↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

In-context learning (ICL) allows machine learning models to solve new tasks by simply processing a few examples, without retraining. Transformers, known for their impressive ICL capabilities, utilize self-attention mechanisms. However, the role of the activation function, especially softmax, in enabling ICL remains unclear. Prior theoretical analysis often oversimplifies this by using linear attention, missing the key insights of softmax.

This paper focuses on understanding the mechanism behind the success of softmax attention in ICL for regression tasks. The authors show that softmax attention, during pretraining, learns to adapt its attention window size and direction. The attention window narrows for smoother functions (higher Lipschitzness) and widens with increased noise or for functions that only change in specific directions. This adaptive behavior is absent in linear attention, confirming the significance of the softmax activation function for efficient ICL.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in transformer models and in-context learning. It provides a novel theoretical understanding of how softmax attention facilitates ICL, challenging existing paradigms, and opening avenues for improved model design and generalization.

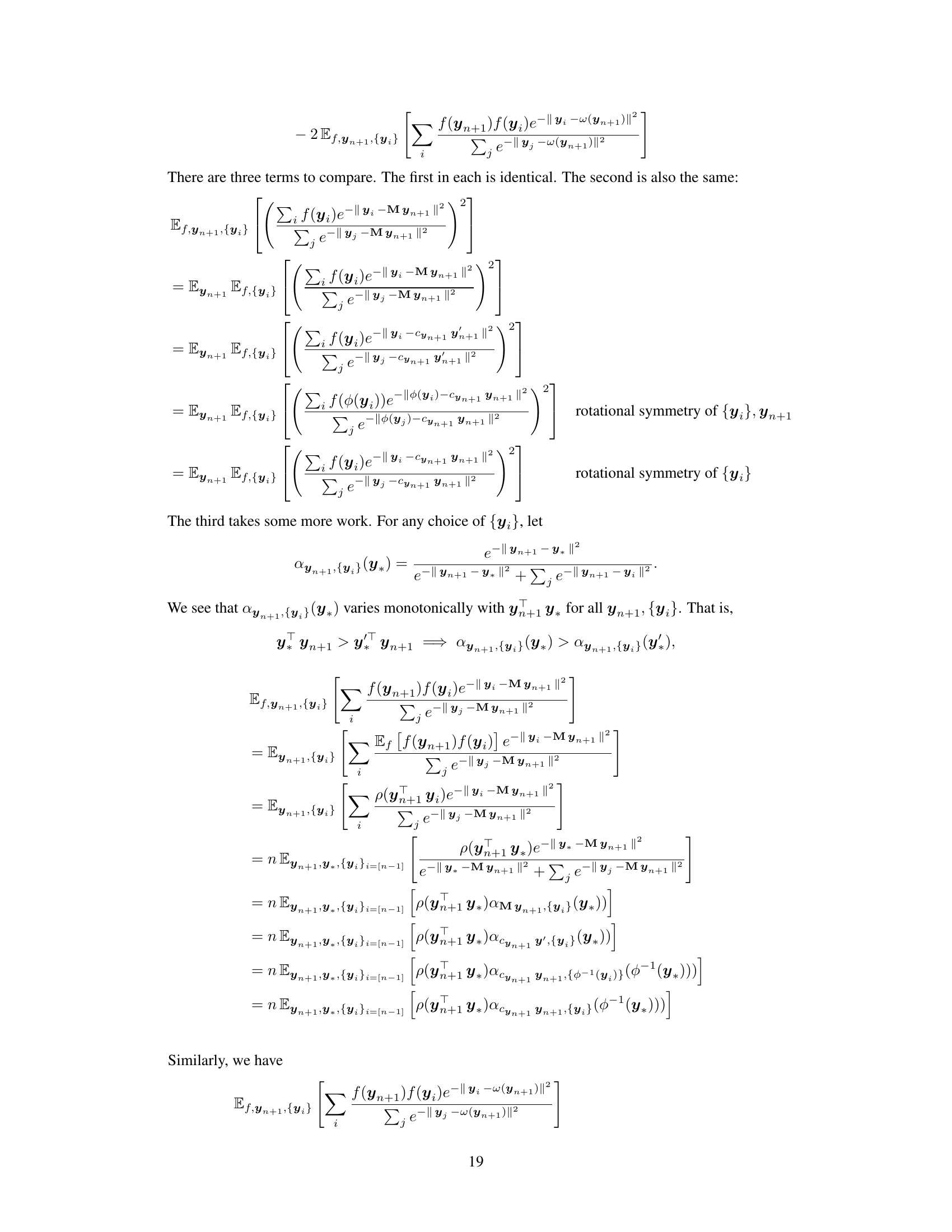

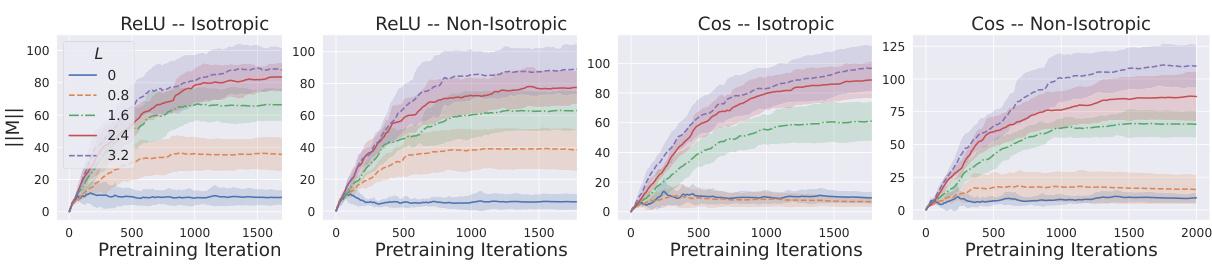

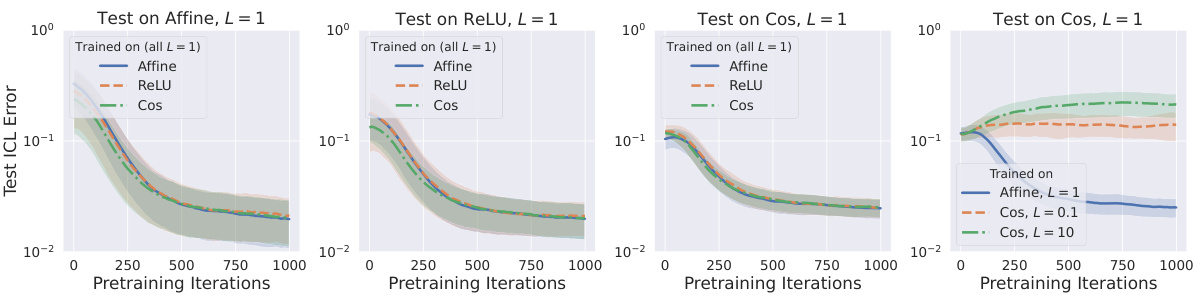

Visual Insights#

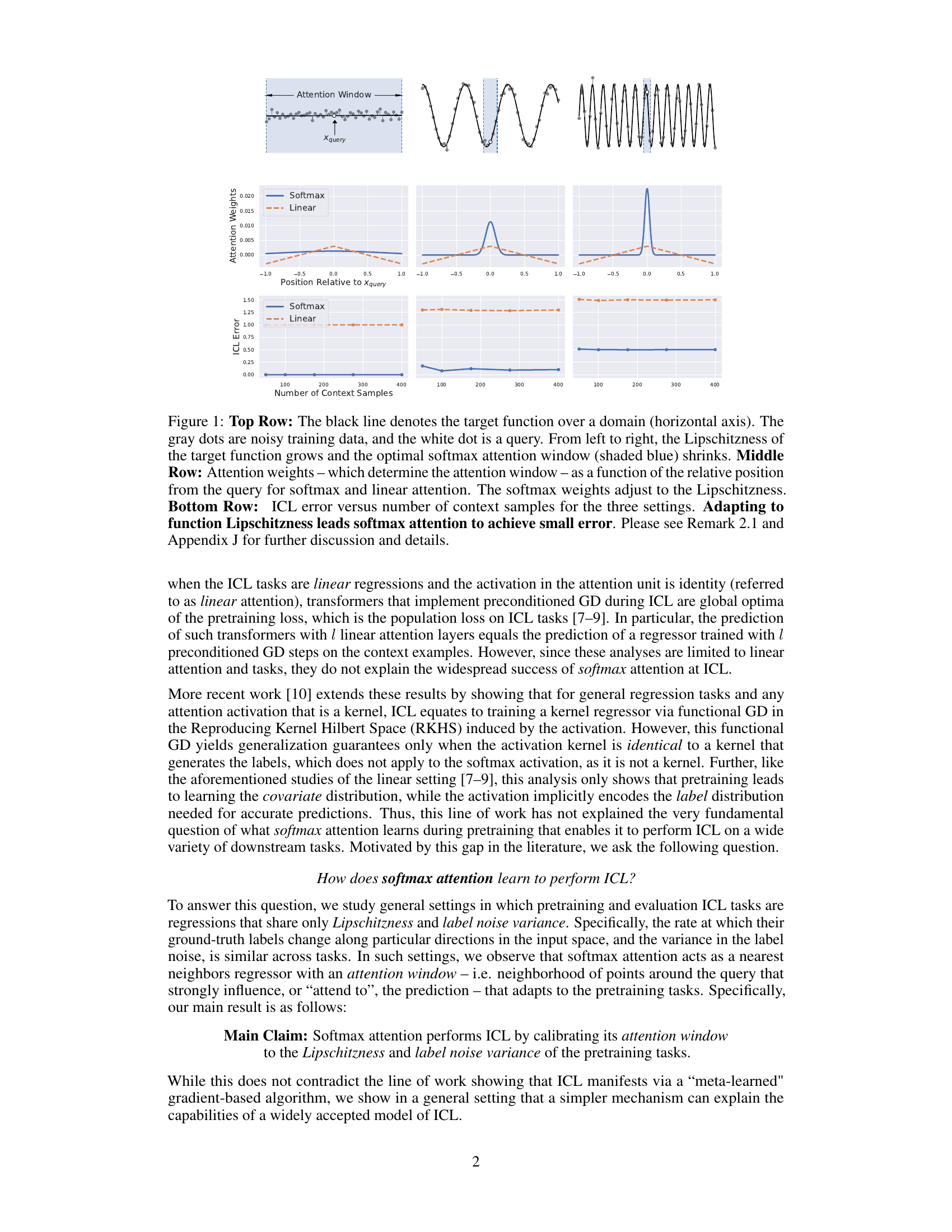

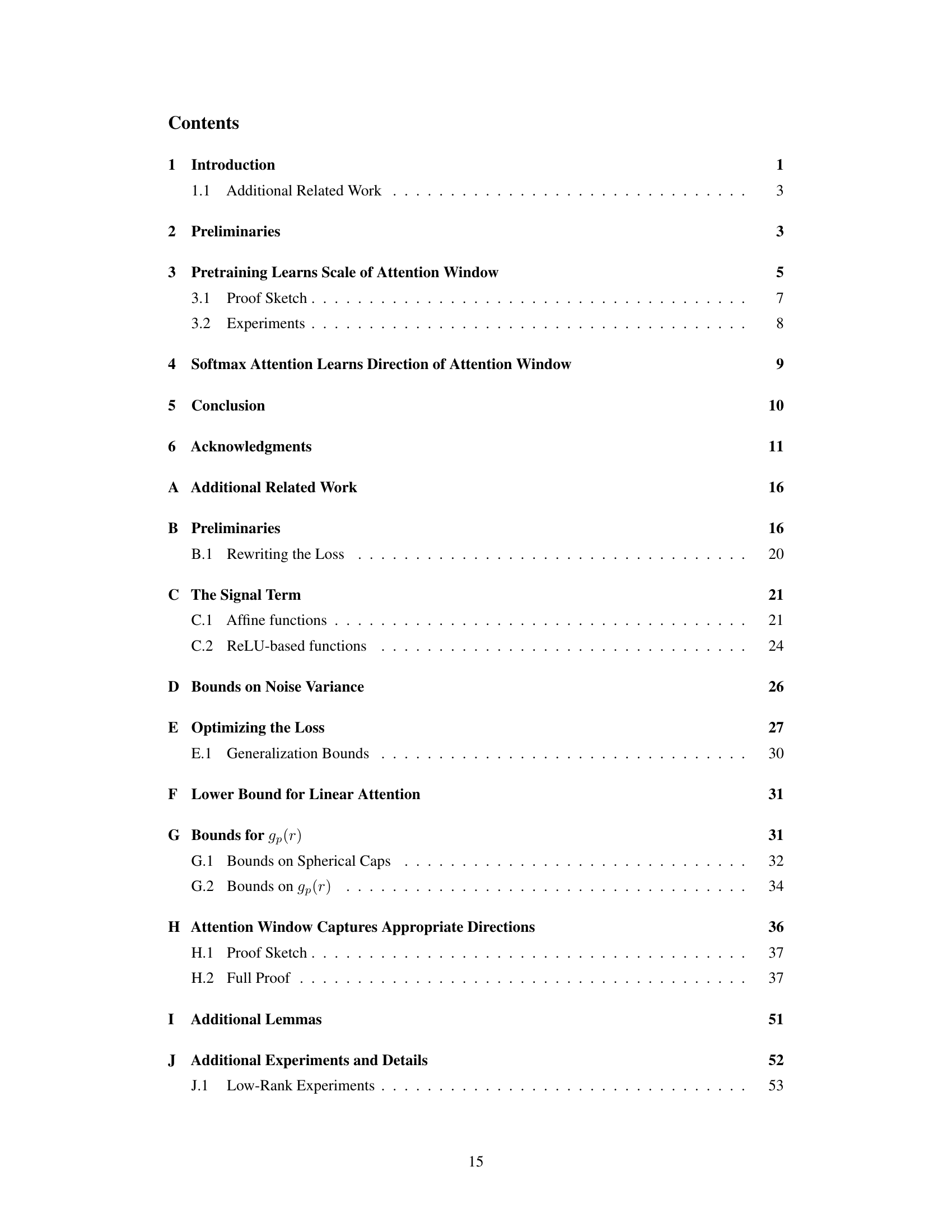

The figure shows how softmax attention adapts to the Lipschitzness of the target function in an in-context learning setting. The top row shows three example functions with varying Lipschitzness. The middle row displays the attention weights assigned by softmax and linear attention mechanisms, revealing how softmax attention dynamically adjusts its window size based on Lipschitzness. The bottom row illustrates how the In-context learning (ICL) error varies with the number of context samples for different settings, highlighting the superior performance of softmax attention when adapting to Lipschitzness.

In-depth insights#

