↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many neural systems exhibit localized receptive fields (RFs), where neurons respond to small, contiguous input regions. While sparsity-based models reproduce this feature, they fail to explain localization’s emergence without explicit efficiency constraints. This paper addresses this gap by investigating a feedforward neural network trained on a natural image-inspired data model. Previous work highlighted the importance of non-Gaussian statistics, but the underlying dynamical mechanisms remained unclear.

This research derives effective learning dynamics for a single nonlinear neuron, precisely showing how higher-order input statistics drive localization. Importantly, these dynamics extend to many-neuron settings. The analysis challenges the existing sparsity-centric view, proposing that localization arises from nonlinear learning dynamics interacting with the higher-order statistical structure of naturalistic data. Simulations validate the model’s predictions. The findings suggest that localization might be a fundamental consequence of learning in neural circuits rather than an optimization for efficient coding.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it offers a novel explanation for the widespread presence of localized receptive fields in neural circuits, challenging the established view that sparsity is the primary driver. It provides a new framework for understanding how nonlinear learning dynamics and naturalistic data interact to produce this ubiquitous neural architecture, opening avenues for exploring the role of higher-order statistics in neural computation and potentially influencing the design of more biologically plausible artificial neural networks.

Visual Insights#

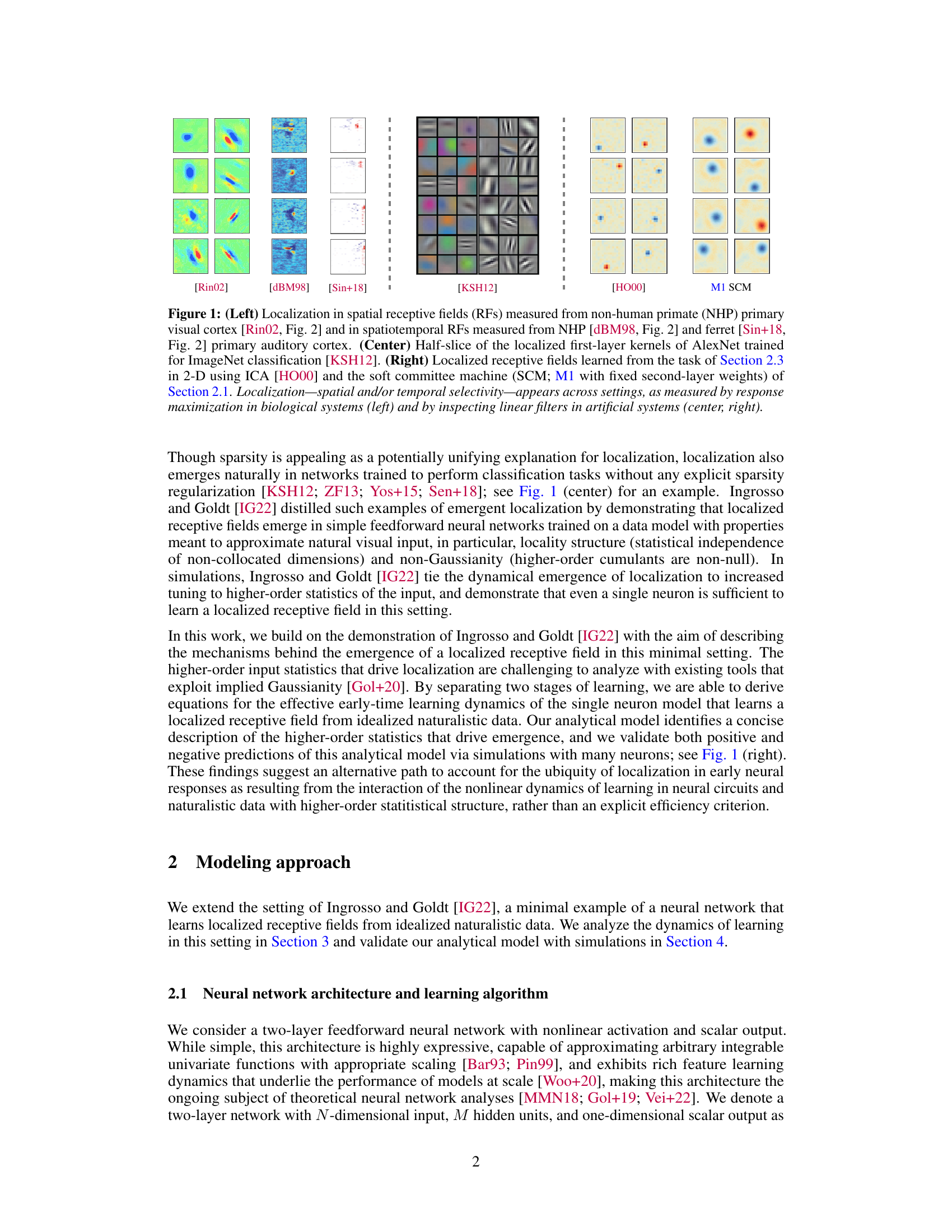

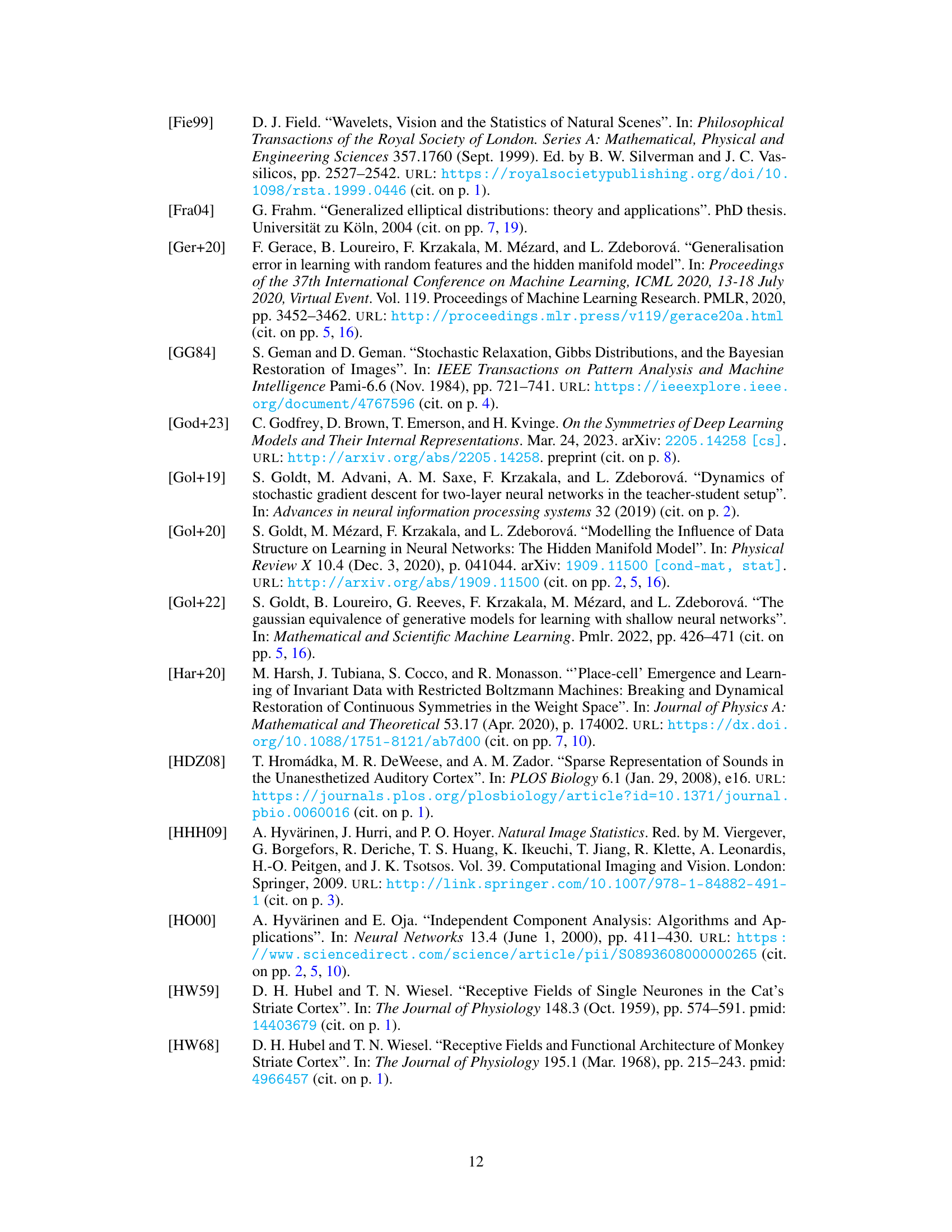

This figure shows examples of localized receptive fields in various settings. The left panel displays localized receptive fields from biological systems (non-human primate primary visual and auditory cortices). The center panel presents localized first-layer kernels from AlexNet, a deep neural network trained on ImageNet. The right panel showcases localized receptive fields learned from a data model inspired by natural images using ICA and a soft committee machine.

