↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional continuous Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) rely on integer-order or single fractional-order differential equations to model graph dynamics. However, these models struggle to capture complex dynamics present in real-world scenarios. This limitation motivates researchers to explore more sophisticated mathematical tools to model these dynamics.

The paper introduces DRAGON, a novel GNN framework that addresses this limitation by incorporating distributed-order fractional calculus. This framework allows for a flexible and learnable superposition of multiple derivative orders, leading to a significant improvement in capturing complex dynamics. DRAGON demonstrates superior performance compared to existing continuous GNNs in a wide range of graph learning tasks. Its interpretation through the lens of non-Markovian graph random walks further enhances understanding.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it significantly advances the field of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) by introducing a novel framework, DRAGON, that uses distributed-order fractional calculus to model complex graph dynamics. This approach offers enhanced flexibility and superior performance compared to existing continuous GNN models. It also opens new avenues for research in modeling complex real-world phenomena that involve intricate temporal dependencies. The theoretical insights provided, such as the non-Markovian graph random walk interpretation, contribute to a deeper understanding of GNNs’ capabilities. The code release further enhances its impact by making the framework easily accessible to other researchers.

Visual Insights#

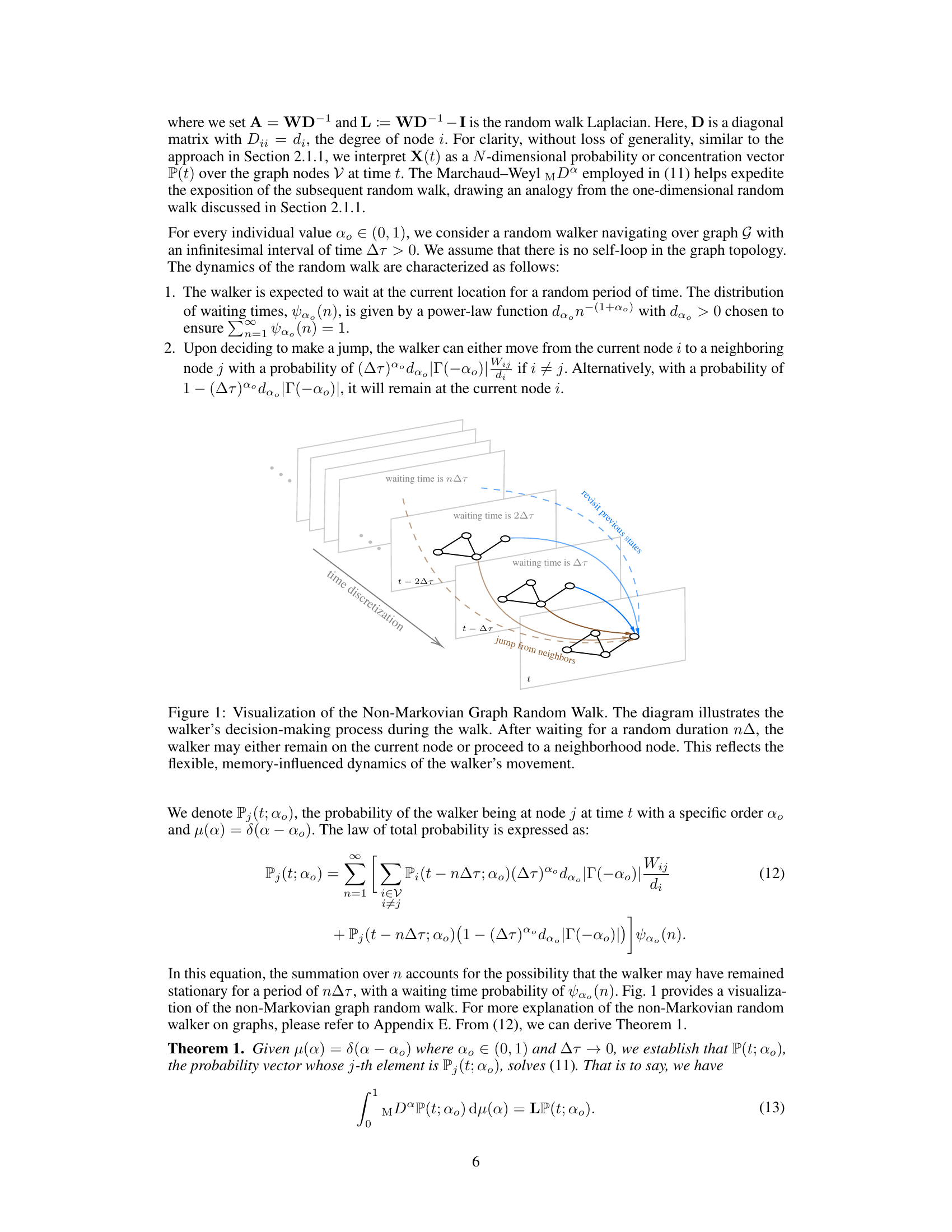

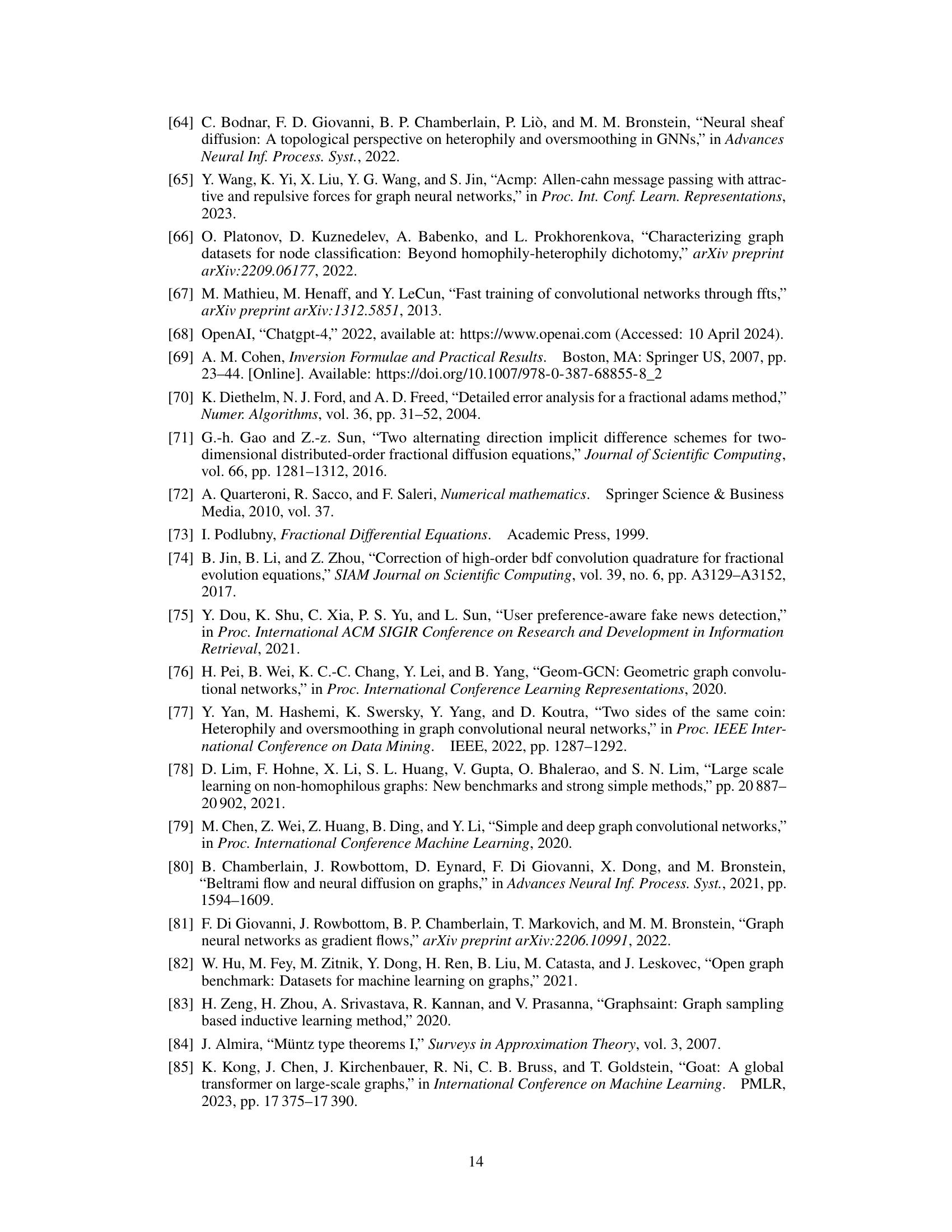

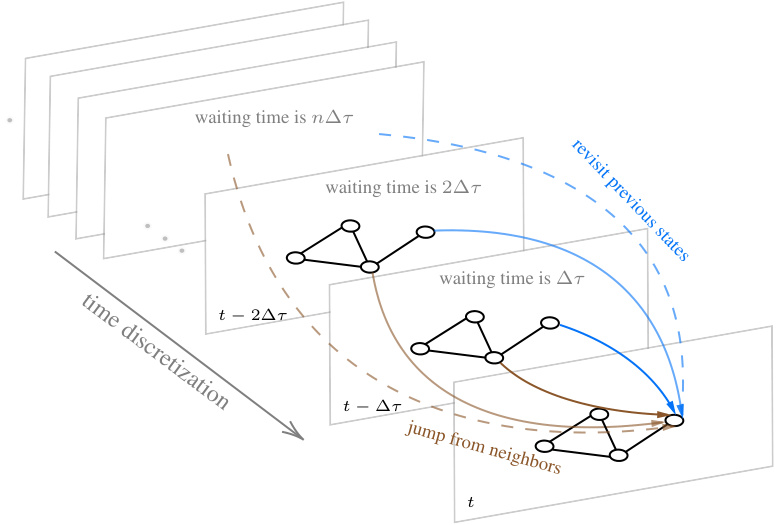

This figure visualizes the non-Markovian graph random walk process. It shows a walker moving across a graph over time. At each time step, the walker has a random waiting time before deciding to either stay at its current node or move to a neighboring node. The waiting times follow a power law distribution, and the walker’s decision incorporates past movements, showcasing the process’s memory effect and non-Markovian nature.

