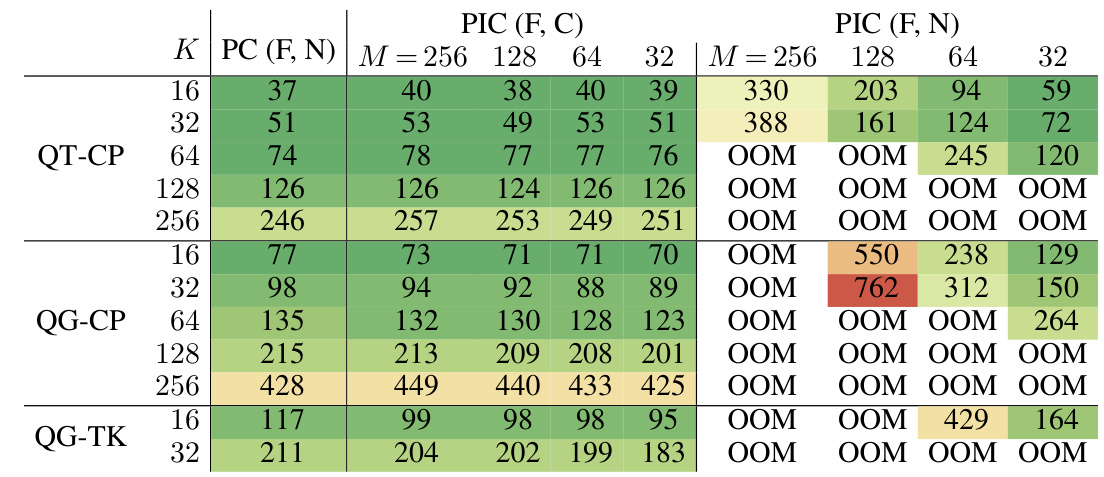

This table compares the training time and GPU memory usage for Probabilistic Integral Circuits (PICs) and Probabilistic Circuits (PCs) with different architectures, sizes, and sharing techniques. It shows the impact of functional sharing on resource utilization during training, indicating that functional sharing in PICs can reduce the required resources to levels comparable to those needed for PCs.

This table presents the results of an experiment comparing the training time and GPU memory usage of Probabilistic Integral Circuits (PICs) with and without functional sharing, and standard PCs. Different architectures (QT-CP, QG-CP, QG-TK), integration points (K), and sharing techniques (F, C, N) are varied to assess their impact on resource consumption. The results show the computational cost of training different configurations of PICs compared to standard PCs.

This table presents the results of experiments comparing the training time and GPU memory usage of PCs and PICs with different architectures (QT-CP, QG-CP, QG-TK), quadrature points (K), and functional sharing techniques (F, C, N). The table shows how functional sharing in PICs allows for scaling to larger models compared to PCs and PICs without functional sharing.

This table presents the results of an experiment comparing the training time and GPU memory usage of Probabilistic Integral Circuits (PICs) and Probabilistic Circuits (PCs) with various configurations. The experiment varied the architecture (QT-CP, QG-CP, QG-TK), the number of quadrature points (K), the model type (PC or PIC), and the type of functional sharing used (C, F, N). The results demonstrate the impact of each configuration on computational resources.

This table presents the results of experiments comparing the time and GPU memory required for an Adam optimization step using different model configurations. The configurations vary across several factors: the type of region graph (QT-CP, QG-CP, QG-TK), the size of K (which affects the number of quadrature points), the type of model (PC or PIC), and the sharing techniques used (C, F, N). For each model, a pair (·,·) is provided to specify the sharing technique applied to the input and inner layers. The top part of the table displays the time, and the bottom displays the GPU memory usage.

This table compares the training time and GPU memory usage for PCs and PICs with different architectures, K values, and functional sharing techniques. It shows that functional sharing in PICs allows scaling to larger models without significant increase in resource consumption.

This table compares the performance of Probabilistic Circuits (PCs) with and without a shared input layer on MNIST-family datasets. Three different architectures are used (QT-CP-512, QG-CP-512, QG-TK-64). The results are measured in bits-per-dimension (bpd), showing the impact of the shared input layer on model performance for different datasets within the MNIST family.

This table compares the performance of Probabilistic Circuits (PCs) with and without a shared input layer on the MNIST-family datasets. Three different architectures (QT-CP-512, QG-CP-512, and QG-TK-64) are used in the comparison. The bits-per-dimension (bpd) metric is used to evaluate the performance, providing a measure of the model’s ability to represent the data efficiently. The results show whether having a shared input layer significantly impacts performance.

This table compares the performance of QPCs and PCs on MNIST and FashionMNIST datasets. The QPCs consistently outperform the PCs across different numbers of quadrature points (K). The QPCs used F-sharing for input units and C-sharing for integral units, while the PCs used no parameter sharing. The results are averaged over 5 runs.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of QPCs and PCs as density estimators on various image datasets. It shows the bits-per-dimension (bpd) for different architectures (QT-CP, QG-CP, QG-TK) and sizes (K) of the models. The results highlight the consistent improvement of QPCs over PCs across different datasets and model configurations.

This table compares the performance of QPCs and PCs on several image datasets, showing the bits-per-dimension (bpd) for various architectures. It highlights that QPCs generally outperform PCs on these tasks, demonstrating the effectiveness of using QPCs materialized from PICs.

Full paper#