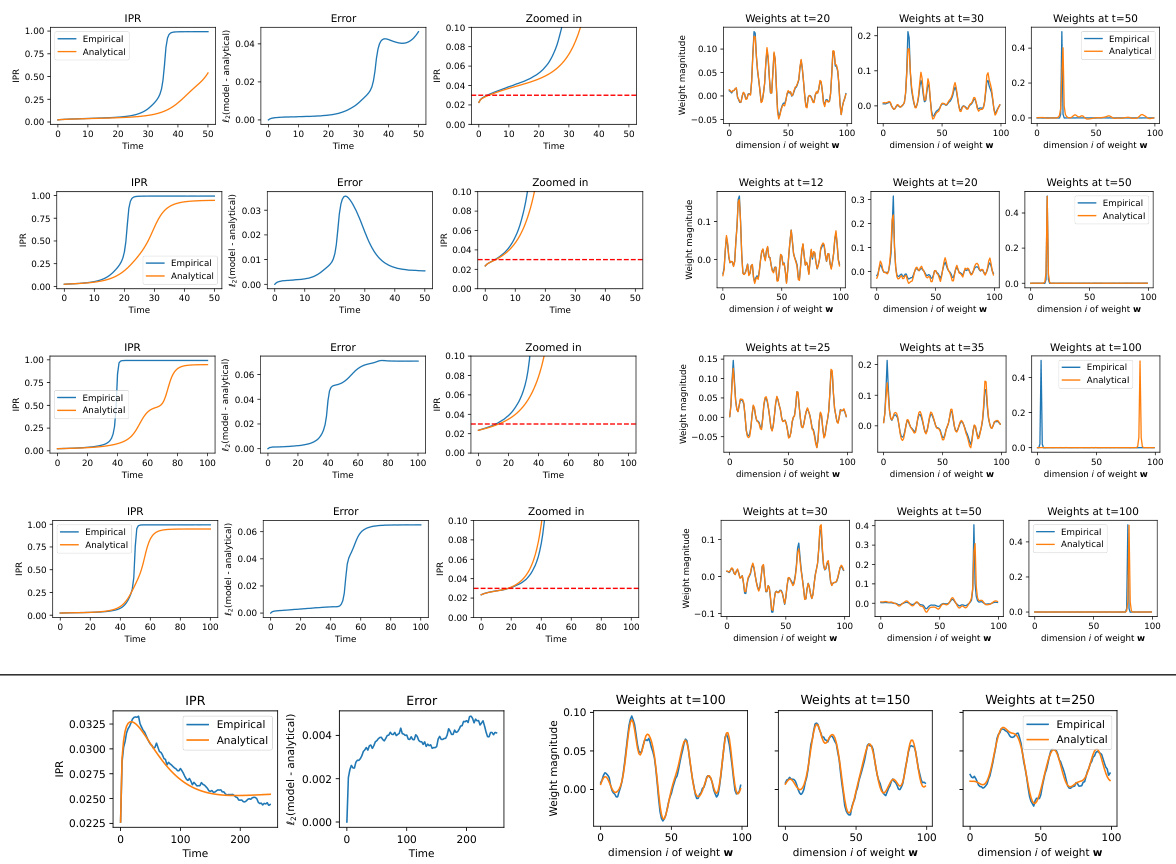

This figure validates the analytical model by comparing its predictions with empirical results from simulations. It shows that the model accurately predicts localization in weights for appropriate data distributions, and that the model’s limitations arise when the assumptions underlying it are violated.

In-depth insights#

Nonlinear Localization#

Nonlinear localization, in the context of neural receptive fields, signifies the emergence of spatially restricted neuronal responses without explicit constraints on network efficiency. This contrasts with traditional approaches like sparse coding, which explicitly optimize for sparsity. The research explores how localized receptive fields might arise from the inherent dynamics of learning in a feedforward neural network trained on naturalistic image data. A key finding is the importance of higher-order input statistics, particularly non-Gaussian distributions, in driving the emergence of localization. The analysis delves into the effective learning dynamics, revealing the precise mechanisms through which these statistical properties induce localized receptive fields. The model’s predictions extend beyond the single-neuron level, demonstrating the ubiquity of localization as a natural consequence of nonlinear learning in the context of real-world sensory input. The research proposes an alternative explanation for localization, moving beyond the traditional emphasis on explicit sparsity or efficiency criteria.

Learning Dynamics#

The study’s analysis of learning dynamics centers on understanding how localized receptive fields emerge in neural networks. The researchers move beyond simply optimizing sparsity or independence, focusing instead on the role of non-Gaussian input statistics and nonlinear dynamics. A key finding is that higher-order statistical properties of the input data directly drive the emergence of localization. By developing an analytical model of a single neuron’s learning dynamics, they show that negative excess kurtosis in the input data is a crucial factor promoting localized receptive fields, while positive kurtosis prevents localization. These findings are validated through simulations with many neurons, demonstrating that the analytical model provides insights applicable to more complex neural network settings. This work offers a compelling alternative explanation for the prevalence of localized receptive fields, emphasizing the influence of the interplay between data characteristics and the nonlinear dynamics of learning itself.