Softmax Attention#

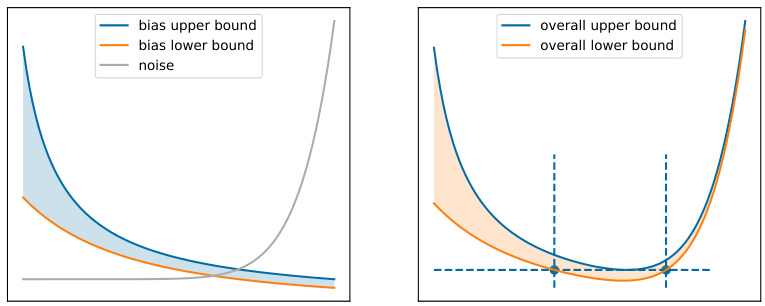

The concept of “Softmax Attention” within the context of transformer models is explored in the provided research paper. The authors delve into the critical role of softmax activation within the attention mechanism, emphasizing its ability to dynamically adapt to the characteristics of the underlying data and tasks. Softmax attention’s capacity to adjust its attention window based on function Lipschitzness and noise levels is a key finding. This adaptive behavior is contrasted with linear attention mechanisms, highlighting the superior performance of softmax in in-context learning settings. The theoretical analysis is supported by experimental validation, showcasing how the attention window scales inversely with Lipschitzness and directly with label noise during the pretraining phase. This adaptive behavior suggests a more nuanced understanding of how pretrained transformers achieve their remarkable in-context learning capabilities than previously established by alternative theories focusing solely on gradient descent.