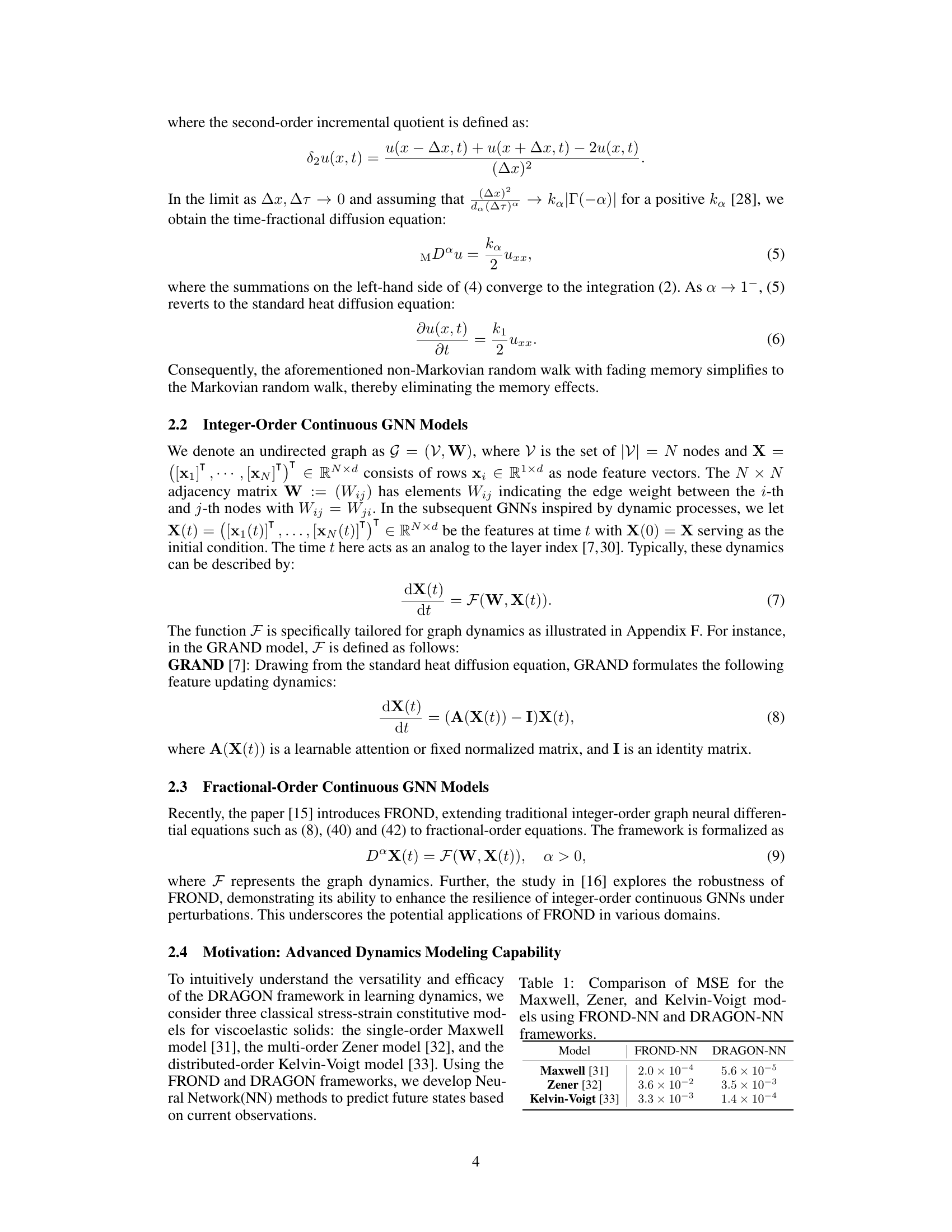

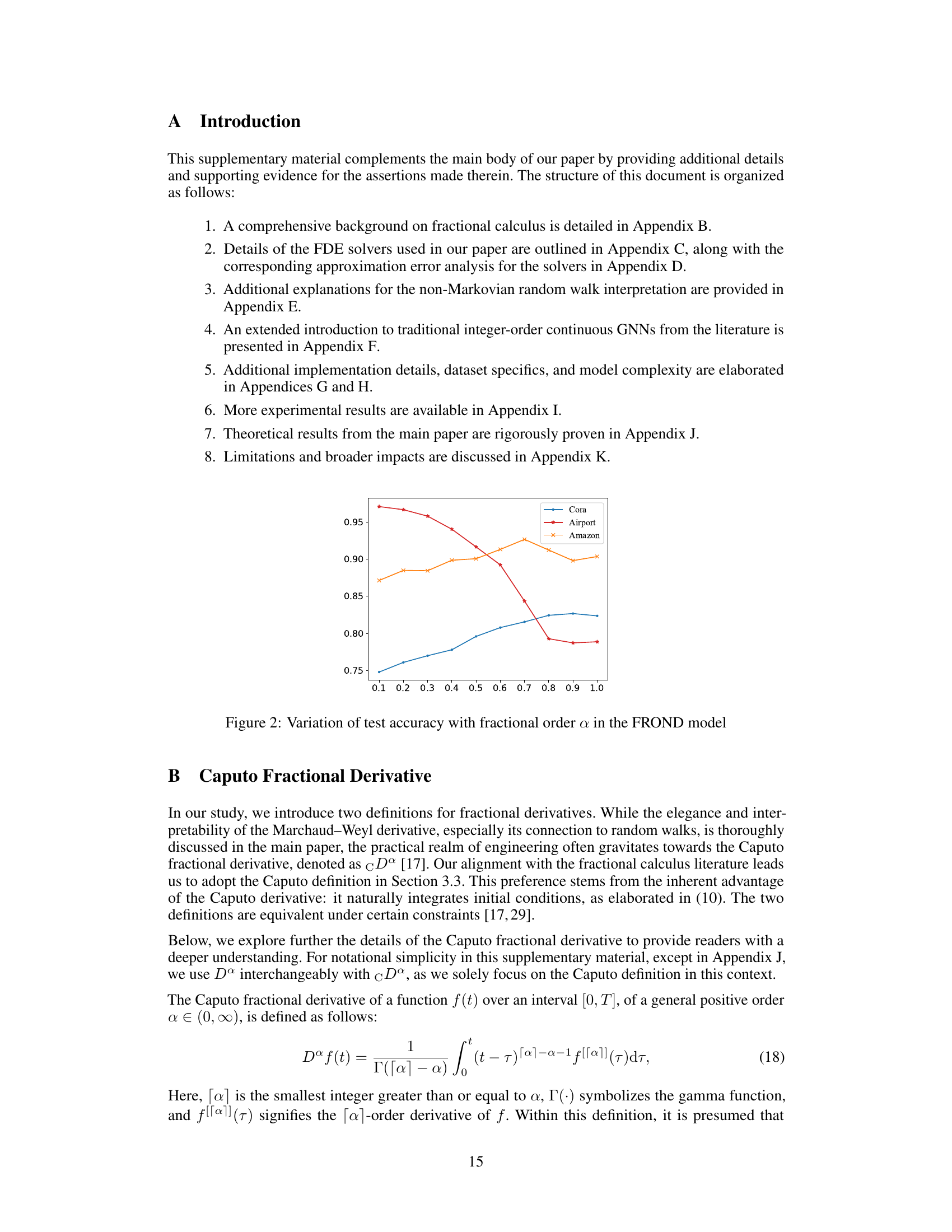

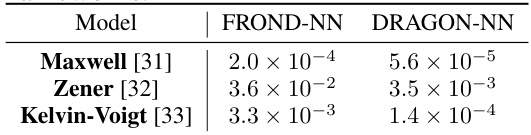

This table compares the Mean Squared Error (MSE) achieved by two different neural network models (FROND-NN and DRAGON-NN) when fitting three different viscoelastic models (Maxwell, Zener, and Kelvin-Voigt). The results show that the DRAGON-NN model consistently achieves a lower MSE than the FROND-NN model, indicating improved accuracy in capturing the dynamics of these viscoelastic systems.

In-depth insights#

DRAGON: A New GNN#

The heading “DRAGON: A New GNN” suggests a novel Graph Neural Network (GNN) architecture. The name evokes a powerful, potentially complex, and potentially scalable system. A key aspect to explore would be what makes DRAGON “new.” This likely involves novelty in the GNN’s architecture, training methodology, or application, perhaps utilizing a unique message passing mechanism or incorporating elements not typically found in traditional GNNs. Further, the acronym DRAGON might hint at specific features—distributed processing, robust operation, advanced dynamics, or generalized applicability are all possible interpretations. Understanding the technical details underlying the “new” aspects of DRAGON would reveal its potential advantages in terms of expressiveness, efficiency, or applicability to specific graph-related tasks. Finally, investigation of the architecture’s performance compared to existing GNNs is critical to determine its true impact and contributions to the field.

Fractional Calculus in GNNs#

The application of fractional calculus to Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) represents a significant advancement, offering the potential to enhance expressiveness and model complex dynamics. Traditional GNNs often rely on integer-order differential equations, limiting their ability to capture long-range