Higher-Order Effects#

Higher-order effects in neural networks, especially concerning receptive field formation, are crucial yet often overlooked. While second-order statistics (covariance) provide a foundational understanding of how neurons respond to stimuli, higher-order statistics (e.g., kurtosis) capture finer details like the shape and sparsity of receptive fields. Non-Gaussianity, reflected in these higher-order moments, plays a vital role. The dynamics of learning, particularly in the presence of non-linear activation functions, amplify these higher-order effects, leading to localized receptive fields. This is a key departure from top-down approaches (like sparse coding), which rely on explicit constraints. The model’s analysis reveals how the interaction between non-linearity, natural image statistics (which exhibit strong higher-order effects), and learning dynamics produce the observed localization, thereby providing an alternative explanation for this ubiquitous phenomenon. The impact extends to various aspects of neural processing and learning, showing how subtle statistical properties of input data can significantly shape neural circuit function.

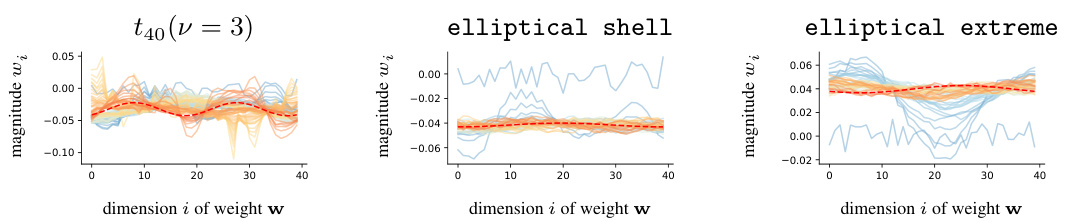

Elliptical Data Fail#

The section ‘Elliptical Data Fail’ likely investigates the performance of the proposed model or a similar model when trained on data drawn from elliptical distributions. The core finding is probably that elliptical data hinder the emergence of localized receptive fields, a key characteristic the model is designed to learn. This failure is significant because elliptical distributions, while encompassing a broad family of non-Gaussian distributions, lack the specific higher-order statistical properties crucial for driving localization in the model’s learning dynamics. The analysis likely demonstrates that even with non-Gaussian characteristics, the absence of the particular structure present in natural images prevents the emergence of localized receptive fields. The authors might contrast this with successful localization on other non-Gaussian data types, suggesting that simple non-Gaussianity is insufficient; rather, specific structural aspects of the data are critical. This result reinforces the central argument that higher-order statistics, beyond mere non-Gaussianity, play a decisive role in the development of localized receptive fields.

Future Directions#

The paper’s core finding, the crucial role of higher-order statistics in driving localization, opens exciting avenues. Future work could explore how these principles extend to more complex neural architectures and datasets, moving beyond the idealized models used. Investigating the interplay between non-Gaussianity and other factors such as sparsity, network architecture, and learning dynamics is crucial. Analyzing different nonlinear activation functions beyond the ReLU and examining their effects on localization would offer valuable insights. Furthermore, applying this framework to real-world datasets and comparing its predictions to biological data from various sensory modalities could validate its robustness. Finally, incorporation of noise into the model is important to understand its impact on localization, as biological systems are inherently noisy. The study of how localization interacts with other functional aspects of neural circuits would enrich our understanding of its importance in the overall computation performed by the brain. A comparative study examining the efficiency of localization compared to explicit sparsity-based methods, especially in high-dimensional data is also warranted.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows examples of localized receptive fields (RFs) in different neural systems. The left panel displays examples from biological systems: spatial RFs in NHP primary visual cortex, and spatiotemporal RFs in NHP and ferret primary auditory cortex. The center panel shows localized first-layer kernels from AlexNet, a deep neural network trained on ImageNet. The right panel shows localized receptive fields learned from a specific task using independent component analysis (ICA) and a soft committee machine. The figure highlights the ubiquity of localized RFs across various neural systems, both biological and artificial.