ICL Mechanism#

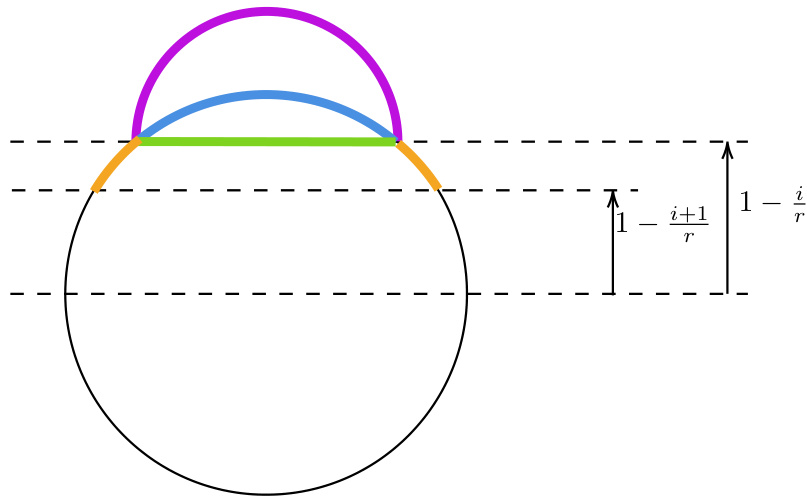

The paper investigates the in-context learning (ICL) mechanism in transformer models, focusing on the role of softmax attention. Softmax attention’s ability to adapt to the function’s Lipschitzness (smoothness) and noise levels is crucial for ICL’s success. The analysis reveals that the attention unit learns an attention window, effectively acting as a nearest-neighbor predictor. This window’s size dynamically adjusts—shrinking with increased Lipschitzness (less noisy functions) and expanding with higher noise levels. The authors also demonstrate that this adaptive behavior is unique to softmax and cannot be replicated by linear attention units. They further explore low-rank linear problems showing that softmax attention learns to project onto the appropriate subspace before making a prediction. The theoretical findings are supported by empirical simulations, providing strong evidence for the importance of softmax in facilitating ICL. The research significantly contributes to our understanding of ICL by going beyond the commonly accepted meta-learning paradigm, offering a simpler yet powerful explanation for the phenomenon. However, further investigation is needed to fully address generalization to more complex function classes beyond the ones studied here.

Lipschitz Adapt#

The concept of “Lipschitz Adapt” in the context of a machine learning model likely refers to the model’s ability to adjust its behavior based on the smoothness of the underlying function it is trying to learn. Lipschitz continuity quantifies function smoothness; a Lipschitz continuous function has a bounded rate of change. A model exhibiting “Lipschitz Adapt” would dynamically alter its internal parameters (e.g., attention mechanisms, network weights) to efficiently handle varying degrees of function smoothness. This is crucial because overly complex models might overfit noisy or highly irregular data while simpler models may struggle to capture intricate patterns. Therefore, adaptive capacity is important for generalizability across different datasets and tasks, which is a key aspect of “Lipschitz Adapt”. The mechanism of this adaptation could involve the network learning to adjust its effective receptive field (e.g., attention window size) or internal regularization strategies. Softmax functions, often used in attention mechanisms, could play a vital role in this adaptive behavior because their output is inherently bounded and smooth, promoting stability and preventing the model from becoming overly sensitive to small changes in input.

Attention Window#

The concept of an ‘Attention Window’ in the context of transformer-based in-context learning is crucial. It represents the dynamic receptive field of the attention mechanism, effectively determining which parts of the input context most influence the prediction for a given query. The size and shape of this window are not fixed but adapt based on characteristics of the pretraining data. Specifically, the paper highlights the importance of softmax activation in enabling this adaptivity, as opposed to simpler linear activations. A smaller attention window is observed in settings with high Lipschitzness (smooth functions) and low noise during pretraining, while a larger window is associated with low Lipschitzness (rougher functions) and high noise. This adaptive behavior is crucial for the model’s ability to generalize to unseen tasks, demonstrating a form of implicit meta-learning. The window’s direction also adapts to underlying low-dimensional structure in the data, indicating a capacity for feature selection and dimensionality reduction. Overall, the study of the attention window provides critical insights into the mechanics of in-context learning, emphasizing the role of adaptive receptive fields and activation functions in enabling generalization and efficient task-solving.

Future ICL#

Future research in in-context learning (ICL) should prioritize understanding the mechanisms underlying attention’s ability to adapt to function Lipschitzness and noise variance. Further investigation is needed to elucidate the role of different activation functions beyond softmax, potentially exploring alternative activation mechanisms capable of efficient ICL. The interaction of attention with other transformer components, especially deeper layers and different model architectures, should also be explored. A key area for future work involves developing more robust theoretical analyses to encompass a wider array of ICL scenarios, not just the linear problems. Moreover, scaling ICL to more complex tasks and datasets while maintaining efficiency is a vital challenge. Finally, investigating the implications of ICL for fairness, bias, and safety is crucial as ICL is increasingly deployed in real-world applications.