dependencies and non-Markovian processes inherent in many real-world graph datasets. Fractional calculus, by incorporating memory effects and non-local interactions, provides a more powerful tool to model these intricate dynamics. This allows GNNs to better learn from graphs with complex temporal dependencies and long-range correlations. However, the increased complexity of fractional-order systems also introduces challenges. Developing efficient and robust numerical solvers is crucial for practical implementation. Moreover, theoretical analysis and the interpretation of learned fractional-order parameters remain areas of active research. Despite these challenges, the theoretical framework of fractional calculus provides a rich foundation for the development of more sophisticated and powerful GNN models with the ability to handle diverse and complex graph-structured data effectively.

Non-Markovian Dynamics#

Non-Markovian dynamics challenges the fundamental Markov assumption that the future state depends solely on the present. In the context of graph neural networks (GNNs), this translates to feature evolution not being solely determined by immediate neighbors’ information. The core concept is memory: past states significantly influence current feature updates. This contrasts with Markovian GNNs, where each layer’s update only uses immediate information. Non-Markovian models are crucial for capturing long-range dependencies and complex temporal dynamics, reflecting the reality of many real-world systems. Fractional calculus provides a powerful mathematical framework for modeling these non-local effects by introducing fractional-order derivatives, which inherently capture memory. The ability of a GNN to learn a probability distribution over fractional derivative orders allows for a flexible modeling of various memory effects, surpassing limitations of fixed-order models.