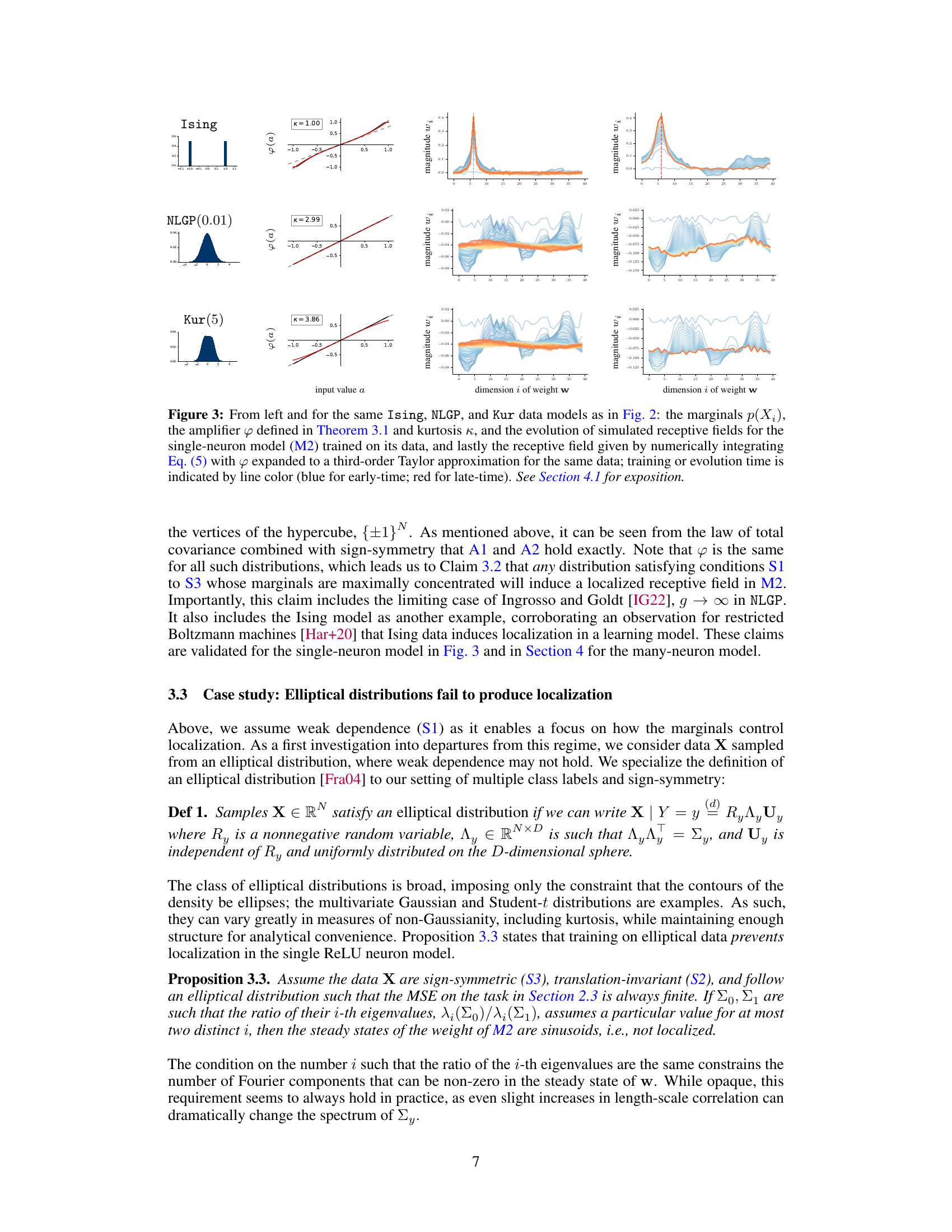

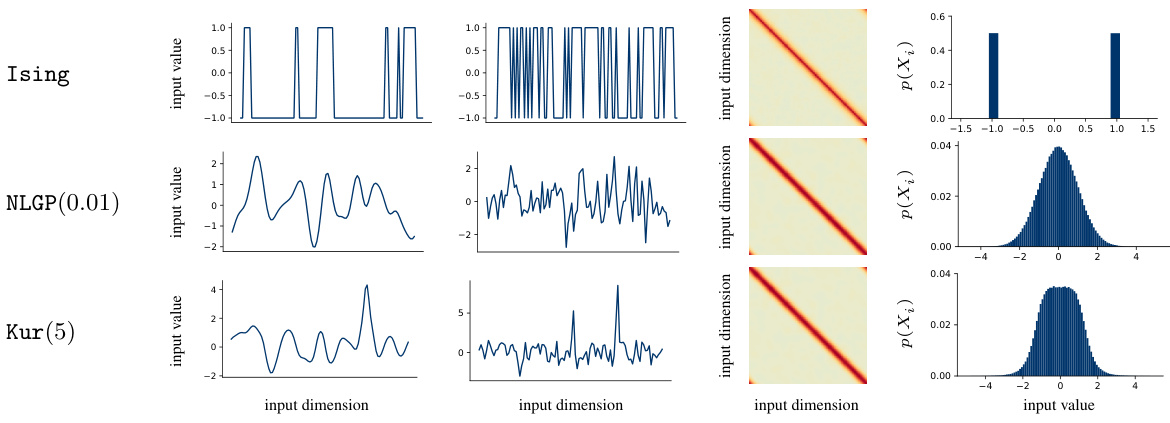

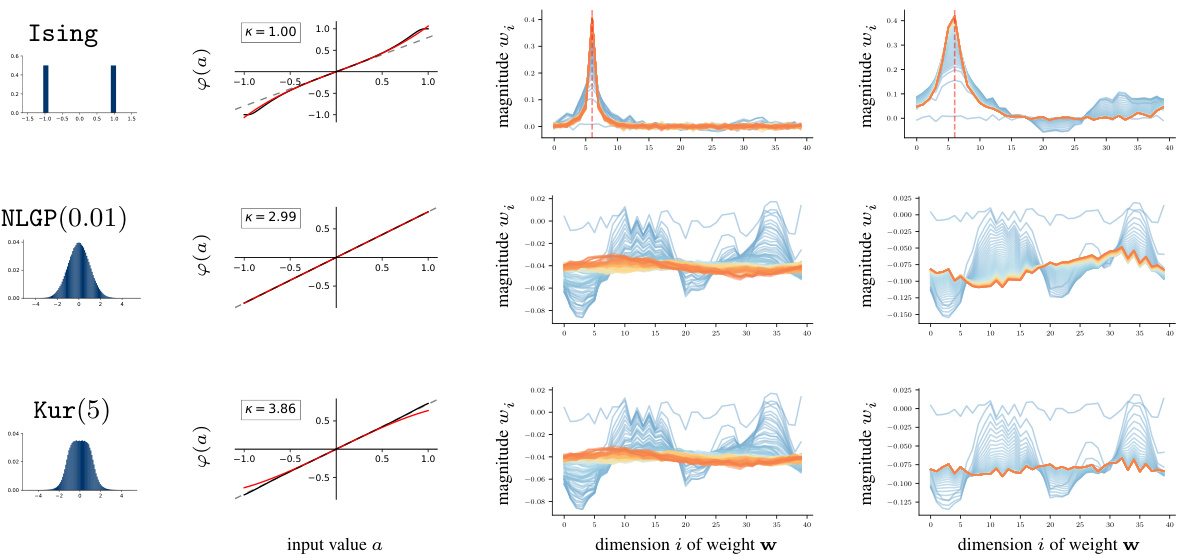

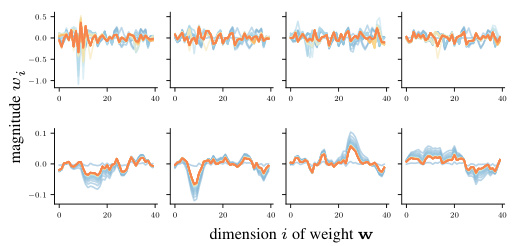

This figure shows the marginals, amplifier function, and kurtosis for three different data models (Ising, NLGP, Kur). It then displays how simulated receptive fields evolve over time for a single-neuron model trained on each dataset, comparing the simulations to the results of a third-order Taylor expansion approximation of the theoretical model. The color of the lines represents the training time.