More visual insights#

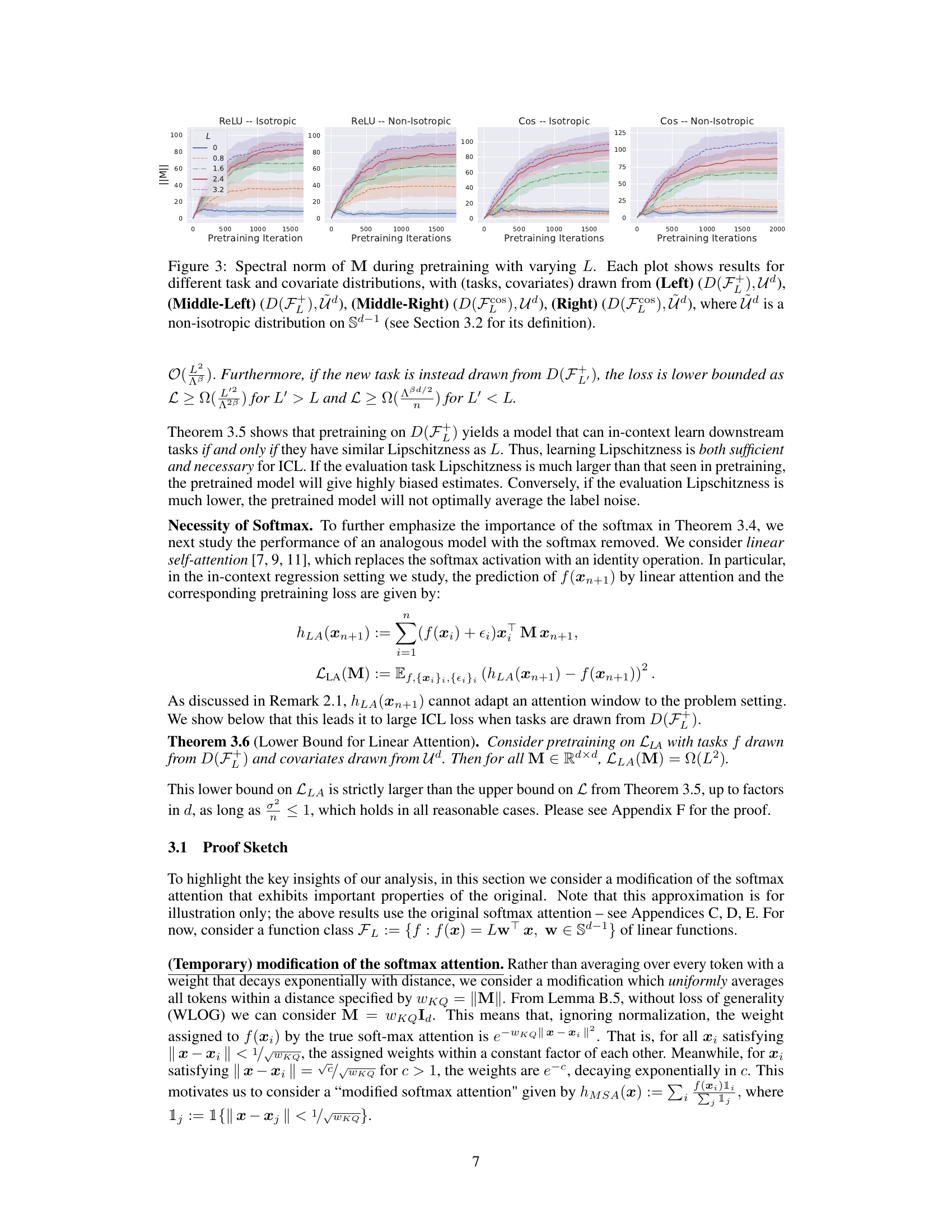

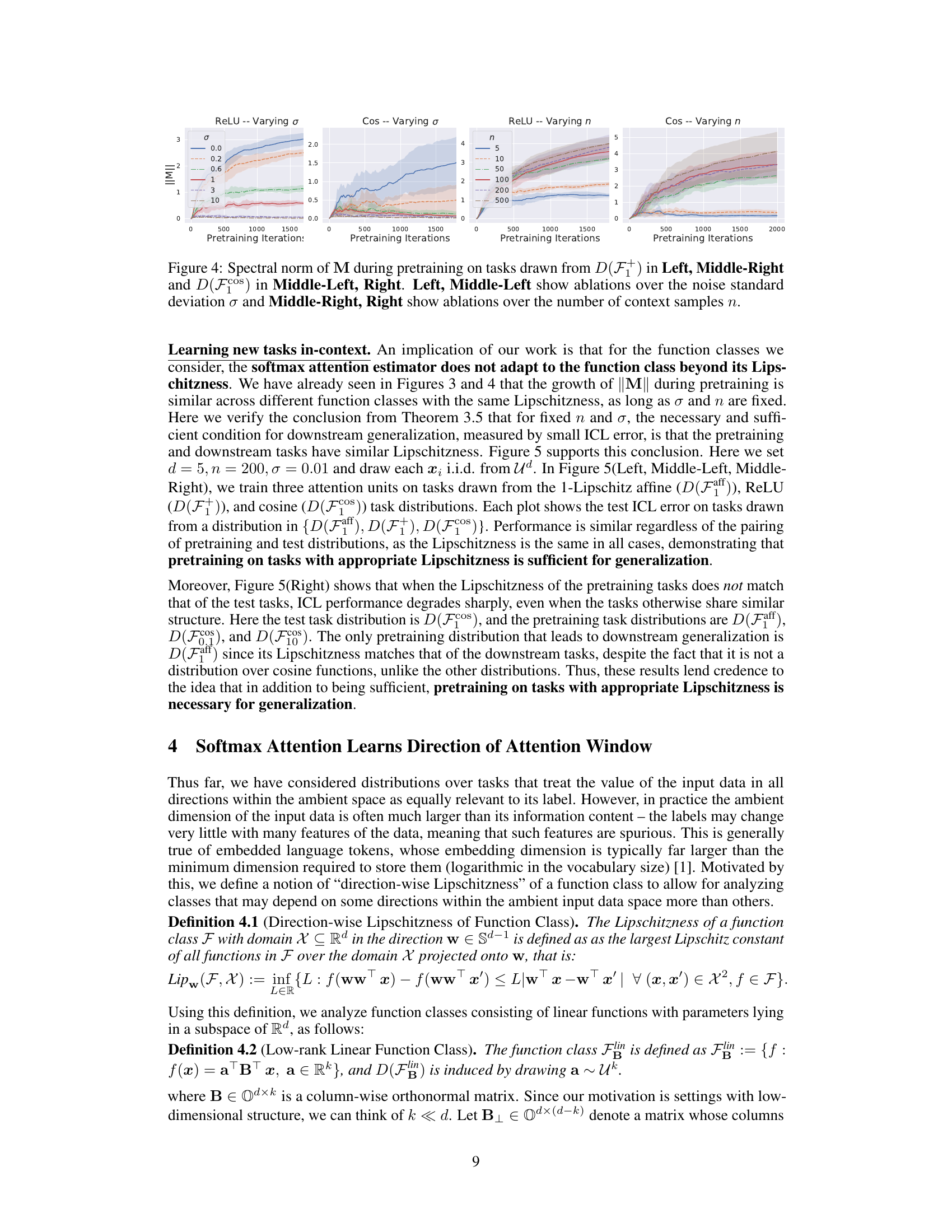

More on figures

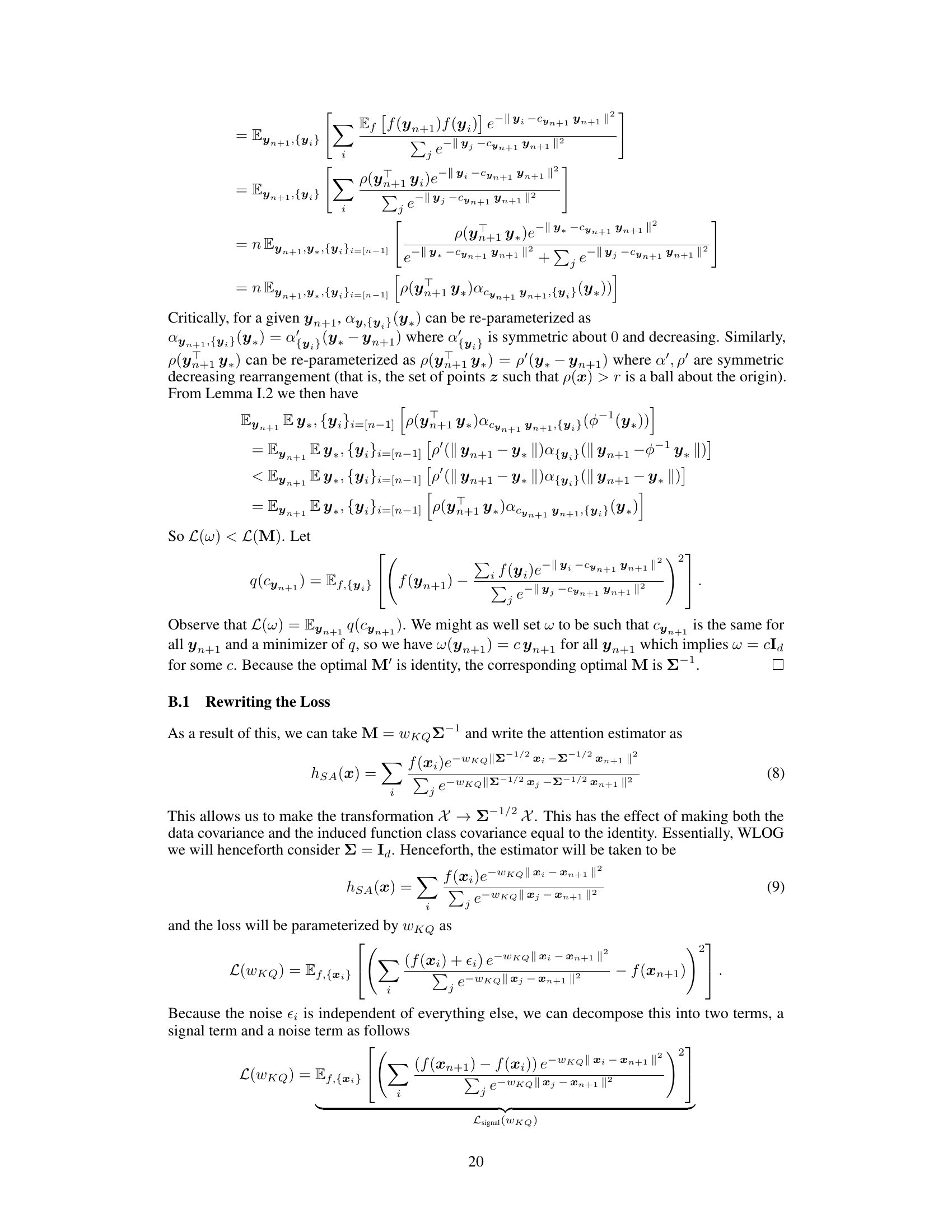

This figure shows how the softmax attention mechanism adapts its attention window to the Lipschitzness of the target function and the noise level in the training data. The top row displays three regression tasks with increasing Lipschitzness. The middle row compares the attention weights assigned by the softmax and linear attention models. The bottom row shows the in-context learning (ICL) error, demonstrating that softmax attention achieves lower error by adapting its window size.

This figure shows how the softmax attention mechanism adapts to different function Lipschitzness and noise levels in an in-context learning (ICL) setting. The top row illustrates three regression tasks with varying Lipschitzness, showing how the optimal attention window (the region of input space that influences the prediction) shrinks as Lipschitzness increases. The middle row compares the attention weights assigned by softmax and linear attention, demonstrating the adaptive nature of softmax attention. Finally, the bottom row illustrates how ICL error changes with the number of context samples, showing that softmax attention achieves lower error by adapting to the function Lipschitzness.

This figure shows how the softmax attention mechanism adapts to different function Lipschitzness and noise levels. The top row illustrates three target functions with increasing Lipschitzness, along with noisy training data. The middle row plots the attention weights assigned to each data point in the context by the softmax and linear attention models. The softmax model’s weights show adaptation to Lipschitzness, widening their focus for less smooth functions. The bottom row presents the in-context learning (ICL) error for each setting as the number of context samples increases. The results show that softmax attention achieves lower error by adapting its focus to the function’s smoothness and data quality.