Empirical Evaluations#

A robust ‘Empirical Evaluations’ section is crucial for validating the claims of a research paper. It should present a comprehensive and methodical approach to testing the proposed methodology. This involves selecting relevant and diverse datasets, clearly defining evaluation metrics (precision, recall, F1-score, AUC, etc.), and comparing the results against strong baseline models. The selection of datasets should reflect the intended application and address potential biases. For instance, if the model is designed for graph classification, datasets with different characteristics (homophily, heterophily, graph size, etc.) should be included. Rigorous statistical analysis, such as hypothesis testing and confidence intervals, should be performed to ensure the observed improvements are statistically significant. Finally, thorough error analysis helps assess robustness and potential weaknesses, identifying any limitations and areas for future work. A well-written empirical evaluation section builds confidence in the validity and generalizability of the proposed methods, enhancing the impact and credibility of the research.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending DRAGON’s applicability beyond graph neural networks is crucial, potentially adapting the framework for other data structures or machine learning tasks. Investigating the theoretical properties of DRAGON more deeply, such as its capacity for approximating diverse probability distributions and its robustness under various conditions, would enhance understanding. Developing more efficient numerical solvers tailored to DRAGON’s distributed-order fractional differential equations is vital for improved scalability and computational performance. Finally, applying DRAGON to real-world, large-scale datasets across diverse domains, particularly those with complex temporal dynamics and non-Markovian behaviors, could showcase its true potential and pave the way for practical applications and impact.

More visual insights#

More on tables

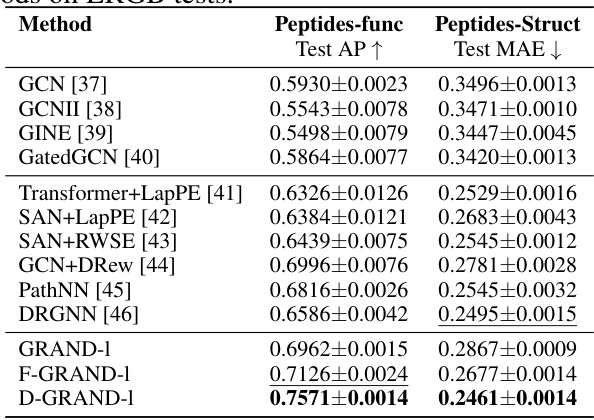

This table presents the numerical results obtained for various graph neural network methods on the Long Range Graph Benchmark (LRGB) tests, specifically focusing on the Peptides dataset. It compares the performance of several methods, including GCN, GCNII, GINE, GatedGCN, Transformer+LapPE, SAN+LapPE, SAN+RWSE, GCN+DRew, PathNN, DRGNN, GRAND-1, F-GRAND-1, and D-GRAND-1, across two tasks: peptides-func (graph classification using Average Precision (AP) as the metric) and peptides-struct (graph regression using Mean Absolute Error (MAE) as the metric). The results highlight the superior performance of the DRAGON-based methods (GRAND-1, F-GRAND-1, and D-GRAND-1) in capturing long-range dependencies within the graph data, demonstrating significant improvements in both AP and MAE compared to the baseline methods.

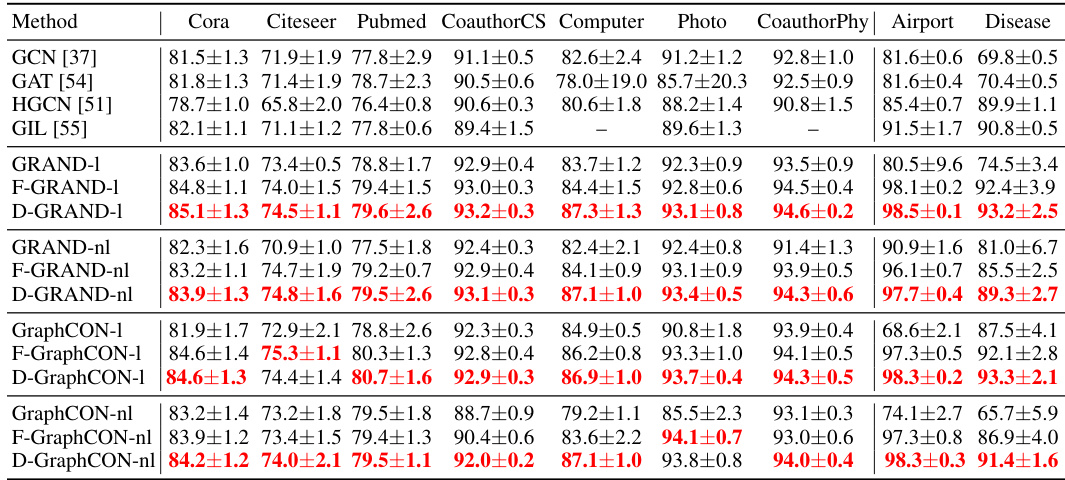

This table presents the performance of various continuous Graph Neural Network (GNN) models on node classification tasks across multiple datasets. The datasets represent different graph types, including citation networks (Cora, Citeseer, Pubmed), tree-structured datasets (Disease, Airport), and co-authorship and co-purchasing networks (CoauthorCS, Computer, Photo, CoauthorPhy). The results show the classification accuracy (in percentage) achieved by each model on each dataset, with the best performance within each GNN family (GRAND, F-GRAND, D-GRAND, GraphCON, F-GraphCON, D-GraphCON) highlighted in red. This allows for a direct comparison of the effectiveness of different continuous GNN models and the impact of the DRAGON framework on their performance.