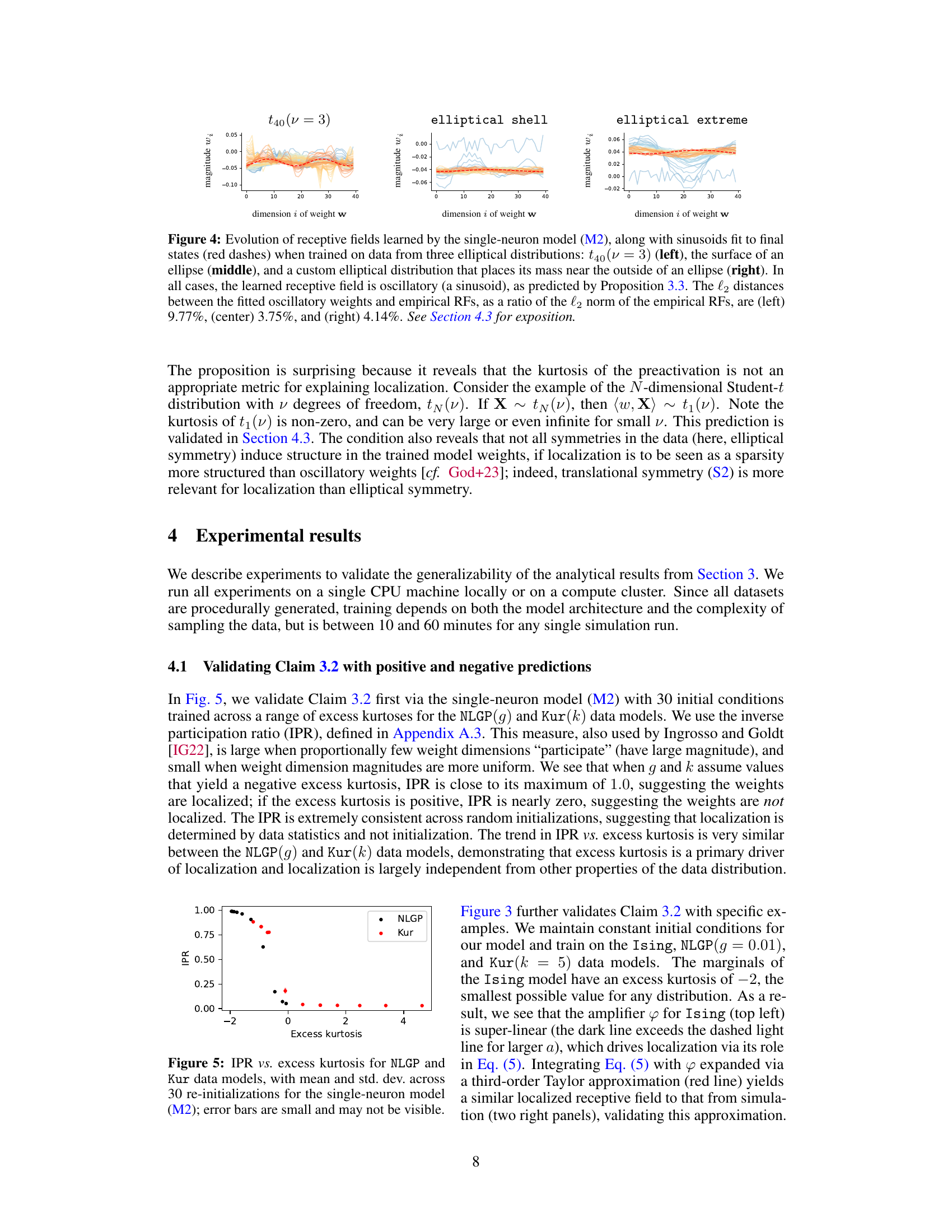

This figure shows the results of training a single-neuron model (M2) on three different elliptical distributions. The left panel shows the results for a t40(v=3) distribution, the middle panel shows results for data sampled from the surface of an ellipse, and the right panel shows results for a custom elliptical distribution concentrated near the ellipse’s outer edge. In all three cases, the learned receptive fields are oscillatory, confirming Proposition 3.3, which states that elliptical data prevent localization in the single neuron model. The red lines show the best-fit sinusoid to the learned weight vectors.