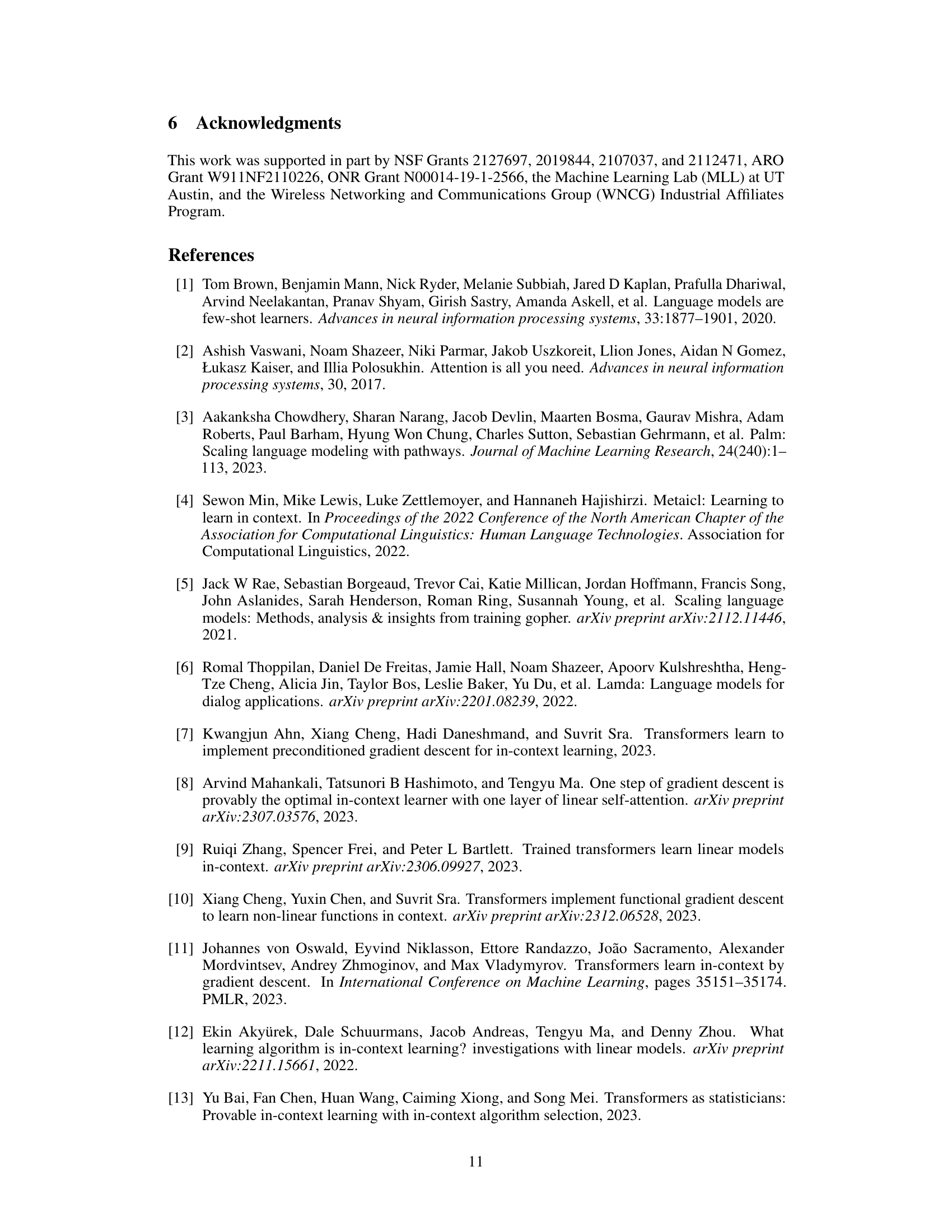

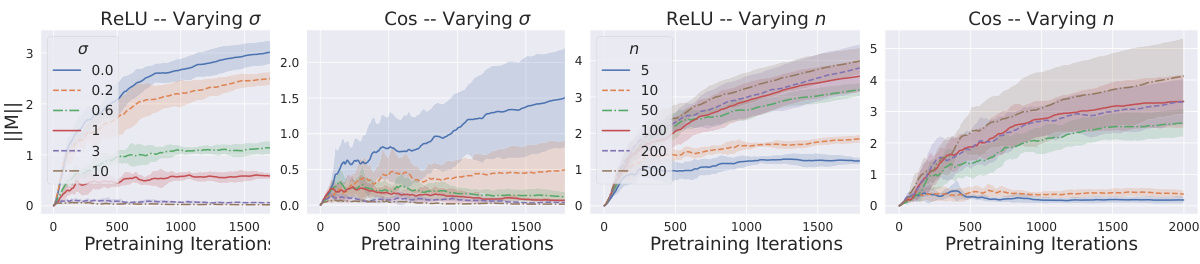

This figure shows the test ICL error for softmax attention trained on different function classes, with the same Lipschitz constant (L=1). The left three plots demonstrate that when both pretraining and test tasks have the same Lipschitz constant, test error is low regardless of the specific function class. The rightmost plot shows the importance of having matching Lipschitz constants between pretraining and test tasks; using a mismatch leads to high error.

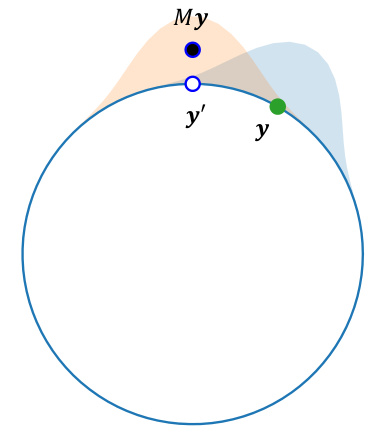

This figure compares two methods for estimating the value of a function at a given point, using either a matrix M or a vector w to weight the contributions of nearby points. The figure shows that using w leads to a more accurate estimate.

The figure shows how the softmax attention mechanism adapts to different function Lipschitzness and noise levels in in-context learning. The top row displays target functions with varying Lipschitzness. The middle row compares attention weights between softmax and linear attention mechanisms, highlighting the softmax’s ability to adapt the attention window size based on Lipschitzness. The bottom row shows how the ICL error varies with the number of context samples under different settings, demonstrating the effectiveness of softmax attention when it adapts to the function’s characteristics.