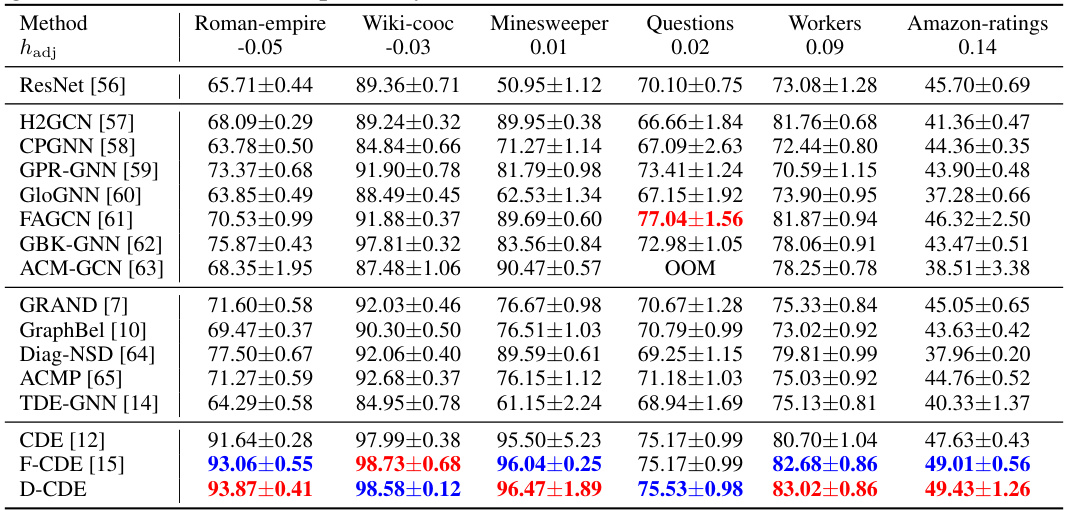

This table presents the results of node classification experiments conducted on six heterophilic graph datasets. The datasets are characterized by a low adjusted homophily, indicating a higher degree of heterophily. The results show the performance of various methods, including the proposed D-CDE model (a continuous GNN enhanced with the DRAGON framework), and compare them to other continuous GNN models (e.g., GRAND, GraphCON, CDE, F-CDE) and integer-order GNN models (e.g., GCN, GAT). The best and second-best performing models for each dataset and metric are highlighted for easier comparison and interpretation.

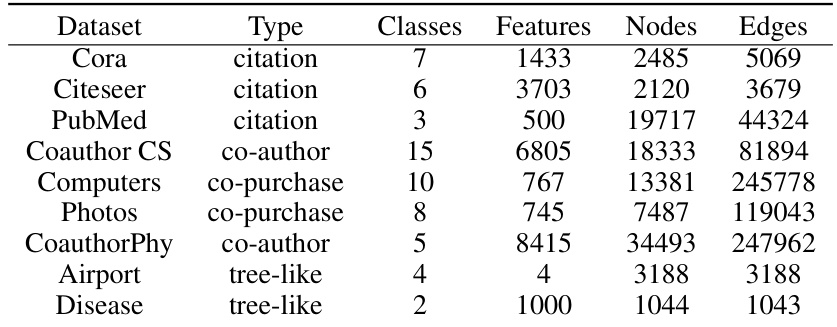

This table provides details on the datasets used in the node classification experiments reported in Table 3 of the paper. For each dataset, it lists the type of data (citation, co-author, co-purchase, or tree-like), the number of classes, the number of features, the number of nodes, and the number of edges. These statistics help to characterize the size and complexity of the datasets used in the evaluation of the proposed DRAGON framework and its comparison to existing continuous GNN models.

This table presents the results of node classification experiments conducted on six heterophilic graph datasets. The performance of various methods is compared, with the best and second-best results for each dataset highlighted. The datasets include Roman-empire, Wiki-cooc, Minesweeper, Questions, Workers, and Amazon-ratings, each characterized by a low adjusted homophily (hadj), indicating a high degree of heterophily.

This table provides a detailed breakdown of the datasets used for the experiments presented in Table 10 of the paper. It includes the number of graphs (total and fake), the total number of nodes and edges, and the average number of nodes per graph for both the Politifact (POL) and Gossipcop (GOS) datasets. This information is crucial for understanding the scale and complexity of the datasets used in the long-range graph benchmark experiments.

This table shows the inference time in milliseconds (ms) for different continuous GNN models on the Cora dataset. The integral time T is set to 10 and the step size is 1. Three groups of models are presented: DRAGON models, FROND models, and the original continuous GNN models (GRAND, GraphCON, and CDE). For each model, two versions are tested: linear and non-linear. The table allows for a comparison of the computational efficiency of different models in terms of inference time.

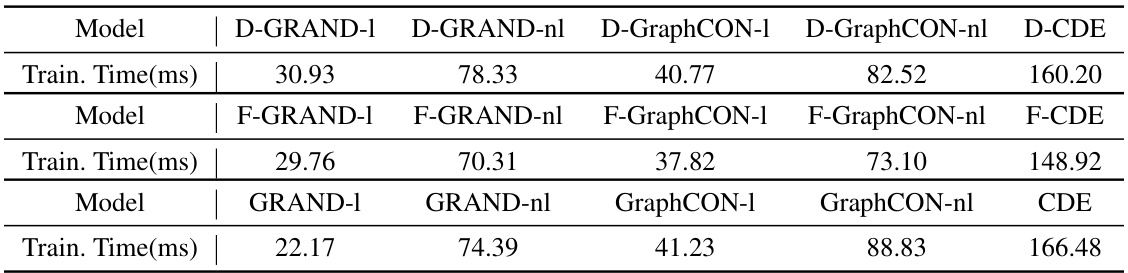

This table presents the training time per epoch for various continuous Graph Neural Network (GNN) models on the Cora dataset. The models are categorized into three groups: DRAGON, FROND, and baseline models. Each group includes linear and nonlinear versions of several models (GRAND, GraphCON, CDE). The integral time (T) is set to 10, and the step size is 1. The results show the training time in milliseconds (ms) for each model.