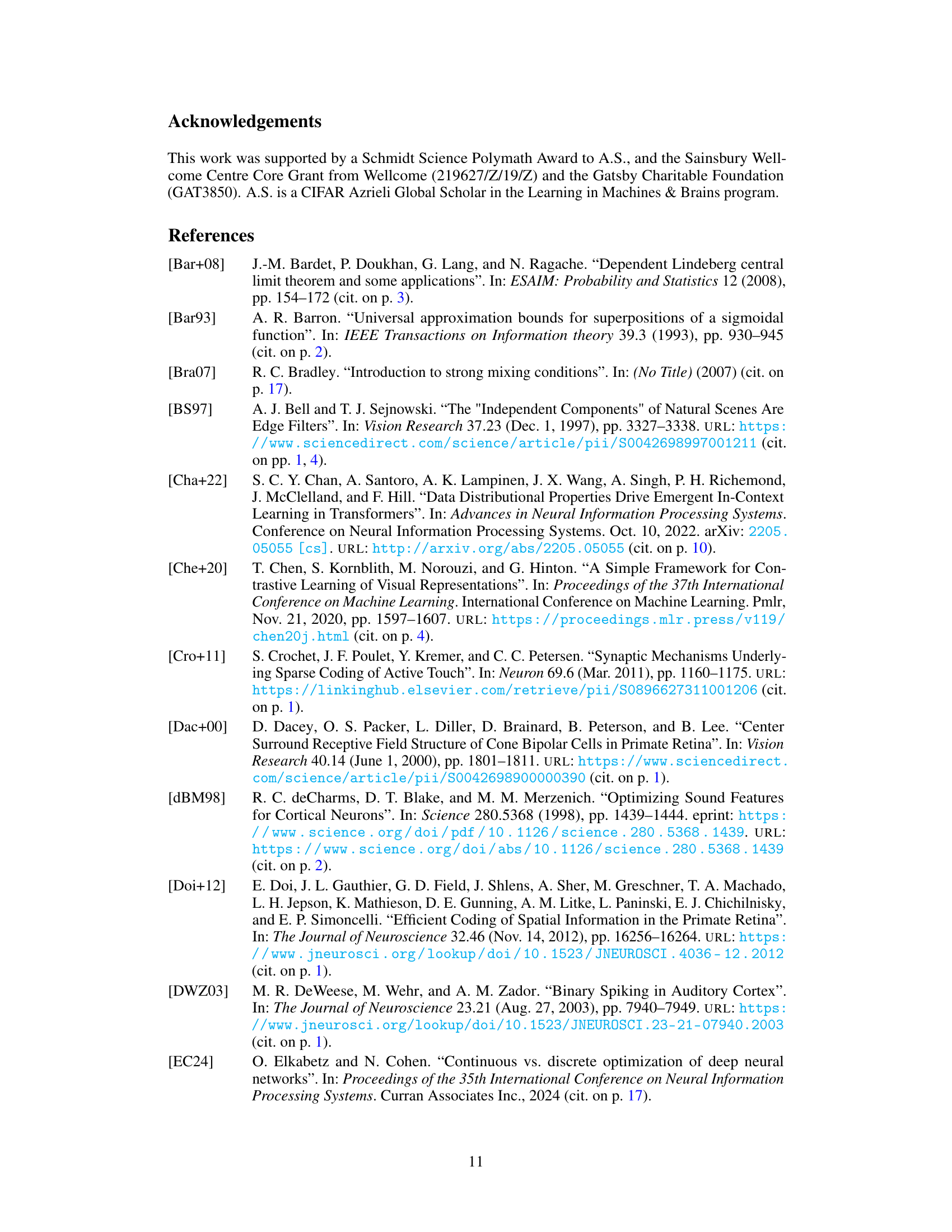

This figure validates Claim 3.2 from the paper by showing the relationship between the inverse participation ratio (IPR) and excess kurtosis for two data models, NLGP and Kur. The IPR is a measure of localization, with higher values indicating more localized receptive fields. The excess kurtosis is a measure of the non-Gaussianity of the data, with negative values indicating heavier tails than a Gaussian distribution. The plot shows that as the excess kurtosis becomes more negative (heavier tails), the IPR increases, indicating a stronger tendency towards localization. This supports the claim that negative excess kurtosis in the input data is a necessary condition for the emergence of localized receptive fields in the single-neuron model.

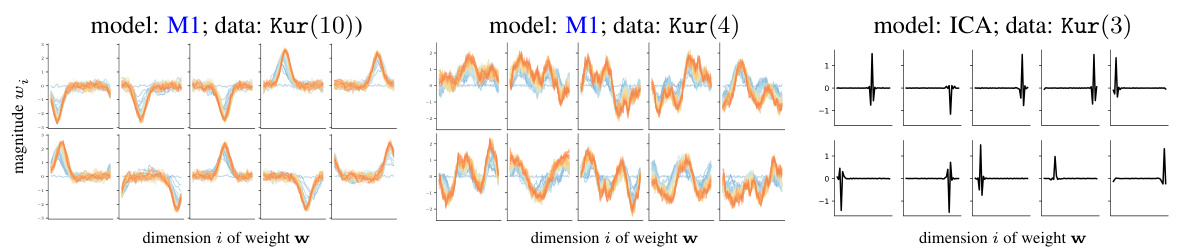

This figure shows the receptive fields learned by three different models trained on data with different kurtosis values. The left and center panels show the receptive fields learned by a many-neuron model with fixed second-layer weights, trained on data with kurtosis values of 10 and 4 respectively. The right panel shows the receptive fields learned by an ICA model trained on data with kurtosis value of 3. The figure demonstrates that the type of receptive fields learned depends on both the model used and the statistical properties of the data.

This figure shows a comparison of the marginal distributions, the amplifier function (from Theorem 3.1), the kurtosis, and the learned receptive fields for three different data models (Ising, NLGP, Kur). It also shows the results of numerically integrating Equation 5 (from Lemma 3.1) using a third-order Taylor expansion of the amplifier function. This comparison aims to validate the theoretical model by showing how well it predicts the localization of receptive fields in different scenarios.

This figure shows a comparison of the marginal distributions, the amplifier function (from Theorem 3.1), and the kurtosis for three different data models (Ising, NLGP, and Kur). It also displays the evolution of simulated receptive fields for a single-neuron model trained on each data model, alongside the receptive fields obtained by numerically integrating Equation (5) using a third-order Taylor expansion. The color of the lines indicates the training time (blue for early-time, red for late-time).

Full paper#