This figure shows how softmax attention adapts to the Lipschitzness of the target function in an in-context learning setting. The top row illustrates three regression tasks with varying Lipschitzness. The middle row compares attention weights for softmax and linear attention, showing that softmax attention adjusts its window based on Lipschitzness, while linear attention does not. The bottom row demonstrates that this adaptability improves ICL performance.

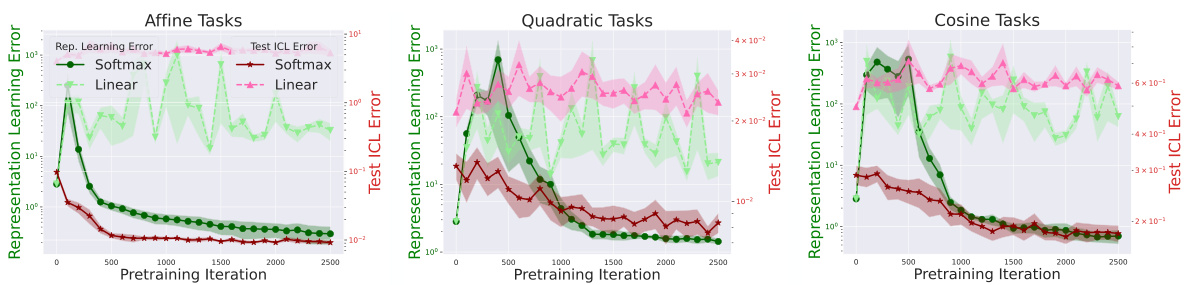

This figure shows the results of experiments comparing softmax and linear attention mechanisms in a low-rank setting. Three different function classes (affine, quadratic, and cosine) were used to generate tasks. The plots show both the representation learning error, measuring how well the attention mechanism learns the low-dimensional structure of the tasks (ρ(M,B)), and the test ICL error, measuring the performance of the pretrained attention mechanism on unseen tasks. The results indicate that softmax attention effectively learns the low-rank structure, leading to improved performance, while linear attention does not.

Full paper#