This table presents the results of graph classification experiments conducted on the FakeNews-Net dataset using various methods, including GraphSage, GCN, GAT, GRAND-1, F-GRAND-1, and D-GRAND-1. The dataset includes profile, word2vec, and BERT features. The table showcases the performance (Average Precision) of each method on both the POL and GOS subsets of the FakeNews-Net dataset, highlighting the superior performance of the DRAGON-enhanced models (F-GRAND-1 and D-GRAND-1).

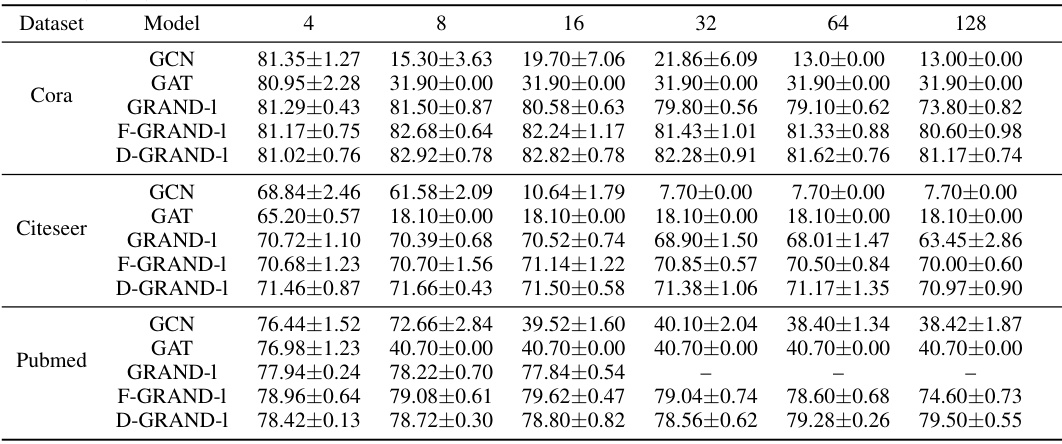

This table presents the results of an experiment designed to evaluate the oversmoothing mitigation capabilities of different models across various graph datasets. The experiment used fixed data splitting (without using the largest connected component) and varied the number of layers (represented by integration time). The models compared include GCN, GAT, GRAND-1, F-GRAND-1, and D-GRAND-1. The results are shown as the accuracy with standard deviation. The ‘-’ indicates cases where the numerical solver failed to converge.

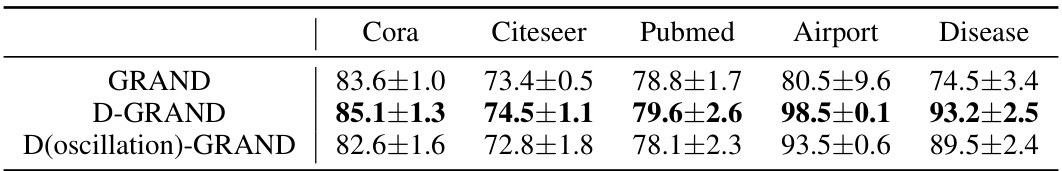

This table presents the results of node classification experiments conducted on three heterophilic graph datasets (Texas, Wisconsin, Cornell). The results compare the performance of various continuous graph neural network (GNN) models, including several baselines and the proposed D-GRAND and D-GREAD models. The table highlights the improved performance of the DRAGON framework integrated GNNs, showcasing their effectiveness in handling heterophilic datasets, particularly D-GREAD which achieves the best performance on two out of three datasets.

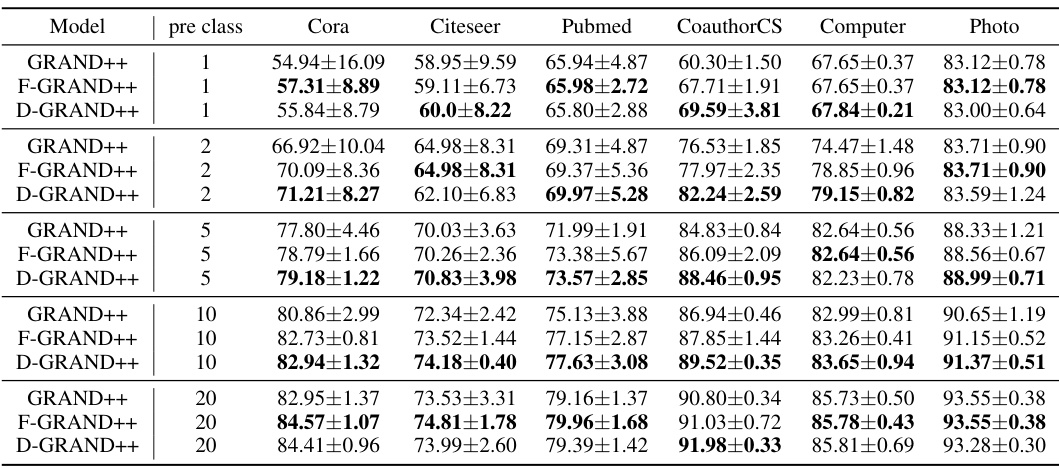

This table presents the node classification results achieved by different GNN models under limited-label conditions. It compares the performance of the standard GRAND++, the FROND-enhanced F-GRAND++, and the DRAGON-enhanced D-GRAND++ across various datasets (Cora, Citeseer, Pubmed, CoauthorCS, Computer, Photo) and different numbers of pre-training classes (1, 2, 5, 10, 20). The results highlight the superior performance of the DRAGON-enhanced models, demonstrating their effectiveness in handling scenarios with limited labeled data.

This table presents the node classification accuracy results for several continuous Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) on various datasets. The results are shown as percentages, and the best performance within each family of GNNs is highlighted in red. The datasets include citation networks (Cora, Citeseer, Pubmed), tree-structured datasets (Disease, Airport), and co-authorship/co-purchasing networks (CoauthorCS, Computer, Photo, CoauthorPhy). The table provides a comparison of the performance of different continuous GNN models, including those enhanced by the DRAGON framework, under random train-validation-test splits.

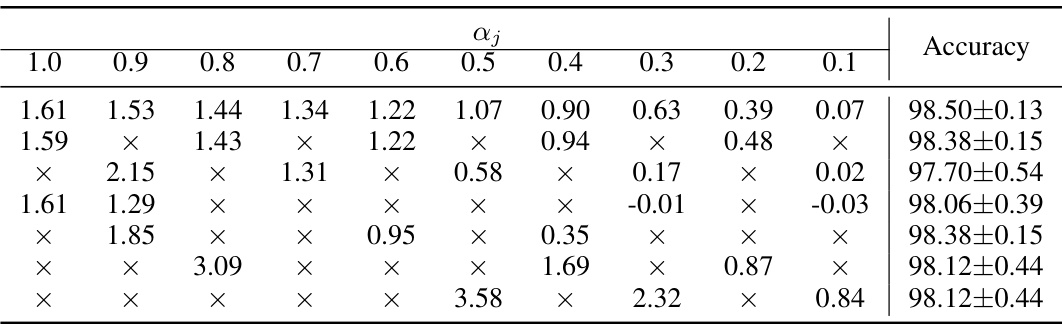

This table displays the learned weights (wj) for each fractional order (αj) in the DRAGON model applied to the Airport dataset. The weights were learned using the distributed-order fractional derivative approach. Each row represents a different set of learned weights, demonstrating the model’s ability to find optimal weights for the combination of fractional orders. The final accuracy achieved for each set of weights is also shown. This table illustrates the robustness of the DRAGON framework’s parameter selection.

This table presents the learned weights (wj) for each fractional order (aj) in the DRAGON framework when applied to the Roman-empire dataset. The weights are learned parameters that determine the contribution of each fractional derivative order to the overall feature update dynamics. Each row represents a different set of learned weights, resulting in a slightly different model accuracy. The ‘X’ indicates that the weight for that specific fractional order was not learned or is zero. The final column shows the corresponding accuracy achieved by the model with that set of weights.

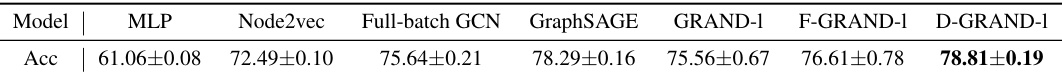

This table presents the results of node classification experiments conducted on the Ogb-products dataset. The results compare the performance of various graph neural network (GNN) models, including a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), Node2vec, a full-batch GCN, GraphSAGE, GRAND-1, F-GRAND-1 (FROND-enhanced GRAND), and D-GRAND-1 (DRAGON-enhanced GRAND). The accuracy (Acc) is reported with standard deviation for each model, demonstrating the effectiveness of the DRAGON framework in enhancing the performance of GNNs on large-scale graph datasets.

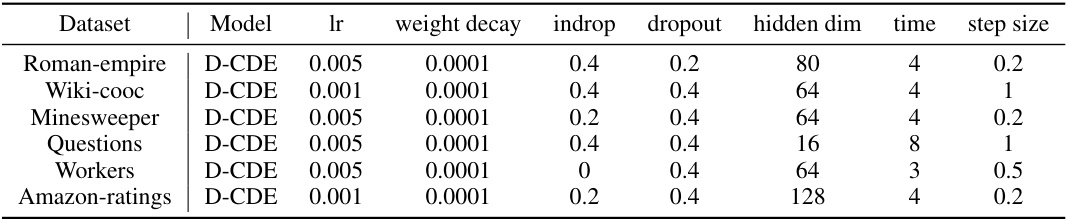

This table lists the hyperparameters used for the D-CDE model in the node classification experiments reported in Table 4 of the paper. The hyperparameters include learning rate (lr), weight decay, input dropout rate, dropout rate, hidden dimension size, integration time, and step size. Each row represents a different dataset and its corresponding hyperparameter settings.

Full paper#